Abstract

The use of instruments for the evaluation of a player’s procedural tactical knowledge (PTK) in sociomotor sports, such as football, is a line of research of growing interest since it allows a pertinent description of the player’s football competence. The aim of this study is to configure and validate an ad-hoc observational tool that allows evaluating the player’s PTK, understood as football competence, from the observation, coding and recording of the roles, the actions of the acquired subroles and the operational and specific principles of football in the attack and defense phases. Based on the Delphi method, a field format coding instrument was designed and validated where each criterion is a system of categories, exhaustive and mutually exclusive. The results showed excellent content validity (9.02 out of 10), and high values of intra-observer stability (k = 0.747) and inter-observer agreement (k = 0.665). Generalizability analysis showed an excellent reliability (G = 0.99). Additionally, the construct validity of the tool was calculated through a small-sided game Gk + 4v4 + Gk, using two independent samples: semi-professional and amateur players. The results reflected significant differences (α < 0.05) between both samples in the variables total score, offensive score and defensive score. Therefore, this study provides a valid and reliable instrument that allows data collection in a rigorous and pertinent way, as well as their analysis and evaluation in attack and defense according to the roles of the players and based on the motor behaviors that they perform using the subroles that they acquired, associated with the technical dimension, along with the principles that they develop in parallel, in support of the tactical dimension.

1. Introduction

The construction of instruments for the evaluation of the tactical knowledge of the players in sociomotor sports [1], as is the case of football, is a line of research of increasing interest due to the importance that tactic dimension assumes in training and performance [2]. In this sense, the instruments proposed for the tactical evaluation of the player have been developed and classified into two perspectives according to the type of tactical knowledge that has been evaluated. One perspective refers to declarative tactical knowledge (DTK), that is, “knowing what to do”, through knowledge of the rules, positions, functions, offensive and defensive strategies, and understanding of the technical-tactical logic of the game [3]. The perspective of the procedural tactical knowledge (PTK) is intimately linked to the particular motor action [4,5,6], that is, “to know how to do”. The latter, the tactical dimension of behavior, is decisive in a sport like football, with a very complex logic due to its high unpredictability and randomness of events [7], and refers to the player’s performance in the context of the game [8] or to football competence [9].

To analyze and assess the behaviors of the players, several methods have been used, as can be observed in systematic reviews on match analysis carried out in soccer [10] and other team sports [11,12,13,14]. From the observational methodology [15], there is a wide variety of instruments to assess PTK in football, such as “Performance Assessment in Team Sports” (TSAP) [16], “Game Performance Assessment Instrument” (GPAI) [17], “Procedural Tactical Knowledge Test” (KORA) [18], validated by Memmert [19], “System of Tactical Assessment in Soccer” (FUT-SAT) [20], “Game Performance Evaluation Tool” (GPET) [21] and “Instrument for the Measurement of Learning and Performance in Football” (IMLPFoot) [22]. These tools are articulated around the tactical variables or game principles [23] that each author takes into consideration, resulting in very different configurations, and reflecting the difficulty that exists when evaluating the motor behaviors that are developed by the players in the collective games [24].

The most important limitations of these tools are as follows: focusing only on the attack phase (TSAP, KORA, GPET), or solely on the evaluation of the player with the ball (TSAP); not covering all the possibilities that the player has to respond in every situation (TSAP, KORA, GPAI, GPET, IMLPFoot); not using game principles to classify the behaviors carried out by the player (TSAP, GPAI, KORA, IMLPFoot); resorting to game principles, without analyzing the tactical behaviors that the player displays (FUT-SAT). It can be said that no tool offers a complete coding system around the roles and subroles of the football player, which allows the deployment and analysis of motor behavior based on these, leading to a relevant evaluation of the player’s football competence.

Taking into account the limitations presented by the tools shown, it is interesting to note that the dual structure of sociomotor games leads to understand that the sociomotor roles that the participant can assume can be different when attacking and defending [25]. Taking as a reference the concept of “game center” [26], different roles can be identified depending on the relationship of closeness between ball and player [27]. However, this level of specification does not seem sufficient to allow a rigorous and detailed analysis of the game action, for which it is necessary to go to the subroles associated with each of the player’s roles. Some studies [28,29] have delved into the study of motor behaviors in football through the use of sociomotor subroles, allowing to appreciate, in the case of each player, the particular orientation they make of their role [30] and the consequent possibilities of action. The possibilities of action of the players can be framed within the game principles. The current literature includes various types of game principles: operational principles [31], fundamental principles [32,33] and specific principles [5,32,33,34,35,36,37], in addition to the principles associated with the game model to be transmitted, linked to a certain way of playing. They can all can facilitate the framing of tactical behaviors shown by teams and players, contributing to the design of instruments that reflect with greater specificity and superior relevance the events that happen in a match or training [38,39].

