Abstract

The general objective of this paper was to determine how companies in the olive sector could convert the comparative advantages of olive-growing regions (e.g., culture, tradition, raw materials, knowledge, infrastructure, networks, technological centers, etc.) into competitive advantages, to internationalize, in an accelerated way, and become born global firms, contributing to economic, social, and sustainable development of regions. Thus, we analyzed four cases of exporting companies in this sector (two born global and two non-born global) in southern Spain (Jaén). We chose this province because it is the world’s leading producer of olive oil and, yet it is only the fourth largest exporter compared to the rest of Spain. For the case study, we conducted (and recorded) personal, semi-structured interviews with the founders/managers or individuals in charge of internationalization. To obtain our results, we used a data sheet that included an action protocol, we analyzed each case individually, and we employed sensemaking and pattern-matching techniques to add validity and reliability to the research. Finally, we proposed the “keys” for these companies to go international in an accelerated way, as it would increase their competitiveness, foster the creation of employment, develop networks between companies, boost investment in innovation, etc. The results indicate that it is necessary to follow market orientation, networking, and international entrepreneurship strategies, and that intellectual capital (human, organizational, relational, and technological) of companies (and, therefore, of regions) will be the means through which competitive capabilities are achieved.

1. Introduction

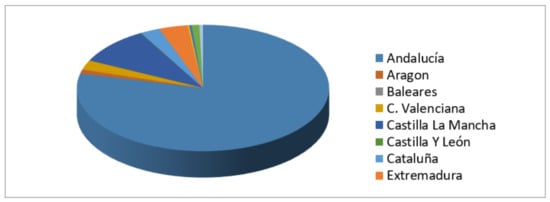

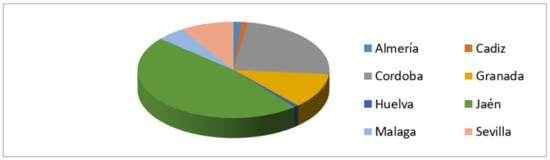

Spain produced 40% of the world’s olive in 2020/2021, followed by Italy (35%). Andalusia, in southern Spain, has the highest production of olive oil in the world (see Figure 1); within it, the province of Jaén is dominant (see Figure 2). According to the Food Information and Control Agency (AICA) of Spain, this province produced 387,391 metric tons of olive oil in the above-mentioned years, representing 44.9% of Andalusia’s total [1]. However, although the province is the global leader in olive oil production, Jaén does not export the most, it is placed after Sevilla, Córdoba y Malaga. The companies under study are all located in this province.

Figure 1.

Olive oil production in the 2020/2021 campaign in Spain by autonomous communities. Adapted from the Food Information and Control Agency (AICA). Issue date of the data: 25 June 2021.

Figure 2.

Olive oil production in the 2020/2021 campaign in Andalusia, by province. Adapted from the Food Information and Control Agency (AICA). Issue date of the data: 25 June 2021.

Jaén, located in Andalusia, southern Spain (see Figure 3), has one of the lowest per capita incomes in the country. In fact, the region does not exceed 75% of the per capita income of the autonomous community of Andalusia [2]. One reason is due to the low level of industrialization and the high specialization of the olive sector. Under these circumstances, it is essential to undertake measures to help develop this region. Export expansion would help increase the GDP and, therefore, the per capita income.

Figure 3.

The location of Jaén, a province in Spain. Source: Instituto Geográfico Nacional, accessed on 19 August 2021 (https://www.ign.es/espmap/spain_bach.htm).

Olive groves endow the region with comparative advantages, such as resources (e.g., culture, raw material, knowledge in the sector, tradition, infrastructure, confidence in the harvesters), and societal skillsets (e.g., skills, talent and strengths in cultivation, harvesting and production of the oil, etc.). Moreover, the economic, social, and institutional actors that form the region [3] could play important roles in developing these comparative advantages. These “actors” include the Olive Association, the Foundation for the Development and Promotion of Olives and Olive Oil of Jaén, the Technological Center of Olives and Olive Oil (CITOLIVA), the Technological Park of Olive Oil (GEOLIT), as well as ancillary companies that provide services related to engineering, digital development, machinery, etc.

Companies in this sector can turn the above-mentioned regional comparative advantages into competitive advantages (e.g., in regard to exporting to other countries), contributing to the economic development of the sector. Exporting companies could boost their sales, avoid national competition, discover more mature markets for certain olive oil segments, reduce manufacturing costs, learn new working methods from abroad, improve their positions in the market, organize production more flexibly, etc.

The general objective of this paper was to determine how companies in the olive sector could convert the comparative advantages of olive-growing regions (e.g., culture, tradition, raw materials, knowledge, infrastructure, networks, technological centers, etc.) into competitive advantages, to internationalize, in an accelerated way, and become born global firms, contributing to the economic, social, and sustainable development of regions. Specifically, the goal was to discover how companies in the extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) sector could become internationalized. There are two types of exporting companies; they are distinguished by how quickly they begin the internationalization process. (1) Some companies begin this process from the company creation, or during the first three years, at the most; this is called “born global”. By definition, these companies must also generate at least 10% of total sales in foreign countries [4]. (2) Other companies do so later (from here onwards, known as “non-born global”). The more born global companies there are, the earlier the exports will begin and, therefore, the greater the volume of exports there will be over time. For this reason, we focused on these two types of companies, with special emphasis on born global firms.

There are some studies, such as that by Bouhaddne and Mili [5], which analyzed the key factors and future strategies for the internationalization of Spanish olive oil, from the value chain perspective. Moral and Lanzas [6] highlighted the low export activity of olive oil companies, while Rodríguez-Cohard et al. [7] looked at how to adapt the olive oil production model in a new market situation, with capital, knowledge, and tradition as endogenous factors. Bernal-Jurado et al. [8] addressed the scarcity problem and the nature of sales outlets in the organic olive oil sector. Moral-Pajares et al. [9] highlighted the participation of the Andalusian olive sector in international markets, in order to understand the magnitude and characteristics of its recent evolution. They also attempted to identify the main company strategies (concerning their internationalization processes), with the goal of identifying the most efficient ones. Sánchez-Famoso et al. [10] identified the mediating roles of cooperation agreements in the relationship between family participation in business internationalization and the level of international engagement. However, no studies shed light on how companies in this sector could be born global firms, based on the comparative advantages of the region. This would be of great interest to researchers, entrepreneurs, and public institutions.

The theoretical contribution of this work was to adapt and apply a framework, which we had previously proposed to other internationalized companies, to companies in the olive sector. In this way, we applied a previous model of internationalization to companies in the olive sector, which led us to believe that following strategies of market orientation, networking, and international entrepreneurship involve human, organizational, relational, and technological capital to achieve competitive advantages, so that companies in the olive sector can be international. Thus, in this study, we identify the key ways in which these companies could achieve competitive advantages in exporting and become born global firms, based on resources (olive groves, mills, presses, tradition, knowledge of the sector, etc.), capabilities (skills, talents, and strengths in cultivation, harvesting, production and processing), and economic, social, and institutional actors (organizations, associations, auxiliary companies, etc.). In addition, we aimed to link the business perspective with the regional scope. We begin with the endogenous development approach, based on dynamic capabilities, and we gathered theoretical foundations of the models of accelerated and gradual internationalization. Subsequently, we include strategies, to be followed by these companies, to achieve competitive advantages and, thus, become internationalized. We focus on advising companies on what they should do to become exporters and, specifically, born global firms.

