Abstract

Waste cooking oil (WCO) can be a useful secondary raw material, if properly managed. On the contrary, uncontrolled disposal generates negative environmental impacts as well as economic loss. Therefore, improving WCO recovery rate, with the cooperation of citizens and effective collection programs, is fundamental. The aim of the study was to investigate the reason for the low recovery of WCO in those areas suffering serious waste management problems such as the Campania region in Southern Italy. For this purpose, the case of a WCO collection program adopted in Angri, a town of around 34,000 people with a high population density, was studied. In 2015, the collection program was managed by a social cooperative, while, in 2016, after the change of the local government, the collection of WCO was entrusted to a private company. In 2015, the households’ participation in the collection program was surveyed through a structured questionnaire. The results revealed that the collection of WCO was practiced by 53% of the respondents. Among those not collecting WCO, 76% of the sample wrongly disposed of WCO in their home (kitchen or toilet). Misinformation was the main reason why they did not adhere to the collection program. Therefore, it was suggested to support information and environmental education campaigns to promote environmental awareness of citizens. Unfortunately, the change of management, together with serious problems in the collection of municipal waste in the whole region, due to the continuous closures of the mechanical and biological plants, produced a sharp decline in the collection from 7730 kg in 2015 to an average of 3800 kg for the period 2016–2019, with a loss of more than 15,000 kg of WCO wrongly disposed with consequent environmental and economic damage. Therefore, information and awareness campaigns are important but the form of entrusting the collection service is equally important, especially in areas with long-standing waste management problems.

1. Introduction

Waste cooking oil (WCO) is a type of domestic waste generated as the result of cooking and frying food with edible vegetable oil [1]. WCO refers mainly to frying oil used at high temperatures, edible fat mixed in kitchen waste and oily wastewater directly discharged into sewers [2].

WCO is considered part of ‘municipal solid waste’ (MSW) which in Italy is a synonym of domestic waste. However, since WCO is part of domestic waste, the use of the acronym ‘MSW’ is not completely correct and, more importantly, it is a proof of the poor attention given to the correct management and collection of WCO. Official statistics on the level of collection of WCO in Europe vary between 100,000 and 700,000 tons/year [1], which equals less than 1 kg per inhabitant per year [3]. The uncontrolled disposal of WCO generates negative environmental impacts as well as economic loss. Diverting WCO from improper forms of disposal extends the product’s life cycle and prevents the contamination of groundwater with this harmful liquid waste [4].

On the contrary, effective collection and controlled disposal of WCO is also interesting from an economic point of view. It is a promising and cost-effective candidate for synthesizing biofuel [5], due to its low cost and availability elsewhere [6]. Energy production from WCO to produce diesel-like fuel is not only a solution for disposing of WCO but is also a means to recover the valuable energy content [7].

Since the seventies, with the Waste Oil Directive 75/439/EEC (repealed on 12 December 2010), the European Commission has suggested that it is fundamental to collect as much as possible waste oils, in order to avoid the contamination of the environment as well as to profit from the recovery of this resource.

Obviously, the Waste Framework Directive 2008/98/EC, and subsequent amendments and additions, also deals with the topic of waste oils. In particular, in Article 21, the Directive states that waste oils have to be collected separately, treated following the waste hierarchy and ensuring the protection of the environment and human health, and avoiding mixing waste oils of different characteristics where this is technically feasible and economically viable.

In China, about 5 million tons of WCO is produced every year, but 40–60% is illegally returned to the kitchen [8]. Even due to this issue, the government has offered recyclers various subsidies to encourage the collection and management of WCO and push back illegal WCO recycling [9]. In Japan, before 1997, WCO was simply disposed of down the sewer. Nowadays, there is cooperation between the communities and the government, thus WCO collection recovery has begun nationwide [9]. In the United States of America, WCO recycling is like Japan, where the stakeholders include biodiesel companies, restaurants and eateries, government and third-party WCO collection companies [9].

Improving the recovery rate is a critical step to efficiently managing the supply chain of WCO-to-biofuel conversion [10]. Lin et al. [11] investigated biodiesel synthesis from WCO using a waste oyster shell-derived catalyst as a sustainable based heterogeneous catalyst under a microwave heating system technology. The European biodiesel market is known as the largest biodiesel market globally and represents the third largest biofuel market in the world [9]. However, the production of biodiesel is not the only recycling option. Mannu et al. [12] investigated the better process conditions to produce bio-lubricant and biosolvent using sunflower WCO, while Nanda et al. [13] evaluated the optimization of syngas production process through WCO gasification. Barbera et al. [14] evaluated the feasibility of renewable jet fuel production from WCO via catalytic transfer hydrogenation using isopropanol as hydrogen donor.

WCO can also be efficiently used in the construction sector. Some authors analyzed the use of WCO for the full recovery of aged bitumen [15,16] or to produce a novel binder rejuvenator [17]. In fact, WCO can be considered as a sustainable product for improving recycling of aged asphalt, because it contains light oil components analogous to those of the virgin bitumen [18].

