Abstract

The cut-throat situation of competitiveness in almost every business sector, followed by globalization, shortened product life cycles, and rapid technological changes have raised the importance of innovation to overrun the rivals. Scholars have established that appropriate leadership style is a key enabler for organizational success. However, it is not clear in existing literature how the concept of authentic leadership is related to innovative work behavior (IWB). Likewise, the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) to induce IWB is also vague in current literature. Thus, the basic purpose of the current study was to test the relationship of CSR and IWB with the mediating effect of authentic leadership. The proposed model was tested in the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) sector of China. The data were collected through a questionnaire that was distributed among different respondents of the current survey. The data were obtained from a dyad of supervisor and subordinate serving in different SMEs in Wuhan city of China. The study used the structural equation modeling (SEM) technique to validate different hypotheses. The empirical results confirm that CSR positively relates to IWB while authentic leadership partially mediates this relationship. The findings of the current survey will be helpful for policymakers to recognize employees as a source of innovation through CSR and authentic leadership.

1. Introduction

The contemporary corporate world is not without cases of wrongdoing and creed-based behavior. Not all leaders are great, and acknowledgment of this fact can generally be the very first step toward improved corporate direction for a better leadership style [1]. To be able to lead, corporate leaders and contemporary scholars have turned to the notion of authentic leadership [2]. Authentic leadership is a leadership philosophy that considers that real leadership is grounded on values and may direct people toward the greater good [3]. A true leadership model such as authentic leadership will ensure that moral and ethical standards are at their best in an organization [4]. Since this model of leadership promotes morality at all levels of an organization, a stable ethical image of the organization among employees is developed [5]. Authentic leaders do not focus on self-gain as they want the business to succeed and thrive, together with the subordinates [6]. Perhaps this is the reason that contemporary researchers and policymakers have shown a greater interest to explore more and more about authentic leadership than ever before [7,8,9,10].

Globalization has brought different challenges along with opportunities for contemporary businesses. These challenges include a stiff competitive environment, shortened product life cycles, and a volatile business environment [11]. This is why there is a great concern shown by academicians and practitioners to increase the innovation capability of a business to survive in this volatile business environment [12]. Thus the innovation capability of an organization is a critical element for long-term business success. Employees are considered as one of the strategic enablers for innovation [13,14]. Researchers have long explored different factors that urge employees to engage in IWB, for instance, the relationship of knowledge sharing and IWB [15,16], organizational climate, and IWB [17,18], absorptive capacity and IWB [15], leadership and IWB [19,20,21], etc. However, there is common consent among contemporary scholars that the style of leadership is one of the most cited factors that encourage employees for innovative behavior at workplaces.

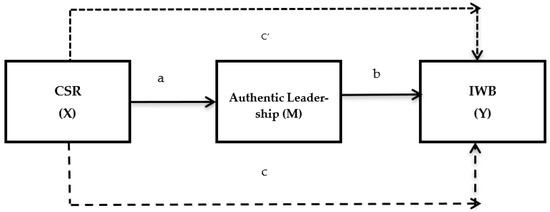

A plethora of studies have acknowledged that authentic leadership can bring multi-faceted outcomes for an organization such as improved organizational commitment [22,23], organizational citizenship behavior [24,25], employee performance [26], employee engagement [27], etc. However, it is not clear in the prior literature how authentic leadership can be related to inducing workplace innovative behavior of the employees. Moreover, there exists an observable gap in the literature on how corporate social responsibility (CSR) relates to authentic leadership and IWB. Therefore, the objectives of the current survey were twofold. First, this study intended to explore the relationship of CSR with authentic leadership and IWB. Second, the study attempted to link CSR and IWB via the mediating role of authentic leadership (Figure 1). The study used the lens of social learning theory to explain why authentic leadership may urge employees to show their innovative skills at the workplace. In this regard, the authors’ argument is that as the authentic leader shows caring behavior for his followers, the followers learn this caring behavior and want to care for their organization. Thus, they are expected to support their organization through their extra-roles such as IWB.

Figure 1.

Proposed research model based on authors’ conception where CSR (X) = the predictor variable, IWB(Y) = the criterion variable, authentic leadership (M) = the intervening variable, c = direct effect of X on Y without the effect of the mediator, c′ = indirect effect of X on Y with the mediator, a = the direct relation of X with M, b = the direct relation of M with Y.

CSR has received a growing focus from academicians and practitioners of different sectors during the last two decades [28]. CSR continues to be defined as a business’s actions and policies that consider various kinds of stakeholders along with the three pillars of economic, societal, and ecological operation as initially articulated by Carroll [29] to create a theoretical foundation for CSR. There is an increasing recognition that the interests of the society and organizations tend to be more closely coordinated than is frequently presumed, and hence, CSR frequently determines the business’s long-term effectiveness [30]. As a matter of fact, during 2019, it was reported that various corporate leaders have redefined their organizational mission statements by acknowledging that the businesses are not only accountable to shareholders, but they are equally accountable to all of their stakeholders [31].

Prior CSR literature has generally acknowledged that the stakeholders of an organization have a significant impact on the overall performance of the organization [32,33,34]. The employees of an organization are also key stakeholders and they are strategic enablers for a business to achieve different business goals [35]. There is general agreement in the existing literature that organizations with a greater focus on their employees are likely to experience multiple benefits that are even beyond the financial objectives [36,37,38]. The philosophy of CSR stresses care for all stakeholders including the employees; however, it is unclear from the existing studies how CSR engagement of an organization can be linked to IWB at workplaces and what the role of authentic leadership is in this relationship. Hence, the basic objective of the current study was to investigate the relationship of CSR and IWB with the mediating effect of authentic leadership.

