Abstract

The end of poverty is the first of the 17 sustainable development goals of the United Nations. Universities are strategic spaces for promoting the SDGs, from training, research, and outreach capacity to implementing sustainable actions, helping to reduce inequalities and, significantly, promoting sustainable cities and communities. This article aims to answer how the Public University of Navarre contributes to promoting the 1st SDG, what mechanisms for the end of poverty endorses in its territory, and what can we learn from these experiences. To this end, a case study has been carried out based on qualitative techniques. This work analyzes the strategies implemented, such as incorporating social clauses for responsible recruiting, the development of applied research and teaching or network participation. From this example, some engaging lessons will be extracted to address this issue in other contexts, promoting their consolidation and identifying the obstacles that may hinder their spread.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is one of the main challenges our societies faces. However, as [1] point out, sustainability must be understood on a triple environmental, financial and social basis.

In September 2015, the United Nations (from now on UN) presented the document “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, which had the unanimous support of world leaders. This agreement implied a new international agenda that, from 1 January 2016, should aim at advancing in the fulfilment of the 17 objectives for the year 2030. This path, classified as one of the most relevant global agreements in our recent history, aspires to progress in an alliance towards a more sustainable future. Therefore, the 2030 agenda has become a horizon from state to local, for public institutions, companies, organisations, and also for universities.

Ending poverty in all its forms is the first of these objectives (from now on SDG1), and the UN defines it not only as a human rights problem that affects hunger but also as the absence of opportunities, limited access to essential services and social participation [2]. Furthermore, a European consensus agrees on using the AROPE indicator (At risk of poverty or social exclusion) to measure this phenomenon. This indicator compiles the population who are either at risk of poverty, materially and socially deprived or living in a household with a very low work intensity (Those people who live with a low income (taking as a threshold 60% of the median equivalent income), who suffer from severe material deprivation (at least 4 of the nine defined elements) and/or those who live in households with very low or no employment intensity (in a household with two adults it is equivalent to only one person working part-time). [3]. This is the primary indicator to monitor the goal of the 2030 horizon. As a result, the fight against poverty implies building a more just and inclusive society and contributing to eradicate the inequalities present in our societies [4]. The UN [2] encouraged that the different social agents must work towards this objective, involving their environment and their own capacity for action to promote inclusive growth, responsible and sustainable consumption and promote a fairer society with opportunities for all people. In the search for answers to these complex challenges, the universities’ role has become a key component [5,6] so are influential spaces with leadership capacity and influence in decision-making life [7].Moreover, universities offer a wide variety of academic services to their territory, not only because of their educational potential, also because of their research capacity, their opportunities for sustainable governance and the projection they develop in their territories through volunteer actions and engagement, among others [8,9].

In this sense, they have the ability to advance towards the goals that the UN [2] attributes to SDG1 through its four main lines of action. (1) Its productive capacity can contribute to students applying this approach to all their professional activities. (2) Moreover, its research potential supports innovation to build a more sustainable society, disseminate results, promote debates on poverty’s consequences, and participate in developing strategies and inclusive regulations. (3) The territory outreach of universities makes them leaders in promoting public-private alliances, offering to volunteer, cooperating with the environment, accompanying sustainable growth models, and helping social economy companies. (4) Finally, its internal policy also has the capacity to create a more inclusive university model towards its community, preventing poverty from being a reason for dropping out, promoting equality policies, responsible consumption and the promotion of social clauses on businesses.

The literature review shows that a good part of these actions has been analysed from the social responsibility perspective at the university [6,10]. However, universities have other opportunities in teaching, research and attention to their students that must be analysed. Similarly, the studies found on the contribution of SDG1 tend to present isolated experiences in some of the lines of action, especially in teaching and research [11,12,13]. This study aims to address this research gap by conducting a case study that comprehensively addresses the four lines of action of universities: teaching, research, their relationship with the local environment and their internal policies.

This research aspires to answer this question: How does the Public University of Navarre contribute to SDG1? The study aims to identify the actions the university develops, how they could be increased and what obstacles it might encounter. This work is based on the hypothesis that although this university develops isolated actions contributing to this objective, aligning all of them would allow dimensioning its scope, communicating its contribution and identifying those present challenges. Thus, this networking power requires having a receptive environment, which works in a bidirectional alliance between the university and society, so that the actions to be carried out correspond and are adapted to the needs of the context [14].

