Abstract

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is often portrayed as a policy measure that can mitigate the environmental influence of corporate and government projects through objective, systematic, and value-free assessment. Simultaneously, however, research has also shown that the larger political context in which the EIA is embedded is crucial in determining its influence on decision-making. Moreover, particularly in the case of mega-projects, vested economic interests, rent-seeking, and politics may provide them with a momentum in which the EIA risks becoming a mere formality. To substantiate this point, the article examines the EIA of what is reportedly Asia’s largest dam outside China: the Bakun Hydro-electric Project (BHP) in Malaysia. The study is based on mixed methods, particularly, qualitative research (semi-structured interviews, participatory observation, and archival study) coupled to a survey conducted in 10 resource-poor, indigenous communities in the resettlement area. It is found that close to 90% of the respondents are dissatisfied with their participation in the EIA, while another 80% stated that the authorities had conducted the EIA without complying to the procedures. The findings do not only shed light on the manner in which the EIA was used to legitimize a project that should ultimately have been halted, but are also testimony to the way that the BHP has disenfranchised the rights of indigenous people to meaningfully participate in the EIA.

1. Introduction

Incorporating the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) into existing planning and decision-making processes is generally put forward as a means to identify potentially adverse effects of proposed (mega-) projects. The EIA can provide the information for more grounded decisions on how to proceed, and ensure the project’s environmental sustainability, economic viability, and social acceptability [1,2,3,4]. At the same time, however, research has ascertained a divergence between what is aimed for by the EIA and what is practiced and enforced [5].

Various studies have shown that the EIA can become a political tool whereby the decision to approve projects is outweighed by other reasons than technical or environmental considerations [6]. In this context, the EIA may merely serve to legitimatize decisions which, in fact, have already been taken [7,8]. In effect, the EIA exists as a symbolic token decoupled from realities on the ground, and with limited influence on the decision-making to approve, alter, or even reject projects [9,10,11,12].

This article acknowledges that improvement on certain shortcomings of the EIA could be achieved through procedural, methodological, and technical ways [13,14,15,16]. At the same time, however, it also moots that a decisive factor in the success or failure of EIA is constituted by the larger socio-political context in which it takes place. In fact, the politics and rent-seeking over EIA, by which public policies and/or economic conditions are manipulated as strategies to raise profits or personal gains, are prime factors that need reflection prior to considering its execution. Put differently, when the environment in which the EIA is embedded cannot safeguard its independence, it will be extremely difficult to conduct in an impartial manner. It needs emphasis that this presupposes that the EIA practitioner is not part and parcel of the politics and rent-seeking itself, which may not be necessarily the case [17]. To substantiate the argument, this article presents the case of the EIA of a dam, which at 205 m high, is reportedly Asia’s second largest dam: the Bakun Hydro-electric Project (BHP) in Malaysia.

The bulk of the research on the BHP has focused on its impact on energy supply [18,19], its policies on compensation [20], and its social sustainability [21]. With regard to the latter, Andre’s in-depth study [22] duly noted that social sustainability for mega-projects, such as the BHP, need to move beyond formal lists of social indicators. Instead, these should be assessed through evolutionary, qualitative, and hermeneutic approaches that enable the identification of social issues of concern. To date, however, few studies have specifically examined the EIA of the BHP, which is a lost opportunity, as the EIA was the main tool through which the Malaysian government tried to legitimize it.

The study by Memon [23] is one of the few exceptions that squarely looks into the EIA of the BHP. Although done with great care and depth, his study was carried out well over a decade before the dam went into operation. In this context, there is a need to follow-up and update Memon’s seminal study, which we aim to do in various ways: (1) by complementing an ex ante analysis of the EIA, with an ex post analysis conducted after the dam went into operation; (2) by not only shedding light on the way that the EIA was conducted, but also how it was experienced by the affected population—the indigenous Orang Ulu; (3) by not only achieving this in a qualitative way (through interviews, participatory observation, and archival study) as done by Memon, but also in a quantitative way (through a survey conducted in 10 rural communities in the resettlement area).

In this respect and to our best knowledge, the article is one of the first studies of this nature on the Bakun Dam. In addition, through the comprehensive, mixed methodology adopted here, this case might also enhance our general understanding of the dynamics and politics of the EIA around dams and other large infrastructural projects. The article is structured around a dual research question: (1) How and to which extent did politics and rent-seeking around the EIA influence project implementation? (2) How did these politics and rent-seeking, in turn, influence the views and experiences of the affected population with regard to the EIA?

Apart from the introduction, this article is divided into four main sections. In the second section, we will provide an in-depth description of: (1) the BHP’s basic features; (2) the history of the EIA in Malaysia; (3) the vested economic interests that propelled the initiation of the BHP, and; (4) the politics and rent-seeking that surrounded this mega-project’s EIA. In the third section, we will introduce the methodology, features of the survey sample and interviews, and describe the research sites in terms of their socio-economic, geographical, and demographic conditions. This is followed by the results section, where we analyze the survey data and qualitative fieldwork in terms of respondents’ views on the EIA, with particular reference to public participation, satisfaction, conflict management, and trust. In the fourth and concluding section, we discuss the empirical and theoretical implications of the case for the practice of EIA.

2. EIA of the Bakun Dam: Controversy, Conflict, and Colluding Interests

2.1. Project Features

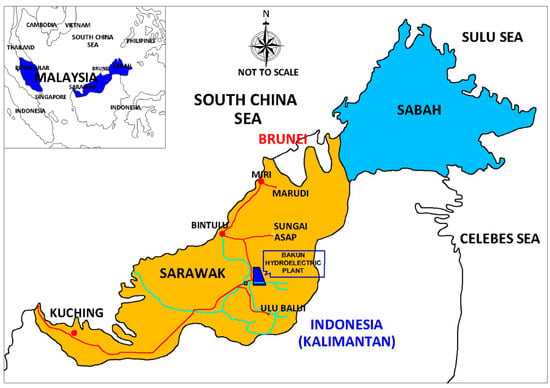

The BHP is situated in Sarawak State, also known as “Land of the Hornbills,” the biggest state within the Malaysian federation of a total of 13 states (see Figure 1). The Malaysian government initially approved the construction of the BHP in 1986, which was Asia’s first dam project of this size and level of electricity-generation capacity. At full capacity, the BHP can generate 2400 mW, while its artificially formed reservoir is the largest lake in Malaysia with a surface area of approximately 70,000 ha (roughly equal to the size of Singapore) and a storage volume of 43.8 billion m3.