Given all of the above, the objective of this study is to configure and validate an observation tool designed ad-hoc to evaluate a player’s PTK, understood as football competence, based on the observation, coding and recording of the roles, the own actions of acquired subroles and the principles adopted by the players in the game. To achieve this objective, guaranteeing the validity and reliability of the data collected is important so that the performance analysis can effectively fulfill its intentions and purposes [40]. For this, it seems necessary to determine the degree of validity and reliability of ad-hoc tools from various dimensions. This is, on the one hand, the content, construct and criterion validity [41], and on the other hand, the stability and agreement of the instrument, based on its intra-observer and inter-observer reliability. The results of the present study allow the applicability of the instrument not only in the scientific field, but also in the field of evaluation of pedagogy and sports training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

The study responds to an observational design that is punctual, idiographic and multidimensional [42]. It is idiographic because it is focused on a study unit, the player in particular; it is punctual because the data collection is carried out in a single session, and not throughout a season; and it is multidimensional, because the effectiveness index of the tactical behaviors displayed by the player is studied based on various criteria. Therefore, for data collection, it is necessary to configure an ad-hoc instrument, which, conditioned by the structure of the observational design, will be a field format coding instrument where each criterion is a system of categories, exhaustive and mutually exclusive [43]. For all this, the data type is sequential and event-based, since the observer collects the order of events, not their duration, and only one behavior can take place at a time [44].

2.2. Participants

During the design and reconfiguration stages of the instrument that gave way to its validation, a total of 31 experts contributed their conclusions via “Google Forms” in three different phases (n = 6, n = 8, n = 17). Experts had to meet at least two of the following three requirements: (1) have more than 10 years of experience training, (2) be graduates in physical activity and sports sciences with a specialty in football, (3) and be active coaches with a minimum qualification of professional level.

To establish the construct validity of FOCOS, two similar small-sided games (SSG) Gk + 4v4 + Gk were recorded and analyzed using two independent samples: eight semi-professional players (21.68 ± 1.38 years old), who were active in Spanish Second Division B playing in the reserve team of a “La Liga” club, and eight amateur players from a club of the last category of federated football in Madrid (25.30 ± 2.15 years old). Goalkeepers were not considered in any of the samples. In addition, for the reliability process, two observers were trained in the use of the tool, joining the experimenter, who acted as the third observer.

2.3. Coding Instrument

The Football Competence Observation System, FOCOS, was developed taking as reference various studies around the classifications of operational [31] and specific principles [5,32,33,34,35,36,37] as well as the roles [27] and subroles [28,29]. The new tool is formed by the combination of a field format and exhaustive and mutually exclusive category systems, based on six criteria (phase, role, own action of the subrole, operational principle, specific principle and result of the action) that appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria and category systems of the Football Competence Observation System (FOCOS).

Taking the observation system proposed, the observer analyzes the volume and effectiveness of the behaviors that the player is displaying based on the criteria described. For this, the observer must know in detail the definitions of the categories (see Table 2). Volume and effectiveness are two performance indicators that have also been used in TSAP [16].

Table 2.

Codes and definitions of observation categories.

2.4. Procedure

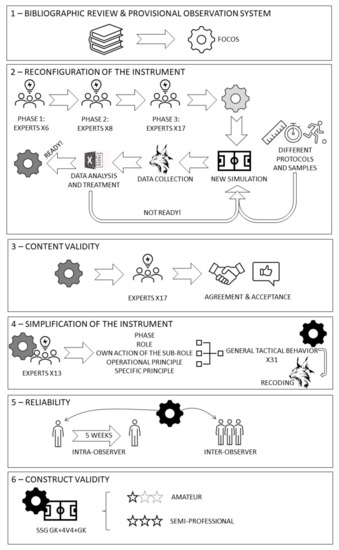

The instrument design, the validity and reliability processes were carried out in six stages (see Figure 1) following the procedures used in other recent observational tools [22,45,46]: (a) bibliographic review and provisional design of the tool observation system, (b) consultation with experts, reconfiguration of the tool observation system and choice of reference formats for the game protocol, (c) content validation of the coding instrument, (d) simplification of the coding instrument and validation of this process, (e) development of intra-observer and inter-observer reliability processes in addition to generalizability analysis and (f) calculation of construct validity. Finally, the quality of this process was assessed using the methodological quality checklist for studies based on observational methodology (MQCOM) [47].

Figure 1.

Stages for the design and validation of FOCOS.

In the first stage, the provisional selection of the criteria and observation categories that make up the tool was carried out through a bibliographic review of the main evaluation tools of the PTK [16,17,18,20,21], as well as studies and observation tools designed from the football player’s subroles [28,29].