Regarding the opportunity of WCO valorization, improving the recovery rate is fundamental. Therefore, it is necessary to involve citizens in effective collection programs. Concerning the cultural aspect of cooperation, in Malaysia, NGO (non-governmental organization) volunteers conducted an awareness campaign on the environmental impact caused by the direct discharge of WCO into the drainage system. These volunteers informed the community that disposing of WCO via drainage or a landfill could cause water and soil pollution, as well as disturb the aquatic ecosystem in addition to being a human health concern [19].

Concerning the social and economic aspects, Yacob et al. [20] carried out a sociological survey addressed to Malaysian households in order to estimate their willingness to accept the collection and recycling of WCO. In China, Liu et al. [21] explored the behaviors, awareness, and willingness of restaurants to submit their WCO for biofuel production through random sampling surveys.

Cho et al. [22] investigated the factors that could improve participation in WCO collection in South Korea, including socio-economic factors, awareness, and collection systems. Specifically, they compared a drop-off system in which WCO was collected from central locations in towns, such as supermarkets and religious facilities, with a curbside system in which local recyclers collected WCO through door-to-door visits.

Most of the papers in current literature concern the recovery of waste cooking oil but not its collection, which is almost taken for granted. Moreover, the studies dealing with WCO collection did not consider a wide analysis time interval to evaluate the evolution of WCO collection over the years and the operation/efficiency of the strategies applied to improve its collection.

In addition, unfortunately, separate collection is not common in all areas, especially in areas where there are long-standing problems in waste management. That is why, in light of the situation described above, we wanted to analyze the reason for the low recovery of WCO in those areas suffering serious waste management problems such as the Campania region in Southern Italy [23]. For this purpose, the case of a WCO collection program adopted in Angri, a town of around 34,000 people (around 2500 inhabitants/km2) was studied. The first structured program of WCO collection started at the end of 2014. It was managed by a social cooperative in collaboration with the local government and the waste management company. The functioning of the program was surveyed with a structured questionnaire. Then we analyzed the evolution of the WCO collection efficiency until the end of 2019. In 2016, after the change of the local government, it was decided to change the form of management with a different approach based on an entrustment to a private company without the collaboration of the social cooperative. This gave the opportunity to compare the performance of the WCO collection program in two periods: (1) in 2015 with the presence of the social cooperative; (2) since 2016 with only a private disposal company without the collaboration of the social cooperative. This comparison can be interesting and offer innovative ideas as the results of the comparison can offer elements and criteria to evaluate the convenience of combining a social cooperative with a company that only deals with disposal.

Therefore, the paper presents and discusses the results of the 2015 questionnaire as well as the evolution of the WCO collection, since 2016, in light of the serious problems with domestic waste management present in the area under study and in the whole region, in order to offer issues and topics to reflect on in areas with similar problems all over the world.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Area under Study

The area under study is the municipality of Angri, in the Province of Salerno, in the Campania Region of Southern Italy. Angri is a town of 33,826 inhabitants (derived from the databases of the Italian National Institute of Statistics, Istat) located between the metropolitan areas of Naples and Salerno. The territory of Angri is famous for its fertility due to its unique geographical location at the foot of the Lattari Mountains, next to the Vesuvius area. Angri has an extension of 13.77 km2, with a population density of 2457 inhabitants/km2 and an average altitude of 32 m above sea level. It is worth noting the high population density compared with the Italian average of 199 inhabitants/km2 and the European one of 117 inhabitants/km2. Moreover, Angri is a municipality of the Agro Nocerino Sarnese area, which is a geographical region of the Province of Salerno, crossed by the Sarno river, defined as “the most polluted river in Europe” [24].

The Campania Region has suffered serious problems with the management of municipal solid waste since the mid-1990s [25] mainly due to the absence of treatment plants (composting and anaerobic plants, and incinerators) and the presence of landfills managed illegally that caused serious damage to human health and the environment. Italy was condemned by the European Court of Justice for failing to create an appropriate waste management network in Campania. As a result of its incorrect application of the Waste Directive in Campania, in July 2015, Italy was ordered to pay a lump sum of €20 million and a daily late-payment penalty of €120,000. The daily penalty was divided into three parts, each of a daily amount of €40,000 calculated by category of installation (landfills, incinerators and organic waste treatment installations).

Since 2009, in the Campania region only one waste-to-energy plant is active, with a capacity of 750,000 tons/year, served by seven mechanical and biological plants (MBT) that receive the unsorted residual waste coming from five provinces.

