Abstract

Starting from the concept of sustainability in fashion, the aim of our research is to analyse to what extent the Zara Join Life collection is sustainable, environmentally friendly (as advertised), and transparent, in terms of the information provided to the consumer, in order to offer Zara’s fashion consumers a set of aspects to take into account when intending to buy responsibly, such as the composition of the product, the percentage of recyclable materials used, its origin, etc. Our practical goal is to generate a gradual change in Zara consumers’ behaviour by creating a set of basic skills to transform one from a fast, superficial consumer into a slow, conscious customer with decision-making power. We analysed the Zara Join Life collection, which is advertised on the company’s website as supporting sustainability as a continuous project. The methodology consisted of a documentation-learning stage in order to reach the stages of data collection, data processing, and information organization—the methods used for the analysis of fashion consumers’ behaviours. The analysis was conducted on 40 Zara Join Life collection garments (10 women’s clothing items, 10 men’s clothing items, and 20 garments for kids, both girls and boys) sold online on Zara’s website. The collected research data were analysed and interpreted within the case study.

1. Introduction

Discussing a topic such as sustainable fashion is a necessity, not only because humanity needs to address the disasters it has caused and continues to produce, but because there is a need for change. It is a crisis that transcends those of earlier years—e.g., the financial crisis as well as the ongoing COVID 19 crisis. Located at the intersection between art and functionality, between aesthetics and industry, fashion has vast dimensions in which the economic, social, and natural environments contribute to a modern and fluctuating composition, one that is versatile and ubiquitous, which includes aspects of everyday life, but also notions of legislation, human rights, the environment and consumption, trade, profit, and credit. It is a Rubik’s cube in which the facets are constantly changing in the hands of a persevering and ingenious player [1,2,3].

“We live surrounded by cloth. We are swaddled in it at birth and shrouds are drawn over our faces in death. We sleep enclosed by layer upon layer of it (…) and, when we wake, we clothe ourselves in yet more of it to face the world and let it know who we shall be that day” [4].

We speak of fashion as if it was something minor, a whim, or as if it was innocent; in fact, this facade, through which we want to appear chic, elegant, modern, and tasteful in society, is responsible for pollution, exploitation, destruction, waste, and inhumane actions. To each component of the definition of a fashionable individual corresponds another one of a monstrous nature—children who pick cotton for an insignificant amount of money a day in Turkey, tons of rotten marine animals, poisoned water, and the atmosphere being filled with the smoke of garbage crematoria, in which over 80% of last season’s collection is burned so that large companies do not spoil their image by not selling [5,6,7,8].

We are often deceived by the desirable appearance of a package, but when opened, the contents can either be old-fashioned or deemed boring. The waste people produce in their lives begins with their first diaper and is produced continuously thereafter, facilitated by the unavoidable mechanisms of advertising, excessive production, and the inertia with regard to accumulating unnecessarily huge profits.

This study adds another dimension to the fashion phenomenon, one that should distinguish between the indifferent consumer and the ethical consumer—the professional consumer—emphasising aspects of ethics in fashion and trying to find an answer to the question:

Can we remain voguish but become ethical at the same time [9,10,11,12]?

The value of the concept of ethics in fashion comes from the fact that we must consider the attitude towards fashion as an educational and cultural component, because the culture of clothing is not only about money, but also about texture, context, and everything that enables a small mise en scene show to occur implicitly by exposing certain creations together with our presentation in society in our daily activities.

“The range of possible messages—including gender, age, class, occupation, origin, personality, tastes, sexual desires and current mood—can be perceived by analysing the hidden language of clothing, which is related to the tone, colour palette, texture and materiality of the clothing items [4].”

Appearance and clothing—glasses, hat, gloves and purses, shoes and jackets, hairstyles and allure are factors that an individual considers and makes decisions about based upon their education—express and communicate in a non-verbal language a person’s culture and civilization. They express the permanent cultural development of the individual and the implementation of their education.

2. Materials and Methods

Starting with the concept of sustainability in fashion, this study aims to analyse the sustainability and transparency of a collection advertised as sustainable (Zara’s Join Life collection) in order to warn Zara fashion consumers about the basic behavioural baggage that slows down fashion consumption through awareness of the consequences deriving from fast consumption.

We strongly believe that conscious consumption must be assimilated in all lifestyles, not only in terms of cars, food, detergents, cosmetics, etc., but also in terms of outfits, clothes, and fashion.

In terms of the research methods, we started with a documentation-learning stage to collect data; then, as the next stage in our research, we processed the collected data, organised the information, and interpreted it.

We chose to conduct our analysis on the Zara Join Life collection as it is presented on Zara’s website as a step forward in terms of sustainability in fashion.

The present research was conducted as a bibliographic study and as a case study at the same time. Content analysis of the doctrine, databases, and Internet sources was the basis of the documentation. In addition, analysis of the current European legislation and the strategies of the European authorities constituted another direction of study, interpretation, and analysis.

The results of this study could be used by researchers in the area of sustainability in lifestyle and by clothing consumers from the Zara retailer, both in online commerce and in store commerce.

The present study has at its centre the idea that continuing education involves the research, identification, and recognition of the cues and indicators of sustainability that must be included in all human manifestations of what makes up a lifestyle [13,14].