The methodology is the case study. We conducted (and recorded) personal, semi-structured interviews at the company premises, with the founders/managers or those in charge of internationalization, and we included an action protocol based on a data sheet. We should emphasize that the methodological contribution focuses on the in-depth study of individual and comparative cases, via sensemaking and pattern-matching techniques, in which chronology, events, and causes are tracked, and the agreement between theory and real cases is contrasted. This adds validity and reliability to the research. Our analyses focus on four companies in the olive oil sector (two born global and two that gradually internationalized), located in southern Spain (Jaén), due to the importance of this type of production for this region, since it is the world’s leading olive producer.

2. Theoretical Framework

Our theoretical framework is based on the endogenous development approach, which considers that economic growth and structural change are not functional issues, but are part of a regional phenomenon [11,12]. Furthermore, such developments are motivated by the accumulation of capital, which is the result of the interaction of the forces of development: the diffusion of innovation and knowledge; the creation of networks through transport and communication infrastructures; the flexible organization of production; and the evolution of institutions and social capital [13]. By combining all of these forces, a greater impact on individual factors is achieved, and this synergy influences the economic return, productivity, and competitiveness of firms, the accumulation of capital, and economic and social progress.

Economic and productive factors condition the processes of capital accumulation, but not in isolation; it is the interaction between them that drives the increase in productivity and growth. In other words, the development of the territory depends on the effects produced by the coordination between the forces of development. Therefore, growth processes become dynamic when the forces that activate the development processes act together, creating synergy between them, and reinforcing their effects on the returns to capital and labor, so that the development factors act in a network and increase the effect of each development process [14].

Concerning the regional development approach—there are two factors that influence the above results: (a) the development potential existing in the region based on available resources and human resource capacities, and (b) the organizational capacities of economic, social, and institutional actors to achieve coordinated actions [15]. These capacities are derived from the skills, talents, and strengths available to a region, to take advantage of its resources and potential; these are shaped by structural, institutional, and relational considerations present in the area [16].

Under the previous premises—Rodríguez-Cohard et al. [17] carried out a comparative analysis on four European olive-growing regions that employed different strategies to adapt to the changes brought about by globalization. This study shows how each territory determines its growth potential. Therefore, the region not only provides support for productive activities, but also includes a combination of resources (human, natural, and business) and capabilities that define its potential development, and act as a base where local companies can respond to the competitive challenges that exist in the markets [18]. The territory is also composed of economic, social, and institutional actors that shape the environment where productive activity takes place [3]. Consequently, the region becomes a strategic driver of development [19].

Based on the above reflections, we understand that the region has comparative advantages that companies can convert into competitive ones and, in this way, can contribute to the development of the region. Entrepreneurship plays an essential role in this. The region under study possesses advantages derived from resources, including raw material (olive groves), infrastructure (olive presses, oil mills, rural houses, etc.), access roads to farms, olive grove culture, tradition, knowledge of the sector, and transmission from parents to children, among others. There are also capacities (skills, talents, and strengths) acquired by the “agents”, with respect to cultivation, harvesting, production, and processing of extra virgin olive oils (EVOOs), and economic, social, and institutional actors, such as institutions, local governments, associations, organizations, auxiliary companies, foundations, competing companies, technology centers, among others (for example, the Provincial Council of Jaén, the Olive and Olive Oil Association of Jaén Province, the Foundation for the Development and Promotion of Olives and Olive Oil in Jaén, CITOLIVA, municipalities, auxiliary companies, etc.), which can support olive oil companies in their internationalization processes, bringing, for example, the global environment closer to local environments, which contributes to regional development.

All of the above leads us to consider how companies in this sector could convert the above-mentioned comparative advantages into competitive ones, in order to become successful internationally and, in this way, further the development of the region through economic progress, the well-being of the population, and environmental sustainability. According to Mozas-Moral et al. [20], endogenous development could emerge in a diffuse way in the territories if endogenous resources are used. To achieve this, the company´s must follow as set of strategies and update their initial capacities, which are derived from the territory. To achieve this, they must follow a set of strategies and update their initial capacities [21,22], which are derived from the region. In this way, companies will achieve superior or dynamic capacities and, thus, obtain greater performances, which means that they could become international in the shortest possible time (gradually or accelerated). All of this makes the region more dynamic through job creation, the accumulation of knowledge, new forms of organization, the creation of new networks, innovation, etc.

We therefore constructed our conceptual framework using the endogenous development approach and the dynamic capabilities approach. The latter considers as “dynamic” those higher-order capabilities that enable firms to implement new strategies by modifying, combining, and transforming available resources in new and different ways [23]. Mudalige et al. [24] studied the applicability of dynamic capabilities at the individual and firm level in the internationalization process of SMEs; they found that owner-specific dynamic capabilities had a positive influence on both firm-specific dynamic capabilities and internationalization. Moreover, the dynamic capabilities of the firm have mediating effects between owner-specific capabilities and internationalization. This paper confirms the relevance of the dynamic capabilities theory for internationalization.

To these approaches, we include the theories of internationalization, in regard to the timing of this process. There are two types: the gradual model and the accelerated model. The former focuses on a process of internationalization based on stages. Thus, initially, businesses expand into countries that are physically and culturally closer, and then to countries that are further away, which involves greater investment. In this way, uncertainty is reduced at each stage [25]. Consequently, confidence is increased by having greater experience in the international market, more knowledge is generated, and greater commitment is acquired. Finally, as a result of the process, dynamic capabilities are developed. The second model (accelerated) focuses on born global companies, which are those that meet the following characteristics: they must internationalize, on average, within three years of their founding [26] and generate at least 10% of total sales in foreign countries [4]. In addition, according to Etemad [27] (pp. 3–4), they are: (a) more aware of international opportunities; (b) more innovative; (c) more proactive; (d) more sensitive to the dynamics of change and to the differences and patterns of their competitive evolution; (e) more open to joining or establishing collaborative, expansive, and open networks; (f) dependent on the multilevel capabilities of their own partners compared to the resources related to their environments; (g) able to learn from other companies; and (h) very agile and resilient, due to their managerial dynamism and competitive flexibility.

Considering the above theories, companies in the olive sector can employ strategies to improve the comparative advantages of the region and, thus, become more competitive [28]. To do so, they should follow strategic orientations and actions that will allow them to develop competitive advantages and become international in an accelerated or gradual way, which will improve their position in the foreign market and foster the economic development of the region. However, none of these theories predicts the strategies that these companies should follow to achieve this goal.

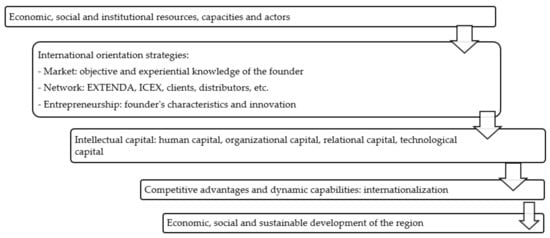

There is no specific theoretical framework for companies in this sector that predicts the keys to internationalization. Therefore, in this study, we apply a theoretical framework to companies in the olive sector, one in which the authors previously developed for internationalized companies in another sector. Thus, in order to convert the comparative advantages of the region into competitive ones, companies should follow a set of strategies oriented towards the market, the network, and international entrepreneurship. In this regard, these competitive capacities will be attained by intellectual capital (human, organizational, relational, and technological) of the company and, therefore, of the region (Figure 4). Ultimately, these elements are what make it possible for companies to be international.