In the second stage, the observation system was gradually modified after consultation with experts. Using a Likert scale of 1–10, they were asked about: (a) degree of agreement, regarding clarity of language in the definition of the criteria and categories of the tool; (b) degree of importance and adequacy, based on practical and theoretical relevance, when the criterion or category to evaluate was part of the tool; (c) considerations, comments and observations about each criterion and categories of the tool. In this way, the criteria and categories were reconfigured, shaping the observation system of the tool and subjecting it to a new expert judgment, until passing the validation process in the third phase.

Parallel to this process, and taking the observation system proposed, an ad-hoc observational tool was designed for the coding and data collection process using the “LINCE software” [48]. Subsequently, templates were designed using Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft Corporation, Washington, USA) for the analysis and treatment of the data obtained, which would also be adapted during the process until obtaining the final version. From the observation tool, several simulations were performed and codified using different protocols and players to identify possible aspects to improve, which could be added to the experts’ judgment.

The choice of the reference formats that would serve as a protocol for the analysis of the PTK of the players tried to respond both to 7-football (for players U12), and to 11-football (from U13). For this, the player’s theoretical individual space of interaction was considered; that is, 300 m2 for 11-football and 200 m2 for 7-football [49]. These values served as a reference for the construction of the protocols considering the age of the players to be analyzed. Two protocols, based on SSG Gk + 4v4 + Gk, were established according to the football modality. As a result of this, easily identifiable spaces were established within the playing field, as well as playing times, in order to minimize the effect of fatigue during the protocol, establishing the following game formats that would serve as a reference for its realization (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Reference formats for carrying out the protocol.

In the third stage, the content validity of the instrument was established from the last group of experts (n = 17) through the Content Validity Coefficient (CVC) [50]. Once the opinion of this last group of experts was obtained, the categories of the observational system with average values < 0.70, in terms of degree of agreement or degree of acceptance, were eliminated (n = 0); the categories with values between 0.70 and 0.80 were reformulated following the proposals of the experts (n = 1) and the categories with average values greater than 0.8 were accepted (n = 36) [51]. In this sense, practically all the categories had average values above 0.80 since the tool had undergone a rigorous configuration process before reaching this point. However, based on the considerations provided by the experts, a new category was included within the criterion result of the action (category = improvable). Football is a sport of maximum uncertainty, where unrepeatable behaviors occur. This new category seems important, when the observer cannot identify with certainty whether the behavior performed by the player is successful or not.

In the fourth stage, to simplify the instrument and increase its agility, the number of criteria in the analysis tool was reduced to two, unifying the phase, role, own action of the subrole, operational principle and specific principle in a single criterion called “general tactical behavior”, and maintaining the criterion “result of the action”. To carry out this process, the networks of mutually compatible categories were validated, discarding those combinations that were impossible in the game (examples: an attacker without the ball could never make a pass, or a defender could never perform the specific principle of penetration). Once this was complete, the 315 combinations of categories of the criteria in attack and the 180 combinations in defense were presented to a last group of experts (n = 13). The experts had to show their degree of agreement and acceptance through a Likert 1–10 scale with those combinations proposed as compatible by the experimenter, propose new compatible combinations if any, and accept or reformulate the general tactical behavior name proposed for each one. From this process, combinations with values below 8 out of 10 should be discarded or reformulated following the contributions and comments of the experts [50]. In the case of the tool, a combination that did not reach the predetermined values was discarded, a new one was approved and 11 general tactical behaviors’ names were reformulated after consultation with experts, even though all of them had exceeded the predetermined values. After this process, 21 attack and 10 defense combinations were proposed as compatible, providing an identifying name for each in the form of general tactical behavior. Table 4 shows the network of combinations described.

Table 4.

General tactical behaviors in the network of compatible category combinations in attack and defense.

After the observational system was validated, the observation tool was codified again, this time using the new “LINCE PLUS software” [52].

In the fifth stage, the inter-and intra-observer reliability process were performed. For this, the procedures developed in other works were followed [53,54,55,56]. First, the conceptual and registration protocol for motor behaviors was developed. Secondly, two observers were trained according to said protocol, and carried out the analysis of a determined player independently, who was previously analyzed by the experimenter. Third, inter-observer reliability was calculated, and the behaviors analyzed as different between observers were discussed and re-analyzed. Five weeks later, through the test-retest reliability method, an observer repeated the analysis process and the results obtained were compared with their previous analysis to calculate intra-observation reliability. Given the nature of the data analyzed and to control their quality, the TG (Generalizability Theory) [57] was applied from the modeling of the different sources of variability or facets (e.g., observers and categories of the taxonomic system), designing two possible models: Categories:Observers [C:O] and Observers:Categories [O:C].

Finally, in the sixth stage, once a high content validity for the instrument was obtained and the reliability processes were overcome, the construct validity of the instrument was calculated, in its perspective of discriminant validity, to measure the degree of the instrument to distinguish between groups of players that are expected to be different [58].

