Abstract

The idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR) has attracted the interests of both practitioners and scientists, particularly since 1953, when H. R. Bowen published The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman. Over the years, the CSR concept evolved and became a managerial phenomenon; it was applied to different sectors with supposedly excellent effects. Unfortunately, there was discourse around the meaning of CSR. In the world of science, there is no agreement as to the semantic area of CSR. Academics face absolute, undisturbed freedom in the formulation of its elements and definitions. That abovementioned ambiguity determined the situation the recent CSR literature is vague and biased, and an extensive analysis of the latest contributions are lacking. To address this gap, there has been proposed a systematic literature review and bibliometrics of 119 articles published in 45 peer-reviewed, high-quality academic journals and 19 books, from January 1950 to July 2020. There are three objectives of this paper: to analyze the recent CSR definitions in the context of Carnegie’s principles, to identify trends in that field and evaluate the utility of the scientific efforts in the abovementioned context, and to indicate the future research paths in the context of corporate social responsibility.

1. Introduction

Andrew Carnegie was a steel magnate, born in Scotland. In 1848, he moved to America in search of better economic opportunities. In the early 1870s, Carnegie co-founded his first steel company, near Pittsburgh. Over the next few decades, he created a steel empire, maximizing profits and minimizing inefficiencies through ownership of factories, raw materials, and the transportation infrastructure involved in steel making. In 1892, his primary holdings were consolidated to form Carnegie Steel Company, which was sold to J. P. Morgan in 1901. After Carnegie sold his steel company, he retired from business and devoted himself full-time to philanthropy. Carnegie gave away the equivalent of billions of U.S. dollars in today’s currency, which represented the bulk of his wealth. Among his philanthropic activities, he funded the establishment of more than 2500 public libraries, donated over 7600 organs to churches and endowed organizations (many of which exist today), and dedicated funds to research in science, education, world peace, and other causes. Among his gifts was the $1.1 million U.S. dollars required for the land and construction costs of Carnegie Hall. The Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie Mellon University, and the Carnegie Foundation were all founded as a consequence of his financial gifts. He was the largest individual investor in public libraries in American history [1]. In 1889, he issued the essay “The Gospel of Wealth” which, according to the research conducted in this paper, was the “milestone” of contemporary corporate social responsibility (CSR).

In the scientific field, this concept has been a subject of interest to researchers for over a century now, both in academics and in economic reality. As a consequence, a multiplication of approaches to CSR has occurred [2,3,4,5,6], and the world of science experiences both a strong support for the paradigm introduced by Carnegie and its primal contribution to corporate social responsibility [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], as well as critical opinions of it [16,17]. In 1889, Carnegie proposed philanthropy principles [18], the backbone of which were charity and trust (in last decade of the nineteenth century, human relations management problems and environmental protections issues were not the subject of organizational consideration). The first of them was the same as the biblical principle of mercy [19] and, therefore, in the absence of any formalized social welfare system, it was tantamount to entrepreneurs taking over part of the responsibility for improving the living conditions of society. The principle of trust alluded to the biblical doctrine of wealthy individuals who were expected to manage their wealth on behalf of other people and therefore to dispose of their assets in a socially acceptable manner. If the entrepreneur did not perform these duties in person, this was to be done by talented people; nevertheless, the author did not formulate any criteria of talent [18,20] (p. 3). Carnegie was also a strong opponent of traditional “blind” charity, which he considered one of the most serious obstacles to human development [18] (p. 13). He argued that help was to be offered to others only by facilitating access to information and to the acquisition of knowledge [18] (p. 24) and by strengthening peace and human bonds [18] (p. 11). People deserving help—with few exceptions—very rarely need help. Really worthy people never need any support [18] (p. 13). A true reformer, then, is one who is careful not to support those who do not deserve it, while at the same time trying to ensure that those that do deserve it receive appropriate help [18] (p. 14). According to Carnegie, in order to be effective in helping through philanthropy, it is necessary to follow the rules (Table 1).

Table 1.

Principles of effective philanthropy.

Consequently, the aforementioned doctrine constitutes a combination of ethics and economics, which to this day determines many problems related both to interpretation and definition. To date, no unambiguous definition of corporate social responsibility has been worked out, neither on theoretical grounds nor in practical activities. Although there were, on the grounds of law, successful attempts to clear the concept in the context of possible regulation [21,22,23,24,25], in the world of management science these valuable efforts could not be perceived as effective [26,27]. The reasons of this inefficiency can be found in the relatively long history of social responsibility and high level of both scientific and organizational interests of this concept, when various justifications and interpretations were referred to.

According to the abovementioned complex conditions, I have put the impact on a high number of CSR-related papers, published over a long period of time—from January 1950 to July 2020—to indicate the maximum possible structure of the creation and development of CSR. Moreover, I implement a structured and systematic approach, according to the procedures proposed by Tranfield et al. [28] for a systematic literature review, ones which allow one, through a meticulous process, to indicate high-quality journals recognized as relevant by the CSR community.

Additionally, in the study I relate searching for the common elements of corporate social responsibility definitions established in high-quality journals. These features allow this study to offer a significant contribution in the CSR field. This study provides a comprehensive picture of the latest trends in CSR literature through the comparison and classification of CSR papers related to important features such as: journals where CSR papers are published, the authors of the papers, the year of publication, and the corporate social responsibility definitions implemented. On these grounds, this review not only offers a detailed analysis of the significant number of CSR articles in the period of research covered, those journals that dedicated a great number of papers to CSR, and the authors’ contribution to theoretical and organization-based research, but the review also follows a more detailed organizational approach to voluntarism. It provides a new context for implementation and research issues, and their content evolution in the context of main scientific problems explored in recent years and the new ones addressed. This is the first review that takes into consideration the utility of CSR literature in relation to the following:

- Carnegie’s principles established for precise, unequivocal activity fulfilling the requirements of corporate social responsibility, and whether these are adopted in particular CSR studies.

- An attempt to research a general corporate social responsibility definition that could be widely accepted in academic literature. Using the existing theories to analyze/indicate CSR issues is extremely important, as they enable one to increase the level of the understanding of complex dynamics of this phenomenon. Taking into consideration this comprehensive evaluation of recent CSR literature, this review identifies gaps in knowledge in the context of theoretical perspective use, research principles, and content of CSR studies. The author claims, in opposition to papers presented previously arguing that there is a common belief that CSR is an inherent factor of an organizational competitive advantage, that CSR conception follows the trajectory to distraction from the very beginnings. Finally, the abovementioned gaps found as a result of an analysis of the recent CSR literature represent a foundation to provide and discuss important ideas for future research. As a result, three research questions (RQs) guided this review: (RQ1) Is there a common and widely accepted definition of CSR in the world of science? (RQ2) To what extent are the Carnegie’s CSR fundamentals implemented in the source literature? (RQ3) What are suggestions for future studies?

The article is structured as follows: the next section includes the methodological approach used for constructing the systematic literature review. After that, an analysis of the data collected is reported (to answer RQ1 and RQ2) and, further, the research gaps are indicated. Then a critical discourse is implemented in the context of results, providing suggestions for future research on CSR (RQ3). The last section covers conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

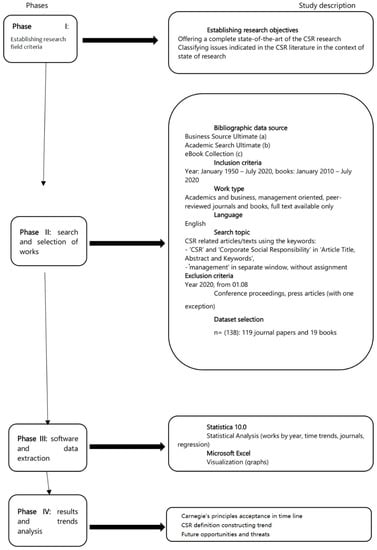

Systematic literature reviews as well as bibliometric analyses in the world of science are very relevant for the researcher delving into an intellectual field and developing research questions that provide an increase in the capacity for knowledge [29,30]. Systematic reviews include an explicit algorithm, which enables selection and evaluation of the literature throughout a transparent and reproducible procedure that allows exploration of an area of knowledge [28,31,32,33,34]. The bibliometric approach also implements a similar formal and rigorous procedure which guarantees the high level of good-quality information used [35,36,37]. These approaches include many advantages in relation to traditional unstructured reviews. Moreover, they establish the backgrounds to objectively identify, select, and evaluate articles and, consequently, produce a synthesis that depicts the depth of knowledge in the field as an outcome that minimizes bias errors, to improve the quality of the review process, to confirm their validity through replication of precise steps, and to synthetize the area-related literature. Finally, an SLR is perceived as a versatile approach, adopted in recent studies published in high-quality scientific journals, as claimed by Danese et al. [38]. Additionally, to meet the criteria of “fit for purpose” protocol [31] (p. 110), bibliometrics was also undertaken [29,35,39]. The process consisted of 4 phases described below and summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The developed method in this study. Source: Author’s own study basis on [29].

