Abstract

Payments for ecosystems services (PES) can promote natural resource conservation by increasing compliance with environmental laws. Law enforcement and PES proponents assume that individuals make decisions about compliance based on expectations of gains, likelihood of being caught in non-compliance, and magnitude of sanctions. Brazil’s Forest Code, characterized by low levels of compliance, includes incentive and disincentive mechanisms. We interviewed landowners in the Atlantic Forest to understand their motivations to participate (or not) in a PES project, the effects of knowledge and perceptions of environmental regulations on compliance, and how both environmental regulations and PES affect land management decision-making. We found that neither expectations of financial gains nor PES payments drive behavioral change and that the perception of systemic corruption reduced compliance with environment regulations. There were important behavioral differences between long-term residents for whom the land is their main source of income and recent residents with little dependence on land-generated income.

1. Introduction

Natural conservation can be promoted both by compulsory (laws) and voluntary-mixed tools like payments for ecosystems services (PES) (e.g., [1]). PES are administered in places already subject to other environmental policies, and in many places PES provide incentives to comply with existing policies [2,3]. Regulations and incentives are important elements to signalize societal norms and expectations [4]. Mixing compulsory regulatory disincentives with voluntary incentive-based instruments can potentially improve ecosystem services and increase incomes [5]. Policy mixes or combinations can improve the quantity and quality of ecosystem services provided [6]. Evidence of the efficacy of policy mixes of PES with existing regulations has grown [7,8,9]. Most analyses are theoretical, based on little empirical evidence [10]. This study contributes to this literature using qualitative data that reveal facets of landowner decision-making about compliance with existing environmental laws and participation in PES programs. We used a case-study to investigate how forest conservation instruments using incentives and disincentives influence land use decisions.

Environmental behaviors may result from interactions between emotions, attitudes, beliefs, identities, knowledge, worldviews, and values embedded in social and cultural contexts combined with skills and opportunities to act [11,12]. Environmental behaviors are all types of behavior that change the structure, composition, function, or dynamics of ecosystems [13], therefore, pro-environmental behaviors refers to behaviors that harms the ecosystems as little as possible, or even benefits the environment [14]. Three broad approaches characterize our understanding of behavior change. Value-belief-norm theory attributes behavior change to an individual’s underlying beliefs, norms, and values [13]. The theory of planned behavior examines the influences of attitudes about a behavior, perceived judgement of behavior to people important to the actor, and perceived control over the behavior [15]. Rational choice theories treat behavior as an outcome of the individual’s effort to maximize benefits from the behavior [16].

PES programs assume that monetary benefits encourage environmental behaviors but need to recognize that non-financial incentives can exert great influence on participating in PES programs [17]. Demographic factors are predictors of participation. Higher income and educational levels [18,19], older heads of households [20], and land characteristics like size and proximity to the project headquarters [21] predict increased PES participation. Motivations for PES participation include intrinsic motivations for ecosystem protection [22], prosocial considerations like procedural fairness, equity and legitimacy [23], and a form of land tenure and food security [19,24]. Contract design, program flexibility, social and human capital reserves, and personal values also affect participation [19,20,25]. In contrast, participation declines if many changes in land management are required [21] and when property owners depend heavily on the land for income [26].

Like PES, public law enforcement theory assumes that individuals are likely to commit non-legal acts if the action’s expected utility exceeds the utility of acting within the law, taking into account the chance of being caught and the magnitude of likely sanctions [27]. Therefore, enforcement could shape compliance by affecting the likelihood of detection and sanctions and the severity of sanctions, which [28] call calculated motivations to comply with environmental regulations. They distinguish between normative motivations, an individual’s feeling that compliance is a civic duty, and social motivations when there is social pressure to comply. Their findings imply that normative and social motivations affect an individuals’ assessment of the utility of an act although they are often ignored in utility-based explanations of behavior.

Knowledge of what drives legal compliance and participation in PES contracts is critical to understanding how combined incentive and disincentive, voluntary and compulsory, approaches can achieve desired conservation outcomes, but the combination generates potential contradictions. For example, PES cost-effectiveness is thought to be greatest in regions with high deforestation rates or in most need of restoration [29]. However, PES payments to promote compliance in these regions could go to the worst violators of regulations and could reduce other motivations to comply [2]. Few PES studies have employed qualitative methods that provide an in-depth understanding of landowner perceptions [23,30,31] and few explore how combined incentive and disincentive instruments affect pro-environmental behaviors.

Brazil has a robust system of environmental laws and regulations (ELR) that employ disincentives for non-compliance (fines and jail terms) and incentives for compliance (e.g., PES), a combination of compulsory and voluntary tools. The Forest Code (FC), Brazilian federal law 12651 [32], is the main legal instrument dealing with protection and recovery of native vegetation on private lands [33,34]. The 1934 FC was enacted to protect riparian forest and last updated in 2012 when PES was incorporated, and amnesty granted for deforestation that occurred before 2008 [32]. The FC requires landowners to maintain natural vegetation in ecological buffer zones near springs and rivers, on steep slopes, and on hilltops (Permanent Protected Areas or PPAs). They must establish natural vegetation set-asides (Legal Reserves—LR) on a predetermined minimum percentage of their land, 20% in our study area. The FC is a potentially powerful conservation tool but has modest impacts on forest conservation due to poor compliance [35,36].

The relationships between PES and compliance with existing environmental protection laws are complex. A key goal of this research was to understand how law enforcement and PES individually and together influence environmental decision-making. We used a case study to examine (1) motivations to enroll in a PES project, (2) the role and importance of knowledge and perceptions of environmental regulations in compliance, and (3) how ELR and PES affect land management decision-making.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

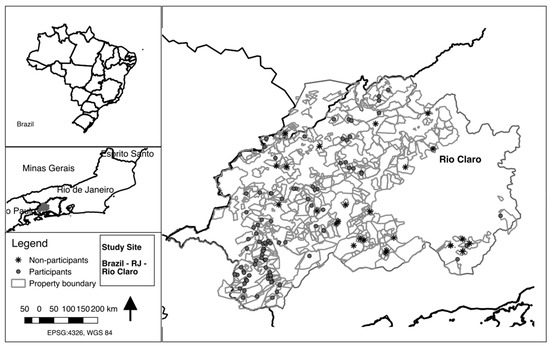

Rio Claro Municipality in Rio de Janeiro State, one of the most deforested states of the Atlantic Forest Biome in Brazil, created the PES analyzed here in 2010. Produtores de Agua e Floresta (PAF) started as a partnership of an international NGO and four Brazilian organizations [37]. Rio Claro’s population is about 18,000 [38] and the service sector and agriculture dominate the economy. It is near Brazil’s two biggest cities, 139 km from Rio de Janeiro and 270 km from Sao Paulo. Beginning in 2009, with additional public announcements to join issued in 2009, 2011, 2012 and 2015, PAF offered landowners the opportunity to participate in PAF’s program to maintain and restore riparian forests to reduce soil erosion and sustain water supplies. PAF requires participants to restore riparian forests as required by the FC, e.g., PAF pays participants to increase FC compliance.