The proposed research model of the current study was tested in the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) sector of China which was logically selected to serve the purpose of the current survey. The first logic for choosing the SME sector was that, unlike large businesses, the SME sector does not have enough resources to be spent on acquiring complex and costly equipment to innovate their processes and production. The authors’ argument here is that employees of an organization, if treated carefully, can serve as a cheap and effective source of innovation. Hence, by motivating employees, this sector can invent new ways of doing business. Another logic for choosing the SME sector lies behind the stiff competitiveness situation in this sector. Presently more than 38 million SMEs are operating in China with an annual increment of 10 percent each year during the last decade [39], which shows the stiff competition this sector is facing. Thus, to survive in such a competitive environment, adopting new and innovative ways for conducting business is a key to success and survival for this sector. Innovation is a key driver of productivity and long-term growth and can help solve social challenges at the lowest possible cost. Innovation in SMEs is at the core of inclusive growth strategies: more innovative SMEs are more productive SMEs that can offer better working conditions to their employees, thus helping reduce inequalities. Furthermore, recent developments in markets and technologies offer new opportunities for SMEs to innovate and grow. Digitalization accelerates the diffusion of knowledge and is enabling the emergence of new business models, which may enable firms to scale very quickly, often with few employees, tangible assets, or a geographic footprint. Therefore, based on the above argument the selection of this sector for the current survey is logical.

The current study adds to the existing literature in many ways. For example, the current study is an important addition to the extant literature on CSR as it considers it to induce innovative behavior of employees at workplaces which is not well-explored in prior literature. Another important contribution of the current study to extant literature is that it acknowledges the importance of leadership as an enabler for IWB. In this regard, the previous studies have explored the relationship of different leadership styles with IWB; however, most studies investigated the impact of transformational leadership on IWB, but the relationship of authentic leadership with IWB is not given due consideration by extant researchers. Last but not the least, the current study was a pioneer attempt that sought to explain the relationship between CSR, authentic leadership, and IWB in a unified model in the context of the SME sector. The remainder of this article is divided into four different sections. The coming section discusses the literature review and theory for hypotheses development. The next section describes the methodology in which sampling, data collection, and instrument development processes are explained. Then the results section deals with hypotheses validation through different statistical tests. The last section discusses the results, implications for theory and practice, and limitations of the study along with future research directions.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

The current study was based on social learning theory (SLT) by Bandura and McClelland [40] to formulate different hypotheses of the current study. SLT argues that individuals learn different social behavior by observing others. This theory is relevant to the theme of the current survey in the sense that authentic leaders care for their employees and build an honest relationship with their followers (employees in the current case). In response, the followers are also expected to learn this caring behavior and they try to support their organization by thinking about new (innovative) ways of conducting the business. Moreover, an authentic leader promotes the culture of openness in an organization and hence praises the input given by the followers. Thus the followers working under an authentic leader are encouraged to display their innovative capability without this fear that their idea will be criticized or will not be listened to. In like manner, the concept of CSR also focuses on the betterment of different stakeholders, and employees are important internal stakeholders. Thus, an organization that follows CSR principles is expected to help and support its workers. Consequently, the employees feel extraordinary motivation to help their organization, and hence they try their level best to think of new and innovative ways to help their organization.

Contemporary scholars are increasingly claiming that organizations with no inclusive outlook for all of their stakeholders in organizational philosophy are likely to gain unsatisfactory business performance [41,42,43]. The current survey defines CSR as per the definition of Carroll [44], who described it as the actions taken by organizations to take care of diverse stakeholders, such as the environment, community, and government agencies. Following this definition, the organizations are expected to work for the well-being of the entire community [45]. CSR acknowledges that companies and workers are part of society, and society and businesses finally are interconnected, rather than in competition with one another. Hence, individually and institutionally, there is not any conflicting thing between the organization and the social improvement of employees at the workplace [46]. It is generally argued that in an organization where the workplace atmosphere is supportive, the employees’ innovative capability is fostered [47,48]. The central theme of CSR is taking care of every stakeholder including the employees. A plethora of studies has established that CSR is positively related to IWB [49,50,51]. CSR activities of an organization foster an environment of confidence among the employees, and this sense of confidence urges them to take risks and think about innovative ways to induce organizational effectiveness [52]. Employees who see that an organization’s CSR efforts are focused on improving the community and the environment have a greater sense of ‘meaningful work’, which in turn improves productivity and creativity [53].

Walmart can be put as an exemplary case here that actuated “Personal sustainability plan” under which the organization empowers every one of its workers to present at least one innovative social change initiative through which the relationship of workplace and employee social life can be improved. Reportedly, over 500,000 employees working for Walmart volunteered in different CSR-related projects, and consequently, employees submitted nearly 35,000 new business solutions [54]. This is the reason that different scholars of recent times are convinced that acknowledging employees as a source of innovation is one of the secrets for business success in the long run [55]. It is without any doubt that continuous innovation is an essential business objective of contemporary businesses, and hence a holistic perspective about variables that foster innovative work behavior is imperative [56]. This study is in line with Stock [57] who defined IWB as “It is the behavior of individuals intended to initiate and deliberately create new and useful ideas or processes at the workplace”. Employee’s CSR perception of an organization influences their behavior positively [58,59]. Employees are proud to be members of a socially responsible organization that considers society and the environment in its business operations [60]. CSR engagement of an organization creates a sense of confidence and security, where employees can act without fear of consequences and take risks [61]. Thus in line with SLT, the authors’ argument here is that CSR-related activities of an organization are observed and learned by the employees, and following CSR principles, they attempt to enhance organizational performance and are encouraged to display their innovative capability at the workplace. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

CSR is positively related to innovative work behavior.

Authentic leadership is a form of leadership that values the leader and builds the legitimacy of the leader through honest relationships with the followers [62]. Consequently, authentic leaders are individuals with a clear vision that supports openness and can improve individual and team performance by building trust with the followers [63]. True leaders are those who prefer moral values and human relations over economic purpose [64]. Authentic leadership is a growing field of leadership research that has received considerable attention from contemporary scholars in recent times [2,65,66].