The Public University of Navarre (from now on UPNA) was born 33 years ago in Navarre, a northern Spanish region. It currently has 8431 students, 1104 research faculty, offers 31 undergraduate degrees and 29 master’s degrees, collaborates with 385 companies and public institutions in the territory on the teaching and research framework, and has trained almost 40,000 graduate students [15]. This university is located on three campuses, two in its capital, Pamplona, and a third campus in the 2nd city, Tudela, located in the southern part of the region. This implies that the university’s presence is divided into two geographic areas of reference, the South and the North. Since its inception, the Public University of Navarre tried to generate strong links with its territory. The regional proximity and size of its university allowed for closer ties with the environment and generated a dynamic contribution to the economic and social development of the area. As a result, in 2020, this institution topped the Knowledge and Development of universities ranking as the centre that most contributed to the regional development of universities in Spain [16].

The results of this case study aspire to be of use to the scientific and professional community comprehending how this university contributes to SDG1 from all its lines of action. Leal Filho et al. [12] argue that the systematisation of experiences like these contributes to the international expansion of the university’s role as platforms for learning and experimentation. Sharing the results, strategies and difficulties support the transfer of knowledge between territories to discover new experiences, learn from them, and encourage other universities and companies to contribute to the fight against poverty from their territories.

2. State of the Research: The University as the Engine for Local Sustainable Development, Strategies and Experiences in the Implementation of SDG1

There is a vast literature that addresses the role of universities in the development of their environment. Through a scoping review of the scientific production on the contribution of universities to the SDGs, a high volume of more than 97,000 entries were detected in the Scopus and Google Scholar search engines. According to Manchado Garabito et al. [17], this approach collects and identifies the literature developed around this topic to identify the status of the debate and works contributing to it. However, given this large volume of contributions, it was necessary to narrow down the search. Following the proposal of Arksey and O’Malley [18], a specific search was carried out in the Scopus and Google Scholar search engines for the two concepts SDGs and universities or SDGs and university, also obtaining a significant volume of literature with a total of 23,625 documents. The choice to combine both search engines is due to the fact that the first access a significant volume of freely reachable information, facilitating access to other types of non-scientific reports that were of interest to the object of study. On the other hand, Scopus identifies scientific articles and allows filtering them throughout more categories (area, year, open access). This search identified the literature on “USR—University Social Responsibility” as a fundamental framework for developing this approach. Thanks to this finding, the literature review in this field found necessary studies close to this work’s objective. The searches were carried out between March 1st and May 25th, 2021. A new selection of cases was made from these results, adding the following descriptors: SDG1 AND poverty AND university OR universities, narrowing the search down significantly into 1310 texts in Google Scholar and 23 in Scopus. The final selection of bibliography was made from Scopus’ search and a descending date range in Google Scholar.

This volume of literature confirms that there is already a broad consensus that the social responsibility of universities towards their community should be the driving force behind their action. For Shek et al. [19], universities’ social responsibility allows universities to improve their environment by promoting their development. Universities have different functions such as teaching, research, institutional governance or social leadership. This definition transcends the traditional social responsibility of companies since it is argued that universities should contribute to improving the quality of human life and addressing the needs of society [20,21].

This commitment has a global vision since several networks have progressively contributed to this objective. Some of them stand out, such as the University Social Responsibility Network (USRN), the Global University Network for Innovation (GUNI) or the Talloires Network of Engaged Universities [6,7].

Despite this optimistic scenario in terms of outreach and environmental commitment, Hollister et al. [10] point out the difficulties in achieving this change in universities’ culture, especially in teaching and research. However, in the last decade, essential steps can be seen. The literature consulted indicates that the Sustainable Development Goals have been an excellent framework for universities’ potential with their environment [14].

The reviewed studies identify numerous initiatives developed worldwide advancing on the SDG’s agenda through different university lines of action: teaching, research and local environment outreach, but also in their own policies. Specifically, in promoting SDG1, numerous universities have previous and interesting experiences to strengthen this study.

2.1. University Experiences for the SDGs Contribution

In general terms, numerous investigations tried to identify the progress of the SDGs in universities through case studies or various surveys. Leal Filho et al. [12] conducted a vital survey worldwide to assess the degree of SDG implementation. They measured official teaching actions and other possible training actions such as conferences, courses, and research activities. It should be noted that the sample compiled 165 cases from 17 countries and five continents. Even though the people surveyed showed broad awareness about the SDGs, the figures decreased in the teaching application, with only 32% fully applying the SDGs in their classes.

Chang & Lien [22] carried out another engaging experience mapping the degrees offered at the National University of Kaohsiung in Taiwan and their relationship to the SDGs. The analysis identified the potential that universities have in the SDGs capacity building, encouraging incorporating this approach in the planning, design, and classification of the degrees offered. The conclusions outline the interdisciplinary potential of universities to advance within the 2030 agenda, although they highlight that it is barely exploited.

Experiences such as the University of Winchester designing formulas to integrate and evaluate sustainability in the curricula have also been detected [23,24]. In the same way, Nhamo & Mjimba [25] pointed out that their environments’ socio-economic and environmental sustainability can only be achieved if students capable of dealing with it are trained. For this reason, they highlighted some transversal initiatives in the revision of the curricula initiated in some African countries such as South Africa, Zimbabwe and Nigeria.

