Abstract

In recent years, cities such as Venice, Dubrovnik, Paris and Barcelona have experienced an exponential increase in visitor numbers leading to episodes of tourismphobia by anti-tourism movements, or even the decline of the destination. Among other solutions, some destinations see film-induced tourism as a possible way of diversifying tourism supply and demand. Through the analysis of the locations of six thematic film routes in Barcelona compared to the same locations on the largest online travel review platform, TripAdvisor, it is concluded that, far from spreading out tourist flows, fiction-induced tourism in Barcelona has concentrated tourism at the main attractions of the city. Only a few exceptions of films with minor audiences lead tourists off the beaten track. Overall, this paper provides a set of recommendations, strategies and challenges for destination managers to help alleviate overtourism and to offer more sustainable tourism away from spots that attract mass tourism.

1. Introduction

Since the 1960s, several authors have talked about overtourism; in summary, this refers to a larger number of arrivals than a destination can accommodate, resulting in overcrowded destinations and in a negative perception of tourism by the tourists themselves and by the local population [1,2]. It is a multidimensional and transversal phenomenon that is difficult to solve since it is related to social, economic and political issues, among others. Some of the main causes are the negative behaviour of tourists while at the destination, the overuse of public and private spaces (e.g., public transport, shopping centres or restaurants), the overuse of natural resources, and the irruption of low-cost tourism (e.g., transportation and sharing economy) [3]. Venice represents the most paradigmatic example of an overcrowded city where the negative impact of tourism is more than evident [4].

Thus, it is argued that certain types of cultural tourism, such as film-induced tourism, could contribute to the sustainable development of the destination and help alleviate overtourism [5]. Some studies [6,7,8] emphasize the positive role that film-induced tourism can have in diversifying tourist products and flows, as well as in representing and revitalizing unknown parts of a destination. With these and other positive impacts in mind, many cities have started to invest in attracting film shoots, which could later generate film-induced tourism. However, in [9], the author questions the real viability of film tourism for sustainable tourist destination planning and development and its real contribution to alleviating overtourism, because sustainable tourism development should involve all stakeholders including the film industry, which is usually not overly concerned with the consequences the film may have on the destination.

Research on film-induced tourism faces several challenges, including shedding light on the agents, practices, destinations or attractions that films decide to portray and identifying recurring patterns and stereotypes in this respect [10]. Besides this, research should analyse these patterns cinematographically and understand why certain tourist places or practices are portrayed in these films and how this affects tourist destinations.

With these challenges in mind, this study is set in Barcelona—a city that, in recent years, has experienced episodes of tourismphobia or anti-tourism, the “active behaviour of rejection of tourists” [11] (p. 583), because of an excess of tourists in certain parts of the city, which has led to clashes with residents who suffer the adverse effects of this phenomenon.

Similarly to many other cities, Barcelona has started to portray itself through the cinema. The most important action in this line in terms of finance and promotional activities was the film Vicky Cristina Barcelona, directed by Woody Allen [12], with significant investment by Catalan public entities in the film who had a special interest in promoting the city of Barcelona internationally [13]. Therefore, the aim of this study is to analyse the contribution of audio-visual fiction to tourism sustainability in Barcelona from the point of view of the offer—more specifically, whether the movie routes promoted by the Destination Management Organization (DMO) Turisme de Barcelona has allowed the diversification of the places of interest for tourists in a city characterized by visitor saturation, by comparing the number of Online Travel Reviews (OTRs) of the same city attractions on the world’s largest online travel community platform, TripAdvisor.

TripAdvisor allows users to get information about tourist attractions (also about accommodation establishments, restaurants, or airline companies) and, as well as providing textual and numerical information of the OTRs given by others, allows users to find out the total number of OTRs that provide information on their popularity [14], as more reviews implies more visitors.

Thus, this study analyses “film-induced tourism on location—that is, at the places where particular scenes or elements of movies are filmed” [5] (p. 43), specifically the locations of the six thematic routes belonging to the package named “Barcelona Movie Walks” offered by the Destination Management Organization (DMO) of Barcelona and promoted online on its website.

The movie routes are based on the following films: Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), Salvador (2006), Todo sobre mi madre (in English, All about my mother, 1999), Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006), L’auberge espagnol (in English, Pot Luck, 2002), and Manuale d’amore (in English, Manual of Love, 2005) and their 65 locations of the film sets in Barcelona. All these locations are compared with the same ones displayed on TripAdvisor in order to determine the popularity of these sets according to the number of reviews.

Following this introduction, a literature review of film-induced tourism and its consequences for destinations is developed, and the methodology is presented together with the description of data collection from TripAdvisor. Later, the results of this research lead to the discussion and conclusions, with special emphasis on the theoretical contributions and practical implications for the destination.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Film-Induced Tourism

Since the 1990s, research on tourism induced by audio-visual fiction has demonstrated the relationship between the presence of certain places in films and television series and the increase in the number of visitors to them after screening [15,16,17]. Hence, the academic literature has focused on such varied aspects as its role in the construction of the destination image [7,18,19,20,21,22] and the motivations for the visit [18,23,24,25,26], the impact of film tourism on local economies [27,28,29,30], the experiences of film tourists [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] and their use from the point of view of marketing the destination [7,15,42,43,44,45], among others.

Tourists, from destination images, behave and make travel decisions based on multiple information sources [46]. Among these sources, films are considered autonomous agents—part of popular culture—which may be highly influential and credible for potential tourists as they are seen as unbiased compared to traditional advertising [47]. In addition to this powerful effect, autonomous sources have the particularity that destinations have no control over them, and they can provide substantial information about a destination in a very short period of time, thus changing the destination image rapidly [18]. In this respect, films contribute to the creation and reproduction of the tourist gaze [48], which anticipates the destination and the travel experience, and create social patterns with a greater sensitivity to certain visual elements of the landscape or townscape.