Figure 4.

Achieving competitive advantages in the olive oil sector. Source: adapted from Martos-Martínez and Muñoz-Guarasa [29].

2.1. International Market Orientation Strategies

Market orientation leads to the development of specific knowledge, which forms part of a firm’s expertise and enables it to adapt quickly to changes in the environment. Through these strategies, objective knowledge of the foreign market is acquired (collection and transmission of information, for example, through market research, attendance at international trade fairs, contacts with future customers, etc.) and the experiential knowledge of the founder and/or export manager obtained from having participated in previous internationalization processes (e.g., knowledge of customers, markets, competitors, institutions, etc.) is exploited, which involves the transfer of knowledge between companies [30] (p. 340) and could affect the way they perceive and assess foreign market opportunities [31]. It also allows the company to adapt the product to the needs, tastes, and demands of potential customers.

2.2. International Network Orientation Strategies

These strategies assist companies in identifying international business opportunities, since networks encompass the relationships of an individual or a company (for example, with distributors, customers, organizations, etc.), providing a means of access to new and different types of information and ideas that would not otherwise be available [32]. Some studies, such as those by Contractor et al. [33], point to a strong network of contacts developed by entrepreneurs as a result of their previous experience, which has enabled them to internationalize more quickly than others. Thus, one key difference between companies that are born global and those that have internationalized gradually can be found in the creation of relational trust through pre-existing connections, which are accessed through established network partners. All of this reduces risk and enhances organizational learning [34]. Among the parties that make up the network in the olive sector of Andalusia we include customers, distributors, importers, chefs, organizations, ancillary businesses, competitors, suppliers, Provincial Councils, Foreign Promotion Agency of Andalusia (EXTENDA), Foreign Trade Institute (ICEX), etc.

2.3. International Entrepreneurship Orientation Strategies

Gabrielsson et al. [35] suggests that the propensity for innovation, the attitude to risk, and the level of proactivity all affect progress in the early stages of company growth. Thus, the founder should possess the following characteristics: (1) autonomy: having the independence and freedom to give birth to an idea or vision and carry it through to completion; (2) innovativeness: the founder should be inclined to implement and support new ideas, novelty, experimentation and creative processes that can lead to new products, services or technological processes, which can facilitate the process of internationalization; (3) proactivity: having a forward-looking perspective that accompanies an innovative activity and allows the entrepreneur to conceptualize new goals and the methods to attain them ahead of others; (4) proclivity: the founder should be driven to enter foreign markets, a trait that is associated with his/her values; (5) competitive aggressiveness: having the propensity to enter the international market by challenging competitors, to improve the company’s position in the market or to outperform existing rivals. Likewise, introducing innovation in the different phases of the production and marketing process, which in the olive sector are cultivation, harvesting, production, packaging, and national and international marketing, improves the adaptation of the product to the needs of the client and increases productivity and competitiveness.

2.4. Human Capital

The knowledge acquired, concerning tastes, needs, legislative requirements, etc., reduces uncertainty, and helps human capital, i.e., to develop values, aptitudes, attitudes, and capacities [36] that are favorable to the internationalization process, helping to accelerate it. The body of knowledge is integrated in what individuals and groups know, in their capacity to learn, and to share their knowledge with others, which facilitates its accumulation, benefiting both the organization and the region and improving their adaptability to the international market.

2.5. Organizational Capital

Organizational capital is composed of organizational learning (serving the market and challenging its own assumptions about its mission, customers, competitors, and strategies) [37] and of organizational culture, consisting of the structure of cultural capital, learning, and organizational processes [38]. All of this leads to the development of organizational culture by the workforce, which can be put into practice in other companies in the region.

2.6. Relational Capital

Relational capital refers to using previously established relationships, for example with EXTENDA, ICEX, chefs, importers, distributors, clients, competitors, etc., to create new and long-lasting ones. It is broken down into so-called “relational culture”, which reflects the company’s relationships with the main agents linked to it [39], which has positive effects for the economic, social, and political agents that make up the region.

2.7. Technological Capital

Technological capital is composed of technical and managerial technological skills, which involve the way ICTs are conceived, deployed, and exploited to support and improve the organization and coordinate activities [40]. It also includes the innovative or entrepreneurial culture that indicates the degree to which companies in the sector are proactive in exploiting new opportunities [41] and is essential for the development of innovative efforts capable of exceeding customer expectations, enabling the attainment of competitive advantages [42].

3. Methodology and Methods

The article justifies that the methodology is related to the suggested model, since the case analysis is appropriate to know “how” these companies can achieve competitive capabilities, and “why” some internationalize gradually and others in an accelerated manner. In other words, case analysis is appropriate because we need to know “how” a company can become international based on its own actions. Moreover, the case study as a methodology applied to scientific research related to the company’s strategic decisions is becoming increasingly accepted, especially as it has been proven that access to first-hand information is essential, since internationalization processes require a type of analysis that cannot be carried out in sufficient depth through studies with a large number of observations [43]. Likewise, its value resides, in part, in the fact that it is not only possible to study a phenomenon, but also its context [44,45]. In this way, researchers will be able to explore the differences between the cases and study the internationalized olive sector companies within the real environment and with fewer limitations than in a survey. The objective of this study is to replicate the theoretical model gathered in this research, which is composed of the following elements: international market, network, entrepreneurship strategies and human, organizational, relational, and technological capital [46], and to empirically test the causes and the process of internationalization of these companies as a whole, and not in partial units, which adds a holistic dimension.

Therefore, the study method used was the comparative method, which, according to Aguilera-Hintelholher [47], allows us to study the similarities and differences between business structures and allows us to delve into the analysis of the actors, contexts, processes, times, and developments that are organized as systems of institutions and modes of operation. It also allows us to study the factors, processes, and times that make their development possible in a diverse and contrasted way. In this way, the comparative method allowed us to know the similarities and differences between the cases, as well as the development of the internationalization process, times, key factors, etc. We also used the inductive method, which proposes an ascending reasoning that flows from the particular or individual to the general, thus becoming a reflection focused on the end. In this way, it can be observed that induction is a logical and methodological result of the application of the comparative method [48]. Therefore, by means of this inductive method, we achieved a logical result that has taken the form of a set of propositions.

The unit of analysis focused on exporting companies in the olive oil sector in Jaén (southern Spain), due to the importance of this province as a producer of olive oil, which was highlighted in the introduction. Thus, the importance of investigating how this region could be more competitive is evident. For the selection of companies, we used the information provided by EXTENDA on exporting companies in the province. To carry out the selection, we proceeded to differentiate the following phases:

- -

- First, we chose the leaders in the province and, among them, those that could be born global, and those that could not. Subsequently, we included those that had internationalized within three years of their creation (born global) and those that had needed more time to initiate this process (non-born global). The next criterion was that at least 10% of revenues should be generated abroad.

