Abstract

Stakeholders’ participation is critical to implementing sustainable development models at mass tourism destinations. Through the application of a mixed methodology focused on the collection, processing, and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data, this study analyzes the perception of residents, accommodation establishments, the academic community, and tourists in the city of Seville, since they are the possible agents of change in the current model. In addition, the study of perceptions provides information to extract a definition of mass tourism for these groups. Findings show that the majority of those surveyed affirm the presence of mass tourism in the city, and choose carrying capacity as an instrument to predict this type of tourism. We also show that, while mass tourism is not a sustainable model, its transformation is possible. As a consequence, the tourists’, destination’s and local population’s tolerance limits would determine the size and direction of the tourist impact.

1. Introduction

Tourism began to grow as an economic activity after the Second World War, based on four key elements: the presence of a greater economic surplus in the population; changes in work systems (vacations); the landscape, natural and cultural resources of some regions, and technological advances in means of transport and communication [1]. When one of these key elements is weaker, there are a series of consequences. Tourism is not a harmless activity, since its uncontrolled and massive development has had significant repercussions for the natural environment, contributing to the degradation of the landscape and environment in various areas, including cities. An increasing and massive influx of visitors poses specific problems of tourist saturation, with all the negative effects that this entails [2]. This is one of the reasons why Butler [3] argues that tourism should be linked to sustainability, stating that if there is no equitable development of resources in a destination, uncontrolled planning emerges, which eventually turns into mass tourism. The sustainable model of tourism seeks to satisfy the needs of tourism, as well as those of the host regions; that is, to make tourism an economic source, attempting to eliminate the negative effects that tourists have on these areas without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs [4]. However, the concept of mass tourism has also been associated with positive effects, since a major part of income from tourism in the world comes from this type of tourism—in terms of income earned from tourist activities, mass tourism is one of the most important factors [5].

For years, the Fordist Tourism Model, characterized by mass production and economy of scale with high concentration, has been present in the management of many tourist destinations [6]. In fact, despite the appearance of a new, more differentiated and flexible development model in the 1980s [7], the model persists. Society started to use the expression “mass tourism” as an indication of its concern with the increase in tourists, which, paradoxically, it had contributed to feeding. Mass tourism is related to the carrying capacity of a territory, that is, the reaction and resilience of an environment to a certain occupational density, expressed in a limit occupation figure [8].

This leads us to reflect on the effects that mass tourism has in society (economic, social and environmental). This is even more true given that the COVID-19 pandemic has placed us in the context of a global health and economic crisis never before experienced. Tourism has played a very important role in the recovery from the main crises experienced by Spain (1981, 1993, and 2008) [1], which have all shown similar patterns. This means that existing theories can often explain the phenomena observed today. The 2008 economic crisis, known as the Great Recession, registered negative growth in the tourism sector, although at the same time, new market models emerged [9].

Although we have mentioned four key elements that boosted tourism, the health crisis due to coronavirus has brought us a fifth: health has entered the scene, taking center stage. In another era, we might have accepted that if the economy works, tourism works. However, without health, the economy does not work, and therefore, neither does tourism. Despite this, the slowdown of tourist activity has not only alleviated CO2 emissions, but also reduced the overexploitation of natural and heritage resources in many tourist destinations. Many historical and monumental cities are benefiting from this decrease in the number of tourists, which has allowed the regeneration of natural resources [10]. The arrival of the vaccine against COVID-19 is postulated as a definitive measure to stop the pandemic, since natural immunity would mean a high number of deaths, especially among individuals belonging to risk groups [11]. The current situation represents an opportunity to consider the transformation of the global tourism system towards one that better aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030, and a boom in this market after the pandemic [12].

In addition to the above, there is the fact that in some urban spaces, mass tourism is incompatible with residential use, since it profoundly affects aspects such as house pricing [13], the nature of business, the use of public spaces, air quality, etc. Moreover, the effects of these processes in the historic centers of cities are contradictory, since they damage and can even destroy some of the intangible heritage value of cities and, therefore, their attractiveness [14]. This is the case in the city of Seville, a city with a vast historical heritage and potential; it is the fourth largest city in Spain, the capital, and the most populated urban conurbation in Andalusia. It has nationwide interconnection with highways that communicate with the rest of Spain, as well as an airport [15].

On the other hand, it became the focus of attention at national level with the 1992 Seville International Exposition, which triggered major urban modification and promoted an internal restructuring of the city [14]. After the 2008 crisis, the specialization of tourism in Seville grew even faster, making it the fashionable destination it is today, and breaking records with more than 3 million visitors in 2018 [16]. In the process of expanding tourism, the insertion of services oriented towards the needs of visitors implies new businesses oriented towards leisure [17]. This commercial transformation has a direct impact on the public space, since, together with new bars and restaurants, the privatization of squares and streets extends with the installing of tables, chairs, etc., which in turn has an impact on the landscape [18].

Our research aims to analyze the perceptions of the different stakeholders involved, who permanently coexist with tourists in the city of Seville, and who can therefore contribute to changing the current model. These include residents, the academic community, tourists, and accommodation establishments (henceforth, accommodations). The latter are defined as those establishments whose main activity is to offer accommodation to people, by price, on a regular and professional basis, with or without other complementary services, through the generic name of a hotel, hostel, pension, or similar [19]. For the purposes of this study, in addition to the above, tourist apartments have been added to this group.

The findings of this study can provide practical means of creating tourism that is more sustainable, since the uncontrolled, massive development of tourism has negative repercussions for the natural environment [2], which is why sustainable tourism implies not only economic profitability, but also social welfare and ecological balance [20]. After this introduction, this paper proceeds as follows: Section 2 introduces a complete review of the literature, delving into the conceptual connotations of mass tourism. Section 3 proposes the research model through a mixed methodology. Finally, Section 4 shows the results obtained, and Section 5 and Section 6 offer a discussion and final conclusions, limitations, and potential topics for future research.

2. State of the Art

The democratization of tourism, part of the configuring of the welfare society [21,22,23], led to mass tourism in the second half of the 20th century [6,24]. The number of tourists worldwide grew uninterruptedly until 2020, as did the industry, from 25 million in the 1950s to 1500 million [25,26,27,28,29].

The previous literature (Table 1) has shown us that the definition of mass tourism has been changing. However, there are elements that are repeated in the contextualization of some authors. As [30] indicates, these concepts present in the literature derive primarily from the experiences of destinations. Some, such as [31], relate it to the carrying capacity of a territory, which may be related to the perception of [32], which considers it a quantitative concept.

Others authors [33,34,35] point out that it is more related to the participation of a large number of people, and to standardized, inflexible and rigidly packaged vacations. This can generate, as mentioned in [36,37], a seasonal, concentrated form of tourism, mainly around the modality of sun and sand, which incorporates the features of monoculture, single product, coastline, seasonality, “residentiality”, domesticity, and urbanization without urbanity.

On the other hand, some authors [38,39] refer to the scarce contact between residents and tourists. This may be because, as mentioned in [40,41], many businesses dedicated to this activity are not located in the territory. In fact, under this conceptualization, mass tourism would be a product created by companies outside the destination who do not aim to integrate themselves into the city.

Table 1.

Conceptual connotations of mass tourism.

Table 1.

Conceptual connotations of mass tourism.

| Conceptual Connotations of Mass Tourism | Authors |

|---|---|

| Designed to be marketed to large numbers of tourists, offers minimal opportunities for contact and understanding between hosts and tourists. | [38] |

| Related to the carrying capacity of a territory. | [31] |

| A quantitative concept. | [32] |

| Refers more to the impact on the local environment than to the number of tourists. | [24] |

| Is related to two main characteristics: (a) participation of a large number of people in tourism; and (b) standardized, rigidly packaged, and inflexible vacations. | [33] |

| Holidays are standardized and rigidly packaged (including transportation, accommodation and sightseeing); mass-produced by a low number of bidders; marketed to an undifferentiated clientele; consumed by tourists regardless of norms or local culture. | [34,35] |

| Generates a seasonal, concentrated tourism, mainly around the modality of sun and sand. | [36,37] |

| Ownership of the companies that exploit this tourism is not usually local. | [40] |

| Characterized by homogenization, chain production, theatrical authenticity, spatial concentration. | [41,42] |

| Consists of: monoculture, single product, coastline, seasonality, “residentiality”, domesticity, and urbanization without urbanity. | [43] |

| Concepts present in the literature derive primarily from the experiences of destinations. | [31] |

| Highlights the aspect of inappropriate or non-existent contacts among residents and tourists. | [38,39] |

Source: Authors.

