Sustainable City and Community Empowerment through the Implementation of Community-Based Monitoring: A Conceptual Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

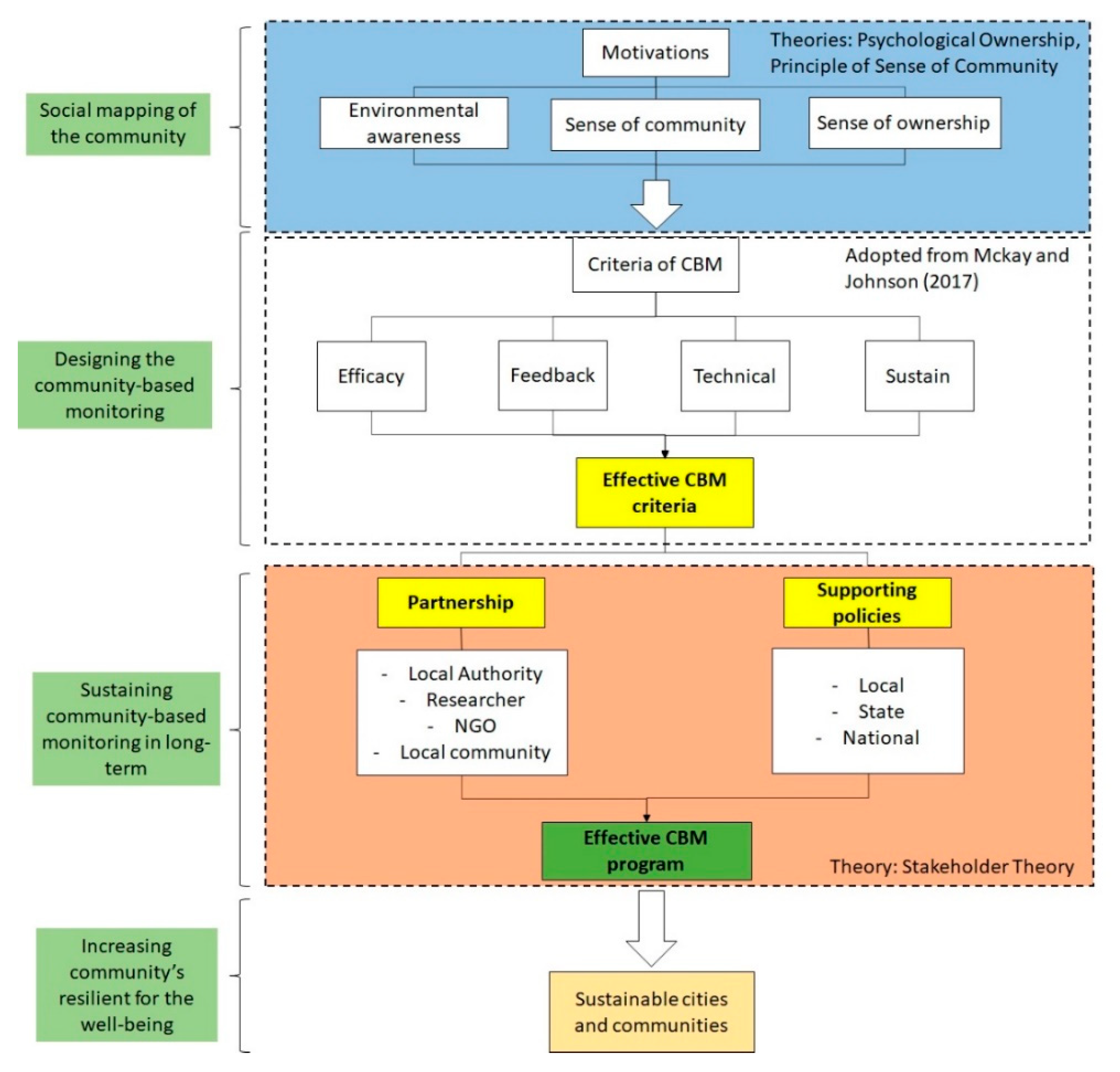

3. The Development of Conceptual Framework

- (1)

- the development of social mapping to collect and socialise proper understanding of local community personalities and interests,

- (2)

- the design of a people-centred environmental monitoring network assisted by manual and automated instrumentation,

- (3)

- the act to sustain the monitoring programme by assessing the current policies related to the subject, and

- (4)

- the communication and pedagogical strategies emerged and implemented during the process, to articulate the different members and sources of knowledge involved.