Figure 1.

Location of the Bakun Hydro-electric Project. Source: Drawn by Nor-Hisham.

The dam has had a major environmental and social impact. First, it necessitated clear-cutting of around 700 km2 of virgin tropical rainforest with the consequent loss of rare and endangered plant and animal species [24,25,26]. Moreover, it has caused the forced displacement and marginalization of an estimated 10,000 people, mostly indigenous Orang Ulu. This has raised serious concerns over social sustainability [17,21]. The Orang Ulu originally inhabited the lands along the Balui River in the Belaga District, but have now been resettled at the Resettlement Scheme of Sungai Asap (hereafter: RSSA). The Orang Ulu are considered a socially vulnerable and economically disadvantaged group in Malaysia. They are mainly engaged in agriculture and the exploitation of forest-based resources including hunting and gathering, small-scale trade and retail, and traditional fishery.

From an economic perspective, the BHP has also proven problematic, more specifically with regard to the economics of energy supply [17,18]. Initially, the government of Sarawak state planned that 90% of the generated electricity would be sent via undersea cables to peninsular Malaysia, as well as neighbouring Brunei, Indonesia, and the Philippines. However, this initiative was aborted due to concerns over costs and feasibility. Today, Sarawak state is still looking for ways to sell its surplus electricity and is operating the dam below its capacity [27].

In March 2012, shortly after the federal government began a corruption investigation into the BHP, the transnational mining corporation Rio Tinto cancelled a plan for the construction of a US$2 billion aluminium smelter that would have used electricity from the BHP. Since the dam went into operation in 2011, a quarter of a century after it was approved, the total costs of the project had ballooned to RM 7.3. billion (as compared to the originally estimated costs of RM 2 billion).

2.2. History of EIA in Malaysia

Prior to 1970, the Malaysian economy was predominantly agricultural-based. There were virtually no environmental concerns due to a strong focus on economic development. Moreover, environmentalism was minimal, if not absent [28,29]. The agenda for development in Malaysia could be argued to have started through the introduction of the New Economic Policy (NEP) in 1970. During the implementation of the NEP, many large-scale development activities were carried out. Inevitably, while this effort brought about positive economic effects, it imposed pressure on environmental quality and human well-being. As asserted by Aiken [28] the rapid exploitation of natural resources and the expansion of resource-based industries resulted in environmental problems.

Parallel and contradictory to this development, Malaysia attempted to align itself closer to global environmental policies, and more particularly, the principles of the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment held in 1972 [30]. This was also due to the successful lobbying of Malaysian Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), such as the Consumers’ Association of Penang (CAP) and the Malaysian Nature Society (MNS). These cumulative factors led to the adoption of the 1974 Environmental Quality Act [31,32].

The need for an EIA in Malaysia was not felt until several natural disasters occurred, more specifically, the flood in Kuala Lumpur in 1970 and in Bota Perak in 1976, respectively. The Department of Environment (DOE) of Malaysia was asked by the World Bank to assess environmental impacts, as flooding had become a major concern [33]. The World Bank visited Malaysia in 1975 and consequently drafted a report recommending the design and formulation of EIA as policy for any major development project [33,34].

EIA has only legally been implemented in Malaysia since 1988. Prior to this, it was in operation since 1979, but without statutory provision. In the Fourth Malaysia Plan (1981–1985), the emphasis on EIA was reinforced through three-pronged strategies: pollution control, comprehensive land use planning and integrated project planning [35]. This further strengthened the role of EIA in Malaysia. During the administration of Prime Minister Mahathir, the industrialisation and urbanisation intensified. This era was marked by economic liberalisation and privatisation causing rapid expansion of the business sector.

Taking cognizance of the fact that prevention measures had failed to address the environmental problems, the Malaysian government introduced EIA through an amendment of the Environmental Quality Act in 1985 (the inclusion of “Section 34A”). The introduction of EIA has—at least in principle—brought about a new approach in environmental planning, where anyone intending to carry out a certain “prescribed activity” has to undertake a study of the environmental impacts before approval can be granted. A major litmus test of the robustness of the EIA was presented the following year when the Malaysian government formally approved the construction of the BHP.

2.3. Collusion of Interests: A Line of Events

Mohamad Mahathir, former Prime Minister of Malaysia, was a staunch proponent of the BHP. He opined that the BHP was crucial for a reliable electricity supply for the nation’s industrialisation and urbanisation. Furthermore, he argued that the socio-economic position of indigenous peoples, such as the Orang Ulu, could be improved through the resettlement scheme. In his view, the project was a catalyst for development. Within Sarawak state, the BHP was fervently championed by its Chief Minister, Taib Mahmud, who maintained:

Bakun is a huge gift from the federal government—proof of the lie of the outdated idea that the Federal Government wants to rob us of our resources and colonise us. With Bakun, Sarawak will be the powerhouse of Malaysia.[24]

Under the banners of “public interest” and development, both Mahathir and Taib criticized those who opposed the project as foreign agents, unpatriotic, or anti-modernist [36]. However, politicians’ interest in the BHP was not entirely out of public or national concerns. There was a tight collusion between political leaders and the corporate sector. A poignant example is the manner in which the project was granted to the main contractor. In 1994 the concession was awarded—without open tender—to Ekran Berhad, a company engaged in timber and property development, yet, inexperienced in dam construction. The company’s owner, Ting Pek Khiing, was widely known to have close personal connections to Mahathir, the federal Minister of Finance, and the Chief Minister of Sarawak State [24,37,38].

