Abstract

Information technology is recognized as an important means of expanding the sustainability of local festivals, but most research and practices only focus on existing information technologies such as websites and social network services. This study examines the potential of crowdfunding platforms to ensure the success of local festivals and assesses how emerging information technologies impact the sustainability of the tourism industry. This study proposed four values based on the value theory that is frequently applied in consumer research. We also applied inner innovativeness as a personal characteristic and examined the effects of economic, emotional, social, altruistic, and inner innovativeness regarding film festival crowdfunding on the intention to visit the film festival. We applied perceived risk and the intention to use electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) as mediating variables. As a result, emotional, social, and altruistic values were found to significantly affect the intention to visit film festivals by mediating perceived risk. In addition, the social value was found to have positive effects on the dependent variable through the intention to use e-WOM. The results show that crowdfunding platforms are considered an important tool for promoting the festival. It is also important to develop value in favor of the festival by increasing value through marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

The sustainability of local festivals is important because they provide benefits to the community. Communities can generate economic income by discovering unique local content [1], and festivals provide an opportunity to externally promote this content [2]. However, festivals held by small cities often face budgeting issues, so it is hard to be active in marketing. In this situation, advances in information technology (IT) may act as another opportunity to promote the sustainability of the local festival industry.

During the period in which the Internet became popular, local tourism websites were used as the main platform to provide travelers with up-to-date tourist information in the region [3]. Many travelers have recently been able to get or share information about local festivals through various IT platforms. Social network services (SNS), which emerged around 2010, are regarded as one of the megatrends influencing tourism systems [4]. These platforms not only allow travelers to search for information [5] but also help them make decisions about visiting tourist attractions or festivals [6]. SNS is also rated as having the ability for travelers to engage with potential customers by sharing comments, videos, photos, and more [4]. Tourists upload their local photos to SNS, and potential customers who view this content through SNS are attracted to the region. Given that potential tourists primarily rely on the opinions of others, such as word of mouth (WOM), for decision-making [7], SNS are the best method to encourage them to participate in local festivals. From the festival organizers’ point of view, SNS help to effectively promote local festivals [8].

The emerging crowdfunding platform is also a valuable tool to promote local festivals. Businesspeople have said that they use crowdfunding to market their projects or communicate with fans or supporters [9]. They can also increase their brand awareness through crowdfunding [10]. Many arts and cultural projects, for example, make heavy use of crowdfunding because in addition to attracting funds, they can also promote funding simultaneously [11]. A notable example is Big Issue Korea, which raised funds through crowdfunding for the Nutcracker, a play in which homeless people played a major role. The press recognized the crowdfunding by Big Issue Korea, which saw great results from the promotion [12].

Crowdfunding can be linked with SNS to maximize the promotion of local festivals [13]. Most crowdfunding sites provide the SNS information of individual operators and include the function to share crowdfunding information. Potential participants can use SNS information to determine various indicators of various crowdfunding, which can have a social impact on participants’ support decisions [14]. Individuals spread crowdfunding information to others, and those exposed to it can receive festival and crowdfunding information. Therefore, it is meaningful to consider the effects of electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) and crowdfunding factors on social network services.

While crowdfunding platforms are being assessed as a means of sustainability for local festivals, previous research has focused primarily on the effect of social network services [4,5]. However, these works omit the impact of associations between one or more online services and the intention to visit a tourist destination. Online marketing tools show an important diversity, and consumers are also able to receive tourism information through a range of various online channels. This indicates the importance of investigating the effects of multiple marketing tools simultaneously. Therefore, this study constitutes the framework of study considering not only (1) e-WOM, which is the main effect of social network services, but also (2) the role of a new medium—crowdfunding.

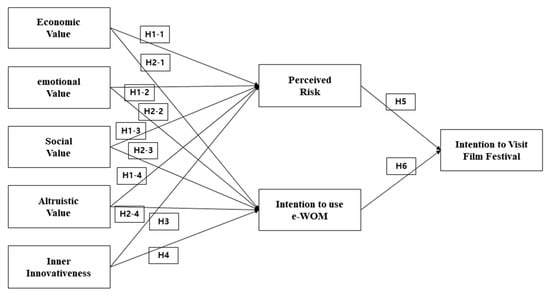

With regard to crowdfunding factors, this study examines the influence of perceived economical, emotional, social, and altruistic values about film festival crowdfunding on the intention to visit the region of film festivals. In addition, the perceived risk of film festival crowdfunding is applied as a mediating variable. Perceived risk is considered a useful variable in exploring the user’s perception of uncertainty in accepting new IT services. Therefore, it is a meaningful approach to look at the effects of perceived risks on film festival crowdfunding. Regarding the role of e-WOM, it applies the intention to use electronic word of mouth (e-WOM) as mediating variables. E-WOM was proven to be an effective way to promote tourist destinations at a low cost [15]. The intention to use e-WOM is thus a meaningful variable to examine the effects of crowdfunding as a tool for disseminating information about festivals. In addition, the framework includes inner innovativeness as one of the independent variables. This approach is to consider not only the marketing platform but also the personal characteristic as an explanatory variable.

This research model draws on the frameworks of several studies that examine factors influencing the intention to visit tourist destinations [16,17]. These studies assume that measures of online consumer behavior, such as e-WOM [16] and blog usage [17], mediate explanatory variables relating to the intention to visit tourist destinations. This study proposes an extended framework by applying the explanatory variables and some mediating variables suggested above considering the characteristics of the subject and factors. Thus, this framework examines tourists’ perceptions, intentions, and actions as a whole. Given the continuing increase in the impact of information technology services in the tourism industry, it will help to increase sustainability in regional tourism industries with unstable conditions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Local Festival and Crowdfunding

Local festivals provide tourists with a variety of events that utilize cultural elements within the city for a certain period of time. During the festival, the community can introduce the community’s local traditions, intangible heritage, natural scenery, and ethnic backgrounds to the tourists [18]. Thus, festivals are meaningful because the community can discover local cultural elements and use them as highly sustainable tourism resources. Local festivals also contribute to increasing the city’s demand for travel [19]. Tourists visit the festival area and pay a cost to use various amenities such as transportation, accommodation, and restaurants. Thus, local festivals are also recognized as a means of promoting the local tourism industry and activating the economy [20]. In addition, local festivals not only expose a city as a tourist destination but also influence the re-creation of a city’s image [21]. From a city marketing point of view, festivals are an effective approach to strengthening the identity of a city and reversing the negative image of a city [22]. In summary, local festivals are important tourist resources that generate economic benefits and enhance a city’s image.