Theoretically, authentic leadership may enhance IWB in many ways. To start, authentic leaders can encourage the employees to come up with new and innovative solutions at the workplace [67]. This study defined authentic leadership as “a process of positive psychological capabilities, ethics, morality, relational transparency, self-regulation, social interaction and positive behavior modeling [62]”. Authentic leadership is a mechanism of improving the internal visibility of the organization’s employees and an approach to internal motivation [68]. Increased motivation is likely to encourage the employees to be more involved in IWB. Similarly, authentic leaders can provide resources, including the information, time, and support needed for IWB [69]. A leader’s authenticity is aimed at promoting and evaluating the different perspectives of different employees in an organization [70]. When employees are supported by their leader, they gain independence and freedom at the workplace to be engaged in IWB [69]. The leader’s authenticity is based on the core trust of employees in their leader, and this high level of trust plays a crucial role in stimulating the innovative capability of workers [71]. Additionally, authentic leadership can motivate employees to identify themselves while maintaining their unity (by supporting employees, ensuring fairness and equity, and sharing solutions). Moreover, authentic leaders can be a benchmark for the employees to encourage their IWB as they promote openness at workplaces [72]. An authentic leader must be involved in quality improvement at the workplace and promote transparency, honesty, accessibility, and commitment in relationships [73]. Through appropriate management, authentic leaders create opportunities for employees to think with greater responsibility and independence in decision making which ultimately stimulates their workplace innovative capability.

Authentic leadership is based on strong values and ethics and is characterized by a high level of self-awareness, intrinsic values, the openness of communication, and coordination of knowledge [64]. Within the framework of ethical issues identified in business, the emphasis of an authentic leader is on honesty, transparency, and care for all employees, which ultimately creates a positive attitude about CSR among employees [74]. It is generally considered that the thinking and behavior of a leader have a significant impact on the assessment and analysis of CSR in an organization [75,76]. Therefore, leaders, who are an integral part of the organizational environment, can be expected to have a significant impact on employees’ thinking and cognitive processes which stimulates their IWB [77]. Authentic leaders, through their relationship qualities based on honesty, trust, compassion, and high morality, develop a strong relationship with their followers and build a strong bond with them. These qualities of an authentic leader can, over time, lead to shared values and authenticity among employees and they willingly take part in different innovative activities [78]. Therefore, employees working under an authentic leader can take into account the high values of their organization when they observe different CSR activities.

As per the theory of social learning, employees are expected to follow the behavior of their authentic leader and want to support their organization to achieve better outcomes through involving themselves in IWB. Moreover, CSR also focuses on caring for others (society, stakeholders, nature, etc.), and hence an organization’s engagement in CSR activities inculcates a sense of caring among employees. The authors’ argument here is that employees working for a socially responsible organization are likely to develop a kind of spiritual consciousness that ultimately encourages them toward creativity and innovation. Thus, CSR and authentic leadership encourage the employees to be engaged in IWB. Therefore the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Authentic leadership is positively related to innovative work behavior.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Authentic leadership mediates between CSR and innovative work behavior.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample, Data Collection, and Handling of Common Method Bias

Data for the current study were collected from the SME sector of China. To do this, the authors selected Wuhan city of China which is a large city in the country in which several SMEs are situated. Before the formal proceedings of the data collection, the authors, first of all, contacted the spokespersons of different SMEs for an initial screening about the engagement of an SME in CSR activities. After carefully assessing their CSR activities, the authors prepared a list of SMEs which were involved in CSR practices. After that, the authors randomly selected some SMEs and asked the concerned authorities to cooperate in the data collection process. Those SMEs that showed their initial consent were listed again for the final data collection phase. In this regard, the authors randomly selected 21 SMEs including different sectors such as textile, petrochemicals, footwear, equipment manufacturing, and others (see Table 1 for details). After initial screening and with a finalized list of SMEs, the authors asked the concerned person of the selected SMEs to indicate the individuals for data collection. Those who were identified by the concerned authorities were then contacted to participate in the survey.

Table 1.

Sample profile (N = 236).

The authors carefully dealt with the issue of common method bias. For this purpose, the authors were in line with the recommendation of Podsakoff et al. [79] to collect the data from different respondents. The authors, therefore, developed a dyad of leader and follower from selected SMEs. The authors distributed questionnaires to followers (employees with non-management positions) containing the information for variables, CSR, and authentic leadership. The data for IWB were collected from leaders (Managers or Supervisors); it was logical and seemed appropriate to collect the data for IWB from corporate leaders because in most SMEs the leaders work in close coordination with workers, and hence they can easily observe the innovative behavior of their subordinates. Initially, the authors distributed 700 surveys (350 for leaders and 350 for followers) among the respondents of selected SMEs, and finally, the authors received 472 filled matched questionnaires (i.e., 236 supervisor–subordinate dyads) which were useful for data analysis. The authors collected the data from the selected SMEs after identifying the supervisors and the workers from 21 SMEs in Wuhan city. In this regard, the spokespersons of the respective SMEs were the source of information in identifying the supervisors and the workers in a specific unit, floor, or department.

Table 1 presents detailed information regarding the demographics of the sample and the type of industries.

3.2. Measures and Handling of Social Desirability

This study employed the existing scales to measures the constructs. Thus, the issue of validity and reliability was non-existent here because adapted scales have their pre-established validity and reliability. The scale of IWB was adapted from Janssen [80]; this scale comprised a total of nine items and is widely used by various researchers to measure the innovative behavior of employees at the workplace [17,81,82]. A three-item scale of employee’s CSR perception was taken from the study of Fombrun et al. [83]. This scale is also used by extant researchers to measure employees’ CSR perceptions [84,85]. The authors adapted the scale of authentic leadership (sixteen-item) from Walumbwa et al. [86] which is extensively used by previous researchers to measure authentic leadership [87,88,89]. The constructs were reflective because all the latent constructs were operationalized based on some indicator. These indicators (items) were used to reflect and not to build the construct. Thus these constructs were reflective as mentioned in the studies of Finn and Wang [90], Diamantopoulos and Siguaw [91], and Edwards and Bagozzi [92]. A five-point Likert scale was employed by the authors to collect the data. The questionnaire statements are shown in Appendix A.