Ekran Berhad enjoyed substantial benefits from the BHP construction, including an estimated 4 billion tonnes of timber valued at RM one billion. In addition, the company was awarded 11,578 acres of plantation in the resettlement area. Lastly, it won a contract with a value of RM 300 million to construct the 165 km Bakun-Bintulu road connecting the BHP and the resettlement area (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bakun-Bintulu road (connecting the Bakun Hydro-electric Project (BHP) and Resettlement Scheme of Sungai Asap (RSSA)). The road is often busy with logging trucks. Source: Photograph by Nor-Hisham.

Yet, in 1997 a dispute erupted between Ekran Berhad and the Swiss-Swedish engineering contractor, Asia Brown Boveri Limited (ABB). The latter objected to a RM 9 billion contract being awarded without open tender to four companies under Ting Pek Khiing’s control [37,38]. In the wake of the 1997 Asian Economic Crisis, the federal government deferred further construction and Ekran Berhad withdrew from the project two years later. For this, it was compensated at RM one billion [24,37,39] (In 2010, Ting Pek Khiing was declared bankrupt by the Kuala Lumpur High Court because he defaulted on a loan amounting to RM 60.79 million that he had borrowed from the Bank of Commence 6 years earlier [40]).

The BHP was also strongly supported by other corporations. For one, there is the sole and largest cement producer in Sarawak: the Cahaya Mata Sarawak Berhad (CMSB). Onn Mahmud, the brother of Sarawak’s Chief Minister, Taib Mahmud, is generally assumed to direct the operations of CMSB [37,41]. Moreover, Taib Mahmud’s two sons, Sulaiman and Mahmud, had considerable interests in Pacific Chemicals, the company that was granted logging operations in the BHP project area [24]. In 2002, the entire operation over the BHP was taken over by a joint venture between Sime JV and Sinohydro of China: the Malaysia–China Hydro Joint Venture (MCHJV). Sime JV is a subsidiary of Sime Darby (a Malaysian flag conglomerate, with business roots in plantations), a so-called ‘Government Linked Company’ of which chairman and board of directors are traditionally appointed from former political leaders of Malaysia’s major political party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO) or other parties from the National Front, the coalition of which UMNO is a part. The chairman of Sime Darby is without exception appointed from previous UMNO leaders who have retired or failed to win general elections. For example, the previous Sime Darby Chairman was Musa Hitam (2007–2012), a former Deputy Prime Minister and ex-UMNO Deputy President. He was followed by Abdul-Ghani Othman (2013–2008), the former Chief Minister of Johore.

Sinohydro, Sime JV’s counterpart, is a Chinese state-owned hydroelectric and construction corporation founded in 1950. In the wake of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the corporation has entered the global market, and is now active across Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Europe. Its current portfolio includes the construction of the Rio Blanco Dam in Honduras, the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, the Hamad Port in Qatar, and the Kochav-Hayarden Hydro-Electric Station in Israel. Under the new joint venture, Sime JV obtained 70% and Sinohydro 30% of the shares. Having described the network of interests that is tied to the BHP, we will proceed to examine the procedures, rhetoric, and actual practice of the BHP’s EIA below.

2.4. The EIA between Rhetoric and Reality

The BHP was legally subject to federal EIA requirements as it involved at least one or more of the following, so-called “prescribed activities”: (i) the conversion of hill forest land to other land use covering an area of 50 ha or more; (ii) logging activities which cover an area of 500 ha or more; (iii) dam and hydroelectric power scheme projects with dams over 15 m high; and, (iv) ancillary structure installations covering a total area in excess of 40 ha and/or reservoirs with a surface area in excess of 400 ha. As such, Malaysia’s Environmental Quality act (Order 1987) ordains that:

Any person intending to carry out any of these prescribed activities shall appoint a qualified person to conduct an environmental impact assessment and to submit a report thereof to the Director-General (DG).(Section 34A (2), [42])

In April 1994, Ekran Berhad designated the Centre for Technology Transfer and Consultancy at UNIMAS, a local Sarawakian university, as the main consultant for the BHP’s EIA. Its CEO, Ting Pek Khiing, claimed that the EIA would be completed by June 1994. This tight timeframe raised questions of whether it would be rushed to completion [43]. One month later, the socio-economic impact study was carried out separately by the Sarawak State Planning Unit, a unit under the Sarawak Chief Minister’s Department, causing concerns over the study’s independency.

While the EIA was still being conducted, Ekran Berhad had already carried out preliminary construction work, and by September 1994, an earth-breaking ceremony for the BHP was officiated by its greatest proponent, Prime Minister Mahathir [24]. Markedly, the ceremony took place before the project had received Cabinet approval, and even before the EIA itself had been approved. Other groundwork followed, including land clearance, construction of the access road, and river diversion. Only by March 1995, the first EIA report (for the reservoir) obtained approval, a mere six months after submission [24]. The decision on this part of the EIA had been reached without public review and without the full EIA report being completed, despite clear legal requirements [44,45]. The three remaining parts of the EIA were then still pending.

On 20 April 1995, three indigenous representatives from the longhouses (large rural communal dwellings) of Long Bulan, Uma Daro, and Bato Kalo (now all inundated by the reservoir) filed an originating summons at the High Court in Kuala Lumpur. They claimed that the 1974 federal Environmental Quality Act had been violated, and asked to be given the right to make representation as provided for under the law [46]. However, the case did not materialize, as the project was by then delayed due to the Asian Economic Crisis and the fact that Ekran Berhad had pulled out.

According to federal regulations, the EIA process requires public participation at two distinct time points:

- The stage of conducting the EIA and the preparation of its report, when the project proponent ought to consult affected people via: (a) citizens’ committees; (b) public meetings and workshops; and, (c) soliciting public opinion [47];

- The review of the report and its approval. At this point, the EIA report compiled by the project proponent must be displayed for public inspection including by the affected people [47].