- -

- Second, we selected those companies that produce extra virgin olive oils (EVOOs), especially premium oil. This is the highest quality of extra virgin olive oil, since it must meet a set of requirements, such as having the earliest harvest time, which is when the oil is at its optimum ripening period, the oil extraction is carried out cold, it maintains the organoleptic characteristics, etc., and it provides great health benefits, for example, the prevention of cancer. Finally, we required that more than 95% of the company productions were packaged (a very small proportion was sold in bulk).

- -

- Third, we selected the appropriate number of cases. For this, we followed Yan and Gray [49], who state that two will suffice. However, we chose four exporting companies in the olive sector (two born global and two non-born global).

Finally, the companies selected were Aires de Jaén S.L., Castillo de Canena Olive Juice S.L., Galgón 99 S.L.U and El Trujal de la Loma S.L. Below is an original image (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8) that each company has provided us with.

Figure 5.

Aires de Jaén.

Figure 6.

Castillo de Canena.

Figure 7.

Oro Bailén.

Figure 8.

El Trujal de la Loma.

The starting point was to prepare a data sheet (see Table 1), which allowed us to establish a protocol for the analysis of the cases. It is interesting to note that we began this study with a first pilot case, Aires de Jaén, which allowed us to better understand the literature and its relationship with the business reality.

Table 1.

Data sheet for the case analyses of internationalized companies in the olive oil sector.

The following Table 2 shows the main characteristics of the companies under study.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studied companies.

In the data collection phase, we applied the concept of data triangulation (documentary evidence, interviews, direct observation, recording interviews), which have been obtained through different sources:

- -

- Primary: personal, semi-structured, and open interviews, which were recorded and conducted personally by the researchers of this study. In carrying out the interviews, we followed a questionnaire that is divided into two parts:

- (a)

- The first was aimed at obtaining information on the use of resources, capacities and the social, economic, and institutional actors from the region derived from the olive grove, to create a combined overview of the company and the internationalization process, which was composed of the following items:

- ▪

- General characteristics of the company (year of creation and internationalization, organization chart, activities, products and brands, size, revenues abroad, company history, etc.).

- ▪

- Internationalization: motives, exports, strategies, entry modes.

- ▪

- Use of resources, capacities, as well as economic, social, and institutional actors of the territory that facilitated the internationalization process.

- ▪

- Quality (certificates, awards, and international recognition), olive growing, and sustainable cultivation.

- ▪

- Competitive advantages for exporting.

- ▪

- Benefits for local development provided by the company: increase in employment, investment, income, innovation, personnel training, creation of new companies, involvement of public and private institutions, etc.

- (b)

- The second part consisted of short questions in which the interviewee was asked to choose specific and previously established answers. This part provided us with information for later coding, translating, and obtaining the results, thereby allowing us to apply the theoretical framework (strategies and intellectual capital) to the cases studied.

- -

- Secondary: documentary evidence through reports, internal reports, web pages, presentations, publications, and databases.

4. Results

Once the information was obtained, the methods for analyzing the data were as follows: the first step was to perform an individual analysis of the cases. In Table 3, the use of resources, capacities, and economic, social, and institutional actors of the region by each company.

Table 3.

Resources, capacities, and economic, social, and institutional actors of the region: individual analysis of cases.

On the other hand, In Table 4, based on knowing the characteristics, history, internationalization process, and future prospects of each company, we are able to understand how they followed strategies oriented toward the international market, networks, and entrepreneurship, as well as the competitive capabilities that were achieved, in terms of human, organizational, relational, and technological capital.

Table 4.

Internationalization strategies: individual analysis of cases.

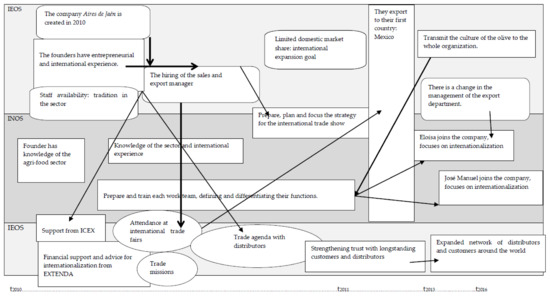

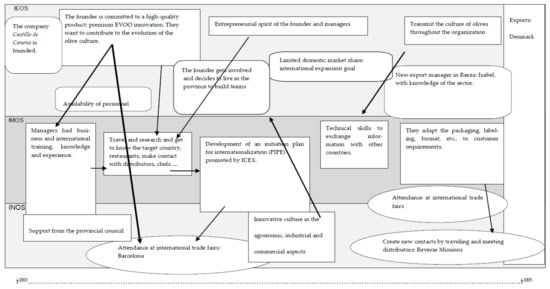

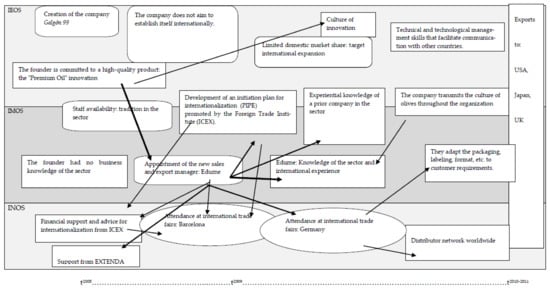

The next step involved obtaining explicit information that was suitable for tracing chronologies of events, meanings, and discussions [50]. For this, we used the following analytical techniques:

- -

- Firstly, we used sensemaking, based on process theory, which is undertaken following Weick’s theoretical framework [51]. Specifically, these visual mapping strategies allow us to identify the sequence that firms have followed in the strategies oriented towards the market, the network and entrepreneurship international, as well as whether the same strategies have enabled the firm’s intellectual capital to achieve competitive capabilities favorable to the internationalization process. In the same way, the sensemaking techniques allowed us to determine whether the companies had followed the strategies included in the model during the three years following their foundation or afterwards. Therefore, these techniques help us to reveal the origin, processes, causality, interactions, and duration of the company’s internationalization.

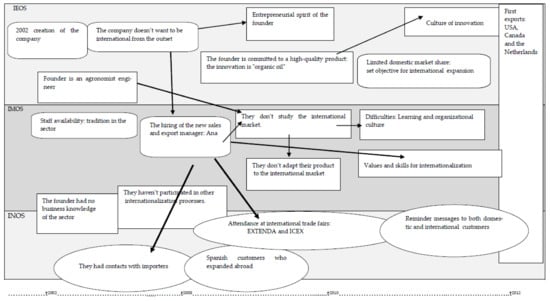

Following Langley [52] and Monin et al. [53], the design of the visual maps is as follows: (1) the location of the box in one of the three horizontal shadow bands shows the domain of the strategic orientation associated with the event. (2) The arrows in each box indicate the influence that one event or decision has on another. Consequently, they are not all linked since actions included in one strategy may not have a direct effect on other actions in other strategies. (3) The thickness denotes the impact of the influence (thin line = medium–low impact/thick line = medium–high impact). (4) The shape of the boxes signifies whether the event is a decision (rounded corner), an activity (corner) or an event involving external agents (oval) and adapted in each of the analyzed cases included in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, below.

Figure 9.

Visual Map Aires de Jaén, sensemaking strategies.

Figure 10.