Since Zara, as part of Inditex, is emblematic of the fashion industry, the study was conducted on 40 clothing items of the Join Life collection, analysing the sustainability of this collection in terms of:

- -

- Sustainability regarding the natural environment: care for fibres, care for water, composition of textiles/fibres, and recycling capacity. Sustainability regarding the economic environment: transport costs.

- -

- Transparency of information—the consumer’s access to information.

3. Fashion—Specific Social Recognition

3.1. The General Notion of Fashion

According to the Romanian language dictionary, the term “fashion” has a broad definition that begins with individual habits and behaviours and extends to collective manifestations, including certain ideas, concepts, and theories. Thus, fashion is:

- A set of tastes, habits, and preferences that predominate at a given time in a society regarding clothing, attire, behaviour, and ideas.

- A habit—collective habit—specific at a given time to a social environment, specifically taste, a generalised preference at one time for a certain way of dressing.

According to the Oxford Advanced American Dictionary, the noun “fashion” is defined as:

- A popular style of clothes, hair, etc., at a particular time or place; the state of being popular.

- A popular way of behaving, doing an activity, etc. [15].

The new concept of sustainable fashion

Sustainable fashion can be defined as a process of changing the ways in which design is thought of and put into practice, from the first moment of creation to the production, communication, and use of various clothing items [16].

Lifestyle, related as it is to quality of life, relates to the well-being of the individual that interacts with nature, living in balance with its main components—earth, water, air, flora, and fauna.

As a reflection of the environment in which man lives, fashion frequently proposes collections inspired by the environment but has not proposed a collection based on ecological disasters. Sustainable fashion is much more than that, and bucolic images are no longer sold as prints on T-shirts.

However, fashion, either fast or slow, green, and conscious, does not exist by itself; it has a carrier, a receiver, and has created and even creates victims—the so-called fashion victims. Therefore, in this huge mix of fashion producers, we reach the consumption and the consumer—the destination of fashion.

The modern human being, a big consumer of food, cars, mobile phones, appliances and gadgets, shoes, drinks, and processed products, and clothes, the ultramodern person, the urban par excellence, produces a quantifiable amount of waste. They consume a lot, more and more. At the same time, the clothing industry produces “far more than we could ever reasonably need. In 2021, for example, it was estimated that 150 billion garments were stitched together, enough to provide each person alive with 20 new articled of clothing. Americans increased their spending on clothing and footwear 14% between 2011 and 2016, up to 350 billion dollars in total. Similar or greater increases have been elsewhere. In 2016, the market for fibres increased 1.5% to 99 million tons [4].”

How does an entity manage to turn an individual into a fashion victim, with fashion referring to the latest generation of mobiles, sports shoes, or cars? The textile industry produces textiles from which clothes are made, and from which collections are created, that the urban human being consumes.

At this point, the analysis moves towards the broad concept of sustainability proposed in 2008 by European regulations trends. The financial crisis shifted focus from the textile crisis and the pollution that this industry produces, which is second only to car and air pollutants. Sustainability is no longer just the concern of some environmentalists, NGOs, experts, and authorities; we affect sustainability with every purchase of food, clothes and with each plastic bag of olives or salad.

Sustainability requires durability and leaving something behind and helping where possible.

People, including those in underdeveloped countries who have died due to being poisoned by air and water or—as was the case in Bangladesh, the second largest clothing producer in the world—are deeply affected by the factories where they worked to support the fashion trends of Europe.

The United Nations has defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present in such a way that the ability of future generations to meet their needs is not compromised [17].”

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has the same definition for sustainability as the United Nations and has created a single standard for sustainability. The ISO 26000 standard defines how an organization can contribute to the full spectrum of sustainable development through socially responsible behaviour.

How did we come to ask questions about sustainability in this context where humanity has managed to transit the financial crisis of 2009, is having a hard time going through the COVID pandemic and is starting to carry out resilience plans? Is humanity trying to become aware that sustainability means life? Or more specifically—why has the textile industry become a key element of the European and global strategies?

Despite de excessive consumption, it is important to point out that “the awareness of the concern with the consequences of this consumption gives rise to new ways of consuming and producing fashion causing less impact both environmental and social,” [18] and “promoting a more sustainable fashion to a point of spreading a new mindset for pushing consumption toward consciousness, and especially to forge an ethical appeal for brands [19].”

3.2. Terminology and Specific Language in Sustainable Fashion

Since 2008, we have witnessed the creation and amplification of a tendency to define the concepts that are part of the broad term of sustainability—as an element of sustainable development—by imposing a specific language, with some terms that define new concepts [20]. It is not about their non-existence until now, but about their ignorance [21]. We are talking about ethical, animal cruelty-free, organic, conscious, fast, and slow fashion, etc.

“Sustainable fashion is one of the most widely used terms in the fashion industry today. It is not only about the trend of socially responsible brands with eco-friendly products or coming up with some regulatory policies but also for catering to upcoming demands of conscious consumers to adopt sustainable fashion [22].”

- Ethical fashion is a broad term that considers, first, social aspects, more precisely, the working conditions of people in the textile industry [17]. The field must extend towards ethical consumption and the conscious consumer, and towards the ethics of the designer, of the producer, of the seller, of the advertiser.