This comprehensive competency approach, also analysed by Franco, et al. [26], states that, in addition to formal curricular activities, the SDGs can be integrated into other university dimensions such as research, internships, volunteering or other additional training activities. In fact, Mawonde & Togo [27] noted that, in work placement experiences, students had much more opportunities to implement the SDGs than in classrooms.

Nonetheless, attending the university is more than a professional training process; students can acquire other competencies that train them in SDGs [28]. This approach, which goes beyond the knowledge field training view, recognises the comprehensive training capacity of universities and encourages these higher education institutions to address the SDGs in all university actions. Universities are the future leaders, and this has the potential for a transformative process on a larger scale in the promotion of the SDGs in general and the fight against poverty in particular [29].

Finally, in terms of outreach and alliances with the environment, there is a broad consensus on the importance of aligning civil society, business and the scientific community [14]. Some studies also stand out in this field. On the one hand, Mori Junior et al. [30] identified an interesting experience to promote this approach. On the other hand, through a systematisation and communication of experiences, the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) (Melbourne, Australia) motivated greater awareness and collaboration on and off-campus.

2.2. Experiences and Strategies for Implementing the SDG1 in Universities

Specifically, in SDG1, training has been detected as a valuable way to eradicate poverty [11]. Komba [31], a study conducted at the Moshi Cooperative College and the Open University of Tanzania identified that education reduced the disadvantage and poverty of its students. For this reason, they have supported the training of disadvantaged students as a strategy to fight poverty.

Along these lines, the Open University of Britain (OUB) has put much effort into this objective to promote training in SDGs [32]. For example, through the project “Transformation through Innovation in Distance Education (TIDE)” in alliance with other universities in the UK and Myanmar, they encouraged the training of poor or disadvantaged students. This experience demonstrated how access to training promoted economic development and employment opportunities.

Also, a study carried out by Abimbola et al. [33] in Nigeria examined how a training strategy aimed at women at the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN), facilitated their access to higher education, allowed progress in the fight against poverty of this group and fostered gender equality (SDG5).

A large part of these results belongs to developing countries. In this sense, Leal Filho et al. [12] identified the lowest level of SDG1 teaching implementation (28%) in Europe, while in other countries it was almost double (North America 53%, South America 39%, Africa 39%, Asia 52% and Oceania 50%). Nhamo & Mjimba [25] show that the University of Sydney has tried to advance in training oriented to SDG 1. Also, the European University of Helsinki is gradually reviewing the internal organisation to align with sustainable objectives. In this case, up to now, some progress has been made by linking teaching and research to objectives such as partnerships (17th), quality education (4th), and health and well-being (3rd). However, there is still a long way to go in others, such as the end of poverty (1st).

There are other lines of action, aligning teaching with research, that also stands out. Hoeltl et al. [13] examined an Ethiopian research experience funded by the Erasmus + project “Social Inclusion and Energy Management for Informal Urban Settlements”. This led to an alliance between European and Ethiopian universities to address the SDGs in the training of future professionals in architecture, urban planning, and the social sciences. This project also involved other public actors and civil society, achieving progress in different objectives, SDG1 among them.

Another example of this is the Federal University of Agriculture (Abeokuta, Nigeria) (FUNAAB), where training, advice, and dissemination of some agricultural technologies have been designed to effectively address rural communities’ development challenges. This experience has increased agricultural productivity, contributing to the reduction of poverty and hunger [25].

Following the outreach goal, Lehoux et al. [34] also conducted another valuable experience, where 105 health innovations were identified in the United States and other countries in Africa, Central and South America, and South Asia. None profits networks, organisations, universities and volunteers were among the promoters. As a result, they found that 15% of these projects contributed to advancing SDG1. Experiences like these illustrate how the university’s connection with society allows many practical advances [12].

Finally, actions regarding internal university policies have also been detected. The University of South Africa (UNISA) identified how digital training had negative consequences for the most impoverished population. Those with Internet connection difficulties were at risk of exclusion and faced learning obstacles [35]. To this end, the university offered help to the most disadvantaged students through a reliable internet connection, promoting their access to quality education and to avoid dropping out of studies, critical issues in the fight against poverty.

This literature review has identified important advances through the experiences of numerous universities. These studies recognise four possible lines of action in the implementation of SDG1, teaching, research, projection and internal policies, constituting the analysis framework this study will be based on. However, although there is a certain consensus on the potential of universities, these studies also recognise that these institutions face substantial challenges. On the one hand, they must reconceptualise a good part of their activities and objectives, incorporating the SDGs into the entire governance of the university [14]. On the other hand, Franco et al. [26] and Mawonde &Togo [27] point out that to promote these approaches and retain the entire scientific community, there is a need for facilities and incentives to motivate their implementation. Therefore, despite these concrete advances and the consensus in the literature, it is necessary to incorporate this approach into the structure, study plans, research initiatives and promote spaces for exchange and discussion for alliance consolidation [9]. Following this reflection, the case study aims to obtain results on this 4 actions that participate and influence the current debate.