The peculiarities of audio–visual fiction and its reception, subject to the processes of identification and involvement of audio–visual narration and the transfer of connoted senses from the fiction space to reality, provide numerous attractions for the places in which their stories are set or where they have been filmed. In this sense, tourists live a vicarious experience when watching movie images, which makes them identify and empathize with the characters and actively participate in the world of the film [18]. All this depends on the degree of exposure of the place in the story and on the interrelation with the story and the characters that star in it—many of them, also, are played by celebrities with a high prescriptive power [15,16,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Movies and television series have the ability to turn places that did not attract visitors prior to their production into tourist destinations [25,44], as has proved to be the case for the cities Natchitoches (Louisiana, USA) (Steel Magnolias, Herbert Ross, 1989) [15], Sheffield, England (The Full Monty, Peter Cattaneo, 1997) [57], the town of Wang in the Chinese province of Hunan (Fu rong zhen [Hibiscus Town], Xie Jin, 1986) [52], and even Kazakhstan (Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, Larry Charles, 2006) [30].

This presents opportunities and challenges for tourism marketing organizations, film offices and production companies, which require the coordination of their work, as pointed out in [43,58,59]. Tourism marketing organizations can resort to audio–visual fiction to diversify tourist destinations and avoid tourist oversaturation, having recourse to the advertising strategy of the location of places, which is much less aggressive than conventional promotional campaigns. Film offices and production companies can develop destination marketing strategies that allow the impact that audio–visual fiction has on the image, the motivations and the decisions to visit the places where their stories are set to be made profitable.

Hudson and Ritchie [43] divide these initiatives into pre and post-premieres. The former seek to go beyond the specific benefits of filming in an area to contemplate its impact on tourism in the medium/long term. It entails reorienting tax incentives or any other type of financial benefit depending on the foreseeable image that may be generated by the film location or the diegesis, or even the potential number of visitors, taking into account, for example, whether it can contribute to the seasonality or diversification of tourism. These authors also consider all relevant advertising initiatives—including publicity—that contribute to linking filming and the territory, as well as the dissemination of the activities of the film’s artistic team during filming, especially if it involves celebrities. Marketing initiatives after the premiere, as the authors indicate, seek to transform the audience’s interest into future visits. These include audio-visual pieces about the filming of the films or the recording of the series (“making of”), guided tours and movie maps, which are fundamental to further linking of the filming or the space in which the events of the diegesis happen to the destination—or the space that can become a destination—especially if they are not referential or, if referential, are difficult to identify by certain audiences.

2.2. Overtourism

Carrying capacity is the precursor to current concerns with overtourism, and it is not a new concept [60]. Overtourism is a complex, multicausal phenomenon that is transforming tourism and tourism policies in urban environments [2]. Lopez Palomeque [61] has already pointed out that, in Barcelona, this phenomenon would justify moving from sectoral promotion policies towards a structural and transversal approach. Garcia Hernandez et al. [2] summarised the pressure indicators, the impacts and the response measures and found that when there is a significant impact of overload, the tourist experience is affected (negatively) and this is reflected in social media reviews [62], such as TripAdvisor. A possible measure to deal with overtourism is to apply smart solutions [2] or reposition the destination as a place of special tourism interest by focusing on a particular type of experience [63].

Some destinations see film-induced tourism as a possible intelligent way of helping alleviate overtourism and diversifying tourism supply and demand. Positive impacts of film-induced tourism in terms of alleviating overtourism in destinations involve the creation of film-themed tours and the diversification of the customer base [7], which can help to diversify the tourism product and raise awareness regarding certain unknown places and attractions. Film tourism can contribute to spreading new tourist trends and practices that match the destination’s needs [8] and contribute to solving the problem of overtourism [5]. For example, in big cities such as London, New York or Paris that attract large numbers of tourists, the tourist agencies visitlondon.com, nycgo.com and parisinfo.com see film tourism as a means of diversification and as a qualitative improvement of the city’s cultural offer directed mostly at tourists who would visit the city in any case [64], which could redirect tourist flows from the most saturated areas and even encourage them to wander off the beaten track (e.g., “The Montmartre of Amélie Poulain” route on parisinfo.com) and explore less-known spots. In Australia, the film Broken Hill in Outback Australia was an important asset for attracting interest and tourist flows to the Outback region in Australia—an unknown region of the destination [65] compared to other coastal and urban tourist areas. However, film tourism can also lead to natural and cultural environmental pressure both by the film industry and by the increase in tourist numbers at the destinations or at certain specific attractions [9], which could contribute to increased overtourism. Moreover, this author also highlights that impacts on tourism numbers can be short-term and of an immense volume. Previous studies [66] have found that, in Spain, film tourism has mainly been used to generate economic benefits and to attract tourists with greater purchasing power.

To ensure that film tourism really contributes to sustainable destination development, close cooperation between DMOs and the film industry is required as well as the participation of the local community, although this is not usually the case [9]. Some destinations have started making efforts in this area, such as that of the DMO in Japan, in collaboration with the Japan World’s Tourism Film Festival, to seek films which promote sustainable tourism, based on scientific data and future destination image plans [8]. Films, as relatively credible autonomous sources of information, contribute to creating an image of the destination and certain tourist expectations [67]. This author asserts that there is a need to plan an effective destination image strategy to achieve the most sustainable positive impacts from films. This strategy, which could contribute to alleviating overtourism, depends on the investment in aligning the films’ image of the destination with the desired image and the potential audience reach. The author explains that this film image strategy must be constantly monitored by the DMO to achieve the desired sustainable outcomes.

Currently, a destination image is increasingly formed, shared and monitored online, and online travel reviews especially have mushroomed in number and represent a rich, unsolicited and unbiased source of information to study the destination image and tourists’ opinions and experiences [68]. Thus, online travel reviews could be useful tools to assess destination image strategies in relation to film-induced tourism as well as the creation of new tourist products, trends and experiences linked with films, and ultimately give insights into how film-induced tourism contributes to the overtourism phenomenon.