People learned about PAF mostly when its managers visited properties and when landowners visited Rio Claro’s rural labor union or consulted with the rural extension company. A PAF local manager visited any landowner who expressed interest in joining in order to geo-reference the property and explain the requirements of PAF and the FC. PAF then mapped land use on the properties and established FC-based reforestation targets. Participation in PAF required property owners to reforest at least 25% of the area suitable for riparian forest, with an incentive to those who agreed to reforest more than the minimum. PAF payments were USD 7–29 per year per forest-covered hectare and were increased in 2013 [37]. The payments were calculated based on milk production, because a dominant land-use in the municipality is pasture for cow breeding [37]. The expansion of pasture is an important deforestation driver in the region.

Property owners who signed PAF contracts pledged to suspend current use of areas allocated to reforestation and PAF assumed the costs of reforestation. PAF’s managers designated areas for active restoration by preventing fires, excluding cattle and planting trees or passive restoration by protecting existing forest. Contracts were valid for two years without penalty for early withdrawal. As of July 2017, 67 participants owning 78 properties collectively agreed to maintain 4134 ha of forest and to reforest an additional 520 ha ([39]; Figure A1—Appendix A). In 2017, the total number of landowners in Rio Claro was 499 [40], and PAF included about 14% of landowners in the municipality.

2.2. Methodology

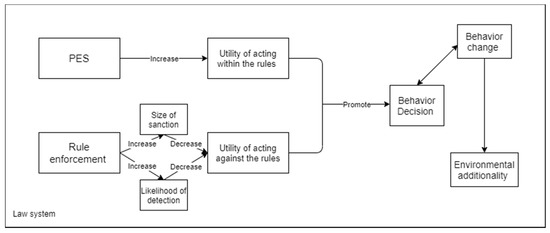

We compared perceptions of landowners who participated in PAF with those who did not. We investigated perceptions regarding connections between PAF participation and compliance with environmental regulations, particularly the FC. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual connections between the theoretical assumptions of PAF and those of law enforcement and incorporates a concept that the utility of a behavior goes beyond purely financial motivations. We define behavior decisions as the environmental management practices reflecting on land-use; and behavior change as the changes in behavior related to the existence of a regulation or a PES that result in land-cover change.

Figure 1.

Rule enforcement and payments for ecosystems services (PES) joint theoretical model.

Guandu Watershed agency (AGEVAP) provided a geo-referenced database showing property boundaries of PAF participants and areas designated for reforestation and provided descriptive information about the participants. We contacted all but six of 67 PAF participants, two of whom were unwilling to respond. Six were unresponsive to ten phone calls and two visits to their properties on different times and days. We sampled to match participants and non-participants on socio-economic traits and opportunity cost proxies (land characteristics). Owners were not in residence on many properties and we therefore used intercept sampling at other locations frequented by landowners, the local rural labor union and the local technical assistance and rural extension office (EMATER). We interviewed 19 landowners who chose not to participate in PAF and two who enrolled but dropped out of the project before receiving any payment (Table 1 provides demographic traits of the respondents in the two comparison groups).

Table 1.

Sample demographics.

We conducted semi-structured interviews (34–150 min, Table A1 provides summary of interview questions) to explore why participants chose to join or not join PAF and why people complied or not with the FC (University of Florida IRB201701354). The interviews covered four topics: (1) general information about properties and socio-economic characteristics of the landowners; (2) perceptions about forests and ecosystem services, including explanations of the distribution of forest and regrowth areas on the land; (3) perceptions of and knowledge about environmental regulations; and (4) knowledge about the project and their motivations for joining or not joining PAF [41]. Procedures were used to develop the protocol, which was reviewed by three researchers with experience in conservation and sustainable agriculture. We revised the interview guide to accommodate local language and culture after testing the interview instrument with five Rio Claro landowners of various socio-economic backgrounds.

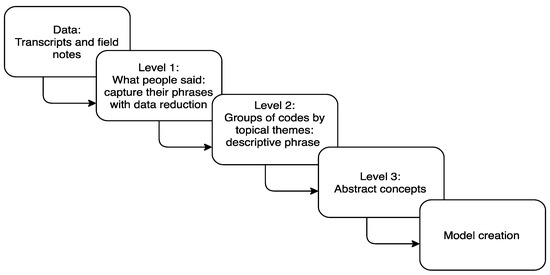

Data analysis involved four steps (Figure A2). Steps 1 and 2 are commonly used in many types of qualitative data analysis [42,43]. Step 1, topical coding, identifies specific ideas in the individual responses and captures each respondent’s comments based on transcripts of the interviews and the researchers’ notes and case summaries [44,45]. In Step 2, thematic coding, we grouped similar concepts generated in Step 1 into themes and identified relationships among them [46,47]. These larger frames helped us understand respondents’ more global views about relevant topics and to identify broader commonalities among participants than the specific concepts in Step 1. In Step 3, analytic coding created mental models of respondents’ representations of a condition or process and the relationships among the concepts [48]. We identified components in the respondents’ mental models that help explain how participants think about participation in PAF and to understand commonalities and differences among respondents’ views of the roles of the FC and PAF in their lives. We printed statements of the themes and arranged them into representations that reflect thought processes and interactions among themes. In Step 4, we assessed the degree of model agreement or “fit” with the majority of cases [46,49] and created explanatory models. Finally, we re-examined our theoretical model and modified it based on our results [50,51], creating a model that contributes to the theoretical understanding of socio-environmental systems.

3. Results

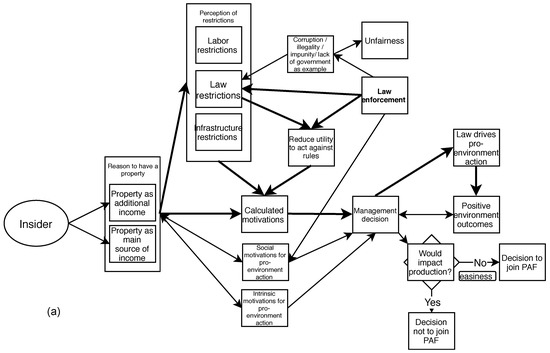

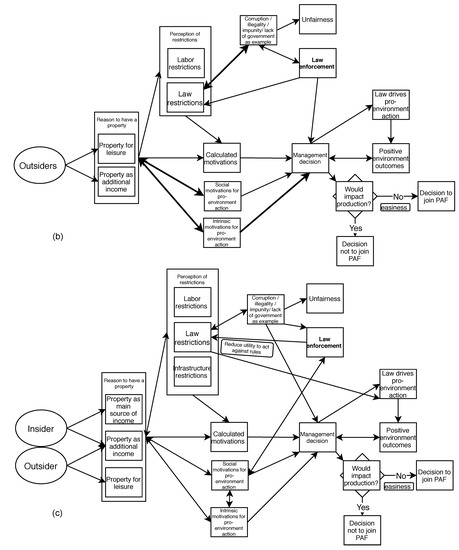

The interviews produced 267 first-level (Step 1) codes for the 59 participants and 158 for the 21 non-participants. We modified our initial theoretical model of the relationships between law enforcement, participation in PAF, and environmental additionality of PAF to reflect our findings. The explanatory models of decision-making (Figure 2) highlight (1) important distinctions between outsider and insider groups; (2) the impacts of corruption and lack of trust in government on decision-making processes; and (3) pathways that reflect added constructs in decision-making among insiders and outsiders and between PAF participants and non-participants.