To address the issue of social desirability, the authors took several measures. For example, the survey items were randomly scattered throughout the questionnaire. The authors did this to break any sequence of answering the responses by the respondents. This step is also helpful in dealing with the likelihood of any liking and disliking for a particular construct. Likewise, the instrument was checked for accuracy and suitability by experts in the field. This step is necessary to address any ambiguity or confusion in any item statement due to complex or dual-meaning words. Likewise, the authors requested the respondents for their true response so that the findings generated by their input may reflect the reality [93,94].

4. Results

4.1. Convergent Validity, Factor Loadings, and the Reliability Analyses

The SME sector in China is involved in different CSR-related activities, for example, some organizations in this sector are working for community building through supporting the community in the field of education and health. Likewise, some organizations are taking CSR initiatives on charity-related bases, for example, helping the poor or donating to some welfare institutions, etc. SMEs also relate their CSR activities with employees and work for their betterment. In different instances, SMEs support their employees in many ways (different financial support plans and other benefits, improving the working environment, etc.).

The data analysis phase was started with exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in SPSS to validate if the item loadings for all variables were appropriate (λ > 0.5). To do this, the authors used principal component analysis (PCA) by using varimax rotation. The initial results reveal that three items were suffering from poor item loadings. These included two items of authentic leadership (ALS2 = 0.28, ALS6 = 0.19) and innovative work behavior (IWB3 = 0.09). Thus, the authors deleted these items and carried out the data analysis with the remaining items. The item loading extracted from EFA is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Item loadings, convergent validity, and reliability results.

Next, the authors tested for the results of average variance extracted (AVE) to establish convergent validity and composite reliability (C.R) to establish inter-item consistency. To validate convergent validity, the general criterion is that if AVE for a construct is greater than 0.5, then the criterion for convergent validity is satisfied [95]. To measure AVE for a construct, the authors first of all calculated item loadings (λ) for each item and then took the sum of the square of these loadings (∑λ2) dividing by the number of items. As an example, there were three items of CSR, and the sum of loading square was 1.876 which was divided by 3 (number of items) that resulted in 0.625 as an AVE value.

After validating convergent validity, the authors calculated C.R by using the formula C.R = (∑λ)2/[((∑λ)2 + ∑(1 − λ2)] for each construct. Following the guidelines of Fornell and Larcker [95], the authors checked each construct’s C.R value (C.R should be greater than 0.6) and revealed that each construct meets the criterion of C.R. Thus, there is no issue of C.R in scaled items of the current survey. These results are reported in Table 2 in detail.

Table 3 presents the results of correlation, discriminant validity, and model fit indices (MFIs). In this aspect, the correlation values for all constructs were positive and significant which means each construct is positively correlated with the other construct. As a case, one can see that the correlation value between CSR and ALS is 0.21 which is positive and significant. To assess discriminant validity (DSV), the authors took a square root of AVE (SQAVE) for a construct and compared it with correlation values. The general rule here is that if the value(s) of correlation is less than the value of SQAVE, then it is confirmed that the criterion of DSV is satisfied and the items of one construct are dissimilar with the items of other constructs in comparison. To explain further, the value of correlation between CSR and ALS is 0.21 which is far less as compared to the value of SQAVE (0.758), and hence, discriminant validity is maintained in the current scenario. Lastly, the results of MFI are also presented in Table 3 to assess if there is a fit between theory and the data. In this regard, the authors checked the values of different MFIs against their acceptable range (given in Table 3) and revealed that there is no issue in any MFI value (χ2/df = 3.831, RMSEA = 0.054, NFI = 0.961, CFI = 0.936, IFI = 0.930, TLI = 0.959, GFI = 0.933).

Table 3.

Correlation, discriminant validity, and MFI.

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

To validate different hypotheses of the current study, the authors used structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS software. SEM analysis is a co-variance-based analysis approach that is very popular among contemporary researchers as it has advanced-level tools to deal with complex research models [96,97,98]. The hypotheses testing was done in two sections using SEM. In the first section, the authors analyzed the direct effect model in which no mediator was introduced. The authors conducted the direct effect model to validate Hypotheses 1 and 2 (H1 and H2). The results of structural model confirmed that both H1 and H2 are accepted (β1 = 0.31, β2 = 0.33, p < 0.05). Hence, based on these results (Table 4), H1 and H2 of the current study are proved and accepted. The first stage of SEM started with checking the direct effect analysis in which there was no intervention of any mediator in the model. The results of the direct effect model are shown in Table 4. As per these results, the direct effect model produced significant results. These results confirmed that the first two hypotheses H1 and H2 of the current survey are supported. These outcomes were declared on the basis of beta estimates and p-values (β1 = 0.31, β2 = 0.33, p < 0.05). The results further validated that the effect of SL on EIB is stronger as compared to the effect of CSR-E on EIB. Moreover, the model fit indices were also significant in this regard (χ2/df = 2.173, RMSEA = 0.043, NFI = 0.968, CFI = 0.945, IFI = 0.940, TLI = 0.962, GFI = 0.943).

Table 4.

The results for Hypotheses 1 and 2.

