Abstract

The delivery of products to the end consumer has been widely considered in the e-commerce sector as new challenges to reach customers and provide them with timely and efficient delivery have surfaced. Less focus has been given to information about delivery efficiency that impacts online shoppers’ relations with e-retailers. This study’s research model builds on the extended unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT-2) by adding the critical e-commerce variables of delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, and online purchase experience (shopping satisfaction and subsequent willingness to pay). The conceptual model was tested, and samples were collected using an online survey hosted on Google Forms using e-mail in Bangladesh. The findings show that consumers’ willingness to pay is enhanced by satisfaction with online shopping and delivery efficiency. The study also contributes insights into how cost-saving efficiency affects online customer satisfaction and the intention to repurchase. Also, by applying hierarchical regression analysis, this study contributes to understanding how e-retailers can provide a functional online experience for customers. Finally, our findings offer guidelines to e-retailers regarding increasing shopping satisfaction, the intention to repurchase, and the willingness to pay more.

1. Introduction

The dramatic growth of e-retailing among customers worldwide is due to the ease of online shopping. In 2016, e-retail accounted for 8.7% of all retail sales worldwide and was estimated to be valued at $1.86 trillion USD. Sales are expected to grow to 15.5% by 2021 [1]. Consumer spending on online shopping increased from around $40 billion USD in 2013 to $70 billion USD in 2017 [2].

We chose an emerging market (i.e., Bangladesh) because, in the last five years, the development of web-based penetration and online shopping has been numerically dominant compared to traditional retail shopping, which has led to format blurring. Following buying patterns that are similar to those of other young buyers around the world, youngsters in Bangladesh are experiencing new ways of buying, which have led to the popularity and enlargement of online shopping in Bangladesh. More than a thousand e-retailers operate e-businesses using websites and social networks, primarily daraz.com, bikroy.com, and ekhanei.com [3]. The yearly turnover is over Tk 2000 crore or $236.6 million USD, and those numbers are rising every day. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) [4] report ranked developing Asian Countries (e.g., Bangladesh) low in terms of their network readiness (i.e., a country’s capability to achieve the prospects offered by information and communication technology). In 2017, there were about 2.55 million online shoppers, which is about 2% of the total population of Bangladesh [4]. According to Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) reports, in 2016, internet subscribers totaled 62.04 million users, compared to the year 2013, where there were about 35.52 million [5]. Due to rapid developments in e-commerce in Bangladesh, online shopping has been growing fast and has the potential to grow exponentially in the future as internet penetration reaches far and wide across rural areas [6,7,8]. However, the study of the UNCTAD [4] report found that the online shopping market in Bangladesh is likewise in the leading annual index ranking changing status (over 10 percent).

The consequences of delivery in light of the expansion of online shopping has been widely recognized [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Given the latest technological developments in e-retailing, this study advances our perception of delivery efficiency in Bangladesh’s online shopping setting. The packages that arrive at the distribution centers of product delivery-service providers all over Bangladesh cause huge delays for most online shoppers, and “not delivered on time” is at the top of their list of complaints [12]. A major challenge for e-retailers is retaining customers who can easily switch to other e-retailers if delivery is delayed. This problem was recently highlighted by references [12,16], who cited the need to understand the dimensions of the e-fulfillment process and its influence on customers’ e-retailing.

Our research adopts and extends a model based on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT-2) and uses it as a theoretical guide to examine how value (cost-saving efficiency), experience (online purchase experience), and delivery efficiency influence the intention to repurchase. The UTAUT has been identified as an comprehensive model that overcomes the limitations of the technology acceptance models (TAMs) [17]. The UTAUT [18] integrates eight theories and models that have been developed by innovation adoption paradigm, along with information systems such as the theory of diffusion of innovations [19], which investigates the characteristics of innovations that influence the adoption of a certain technology; the theory of reasoned action (TRA), which posits that behavior intent is human behaviors’ main predictor [20]; the technology acceptance model (TAM), which addresses information technology acceptance and its use in organizations [21]; the theory of planned behavior (TPB), which adds variables regarding internal control of the shopper (perceived behavior control) [22]; the model of personal computer utilization (MPCU) [23]; the decomposed theory and planned behavior (DTPB) [24] and socio-cognitive theory (SCT) [25], which address the result expectations performance and personal anxiety effect; and [26] employed the motivational model, which they used to explain user behavior.

This study examines how price value (cost-saving efficiency), experience (online purchase experience), and delivery efficiency influence the intention to repurchase. This study integrates delivery efficiency into the UTAUT-2 model as an antecedent of customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions because efficient delivery is an essential factor in the success of e-commerce firms [12]. Delivery efficiency can improve customers’ online shopping purchase intentions and make online shopping more enjoyable as customers anticipate the imminent arrival of their purchases. Cost-saving is also considered an important factor in online shopping [27,28,29]. Many studies have incorporated factors that relate to costs to explain consumer behavior [30,31,32,33]. Cost-saving is considered to be an essential factor in online shopping [27,28,29]. Therefore, the proposed model includes cost-saving efficiency. Finally, we adopt the construct “experience,” which is restructured as online purchase experience. The importance of the online shopping experience to the expansion of online shopping has been well recognized [34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Given the most recent technological improvements in e-retailing, these three antecedents advance our understanding of the online purchase experience in the online shopping context.

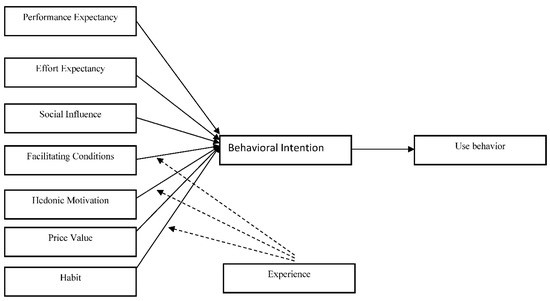

Few of the technological adoption models, and especially UTAUT-2, have been widely investigated in developing countries, including Asian countries in general and Bangladesh in particular (Figure 1). To the best of our knowledge, no single study has considered the relationships between these three antecedents (delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, online purchase experience) and the two outcome variables (intention to repurchase and willingness to pay) in a Bangladesh online market context. Also, few studies have highlighted the significance of investigating the success of online shopping based on shopper satisfaction in the UTAUT-2 model context [40]. This research addresses this gap by extending the UTAUT-2 model along three dimensions of online shopping satisfaction and two outcome variables.