In recent years, local film festivals have become popular as one of the exciting local events. Major cities around the world, such as Cannes, Venice, and Berlin, have held international film festivals for a long time. For example, Cannes, a local small town, established the world’s third film festival in 1939, following the Venice International Film Festival (1932) and Moscow International Film Festival (1935). Currently, hosting the most popular international film festival worldwide is the most powerful element defining the identity of Cannes [23]. The Cannes International Film Festival attracts approximately 200,000 tourists, including audiences and professionals, each year, generating 200 million euros’ worth of economic benefits [24].

The Cannes International Film Festival attracts audiences of all ages by offering movies and popular entertainment content. The general public can take an interest in international film festivals because movies from different countries can be seen in one place. Professional groups such as directors, actors, and students may visit the city to participate in special sessions or workshops at the festival [25]. Therefore, film festivals are not just entertaining events but also culturally valuable events that can be inspired by various academic topics, such as socio-cultural, aesthetic, geopolitical, and economic issues [26].

The success of film festivals is often related to proper promotion. Promotions, in particular, are an essential element in promoting the sustainability of start-up film festivals in the locale. Marketers at local festivals, including film festivals, are actively using IT as a promotional tool. Websites and SNS are representative IT platforms for festival promotion. Recently, they have also used crowdfunding platforms as a means of promoting festivals.

Crowdfunding can be classified into four types based on investment method: lending-based, equity-based, donation-based, and reward-based [27]. Equity-based is a way of investing in the idea of a startup, and lending-based is a way of investing in a project through a small loan. Donation-based means that investors will purely support the donation with no rewards. Finally, reward-based refers to offering products instead of financial rewards. Cultural and art events such as film festivals are mainly associated with reward-based crowdfunding. For instance, 154 and 32 crowdfunding projects on festivals were posted on Tumblbug [28] and Wadiz [29], respectively, which are Korea’s leading reward-based crowdfunding platforms. Although the main purpose of crowdfunding is to fund projects by recruiting small investments of many people through an online platform [30], crowdfunding also generates promotional benefits for tourism projects [31]. In particular, crowdfunding is also used as a marketing tool to implement word-of-mouth strategies on social media. Crowdfunding platforms offer the chance for participants to pitch an idea to their social network [32]. This means that crowdfunding and SNS are highly compatible.

2.2. Consumption Value of Crowdfunding

Consumption value is an estimate of the utility of the product that a consumer receives when compared to the price and effort paid [33,34]. This explains whether a consumer purchases a particular product or why the consumer chooses one product over other ones [35]. Consumption value is thus a key determinant of consumer shopping behavior and product choice [36]. Previous studies segmented specific factors of value based on the concept of consumption value. For example, Park, Jaworski, and Maclnnis (1986) proposed functional, symbolic, and experiential values based on the concept of consumer needs [37]. Sheth, Newman, and Gross (1991) confirmed functional, conditional, social, emotional, and epistemic values as factors that influence consumer behavior [35]. Sweeney and Soutar (2001) proposed a multiple-item scale that includes a price value to measure the cost value of a product as well as the quality, emotional, and social values suggested in previous studies [38].

However, Smith and Colgate (2007) argued that value factors fall into four broad categories: (1) functional/instrumental, (2) experiential/hedonic, (3) symbolic/expressive, and (4) cost/sacrifice values [39]. The functional/instrumental value is related to the usefulness of a product or service, or the extent to which they perform a required function, and it encompasses concepts of functional, practical, and useful value. The experiential/hedonic value refers to the level at which a product or service creates an emotional value for a consumer. This value became an emotional or sensory value in some studies. The symbolic/expressive value is related to the degree to which consumers give psychological meaning to a product and includes the meaning of intrinsic value or possession value. Finally, the cost/sacrifice value represents the level of economic costs that consumers perceive during purchasing activities and includes factors such as economic and psychological costs. The consumption value factors presented by Smith and Colgate (2007) have academic implications because they have proposed categories in consideration of many previous studies [39].

Perceived values have been applied to describe consumers’ behavior about various services and products. Some studies investigated the effect of consumption value on crowdfunding [40,41,42]. Schulz et al. (2015) proposed a hedonic value as a predictor of crowdfunding success, and it was confirmed that crowdfunding projects that show a high level of hedonic value are more successful than others [42]. Studies by Ho, Lin, and Lu (2014) and Moysidou and Spaeth (2016) introduced various consumption values as explanatory variables in the crowdfunding arena [40,41]. Moysidou and Spaeth (2016) categorized investor types into loan-based, equity-based, and presales-based projects based on crowdfunding investment methods and examined the factors that influence their willingness to support the project [41]. Financial, functional, informational, emotional, social, aesthetic, and novelty values were considered as independent variables. Consequently, financial and informational values were identified as factors affecting the willingness to support equity-based projects. Additionally, financial, emotional, and informational values were predictors for loan-based projects, and functional, emotional, and informational values were predictors in presales-based projects. In addition, Ho, Lin, and Lu (2014) also found that emotional, social, and function values have a positive effect on behavioral intentions for crowdfunding of cultural goods [40].

Previous studies commonly supported that the influence of financial, emotional, social, functional, and informational values presented by traditional value theories also influence behavioral intentions on crowdfunding. These values reflect the nature of crowdfunding as an investment platform but do not consider the characteristics of donation-based crowdfunding. Individuals are likely to participate in crowdfunding to satisfy their social approval desire rather than for monetary compensation in the reward or donation-based crowdfunding, where outputs are not monetary benefits [43]. As other-oriented factors, altruistic values are also important in the area of consumption [44].

Yet, another limitation of previous studies was that they did not consider the mediating effects between value factors and user behavior. Crowdfunding is an investment of personal money, so participants are likely to perceive financial risks. Generally, perceived risk is negatively correlated with a preference for financial instruments such as crowdfunding [45]. When crowdfunding includes high levels of value and credibility, participants perceive a low level of risk, which might positively affect behavior intentions [46]. In light of previous studies, this study applies economic, hedonic, social, and altruistic values as independent variables and assumes that these variables negatively affect perceived risk.