The second section of SEM analysis was conducted by introducing ALS as the mediating variable (Table 5). To do this, the bootstrapping technique was applied which is more advanced and powerful as compared to the traditional Baron and Kenny [99] technique for mediation analysis. During the bootstrapping process, the authors used a large bootstrapping sample of 2000 and analyzed the mediation results. The output of the mediation analysis revealed that there is a partial mediation effect of ALS between CSR and IWB. It is worth noticing that the partiality of mediation was established based on the reduced beta value which was originally β1 = 0.31, but after the inclusion of mediator (ALS), it was dropped to β3 = 0.091, confirming that there is partial mediation effect of ALS between CSR and IWB (χ2/df = 1.861, RMSEA = 0.038, NFI = 0.980, CFI = 0.966, IFI = 0.961, TLI = 0.978, GFI = 0.964). Thus, all three hypotheses of the current survey are approved.

Table 5.

Mediation and moderation results for H3.

5. Discussion and Implications

The empirical results of the current study support all three hypotheses (H1, H2, and H3), and hence, it is proved that CSR directly and indirectly (through authentic leadership) influences IWB positively. Furthermore, the results also prove that authentic leadership mediates the relationship between CSR and IWB in the SME sector of China. The respondents of the survey confirmed that both CSR and the authenticity of their leader help motivate them to display their innovative capability at the workplace. The respondents further validated that CSR activities of their organization promote a sense of caring, transparency, honesty, and trust in them. Hence, due to the supportive and caring work environment, the employees feel the motivation to serve their organization beyond their formal working boundary. Therefore, they are urged to engage themselves in innovative activities to find new business solutions. The theory of social role is also helpful here to explain this proposed relationship in a way that the CSR engagement of an organization inculcates among employees that their organization is not only concerned with profit maximization but also wants to promote community and the environment. This extra-role of the organization is well observed by the employees, and they also learn this on their part. Consequently, the employees also think that they should support their organization by performing extra-roles, one of such behaviors is innovative work behavior. This finding of the current study is in line with several previous researchers [49,100,101,102,103,104].

The empirical results also advocate that authentic leadership is a style of leadership that promotes workplace innovation. In this regard, the respondents confirmed that the leadership style is an influential factor to induce their innovation performance. When employees of an organization find that their leader (authentic leader here) is supportive and helping toward them, they feel encouraged and perform their job willfully. Similarly, the authenticity of a leader promotes openness in an organization, and hence the employees are encouraged to share their novel ideas with their leader to perform a task in a new way. Furthermore, the workforce under an authentic leader is given independence and freedom in decision making, and common logic suggests that when workers are encouraged and empowered in decision making, they are expected to think about new and innovative ways. This argument of the current study is also supported by different researchers in that independence and empowerment in decision making promote IWB [105,106,107]. Following the theory of social role, the authors’ argument here is that an authentic leader practices authenticity at the workplace under which he or she promotes openness, morality, and a supportive organizational environment. Employees as observers learn these characteristics of their leader and put every attempt to support their organization by performing different extra-role behaviors such as IWB. Moreover, an authentic leader boosts the confidence level of their employees and urges them to take risks without the fear of failing. In response, the employees become risk-takers, and they take risks for the betterment of their organization and without the fear that if they fail, they will be punished. All this process encourages them to be engaged in IWB. Different extant research has also established that authentic leadership style influences IWB [22,23,68,71,78,88].

This study adds to the existing organizational literature in many ways. For instance, the current study attempted to build a relationship of authentic leadership with workplace innovation. In prior literature, this relationship is still vague, and hence this study enriches extant literature by validating that authenticity in leadership is related to the innovative work behavior of employees. In like manner, this study also adds to the existing literature on CSR by arguing that CSR activities of an organization can encourage the employees to display their innovative capabilities. Prior CSR literature has largely explored CSR for different organizational outcomes such as organizational performance [108], organizational commitment [109], quality management [110], etc. However, prior studies have least considered CSR to link with employees’ innovative work behavior. Thus the current survey adds to the existing literature on CSR from the perspective of workplace innovation. Another important addition of the current study is that it explores the relationship of CSR, authentic leadership, and workplace innovation from the perspective of the SME sector of an emerging (China) economy.

The practical implications of the current study are also important for professionals from the SME sector of China. In this vein, the current study attempted to change the current viewpoint of policymakers toward CSR. Currently, the majority of SMEs in China follow some CSR principles only to abide by state laws. Furthermore, it is also a prevailing opinion among different SMEs that CSR is an expensive volunteer activity and thus it should be put on the shoulders of large businesses. This study was an attempt to change this traditional mindset toward CSR as this study introduced CSR as an enabler of workplace innovation. The importance of workplace innovation is critical for every business sector for survival and growth due to tough competitive environments. The SME sector of China needs to realize that they can survive and better compete with their rivals if they are capable of innovating their business processes, and CSR in this regard is a strategic enabler of workplace innovation. Furthermore, the SME professionals need to recognize that they belong to small and medium-sized businesses and their resources are sparse as compared to large businesses. Thus they have a definite resource deficit to buy costly innovations in the form of up-to-date technology, equipment, and machinery. In this regard, the employees of an SME can serve as a cheap and effective source of innovation if they are managed appropriately. Another practical importance of the current study is that it highlights the importance of leadership in encouraging employees working in different SMEs to display their innovative capability in the workplace. The study contends that, through a decent leadership style (authenticity), the organization can develop an environment in which the employees work fearlessly and they want to take risks for better organizational outcomes. Hence, the professionals from the SME sector of China are encouraged to promote authenticity in leadership if they want their workforce as a source of innovation. Lastly, the policymakers need to realize that in a volatile environment, innovation is a key to success and survival as innovation provides a solid base for competitive advantage and employees are the individuals who provide input for workplace innovation.

Limitations and Potential Research Directions

Though the existing study offers adequate grounds to accept the proposed research model and relationships among variables, some limitations will need to be addressed by future researchers. The first limitation of this analysis is that it attempts to explain employees’ innovative behavior through the lens of CSR and authentic leadership. Although these variables are important to consider in explaining the behavior of employees, it is worth mentioning here that human behavior is quite complex to understand. Hence, future researchers are suggested to consider other important variables in the proposed model of this study. For example, psychological contract, job design, and organizational justice may be important variables for future researchers to better explain employee innovative behavior. Likewise, this research study only considered SMEs that were located in Wuhan city, and thus the geographical concentration increases questions regarding the generalizability of this research. As a way to deal with this limitation, the prospective researchers are encouraged to consider a diverse sample of SMEs from different cities. Another limitation of this analysis is that it used cross-sectional data, and hence forecasting causality based on cross-sectional data entails specific risks. Thus, future studies will need to consider the longitudinal data design.

