Abstract

The purpose of this research is to find if the stakeholders involved in rural tourism (primary producers of ecological goods, tourism service providers, and tourists, as carriers of demand for tangible products and ecological services) are concerned with integrating principles and values of sustainable tourism through permaculture and downshifting, and how these two phenomena might become sources for sustainable development in rural areas. To achieve this purpose, qualitative research was conducted among tourism producers, intermediaries, and tourists from the Brașov region–one of the most important touristic areas of Romania and, also, an important region with rural tourism destinations. The results revealed that there is a particular preoccupation regarding permaculture and downshifting, and they might contribute to the local development of rural tourism areas. The novelty elements brought by this research are synthesized in a matrix where permaculture and downshifting were presented as important sources for the sustainable development of tourism in rural areas.

1. Introduction

Tourism has many positive effects and influences directly and indirectly to the economic development of the areas that have tourism sights. Tourism may, also, contribute to the development of areas that are not rich in economic resources, but with natural and anthropoid resources [1]. According to OECD (The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), tourism will follow four major development trends by 2040: (1) evolving visitor demand, (2) sustainable tourism growth, (3) enabling technologies, and (4) travel mobility [2]. In terms of changes in the profile of tourists, there are also drastic changes that will affect the evolution of this field in the medium and long term. On the one hand, it is about demographic change, which, especially in European countries, is becoming apparent. Their impact on the economy can bring about significant changes in business models. On the other hand, it is even about changing tourists in terms of how they choose to spend their lives and how they want to get old. Today’s tourists are increasingly concerned about their health, the place they choose to spend their holidays, the shift from mass tourism to the niche [3]. Some of the most popular tourist locations in Europe are the big cities. It can be appreciated that these are compulsory destinations for tourists, and they can be considered advertisements for a country. Cities and metropolitan areas are important for tourism because they represent residences of national or regional governments, they possess monuments and important buildings; they are places that host important events and various ceremonies; they are businesses and commercial centers, they host nightlife and provide multiple possibilities for fun. They are preferred because they provide a large variety of entertainments and full services in a relatively small area.

During the last decade, the tourism industry has undergone important transformation stages, because of a complex of economic, social, and cultural factors. Lately, the attractiveness of rural tourism has increased. All of these have led to the separation of an important part of the tourist activities from the area of standardization of products, services, behaviors, and assumptions considered typical for tourism and the orientation towards the horizons of return to nature, with everything that involves. It can be assumed that most tourists go to the countryside to take a break from the city bustle, but in the countryside, they require appropriate comfort-not only bathing and flush toilets, but also swimming pools, whirlpools, internet connection, parking spaces, and the like. In this situation, rural municipalities must decide to become ecologically oriented and may benefit from being specific, while others will focus on commercial tourism. Therefore, we consider that downshifting and permaculture may represent opportunities to address these new challenges in rural tourism development.

Considering downshifting to sustainable living, deciding what is a good lifestyle is the first step to finding, planning, and developing the ideal self-sufficient small farm [4]. Permaculture, ancient traditional farming, and nature herself is the base of this kind of farming. The downshifting principles are applied in every aspect of a downshifting follower’s life.

Rural tourism begins to be more and more appreciated by tourists from all over the world. Inside this form of tourism, the phenomenon of downshifting [5] can harmonize, defined as a social behavior or trend in which individuals lead a simple life to escape materialism and obsession to reduce the level of stress that can accompany this obsession. Permaculture, ancient traditional farming, and nature herself is the base of this kind of farming. As Holmgren [6] mentions, they tend to choose to retrofit instead of new construction, allowing permaculture downshifters to focus on food production, water systems, home-based livelihoods, and community resilience rather than sinking all their efforts into state-of-the-art eco-housing. The downshifting movement is marked, painstakingly around the notions of “penury” of time and loss of connection with the world and with yourself. In rural areas, tourists are invited to alternate uneasy peasant labor and serene outdoor recreation. This fact allows tourists to appreciate the holiday in a much deeper and sensitive way, giving them the possibility to return to origins which is the basis of downshifting. Rural tourism is a kind of tourism, which presupposes rest in the rural wilderness, far from the city rush and noise, where you can experience a journey imbued characterized by a stay in one place for a long period of time and where you can see things that are close to your soul.

However, the relationship between tourism, permaculture, downshifting, and rural development is complicated. There seems to be no single path and rural communities should choose the direction in which to focus their development regarding the potential of tourism.

Therefore, this research aims to identify to what extent permaculture and downshifting are perceived by local stakeholders as sources of development through rural tourism in Brașov County, Romania. In this sense, the authors have established the problem statement as to what extent involved stakeholders are familiar with/have knowledge of the concepts of permaculture and downshifting and whether they use them in rural tourism activities. Therefore, the researchers conducted qualitative research with the aim of answering the following questions: How are permaculture and downshifting perceived as tools in rural tourism?; In what particular way permaculture and downshifting have an impact on tourism activities in the rural tourism area of Brașov County?; What is the importance of other elements that might influence rural tourism, especially in connection with permaculture and downshifting?; What are the specific elements in organizing the rural tourism networks?

The research brings some elements of novelty, by trying to identify a connection between downshifting and permaculture (both in theory and practice), to what extent they might contribute to rural development and, also, by integrating the elements that define permaculture and downshifting as sources of tourism development in rural areas from Brașov County.

The present paper is structured into five sections. The first section introduces the concept of rural tourism development and the potential influence that permaculture and downshifting might have on it. The second section is dedicated to the literature review, while the third section describes the research context and methodology. The fourth section presents the main findings of the research and the fifth section includes the researchers’ own interpretation and integration of the results. Finally, a series of conclusions are highlighted, as well as implications for different categories of stakeholders from rural destinations and the main limitations of the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Importance of Rural Tourism in the Development of Rural Areas

Conceptual approaches and practice in tourism areas highlight an essential aspect which consists in the existence of a harmonious relationship with the environment that is necessary to create tourism services, including the related tangible elements, with direct effects on maintaining and improving the tourist experience. At present, the well-known expression “a beautiful and friendly destination” is no longer enough, as tourists want more and more to visit places that disconnect them from the usual rhythm of life, to awaken their interest and passion, to captivate them and to entertain them, to offer education and lasting memories–all of them in the context of environmental care and respect for the resident population of the visited area.

Tourism is a driving force in rural development. Rural development can be operationalized at the level of the individual farm household. At this level, rural development emerges as a redefinition of identities, strategies, practices, interrelations, and networks [7]. Moreover, following Heal [8] and Weitzman [9], it is argued here that rural development can be enhanced, by achieving optimal diversity of economic activities in the rural communities. Tourism activities may become an excellent source of economic diversity in rural areas.