In reality, however, the affected population and civic groups who demanded access to information received no response from authorities. For example, in February 1994, a coalition of NGOs and the Democratic Action Party (DAP) urged the government to be more transparent in releasing information on the BHP. Yet, when a public forum was planned in Kuching, which was to be attended by the Finance Minister of Sarawak State, the Chair of the Bakun Development Committee, representatives of the Orang Ulu Communities and civic organizations, the event was cancelled two days before [48].

As controversy over the BHP was mounting, Prime Minister Mahathir criticised interest groups and NGOs, and maintained:

Some parties, like NGOs, oppose the EIA report merely because they want to reject it without listening to clarifications.[49]

In addition, he asserted that it was

Normal practice for the government to approve an EIA before displaying it to the public.[49]

To this, two NGOs, Sahabat Alam Malaysian and the Consumers’ Association of Penang, retorted that there was no public copy for review, even four months after the EIA had been approved [49]. After strong protests, the reports were made available another month later, and only at the DOE Headquarters in Kuala Lumpur over 1300 km away from where the affected population lived. Moreover, despite the fact that two months is the standard term for public review, the EIA reports were extremely shortly displayed: in Belaga and Kapit the report was up for inspection during a single day [24].

Under the background above, we conducted our fieldwork—including a survey, participatory observation, and semi-structured interviews—in the project area and the resettlement area of the BHP.

3. Materials and Methods: Survey and Interviews

Our analysis of the Bakun Dam’s EIA was accomplished through “mixed methods” [50,51], i.e., the use of multiple sources that include quantitative information gathered through a survey and the analysis of government and corporate statistics, as well as qualitative data gathered through interviews, participatory observation, and literature research. The survey and fieldwork have been conducted at the Resettlement Scheme of Sungai Asap (or RSSA), a new settlement area built for the displaced Orang Ulu. Preliminary data collection was done shortly after the dam started operation, in May 2011, and coupled with 21 semi-structured interviews and participatory observation. A second round of fieldwork was carried out from September until November 2012. This time, a pilot survey of fifteen households was carried out, followed by a full survey among 220 respondents from 10 “longhouses,” large communal dwellings built on stilts and generally hold up to 100 families in separate living quarters. More specifically, these were: Uma Kulit, Uma Belor, Uma Daro, Uma Nyaving, Uma Kelep, Uma Lahanan, Uma Bawang, Uma Batu Liko, Uma Balui Ukap, Uma Bakah, Uma Badeng, Uma Penan, Uma Lasong, and Uma Juman. These 10 longhouses comprised five different ethnic sub-groups, namely the Kenyah, Kayan, Lahanan, Ukit, and Penan. The total population in the RSSA was 11616 in 2012 (accounting for 2219 households) [52].

Of the total sample (Table A1, Appendix A), the majority (74.5%) was working as farmer, while logging workers accounted for 8.2%, transport workers for 5.5%, professional and clerical workers, respectively, for 2.7% and 1.4%, and other employment for 7.7%. In terms of monthly income, the majority (44.1%) earned a monthly income below RM 450.00 During the fieldwork period, the currency exchange between Malaysian Ringgit to US Dollar was around RM 0.32 to 1 US Dollar. whereas the second monthly income bracket (25.5%) earned RM 451.00–RM 700.00. Respondents who earned RM 700.00–RM1000.00 were recorded at 18.6%. Other high-income bracket categories contained few respondents. For example, those who earned a monthly income bracket of RM 1601.00–RM 1900.00 constituted 3.7% of respondents. As a comparison to the poverty line at the national level, this monthly income finding gives us an alarming trend whereby, according to Malaysia’s poverty standard for the state of Sarawak, households with a total monthly income less than RM 830.00 and RM 520.00 are considered poor and extreme (hardcore) poor respectively [53]. The monthly income also exposed that the objective of the resettlement programme for the BHP which focuses on job-oriented activities to generate higher income for the resettlers on a sustainable basis through the restructuring of the existing socio-economic activities as aimed by the Economic Planning Unit [54] is a long way from being achieved.

To achieve a higher degree of representativeness, the study employed a multi-stage cluster sampling [55,56] Clustering was made according to the ethnic sub-groups whereby about 10% of the total number of family heads of the Orang Ulu at the RSSA. In this way, the survey aimed to ensure that all the heads of the Orang Ulu households received equal opportunity to be selected as respondents. In addition, theoretical saturation was used to determine the sample size, up to the point where additional data provided no new insights into the research questions [57,58]. All surveys were executed by the main researcher without assistance from students, interpreters, or else. To prevent bias in answering the questionnaires, a household-by-household approach (one-on-one household visits) was utilized while group meetings or group discussions were intentionally avoided.

To complement and strengthen the quantitative part, a qualitative approach through semi-structured interviews was carried out with local community leaders at the RSSA. There are four categories of local leaders among the Orang Ulu: the highest is “Temenggung” followed by “Pemancar,” then “Penghulu” and lastly “Tuai Umah” (or headman). Sixteen interviews were conducted with the local village leaders of the Orang Ulu of the Village Development and Security Committee. Semi-structured interviews were also conducted with a variety of stakeholders involved in the BHP (see: List of Interviewees, Appendix A). Each of the interview sessions lasted between sixty minutes to ninety minutes.

Lastly, the research also included literature and archival research on the larger Malaysian context of dam-building, EIA, and customary land rights. For this part of the research, we relied on federal and local state reports, as well as studies by NGOs and (semi)corporate organizations, such as the dam contractors and funding agencies.

Having discussed the materials and methods of this study, the following section continues to examine how the affected indigenous people, local leaders and NGOs’ viewed the EIA. The section is structured around the following main themes: (1) the level of respondents’ participation in the EIA; (2) the extent to which procedures of the EIA were followed in a fair and open manner, and (3) the management of conflict and consent to the project.

