Abstract

The knowledge of evaluation instruments to determine the level of gameplay of schoolchildren is very important at this time. A systematic review has been carried out in this study. The aim of this paper is to investigate the psychometric properties of a study of a sample of Spanish gamers. Two hundred and thirty-seven children (mean age: 11.2± 1.17 years, range: 10-12 years, 59.5% female) completed the Gameplay-Scale to discover their opinions after a game session with a serious educational game. The final scale consisted of three factors. The fit for factor 1 (usability) was 0.712, the fit for factor 2 was 0.702 (satisfaction), the fit for factor 3 was 0.886 (empathy) and the overall fit was 0.868. A positive and direct relationship could be observed between all the dimensions of the developed scale. The greatest correlation strength is shown between satisfaction and empathy (r = 0.800; p < 0.005), followed by satisfaction and usability (r = 0.180; p < 0.05) and the association between empathy and usability (r = 0.140; p < 0.05). In summary, the results of the present study support the use of the Gameplay-Scale as a valid and reliable measure of the game experience of youth populations. These results demonstrate strong psychometric properties so that the Gameplay-Scale appears to be a valid instrument for children in different contexts where an educational video game is used, analyzing its usability/“playability” in terms of learning to use it, game satisfaction, and empathy.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there have been many changes in society, most of which are related to the digital phase that has invaded all areas of life. This is especially marked in the younger sectors of the population, resulting, in some cases, in new forms of fun and entertainment. In particular, video games are a popular type of entertainment software that incorporates principles from multimedia and gameplay, which are being used with the additional purpose of improving certain areas of knowledge and skills. Specifically, in education, serious games are becoming important instructional tools and are increasingly being integrated into courses in many different areas to help individuals concentrate on the subject matter and enjoy learning [1]. Serious games offer new learning opportunities, providing challenging tasks that promote more autonomous and exciting instruction. Their flexibility in use and scalability makes them an attractive pedagogic instrument, but it is necessary to check the effectiveness of serious games compared to more traditional formats. With this aim, in Dankbaar et al. [2], a comparison with e-modules was performed, concluding that video-lectures (in a game) and text-based lectures (in an e-module) can be equally effective, although serious games are more motivating in the long term.

Numerous efforts have been made to evaluate the effectiveness of serious educational games and a large number of educational advantages has been revealed [3,4,5,6,7]. However, as the demand for this type of game increases, game developers face the challenge of creating games that are not only effective but also attractive to play. Since there are different opinions on the essential elements that constitute a “good game” [8], it is not easy to determine which criteria should be analyzed to assess the suitability of a video game and, especially, of a serious educational game. It is exceedingly hard to adequately describe and measure a gaming experience because there is a great variety of games and the kinds of experiences that users will have when playing these games will differ considerably [9].

As a consequence, in order to adequately judge the impact of the design of the game on the user experience, traditional usability metrics must be redefined to incorporate the game elements in an overlay model.

The systematic review of the literature, described in the next section of this work, shows that, although many creators of video games and in particular serious educational games have conducted evaluations with significant user populations, there is currently no standard questionnaire to extract the opinion of the users about their experiences during a game session. Existing questionnaires are partial, dependent on the area of application, and are often too complex. To fill this gap, we propose a very simple questionnaire (Gameplay-Scale) that can be used by children and which has been used to evaluate a serious game for comprehensive reading in an educational experience carried out with 237 students between 10 and 12 years old.

Regardless of the effectiveness of the game (which will require evaluation methods specific for the purpose of the game, in our case pre-tests and post-tests of comprehensive reading), the opinion questionnaire about a serious educational game should consider several factors, such as: The difficulty perceived by the users in learning to play the game, the ease and pleasantness of the game environment, the satisfaction produced in the player about each element of the game, etc. With this aim, a questionnaire (Gameplay-Scale) to discover the opinion of the users of an educational game in terms of learning about the game, ease of use, satisfaction about graphics, sounds, interaction mechanisms, story and narrative, characters, challenges, rewards and empathy is presented, applied, and validated in the rest of this paper. Additionally, two questions were included in the evaluation experience to analyze the player immersion understood as the degree to which the serious component of the game, that is, the learning process, is implicit, and therefore, goes unnoticed by the player.