Figure 1.

Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT-2).

The main question in this research concerns how shoppers’ perceptions about online delivery efficiency influence their satisfaction and, eventually, their repurchase intention and willingness to pay when they purchase online. In addressing this question, we build numerous contributions toward the literature that both insert new knowledge and extend existing knowledge [14] by developing and examining a fresh model of online shopping satisfaction that is not currently found in the literature. The conceptual model includes constructs that reflect delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, online purchase experience, online shopping satisfaction, intention to repurchase, and willingness to pay. We collected data for this study from 210 online shoppers in Bangladesh using the convenient method and used hierarchical regression analysis to analyze the data and test the hypotheses. The empirical results in general support our framework and hypotheses.

The rest of the study is organized as follows: Next, we present the conceptual framework and develop the hypotheses. Then, we discuss the research method. In the next section, we report the results of data analysis, followed by the results of hypotheses analyses. Finally, we discuss the findings in terms of theoretical and managerial contributions, limitations of research, and directions for future research.

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

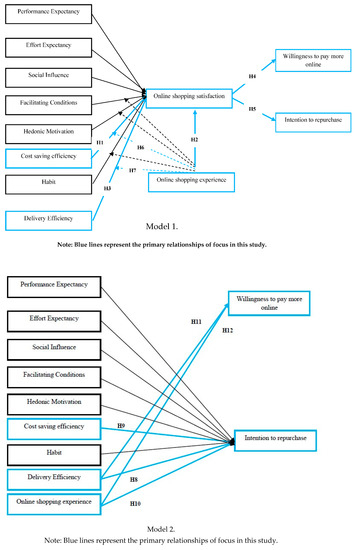

Figure 2 presents the conceptual framework that guides our research efforts. This framework concerns how the mechanisms of delivery efficiency, price-saving efficiency, and online shopping experience affect online shopping satisfaction through a willingness to pay more and intention to repurchase. We posit that customer satisfaction mediates the effect of delivery efficiency and cost-saving efficiency on these two outcomes and that online shopping experience and cost efficiency have direct effects on intention to repurchase.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model and hypotheses.

2.1. Cost-Saving Efficiency Online Shopping Satisfaction

Several studies also investigate the effects of cost-saving efficiency on online shopping satisfaction and behavioral intention, concepts that are related to price sensitivity, price-saving orientation, and price value, [29,46,47,48,49,50,51]. We assumed the positive effect of cost-saving efficiency on online customer satisfaction based on transaction cost theory (TCT), which has been used widely in the study of customer-seller relationships [46,52]. TCT’s focal inference is the illumination of the relationship between shopper satisfaction and consumers’ sensitivity to cost. Scholars have suggested that online shopping heightens shoppers’ tendency to look for better deals from numerous e-retailers [51,53]. In addition, customers can locate the specific product/service that fulfills their desires at a traditional shop and then search online to buy it at a better price [54]. Akroush [55] reported that the advantage of online stores over offline stores is that the former can offer lower prices and save customers time by making shopping more convenient. Venkatesh [48] incorporated the price value (cost-saving efficiency) construct for a technology whose use involves a monetary cost for the customer into the UTAUT-2. The influence of price value (cost-saving efficiency) on behavioral intentions was confirmed through the UTAUT-2 model [32,48]. Evidence has also suggested that a price-saving orientation positively influences customers’ behavioral intentions [49]. Following [56], we propose that cost-saving efficiency (or cost benefits) increases online shopping satisfaction (H1), and cost-saving efficiency (or cost benefits) increases customer intention to repurchase in the context of online shopping (H9).

2.2. Online Shopping Experience Online Customer Satisfaction

Several behavioral outcomes of the online shopping experience have been recognized in past studies, including customer satisfaction, e-loyalty, trust, intention to repurchase, share of wallet, and e-word-of-mouth (e-WOM) [11,39,40,41,44,45,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Customers’ shopping experience has been considered to cause positive emotions [62], but some scholars have found that customers with no online shopping experience tend to see online shopping as risky because of the potential for leaked personal information and unauthorized credit card use [63,64]. Although Khalifa [64] showed that online shopping experience has a direct and positive link with customer satisfaction, other scholars have found that previous online shopping experience does not affect the link between shopper satisfaction and behavioral intentions [44]. Besides, Srivastava [35] indicated in their research that online shopping experience has a negative effect on the share of wallet. It is reasonable to expect that online customers who have had a good online purchase experience with a particular online store would spend a larger share of wallet in that online store than in other stores. We propose, then, that online shopping experience has a direct effect on online customer satisfaction (H2), online shopping experience has a direct effect on online customer intention to repurchase in the context of online shopping (H10), and online shopping experience has a direct effect on customer willingness to pay in the context of online shopping (H12).

2.3. Delivery Efficiency Online Customer Satisfaction

The importance of delivery efficiency is growing with the increase in online shopping [10]. In the online shopping context, delivery time refers to the time between order placement and delivery [65,66]. On-time delivery is considered one of the most important elements leading to success in the e-commerce market [15,67]. The outcome benefits that result from delivery efficiency include customer satisfaction, e-trust, e-loyalty, repurchase intention, value perceptions, and willingness to pay more [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Late arrival and a long wait time significantly increase customer dissatisfaction [68,69,70]. In additionally, speedy and uneventful delivery add to the value of online shopping [41]. Extant studies have pointed out that efficient delivery positively influences customer satisfaction [11]. We propose that delivery efficiency positively increase online customer satisfaction (H3); delivery efficiency positively increases online customer intention to repurchase in the context of online shopping (H8), and delivery efficiency positively increase customer willingness to pay in the context of online shopping (H11).

2.4. Online Customer Satisfaction Willingness to Pay More (WTPM)

The proposed conceptual model posits that customers’ willingness to pay more is a direct consequence of online customer satisfaction. We also explore numerous possible indirect antecedents of willingness to pay, including delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, and online shopping experience, and analyze these three indirect antecedents with the findings of empirical research using structural equation modeling (SEM). Several existing studies have examined the effect of consumer satisfaction on WTPM [71,72,73], which refers to the maximum amount of money a consumer is willing to spend on service or product [74,75,76]. Pham [73] revealed that shoppers are not WTPM, even when they are satisfied with an e-retailer, in their earlier shopping. However, [77] found that trustworthy shoppers have low-cost elasticities and are WTP a premium to continue shopping with their desired e-retailers rather than to incur additional search costs. Lopes [71] found empirical evidence for the positive effect of expected benefits on WTPM. Also, Srinivasan [78] found evidence of a positive effect on customer satisfaction on WTPM. Online customer satisfaction is a key motivator of willingness to pay on online shopping platforms [73]. Based on this discussion, we propose that customer satisfaction positively influences the WTPM in the context of online shopping (H4).