Rural tourism is not a new phenomenon in EU countries, such as Romania. It has been practiced for a long time either spontaneously or organized, as a tourism activity in the rural environment. In recent years, rural areas have undergone a significant social and economic change, largely due to the powerful restructuring processes imposed by globalization and, by the financial crisis [10,11,12,13] and, also, because of man’s actions, especially the over-exploitation of natural resources and unsustainable farming methods [14].

The role of tourism in rural areas is pivotal for the integration and Valorisation of territorial resources and it is strengthened by the capacity to promote local community participation in development processes. Capturing the distinctive feature of rural development, and its appeal in terms of tourism lies in knowing how to rethink drivers of development through specific actions, such as: promoting the coexistence of inclusive processes to regenerate social capital; building and strengthening existing networks between the rural territory and external areas (particularly between rural areas and urban centers); job creation; and, finally, economic growth. In the same way, a balanced model of rural development must also be based on coherence between the rural area’s ability to attract external resources and its ability to generate internal opportunities, ensuring that actions for rural development meet the collective needs of the territory [15].

From an economic perspective, rural tourism has been regarded as an effective strategy for sustainable social and economic development [16]. Moreover, through tourism, rural villages have a chance to revitalize their communities by using and commodifying existing local resources [17]. So, tourism development is important for the rural space, both economically and socially. Thus, rural tourism contributes to the economic development of localities by means of the following [18]:

- achieving a tourism development policy on the short term, connected to other sector policies: agriculture, infrastructure, environment protection.

- becoming a support for new businesses and jobs which contributes to a new local and regional development.

- encouraging local traditional activities, especially handcrafts, but also those that can contribute to the development of specific commerce and new jobs.

- increasing income in the case of the inhabitants of rural areas generated using local resources, agricultural ecologic products for tourists’ consumption and the existing tourism potential.

- spurring the process of increasing life quality in the rural environment.

2.2. Permaculture and Downshifting, Sustainable Sources of Development in Rural Areas

In rural areas, there are specific tourism assets that can provide economic and social wealth, local experiences that tourists seek, as well as the spaces suitable for ecological tourism services, which leads to the holistic sustainable development of these areas through community-based tourism initiatives [19,20,21]. The purpose of these tourism assets is to provide regenerative economic and social wealth, but they also include environmental, ecological benefits. For these reasons, rural communities represent suitable places for permanent agriculture (permaculture) and downshifting,

Permaculture represents a holistic, environmentally friendly approach in designing and developing human settlements, assuming a harmonious and sustainable integration of landscapes and people [22]. The concept was introduced by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in the 1970 and it refers not only to a simple return to nature but also to a system of sustainable development based on natural principles, a way of using nature to increase the sustainability and quality of life [23]. As people and their livelihoods depend on the environmental health and productivity and their actions play a critical role in maintaining the health and productivity of the ecosystem [24,25,26], permaculture appears as a planned system that imitates the model and interactions established in nature by integrating sustainable management practices [27].

The ethics and principles of permaculture are transposed in a concise and comprehensive statement [28]. In the absence of a global ethical strategy regarding the environment, permaculture provides a convincing relationship between ethics and environmental wellbeing [29,30] through the three ethical orientations—earth care, human care, and fair action—, by setting some boundaries for consumption and by adapting those orientations to the research context, as follows: clean, ethical, and healthy [31].

The first ethics “earth care” (Clean) relates to all the aspects of permaculture. It focuses on the fact that ecosystems must be maintained based on the idea that human beings cannot develop harmoniously without a healthy Earth. The second ethical guideline “human care” (Ethical) refers to fulfilling the essential and existential requirements of people so that people can live their life at a reasonable quality. The third and the last ethical orientation, “fair action” (Healthy) is a combination of the first two ethical guidelines. According to this orientation, human beings must share all the renewable and non-renewable resources with other living organisms and save resources for future generations [32,33].

The term “downshifting” (known, also, as “off the grid”) emerged based on the refusal of people from Western societies to consider material values, hierarchical position, and money as defining elements of their existence, by preferring the idea of the quality of life, the intelligent way of spending the time, without becoming a slave to labor [34]. Its origin consists in the term of “voluntary simplicity”, a concept of religious origins appeared in the XIX-th century [35].

The first use of the term “downshifting” was attributed to Gerald Celente from the New York Trending Research Institute in 1994, who emphasized it as the most fundamental change in the way of life from the economic crisis [35]. Downshifting means connection–to life, family, food, and place–and, also, balance–in personal, work, family, spiritual, physical, and social life [36]. Until now, studies regarding downshifting are focused only on a small part of the population, so its representativity in the world is not known enough about [37].

Under the influence of this concern of slowdown, “finding an appropriate balance between work and personal life, embracing life with fewer financial resources, and opting for a simpler, greener and happier life” [38], more and more tourists from all around the world are currently looking for green destinations, supporting local communities, trying to reduce the negative impact on the environment. Once more here, for them, the idea is to enjoy the destination and make the most of it. By making the most of their stay in a destination, it is not said to collect a series of must-see buildings, running from a spot to another. These kinds of tourists’ holidays are to chill, relax and enjoy, feel the atmosphere of the destination they visit and immerse themselves completely in the local environment. This active global movement of individuals, groups and networks working to create the world they want, by providing for their needs and organizing their lives in harmony with nature is often linked with permaculture.

Permaculture is also a worldwide network and movement of individuals and groups working in both rich and poor countries on all continents. Largely unsupported by government or business, these people are involved in contributing to a sustainable future by reorganizing their lives and working around permaculture design principles. In this way, they are creating small local changes that act in the wider environment, through organic agriculture, appropriate technology, communities, and other movements for a sustainable world [39]. As tourists, people concerned about permaculture in their journey to downshifting are seeking the same philosophy of living in a sustainable economy. They search for “solution partnerships” instead of wild market competition. They appreciate models from nature, show and apply them into economics to create sustainable business models [40].

Permaculture challenges people to take responsibility for themselves and the economy that sustains them by designing and practicing permanent, sustainable cultural and agricultural systems created in accordance with environmental knowledge [41]. In some cases, this responsibility means taking into consideration the permaculture’s opportunities and providing a more holistic framework for moving organic agriculture certification forward, to stay ahead of the marketers and regulators driving a pack of more conventional food and forest product certification schemes [42].

Permaculture and downshifting are in interaction, and this aspect has been highlighted in the literature by the concept of permaculture downshifters [28]. A sustainable lifestyle, everyday life but also holidays, based on these two concepts, is a realistic, attractive, and powerful alternative to dependent consumerism.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Context-Brașov County, a Destination with Rural Tourism Potential

Romania is one of the countries with a remarkable rural potential, so rural tourism could become a country brand. The natural landscapes, the fresh air, the folk architecture, along with centuries-old customs and the gastronomy are just a few of the elements that make up the Romanian village [3].