Hypothesis 1-1 (H1-1).

Economic value will negatively affect perceived risk.

Hypothesis 1-2 (H1-2).

Emotional value will negatively affect perceived risk.

Hypothesis 1-3 (H1-3).

Social values will negatively affect perceived risk.

Hypothesis 1-4 (H1-4).

Altruistic values will negatively affect perceived risk.

This study assumes that four values influence crowdfunding’s e-WOM. If consumers perceive that one service provides more value than another one, they will voluntarily recommend it to others. In general, the intention to use e-WOM is determined by how a consumer evaluates a service or product. Specifically, consumers will be more likely to use word of mouth when a supplier provides value satisfaction compared to other suppliers [47].

Previous studies reported that the perceived value of consumers positively affects intention to use WOM [48,49]. Anwar and Gulzar (2011) found that perceived food value affects WOM endorsements through the mediating effects of consumer satisfaction [49]. By contrast, Abdolvand and Norouzi (2012) and Hansen et al. (2008) reported that perceived values have a direct effect on WOM without mediating effects [48,50]. Furthermore, Hansen et al. (2008) argued that the WOM behavior originated from the intention to repay the benefits provided by suppliers [50]. The relationship between perceived value and WOM is also important in emerging markets such as crowdfunding services. Customers in emerging markets determine their WOM behavior by considering how much value they have gained [51]. Potential investors are unlikely to know how much value they can return in crowdfunding before the experiences. Furthermore, WOM is likely to affect potential consumers’ indirect experience of crowdfunding, and they might perceive the value. Although it is difficult to find a study that applies four types of value, the relationship between perceived values and e-WOM is supported by previous studies. Therefore, this study suggests that the perceived value of crowdfunding positively affects e-WOM.

Hypothesis 2-1 (H2-1).

Economic value will positively affect e-WOM.

Hypothesis 2-2 (H2-2).

Emotional value will positively affect e-WOM.

Hypothesis 2-3 (H2-3).

Social values will positively affect e-WOM.

Hypothesis 2-4 (H2-4).

Altruistic values will positively affect e-WOM.

2.3. Innovativeness

Inner innovativeness is defined as the degree to which an individual accepts a new idea or makes a decision about a new one [52]. The concept of inner innovativeness, based on innovation diffusion theory, adequately describes how to recognize new subjects and further adopts real targets according to the level of individual innovation [53,54]. Perceptions and behaviors regarding new technologies or services, such as crowdfunding, are likely to be determined by an individual’s personality [53]. Specifically, when having a high level of inner innovativeness, the individual is better able to receive new technologies [55]. These individual tendencies have been consistently observed in the areas of media technologies such as personal computers, online games, and mobile technology [54,55,56].

Prior to the 1990s, studies of new technologies and services were primarily focused on the individual’s perception of the subject instead of that individual’s personal characteristics. After that, several studies examined the effects of individual characteristics such as self-efficacy [57] and intrinsic involvement [58]. For instance, Chang et al. (2006) identified the impact of internal innovation among the personal characteristics supporting online game adoption and suggested that highly innovative game players are more likely to adopt game playing [54]. In addition, several studies suggested that innovativeness leads to adoption behaviors [55,59]. In summary, previous research has focused primarily on examining the relationship between inner innovativeness and adoption behaviors.

However, several perceptual factors are proposed as well as adoption intentions as outcomes of inner innovativeness. First, inner innovativeness is related to perceived risk factors. In general, individuals face risks due to uncertainties about outcome behavior regarding new products or services [60,61]. In this situation, highly innovative individuals are willing to accept the uncertainty [53]. These risk-taking behaviors are considered typical features of highly innovative individuals [62]. Previous studies proved the negative relationships between inner innovativeness and perceived risks [60,63]. In summary, individuals with high levels of innovation are less likely to perceive risks and, as a result, are more likely to act aggressively on new services or products. The link between inner innovativeness and perceived risk has also been found in areas of financial transactions such as crowdfunding. Users cannot be sure of the quality of their financial transactions and, as a result, experience uncertainty [60]. Highly innovative individuals perceive lower risks than those who do not, resulting in more financial transactions.

Another outcome of inner innovativeness is the intention to use e-WOM. Traditional opinion leader research suggests that the higher the individual’s inclination to innovate, the more likely they are to be opinion leaders [64]. Opinion leaders are considered active persons with a strong willingness to spread information about a particular object to others [65]. Given this, inner innovativeness can also have a positive effect on an individual’s e-WOM intentions. Yoo, Jin, and Sanders (2013) classified consumer innovativeness into social, functional, hedonic, and cognitive [66]. Of these, social and cognitive innovativeness were found to affect intentions to use e-WOM. Sun et al. (2006) proposes online opinion leadership and online opinion seeking as two components of the e-WOM [67]. Online opinion leadership was identified as an outcome of inner innovativeness. In particular, Sun et al. (2006) provided significant results, showing that the effects of inner innovativeness on e-WOM are also found online [67]. In the study of tourism and experience goods, direct relationships between inner innovativeness and intention to use e-WOM are hard to find. It has been suggested that personal characteristics could affect the intention to use e-WOM in tourism [68]. Because inner innovativeness is a personal characteristic whose relationship with intention to use e-WOM has been verified in marketing studies, it can be expected that inner innovativeness will affect the intention to use e-WOM in tourism.

From a marketing point of view, an e-WOM strategy via SNS is a powerful tool that can leverage a range of features, such as the hashtag, to expand the reach of potential customers [69]. Therefore, inner innovativeness seems to affect e-WOM on SNS more clearly.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Inner innovativeness will negatively affect perceived risk.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Inner innovativeness will positively affect intention to use e-WOM.