2. Related Work

We conducted a systematic search in the main collection of the Web of Science to identify the efforts made in the last ten years (2008 to 2018) in relation to the evaluation of video games and serious games. Finally, our interest will focus on serious educational games, but this broader vision will help. Concretely, the search for studies comprising a “questionnaire”, “poll”, or “survey” to discover the opinion of the players of the games retrieved over 621 results (within the categories Science Technology and Social Sciences).

This search was later refined to select studies including some of the following topics: a) “Human computer interaction” (or “human–computer interaction”), b) “validation” and/or “evaluation” of a proposal, c) quality attributes of the video game, such as: “Usability”, “ease of use”, “learnability”, “effectiveness”, user “satisfaction”, “playability”, “empathy”, and “awareness of learning”, and d) elements of the game, such as: “Graphics”, “sound”, “story”, “characters”, “avatar”, “challenges” and “scoring” (or “score”). The number of studies taking into account some of these topics (or a combination of them) was reduced from 621 to 252 papers. The title of each paper in this set of 252 papers was analyzed to determine its suitability to be part of our review. This filtering process allowed us to discard all those studies where, through the title, it seemed clear that the contribution of the paper was not concerned with evaluating a specific game nor a set of them nor even the concept of a video game itself.

Studies focused on the analysis of physical or psychological aspects of the player were also ignored. As a result, 84 papers were selected and their abstracts were read. During this systematic search of the scientific literature, some topics unrelated to our object were excluded: Video game addictions, violence, health, teachers’ opinion about the educational use of the game, etc. Exactly 34 papers were selected based on the abstract. Finally, after a complete reading, 30 studies were found that deal with the evaluation of a video game or serious game from the perspective of discovering the opinion of its players after the experience of playing the game.

Of the 30 reviewed studies, more than half (17 papers) refer to serious educational games. Nevertheless, all proposals of evaluation questionnaires for video games and serious games were analyzed to get a broader view. During our study, it was detected that there is a great diversity of proposals to evaluate the experience of using a game, but there is no standard. Since there is no widely accepted evaluation test, we tried to classify the different approaches found. The aim of this effort of classification is to identify common points among the existing proposals and to facilitate the work of future researchers/educators who need to face this task.

Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the performed classification, focusing only on the proposals of evaluation for serious educational games. Table 1 describes the proposals of evaluation questionnaires that put the emphasis on the learning generated as a result of the use of the game. Table 2 describes the proposals of evaluation questionnaires that deal very closely with the user experience during the game. In both cases, the following information is included: Main objective of the proposed evaluation questionnaire, type of users who have answered the questionnaire (population), attributes considered in the items of the questionnaire, and attributes used in the questionnaire to evaluate the usability of the game (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Proposals of evaluation for serious educational games (focused on learning).

Table 2.

Proposals of evaluation for serious educational games (focused on experience of use).

During the complete review of the 30 papers, we found some previous models that can be useful to define certain aspects of an evaluation questionnaire for video games (or serious games). For example, in Agarwal and Karahanna [18], an interesting, multidimensional conceptualization of cognitive absorption about information technologies usage is presented. This construct is exhibited through five dimensions: Temporal dissociation, immersion, enjoyment (pleasurable aspects of the interaction), control over the interaction, and curiosity. In addition, a nomological net is defined, trying to capture relations among the cognitive absorption and other factors, such as personal innovativeness, playfulness, self-efficiency, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and behavioral intention of use.

This model has been used (with adaptations) in Wang et al. [1], however, the multidimensional construct is focused on cognitive absorption and is not specific to video games. In a similar line, in Malhotra and Galletta [15] a multidimensional commitment model of volitional systems adoption and usage behavior is presented (also used in Wang et al. [1]). In this model, the commitment to system use appears related to perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and attitudes toward using and behavioral intent. Because voluntary systems require users’ volitional behavior, this model may be applicable to video games. However, again this proposal does not cover the particularities of this type of ludic system. A complementary approach is the presence questionnaire proposed in Witmer and Singer [24] to measure the subjective experience of being in one virtual environment. This questionnaire has been adopted in Lorenzini et al. [23] and its items are organized into six subscales: Sensory exploration, involvement, interface awareness, control responsiveness, reality/fidelity, and adjustment/adaptation. The questionnaire addresses the sensation of presence during the user experience in the virtual environment in a comprehensive manner, but does not include the rest of the elements of a video game: Story, challenges, characters, etc.