3. Methods

A qualitative case study has been chosen to answer the research question. This method’s choice is because this technique allows us to explore in-depth a phenomenon inserted into a specific context from the different sources of information and testimonies [36,37]. The case study is a widely used method in qualitative research [38,39].

Sometimes this method has been questioned for its interpretive character. However, Greener [40] and Enrique and Barrio [41] argue that this method allows the researcher to analyse the problem in depth from the different key informant testimonies. Chetty [42] confirms its usefulness for an investigation that does not intend to produce generalisations but to know a specific phenomenon exhaustively.

In the field of organisational’ research, it is also a valuable and valuable method. Rashid, et al. [43] identify, based on different studies in this area, four critical phases to apply this methodology to the case study in organisations: (1) understanding the phenomenon from different sources, (2) the design of the method and selection of key informants, (3) the exploration and understanding of the phenomenon from the different selected testimonies and (4) the case analysis description.

Following this method, this case study has been developed in 4 phases [Table 1]. The first has approached the phenomenon through a theoretical and statistical review of the object of study through different secondary sources. On the one hand, the academic literature review related to the SDGs at the university level, including a selective search for specific experiences on the contribution to SDG 1. On the other hand, a quantitative approach to the object of study by analysing secondary statistical sources through the Foessa Survey and the Labor Force Survey. This analysis was conducted in March 2021.

Table 1.

Empirical work and methods.

The second phase contains the qualitative analysis method taking the purposive sampling strategy based on the key informant selection [44]. Within the scope of nonprobability sampling techniques, this choice selects informants who, due to their place in the institution or society, provide a qualified vision of the object of study [45]. This method has been used in different areas of knowledge with valid results [46,47].

The method does not intend to obtain results that can be applied generally but to thoroughly know the selected phenomenon. Therefore, in the testimony analysis, the context of the experience must be taken into account for a suitable interpretation [48].

For the sample characteristic identification, concepts addressed in the literature were used and the priority focused on the search for profiles with experience in teaching, research, projection, internal policies and the fight against poverty in the region.

The result is a sample of 10 key informants whose experience is necessary to reinforce this case study. To obtain these testimonies, two qualitative research techniques have been combined. On the one hand, in-depth interviews for profiles in the field of university management. People responsible for the design of institutional policies, the management of procedures, the attention to the university community living in poverty, and the teaching and research activities stand out. On the other hand, the focal group technique for crucial informants in the professional and political sphere of poverty in Navarra. Its content focused on the university’s role in contributing to this field, the characteristics and inclusion barriers of people living in poverty, and the opportunities for alliances. The characteristics of the sample are specified below [Table 2]:

Table 2.

Characteristics of the sample.

The qualitative empirical work, developed in phase 3, was completed with the study of significant regulatory documentation and the statistical analysis of the data on financial aid for students living in poverty. Obtaining this information was facilitated by the informants. This fieldwork was carried out between January and June 2021. Finally, phase 4 comprises the testimony analysis supported by the literature and has identified a variety of needs, obstacles, and challenges for the promotion of SDG1 actions.

5. Discussion

The results have identified how the Public University of Navarre contributes to SDG1. In addition to recognising its contribution, this case study had the objective of uncovering obstacles and challenges for SDG1.

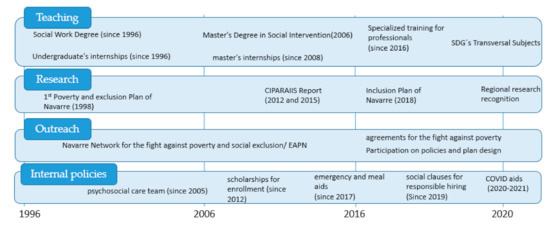

The search for actions through empirical work has been based on the four strategic lines of action identified in the literature: teaching, research, projection and internal policies. The latter is a way of demonstrating whether the university, beyond the current actions, can build and extrapolate an internal care model according to the bases of SDG1.

This work’s first evidence is verifying that the university contributes to SDG1 prior to the UN 2030 agenda [2]. This brings up the actions already developed trying to establish a link with the territory but also the lack of a management framework. Fleacă, et al. [14] and Franco, et al. [26] confirm that although universities play a key role in promoting and leading the 2030 agenda, a good part of the actions carried out are isolated or disconnected. To advance in the measurement of this contribution, it is necessary to include the governance approach.