Besides, word of mouth (WoM), and more specifically electronic word of mouth (eWoM), as information sources, is considered to be more effective than information provided by a destination itself or traditional information sources (i.e., travel agencies or tour operators) [68,69]. Thus, social media generates a rapid expansion of WoM [70], and this information, regardless of whether it is positive or negative, influences tourist behaviour when making travel decisions [71]. Thus, there is an exponential increase of information flow, which may be uncontrolled (a line of communication beyond the DMO’s control), and therefore generate a destination which begins dying from success [11].

In recent years, Barcelona has received strong criticism regarding the impacts of tourism on the living conditions of its inhabitants because of gentrification, environmental and acoustic contamination and the occupation of public space, among other externalities [72]. In this respect, the Barcelona DMO sees film tourism as a way to decentralize tourism by giving value to other spaces of the city [64]. Wray and Croy [65] argue that, to contribute to the sustainable development of the destination, the film product must be coordinated with other destination strengths. In a city such as Barcelona, with many top international attractions, similar to the case of London, Paris, or New York, very few tourists will visit it exclusively because of a specific film, but film routes can be an attractive product that complements visits to some of its main sites, helps to extend the tourists’ length of stay and spread out the tourists’ visits in space and time, encouraging them to explore less-visited spots. In the same line, Macionis and O’Connor [73] argue that DMOs should implement sustainable marketing management with the stakeholders involved; that is, DMOs have the responsibility to provide sustainable forms of tourism. These authors also argue that an interest in films could be used to make potential tourists aware of the range of experiences available at the destination by ensuring satisfying visitor experiences and integrating them into all other activities that take place at the destination.

2.3. User-Generated Content

The Internet has changed the methods of travelling at all stages of a trip [74] and has generated user empowerment with reviews that influence each other [75] through the phenomenon known as electronic Word of Mouth (eWoM), which, in relation to the recommendations of travel and tourist services online, has broken into the tourism sector with great force [76]. The most widespread definition of the eWoM effect is informal communications addressing consumers through Internet-based technology related to the use or characteristics of certain goods and services or their vendors [77], and it occurs through the transmission of User-Generated Content (UGC) published and disseminated via online media with a high degree of credibility that influences the behaviour and decision-making of tourists [78,79,80].

This traveller-generated content (TGC) about destinations and their services has become an important source of information for travellers [81] that is used to evaluate their search for information and their behaviour during the trip, describing travellers’ perceptions and the way in which they refer to the value of the information associated with the websites of the destinations [82]. Online Travel Reviews (OTRs) currently account for most TGC and have great academic value as a data source [83,84] regarding the analysis of perceived images; in particular, reviews taken from popular platforms such as TripAdvisor [85]. Moreover, their projection through eWOM communication makes them agents for building a destination image.

The content generated by other users through their OTRs serves to measure travellers’ satisfaction both through the text of their reviews and the numerical score awarded and has served as a source of study to measure satisfaction with tourist establishments and destinations [86,87,88,89]. In addition, OTRs exert a great influence when deciding which destination to travel to [90], with their valence and volume being among the factors that most influence the choice of destination [91]. The OTRs of an attraction or of a tourist establishment provide the opinion of the users through a textual description or a numerical rating (valence). In addition, the volume—i.e., the number of reviews—also serves to measure popularity [14]. A large number of reviews also brings more confidence to the people who read them [92,93], thus encouraging them to purchase the same product [94].

OTRs allow multiple classifications (by dates, location, origin and other personal or social circumstances of the author, quantity, rating, etc.). The items that are subject to opinion and assessment by travellers can be grouped into places frequented (typical neighbourhoods, boulevards, squares, etc.), attractions visited (unique buildings, monuments, parks, etc.), organized activities (excursions, tours, etc.) and services received (hotels, restaurants, transport, etc.). The websites that host OTRs usually include the first three under the heading of “Things to Do” (at the destination), while service OTRs are treated separately [86,95,96]

The number of reviews of a given attraction or service allows users to rank their popularity, so the most visited attractions or the most used services can be determined, while the users’ score facilitates the concretion of the evaluation dimension, which provides a precise idea of which attractions are rated best [97]. The number of reviews is also important to predict the percentage of people who write reviews online [98], to determine hotels’ dependency on an online travel agency [99], to ascertain the sales of a service or product [93,100,101], or to find out the profile of the hotels that are more efficient at generating reviews [102], among others.

Bearing in mind the significance of the number of reviews on a popular platform, this research aims to determine whether the most visited places in Barcelona according to the number of reviews on TripAdvisor are the places that appear on the cinematographic tourist routes created in the city, to find out on the one hand whether film fiction contributes to enhancing and increasing visits to tourist attractions and, on the other, whether the appearance of tourist attractions in films contributes to overtourism.

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study: Barcelona

The setting of this study is Barcelona—the most visited city in Spain, with more than 12 million overnight stays in 2018 (Barcelona, 2019). Barcelona has captured the attention of numerous investigations in relation to tourism [11,103,104] and, in the last few years, researchers have focused their studies on the externalities that the growth of tourism is causing in the city and especially for its citizens [69,72,105].

Catalonia, and particularly Barcelona, is a major centre of audio–visual production at the Spanish and European level. Between 2013 and 2017, 34.27% of feature films made in Spain were produced or co-produced by Catalan companies [106]. The city is the scene of numerous films and television series of Spanish and international productions, such as Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008), Salvador (2006), Todo sobre mi madre (in English, All about my mother, 1999), Perfume: The Story of a Murderer (2006), L’auberge espagnol (in English, Pot Luck, 2002), and Manuale d’amore (in English, Manual of Love, 2005), which are the films analysed in this study.