- Animal cruelty-free highlights the cruelty towards the animals subjected to tests of all kinds; the tendency must be to ensure the welfare of animals so that they do not become the real victims of fashion. From the caveman who wrapped himself in furs to the modern man, throughout our history our clothes have depended on the suffering of animals [23,24].

- Slow fashion—this term can be defined as a trend or an alternative movement against fast fashion. In the fashion industry, the term conscious is often used as a synonym for ethical, eco or even sustainable. There are brands that abuse this ambiguity, more precisely, they carry out a greenwash, but there are also brands that declare themselves conscious and at the same time are in accordance with the rules of sustainability. The Collective Humanity Group, founded in Cambodia, considers it conscious fashion when a brand of clothes and/or accessories prioritises the sustainability of people and the planet to the same extent as their profit. Let us remember this new perspective on slow fashion—people = planet = profit [25,26].

- Timeless design—we can say that a Chanell jacket, still in vogue and fashionable, supports the circularity of the circular economy. In fashion, design is the first tool through which polluting elements can be removed. At the same time, with a timeless design it is possible to prolong the maintenance of the clothes in use.

- Greenwashing—the Cambridge dictionary defines this term quite diplomatically: you make society believe that you have a company that does more for the environment than it really does [17]. In fact, the term is used to define the practice of those companies that claim to be “sustainable when, in reality, they only carry our superficial environment activities” [27,28].

3.3. Fashion as a Negative Phenomenon

The relatively recent but constant concerns about reducing the brutal effects that humankind have upon the environment could not but approach, perhaps with astonishment, an industry that, although called light, pollutes excessively and regularly destroys. The textile industry, the clothing industry, and the fashion industry offer, in big stores and in the online environment, brilliant collections, at least two for each season. To these, we can add collections for cottages, resorts, and houses and many more.

The leap from haute couture to pret a porter and then to mass production was a real revolution within the industrial revolution. Democratization of the matter has determined/imposed easy access to clothes—quantity at the expense of quality, and a lack of transparency.

On the other hand, clothing bought in the grocery store is no longer considered fashion. Not every textile is fashion and not every company that sells clothes makes fashion. Companies that sell clothes with food, detergents and dog food are not considered fashionable.

The concept of clothes per kilogram, of clothes sold near canned fish, of slippers that you buy with a bagel and of linen displayed near the shelf with oil bottles is no longer a novelty. The easy access to clothes has damaged the concept of fashion in the sense that clothes have become a first necessity in Maslow’s pyramid and not an artistic aspiration [29,30].

Reducing fashion to this extent paves the way for the conceptual delimitation of fast fashion.

From the violation of Uighur rights in China to the exploitation of children in Turkey, these strange links have been tied and untied. Perhaps cutting this Gordian knot is within the reach of the average consumer, the 35–40-year-old woman, educated and aware, who will become the exponent of new concepts, such as conscientious fashion. Although it currently represents the weak link in the product–sale–consumption chain, the customer model could be the one to act to get out of the vicious circle of high consumption and to stop the overproduction of goods, of clothes in particular.

The evolution of fashion from the well-known fashion houses and boutiques to the mega producers and sellers today is related to the descent of the high-street creations from the catwalks and the emergence of the design profession.

3.4. The Notion of Fast Fashion

Like eating fast, the so-called fast fashion “is a term used to describe a highly profitable business model based on replicating catwalk trends and high fashion designs and mass-producing them at low cost. The term fast fashion is also used to generically describe the products of the fast fashion business model” [31]. The fast fashion business model was made possible during the late 20th century as the manufacturing of clothes became cheaper and easier, through new materials such as polyester and nylon, efficient supply chains and quick response manufacturing methods, as well as inexpensive labour in sweatshop production and low-labour protection bulk clothing manufacturing industries in south, southeast, and east Asia. Companies such as H&M and Zara built business models based on inexpensive clothing from the efficient production lines, to create more seasonal and trendy designs that are aggressively marketed to fashion-conscious consumers. Fast fashion applies an extreme version of planned obsolescence to clothing. As these designs are changing so quickly and are so cheap, consumers buy more clothing than they would previously, so expectations for those clothes to last decreases.

This decrease in quality, increase in purchasing, and speed of replacement creates a large amount of clothing waste; much clothing produced under the fast fashion model means lower quality and thus is harder to reuse or recycle. Moreover, the rapid and cheap production processes of fast fashion create increased pollution and other environmental and social impacts—i.e., pesticide use in industrial cotton growth, fossil fuel extraction for synthetic materials or slave labour in sweatshops. In response to these impacts, environmentally or socially responsible consumers and designers have begun demanding zero-waste fashion or sustainable fashion. This increasing trend is creating pressure on globally fast fashion companies to change manufacturing and sales practices) [32].

4. Study Case—Zara Join Life Collection

As we previously mentioned in this study, the fashion industry has a massive impact on the environment, using “a resource-intensive supply chain that causes massive waste and creates environmental harm. The industry is one of the world’s largest producers of toxic environmental waste, affecting air, water, and soil resources [33].” The fashion industry is referred to as “one of the most polluting and damaging sectors of the worldwide economy, not only is the harm evident in the natural world but also within societies of people [34].”