2.4. Perceived Risk

Perceived risk has been applied consistently in analyzing consumer behavior because it has a decisive effect on behavior. Perceived risk is defined as the degree of uncertainty about the outcome of a decision [70] and anxiety about the loss of expected value [71]. In particular, individuals are more likely to perceive risk in an online environment where uncertain information is relatively high. High risk perception means that consumers believe themselves more likely to suffer loss as a result of using a product or service. This potential is expected to diminish consumer intentions or behaviors to buy products or services, especially in the online context [72]. Perceived risk thus leads to a negative causal relationship between consumption intentions. Individuals experience risk in an online environment for a variety of reasons, including technical complexity [73], privacy exposure [74], and uncertainty in the non-face-to-face communication environment. Previous studies on online services adopted perceived risk as the main variable [75,76]. The online shopping study classified risk types into economic, social, functional, personal, and privacy risks [76], and the research on e-services suggested, overall, that financial, psychological, privacy, time, and performance risks are perceived risk types. [75]. In summary, it was found that the type of risk adopted depends on the type of service or product covered by each study, but most of the previous studies consistently applied at least economic risk.

Economic risk is defined as “the potential monetary outlay associated with the initial purchase price as well as the subsequent maintenance cost of the product” [77] (p. 146). Featherman and Pavlou (2003) argued that economic risk has the highest explanatory power over other risk types [75]. Economic risk is considered as an important factor in crowdfunding research [78,79]. Kim and Jeon (2017) checked how economic risk negatively affects the intention of participating in crowdfunding [78]. Zhao et al. (2017) also found that perceived economic risk has a negative correlation with backers’ funding intention in crowdfunding [79]. Therefore, if crowdfunding participants perceive that the project has high economic risks, they may be able to reconsider their next actions rather than actively investing or participating.

This study also considers perceived economic risk as a mediator. Although most festival crowdfunding is for donation-based or reward-based crowdfunding, this relates strictly to monetary spending. Thus, regardless of whether the rewards provided by crowdfunding managers are psychological or material, individuals can compare monetary expenditures and rewards. If the value of the perceived reward of a donation is lower than the monetary expenditure, perceived risk is likely to appear [71]. Thus, we consider that economic risk is a major variable because such risk is triggered by individual monetary spending.

Previous studies suggested that the intention to participate in crowdfunding was an outcome of perceived economic risks [46,78], but this study assumes that perceived economic risks for festival crowdfunding services negatively affect the intention to visit festivals. The crowdfunding platform is not only an investment platform but also an information resource for the festival. Individuals are more likely to visit film festivals based on the information. Particularly, considering that many festivals’ crowdfunding offers movie tickets as a reward, which must be used on-site, participants are likely to visit the area.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Perceived risk will negatively affect the intention to visit.

2.5. Intention to Use e-WOM

In the traditional sense, WOM is the interpersonal communication that occurs between the sender and the receiver, and it also describes the process of changing the recipient’s behavior or attitude [38]. Recently, many studies have examined the effect of e-WOM. E-WOM is defined as “all informal communications directed at consumers through Internet-based technology related to the usage or characteristics of particular goods and services” [79] (p. 461). As such, online services are considered the most effective means of interpersonal communication [80]. As IT advances and various communication platforms such as social networks increase, individuals can exchange information seamlessly with each other. The information produced on the major platforms for e-WOM influences individual planning and decision-making [81]. In fact, e-WOM was estimated to secure 30 times more customers than traditional channels [82].

Given some characteristics of tourism, travelers are more likely to be influenced by e-WOM. First, tourism is an experience good [83]. Individuals try to lower the uncertainty they perceive in decision-making by considering an indirect experience regarding tourism information. Second, tourism is characterized by the information-intensive industry [84]. Tourists might try to get reliable information from many of the communications generated through e-WOM. Given these characteristics, individuals use e-WOM as an easy way to find information about travel destinations [85].

Several studies examined how e-WOM influences attitudes and behaviors to visit tourist areas [15,17]. Wang (2015) found that the intention to use e-WOM positively affected tourist visits [17]. Previous studies argued that WOM behavior includes a positive attitude and loyalty to the target [17,44]. Abubakar et al. (2017) reported that e-WOM influences the intention to re-visit the medical tourism industry [86]. Previous studies have found that those who share a positive message on the elements of a tourist experience with others are more likely to be immersed in tourism information or to have a positive understanding of it. In this sharing process, positive images can be created that arouse intention to visit [16]. It can be expected that this mechanism will appear here as it has elsewhere. Additionally, it is inferred that people with a high level of e-WOM intention are more likely to show the actual behavior, like visiting a tourist destination. According to this view, the sharing of film festival crowdfunding information is based on positive royalties for the festival. We assume that intention to use e-WOM based on the loyalty toward festival crowdfunding affects the intention to visit.

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

E-WOM will positively affect the intention to visit.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure and Sample

This study collected survey data from February 7 to 11, 2020, by requesting data from Marcromill Embrain, an online survey company. Korean survey respondents included those who had visited an international film festival in Korea at least once. International film festivals included Busan International Film Festival, Jeonju International Film Festival, Bucheon International Fantastic Film Festival, Jecheon International Music and Film Festival, Ulju Mountain Film Festival, DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, PyeongChang International Peace Film Festival, Muju Film Festival, Animal Film Festival in Suncheonman, Jeju Film Festival, Seoul Independent Film Festival, and Seoul International Women’s Film Festival. Except for 15 samples that were unreliable responses, 447 samples were considered as sample data for the research.

To help understand film festival crowdfunding, participants reviewed the crowdfunding content uploaded to Tumblbug, which is a leading crowdfunding platform in Korea. Specifically, before responding to the questionnaire, participants read information about film festival crowdfunding, fundraising, and benefits from participating in the crowdfunding.

The quota sampling was conducted by considering the proportion of age and gender in the census population. As shown in Table 1, 221 (49.4%) of the survey respondents were male and 226 (50.6%) were female. Furthermore, 108 (24.2%) of the respondents were aged 20–29, followed by those aged 30–39 (112, 25.1%), 40–49 (115, 25.7%), and 50–59 (112, 25.1%). Most respondents, 314 participants (70.2%), had a university degree followed by those who had completed graduate school or higher (59, 13.2%), those who had a high school diploma or lower (36, 8.1%), and those who were university students (37, 8.3%). Regarding income, 23% of respondents had a monthly personal income between 2,000,000–2,999,999 Korean Won (approximately US $1688–US $2532), followed by 3,000,000–3,999,999 (18.1%), 4,000,000–4,999,999 (11.4%), and 5,000,000–5,999,999 (11.0%). Finally, 10.3% of respondents had a personal income of less than 1,000,000 won (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information for the sample. KRW: Korean Won.