2.1. Phase I: Establishing the Research Field Criteria

The first step was to define the object and boundaries of the review in the context of the RQs [40]. This task was particularly difficult in the context of CSR defining because this field is wide and, over the years, more and more doubts have arisen regarding the clarity of this concept. As a consequence, a semantic confusion occurred, leading to heterogeneous terms and definitions. Therefore, a decision was made to take into consideration studies referring to management-based CSR definitions, including identification and implementation. The aim was to identify peer-reviewed journals and books with the highest scientific value and research interest in CSR. Although this point has narrowed the abovementioned criteria, it seems justifiable to claim that these works can be useful in providing a more complete picture of CSR from the academic perspective. Hence, my review consists of several types of works focused on CSR.

2.2. Phase II: Search and Selection of Works

The source or database identification must be of the highest quality and reliability for both SLR and bibliometrics analyses. Therefore, it was decided to conduct the study using Business Source Ultimate (a), Academic Search Ultimate (b), and eBook Collection (c) for their high-quality standards, broad coverage of required information, and adequacy.

The research information was collected from publications from January 1950 to July 2020, and books from January 2010 to July 2020. The initial numbers for descriptors “CSR” and “corporate social responsibility” were: (a) = 13,023, (b) = 5663, (c) = 167. Only works in English were considered, as this language is the most widely used in scientific publications [41]. The second step was to narrow down the papers to ones with “corporate social responsibility or csr” in the title (section TI: results 5048 (a) and 1259 (b), accordingly), 67 (c). Further, selection articles with ”corporate social responsibility or csr” in the abstract or keywords (sections AB and KW: 4623 (a) and 1080 (b)). The next stage was to recognize management-oriented papers only (window: “management”, without assignment: 2519 (a) and 381 (b), 31 (c)). The last part of selection was performed through carefully reading each of the works and excluding those related to the public sector and NPOs and (or) also based on the rule of ceteris paribus: the author’s intension was to avoid unilateral (strictly positive or negative), biased approaches to CSR [42,43]. One hundred nineteen journals and 19 books satisfied the criteria.

2.3. Phase III: Software and Data Extraction

The research data were verified and examined based on the content and contribution to the research aim. After the selection, the mentioned data were coded (in binary) and transferred to a format readable by Statistica 10.0. for the statistical analysis. The second step was to transfer the data to Excel for graphical presentation.

2.4. Phase IV: Results and Trends Analysis

Data analysis consisted, according to the RQs, of three dimensions: the first was focused on the identification of whether the world of science has established one common definition of corporate social responsibility, recognizing the trends in the field and evaluating the utility of scientific efforts in this context; the second included an analysis of Carnegie’s principles acceptance in the reviewed literature; the last one indicated future research directions in the context of CSR development.

The whole process was performed in order to ensure the highest level of accuracy and reliability, as claimed in [29,38,39].

3. Results and Analysis

This section addresses RQ1 and RQ2 and provides a theoretical framework which organizes the recent CSR research problems basis on the source literature. To reach this aim, as described in the Methodology Section, two issue sections were established. The first of them tested whether there was a consensus in the context of CSR definition and understanding in the world of science; the second related to verifying whether there was an implementation of Carnegie’s principles in in-article corporate social responsibility definitions. The data coded is included in Appendix A and the distribution of occurrence is specified in Table 2.

Table 2.

Journal title and number of articles per journal in the review.

Corporate social responsibility is a very popular topic in the management literature—the research sample was dispersed over 119 management journals, yet 44.87% of reviewed papers are concentrated in upper 8.8%.

From 1950 to 2000, the published number of CSR-related works was insignificant statistically (<0.03; exception 1981–1990). Yet, since 2001, there has been forceful, higher-than-exponential, growth of these articles. According to this trend, it is entitled to claim that the next years will multiple this tendency (Table 3).

Table 3.

The percentage of selected works and time intervals.

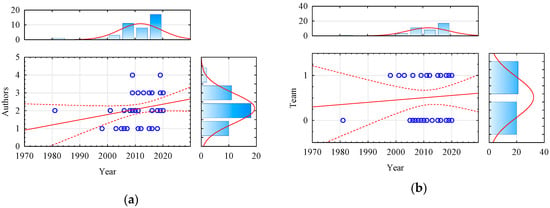

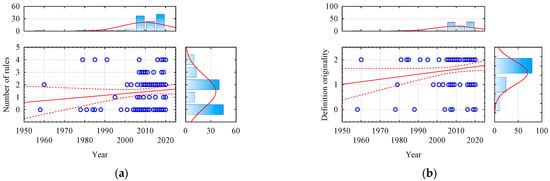

Referring to the number of authors per paper, the conducted research indicated a moderate strong correlation with the number of domestic authors (Figure 2a) and a very weak correlation in the context of international teams to domestic and individual ones (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Number of domestic authors—timeline; (b) Number of international teams.

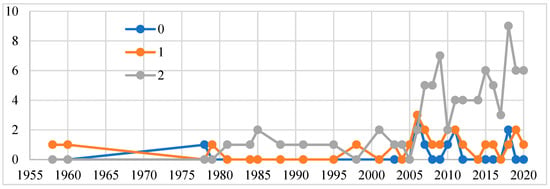

Each year the average number of single and domestic authors increased by 0.029. In that context, an in-depth analysis was implemented. The papers, depending on the content, were divided into three elements:

- author(s) construct their own definition of CSR (0),

- author(s) do not construct any CSR definitions (1),

- author(s) construct their own definition by modifying someone else’s (2) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Characteristics of CSR definitions in reviewed scientific papers.

Figure 3. Characteristics of CSR definitions in reviewed scientific papers.

Until the publication of Bowen [44], the paradigm developed by A. Carnegie had been widely accepted in religious commandments, as mentioned above. Yet, increasing the number of operating corporations and their development, drove the movement of CSR from an individual to a corporate approach [45,46]. With an increasing number of publications, there was also the growth of modifications/adjustments of the definition of CSR to its research correlate (market share, efficiency, brand awareness, consumer behavior), as well as in the frequency of adopting CSR as an axiom, which is particularly evident in the last fifteen years. The multitude of modifications has not resulted in a consensus on the development of a common, universally accepted definition of corporate social responsibility (Figure 4).

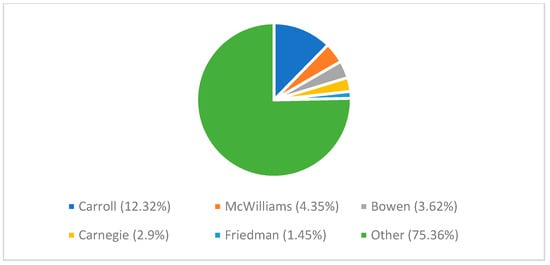

Figure 4.

Distribution of CSR definitions quoted in research work under investigation.