3.2. Thematic Routes: Barcelona Movie Walks

In the context of city, tourism and cinema interaction, Barcelona’s Destination Management Organization (DMO), Turisme de Barcelona, together with the School of Tourism, Hospitality and Gastronomy of the University of Barcelona (CETT-UB) offer thematic routes called the Barcelona Movie Walks on films filmed in Barcelona [107].

Barcelona Movie Walks is a compendium of 20 routes on foot encompassing more than 90 films and 200 locations in Barcelona created by Eugeni Osácar [108]. On the website created for those interested in Barcelona, cinema and cultural tourism activities, six film routes are highlighted [107] with a total of 65 locations, some of them taken from the films Vicky Cristina Barcelona, directed by Woody Allen, Salvador, by Manuel Huerga, Todo sobre mi madre, by Pedro Almodóvar, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, by Tom Tykwer, L’auberge espagnole, by Cédric Klapisch, and Manuale d’amore, by Giovanni Veronesi.

Even though tourists visiting mass destinations might not be interested in movies, or in these types of movies, and despite the fact that typically, film aficionados are interested in visiting places depicted in films, we consider that the case study of these film-based routes in Barcelona is relevant for the purpose of study as they have several characteristics which could make it one of the reasons for them to visit the city. There is a strong connection between Vicky Cristina Barcelona, L’auberge espagnole, Manuale d’amore, Todo sobre mi madre and Salvador to the extent that, at least in the three first films, the city is a character, and the plots are clearly determined by the fact that they are set in Barcelona (or reflect a certain image of the city). Besides, in relation to the specific locations in the city, paratextual elements become highly important (critiques, comments, information on the media, both before and after the premiere). In the case of Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, locations are even identified.

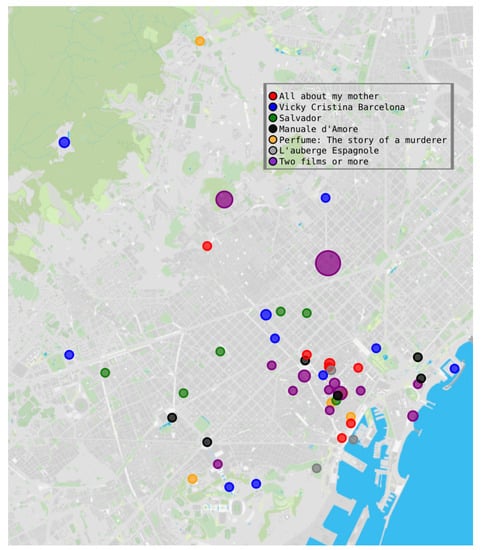

Figure 1 highlights the hotspots in each film according to the design of the routes by the Barcelona DMO, and the circle size indicates the number of reviews on TripAdvisor, which can also be seen in Table 1. The website www.barcelonamovie.com, based on the books of Eugeni Osácar [108], offers some of the routes of the books. This website is a collaboration between Barcelona City Council and the author’s university (CETT-UAB) with the institutional support of the Barcelona Film Commission. The books were funded by the public administration (Barcelona City Council and the Catalan Autonomous Government). These routes are not part of a commercialized package but are offered for information purposes as a different way to enjoy the city.

Figure 1.

Map 1: Main attractions shown in each film route in Barcelona. Source: Own elaboration, data from Barcelona Movie Walks (www.barcelonamovie.com) and TripAdvisor.

Table 1.

Tourist spots in Barcelona by number of reviews on TripAdvisor, and locations of the Movie Walks.

3.3. Reviews from TripAdvisor

The attractions of Barcelona according to TripAdvisor [109] in the section “Things to do” listed by popularity according to number of reviews are set out in Table 1, which also shows the number of Movie Walk routes related to the six analysed.

Numbers of the last column are related to the films analysed: 1. Vicky Cristina Barcelona, 2. Salvador, 3. All about my mother, 4. Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, 5. L’auberge espagnol, 6. Manuale d’amore.

4. Results

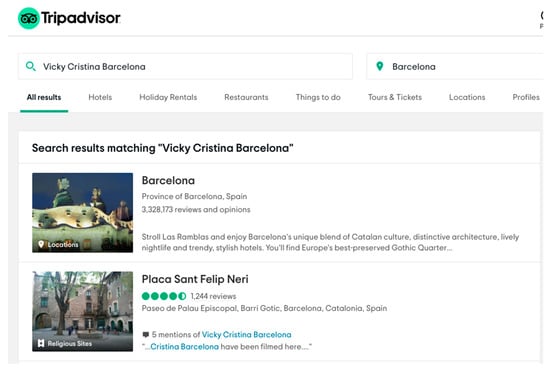

Using the TripAdvisor tool to look for a specific text within the reviews of each attraction (see Figure 2), a search in English for the titles of the six films analysed was carried out, and the results were that Vicky Cristina Barcelona is mentioned in 14 reviews (six of them in attractions and eight in cafes or restaurants); Perfume: The Story of a Murderer appears in two reviews, and there is an activity in “Things to Do” created about the film; two reviews were found in a restaurant about L’auberge espagnole; and no mentions were found regarding Salvador, Manuale d’amore, or All about my mother, although there were some about the director, Pedro Almodóvar.

Figure 2.

Search tool on TripAdvisor. (Source: TripAdvisor).

The six routes analysed stop at a total of 65 locations, some of which, as can be seen in Map 1, are repeated; in particular, these include the most well-known hotspots of Barcelona such as the Sagrada Familia, Park Güell or the Gothic quarter.

TripAdvisor offers information on a total of 963 “Things to Do” in the city of Barcelona, and the Barcelona DMO shows 65 locations in its most promoted film walking routes, called Barcelona Movie Walks. However, when the locations are analysed in depth, it can be observed that the top 10 attractions with the most reviews on TripAdvisor are in 20 locations of the six films analysed, the top 20 attractions appear in 27 locations, the top 30 attractions appear in 33 locations, and the top 40 attractions appear in 36 locations (i.e., 55.4% of the locations of the routes based on the six films analysed are among the top 40 attractions reviewed on TripAdvisor).