We can say that fast fashion itself “consumes” designers, fibre producers, dressmakers/subcontractors, tailors, advertising producers, advisers, photographers, transporters, and other professions who are all required in its processes, ground in the mixer of this “white whale”. There could come a day when, like an exhausted Moby Dick, the fashion industry ends up decomposed on a deserted beach, under the torrid reproach of the former fast fashion consumer, obese after consuming the numerous collections he carried in his minimalist furnished apartment. Clothes go from a huge dressing room to landfill, where burning of them is hidden from the eyes of the consumers and is only addressed by environmentalists, which preserves their brand image. Yet could Melville’s nightmare—the impossibility of killing the white whale, the one who stole a leg from Captain Ahab—be shattered by the concerted activity of slow fashion activists?

Our analysis was made on a Zara collection, Zara being part of INDITEX, one of the huge clothing businesses, one that is “fast”, but also very fashionable, a business which involves hundreds of clothing designers who analyse the fashion trends daily and make new patterns that are put into production and of fashion advisers that identify what people want in terms of fashion.

It is such a complex system that the INDITEX recipe has come to be taught in the faculties of economics. Aspects regarding competition, environmental issues or human rights could be also studied as part of the law faculties curricula, while aspects concerning communication could be taught as part of the faculty of sociology curricula.

“Behind Inditex there is a still unique, different and difficult to copy operating model. It’s about their ability to have fashionable clothes very quickly”, says consultant Anita Balchandani [35].

Forced by the current implementation of increasingly imperative requirements of the wave of sustainability coming from international organizations, on the one hand, and from the U.E. and international authorities, on the other hand, Zara, like other fashion brands [36,37,38], seems to be starting to comply with the standards of sustainability requirements. When dealing with sustainability, the “fashion industry itself has to see themselves responsible if the change is to be carried out successfully, starting from production of raw materials to the reuse, recycle, repair and remake of garments and products” [39].

We will analyse the aspects of the sustainability policy from two points of view:

- Declarative, from Zara’s perspective;

- Factual, from the perspective of an educated consumer.

According to Zara’s own website, a visible direction of preoccupation for slow fashion is embodied by the Join life collection, which is presented as essential for meeting the eco conditions for water consumption; the fibres that are used are natural, suppliers also comply with these standards, and together with unions respect a policy that focuses on the worker. It is also about reducing the use of plastic, including for packaging and accessories.

- However, what is this collection made of?

- How sustainable is it?

- How transparent is it?

These are a few questions that we are trying to answer through our analysis.

The following analysis was performed on 40 garments in total, as follows—10 women’s dresses, 10 men’s trousers, 10 girls’ clothing items and 10 boys’ clothing items—which were randomly selected from the Zara Join Life collection advertised by Zara’s website as supporting sustainability, as a continuous project, integrating social and environmental sustainability and the health and safety of the products [40,41].

The study was conducted between July and August 2021, the products being randomly selected from Zara’s website.

For each of the 40 products, we analysed the following aspects:

- The Join Life collection sustainability criteria, as indicated by Zara’s website.

- The fibres the clothing items are made.

- The origin of the garments.

The analysed criteria were those that define the product as part of a series of sustainable clothes:

- -

- Sustainability towards the natural environment: care for fibres, care for water, composition of textiles/fibres, recycling capacity.

- -

- Sustainability towards economic environment: transport costs.

- -

- Consumer access to information, transparency of product information.

I.

The first component of our case study consists of the analysis of 10 garments (dresses), advertised by Zara’s website, https://www.zara.com/uk/en/join-life-woman-new-in-l2975.html?v1 (accessed on 26 July 2021) as part of the Join Life collection.

The conclusions are the following:

- Types of recycled fibres

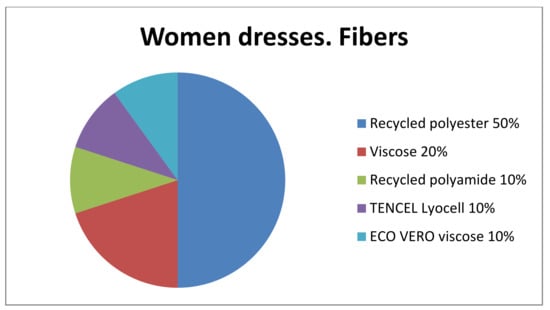

As seen in Figure 1, we have identified five recycled fibres that have been used in the manufacturing process of the analysed clothing items, as emphasised in the figure above.

Figure 1.

Percentage of recycled fibres used.

No natural fibre was used for the manufacture of the analysed clothing items. We used semi-synthetic fibres—viscose with its two forms: ECO VERO and TENCEL Lyocell—and two synthetic fibres—polyamide and polyester.

Six out of ten dresses were made of plastic and four were made of semi-synthetic fibres.

The percentages of recyclable fibres used are as follows:

- Viscose—between 55 and 100%.

- Recycled polyester—between 30 and 65%.

- Recycled polyamide—at least 30%.

- ECO VERO—at least 50%.

- TENCEL™ Lyocell—at least 40%.

- Future Recycling Capacity

When using a single type of fibre, the recycling capacity could beat its maximum value; this is the case of one product out of the ten that have been analysed. The recycling capacity is reduced for the other nine products.