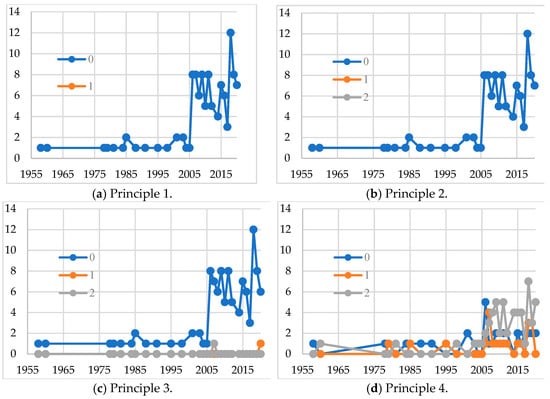

The scholars (Appendix A) in over 75% of papers implement (directly or axiomatically) the CSR definitions of their predecessors, ones which sanction and support their research aims, which confirms the conclusions of Devinney et al. [47] and Sheehy [22]. Only 2.9% of the abovementioned definitions are based, according to the claims of the authors, on Carnegie’s concept. Hence, the answer to RQ1 is negative. To address RQ2, an analysis of the eight Carnegie principles cited above was implemented, referring to the publication year and the number of papers. There were three possible outcomes: 0—principle nonexistence, 1—principle existence, 2—inability to specify (according to the content) (Appendix A) (Figure 5a–h).

Figure 5.

The acceptation of Carnegie’s principles—timeline.

Referring to the conducted research, in none of the papers reviewed did the author(s) take into consideration both voluntarism and anonymity as integral elements of a CSR definition (Figure 5a,b). Furthermore, 0.79% of the author(s) declared noneffectiveness-based rationales in corporate social responsibility construction (Figure 5c). The academics also did not acknowledge the traditional aspect of philanthropy (26.7%) or find this element negligible (46.7%) with a noticeable upward trend since 2005 (Figure 5d). Facilitating access to information and knowledge also did not, until 2017, constitute any priority in the context of defining CSR. Yet, starting from the aforementioned year, this process has been reversing (Figure 5e,f), as have maintaining human relations and peace on earth (Figure 5g,h) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Average annual growth rate of the number of articles fulfilling the given Carnegie principle—regression analysis.

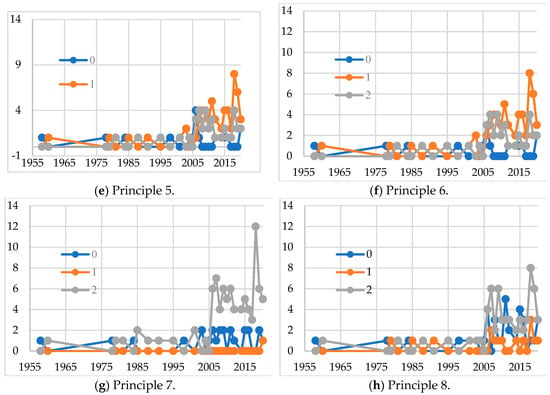

The number of Carnegie’s principles implemented in corporate social responsibility definitions increase slightly in timeline. Although principles’ no-existence is a current practice in published CSR related papers, the growth of positive trend is 0.014 a year (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

(a) Number of implemented principles; (b) CSR definition originality.

This study shows that 69.9% of in-article CSR definitions are reconstructed by author(s) in the context of the research principles, and in 21.2% of papers corporate social responsibility is treated axiomatically (Figure 6b). The “new” definition is included in 8.8% of works. The research results indicate the faster incrementation of converted definitions than original ones.

From the eight Carnegie principles, the first two are nonsignificant and not even taken into consideration. The rest of them are relevant for academics and practitioners as long as they enable one to increase the level of effectiveness (directly or indirectly). The Carnegie principles in much of temporary CSR-dedicated academic and organizational-related literature are narrowed and biased toward a direction correlated with a particular interest of the researcher, which multiplies the semantic and organizational chaos (RQ2).

4. Discussion and Future CSR Research Opportunities

Addressing RQ1, based on the research results from this study of the CSR related scientific literature, it is impossible to distinguish a commonly accepted, unequivocal definition of corporate social responsibility. Although the popularity and the concentration of the subject seems to be at the maximum level (see Table 2), the number of CSR-related papers increases exponentially (Table 3), as well as the quota of “new CSR definitions” (Figure 3), wherein the number of papers written by one or more domestic authors (Figure 2a) grows faster than in international ones (Figure 2b). Despite the abovementioned complexity, referring to the conducted analysis, three main trajectories in the context of what CSR means for corporations today were identified.

The first of them is related to the question of why a business should adopt CSR [48,49,50]. Normative arguments underlying a need for CSR are grounded on instrumental or ethical rationales [51,52]. The opposing ones are based on institutional function or property rights perspectives [53,54,55]. Ethical justifications are derived from religious fundamentals, philosophical frameworks, or prevailing social norms [2,56,57,58] and the protagonists of ethics claim that corporations are obliged to act in a socially responsible manner based on moral correctness [59,60]. In its extreme form, ethics-based CSR believers would force such a behavior regardless of whether or not it involved counterproductive resource expenditure for an institution [61,62]. In that aspect, the common instrumental arguments increasing the value of CSR implementation are based on a rational assumption that CSR activity will benefit the corporation over time [63,64]. Hence, performing, responsible corporations can: proactively anticipate potential objections to their actions; postpone governmental scrutiny; exploit opportunities arising from increasing the level of cultural, environmental, and sexual awareness; differentiate its products from those of less-proactive competitors; and continue to privilege economic rationality [54,65].

The second approach takes into consideration the argument why corporations should not implement CSR. In this context, it is particularly important to point out that, in the beginnings of the twentieth-century history of CSR, it was treated as a socialist conspiracy [44,66,67]. The sole obligation and responsibility of the corporation is to generate profits for its owners. A case against CSR is established on corporate function and property rights. On the other hand, the institutional function argument indicates that noncorporate agents like governments, labor unions, and religious and civic institutions are the only appropriate ones for pursuing social responsibility. Corporate owners/managers are not skilled enough or do not have sufficient time to act toward public policy. This statement releases corporations from accountability for their actions [66,68]. The property rights concern against social responsibility is rooted in neoclassical capitalism. It is influential through its simplicity and resonance, particularly in financial services. This perspective claims that the only obligation of managers is to operate in favor of the stakeholder value [69,70,71]. Any counterproductive behaviors constitute a violation of the management’s moral and legal obligations.

The third perspective is grounded in criticism of CSR. The implementation of ethics into the modern business organization is, referring to Carnegie’s principles, an excellent conception. Yet, according to Zizek [72], the current use of business ethics, including intimation towards sustainability/responsibility, is misleading if it does very little to modify the systemic negativity of organizational harmfulness [73,74]. There are examples, and CSR capitalizes on some of these negativities [75]. Moreover, there is a growing criticism of CSR scholarship both in academic and business environments that claims much CSR discourse in corporations plays an ideological role by lending a tokenistic element of ethicality to an inherently unethical organizational stage [76]. In the author’s opinion, CSR can be perceived as a cynical vehicle to enhance a reputation [77,78] or state that CSR is disingenuous, diversionary, and demonstrates the extent to which multinational corporations’ activities are “far away” from ethical. Further, Fleming and Jones [79], as well as Shamir [80], argue that CSR is a key factor for extending market rationality onto the social world. With the foundations of neo-liberalism and the privatization of crucial parts of society, corporate social responsibility becomes a driver in corporatizing non/anti-business parts of life (e.g., human resource management, ecology, environmental protection, ethical branding), gaining powerful leverage over activities that might once have been performed outside of business.

These abovementioned trends, although embodied in quite opposite approaches, are rooted in 1953, when H. R. Bowen published The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman claiming CSR as “the obligation of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of objectives and values of our society” (and, ipso facto, extracted Carnegie’s voluntarism, anonymity, and freedom of choice from the conception of CSR) [44] (p. 6). Moreover, the author did not specify who should be that demiurge who would know what the best for society was, as the corporations were usually managed by boards of directors [81]. As a consequence, he established the foundations of the “CSR Augean stable”.