Visual Map Castillo de Canena: sensemaking strategies.

Figure 11.

Visual Map Galgón 99: sensemaking strategies.

Figure 12.

Visual Map El Trujal de la Loma: sensemaking strategies.

In a comparative way, the following can be extracted from the sensemaking techniques: in regard to companies that are born global during the first three years after their creation, it is the founders and/or managers who have a direct influence in getting to know the international market, and in creating international networks, as well as those who are committed to transmitting the EVOO culture, for example, through reverse missions with distributors and importers. Companies that internationalize after the first three years from their creation follow a more gradual process, in which the person hired, years after their creation, responsible for the internationalization process (Edurne in Oro Bailén and Ana Carcherriel in El Trujal de la Loma) has a direct influence on the pace of international expansion, as well as on the strategies of market orientation, networking, and international entrepreneurship. Furthermore, in all the companies, it is the founders (born global) and/or those responsible for internationalization (non-born global) who are actively involved in the creation of international networks, to operate in the foreign market.

- -

- Secondly, we applied pattern-matching technique based on comparing the patterns of agreement between the theoretical framework and the observed or operational one. This is a basic procedure for testing theories through case studies. Specifically, we checked whether the theoretical perspective coincides with the reality of the cases, which will help to know whether market studies, the experience, and character of the founder, innovation, networking through participation in international fairs, etc., have led these companies to achieve adequate dynamic and competitive capabilities (Table 5). Our study is supported by that of Vaillant et al. [54].

Table 5. Pattern-Matching Analysis.

Table 5. Pattern-Matching Analysis.

Finally, we emphasize that, in order to obtain the highest degree of rigor and quality of research, we are guided by Yin [55]. Thus, external validity was achieved by using rival internationalization theories (gradual and accelerated). In addition, we applied a specific theoretical framework that includes the keys for these companies to achieve competitive advantages and, in this way, become international as soon as possible. This framework benefits both companies and the region, for example, exporting companies can boost their sales, find more mature markets for certain olive oil segments, increase regional GDP and investment, increase employment, etc. The framework could also provide incentives that affect regional development (e.g., the use of more innovative and environmentally friendly production techniques), increase investments, promote the training of personnel in the harvesting and production of quality EVOO, increase employment, collaborate with technological centers, learn new working methods from abroad, increase international networks, evolve in the olive culture, etc. The above benefits are supported by the literature, in that internationalization is an opportunity for companies to expand into different markets, creating jobs and economic value for the region [56].

Internal validity was ensured by conducting personal interviews with those responsible for the internationalization processes of their companies, which were complemented with information provided by their corporate reports, and via sensemaking and pattern-matching tools. Reliability was obtained through the completion of the data sheet, the interviews, which were conducted (and recorded) personally by the researchers, as well as the coding of the data of the cases studied.

The main results are included in two blocks: (1) olive oil companies that were born global and, (2) non-born global companies. These are as follows:

Born global companies: Aires de Jaén and Castillo de Canena converted the comparative advantages (family tradition, knowledge in the sector, culture for olive oil transmitted from parents to children, personnel with skills, and qualities favorable to the harvesting, extraction, and processing of olive oil, the support of EXTENDA, ICEX, and Provincial Council of Jaén, etc.) of the territory into competitive ones. This allowed them to internationalize in an accelerated manner within three years of their incorporation. To this end, these companies have implemented the following strategies.

- (A).

- International market orientation: the managers, from the beginning, knew the sector, and had previous national and international business experience, and high training and knowledge in the sector. They studied the market to which they could direct their products, adapted the product to the needs of the international consumers, understood the certificates of greater recognition needed in each country, as well as the packaging, the labeling, the flavor, and color of the oil required. In addition, from the beginning, they studied and prepared, conscientiously, their attendance to international, recognized, prestigious fairs, to make their product known.

- (B).

- Orientation to the international network: from the beginning, they had a relationship with EXTENDA, ICEX, and the Provincial Council of Jaén. They attend international fairs, and contact chefs, importers, distributors, etc.

- (C).

- International entrepreneurship orientation: since its inception, the founders wanted their company to be international. They used innovative practices, from cultivation to marketing, while respecting the environment. From the beginning, they conducted biodynamic agriculture, protecting and respecting the environment. In this way, they obtain innovative products.

Intellectual capital also has competitive advantages:

- (A).

- Since the birth of the company, human capital has been the key piece in the whole process. Work teams, composed of professionals with high academic and language training, and previous experiences in their positions, were created. Likewise, before exporting, the personnel developed skills, attitudes, and abilities that favored their adaptations to the demands of the international market.

- (B).

- Relational capital: they created new relationships from those previously obtained and maintained them over time. They used their attendance at trade fairs to obtain feedback from customers, distributors, chefs, journalists, etc. Likewise, they made great commitments to oleotourism, to make the product known, transmit the olive grove culture from the field, etc., strengthening the relationship with the international client.

- (C).

- Organizational capital: the organization is integrated in the whole process, from the olive grove to the commercialization of oil.

- (D).

- Technological capital facilitates the management and application of technologies in the different parts of the EVOO production and marketing process.

Finally, one of the main differences between Aires de Jaén and Castillo de Canena involves Castillo de Canena’s commitment to biodiversity and biodynamic agriculture. Since its beginnings, the company obtained corresponding certifications that endorsed it (e.g., in regard to corporate social responsibility). Likewise, both companies have different product strategies, since Aires de Jaén produces EVOO, virgin olive oil, and olive oil, among others, while Castillo de Canena only produces extra virgin olive oil in its different varieties.

No-born global companies: Galgón99 and El Trujal de la Loma have comparative advantages, derived from the territory (family tradition, knowledge in the sector, olive oil culture transmitted from parents to children, personnel with skills and qualities favorable to the harvesting, extraction and processing of olive oil, as well as support from EXTENDA, ICEX, and Provincial Council of Jaén, etc.), but they did not follow market orientation strategies, or network and international entrepreneurship during the first three years since their creation (only after). Among the main reasons—the founders had no experience in participating in other internationalization processes and had no previous business knowledge of the sector. In addition, they did not intend to go international from the beginning, which implies that the periods to become international were different (6 years from its creation in the case of Galgón99 and 10 years for El Trujal de la Loma).

Innovation is just one of the aspects in which they focused on; they applied it in cultivation, harvesting, production, and marketing. In this way, they developed an innovative culture after three years from creation. Both opted to produce superior quality EVOO (Galgon99, premium, from its beginnings, and El Trujal de la Loma—organic oil, years after its creation).

In the internationalization process, there are differences among the companies, with respect to:

- -

- Preparation of international fairs (study, participation, elaboration, exhibition, product, etc.).

- -

- Adaptation of the packaging, labeling, etc., of the oil to the international client.

- -

- Attracting international customers.

- -

- Study of the international market.

- -

- Adaptation of the product to the tastes, needs, requirements, etc., of each international market.

- -

- Training and international experience of the person in charge of internationalization.

- -

- Creation of new networks of contacts according to those obtained previously.

- -

- Development of technical and technological management skills.

Finally, it should be noted that Galgón99 experienced a faster internationalization process when compared to El Trujal de la Loma, since, once the first exports began, its international expansion was faster. Thus, El Trujal de la Loma is still immersed in a gradual expansion, while Galgón99 has accelerated. The factors that may motivate the different paces of internationalization may be related to the differences described above (market knowledge, human resources training, international experience, international network, etc.).