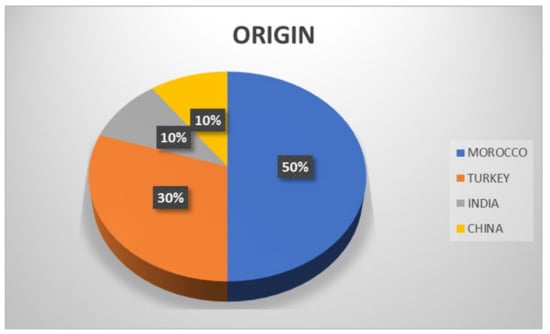

- Origin

As shown in Figure 2, we identified no supplier from Europe which could generate high costs with transport.

Figure 2.

Countries of fabrication.

Missing aspects: air quality, less energy usage, worker safety, fair wages, no child labour and no animal skin use.

II.

The second aspect of our case study consists of the analysis of 10 men clothing items/trousers, advertised by Zara’s website, as part of the Join Life collection.

The conclusions are the following:

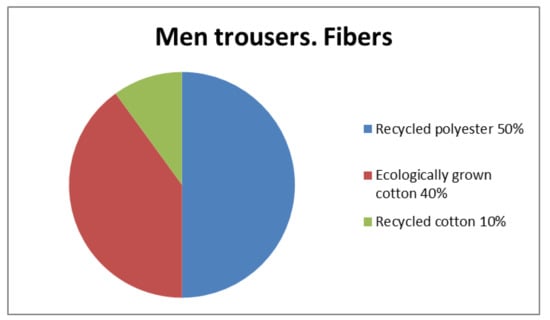

As shown in Figure 3, we have identified three recycled fibres that have been used in the manufacture process of the analysed clothing items, as emphasised in the figure below.

Figure 3.

Percentage of recycled fibres used.

- Types of recycled fibres

One product out of ten is made of one single fibre.

Most of the products, namely five, are made of synthetic fibres.

The percentage of recyclable fibres used are as follows:

- Recycled polyester—20–25%.

- Recycled cotton—20–25%.

- Ecologically grown cotton—50%.

Other complementary fibres used in addition to the recyclable ones are:

- Polyester—between 4 and 63%.

- Elastane—between 1 and 5%.

- Elastomultiester—7%.

- Viscose—between 32 and 56%.

- Cotton—100%.

- Future Recycling Capacity

Most of the products that were analysed, 9 out of 10, are composed of more than a single type of fibre, so they have low recycling capacities.

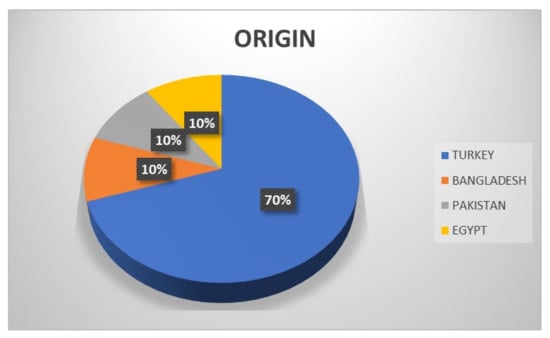

- Orign

As shown in Figure 4, all four countries of fabrication are outside Europe.

Figure 4.

Countries of fabrication.

Missing aspects: air quality, less energy usage, worker safety, fair wages, no child labour and no animal skin use.

III.

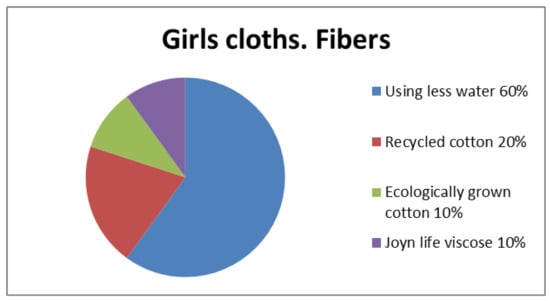

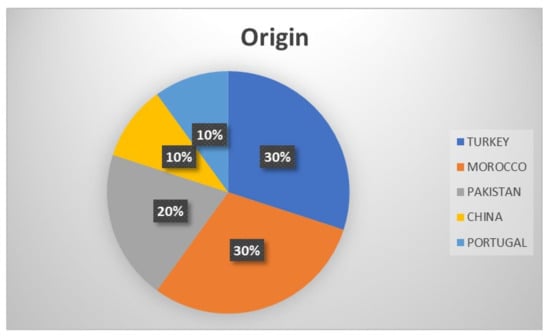

The thirds aspect of this study case consists of the analysis of 10 girls’ clothing items, advertised by Zara’s website, as part of the Join Life Kids collection.

The conclusions are the following:

As shown in Figure 5, we have identified the use of three recycled fibres for the ten clothing items that have been analysed, as emphasised in the figure above.

Figure 5.

Percentage of recycled fibres used.

The percentage of recyclable fibres used are as follows:

- Recycled cotton—15%.

- Ecologically grown cotton—60%.

- Join Life viscose—50%.

Other complementary fibres used in addition to the recyclable ones are:

- Cotton, elastan, viscose, polyester, nylon.

- Future Recycling Capacity

Most of the products, namely eight out of ten, are made of one single fibre, which increases the recycling capacity.

- Orign

According to Figure 6, just one of a total of five countries is from Europe.

Figure 6.

Countries of fabrication.

Missing aspects: air quality, less energy usage, worker safety, fair wages, no child labour and no animal skin use.

IV.