2.5. Application

After using FOCOS to carry out the PTK analysis of the players taking part in the selected protocol, the data obtained from each player were transferred to Excel templates designed ad-hoc to obtain the resulting scores and to perform the consequent evaluation. In these templates, data processing is performed to obtain the volume and the effectiveness index of each variable within the criteria studied. Volume is understood as the number of times the player develops tactical behaviors in which each category is involved, while the effectiveness index is represented by the volume of successful tactical behaviors divided by the number of tactical behaviors deployed by the player in the category of analysis studied.

Once the effectiveness indices have been obtained for each category, the offensive and defensive effectiveness indices are calculated, as well as a global effectiveness index. This global effectiveness index represents the player’s PTK level. In short, general scores are obtained for these last three mentioned variables, together with the specific scores of the variables that represent the categories of the role criteria, own action of the subrole and operational and specific principle of the FOCOS. All these specific scores are also compared with the average scores of all the analyzed players, allowing the determination of the player’s PTK level in each variable with respect to the teammates in their group. In addition, the scores of the variables are shown in the form of general tactical behaviors in game-play situations in which the player has developed them.

2.6. Data Analysis

The coding instrument has been evaluated in relation to the quality of the data required of any observational research that purports to be scientific [59]. To do this, the content validity of the instrument has been approached qualitatively, through consensual agreement [60] of a group of experts, through the Delphi method and using the content validity coefficient [50]. It has also been analyzed quantitatively, by calculating intra-observer reliability, using Cohen’s kappa; and inter-observer reliability, using the fleiss kappa index. Furthermore, the construct validity has been calculated using Student’s t-test for independent samples.

3. Results

The verification of the quality of the observational data allows for subsequent objective studies, and in this way, the adoption of original strategies for their application in training [59]. The results are described in the following sections.

3.1. Content Validity of the FOCOS

To calculate the Content Validity Coefficient [50], the averages of the two factors used with the expert groups were calculated, following the Delphi methodology: the degree of agreement (8.74 out of 10) which reflects the clarity of the language (to what extent do you consider the definition to be well developed and exclusive with respect to the other categories of the criterion?), and the degree of adequacy (9.3 out of 10) which represents practical and theoretical relevance (to what extent do you consider that the category should be part of the criterion?). From these two factors, the total content validity of the tool was obtained (9.02 out of 10), concluding that it is a very high validity. In the same way, the criterion “General tactical behavior” was also validated. In this process, the global content validity was also very high (9.4 out of 10).

3.2. Construct Validity of the FOCOS

The construct validity of the instrument was calculated, in its perspective of discriminant validity, to measure the degree of the instrument to distinguish between groups of players that are expected to be different [58]. Using the reference formats, the protocol was carried out with two independent samples. Although all variables were analyzed, the overall total score, the total offensive score and the total defensive score obtained by semi-professional players were compared with the scores obtained by amateur players, since they reflect a more global vision of the players’ football competence. The data were analyzed using the Student’s t-test for independent samples and the results showed significant differences (α < 0.05) between both groups in these three variables (see Table 5). Cohen’s d-effect size [61] was also calculated to assess the magnitude of the difference between both groups. Differences based on effect size are referred to descriptively as very large (d ≥ 2), large (2.0 > d ≥ 1.2), moderate (1.2 > d ≥ 0.6), small (0.6 > d ≥ 0.2) and trivial (0.2 > d ≥ 0). [62] The results showed values between 1.08 and 2.32, except for one variable that showed significant differences in favor of the amateur group.

Table 5.

Differences between semi-professional football players and amateur football players.

3.3. Intra-Observer Reliability

To calculate the intra-observer stability index, test-retest reliability was used by applying Cohen’s kappa to the data extracted from the observation of a player with a difference of five weeks between both records. In relation to the records made, it should be clarified that some error of omission in the record of any category may cause a mismatch between records, causing a possible underestimation of the concordance coefficient [63]. To avoid this, and before proceeding to calculate the Cohen’s kappa index, a filter was developed manually, matching those identifiable behaviors through their temporal registration. Once this process had been carried out, the results showed an agreement index of 0.747, which could be valued as good [64] regarding an observational tool with these characteristics.

3.4. Inter-Observer Reliability

The inter-observer reliability of FOCOS was calculated following the same manual filtering process that was used in the intra-observer reliability calculation. To calculate the inter-observer concordance coefficient for more than two observers (n = 3), Fleiss kappa was applied. The values obtained (k = 0.766) showed a good agreement.

3.5. Generalizability Analysis

The generalizability analysis was carried out in the SAGT v1.0 build 218.0.1 software program [65], using two possible models: Categories/Observers and Observers/Categories (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Estimated values of the relative coefficients (ξρ2(δ)) and absolute (ξρ2(Δ)) of generalizability for the designs Categories:Observers [C:O] and Observers:Categories [O:C].