2.5. Online Customer Satisfaction Intention to Repurchase

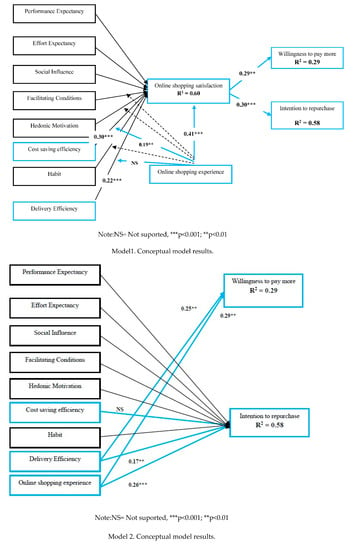

Figure 3 illustrates the importance of repeat purchases to online retailers. O. Pappas [40] incorporated the outcome variable “intention to repurchase” and found evidence of linkage among satisfaction and intention to repurchase through the UTAUT-2 model. We incorporate the latter as the dependent variable in our conceptual framework. Consumer satisfaction is a key driver of loyalty within the retail perspective [52] and is considered an antecedent of repurchase-intention [14,42,44,61,79,80,81]. Nevertheless, little research has examined the influence of consumer satisfaction on repurchase intention in the online context [13,14,59,82,83,84]. We seek to determine whether online consumer satisfaction has a direct effect on the intention to repurchase, so we follow the model examined by [42], in which online customer satisfaction and repurchase intention (H5).

Figure 3.

Conceptual model with parameter estimates.

2.6. The Moderating Role of Online Shopping Experience

In general, quality experience with an online platform creates constructive attitudes, increases customer satisfaction, and influences the intention to repurchase [40]. Tsao [39] found that online experience interaction affects e-service quality on perceived value, and Khalifa [61] showed that online shopping experience moderates the link between satisfaction and repurchase intention. Highly experienced shoppers are more confident about their judgments than less experienced online shoppers [85]. In both online and offline retail environments, one’s online buying experience impacts customer satisfaction [86,87]. These arguments reflect the online shopping experience as an important moderator because of its effect on future online shopping. Such conditions emphasize the importance of OSS analyzing the moderation effect of experience with online shopping. Based on this discussion, we propose that online shopping experience positively moderates the relationship between price saving efficiency and online shopping satisfaction (H6) and online shopping experience moderates the relationship between delivery efficiency and online shopping satisfaction (H7). In Table 1 summarizes the relationships proposed in the literature that have been used to create hypotheses in the current investigation.

Table 1.

Summary of the relationships hypothesized.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sampling and Data Collection

The sample was dispersed using a convenient method, with the help of individuals that shared the survey with their contracts. Samples were collected using two methods: (1) The data were collected using an online survey hosted on Google Forums (Google Docs, Facebook, and so on) via e-mail. (2) Samples were distributed directly to respondents. Respondents were asked to participate voluntarily, and no reward for participating was promised. The sample was made up of online shoppers in Bangladesh. At the beginning of the survey, a filter question was presented regarding the respondents’ online shopping habits, i.e., “Have you ever shopped online?” Those with “no” answers were dropped.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

The total usable sample size for the active online shopper survey was 210. The sample was relatively balanced in terms of gender (44.3% were females, and 55.7% were males). Half of the participants had a high school or bachelor’s degree. Professionally, 58 percent were students, and 42 percent were employed on behalf of others. Almost 43% of the responses said to shop online up to three times per year and about 26% between four and six times. The majority of the respondents (87%) between 21 and 30 years of age. In terms of income, 122 (58%) of consumers earned up to $800 USD/month, and 88 (42%) earned over $800 USD/month. The respondents are located in the major cities of Dhaka, where online shopping is more prevalent than it is in smaller towns. These cities have dense clusters of e-commerce firms, so it is possible to observe the effect of online shopping on the association among customer satisfaction and purchase intentions. The questionnaire was posted in December 2018 and remained open for five weeks. After the data were cleaned, 210 surveys remained that were usable for this study, which is reliable with sample-size necessities for hierarchical regression analysis assessments [89]. The questionnaire contained two main parts. The first part included demographic information (e.g., gender, age, income, expenses, and occupation), while the second part included all item scales for the constructs in the conceptual model.

3.3. Testing Normal Distribution and Common Method Bias (CMB)

The distribution test was conducted based on the kurtosis, and skewness is the value of each item (Table 2). The kurtosis and skewness values were in the range of (−1, 1), respectively, which is considered a similarity with the normal distribution [90,91]. Harman’s one-factor test was conducted to examine the effect of common method bias (CMB). To test for nonresponse bias [92], we compared early versus late respondents [93] using a t-test and found no evidence of any difference (p > 0.05) between the late and the early responses. Subsequent to the guidelines suggested by Podsakoff [94], statistical findings show that CMB is not a serious concern in this study.

Table 2.

Normality and common method bias (CMB).

4. Data Analysis Procedures

We used a three-stage procedure to accurate for endogeneity and employed regression-analysis (STATA version15) to test the conceptual model.

4.1. Questionnaire and Measure

We adopted all of the survey items from prior studies. A few items were modified slightly to reflect the online shopping viewpoint of customers in Bangladesh. As the respondents were citizens of Bangladesh and the original questionaries were formulated in English, a Bangla version of the questionaries was developed to increase the response rate and make it easy for the respondents to understand the survey. Thirty-one items were generated and were reviewed for face validity by two professors from two universities located in China and Portugal, who recommended removing three items, leaving a modified survey questionnaire with 28 items. Before the diffusion of the survey, it was conducted on 20 Bagladeshies on a random basis. Usually, the respondents specified that the questionnaire is understandable and that it just needs less than 15 min to complete. For itself, face validity was attained. We first developed the questionnaire in English before using a translation/back-translation procedure to ensure equivalence [95,96].