The route based on the film Vicky Cristina Barcelona visits 16 locations of which 10 (62.5%) are among the top 40 attractions reviewed on TripAdvisor; the route of the film Salvador has nine locations and only two (22%) are in the top 40; All about my mother visits 12 locations, four of which (33%) are in the top 40; Perfume: The Story of a Murderer has 10 locations, four of which (40%) are in the top 40; L’auberge espagnole has 12 locations, and six (50%) of them are among the most reviewed attractions on TripAdvisor; and lastly, Manuale d’amore has nine locations along the route, of which six (67%) are among the top 40 on TripAdvisor.

5. Discussion

The results show that, in general, the main points of interest along the six routes created by the Barcelona DMO based on the films analysed coincide with the main tourists attractions according to TripAdvisor, which are locations that also coincide with the top ten tourist attractions based on films, as suggested in [110]. The only film that shows different tourist attractions is Salvador, for which, apart from Plaça Reial and the Gothic quarter, the rest of the locations are not as famous as the others. This coincidence of the top tourist sites in Barcelona and the film locations on the routes seems to be opposite to the DMO’s intention to use film-induced tourism to decentralize tourism and promote other parts of the city [64] and are in line with the findings of Rodríguez-Campo et al. [66].

When performing an analysis of the textual description of the reviews of each attraction, as can be seen in Figure 1, we observe that the films that have generated most reviews are Vicky Cristina Barcelona, which is the second Woody Allen blockbuster, with sales of USD 96.4 million, followed by Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, with box office sales of USD 135 million, and L’auberge espagnole, with box office takings of USD 31 million.

According to the results, in few cases have the locations of the movies filmed in Barcelona contributed to spreading out tourists flows. In fact, with the blockbuster Vicky Cristina Barcelona, the images of Barcelona transmitted when viewing the film are Parc Güell, the Sagrada Familia, Gaudi, and the Rambla [12], which coincide with the top ten hotspots of Barcelona. Only films with lower audiences, such as Salvador, contribute to spreading tourism flows throughout the city. Regarding limitations, there is a need to study other film-based routes in Barcelona and other saturated destinations to shed light on the differential contribution by blockbuster films versus lower-audience films to the sustainability of the destination and the alleviation of overtourism.

The threads regarding the films do not seem to have continuity on TripAdvisor, as not many reviews have been found talking about the films and only a few reviews of the attractions mention the blockbusters Vicky Cristina Barcelona and Perfume: The Story of a Murderer. In any case, the movies analysed do not generate as many reviews on TripAdvisor as other much more famous films or series, such as Lord of the Rings or Game of Thrones. There are several studies which have analysed the impact of Lord of the Rings in New Zealand [38,67,111,112,113].

Therefore, concerning this study’s contribution to appraising the role that film tourism has towards sustainable tourism development and overtourism, in a city such as Barcelona, we can appreciate a gap between the DMO’s strategic view of film tourism [64] and the reality, as film-based routes currently serve to bring more people to the top sites and do not generate much promotion through user-generated content. Thus, referring to management implications, this gap could be due to the lack of collaboration of the film industry [9] with the DMO when designing Barcelona’s image to avoid certain top sites and stereotypes. Besides, this could be due to the lack of real policies or assessment of the film-based routes, as the main limitation of this study is that no statistical data are available in this respect.

6. Conclusions

Overtourism has become a problem for many destinations and is set to continue. The excess of visitors in places such as Barcelona needs to be managed to prevent an increase in anti-tourism movements, which could be done by means of culture and art-related tourism, as they are seen as more sustainable forms of tourism. In recent years, film tourism has become an opportunity to promote destinations, but only a few studies have questioned the sustainability of this type of tourism [9].

With a case study about Barcelona, this research contributes to the existing literature about film-induced tourism and overtourism, showing that, far from contributing to distributing tourist flows throughout the city, film fiction actually concentrates these visitors at the main attractions of the city, thus increasing the presence of tourists in already crowded locations, which is particularly true for locations based on blockbuster films. Only some exceptions of films with “minor audiences” direct tourists off the beaten track.

The use of audio–visual fiction to diversify tourists at a destination poses a series of challenges for destination marketing organizations, film offices, and production companies, which requires them to coordinate their work [43,58,59]; the academic world must undoubtedly participate in this collaboration with teams of cross-disciplinary researchers composed of experts in tourism, audio-visual communication and advertising.

Tourist destinations are places, and the place is one of the main themes in audio–visual narration. Hence, this is especially suitable for the location of destinations. Cinema occupies an important place among tourists’ motivations for visiting a destination and, apart from being a way of transmitting the image of a destination in the consumers’ minds, it can contribute to generating tourist flows, meaning that, in the case of overtourism destinations, care must be taken not to promote precisely the most saturated hotspots. Thus, designing careful destination image strategies that align the images portrayed in films with the image desired by the destinations is becoming very important [67]. Well-aligned and planned strategies can help alleviate overtourism and contribute to destination sustainability and the diversification of tourism flows, but inappropriate strategies may aggravate the problem. Choosing an inappropriate movie to convey the image of a destination may damage its positioning [12], while promoting sites visited en masse can also contribute to damaging the destination image. Exceeding the carrying capacity of the tourist resource entails problems in the management and conservation of the resource but also harms the visitor’s tourist experience and, therefore, the perceived image of the destination.

In-depth knowledge of the operation of audio-visual texts will allow their effective use for tourism promotion. However, audio–visual fiction does not act alone. It is important to enhance the impact that audio–visual fiction has on the image of a place, as well as the motivations and decisions to visit the places in which their stories are set. This is possible by resorting to prior communicative initiatives, parallel to the production of a film or series—disseminating information about the locations of the shooting, about the stars participating in it, and so on—or after the premiere in the different exhibition windows—the making of documentaries where film locations stand out—in order to broaden the results for the tourist space site.