In 2019, the Public University of Navarre implemented the 2030 Agenda horizon through its Strategic Plan (2019–2023) [62]. This initiative laid the foundations to advance in the contribution to the 17 sustainable development goals. This new Strategic Plan could be the first framework to encompass these actions. As a result, a compilation of the different actions being developed has started, together with discussing possible alliances with NGOs or the participation in regional development networks. Still, there is a long way to go.

The second line of discussion relates to teaching. The results have identified that UPNA contributes to intersectional training in SDG1s from the different knowledge areas through its pilot experience on transversal subjects. Chang & Lien [22] encouraged universities to classify their training and to promote interdisciplinary networks that endorse the SDGs from different areas of knowledge. This is a substantial challenge for all universities, as it requires training teachers and reviewing all study plans. In this sense, the UPNA’s experience in transversal competencies is also one of the recommendations indicated by Dlouhá, et al. [28]. Nevertheless, the great challenge will be reviewing all study plans and syllabuses to integrate and evaluate sustainability, as has been done, among others, at the University of Winchester [23,24].

Third, although the impact on research has been very notable, it could be increased if multidisciplinary workspaces are generated, as recommended by other studies. There is still a long way to advance in the generation of knowledge on how to face SDG1 from a multidisciplinary perspective. Universities have the potential to contribute to this from their various disciplines, but it is vital to create spaces and encourage interdisciplinary work, as recommended by Chang & Lien [22].

Regarding its outreach scope, UPNA has demonstrated its leadership capacity to promote alliances targeted at SDG1. In addition, according to Leal Filho et al. [63], this network presence leads and co-creates new innovative formulas that contribute to the 2030 agenda. However, the lack of formal guidelines and the low recognition of these participations reduces their impact. The need for incentives that encourage faculty to enhance the research link to the local territory has also been detected [26].

Finally, the Public University of Navarre has sought to promote the SDG1 by setting an example for other institutions. We have identified financial aid for disadvantaged students and responsible hiring. Also, internet connection support reducing the digital divide, as Letseka and Pitsoe [35] identified in UNISA. Although the former has managed to consolidate, it faces the emergence of new profiles that increasingly require social and psychological support. This is, therefore, an aspect that must be reinforced.

Concerning the sustainable recruiting practice, it is required that responsible purchasing is established as a principle in the university from the policy management in addition to a favourable regulatory framework. In addition to the new clauses, the Public University of Navarre must advance measuring impact indicators, data recording, and disseminating this philosophy. This requires the approach to be incorporated into the strategic policy of the university, overcoming the bureaucracy and establishing it as a guiding principle in university action, same as teaching, research, etc. Governance in universities is complex since a large part of decision-making falls on faculties and departments. It is, therefore, necessary that this approach be permeated in the general service hiring of the university. In this sense, the Public University of Navarre has a long way to implement this philosophy in all faculties and departments. Hence the need to mainstream and implement this principle in the general university practice.

In the same way, perhaps the university’s role does not have to be limited only to the contracting of services from these companies. If employment creation in some services is so complex, perhaps the development strategy of these companies can come from other forms of alliances despite the consequent regulations. An example would be the universities endorsement of companies into sectors with the highest demand for employment, such as care, renewable energy or information technologies. In these fields, universities can technically complement these companies for their innovation, professional training or the search for new employment niches. In addition, universities have researchers and personnel training to advise and develop studies on transferring research contracts at no economic cost, end-of-studies projects, etc. These formulas would be a good way also to develop the social commitment of the universities. Therefore, a triple alliance where public administrations hire, universities assist in innovation, and social enterprises create employment can be an excellent formula to increase SDG1′s contribution and transcend the limitations mentioned above. Despite these advances, the Public University of Navarre has a long way to go in implementing this philosophy throughout governance. Hence, the need to mainstream and implement this principle in all university practice is unavoidable [14,26].

6. Conclusions

This case study carried out at the Public University of Navarre has identified the University’s contribution to SDG1 and how to increase its impact.

Concerning teaching, UPNA maintains a high potential for professional training at specific bachelor’s and master’s levels in this field of poverty. In the same way, the university frequently designs specialised courses for working professionals. Next year, in line with the literature recommendations, UPNA will work to develop crosscutting SDG1 training for all students.

In regards to research, UPNA has a long history of research in the study of poverty and social exclusion in Navarre. As a result, it has participated in designing the different government inclusion plans for the territory. However, the lack of an access framework has been an obstacle to promoting new lines of research that could support SDG1.

Finally, from the outreach field, the university has developed two parallel lines of action. On the one hand, the participation and promotion of networks and alliances, such as the Network to Fight poverty in the region or the consolidation of collaboration agreements with the social and business network. On the other hand, it has not neglected internal action, preventing poor students from abandoning their studies through financial aid and developing a framework of action for responsible contracting services. This last experience is not without obstacles, encouraging the relaunch of other collaboration formulas with companies and entities of the third sector from the field of applied research for SDG1.