Tourism, which was first perceived as a social achievement, unlimited and harmless, with wonderful economic effects in certain regions, began to show its negative consequences, and voices spoke out against it, particularly in the crowded Mediterranean destinations that hosted it [44]. Not surprisingly, the scientific publications addressing the phenomenon since the early 1970s have mentioned its negative consequences, relating it to health problems and pollution [45,46,47,48,49,50]. At an empirical level, various authors have shown that residents care about the numbers and types of tourists who visit them [51], and that tourists have economic [52,53], cultural [54], social [55], and sociocultural impacts [56] on the sustainability of the environment [3,57,58], politics [59], urban planning [60], and technology [61]. These consequences do, however, depend on an understanding of the perceived impacts on employment and income, the development of infrastructures, and care for the environment (degree of local development), as well as on the use of tourist resources by residents [62,63].

The economic, social and environmental subsystems in the area of a tourist destination have a certain load capacity. The tolerance limits of tourists, the destination and the local population determine the magnitude and direction of the tourists’ impact. What does not exceed these limits can be positive, but everything that exceeds the tolerance threshold will be perceived as negative, with the resident feeling that the place no longer belongs to them, and with the visitor believing that authenticity is nowhere to be found [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74].

In fact, since the 1990s, a growing number of tourists and residents, the European Council itself, and even the UNWTO have called for limits and a qualitative change to mass tourism, which would harmonize the rights of tourists, present and future, with those of the local population and respect for the environment. This commitment is not only to reductionism, but to sustainable, complex adaptive systems that integrate human and natural systems, as reflected in the scientific literature [75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98].

Numerous studies and a body of academic research exist that analyze the great tourist potential of certain cities [99], such as Seville. This city enjoys a diversity of resources that specialize in cultural tourism, which acts as an attraction factor [14,100,101,102]. However, the rapid growth of a tourism economy in the urban area has caused certain economic, social, spatial and environmental changes among local communities [103,104,105,106,107,108]. The objective must consist of a firm commitment to sustainable territorial and tourist development, integrated into the local economy and society, which is also respectful of cultural and environmental heritage.

Under the assumption that it is possible to start, direct and change tourist flows, the commitment should be to the development of sustainable mass tourism, as the desired result for most of the destinations in which conventional tourism has reached the end of its life cycle [109,110,111,112,113,114,115]. In this sense, although its development represents an acknowledged difficulty, it is necessary to find an alternative mass tourism that is enlightened, viable and credible, and in which carrying capacities gradually increase to adapt to higher levels of visits [60,72,115,116,117,118]. In any case, such tourism constitutes an option to tackle the future recovery of the sector after the global pandemic, conditioned by the success of vaccination against COVID-19 and the ability to alleviate social distancing restrictions.

In order to understand mass tourism and redirect it towards sustainable mass tourism, it is essential to know the perceptions and attitudes of the different agents operating in a destination, as well as those of the tourists themselves [119,120,121,122]. The theories that analyze these social perceptions derive chiefly from social psychology and sociology. Among others, the theories of social representations [123,124], attachment to the community [125,126], the growth machine [127,128] and social exchange are worthy of note. Furthermore, a common thread between these theories is that they consider the dynamic and progressive nature of changes in perceptions as tourism and its impacts change. Hence the importance of conducting periodic empirical studies that assess the perceptions of different agents.

Freeman’s Stakeholder Theory (1984) suggests that an organization is characterized by its relationships with various groups and individuals, including employees, clients, suppliers, governments, and community members. In this sense, for the proper functioning of an organization, it is necessary that all the interests of each of the groups be taken into account [129]. The so-called agents or strategic actors (stakeholders) constitute the interest groups or parties concerned with the permanent and cooperative processes of tourism governance [130]. The development of a destination in terms of the field of tourist activity is largely determined by the relationships that exist between the actors that are included in it [131].

The literature review has revealed the important role of local residents in the development of tourism in their city. In fact, research such as that by Sdrali, Goussia-Rizou, and Kiourtidou [132] highlights the importance that this stakeholder group can have by becoming involved and feeling part of the development project. In this line, the establishments not only contribute to economic development by providing employment, but also become a stakeholder in the sustainability of the destination, as their activity will depend on it [133]. For their part, policies need to bring together as many stakeholders as possible, since the development of a tourist area may depend on the decisions made by this group. Proof of this is given by the numerous studies on the impact of policies on the tourism sector [134,135,136,137].

Thus, at a political level, the impact of tourism is one of the challenges when rethinking the city and socio-spatial segregation, from the perspectives of both infrastructure, which leads to new real estate bubbles, and the sociology of everyday life. Analyses of the perceptions of the impact of mass tourism in the city of Seville must therefore be comprehensive in order to reveal and understand the diverse perceptions of the different actors and social groups affected by and/or involved in the rapid expansion of urban tourism in the centers of many European cities [17,138].

In order to undertake this study adequately, we posed the following research questions:

RQ1—What is understood by the term “mass tourism”?

RQ2—What are the positive and negative impacts of mass tourism, as perceived by stakeholders individually?

RQ3—What are the positive and negative impacts of mass tourism, as perceived by stakeholders in a certain destination?

RQ4—Does mass tourism exist in the city of Seville?

RQ5—Could mass tourism become a sustainable model?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

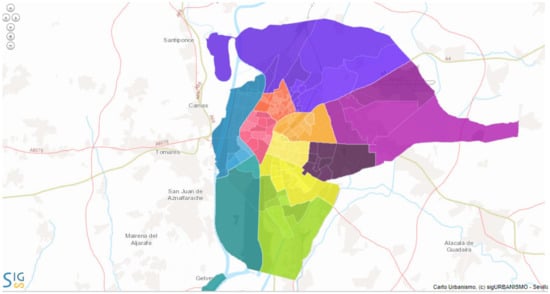

Seville is the capital of Andalusia (Figure 1). This province is the largest in the autonomous community. It borders the provinces of Malaga and Cadiz to the south, Huelva to the west, Badajoz to the north, and Cordoba to the east.

Figure 1.

Location under study. Source: Authors.

This city has experienced one of the biggest urban transformations. The continuity of the same political party and, therefore, of the same strategy, the celebration of the fifth centenary of the Discovery of America, and the success of the celebration of the Universal Exposition in 1992 were the starting points for a favorable urban development [139]. Despite being an inland territory, the Guadalquivir River became the backbone of the city’s urban plan. Its climate, its historical heritage, and its two great attractions, Easter Week and the April Fair, have made the destination world famous. Its historic center, an area of 2 square miles, has three monuments declared World Heritage Sites by UNESCO: the Alcazar palace complex, the Cathedral, and the General Archive of the Indies. The study area has been delimited to the municipality of Seville. This can be seen in Figure 2. This city is also the most populated in Andalusia, with 691,395 inhabitants [140].

In 2017, tourism generated 17% of Seville’s total wealth [141]; in this area, 2019 was a historic year. Seville had a record 3.12 million travelers staying in hotels and apartments, 6.7 million overnight stays, and an occupancy rate of 76.4% [142,143]. In relation to the Spanish market, the community of Andalusia itself was the main attraction of Seville, with 435,911 tourists and a 0.91% increase. However, the crisis due to the worldwide pandemic derived from COVID-19 meant a loss of 74% in overnight stays [144].

Figure 2.

Municipality of Seville. Source: Sigs GeoSevilla [145]. As can be seen in Figure 2, the different colors represent the central districts of Seville.

3.2. Sampling, Data Collection, and Analysis

Studies involving qualitative methodology are still scarce in the academic literature [146]. However, as indicated by Tashakkori et al. [147], research questions coming from social science studies are more adequately answered through a mixed methodology. In fact, there are numerous investigations that have applied both quantitative and qualitative methods in their research [148,149,150,151,152]. This is largely because, while quantitative analysis quantifies the data, qualitative analysis interprets them [153], so it is necessary to attend to the needs of the research in order to choose the most appropriate one. This research proposes a mixed methodology since, as Mackey and Bryfonski [154] state, the combination of both approaches allows the researcher to examine a problem from complementary points of view.

As such, the study design focused on the collection, processing, and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data. This research analyzes the perceptions of residents, tourists, accommodations, and academics regarding mass tourism in the city of Seville. It also analyzes which of the definitions provided by the academic literature is the most appropriate for each of the groups under study. From the study of perceptions, a definition of mass tourism for residents, accommodations, academics, and tourists in the city of Seville can be extracted. Despite the efforts made by the researchers, no response could be obtained from the politicians.

