Abstract

The island of Muharraq in the Kingdom of Bahrain was previously in a state of socioeconomic disrepair and neglect, until the nine years-long “Pearling Trail” project revived the area. Historically, Muharraq’s importance inheres in it being the main trade center of the Middle East since the Mesopotamian period, especially as the source of the finest pearls in the world. However, the discovery of oil that led to the rapid urbanization of the region and Japan perfecting the production of cultured pearls had meant that Muharraq dwindled out of cultural significance. Due to the residents’ dissatisfaction and nostalgia for the island’s past glory, along with the government’s new policies towards cultural preservation, the “Pearling Trail” Project commenced in 2012. The Ministry of Culture of Bahrain repaired, renovated and preserved an area of 3.5 km, transforming it into an eco-museum with a thriving business and cultural community. The transformation of the island elevated the city into a trendy local attraction, hosting local and global cultural festivals and events, owing to the “Pearling Trail’s” Urban Regeneration Project’s success. By studying the “Pearling Trail” three success factors are identified: Project expansion beyond UNESCO preservation requirements, focus on sustainability and continuous use, and improved access to culture and cultural opportunities. Identifying these factors could allow for future preservation projects in Bahrain or elsewhere to be upgraded for urban regeneration or revitalization.

1. Introduction

The Kingdom of Bahrain’s second UNESCO World Heritage Site is the Pearling Trail located on the island of Muharraq. This site is distinguished from others by the Bahraini government’s success in elevating it from cultural reservation to an urban regeneration project. The most significant accomplishment of Bahrain Pearling Trail regeneration project is how it revitalized Muharraq, combining historic storytelling of the region’s pearl industry with cultural preservation while generating direct economic benefits [1]. Bahrain’s first UNESCO World Heritage Site, as Qal’at al-Bahrain, also known as the Bahrain Fort or the Ancient Harbor and Capital of Dilmun, was awarded the title in 2005, pales in comparison to the Pearling Trail in terms of socioeconomic impact. At the time, the award of such a title was an outstanding achievement, yet it did little more than add another name to the must-visit list of tourists who happen to stop by Bahrain. Although the fort faces a beach and has a spectacular ocean view, yet efforts to make the area more tourist-friendly have not gone beyond small museum with a modest semi-traditional café. Despite its location close to the central shopping district in Bahrain, it stands isolated. Most of the attraction basis of the site relies on local endeavors to host small family festivals, inviting food trucks to the area, and privately-owned horse-riding activities, all of which are not advertised to tourists, maintaining a visitor populace of locals only.

Thus, with the Pearling Trail Project the main challenge was to expand the goal from merely obtaining the UNESCO Site title that may generate global fame for a limited amount of time and instead create a project that achieves cultural preservation as well as socioeconomic revitalization that benefits multiple stakeholders. By correct identification of renovation, preservation, and development opportunities along with full cooperation between various governmental bodies and the local community the project has superseded the status of a historical site into becoming a key player in the area’s cultural rebirth. A model for upgrading a cultural preservation project to achieve urban regeneration can be established by studying this project’s progress.