3.1. Social Mapping of the Community

3.1.1. Sense of Ownership

3.1.2. Sense of Community

3.1.3. Environmental Awareness

3.2. Designing Community-Based Monitoring

3.2.1. Efficacy of Monitoring

3.2.2. Technicalities of Monitoring

3.2.3. Feedback Mechanism

3.2.4. Sustainability of the Initiative

3.3. Sustaining Community-Based Monitoring in the Long-Term

3.4. Increasing the Community’s Resilient for the Well-Being

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dassen, T.; Kunseler, E.; van Kessenich, L.M. The sustainable City: An analytical–deliberative approach to assess policy in the context of sustainable urban development. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 21, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Abdullah, R.; Hanafiah, M.M.; Halim, A.A.; Mokhtar, M.; Goh, C.T.; Alam, L. An integrated approach for stakeholder participation in watershed management. In Environmental Risk Analysis for Asian-Oriented, Risk-Based Watershed Management; Yoneda, M., Mokhtar, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 35–143. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, C.T.; Daoust, T. Community-based monitoring frameworks: Increasing the effectiveness of environmental stewardship. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, R.; Rosolen, S.; Whitelaw, G.; Bennett, L. Multi-party monitoring in Ontario: Challenges and emerging solutions. Environments 2006, 34, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Whitelaw, G.; Vaughan, H.; Craig, B.; Atkinson, D. Establishing the Canadian community monitoring network. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2003, 88, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, A.J.; Johnson, C.J. Identifying effective and sustainable measures for community-based environmental monitoring. Environ. Manag. 2017, 60, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachapelle, P.R.; McCool, S.F. Exploring the concept of “ownership” in natural resource planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2017, 18, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süssenbach, S.; Kamleitner, B. Psychological ownership as a facilitator of sustainable behaviors. In Psychological Ownership And Consumer Behavior; Springer: Cham, Swizerland, 2018; pp. 211–225. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, G.K. Community Engagement to Promote Environmental Ownership and Secure Our Future. In 50 Years of Environment: Singapore’s Journey Towards Environmental Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Tan, Y.S., Ed.; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2016; pp. 193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Chari, R.; Matthews, L.J.; Blumenthal, M.; Edelman, A.F.; Jones, T. The Promise Of Community Citizen Science; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, P.; Sugerman-Brozan, J.; Wiggins, S.; Noiles, D.; Archibald, C. From asthma to AirBeat: Community-driven monitoring of fine particles and black carbon in Roxbury, Massachusetts. Environ. Health Perspect. 2002, 110, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, S.A.; Terveen, L. October. Quality is a verb: The operationalisation of data quality in a citizen science community. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Wikis and Open Collaboration, ACM 2011, Mountain View, CA, USA, 3–5 October 2011; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Coenen, F. Local Agenda 21: ’meaningful and effective’ participation? In Public Participation and Better Environmental Decisions; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, B.; Usui, M. Local Agenda 21 in Japan: Transforming local environmental governance. Local Environ. 2002, 7, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 68% of the World Population Projected to Live in Urban Areas by 2050, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, (UN DESA). 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 25 March 2019).