These results place the challenges to increase the impact on SDG1 of the Public University of Navarre in the same line as the literature review. The necessity of improving an institutional governance framework that supports, registers and promotes actions aimed at sustainable development. Likewise, UPNA should address each of the objectives from a multidisciplinary perspective, a challenge identified in this case study also in the field of SDG1. Finally, although the design of training towards transversal competencies is recognised, this approach should be incorporated into designing and evaluating all study plans.

Identifying and assessing the above data made it possible to structure all the actions that have contributed to SDG1. This is also happening to other universities, where social responsibility actions are often isolated and disconnected within the institution itself [26]. Nonetheless, the SDG framework is an opportunity to measure this contribution, encourage development and target new development paths. This work has tried to contribute to this.

This journey substantiates the Public University of Navarre as an active agent searching for formulas and public-private partnerships that combat such complex problems as poverty and social exclusion. A recent study comparing the development of inclusion policies in Spain points to this alliance, in which the university has played a central role, as the key to having advanced models in the end of poverty [64].

However, there is still a long way to go. The literature examination demonstrates that the challenges of universities regarding sustainable development objectives are consolidated in a crosscutting way in their teaching, research, university outreach actions and internal policies. In this sense, social commitment and academic excellence must walk together; otherwise, it will not be easy to find a balance that rewards and recognizes the contribution of the different Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 agenda.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.-V. and B.P.-E.; methodology, L.M.-V. and B.P.-E.; formal analysis, L.M.-V. and B.P.-E.; investigation, L.M.-V. and B.P.-E.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.-V. and B.P.-E.; writing—review and editing, L.M.-V.; supervision, L.M.-V. and B.P.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

For more information: https://www.unavarra.es/unidadaccionsocial/programa-de-orientacion-social?languageId=100000 (accessed on 27 March 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Developments Goals Report; United Nation: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/ (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Eurostat. Glossary: At Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion (AROPE). 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Glossary:At_risk_of_poverty_or_social_exclusion(AROPE) (accessed on 8 July 2021).

- OECD. Estudios Económicos de la OCDE [OECD Economic Studies]; OCDE: Madrid, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/economy/surveys/Spain-2018-OECD-economic-survey-vision-general.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2021).

- Herrera, A. Social responsibility of universities. In Higher Education at a Time of Transformation: New Dynamics for Social Responsibility; Global University Network for Innovation, Ed.; GUNI/Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilescu, R.; Barna, C.; Epure, M.; Baicu, C. Developing university social responsibility: A model for the challenges of the new civil society. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 2, 4177–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, L.M.; Hollister, R.M. Moving beyond the ivory tower: The expanding global movement of engaged universities. In Higher Education in the World 5: Knowledge, Engagement and Higher Education: Contributing to Social Change; Global University Network for Innovation, Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Ketele, J.M. The social relevance of higher education. In Higher Education at a Time of Transformation: New Dynamics for Social Responsibility; Global University Network for Innovation Ed.; GUNI/Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W. Universities, Sustainability and Society: A SDGs Perspective. In Universities, Sustainability and Society: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (ss. 555–560); Teoksessa, W., Leal Filho, A.L., Salvia, L., Brandli, U.M., Azeiteiro, U.M., Pretorius, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister, R.M.; Pollock, J.P.; Gearan, M.; Reid, J.; Stroud, S.; Babcock, E. The Talloires Network: A global coalition of engaged universities. J. High. Educ. Outreach Engagem. 2012, 16, 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Oluchi, U.F. The role of open and distance education in national development of Nigeria. Int. J. Innov. Psychol. Soc. Dev. 2018, 6, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeltl, A.; Brandtweiner, R.; Bates, R.; Berger, T. The interactions of sustainable development goals: The case of urban informal settlements in Ethiopia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleacă, E.; Fleacă, B.; Maiduc, S. Aligning Strategy with Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Process Scoping Diagram for Entrepreneurial Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UPNA, Universidad Pública de Navarra. Estadísticas del Portal de Transparencia [Transparency Portal Statistics]. 2020. Available online: https://www.unavarra.es/portal-transparencia/ (accessed on 14 April 2021).