The [C:O] design was used to calculate the inter-observer reliability. The relative generalizability coefficient is associated with high reliability in the generalization precision of the results (close to 1). To assess construct validity, the [O:C] design was used. The generalizability coefficients were found to be close to 0 (for both coefficients, relative and absolute). The possible sources of variance showed that most of the variability (100%) was associated with the categories facet, being null in the rest of the facets: Observers (0%), and Observers:Categories (0%). This reveals that the established categories are heterogeneous and, therefore, exclusive within the configured taxonomic system.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study is to describe the steps carried out to design and assess the validity and reliability of a new proposal of an ad-hoc observational tool. The developed instrument allows us to analyze and evaluate the player’s PTK, both in attack and defense, unlike other tools such as GPET [21] and KORA [18] which focus only on the offensive phase, or TSAP [16] which exclusively analyzes the player when he has the ball.

Based on the record of the motor behaviors developed by the player, FOCOS allows evaluating their performance based on several criteria: the roles, the own actions of the acquired subroles, the operational principles and the specific principles. In this sense, the complete analysis of the behaviors that the player can develop during his performance is another advantage of FOCOS compared to other tools. FUT-SAT [20] does not evaluate the behaviors displayed by the player, and although TSAP [16], GPAI [17], KORA [18], GPET [21] and IMLPFoot [22] evaluate certain behaviors, they do not cover all the possibilities that the player has to respond to any game-play situation. Furthermore, the use of sociomotor roles and subroles to classify tactical behaviors is another contribution of the tool, allowing a more rigorous analysis. In addition, the evaluation of both operating principles and specific principles represents a great advantage over other tools such as FUT-SAT [20] which is focused only on specific principles, GPET [21] which analyzes operational principles, or TSAP [16], GPAI [17], KORA [18] and IMLPFoot [22] which are not articulated around game principles.

Another advantage of the tool is its protocol because it has a sustainable and easily applicable game format. FOCOS uses a SSG Gk + 4v4 + GK in football double area (for U13 players or older) or half football field-7 (for U12 players). Regarding this fact, different game formats are used in other tools: 3v3 without goals in KORA [18], Gk + 3v3 + Gk in FUT-SAT [20] and IMLPFoot [22]; Gk + 5v5 + Gk in GPAI [17], and from 2v2 to 7v7, in GPET [21] according to the age of the players. The use of SSGs that guarantee the representativeness [66] of the football game seems to be something on which most of the authors agree. In this study, Gk + 4v4 + Gk has been used because it is a game format that facilitates the occupation of the entire space in depth and width. Spaces of greater width than length have been used, since the interaction contexts [63] generated by the teams during a match usually have this characteristic, and the SSGs have the particularity of facilitating that all the players participate actively due to their proximity to the game center.

For everything mentioned, it is understood that the knowledge of the strengths and weaknesses of each player by the coach or coaching staff can be used to optimize the teaching-training processes from the subroles (divergent learning) or principles (convergent learning). The subroles represent, in one way or another, the most applicable version of the player’s technique in the tactical context that is presented, and they are related to exploratory capacity, while the principles are closely linked to learning a set of action rules common to any game model within the tactical framework that presents football as a sociomotor sport.

Respecting the applicability of the instrument, several possibilities can be found: (1) within a team, the player’s football competence could be periodically analyzed, allowing to evaluate his evolution compared to himself and his teammates; (2) also, the level of football competence of new players who train with a team on a trial basis could be assessed; (3) in recruitment days, those players who show an adequate level of football competence in the eyes of coaches and scouts could be evaluated in detail, in order to identify possible sports talents; (4) could also be used to complement the analysis performed using positional data tools. Considering this fact, the positional data focuses on the team, analyzing variables such as team length, team width and team surface area [67], while FOCOS is focused on the player, analyzing aspects already mentioned that are conceptually closer to those managed by coaches.

Regarding the limitations of this study, it can be noted that it was decided not to calculate the criterion validity of the tool, understood as concurrent or concomitant validity; that is, the degree of correlation between two measures of the same concept, at the same time and in the same subjects [68]. For this, FOCOS would have to be compared with an external criterion that intended to measure the same, but there are no tools in the scientific literature with the level of depth that FOCOS presents. This level of complexity implies several limitations: the deep knowledge of the tool and the game to be able to use it, the large volume of information that is handled, the temporary and human resources for its use on a large scale, as well the impossibility of applying it in real time.