- Parnell, S. Defining a global urban development agenda. World Dev. 2016, 78, 529–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Cities. Sustain. Dev. Action 2015. United Nations Sustainable Development. 2016. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/cities/ (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Pires, S.M.; Fidélis, T.; Ramos, T.B. Measuring and comparing local sustainable development through common indicators: Constraints and achievements in practice. Cities 2014, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Stern, P.C. Public Participation in Environmental Assessment and Decision Making; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, J.; Barrett, G. Mapping the outcomes of citizen engagement. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2399–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall, A. Unpacking ‘Participation’: Models, meanings and practices. Community Dev. J. 2008, 43, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, D.J. Citizen participation and environmental risk: A survey of institutional mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 1990, 15, 226–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D.D.; Zimmerman, M.A. Empowerment theory, research, and application. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1995, 23, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonney, R.; Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Kelling, S.; Phillips, T.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Shirk, J. Citizen science: A developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy. BioScience 2009, 59, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, C.C.; Hilchey, K.G. A review of citizen science and community-based environmental monitoring: Issues and opportunities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 176, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, P.; Abeyasekera, S. Effectiveness of participatory planning for community management of fisheries in Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 86, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.E.; Pocock, M.J.; Preston, C.D.; Roy, D.B.; Savage, J.; Tweddle, J.C.; Robinson, L.D. Understanding Citizen Science and Environmental Monitoring: Final Report on Behalf of UK Environmental Observation Framework; UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology: Lancaster, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.J.; Jisming-See, S.W.; Brandon-Mong, G.J.; Lim, A.H.; Lim, V.C.; Lee, P.S.; Sing, K.W. Citizen science: The first Peninsular Malaysia butterfly count. Biodivers. Data J. 2015, e7159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, M.S. Science, expertise, and the democratisation of the decision-making process. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, L.; Debbie, A.; Deagen, R. Choosing public participation methods for natural resources: A context-specific guide. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2001, 14, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, R.M.; Whitelaw, G.S. Community-based monitoring in support of local sustainability. Local Environ. 2005, 10, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasny, M.E.; Russ, A.; Tidball, K.G.; Elmqvist, T. Civic ecology practices: Participatory approaches to generating and measuring ecosystem services in cities. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 7, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthill, M. An interpretive approach to developing volunteer-based coastal monitoring programmes. Local Environ. 2000, 5, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Forsythe, N.; Parkin, G.; Gowing, J. Filling the observational void: Scientific value and quantitative validation of hydrometeorological data from a community-based monitoring programme. J. Hydrol. 2016, 538, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongo, V.M.; Kosgei, J.R.; Jewitt, G.P.W.; Lorentz, S.A. Establishment of a catchment monitoring network through a participatory approach in a rural community in South Africa. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 14, 2507–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, P.A.; Villegas, J.C.; Machado, J.; Serna, A.M.; Vidal, L.M.; Vieira, C.; Cadavid, C.A.; Vieira, S.C.; Ángel, J.E.; Mejía, Ó.A. Reducing social vulnerability to environmental change: Building trust through social collaboration on environmental monitoring. Weather Clim. Soc. 2016, 8, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloeckner, H.; Mkanga, M.; Ndezi, T. Local empowerment through community mapping for water and sanitation in Dar es Salaam. Environ. Urban. 2004, 16, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. The socio-economics of property. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1991, 6, 465–468. [Google Scholar]