4.1.1. Cost-Saving Efficiency

Following references [29,49], we used the following four items to measure cost-saving efficiency: “I can save money by using the prices of different online retailers,” “I like to search for cheap product deals on different online retailers’ websites,” “Online retailers offer better value for my money,” and “Overall, I am happy with online retailers’ prices.” Participants indicated their level of agreement with the four statements using a seven-point scale. The loadings for measures were 0.77, 0.74, 0.81, and 0.80, respectively.

4.1.2. Online Purchase Experience

We used five statements from references [35,97] to measure online purchase experience: “I have a great deal of experience with online shopping,” “I have been exposed to online shopping frequently in the past,” “I am familiar with the different possibilities to use online purchasing,” “I frequently update my knowledge about the functionalities of online purchasing,” and “I am very confident in using online shopping.” Agreement with these five items was measured on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The average response to the measures’ Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.82.

4.1.3. Delivery Efficiency

Five items for delivery efficiency were adopted from [11,14,66] and used a seven-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree: “I often receive my product within the expected time period,” “I am used to the product is being delivered based on an agreed time,” “I often receive free/discounted delivery,” “I would be able to know my order status at any time,” and “Overall, I feel that online stores process my order quickly.” The loadings for the measures were 0.75, 0.76, 0.83, 0.78, and 0.84, respectively.

4.1.4. Online Customer Satisfaction

The study adopted four online customer satisfaction measures from [61,98]: “I am satisfied with my previous online shopping experience,” “I am satisfied with the pre-purchase experience with this online retailer,” “I am satisfied with the purchase experience with this online retailer,” and “I am satisfied with the post-purchase experience with this online retailer.” The Cronbach’s alpha for the average of participants’ responses to the measures was (α) = 0.85.

4.1.5. Intention to Repurchase

Following references [99,100,101], we used five items to measure intention to repurchase: “I will continue online shopping in the future,” “I will regularly use online shopping in the future,” “I intend to continue online shopping in the future,” “I intend to recommend the online shopping site that I regularly use to people around me,” and I intend to obtain product details from the online shopping web-page that I frequently use. The five statements were measured using a seven-point scale. The loadings for the measure were 0.80, 0.82, 0.76, 0.82, and 0.82, respectively.

4.1.6. Willingness to Pay More

The three items for willingness to pay, adopted from references [78,102], used a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree): “I do not pay more to make sure a product is delivered on time,” “I would continue to buy from this website if its prices increase somewhat,” and “I would pay a bit more at this website instead of buying from another website that offers the same benefit.” We developed two new scales for willingness to pay more: “I do not pay more to make sure goods are transported to the right place” and “I do not pay more to make sure the product is not fake.” Cronbach’s alpha of the average of participants’ responses to the measures (α) = 0.89.

5. Validation of Measures

To evaluate the measurement model (construct validity) and item loadings (Table 3), we assessed composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) [103] guidelines, which indicate that loadings larger than 0.7 are acceptable, and all of our constructs exceeded this threshold. As for construct reliability, constructs must have a CR between 0.70 and 0.90 [104,105]. The CR of all constructs ranged between 0.864 and 0.920, so all exceeded the desired 0.70 thresholds. The AVE for all constructs ranged between 0.586 and 0.698, so all met the minimum AVE of 0.50 [106]. Therefore, the convergent validity of all measures was assured (Table 3). To verify the discriminant validity between the constructs, the square root of the AVE must be higher than the cross-construct correlations. We used the criterion from reference [107] for discriminant validity. Table 4 shows the square roots of the AVE and the correlations between the constructs, which indicated an acceptable level of discriminant validity.

Table 3.

Construct measures and reliability index.

Table 4.

Construct measures descriptive statistics.

6. Hypotheses Testing

We tested our hypotheses using a three-stage hierarchical regression model [108,109]. The results are reported in Table 5. First, we added each of the control variables (CV) to the research model. Then, we included the three correlation variables to test H1, H2, and H3. Finally, we added the mediation term online shopping satisfaction to test H4 and H5. We used repurchase intention and willingness to pay as the dependent variable (DV), regressing it on the CVs. Then, we used online shopping satisfaction as the independent variable. The results show a good overall fit for this model. For Model 1, R2 = 0.5871, RMSE = 0.6591, and overall F = 38.15 (p < 0.001). Model 2 (Table 5) indicated a significant relationship among the three independent variables with intention to repurchase’s R2 = 0.5502, RMSE = 0.6006, and F = 29.41. The results for Model 3 (Table 5) showed a high level of model fit (RMSE = 0.9469, R2 = 0.2940 and F = 10.67 (p < 0.001)).

Table 5.

Regression results.

The empirical results shown in Table 5 indicate that the associations overall have positive signs, providing support for the theoretically derived relationships between latent variables. H1 proposes that cost-saving efficiency is positively related to online shopping satisfaction, an argument that was supported by our sample (β = 0.2924, T = 4.01, p < 0.000). These findings provide support for the view that cost-saving efficiency increases customers’ shopping satisfaction. Consistent with H2, the positive effect of online shopping experience on online shopping satisfaction is strong for online purchases (β = 0.4113, T = 5.71, p < 0.000). These results indicate that online shopping experience is a strong driver of online shopping satisfaction. H3 proposes that delivery efficiency is positively related to customer shopping satisfaction (β = 0.2170, T = 3.44, p < 0.001). In other words, delivery efficiency increases shoppers’ satisfaction with online shopping. These outcomes suggest that delivery efficiency is a driver of success in the e-commerce business. We also proposed significant effects of online shopping satisfaction on repurchase intention (H4) (β = 0.2974, T = 4.63, p < 0.000) and significant effects of online shopping satisfaction on WTPM (H5) (β = 0.2849, T = 2.81 p < 0.005). Hypotheses 4 and 5 receive support. The theoretical derivation of H4 is confirmed by these results, which reflect that online shopping satisfaction increases repurchase intention. Finally, the result for H5 also supports our argument that online shopping satisfaction increases WTPM.

Figure 3 shows that online experience has a significant effect on the association between price saving efficiency and online shopping satisfaction (β =0.19, p < 0.01), so H6 is also supported, while the online experience has an insignificant effect on the link between delivery efficiency and online shopping satisfaction (β = 0.04), so H7 is not supported.