Figure 2.

Behavior models in Rio Claro. Models summarizing the data analysis of participants and non-participants in PAF payment for environment services project, Rio Claro, Brazil, 2017. Thicker lines indicate most important pathways for the groups. (a) Behavior model summarizing the data analysis of insiders. (b) Behavior model summarizing the data analysis of outsiders. (c) All behavior models represented together.

Among both participants and non-participants there are two broad groups with divergent approaches to land-use decision-making. We labelled one group “insiders,” referring to landowners born in the area and raised as farmers, and the other “outsiders,” property owners with non-agricultural backgrounds. An individual’s background affects land use decision-making and objectives for property management. We henceforth distinguish between insiders and outsiders because it was the most consistent distinction among respondents, including differences between PAF participants and non-participants. There were more outsiders among the sample of participants (61%) than that of non-participants (29%). Many PAF participants were relatively wealthy and well-educated, and included large landholders who lived in urban areas and did not rely on farm income. We built models for insider participants, outsider participants, insider non-participants, and outsider non-participants (Figure 2a–c).

The insider–outsider groups differ fundamentally in their reasons for owning property in the area. Insiders, both participants and non-participants, use their property mainly for income whereas outsiders use it for leisure or supplementary income. Several PAF participants’ comments capture the importance of income: “We already worked in the rural area, then there was an opportunity to buy a property and we did it… We want to keep using the property for our family livelihood” (PAF11, male, 79-year-old insider). Insider non-participants shared similar ideas. For example, one said: “All that we obtained (could buy) in life came from this property” (N1, female, 49-year-old insider). Another said: “I like to do what I do, the necessity made me like it. I was born in a rural area and do not know how to do anything else” (N3, male, 50-year-old insider). Outsiders, in contrast, sometimes justified the way they thought about their property by emphasizing their non-rural backgrounds: “I do not perceive any drawback from having forest in my land because I do not depend on my property [for a living]” (PAF22, male, 65-year-old outsider). Another participant bought the land to conserve forest (PAF64, male 90-year-old outsider). Outsiders often mentioned that their family histories were not related to the rural lifestyle. “My father was an intellectual, not a farmer. I was raised in an apartment, but I always desired a rural life so I moved to the countryside” (PAF68, female, 67-year-old outsider). Another said: “My goal is to have a property that pays for itself because now I have to use resources from other sources of income to keep the farm” (PAF79 male 54-year-old outsider). Insiders typically used their land to generate income, whereas outsiders used it for leisure but were not averse to using it to generate income.

3.1. Motivations

Intrinsic pro-environmental motivations and the ease of joining largely drove individual landowners’ decisions to join PAF and economic motivations and barriers to joining were the main reasons non-participants did not join. Financial gain was not the main reason for joining for most PAF participants. Over 80% of participants said that they would participate without the money although they commented that: “Any extra money is always good” (PAF50, Male, 54-year-old outsider). For outsider non-participants, an emerging theme was “heard about it but nobody offered it directly” and some said they might join if asked. Non-participant N11 (Male 52-year-old outsider) gave a typical explanation: “We found out about the program on TV but did not look for details. We do not intend to deforest anyway, so we do not need the incentive [to conserve forest]. But if the project directly asked us to join the program, we could join.” Many non-participants outsiders said that PAF looked like a good opportunity, but that they did not trust the government. They thought that the government might stop payments once the forest grows back because forest land is legally protected. This justification was also provided by some insider non-participants when we asked about the minimum level of economic incentives that would make them join a conservation program and increase their pro-environmental behavior.

Economic motivations revealed in the interviews clearly included the opportunity costs discussed in the PES literature. For example: “Decision-making is based on what improves our situation, but we always focus on cattle because it seems to provide us more profit” (N22, male 32-year-old insider). Another said: “if I had more forest it would affect my income” (N26, male 56-year-old insider). The perception of restrictions on land use influenced economic motivations on land use decisions. Participant PAF68 (Female 67-year-old outsider) stated: “In the 1980s everyone started to plant brachiaria grass when rural laborers started to migrate to nearby cities… brachiaria spreads because it does not require much labor.” The high opportunity cost of allowing the pasture to become forest was the most common reason non-participants gave for not participating. Non-participants went so far as to describe their individual “opportunity cost math” to show that the payments were not enough and said that they would not participate because pastures are more useful than forests. Participant NP17 (male 58-year-old insider) said: “I heard PAF’s proposal, but I thought it [the payment] was too little… I could get more planting yams. And in the future, what will I leave for my children and grandchildren if I sign? It is permanent.”

Diverse ideas emerged along with these common themes. Two non-participants pointed out that the effort and cost to society to restore forest to increase water quality and availability would have no impact compared to the addressing lack of sewage treatment facilities in cities. This implies that they believed reforestation would require a major individual effort but produce little benefit for society. One respondent indicated that he would join PAF if everybody in the region did so, suggesting that a collective effort would justify the individual cost.

Enrolment of communal land by quilombolas, slave descendants, deserves special attention because community-owned and private owned land are often treated differently in PES projects. The quilombola community in Rio Claro includes about 240 people in 55 families, 85% of whom depend entirely on their land for their livelihoods. The community association decided to join PAF because they had once made and sold charcoal to the steel industry, which resulted in extensive forest degradation, and they believed that participation in an environmental project would improve their public image. When the community joined the project, its members were not aware that the project would provide payments. By the time of this study, PAF had become the main source of financial income for the association and provided members with jobs in reforestation on private properties.

ELR compliance was another motivation for PAF participation. Many participants indicated their awareness of FC requirements and believed that most landowners could comply without compromising their livelihoods. Participants expressed different perceptions of the likelihood of enforcement of environmental laws in general, even though most knew someone who had been sanctioned for non-compliance. Many perceived increased environmental awareness and law enforcement over the previous two decades.

The theoretical approach in Figure 1 suggests that sanction size and likelihood of detection would be the most important factors in reducing the utility of acting against the law. This was true in Rio Claro where many people had been jailed for deforestation and the perceived probability of getting caught was high. These conditions decreased motivation to violate this legal requirement, showing that laws can drive pro-environmental action. Nonetheless, fines were perceived as less effective than jail terms in reducing illegal actions and there is a perception that the restoration required by the FC is not enforced. Landowners understood that authorization was required to change land-use if they allowed trees to regrow. In consequence some landowners voiced the idea of a “negative opportunity cost,” willingness to pay to suppress forest regrowth even if they do not plan to use the pasture in the near future.

Corruption of environmental enforcement officers and “the government” as an institution was a predominant emergent theme that greatly affected perceptions of the fairness of environment laws. Many landowners remarked that their decision to comply with environmental regulations included consideration of the inequitable enforcement of sanctions. Many did not believe that enforcement was equal for small and large landowners, saying that the latter could bribe officers or even influence the creation of laws.

3.2. Relationships between Themes

PAF’s modest fiscal incentives did not appear to reduce other motivations for FC compliance. One reason cited for compliance was the importance of forest, especially the hydrological benefits it provides. Participants learned about these benefits from the project, which could have increased motivations to conserve. We did not investigate changes in perception due to the project, but many landowners said that they traditionally conserved forest near springs suggesting that information from the project only reinforced their prior knowledge.