- Fundación CYD. Resultados del Ranking Conocimiento y Desarrollo de las Universidades Españolas [Results of the Knowledge and Development Ranking of Spanish Universities]. 2020. Available online: https://www.rankingcyd.org/resultados-del-ranking-cyd/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Manchado Garabito, R.; Tamames Gómez, S.; López González, M.; Mohedano Macías, L.; D’Agostino, M.; Veiga de Cabo, J. Revisiones Sistemáticas Exploratorias [Systematic Exploratory Reviews]. Med. Y Segur. Del Trab. 2009, 55, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. Theory Pract. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Yuen-Tsang, A.W.K.; Ng, E.C.W. USR Network: A Platform to Promote University Social Responsibility. In University Social Responsibility and Quality of Life. Quality of Life in Asia; Shek, D., Hollister, R., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.R.; Fitzgerald, H.E. Engaged scholarship: Historical roots, contemporary challenges. In Handbook of Engaged Scholarship: Contemporary Landscapes, Future Directions; Fitzgerald, H.E., Burack, C., Seifer, S.D., Eds.; Michigan State University Press: East Lansing, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D.; Hollister, R.M.; Stroud, S.E.; Babcock, E. The Engaged University: International Perspectives on Civic Engagement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.C.; Lien, H.-L. Mapping Course Sustainability by Embedding the SDGs Inventory into the University Curriculum: A Case Study from National University of Kaohsiung in Taiwan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, C.; Smith, N.; Cantarello, E. Aligning Campus Strategy with the SDGs: An Institutional Case Study. Universities as Living Labs for Sustainable Development: Supporting the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (ss. 11–27); Teoksessa, W., Leal Filho, A.L., Salvia, R.W., Pretorius, L.L., Brandli, E., Manolas, F., Alves, U., Azeiteiro, J., Rogers, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NUS. Universities Committed to Responsible Futures. 2017. Available online: https://sustainability.nus.org.uk/responsible-futures/articles/universities-committed-to-responsible-futures (accessed on 24 May 2021).

- Nhamo, G.; Mjimba, V. The Context: SDGs and Institutions of Higher Education. In Sustainable Development Goals and Institutions of Higher Education (ss. 1–13); Teoksessa, G., Nhamo, G., Mjimba, V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, I.; Saito, O.; Vaughter, P.; Whereat, J.; Kanie, N.; Takemoto, K. Higher education for sustainable development: Actioning the global goals in policy, curriculum and practice. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 1621–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawonde, A.; Togo, M. Challenges of involving students in campus SDGs-related practices in an ODeL context: The case of the University of South Africa (Unisa). Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlouhá, J.; Heras, R.; Mulà, I.; Salgado, F.P.; Henderson, L. Competences to Address SDGs in Higher Education—A Reflection on the Equilibrium between Systemic and Personal Approaches to Achieve Transformative Action. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Jardali, F.; Ataya, N.; Fadlallah, R. Changing roles of universities in the era of SDGs: Rising up to the global challenge through institutionalising partnerships with governments and communities. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2018, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, R., Jr.; Fien, J.; Horne, R. Implementing the UN SDGs in Universities: Challenges, Opportunities, and Lessons Learned. Sustainability 2019, 12, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komba, W. Increasing education access through open and distance learning in Tanzania: Acritical review of approaches and practices. Int. J. Educ. Dev. Using ICT 2009, 5, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, A. Open education and the sustainable development goals: Making change happen. J. Learn. Dev.-JL4D 2017, 4, 275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola, A.E.; Omolara, W.O.O.; Fatimah, Y.T. Assessing the impact of open anddistance learning (ODL) in enhancing the status of women in Lagos state. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 174, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lehoux, P.; Pacifico Silva, H.; Pozelli Sabio, R.; Roncarolo, F. The unexplored contribution of responsible innovation in health to sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letseka, M.; Pitsoe, V. The challenges and prospects of access to higher education atUNISA. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 1942–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: London, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Baskarada, S. Qualitative case study guidelines. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Yazan, B. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- Greener, S. Business Research Methods; Ventus Publishing ApS: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Enrique, A.M.; Barrio, E. Guía para implementar el método de estudio de caso en proyectos de investigación. In Propuestas de Investigación en Áreas de Vanguardia; Editorial Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- Chetty, S. The Case Study Method for Research in Small-and Medium-Sized Firms. Int. Small Bus. J. 1996, 15, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Y.; Rashid, A.; Warraich, M.A.; Sabir, S.S.; Waseem, A. Case Study Method: A Step-by-Step Guide for Business Researchers. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faifua, D. The key Informant Technique in Qualitative Research. In SAGE Research Methods Cases; SAGE publishing: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongco, M.D.C. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlearney, A.S.; Walker, D.; Moss, A.D.; Bickell, N.A. Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Key Informant Interviews in Health Services Research: Enhancing a Study of Adjuvant Therapy Use in Breast Cancer Care. Med. Care 2016, 54, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Olabuenaga, J. I Metodología de Investigació Cualitativa [Qualitative Research Methodology]; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- INE, Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Estadística de Contabilidad Regional [Regional Accounting Statistics]. 2019. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prensa/pib_prensa.htm (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Nastat, Instituto Navarro de Estadística. Encuesta de Población Activa [Labor Force Survey]. 2020. Available online: http://www.navarra.es/home_es/Gobierno+de+Navarra/Organigrama/Los+departamentos/Economia+y+Hacienda/Organigrama/Estructura+Organica/Instituto+Estadistica/NotasPrensa/EncuestaPoblacionActivaNavarra.htm (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Foessa, Report. Informe Sobre Exclusión y Desarrollo Social en Navarra [Report on Exclusion and Social Development in Navarre]; Fundación Foessa: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://caritas-web.s3.amazonaws.com/main-files/uploads/sites/16/2019/10/NAVARRA-VIII-Informe-FOESSA.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Laparra, M.; Pérez-Eransus, B. Exclusión Social en España. In Un Espacio Diverso y Disperso en Intensa Transformación [Social Exclusion in Spain. A Diverse and Dispersed Space in Intense Transformation]; Cáritas: Madrid, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Navarra. Plan de Lucha Contra la Exclusión Social en Navarra, 1998–2005. In Una Respuesta a las Situaciones de Pobreza y Marginación Social (Vol. I, II y III) [Social Exclusion Plan of Navarre, 1998–2005. A Response to Situations of Poverty and Social Marginalization]; Gobierno de Navarra: Pamplona, Spain, 2000; Available online: https://www.observatoriorealidadsocial.es/es/estudios/plan-de-lucha-contra-la-exclusion-social-en-navarra-1998-2005-una-respuesta-a-las-situaciones-de-pobreza-y-marginacion-social-vol-i-ii-y-iii/es-86734/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Navarra. Plan Estratégico de Inclusión Social de Navarra [Strategic Plan for Social Inclusion of Navarre]; Departamento de Derechos Sociales: Pamplona, Spain, 2018; Available online: https://gobiernoabierto.navarra.es/sites/default/files/plan_estrategico_de_inclusion_social_navarra_2018-2021.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Navarra. Ley Foral 6/2006 de contratos públicos de Navarra [Regional Law 6/2006 on Public Contracts of Navarre]. 2006. Available online: http://www.lexnavarra.navarra.es/detalle.asp?r=4990 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Rreuse. Social Clauses: Why so Important and How to Implement Them. 2015. Available online: https://www.rreuse.org/wp-content/uploads/Social-clauses-in-PP-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2021).