2. History: Centuries of Pearl Diving and Trade

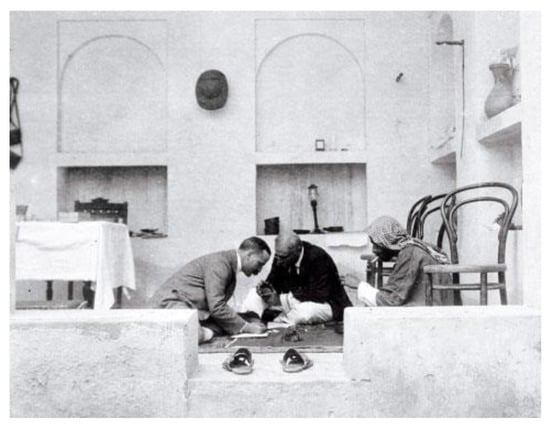

Located in the Arabian Gulf, the archipelago of the Kingdom of Bahrain is famous for being a historic trade point along with its rich pearl fisheries. Part of Dilmun during the Bronze Age, present-time Bahrain’s location made it the top trading destination. It linked the Indus Valley and Mesopotamia and was known since then for high quality pearls [2]. Throughout its history, Bahrain was ruled by different empires and referred to by many different names, yet what remain constant is its flourishing pearling industry. Specifically, the island city of Muharraq was the main point for trading and producing pearl products, as the third largest city and the island’s capital until 1932 [2]. While the Gulf region as a whole was famed for its pearls, Bahraini pearls were, and continue to be, higher in quality and approximately 40% more expensive to buy [3]. During the golden age of Bahrain’s pearling industry, this level of quality attracted world renowned jeweler Jacques Cartier, who continuously visited Muharraq from 1910 to 1923 and was heavily influenced by the Arab and Eastern lifestyle, allowing it to inspire his art-deco designs (Figure 1) [4]. Thus, as a trade center, the Muharraq marketplace, or ‘souq’ in Arabic, developed into a hub of international trade and business. Cafes that served traditional tea and snacks nestled alongside jewelry shops, clothing stores, and sweets shops, catering to the tradesmen who would need a meeting spot to discuss trade and then purchase souvenirs before traveling back home [5].

Figure 1.

1911, Jacques Cartier in a meeting with Bahraini pearl merchants. (Smith, 2015).

However, three global events in the 1930s initiated the downfall of the Bahraini pearl industry: A depression following the first World War that reduced global demand for expensive jewelry, including pearls, the discovery of oil on the island redirected economic investments, and the perfection of cultured pearls by Japan. The last one held the most influence, with the Bahraini government going as far as prohibiting the import, transport, sale, possession, or manufacture of cultured pearls in 1930 as King’s Regulation No.1 of that year. Regardless of the local ban, the global demand for cheaper cultured pearls had a direct impact on the merchants, ship captains, nearly 30,000 pearl divers, and by extension, Muharraq as a whole, plunging them into financial difficulty [6].

The downfall of the traditional pearling industry fueled the ambition to modernize the city Muharraq, which was urbanized during the 1950s and 1960s through land reclamation on the waterfront, widening roads, and incorporating new motorways [6]. For the most part, Muharraq maintained the basic layout of a traditional Islamic town as per custom in the region. Still, the modernization of traditional houses and construction of new buildings to provide low-cost housing for the Bahraini lower or middle classes posed a severe challenge to the conservation of the historical urban architecture. As noted by historians, it appears that the government did not realize the historic significance of the area until the 1980s, and quickly took legislative preventative measures to preserve the buildings in the area [7]. Nonetheless, this led to a further decline of the area due to three factors: first, many traditional buildings were unlivable as they were in desperate need of renovation. Second, the government had limited any changes to only the buildings’ interior as per conservation laws, leading to haphazard modernization work. Finally, the combination of these two factors together along with the oil boom drove the original inhabitants out of the area, leading owners to sublease these buildings to Southeast Asian migrant laborers at low cost as many of the buildings were inhabitable [8]. With a growing population of low-class laborers and patchy regulations that allowed multistory buildings to spring up randomly in the area, the once glorious ‘souq’ became a destination for buying cheap wares and small businesses catering to low-income immigrants [7].

3. Decision: Recovering the Pearl

Despite the governments’ best intentions in the past, lack of overall planning hindered genuine preservation and regeneration of the area. The government had made significant efforts to preserve the pearling industry in Bahrain, by banning cultured pearls and creating pearl authentication labs. However, this effort did not extend to the customer facing platform, the souq itself [9]. Additionally, practitioners of the pearl trade and remaining residents of the area found themselves longing for the glorious past, as they found the old souq overcrowded by low skill laborers and the place itself marred with wires and badly placed modern fixings [9]. Simultaneously, the demographic change to the area attracted beggars and common muggers [10]. Residents filed complaints and filled newspapers with grievances as their petitions to rebuild or fix the traditional buildings were rejected due to preservation laws [10,11].