In conclusion, after the case studies and the results obtained, we make the following propositions: in order for companies in the olive sector to convert their comparative territorial advantages into competitive advantages and become international (after three years from creation), they must follow the following strategies. Moreover, in order to do so in an accelerated manner; that is, to become born global firms, companies must carry these strategies out within the first three years from creation.

Proposition 1: the founder/manager or person in charge of internationalization must have objective knowledge about the market and the country where the internationalization process is to be initiated.

Proposition 2: the founder/manager or person in charge of internationalization should possess experiential knowledge, having participated in internationalization processes at previous companies.

Proposition 3: the company should establish an international network (foreign trade agencies, attendance at trade fairs, congresses, or participation in research, trade missions, customers, business services, suppliers, competitors, peers, related sectors, etc.).

Proposition 4: the founder should demonstrate autonomy, innovation, proactivity, proclivity, and competitive aggressiveness towards the international market. That is, they should have the independence and freedom to pursue an idea and see it through to the end (autonomy), support new ideas and creative processes that can lead to new products, processes, or services (innovation), have a forward-looking perspective towards the international market (proactivity), and be inclined to enter new markets (proclivity) in order, for example, to improve their positions (competitive aggressiveness).

Proposition 5: the company should offer innovative products, e.g., premium EVOOs.

The above propositions also enable the company and, therefore, the region, to obtain dynamic and competitive capabilities through intellectual capital (human, organizational, relational, and technological). The following propositions, concerning intellectual capital, are identified. Olive oil companies should:

Proposition 6: attain values, attitudes, aptitudes, and capabilities favorable to the internationalization process (human capital).

Proposition 7: follow an organizational learning process (organizational capital).

Proposition 8: have an organizational culture (organizational capital).

Proposition 9: use the international relationships previously created to obtain new relationships and maintain them over time (relational capital).

Proposition 10: use technological management techniques (technological capital).

Proposition 11: have a culture of innovation (technological capital).

5. Discussions

The study shows that born global EVOO exporting companies have converted the comparative advantages of their territories into competitive advantages, become international within the first three years from incorporation. However, among the non-born global companies, Galgón 99 developed these capabilities more than three years after its founding, and El Trujal de la Loma is still immersed in a gradual internationalization process, so it has not yet developed all competitive capabilities. Thus, the proposed strategies, followed by the above companies, to become international have been: (a) Orientation to the international market (objective knowledge of the market, for example, through market studies and knowledge of the founder/manager or those responsible for internationalization acquired, by having participated in previous internationalization processes). (b) Orientation to the international network (foreign trade agencies, importers, chefs, distributors, competitors, Provincial Council of Jaén, attendance at international fairs, etc.). (c) Orientation to international entrepreneurship (the founder must be inclined to enter new markets, be proactive in offering innovative products in international markets, support new ideas, and want to improve the company’s position in the market). Likewise, the company must offer innovative products, as is the case with EVOO.

The above-mentioned business strategies lead to intellectual capital (human, organizational, relational, and technological) of the company and, therefore, of the region, developing competitive capabilities. Human capital contains values, aptitudes, and capabilities that are favorable in an internationalization process; organizational capital will create an organizational culture and offer new forms of organization; relational capital will create new relationships from the initial ones; and technological capital will develop technical and technological management skills, as well as an innovative culture.

International market orientation strategies involve knowing the tastes, demands, and needs of foreign customers, who demand the production of quality oil (superior category EVOOs). This means: (a) not using fertilizers or aggressive practices for cultivation, production, or harvesting. (b) Using advanced and innovative mills, techniques, and practices that respect biodiversity, the environment, the habitat, and the ecosystem. (c) Working towards biodynamic agriculture, where agronomic activity can be combined with nature, which will favor the preservation of the ecosystem. (d) Participating in research projects, as well as offering innovative products in collaboration with technological centers and universities, which allows more environmentally sustainable oil to be produced. All of this has allowed the capabilities of people in the region to evolve, from what was traditionally done by previous generations to what the global world demands (quality oil, environmental sustainability, etc.). It is striking that some companies that are more removed from the olive-growing tradition of the area have introduced new values associated with quality, transforming production practices, in contrast to other companies with longer olive-growing traditions, which have enhanced the value of the region [57]. Therefore, it is reasonable to think that the tradition of olive growing also imposes historical barriers that intellectual capital must overcome, which will lead us to a transformation in the way of understanding and treating the olive grove, moving us towards the development of more sustainable farmlands.

In short, knowing the market to which the EVOO product will be directed, and having a founder/manager or export manager with international business experience will add value to the product, as it makes it easier to adapt to the demands of the international client, since the way in which this oil is used in our gastronomic culture does not coincide with that of the rest of the world. Thus, it will be easier to adapt both the intrinsic attributes (flavor, origin, nutritional qualities, olive variety, organic and premium character, etc.) and the extrinsic attributes (brand, price, packaging, point of sale, etc.) to the demands of the market and/or the target countries. This knowledge will also facilitate the attainment of international awards and recognition, which adds value to the product. In the same way, it will be necessary to use the relationships with the Provincial Council of Jaén, EXTENDA, and ICEX, depending on the needs of each market, through trade missions, international fairs, face-to-face meetings, show rooms, contacts with chefs, reverse trade missions with distributors, etc. In addition, it is especially important to transmit the culture and values of the olive grove to these intermediaries, so that, in turn, they can convey them to the end customer. In this way, these international networks should be used to forge links between the global and the local, as they can reduce uncertainty with respect to the international market and add knowledge to companies in the region that lack experience abroad.

The companies studied are committed to innovation and environmental sustainability, preserving and respecting the natural heritage of the olive grove. To this end, one business/institutional initiative is that of “oleotourism”, or olive oil tourism, since it increases local participation and involvement, allows people to learn about the crop, its history, geographic characteristics, etc. Additionally, it is related to the previous strategies (market orientation, networking and international entrepreneurship), as it enables the creation of networks, permitting the international customer to learn the origin of EVOOs, as well as the innovation used for their production. Therefore, offering solutions to companies in the olive sector. so that they can internationalize in an accelerated manner allows the olive culture to advance towards the development of a set of skills and attitudes that enable them to produce better quality oil, as well as to use more innovative techniques to produce differentiated EVOOs. It is also up to the technology centers to promote the dissemination of innovations among local stakeholders. However, the companies studied did not have any relationships with the province’s technology centers, except for Castillo de Canena, which had collaborated and participated in specific projects since its origins. Therefore, it would be wise to strengthen this collaboration and establish new contacts.