As Table 5, Figure 3 shows that delivery efficiency, and online experience significantly and positively influence on intention to repurchase (β = 0.17, p < 0.01; β = 0.26, p < 0.001). These results support H8 and H10. In addition, online shopping experience and delivery efficiency significantly and positively affect the willingness to pay more (β = 0.25, p < 0.01; β = 0.29, p < 0.01). These outcomes support H11 and H12. Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 summarize the key results of this study.

Table 6.

Results of hypotheses testing.

Table 7.

Moderating effect on the regression coefficient.

Table 8.

Direct effect on the regression coefficient without the mediator.

7. Testing of an Alternative Model

Alternative theoretically validated models were also tested during the data analysis. We tested the direct relationships of delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, online purchase experience on WTPM, and intention to repurchase. The estimation result of this modified conceptual model showed the satisfactory goodness of fit with p < 0.001. A weak, insignificant link was found between cost-saving efficiency and intention to repurchase (β = 0.0470, p = 0.497), and the direct influence of cost-saving efficiency on WTPM was negative and significant (β = −0.1847, p = 0.092, p < 0.1). A direct significant link was found between delivery efficiency (β = 0.1687, p < 0.01) and online purchase experience (β = 0.2604, p < 0.001) with intention to repurchase (R2 = 0.5502). Finally, we tested, without a mediator (online shopping satisfaction), the direct link between delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, and online purchase experience with a willingness to pay. Our results suggest that these three antecedents directly influence customers’ WTPM when they purchase online. More specifically, delivery efficiency was found to have a strong relationship with the WTPM (β = 0.2473, p < 0.01). An explanation for this result may be that customers will pay more if e-retailers promise delivery to the right place at the right time. On balance, our empirical evidence shows that our conceptual proposed model outperforms the alternative model (Table 5).

8. Discussion and Conclusions

The study has developed and tested a successful model for an online shopping context, through the expanded and extended UTAUT-2—the empirical results, based on a sample of 210 online shoppers in Bangladesh. The findings strongly support the suitability of the extended and expanded UTAUT-2 as a means for guiding the understanding of the factors that are involved in the effects of e-customers’ satisfaction and willingness to pay in online shopping. Our research fills significant gaps in the literature by providing empirical support for the important effect of online shopping satisfaction on willingness to pay more and more importantly, by exploring the moderating effect of online experience (OE) on the relationships of delivery efficiency and cost-saving efficiency (CSE) with customer satisfaction. In particular, we found that OE moderates the relationship of CSE with customer satisfaction. In addition, we found that OE has a significant negative effect on the relationship between DE and customer satisfaction. In general, these findings propose a refined picture of how OE acts as a moderator on the e-shopping behavior model.

Although the importance of e-commerce in Bangladesh has been widely acknowledged, little empirical research in literature has documented its effect on customer behavior in Bangladesh. Some studies have narrowly investigated the link between online shopping satisfaction and WTPM [71,72,73], while our study explored differences the effect of delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, and online purchase experience on online shopping satisfaction, repurchase intention, and willingness to pay in the virtual environment by spotlighting the key relationships of the online shopping model. Our findings suggest that delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, and online purchase experience are stronger drivers on online shopping satisfaction in the virtual environment. Also, we argued that online shopping satisfaction highly influences repurchase intention [13,14,59,82,83,84]. The findings reveal that online shopping satisfaction increases repurchase intentions and that customer satisfaction is a critical element in driving repurchases intention in online purchases. This result is consistent with the prior studies on UTAUT-2 [40].

Previous studies have also largely ignored the relationship between delivery efficiency and WTPM in the context of online shopping. Relationships have previously been found between delivery efficiency and the four outcome variables of repurchase intention, customer satisfaction, e-loyalty, and value perceptions [11,13,14,15]. This study finds a new link between delivery efficiency and willingness to pay more, as delivery efficiency directly influences willingness to pay more (0.2473, p < 0.01). The study also offers empirical reinforcement for a conceptual model of online shopping satisfaction that has not been addressed in the literature and evidence of the association between online purchase experience and willingness to pay more. This is a novelty in UTAUT-2, and one of the contributions of this research. These results confirm the need to extend UTAUT-2 by incorporating the delivery efficiency factor to better understand the consumers’ pay more for efficient delivery of the online shopping market according to the research model. The study provides evidence that online purchase experience is a strong driver of willingness to pay (0.2566, p < 0.05).

This study also makes new contributions to our understanding of cost-saving efficiency. Relationships have been found previously between the two outcome variables of cost savings efficiency—online purchase and behavioral intention—but the present study reveals that cost-savings efficiency not directly influences intention to repurchase (0.0470, p = 0.497). The next contribution to new knowledge is the proof for the earlier unidentified antecedent online shopping experience and its moderating effect. The results reveal that online shopping experiences a moderating effect on the link between price saving efficiency and shopping satisfaction. We suggest that experience influence shopper feelings of control by enabling shoppers and giving them self-confidence in their online purchase choices. Nevertheless, we discover that online shopping experience has a more significant impact indicating that regardless of progress in technology, that empowers shoppers to feel more confident, making it easy to shop online.

The extended unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT-2), an extension of UTAUT, is one of the most successful theories for examining the behavioral intention to use technology [110]. This current study examines the drivers of online purchasing behavior. Willingness to pay and intention to repurchase is considered an application of the “behavioral intention” concept in online shopping. The present research uses UTAUT-2 to investigate the relationships among CSE, DE, customer satisfaction, intention to repurchase, and WTPM. The new version of UTAUT-2 has been extended by adding two new variables, delivery efficiency and willingness to pay more. This study adopts the construct “price value,” from UTAUT-2, which is restructured as “cost-saving efficiency” or CSE. This has resulted in variances of WTPM (R2 = 0.29) and an intention to repurchase (R2 = 0.58), being significant enhanced compared to previous study on UTAUT-2 in the online shopping context [32,33,40,111,112]. Overall, our study confirmed the important roles of delivery efficiency, cost-saving efficiency, and shopping experience in influencing online shopping and in UTAUT-2.