In 2020, there is still no agreement in the context of what a precise definition of CSR should be [44,82]. For example, Dahlsrud [2] identified 37 definitions of CSR, and Carroll and Shabana [83] claim that even this number may be underestimated. Referring to the review conducted, one of the most cited conceptions is that proposed by Carroll [84], who perceived CSR as “the social responsibility of business that encompasses the economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary expectations that society has of organizations at a given point in time” [85] (p. 500). This statement is consistent with the general tendency of recent works to consider CSR as a context-specific and socially constructed concept [86,87]. Furthermore, the abovementioned Dahlsrud [2] claims that while there is unanimity among the scholars in identifying social, environmental, economic, stakeholder, and voluntariness dimensions as foundations of CSR (see [44,88,89,90]), heterogeneity springs up in the context of defining CSR as a “socially constructed” approach [91,92]. As such, it is not possible to construct an unbiased and all-encompassing definition of CSR, because what CSR is depends on context-specific elements and on the relations of an individual organization with its stakeholders [93,94,95]. This complexity is naturally incompatible with a “universal” definition of CSR [2,83], which is also inconsistent with Carnegie’s principles 1-4,8. In the same context, Okoye [86] claims that CSR is an “essentially contested concept” because of the complex and competing perspectives and issues, and, as such, it does not need any universal and widely accepted definition. Yet, this statement echoes the definitional dispersion in reviewed literature and implies the necessity of measuring the CSR strategy against a reference point, narrowed down to the specificity of the organization and to its relationships with its stakeholders, instead of comparing it to a general and unequivocal definition [87,96,97]. This reflection has been distorting academic growth for the past 50 years and, according to the research results, this tendency will intensify (particularly in the context of implementing rules four through eight) (Table 4). It is increasingly discussed in management journals, including the most prestigious ones (e.g., Academy of Management Journal [97,98], Journal of Business Ethics [99,100,101]) or even devoted ones (Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management [102,103,104]). The abovementioned statement is confirmed in the research results (Figure 4). The world of science is not in the “search for excellence” mode—over 75% of scholars created their own CSR definition. In that context, the paramount point for the conceptualization of the sense of CSR is the context in which scientific discourse is set, which was indicated in the conducted research (see: Table 3, Figure 6a,b). Moreover, the organizational activities propelling business, the ideological matrix, and corporate formulation based on economic rationality inevitably transfer most responsibility gestures (e.g., sustainability, stakeholder dialogue, environmental protection, societal philanthropy) into a farce: the maximum number of accepted Carnegie’s principles in reviewed papers is four and there are articles where these principles are ignored completely, which confirms the conclusions of Alexander and Buchholz [89], Doh and Guay [105], and Agunis and Glavas [90]. The idea that the logic of today’s corporation might be reconstructed to consider social issues beyond economic rationality stands in contradiction to capitalistic foundations [80,81,106,107,108], which is particularly reflected in the negation of fourth Carnegie’s principle (Figure 5b). Moreover, there is a deep incompatibility between what can be expected as ethical organizational citizenship and the core sense of organizational existence (e.g., gaining profits, market shares, competitive advantage, reducing costs) [109,110,111,112]. This is the conduct of business that will always take priority over other elements of organizational activity, because that is the cause of establishing enterprises [113]. In the opinion of Bansal and Clelland [114], much of what CSR proclaims can be perceived as either wishful thinking or simply propaganda, designed to create the false image of the company in the eyes of consumers, environmental protectionists, society, or other potential groups of interest. These circumstances are also reflected in the review conducted. Historical origins indicate that the CSR concept never existed as there were no voluntary activities. Every individual in their economic activity (hunting, production, trade, breeding) had a habit or ostracism-related obligation to share income with the community. Thus, Carnegie’s principles can only be perceived as a utopia-based construct in these boundary conditions, particularly in temporary, highly competitive organizational environment. Moreover, the majority of scientific efforts only generate the multiplication of further unclear, biased CSR approaches, although, according to the research results, from 2017 onward positive changes have been observed in the human resource management field (Figure 6a). Yet, the crucial criticism is based on the idea of fair price. Corporations charge as much as they can or are allowed to under the market environment [115,116,117], therefore the question of corporate morality (e.g., [118,119]) and implementing an idea to charge less, leave the surplus in “customers’ pockets”, and let a society decide what to spend their money on, instead of a corporation overthinking the god complex, arises (see [120]). This paradigm, together with the extremely opposite approach of Friedman [121] are distant boundaries of the corporate social responsibility concept, where both Carnegie’s principles and temporary management CSR approaches operate [RQ2].

Despite of abovementioned complexity, the core corporate social responsibility concept is still accessible for proper investigation today [RQ3]. The suggestion based on Carnegie’s principles is to survey those company owners who donate their surpluses anonymously, instead of questioning all the boards of directors, officers, presidents, or stakeholders. This research method, according to Hensel [122], determines the path of correctness in future scientific CSR research. The example of Charles Feeney proves this would be an appropriate scientific direction to establish a holistic, commonly accepted concept of socially responsible philanthropy.

5. Conclusions and Limitations

This study is a combined SLR and bibliometrics of CSR-related management literature, which identified and analyzed 119 articles published from January 1950 to July 2020 and 19 books issued from January 2010 to July 2020.

As the first contribution, this research provides a clear picture of the recent trends in CSR literature by identifying works referring to several significant features, such as the research context, the author/team characteristics, the content of CSR definitions and approaches, as well as the implementation of Carnegie’s principles. Beginning from this analysis of the main trends and gaps identified in a reviewed discipline, e.g., a lack of commonly accepted CSR definition, infinite freedom in establishing CSR in spite of scientific rigor. I also found that, in the investigated CSR-related management literature, the term of corporate social responsibility is also perceived as paradigm or a narrowed/biased fulcrum to achieve a research aim.

As regards the content of recent CSR research, the conducted analysis identified three stages of corporate social responsibility development: (1) the early pre-CSR stage when social involvement (engagement) was implemented based on religious or tribal obligations (under threat of social ostracism) and corporations did not exist; (2) one person philanthropy (the late pre-CSR stage)—after the publication of Carnegie’s ”The Gospel of Wealth” in 1889 (limited number of corporations); (3) the real CSR stage, which began with Bowen’s work in 1953.

Stage one was characterized by no free will and it did not fulfill the criteria of temporary CSR understanding in the world of science [2,3]. Yet, the core, according to research results, contribution to the field of CSR development was establishing the foundations of activity (freedom-of-choice-oriented or not) implemented later by Carnegie and his successors in stage two, in which the coherent principles of philanthropy were established. The work The Social Responsibilities of the Businessman, although very valuable, determined scientific and organizational dispersion in the corporate social responsibility field, which aims at the general conclusion that CSR research is heterogeneous and fragmented, with very different dynamic issues and research context investigated. Therefore, this paper it is the first attempt to, in spite of scientific diagnosis, indicate future opportunities and threats in the context of CSR development, based on the unbiased, stage two principles, which represent a novelty compared with previous literature reviews. Given this, a combined SLR and bibliometrics analysis is extremely important to guide future research endeavors aimed at building a coherent body of knowledge.

A second contribution of this paper to CSR development is that it provides an updated picture of the use of corporate social responsibility in the managerial strategies of organizations. This contribution is particularly significant for the future effectiveness of corporate philanthropy operations.

The third of this article’s contributions is an in-depth analysis of “The Gospel of Wealth” and the isolation of eight principles that, according to Carnegie, are fundamental for effective philanthropy and comparing them to the content of contemporary management literature. The results of abovementioned analysis allowed me to estimate current and future trends in the world of science. Per the research results, there is a strong need for the clarification and unification of the CSR concept both in academia and organizational environments to maintain further Corporate Social Responsibility development. Analyzing Carnegie’s work, it is possible to indicate one element of his legacy confirming the abovementioned theses: the author claimed the most effective philanthropy activity is included in the statement ”This is not wealth, but only competence, which it should be the aim of all to acquire”. Competency is the one ultimate principle [18] (p. 6).