In regard to the economic, social, and institutional actors, it was observed that the companies demand greater support from associations, organizations, and institutions located in the region, so that the internationalization process could occur faster, and uncertainty due to the lack of knowledge of the foreign market could be reduced. This disconnects between companies in the olive sector and institutions, associations, technology centers, etc., could stifle the emergence of other new institutions, which act as an engine for the development of the region, since they encourage the diffusion of innovations. According to studies by Aznar et al. [58] and Rodríguez-Cohard and Muñoz-Guarasa [59], in the region in which the study area is located (Andalusia), most endogenous development tools are activated through local initiatives to change the local productive system, so that cooperating and strengthening ties between local agents and those acting (or located) in the international arena adds positive effects to the region and its companies. Sánchez-Martínez et al. [60] indicate that the strategic change initiatives carried out in the region must be in line with its institutional framework, since informal institutions are key in shaping a positive outcome from the changes implemented, so that they become processes of social innovation and endure over time, which contributes to improving the quality of life of the area’s citizens. Specifically, the municipalities did not support the analyzed companies at the beginning of their processes (of expanding abroad), so coordination and cooperation between them and the olive sector is essential, since it is a strategic piece in the promotion of collective learning within the regional innovation systems, through the interaction among universities and research centers, external and local companies, and the public administration [61]. Likewise, the absence of policies for the dissemination of this “new olive oil culture” (referring to EVOOs) also influences the lack of knowledge of the sector, with respect to “technical scientific” knowledge [57].

6. Conclusions

The internationalization of companies in the olive sector implies a greater connection among the resources, tradition, knowledge of the sector, and love for the olive grove, at the local level, with the demands and needs of the globalized world. There is a long road ahead in spreading olive culture around the world. First, innovation is key, to develop and introduce more advanced practices that respect the environment, conserve natural heritage, and produce higher quality oil with healthier properties. This appears to be the path along which the agronomy, production, and marketing efforts of EVOOs should be directed. Secondly, following strategies oriented toward the market, networking and international entrepreneurship makes it possible to have greater knowledge of the needs of international customers, since these oils need to be categorized, understood, and studied to bring them to the consumer’s table, and adapt them more easily to the needs and tastes of the international customer. Thirdly, the economic, social, and institutional actors contribute to the dissemination of innovations, learning, etc. Consequently, the role of these actors in the endogenous development of this region should be strengthened since the companies studied demand greater collaboration. All of this implies the creation of a virtuous circle, in which the companies in the sector need the resources, capacities, and economic, social, and institutional actors of the region to achieve competitive advantages and, in turn, these advantages are acquired by the intellectual capital that permeates the region, which contributes to its development.

These conclusions have implications from both a theoretical and a practical perspective.

From the theoretical perspective, it represents a step forward, since a new framework was applied to olive oil companies. To this end, the strategies of market orientation, networking and international entrepreneurship were adapted to the characteristics of the sector. For example, in international market orientation strategies, distributors, importers, and chefs are important, since they are the ones who have direct contact with the end consumers. This enables companies to learn the tastes, needs, and desires of consumers, which enables them to be more competitive. Thus far, we have not found recent research that indicates how companies in the olive sector can be internationalized based on the advantages of the region. Consequently, this work proposes the keys for these companies to have greater involvement in the economic, social, and sustainable development of their regions. Exporting companies can boost their sales, find more mature markets for certain olive oil segments, use more innovative and environmentally friendly production techniques, increase regional GDP, employment, and investment, train personnel in the harvesting and production of quality EVOO, collaborate with technological centers, learn new working methods from abroad, increase international networks, evolve in the olive culture, etc.

From a practical perspective, this research has implications for both private and public management. It offers guidelines so that they can contribute to: (a) improving the image of EVOOs abroad; (b) educating residents about olive culture; (c) investing in innovation linked to research and development from cultivation, which implies introducing new harvesting and production practices, installing more advanced mills, etc.; (d) strengthening international ties through distributors, customers, competitors, etc.; (e) learning about new marketing techniques; (f) lobbying political leaders to introduce a grading system for EVOOs that highlights the characteristics and quality of superior category oils, such as premium; and (g) encouraging organizations, associations, and local institutions to modernize themselves, and become more familiar with the foreign market. In this way, it would be possible for stakeholders to join efforts to make themselves known to the rest of the world; it would be especially useful for small entrepreneurs, without previous experience, but with the features needed to become international. In short, all of this will contribute toward the evolution of the culture of the olive grove and to the development of the region.

From the business point of view, the accelerated and early internationalization of companies means gaining knowledge, competitiveness, and flexibility; thus, adapting to the needs of international clients, which translates into bigger profits for the companies. At the same time, for the local area, it signifies increased employment, more trained and qualified people, new ways of understanding the production of EVOOs and of innovating, new relationships, etc. In short, it adds value to the region, although, in order to contribute to its development, it will be necessary to connect the following forces: the diffusion of innovation and knowledge, the creation of networks, the flexible organization of production, and the evolution of institutions and social capital.

Despite the contributions of this study, it also has some limitations. There is a need to broaden the study by introducing quantitative data. To this end, we suggest that in future research this inductive method be complemented with the deductive qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) using fs/QCA software. We also propose applying this model to other geographical areas in which olive groves are cultivated [13].

Author Contributions

The authors have contributed equally to this work. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following companies in the olive oil exporting sector in the province of Jaén for their participation and collaboration: Aires de Jaén, Castillo de Canena, Galgón 99, and El Trujal de la Loma.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have not identified any conflict of interest.

References

- Junta de Andalusia. Monthly Monitoring Report on Olive Oil, Prices and Markets Observatory, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. 2021. Available online: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/agriculturaypesca/observatorio/servlet/FrontController (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Benedito, I. Sólo Cuatro CCAA Superan la Renta per Cápita de la UE. Expansión. 2019. Available online: https://www.expansion.com/economia/2019/06/23/5d0fe6e7468aeb548b4632.html (accessed on 23 June 2019).

- Quispe-Fernández, G.; Ayaviri-Nina, V. Políticas de desarrollo de los procesos de desarrollo endógeno. Revista Líder 2013, 22, 151–187. [Google Scholar]