The reason for owning property influences how landowners perceive FC restrictions on land uses. Increased restrictions were widely perceived as negative because they reduce landowners’ sense of self-determination. Many insiders perceive FC compliance primarily as a restriction, one saying, “The forest is untouchable” (PAF 78, male, 65-year-old insider) and many felt that part of their property was “not really theirs to manage.” PAF does not include landowners in choosing species for reforestation. Some argued for change because some landowners prefer species for aesthetic value or potential income generation.

Labor constraints influenced land-use decisions. One non-participant insider said that: “There are not enough people to work the land. Our children grew up and left and we can’t afford to hire other people” (N10, male, 78-year-old insider). Some outsiders who initially planned to use the property as a source of income pointed out that labor availability limited this option: “In the beginning I was thinking about raising cattle, but since it is hard to find labor in the region, I gave up” (PAF51, male 66-year-old outsider). Other limitations also emerged: “The worst here are the roads. It’s hard to maintain production or any other activity” (PAF05, male 73-year-old outsider). In contrast, some landowners who valued their land for leisure did not want paved roads “because it would make me lose my privacy” (PAF40, male 73-year-old outsider).

Intrinsic and social motivations for conservation indicate reasons for owning property which influences motivations for conserving forest. Conserving forest and its aesthetic value and a desire to fulfil a family dream were motivations for owning land. Owning property seemed to strengthen intrinsic and social motivations for pro-environmental action. Respondents frequently mentioned beauty and tranquility as forest ecosystem services, discussed their desire to maintain forest for future generations or for wildlife, and indicated that maintaining forest was a lesson that their family had learned. Intrinsic motivations prevailed among outsiders whereas insiders were more driven by perceived economic benefits.

Use of PES in a policy-mix context may be problematic. Most of PAF’s money went to a minority of landowners with large properties [52] even though most PAF participants have small holdings by Brazilian standards. This bias has implications for project effects on real and perceived equity. Some participants said that they received meagre benefits from PAF while other people received substantial benefits to protect forest that law requires them to preserve. PAF sometimes describes its accomplishments by the number of participating properties, but care is needed when using this measure because PAF does not have a minimum property size requirement. Four participants owned < 1 ha and three < 5 ha. Further, in addition to PAF payments, five landowners received a second and much larger PES payment as an incentive to transform part of their land into a Private Reserve of Natural Heritage (RPPN from Portuguese acronym), a category in the national protected area system.

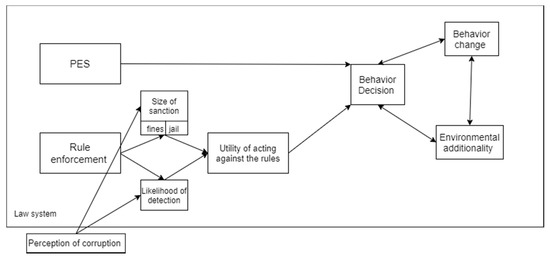

We modified our theoretical model to reflect findings (Figure 3). For the Rio Claro context, the type (fines or jail) of sanction resulted in different decreases in utility of acting within the rule, where jail reduced illegality, but fines seems to have no or small implications in the decreased motivation to violate legal requirements. The perception of corruption is important to explain this and also how people perceive the fairness, size of sanctions and likelihood of detection, therefore influencing causal path of rule enforcement to reduce utility of acting against the rules. Furthermore, in Rio Claro PES enrolment was not mainly motivated by increasing compliance with the rules. So, although it does increase the utility of acting within rules, we removed this box from the model. Finally, we highlighted the feedback loops between behavior decision, behavior change and environmental additionality.

Figure 3.

Modified law enforcement and PES joint theoretical model based for Rio Claro, RJ, Brazil, 2017.

4. Discussion

4.1. Contributions to the PES Literature

Although transaction costs accrue substantially when PES projects include numerous smallholders [53], PAF was accessible to landowners large and small, poor and wealthy. In contrast to some PES projects [19,54,55], property size did not seem to influence the likelihood of participation in PAF. Our finding that outsiders were prevalent among PAF participants is similar to [17] findings for Costa Rica. Compared to non-participants, smallholders and larger landowners enrolled in a PES tended to be older and wealthier, had access to non-farm salaries, and participated only marginally in agriculture. In contrast, PAF participants included some insiders who depend on farm income and had limited formal education. Our interviews reflect findings by [56] that willingness to participate was negatively associated with availability of family labor and with the fear of changing production patterns characteristic of low-income, farm-dependent landowners.

The data we collected support findings that perceptions toward conservation and intrinsic environmental motivations drive participation in PES [19,23,57,58,59]. Other researchers [60,61] who question the rational choice theories that underlie many PES schemes report that the opportunity cost principle is often only loosely relevant. Nevertheless, similar to findings by [62] in Mexico, many PES participants “like forest but also like cash” and the payments provided an important additional incentive. PAF participants’ recognition of the importance of forest for essential environmental services, especially hydrological, could stimulate long-term behavioral changes and promote more conservation [63].

Monitoring and enforcing conditionalities of pro-environmental behavior that were agreed upon in exchange for enrolment in PES are necessary incentives for effective conservation [64]. PAF monitors compliance but lacks clear protocols for dealing with non-compliance. PAF’s contracts state that non-compliant landowners can receive only partial payments or be excluded from the program, but as of 2018 no PAF participants were penalized for non-compliance (AGEVAP, personal communication). PES implementers often tolerate some non-compliance and only one-fourth of PES projects described in the literature report sanctions for non-compliance [64]. The authors in [64] point out that local politics and budgetary constraints often have greater influence on PES enforcement than budgetary constraints. This appears true for PAF, which tolerates some non-compliance in recognition of the time needed to build trust with participants.

4.2. Insights from ELR

Landowners’ personal financial gains can compensate for their potential financial losses from illegal actions, which influences the behavior decision of whether to deforest or suppress forest regrowth in ecological buffer zones. This situation reveals an inherent tension between individual and social assessments of ecosystem service value. Many factors affect the likelihood of collective action when faced with such social dilemmas [65], but enforcing regulations is often critical insofar as it influences individual perceptions of costs [66,67]. PAF participants and non-participants were aware of people being fined or jailed for deforesting, but perceived differences in the sanctions. People feared jail and would avoid deforesting but did not fear sanctions for failure to reforest. A study in the Amazon Biome found that only 6% of the Rural Environmental Registry (CAR) registered producers were taking steps to restore illegally cleared areas on their properties; and suggested that full compliance with the FC offered few economic benefits from the landowner’s perspective [68].

Rio Claro property owners who depend on land for their livelihood value cleared land more than forest. As noted earlier, some landowners pay the “negative opportunity cost” to suppress forest regrowth to protect their descendants’ ability to make decisions about how to use the land in the context of tough enforcement of prohibitions on deforestation. This example shows how policies may intersect with behaviors and norms to result in unanticipated outcomes [69]. This viewpoint may also reflect the higher selling price of cleared land, which could be a vestige of decades of governmental incentives to clear land in Brazil [70]. Cleared land in Rio Claro sells for two to five times more than forested land despite its out-of-compliance status. Riparian cleared land would sell for less than forested land if the FC were enforced because the purchaser would have to pay for reforestation. The value of cleared land could also reflect a cultural tendency of Latin Americans to value pasture over forest [71].