Romania has an impressive rural heritage that could be successfully included in an attractive tourism product at the international level [43]. Romanian villages have always been an attraction for tourists and, for that reason, some attempts to organize tourism activity started in the 1960s. Romania represented a good example which showcases that a close relationship between agriculture, food and tourism might become the key to long-term development, profitable both for the involved stakeholders and for the local community. However, the lack of legislation and the low interest from the authorities have delayed the development of a specific infrastructure to support this niche. Thus, there were no coherent tourism products in rural areas until 1990 [44].

The Romanian rural household is the socio-economic unit for which the farming activity continues to be the main source of income or at least of supplementing incomes in the form of self-consumption; thus, most rural households overlap the agricultural household farms/peasant farms/small-sized farms [45]. In Romania, agriculture employs most rural inhabitants, and most farms are under 5 hectares. There are 3.9 million farm holdings in Romania, the majority of which are family farms of extensive semi-natural grassland pastoral systems and mixed farming systems [46]. These semi-natural small-scale farmed landscapes are of significant economic importance. For example, the 1 million holdings between 1 and 10 hectares (3.1 million hectares, 20% of Romania’s agricultural area) are classed as semi-subsistence farms producing for home consumption, local sales and for their extended families [46].

Romania is one of the Central and Eastern European countries for which the development of rural tourism is a viable option for sustainable economic development [2]. The importance of rural tourism for the Romanian economy is recognized in its national tourism strategies. To support the niche of rural tourism, some associations have been developed over the past three decades in Romania, such as The Romanian Villages Association (created in 1988–1989), The Romanian Mountain Development Federation (1990), The National Rural, Ecologic and Cultural Tourism Association from Romania (1994), The Configuration and Innovation Centre for Carpathian Development (CEFIDEC) (1994), The Romanian Agritourism Agency (1995), ANTREC (National Association for Rural, Ecological and Cultural Tourism in Romania) (2007) [47].

Romanian rural tourism is highlighted by its tourist resources and by the non-abolition of the Romanian villages that have kept their uniqueness, both in terms of architecture and habits. In addition, the Romanian rural area where this niche tourism activity is suitable is in the vicinity or even overlapping with the localities or areas that are listed on the UNESCO list of monuments. In 2019, Romania had six cultural sites listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List and 2 natural sites [48].

However, the right question in developing sustainable rural tourism in Romania is the danger of over-tourism. If the limits are exceeded, the devastation of the rural landscape or its change to semi-urbanized may mean the end of tourist interest. The example of Czech villages in the Romanian Banat is also interesting [49]. Thanks to the ethical and religious separation of the surrounding Romanian villages, the traditional way of life, which has already disappeared in the Czech Republic, has been maintained in these villages. Therefore, after 1990, these villages were frequently visited by Czech tourists. However, revenues from tourism have enabled locals to improve the appearance of their villages, the quality of living and to adapt to global trends, so the main motivation for visits has disappeared. It may therefore be that the development of tourism, albeit initially permaculturally, may eventually engulf itself or change into a commercial one.

Brașov County is one of the most varied areas in Romania in terms of tourism potential, due to its natural resources (nature monuments, natural reserves, national parks) as well as its cultural-historical resources (cities, castles, churches, museums, etc). The mountains and hills represent almost half of the county’s surface [50], this natural resource offering one of the most intact biodiversity in Europe, as well as the possibility of forming ecological tourism packages.

According to the Tourism Development Strategy in Brașov County 2020–2030, rural tourism is one of the most effective solutions for harmonizing tourism requirements with the principles of environmental protection and sustainable development. Also, Brașov County occupies the first place concerning accommodation capacities approved by ANTREC. The beauty of the rural area and cultural conservation make this area attractive for both domestic and international tourism. In recent years, rural tourism had a spectacular development [51]. According to the same source, rural tourism finds its followers among those interested in retreating in nature, the absence of mechanized environment and noise pollution, the return to authenticity and traditions. Agritourism is practiced especially around Bran villages (Fundata, Moieciu, Bran) and in Poiana Mărului—areas with a special natural, historical and tourist potential—as well as in the Săcele-Tărlungeni area, located in the immediate vicinity of Braşov. This specific form of rural tourism is based on providing—within the peasant household—accommodation, meals, leisure, and other services complementary to them, being practised by small landowners in rural areas, usually as a secondary activity. Guests can enjoy an authentic rural experience in the villages of Viscri, Crit, Bunesti: traditional architecture and furniture, natural food, traditions, crafts, and the unique experience of the rural lifestyle. Traditional Saxon guest houses retain the original furniture and authentic, traditional architecture with minimal interventions to achieve contemporary standards of hygiene (bathroom, etc.). In addition to fortresses and fortified churches, guests can enjoy nature, with various hiking trails available. For those who want a complete experience, visits to craftsmen, cart rides, waiting for the herd of cattle, and visits to the sheepfold are organized [52].

3.2. Research Methodology

The purpose of this research is to find if the stakeholders involved in rural tourism (primary producers of ecological goods, tourism service providers, and tourists, as carriers of the demand for tangible products and ecological services) are concerned with integrating the principles and values of sustainable tourism through elements that define permaculture and downshifting. With this aim, exploratory qualitative research was carried out, aimed at understanding the attitudes, opinions, beliefs and behaviors of individuals or groups of people regarding the importance of permaculture and downshifting characteristics in developing rural tourism and rural areas.

The choice for this type of research was determined by previous results obtained through similar research, as the qualitative research is adequate to the purpose and objectives formulated by several authors. For example, in a study on the perception of sustainability in Turkey, qualitative research highlighted the fact that companies do not pay attention to sustainability, even though they have stated that sustainability matters, without being considered an essential ingredient for the tourism industry [53]. In choosing the type and methods of research it was considered that qualitative research helps to appreciate the nature, history, and socio-cultural contexts of specific cases. Thus, as presented in the literature, qualitative research deals with a system of action rather than an individual or a group of individuals [54], facilitating research that seeks to understand the interactions of stakeholders more than their voice and perspective [55], the tourism offer being approached mainly as a cluster problem [56].

The research method was the interview, the investigation techniques were the in-depth interview and observation. The used procedure was the semi-structured interview, respectively the analysis of the data from secondary sources. The interview guide was used as an investigative tool. By the observation method, the research units that formed the sampling base were identified.

The sampling base consisted of 383 agritourism guesthouses and 236 classic and traditional restaurants in areas with ecological potential in Brașov County as well as 345 guides with a certificate in mountain tourism, ecotourism and natural habitat selected from the official lists published on the website of National Tourism Authority, within the Ministry of Economy, Energy and Business Environment [57]. The researchers opted for the quota method in the sampling process, as it has several advantages in the qualitative method [58]. Regarding the sample, a concept developed in the literature was adopted, according to which, at a certain level of experience, an approximation of the size and an evaluation can be made during the research, without it being possible to determine the sample size through a formula [59]. The sample included 33 subjects chosen by the research team, based on an analysis of their characteristics and compatibility with the general purpose and the objectives of the research. After randomly establishing the environmentally friendly tourism service providers (five agritourism guesthouses, three restaurants, and five guides) that would be part of the sample, the “snowball” method was used to complete the sample with other categories of participants. The representatives of the tourism companies were asked to recommend some suppliers of ecological products (primary producers of ecological goods), as well as tourists with ecological orientation. In this way, the sample was structured in three categories of interviewed people (P–primary producers, B–services providers from “business category”, and T-tourists) from Brașov and the surrounding rural areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample structure in qualitative research.