In 2006, due to the continuous complaints about the unlivable state of the buildings, the government had plans to tear down all the traditional buildings in the area and build a new shopping mall. However, a protest to this plan headed by Shaikha Mai Bint Mohammed Al-Khalifa, present Minister of Culture, succeeded in stopping this from happening [12]. The government’s prior acknowledgment of this area’s historical and cultural significance is evident through the heavy preservation laws, funding of archaeological teams to study the area and the renovation of Sheikh Isa House starting in the 1970s [7]. However, the leadership of Shaikha Mai Al-Khalifa would organize these efforts more effectively and expand the project to revitalize the island.

Hence, the consistent nudging of residents and people in the pearl industry, alongside a governmental recognition of the cultural value that could support the tourism vision for Bahrain, led to the start of the Pearling Trail project.

4. Development: A Combination of Efforts

As mentioned before, conservation and development efforts were previously atomistic, functioning on a micro-level only without a proper macro-level goal. Furthermore, efforts focused only on preservation and protecting the past without giving life to it again. The primary pearl diving seashore and the individual sites in Muharraq all have national protection as designated national monuments since 2010 under the Ministry of Culture. Moreover, the three oyster beds and their marine buffer zone were generally protected since 2011 at a national level as per a legislative decree that designates these types of sites as national marine protected areas under the Fisheries Directorate and Supreme Council for the Environment [13].

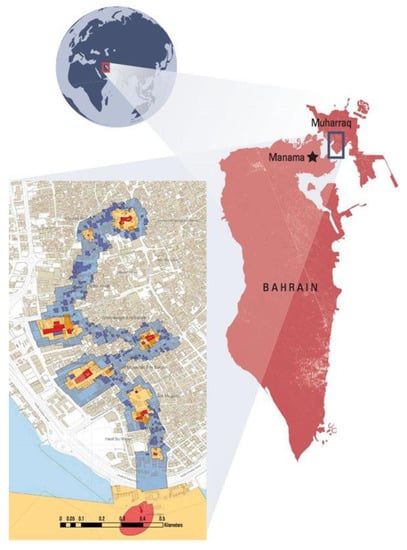

On May 2008, Bahrain officially submitted Muharraq’s pearling industry areas to be included on the tentative list for UNESCO World Heritage Site under the title “Pearling” (Figure 2). In 2010 UNESCO asked Bahrain to expand upon this proposal with details regarding the project’s phasing and implementation, arrangement of the urban buildings, the methodology for optimizing the preservation of the original fabric of the city, and information on the necessary skills that will be utilized in the restoration of the decorative woodwork and plasterwork [14]. By 2012, Bahrain returned with full details on conservation and management processes, architectural and urban conservation, initiatives for capacity building and minor extension of the boundaries. Leading on this project, the Ministry of Culture has managed to identify the heritage importance of more than just the three off-shore oyster beds, by including a part of the seashore at the southern tip of the island as well as seventeen buildings that form an essential part of the urban fabric of Muharraq [15].

Figure 2.

A map of the Pearling Trail Project, detailing the three oyster beds, 17 buildings, and seashore. (UNESCO).

The inclusion of multiple historical buildings located in a bustling shopping and residential area introduced a complex new dimension to the project, evolving from an environmental preservation project to a historical and cultural conservation and restoration project that spanned 3.5 km. Beyond the items listed in the UNESCO submission, Bahrain decided to expand the project to include a further 12 buildings, the establishment of multiple open spaces, car parks for residents and visitors to the area, and renovation of 750 house facades. This decision pushed the budget for the project from $39.7 million to $47.9 million [16].