The nature and magnitude of the effects of political corruption on compliance with environment regulations remains understudied [72] but corruption was an important theme in many interviews. Perceived corruption and unfairness, such as large landowners having fewer “real” obligations for legal compliance, are recognized as faults in the Brazilian legal system. Perceptions of corruption, unfairness, and impunity help explain low levels of compliance with environmental law in Rio Claro. Similarly, [68] highlighted that the perception of impunity severely weakens environmental policies to control deforestation in the Amazon. We therefore concur with [3] that incentive instruments cannot offset weak governance resulting from limited state capacity to enforce or corruption. Loss of respect for and confidence in environmental laws generated by perceived corruption deserves more attention.

4.3. Implications Emerging from the Empirical Findings

Brazil has extensive experience with diverse approaches to environment protection, PES being among the most recent. As in many regions where PES interventions are implemented, our study occurred in an area characterized by weakly enforced environmental regulations [73] but that is of tremendous importance to conservation [74]. The authors of [75] hypothesize that landowners often burn or cut early successional growth even when they do not need the area for production to avoid restrictions in the future. In this setting, PES could help tip the balance toward allowing natural forest regeneration. It would be useful to examine how price differences between cleared and forested land in Brazil have evolved in response to perceptions of enforcement of the FC.

Debates about the relative benefits of disincentive and incentive policies seem to be moving toward policy mixes [75]. It is crucial to understand how actors, who can alter the services provided, perceive the instruments and their interactions. The use of a pragmatic carrot-and-stick approach can promote pro-environmental behaviors in the context of weakly enforced laws [76], help reduce the perception that regulations are unfair, and increase compliance. A clear assessment of the time needed to transition from response to incentives to voluntary legal compliance is important because PES cannot compensate indefinitely for regulatory insufficiencies [2]. Furthermore, PES interventions could exacerbate inequalities, especially where income from land use is highly asymmetrical [77].

Enforcement is important for any regulation to be effective and FC enforcement should apply to restrictions on land use and to the conditionality of PES. Calculated and normative motivations as described by [28] seem to explain compliance intentions in Rio Claro, but lack of trust in the government and perceptions of corruption affect landowner decisions. Regulations like the FC can reduce landowners’ sense of self-determination and diminish their intrinsic motivation to protect the environment [78]. Similarly, funds provided by PES can both reduce intrinsic and increase extrinsic motivations for conservation [22]. Moreover, other researchers [79] argue that the focus on rewards and punishments has led to neglecting other ways of supporting smallholders to achieve conservation objectives in the longer term. They suggest focusing on local heterogeneities and capacities and the need to promote trust, altruism and responsibility towards others and future generations.

PES and ELR approaches can be justified to the extent that landowners generate positive externalities through conservation practices that deserve rewards and generate negative externalities through deforestation that justify penalties. However, the approaches differ fundamentally with regard to who pays the costs of conservation. The limited funds for conservation could exacerbate inequities if the incentive approach primarily benefits a few large landowners. It is important to understand how PES influences the cost-effectiveness of achieving desired conservation outcomes in diverse contexts. In Rio Claro, PAF did bring environmental additionality but at a relatively high cost [80]. If law enforcement is stringent and the legal system perceived to be just, enforcement alone will motivate pro-environmental behavior, and PES payments are unnecessary. If these conditions do not hold, PES payments should cover opportunity costs and sanctions should be harsh enough to deter non-compliance. PES substitutes for environmental regulation and should target areas with the highest potential service values with high PES payments and enforced conditionality. Using PES to achieve environmental goals where legal restrictions are enforced is inefficient at best. An alternative would be to use PES to increase equity by PES payments sufficient to offset costs for poor people who could not otherwise comply. It may be fruitful to treat PES as a transitional mechanism to generate behavioral change when the primary objective of payment is to promote compliance with environmental regulations, but PES is likely not a permanent solution to non-compliance. The authors of [4] argued that environmental benefits that arise as a result of compensation or regulations require an on-going flow of payments or compliance checks and, if removed, there is a risk that these benefits will disappear.

5. Conclusions

Three major conclusions emerged from our study. First, the differences between insiders (farmers, mostly born in the area) and outsiders (non-farmers) are more important than the distinction between participants and non-participants regarding compliance with the Forest Code and willingness to conserve forest or reforest. Second, cost–benefit calculations are not the primary driver of decisions about PES participation. Most PAF participants were outsiders whose pro-forest decisions were largely based on perceived intrinsic values. Insiders, in contrast, were more likely to invoke financial considerations in their decision-making. Third, perceptions of systemic corruption in the enforcement process contributes to respondents’ not treating environmental regulations as important in decision-making. PAF’s design does not generate the maximum potential benefit from interactions between the incentive and disincentive instruments within the FC because of failure to recognize these three factors. Instead, PAF serves more as compensation for prior pro-environmental behaviors than as an incentive for behavior change.

Perception of the probable stability and longevity of any existing set of regulations, particularly those that limit landowners’ ability to make land management decisions, have a critical effect on compliance. Landowners often do not allow forests to regrow and refuse to participate in projects that require reforestation when they expect that reforested areas can never be cleared. Worse yet is when perceptions of in perpetuity loss of the right to clear forest provokes aggressive anticipatory deforestation.

Efforts to save and restore ecosystems require a deep understanding of the efficacy of the tools employed to encourage pro-environmental behaviors. Many instruments are potentially useful and can sometimes be combined beneficially. Nonetheless, limited funds for conservation require decisions about which instruments to employ. These decisions should be based on an analysis of likely interactions between context and the underlying assumptions needed for each type, design, and implementation of instrument to produce the desired results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.O.F., M.S. and F.E.P.; methodology, A.C.O.F. and M.S.; data collection A.C.O.F. and field assistance, analysis, A.C.O.F. and M.S.; writing, A.C.O.F., M.S. and F.E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A.C.O.F. was funded by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) of Brazil for a PhD scholarship, this research was also funded by a Graduate Student Summer Fellowship from University of Florida’s Biodiversity Institute, and by a Field Research Grant from University of Florida Tropical Conservation and Development.

Acknowledgments

A.C.O.F. thanks the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) of Brazil for a PhD scholarship, University of Florida’s Biodiversity Institute for a Graduate Student Summer Fellowship, and University of Florida Tropical Conservation and Development for a Field Research Grant. We also thank all the people that helped us in the field and that were willing to participate in the research, without them this research would not have been possible. And reviewers for their time and comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Detailed Coding Procedure

We created a case file for each interview. A field assistant transcribed the interviews. The researcher paid close attention to the respondent during the interview and noted change in tone, pauses or other signs of hesitation, emotion-laden responses and other non-verbal cues to meaning. Case files were comprised of both the transcriptions and the notes taken by the researcher. The data analysis process began with coding the open response sections of the interviews. A code assigns a summative or evocative phrase that captures the essence of a respondent’s comments to a question [81]. The objective of coding is to allow the researcher to identify patterns in an individual’s responses and across cases, in this case patterns that may explain why landowners participated or did not participate in PAF and complied or did not comply with Forest Code.