The study was carried out in different phases. To ensure the relevance of the questionnaire, a pre-test was carried out with residents, academics, and accommodations. In the residents’ pre-test, the questionnaire was distributed proportionally amongst genders, ages, levels of study, and districts. In the particular case of tourists, pre-testing could not be carried out due to confinement and perimeter closure. The pilot study of accommodations was distributed based on category. No modification of the survey was necessary. Regarding residents, the survey was conducted through a simple random sample. For the study on accommodations, we extracted a list from the VisitaSevilla [155] website and telephone surveys were conducted. Regarding academics, the questionnaires were sent by mail to all the professors who teach Tourism at the university. Once the perimeter confinement was cancelled, the tourist surveys could be conducted. We conducted questionnaires with 297 residents (sampling error 4.95%, reliability 91), 207 accommodations (sampling error 4.95%, reliability 95%), 25 tourists, and 10 tourism faculty professors from March 2021 to June 2021. All the respondents participating in this study gave their consent to being a part of this research. The interviews were imported, translated, and codified into NVivo 12 and SPSS for data management and data analysis.

The questionnaire was structured into five sections (See Appendix A). The first section includes a closed question about the existence of mass tourism in the city of Seville and an examination of the definitions of mass tourism given by the academic literature. The second section includes, for each of the groups, two open questions about perceptions (either positive or negative) in relation to mass tourism. In the case of accommodation, the two open questions deal with the positive or negative perceptions in relation to their professional activity, while for tourists, these were related to the impacts they suffer, or benefits they derive, from mass tourism. The third section concerns the positive or negative perceptions of mass tourism in the municipality of Seville. The fourth section identifies how mass tourism could contribute to the revitalization and recovery of tourism, as well as whether the mass tourism model can be sustainable in case the respondent considers that it is currently not. Since these are open-ended questions, the same answer may have one or more different impacts. The fifth section incorporated social and demographic characteristics; the variables analyzed were gender, age, occupation, and district. In the case of accommodations, this last section analyzed the category of the accommodation, the district, and years of professional activity.

4. Findings

This section outlines the findings of the study. They are shown for each group of interest.

4.1. Mass Tourism: Existence and Definition

Mass tourism has been extensively studied in the academic literature. As a result, there are numerous definitions of this phenomenon. The objective of this research was not only to analyze the perceptions, but also to elaborate a definition, of this type of tourism. To this end, all the interest groups were asked whether or not, based on their perceptions, mass tourism exists in the city of Seville (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Mass Tourism existence in the city of Seville.

If we take into account the perceptions of all groups in general, we can observe that, except for professors, the groups agree in affirming that mass tourism does exist in the city of Seville. However, some aspects should be clarified. There is a very wide difference among the perceptions of the different categories of accommodations. In this sense, the highest-category hotels (5 stars and 4 stars = 33) affirm that mass tourism does not exist in the city of Seville (18%, 39%, respectively). In fact, the responses reveal that, to avoid oversaturation, they create new tourism products and other ways of approaching local traditions. This perception is not shared by the rest of the accommodations (3 stars and below = 174), which state that mass tourism does exist (81.61%) and define it in relation to the carrying capacity, the impact on the environment, and the concentration of tourism in certain periods. In order to better understand these findings, some transcripts representing the majority perception are shown below.

Respondent 103—5-stars hotel:

We believe that mass tourism does not exist because although there is a pronounced seasonality, the city does not reach its carrying capacity. In this sense, we try to provide services that decentralize the tourist activity of the saturated spots and that can provide a more exclusive and even private experience or service.

Respondent 4—4-stars hotel:

If we take into account that mass tourism is a massive tourism, a tourism that makes the resources of the city useless, Seville does not suffer from this type of tourism.

Respondent 201—3-stars hotel:

Mass tourism does exist. Although on the one hand it improves our income, we must recognize that we depend on what the city has to offer. Without our heritage, local friendliness, and history we would do nothing… We do not have the economic capacity to generate exclusive services and that is why we rely on many local businesses. We are dependent on the tourism management capacity of public administrations.

Respondent 156—Hostel:

I don’t know if the term is mass tourism but there is a lot of tourism, much more than the city can handle. This would be good for business if it did not have so many negative repercussions for the environment.

Respondent 297—Tourist Apartment:

Yes, there is mass tourism and in fact the tourist apartments have shown that the city is in great demand. Every year without counting the pandemic we have grown in number and profitability. We hope to continue growing.

This was followed by a question in which the subjects had to choose the correct definition or definitions for mass tourism. Table 3 shows the responses of each of the groups. The most cited definitions in the literature were chosen after conducting a study employing Proknow-C methodology.

Table 3.

Most appropriate definitions of mass tourism according to study groups.

As can be seen in the table above, the respondents chose “It is a quantitative concept associated with the spatial concentration and carrying capacity of a territory.” as the definition that best defines mass tourism. This indicates that all groups in this study share the same concept of mass tourism.

4.2. Residents’ Perceptions of Mass Tourism

A total of 297 questionnaires were completed. The sample is representative of the city of Seville in relation to gender (363,382 women = 52.56% and 328,013 men = 47.44%); 55.6% of respondents were women (168) and 44.4% (129 respondents) were men. In total, 91.92% of the sample were born in the municipality of Seville or had lived there for more than 10 years. The age groups and levels of study are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Socio-demographic data.

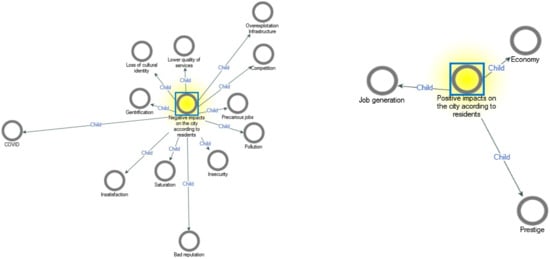

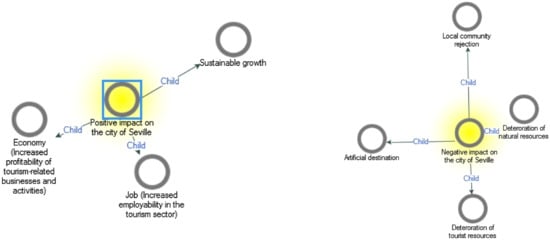

To explore residents’ perceptions about the impacts of mass tourism, they were asked about two aspects. The first questions were in relation to the positive and negative impacts of mass tourism on their lives as residents (Graphic 1). Secondly, the impacts on the city were discussed (Graphic 2). To illustrate this analysis, two diagrams are presented.

As can be seen in Scheme 1, the residents state that the most important positive effect is the “economic” (41.75%) aspect, followed by “employment” (37.71%). The most cited answer after the two previous ones was “there are no positive aspects of mass tourism” (codified as “No positive aspects”) (9.43%). This percentage may be related to the high number of negative impacts that residents associate with mass tourism (4 positive vs. 10 negative impacts). Among them, we can highlight “overcrowding” (mentioned in 28% of total responses = 83 residents), loss of purchasing power (20% = 60 residents), “insecurity” (12% = 36 residents), “environmental impact” (11% = 32 residents) and “employment-related” (10% = 30 residents) aspects. If we delve deeper into the latter, residents mentioned the “precariousness of employment” associated with a massive, low-quality product that needs to save costs in order to be competitive. It is interesting to note that the spread of coronavirus appeared as a negative effect (code = “COVID”).

Scheme 1.

Diagram of codification for the positive and negative impacts of mass tourism on local people. Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

Scheme 2 shows the effects of mass tourism on the city of Seville. “Economy” and “generation of employment” are the two most cited impacts (250 and 243 mentions, respectively), followed by “prestige” (63 mentions). In relation to the negative effects, “gentrification” (67% of respondents refer to the process of displacing = 199 residents) and “precarious jobs” (59.93% of respondents = 178 residents) stand out, followed by “insecurity” (57.91% of respondents = 172 residents), “saturation” (42% of respondents = 124 residents), and “pollution” (29.97% of respondents = 89 residents). It is interesting to note that in addition to these aspects, residents believe that mass tourism causes excessive competition among businesses in the city, which is related to the low quality of services. In addition, residents are concerned about the “loss of cultural identity” (27.95% of respondents = 83 residents) and the “bad reputation” (5.72% of respondents = 17 residents) that this type of tourism may create for the city.

Scheme 2.