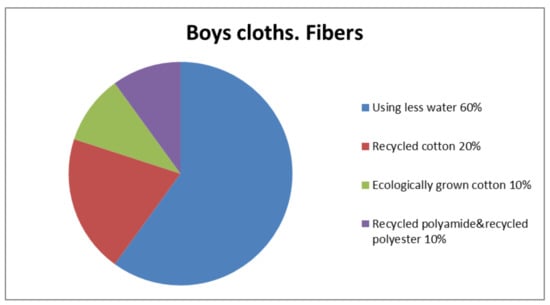

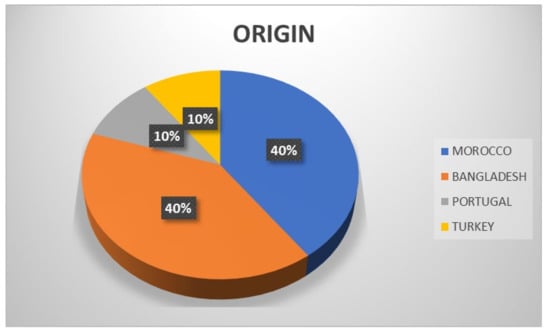

The fourth analysis was made on 10 boys’ clothing items, advertised by Zara’s website, as part of the Join Life Kids collection.

The conclusions are the following:

- Types of recycled fibres

As shown in Figure 7, we have identified four recycled fibres that have been used in the manufacture process of the analysed clothing items, as emphasised in the figure above.

Figure 7.

Percentage of recycled fibres used.

We identified two types of natural fibres and two types of synthetic fibres.

The percentage of recyclable fibres used are as follows:

- Recycled cotton—between 15 and 20%.

- Ecologically grown cotton—50%.

- Recycled polyamide—45%.

- Recycled polyester filling—100%.

Most of the products, nine. are made of a natural fibre—cotton—and only one is produced exclusively of a synthetic fibre.

Other complementary fibres used in addition to the recyclable ones are:

- Cotton, elastane, polyester, nylon.

- Future Recycling Capacity

Most of the products, nine out of ten, are made of one single fibre, which increases the recycling capacity.

- Orign

As shown in Figure 8, only one out of four countries of fabrication is from Europe.

Figure 8.

Countries of fabrication.

Since only one supplier out of four is from Europe, there could be high costs with regard to transportation.

Missing aspects: air quality, less energy usage, worker safety, fair wages, no child labour and no animal skin use.

5. Conclusions—Implications and Recommendations

Through this study, we aimed to analyse Zara’s Join Life collection in terms of sustainability and transparency, to make available to the Zara consumer who is concerned with buying sustainable fashion products a set of aspects to consider when wanting to buy responsibly, such as the product composition, the percentage of recyclable materials, its origin, etc. Consequently, we have set as a practical goal to generate a gradual change in Zara consumers’ behaviours, creating some basic skills that can transform them from a fast, superficial consumer into a slow, conscious one with decision-making power.

The analysis was made on 40 products (10 for women, 10 for men and 20 for kids), and the criteria that was considered was the following—the recycled fibres used; the recycling capacity; the origin of the products.

An important strength of the Zara Join Life collection in terms of sustainability is the use of recycled fibres which are indicated and described for each item.

When addressing the sustainability of a fibre we refer “to the practices and policies that reduce environmental pollution and minimise the exploitation of people or natural resources in meeting lifestyle needs [6].”

As for the weaknesses of the Join Life collection in terms of sustainability, we can mention the large use of synthetic and semi-synthetic fibres. Without synthetic fabrics “fast fashion probably wouldn’t exist. Synthetics are cheap, quick to produce and can be readily made order in exact quantities, colours and prints in time for the fortnightly, weekly, or even daily drops of new clothes. Synthetics make up well over 60% of a global fibre market that is growing” [4]. On the other hand, “natural fibres are at the heart of an eco-fashion movement that seeks to create garments that are sustainable at every stage of their life cycle, from production to disposal. Natural fibres have intrinsic properties such as mechanical strength, low weight and healthier to the wearer that has made them particularly attractive. Natural fibres have inherent properties, for example, mechanical quality, low weight and more beneficial to the wearer that has made them especially alluring [42].”

Other problems are clothes are made from a mixture of two or more fibres, which decreases the product recycling capacity, and that most products are manufactured outside of Europe, which involves additional shipping costs and could lead to pollution through transportation.

According to these findings, we conclude that the Join Life collection presents aspects of partial sustainability, but which can require corrective actions in the future by using recyclable fibres to a greater extent or choosing suppliers located at smaller distances from the retailer’s warehouses.

In terms of transparency, we found out that this collection partially meets this criterion, because much information provided by Zara’s website is general or difficult to access for the consumer.

According to one message that is advertised on Zara’s website, Join Life collection garments are

“produced with technologies that reduce water consumption in their production processes. The processes for dyeing and washing garments consume a large quantity of water. By operating with closed circuits, we can reuse water or implement technologies such as Ozone or Cold Pad Batch to help us reduce water consumption during these processes” [40,41].

As we noticed in our analysis, for many clothing items, especially those for kids, we encountered the factor care for water: produced using less water, but no other information regarding this aspect was found on the website. While there is no disclosure of the annual water footprint at the raw material level, the level of transparency for the consumer is quite low.