Additionally, a few existing models to evaluate usability were found during the review. For example, TURF [28] is a unified framework of EHR (Electronic Health Records) usability. Under TURF, usability is understood through three dimensions: Usefulness, usability, and satisfaction. This approach, followed in Johnsen et al. [19], is structured as a set of representative measures: Across-model domain function saturation, within-model domain function saturation, learnability, efficiency, error prevention and recovery, and user impression of how useful, usable, and likable the system is. Another interesting proposal in this line is the System Usability Scale (SUS) in Brooke [25], which is followed in Lorenzini et al. [23], Boletsis and McCallum [29], and Vallejo et al. [30].

SUS is a simple, Likert ten-item scale giving a global view of subjective assessments of usability. Evaluated aspects in SUS are: Easy to learn to use, easy to use, integration of functions and consistency, like using, and confidence. Again, none of these two approaches is specific to video games, so they need to be adapted to take into consideration the characteristics of this type of software.

Regarding models specific for video games, very few contributions can be mentioned. For example, in Norman [31], a review of two very interesting questionnaires is presented: Game Experience Questionnaire and Game Engagement Questionnaire. The Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ) [9] involves usability, flow, and immersion and consists of three modules: Experiences during gameplay, social presence, and experiences once a player has stopped playing the game. Questions in each module deal with how the user feels (successful, bored, frustrated, challenged, etc.) and the only element of the game explicitly referenced is the story. The In-Game Experience Questionnaire (iGEQ) is the shorter in-game version of the Game Experience Questionnaire and contains 14-items, rated on a five-point intensity scale distributed between seven dimensions: Immersion, flow, competence, tension, challenge, negative affect, and positive affect [28]. For its part, the Game Engagement Questionnaire [32] aims to provide a measure of an individual’s potential for becoming engaged in video gameplay at differing levels, taking into account presence, flow, absorption, and dissociation.

In conclusion, during the systematic search, we reviewed very different proposals to evaluate the user experience during the utilization of a video game and also of a serious game (proposals for serious educational games are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2). Although we found a few already accepted models that can be used to define certain dimensions of the required questionnaires, there is no standard model or test for this evaluation task. In addition, most of the proposals found during the performed systematic review process are partial and are not specific to video games (much less for serious educational games). One of the most complete revised questionnaires is GUESS (Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale) [8]. GUESS includes attributes to evaluate: Usability/playability, narratives (characters, story, etc.), play engrossment, enjoyment, creative freedom, audio aesthetics, personal gratification, social connectivity, and visual aesthetic. In addition, this proposal defines usability centered on the game (for example, it includes ease of navigation, the manual to play the game, etc.). However, GUESS is not specific to educational games and consists of 55 items with nine subscales, so it does not seem appropriate for children. More precisely, only three papers were included in the systematic map focus on children: Canals et al. [27], putting the emphasis on aspects of the game [33] putting the emphasis on enjoyment and Harrington and O’Connell [34] with the focus on empathy and prosocial behavior.

Accordingly, a new questionnaire to evaluate the user experience during the game, Gameplay-Scale, is proposed in this paper. This proposal takes into account the specific elements of the game (story, characters, challenges, etc.) and the player’s perception during their interaction with the game, including how he/she identifies with their own representation within it (that is, the avatar). In addition, the level of awareness of the user about their own educational process (awareness of learning during the game) was consulted to the players to analyze the ludic–educational balance of the game. The questionnaire has been specifically designed to be suitable to be answered by children.

Thus, the literature shows the need to work with new tests in order to quantify the player’s experience during the game, knowing the degree of gameplay of video games and, accordingly, improving the attitude towards them. We aimed to perform confirmatory analysis (CFA) to confirm the factor structure obtained via exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and so have an assessment instrument in which validity is tested. Consequently, the main purpose of this study was to develop a valid and reliable Gameplay-Scale for child players.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Design

School students from three schools in Granada (Spain) participated in this descriptive and cross-sectional study. We analyzed 237 Spanish schoolchildren between 10 and 12 years old (11.2±1.17). This sample is representative of children in this age group from Granada (n = 20.606), finding the sample error at 0.04 with 95% confidence. Of these, 40.5% were male and 59.5% were female participants. Conglomerate sampling (a probabilistic sampling unit in the conglomerate) was used to select participants.