2.2. The WCO Collection System under Study

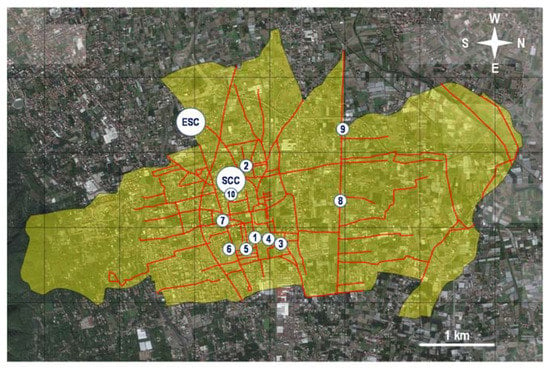

The collection of WCO started in June 2010. At the beginning, people could only deliver WCO into the Separate Collection Center (SCC) (Figure 1). The collection system changed at the end of 2014 with the addition of ten street containers located in the most densely populated areas (Figure 2). Simultaneously, an information campaign was carried out. The new WCO collection service was designed by a social cooperative (BLU Cooperativa Sociale) in collaboration with the municipal waste collection company (Angri Eco Servizi) and the local government.

Figure 1.

Map of Angri with the location of the street containers for the collection of waste cooking oil (WCO). Legend: (i) = number of the street container; SCC = Separate Collection Center; ESC = eco-services company.

Figure 2.

Street containers for the collection of WCO in the municipality of Angri: (a) container 1 (near a school); (b) container 2 (near a church); (c) container 3 (near a school); (d) container 4 (near a school); (e) container 5 (near a school); (f) container 6 (near a shopping center).

The social cooperative conceived and implemented a project entitled “Easy Recycling Oil” in collaboration with the waste management company. The main objective of the project was to offer a better service to the citizens for the collection of WCO as well as to create job opportunities. The project lasted 12 months (from January to December 2015) including two months of the start-up phase at the end of 2014. The project involved only a part of the territory including about 45% of the households.

The project was developed through two collaboration agreements. The first agreement was made with the waste management company. The purpose of the agreement was the collaboration for the start of the WCO collection service with a kerbside collection method. Many advantages derived from the agreement: presence of an organized collection network distributed throughout the territory; distribution of collection tanks to citizens; container maintenance and cleaning; awareness and assistance to citizens; zero cost for the local government.

The second agreement was made with the company responsible for WCO disposal. The purpose of the agreement was the management of WCO recovery from domestic users in the town of Angri. Many advantages also derived from this agreement: cost savings (withdrawal of oil from containers only when full); installation, maintenance and cleaning of street containers; theft control and prevention. For this agreement, the social cooperative was paid a fee of €350 for each ton of oil collected. From the beginning of 2006, the agreements ceased and with them all the consequent advantages.

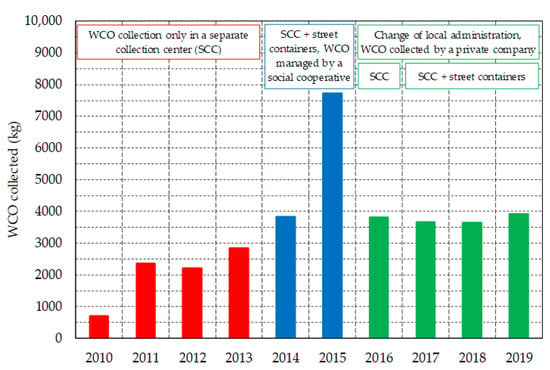

The following quantities of WCO were collected in the period 2010–2015: 710 kg in 2010; 2360 kg in 2011 (+232.4%); 2210 kg in 2012 (−6.4%); 2840 kg in 2013 (+28.5%); 3830 kg in 2014 (+34.9%); 7730 kg in 2015 (+101.8%). Therefore, it was clear the significant increasing in the quantities of WCO collected due to the change introduced in the collection program at the end of 2014. What happened after 2015 is described and commented in the Section 3.2 ‘WCO Collection Efficiency from 2016 to 2019’.

2.3. The Questionnaire

The questionnaire submitted in 2015 was made up of two principal parts, as shown in Table 1. The first part of the questionnaire contains the personal attributes such as age, sex, occupation, as well as educational qualification.

Table 1.

The submitted questionnaire (English translation and adaptation).

The second part contains 13 questions (Qi) aimed at pursuing the specific aims of the study as stated at the end of the introductory section. In particular, Q1, Q2 and Q3 wanted to verify if people knew WCO, if they knew that WCO is collected in their town as well as if they regularly collected it. Q4, Q5 and Q6 were aimed to investigate the behavior of people not adhering to the WCO collection program. Q7 wanted to verify if people knew that there had been an informative campaign in their town about WCO. Q8, Q9, Q10 and Q11 were submitted to people participating in the WCO collection program in order to investigate their behavior. Q12 was aimed at verifying customer satisfaction. Finally, Q13 investigated the households’ behavior.

2.4. The Sample

A sample of 354 people was interviewed, with users being randomly chosen in the streets in the period between 26 September 2015 and 20 October 2015. Considering that those under sixteen were 27,000, the sample dimension corresponded to a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 5.2%.