4. Results: The Fieldwork

4.1. Lacking Participation in EIA

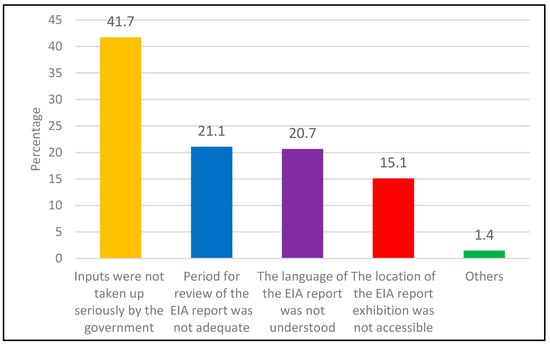

Of the respondents, the greater majority (87.9%) were dissatisfied with the participation in the EIA. In contrast, only 5.4% were satisfied. Probing into this, respondents provided the following reasons (Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Reasons for respondents’ dissatisfaction with the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). Source: This survey.

- 41.7% felt that the authorities did not consider their requests (such as concerning compensation or relocation);

- 21.1% felt unable to effectively review the EIA reports due to the limited period granted to them;

- 20.7% stated that the use of the English language in the reports posed a major barrier;

- 15.1% maintained that the locations where the EIA reports were displayed were too far away from where they lived.

When we examined whether and to what extent respondents felt if the EIA had empowered their public participation, three quarters disagreed, of which 54.5% disagreed strongly. The survey findings were corroborated through the interviews with key informants. As, for instance, one of the plaintiffs in the court case against the government said:

The government does not want to consult us. In this case, the government did not follow the [EIA] regulations.(Interview, Kajing Tubek, villager, RSSA 24-9-2012)

Similarly, a representative from the NGO Sahabat Alam Malaysia, asserted:

Public participation in Malaysia is conducted more as a procedural requirement. Project developers do not encourage it. They tend to be silent rather than to facilitate it.(Interview, Jau-Evong Jok, coordinator, Marudi, Sarawak, 19-9-2012)

4.2. Procedures: Manipulation, Bias, and Distrust

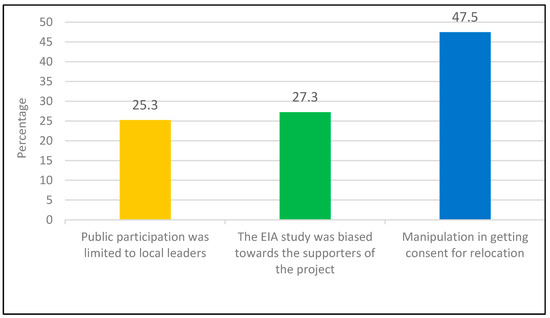

Due to the limited possibilities to participate, the majority (80.0%) of the respondents felt that the authorities had conducted the EIA without complying to procedures. In fact, 36.7% was of the opinion that there were elements of manipulation, while 21.1% felt that the EIA was biased towards project proponents, and 19.5% stated that it focused on local leaders rather than the general populace (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

What are the non-compliance aspects of the EIA? Source: This survey.

The respondents’ negative views on the role of the EIA were reflected by the NGOs. The Executive Director of the Borneo Resources Institute, an indigenous civil organization in Sarawak stated:

In many cases, the EIA process is used to legitimize the project proponent’s action without genuine intention to empower the public. Many do it (sic) just for the sake of procedure or formality, particularly when the project is strongly backed by the government. This is clearly the case in the BHP.(Interview, Mark Bujang, Miri Sarawak, 21 September 2011)

In the next part of the survey, we probed respondents’ view of the government’s role in the EIA. It was found that the majority (80.5%) disagreed that the BHP had increased their trust towards the government. Three-quarters or 75.5% of the respondents disagreed (of which 40% strongly disagreed) that the way in which the EIA had been conducted by the government was acceptable. Lastly, 85.9% agreed (of which 36.8% strongly) that politicians were the ones who reaped the economic benefits from the dam project.

4.3. Conflict Management and Consent

One of the stated objectives of the Malaysian EIA is its role as a platform where social discontent can be managed, facilitated, and channelled through public participation. Consequently, participation is assumed to mitigate social conflict towards the proposed projects. Unfortunately, the survey revealed that 75% of the respondents felt that the public participation had failed to reduce conflict, while 13.6% even felt that it had increased conflict.

In order to have a better understanding of the nature and frequency of conflicts, we asked the respondents about how they protested and how often they were engaged in them. Over half (53.9%) expressed to have resisted against the project through non-violent approaches, such as writing of petitions and letters, amongst them, 37.0% had written between 2–4 times (since the moment they were informed about the project and the time of resettlement) (see Table 1). The second type of protest was through road blocks, to which 18.7% resorted, mostly only one time (by 10.2%). This was closely followed by demonstrations undertaken by 17.4%, with over 12% equally divided over having engaged in it either once or between 2–4 times. Open fights with workers was the form of protestation that was opted for only by 9.4% of the respondents, varying between once (4.1%) to 2–4 times (also 4.1%) before they were resettled.

Table 1.

Type and frequency of protest prior to resettlement.

A final indication of the failure of the EIA to rally greater social support was with regard to the issue of consent (albeit not legally required for projects to go ahead). An overwhelming majority (84.5%) stated that they had not consented to the project, while a similar percentage (86.0%) indicated they had also not agreed with the decision to be relocated.

Other reports have corroborated that local people were forced into relocation through intimidation, tricks, and threats [59]. For instance, the government withheld monetary compensation to force people to accept resettlement at the RSSA [60,61,62]. In this regard, a female leader of one of the communal longhouses stated:

If we have an opportunity, of course we don’t want to move out from Ulu Balui to here. However, the government withheld our compensation money. (…) So, we have to agree to resettle. No option.(Interview, Devong Anjie, headwoman of Uma Nyaving, RSSA, 1 October 2012)

5. Discussion: Limits and Opportunities of the EIA

This article has presented and analysed the EIA of the Bakun Hydro-electric Project. It aimed to demonstrate how the politics and rent-seeking that surround the EIA have been decisive in its failure to safeguard the overall sustainability of the project. By analysing the EIA’s execution itself, coupled to fieldwork in the resettlement area of the indigenous population displaced by the dam, several conclusions can be drawn.