Author Contributions

All of the authors contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing and editing of the original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

| Questionnaire items |

| Corporate social responsibility |

| 1 This is a company that really cares about its employees. |

| 2 This company contributes a lot the communities in which it operates. |

| 3 This is an environmentally responsible company. |

| Innovative behavior |

| How often does this worker perform the following work activities: |

| 1 Acquiring approval for innovative ideas. |

| 2 Searching out new working methods, techniques, or instruments. |

| 3 Transforming innovative ideas into useful applications. |

| 4 Introducing innovative ideas in a systematic way. |

| 5 Making important organizational members enthusiastic for innovative ideas. |

| 6 Generating original solutions to problems. |

| 7 Creating new ideas for improvements. |

| 8 Mobilizing support for innovative ideas. |

| 9 Thoroughly evaluating the application of innovative ideas. |

| Authentic leadership |

| 1 My leader can list his/her three greatest weaknesses. |

| 2 My leader’s actions reflect his/her core values. |

| 3 My leader seeks others’ opinions before making up his/her own mind. |

| 4 My leader openly shares his/her feelings with others. |

| 5 My leader can list his/her three greatest strengths. |

| 6 My leader does not allow group pressure to control him/her. |

| 7 My leader listens closely to the ideas of those who disagree with him/her. |

| 8 My leader lets others know who he/she truly am as a person. |

| 9 My leader seeks feedback as a way of understanding who he/she really am as a person. |

| 10 Other people know where my leader stand on controversial issues. |

| 11 My leader does not emphasize his/her own point of view at the expense of others. |

| 12 My leader rarely presents a “false” front to others. |

| 13 My leader accepts the feelings he/she has about himself/herself. |

| 14 My leader’s morals guide what he/she does as a leader |

| 15 My leader listens very carefully to the ideas of others before making decisions |