5. Conclusions

As conclusions of the study, it should be mentioned that the coding instrument presented shows optimal validity and reliability values. It is the first instrument collected in the scientific literature, which is structured interactively based on the roles, the actions of the subroles, the operational principles and the specific principles of the game of football. It can fully analyze, both in attack and defense phases, the player’s procedural tactical knowledge, understood as football competence. It is able to analyze and evaluate the player in detail from a technical-tactical point of view, based on the motor behaviors that he performs using the subroles that he acquired, associated with the technical, and the principles that he develops in parallel, in support of the tactical dimension. This aspect represents something pioneering within the range of observational instruments directed towards the analysis of the player’s PTK. Based on these conclusions, the instrument could be used for scientific purposes to carry out possible research projects or specific studies, as well as by clubs, performance analysis departments and coaches to analyze and evaluate their players in detail, and thus improve their teaching and training processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S.-L., I.E. and J.C.; methodology, R.S.-L., I.E. and J.C.; validation, R.S.-L.; formal analysis, R.S.-L., I.E. and J.C.; investigation, R.S.-L.; data curation, R.S.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S.-L.; writing—review and editing, R.S.-L., I.E. and J.C.; visualization, R.S.-L.; supervision, I.E. and J.C.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of a Spanish government subproject Mixed method approach on performance analysis (in training and competition) in elite and academy sport [PGC2018-098742-B-C33] (2019-2021) [del Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (MCIU), la Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI) y el Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER)], that is part of the coordinated project New approach of research in physical activity and sport from mixed methods perspective (NARPAS_MM) [SPGC201800X098742CV0].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Organic Law 15/1999 of 13th December on the protection of personal data (BOE, 298, 14th December 1999) in order to guarantee the ethical considerations of scientific research with human subjects. Ethical approval was waived for this study because no invasive measures were performed to obtain the data.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Parlebas, P. Elementos de Sociología Del Deporte; Unisport Andalucía: Málaga, Spain, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Teoldo, I.; Guilherme, J.; Garganta, J. Training Football for Smart Playing: On Tactical Performance of Teams and Players; Appris: Curitiba, Brazil, 2015; p. 319. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.R.; French, K.E.; Humphries, C.A. Knowledge Development and Sport Skill Performance: Directions for Motor Behavior Research. J. Sport Psychol. 1986, 8, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkhart, M.W. The Nature of Declarative and Nondeclarative Knowledge for Implicit and Explicit Learning. J. Gen. Psychol. 2001, 128, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoldo, I.; Garganta, J.; Greco, P.J.; Mesquita, I. Proposta de Avaliação Do Comportamento Tático de Jogadores de Futebol Baseada Em Princípios Fundamentais Do Jogo. Mot. Rev. Educ. Física 2011, 17, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Davids, K. Declarative Knowledge in Sport: A by-Product of Experience or a Characteristic of Expertise? J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 1995, 17, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garganta, J. Modelação Táctica Do Jogo de Futebol: Estudo Da Organização Da Fase Ofensiva Em Equipas de Alto Rendimento; University of Porto: Porto, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- French, K.E.; Thomas, J.R. The Relation of Knowledge Development to Children’s Basketball Performance. J. Sport Psychol. 1987, 9, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlebas, P. Une Pédagogie Des Compétences Motrices. Acción Motriz. 2018, 20, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmento, H.; Marcelino, R.; Anguera, M.T.; CampaniÇo, J.; Matos, N.; LeitÃo, J.C. Match Analysis in Football: A Systematic Review. J. Sports Sci. 2014, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, W.R.; Sarmento, H.; Vaz, V. Match Analysis in Handball: A Systematic Review. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 2019, 8, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agras, H.; Ferragut, C.; Abraldes, J.A. Match Analysis in Futsal: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport. 2016, 16, 652–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Marcelino, R.; Lacerda, D.; João, P.V. Match Analysis in Volleyball: A Systematic Review. Montenegrin J. Sports Sci. Med. 2016, 5, 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; McRobert, A.P.; Toro, E.O.; Vélez, D.C. Collective Behaviour in Basketball: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2017, 17, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M.T. Metodología de La Observación En Las Las Ciencias Humanas; Catedra: Madrid, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gréhaigne, J.-F.; Godbout, P.; Bouthier, D. Performance Assessment in Team Sports. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1997, 16, 500–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oslin, J.L.; Mitchell, S.A.; Griffin, L.L. The Game Performance Assessment Instrument (GPAI): Development and Preliminary Validation. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 1998, 17, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, C.; Roth, K. Escola Da Bola: Um ABC Para Iniciantes Nos Jogos Esportivos [School Ball: An ABC Sports Games for Beginners]; Phorte: Sao Paulo, Brazil, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Memmert, D. Diagnostik Taktischer Leistungskomponenten: Spieltestsituationen Und Konzeptorientierte Expertenratings [Tactical Performance Components Valuation: Test Situations and Concept-Oriented Expert Ratings]. Ph.D. Thesis, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Teoldo, I.; Garganta, J.; Greco, P.J.; Mesquita, I.; Maia, J. Sistema de Avaliação Táctica No Futebol (FUT-SAT): Desenvolvimento e Validação Preliminar. /System of Tactical Assessment in Soccer (FUT-SAT): Development and Preliminary Validation. Motricidade 2011, 7, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- García-López, L.M.; González-Víllora, S.; Gutiérrez-Díaz, D.; Serra-Olivares, J. Development and Validation of the Game Performance Evaluation Tool (GPET) in Soccer. Sport Rev. Euroam. Cienc. Deporte 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ceberino, J.M.; Antúnez, A.; Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S. Design and Validation of the Instrument for the Measurement of Learning and Performance in Football. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020, 17, 4629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Víllora, S.; Serra-Olivares, J.; Pastor-Vicedo, J.C.; Teoldo, I. Review of the Tactical Evaluation Tools for Youth Players, Assessing the Tactics in Team Sports: Football. SpringerPlus 2015, 4, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugas, E. L’avaluació de Les Conductes Motrius En Els Jocs Col· Lectius: Presentació d’un Instrument Científic Aplicat a l’educació Física. Apunt. Educ. Física Deportes. 2006, 1, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Moreno, J. Análisis de Las Estructuras Del Juego Deportivo; INDE: Barcelona, Spain, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Castelo, J. Futebol. Modelo Técnico-Táctico Do Jogo; Edições FMH: Lisboa, Portugal, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lago, C. La Acción Motriz En Los Deportes de Equipo de Espacio Común y Participación Simultánea. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de A Coruña, Galicia, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Obœuf, A.; Collard, L.; Pruvost, A.; Lech, A. La Prévisibilité Au Service de l’impré Visibilité. À La Recherche Du «code Secret» Du Football. Reseaux 2009, 156, 241–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marqués, D.; de Santos, R.M.; Gorostiaga, D.S. Data Quality Control of an Observational Tool to Analyze Football Semiotricity. Cuad. Psicol. Deport. 2015, 15, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasierra, G. Análisis de La Interacción Motriz En Los Deportes de Equipo. Aplicación de Los Universales Ludomotores Al Balonmano. Apunt. Educ. Física Deportes. 1993, 32, 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, C. L´ensegnement Des. Jeux Sportifs Collectifs; Vigot. Edc: Paris, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz, O. Para Uma Teoria Do Ensino/ Treino Do Futebol. Futeb. em Rev. 1983, 4, 47–49. [Google Scholar]