A rural configuration deals with the semi-coherent set of rules that orient and coordinate the activities of the rural stakeholders. On the one hand, stakeholders enact, instantiate, and draw upon rules in concrete actions in local practices; on the other hand, rules configure stakeholders [60].

In the case of rural tourism, producers and services providers are part of this rural configuration designed to satisfy tourists needs. Most producers and services providers are small or medium-sized businesses (mostly small farms or family businesses) [61]. These stakeholders are usually people who love farming and who have a strong desire to continue with it, to renew it, to make it match new societal demands and be viable for the next generation [62].

Tourists are becoming stakeholders involved in the creation of tourism products [63]. Whilst “experiential” has become a buzz word in tourism marketing, tourism professionals are stressing the need to meet tourists’ expectations with a provision that is based on a total and sincere commitment that goes beyond the classic boundaries of business and pleasure [64]. Rural tourism is not an exception. That is why one of the most important stakeholders in rural tourism are tourists.

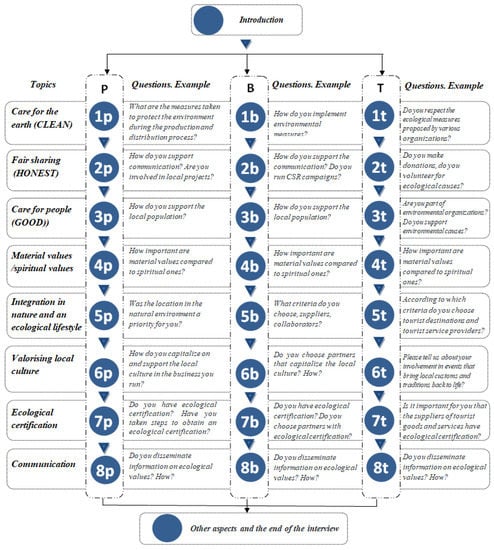

An interview guide was developed, taking into consideration the main aspects that are defining the two phenomena and their impact in rural tourism in the considered area–care for the earth, fair sharing, care for people, the balance between material and spiritual values, integration in nature and ecological lifestyle, the value of local culture, ecological certification, and communication. To let the interviewed people express themselves in a free manner, the researchers established, also, a section where the participants were permitted to identify and explain other elements that they consider important in their opinion (see Figure 1—The interview guide flowchart).

Figure 1.

The interview guide flowchart.

The interview guide was designed using the stair-climbing technique [65], the questions being asked in a logical sequence that exhausts all the aspects closely related to the investigated subject. The interviews were conducted at the participating locations. The duration of the interviews ranged from 50 to 60 min. The interviews began with an introductory discussion in which the aspects of confidentiality were presented, the way the interviews were recorded, from each participant the informed consent was obtained verbally, and the purpose of the research was stated. During the interviews, the research participants were urged to provide detailed information on all the discussed topics [66] until the researchers considered that a thorough understanding of the topic had been reached.

For data analysis and interpretation, we used content analysis, summarizing the answers through keywords. The analysis of the vertical content helped to determine the way in which each participant approaches the aspects related to ecology, offering a clear image of each entity. The horizontal analysis offered the possibility to analyze the answers on each topic and to draw important conclusions regarding the design of profiles within which the “stakeholders” involved in the eco-value chain in the tourism field can be included.

As Figure 1 shows, the qualitative research focused on the aspects that give the essence of the two concepts considered as important sources of the development of rural tourism in Brașov County: permaculture and downshifting. From the interview guide flowchart, the common elements and the interaction between permaculture and downshifting also emerge. Therefore, these elements confirm the validity of the concept of permaculture downshifters [28]. The interview participants were not explicitly introduced to the concepts of permaculture and downshifting, these concepts resulting from the authors’ analysis of the content of the interviews. By processing the answers to the questions asked, the Results section will highlight the key issues related to permaculture and those related to downshifting.

4. Results

Through the qualitative research carried out, the researchers found important information regarding the importance of permaculture and downshifting in Brașov County. The three parts involved in rural tourism through permaculture and downshifting (P–Local producers and service providers; B—Intermediaries: travel agents, independent tour guides, accommodation units and food services providers; T–Tourists) highlighted several common and specific aspects about these two phenomena and they expressed their opinion on the use of permaculture and downshifting for developing the rural communities with touristic potential.

4.1. General Results

Permaculture and downshifting create special interconnections which determine specificity to the distribution networks. As it results from the respondent’s opinion, distribution networks are naturally formed, over time, “as a root that grows and spreads freely in a natural area enjoying the effects of symbiosis” [#B4] between locals (P)-tourism service providers (B)-tourists (T) under the influence of nature, culture, and spiritual values. The research participants are aware that the total value of tourism services provided because of permaculture and downshifting, based on the efforts of all the members of the distribution network (organizations, tourism companies but also local individuals). For the interviewed persons, each link within the distribution network has an essential contribution on creating ecological tourism product and they must take into considerations the permaculture and downshifting characteristics in each distribution link.

The shape of the networks is constantly changing. These may increase or, on the contrary, may be restricted depending on external environmental factors (legislative, technological, cultural, etc.). At the same time, the “mature”-”immersed” networks were identified in the ecological values as well as the “young” networks in a formation that share the ecological values and aspirations, but which they implement only to a small extent.

4.2. Issues Related to Permaculture

The three essential elements specific to permaculture–care for the earth, fair sharing, and care for people—were found among the basic values of the respondents and their entire behavior is influenced by these principles.

Related to the first characteristic of permaculture–care for earth–, 9 (nine) respondents, who built or rehabilitated buildings for their tourism use, stated that the use of environmentally friendly construction and planning materials was a priority for them, and they endeavored to use as many organic or natural products as possible. “I used wood and river stone where possible” [#B3,4]. Additionally, as a matter of caring for the earth, the research participants considered themselves responsible for implementing ecological measures such as the proper behavior in nature, both in protected natural areas and during some touristic tours with the purpose of seeing wild animals in their natural habitat; reducing the number of tour participants in an attempt to disturb as little as possible the natural environment and to offer “an authentic and personal experience, not a mass one, as in the case of large groups brought by some travel agencies” [#B11]; “I prefer the activities in which I can observe animals in their natural habitat, even if it means effort and waiting hours” [#T4].; revealed one of the interviewed tourists while showing us the footage made during the trips from which he had just returned; collecting waste from the paths during the tours and through the responsible use of natural resources. The accommodation services providers try to facilitate the selective collection of waste “Our tourists are taught to selectively collect at home and want to do the same on vacation” [#B9]. Other environmental protection measures mentioned by the respondents is the “collection of waste oil, use of al component parts of the raw material”. [#B13]. Moreover, they are aware of their activity impact on the environment and they take actions to minimize it: “I only go on marked paths with tourists, do not use shortcuts through the forest because any additional paths unnecessarily erode the soil” [#B8]. So, characteristics of permaculture, are appreciated not only as sources of the welfare for tourists but, also, as sources for rural community welfare.