Diagram of codification for the positive and negative perceptions of residents regarding mass tourism in the city of Seville (Impacts on the city). Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

Although there are no significant differences in relation to age or educational level, there are significant differences in relation to gender. Most of the responses that included “prestige” as a positive effect were contributed by women under 40 years of age. Employment was mentioned equally by both genders (137 men vs. 113 women mentioned it); however, men mention “employment” and “economy” separately, while women related both attributes in their answers.

4.3. Accommodations’ Perceptions about Mass Tourism

A total of 207 accommodations were surveyed. The sample was distributed among 5-stars hotels (2.41%), 4-stars hotel (13.53%), 3-stars hotels (7.73%), 2-stars hotels (6.28%), 1-star hotels (3.86%), hostels and guesthouses (30.43%), and tourist accommodations (35.76%). It should be mentioned that this investigation was carried out during the state of alarm declared by the Spanish authorities. This brought tourism activity to a standstill. In fact, even today (June 2021), a total of 173 accommodations remain closed [156].

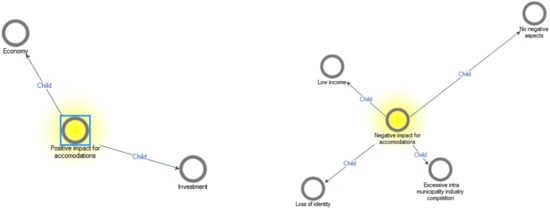

In relation to the positive impacts of mass tourism on the tourism business activity of Seville’s accommodations, only two aspects stand out (Scheme 3). On the one hand, mass tourism helps the economy and its growth, and on the other hand, it provides better investments for the city. In order to more easily understand their answers, two transcriptions are given.

Scheme 3.

Diagram of codification for the positive and negative perceptions of accommodations regarding mass tourism (impact on their business). Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

Respondent 13—Hostel:

Mass tourism collaborates with the economy of the city of Seville. Thanks to the fact that more tourists come and spend their income in the city, there is a movement that puts millions of euros into circulation.

Respondent 199—3 stars Hotel:

Mass tourism needs infrastructures and therefore investments. The city is looking for more tourism and the public authorities know that it is necessary to invest in the improvement and sustainable development of the city.

The negative aspect most cited by the accommodations is the excessive competition within the municipality (49.75%). This fact may be associated with the second element, “low income” (31.40%). It should be noted that despite the fact that three negative aspects are cited by this group, the coding diagram shows that 9% of accommodations perceive no negative impacts of mass tourism on their business.

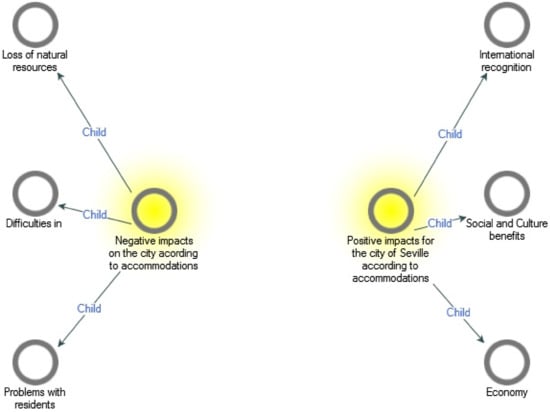

If we analyze Scheme 4 (on the negative and positive impacts of mass tourism in the city of Seville), we can observe that the aspects that most concern the accommodations are the difficulties in progressively changing the tourism model (58.94%), the problems that the coexistence of tourists and residents generate in the city (40.57%), and the “loss of natural resources” (32%). On the other hand, “social and cultural benefits”, economic improvement, and “international recognition” are the aspects most mentioned as positive impacts (49.76%, 45.89%, and 33.82%, respectively).

Scheme 4.

Diagram of codification for the positive and negative perceptions of accommodations regarding mass tourism (impact on the city). Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

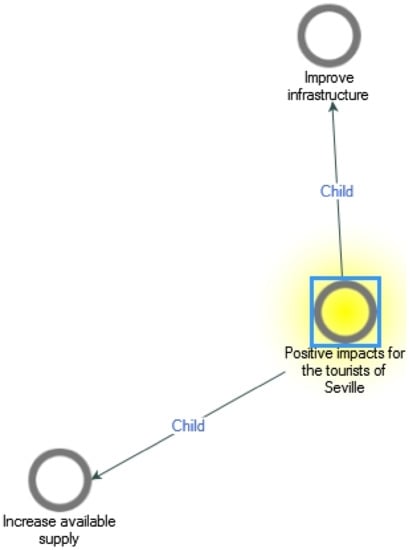

4.4. Academic Professors’ Perceptions about Mass Tourism

A total of 10 professors completed the survey. It should be noted that the academic community expressed much more detailed opinions than the rest of the groups. No differences were observed between individual impacts and impacts on the city. This is why overall perceptions are presented in the same diagram (Scheme 5). As a positive aspect, they highlighted the increase in income caused by mass tourism (80%). This is related to an increase in employability in the sector (90%). In other words, if more tourists come, more income is generated, more personnel are required, and there is therefore more employment. However, concerning the negative impacts, the most important is the “deterioration of natural resources” (70%). This is not only an impact on the city, but also on its residents. The “deterioration of tourist resources” (60%) or becoming an ‘”artificial destination” (40%), together with residents’ rejection of mass tourism (20%), are the elements that make up the coding diagram of the negative impacts.

Scheme 5.

Coding diagram on professors’ perceptions of mass tourism. Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

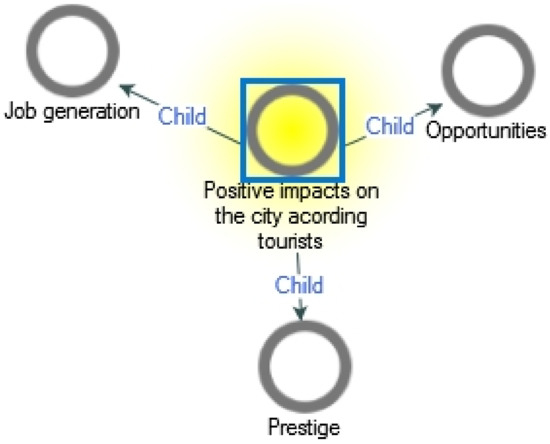

4.5. Tourists’ Perceptions of Mass Tourism

Regarding the perceptions of tourists, the surveys were carried out in the center of Seville. A total of 25 questionnaires were completed. It was not possible to obtain a larger number of respondents due to the perimeter closures imposed by the Andalusian Government. The responses provided by this group are shown in the following Scheme 6:

Scheme 6.

Diagram of codification for the positive perceptions of tourists regarding mass tourism in the city of Seville (impact on tourists as individuals). Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

The tourists stated that, thanks to mass tourism in the city, there is greater investment in infrastructure, and they cited this as a positive impact on themselves, since they benefit from these improvements (Scheme 7). In this sense, they stated that mass tourism increases the available supply, so that prices are lower and they have an exponentially increasing number of possibilities and opportunities to choose from. However, in relation to the impacts on the city, tourists recognize that mass tourism provides greater employment, external recognition, and more business opportunities.

Scheme 7.

Diagram of codification for the positive perceptions of tourists regarding mass tourism in the city of Seville (Impact on the city of Seville). Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

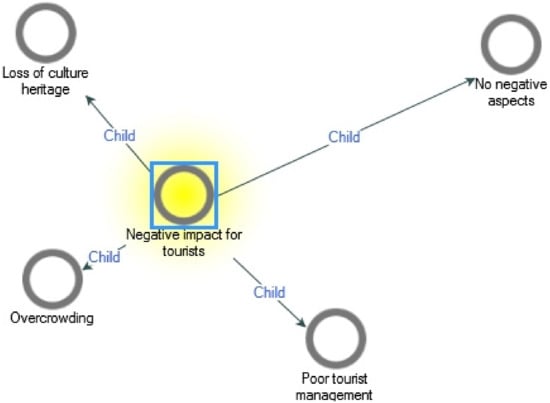

In the analysis of the negative effects, important results came to light. Tourists do not differentiate between the negative impacts they suffer and those that the city may suffer. According to their perceptions, overcrowding or loss of cultural identity are impacts that both they and the city suffer. On the one hand, they affirmed that sometimes it is not easy to visit a monument when thousands of other people are also contemplating it at the same time. As such, they are sometimes forced to finish their visit earlier, something they would tell their friends about. This would then have repercussions for the city. Despite this, as it can be seen in Scheme 8 a quarter of the tourists surveyed indicated that this type of tourism has no negative effects on them or on the city.

Scheme 8.

Diagram of codification for the negative perceptions of tourists regarding mass tourism in the city of Seville. Note: Closer to the core, higher percentage of responses. Source: Authors from NVivo 12.