Data analysis involved four steps, three levels of coding (Figure A2) (1) topical, (2) thematic and (3) analytic, followed by (4) development of an overall conceptual model. The analysis process commenced with identification of specific ideas or themes that emerged from the data in response to each question and topics in the interviews. We used both the transcription and case summaries to capture the information provided by participants, a commonly used procedure to ensure reliability in coding [44,45,82,83]. We then grouped the themes identified into larger conceptual frames that reflect similar themes and relationships among themes that emerged from the interviews [46,47]. These larger frames helped us understand respondents’ views about multiple topics. Even if subconsciously, human beings create these larger mental models or scaffolds in many aspects of their lives [48,84,85]. This part of the data analysis process allowed us to identify at least a portion of the participants’ mental models as they considered participating in PAF and to understand the commonalities among respondents’ views of the roles of the Forest Code and PAF in their lives. Our main goal was not to provide statistical generalizations, but to characterize different perspectives among the landowners. Our final step in data analysis was to develop a model, based on an analysis of the individual codes, the emerging themes, and the interactions between them. We printed all themes and emerging themes and manually arranged them into a model that reflects the learning process. After we checked for agreement of models with the majority of cases (as per [46]), we also highlighted potential findings from outliers.

Topical or descriptive (Level 1) coding assigns a code to the specific comments made by each respondent ([81]: pp. 83–92). Coding proceeded topic by topic or question by question for each respondent, and codes were developed independently for each comparison group, participants and non-participants in PAF. However, topical codes do not necessarily include only the specific subjects posed in the researcher’s questions. It is common for respondents to make comments that are only tangentially related to a question or are seemingly not related at all. These emergent topics are also coded and often provide insights into the respondent’s ways of thinking about a topic or the associations a topic brings to his/her mind. Topical codes are highly specific. For example, several participants commented on problems associated with labor. Some commented that their children leave the farm while others commented that there are few people willing to work as agricultural laborers for hire in the region due to low wages. These comments illustrate two aspects of the topical coding process. First, we did not ask specifically about labor. These comments were made in response to questions about other topics and hence they were emergent comments. Second, the comments varied, some were concerned with out-migration and others lack of local labor.

Thematic (Level 2) coding groups the specific comments that emerge in topical coding into broader associated categories or themes ([81]: pp. 218–223). Thematic coding typically reduces the number of codes substantially because the comments made are grouped by the broad topics included in the interview. Emergent topical codes are also grouped when possible. For example, a thematic code that emerged in this study had to do with the effort involved in meeting bureaucratic requirements. Three topical codes were identified in the first level of coding: (1) the effort associated with land registration, (2) the wasted time spent dealing with fines related to inappropriate land use, and (3) anticipated time and effort required to join PAF. Comments of the first two types were made by all respondents whereas comments about joining PAF were made only by non-participants in PAF. The overarching thematic code for all three of these specific topical comments is bureaucratic efforts for land management. Thematic coding initiates the process of analyzing the data, moving beyond description to understand how respondents organize experiences and concepts into individual mental models.

Analytic (Level 3) coding ([81]: pp. 223–234) develops specific models of the components included based on both the topical conceptualization of the researcher and emergent patterns that group the specific mental models expressed by respondents. These models include both abstract concepts and proposed explanatory relationships between those concepts. The proposed relationships, typically indicated by flow lines between concepts, are referred to as “propositions” because they are proposed explanations of the relationships among complex concepts. These models focus on specific components of the overall theoretical basis of the research. We developed four of these specific models in this study. For example, we based one model on the socio-economic concepts related to participation in PES described in the literature [86,87,88] and emergent concepts such as “insiders and outsiders” in our study.

The overall conceptual model we developed draws upon the individual models developed in Level 3 analytic coding to create a model that we offer as a proposed theory-based explanation of how the participants in PAF and non-participants perceive the connection between payments for ecosystems services and legal compliance. Like most explanatory models, this model contributes to theory by incorporating the mental models of respondents to create a more robust understanding of a complex decision-making process. Table A2 provides first-level participant codes, Table A3 shows first-level non-participant codes, Table A4 displays themes from participants and non-participants in PAF; and Table A5 presents themes decision process, i.e., the process of combining themes together to be included in the models.

Figure A1.

Map of properties registered in CAR in Rio Claro, 2017.

Figure A2.

Qualitative methods summary. Summary of quantitative data analysis process. The data acquired were organized into transcripts and field notes, first-level coding created condensed, descriptive phrases that summarized the ideas expressed, level two coding grouped the individual level one codes into themes, and level three coding produced abstract concepts to allow creation of models summarizing the findings.

Table A1.

Summary of interview questions.

Table A1.

Summary of interview questions.

| Objective | Open-Response Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. General information about property(ies) management |

|

| 2. Landowners’ perception about forests, ecosystems services and reasons for the distribution of forest and regrowth areas on their land |

|

| 3. Landowners’ motivations for joining or not PAF |

|

| 4. Landowners’ perception and knowledge about environmental legislation |

|

Table A2.

First-level participant codes, by topic for a sample of 59 respondents in Rio Claro, Brazil, 2017.

Table A2.

First-level participant codes, by topic for a sample of 59 respondents in Rio Claro, Brazil, 2017.

| Topic | First-Level Code | Idea It Refers | Codes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Reasons for having the land | Property for leisure | Uses the property for leisure activities | PAF82, PAF71, PAF33, PAF18, PAF45, PAF12, PAF77, PAF21, PAF17, PAF61, PAF22, PAF23 |

| Property to share with friends | Wanted the property to have a place to enjoy with friends | PAF51 | |

| Desire to pursue a rural lifestyle | Identifies with rural life | PAF82, PAF23, PAF05 | |

| Property as investment | Property is a way of creating savings to meet future necessities in a period of instability in the country | PAF82, PAF68, PAF56, PAF17, PAF25, PAF68, PAF42, PAF81 | |

| Family had the property for leisure | Family had this property before the current owner and used it for leisure | PAF40, PAF56, PAF50, PAF42, PAF45, PAF08, PAF29, PAF32, PAF79, PAF70 | |

| Family livelihood related to property | Property accounts for a big part of family’s income | PAF71, PAF33, PAF50, PAF11, PAF16, PAF47, PAF59, PAF72, PAF78 | |

| Property for cattle ranching, | Has the property to raise cattle | PAF78, PAF86, PAF01 | |

| Family already managed the property | Plans to keep the activity the family had before | PAF78, PAF86, PAF66, PAF10, PAF04, PAF72 | |

| Looking for escape from the city | Wanted to have an alternative to the busy city lifestyle | PAF86, PAF36, PAF89, PAF37, PAF28, PAF18, PAF88, PAF12, PAF68, PAF36, PAF44, PAF61 | |

| Family likes the region and property | Family demonstrates affection for the place | PAF56, PAF54, PAF19, PAF05, PAF12 | |

| Property as inheritance | Leave something for the family | PAF88, PAF12, PAF68, PAF36, PAF63 | |

| Property as additional income source in hard times | Can sell cattle when the family needs money | PAF56 | |

| Family dream | Family member always wanted a property | PAF37, PAF54 | |

| Retirement plan | Bought it thinking about using it when retired | PAF17, PAF81, | |