Fair sharing is reflected by the involvement in local projects and payment of tax liabilities, as well as involvement in CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) campaigns. Even though a small number of research participants have said they are making donations, most of them are organizations seeking sponsorship, fair pricing, tailored to the purchasing possibilities of the tourists requesting them services can be considered as ethical actions. The revenues that the locals can obtain from the sale of surplus production are not affected by the commercial addition that an intermediary could claim because they are supported to sell directly to tourists. Tourists are also guided to purchase products and services directly from local producers at fair prices. “If a tourist wants to purchase local products, cheese, fruit, jam, etc., we indicate him the addresses of the locals that we know will have their own surplus production, or, if the tourist does not want to move, we call the locals to us” [#B1]. One of the respondents–who represented the organization Țara Bârsei, founded to save the gastronomic heritage and to promote food and local products, presented a way that this organization used to participate in conducting social responsibility campaigns through encouraging local initiatives by promoting them on the Facebook page, providing food to charitable events, participation in different sport competitions conducted to support social causes.

Caring for people is revealed by supporting other community members and by using the local workforce. All respondents in the intermediate category (B) said they use local suppliers of tourist products and services, which, in turn, offer environmentally friendly products. “As much as possible I try to choose suppliers using local, environmentally friendly products, I consider it to be one of the essential things to reach a kind of sustainable tourism.” [#B11], “I try to use only local suppliers of tourist products from rentals to local guides services where needed, some meals we serve to local producers–sheepfolds or the houses of people in the villages where we go.” [#B12], said two of the research participants, who are conducting ecological tours in natural areas. Tourists participating in the research, unanimously, said they prefer to buy local products “I do not bring supplies and do not buy from stores. I only buy products from the locals” [#T7] revealed an interviewed tourist.

Another research participant said that in addition to the food produced from their own household “acquires and capitalizes surplus production in the village gardens” [#B13]. Also, with the support of locals, this organization offers guided tours in nature, walking or cart ride and camping, cycling tours, family activities and botanical tours.

Representing the community within the tourist village, brought back to life following an international media campaign—Viscri, one of the research participants presented how restaurant owners support locals by acquiring preferentially local products. He also argues that the actions of the authorities involved in tourism development have led to social benefits. During the last years, the number of socially assisted families has decreased significantly (from 47 families to just 2), by engaging tourism-related activities.

4.3. Issues Related to Downshifting

One of the research participants, the representative of Foundation Conservation “Carpathia”, proposed creating a new wildlife reservation in the Southern part of the Romanian Carpathian Mountains, without bringing any environmental damage, bringing benefits both to him and to the local community. He presented how they provide organic or natural products: “A tomato picked from the garden will always taste different from the products in a supermarket”. According to him, it is the duty of every participant in ecological tourism to remind tourists “how wonderful and how important food is especially in these modern times, where almost all food can be found at any time, in any supermarket” [#B9]. To preserve the authenticity of the area, one of the respondents has rearranged several old houses, abandoned in the village, transforming them into comfortable and modern guest houses. The representative of this organization believes that “every old piece of wood or stone reused carries an old story, which comes to life with the traditional restoration of the house” [#B9].

Another research participant, representing one of the most appreciated tourist villages in Transylvania, Viscri, argues that, even though tourism is one of the main sources of income of the inhabitants, there is a unanimous concern to preserve the country’s lifestyle— “We do not want to transform the locality into an area of commercial tourism” [#P8]. He gave the example of an unwritten rule, unanimously accepted by the locals, to expose and sell the products crafted in their own backyard “in order not to load the village’s streets with merchandise” [#P8]. At the same time, the locals opted for an integration of the lifestyle that maintains the authenticity of the place and the relationship with nature: the streets were cobbled (even if they could have been paved), the houses are plastered with faded lime (local product), water is provided through a system of lakes whose construction is based on principles of permaculture. Residents are willing to contribute to the preservation of balance through personal efforts and concessions: some of them have waived the ownership of their land to create an outside parking garage, which is intended for buses, which does not overcrowd the village streets and doesn’t pollute the village air. Moreover, on a voluntary basis, the locals participate in directing the village’s movement. Tourists appreciate the effort made by the locals and respect the unwritten rules “I don’t even conceive the idea of parking the car inside the village. It would be like a sacrilege” [#T5].

4.4. Related Issues Resulting from the Research–the Ecological Perspective

The research did not reveal only opinions about permaculture and downshifting, as the subjects are related to other aspects connected to the two phenomena, such as the ecological certification, the specific communication, and some ways in which they can contribute to the local development.

Most of the intermediary respondents have a personal ecological orientation perspective, they have been, or they still are active members of some nongovernmental organizations with environmental protection concerns. For example, all five ecotourism (ecological) services providers have stated that they organize tours in natural areas, which they present to tourists from “an ecological perspective” [#B6], most often with self-declared environmentalist tourists, who are responsible towards the visited nature and local communities and choose “experiences different from mass tourism” [#B7]. Some tourists are even specialists in forestry, biology, ornithology and require specialized information about the visited ecosystems. They appreciate the fact that Romania “still has a fascinating ecological capital, which is no longer found in many countries of the world (bears, wolves, lynx, biodiversity, virgin forests)” [#B8]. They increased their interest in ecological certification, which could lead to a reduction in the risk perceived by both tourists (T) and other members of the network (P) and (B). Most of the respondents in the intermediate category (B) are familiar with ecological certification systems but do not consider them “mandatory in the ecological procurement process” [#B7]. The development and regaining of ecological certification systems in Romania is also suggested. “Ecological certification is a quality stamp, and it would be good to have a more developed system, a larger network of ECO certified services” [#B12]. Some of the respondents considered advisable a “local, authentic certification” [#B11], specifying each destination, whereby tourists and tourism companies have the right to purchase locally produced products, with local products, suggesting the concept of “trace back to the grass thread” (e.g., buying dairy products made from cow’s milk that graze in the visited Montana area, where the flora is specific and has different properties of flora in the field areas). Referring to the ecological certification, the member of Slow Food Țara Bârsei, a research participant said “we choose more local suppliers who have ecological concerns even if they do not have proof in this regard. We are interested in the quality of products and the supply flow. To be a long-term partnership” [#B13]. Also, most of the tourists participating in the research stated that they do not expect locals to obtain certifications, but they feel confident if an economic entity has such a certification. “I don’t think it would be very difficult for local independent producers to obtain an ecological certification. I confidently consume local products even if they are not certified” [#T1], “I feel good to see that a restaurant I go to has an ecological certification” [#T3].