In conclusion, I underline strengths and limitations of this study. Referring to the strengths, I adopted an unequivocal and rigorous approach to the literature review. I also made careful selection of works, focusing on those that were management oriented and strictly related to the corporate social responsibility field. Regarding limitations, I focused on three databases: Business Source Ultimate, Academic Search Ultimate, and eBook Collection and works that fulfilled stringent quality and content criteria. Therefore, many papers were excluded. Moreover, my suggestions for future research have been identified based on the literature analysis. I recognize this approach could limit creativity and innovation in CSR field, yet, it can be a strong foundation for brainstorming future research streams to enrich the CSR literature and offer support to CSR management directors and officers.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Engaged EBSCO papers, Systematic Literature Reviews, Press article and Books in the Analysis.

Table A1.

Engaged EBSCO papers, Systematic Literature Reviews, Press article and Books in the Analysis.

| EBSCO Papers | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Autor/year of publication | Published in | Primal CSR definition [o/i/n] | Carnegie’s principles fulfilment [y/n/u] | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| 1 | Abbott, W.F. Monsen, R.J. (1979) | Academy of Management Journal | N | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| 2 | Aguilera, R. et al. (2007) | Academy Management Review | O | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| 3 | Aguinis, H., Glavas, A. (2012) | Journal of Management | N | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| 4 | Alexander, G.J., Buchholz, R.A. (1978) | Academy of Management Journal | N | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| 5 | Amor-Esteban et al. (2020) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | Authors claim voluntarism based disclosure | y/n | n | y | u | n | n | u | n |

| 6 | Andrei, J.V. et al. (2018) | Economics, Management & Financial Markets | O, narrowed to HRM | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| 7 | Arya, B., Zhang, G. (2009) | Journal of Management Studies | O, narrowed to monetary initiatives | n | n | n | y | u | u | u | u |

| 8 | Aupperle, K.E. et al. (1985) | Academy of Management Journal | I (A. Carrol’s) | n | n | n | n | n | n | u | n |

| 9 | Barnett, M.L. (2007) | Academy of Management Review | O, narrowed to financial return | n | n | n | y | u | u | u | u |

| 10 | Barnett, M.L. and Salomon, R.M. (2006). | Strategic Management Journal | N | n | n | n | y | u | u | u | u |

| 11 | Barrena-Martinez, J. et al. (2019) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | O, narrowed to HRM | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| 12 | Basu, K., Palazzo, G. (2008) | Academy of Management Review | O, based on Carnegie’s | n | n | n | y | y | y | n | n |

| 13 | Berger, I.E. et al. (2007) | California Management Review | O, marked outcome oriented | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | u |

| 14 | Boal, K.B. and Peery, N. (1985) | Journal of Management | I, Zenisek (1979) | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| 15 | Calvo, N., Calvo, F. (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | I, Carnegie’s, narrowed to HR | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | u |

| 16 | Campbell. J.L. (2007) | Academy of Management Review | N | u | u | u | y | u | u | u | u |

| 17 | Carlini, J. et al. (2019) | Journal of Marketing Management | N, narrowed to brand | n | n | n | y | u | u | u | u |

| 18 | Carroll, A.B. (1991), (2008) | Business Horizons | O, four-dimensional | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | y |

| 19 | Carroll, K.M., Shabana, P.R. (2010) | Corporate Social Responsibility Across Europe | O | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | y |

| 20 | Chen, Y.-H., et al. (2016) | Australian Economic Papers | O, negative relation with economic and social welfare | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| 21 | Chang, C.-H. (2015) | Management Decision | N | n | n | n | y | u | u | u | u |

| 22 | Clacher, I., Hagendorf, J. (2012) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Friedman’s | n | n | n | y | u | u | u | u |

| 24 | Clarkson, M. (1995) | Academy of Management Review | I, Carrol’s | n | n | n | y | u | u | u | u |

| 25 | Cooke, F. L., He, Q. (2010) | Asia Pacific Business Review | N | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | n |

| 26 | Davies, I.A., Crane, A. (2010) | Business Ethics A European Review | I, Yin (1994) | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 27 | De Beelde, I., Tuybens, S. (2015) | Business Strategy and the Environment | I, Companies’ reports based | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 28 | De Roeck, K. et al. (2014) | The International Journal of Human Resource Management | I, Bhattacharya et al. 2009). Psychological dimension | n | n | n | u | n | n | u | n |

| 29 | Doh, J.P., Guay, T.R. (2006) | Journal of Management Studies | I, McWilliams, 2001), politically oriented | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| 30 | De Stefano, F. et al. (2018) | Human Resource Management | I, Carroll (1979) | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| 31 | Diaz-Carrion, R. (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | O, focused on external elements | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | y |

| 32 | Drucker, P.F. (1984) | California Management Review | O, claims CSR does not exist | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| 33 | Einwiller, S. et al. (2019) | Journal of Business Research | N | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 34 | Fassin, Y. (2008) | Business Ethics: A European Review | I, Carroll, narrowed to reports | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | u |

| 35 | Forcadell, F. J., Aracil, E. (2017) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | I, Ruiz et al. (2014) | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 36 | Frederick, W.C. (1960) | California Management Review | N | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 37 | Fuentes-Garcia, F. J. et al. (2008) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Carrol | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | y |

| 38 | Giannarakis, G. et al. (2014) | Management Decision | I, Carrol | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 39 | Godfrey, P. C., Hatch, N. W. (2007) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, McWilliam (2001) | n | n | n | n | y | y | n | y |

| 40 | Godfrey, P. C. et al. (2009) | Strategic Management Journal | I, McWilliam (2001) | n | n | n | n | y | y | n | y |

| 41 | Godkin, L. (2015) | Journal of Business Ethics | O, ethical voice of employees | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 42 | Gond, J.-P. et al. (2011) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Bowen’s (1953), employee involvement relation | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | n |

| 43 | Greenwood, M. (2007) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, BSR (2006) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 44 | Gupta, M. (2017) | Review of Professional Management | O, Friedman | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 45 | Gupta, N., Sharma, V. (2016) | IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior | I, Carroll | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | n |

| 46 | Hahn, T. et al. (1018) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, WCED (1987) | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 47 | Hallin, A., Gustavsson, T.K. (2009) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | I, Dahlsrud’s conception imlpemented | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 48 | Hoque, N. (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management. | O | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 49 | Hur, W.M., et al. (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management. | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 50 | Hur, W.M., et al. (2014) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Bhattacharya (2004) | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 51 | Husted, B.W., Allen, D.B. (2006) | Journal of International Business Studies | N | n | n | n | u | n | n | n | n |

| 52 | Iglesias, O. et al. (2020) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Reputation Institute (2016) | n | n | n | n | n | n | u | u |

| 53 | Jamali, D. R. et al. (2015) | Business Ethics: A European Review | I, Erondu et al. (2004) | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | n |

| 54 | Klimkiewicz, K., Oltra, V. (2017) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | I, McElhaney, 2008) | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | u |

| 55 | Kumar, T. et al. (2020) | IBA Journal of Management & Leadership | I, Churchill (1979) | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 56 | Lam, H., Khare, A., (2010) | Journal of International Business Ethics | I, Joseph (2009) | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 57 | Lee, M-D.P. (2008) | International Journal of Management Reviews | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 58 | Lis, B. (2012) | Management Revue | I, Greening, Turban (2000), narrowed to HRM | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | u |

| 59 | Lis, B. (2018) | Journal of General Management | I, Backhaus et al. (2003) | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | u |

| 60 | Levitt, T. (1958) | Harvard Business Review | N | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| 61 | Lichtenstein, D.R. et al. (2004) | Journal of Marketing | I, Smith (2003) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 62 | Lin, C.-P., Y. et al. (2012) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Carroll | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | n |