One, both at the federal and the regional state level, there were significant vested interests in an expedient, hasty approval of the EIA. Scholarly discussion has also focused on the question whether rent-seeking in resource-rich economies fosters development, although the evidence on this is inconclusive [63,64]. Through a collusion between large companies that stand to benefit from the dam and the leadership of political parties, such as UMNO, the EIA was diluted into a mere formality. The disregard of a legally required EIA was most glaring in the fact that commencement of the dam construction took place before having been accorded by the Cabinet, and even prior to the EIA’s approval. Whereas the EIA was not submitted for review until September 1994, construction had already started 22 days later. The EIA was approved just 6 months later, in March 1995.

Two, the government’s rush with the EIA has caused widespread resentment among the affected indigenous population. Most respondents (close to 90%) were not satisfied with their level of participation in the EIA. Reasons for this were enumerated as (in order of importance): (1) lacking government attention to information requests; (2) limited time allowed for reviewing the EIA reports; (3) linguistic barriers making it impossible to understand the reports, and; (4) the remote location where the reports were displayed, i.e., in the nation’s capital over 1300 km away from the indigenous settlements. Thus, it is not surprising that four-fifths of the respondents maintained that the government paid scant regard to the EIA procedures. Of these, well over one-third felt that the EIA had been manipulated, whereas one fifth stated that it was biased towards supporters of the dam, and another one fifth maintained it was focused on local leaders and not the general populace.

Three, the EIA’s objective to rally social support for the project through public participation has utterly failed, with almost 9 out of 10 respondents stating that they had not consented to the dam project, nor with the decision to be resettled. Alternatively, one might also ascertain that the objective to push through the BHP with a minimum effort at mitigating environmental impact and social grievances has succeeded. Demonstrating this bitter success is the fact that despite evident, widespread resentment over the dam amongst the affected population, it did go into operation nevertheless.

It is in the light of these three reasons that one may read others’ condemnatory typification of the BHP:

If for no other reason, then, Bakun is an excellent case study for policymakers because it intimately sketches the anatomy of failure, a failure of government planning, implementation, and oversight, no matter how technically sound the dam’s concrete face, spillway, or powerhouse become.[18]

When zooming out from our case-study, it can be seen that the BHP is no exception. Regardless of whether we look at large dam projects in the Philippines [5,65], Cambodia [66], or Laos [67], the EIA has been seriously impaired by the larger political context of which it is a part.

In this regard, other studies have called attention to the dynamics of rent-seeking surrounding mega-projects. It has, for instance, been observed that in Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia, the support for the EIA by political and corporate decision-makers was low [68]. Others duly noted:

Policy failures on environmental grounds need to be grasped for what it is—not as an overnight, nor as a faulty judgement. The decision of public policies in these countries is too often shaped both directly and indirectly, by those with a vested interest in the continued mismanagement of natural resources.[69]

Is this study testimony to the inefficacy and futility of the EIA? Not quite. There might be a dual lesson to be learnt from mega-dam projects. First, there is a tiny, yet limited window of opportunity through which the EIA practitioner (or opponents of the project) could hope to influence decision-making. Projects with the magnitude of the BHP tend to acquire an own momentum, due to the substantive economic interests and political prestige vested in them, leaving two ways out: to divert it, or if all fails, to divide it. Diverting a mega-project implies the search for alternatives that may achieve similar objectives, but in ecologically and socially less disruptive ways. For instance, in the case of hydro-electricity, one may consider managing demand through energy saving technologies or behavioural change towards “greener” life-styles [20]. However, when such proposals run counter to political realities, one could also try lobbying for the division of a mega-project into smaller, more manageable components (which could be politically more palatable than scrapping the project altogether). In both cases, diversion or division, the EIA might have an important role to play.

There is a second lesson from this case-study: if none of the options above are accepted, and the project is still given the green light, the EIA practitioner is to tread with extreme care not to legitimize something that should have been halted. With the legacy of the BHP by and large unresolved, there are well-founded concerns that such a scenario might unfold once more, not in the least given Sarawak State’s plans to build another ten to twelve dams.

Author Contributions

P.H. (conceptualization; writing; funding acquisition; oversight); B.M.S.N.-H. (writing; methodology; formal analysis; data collection; visualization); H.Z. (methodology; validation; formal Analysis; corrections). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China National Science Foundation, grant number 71573231.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The respondents’ profile.

Table A1.

The respondents’ profile.

| Gender | Number | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 215 | 97.7 |

| Female | 5 | 2.3 |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

| Age Cohort | Number | % of total |

| 18–30 years | 7 | 3.18 |

| 31–40 years | 11 | 5.00 |

| 41–50 years | 53 | 24.09 |

| 51–60 | 87 | 39.55 |

| 61 and above | 62 | 28.18 |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

| Education | Number | % of total |

| University | 3 | 1.4 |

| College | 8 | 3.6 |

| High school | 58 | 26.4 |

| Junior high school | 54 | 24.5 |

| No formal education | 97 | 44.1 |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

| Current Occupation | Number | % of total |

| Professional and administrator | 6 | 2.7 |

| Clerical | 3 | 1.4 |

| Farmer | 164 | 74.5 |

| Logging worker | 18 | 8.2 |

| Transport worker | 12 | 5.5 |

| Others | 17 | 7.7 |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

| Household Size | Number | % of total |

| <3 | 30 | 13.64 |

| 4–5 | 113 | 51.36 |

| > 6 | 77 | 35.00 |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

| Monthly Income | Number | % of total |

| RM 451.00–RM 700.00 | 153 | 69.6 |

| RM 701.00–RM 1450.00 | 50 | 22.7 |

| RM 1451.00–RM 2450.00 | 14 | 6.4 |

| RM 2451.00 and above | 3 | 1.4 |

| Total | 220 | 100 |

List of interviewees

- Anjie, D, a Headwoman of Uma Nyaving, at the RSSA on 1 October 2012

- Bit, S., a Penghulu, at the RSSA on 30 September 2012

- Bujang, M. an Executive Director of BRIMAS, in Miri Sarawak on 21 September 2011