To accomplish such a feat, direct partnership with an expert was required and stepping in was Britta Rudolff, a UNESCO World Affairs counselor who took on the role of heritage advisor to the Bahraini government [17]. Furthermore, the added involvement of 12 government bodies and heavy reliance on owners of the homes and people from the pearl trading industry for their cooperation, feedback and support in terms of information and resources required an advanced level of communication and organization [18,19]. Additionally, Bahrain’s decision to hire a mobility consultant to identify pedestrian spaces and parking spaces while accounting for cultural habits, the overall layout and climate factors is emblematic of the government’s plans for Muharraq [20].

The project began by first renovating and refurbishing the 17 buildings listed, from simple homes and shops to big palaces and mosques. The Shaikh Ebrahim Bin Mohammed al-Khalifa house was rebuilt and converted into a Center for Culture and Research in 2002, and under the Ministry of Culture, became the key manager of renovation and cultural projects in the area. Through the Center’s work with establishing community centers and cafés, it is apparent that Center’s goal is to engage in “soft” initiatives as opposed to “hard” initiatives such as physical restoration work as per Shaikha Mai’s vision [12]. For example, while the Center itself maintained a large part of its original historical architecture, it has been mainly rebuilt to accommodate a public hall for local art and culture events (Figure 3). Moreover, by upholding a restoration policy focused not on the preservation of cultural heritage in its existing state but instead identifying and anticipating active use of historical buildings, the adaptive re-utilization of these traditional structures played a vital role in elevating the Pearling Trail into an urban regeneration project [12]. Most noteworthy is how these initiatives prioritized utilization by local residents above developing them into tourist resources, effectively ensuring longevity of use.

Figure 3.

The theatre inside Shaikh Ebrahim Center for Culture and Research, showing part of the ancient wall blended in with the modern design. (Bahrain Ministry of Culture).

Although implementing identical repairs on each building would have been more straightforward, as per the studies conducted, it became apparent that each building required varying levels of renovation and needed to be repurposed differently [7]. This was advantageous to the project’s success. Post-renovations, some of the buildings host exhibits about the history of the pearling industry, traditional medicine, and Bahrain’s first newspaper. Others function as centers for preserving specific local crafts, such as the Kurar House dedicated to teaching the art of gold embroidery [15]. Historical documents, pictures and important tools were collected from homeowners and national archives and placed in glass displays where appropriate. As renovations took place, the Ministry installed bi-lingual signage throughout the area in order to direct people to these traditional houses.

In particular, the renovation of the Siyadi properties, which included a mosque, two residences and, most importantly, a series of shops and storehouses played an indispensable role in revitalizing the local economy. These stores were leased to ambitious entrepreneurs who worked with the Ministry of Culture to create cafés and shops that preserved the traditional Bahraini architecture yet fitted with modern facilities to create a unique experience. A perfect example is “Saffron”, a café serving traditional Bahraini food with a glass flooring to showcase the property’s original purpose as a “madbasa”, which is where dates were traditionally made into syrup [21]. This combination of a historical setting, traditional food and modern café service created an interactive atmosphere for people to thoroughly immerse themselves in the area’s history. The shops and cafés housed in these traditional structures offer various degrees of traditionalism and modernization, from hip cultural art fixtures to historical mini-exhibits, showcasing the level of cooperation between the Ministry of Culture and the entrepreneurs.

The Bu Maher fort (Figure 4), representing the start of the Pearling Trail has been renovated since 2010, and was made fit for visitors with light decorations within the fort and a dedicated visitor’s center and mini-museum next to it. This building is one of the many examples of modern structures built with thoughtful design to act as an information point along the trail and includes a boat tour that connects the island of Muharraq to the island of Manama and the National Museum. The Ministry also decided to rebuild the Al Khalifiya Library, demolished in the 1980s, even though it is not under the UNESCO World Heritage listing [22]. This decision is one of many that represents the government’s determination to expand the renovation efforts beyond the original UNESCO requirements. Furthermore, rather than mimic the building’s old design, the modern design uses traditional materials and patterns, giving a contemporary feel to the area without appearing inharmonious. The library also serves as a community center, a function that is impossible to assign to one of the UNESCO listed buildings due to fear of damaging those structures with frequent public use. The care taken to create these mini-exhibits along the 3.5 km stretch reflects the cultural identity of Bahrain without an intransigent museum feel [23]. As per the mobility consultation, the government also renovated the streets and fitted the area with multiple public spaces for people to rest, using traditional materials and natural elements to create microclimates and serve as guidance along the path (Figure 5) [1].