The respondents highlighted their attempts to communicating/sharing their specific experiences and their orientation in providing sustainable touristic products through capitalizing on ecological production in the virtual environment, playing the role of influencer or vlogger, making themed posts in the virtual environment.

5. Discussion

The main responses revealed that in the case of locals (local producers and service providers) as bidders, the care for the earth is highlighted in particular by giving up fertilizers and chemicals, integrating production in nature, minimizing the amount of non-degradable waste, ensuring crop complementarities, minimizing the consumption of water and energy, the use of ecological materials of construction and arrangement, the use of renewable energy (through traditional methods), capitalizing on the local production.

Looking at intermediaries (travel agents, independent tour guides, accommodation units and food services providers), the care for the earth is expressed through the way of choosing the ecological suppliers, the interest for the ecological certification, the implementation of ecological measures and offering organic products. Fair sharing is mirrored by the way tourism services providers carry out their CSR campaigns and whether they pay their tax liabilities. Caring for people is quantified by the degree to which they provide support to other community members and employ a local workforce.

Tourists expressed their care for the earth through the way they respect the ecological values, the way they make ecological purchases, the way that they selectively collect the waste, the way that they show availability to pay extra for ecological products/services/ecological packaging, by supporting ecological causes and the fact that they report to authorities’ different ecologic problems they observe. Participation in fair sharing is provided by the extent to which tourism service providers donate funds for ecological causes or participate in volunteering actions. Caring for people is manifested when they declare their membership in ecological associations/organizations or become opinion polls on ecological issues.

The research revealed certain preoccupations regarding some aspects specific to downshifting: minimizing the importance of material values and orientation towards spiritual values expressed by a minimalist design approach; re-use of objects; donations; practicing fair prices; supporting CSR campaigns; concern for spiritual life; integration in nature and an ecological lifestyle expressed by: localization in rural areas or near natural areas, use of natural materials, selective waste collection, choice of integrated suppliers in nature, purchase of natural materials products, purchase of products and services provided by bidders integrated in nature; capitalizing on the local culture expressed through: preserving local customs and traditions, preserving the traditional lifestyle, using and promoting traditional/local methods of production (gastronomic recipes, crafts, craft themes, etc.), choosing and promoting suppliers that preserve local customs, traditions and the traditional lifestyle, the use of traditional production methods, the expression of interest in local customs, traditions and the traditional lifestyle. These characteristics are present at each link of the distribution network (P, B, T).

According to the results obtained from the research, there is a significant difference between how caring for the earth and caring for people are addressed by locals (P) compared to intermediaries (B); the intermediaries, by their exposures, proved that they are more interested in these subjects than the locals. “We organize waste-gathering campaigns often with local school students, to gather what their parents and grandparents simply throw in nature.” [#B1]. In this way, they act in several directions, such as a clean environment, a young, educated generation, a local community capable of understanding the needs of sustainable development.

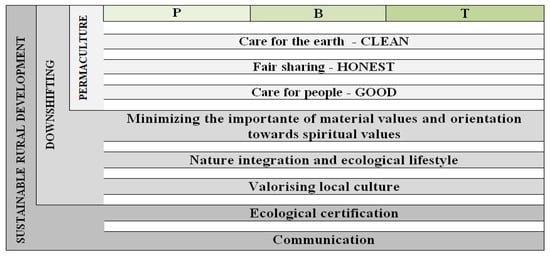

In addition to permaculture values, downshifting is distinguished by minimizing the importance of material values and orientation towards spiritual values, integration in nature and an ecological lifestyle as well as capitalizing on local culture. From this perspective, Figure 2 shows a synthesis of the elements that give content to the concepts of permaculture and downshifting, as sources of tourism development in rural areas of Brașov County.

Figure 2.

Elements that define permaculture and downshifting as sources of tourism development in rural areas of Brasov County. Source: Matrix developed by the authors. Notes: P–Local producers and service providers; B—Intermediaries: travel agents, independent tour guides, accommodation units and food services providers; T–Tourists.

To highlight the basic reasons and motivations that lead the interviewed subjects to share and respect permaculture and downshifting—described above—, a synthesis of the answers was performed. The research conclusions lead to the idea that, in the studied rural idea, the participants in the tourism activities respect and integrate the principles of permaculture (care for the earth, fair sharing, and care for people) and characteristics of downshifting (minimizing the importance of material values and orientation towards spiritual values, nature integration and an ecological lifestyle and valorizing local culture). In addition, applying ecological certification and communication, they may contribute to the wellbeing and development of the rural community. The summary results of this analysis are synthesized in a matrix that highlights all the discussed issues (Figure 2).

As the matrix reveals, the motivations of the interviewees are based on two categories of elements that are sources of sustainability in rural development through tourism: the ethics and the principles of permaculture and the orientation towards downshifting and spiritual values. To contribute to the sustainable development of rural areas, all these specific principles and values must be completed by other supplementary elements (such as communication and ecological certification).

6. Conclusions

The decisive force for rural transformation is the transition to a post-productive society, which in rural areas, is characterized, among other things, by the reorientation of the economics from agriculture to tourism. The rural landscape is becoming an agricultural production area into a consumption area for tourism and housing. The concepts of permaculture and downshifting have emerged-as detailed in the article-based on the refusal of people to consider material values as defining elements of their existence, instead preferring the idea of the quality of life and protection of nature. People attached to these values express themselves both through the behavior in the production of goods and services in general and, also, in the sphere of consumption of environmentally friendly tourist goods and services. Their lifestyle, shown in the professional and personal sphere, has contributed, over time, to changes in tourist demand. More and more, people are taking time to visit rural areas, to understand local people and the local traditions, to consume organic products produced in the community, to integrate with nature and to build an ecological lifestyle. These activities are facilitated by rural tourism, which becomes a certain solution for the local development of some tourism areas. The article has highlighted some ways that permaculture and downshifting—as possible sources to develop rural tourism—can contribute to rural development.

The research brings the first element of novelty, by highlighting the specific involvement of each link between the components of the networks of the supply chain in this case: primary producers of organic goods, ecological tourist service providers, and tourists, as carriers of demand for tangible products and ecological services. Several elements specific to distribution in rural tourism have been identified, leading to the shaping of environmentally sound networks, based on specific concepts, such as good, clean, ethical, nature integration, local culture, and communication.