- Igang, D., a villager at the RSSA, by telephone on 22 July 2013

- Igang, N., a Teacher at the RSSA on 11 October 2012

- Imu, S., a villager and NGO Activist, at the RSSA on 12 October 2012

- Jok, J-E, a Coordinator from SAM Sarawak, in Marudi, Sarawak on 19 September 2012

- Kulleh, T., a Pemancar, at RSSA on 2 October 2012

- Ligue, M., an Assistant of Tuai Umah from Uma Balui Liko, on 16 October 2012

- Lihan, M.M., Chairman of the Village Development and Security Committee of the RSSA, at RSSA Bakun Sarawak on 25 May 2011

- Lusat, K., Assistance District Office (ADO) of Sub-district Office of Sungai Asap, at the RSSA on 25 September 2015

- Magui, M., a Tuai Umah of Uma Penan, at the RSSA on 11 October 2012

- Nyipa, L., a Tuai Umah of Uma Lahanan, at the RSSA on 7 October 2012

- Sanggul, A., a resettler, at the RSLB on 25 September 2012

- Tubek, K., a villager cum a plaintiff, at the RSSA on 24 September 2012

- Tungau, L., a villager, at the RSSA on 23 May 2011

- Umek, J., a Pemancar, at the RSSA on 29 September 2012

- Urun, A, a villager at RSSA on 1 October 2012)

List of interviewed organizations

- Association of the Orang Asal Network Peninsular Malaysia (JOAS)

- Borneo Research Institute (BRIMAS)

- Consumers’ Association of Penang (CAP), Malaysia

- Department of Environment (DOE) of Kuala Lumpur

- Department of Environment (DOE) of Putrajaya (HQ)

- Economic Planning Unit (EPU), Prime Minister’s Department

- Ministry of Energy, Green Technology and Water (MEGTW)

- Natural Resources and Environmental Board (NREB)

- Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM), Penang

- Sahabat Alam Malaysia (SAM), Sarawak

- Sarawak Hydro Berhad

- Sarawak Economic Planning Unit, Kuching Sarawak

- Sub-district Office of Sungai Asap, Sarawak

- Traditional administrators at the Resettlement Scheme of Sungai Asap, Sarawak

- Village Development and Security Committee of the RSSA, Sarawak

References

- Clark, B.D.; Turnbull, R.G.H. Proposals for environmental impact assessment procedures in the UK. In Planning and Ecology; Roberts, R.D., Ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Wathern, P. An introductory guide to EIA. In Environmental Impact Assessment: Theory and Practice; Wathern, P., Ed.; Unwin Hyman Ltd.: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Canter, L.W. Environmental Impact Assessment, 2nd ed.; Irwin McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Glasson, J. The first 10 years of the UK EIA system: Strengths, weakness, opportunities and threats. Plan. Pract. Res. 1999, 14, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravante, M.A.; Holden, W.N. Going through the motions: The environmental impact assessment of nonferrous metals mining projects in the Philippines. Pac. Rev. 2009, 22, 523–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formby, J. The politics of environmental impact assessment. Impact Assess. 1990, 8, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortolano, L. Environmental Regulation and Impact Assessment; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jay, S.; Jones, C.; Slinn, P.; Wood, C. Environmental impact assessment: Retrospect and prospect. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amy, J.D. Decision techniques for environmental policy: A critique. In Managing Leviathan: Environmental Politics and the Administrative Statel; Paehlke, R., Torgerson, D., Eds.; Broadview Press Ltd.: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, R.V. Ecological reason in administration: Environmental impact assessment and administrative theory. In Managing Leviathan: Environmental Politics and the Administrative State; Paehlke, R., Torgerson, D., Eds.; Broadview Press Ltd.: Peterborough, ON, Canada, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R.L.; Parnwell, M.J.G. Introduction: Politics, sustainable development and environmental change in South-East Asia. In Environmental Change in South-East Asia: People, Politics and Sustainable Development; Bryant, R.L., Parnwell, M.J.G., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrs, T. Environmental Integration: Our Common Challenge; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tenney, A.; Kvaerner, J.; Gjerstad, K.I. Uncertainty in environmental impact assessment predictions: The need for better communication and more transparency. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2006, 24, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipper, B.; Jones, C.; Wood, C. Monitoring and post-auditing in environmental impact assessment: A review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1998, 41, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, J. EIA in a risk society. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2004, 47, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.P. Impact significance determination-Pushing the boundaries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2007, 27, 770–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijabadeniyi, A.; Vanclay, F. Socially-tolerated practices in environmental and social impact assessment reporting: Discourses, displacement, and impoverishment. Land 2020, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, Y.K. Sustainable Development—An institutional enclave (with special reference to the Bakun Dam-Induced development strategy in Malaysia). J. Econ. Issues 2005, 39, 951–971. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Bulan, L.C. Behind an ambitious megaproject in Asia: The history and implications of the Bakun hydroelectric dam in Borneo. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 4842–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.C.; Viswanathan, K.K.; Ali, J. Compensation policy in a large development project: The case of the Bakun hydroelectric dam. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2015, 31, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, Y.K. Sustainable development and the social and cultural impact of a dam-induced development strategy—The Bakun experience. Pac. Aff. 2004, 77, 50–68. [Google Scholar]

- Andre, E. Beyond hydrology in the sustainability assessment of dams: A Planners perspective—The Sarawak experience. J. Hydrol. 2012, 412, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, P.A. Devolution of environmental regulation: Environmental impact assessment in Malaysia. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2000, 18, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INSAN. Power Play: Why We Condemn the Bakun Hydroelectric Project; INSAN: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, T. Malaysia’s Bakun Project: Build and be Damned. 2000. Available online: http://www.atimes.com/reports/BJ28Ai01.html (accessed on 20 August 2010).

- Beck, M.W.; Claassen, A.H.; Hundt, P.J. Environmental and livelihood impacts of dams: Common lessons across development gradients that challenge sustainability. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2012, 10, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E. Malaysia Shelves Plans for Undersea Power Cable. 2010. Available online: http://www.businessweek.com/ap/financialnews/D9FKJ6GG0.htm (accessed on 20 August 2013).