| 63 | Lockett, A. et al. (2006) | Journal of Management Studies | O | n | n | n | n | n | y | u | n |

| 64 | Luo, X., Bhattacharya, C.B. (2006) | Journal of Marketing | O | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 65 | Luu, T.T. (2019) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Carroll, narrowed to client’s approach | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 66 | Mackey, A. et al. (2007) | Academy of Management Review | I, Godfrey (2004) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 67 | Martínez-Garcia, E. et al. (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | I, Celma et al. (2014) | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | n |

| 68 | Mason, C., Simmons, J. (2014) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Dobers and Springett (2010) | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | y |

| 69 | Mason, C., Simmons, J. (2011) | Business Ethics: A European Review | O | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | n |

| 70 | Matten, D., Moon, J. (2008) | Academy of Management Review | I, Tempel and Walgenbach (20I07) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | n |

| 71 | Maroli, L., Manickavasagam, V. (2019) | International Journal of Management & Information Technology | I, Companies Act (2013) | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | n |

| 72 | McGuire, J.B. et al. (1988) | Academy of Management Journal | I, Quinn, Mintzberg, James (1987), narrowed to organizational performance | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 73 | McWilliams, A., Siegel, D. (2001) | Academy of Management Review | I, Friedman (1970) | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | n |

| 74 | McWilliams, A., Siegel, D. (2011) | Journal of Management, | O | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | n |

| 75 | McWilliams, A. et al. (2006) | Journal of Management Studies | O | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | u |

| 76 | Miller, S.R. (2020) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Doh et al. (2010) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 77 | Mirvis, Ph. (2012) | California Management Review | O, narrowed to HRM | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 78 | Mishra, S., Suar, D. (2010) | Journal of Business Ethics | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 79 | Nikolaeva, R., Bicho, M. (2011) | Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | I, GRI (1999) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | n |

| 80 | Perry, P. et al. (2015) | Journal of Business Ethics | O, based on ethical considerations | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | n |

| 81 | Porter, M.E. Kramer, M.R. (2006) | Harvard Business Review | I, Carnegie | n | n | n | n | n | n | u | n |

| 82 | Preuss, L., et al. (2009) | International Journal of Human Resource Management | I, Caroll | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 83 | Preuss, L., et al. (2016) | Business Ethics Quarterly | I, Caroll | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 84 | Ramchandran, V. (2011) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | I, Porter | n | n | n | y | y | y | n | n |

| 85 | Ramchander, S., et al. (2011) | Strategic Management Journal | I, McWilliams, index related definition | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 86 | Reich, R.B. (1998) | California Management Review | N | n | n | n | u | n | n | n | n |

| 87 | Rettab, B. (2009) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, McWilliams | n | n | n | n | y | y | n | n |

| 88 | Sen, S., Bhattacharya, C.B. (2001) | Journal of Marketing Research | I, Brown and Dacin (1997) | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 89 | Shen, J. (2011) | International Journal of Human Resource Management | N | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 90 | Scherer, A.G. Palazzo, G. (2011) | Journal of Management Studies | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | U | u |

| 91 | Sen, S., Bhattacharya, C.B. (2006) | Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | N | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 92 | Sheel, R. C., Vohra, N. (2016) | International Journal of Human Resource Management | N | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | n |

| 93 | Silvestri, A., Veltri, S. (2020) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | O, leaders’ motivation | n | n | n | n | y | y | n | n |

| 94 | Simionescu, L.N., Dumitrescu, D. (2018) | Sustainability | I, Bowen (1953) | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 95 | Smith N.C. (2003). | California Management Review | I, Carnegie | n | n | n | n | y | y | n | u |

| 96 | Soni, D., Mehta, P. (2018) | Journal of Strategic Human Resource Management. | O | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 97 | Sun, W. et al. (2019) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Sen et al. (2006) | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | u |

| 98 | Tokoro, N. (2007). | Asian Business & Management | N | n | n | n | u | n | n | u | u |

| 99 | Turner, M.R. et al. (2019) | Human Resource Management Review | I, Carnegie | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | u |

| 100 | Tuzzolino, F., Armandi, B.R. (1981) | Academy of Management Review | I, Carroll | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 101 | Uhlig, M. et al. (2020) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | I, Turker (2009) | n | n | n | u | y | y | y | y |

| 102 | van Huijstee, M., Glasbergen, P. (2008) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. | I, Dahlsrud (2006), narrowed to stakeholder approach | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | n |

| 103 | Vlachos, P.A. et al. (2009) | Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science | I, Progressive Grocer (2008), consumer related approach | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 104 | Vogel, D.J. (2005) | California Management Review | N | n | n | n | u | n | n | n | n |

| 105 | Wagner, T. et al. (2009) | Journal of Marketing | N | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 106 | Waheed, A., Yang, J. (2019) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | I, Arrive and Feng (2018) | n | n | n | n | y | y | u | u |

| 107 | Wang, Y. (2018) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | I, Yunus (2011) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 108 | Waples, C.J., Brachle, B.J. (2020) | Corporate Social, Responsibility & Environmental Management | I, Bowen (2013) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | n |

| 109 | Wheeler, C. et al. (2003) | Journal of General Management | N | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | n |

| 110 | Xu, S. et al. (2015) | Australian Journal of Management | I, Carroll | n | n | n | u | n | n | n | n |

| 111 | Yang, S.-L. (2016) | Quality & Quantity | I, Bowen (1953) | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| 112 | Ye, K., Zhang, R. (2016) | Journal of Business Ethics | I, Goss and Roberts (2009) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 113 | Young, S., Thyil, V. (2009) | Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources | I, Galbreath (2006) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 114 | Zou, J. (2015) | Frontiers of Business Research in China | I, Freeman (1984) | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | n |

| Systematic Literature Reviews | |||||||||||

| No. | Autor/year of publication | Published in | Primal CSR definition [o/i/n] | Carnegie’s principles fulfilment [y/n/u] | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| 1 | Dahlsrud, A. (2006) | Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 2 | Tiba, S. et al. (2019) | Corporate Social Responsibility & Environmental Management | I, Carroll | n | n | n | n | y | y | n | u |

| 3 | Real de Oliveira, E. (2013) | Journal of Knowledge Economy & Knowledge Management | I, Davies and Crane (2010) | n | n | n | u | y | y | n | n |

| 4 | Wang, S., Gao, Y. (2016) | Irish journal of management | I, Carroll | n | n | n | y | y | y | u | y |

| Press Article | |||||||||||

| No. | Autor/year of publication | Published in | Primal CSR definition [o/i/n] | Carnegie’s principles fulfilment [y/n/u] | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| 1 | Friedman, M. (1970) | New York Times Magazine | N | n | n | n | n | n | n | u | u |

| Books | |||||||||||

| No. | Autor/year of publication | Published in | Primal CSR definition [o/i/n] | Carnegie’s principles fulfilment [y/n/u] | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| 1 | Carroll, A.B., Shabana, P.R. (2010) | Springer | O | n | n | u | y | y | n | n | u |

| 2 | Carroll, A.B., (2008) | Oxford University Press | O | n | n | u | y | y | n | n | u |

| 3 | Demmerling, T. (2015) | Anchor Academic Publishing | I, Crowther, Capaldi (2012) | y | n | n | y | y | y | u | u |

| 4 | Dyck, R. (2014) | Bentham Science Publishers | N | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u |

| 5 | Feller, J. (2016) | Anchor Academic Publishing | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 6 | Frederick, W.C. (2006) | Dogear Publishing | N | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 7 | Frederick, W.C. (2008) | Oxford University Press | N | n | n | n | u | y | y | u | u |

| 8 | Idowu, S.O. (2014) | Routledge | N | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 9 | Kotler, P., Lee, N. (2005) | Wiley | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u | |

| 10 | Kurucz, E. et al. (2008) | Oxford University Press | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 11 | Leal F., W. (2010) | Routledge | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u | |

| 12 | Louche, C. et al. (2010) | Routledge | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 13 | Newell, A.P. (2014) | Nova Science Publishers, Inc | I, Carroll (1979) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 14 | Sun, William et al. (2010) | Emerald Group Publishing Limited | I, Carroll (1979) | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

| 15 | Pompper, D. (2018) | Emerald Publishing Limited | N | n | n | n | n | y | y | y | u |

| 16 | Rajak, D. (2011) | Stanford University Press | N | u | u | u | u | u | u | u | u |

| 17 | Tench, R. et al. (2018) | Emerald Publishing Limited | N | n | n | n | n | u | u | u | u |

| 18 | Weber, J., Wasieleski, D.M. (2018) | Emerald Publishing Limited | N | n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| 19 | Werther, W.B., Chandler, D. (2006) | Sage Publications Ltd | N | n | n | n | u | u | u | u | u |