- Crick, D. The internationalization of born global and international new venture SMEs. Int. Mark. Rev. 2009, 26, 453–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhaddane, M.; Mili, S. A forecast of internationalization strategies for the Spanish olive value chain. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2018, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral-Pajares, E.; Lanzas, J. La exportación de aceite de oliva virgen en Andalucía: Dinámica y factores determinantes. Revista Estudios Regionales 2008, 86, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.D.; Gallego-Simón, V.J. Olive crops and rural development: Capital, knowledge and tradition. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2019, 11, 935–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Jurado, E.; Mozas-Moral, A.; Medina-Viruel, M.J.; Fernández-Uclés, D. Evaluation of corporate websites and their influence on the performance of olive oil companies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moral-Pajares, E.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.D.; Mozas-Moral, A.; Bernal-Jurado, E.; Medina-Viruel, M.J. Local resources and global competitiveness: The export of virgin olive oil in Andalucía. Boletín Asociación Geógrafos Españoles 2015, 69, 415–435. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Famoso, V.; Cano-Rubia, M.; Fuentes-Lombardo, G. El papel de los convenios de cooperación en la internacionalización de las empresas españolas de la familia de la bodega y el aceite de oliva. Rev. Int. Investig. Neg. Vitivinícolas 2019, 31, 555–577. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, I. Stratégies de L´écodéveloppement; Économie et humanism: Paris, France, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Aydalot, P. Milieux Innovateurs en Europa; GREMI: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Barquero, A. Desarrollo Endógeno. Redes, Innovación, Instituciones y Ciudades; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barquero, A.V. Reflexiones teórica sobre la relación entre el desarrollo endógeno y economía social. Revista Iberoamericana Economía Solidaria Innovación Socioecológica 2018, 1, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sanabria, S.; Pedraza, P.; Enrique, E. El emprendimiento como fuente de desarrollo y fortalecimiento de las capacidades endógegnas para el aprovechamiento de las energías renovables. Revista Escuela Aministración Negocios 2014, 77, 152–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furlan, A. Actuar en la crisis: El sistema eléctrico en la perspectiva del desarrollo endógeno. Análisis de caso de la costa atlántica bonaerense, Argentina, Equipo. In Proceedings of the “Grand Ouest” days of Territorial Intelligence IT-GO, ENTI, Nantes-Rennes, France, 24–26 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Sánchez-Martínez, J.D.; Garrido-Almonacid, A. Strategic responses of the European olive-growing territories to the challenge of globalization. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 28, 2261–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Barquero, A.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C. Desarrollo endógeno e instituciones: Desafíos para las iniciativas de desarrollo local. Environ. Plan. C Gov. 2016, 34, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furió, E. El desarrollo económico endógeno y local: Reflexiones sobre su enfoque interpretativo. Revista Estudios Regionales 1994, 40, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Mozas-Moral, A.; Fernández-Uclés, D.; Bernal-Jurado, E.; Medina-Viruel, M.J. Sostenibilidad, desarrollo endógeno y economía social. Revista Iberoamericana Economía Solidaria Innovación Socioecológica 2020, 3, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Eisehardt, M.; Martin, A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantunen, A.; Puumalainen, K.; Saarenketo, S.; Kyläheiko, K. Entrepreneurial orientation, dynamic capabilities and international performance. J. Int. Entrep. 2005, 3, 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudalige, D.; Azizi-Ismail, N.; Abdul-Malek, M. Eploring the role of individual level and firm level dynamic capabilities in SME’s internationalization. J. Int. Entrep. 2019, 17, 41–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.E. The internationalization process of the firm model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1977, 8, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, G.; Madsen, K.; Servais, P. An inquiry into born-global firms in Europe and the USA. Int. Mark. Rev. 2004, 21, 645–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemad, H. Revisiting interactions of entrepreneurial, marketing and other orientations with internationalization strategies. J. Int. Entrep. 2019, 17, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deutscher, F.; Zapkau, B.; Schwens, C.; Matthias, B.; Kabst, R. Strategic orientations and performance: A configurational perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos-Martínez, C.; Muñoz-Guarasa, M. Importancia de las capacidades dinámicas en el proceso de internacionalización: El caso de los KIS. Revista Economía Mundial 2020, 54, 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K.; Johanson, A.; Majkgärd, A.; Sharma, D. Experiential knowledge and cost in the internationalization process. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, J.; Rosado-Serrano, A. Gradual internationalization vs born global/international new venture models: A review and research agenda. Int. Mark. Rev. 2019, 36, 830–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, F.; Young, C. Toward a normative theory of normative marketing theory. Mark. Theory 2005, 5, 363–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Contractor, J.; Hsu, C.; Kundu, K. Explaining export performance: A comparative study of international new venture in Indian and Taiwanese software industry. Manag. Int. Rev. 2005, 45, 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S.; Hutchings, K.; Lazaris, M.; Zyngier, S. A model of rapid knowledge development: The smaller born-global firm. Int. Bus. Rev. 2010, 19, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gabrielsson, M.; Gabrielsson, P.; Dimitratos, P. International entrepreneurial culture and growth of international new ventures. Manag. Int. Rev. 2014, 54, 445–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, M.T.; Álvarez, M.T.G.; Pérez, R.M. La gestión del capital humano en el marco de la teoría del capital intelectual: Una guía de indicadores. Economía Industrial 2010, 378, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market orientation and the learning organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trillo, M.A.; Sánchez, S.M. Influencia de la cultura organizativa en el concepto de capital intelectual. Intangible Capital 2006, 11, 164–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno, E.; Salmador, M.P.; Merino, C. Génesis, concepto y desarrollo del capital intelectual en la economía del conocimiento: Una reflexión sobre el modelo intellectus y sus aplicaciones. Estudios Economía Aplicada 2008, 26, 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R.; Sytch, M.; Tatarynowicz, A. The rise and fall of small worlds: Exploring the dynamics of social structure. Organ. Sci. 2010, 23, 299–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menguc, B.; Auh, S. Creating a firm-level dynamic capability through capitalizing on market orientation and innovativeness. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A.; Ngo, V. Market orientation versus innovative culture: Two routes to superior brand performance. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 868–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monge, E.C. El estudio de casos como metodología de investigación y su importancia en la dirección y administración de empresas. Revista Nacional Administración 2010, 1, 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Villareal, O.; Landeta, J. El Estudio de Casos Como Metodología de Investigación Científica en Economía de la Empresa y Dirección Estratégica. Investigaciones Europeas Dirección Economía Empresa (IEDEE) 2010, 16, 31–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yacuzzi, E. El estudio de caso como metodología de investigación: Teoría, mecanismos causales, validación. CEMA Work. Pap. Ser. Doc. Trab. 2005, 296. Available online: https://ucema.edu.ar/publicaciones/download/documentos/296.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research, 4th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; Chapter 2; pp. 127–164. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera-Hintelholher, R.M. Identidad y diferenciación entre método y metodología. Estudios Políticos 2013, 28, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abreu, J.L. Research method. Int. J. Good Conscienc. 2014, 9, 195–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, A.; Gray, B. Bargaining power, management control, and performance in United States-China joint ventures: A comparative case study. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 1478–1517. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A.; Smallman, C.; Tsoukas, H.; Van de Ven, A.H. Process studies of change in organization and management: Unveiling temporality, activity and flow. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weick, K.E. The Social Psychology of Organizing, 2nd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A. Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Monin, P.; Noorderhaven, N.; Vaara, E.; Kroon, D. Giving sense to and making sense of justice in postmerger integration. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 256–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaillant, Y.; Urbano, D.; Criado, J.R.; Criado, A.R. Un estudio cualitativo y exploratorio de cuatro nuevas empresas exportadoras. Cuadernos Economía Dirección Empresa 2006, 29, 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research-Design and Methods, Applied Social Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Lederman, D.; Olarreaga, M.; Ribiano, E. Trade specialization in Latin America: The impact of China and India. Rev. World Econ. 2008, 144, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farré-Ribes, M.; Lozano-Cabedo, C.; Aguilar-Criado, E. La “nueva cultura del aceite” como eje de transformación en los territorios olivareros andaluces. AIBR Revista Antropología Iberoamericana 2020, 15, 79–104. [Google Scholar]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Gómez-Carretero, A.; Muñoz-Velasco, J.F. An industrial district around a mining resource: The case of marble of Macael in Almería. J. Reg. Res. 2015, 321, 33–148. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Muñoz-Guarasa, M. Empresa multinacional y desarrollo local: El caso Valeo. Boletín Instituto Estudios Giennenses 2006, 194, 245–259. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Martínez, J.D.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Garrido-Almonacid, A.; Gallego-Simón, V.J. Social innovation in rural areas? The case of Andalusian olive oil cooperatives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, M.; Fernandes, S. Smart innovation strategy and innovation performance: An empirical application on the Portuguese small and medium-sized firms. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2018, 11, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).