3.2. Measures

The 12-item Gameplay-Scale was used to assess the user experience of games in children through play “Invasores del tiempo” (versión PC the game: http://bios.ugr.es/~nmedina and versio Android App Store of Google Play: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.UGR.LosInvasoresDelTiempo). This questionnaire was previously cited by Zurita-Ortega, Medina-Medina, Chacón-Cuberos, Ubago-Jiménez, Castro-Sánchez, and González-Valero [35]. This questionnaire of twelve items of closed questions is valued by means of a Likert scale of five options where 1 is totally in disagreement and 5 is totally in agreement. However, our target population requires a prior adaptation and validation as these validation tests do not exist for this cultural group and subjects.

Additionally, during the evaluation experience, two questions were used to analyze the extent to which the educational process is hidden from the player (awareness of the learning process), which is key to increasing the motivation, and therefore, the effectiveness of the game. These questions were: “Indicate to what degree you have noticed that you were learning” and “What have you learned with the game?” Only 8.01% of children detected that they were working on “comprehensive reading”, although the average degree of awareness of learning was 3.39. These results suggest an adequate ludic–educational balance and an adequate degree of immersion during the game.

3.3. Procedure

The inclusion criteria for the participants were that they were enrolled in Primary Education. A total of 273 students sent their informed consent through their parents. The questionnaires were administered during May 2017 (after they finished a game session with a graphic adventure for comprehensive reading by Lope, Arcos, Medina-Medina, Paderewski, and Gutierrez-Vela [36]). We eliminated 26 participants who did not complete the questionnaires properly. During the data collection, the investigators were present, and the participants were informed that the information was completely confidential and anonymous. Previously, authorization was obtained from the ethics committee of the University of Granada and authorization from educational centers, and informed consent was requested from all participants.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

First, the SPSS 24.0 program was used to determine the descriptive statistics of the data (mean, kurtosis, asymmetry, and standard deviation). Once these were verified, the FACTOR 9.3.1 program was applied by Lorenzo-Seva and Ferrando [37] to determine the psychometric properties and establish the confirmatory factorial analysis. Finally, the AMOS version 22.0 was used to establish the model of equations. To develop the statistical model, confirmatory factor analysis was first used to check the reliability and validity of the research tool. Next, relationships between all the latent variables and the categories of the model were identified.

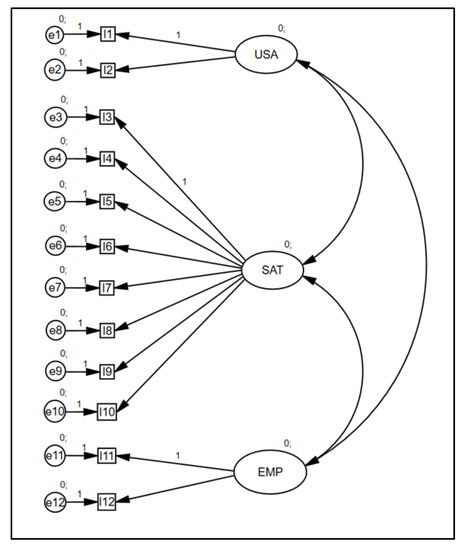

Structural equation analysis was employed in order to analyze the relationships between satisfaction, usability, and empathy. The structural model was composed of three latent variables and twelve observed variables that enabled causal explanations to be obtained of the associations between both types of variables and their indicators. In addition, circles constitute the error terms and squares are the observed variables, as can be observed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model theories. Note: USA, Usability; SAT, Satisfaction; EMP, Empathy.

In this sense, satisfaction, empathy, and usability are exogenous variables and they are composed of different indicators that are the items of the instrument (Usability: V01, V02; Satisfaction: V03, V04, V05, V06, V07, V08, V09, V10; Empathy: V11, V12). It is important to highlight that the method of maximum likelihood (ML) was employed in order to estimate the parameters of the structural models. This method is invariant to types of scale and allows to establish that all variables have a normal distribution.