3.2. Measurement and Analysis Method

The research model includes the following eight variables: (1) economic value; (2) emotional value; (3) social value; (4) altruistic value; (5) inner innovativeness; (6) perceived risk; (7) e-WOM; and (8) intention to visit film festival. We set four value factors and one personal characteristic factor as independent variables that affected perceived risk (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research model.

The economic value describes how far it is perceived that film festival crowdfunding can provide monetary value. The emotional value describes how far it is perceived that the film festival crowdfunding can lead to a positive emotional state. The social value describes how far one expects to be recognized by social contacts for participating in the film festival crowdfunding. Economic, emotional, and social value were revised based on the Sweeney and Soutar (2001) study on shopping value [38]. The altruistic value describes how far one believes that film festival crowdfunding participation will help others. To measure the altruistic value, we considered items from Holbrook’s (2006) study of the applicability of subjective personal introspection factors in consumption experience [87]. Inner innovativeness is “the degree to which an individual is receptive to new ideas and makes innovation decisions independently of the communicated experience of others” [52] (p. 236). Items of inner innovativeness were revised based on Chang, Lee, and Kim’s (2006) study, which examined factors that influence online game adoption [54]. In an e-service adoption study, Featherman and Pavlou (2003) proposed seven types of risks, such as performance, financial, time, psychological, social, privacy, and overall risks [75]. Among them, the items of financial risk by Featherman and Pavlou (2003) were used in the study [75]. Perceived risk describes how much one expects to lose in relation to money for participating in film festival crowdfunding. Online word-of-mouth behavior is divided into opinion giving, opinion passing, and opinion seeking [88]. In this study, opinion passing was considered as observed e-WOM. E-WOM describes the willingness to share festival crowdfunding information with others on SNS. We used items based on research from Sun et al. (2006), Chu and Choi (2012), and Lee and Lee (2013) [67,89,90]. Finally, intention to visit the film festival describes the willingness to visit a local film festival in the near future. To measure this, we used the items of Perugini and Bagozzi (2001), which were based on the theory of planned behavior [91]. All questions in this study consisted of a Likert five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). Three items were contained for each variable (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Items and scales used in questionnaire.

The general characteristics of the samples were identified using SPSS18 statistical software. In particular, frequency analysis and composite reliability were performed to verify the reliability of the measurement questions. Next, this study utilized the structural equation model (SEM). The statistical software Amos 20 was used to carry out the calculations. SEM enacts multi-equation system procedures, determining multiple indicators of concepts, continuous latent variables, errors in equations, errors of measurement, and continuous latent variables [92]. This is useful for the comprehensive examination of relationships among multiple variables, as needed in this study. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to check the latent variables and ensure the absence of measurement errors by CFA. Next, the relationship between the variables was examined through the structural model.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

In this study, we applied the coefficient of Cronbach’s α to verify the composite reliability between the measured items. In general, reliability is satisfied when Cronbach’s α is greater than 0.7 [93]. Each variable includes three observed variables, and all the items in the model met the reliability criteria (See Table 3). Convergent validity is desirable when the average variance extracted (AVE) is greater than 0.5 [94]. As a result of the verification, all values of AVE were found to meet the criteria. To verify the indicator reliability, this study applies the criterion that every loading must be greater than 0.4 [95]. Of all the loading values, two observed variables were above 0.6 (AV_2 = 0.621, II_3 = 0.610), but most of them were greater than 0.7. In addition, all observed variables were verified to be statistically significant (p = 0.00). Therefore, good indicator reliability was confirmed. Regarding discriminant validity, AVE must be greater than all constructs of the square root [94]. As shown in Table 4, it was found that AVE exceeds the square of the correlation.

Table 3.

Construct reliability and validity.

Table 4.

Test of discriminant validity.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

To verify the fit of the structural model, absolute fit index, parsimonious fit index, and incremental fit index were considered. Scholars applied different criteria to assess model fit [92], but many previous studies usually applied χ2/df, RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), AGFI (Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), TLI (Tucker Lewis Index), and NFI (Normed Fit Index) as criteria for the model fit. As a result of the model fit verification, all of the fitness indices (χ2/df = 2.578, RMSEA = 0.059, AGFI = 0.867, CFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.938, NFI = 0.919) signaled a good model fit (See the Table 5).

Table 5.

Model fit statistics.

The purpose of this study was to analyze the effects of value factors and inner innovativeness on the intention to visit film festivals through perceived risk and e-WOM. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 6. With regard to the value factor, all variables, except for EV (economic value), showed significant effects on perceived risk. EmV (emotional value) (B = −0.410, ρ < 0.044) had a negatively significant effect on PR (perceived risk). It was also confirmed that AV (altruistic value) (B = −0.306, ρ < 0.025) negatively affected PR. However, SV (social value) (B = 0.528, ρ < 0.000), unlike the hypothesis, positively affected PR. Therefore, H1-2 and H1-4 were supported. Regarding H2-1 to H2-4, SV (B = 0.278, ρ < 0.000) had statistically significant effects on e-WOM, but EV, HV, and AV had no effect on e-WOM. Thus, only H2-3 was supported and H2-1, H2-2, and H2-4 were not supported. Next, InI (inner innovativeness) did not affect both PR and e-WOM. Therefore, H3 and H4 were not supported. Regarding the effects of PR and e-WOM on the dependent variable, PR (B = −0.099, ρ < 0.005) negatively affected IVFF (intention to visit film festival). The influence of e-WOM (B = 0.521, ρ < 0.000) was positively significant on IVFF. Thus, H5 and H6 were supported.

Table 6.

Hypotheses test for structural models by the general maximum likelihood structural equation model (SEM).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study aims to empirically examine how the perceived value of crowdfunding and inner innovativeness affect the intention to visit the film festival. For this, perceived risk and e-WOM were applied as mediating variables. Structural equation modeling was applied, and data were collected through an online survey. As a result, 6 of 12 research hypotheses were supported. Accordingly, we confirmed through its effects that crowdfunding is an important platform for promoting sustainability at local film festivals.