- Aiken, S.R. Environment and the federal government in Malaysia. Appl. Geogr. 1998, 8, 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, S. Economic development and environmental management in Malaysia. New Zealand Geogr. 1993, 49, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanarajasingam, S. Background Paper on Law, Policy and the Implementation of a Conservation Strategy; Economic Planning Unit (EPU) Prime Minister’s Department of Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1992.

- Ramakrishna, S. The environmental movement in Malaysia. In Social Movement in Malaysia: From Moral Communities to NGOs; Weiss, M.L., Hassan, S., Eds.; Routledge Curzon: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken, S.R.; Leigh, C.H. Land use conflicts and rainforest conservation in Malaysia and Australia. Land Use Policy 1986, 3, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staerdahl, J.; Zakaria, Z.; Dewar, N.; Panich, N. Environmental impact assessment in Malaysia, South Africa, Thailand, and Denmark: Background, layout, context, public participation and environmental scope. J. Transdiscipl. Environ. Stud. 2004, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.Y.C. Background Paper on Development and Implementation of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) System in Malaysia; Economic Planning Unit (EPU) Prime Minister’s Department of Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- GOM (Government of Malaysia). Fourth Malaysia Plan. (1981–1985); Government Printers: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1979.

- Pura, R. Court Decision Poses Hurdle for Malaysia’s Bakun Dam. 1996. Available online: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB835214167654346500 (accessed on 10 August 2010).

- Gomez, E.T. Chinese Business in Malaysia: Accumulation, Accommodation and Ascendance; Curzon Press: Richmond, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wain, B. Malaysian Maverick: Mahathir Mohamad in Turbulent Times; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, E.T.; Jomo, K.S. Malaysia’s Political Economy: Politics, Patronage and Profits; University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- The Borneo Post. Govt to Ensure Runway and Flyover Projects Completed—CM. 2010. Available online: http://www.theborneopost.com/2010/11/23/govt-to-ensure-runway-and-flyover-projects-completed-%E2%80%93-cm/ (accessed on 20 August 2011).

- Utusan Konsumer. Big Money for Big Boys: All in the Family—Cahaya Mata Sarawak Berhad (CMSB); Utusan Konsumer: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 2001; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- GOM (Government of Malaysia). Environmental Quality Act. 1974: Regulations, Rules & Orders (as at 20st November 2013); International Law Book Services: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Utusan Konsumer. Law Gives Bakun EIA Assurance: UNIMAS Pressured to Complete EIA Study Early? Utusan Konsumer: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 1994; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Utusan Konsumer. Sheer Mockery in EIA Approval! Utusan Konsumer: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 1995; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Utusan Konsumer. Cabinet Accepts EIA in Stages; Utusan Konsumer: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 1995; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Nijar, G.S. The Bakun dam case: A critique. Malay. Law J. 1997, 3, 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- DOE (Department of Environment). A Handbook of Environmental Impact Assessment Guidelines, 5th ed.; Department of Environment, Ministry of Natural Resource & Environment: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2009.

- ALIRAN. Cancellation of forum on Bakun: Violation of human right. ALIRAN, 14 April 1994; 7. [Google Scholar]

- Utusan Konsumer. PM Grossly Misled on Bakun: Govt Should Welcome Fair Comment; Utusan Konsumer: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 1995; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Brannen, J. Mixing Methods: The entry of qualitative and quantitative approaches into the research process. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sub-District Office of Sungai Asap. Basic Profile of Sungai Asap Population. Unpublished; 2012. Available online: http://www.ictu.tmp.sarawak.gov.my/seg.php?recordID=M0055&contentID=SM0124 (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- ICU (Implementation and Coordination Unit). Press Release: Information System on National Poverty (e-kasih). 2011. Available online: http://www.icu.gov.my/pdf/kenyataan/kenyataan_media_ekasih.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2011).

- EPU (Economic Planning Unit). Bakun Hydroelectric Project: Green Energy for the Future; Economic Planning Unit (EPU), Prime Minister’s Department of Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1996.

- Babbie, E. The Practice of Social Research, 14th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approach, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: Hudson, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Small, M.L. How many cases do I need? On science and the logic of case selection in field-based research. Ethnography 2009, 10, 5–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M. Editorial: Qualitative significance. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 151–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutnyk, J. Resettling Bakun: Consultancy, anthropologists and development. Left Curve 1999, 23, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Utusan Konsumer. Sweet on the Outside, Sour in the Inside; Utusan Konsumer: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 2000; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Gabungan (The Coalition of Concerned NGOs on Bakun of Malaysia). The Resettlement of Indigenous People Affected by the Bakun Hydro-Electric Project, Sarawak, Malaysia. 1999. Available online: http://www.internationalrivers.org/files/attached-files/resettlement_of_indigenous_people_at_bakun.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2010).

- Gabungan (The Coalition of Concerned NGOs on Bakun of Malaysia). The Mother of Bakun: Fact. Finding Mission on Bakun Dam; Gabungan: Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Loewenstein, W. A note on revenue distribution patterns and rent-seeking incentive. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2018, 8, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R. Distributional bargaining and the speed of structural change in the petroleum exporting labor surplus economies. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020, 32, 51–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Greening the dam: The case of the San Roque multi-purpose project in the Philippines. Geoforum 2010, 41, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensengerth, O. Hydropower planning in institutional settings: Chinese institutions and the failures of environmental and social regulation in Cambodia. In Evolution of Dam Policies: Evidence from the Big Hydropower States; Scheumann, W., Hensengerth, O., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, M. Imperial Nature: The World Bank and Struggles for Social Justice in the Age of Globalization; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, J. Cultural influences on implementing environmental impact assessment: Insights from Thailand, Indonesia, and Malaysia. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1998, 18, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad, R. The political economy of natural resources: Case studies of the Indonesian and Philippines forest sector. Dev. Areas 1995, 29, 317–340. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).