With regard to destination managers, they are faced with the challenge of correctly choosing the tourist resources they wish to communicate through the cinema, finding a balance between the carrying capacity of the attractions of the destination to avoid overtourism in the main attractions of Barcelona, the interests of residents and tourists, and the image they seek to transmit from their destination. Undoubtedly, it is a challenge to reconcile this proposal with the interests of audio–visual producers, who display the iconic images of Barcelona—which is saturated with visitors—to try to increase the audience of their films. In this respect, the dilemma might be whether it is enough for the most recognizable sights of a city to appear in a film or in a series, which thus does not help to diversify tourism, or if it is possible to seek a balance between what is recognizable and what is not as recognizable with the aim of showcasing other places, and perhaps, by drawing from the audio-visual and many other stimuli (paratextual content, subsidies, among others), to redistribute visitors to these places. This may imply negotiating with film producers.

Regarding future research, the main limitation of this study is the lack of information about the number of tourists coming to Barcelona motivated by audio–visual fiction with the intention to visit certain places that appear in films and television series. The DMO, Turisme de Barcelona, does not have statistics of visitors disaggregated by audio–visual fiction in this city. Thus, from the point of view of the demand, is it not possible to confirm whether this type of tourism is contributing to overtourism in Barcelona, but it is possible to confirm that the points of interest offered by the movie routes are mostly the well-known places.

Likewise, to measure the popularity of tourist attractions in Barcelona, the TripAdvisor platform has been used. It is the world’s largest online travel review site and, therefore, the results are representative of its popularity. However, some visitors may not be willing to mention the film in their online reviews, and TripAdvisor is not the only platform that exists. For this reason, other online review sites such as Yelp or Google Reviews could be taken into account to empirically replicate this research, and surveys on visitors to the film-related places could be conducted.

Furthermore, since not all the movie routes of the city of Barcelona have been analysed (only the six most popular thematic ones promoted by the DMO, Turisme de Barcelona, through its website), further research could extend this study to other movie routes in Barcelona and even to other destinations that suffer from overtourism.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry and Competitiveness (grants ID ECO2017-88984-R, TIN2015-71799-C2-2-P, and HAR2016-77734-P), and the support of the Institute of Social Development and Territory INDEST of University of Lleida (call 2018CRINDESTABC). First author also acknowledges the support of the Spanish Education Ministry for the abroad mobility stay “José Castillejo” (Ref. Number CAS19/00362).

Acknowledgments

This research article has received a grant for its linguistic revision from the Language Institute of the University of Lleida (2020 call).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Martín, J.M.M.; Martínez, J.M.G.; Fernández, J.A.S. An Analysis of the Factors behind the Citizen’s Attitude of Rejection towards Tourism in a Context of Overtourism and Economic Dependence on This Activity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Hernández, M.; Baidal, J.I.; Mendoza de Miguel, S. Overtourism in urban destinations: the myth of smart solutions. Boletín la Asoc. Geógrafos Españoles 2019, 83, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, C.; Fabry, N. Influence of new cinematographic and television operators on the attractivity of tourist destinations. J. Tour. Futur. 2020, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P. Cinematographic images of a city. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeton, S. Film-induced Tourism. In Multilingual Matters; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2005; p. 278. ISBN 9786610627875. [Google Scholar]

- Kigawa, T. Japan World’s Tourism Film Festival: Seeking for sustainable tourism films. J. Glob. Tour. Res. 2019, 4, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, S. Film Tourism Planning and Development—Questioning the Role of Stakeholders and Sustainability. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2010, 7, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszak, J.-F.; Marine-Roig, E., Translators; Introducció al dossier. Via Tour. Rev. 2018, 14. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/viatourism/2922 (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S.; Dosquet, F.; del Olmo Arriaga, J.L. The dark side of digital technology to overtourism: the case of Barcelona. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Campo, L.; Fraiz Brea, J.A.; Rodríguez-Toubes Muñiz, D. Tourist destination image formed by the cinema: Barcelona positioning through the feature film Vicky Cristina Barcelona. Eur. J. Tour. Hosp. Recreat. 2011, 2, 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Aertsen, V.U. El cine como inductor del turismo. La experiencia turística en Vicky, Cristina, Barcelona. Razón y palabra 2011, 16, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, K.L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. The business value of online consumer reviews and management response to hotel performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 43, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.W.; Van Doren, C.S. Movies as tourism promotion. Tour. Manag. 1992, 13, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.; Baker, D.; Doren, C.S.V. Movie induced tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grihault, N. Film tourism-the global picture. Travel Tour. Anal. 2003, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Richardson, S.L. Motion picture impacts on destination images. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercille, J. Media effects on image. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1039–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, W. Braveheart-ed Ned Kelly: historic films, heritage tourism and destination image. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolan, P.; Williams, L. The role of image in service promotion: focusing on the influence of film on consumer choice within tourism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shani, A.; Wang, Y.; Hudson, S.; Gil, S.M. Impacts of a historical film on the destination image of South America. J. Vacat. Mark. 2009, 15, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashita, C. Media representation of the UK as a destination for Japanese tourists: Popular culture and tourism. Tour. Stud. 2006, 6, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwashita, C. Roles of Films and Television Dramas in International Tourism: The Case of Japanese Tourists to the UK. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 24, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Schuckert, M.; Chon, K.; Schatzmann, C. Empire and Romance: Movie-Induced Tourism and the Case of the Sissi Movies. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2011, 36, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo-García, M.Á.; Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Trujillo-García, M.A.; Mallya, T. Film-induced tourist motivations. The case of Seville (Spain). Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 713–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, W.G.; Walker, R.D. Rural tourism and film-issues for strategic regional development. In New directions in rural tourism; Hall, D., Roberts, L., Mitchell, M., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 2003; pp. 115–133. ISBN 075463633X. [Google Scholar]