First of all, emotional values (H1-2) and altruistic values (H1-4) negatively affected perceived risk. This supports the findings of previous studies, which indicate that individuals perceive low levels of risk when they have a sense of worth regarding a given service or product [46]. These variables are commonly considered to be related to emotional characteristics rather than to cognitive ones. These results indicate that consumers are more likely to obtain emotional value as a result of the crowdfunding of cultural products, such as festival crowdfunding. Another notable aspect is that the path coefficient for emotional value (B = −0.401) was higher than the altruistic value (B = −0.306). This implies that emotional value has greater explanatory power. Future studies should develop this framework by developing detailed factors for emotional value. Interestingly, economic value effects were not confirmed. It is expected that the effects of economic value vary in relation to the type of crowdfunding. Moysidou and Spaeth’s (2016) study, which examined the impact of economic value on behavioral intention by project type, found an influence of economic value in revenue-based crowdfunding, such as equity-based and loan-based projects [41]. Individuals may not take economic value into account for donation-based or reward-based crowdfunding, including cultural goods. Economic relates to the amount of monetary benefit that an individual can receive. Individuals do not generally seek financial benefits when they participate in donation and reward-based crowdfunding. Rather, they seek to meet non-monetary needs, such as social approval or self-realization [43]. In particular, individuals’ non-monetary motivations are likely to be more prominent in cultural goods, such as in relation to local film festival crowdfunding, which mainly has non-commercial purposes.

For hypotheses 2-1 to 2-4, only social values (H2-3) positively affected the intention to use e-WOM. Social values and intention to use e-WOM both rest on the concept of social relationships. This result means that perception of the value of interacting with others through participation in festival crowdfunding can affect social interactions online. Prior studies have found that perception of quality in the general product area, such as food, can affect WOM [49]. On the other hand, social value effects were identified in this study. It is unclear whether these results can be attributed to the nature of the experience or to crowdfunding type. Further research is needed.

Next, inner innovativeness was found not to affect perceived risk and e-WOM intentions. These results indicate that the consumer’s inner innovativeness is not related to the perception of festival crowdfunding. Regarding perceived risks, Foxall (1988) proposed that risk perceptions vary according to the type of users [96]. This means that early adopters underestimate the risk compared to late adopters. Accordingly, future studies should identify the audience characteristics for film festival crowdfunding and examine the relationship between inner innovativeness and perceived risk for each type. Regarding e-WOM, previous studies on innovation have shown a different view of claims. For example, Summers (1970) argued that highly innovative people tend to give opinions to people [64], but Rogers (1995) argued that innovation is related to information seeking [53]. The two studies each focused on the production and acceptance of information. By contrast, Sun et al. (2006) verified that innovativeness has a significant impact on both online information leadership, which includes the concept of e-WOM, and information seeking [67]. Given the inconsistent claims of the previous studies, further research should examine the relationship between innovativeness and e-WOM.

Third, perceived risk negatively affects the intention to visit the film festival (H5). This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies, which indicated that perceived risk for crowdfunding affects actual behavior [46,78]. This also means that, if an individual underestimates the risk of festival crowdfunding, they can visit the festival. Last, the intention to use e-WOM also had a positive effect on the intention to visit the film festival (H6). This result is consistent with previous studies that have suggested that e-WOM has a positive effect on travel intention [15,17]. The action to share the usefulness of festival crowdfunding with friends is believed to be based on trust or interest in the film festival. This means that positive perceptions of the film festival can lead to real action, such as visiting a festival. However, there is also the possibility that control variables may have some bearing on the intention to use e-WOM and the intention to visit a film festival. For example, actual behavior may vary depending on perceived involvement in film festivals or crowdfunding platforms. Future research will be needed to expand the research model by exploring moderating variables.

As for H5 and H6, earlier study of tourism crowdfunding used crowdfunding behavior as a dependent variable. Our study, however, set the intention to visit a festival as an outcome variable and not a crowdfunding behavior, and found that it is affected by explanatory variables. This means that the effects on the service platform can affect consumers’ behavior in relation to the topic of crowdfunding beyond the platform. If individuals have a positive perception of crowdfunding services, this may indirectly indicate that they have a positive perception of crowdfunding as well as of the service platform. Therefore, crowdfunding goes beyond investment to acting as a marketing tool, attracting individual visits to local film festivals and further enhancing the sustainability of local film festivals.

This study has theoretical implications. First, previous work has examined factors affecting the intention to participate in festival crowdfunding [97,98], but overall, too little work has been done on the effects of crowdfunding in tourism. Additionally, from a marketing perspective, few analyses or in-depth discussions of festival crowdfunding have been done. This study is thus an important examination of the influence of tourism crowdfunding. Second, this study proposed a framework to examine the marketing effects of crowdfunding in tourism. It has been confirmed that the influence of certain variables varies depending on the type of crowdfunding being considered. As noted, we found that emotional factors should be taken seriously in the study of donation-based and reward-based crowdfunding. If this framework is properly modified in response to the results of this study, festival-visiting behavior can be explained in greater detail. Third, to supplement existing research trends, structural modeling is proposed in relation to perceived risk and e-WOM as mediating variables between value factors and behavioral intentions. This approach can provide a useful aid to studies dealing with online communication environments and platforms with high uncertainty, such as crowdfunding platforms.

This study provides practical guidelines to help with festival sustainability. First, this study confirmed that the crowdfunding platform can be used as a marketing tool. It was found that factors related to crowdfunding platforms, such as perceived risk and e-WOM, drive intentions to visit the festival. Therefore, even if the film festival does not need financial help, marketers should open a crowdfunding page to provide an opportunity to access the film festival crowdfunding and obtain information. Second, marketers should build their value strategy differently depending on the type of crowdfunding. Marketers encourage consumers to perceive economic value for equity-based and loan-based crowdfunding, whereas, for non-revenue types such as donation-based or reward-based, marketers should provide an opportunity to gain emotional value or the need for approval. Finally, marketers can understand consumers’ e-WOM behavior and strategically use it. Crowdfunding, for example, is compatible with SNS. Moreover, users can share information about crowdfunding via SNS. Therefore, this study is expected to provide a guide for developing and implementing a marketing strategy that simultaneously utilizes SNS and crowdfunding platforms to enhance the e-WOM effect on film festivals.