Figure 4.

Interior of the Bu Maher Fort (Bahrain Ministry of Culture).

Figure 5.

Example of a microclimate incorporating pearl symbolism and natural elements (Aga Khan Development Network).

Finally, the power given to the Shaikh Ebrahim Center for Culture and Research to be the primary mediator and organizer that communicates with the public and lobbies private organizations for funding, allows for continuous use of the buildings [24]. By hosting multiple events and creating centers for teaching old crafts along with providing the public with information, the area is kept alive and bustling at appropriate times throughout the year while encouraging the local economy.

5. Results: A City Brought Back to Life

After the submission in 2008, the Pearling Trail project was completed as per UNESCO’s requirements and gained the World Heritage Site title in 2012, yet it was not until 2021 that it was completed as per the goals Bahrain set for itself. The creative use of the traditional houses, the addition of other modern buildings to act as cultural centers, and the incorporation of public spaces for pedestrians and cars collectively allowed for business and cultural activity to flow back to the area.

Comparing the Pearling Trail to Bahrain’s other UNESCO World Heritage Sites, the differences in terms of the effectiveness of this project become apparent. The area around the Bahrain Fort was not developed to its full potential, and the fort itself is still sparingly used as one of the venues for Bahrain’s Spring of Culture activities. Additionally, the absence of proper direction of visitor traffic to the area and the scarce parking amenities along the beach make the site difficult to access for non-locals. Finally, the lack of government incentivization for locals to host more activities makes it no more than a quick stop for any visiting tourist who would otherwise have no awareness of the scheduling of local activities in the area. The absence of new infrastructure that can be used freely, the difficulty of access to the area, and no plans for sustainable use of the space make this site a lost opportunity for further socioeconomic development. Hypothetically, incorporating a boat tour, or adding more infrastructure could encourage more local businesses to setup shop along the beachside, enhancing the site’s cultural and economic importance.

In comparison, the Pearling Trail plays host to multi-faceted education and cultural events and businesses, brought to life by government and local efforts. The study of local transportation and pedestrian behaviors increased the attractiveness of the location for cultural events. The use of a boat tour as a point of connection between the National Museum and Bu Maher fort as the entrance to the area takes advantage of Bahrain as an island and creates a unique experience. The sprinkling of cultural centers throughout the trail allows for diversified use of the space.

In an assessment of venues hosting events during Bahrain’s Annual Spring of Culture Festival, the area’s elevation into a functioning cultural center becomes vividly clear. Between 2008 and 2019, the number of events hosted in venues within the Pearling Trail doubled, thanks to the efforts of the Shaikh Ebrahim Center. Moreover, a walkathon of the Pearling Trail has become a staple in the annual festival since 2017, a testament to how the area has become more walkable and attractive for visitors compared to its previous downtrodden state [25].

Furthermore, Muharraq was selected as the Islamic Capital of Culture for 2018, recognized as per the criteria for its documented historical authenticity, outstanding contribution to knowledge and learning that singles it out in the country and the region, and a significant input in Islamic culture and human culture in general [26]. This created an opportunity for further planning of Islamic family friendly events that would change the tourist demographic of the country from weekend party seekers to Muslim family travelers, and redirects the investment in the tourism industry from hotels to events. This demographic change also means the inpour of revenue into more legitimate businesses that are tourist and family-friendly [27,28].

In recognition of the project’s design, the Pearling Trail has received the Aga Khan Award in 2019, which recognized the storytelling aspect of the trail for its inclusion thematic materials and pearl symbolism in the design of all spaces [1]. This award adds to the international recognition of the project and Bahrain’s efforts.