Finally, the model’s fit was tested in order to check the adjustment of the structural model with the empirical information obtained. For this aim, several indices were used: P, CFI, AGFI, GFI, and RMSEA. Following the statements established by Hu and Bentler [38] and Schmider, Ziegler, Danay, Beyer, and Bühner [39], values higher than 0.05 for P provide a good fit. For RMSEA, values below 0.1 show an acceptable model fit, while values below 0.8 indicate an excellent model fit. For the other indices, values higher than 0.95 indicate an excellent model fit, while values higher than 0.90 show an acceptable model fit.

4. Results

Table 3 shows the descriptive findings from the test “Gameplay-Scale”, the normality of the data was determined through the Kolgomorov–Smirnov test. After following expert recommendations [38,39], none of the variables was removed (Table 3).

Table 3.

Descriptive of “Gameplay-Scale”.

The psychometric properties of the 12 Gameplay-Scale items are shown in Table 4. To obtain the results, the FACTOR Analysis program proposed by Lorenzo-Seva and Ferrando [37] was used. The KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test) was 0.89, Bartlett index (1112.6 (df = 66; p < 0.001)), both values indicated a good fit for factor analysis. Three factors were rotated, obtaining a 63.03% variance. Likewise, the indexes show a GFI of 1.00, CFI of 0.97, AGFI of 0.99, and the RMSR of 0.029. All these data establish a very good fit for the analyzed data.

Table 4.

Rotated Factor Matrix and Load Factor Dimensions of Gameplay-Scale.

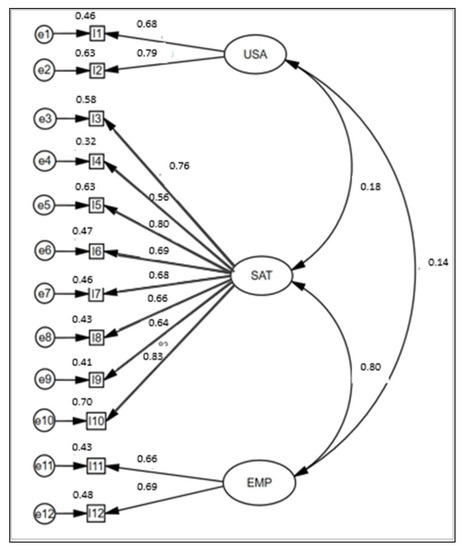

To establish the relationships between the three factors (usability, satisfaction, and empathy) a model of structural equations was made for the analysis of gameplay by children (Table 5 and Figure 2). The chi-square test was not significant at 0.05 (χ2 = 142,403; df = 51; p < 0.001), which suggests that the model fit was acceptable. Other data, such as the CFI = 0.959 and the IFI = 0.959, also indicate an acceptable adjustment, as occurred with the NFI = 0.938 and the RMSEA = 0.062. Therefore, once all the indexes were analyzed, a good adjustment of the empirical data towards the model could be made.

Table 5.

Weights and standardized regression weights.

Figure 2.

Structural equation model: Gameplay-Scale; Note: USA, Usability; SAT, Satisfaction; EMP, Empathy.

Analyzing the structural model, it was possible to observe that all items were positively associated with their dimensions, giving significant relationships at level p < 0.005. Likewise, a positive and direct relationship could be observed between all the dimensions of the developed scale. The greatest correlation strength is shown between satisfaction and empathy (r = 0.800; p < 0.005), followed by satisfaction and usability (r = 0.180; p <0.05) and the association between empathy and usability (r = 0.140; p < 0.05) (Table 5 and Figure 2).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study, which had as its main objective the analysis of the psychometric properties and structure of the Gameplay-Scale, a new questionnaire to evaluate the player’s experience during the utilization of a serious educational game was adapted and applied. The adaptation of the Gameplay-Scale has been adequate, obtaining figures that show a very good factorial adjustment, good stability, and excellent internal consistency.

In addition, these data indicated the validity of the instrument to establish and analyze the gameplay in students. Based on a sample of 237 children using an educational video game, Cronbach’s alphas were all satisfactory. This is important because the period of childhood is considered to be essential for human development and behavior as patterns of behavior followed during this stage are often repeated in adulthood. It is, therefore, a vital period for developing adaptive types of motivation towards video games [40]. Moreover, weekend video gaming was positively associated with the academic performance [41]. Children and adolescents with a greater acceptance of new technologies are more likely to experience repeated satisfaction and pleasure from their engagement and will continue to engage in the future.