Regarding limitations, in this study, film festival crowdfunding is still an emerging market, so it was difficult to conduct online surveys for actual users. Respondents to this study experienced indirect festival crowdfunding only through the experimental treatment provided by the researcher. Future researches may conduct online surveys in collaboration with film festival crowdfunding providers, who can directly contact actual users. Next, follow-up studies should take a closer look at the effects of other factors on the intention to visit a film festival. Potential consumers will recognize not only the risks directly related to the festival but also the risks of the crowdfunding investment in their decision to visit the festival. Thus, in addition to the perceived risk of participation in film festival crowdfunding, risks associated with the consumption behaviors that are seen during participation in the festival should also be considered. Finally, future studies should be conducted that investigate multi-dimensional inner innovativeness. Certain studies have also reviewed how well individuals accept brands or images related to innovation [54], but these have mainly involved emotional indicators, so to examine the effects of inner innovativeness, both cognitive and emotional perspectives should be considered.

Author Contributions

H.K. and B.C. conceived and designed the experiments; B.C. performed the experiments; H.K. analyzed the data; B.C. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools; H.K. and B.C. wrote the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Global Research Network program through the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2017S1A2A2041908).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yoo, C.; Kwon, S.; Na, H.; Chang, B. Factors affecting the adoption of gamified smart tourism applications: An integrative approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.; Kociatkiewicz, J. City festivals: Creativity and control in staged urban experiences. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2011, 18, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirne, E.; Curry, P. The impact of the Internet on the information search process and tourism decision making. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 1999; pp. 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, D.; Law, R.; Van Hoof, H.; Buhalis, D. Social media in tourism and hospitality: A literature review. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Basu, C.; Hsu, M.K. Exploring motivations of travel knowledge sharing on social network sites: An empirical investigation of U.S. college students. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotis, J. Discussion of the Impacts of Social Media in Leisure Tourism: The Impact of Social Media on Consumer Behaviour: Focus on Leisure Travel. Available online: http://johnfotis.blogspot.com.au/p/projects.html (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Peterson, R.A.; Balasubramanian, S.; Bronnenberg, B.J. Exploring the implications of the Internet for consumer marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoksbergen, E.; Insch, A. Facebook as a platform for co-creating music festival experiences: The case of New Zealand’s Rhythm and Vines New Year’s Eve festival. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollick, E.R.; Kuppuswamy, V. After the campaign: Outcomes of crowdfunding. UNC Kenan-Flagler Res. Pap. 2014, 2376997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, C.; Teigland, R. Crowdfunding among IT entrepreneurs in Sweden: A qualitative study of the funding ecosystem and ICT entrepreneurs’ adoption of crowdfunding. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2289134 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Jeon, S.H. Crowd-funding between the movie content production through the analysis of the relationship or the successful funding case research. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2013, 13, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kim, D.H. The study on an invigoration of crowding fund - based on legal support system & related case research. Int. Bus. Rev. 2014, 18, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.Y.; Hwang, S.G. The Case and Analysis of the Viral Marketing Effect of Crowdfunding -Focused on the Design Brand Start-up. Treatise Plast. Media 2018, 21, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Moisseyey, A. Effect of Social Media on Crowdfunding Project Results. Master’s Thesis, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NE, USA, May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Prayogo, R.R.; Kusumawardhani, A. Examining Relationships of Destination Image, Service Quality, e-WOM, and Revisit Intention to Sabang Island, Indonesia. Asia-Pac. Manag. Bus. Appl. 2017, 5, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Shang, R.A.; Li, M.J. The effects of perceived relevance of travel blogs’ content on the behavioral intention to visit a tourist destination. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. Exploring the influence of electronic word-of-mouth on tourists’ visit intention. J. Syst. Inf. Technol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Mei, W.S.; Tse, T.S. Are short duration cultural festivals tourist attractions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Jenner, P. The impact of festivals and special events on tourism. Travel Tour. Anal. 1998, 4, 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, D.; Fleischer, A. Local festivals and tourism promotion: The role of public assistance and visitor expenditure. J. Travel Res. 2003, 41, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Haider, D.; Rein, I. Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry and Tourism to Cities, States and Nations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, C. The effects of festivals and special events on city image design. Front. Archit. Civ. Eng. China 2007, 1, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, C.S.; Pedersen, J.S. City branding and film festivals: Re-evaluating stakeholder’s relations. Place Branding Public Dipl. 2010, 6, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palais Des Festivals. Available online: https://www.palaisdesfestivals.com/uploads/brochures/Press-Pack-Cannes-Tourism-2018.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Báez, A.; Devesa, M. Segmenting and profiling attendees of a film festival. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udden, J. Film festivals. J. Chin. Cine. 2016, 10, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burtch, G.; Ghose, A.; Wattal, S. An Empirical Examination of the Antecedents and Consequences of Contribution Patterns in Crowd-Funded Markets. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumblbug. Available online: https://tumblbug.com/ (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Wadiz. Available online: https://www.wadiz.kr/web/wcampaign/search?keyword=festival (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Borst, I.; Moser, C.; Ferguson, J. From friendfunding to crowdfunding: Relevance of relationships, social media, and platform activities to crowdfunding performance. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 1396–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temelkov, Z.; Gulev, G. Role of crowdfunding platforms in rural tourism development. Sociobrains Int. Sci. Refereed Online J. Impact Factor 2019, 56, 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, E.M.; Hui, J. Crowdfunding: Motivations and deterrents for participation. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 2013, 20, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Drew, J.H. A multistage model of customers’ assessments of service quality and value. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D.; Herrmann, A.; Huber, F. The evolution of loyalty intentions. J. Mark. 2016, 70, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why We Buy What We Buy: A Theory of Consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; Jaworski, B.J.; Maclnnis, D.J. Strategic brand concept-image management. J. Mark. 1986, 50, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.B.; Colgate, M. Customer value creation: A practical framework. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2007, 15, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.Y.; Lin, P.C.; Lu, M.H. Effects of online crowdfunding on consumers’ perceived value and purchase intention. Anthropologist 2014, 17, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysidou, K.; Spaeth, S. Cognition, emotion and perceived values in crowdfunding decision making. In Proceedings of the Open and User Innovation Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 1 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, M.; Haas, P.; Schulthess, K.; Blohm, I.; Leimeister, J.M. Available online: https://www.alexandria.unisg.ch/241339/1/JML_513.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Kraus, S.; Richter, C.; Brem, A.; Cheng, C.F.; Chang, M.L. Strategies for reward-based crowdfunding campaigns. J. Innov. Knowl. 2016, 1, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, R.; Hammond, K.; Lomax, W. Measuring the impact of positive and negative word of mouth on brand purchase probability. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2008, 25, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, K. How do Consumers Evaluate Risk in Financial Products? J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2005, 10, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, C.D.; Wang, J.L.; Chen, P.C. Determinants of backers’ funding intention in crowdfunding: Social exchange theory and regulatory focus. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, A.S.; Basu, K. Customer loyalty: Towards an integrated conceptual framework. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1994, 22, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolvand, M.A.; Norouzi, A. The effect of customer perceived value on word of mouth and loyalty in B-2-B marketing. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2012, 4, 4973–4978. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, S.; Gulzar, A. Impact of perceived value on word of mouth endorsement and customer satisfaction: Mediating role of repurchase intentions. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2011, 1, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, H.; Samuelsen, B.M.; Silseth, P.R. Customer perceived value in BtB service relationships: Investigating the importance of corporate reputation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 206–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, D.; Simmers, C.S.; Licata, J. Customer self-efficacy and response to service. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 8, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, D.F.; Dowling, R.G. Innovativeness-concept and its measurement. J. Consum. Res. 1978, 4, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, B.H.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, B.S. Exploring factors affecting the adoption and continuance of online games among college students in South Korea: Integrating uses and gratification and diffusion of innovation approaches. New Media Soc. 2006, 8, 295–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yao, J.E.; Yu, C.S. Personal innovativeness, social influences and adoption of wireless Internet services via mobile technology. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2005, 14, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.A. Exploring personal computer adoption dynamics. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 1998, 42, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compeau, D.; Higgins, C.A.; Huff, S. Social cognitive theory and individual reactions to computing technology: A longitudinal study. Mis Q. 1999, 23, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C.M.; Chow, S.; Leitch, R.A. Toward an understanding of the behavioral intention to use an information system. Decis. Sci. 1997, 28, 357–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D. What do people with digital multimedia broadcasting. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2008, 6, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldás-Manzano, J.; Lassala-Navarré, C.; Ruiz-Mafé, C.; Sanz-Blas, S. The role of consumer innovativeness and perceived risk in online banking usage. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.W.; Harris, G. The importance of consumers perceived risk in retail strategy. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 821–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, C.; Sivakumar, K. National culture and new product development: An integrative review. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastlick, M.; Lotz, S. Profiling potential adopters and non-adopters of an interactive electronic shopping medium. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 1999, 27, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.O. The identity of women’s clothing fashion opinion leaders. J. Mark. Res. 1970, 7, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J.; Davis, J.M.; Monsees, D.M. Opinion leadership in family planning. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1974, 15, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, C.W.; Jin, S.; Sanders, G.L. Exploring the role of referral efficacy in the relationship between consumer innovativeness and intention to generate word of mouth. Agribus. Inf. Manag. 2013, 5, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Youn, S.; Wu, G.; Kuntaraporn, M. Online word-of-mouth (or mouse): An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2006, 11, 1104–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Nam, J.H. Influences of Personality of Information Seekers on Instrumentality of Word of Mouth Communication: Focused on University Students. Int. J. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2012, 26, 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Chae, H.; Ko, E. The power of e-WOM using the hashtag: Focusing on SNS advertising of SPA brands. Int. J. Advert. 2018, 37, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R.A. Consumer Behavior as Risk Taking; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960; pp. 384–398. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby, J.; Kaplan, L.B. The components of perceived risk. ACR Special Volumes 1972. Available online: https://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/12016/volumes/sv02/SV02 (accessed on 1 March 2020).