Bahraini footfalls in the area now have increased, popularizing the city as a weekend site for visiting by artists, families and elders. The mini-exhibits, restaurants and shops, and usable public spaces have attracted more people to the area. Those who previously wrote of their longing for the past and positive change filled local newspapers with praise for the project’s impact [29]. Urban renewal is highlighted by new local markets and reviving the culture and history of the people.

6. Conclusions: A Successful Project

In conclusion, a project of this scale is complicated, requiring heavy reliance on the cooperation of people, deep research, and a continuous need to step back to look at the whole picture. In analyzing the Pearling Trail’s progress, three factors elevated the project from a conservation project to the urban regeneration of Muharraq; project expansion, focus on sustainability, improvement of access. As UNESCO is more focused on preservation, expanding the project to include other sites and public spaces incorporated more of the city into the project and improved sustainability and access. The additional buildings, public spaces, and car parks allow for easier physical access to an area that was previously deemed unsightly and unsafe. As the historical buildings must be protected, the new structures allow for more unrestricted use of the space for cultural activity, events, and business opportunities to arise, increasing revenue in the area. By establishing the Shaikh Ebrahim Center for Culture and Research as the leader of soft initiatives in Muharraq, continuous access to culture and proper utilization of the facilities is ensured. Upon completion of the project in 2021, the Ministry of Culture, visitors, and residents alike all praise the transformation of the city [29].

The success of this project creates a model for inspiring similar regeneration of other areas in Bahrain. The capital of Manama is on the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the title submission of “Manama, City of Trade, Multiculturalism and Religious Coexistence” since 2018 [30]. There are various resemblances between the two cities, including historically and culturally valuable buildings, a fall into disrepair due to mixed conservation efforts, influx of migrant laborers, and residents’ eagerness for renewal and rejuvenation. By studying the Pearling Trail project and identifying key success factors, it is possible to use it as a blueprint for the old Manama souq area’s Urban Regeneration that will allow the area to reach its full socioeconomic potential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T.N. and J.L; methodology, J.L.; validation, H.T.N., J.L. and H.C.; formal analysis, H.T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.N.; writing—review and editing, J.L.; supervision, J.L. and H.C.; project administration, J.L.; funding acquisition, J.L and H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is past publishments and news reports.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Revitalisation of Muharraq. Aga Khan Development Network. Available online: www.akdn.org/sites/akdn/files/media/documents/akaa_documents/2019_akaa_cycle/project_descriptions/revitalisation_of_muharraq_-_project_description_english.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Crawford, H. Dilmun and Its Gulf Neighbors; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- “Despite Oil Boom, Pearl Industry Still Bright in Bahrain” (Translated Title). Al Wasat, 3 March 2010; p. 13.