The sample and the population were divided (and compared) in three age groups: 16–30 years, 31–60 years, and 61–87 years. Table 2 proposes the comparison between the percentages of men and women for each considered each group in the sample and in the population. The 61–87 group is that with the greater difference between the population and sample both for men and women. Table 3 compares the percentages of the different age groups for men, women and total in the sample and in the population. Globally, the youngest and oldest groups were underestimated by the sample, while the middle group was overestimated.

Table 2.

Comparison between percentages of men and women for each considered each group in the sample and in the population.

Table 3.

Comparison of percentages of the different age groups for men, women and total in the sample and in the population.

Employees was the main category of the sample (31.9%), followed by housewives (26.6%), self-employed (22.3%), and, finally, unemployed (19.2%). In terms of educational qualification, 41.4% of people in the sample had a high school certificate, 35.9% had a degree, 12.7% had a middle school certificate and, finally, 12.7% only a primary school certificate.

2.5. The Data Analysis

The frequencies of the observed values were analyzed by means of cross-tabulations. By examining these frequencies, the relations between the cross-tabulated variables were identified.

The Chi-square test for independence was utilized to determine whether the responses to the questions were statistically related to the personal attributes [26]. In particular, the Chi-square test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between the observed frequencies of each single category and the obtained frequencies of the whole sample. The chosen level of significance was 5% (p < 0.05).

The Chi-square test is usually considered risky if more than 20% of the cells have an expected frequency of less than 5, or if a cell has an expected frequency less than 1. In this case, when there were three or more response alternatives, and if the logical meaning of these alternatives was coherent, they were merged.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. WCO Collection Efficiency in 2015 and Citizens’ Perception

3.1.1. The General Results Obtained for the Whole Sample

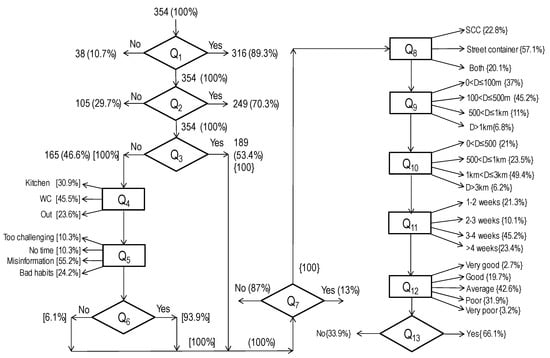

Figure 3 shows the flow chart of the general results obtained for the whole sample for all the submitted questions. Approximately 90% of the sample declared to know WCO (Q1). Slightly more than 70% knew that the collection of WCO (Q2) was carried out in Angri. The collection of WCO was practiced by 53% of the sample (Q3).

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the general results obtained for the whole sample for all the questions.

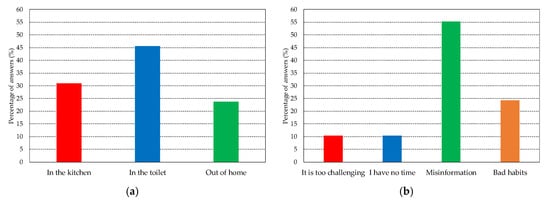

Among those not collecting WCO: as shown in Figure 4a, 76% of the sample wrongly dispose WCO into their home (kitchen or toilet) (Q4); while, as shown in Figure 4b, 55% indicated that misinformation was the main reason why they did not adhere to the collection program (Q5); finally, 94% were aware that not collecting and disposing of WCO correctly can cause serious damage to the environment (Q6).

Figure 4.

Percentage answers of those not collecting WCO: (a) Q4. If you do not collect waste cooking oil, how do you dispose of it? (b) Q5. Why you do not collect waste cooking oil?

Only 13% of the sample knew that there had been an informative campaign in their town about WCO collection (Q7).

Often, the lack of suitable and useful information about the opportunities of waste recycling is one of the most important factors upon which to act in order to improve the participation of citizens in the collection and recycling of waste. This aspect also emerged in the study of Liu et al. [21], where the authors stated that only a very low percentage of respondents indicated that they were informed about the recycling of WCO. Therefore, it is increasingly important to support information and environmental education campaigns to promote the environmental awareness of consumers [27,28].

The majority of those interviewed (i.e., 57%) took their waste cooking oil to the street container (Q8), while 100–500 m was the most frequent distance from their house and the containers’ location (Q9).

Among those not collecting WCO: the street container was the favorite form of WCO disposal (57%) (Q8); 3–4 weeks was the preferred frequency of delivery (Q11); only 35% of the sample considered the WCO collection service poor or very poor (Q12); approximately 34% of the sample stated that they were the only one who collected WCO at their home (Q13).

3.1.2. The Results Obtained for the Single Keys

The Chi-square test of independence (to determine whether there is a significant difference between the expected frequencies and the observed frequencies in one or more categories) was applied to all 13 questions for each single interpretation key.