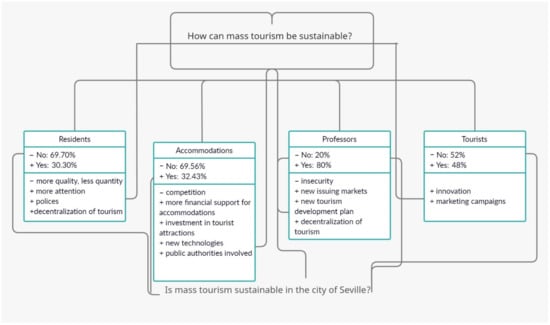

4.6. Sustainable Mass Tourism

This section explores whether mass tourism is a sustainable type of tourism, and, if it is not, what measures could be taken to make it sustainable in the city of Seville. For a visual representation of the results, the reader is referred to Scheme 9.

Scheme 9.

Overall findings regarding mass tourism and sustainability. Note: Existence and sustainability of mass tourism in the city of Seville according to the groups under study. Source: Authors.

5. Discussion

This research aims to explore the existence and impacts of mass tourism in the city of Seville via the perceptions of residents, accommodation, academic professors and tourists, as well as the most accepted definitions among these stakeholders. In line with tourism impact studies, it is possible to classify mass tourism impacts. In this case, the categories are employment, economic, environmental, cultural and urban planning, which cohere with the findings of other authors in the literature [52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60], who established that tourism generates impacts in terms of economic, cultural, social, environmental and urban planning.

The results demonstrate two things. Firstly, related to the first and fourth research questions, the majority of those surveyed affirmed that mass tourism is present in the city of Seville. Despite the fact that the academy has conceptualized mass tourism in different ways [24,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], the findings reveal that the key definition concerns the carrying capacity [31], which indicates that the agents do not consider whether the tourism is seasonal or is related to the sun and the beach, as stated by some authors [36,37]. In line with previous studies [8,54,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74], the economic, social and environmental subsystems of an area that is a tourist destination have a certain carrying capacity. It is clearly shown that everything that does not exceed these limits can be positive, but everything that exceeds a tolerance threshold will be perceived as negative, causing residents to feel that the place no longer belongs to them, and leaving the visitor with the impression that authenticity is nowhere to be found. The consequence of this is that the magnitude and tolerance limits of tourists, the destination, and the area’s local population determine the direction of the impact of tourism.

Secondly, for the second and third research questions, the stakeholders took different approaches. Regarding residents’ perceptions, and in line with previous studies [52,53], we can state that each impact can be perceived from both a negative and a positive point of view. Employment or the improvement of the economy seem to be the key, and are related to the economic impact. The economy is an issue of concern to all stakeholders, as is shown in previous studies [52,53], and this is supported by the high percentage of mentions per case under study. However, they are also concerned about low-quality and qualification employment, which also bring about poor conditions and therefore low salaries. As other studies have noted [36,37], little training exists, and there are no possibilities for advancement.

From these results, it is clear that, for the residents of the city of Seville, mass tourism is that which benefits the economy, but at the same time overcrowds their city, increases competitiveness among their businesses, lowers prices, and offers low-quality employment. This result links well with previous studies, which state that mass tourism has impacts on employment and income, the development of infrastructures, and care for the environment (degree of local development), as well as the use of tourist resources by residents [62,63]. The members of this group are the ones who are most in contact with tourists, since they are the ones who live with them. The rest of the stakeholders gave their opinions based on their knowledge in this regard, but not on what they had experienced in the first person.

As for accommodation, mass tourism produces economic benefits, but reduces the possibility of changing the model. In addition, this group affirmed that mass tourism can generate serious conflicts with the inhabitants and losses of natural resources, as the literature has already indicated [24,30,34,35,43]. These authors state that mass tourism is a model designed for marketing to a large number of tourists, which offers minimal opportunities for contact and understanding between visitors and hosts, with more reference to the impact on the local environment than to the number of visitors. This generates inappropriate or non-existent contact with residents, but does not take into account local rules or culture.

However, mass tourism is responsible for international recognition, and the cultural and social enrichment that comes from being in contact with people from other parts of the world, an important issue asserted by [54,55,56], who state that tourism generates cultural, social and sociocultural impacts.

In their responses, professors related impacts from different perspectives. However, although they offered the same definitions as the other groups, they considered that tourism in the city of Seville has not reached a sufficient level to be called mass tourism. This academic community stated that mass tourism is associated with carrying capacity, an opinion shared with other stakeholders, but they also stated that in Seville, it has not yet been overcome, so that for them, there is no mass tourism in the city. This opinion is similar to that of some of the accommodations, such as 4- and 5-star hotels. However, this differs from the opinions of residents, who do perceive mass tourism, just as it is perceived by 1-, 2- and 3-star accommodations, as well as tourist hostels and apartments. These results support the idea that this model generates seasonal, concentrated tourism [36,37]. In spite of this, they recognize that the city is progressing towards saturation, and propose alternatives that, as an initial step, include a new tourism development plan in which all groups are involved.

Despite the efforts made by the authors on several occasions, it was not possible to obtain a response from the political group. This fact implies that political groups are not playing their role, since they are generating policies without taking others into account, which breaks with the stakeholders’ theory. Something that all stakeholders agree on is that this concept is associated with carrying capacity, and regardless of whether they consider it to exist or not, to prevent it, we need less quantity and more quality—that is, new policies focused on innovation (as indicated by tourists) and on seeking new destinations (as indicated by teachers). For mass tourism to be sustainable, there does not have to be quantity, competition or insecurity, but rather new technologies and new policies.

Tourists, for their part, state that mass tourism forces the city’s infrastructure to improve, as [62,63] pointed out. They take advantage of this, just as they benefit from the competition that exists in the sector. In this sense, they recognize that the city of Seville has a large availability accommodation, especially in the most central neighborhoods.

Regarding the fifth research question, mass tourism is not a sustainable model, but it could become one. Tourism remains unquestionably a social achievement, and proof of this is given not only by the economic impacts it has in the communities. Additionally, as Bramwell [44] stated, some agents claim negative effects that a good use of resources could remedy. This is also mentioned by other studies [109,110,111,112,113,114,115], who stated that sustainability was an objective that could allow the continuity of the mass model, and it is also emphasized that this type of tourism does not lose pace. The results indicate that this type of tourism could continue if planning is imposed that takes into account the perceptions and attitudes of the different agents involved [119,120,121]. To this end, several solutions have been proposed, outstanding among which are the improvement of tourism policies, more attention to residents, the decentralization of tourism, control of tourist licenses, new source markets, and the elimination of seasonality through the enhancement of historical heritage.

6. Conclusions

Mass tourism has become a main economic driving force in Spain [6]. It is also a model that does not have to decline inexorably, and it can continue to be competitive and is even recommendable in certain circumstances [44,157,158,159]. Likewise, it has acted as a window on the outside world and become part of the modernization process, as it accompanied social and cultural changes towards the spheres of capitalist, democratic countries [160,161,162].

The main objective of this study was to analyze, by means of a mixed methodology, the perceptions of the different stakeholders who coexist with tourists in Seville. In addition, we studied the presence of mass tourism in the city, the impacts that it has generated, and the commitment to a model of sustainable mass tourism. Although tourism has positive effects, it requires the environment not be degraded, since tourism cannot be separated from the environment, or from the residents or the rest of the agents involved. As reflected in the literature on this topic [58,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98], reductionism is not a single undertaking—it also involves complex adaptive systems that are sustainable; that is, an enlightened, viable, credible alternative mass tourism that integrates human and natural systems, in which carrying capacities gradually increase to accommodate higher levels of visits [60,72,115,116,117,118].

One of the limitations found was the lack of tourist subjects due to mobility restrictions not only in Seville, but also worldwide, at the time this study was carried out, and so future research should increase the sample size. There were also limitations in the sample corresponding to the group of politicians, as they did not agree to participate in the survey. The separation of political power from the other groups derives from this, since if communication does not exist between them, the policies implemented will lack the sufficient knowledge of the needs and expectations of the other groups, and their involvement in the life of their town.

The group of university professors contributed more concrete opinions. However, despite the fact that all of the subjects were offered the same definition, unlike the other stakeholders, the teachers did not consider that mass tourism exists in the city of Seville. This proposes another possible line of research that would use existing definitions to implement more studies in real contexts with the participation of all interest groups.