- Garganta, J.; Pinto, J. O Ensino Do Futebol. In O Ensino dos Jogos Desportivos; Oliveira, A., Graça, J., Eds.; Faculdade de Ciências do Desporto e de Educação Física da Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 1994; pp. 95–136. [Google Scholar]

- Castelo, J. Futebol-a Organização Do Jogo. In Estudos 2-Estudo dos Jogos Desportivos. Concepções, Metodologias e Instrumentos; Tavares, F., Ed.; Faculdade de Desporto da Universidade do Porto: Porto, Portugal, 1999; pp. 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hainaut, K.; Benoit, J. Enseignement Despratiques Physiques Spécifiques: Le Football Moderne-Tactique-Technique-Lois Du Jeu; Presses Universitaires de Bruxelles: Brussel, Belgium, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Teoldo, I.; Garganta, J.; Greco, P.J.; Mesquita, I. Princípios Táticos Do Jogo de Futebol: Conceitos e Aplicação. Mot. Rio Claro. 2009, 15, 657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, E. Learning & Teaching Soccer Skills; Publ. Melvin Powers, Wilshire Book Company: Chatsworth, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Praça, G.M.; Pérez-Morales, J.C.; Moreira, P.E.D.; Peixoto, G.H.C.; Bredt, S.T.; Chagas, M.H.; Teoldo, I.; Greco, P.J. Tactical Behavior in Soccer Small-Sided Games: Influence of Team Composition Criteria. Braz. J. Kinanthropometry Hum. Perform. 2017, 19, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoldo, I.; Garganta, J.; Greco, P.J.; Mesquita, I. Análise e Avaliação Do Comportamento Tático No Futebol. Rev. Educ. Fis. 2010, 21, 443–455. [Google Scholar]