8.1. Managerial Contribution

Our research adopts and extends a model supported on UTAUT-2 and uses it as a theoretical guide to inspecting how cost-saving efficiency, online purchase experience, and delivery efficiency influence the intention to repurchase and willingness to pay more (WTPM). This study integrates delivery efficiency into the UTAUT-2 model as an antecedent of customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions (i.e., WTPM) because efficient delivery is an essential factor in e-commerce firms’ success [12]. Our findings have significant implications that merit managerial attention. While retailers invest heavily in operating e-commerce businesses, they are often left to wonder how to coordinate and manage customers’ sensitivities and behaviors in the online environment [51,113]. We argue that the lack of knowledge about what drives online shopping satisfaction, repurchase intention, and willingness to pay across the online channel can hamper retailers’ marketing strategies and influence their businesses’ ability to survive. This study provides evidence for how these retailers can enhance e-business in Bangladesh online market.

First, delivery time is an elemental antecedent of online shopping satisfaction for Bangladeshi online shoppers. Customers want their product to be delivered before a particular day (e.g., an anniversary or birthday), and if it is not delivered on time, they become anxious about its whereabouts. Therefore, e-retailers need to pay attention to this important concern by considering more effective and efficient ways to deliver items to customers. Our findings propose that Bangladeshi e-retailers should select local delivery service providers, along with high levels of flexibility. The local delivery services recruit staff that are familiar with local area, and they also have significance experience in the local market [12]. These efforts can help retailers ensure on-time delivery and attract more Bangladeshi e-shoppers.

Second, customers’ cost-saving efficiency online is significantly higher than it is in brick-and-mortar stores. Price is one of the most vital criteria that influence purchases when retailers extend their channels from off-line to online. E-retailers can increase customers’ price thresholds through marketing activities, which may increase customers’ range of acceptable prices and reduce the behavior of constantly searching for more information because of price discrepancies.

Third, online shoppers can become even more cognitively immersed in the online shopping experience as they do in a store. Therefore, e-retailers should explore the differences of this mindset and the extent and implications of immersion. For experienced online shoppers, e-retailers should spotlight providing appropriate mechanisms that increase the performance of the online shopping medium. When addressing inexperienced customers, e-retailers should invest in increasing the ease of use and user-friendliness of the online shopping medium. It may also be worthwhile to emphasize information accessibility and content richness, such as by providing tutorial videos and comparisons on the product page to facilitate memory retention and recall [51,114]. Finally, our findings send a strong signal that spotlighting on satisfaction in the online shopping context is critical because of the strong link between shopping satisfaction and WTPM.

8.2. Limitations and Opportunities for Future Research Directions

We cannot afford foldaway in all possible directions in this research, and as such, this study unsurprisingly struggles from certain limitations, some of which suggest the need for future research. This limitation is common to all former studies using the UTAUT-2 model [33,111,112,115].

First, although Bangladesh provides an appropriate research context for this study, we obtained data from only 210 valid online shoppers. This limited sample might have reduced the sample’s statistical power and limited the findings’ significance. Future research could test our hypotheses using a larger sample. Second, the relationships in the online shopping model may vary for customer from other countries. Conducting cross-cultural studies could be a fruitful avenue for future research to address this concern. Third, there is a lack of prior research on UTAUT-2 concerning the online shopping context and its dimensions in general and in the Bangladeshi online market in particular. Fourth, we spotlighted the shopping experience as the interaction effect in this research. Future research can identify more consequential moderators (e.g., social influence and internet use), which could help increase the applicability of UTAUT-2 to a broader range of consumers’ technology use contexts.

Finally, the study developed a conceptual framework of online shopping satisfaction by exploring its effects on the intention to repurchase and willingness to pay. While online shopping models consistently use intention to repurchase as an outcome variable, we contribute to the theory (UTAUT-2) by expanding the scope of knowledge regarding the effect of online shopping satisfaction on the willingness to pay. Our findings provide evidence that customer satisfaction with the online shopping experience has a significant influence on their willingness to pay. Therefore, several questions deserve further investigation. Does adopting the “willingness to pay strategy” really improve local e-retailers’ performance in emerging countries, especially in Bangladesh? Which types of local companies in Bangladesh can use this strategy appropriately? How do other firms in developing countries or in Bangladesh deal with this problem? What are the results of their efforts? It may also be useful to investigate the potential role of the online channel in determining how well the intention to repurchase converts into actual future purchases.

Author Contributions

S.K.S. contributed to the research design, empirical analysis, and manuscript writing; G.Z. provided guidance and quality assurance for the research; S.L. conducted the data analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China General program (grant number 71472149) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China key Program (grant number 71132005). This work is also supported by Xi’an Jiaotong University, China.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- EMarketer’s Worldwide Retail and Ecommerce Sales: eMarketer’s Updated Forecast and New Mcommerce Estimates for 2016—2021-eMarketer. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/Report/Worldwide-Retail-Ecommerce-Sales-eMarketers-Updated-Forecast-New-Mcommerce-Estimates-20162021/2002182 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Ramkumar, B.; Ellie Jin, B. Examining pre-purchase intention and post-purchase consequences of international online outshopping (IOO): The moderating effect of E-tailer’s country image. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 49, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slap, V. Online Shopping Getting Costlier for VAT slap|The Daily Star. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/bangladesh-national-budget-2019-20/news/online-shopping-getting-costlier-vat-slap-1756981 (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- UNCTAD Unctad B2C E-Commerce Index 2017. 2017, p. 30. Available online: http://unctad.org/en/ (accessed on 2 January 2020).