- Smith, S. In Pictures: Bahrain’s Ancient Pearl Fishing. BBC. 19 January 2015. Available online: www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-30724681 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- “Nostalgia… India Was The Biggest Market for Pearls Until Collapse of The Kingdom” (Translated Title). Al Khaleej. 3 February 2008. Available online: www.alkhaleej.ae/supplements/page/bed51b0c-2632-462a-87db-968ee02c528c (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Center for Islamic Area Studies Kyoto. Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies; Center for Islamic Area Studies Kyoto: Kyoto, Japan, 2011; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mahari, S. “Preserving Historical Building—Buildings of Muharraq” (Translated Title). In International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property; ICCROM: Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 2017; pp. 328–382. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulla Mohamed Ghanem Mohamed AlSulaiti. Muharraq City: A GIS-Based Planning Strategy for Its Ancient Heritage Conservation; E-Book; University of Portsmouth: Portsmouth, UK, 2009; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- “Al-Fardan for Documenting the History of Pearls and Setting Poetry Night” (Translated Title). Al Bilad Press. 15 May 2010. Available online: http://www.albiladpress.com/news_inner.php?nid=76900&cat=1 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- “Old Muharraq <<…Collapsing Homes Awaiting Infrastructure Refurbishment>>” (Translated Title). Al Wasat News. 8 June 2012. Available online: www.alwasatnews.com/news/676018.html (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Musbah, T. “Old Muharraq <<Qaysariya>> Souq Awaits Developments” (Translated Title). Al Watan News, 3 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Survey Report on the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Bahrain. Japan Consortium for International Cooperation in Cultural Heritage. Available online: www.jcic-heritage.jp/doc/pdf/2012Report_Bahrain_eg.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Pearling, Testimony of an Island Economy. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.Whc.unesco.org/en/list/1364/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- “Oil Industry Thrives Despite Oil Surge” (Translated Title). Al Wasat News. 5 March 2010. Available online: www.alwasatnews.com/news/376855.html (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Pearling, Testimony of an Island Economy. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.Whc.unesco.org/document/152484 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Bahrain’s Pearl Trail Project Approved. Construction Week Online. 21 July 2014. Available online: https://www.constructionweekonline.com/article-29235-bahrains-pearl-trail-project-approved (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Frederik, R. Bahrain Seeks UNESCO Listing for Pearl Diving Plan. Reuters. 27 January 2010. Available online: www.reuters.com/article/us-bahrain-pearls-unesco/bahrain-seeks-unesco-listing-for-pearl-diving-plan-idUSTRE60Q3AS20100127 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- San’e, H. “Heritage Filled Pearling Trail Takes Bahrainis Back in Time” (Translated Title). Al Arabiya. 24 October 2012. Available online: www.alarabiya.net/articles/2012%2F10%2F24%2F245652 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- “Ministry of Culture Asks Residents of “Pearling Trail” to Cooperate in Elevation Project” (Translated Title). Al Wasat News. 16 November 2016. Available online: www.alwasatnews.com/news/1181204.html (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Bahrain Pearling Testimony (UNESCO Site) Mobility Study, Systematica. Available online: www.systematica.net/project/bahrain-pearling-testimony-unesco-site-mobility-study/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- “2014 Bahrain Summer Festival” (Translated Title). Ministry of Culture Bahrain. Available online: https://www.Culture.gov.bh/ar/mediacenter/publications/booklets/File,11440,ar.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Francisca María González, Khalifeyah Library. Arch Daily. 30 April 2018. Available online: www.archdaily.com/893450/khalifeyah-library-search (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Askar, M. “Pearling Trail, A Bahraini Project Documenting A 40 Century Old Craft” (Translated Title). Raseef22. 9 July 2016. Available online: https://www.raseef22.com/article/27418-bahraini-trail-a-project-that-documents-pearl-hu (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- History of the Center. Shaikh Ebrahim Center. Available online: https://www.Shaikhebrahimcenter.org/en/history-of-the-center/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Past Events. Spring of Culture. Available online: https://www.Springofculture.org/past-events/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- ISESCO Deputy Director General participates in launch ceremony of Mashahd’s celebration as Asian Region’s Islamic Culture Capital for 2017. ICESCO. Available online: www.icesco.org (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- BACA’s Press Conference Unveiled Events Celebrating Muharraq, Capital of Islamic Culture 2018. Ministry of Culture. Available online: www.culture.gov.bh/en/mediacenter/news_center/2018/January2018/Name,15645,en.html (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Al-Suhaymi, O. Bahrain: Unprecedented Investment Flows into 14 Strategic Tourism Development Projects. Asharq. 23 April 2018. Available online: https://www.Aawsat.com/english/home/article/1246661/bahrain-unprecedented-investment-flows-14-strategic-tourism-development (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Al-Naham, E. “Pearling Trail. Where the Tale Continues” (Translated Title). Al Bayan. 12 March 2021. Available online: https://www.Albayan.ae/world/gcc/2021-03-12-1.4113496 (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- Manama, City of Trade, Multiculturalism and Religious Coexistence. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.Whc.unesco.org/en/tentativelists/6354/ (accessed on 29 April 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).