- Furby, L. Understanding the psychology of possession and ownership: A personal memoir and an appraisal of our progress. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1991, 6, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.L.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K.T. The state of psychological ownership: Integrating and extending a century of research. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2003, 7, 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilainen, A.; Pohja-Mykrä, M.; Lähdesmäki, M.; Kurki, S. “I feel it is mine!”–Psychological ownership in relation to natural resources. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’driscoll, M.P.; Pierce, J.L.; Coghlan, A.M. The psychology of ownership: Work environment structure, organisational commitment, and citizenship behaviours. Group Organ. Manag. 2006, 31, 388–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Wall, T.D.; Jackson, P.R. “That’s not my job”: Developing flexible employee work orientations. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 899–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, A.; Wilson, N.; Wright, M. The perception and effects of share ownership: Empirical evidence from employee buy-outs. Br. J. Ind. Relat. 1998, 36, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Rodgers, L. The psychology of ownership and worker-owner productivity. Group Organ. Manag. 2004, 29, 588–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandewalle, D.; Van Dyne, L.; Kostova, T. Psychological ownership: An empirical examination of its consequences. Group Organ. Manag. 1995, 20, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, S.H.; Parker, C.P.; Christiansen, N.D. Employees that think and act like owners: Effects of ownership beliefs and behaviors on organisational effectiveness. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 847–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portschy, S. Community participation in sustainable urban growth, case study of Almere, The Netherlands. Pollack Periodica 2016, 11, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetell, B.A.; Knuth, B.A. Participation rhetoric or community-based management reality? Influences on willingness to participate in a Venezuelan freshwater fishery. World Dev. 2004, 32, 793–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavis, D.M.; Hogge, J.H.; McMillan, D.W.; Wandersman, A. Sense of community through Brunswik’s lens: A first look. J. Community Psychol. 1986, 14, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, K.M.; Zautra, A.J. Coping with a community stressor: The threat of a hazardous waste facility. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1985, 26, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, D.W. Sense of community. J. Community Psychol. 1996, 24, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.M.; Hungerford, H.R.; Volk, T.L. Environmental education in the K-12 curriculum: Finding a niche. J. Environ. Educ. 1992, 23, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju-Autti, P. Measuring Environmental Awareness in Nineteen States in India. Univ. J. Environ. Res. Technol. 2013, 3, 544–554. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Z.; Wang, X. Survey and evaluation on residents’ environmental awareness in Jiangsu Province of China. Int. J. Environ. Pollut. 2002, 17, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen-Hertell, M.; Harju-Autti, P.; Kreft-Burman, K.; Pemberton, D. Raising Environmental Awareness in the Baltic Sea Area; The Finnish Environment Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bliss, J.; Aplet, G.; Hartzell, C.; Harwood, P.; Jahnige, P.; Kittredge, D.; Lewandowski, S.; Soscia, M.L. Community-based ecosystem monitoring. J. Sustain. For. 2001, 12, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.L.; Shirk, J.; Bonter, D.; Bonney, R.; Crain, R.L.; Martin, J.; Phillips, T.; Purcell, K. The current state of citizen science as a tool for ecological research and public engagement. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2012, 10, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, D.C.; Miller-Rushing, A.J.; Ballard, H.L.; Bonney, R.; Brown, H.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Evans, D.M.; French, R.A.; Parrish, J.K.; Phillips, T.B.; et al. Citizen science can improve conservation science, natural resource management, and environmental protection. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 208, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, L.E.; Shannon, M.A. Getting to know ourselves and our places through participation in civic social assessment. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2000, 13, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, A.; Páez, R.; Carmona, E.; Rivas, H. A systems approach to modeling community-based environmental monitoring: A case of participatory water quality monitoring in rural Mexico. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 10297–10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, T.; Cohen, A. Linking community-based monitoring to water policy: Perceptions of citizen scientists. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 219, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckland-Nicks, A.; Castleden, H.; Conrad, C. Aligning community-based water monitoring program designs with goals for enhanced environmental management. J. Sci. Commun. 2016, 15, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérin-Lajoie, J.; Herrmann, T.M.; MacMillan, G.A.; Hébert-Houle, É.; Monfette, M.; Rowell, J.A.; Anaviapik Soucie, T.; Snowball, H.; Townley, E.; Lévesque, E.; et al. IMALIRIJIIT: A community-based environmental monitoring program in the George River watershed, Nunavik, Canada. Écoscience 2018, 25, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomani, M.C.; Dietrich, O.; Lischeid, G.; Mahoo, H.; Mahay, F.; Mbilinyi, B.; Sarmett, J. Establishment of a hydrological monitoring network in a tropical African catchment: An integrated participatory approach. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2010, 35, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overdevest, C.; Orr, C.H.; Stepenuck, K. Volunteer stream monitoring and local participation in natural resource issues. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2004, 11, 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen, F.; Burgess, N.D.; Balmford, A. Monitoring matters: Examining the potential of locally based approaches. Biodivers. Conserv. 2005, 14, 2507–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, F.; Burgess, N.D.; Jensen, P.M.; Pirhofer-Walzl, K. Environmental monitoring: The scale and speed of implementation varies according to the degree of people’s involvement. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 47, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M. Streamlining non-governmental organisations’ programs towards achieving the sustainable development goals: A conceptual framework. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.M.; Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M. Mainstreaming, Institutionalising and Translating Sustain. Dev. Goals into Non-Governmental Organization’s Programs. In Concepts and Approaches for Sustainability Management; Lee, K.E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, N.; Alessa, L.; Gearheard, S.; Gofman, V.; Kliskey, A.; Pulsifer, P.; Svoboda, M. Strengthening Community-Based Monitoring in the Arctic: Key Challenges and Opportunities; A Community White Paper Prepared for the Arctic Observing Summit; Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rotman, D.; Hammock, J.; Preece, J.; Hansen, D.; Boston, C.; Bowser, A.; He, Y. Motivations affecting initial and long-term participation in citizen science projects in three countries. iConf. 2014 Proc. 2014, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, A.; Conrad, C. Community based ecological monitoring in Nova Scotia: Challenges and opportunities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2006, 113, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, T.C.; Rousseau, F.R.; Hildebrand, L.P. Community-based environmental management in Atlantic Canada: The impacts and spheres of influence of the Atlantic Coastal Action Program. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2006, 113, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Huijstee, M.M.; Francken, M.; Leroy, P. Partnerships for sustainable development: A review of current literature. Environ. Sci. 2007, 4, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, F.; Burgess, N.D.; Balmford, A.; Donald, P.F.; Funder, M.; Jones, J.P.; Alviola, P.; Balete, D.S.; Blomley, T.O.M.; Brashares, J.; et al. Local participation in natural resource monitoring: A characterisation of approaches. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, A.; Zusman, E.; Nakano, R.; Nagano, A.; Dedicatoria, R.M.; Asakawa, K. Filling Environmental Data Gaps for SDG 11: A survey of Japanese and Philippines cities with recommendations. In Achieving and Sustaining SDGs 2018 Conference: Harnessing the Power of Frontier Technology to Achieve the Sustain. Dev. Goals (ASSDG 2018); Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Magis, K. Community resilience: An indicator of social sustainability. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2010, 23, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, D.; Reynolds, E.; Bates, M.E.; Morgan, H.; Clark, S.S.; Linkov, I. Resilience and sustainability: Similarities and differences in environmental management applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemiss, L.; Parrish, B.D. Building capacity for low-carbon communities: The role of grassroots initiatives. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 7559–7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raco, M. Securing sustainable communities: Citizenship, safety, and sustainability in the new urban planning. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2007, 14, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseland, M. Toward Sustainable Communities: Solutions for Citizens and Their Governments; New Society Publishers: Gabriola, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. United Nations Conference on Environment & Development Rio de Janerio, Brazil, 3–14 June 1992, Agenda 21. 1992. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2020).

| Programme Areas | Objectives | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Integrating environment and development at the policy, planning and management levels |

|

|

| Establishing systems for integrated environmental and economic accounting |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muhamad Khair, N.K.; Lee, K.E.; Mokhtar, M. Sustainable City and Community Empowerment through the Implementation of Community-Based Monitoring: A Conceptual Approach. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229583

Muhamad Khair NK, Lee KE, Mokhtar M. Sustainable City and Community Empowerment through the Implementation of Community-Based Monitoring: A Conceptual Approach. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229583

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuhamad Khair, Nur Khairlida, Khai Ern Lee, and Mazlin Mokhtar. 2020. "Sustainable City and Community Empowerment through the Implementation of Community-Based Monitoring: A Conceptual Approach" Sustainability 12, no. 22: 9583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229583

APA StyleMuhamad Khair, N. K., Lee, K. E., & Mokhtar, M. (2020). Sustainable City and Community Empowerment through the Implementation of Community-Based Monitoring: A Conceptual Approach. Sustainability, 12(22), 9583. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229583