Table 4 summarizes the results of the application of the Chi-square test on all the questions for the four keys with the frequency and percentage of significance. For each question, there is the average result of the application of the test: this value is a statistical significance indicator. The penultimate row shows the number of times that the Chi-square test was positive, while the bottom row indicates the percentage of the frequency of this occurrence.

Table 4.

Results of the Chi-square test of independence on all the questions for the four keys with frequency and percentage of significance.

The best results in terms of statistical significance were obtained for the keys ‘sex’ and ‘level of education’. For these keys, in three cases out of thirteen, a p-value smaller than the critical threshold (0.05) was obtained. For the other two keys (i.e., ‘age’ and ‘occupation’), for only one question was there a statistical significance between the answers and interpretation key. Whereas, Q13 was the question with the highest significance frequency (3 keys out of 4) and percentage (75%).

For the key ‘age’, Q13 (‘Are you the only one who collect waste cooking oil at your home?’) was the only question with the Chi-square value less than the critical threshold. In particular, the more the age grew, the more the percentage of the people who declared to be the only one dealing with WCO collection increased.

For the key ‘sex’, Q2, Q5 and Q13 were the questions with a statistical significance.

Regarding Q2 (Do you know that waste cooking oil is collected in your town?), women were more informed than men with a difference of 15%.

Regarding Q5 (‘Why do you not collect waste cooking oil?’), women did not collect WCO because they were too busy, while men claimed that they did not collect WCO due to bad habits, pointing the finger towards their wife or mother.

Regarding Q13 (‘Are you the only one who collects waste cooking oil at your home?’), more than 50% of women were the only who collected WCO at their home, while only 10% of men claimed to do the same thing.

Such results agree with those obtained by Echegaray et al. [29] and Yacob et al. [20] who highlighted that women are more willing to collect and recycle waste than men. This aspect highlights a greater concern of women regarding household waste management [20]. However, not all the authors agree. Lang et al. [30] carried out a sociological survey of restaurant owners to explore their awareness about food waste recycling. The results pointed out that, compared with male restaurant owners, female owners showed a lower awareness.

For the interpretation key ‘occupation’, Q13 was again the question with a Chi-square p-value of less than 0.05. The percentage of people who declared to be the only ones who collected WCO was approximately 25% for all the occupation categories, except for housewives. They claimed that they were the only one collecting WCO in 75% of the cases. The ‘peculiar’ role as well as opinion of housewives is not surprising because in Southern Italy, it is mainly housewives who take care of separate collection [31,32].

For the key ‘educational level’, Q1, Q3 and Q6 were the questions with a statistical significance.

Regarding Q1 (‘Do you know what waste cooking oil is?’), the higher the education level was, the more the percentage of positive answers increased.

In relation to Q3 (‘Do you collect waste cooking oil?’), the number of people who declared to be involved in the WCO collection grew with the educational level, with a slight diminution going from people with a secondary school certificate to graduates.

With regard to Q6 (‘Do you know that not collecting waste cooking oil seriously damages the environment?’), there was a constant increasing of positive answers along with the educational level, with 100% of awareness for graduates.

The significance of the key ‘level of education’, as a factor that influences the behavior and attitude of consumers about waste recycling, also emerged in other papers [20,28,30]. The authors of such studies highlighted that a higher educational level corresponds to a greater willingness of consumers to collect and recycle waste [20,28] and a greater level of awareness about it [30].

3.2. WCO Collection Efficiency from 2016 to 2019

The survey conducted in 2015 in the town of Angri pointed out that 90% of those interviewed knew what WCO was, while only 70% knew that there was a WCO collection program in their town. However, only 50% of those interviewed declared that they collected WCO, but it is known that there is often a discrepancy between the respondents’ declared intention and their actual behavior [29,33].

Among people that incorrectly disposed of WCO, 76% of the sample disposed incorrectly of WCO into their home, mainly in the kitchen sink or in the toilet. Unfortunately, these are very common practices, because it can be very simple to pour the oil into the sink when compared to the greater attention and patience needed to pour it into a bottle or tank, with the help of a funnel.

Misinformation was the main reason the interviewees highlighted for their non-participation in the WCO collection program. Only 13% of the sample knew that there had been an informative campaign in their town.

Therefore, to overcome the problems identified, and mainly the misinformation, we suggested organizing information campaigns about WCO environmental damages, in the main town square and near shopping centers, to reach people with a lower level of education. More detailed information about the possibility to recover WCO could be shared in focus groups with citizens and stakeholders.

Moreover, it was suggested that a rewarding competition for housewives could be useful to give prominence to a social category that in a traditional society like Southern Italy still plays a fundamental role. In general, structuring a form of economic return for citizens, perhaps as an incentive, could be an effective way to increase participation in the WCO collection and recycling program [21]. The importance of this factor has also been highlighted in other studies. Dwivedy et al. [34] reported that economic benefits are vital to participation in waste recycling activities and Chi et al. [35] highlighted that the lack of incentives is one of the main reasons discouraging households from collecting and recycling waste.