The water requirements in the textile industry are huge and the effects are disastrous. “A single pair of jeans requires 11.000 L of water. Moreover, most of the indigo used is now systhetic: chemicals used are released during manufacturing and dyeing often ends up in rivers and streams” [4].

Considering this global picture, we consider it essential for a consumer to be provided detailed information on the issues related to the use of water, especially for those products that are advertised as being produced with care for water.

At the same time, in terms of promoting human rights and avoiding the exploitation of people that work in textile industry, the information provided by Zara’s website is quite limited. What we find searching through its website is some general information according to which the company affirm that they “work with suppliers, workers, trade unions and international bodies with the aim of developing a supply chain that respects and promotes human rights, contributing to the United Nations sustainable development goals [40,41].”

When analysing Join Life collection garments, we find an indication regarding the country where the product was manufactured, but no indication concerning suppliers and raw material sourcing.

On the same topic of transparency, there is very little information on the website regarding the measures to improve the air quality or the workers’ safety, to ensure fair wages, to eliminate child labour or animal skin use.

A strength of the Zara Join Life collection in terms of transparency is the indication for each clothing item of the types of fibres that are used, the composition of the product and the statements about the sustainability policy. In addition, next to each product, there is a definition of each type of recycled fibre that was used to produce it.

For instance, Join Life viscose is defined by Zara’s website as being “obtained from more sustainably managed forests where trees are grown in a controlled manner, ensuring that primary and protected forests are respected, and as a part of programmes that guarantee reforestation” [40,41].

For the Zara fashion consumer that wants to make a change from fast to slow fashion, we propose the following three steps:

- The consumer should ASK himself, for example: Why do I buy this clothing item? Is it good for me? Do I need it? Am I addicted to it? Can I refrain from buying it?

- The consumer should read the label: What is it made of? Where does it comes from? Who produced it?

- The consumer should decide: I am a slow fashion consumer. I have my own contribution to slow fashion. I buy consciously.

6. Future Research

The results of the case study are important from two perspectives —Zara’s perspective, on the one hand, and the consumer perspective, on the other. Sustainability has now become a matter respected by all, and the solution must come from each party involved, insofar as each contributes to the spread of the natural disaster that is pollution.

One of the drawbacks of this research comes mainly from the lack of data on consumers of the Zara Join Life collection.

As a plus, there are chances that the behaviour Zara’s clothing consumer will become one in keeping with slow fashion because of the publication/dissemination/of this kind of study. The fashion consumer behaviour of the research team was changed towards the conscious significance and consumption of slow fashion, with the acquisition of the present data.

A future approach requires comparing other Zara collections with the Join Life collection, to identify their levels of sustainability.

Then, another study could customise the extent to which women are more attentive than men regarding the Join Life collection and who are the ones who buy sustainable clothes based on age, education, the rural/urban environment, etc.

Then, one can study to what extent parents know about the Zara Join Life collection and whether they prefer to buy children’s clothes from this collection.

Additionally, a comparative study between Zara fast fashion consumers from two different states would identify the consumer habits for drawing a portrait of the fast fashion consumer that could be transformed into a slow fashion consumer. The recycling and traceability of Zara clothes could be the subject of other research, starting from the retailer’s declaration concerning its business circularity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.G. and R.M.; Formal analysis, C.A.G. and R.M.; Investigation, C.A.G. and R.M.; Methodology, C.A.G. and R.M.; Resources, C.A.G. and R.M.; Writing—original draft, C.A.G. and R.M.; Writing—review & editing, C.A.G. and R.M. The authors both contributed equally. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ZARA. About Join Life. Available online: https://www.zara.com/us/en/z-join-life-mkt1399.html (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Joy, A.; Peña, C. Sustainability and the Fashion Industry: Conceptualizing Nature and Traceability. In Sustainability in Fashion; Henninger, C., Alevizou, P., Goworek, H., Ryding, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Muthu, S.S.; Rathinamoorthy, R. Sustainability and Fashion. In Sustainable Textiles: Production, Processing, Manufacturing & Chemistry; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Clair, K.S. The Golden Thread. How fabric changed history, Liveright Publishing Corporation; Liveright Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, O.; Fung, B.C.; Chen, Z. Young Chinese Consumers’ Choice between Product-Related and Sustainable Cues—The Effects of Gender Differences and Consumer Innovativeness. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, E. Luxury Fashion Brand Sustainability and Flagship Store Design. The Case of ‘Smart Sustainable Stores’. In The Water–Energy– Food Nexus; Gardetti, M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Learners Dictionaries. Fashion. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/fashion_1 (accessed on 28 July 2021).