Additionally, this item was used previously to demonstrate the analysis of play in people who practice sports non-professionally [35]. Video games are elements that promote intrinsic and extrinsic factors in children. In particular, they promote motivation and the strengthening of relationships within the family. Thus, the findings suggest that exergames (i.e., active-play video games) could be a potentially viable option for families, especially during bad weather in winter. Intervention efforts could benefit from promoting the social aspects of family exergaming and attitudinal factors [42]. Others have discussed how the computer game-based methods that have been analyzed made it possible to distinguish the most significant features that can promote the development of executive functions at the preschool age [43].

The three dimensions (usability, satisfaction, and empathy) load properly in the three factors of the Gameplay-Scale. The structural model developed to discover the relationships between the factors of the scale revealed positive and direct relationships between all dimensions.

The greatest strength of relationship was found between satisfaction and empathy in the same way as found by Harrington and O’Connell [34] or Hainey, Connolly, Boyle, Wilson, and Razak [44], who show how positive moods and the feeling of well-being produced by satisfying a need are associated with affective participation closer to other people’s realities. In the same way, both empathy and satisfaction were directly associated with usability. It seems that ease of use and learning in the game directly influence satisfaction and wellbeing, where it is essential to consider the level of the player to avoid negative experiences with the serious educational game in order to promote adherence to it, the degree of learning, and to avoid premature abandonment due to demotivation [34,45]).

Consequently, this study makes contributions to the literature. In this way, it is important to indicate the promotion of the level of playability of a video game in the learning and practice of it. The satisfaction that videogames bring together with autonomy and personal improvement must be the objective of educational interventions.

This is linked to what Chen, Sun, Harrington, and O’Connell [46] and Thompson [47] propose with the acquisition of adherence to videogames to generate changes in behavior through the promotion of patterns of motivation in learning processes.

The study is not without its limitations. The sample was self-selecting and the data that were utilized were collected from Spanish children. Consequently, the findings are not representative of Spanish children and may not be generalizable to other countries. For validation studies, representativeness is not a major issue, and arguably, over-sampling excessive video game players is more important. However, the present authors were unable to find a way of over-sampling, such a group in the way permission was sought to recruit participants, so this is another limitation that needs to be taken into account.

Furthermore, the scale was designed to be used in epidemiological studies rather than in a clinical context, but given the nature of the instrument, in-depth exploration using items in the scale could be used in a clinical context to get a detailed picture of the psychosocial impact of video game playing on children’s lives.

Future investigations should examine other groups. It would also be interesting to try to establish links between students who are video game players and athletes. It would also be interesting to analyze it together with educational, emotional, or psychosocial variables.

In summary, the Gameplay-Scale is a valid questionnaire for the analysis of the user experiences during the game in Spanish schoolchildren and the psychometric properties of the same are a valid instrument for children in different contexts (cultural or socioeconomic). The validated scale is an effective instrument to assess some basic dimensions in educational video games for school-age children, such as usability, satisfaction, and empathy. Specifically, it shows how ease of use and learning in the game directly influence satisfaction and wellbeing, where it is essential to consider the level of the player to avoid negative experiences with the serious game in order to favour adherence, as well as to build affective participation closer to other people’s realities.