As stated in the introduction, in 2015, the WCO collection program was managed by a social cooperative. In Italy, the social cooperative is a particular form of cooperative aimed at providing services to the person (type A) or with the management of activities aimed at the job placement of disadvantaged people in the sectors of industry, commerce, services and agriculture (type B). The social cooperative involved in the collection program of WCO in Angri since the end of 2014 and for all 2015 was of the type B. The practice of entrusting the collection of WCO to social cooperatives is quite widespread, even if private companies are equally widespread, which obviously have a different approach and different purposes.

In Angri, the social cooperative was responsible for cleaning the containers, checking their filling level, maintaining the containers, providing information and raising awareness among citizens.

In 2016, after the change of the local government, the collection with the street containers was partially stopped and the citizens could mainly deliver WCO only to the collection center. In September 2016, the local government announced that the collection would regularly start again the next year but with a different approach entrusted to a private company. In 2017, new street containers, identical to the previous ones, were installed, but the collection points became micro landfills with the presence of all kinds of waste, together with bottles and other little containers containing oil and even oil thrown directly onto the asphalt. Unfortunately, this situation of waste abandonment is also quite common for other types of street collection such as the bring system for separate collection of glass packaging. This issue was even pointed out in Sweden and England [36].

To address the problem of waste dumping in the streets, in early 2018, the local government announced the launch of a public awareness campaign on separate collection. At the beginning of March, the councilor for the environment of the municipality held a press conference during which she asked for the cooperation of the entire community to keep the town clean with a synergy between the institution and citizens (Figure 5a). The councilor also announced the involvement of schools in meetings and guided visits to waste treatment plants as well as sending information material on separate collection directly to citizens’ homes. Finally, she emphasized the importance, near the awareness-raising, of continuing to monitor and sanction the citizens who do not comply with the correct rules for the separate collection, in collaboration with the local police and the environmental guards. Controls and effective penalty systems are often necessary to ensure the correct functioning of separate waste collection [37].

Figure 5.

The WCO collection program in the period 2016–2019: (a) press conference of the environmental councilor announcing the new awareness campaign on separate waste collection; (b) an environmental education meeting in a school; (c) the new wheeled bin for WCO collection; (d) control of the delivery of waste by an environmental guard; (e) heaps of unsorted residual waste in the streets due to the closure of the Mechanical and Biological Treatment plant (MBT); (f) the new street containers introduced in June 2019.

The first meetings in schools were held at the end of March and they continued for the following months, also with the participation of the company in charge of collecting WCO (Figure 5b).

Meanwhile, in the same month of March, in the province where the municipality is located, there were serious problems at the MBT plant where unsorted municipal waste was usually delivered, and this created a serious inconvenience in the collection of waste. These problems continued almost throughout the year with inevitable consequences on the correct management of separate collection.

In April 2018, the local government together with the waste management company announced some novelties in program for the collection of WCO and presented the new model of wheeled bins as shown in Figure 5c.

In June 2018, due to the problems at the MBT plant and a lack of collaboration from all the citizens, there was accumulation of unsorted waste in the streets near the collection bins. In order to contrast this phenomenon, the controls of the environmental guards continued as shown in Figure 5d.

Unfortunately, from August to October 2018, the situation was almost the same with heaps of unsorted waste in the streets. Towards the end of October, new containers for WCO collection were installed in two areas of the municipality and in three schools. January 2019 also began with heaps of rubbish in the streets, as shown in Figure 5e.

At the end of April 2019, a training and information course for the personnel of the waste management company was held. The aim of the local government was to improve the efficiency of the waste collection service mainly listening and addressing the management issues highlighted by the collection workers. On this aspect, De Feo and De Gisi [38] surveyed the opinion of waste management workers (and citizens) in a town not far from Angri. In that case, all the workers declared receiving complaints from the citizens but only 25% of the citizens’ complaints were addressed to their work. The workers were divided fifty-fifty in judging the relationship with the citizens. Thus, the workers were more severe than the citizens. Most of the workers were not opposed to adopting a new container to manage the MSW fractions better. In order to improve the quality of the separate collection system, the workers required more suitable collecting vehicles as well as more personnel in order to reduce their workload. Secondly, they suggested increasing the efficacy of controls and penalties to inflict on the citizens not respecting the rules. This latter suggestion agrees with the strategy suggested by the local government in the town of Angri.

In June 2019, new containers were introduced for the collection of WCO, which partially replaced the previous ones. This new model allowed for the collection of oils in a more hygienic and convenient way for the users (Figure 5f).