| Raise horses | Desired to have an income from horses | PAF73 | |

| Housing | Family uses mainly for residency | PAF32, PAF31, PAF14, PAF34 | |

| Inspiration | Bought to have inspiration and creativity to write | PAF67 | |

| Forest conservation | Bought already thinking about forest conservation | PAF64, PAF51 | |

| 2. Aims for the land | Property for forest conservation | Wants to maintain the property for forest conservation | PAF40, PAF88, PAF66, PAF64, PAF51, PAF54, PAF31, PAF67 |

| Property in a park area | Acknowledges the limit use of the property because it is within a protected area | PAF78 | |

| Property for family livelihood | Aims to provide for the family with property | PAF78, PAF16, PAF72, PAF78 | |

| Aims to improve the property | Wants to get more profitability from the property | PAF78, PAF86 | |

| Labor restriction changed the aim of the property | Had to change the aim due high labor cost | PAF68, PAF36, PAF55, PAF01, PAF58, PAF21 | |

| Cattle | Desire to have cattle related activities | PAF56, PAF42, PAF54, PAF57 | |

| Use for leisure | Use the property for leisure | PAF33, PAF77, PAF21, PAF45, PAF12, PAF04, PAF08, PAF74, PAF70, PAF61 | |

| Use for leisure because cannot change it | The law does not allow to change the land cover, so uses for leisure | PAF58 | |

| Aging | Getting older and reducing the work load | PAF37, PAF58, PAF11 | |

| Difficulty in access | Moved from other property to be closer to the city/school | PAF03 | |

| Additional income | Aims to use the property to contribute in the income | PAF18, PAF45, PAF10, PAF73, PAF63, PAF14, PAF05, PAF81 | |

| “Rents” for maintenance | Let people use the property in exchange for work in maintenance of the property | PAF21, PAF08 | |

| Tourism | Aims to implement a tourism related business | PAF06, PAF54, PAF25, PAF61, PAF05, PAF57 | |

| Corruption prevented to implement economic activity | To implement the desire activity would have to “buy” license | PAF42 | |

| Tried activities that did not work | Gave up of activity in consequence of perceived failure in generating income | PAF42, PAF73, PAF81, PAF23 | |

| Bar in the property | Has a bar to complement income | PAF34 | |

| 3. Reason for maintaining forest | Maintain forest because it is not allowed to cut | Clearing forest is not allowed | PAF82 |

| Maintain forest because of water | Believes forest is important for water resources | PAF82, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF50, PAF03, PAF17, PAF10, PAF54, PAF23, PAF57, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Maintain forest because of animals | Maintain forest for the sake of animals | PAF82, PAF37, PAF50, PAF51, PAF10, PAF04, PAF08, PAF22, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Maintain forest because of future generations | Maintain forest for the sake of future generations | PAF82, PAF89, PAF66, PAF51, PAF31, PAF34, PAF67 | |

| Environmental awareness | Maintain the forest because s/he considers her/himself to be an environmentally conscious person | PAF71, PAF68, PAF36, PAF50, PAF18, PAF17, PAF12, PAF51, PAF10, PAF57, PAF31, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Enjoys the forest | Maintain forest because s/he likes the forest | PAF68, PAF36, PAF40, PAF56, PAF33, PAF50, PAF18, PAF42, PAF10, PAF22 | |

| Obligation as a citizen | Protecting forest is a moral requirement, wanted to be an example for society | PAF40, PAF51, PAF54, PAF57, PAF31 | |

| Wood source | Uses wood extracted from the forest | PAF86, PAF89, PAF03, PAF17, PAF72 | |

| Law required | The law requires forest maintenance | PAF78, PAF86, PAF12, PAF25 | |

| Too small almost does not have forest | PAF28 | ||

| Religion | God thinks it is important to conserve, nature is God | PAF68, PAF18 | |

| Labor expenses | It is too expensive to pay labor to deforest | PAF10 | |

| Family teaching | The family already conserved the forest and wants to pass on this lesson | PAF31 | |

| 4. Reasons to restore forest | Trees are beautiful | Planted Ipes (Handroanthus) because believes they are beautiful or other trees | PAF82, PAF57 |

| Recover a degraded area | Wants to reforest to recover a degraded area | PAF71, PAF56, PAF66, PAF10, PAF63 | |

| Areas around spring | Reforestation is allowed because was around springs, or recover a spring | PAF78, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF18, PAF63 | |

| Land abandonment and areas that were not being used | Was not using some areas and the forest grew back | PAF86, PAF12 | |

| Changed production for tourism | The forest grew back when changed focus of the property | PAF86, PAF36 | |

| Trees in the fence line with neighbors | Planted trees in the fence line with neighboring property for more privacy and/or not moving the fence | PAF89 | |

| Off-site mitigation | Received money from a company to perform an off-site mitigation to compensate and environment damage | PAF50, PAF54 | |

| Reduce the problem with fire | Believed that the forest existence could reduce the problem and fear of having fires too close | PAF25 | |

| Shade for cattle | Allowed tree regrowth in some spots to provide shade for the cattle | PAF72 | |

| 5. Perceived benefits of forest | Believes forest in important for water | Relates forest to water availability and provision and to high humidity | PAF82, PAF56, PAF37, PAF33, PAF50, PAF03, PAF28, PAF18, PAF88, PAF77, PAF21, PAF17, PAF06, PAF42, PAF45, PAF66, PAF12, PAF10, PAF04, PAF08, PAF25, PAF22, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF63, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 |

| Reforestation does not increase water availability | People normally think reforestation increases water availability, but reforestation does not increase water availability | PAF64 | |

| Erosion control | Forest reduces the impact of rain on the soil | PAF28, PAF42, PAF45, PAF64, PAF04 | |

| Believes forest in important for conservation | Believes forest conservation and biodiversity are benefits | PAF82, PAF50, PAF40, PAF03, PAF18, PAF88, PAF42, PAF51, PAF08, PAF25, PAF22, PAF14, PAF31, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Clear Air | The air is cleaner, “purer,” near forest | PAF86, PAF50, PAF17, PAF45, PAF12, PAF55, PAF25, PAF22, PAF14, PAF31, PAF63, PAF34, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Breeze | Temperature and breezes are nicer near forest | PAF86, PAF37, PAF42, PAF45 | |

| Peace and beauty, stress relief | The forest provides a feeling of peace and encourages contemplation | PAF50, PAF12, PAF42, PAF51, PAF08, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Society collaboration | Feels that s/he is collaborating in the society | PAF17, PAF51, PAF23, PAF67 | |

| Climate more stable near forest | The forest reduces variations in temperature and humidity | PAF77, PAF17, PAF21, PAF45, PAF66, PAF51, PAF55, PAF10, PAF04, PAF25, PAF34 | |

| Tourism | The forest brings tourism to the region | PAF45 | |

| Firewood | The forest provides firewood | PAF10, PAF22, PAF57 | |

| Payment | The PAF payment is a benefit from forest | PAF08 | |

| Work inspiration | The forest inspires composing music | PAF67 | |

| Better soil close to the forest | PAF72, PAF40 | ||

| 6. Perceived drawbacks from forest | Nothing for heirs | Not drawback, but if they only left the forest to grow back, the heirs would have less land value | PAF64 |