- Lazăr, L. –Moda ca Fenomen Estetic si Formă de Comunicare. Available online: https://revista.amtap.md/wp-content/files_mf/159888321440.lazar.moda.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- DEFINIȚIA CELOR MAI IMPORTANȚI 10 TERMENI FOLOSIȚI ÎN INDUSTRIA MODEI SUSTENABILE. Available online: https://urbanitas.ro/definitia-celor-mai-importanti-10-termeni-folositi-in-industria-modei-sustenabile/ (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Berger-Grabner, D. Sustainability in Fashion: An Oxymoron? In Innovation Management and Corporate Social Responsibility. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance; Altenburger, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katherine Saxon- Fast fashion 2021 Guide. What It Means, Problems and Examples. 7 April 2021. Available online: https://thevou.com/fashion/fast-fashion/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- VOGUE BUSINESS. Sustainability. All Topics. Available online: https://www.voguebusiness.com/sustainability (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Rețeta prin care Zara câștigă războiul cu rivalii. Available online: https://www.digi24.ro/stiri/economie/reteta-prin-care-zara-castiga-razboiul-cu-rivalii-372520 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- ZARA. Join Life Collection. Woman–New Zara Origins. Available online: https://www.zara.com/uk/en/join-life-woman-new-in-l2975.html?v1=1883905 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Issuu. Fashion Revolution. Fashion Transparency Index, 2021 Edition. Available online: https://issuu.com/fashionrevolution/docs/fashiontransparencyindex_2021 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Bravo, L. How To Break Up With Fast Fashion: A Guilt-Free Guide to Changing the Way You Shop—For Good; Headline: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimaeki, K. Sustainable Fashion: New Approaches; Aalto University publication: Espoo, Finland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzo, A.; Abreu, M.J. Fast Fashion, Fashion Brands & Sustainable Consumption. In Fashion Brands and Sustainable Consumption. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binet, F.; Coste-Manière, I.; Decombes, C.; Grasselli, Y.; Ouedermi, D.; Ramchandani, M. Fast Fashion and Sustainable Consumption. In Fast Fashion, Fashion Brands and Sustainable Consumption. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandual, A.; Pradhan, S. Fashion Brands and Consumers Approach Towards Sustainable Fashion. In Fast Fashion, Fashion Brands and Sustainable Consumption. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annapoorani, S.G. Sustainable Textile Fibers. In Sustainable Innovations in Textile Fibres. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, B.L.; Villalobos, A.S. Sustainable Fashion. In Sustainable Fashion and Textiles in Latin America. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Gardetti, M.Á., Larios-Francia, R.P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Singh, P. Ethical Consumption Patterns and the Link to Purchasing Sustainable Fashion. In Sustainability in Fashion; Henninger, C., Alevizou, P., Goworek, H., Ryding, D., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, F.D. Ethics and consumerism: Legal promotion of ethical consumption. In The Ethics of Consumption; Röcklinsberg, H., Sandin, P., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Peloza, J. Can “Real” Men Consume Ethically? How Ethical Consumption Leads to Unintended Observer Inference. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 139, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonas, K.K. The Use of Recycled Fibers in Fashion and Home Products. In Textiles and Clothing Sustainability. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastran, A.; Colli, E.M.; Nor, H. Public Policy and Legislation in Sustainable Fashion. In Sustainable Fashion and Textiles in Latin America. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Gardetti, M.Á., Larios-Francia, R.P., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K. Ethical foundations in sustainable fashion. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2015, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niinimäki, K.; Karell, E. Closing the Loop: Intentional Fashion Design Defined by Recycling Technologies. In Technology-Driven Sustainability; Vignali, G., Reid, L., Ryding, D., Henninger, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S. A Circular Economy Approach in the Luxury Fashion Industry: A Case Study of Eileen Fisher. In Sustainable Luxury. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Gardetti, M., Muthu, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadicherla, T.; Saravanan, D.; Muthu, S.S.K. Polyester Recycling—Technologies, Characterisation, and Applications. In Environmental Implications of Recycling and Recycled Products. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2015; pp. 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liang, J.; Ding, J.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhu, B.; Gao, W. Microfiber pollution: An ongoing major environmental issue related to the sustainable development of textile and clothing industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 11240–11256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bick, R.; Halsey, E.; Ekenga, C.C. The global environmental injustice of fast fashion. Environ. Health 2018, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Plank, L.; Rossi, A.; Staritz, C. What Does ‘Fast Fashion’ Mean for Workers? Apparel Production in Morocco and Romania. In Towards Better Work. Advances in Labour Studies; Rossi, A., Luinstra, A., Pickles, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2014; pp. 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, P. Introduction to Fast Fashion: Environmental Concerns and Sustainability Measurements. In Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development; Shukla, V., Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H. Thematic Analysis of YouTube Comments on Disclosure of Animal Cruelty in a Luxury Fashion Supply Chain. In Sustainability in Luxury Fashion Business. Springer Series in Fashion Business; Lo, C., Ha-Brookshire, J., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardetti, M.Á. Sustainability in the Textile and Fashion Industries: Animal Ethics and Welfare. In Environmental Concerns and Sustainable Development; Shukla, V., Kumar, N., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J.; Cheng, R. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in the Slow-Fashion Industry. In Sustainable Fashion Supply Chain Management; Choi, T.M., Cheng, T., Eds.; Springer Series in Supply Chain Management: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J.; Cheng, R. Communicating Sustainability: The Case of Slow-Fashion Micro-organizations. In Sustainable Consumption. The Anthropocene: Politik—Economics—Society—Science; Genus, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 3, pp. 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X. How the Market Values Greenwashing? Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 547–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Blanco, S.; Romero, S.; Fernandez-Feijoo, B. Green, blue or black, but washing–What company characteristics determine greenwashing? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E. Environmental Sustainability in the Textile Industry. In Sustainability in the Textile Industry. Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Muthu, S., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 17–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).