Permaculture and downshifting are defined not only by the theoretical elements highlighted in the literature but, also, by specific issues revealed in the research that subscribe in a clear manner these networks in a “green framework”—orientation to spiritual values, nature integration, ecological lifestyle, valorizing local culture. Permaculture and downshifting mean not only planned exploitation of the rural resources but, also, the valorization of natural and cultural heritage, as other studies revealed [67].

Another element of novelty brought by the research is represented by the creation of a possible system of measurement/appreciation of the characteristics that network stakeholders possess. The results were gathered in a matrix that integrates the theoretical characteristics (coming from the literature) and the specific characteristics (found from the involved stakeholders), with the possibility to assign levels of evaluation to appreciate the degree to which the elements within it are held. Such a tool may be used by all the involved stakeholders-primary producers of organic goods, ecological tourist service providers, tourists, and local authorities–to create tourist products in accordance with the requirements of consumers in rural tourism and to contribute to rural development.

The research results revealed some aspects that could guide us to the following conclusions:

- The main implications of the research consist of finding the elements of rural development in County through practices of downshifting and permaculture. As it results from the research, they might be appreciated as “good practices” in the implementation of sustainable rural tourism, because they create tourism products in balance with nature, with care for people, with the ecological lifestyle. They contribute to the conservation of the environment and the agricultural system in which they take place, and these ideas are in concordance with the results of other studies [65].

- Some specific aspects of downshifting were highlighted by all the categories of the stakeholders.

- Regarding permaculture, stakeholders are preoccupied to respect its principles, but there are different perspectives regarding these principles among respondents.

These conclusions are in concordance with previous studies [29,30,32,33] but the research brought into attention a more detailed perspective, since it pointed out these aspects on different categories of stakeholders involved in rural tourism (local producers and service providers; intermediaries and tourists). This might be considered not only a novelty element but also an element of added value.

The results of the present study provide a series of practical implications for different categories of stakeholders from rural destinations. Public authorities from local, regional (county), and national levels, in cooperation with representatives from non-governmental organizations, may consider promoting downshifting and permaculture as good practices in the implementation of sustainable rural tourism. Several campaigns (online and offline) may be organized to raise the awareness of different categories of rural tourism stakeholders regarding the perspectives of approaching these good practices in their rural tourism activities. Connecting different categories of rural tourism stakeholders interested in downshifting and permaculture in online communities and groups may also support the implementation of these concepts in rural destinations.

Despite its contribution to the academic studies on rural tourism, the present study has some limitations, which open the path for future studies which may address these issues. The main limitation is related to the fact that it is focused on a single region (Brașov County) and country (Romania). Future research may be based on international studies, including comparisons between different regions/countries. Such an approach may provide supplementary information on the perspectives of sustainable tourism development in rural areas. Another limitation is given by the qualitative research method. Other researchers may consider conducting surveys, to be able to generalize the results. Furthermore, the interviewed rural stakeholders are representatives of the private sector or consumers. Governmental authorities were not included in the qualitative research. Therefore, future studies may consider analysing the perspectives of both private and public representatives regarding the implementation of sustainable rural tourism, through permaculture and downshifting.

Author Contributions

All the authors equally contributed to this work, to the research design and analysis. Conceptualization, G.E., B.T. and I.-S.I.; methodology, G.E. and A.-S.T.; writing, review and editing, G.E., B.T., A.-S.T., I.-S.I. and A.-N.C.; interviews, A.-S.T. and A.-N.C.; supervision, G.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was financed by the Transylvania University of Brașov.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions eg privacy or ethical. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Avramescu, T.C.; Popescu, R.F. Tourism-Part of Sustainable Local Development; Institutul National de Cercetări Economice: Chișinău, Moldova, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- OEC. OECD Tourism Trends and Policies. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/tourism/2018-Tourism-Trends-Policies-Highlights-ENG.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Coroș, M.M. Rural tourism, and its dimension: A case of Transylvania, Romania. In New Trends and Opportunities for Central and Eastern European Tourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 246–272. [Google Scholar]

- Howe, M. What Is Good Lifestyle for Families Downshifting to Sustainable Living and… Will That Property Deliver? 2017. Available online: https://small-farm-permaculture-and-sustainable-living.com/what_is_good_life_style/ (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Nelson, M.R.; Rademacher, M.A.; Paek, H.-J. Downshifting consumer= upshifting citizen? An examination of a local freecycle community. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 2007, 611, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, D. RetroSuburbia: The Downshifter’s Guide to a Resilient Future; Melliodora Publishing: Seymour, IN, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; Renting, H.; Brunori, G.; Knickel, K.; Mannion, J.; Marsden, T.K.; de Roest, K.; Sevilla-Guzman, E.; Ventura, F. Rural development: From practices and policies towards theory. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, G. Valuing the Future: Economic Theory and Sustainability; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman, M. Income, Capital, and the Maximum Principle; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, N.; Lowe, P. Europeanizing rural development? Implementing the CAP’s second pillar in England. Int. Plann. Stud. 2004, 9, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, J.; Cox, D.; McInroy, N.; Southworth, D. An International Perspective of Local Government as Stewards of Local Economic Resilience; Norfolk Charitable Trust: Manchester, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, H. Resilient Local Economies: Preparing for the Recovery; Experian Insight Report; (Quarter 4); Experian: Nottingham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, E.; Cole, I. Resilience, and the Recession in Six Deprived Communities: Preparing for Worse to Come? Joseph Rowntree Foundation: York, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lenao, M.; Saarinen, J. Integrated rural tourism as a tool for community tourism development: Exploring culture and heritage projects in the North East District of Botswana. S. Afr. Geogr. J. 2015, 97, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Citro, E.; Salvia, R. Economic and social sustainable synergies to promote innovations in rural tourism and local development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Chen, L.-H.; Su, P.; Morrison, A.M. The right brew? An analysis of the tourism experiences in rural Taiwan’s coffee estates. Tour. Manag. Perspec. 2019, 30, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.M.; Wall, G.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Livelihood sustainability in a rural tourism destination-Hetu Town, Anhui Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bran, F.; Marin, D.; Șimon, T. Turismul Rural—Modelul European; EdituraEconomică: Bucharest, Romania, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beeton, S. Community Development through Tourism; Landlinks Press: Collingwood, VIC, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dolezal, C.; Burns, P.M. ABCD to CBT: Asset-based community development’s potential for community-based tourism. Dev. Prac. 2015, 25, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Borges, O.; Cerezo, J.M. Community-based tourism, and local socio-economic development: A case study in Cape Verde. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 1608–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitefield, S. The New Institutional Architecture of Eastern Europe; Springer: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, L.; Schneider, P. A facilitator’s Handbook for Permaculture. Solutions for Sustainable Lifestyles. Produced with Support from Developed by IDEP Foundation with PERMATIL and GreenHand. 2011. Available online: www.idepfoundation.org (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Daly, H. Toward some operational principles of sustainable development. Ecol. Econ. 1990, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prell, C.; Hubacek, K.; Reed, M. Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis in natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.S.; Lodhi, S.A.; Akhtar, F.; Khokar, I. Chalenges of waste of electric and electronic equipment (WEEE): Toward a better management in a global scenario. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2014, 25, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, F.; Lodhi, S.A.; Khan, S.S.; Sarwar, F. Incorporating permaculture and strategic management for sustainable ecological resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 179, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgren, D. Permaculture: Principles and Pathways beyond Sustainability; Holmgren Design Services: Hepburn Springs, NW, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, G. Permaculture. A Beginners’ Guide; Spiralseed: Westcliff on Sea, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bellacasa, M.P. Ethical doings in nature cultures. Ethics Place Environ. 2010, 13, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollison, B.; Slay, M.R. Introduction to Permaculture; Tagari Publishers: Tyalgum, NSW, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dabija, D.C.; Băbuţ, R. An approach to sustainable development from tourists’ perspective. Empirical evidence in Romania. Amfiteatru Econ. 2013, 7, 617–633. [Google Scholar]