Based on the analysis of the evolution of WCO collection in the reference period considered (2014–2019), it emerged that the main difference was the change in the management of the WCO collection service. In 2015, the social cooperative entrusted with the service paid meticulous attention to the collection program. The workers of the cooperative, in addition to the cleaning service and control of the collection containers, were very present in the area, building trust with the citizens. The private company to which the service was entrusted since 2016 made a lesser commitment to the territory. Consequently, the quality of the service offered to the citizens decreased. In addition, there were general difficulties in waste management and the malfunctioning of the MBT plant, which contributed to generating a state of confusion that discouraged the citizens from engaging in the separate collection of all the municipal waste fractions.

Figure 6 shows the trend of the quantities of waste cooking oils collected in the town of Angri, in Campania, in the period 2010–2019. The quantity collected in 2015 clearly stands out in the graph, when the collection was managed by the social cooperative, which was able to ensure a widespread and constant presence in the area. All the changes which occurred in the period 2016–2019, together with the difficulties described above, determined a significant diminishing in the quantities collected. In comparison with the amount collected in 2015, it is as if 15,890 kg of waste cooking oil were lost (into the environment) in the period 2016–2019. Where did this amount of oil go? Based on what emerged from the 2015 survey, it can be assumed that about 45% (corresponding to around 7100 kg of WCO) may have ended up in the toilet, about 30% (around 4800 kg) in the kitchen sink and about 25% (around 4000 kg) out of the home.

Figure 6.

Trend of the quantities of waste cooking oils collected in the town of Angri, in the Campania region of Southern Italy, in the period 2010–2019.

4. Conclusions

The present study analyzed the evolution of the WCO collection system in a reference period (2014–2019) in Angri, a town in Southern Italy with serious waste management problems, in order to identify and discuss the main critical issues affecting the collection efficiency and that could be of interest in areas with similar problems.

The results of the sociological survey carried out in 2015 (the year with the highest WCO collection efficiency and in which the WCO collection management was entrusted to a social cooperative) showed that misinformation was the main reason the interviewees highlighted for their non-participation in the program. Therefore, organizing information campaigns was suggested together with suitable strategies to increase citizens’ awareness and participation.

Nevertheless, the collection efficiency decreased significantly in the subsequent years (2016–2017). From the analysis, it emerged that the main reason for the decrease was the change in the management of the collection service. From 2016, the service was entrusted to a private company, which was less present in the area as well as less committed to involving citizens in the collection program and in control activities, compared to the social cooperative.

Other key factor that affected the quality level of the WCO collection was the worsening of the waste management problems from 2016, with continuous interruptions in the operation of the provincial MBT plant. This situation generated a state of confusion, which inevitably also compromised WCO collection.