Another future line of research could be to study the sporadic peaks in tourism that the city experiences at designated times, to which the academic community refers. These lead to the implementation of planning measures that allow anticipating and decentralizing this kind of tourism, which, in a city like Seville, is responsible for ensuring that the destination has international recognition, and is therefore culturally and socially enriched. We propose a joint, comprehensive analysis of all the costs and effects created, since the long-term competitiveness of tourism requires the generation of alternative, adapted models that are more differentiated, flexible, and respectful of the environment and local populations, while being economically feasible [37].

Finally, tourism has many other aspects that can influence the attitudes of the different stakeholders involved in its development. It is important that studies use the same definition, as otherwise validity would be reduced. Therefore, future studies would benefit from the inclusion of more participants and from conducting a comparative study with another city of similar characteristics, which would allow us to extract perceptions and explore characteristics, other environments and cultures, deepening our understanding of the attitudes of these agents in other contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Data curation, L.C.-G.; Formal analysis, J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Investigation, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Methodology, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Project administration, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Resources, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Software, L.C.-G.; Supervision, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Writing—original draft, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G.; Writing—review & editing, M.H.A., J.G.-M. and L.C.-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research in this paper was funded by the project, “Overtourism in Spanish coastal destinations. Tourism degrowth strategies an approach from the social dimension.” (RTI2018–094844-B-C33) financed by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (National Plan for I+D+i), the Spanish State Research Agency, and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants for having dedicated their time, making it possible to carry out this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Block 1 Definition of Mass Tourism

Mass tourism in the city of Seville…

DEF 1 has been present.

DEF 2 is beneficial.

DEF 3 can help the tourism sector recover.

DEF 4 is sustainable.

Indicate according to your perception which definition or definitions would be the most consistent to define Mass Tourism

DEFINI 1 It is a quantitative concept associated with spatial concentration, which is why it is related to the carrying capacity of a territory.

DEFINI 2 It is the one that refers more to the impact on the local environment than to the number of tourists.

DEFINI 3 It is the one that relates to standardized and rigidly packed vacations.

DEFINI 4 It is one in which it is produced in a chain by a small number of companies that are not usually locally owned.

DEFINI 5 It is the one that generates a seasonal and concentrated tourism, mainly around the modality of sun and beach.

DEFINI 6 It is the one that offers inappropriate or minimal opportunities for contact and understanding between the hosts and the tourists or these contacts.

Blocks 2–3 Perceptions of Mass Tourism for Your Business

List the positive aspects of mass tourism for your business.

List the negative aspects of mass tourism for your business.

Indicate the positive aspects of mass tourism for the city of Seville.

Indicate the negative aspects of mass tourism for the city of Seville.

Sociodemographic

Please, now we need to know general information about your activity. Indicate the type of accommodation:

Hotel *

Hotel **

Hotel ***

Hotel ****

Hotel *****

Pensions

Tourist apartments

Hostels

How many years has this accommodation been in business for you?

More than 10

From 5 to 10

From 3 to 5

Recently opened (up to 3 years inclusive)

Select the district where your accommodation is located:

Alfalfa

Arenal

Encarnacion-Regina

fair

Museum

San Bartolome

San Gil

Saint Julian

San Lorenzo

Saint vincent

Santa Catalina

Santa Cruz

Appendix B. Word Code

| Word | Length | Count | Weighted Percentage (%) | Similar Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| work | 4 | 54 | 006 | bring, brings, employed, employment, going, influences, make, makes, run, work, works |

| job | 3 | 34 | 005 | business, businesses, job, jobs |

| city | 4 | 26 | 004 | city, municipality, Seville |

| none | 4 | 24 | 003 | none, no |

| economic | 8 | 20 | 003 | economic |

| economy | 7 | 20 | 003 | economy |

| tourism | 7 | 18 | 003 | tourism, tourists, tourist, |

| people | 6 | 15 | 002 | people |

| think | 5 | 15 | 002 | believe, consider, means, think |

| cultural | 8 | 12 | 002 | cultural, culture, cultures |

| increase | 8 | 12 | 002 | addition, increase, increased, increases, increasing, progress, progresses |

| many | 4 | 12 | 002 | many |

| generates | 9 | 14 | 002 | generate, generates, generation, get, give, gives, créate, creating |

| lot | 3 | 11 | 002 | lot, much, more |

| sector | 6 | 11 | 002 | sector, sectors field, fields |

| positive | 8 | 13 | 002 | favorable, place, positions, positive, positively, situation, good, well |