References

- Available online: https://www.carnegiefoundation.org (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Dahlsrud, A. How Corporate Social Responsibility is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2008, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real de Oliveira, E.; Ferreira, P.; Saur-Amaral, I. Human resource management and corporate social responsibility: A systematic literature review. J. Knowl. Econ. Knowl. Manag. 2013, 8, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Gao, Y. What do we know about corporate social responsibility research? A content analysis. Ir. J. Manag. 2016, 35, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Commitment to sustainable development: Exploring the factors affecting employee attitudes towards corporate social responsibility-oriented management. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiba, S.; Rijnsoever, F.J.; Hekkert, M.P. Firms with benefits: A systematic review of responsible entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility literature. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulfson, M. The Ethics of Corporate Social Responsibility and Philanthropic Venturesl. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 29, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winch, G.M. Project organizing as a problem in information. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2015, 33, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valackienė, A.; Dėmenienė, A. Knowledge Management: The Development of Testing Portal for Selection of Profession. Eng. Econ. 2007, 52, 59–64. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, C.; Maclean, M.; Gordon, J.; Shaw, E. Andrew Carnegie and the foundations of contemporary entrepreneurial philanthropy. Bus. Hist. 2011, 53, 425–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, P. The Pacifism of Andrew Carnegie and Edwin Ginn: The Emergence of a Philanthropic Internationalism. Glob. Soc. J. Interdiscip. Int. Relat. 2015, 9, 530–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ris Ethan, W. The Education of Andrew Carnegie: Strategic Philanthropy in American Higher Education, 1880–1919. J. High. Educ. 2017, 88, 401–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhulina, A. Performing Philanthropy from Andrew Carnegie to Bill Gates. Perform. Res. 2018, 23, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, W.R. Considering Carnegie’s Legacy in the Time of Trump: A Science and Policy Agenda for Studying Social Class. J. Soc. Issues 2019, 75, 356–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, E.C. The new Gospel of Wealth: On social impact bonds and the privatization of public good. Houst. Law Rev. 2018, 56, 153–221. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, C.; Gordon, J.; Maclean, M. The Ethics of Entrepreneurial Philanthropy. J. Bus. Ethics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bø, E.E.; Halvorsen, E.; Thoresen, E.; Thor, O. Heterogeneity of the Carnegie Effect. J. Hum. Resour. 2019, 54, 726–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnegie, A. Gospel of Wealth; Carnegie Corporation of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.carnegie.org/publications/the-gospel-of-wealth/ (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Rerum Novarum. Available online: http://www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_15051891_rerum-novarum.html (accessed on 23 October 2020).

- Janowski, A. Zarządzanie Talentami w Kontekście Efektywności Organizacji na Przykładzie Zakładów Ubezpieczeń na Życie; Difin: Warszawa, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeny, B. Understanding CSR: An empirical study of private regulation. Monash Univ. Law Rev. 2012, 38, 103–127. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy, B. Defining CSR: Problems and Solutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, B. Conceptual and institutional interfaces among CSR, corporate law and the problem of social costs. Virg. Law Bus. J. 2017, 12, 95–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehy, B.; Farneti, F. Corporate Social Responsibility, Sustainability, Sustainable Development and Corporate Sustainability: What Is the Difference and Does It Matter? The University of Sydney—Discipline of Accounting. 2020. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3549577 (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Rahdari, A.; Sheehy, B.; Khan, H.Z.; Braendle, U.; Rexhepi, G.; Sepasi, S. Exploring global retailers’ corporate social responsibility performance. Heliyon 2020, 6, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, L.; Vishwanath, B.; Seele, P.; Cottier, B. Are We Moving Beyond Voluntary CSR? Exploring Theoretical and Managerial Implications of Mandatory CSR Resulting from the New Indian Companies Act. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.; Valentinov, V.; Hedingsfelder, M.; Perez-Valls, M. CSR beyond Economy and Society: A Post-capitalist Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 4, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Franco, G.; Montalvan-Burbano, N.; Carrion-Mero, P.; Apolo-Masache, B.; Jaya-Montalvo, M. Research Trends in Geoturism: A Bibliometric Analysis Using the Scopus Database. Geosciences 2020, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H.G. A Co-Citation Model of a Scientific Specialty: A Longitudinal Study of Collagen Research. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1977, 7, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, A.; Jones, O. Editorial: Strategies for the development of International Journal of Management Reviews. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boell, S.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D. On being ‘systematic’ in literature reviews in IS. J. Inf. Technol. 2015, 30, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, R. Beyond being systematic in literature reviews in IS. J. Inf. Technol. 2015, 30, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producting a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, A. Statistical Bibliography or Bibliometrics? J. Doc. 1969, 25, 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green Supply Chain Management: A Review and Bibliometric Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Nederlands, 2015; p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- Keatley-Herring, H.; Van Aken, E.; Gonzales-Aleu, F.; Deschamps, F.; Letens, G.; Orlandini, P.C. Assessing the maturity of a research area: Bibliometric review and proposed framework. Scientometrics 2016, 109, 927–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, P.; Menfe, V.; Romano, P. A Systematic Literature Review on Recent Lean Research: State-of-the-art and Future Directions. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 579–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, P.A.M.; Martines, M.V.; Rambaud, C. Corporate Social Responsibility: A bibliometric Research. Encycl. Bus. Prof. Ethics 2020. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, D.; Denyer, D. Researching Tomorrow’s Crisis: Methodological Innovations and Wider Implications. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2013, 15, 205–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisneros, L.; Ibanescu, M.; Keen, C.; Lobato-Calleros, O.; Niebla-Zatarin, J. Bibloimetric Study of Family Business Succession between 1939 and 2017: Mapping and Analyzing Authors’ Networks; Springer International Publishing: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; p. 117. [Google Scholar]