Therefore, it is possible to conclude that, in areas suffering serious waste management problems, the efficiency of the WCO collection does not depend only on the level of information and awareness of the citizens or on the control activities of their behaviors, but above all on the work carried out by the company or association to which the collection service is entrusted, as well as the ability of the local government to guarantee the stability of the waste management services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.F.; methodology, G.D.F. and S.A.; software, G.D.F. and A.D.D.; validation, C.F. and L.S.O.; formal analysis, G.D.F. and A.D.D.; investigation, A.D.D. and S.A.; resources, A.D.D. and S.A.; data curation, G.D.F. and A.D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D.F., L.S.O. and C.F.; visualization, C.F. and L.S.O.; supervision, G.D.F.; project administration, G.D.F. and S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Iglesias, L.; Laca, A.; Herrero, M.; Díaz, M. A life cycle assessment comparison between centralized and decentralized biodiesel production from raw sunflower oil and waste cooking oils. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 37, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Mortimer, S.R. Waste cooking oil as an energy resource: Review of Chinese policies. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2012, 16, 5225–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortner, M.E.; Müller, W.; Schneider, I.; Bockreis, A. Environmental assessment of three different utilization paths of waste cooking oil from households. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.R.P.; Gomes, M.I.; Barbosa-Póvoa, A.P. Planning waste cooking oil collection systems. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Filho, S.C.; Miranda, A.C.; Silva, T.A.F.; Calarge, F.A.; De Souza, R.R.; Santana, J.C.C.; Tambourgi, E.B. Environmental and techno-economic considerations on biodiesel production from waste frying oil in Sao Paulo city. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 183, 1034–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razack, S.A.; Duraiarasan, S. Response surface methodology assisted biodiesel production from waste cooking oil using encapsulated mixed enzyme. Waste Manag. 2016, 47, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhabhandhu, A.; Tezuka, T. The waste-to-energy framework for integrated multi-waste utilization: Waste cooking oil, waste lubricating oil, and waste plastics. Energy 2010, 35, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ji, H.; Song, Y.; Ma, S.; Xiong, W.; Chen, C.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X. Green preparation of branched biolubricant by chemically modifying waste cooking oil with lipase and ionic liquid. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 122918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.H.H.; Chong, C.T.; Ge, Y.; Ong, H.C.; Ng, J.H.; Tian, B.; Ashokkumar, V.; Lim, S.; Seljak, T.; Józsa, V. Progress in utilisation of waste cooking oil for sustainable biodiesel and biojet fuel production. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 223, 113296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ozturk, U.A.; Zhou, D.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, Q. How to increase the recovery rate for waste cooking oil-to-biofuel conversion: A comparison of recycling modes in China and Japan. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 51, 146–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Amesho, K.T.T.; Chen, C.E.; Cheng, P.C.; Chou, F.C. A cleaner process for green biodiesel synthesis from waste cooking oil using recycled waste oyster shells as a sustainable base heterogeneous catalyst under the microwave heating system. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2020, 17, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannu, A.; Ferro, M.; Dugoni, G.C.; Panzeri, W.; Petretto, G.L.; Urgeghe, P.; Mele, A. Improving the recycling technology of waste cooking oils: Chemical fingerprint as tool for non-biodiesel application. Waste Manag. 2019, 96, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, S.; Rana, R.; Hunter, H.R.; Fang, Z.; Dalai, A.K.; Kozinski, J.A. Hydrothermal catalytic processing of waste cooking oil for hydrogen-rich syngas production. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 195, 935–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbera, E.; Naurzaliyev, R.; Asiedu, A.; Bertucco, A.; Resurreccion, S.K. Techno-economic analysis and life-cycle assessment of jet fuels production from waste cooking oil via in situ catalytic transfer hydrogenation. Renew. Energ. 2020, 160, 428–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, I.; Uz, V.E. Utilizing of Waste Vegetable Cooking Oil in bitumen: Zero tolerance aging approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 227, 116695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uz, V.E.; Gökalp, I. Sustainable recovery of waste vegetable cooking oil and aged bitumen: Optimized modification for short and long term aging cases. Waste Manag. 2020, 110, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingyu, Y.; Ruikun, D.; Naipeng, T. Development of a novel binder rejuvenator composed by waste cooking oil and crumb tire rubber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 236, 117621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, M.; Nizamuddin, S.; Madapusi, S.; Giustozzi, F. Sustainable asphalt rejuvenation using waste cooking oil: A comprehensive review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaakob, Z.; Mohammad, M.; Alherbawi, M.; Alam, Z.; Sopian, K. Overview of the production of biodiesel from Waste cooking oil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 18, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacob, M.R.; Kabir, I.; Radam, A. Households willingness to accept collection and recycling of waste cooking oil for biodiesel input in Petaling District, Selangor, Malaysia. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2015, 30, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Xue, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Kang, X. Restaurants’ behaviour, awareness, and willingness to submit waste cooking oil for biofuel production in Beijing. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 636–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, J.; Park, H.-C.; Heo, E. Incentives for waste cooking oil collection in South Korea: A contingent valuation approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 99, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; De Gisi, S.; Williams, I.D. Public perception of odour and environmental pollution attributed to MSW treatment and disposal facilities: A case study. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 974–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montuori, P.; Triassi, M. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons loads into the Mediterranean Sea: Estimate of Sarno River inputs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; Williams, I.D. Siting landfills and incinerators in areas of historic unpopularity: Surveying the views of the next generation. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2798–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, V.F. Statistics for the Social Sciences; Little, Brown & Company: Toronto, ON, CA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Residents’ behaviors, attitudes, and willingness to pay for recycling e-waste in Macau. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 106, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, J.; Gao, Y.; Xu, H. Survey and analysis of consumers’ behaviour of waste mobile phone recycling in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echergaray, F.; Hanssteinet, F.V. Assessing the intention-behavior gap in electronic waste recycling: The case of Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, L.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, N.; Xue, B.; Han, W. Awareness of food waste recycling in restaurants: Evidence from China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; De Gisi, S. Public opinion and awareness towards MSW and separate collection programmes: A sociological procedure for selecting areas and citizens with a low level of knowledge. Waste Manag. 2010, 30, 958–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; Polito, A.R. Using economic benefits for recycling in a separate collection centre managed as a “reverse supermarket”: A sociological survey. Waste Manag. 2015, 38, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Zhou, K. From intention to behavior: Comprehending residents’ waste sorting intention and behavior formation process. Waste Manag. 2020, 38, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedy, M.; Mittal, R.K. Willingness of residents to participate in e-waste recycling in India. Environ. Dev. 2013, 6, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Wang, M.J.L.; Reuter, M.A. E-waste collection channels and household recycling behaviors in Taizhou of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 80, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, C.H.; Berg, P.E.O.; Clarkson, P.A. The development of systems for property close collection of recyclables: Experiences from Sweden. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2003, 38, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agovino, M.; D’Uva, M.; Garofalo, A.; Marchesano, K. Waste management performance in Italian provinces: Efficiency and spatial effects of local governments and citizen action. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 89, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Feo, G.; De Gisi, S. Domestic Separation and Collection of Municipal Solid Waste: Opinion and Awareness of Citizens and Workers. Sustainability 2010, 2, 1297–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).