Author Contributions

F.Z.O. and N.M.M. conceived the hypothesis of this study. F.Z.O., N.M.M. y F.L.G.V. participated in data collection. R.C.C. y F.Z.O. analysed the data. All authors contributed to data interpretation of statistical analysis N.M.M. and F.Z.O. wrote the paper with significant input from F.Z.O. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Andalusian Research Program under the project P11-TIC-7486 co-funded by FEDER, together with TIN2014-56494-C4-3-P and TEC2015-68752 from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and FEDER also.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, Y.; Rajan, P.; Sankar, C.S.; Raju, P.K. Let Them Play: The Impact of Mechanics and Dynamics of a Serious Game on Student Perceptions of Learning Engagement. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 2017, 10, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankbaar, M.E.; Richters, O.; Kalkman, C.J.; Prins, G.; Ten Cate, O.T.; Van Merrienboer, J.J.; Schuit, S.C. Comparative effectiveness of a serious game and an e-module to support patient safety knowledge and awareness. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, H.M.; Fossum, M.; Vivekananda-Schmidt, P.; Fruhling, A.; Slettebø, Å. Nursing students’ perceptions of a video-based serious game’s educational value: A pilot study. Nurs. Educ. Today 2018, 62, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.F.; Carley, S.; Tregunna, B.; Jarvis, S.; Smithies, R.; De Freitas, S.; Mackway-Jones, K. Serious gaming technology in major incident triage training: A pragmatic controlled trial. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.J.Q.; Lee, C.C.S.; Lin, P.Y.; Cooper, S.; Lau, L.S.T.; Chua, W.L.; Liaw, S.Y. Designing and evaluating the effectiveness of a serious game for safe administration of blood transfusion: A randomized controlled trial. Nurs. Educ. Today 2017, 55, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E.A.; Hainey, T.; Connolly, T.M.; Gray, G.; Earp, J.; Ott, M.; Pereira, J. An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games. Comput. Educ. 2016, 94, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granic, I.; Lobel, A.; Engels, R.C. The benefits of playing video games. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.H.; Keebler, J.R.; Chaparro, B.S. The development and validation of the game user experience satisfaction scale (GUESS). Hum. Factors 2016, 58, 1217–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijsselsteijn, W.; De Kort, Y.; Poels, K. Characterising and Measuring User Experiences in Digital Games. In Proceedings of the ACE Conference’07, Salzburg, Austria, 13–15 June 2007; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, K.; Yap, M.Y.; Ghani, M.Y.; Athreya, U.S. “Plants vs. Zombies”—Students’ Experiences with an In-House Pharmacy Serious Game. In Proceedings of the EDULEARN16, Barcelona, Spain, 4–6 July 2016; pp. 9049–9053. [Google Scholar]

- Blažič, A.J.; Cigoj, P.; Blažič, B.J. Serious game design for digital forensics training. In Proceedings of the Digital Information Processing, Data Mining, and Wireless Communications (DIPDMWC), Moscow, Russia, 6–8 July 2006; pp. 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callies, S.; Sola, N.; Beaudry, E.; Basque, J. An empirical evaluation of a serious simulation game architecture for automatic adaptation. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Games Based Learning, Steinkjer, Norway, 8–9 October 2015; pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Dorta, N.; Sanchez-Berriel, I.; Bravo, M.; Hernández, J.; Saorin, J.L.; Contero, M. Virtual Blocks: A serious game for spatial ability improvement on mobile devices. Multim. Tools Appl. 2014, 73, 1575–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, G.; Fung, S.; Mallet, L.; Posel, N.; Fleiszer, D. Learning while having fun: The use of video gaming to teach geriatric house calls to medical students. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2008, 56, 1328–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, Y.; Galletta, D. A multidimensional commitment model of volitional systems adoption and usage behavior. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2005, 22, 117–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.M.; Klein, B.D. Beyond the test of the four channel model of flow in the context of online shopping. Communic. Assoc. Informat. Systems 2009, 24, 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufaris, M. Applying the technology acceptance model and flow theory to online consumer behavior. Informat. Systems Res. 2002, 13, 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Karahanna, E. Time flies when you’re having fun: Cognitive absorption and beliefs about information technology usage. MIS Q. 2000, 24, 665–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, H.M.; Fossum, M.; Vivekananda-Schmidt, P.; Fruhling, A.; Slettebø, Å. Teaching clinical reasoning and decision-making skills to nursing students: Design, development, and usability evaluation of a serious game. Int. J. Med Inform. 2016, 94, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, S.; Ahmed, D.T. Gamification to Engage and Motivate Students to Achieve Computer Science Learning Goals. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 15–17 December 2016; pp. 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinert, R.; Heiermann, N.; Wahba, R.; Chang, D.H.; Hölscher, A.H.; Stippel, D.L. Design, realization, and first validation of an immersive web-based virtual patient simulator for training clinical decisions in surgery. J. Surg. Educ. 2015, 72, 1131–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, J.E.; Paludo, M.A.; Binder, F.V.; Reinehr, S.; Malucelli, A. Project management game 2D (PMG-2D): A serious game to assist software project managers training. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), El Paso, TX, USA, 21–24 October 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, C.; Faita, C.; Barsotti, M.; Carrozzino, M.; Tecchia, F.; Bergamasco, M. ADITHO–A Serious Game for Training and Evaluating Medical Ethics Skills. In International Conference on Entertainment Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 59–71. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer, B.G.; Singer, M.J. Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence 1998, 7, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. SUS-A quick and dirty usability scale. Usability Eval. Ind. 1996, 189, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Dudzinski, M.; Greenhill, D.; Kayyali, R.; Nabhani, S.; Philip, N.; Caton, H.; Gatsinzi, F. The design and evaluation of a multiplayer serious game for pharmacy students. In European Conference on Games Based Learning; Academic Conferences International Limited: Porto, Portugal, 2013; p. 140. [Google Scholar]