- Liiceanu, A. Fenomenul Downshifting. 2012. Available online: http://frumoasaverde.blogspot.com/2012/06/fenomenul-downshifting-aurora-liiceanu.html?fbclid=IwAR2JdTLlf5Lx1VU3satyenmI0JXaR4NlLu-PpuK845Oh_howVCNNIuFdrEc (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Thoreau, H.D. Walden or Life in the Woods; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schreurs, J. Living with Less: Prospects for Sustainability; International Centre for Integrated Assessment and Sustainable development (ICIS), Maastricht University: Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- SlowMovement. Downshifting as a Way of Life. 2020. Available online: https://www.slowmovement.com/downshifting.php (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Revista Cariere. Downshifting-ul sau Dragostea de Viata. 2007. Available online: https://revistacariere.ro/inovatie/trend/downshifting-ul-sau-dragostea-de-viata (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Downshifting Week. Downshifting Perceptions: Leaving Well-Paid Jobs for Personal Fulfilment. 2019. Available online: http://www.downshiftingweek.com (accessed on 20 September 2019).

- Holgren. About Permaculture. 2020. Available online: https://holmgren.com.au/about-permaculture/ (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Hoang, T. Permaculture: Real Food, Real Farming, and Real Life. 2020. Available online: http://contemporaryfoodlab.com/hungry-people/2015/03/permakultur-echtes-essen-echte-landwirtschaft-und-echtes-leben/ (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Veteto, J.R.; Lockyer, J. Environmental anthropology engaging permaculture: Moving theory and practice toward sustainability. Cult. Agric. 2008, 30, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, D. Permaculture, and the third wave of environmental solutions. In Collected Writings and Presentations; Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, VT, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gavrilă-Paven, I. Tourism opportunities for valorising the authentic traditional rural space-study case: Ampoi and Mures Valleys microregion, Alba County, Romania. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nistoreanu, P.; Țigu, G.; Popescu, D.; Pădurean, M.; Talpeș, A.; Țală, A.; Condulescu, C. Turismul rural românesc, Ecoturism si turism rural. ASE. 2006. Available online: http://www.biblioteca-digitala.ase.ro/biblioteca/pagina2.asp?id=cap11 (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Bogan, E. Rural tourism as a strategic option for social and economic development in the rural area in Romania. Forum Geograf. 2012, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiṭea, L.F. Rural household typology according to the socio-economic development perspectives. In Agrarian Economy and Rural Development—Realities and Perspectives for Romania, International Symposium, 10th ed.; The Research Institute for Agricultural Economy and Rural Development (ICEADR): Bucharest, Romania, 2019; pp. 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Family Farming Knowledge Platform—Romania. Available online: http://www.fao.org/family-farming/countries/rou/en/ (accessed on 21 December 2020).

- Institutul Național al Patrimoniului. 2019. Available online: https://patrimoniu.ro/monumente-istorice/lista-patrimoniului-mondial-unesco (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Agency for Sustainable Development in Braşov County. Development Strategy for Braşov County, 2013–2020–2030 Horizons. 2010. Available online: https://addjb.ro/uploads/proiecte/SDJBV/Documente/ADDJB_Strategia.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Stastná, M.; Vaishar, A.; Pákozdiová, M. Role of tourism in the development of peripheral countryside. Case studies of Eastern Moravia and Romanian Banat/Rolul turismului în dezvoltarea spatiului rural periferic. Studiu de caz: Estul Moraviei si Banatul Românesc. In Forum Geografic; University of Craiova, Department of Geography: Craiova, Romania, 2015; p. 83. [Google Scholar]

- Brasov Tourism, Strategia de dezvoltare a judetului Brasov. 2013. Available online: http://www.brasovtourism.eu/upload/files/strategia_de_dezvoltare_a_judetului_brasov-turism-2013-2020-2030.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Mihai Eminescu Trust. Turism Cultural. 2020. Available online: https://www.mihaieminescutrust.ro/turism-cultural/ (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Nazli, M. Does sustainability matter? A qualitative study in tourism industry. J. Yasar Univ. 2016, 11, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tellis, W.M. Introduction to case study. Qual. Rep. 1997, 3, 1–14. Available online: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol3/iss2/4 (accessed on 13 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Fiorello, A.; Bo, D. Community-based ecotourism to meet the new tourist’s expectations: An exploratory study. J. Hosp. Market. Manag. 2012, 21, 758–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, clusters, and innovation in tourism: A UK experience. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Tourism Authority. Available online: http://turism.gov.ro/web/autorizare-turism/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Golafshani, N. Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 597–606. Available online: http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol8/iss4/6 (accessed on 13 December 2020).

- Cho, J.; Trent, A. Validity in qualitative research revisited. Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Šimková, E.; Holzner, J. Motivation of tourism participants. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 660–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F.; Romei, P.; Tortora, M. An evolutionary approach to the study of rural tourism: The case of Tuscany. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condevaux, A.; Djament-Tran, G.; Gravari-Barbas, M. Before and after tourism (s). The trajectories of tourist destinations and the role of actors involved in “off-the-beaten-track” tourism: A literature review. Tour. Rev. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondeau, K. Quelle place pour l’hôtellerie indépendante face à la pression des agences de voyage en ligne (OTA) et à l’émergence de l’économie collaborative ? Annales des mines, Réalités Industrielles 2015, 3, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research. An Applied Orientation; Pearson Education International: Cranbury, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, C.; Neale, P. Conducting in-Depth Interviews: A Guide for Designing and Conducting In-Depth Interviews for Evaluation Input; Pathfinder International Tool Series: Watertown, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ivona, A.; López, L. Rural development in the region of Apulia (Italy) initiatives and practices: Between past and future. In Proceedings of the X CITURDES: Congreso Internacional de Turismo Rural y Desarrollo Sostenible, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 19–21 October 2016; pp. 539–554. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).