- Cunliffe, A.L. Crafting Qualitative Research: Morgan and Smircich 30 Years on. Organ. Res. Methods 2011, 14, 647–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkar, A.R.; Bhatt, D.D. Perception of Researchers; Academicians of Parul University towards Research Data Management System; Role of Library: A Study. DESIDOC J. Libr. Inf. Technol. 2020, 40, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Harper: London, UK, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Visser, W.; Tolhurst, N. The World Guide to CSR: A Country-By-Country Analysis of Corporate Sustainability and Responsibility; Sheffield: Routledge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Stefano, F.; Bagdadli, S.; Camuffo, A. The HR role in corporate social responsibility and sustainability: A boundary-shifting literature review. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlsrud, A. How Corporate Social Responsibility Is Defined: An Analysis of 37 Definitions; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. and ERP Environment: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; Available online: www.interscience.wiley.com (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Devinney, T.M.; Auger, P.; Eckhardt, G. The Myth of the Ethical Consumer; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hack, L.; Kenyon, A.J.; Wood, E.H. A Critical Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Timeline: How should it be understood now? Int. J. Manag. Cases 2014, 16, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunfowora, B.; Stackhouse, M.; Oh, W.-Y. Media Depictions of CEO Ethics and Stakeholder Support of CSR Initiatives: The Mediating Roles of CSR Motive Attributions and Cynicism. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 150, 525–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. CSR for HR: A Necessary Partnership for Advancing Responsible Business Practices; Sheffield: Routledge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Gómez-Miranda, M.E.; David, F.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. The explanatory effect of CSR committee and assurance services on the adoption of the IFC performance standards, as a means of enhancing corporate transparency Sustainability Accounting. Manag. Policy J. 2019, 10, 773–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, P.; Yam, S. Ethics and Law: Guiding the Invisible Hand to Correct Corporate Social Responsibility Externalities. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeequddin, M.; Waheed, K.A. Corporate Social Responsibility: Is It a Matter of Ethics? South Asian J. Bus. Manag. Cases 2012, 1, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, R. The End of Corporate Social Responsibility: Crisis; Critique, by Peter Fleming and Marc T. Jones. J. Bus. Bus. Market. 2014, 21, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailwood, S.A. Why “business’s nastier friends” should not be libertarians. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 24, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; Renyan, M.; Yue, H.; Lu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Isaeva, E.; Rocha, Á. The influence mechanism of organizational slack on CSR from the perspective of property heterogeneity: Evidence from China’s intelligent manufacturing. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 38, 7041–7052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniapan, B. The Roots of Indian Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Practice from a Vedantic Perspective. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Asia. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics; Governance; Low, K., Idowu, S., Ang, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, W.C. Corporation Be Good! The Story of Corporate Social Responsibility; Dog Ear Publishing: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.; Umrani, W. Corporate Social Responsibility. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1264–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.; Koh, K.; Liu, S.; Tong, Y.H. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Disclosures: An Investigation of Investors’ and Analysts’ Perceptions. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 507–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L. Stakeholder Influence Capacity and the Variability of Financial returns to Corporate Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiernik, B.M.; Ones, D.S. Ethical employee behaviors in the consensus taxonomy of counterproductive work behaviors. Int. J. Select. Assess. 2018, 26, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.; Carroll, A.; Hatfield, J.D. An Empirical Examination of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, N.; Calvo, F. Corporate social responsibility and multiple agency theory: A case study of internal stakeholder engagement. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1223–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgione, A.F.; Laguir, I.; Staglianò, R. Effect of corporate social responsibility scores on bank efficiency: The moderating role of institutional context. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2094–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, T. The Dangers of Social Responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1958, 36, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rebman, R. Corporate Responsibility, Catholic Social Teaching, and the Common Good: Reporting, Accountability, and Stakeholder Action. J. Cathol. Soc. Thought 2020, 17, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Yao, S.; Govind, R. Reexamining Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Value: The Inverted-U-Shaped Relationship and the Moderation of Marketing Capability. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 160, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, A.; Ferreira, J. Corporate social responsibility strategies: Past research and future challenges. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 885–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizek, S. Living in the End of Times; Verso: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Soin, M. CSR and the ethics of conviction. Ann. Etyka Zyciu Gospod. 2019, 22, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, S. Deceptive Advertising: A Corporate Social Responsibility Perspective. Int. J. Health Econ. Dev. 2020, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J. The Modern Firm: Organizational Design for Performance and Growth; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A.; Banerjee, T. Weaving Analytics for Effective Decision Making New Delhi, India; Sage Publications Pvt. Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.R.; Eden, L.; Li, D. CSR Reputation and Firm Performance: A Dynamic Approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 619–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Jones, M. The End of Corporate Social Responsibility: Crisis; Critique; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, R. The age of responsibilization: On market-embedded morality. Econ. Soc. 2008, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, P.F. The New Meaning of Corporate Social Responsibility. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1984, 26, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K.; Adi, A.B. Reconstructing the Corporate Social Responsibility Construct in Utlish. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2007, 16, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Social Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Miralles-Quiros, M.M.; Miralles-Quiros, J.L.; Arraiano, I.G. Are firms that con-tribute to sustainable development valued by investors? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, A. Theorising Corporate Social Responsibility as an Essentially Contested Concept: Is a Definition Necessary? J. Bus. Ethics Vol. 2009, 89, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanlon, G.; Fleming, P. Updating the critical perspectives on corporate social responsibility. Sociol. Compass 2009, 3, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amor-Esteban, V.; María Purificación, G.-V.; García-Sánchez, I.M. Bias in composite indexes of CSR practice: An analysis of CUR matrix decomposition. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1914–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, G.J.; Buchholz, R.A. Corporate Social Responsibility and stock market performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1978, 21, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agunis, H.; Glavas, A. What do we know and Don’t Know about Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.L. Self-Responsibility Gone Bad: Institutions and the 2008 Financial Crisis. Am. Behav. Sci. 2019, 63, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, I. Putting the s back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min-Dong, P.L. A Review of the Theories of Corporate Social Responsibility: Its Evolutionary Path and the Road Ahead. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2008, 10, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtens, B. Corporate social responsibility in the international insurance industry. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.; Shawtari, F.; Shamsudin, M.F.; Hussain, H.B.I. The consequences of integrating stakeholder engagement in sustainable development (Environmental perspectives). Sustain. Dev. 2017, 26, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, H.; Khare, A. HR’s Crucial Role for Successful CSR. J. Int. Bus. Ethics 2010, 3, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, C.T.; Hawn, O.V. Microfoundations of Corporate Social Responsibility and Irresponsibility. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 1609–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Corporate Social Responsibility and shareholder reaction: The environmental awareness of investors. Acad. Manag. J. 2013, 56, 758–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, C. The Relation between Policies Concerning Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Philosophical Moral Theories—An Empirical Investigation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, B.; Robertson, J.L.; White, K. How Co-creation Increases Employee Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Engagement: The Moderating Role of Self-Construal. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 166, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P.; Lindgreen, A.; Vanhamme, J. Industrial Clusters and Corporate Social Responsibility in Developing Countries: What We Know, What We do not Know, and What We Need to Know. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobers, P. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Ur Rehman, Z.; Ali Umrani, W. The moderating effects of employee corporate social responsibility motive attributions (substantive and symbolic) between corporate social responsibility perceptions and voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 27, 769–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gago, R.; Cabeza-García, L.; Godos-Díez, J.-L. How significant is corporate social responsibility to business research? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.P.; Guay, T.R. Corporate social responsibility, public policy and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbroner, R. The Nature and Logic of Capitalism; W W Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate social responsibility: A process model of sense-making. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P.; Roberts, J.; Garsten, C. Forget political corporate social responsibility. Organization 2013, 20, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojanovic, A.; Milosevic, I.; Arsic, S.; Urosevic, S.; Mihajlovic, I. Corporate Social Responsibility as a determinant of employee Loyalty and Business Performance. J. Compet. 2020, 2, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, L.M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainability from a Global, European and Corporate Perspective. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 13, 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hakobyan, N.; Khachatryan, A.; Vardanyan, N.; Chortok, Y.; Starchenko, L. The Implementation of Corporate Social and Environmental Responsibility practices into Competitive Strategy of The Company. Market. Manag. Innov. 2019, 2, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raúl, L.; Angel, J.A. Promoting Corporate Social Responsibility in Logistics throughout Horizontal Cooperation. Manag. Glob. Trans. Int. Res. J. 2014, 12, 79–93. [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu, L.N.; Dumitrescu, D. Empirical Study towards Corporate Social Responsibility Practices and Company Financial Performance. Evidence for Companies Listed on the Bucharest Stock Exchange. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, T.; Clelland, I.J. Talking trash: Legitimacy, impression management, and unsystematic risk in the context of the natural environment. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, R.R. Corporations, Democracy, and the Historian. Bus. Hist. Rev. 2019, 93, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnahedh, S.; Bhagat, S.; Obreja, I. Employment, Corporate Investment, and Cash-Flow Risk. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2019, 54, 1855–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuille, L.K. Corporations, property, personhood. Denver Law Rev. 2020, 97, 557–595. [Google Scholar]

- McWhorter, L. The Morality of Corporate Persons. South. J. Philos. 2017, 55, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]