- Rahman, M.A.; Islam, M.A.; Esha, B.H.; Sultana, N.; Chakravorty, S. Consumer buying behavior towards online shopping: An empirical study on Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mamun, M.A.; Griffiths, M.D. The association between Facebook addiction and depression: A pilot survey study among Bangladeshi students. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 271, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiquee, N.A. E-government and transformation of service delivery in developing countries. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2016, 10, 368–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.S.; Shen, L.; Hossain Talukder, M.F.; Bao, Y. Determinants of user acceptance and use of open government data (OGD): An empirical investigation in Bangladesh. Technol. Soc. 2019, 56, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, S.; Sinha, K.K. Customer satisfaction with order fulfillment in retail supply chains: Implications of product type in electronic B2C transactions. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, J.; Nemoto, T.; Browne, M. Home Delivery and the Impacts on Urban Freight Transport: A Review. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 125, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.; Chen, C.-W.; Lin, J.-Y. Female online shoppers. Internet Res. 2015, 25, 542–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YU, J.; Subramanian, N.; Ning, K.; Edwards, D. Product delivery service provider selection and customer satisfaction in the era of internet of things: A Chinese e-retailers’ perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 159, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.K.; Gajjar, H.; Shah, B.J.; Sadh, A. E-fulfillment dimensions and its influence on customers in e-tailing: A critical review. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ajjan, H.; Hong, P. Post-purchase shipping and customer service experiences in online shopping and their impact on customer satisfaction: An empirical study with comparison. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2018, 30, 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-H.; Shen, G.C.; Liang, C.-L. The effect of threshold free shipping policies on online shoppers’ willingness to pay for shipping. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakulenko, Y.; Shams, P.; Hellström, D.; Hjort, K. Service innovation in e-commerce last mile delivery: Mapping the e-customer journey. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, W.H.; Yeow, P.H.P.; Chong, S.C. User acceptance of Malaysian government multipurpose smartcard applications. Gov. Inf. Q. 2009, 26, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.C.; Benbasat, I. Development of an Instrument to Measure the Perceptions of Adopting an Information Technology Innovation. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; ISBN 9780201020892. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.L.; Higgins, C.A.; Howell, J.M. Personal Computing: Toward a Conceptual Model of Utilization. MIS Q. 2006, 15, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Assessing IT Usage: The Role of Prior Experience. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compeau, D.; Higgins, C. Development of a Measure and Initial Test. Manag. Inf. Syst. Res. Center Univ. Minesota 1995, 19, 189–211. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Warshaw, P.R. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Motivation to Use Computers in the Workplace1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 22, 1111–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, E.; Sanz, S.; Ruiz, C.; Aldás, J. Why Some Internet Users Don’t Buy Air Tickets Online. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2010; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2010; pp. 209–221. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Wang, E.T.G.; Fang, Y.-H.; Huang, H.-Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, V.C.S.; Goh, S.-K.; Rezaei, S. Consumer experiences, attitude and behavioral intention toward online food delivery (OFD) services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 35, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsu Wei, T.; Marthandan, G.; Yee-Loong Chong, A.; Ooi, K.; Arumugam, S. What drives Malaysian m-commerce adoption? An empirical analysis. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, A.Y.-L. A two-staged SEM-neural network approach for understanding and predicting the determinants of m-commerce adoption. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Online purchasing tickets for low cost carriers: An application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, I.M. Predicting the acceptance and use of information and communication technology by older adults: An empirical examination of the revised UTAUT2. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yu, C.; Liu, C.; Wei, J. Comparison of mobile shopping continuance intention between China and USA from an espoused cultural perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Kaul, D. Exploring the link between customer experience–loyalty–consumer spend. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izogo, E.E.; Jayawardhena, C. Online shopping experience in an emerging e-retailing market: Towards a conceptual model. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Nakayama, M.; Sutcliffe, N. The impact of age and shopping experiences on the classification of search, experience, and credence goods in online shopping. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2012, 10, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Wilson, A. Evolving the online customer experience … is there a role for online customer support? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 60, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, W.-C.; Hsieh, M.-T.; Lin, T.M.Y. Intensifying online loyalty! The power of website quality and the perceived value of consumer/seller relationship. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1987–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Pateli, A.G.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Moderating effects of online shopping experience on customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2014, 42, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, K.; Breugelmans, E. Buying Groceries in Brick and Click Stores: Category Allocation Decisions and the Moderating Effect of Online Buying Experience. J. Interact. Mark. 2015, 31, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S.; Clark, M.; Samouel, P.; Hair, N. Online Customer Experience in e-Retailing: An empirical model of Antecedents and Outcomes. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 308–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, N.; Yu, J.; Cheng, J.; Ning, K. Customer satisfaction and competitiveness in the Chinese E-retailing: Structural equation modeling (SEM) approach to identify the role of quality factors. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, I.-L. The antecedents of customer satisfaction and its link to complaint intentions in online shopping: An integration of justice, technology, and trust. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud Trevinal, A.; Stenger, T. Toward a conceptualization of the online shopping experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, R.M. Can Customer Satisfaction Decrease Price Sensitivity in Business-to-Business Markets? J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2005, 12, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.M. Shopping orientation and online travel shopping: The role of travel experience. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2012, 14, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Online drivers of consumer purchase of website airline tickets. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2013, 32, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.; Bösener, K. The influence of customer satisfaction on customer price behavior: Literature review and identification of research gaps. Manag. Rev. Q. 2015, 65, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Sharma, P.N.; Morgeson, F.V.; Zhang, Y. Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction: Do They Differ Across Online and Offline Purchases? J. Retail. 2019, 95, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucklin, L.P.; Sengupta, S. Organizing Successful Co-Marketing Alliances. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, H.; Popkowski Leszczyc, P.T.L.; Lin, Y. Why is Price Dispersion Higher Online than Offline? The Impact of Retailer Type and Shopping Risk on Price Dispersion. J. Retail. 2018, 94, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Spahn, S. Cross-channel free-riding consumer behavior in a multichannel environment: An investigation of shopping motives, sociodemographics and product categories. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akroush, M.N.; Al-Debei, M.M. An integrated model of factors affecting consumer attitudes towards online shopping. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2015, 21, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekettye, G.; Pinter, J. Customer satisfaction and price acceptance in the case of electricity supply. Int. J. Process Manag. Benchmarking 2006, 1, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soopramanien, D. Conflicting attitudes and scepticism towards online shopping: The role of experience. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izogo, E.E.; Jayawardhena, C. Online shopping experience in an emerging e-retailing market. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, B.B.; Wang, S.; Parish, J.T. The role of cumulative online purchasing experience in service recovery management. J. Interact. Mark. 2005, 19, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frambach, R.T.; Roest, H.C.A.; Krishnan, T.V. The impact of consumer Internet experience on channel preference and usage intentions across the different stages of the buying process. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, M.; Liu, V. Online consumer retention: Contingent effects of online shopping habit and online shopping experience. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2007, 16, 780–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagdare, S.; Jain, R. Measuring retail customer experience. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2013, 41, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, E.K.; Makienko, I. The effects of information privacy and online shopping experience in E-commerce. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2011, 15, 97. [Google Scholar]