- Tenga, A.; Kanstad, D.; Ronglan, L.T.; Bahr, R. Developing a New Method for Team Match Performance Analysis in Professional Soccer and Testing Its Reliability. Int. J. Perform. Anal. Sport 2009, 9, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Meehl, P.E. Construct Validity in Psychological Tests. Psychol. Bull. 1955, 52, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguera, M.T.; Blanco-Villaseñor, Á.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Losada, J.L. Diseños Observacionales: Ajuste y Aplicación En Psicología Del Deporte. Cuad. Psicol. Deport. 2011, 11, 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera, M.T.; Blanco-Villaseñor, Á. Cómo Se Lleva a Cabo Un Registro Observacional? Butilletí Lar. 2006, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeman, R. Untangling Streams of Behavior: Sequential Analysis of Observation Data. In Observing Behavior: Vol. 2. Data Collection and Analysis Methods; Sackett, G.P., Ed.; University of Park Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1978; pp. 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo Parada, S.A.; Calderón Vargas, M.A. Diseño y Validación de Un Instrumento Observacional Para La Valoración de Acciones Tácticas Ofensivas En Fútbol-Vatof (Design and Validation of an Observational Instrument for the Evaluation of Offensive Tactical Actions in Football-Vatof). Retos 2020, 38, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, R.; González-Ródenas, J.; López-Bondia, I.; Aranda-Malavés, R.; Tudela-Desantes, A.; Anguera, M.T. “REOFUT” as an Observation Tool for Tactical Analysis on Offensive Performance in Soccer: Mixed Method Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacón-Moscoso, S.; Anguera, M.T.; Sanduvete-Chaves, S.; Losada, J.L.; Lozano-Lozano, J.A.; Portell, M. Methodological Quality Checklist for Studies Based on Observational Methodology (MQCOM). Psicothema 2019, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabin, B.; Camerino, O.; Anguera, M.T.; Castañer, M. Lince: Multiplatform Sport Analysis Software. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 4692–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casamichana, D.; Castellano, J. Time-Motion, Heart Rate, Perceptual and Motor Behaviour Demands in Small-Sides Soccer Games: Effects of Pitch Size. J. Sports Sci. 2010, 28, 1615–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Nieto, H. Contributions to Statistical Analysis; Universidad de los Andes: Mérida, Venezuela, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bulger, S.M.; Housner, L.D. Modified Delphi Investigation of Exercise Science in Physical Education Teacher Education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2007, 26, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, A.; Camerino, O.; Iglesias, X.; Anguera, M.T.; Castañer, M. LINCE PLUS: Research Software for Behavior Video Analysis. Apunt. Educ. Física Esports 2019, 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, T.; Camerino, O.; Garganta, J.; Pereira, R.; Barreira, D. Design and Validation of an Observational Instrument for Defence in Soccer Based on the Dynamical Systems Theory. Int. J. Sport. Sci. Coach. 2019, 14, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, D.; Garganta, J.; Prudente, J.; Anguera, M.T. Desenvolvimento e Validacão de Um Sistema de Observacação Aplicado à Fase Ofensiva Em Futebol: SoccerEye. Rev. Port. Cien Desp. 2012, 12, 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Toro, E.; García-Angulo, A.; Giménez-Egido, J.M.; García-Angulo, F.J.; Palao, J.M. Design, Validation, and Reliability of an Observation Instrument for Technical and Tactical Actions of the Offense Phase in Soccer. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeazarra, I. Análisis de La Respuesta Física y Del Comportamiento Motor En Competición de Futbolistas de Categoría Alevín, Infantil y Cadete, Tesis Doctoral; Universidad del País Vasco: Leioa, Biscay, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Gleser, G.C.; Nanda, H.; Rajaratnam, N. The Dependability of Behavioral Measurements: Theory of Generalizability for Scores and Profiles; Sons, J.W., Ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, I.; Newell, C. Measuring Healh: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, J.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Gómez De Segura, P.; Fontetxa, E.; Bueno, I. Sistema de Codificación y Análisis de La Calidad Del Dato En El Fútbol de Rendimiento. Psicothema 2000, 12, 635–641. [Google Scholar]

- Anguera, M.T. Metodología Observacional. In Metodología de la Investigación en Ciencias del Comportamiento; Arnau, J., Anguera, M.T., Benito, J.G., Eds.; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 1990; pp. 125–238. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences; Lawrence Earlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.G.; Marshall, S.W.; Batterham, A.M.; Hanin, J. Progressive Statistics for Studies in Sports Medicine and Exercise Science. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, J. Observación y Análisis de Juego En El Fútbol. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad del País Vasco, Leioa, Biscay, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, D. Practical Statistics for Medical Research; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Mendo, A.; Blanco-Villaseñor, Á.; Pastrana, J.L.; Morales-Sánchez, V.; Ramos-Pérez, F.J. SAGT: New Software for Generalizability Analysis. Rev. Iberoam. Psicol. Ejerc. Deport. 2016, 11, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, D.; Thorpe, R. A Model for the Teaching of Games in Secondary Schools. Bull. Phys. Educ. 1982, 18, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Olthof, S.B.H.; Frencken, W.G.P.; Lemmink, K.A.P.M. A Match-Derived Relative Pitch Area Facilitates the Tactical Representativeness of Small-Sided Games for the Official Soccer Match. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2019, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.; Hungler, B. Nursing Research: Principles and Methods; JB Lippincott & Co: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).