| created | 7 | 13 | 001 | create, created, creates, make, makes, produces |

| employment | 10 | 19 | 001 | employed, employment, useful, job, jobs |

| opportunities | 13 | 10 | 001 | opportunities, opportunity |

| benefits | 8 | 9 | 001 | benefit, benefiting, benefits |

| impact | 6 | 10 | 001 | affect, impact, impacts |

| beneficial | 10 | 11 | 001 | beneficial, good |

| creation | 8 | 9 | 001 | creation, exists, origins, world |

| greater | 7 | 8 | 001 | greater |

| income | 6 | 8 | 001 | Income, benefits |

| see | 3 | 12 | 001 | consider, find, finding, meet, meeting, see, visit |

| case | 4 | 8 | 001 | case, causes, example |

| new | 3 | 7 | 001 | new, young |

| activity | 8 | 7 | 001 | activated, activation, activity, alive |

| aspect | 6 | 6 | 001 | aspect, aspects |

| directly | 8 | 8 | 001 | directly, managed, now, place, ways |

| especially | 10 | 6 | 001 | especially |

| good | 4 | 11 | 001 | depend, depends, full, good, just |

| therefore | 9 | 6 | 001 | therefore, thus |

| high | 4 | 6 | 001 | high, richness, rich |

| wealth | 6 | 6 | 001 | richness, wealth |

| like | 4 | 5 | 001 | like, as |

| money | 5 | 5 | 001 | money |

| although | 8 | 5 | 001 | although |

| gives | 5 | 10 | 001 | contribution, give, gives, hand, leave, make, makes |

| atmosphere | 10 | 4 | 001 | atmosphere |

| contact | 7 | 6 | 001 | contact, meet, meeting |

| different | 9 | 4 | 001 | different |

| helps | 5 | 4 | 001 | help, helps |

| hospitality | 11 | 4 | 001 | hospitality |

| hotel | 5 | 4 | 001 | hotel, hotels |

| large | 5 | 4 | 001 | great, large |

| tourists | 8 | 4 | 001 | tourists |

| part | 4 | 6 | 001 | contribution, leave, part, share, starting |

| keeps | 5 | 5 | 001 | keeps, livelihood, living, observed, sustenance |

| depends | 7 | 5 | 001 | depend, depends, true |

| flow | 4 | 4 | 000 | flow, run |

| number | 6 | 4 | 000 | coming, number |

| areas | 5 | 3 | 000 | areas, countries, country |

| companies | 9 | 3 | 000 | companies, enterprise, enterprises, company |

| diversity | 9 | 3 | 000 | diversity |

| exchange | 8 | 3 | 000 | exchange, exchanges, exchanging |

| highlight | 9 | 3 | 000 | highlight |

| nothing | 7 | 3 | 000 | nothing |

| personally | 10 | 3 | 000 | personally |

| possibility | 11 | 3 | 000 | possibility |

| promote | 7 | 3 | 000 | promote |

| residents | 9 | 3 | 000 | resident, residents |

| seville | 7 | 3 | 000 | Seville, city, municipality |

| sometimes | 9 | 3 | 000 | sometimes |

| life | 4 | 4 | 000 | alive, life, living |

| local | 5 | 4 | 000 | local, place |

| offers | 6 | 3 | 000 | going, offers |

| find | 4 | 5 | 000 | find, finding, get, happens, observed |

| affect | 6 | 4 | 000 | affect, impressions, moves |

| also | 4 | 2 | 000 | also |

| better | 6 | 2 | 000 | better |

| citizens | 8 | 2 | 000 | citizens |

| environment | 11 | 2 | 000 | environment |

| etc | 3 | 2 | 000 | etc |

| even | 4 | 2 | 000 | even |

| farmers | 7 | 2 | 000 | farmers |

| friends | 7 | 2 | 000 | friends |

| indirectly | 10 | 2 | 000 | indirectly |

| industry | 8 | 2 | 000 | industry |

| leisure | 7 | 2 | 000 | leisure |

| main | 4 | 2 | 000 | main, principal, the most |

| miss | 4 | 2 | 000 | miss, want |

| multiculturalism | 16 | 2 | 000 | multiculturalism |

| negative | 8 | 2 | 000 | negative |

| options | 7 | 2 | 000 | options |

| power | 5 | 2 | 000 | power |

| precarious | 10 | 2 | 000 | precarious |

| purchasing | 10 | 2 | 000 | purchasing |

| related | 7 | 2 | 000 | related, associated |

| restaurant | 10 | 2 | 000 | restaurant, restaurants |

| thanks | 6 | 2 | 000 | thanks, thank, due to, because of |

| usually | 7 | 2 | 000 | usually |

| everything | 10 | 2 | 000 | everything, all |

| since | 5 | 2 | 000 | since |

| brings | 6 | 5 | 000 | bring, brings, contribution, get |

| causes | 6 | 6 | 000 | causes, get, make, makes |

| going | 5 | 6 | 000 | going, leave, living, moves, run, starting |

| become | 6 | 4 | 000 | become, coming, get, going |

| favorable | 9 | 2 | 000 | favorable, prefer |

| visit | 5 | 2 | 000 | visit, visitor |

| arrive | 6 | 3 | 000 | arrive, coming, get |

| family | 6 | 2 | 000 | family, home |

| home | 4 | 2 | 000 | home, international |

| important | 9 | 2 | 000 | important, means |

| place | 5 | 4 | 000 | home, place, situation |

| full | 4 | 3 | 000 | full, richness |

| leave | 5 | 2 | 000 | leave, results |

| know | 4 | 2 | 000 | know, living |

| living | 6 | 2 | 000 | living, population |

| able | 4 | 1 | 000 | able |

| accommodation | 13 | 1 | 000 | accommodation |

| added | 5 | 1 | 000 | added |

| agree | 5 | 1 | 000 | agree |

| airport | 7 | 1 | 000 | airport |

| alone | 5 | 1 | 000 | alone |

| always | 6 | 1 | 000 | always |

| arranged | 8 | 1 | 000 | arranged |

| back | 4 | 1 | 000 | back |

| beautiful | 9 | 1 | 000 | beautiful |

| certain | 7 | 1 | 000 | certain |

| commerce | 8 | 1 | 000 | commerce |

| council | 7 | 1 | 000 | council |

| daughter | 8 | 1 | 000 | daughter |

| end | 3 | 1 | 000 | end |

| entrepreneurs | 13 | 1 | 000 | entrepreneurs |

| fact | 4 | 1 | 000 | fact |

| fees | 4 | 1 | 000 | fees |

| financially | 11 | 1 | 000 | financially |

| flights | 7 | 1 | 000 | flights |

| forth | 5 | 1 | 000 | forth |

| happens | 7 | 2 | 000 | happens, occurs |

| happy | 5 | 1 | 000 | happy |

| inbred | 6 | 1 | 000 | inbred |

| indifferent | 11 | 1 | 000 | indifferent |

| infrastructures | 15 | 1 | 000 | infrastructures |

| internationalization | 20 | 1 | 000 | internationalization |

| known | 5 | 1 | 000 | known |

| language | 8 | 1 | 000 | language |

| little | 6 | 1 | 000 | little |

| livestock | 9 | 1 | 000 | livestock |

| long | 4 | 1 | 000 | long |

| monthly | 7 | 1 | 000 | monthly |

| neither | 7 | 1 | 000 | neither |

| nice | 4 | 1 | 000 | nice |

| obviously | 9 | 1 | 000 | obviously |

| one | 3 | 1 | 000 | one |

| opposite | 8 | 1 | 000 | opposite |

| others | 6 | 1 | 000 | others |

| partner | 7 | 1 | 000 | partner |

| prestige | 8 | 1 | 000 | prestige |

| raisin | 6 | 1 | 000 | raisin |

| ranchers | 8 | 1 | 000 | ranchers |

| really | 6 | 1 | 000 | really |

| relationship | 12 | 1 | 000 | relationship |

| reverts | 7 | 1 | 000 | reverts |

| sales | 5 | 1 | 000 | sales |

| saw | 3 | 1 | 000 | saw |

| son | 3 | 1 | 000 | son |

| specifically | 12 | 1 | 000 | specifically |

| springboard | 11 | 1 | 000 | springboard |

| suppliers | 9 | 1 | 000 | suppliers |

| taxes | 5 | 1 | 000 | taxes |

| terms | 5 | 1 | 000 | terms |

| third | 5 | 1 | 000 | third |

| town | 4 | 1 | 000 | town |

| traditional | 11 | 1 | 000 | traditional |

| value | 5 | 1 | 000 | value |

| varied | 6 | 1 | 000 | varied |

| yes | 3 | 1 | 000 | yes |

| among | 5 | 1 | 000 | among |

| anything | 8 | 1 | 000 | anything |

| everyone | 8 | 1 | 000 | everyone |

| sevillian | 9 | 1 | 000 | sevillian |

| something | 9 | 1 | 000 | something |

| get | 3 | 3 | 000 | get, produces, starting |

| means | 5 | 2 | 000 | means, ways |

| coming | 6 | 2 | 000 | coming, occurs |

| impressions | 11 | 2 | 000 | impressions, richness |

| origins | 7 | 2 | 000 | origins, starting |

| exists | 6 | 2 | 000 | exists, living |

References

- Benito, R.M. El turismo como sector estratégico en las etapas de crisis y desarrollo de la Economía Española. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2016, 2, 81–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, M.G. Turismo y medio ambiente en ciudades históricas. De la capacidad de acogida turística a la gestión de los flujos de visitantes. An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2000, 2000, 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.W. Tourism, environment, and sustainable development. Environ. Conserv. 1991, 18, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Akis, A. The effects of mass tourism: A case study from Manavgat (Antalya-Turkey). Proc. Soci. Behav. Sci. 2011, 19, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguló, E.; Catalina, S. Tourist expenditure for mass tourism markets. Anna. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 624–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D.; Debbage, K. Post-Fordism and flexibility: The travel industry polyglot. Tour. Manag. 1997, 18, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, F. Del Turismo de Masas al Turismo Masivo; Blog d’Economia i Empresa; 5 October 2015. Available online: https://economia-empresa.blogs.uoc.edu/es/del-turismo-de-masas-al-turismo-masivo/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic–A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, E.I. La Pandemia Como Oportunidad de Mejora en el Modelo Turístico; Blog Eco-Razon; 18 March 2021. Available online: https://eco-razon.es/la-pandemia-oportunidad-de-mejora-en-el-modelo-turistico/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Cruz, M.; Hortal, J.; Padilla, J. Vísteme despacio que tengo prisa. Un análisis ético de la vacuna del COVID-19: Fabricación, distribución y reticencia. Enrahonar. Int. J. Theor. Pract. Reason 2020, 65, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera García, J.; Pastor Ruíz, R. ¿Hacia un turismo más sostenible tras el COVID-19? Percepción de las agencias de viajes españolas. Gran Tour Rev. Investig. Turísticas 2020, 21, 206–229. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ayllon, S. Urban transformations as an indicator of unsustainability in the P2P mass tourism phenomenon: The Airbnb case in Spain through three case studies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, J.; Díaz-Parra, I. Gentrification, transnational gentrification and touristification in Seville, Spain. Urban Stud. 2020, 57, 3044–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, E. Todo el Año es ya Temporada Alta en Sevilla; ABC; 23rd January 2018. Available online: http://sevilla.abc.es/sevilla/sevi-todo-temporadaalta-sevilla-201801232335_noticia.html (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Díaz-Parra, I.; Jover, J. Overtourism, place alienation and the right to the city: Insights from the historic centre of Seville, Spain. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, M.; Jover, J. Paisajes de la turistificación: Una aproximación metodológica a través del caso de Sevilla. Cuad. Geográficos Univ. Granada 2021, 60, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Santos, E. La difícil convivencia entre paisaje urbano y turismo: Clasificación de conflictos y propuestas de regulación a partir del análisis comparativo de normativas locales. Boletín Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2018, 78, 180–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Vasco de Estadística. Definición de Establecimiento Hotelero. 2021. Available online: https://www.eustat.eus/documentos/opt_1/tema_141/elem_4814/definicion.html (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Pons, G.X.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Navalón-García, R.; Troitiño-Torralba, L.; Blázquez-Salom, M. Sostenibilidad Turística: Overtourism vs undertourism. Monogr. Soc. D’història Nat. Balear. 2020, 31, 1–146. [Google Scholar]