- de Kerviler, G.; Demoulin, N.T.M.; Zidda, P. Adoption of in-store mobile payment: Are perceived risk and convenience the only drivers? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, F.; Schaupp, L.C. A Conjoint Analysis of Online Consumer Satisfaction. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2005, 6, 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, J.T.; Dewitt, W.; Keebler, J.S.; Min, S.; Nix, N.W.; Smith, C.D.; Zacharia, Z.G. Defining Supply Chain Management. J. Bus. Logist. 2001, 22, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Grant, D.B.; McKinnon, A.C.; Fernie, J. Physical distribution service quality in online retailing. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2010, 40, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, J.E.; Bienstock, C.C. Measuring Service Quality in E-Retailing. J. Serv. Res. 2006, 8, 260–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetzinger, L.; Kun Park, J.; Widdows, R. E-customers’ third party complaining and complimenting behavior. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2006, 17, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, R. The moderating roles of risk and efficiency on the relationship between logistics performance and customer loyalty in e-commerce. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2010, 46, 950–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.B.; Galletta, D.F. Consumer Perceptions and Willingness to Pay for Intrinsically Motivated Online Content. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2006, 23, 203–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhausen, D.; Binder, J.; Schoegel, M.; Herrmann, A. Integrating Bricks with Clicks: Retailer-Level and Channel-Level Outcomes of Online–Offline Channel Integration. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.S.H.; Ahammad, M.F. Antecedents and consequences of online customer satisfaction: A holistic process perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 124, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, T.A.; James, M.D. Estimating Willingness to Pay from Survey Data: An Alternative Pre-Test-Market Evaluation Procedure. J. Mark. Res. 1987, 24, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, A. Effect of Dealing Patterns on Consumer Perceptions of Deal Frequency and Willingness to Pay. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jedidi, K.; Zhang, Z.J. Augmenting Conjoint Analysis to Estimate Consumer Reservation Price. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 1350–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichheld, F.F.; Sasser, W.E. Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1990, 68, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.S.; Anderson, R.; Ponnavolu, K. Customer loyalty in e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. J. Retail. 2002, 78, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellier, P.K.; Geursen, G.M.; Carr, R.A.; Rickard, J.A. Customer repurchase intention. Eur. J. Mark. 2003, 37, 1762–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Galliers, R.D.; Shin, N.; Ryoo, J.-H.; Kim, J. Factors influencing Internet shopping value and customer repurchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, I. An Empirical Study of an Online Travel Purchase Intention Model. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; Janda, S.; Muthaly, S.K. A new understanding of satisfaction model in e-re-purchase situation. Eur. J. Mark. 2010, 44, 997–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y. Why Do Consumers Go Internet Shopping Again? Understanding the Antecedents of Repurchase Intention. J. Organ. Comput. Electron. Commer. 2012, 22, 38–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.A.D.O.; Silva, S.C. The role of consumer-cause identification and attitude in the intention to purchase cause-related products. Int. Mark. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.; Papatla, P. Relative importance of online versus offline information for Internet purchases: Product category and Internet experience effects. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, K.C.; Chai, L.T.; Piew, T.H. The Effects of Shopping Orientations, Online Trust and Prior Online Purchase Experience toward Customers’ Online Purchase Intention. Int. Bus. Res. 2010, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, K.; Campo, K.; Breugelmans, E.; Lamey, L. The Impact of the Multi-channel Retail Mix on Online Store Choice: Does Online Experience Matter? J. Retail. 2015, 91, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, P.; Costa e Silva, S.; Ferreira, M.B. How convenient is it? Delivering online shopping convenience to enhance customer satisfaction and encourage e-WOM. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 44, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, J. Guttman on Factor Analysis and Group Differences: A Comment. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1992, 27, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.; Tran, X.; Misra, S.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R.; Pham, Q.T.; Tran, X.P.; Misra, S.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R. Relationship between Convenience, Perceived Value, and Repurchase Intention in Online Shopping in Vietnam. Sustainability 2018, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P.J.; West, S.G.; Finch, J.F. The Robustness of Test Statistics to Nonnormality and Specification Error in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, D.; Seah, L.-H.; Hite, D.; Haab, T. Telephone presurveys, self-selection, and non-response bias to mail and Internet surveys in economic research. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2004, 11, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekaran, U. Methodological and Theoretical Issues and Advancements in Cross-Cultural Research. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1983, 14, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-M.; Lin, H.-Y.; Sun, S.-Y.; Hsu, M.-H. Understanding customers’ loyalty intentions towards online shopping: An integration of technology acceptance model and fairness theory. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2009, 28, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colwell, S.R.; Aung, M.; Kanetkar, V.; Holden, A.L. Toward a measure of service convenience: Multiple-item scale development and empirical test. J. Serv. Mark. 2008, 22, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-H.; Yen, C.-H.; Chiu, C.-M.; Chang, C.-M. A longitudinal investigation of continued online shopping behavior: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, Z.; Jun, M. Measuring consumer perceptions of online shopping convenience. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Balaji, M.S.; Sadeque, S.; Nguyen, B.; Melewar, T.C. Constituents and consequences of smart customer experience in retailing. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 124, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, E.; Zailani, S.; Iranmanesh, M.; Kanapathy, K. Drivers of consumers’ willingness to pay for halal logistics. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 464–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D. A Practical Guide To Factorial Validity Using PLS-Graph: Tutorial And Annotated Example. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2005, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991; ISBN 9780761907121. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, B.H.; Nickerson, J.A. Correcting for Endogeneity in Strategic Management Research. Strateg. Organ. 2003, 1, 51–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdegem, P.; De Marez, L. Rethinking determinants of ICT acceptance: Towards an integrated and comprehensive overview. Technovation 2011, 31, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palau-Saumell, R.; Forgas-Coll, S.; Sánchez-García, J.; Robres, E. User Acceptance of Mobile Apps for Restaurants: An Expanded and Extended UTAUT-2. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Sung, H.J.; Jeon, H.M. Determinants of Continuous Intention on Food Delivery Apps: Extending UTAUT2 with Information Quality. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Morgeson, F.V.; Morgan, N.A.; Mithas, S.; Fornell, C. Do managers know what their customers think and why? J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucy, E.P. Second Generation Net News: Interactivity and Information Accessibility in the Online Environment. Int. J. Media Manag. 2004, 6, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. Management Information Systems Research Center, University of Minnesota. MIS Q. 2012, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).