- Navarra. Decreto Foral 340/2019, De 27 de Diciembre, por el que se Modifica el Decreto Foral 94/2016, De 26 de Octubre, Por el que se Regula el Régimen de Calificación, Registro y Ayudas de las Empresas de Inserción Sociolaboral de Navarra [Regional Decree 340/2019, which Regulates the Qualification, Registration and Aid Regime of the Social and Labor Insertion Companies of Navarre]. 2019. Available online: https://bon.vlex.es/vid/decreto-foral-340-2019-839025821 (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- Navarra. Ley Foral 2/2018 de Contratos Públicos [Regional LAW 2/2018 on Public Contracts]. 2018. Available online: https://www.navarra.es/NR/rdonlyres/6253BAA2-031B-45D6-AF41-710B8B321839/418876/LeyForal.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Flores, R. The intergenerational transmission of poverty: Factors, processes and proposals for intervention. In La Transmisión Intergeneracional de la Pobreza: Factores, Procesos y Propuestas Para la Intervención; Fundación Foessa: Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: http://www.caritas.es/imagesrepository/CapitulosPublicaciones/5250/transmisi%C3%B3n%20intergeneracional%20pobreza.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Getting Started with the SDGS. A Guide for Universities, Higher Education Institutions, and the Academic Sector. 2017. Available online: http://ap-unsdsn.org/wp-content/uploads/University-SDG-Guide_web.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2021).

- Martínez Virto, L. Itinerarios de Exclusión: Crisis Concatenadas, Acumuladas y Sin Apoyos [Itineraries of Exclusion: Concatenated, Accumulated and Unsupported Crises]. In La Desigualdad y la Exclusión que se nos Queda; Laparra, M., Ed.; Ediciones Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2015; ISBN 978-84-7290-708-9. [Google Scholar]

- UPNA Strategic Plan (2019–2023). Strategic Plan of Public University of Navarra (2019–2023). Available online: https://www2.unavarra.es/gesadj/seccionActualidad/plan-estrategico/Plan_Estregico_2020_CASTELLANO.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Leal Filho, W.; Bardi, U. (Eds.) Sustainability on University Campuses: Learning, Skills Building and Best Practices. Springer Nature AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Eransus, B.; Martinez-Virto, L. Políticas de Inclusión en España: Viejos Debates, Nuevos Derechos [Inclusion Policies in Spain: Old Debates, New Rights]; CIS: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).