- Croy, W.G. Film tourism: sustained economic contributions to destinations. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2011, 3, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffont, G.H.; Prigent, L. Paris transformed into an urban set: dangerous liaisons between tourism and cinema. Teoros, Rev. Rech. en Tour. 2011, 30, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, S. The Borat Effect: Film-Induced Tourism Gone Wrong. Tour. Econ. 2015, 21, 977–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N. The view from inside the ’simulacrum‘: visitors’ tales from the set of Coronation Street. Leis. Stud. 1998, 17, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N. On the actual street. In The Media and the Tourist Imagination. Converging Cultures; Crouch, D., Jackson, R., Thompson, F., Eds.; Routledge London: London, UK, 2005; pp. 60–75. ISBN 02031392911. [Google Scholar]

- Månsson, M. Mediatized tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1634–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydney-Smith, S. Changing places: Touring the British crime film. Tour. Stud. 2006, 6, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roesch, S. The experiences of film location tourists; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2009; Volume 42, ISBN 184541120X. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann, A.; Moore, K.; Fisher, D. Experiencing film tourism: authenticity and fellowship. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peaslee, R.M. One Ring, Many Circles: The Hobbiton Tour Experience and a Spatial Approach to Media Power. Tour. Stud. 2011, 11, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carl, D.; Kindon, S.; Smith, K. Tourists’ Experiences of Film Locations: New Zealand as ‘Middle-Earth’. Tour. Geogr. 2007, 9, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnders, S. Watching the Detectives. Eur. J. Commun. 2009, 24, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnders, S. Places of the imagination: an ethnography of the TV detective tour. Cult. Geogr. 2010, 17, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Extraordinary Experience: Re-enacting and Photographing at Screen Tourism Locations. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2010, 7, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, J. ‘What’s the Story in Balamory ?’: The Impacts of a Children’s TV Programme on Small Tourism Enterprises on the Isle of Mull, Scotland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2005, 13, 228–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Ritchie, J.R.B. Promoting Destinations via Film Tourism: An Empirical Identification of Supporting Marketing Initiatives. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, N.; Flanagan, S.; Gilbert, D. The integration of film-induced tourism and destination branding in Yorkshire, UK. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B. Branding and the opportunities of movies: Australia. In Destination Brands; Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., Pride, R., Eds.; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 239–250. ISBN 1136346627. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, C.A. Vacationscape: Designing Tourist Regions; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1972; ISBN 978-0877551614. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner, W.C. Image Formation Process. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 1993, 2, 191–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies; Sage Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 1990; ISBN 0-8039-8182-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tooke, N.; Baker, M. Seeing is believing: the effect of film on visitor numbers to screened locations. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macionis, N. Understanding the film-induced tourist. In Proceedings of the International tourism and media conference proceedings, Tourism Research Unit, Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, 24–26 November 2004; Volume 24, pp. 86–97. [Google Scholar]

- Frost, W. Life changing experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 707–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Ryan, C. Interpretation, Film Language and Tourist Destinations: A Case Study of Hibiscus Town, China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 334–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Tsang, N. Inducible or Not—A Telltale from Two Movies. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndiz Noguerol, A. Estrategias de «city placement» (emplazamiento de ciudades en el cine) en la promoción del turismo español. El caso de Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara (Sólo se vive una vez, 2011). Pensar la Publicidad. Rev. Int. Investig. Public. 2014, 8, 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndiz, A. City placement: concepto, literatura científica y método de análisis. In Nuevos Tratamientos Informativos y Persuasivos; Calandria, M.M., CALANDRIA, E.C., Eds.; Tecnos: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Ferrando, J.; del Rey Reguillo, A.; Afinoguenova, E. Narración, Espacio y Emplazamiento Turístico en el cine Español de Ficción (1951–1977); La Laguna: Tenerife, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Busby, G.; Klug, J. Movie-induced tourism: The challenge of measurement and other issues. J. Vacat. Mark. 2001, 7, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.; Pritchard, A. Tourism promotion and power: Creating images, creating identities; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 0471983411. [Google Scholar]

- Cynthia, D.; Beeton, S. Supporting Independent Film Production Through Tourism Collaboration. Tour. Rev. Int. 2009, 13, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. From carrying capacity to overtourism: a perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Palomeque, F. Barcelona de ciudad con turismo a ciudad turística. Notas sobre un proceso complejo Ina. Doc. dAnalisi Geogr. 2015, 61, 483–506. [Google Scholar]