- Canals, P.C.; Font, J.F.; Minguell, M.E.; Regàs, D.C. Design and Creation of a Serious Game: Legends of Girona. In Proceedings of the ICERI2013, Seville, Spain, 18–20 November 2013; pp. 3749–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Walji, M.F. TURF: Toward a unified framework of EHR usability. J. Biomed. Inform. 2011, 44, 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boletsis, C.; McCallum, S. Smartkuber: A serious game for cognitive health screening of elderly players. Games Health J. 2016, 5, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, V.; Wyss, P.; Rampa, L.; Mitache, A.V.; Müri, R.M.; Mosimann, U.P.; Nef, T. Evaluation of a novel Serious Game based assessment tool for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.L. GEQ (game engagement/experience questionnaire): A review of two papers. Interact. Comput. 2013, 25, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockmyer, J.H.; Fox, C.M.; Curtiss, K.A.; McBroom, E.; Burkhart, K.M.; Pidruzny, J.N. The development of the Game Engagement Questionnaire: A measure of engagement in video game-playing. J. Exper. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 45, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Podlog, L.W. Examining elementary school children’s level of enjoyment of traditional tag games vs. interactive dance games. Psych. Health Med. 2014, 19, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, B.; O’Connell, M. Video games as virtual teachers: Prosocial video game use by children and adolescents from different socioeconomic groups is associated with increased empathy and prosocial behaviour. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 63, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurita-Ortega, F.; Medina-Medina, N.; Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Castro-Sánchez, M.; González-Valero, G. Validation of the “GAMEPLAY” questionnaire for the evaluation of sports activities. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2018, 13, S178–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lope, R.P.; Arcos, J.R.; Medina-Medina, N.; Paderewski, P.; Gutiérrez-Vela, F.L. Design methodology for educational games based on graphical notations: Designing Urano. Entertain. Comput. 2017, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Seva, U.; Ferrando, P.J. FACTOR: A computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behav. Res. Methods 2006, 38, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1988, 3, 424–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmider, E.; Ziegler, M.; Danay, E.; Beyer, L.; Bühner, M. Is it really robust? Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Methodology 2010, 6, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppelaars, M.; Lichtwarck-Aschoff, A.; Kleinjan, M.; Granic, I. The impact of explicit mental health messages in video games on players’ motivation and affect. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 83, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartanto, A.; Toh, W.X.; Yang, H.J. Context counts: The Different implications of weekday and weekend video gaming for academic performance in mathematics, reading, and science. Comput. Educ. 2018, 120, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Revelles, A.B.; Zurita-Ortega, F.; Castañeda-Vázquez, C.; Martínez-Martínez, A.; Padial-Ruz, R.; Chacón-Cuberos, R. Videogame rating systems, narrative review. ESHPA Educ. Sport Health Phys. Act. 2018, 2, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Veraksa, A.N.; Bukhalenkova, D.A. Computer game-based technology in the development of preschoolers’executive funtions. Russ. Psychol. J. 2017, 14, 106–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hainey, T.; Connolly, T.M.; Boyle, E.A.; Wilson, A.; Razak, A. A systematic literature review of games-based learning empirical evidence in primary education. Comput. Educ. 2016, 102, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkay, S.; Hoffman, D.; Kinzer, C.K.; Chantes, P.; Vicari, C. Toward understanding the potential of games for learning: Learning theory, game design characteristics, and situating video games in classrooms. Comput. Sch. 2014, 31, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, H.C. The effects of active videogame feedback and practicing experience on children´s physical activity intensity and enjoyment. Games Health J. 2017, 6, 200–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D. Incorporating behavioral techniques into a serious videogame for children. Games Health J. 2017, 6, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).