- Ivars, B. Tourism planning in Spain-evolution and perspectives. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, F. La política turística en España y Portugal. Cuad. Tur. 2012, 30, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Batle, J.; Garau-Vadell, J.B.; Orfila-Sintes, F. Are locals ready to cross a new frontier in tourism? Factors of experiential P2P orientation in tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.M. El turismo de masas: Un concepto problemático en la historia del siglo XX. Hist. Contemp. 2002, 25, 125–156. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, J.L.; Román, I.M.; Bonillo, D.; Paulova, N. El turismo a nivel mundial. Int. J. Sci. Manag. Tour. 2016, 2, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- UNTWO. Soluciones Para Devolver la Salud al Turismo. 2021. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/es/healing-solutions-tourism-challenge (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- UNTWO. 2020: El Peor Año de la Historia del Turismo, Con Millones Menos de Llegadas Internacionales. 2021. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2021-01/210128-barometer-es.pdf?afhE7NpuFgX_3avC5b8GTiE2T7Ptcw9J (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Bianchi, R.V.; de Man, F. Tourism, inclusive growth and decent work: A political economy critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croes, R.; Ridderstaat, J.; Bąk, M.; Zientara, P. Tourism specialization, economic growth, human development and transition economies: The case of Poland. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciutto, M.; Castellucci, D.I.; Roldán, N.G.; Cruz, G.; Corbo, Y.A.; Barbini, B. Reflexiones a propósito del turismo masivo y alternativo. Aportes para el abordaje local. Aportes Transf. 2020, 18, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- González, F. Del Turismo de Masas al Turismo masivo. Trib. Libre2015. Available online: https://economia-empresa.blogs.uoc.edu/es/del-turismo-de-masas-al-turismo-masivo/ (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Jenkins, C.L. Mass Tourism’is an Out-dated Concept—A Misnomer? Tour. Recreat. Res. 2007, 32, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, N. Mass Tourism: Benefits and Costs. In Tourism, Development and Growth: The Challenge of Sustainability; Pigram, J.J., Wahab, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Vainikka, V. Rethinking mass tourism. Tour. Stud. 2013, 13, 268–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Political trust and residents’ support for alternative and mass tourism: An improved structural model. Tour. Geograp. 2017, 19, 318–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R. Cancun´s tourism development from a Fordist spectrum of analysis. Tour. Stud. 2002, 2, 87–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, M. Turismo masivo y alternativo. Distinciones de la sociedad moderna/posmoderna. Convergencia 2010, 17, 235–260. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Dyer, P. Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of Sunshine Coast, Australia. J. Trav. Res. 2010, 49, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz Blas, S.; Buzova, D.; Garrigós Simón, F.J.; Narangajavana Kaosiri, Y. Implicaciones del turismo masivo en un destino de cruceros. In Proceedings of the INNODOCT/20, International Conference on Innovation, Documentation and Education, Valencia, Spain, 11–13 November 2021; Universitat Politècnica de València: València, Spain, 2021; pp. 757–763. [Google Scholar]

- Casillas Bueno, J.C.; Moreno Menéndez, A.M.; Oviedo García, M.D.L.Á. El turismo alternativo como un sistema integrado: Consideraciones sobre el caso andaluz. Estud. Turísticos 1995, 125, 53–75. [Google Scholar]

- Donaire, J.A. La reconstrucción de los espacios turísticos. La geografía del turismo después del fordismo. Soc. Territ. 1998, 28, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Theng, S.; Qiong, X.; Tatar, C. Mass tourism vs alternative tourism? Challenges and new positionings. Études Caribéennes 2015, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantero, J.C. Urbanizaciones turísticas del litoral atlántico. Aportes Transf. 2001, 5, 11–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bramwell, B. Mass tourism, diversification and sustainability in Southern Europe’s coastal regions. In Coastal Mass Tourism: Diversification and Sustainable Development in Southern Europe; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2004; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hittmair, A.M. Gefahren des Massentourismus und Tourismusforschung aus volks-gesundheitlicher Sicht. Internist 1971, 12, 266–268. [Google Scholar]

- Bellan, G.; Pérès, J.M. La pollution dans le bassin méditerranéen (quelques aspects en Méditerranée nord-occidentale et en Haute-Adriatique: Leurs enseignements). In Marine Pollution and Sea Life; Ruibo, M., Ed.; Fishing News Ltd.: Surrey, UK; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1972; pp. 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, P. Mass tourism—From the medical viewpoint. Orvosi Hetilap 1972, 113, 2117–2118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Velimirovic, B. Mass travel and health problems (with particular reference to Asia and the Pacific Region). J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1973, 76, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goldsmith, E. Pollution by tourism. Ecologist 1974, 48, 47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Guntern, G. Social change and mental health. The change of a mountain village in the Alps from an agricultural community to tourist attraction. Psychiatr. Clin. 1974, 7, 287–313. [Google Scholar]

- Mantero, J.G.; Barbini, B.; Bertoni, M. Turistas y Residentes en Destinos de Sol y Playa. Gestión Turística 1999, 4, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brida, J.G.; Pereyra, J.S.; Devesa, M.J.S.; Aguirre, S.Z. La contribución del turismo al crecimiento económico. Cuad. Tur. 2008, 22, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hutsaliuk, O.; Smutchak, Z.; Sytnyk, O.; Krasnozhon, N.; Puhachenko, O.; Zarubina, A. Mass labour migration in the vector of international tourism a determinant sign of modern globalization. Rev. Tur. Estud. Práticas 2020, 3, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, B.; Cooper, C.; Ruhanen, L. The positive and negative impacts of tourism. In Global Tourism; Theobald, W.F., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd.: Boston, MA, USA, 2005; Chapter 5; pp. 79–102. [Google Scholar]

- Almirón, A.; Bertoncello, R.; Troncoso, C.A. Turismo, patrimonio y territorio: Una discusión de sus relaciones a partir de casos de Argentina. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2006, 15, 101–124. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.; Barretto, M. Los cambios socioculturales y el turismo rural: El caso de una posada familiar. Rev. Pasos 2007, 5, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Palazuelo, F.P. Sostenibilidad y turismo, una simbiosis imprescindible. Estud. Turísticos 2007, 172, 13–62. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenkel, E. Turismo y política turística. Un análisis teórico desde la ciencia política. Rev. Reflex. 2019, 98, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolasco Cirugeda, A.; Martí, P.; Ponce, G. Keeping mass tourism destinations sustainable via urban design: The case of Benidorm. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1289–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, R.; Catalán, S.; Pina, J.M. Understanding How Customers Engage with Social Tourism Websites. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021. Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1757-9880.htm (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- Royo, M.; Ruiz, M.E. Actitud del residente hacia el turismo y el visitante: Factores determinantes en el turismo y excursionismo rural-cultural. Cuad. Tur. 2009, 23, 217–236. Available online: https://revistas.um.es/turismo/article/view/70111 (accessed on 28 March 2021).

- González, M.; Iglesias, G. Impactos del turismo sobre los procesos de cohesión social y las políticas mitigantes para el caso de Caibarién-Cuba. Estud. Perspect. Tur. 2009, 18, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson, A.; Wall, G. Tourism, Economic, Physical and Social Impacts; Longman: London, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, G. (Ed.) Cultural Attractions and European Tourism; Cabi: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy, D.; Jurowski, C.; Uysal, M. Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2002, 29, 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, E. El turismo residenciado y sus efectos en los destinos turísticos. Estud. Turísticos 2003, 2003, 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Percepciones de los residentes sobre los impactos del turismo comunitario. An. Investig. Turística 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Mathieson, A. Tourism: Change, Impacts, and Opportunities; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Picornell, C. Los impactos del turismo. Pap. Tur. 2015, 11, 65–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kroes, R. Present-Day Mass Tourism: Its Imaginaries and Nightmare Scenarios. Society 2020, 57, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranwa, R. Impact of tourism on intangible culture heritage: Case of Kalbeliyas from Rajasthan, India. J. Tour. Cult. Chan. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhanvar, A.; Jenkins, G.P. Impact of foreign direct investment and international tourism on long-run economic growth of Estonia. J. Econ. Stud. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.A.; Fallon Scura, L.; van’t Hof, T. Meeting ecological and economic goals: Marine parks in the Caribbean. Ambio 1993, 22, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.M. Tourism development and dependency theory: Mass tourism vs. ecotourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 988–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F.; Lime, D.W. Tourism carrying capacity: Tempting fantasy or useful reality? J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A.; Beeton, R.J.; Pearson, L. Sustainable tourism: An overview of the concept and its position in relation to conceptualisations of tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2002, 10, 475–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.H.; Twining-Ward, L. Reconceptualizing tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Peeters, P.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G.; Patterson, T.; Richardson, R.B. La ecoeficiencia del turismo. Econ. Ecológica 2005, 54, 417–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]