- Gemar, G.; Soler, I.P.; Melendez, L. Analysis of the intent to purchase travel on the web. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2019, 15, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, S.H.; Shanklin, W.L. Seeking mass market acceptance for high-technology consumer products. J. Consum. Mark. 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Todd, P.A. Consumer reactions to electronic shopping on the World Wide Web. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 1996, 1, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherman, M.S.; Pavlou, P.A. Predicting e-services adoption: A perceived risk facets perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2003, 59, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvenpaa, S.L.; Trictinsky, N.; Vitale, M. Consumer Trust in Intention Store. Inf. Technol. Manag. 1999, 1, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Gotlieb, J.; Marmorstein, H. The moderating effects of message framing and source credibility on the price-perceived risk relationship. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.D.; Jeon, I.H. Influencing Factors on the Acceptance for Crowd Funding—Focusing on Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. J. Korean Inst. Intell. Syst. 2017, 27, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; McCleary, K.W. Factors Influencing Destination: A Perspective of Foreign Tourist. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 868–897. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, S.; Thal, K. The Impact of Social Media on the Consumer Decision Process: Implications for Tourism Marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusov, M.; Bucklin, R.E.; Pauwels, K. Effects of word-of-mouth versus traditional marketing: Findings from an internet social networking site. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.K.; Chen, T.H. The usage of online tourist information sources in tourist information search, an exploratory study. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbauer, A.; Werthner, H. Consumer behaviour in e-tourism. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2007; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2007; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ladhari, R.; Michaud, M. eWOM effects on hotel booking intentions, attitudes, trust, and website perceptions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Ilkan, M.; Al-Tal, R.M.; Eluwole, K.K. eWOM, revisit intention, destination trust and gender. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, M.B. Consumption experience, customer value, and subjective personal introspection: An illustrative photographic essay. J. Bus. Res. 2006, 59, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, S.S.; Lee, J.K. What drives consumers to pass along marketer-generated eWOM in social network games? social and game factors in play. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 8, 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S.C.; Kim, Y. Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.N.; Lee, K.Y. Determinants of eWOM behavior of SNS users with emphasis on personal characteristics, SNS traits, interpersonal influence, social capital. Korean J. Advert. Public Relat. 2013, 15, 273–315. [Google Scholar]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K.A. A new incremental fit index for general structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 1989, 17, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxall, G.R. Marketing new technology: Markets, hierarchies, and user-initiated innovation. Manag. Decis. Econ. 1988, 9, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Bonn, M.; Lee, C.K. The effects of motivation, deterrents, trust, and risk on tourism crowdfunding behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Law, R. Determinants of tourism crowdfunding performance: An empirical study. Tour. Anal. 2017, 22, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).