- Milano, C.; Mansilla, J.A. Ciudad de Vacaciones: Conflictos urbanos en espacios turísticos. Barcelona Spain Pol· len Ediciones 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Séraphin, H.; Zaman, M.; Olver, S.; Bourliataux-Lajoinie, S.; Dosquet, F. Destination branding and overtourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 38, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osácar, E.M. Del turismo y el cine al turismo cinematográfico. Her&Mus. Herit. Museogr. 2009, 2, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wray, M.; Croy, W.G. Film Tourism: Integrated Strategic Tourism and Regional Economic Development Planning. Tour. Anal. 2015, 20, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Campo, L.M.; Fraiz-Brea, J.A.; Araújo-Vila, N. The evolution of film tourism in Spain. A comparative analysis from the supply-side perspective. Tour. Anal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, W.G. Planning for Film Tourism: Active Destination Image Management. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2010, 7, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E. Destination Image Analytics through Traveller-Generated Content. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.D.M.; Borrajo-Millán, F.; Yi, L. Are Social Media Data Pushing Overtourism? The Case of Barcelona and Chinese Tourists. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Law, R.; Gu, B.; Chen, W. The influence of user-generated content on traveler behavior: An empirical investigation on the effects of e-word-of-mouth to hotel online bookings. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2011, 27, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Formica, S.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Tribal marketing for destination websites: A case study of RV enthusiasts. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Travel and Tourism Research Association Conference, Boise, ID, USA, 12–15 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brandajs, F.; Russo, A.P. Whose is that square? Cruise tourists’ mobilities and negotiation for public space in Barcelona. Appl. Mobilities 2019, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macionis, N.; O’Connor, N. How can the film-induced tourism phenomenon be sustainably managed? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2011, 3, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Daries-Ramon, N. User-Generated Social Media Events in Tourism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, A.; Tkaczynski, A.; Dolnicar, S. Word-of-mouth segments: online, offline, visual or verbal? J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayeh, J.K.; Au, N.; Law, R. ‘Do We Believe in TripAdvisor?’ Examining Credibility Perceptions and Online Travelers’ Attitude toward Using User-Generated Content. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gretzel, U.; Yoo, K.H. Use and Impact of Online Travel Reviews. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2008; O’Connor, P., Höpken, W., Gretzel, U., Eds.; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2008; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, I.E.; Seegers, D. Tried and tested: The impact of online hotel reviews on consumer consideration. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukpabi, D.C.; Karjaluoto, H. What drives travelers’ adoption of user-generated content? A literature review. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 251–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, C.; Burgess, S.; Sellitto, C.; Buultjens, J. The Role of User-Generated Content in Tourists’ Travel Planning Behavior. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 743–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlee, S.; Lee, H.; Koo, C. Hospitality and Tourism Online Review Research: A Systematic Analysis and Heuristic-Systematic Model. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Du, Q.; Ma, Y.; Fan, W. A comparative analysis of major online review platforms: Implications for social media analytics in hospitality and tourism. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E.; Mateu, C.; Fernandez, C. Does Verifying Users Influence Rankings? Analyzing Booking.Com and Tripadvisor. Tour. Anal. 2018, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Park, S.A. Social media review rating versus traditional customer satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 784–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Borghi, M.; Gretzel, U. Online reviews: Differences by submission device. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E.; Fernandez, C.; Mateu, C.; Marine-Roig, E. Modelling a grading scheme for peer-to-peer accommodation: Stars for Airbnb. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 69, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios, M.Á.; Ortega, F.J.; Matilla, M. La estancia perfecta en hoteles de 4 y 5 estrellas de Sevilla a través del análisis de los comentarios en TripAdvisor - Determinación de los principales ítems. Int. J. Inf. Syst. Tour. 2016, 1, 8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sparks, B.A.; Perkins, H.E.; Buckley, R. Online travel reviews as persuasive communication: The effects of content type, source, and certification logos on consumer behavior. Tour. Manag. 2013, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.R.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Law, R. The influence of online reviews to online hotel booking intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1343–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E.; Mateu, C.; Fernandez, C. The more the merrier? Number of reviews versus score on TripAdvisor and Booking.com. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2020, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Zhang, X. Impact of online consumer reviews on sales: The moderating role of product and consumer characteristics. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarocas, C. The digitization of word of mouth: Promise and challenges of online feedback mechanisms. Manage. Sci. 2003, 49, 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fuentes, E. Are guests of the same opinion as the hotel star-rate classification system? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 29, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Zach, F. Identifying salient attributes of peer-to-peer accommodation experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 636–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marine-Roig, E.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B. A Framework for Destination Image Analytics. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2019; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Mellinas, J.P. What Percentage of Travelers Are Writing Hotel Reviews? In Trends in Tourist Behavior. Tourism, Hospitality & Event Management; Artal-Tur, A., Kozak, M.K.N., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fuentes, E.; Mellinas, J.P. Hotels that most rely on Booking.com – online travel agencies (OTAs) and hotel distribution channels. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 465–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, J.A.; Mayzlin, D. The Effect of Word of Mouth on Sales: Online Book Reviews. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C.; Ghose, A.; Wiesenfeld, B. Examining the Relationship Between Reviews and Sales: The Role of Reviewer Identity Disclosure in Electronic Markets. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinas, J.P.; Martin-Fuentes, E. Does hotel size matter to get more reviews per room? Inf. Technol. Tour. 2019, 21, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Marine-Roig, E. Do Hotels Talk on Facebook About Themselves or About Their Destinations? In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 344–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Martin-Fuentes, E.; Marine-Roig, E. Diverse and emotional: Facebook content strategies by Spanish hotels. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2020, 22, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, N.; Palou Rubio, S. From Barcelona: The Pearl of the Mediterranean to Bye Bye Barcelona. In Tourism in the City; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 285–295. [Google Scholar]

- Idescat Producción de Largometrajes. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/pub/?id=eac&n=2.1.2&lang=es (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Barcelona Turisme Barcelona Movie Walks (2019). Retrieved from on 20th August 2019. Available online: http://www.barcelonamovie.com/rutes.aspx (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Osácar Marzal, E. Barcelona, una Ciudad de Película; Diéresis, Ajuntament de Barcelona, Ed.; Diéresis, S.L.: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; ISBN 9788494143809. [Google Scholar]

- TripAdvisor Things to do in Barcelona. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Tourism-g187497-Barcelona_Catalonia-Vacations.html (accessed on 20 August 2019).

- Osácar Marzal, E. La imagen turística de Barcelona a través de las películas internacionales. PASOS. Rev. Tur. y Patrim. Cult. 2016, 14, 843–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, A. Planning and Development in Film Tourism: Insights into the Experience of Lord of the Rings Film Guides. Tour. Hosp. Plan. Dev. 2010, 7, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.; Smith, K. Middle-earth Meets New Zealand: Authenticity and Location in the Making of The Lord of the Rings. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 923–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peaslee, R.M. ‘The man from New Line knocked on the door’: Tourism, media power, and Hobbiton/Matamata as boundaried space. Tour. Stud. 2010, 10, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).