| 16 My leader admits my mistakes to others. |

References

- Kouzes, J.M. The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations; Jossey-Bass A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, W.L.; Karam, E.P.; Alvesson, M.; Einola, K. Authentic leadership theory: The case for and against. Leadersh. Q. 2021, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, C.; Gardner, W.; Claeys, J.; Vangronsvelt, K. Using theory on authentic leadership to build a strong human resource management system. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2018, 28, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, T. The Leadership of an Authentic King. In Transparent and Authentic Leadership; Winston, B.E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, R.A. Authentic leadership through an ethical prism. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2017, 19, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Farid, T.; Khan, M.K.; Zhang, Q.; Khattak, A.; Ma, J. Bridging the gap between authentic leadership and employees communal relationships through trust. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emuwa, A.; Fields, D. Authentic leadership as a contemporary leadership model applied in Nigeria. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2017, 8, 296–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, D.; Smolović Jones, O.; Grint, K. ‘No more heroes’: Critical perspectives on leadership romanticism. Organ. Stud. 2018, 39, 1625–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.M.; Gong, T.; Hughes, C. Linking leader and gender identities to authentic leadership in small businesses. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 32, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomkins, L.; Nicholds, A. Make me authentic, but not here: Reflexive struggles with academic identity and authentic leadership. Manag. Learn. 2017, 48, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foghani, S.; Mahadi, B.; Omar, R. Promoting clusters and networks for small and medium enterprises to economic development in the globalization era. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 2158244017697152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangus, K.; Slavec, A. The interplay of decentralization, employee involvement and absorptive capacity on firms’ innovation and business performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 120, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirvis, P.; Googins, B. Engaging employees as social innovators. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 25–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeij, P.; Rus, D.; Pot, F.D. Workplace Innovation: Theory, Research and Practice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Lee, M.-J. Absorptive capacity, knowledge sharing, and innovative behaviour of R&D employees. Technol. Anal. Strat. Manag. 2017, 29, 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Pian, Q.Y.; Jin, H.; Li, H. Linking knowledge sharing to innovative behavior: The moderating role of collectivism. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1652–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanker, R.; Bhanugopan, R.; Van der Heijden, B.I.; Farrell, M. Organizational climate for innovation and organizational performance: The mediating effect of innovative work behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017, 100, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos-Nehles, A.C.; Veenendaal, A.A. Perceptions of HR practices and innovative work behavior: The moderating effect of an innovative climate. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 30, 2661–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Xue, W.; Li, L.; Wang, A.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Leadership style and innovation atmosphere in enterprises: An empirical study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 135, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.A.; Pihl-Thingvad, S. Managing employee innovative behaviour through transformational and transactional leadership styles. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 918–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alheet, A.; Adwan, A.; Areiqat, A.; Zamil, A.; Saleh, M. The effect of leadership styles on employees’ innovative work behavior. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semedo, A.S.; Coelho, A.; Ribeiro, N. Authentic leadership, happiness at work and affective commitment. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithikrai, C.; Suwannadet, J. Authentic leadership and proactive work behavior: Moderated mediation effects of conscientiousness and organizational commitment. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 13, 94–106. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, S.; Alizadeh, A.; Dooley, L.M.; Zhang, R. The effects of authentic leadership on trust in leaders, organizational citizenship behavior, and service quality in the Chinese hospitality industry. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 40, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B.-K.; Jo, S.J. The effects of perceived authentic leadership and core self-evaluations on organizational citizenship behavior. Lead. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 463–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasab, A.H.; Afshari, L. Authentic leadership and employee performance: Mediating role of organizational commitment. Lead. Organ. Dev. J. 2019, 40, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, V.-Y.; Ho, T.-S. Authentic leadership and employee engagement: The role of employee well-being. Hum. Syst. Manag. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A. Bound to fail? Exploring the systemic pathologies of CSR and their implications for CSR research. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 1303–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, A.; Khosrowpour, S. Corporate social responsibility: Past, present, and success strategy for the future. J. Serv. Sci. JSS 2017, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundtable, B. Business Roundtable Redefines the Purpose of a Corporation to Promote ‘an Economy that Serves all Americans’. Available online: https://www.businessroundtable.org/business-roundtable-redefines-the-purpose-of-a-corporation-to-promote-an-economy-that-serves-all-americans (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- García-Sánchez, E.; García-Morales, V.J.; Martín-Rojas, R. Analysis of the influence of the environment, stakeholder integration capability, absorptive capacity, and technological skills on organizational performance through corporate entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 345–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.M.; Muñoz, M.J.; Moneva, J.M. Revisiting the relationship between corporate stakeholder commitment and social and financial performance. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Chung, Y. The effects of corporate social responsibility on firm performance: A stakeholder approach. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, A.; Androniceanu, A.; Lazaroiu, G. An integrated psycho-sociological perspective on public employees’ motivation and performance. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapragasam, P.; Raya, R. HRM and employee engagement link: Mediating role of employee well-being. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, A.C.H.; Newman, J.I.; Ferris, G.R.; Perrewé, P.L. The antecedents and consequences of positive organizational behavior: The role of psychological capital for promoting employee well-being in sport organizations. Sport Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. Number of Small to Medium-Sized Enterprises in China from 2012 to 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/aboutus/our-research-commitment (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Bandura, A.; McClelland, D.C. Social Learning Theory; Englewood Cliffs Prentice Hall: Plano, TX, USA, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bertassini, A.C.; Zanon, L.G.; Azarias, J.G.; Gerolam, M.C.; Omettoo, A.R. Circular Business Ecosystem Innovation: A guide for mapping stakeholders, capturing values, and finding new opportunities. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 27, 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, B. Revisiting who, when, and why stakeholders matter: Trust and stakeholder connectedness. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, G.K.; Brewster, C.J.; Collings, D.G.; Hajro, A. Enhancing the role of human resource management in corporate sustainability and social responsibility: A multi-stakeholder, multidimensional approach to HRM. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendafiova, S.; Ziakas, V.; Sparvero, E. Linking corporate social responsibility in sport with community development: An added source of community value. Sport Soc. 2017, 20, 938–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Tang, M.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, J. How Toxic Workplace Environment Effects the Employee Engagement: The Mediating Role of Organizational Support and Employee Wellbeing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani-Melhem, S.; Zeffane, R.; Albaity, M. Determinants of employees’ innovative behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1601–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-C.; Mai, Q.; Tsai, S.-B.; Dai, Y. An empirical study on the organizational trust, employee-organization relationship and innovative behavior from the integrated perspective of social exchange and organizational sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, O.; Islam, J.U. Influence of CSR-specific activities on work engagement and employees’ innovative work behaviour: An empirical investigation. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 3054–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocquet, R.; Le Bas, C.; Mothe, C.; Poussing, N. Strategic CSR for innovation in SMEs: Does diversity matter? Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 101913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; He, J.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. Effects of tourism CSR on employee psychological capital in the COVID-19 crisis: From the perspective of conservation of resources theory. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Akhouri, A. CSR perceptions and employee creativity: Examining serial mediation effects of meaningfulness and work engagement. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, W. How Walmart Associates Put the ‘U’ and ‘I’ into Sustainability. Available online: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/how-walmart-associates-put-u-and-i-sustainability#:~:text=MSP%20launched%20in%202010%2C%20urging,the%20most%20out%20of%20life (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- Kör, B.; Wakkee, I.; van der Sijde, P. How to promote managers’ innovative behavior at work: Individual factors and perceptions. Technovation 2021, 99, 102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumusluoglu, L.; Karakitapoğlu-Aygün, Z.; Scandura, T.A. A multilevel examination of benevolent leadership and innovative behavior in R&D contexts: A social identity approach. J. Lead. Organ. Stud. 2017, 24, 479–493. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, R.M. Is boreout a threat to frontline employees’ innovative work behavior? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 574–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Benson, J. When CSR is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1723–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, S.; Sadaf, R.; Popp, J.; Vveinhardt, J.; Máté, D. An examination of corporate social responsibility and employee behavior: The case of Pakistan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, K. How and when do employees identify with their organization? Perceived CSR, first-party (in) justice, and organizational (mis) trust at workplace. Pers. Rev. 2018, 47, 1152–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Donia, M.B.; Shahzad, K. Impact of corporate social responsibility attributions on employees’ creative performance: The mediating role of psychological safety. Ethics Behav. 2019, 29, 490–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L. Authentic leadership development: Getting to the root of positive forms of leadership. Lead. Q. 2005, 16, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sui, Y.; Luthans, F.; Wang, D.; Wu, Y. Impact of authentic leadership on performance: Role of followers’ positive psychological capital and relational processes. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidani, Y.M.; Rowe, W.G. A reconceptualization of authentic leadership: Leader legitimation via follower-centered assessment of the moral dimension. Lead. Q. 2018, 29, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einola, K.; Alvesson, M. The perils of authentic leadership theory. Leadership 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alilyyani, B.; Wong, C.A.; Cummings, G. Antecedents, mediators, and outcomes of authentic leadership in healthcare: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2018, 83, 34–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwanto, A.; Asbari, M.; Hartuti, H.; Setiana, Y.N.; Fahmi, K. Effect of Psychological Capital and Authentic Leadership on Innovation Work Behavior. Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2021, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Fuller, B.; Hester, K.; Bennett, R.J.; Dickerson, M.S. Linking authentic leadership to subordinate behaviors. Lead. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.-D.; Zhao, S.-K.; Li, C.-R.; Lin, C.-J. Authentic leadership and employee creativity: Testing the multilevel mediation model. Lead. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 482–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arici, H.E. Perceived supervisor support and turnover intention: Moderating effect of authentic leadership. Lead. Organ. Dev. J. 2018, 39, 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novitasari, D.; Siswanto, E.; Purwanto, A.; Fahmi, K. Authentic Leadership and Innovation: What is the Role of Psychological Capital? Int. J. Soc. Manag. Stud. 2020, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.-M.; Chen, T.-J. Inspiring prosociality in hotel workplaces: Roles of authentic leadership, collective mindfulness, and collective thriving. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 31, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, H.; Han, K.; Ryu, E. Authentic leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment: The moderating effect of nurse tenure. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 1655–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R.; Akhouri, A. CSR Attributions, Work engagement and Creativity: Examining the role of Authentic Leadership. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management, Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2018; p. 16800. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.d.M.; Perramon, J.; Bagur-Femenias, L. Leadership styles and corporate social responsibility management: Analysis from a gender perspective. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; O’Brien, K.E.; Dawson, K.M.; Hardiman, M.E. Mechanisms of corporate social responsibility: The moderating role of transformational leadership. Ethics Behav. 2018, 28, 644–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-C.; Chen, J.-Y.; Wang, M.-J.; Chen, C.-Y. The impact of inclusive leadership on employees’ innovative behaviors: The mediation of psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Dhar, R.L.; Handa, S.C. Authentic leadership and its impact on creativity of nursing staff: A cross sectional questionnaire survey of Indian nurses and their supervisors. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 63, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, O. Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2000, 73, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, S.C.; Zhang, X.A.; Morgeson, F.P.; Tian, P.; van Dick, R. Are you really doing good things in your boss’s eyes? Interactive effects of employee innovative work behavior and leader–member exchange on supervisory performance ratings. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Liu, B.; Wei, X.; Hu, Y. Impact of inclusive leadership on employee innovative behavior: Perceived organizational support as a mediator. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fombrun, C.J.; Gardberg, N.A.; Sever, J.M. The Reputation Quotient SM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. J. Brand Manag. 2000, 7, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rettab, B.; Brik, A.B.; Mellahi, K. A study of management perceptions of the impact of corporate social responsibility on organisational performance in emerging economies: The case of Dubai. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Bartikowski, B. Exploring corporate ability and social responsibility associations as antecedents of customer satisfaction cross-culturally. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Avolio, B.J.; Gardner, W.L.; Wernsing, T.S.; Peterson, S.J. Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, N.; Duarte, A.P.; Filipe, R.; Torres de Oliveira, R. How authentic leadership promotes individual creativity: The mediating role of affective commitment. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2020, 27, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.P.; Dhar, R.L. Authentic leadership and extra role behavior: A school based integrated model. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 684–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levesque-Côté, J.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Morin, A.J. New wine in a new bottle: Refining the assessment of authentic leadership using exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM). J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 611–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, A.; Wang, L. Formative vs. reflective measures: Facets of variation. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 2821–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Bagozzi, R.P. On the nature and direction of relationships between constructs and measures. Psychol. Methods 2000, 5, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mahmood, A.; Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Iqbal Khan, G.; Ullah, Z. Sustainability as a “New Normal” for Modern Businesses: Are SMEs of Pakistan Ready to Adopt It? Sustainability 2021, 13, 1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; waqas Kamran, H.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility at the Micro-Level and Environmental Performance: The Mediating Role of Employee Pro-Environmental Behavior and the Moderating Role of Gender. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S. Bootstrapping and PLS-SEM: A step-by-step guide to get more out of your bootstrap results. Eur. Manag. J. 2016, 34, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streukens, S.; Leroi-Werelds, S.; Willems, K. Dealing with nonlinearity in importance-performance map analysis (IPMA): An integrative framework in a PLS-SEM context. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 367–403. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, M.B.; Nordin, M.B.; Razzaq, A.B.A. Structural Equation Modelling Using AMOS: Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Taskload of Special Education Integration Program Teachers. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, S.; Khan, A.; Hayat, H.; Panniello, U.; Alam, M.; Farid, T. Do hotel employees really care for corporate social responsibility (CSR): A happiness approach to employee innovativeness. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Rehman, Z.U.; Haider, M.; Ullah, M. Perceived corporate social responsibility and innovative work behavior: The role of employee volunteerism and authenticity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1865–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, L.; Chan, S.F. Corporate responsibility for employees and service innovation performance in manufacturing transformation. Career Dev. Int. 2019, 24, 580–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-B.; Zhang, G.-Q.; Wu, T.-J.; Peng, C.-L. Employee’s Corporate Social Responsibility Perception and Sustained Innovative Behavior: Based on the Psychological Identity of Employees. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; El-Kassar, A.-N.; Abdul Khalek, E. CSR, Entrepreneurial Orientation, Citizenship, and Innovative Work Behavior. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management, Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2020; p. 22108. [Google Scholar]

- Totterdill, P.; Exton, R. Defining workplace innovation. Strateg. Dir. 2014, 30, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saray, H.; Patache, L.; Ceran, M.B. Effects of employee empowerment as a part of innovation management. Econ. Manag. Financ. Mark. 2017, 12, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Demircioglu, M.A. The effects of empowerment practices on perceived barriers to innovation: Evidence from public organizations. Int. J. Public Adm. 2018, 41, 1302–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Misra, M. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Organizational Performance: The moderating effect of corporate reputation. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.-J.; Nurunnabi, M.; Kim, T.-H.; Jung, S.-Y. The influence of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: The sequential mediating effect of meaningfulness of work and perceived organizational support. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Caroli, M.G.; Cappa, F.; Del Chiappa, G. Are you good enough? CSR, quality management and corporate financial performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).