| Not at all | Interviewee demonstrated a strong denial of drawbacks of forest presence | PAF82, PAF56, PAF21, PAF12, PAF51 | |

| No drawbacks, but fencing incurs costs | Interviewee specifically mentioned no drawbacks but | PAF40 | |

| Lost is land for production | The forest occupies an area that could be used for production | PAF78, PAF86 | |

| Problems with hunters or palm extractors | The forest attracts people to hunt and extract palm | PAF36, PAF86, PAF56, PAF42, PAF45, PAF10, PAF54, PAF01, PAF31, PAF19, PAF67, PAF81 | |

| Conflict with neighbors | Neighbor allows cattle to cross into others’ property, which generated conflicts | PAF23 | |

| Too many restrictions on use of forest land | The law places too many restrictions on forest land use, reduces the options for landowners | PAF23 | |

| The landowner incurs more responsibilities with forested land than with pasture | If the pasture burns, nobody says anything, but if the forest burns the landowner is fined | PAF40 | |

| Humidity | Does not want forest near the house because it makes it too humid | PAF25 | |

| 7. Land management resulting in land use changes | Deforested in the past for cattle | Deforested to increase area for cattle | PAF78, PAF86, PAF89, PAF72 |

| Let forest regrow | Forest grew back after abandonment of production | PAF68, PAF36, PAF37, PAF18, PAF66, PAF45, PAF12, PAF64 | |

| Was pasture when arrived | Reported that when arrived in the property everything was pasture and now there is a lot of forest | PAF50, PAF51, PAF67 | |

| Transformed property in condominium | Divided and included many houses | PAF25, PAF55 | |

| 8. Learned about PAF | Neighbors participating | Found out about the project because neighbors were participating | PAF82, PAF71, PAF56, PAF03, PAF77, PAF57, PAF67 |

| Surprised to be accepted in PAF | Has a lot of forest, so did not understand why they would be accepted in a PES project | PAF71 | |

| Part of COMDEMA | Member of the municipality environment committee | PAF40, PAF50 | |

| TV | Saw information about the program on television | PAF78 | |

| Local institution | EMATER Rio Claro (Rio Claro’s technical assistance and rural extension company), rural labor organizations and/or environment secretariat provided information | PAF86 | |

| Created the project | Was part of the group that created the project | PAF68, PAF50 | |

| Project went until property | The project staff visited the property to provide information | PAF89, PAF03, PAF21, PAF45, PAF51, PAF10, PAF04, PAF01, PAF73, PAF08, PAF22, PAF34 | |

| Friend or family | A friend of the family informed him/her about the project | PAF66, PAF12, PAF31, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Looked for help to restore to fulfil environment regulation | Was informed about PAF while looking for ways to fulfil an environment requirement for building a condominium | PAF55 | |

| 9. Motivation to participate | Everybody around was participating, so joined too | Joined the project because the neighbors were also participating | PAF82, PAF56, PAF89 |

| To protect springs | Joined the project to protect or increase protection for springs | PAF82, PAF56, PAF03, PAF21, PAF06, PAF66, PAF12, PAF57, PAF81 | |

| For help with fencing | Joined the project for the help with fencing | PAF82, PAF56, PAF37, PAF21, PAF51, PAF73 | |

| Would have joined without the money | Would have joined without the money | PAF82, PAF56, PAF89, PAF03, PAF77, PAF21, PAF51, PAF73, PAF57 | |

| Already was doing what was needed and would get money for it | Joined the project because already had forest and would get money by joining | PAF82, PAF33, PAF50, PAF67 | |

| No reason not to join | Did not see any reason not to join; was already doing required practices | PAF50, PAF45, PAF51, PAF57 | |

| Sponsorship of increase in protection | The program provides sponsorship to increase the protected area on the property | PAF40, PAF77, PAF21 | |

| Money | Joined because of payment | PAF78, PAF89, PAF33, PAF10, PAF23, PAF19, PAF67 | |

| No negative impact | Joined because the areas that would go into reforestation would not reduce agricultural production | PAF78, PAF21, PAF06 | |

| Desire to restore areas | Desire to protect areas around river because believes the rivers in the world are drying out; protect areas experiencing erosion | PAF86, PAF42, PAF66, PAF25, PAF63, PAF34, PAF81 | |

| Money attracts corruption | Almost did not join because money attracts corruption | PAF56 | |

| Project people were nice | Joined because the people that were recruiting for the project were very nice; wanted to help the project staff | PAF56, PAF89, PAF14 | |

| Avoid criminal fires and hunt | Joined because other people get to know you are in the program and then do not start fires or hunt on your property | PAF89 | |

| Avoid land invasion | Joined because of concern about land invasion and believed the project’s presence would avoid it | PAF89 | |

| Increase local environment awareness | Joined because wanted to help to increase local environment awareness | PAF33, PAF21, PAF31 | |

| Believes in the PES logic | Believes that the forest is providing a service to society and that landowners should therefore be compensated and that payment is a good incentive for those that depend on the land | PAF50, PAF21, PAF22 | |

| The project sounded important | Project staff explained what the project entailed and it sounded important for the environment | PAF03, PAF45, PAF08, PAF72 | |

| Likes forest | Decided to participate because always liked forest | PAF18, PAF77, PAF21, PAF66, PAF08 | |

| Wanted to restore and could not do it alone | Joined because wanted to restore part of the property and could not do it alone | PAF88, PAF45, PAF66, PAF73, PAF81 | |

| Used the term rent for PAF | Mentioned that s/he “rented” a small area for PAF | PAF28, PAF45, PAF32 | |

| Legislation | Thought about the legislation because would have to do it eventually anyway | PAF45, PAF22 | |

| Contract flexibility | The contract is renewed every two years, allows maintenance of rights | PAF51, PAF73 | |

| Reduce cost of required reforestation | The legislation requires a forest reserve in order to allow property to be divided into a condominium | PAF55 | |

| Help to avoid tax fine | Had a tax fine because the auditor did not believe the amount of production declared in relation to the size of land | PAF54 | |

| Be able to produce something in the forest area | Aimed to use the forest area, to get benefit from it. | PAF23 | |

| Wanted to restore and could not do it alone | Joined because wanted to restore part of the property and could not do it alone | PAF88, PAF45, PAF66, PAF73, PAF81 | |

| Used the term rent for PAF | Mentioned that s/he “rented” a small area for PAF | PAF28, PAF45, PAF32 | |

| Legislation | Thought about the legislation because would have to do it eventually anyway | PAF45, PAF22 | |

| Contract flexibility | The contract is renewed every two years, allows maintenance of rights | PAF51, PAF73 | |

| Reduce cost of required reforestation | The legislation requires a forest reserve in order to allow property to be divided into a condominium | PAF55 | |

| Help to avoid tax fine | Had a tax fine because the auditor did not believe the amount of production declared in relation to the size of land | PAF54 | |

| Produce something in the forest area | Aimed to use the forest area, to get benefit from it. | PAF23 | |

| Guilt for past deforestation | Realized that past deforestation activities could negatively affect downstream water users | PAF01 | |

| Recognition | Recognition by society that they were doing an important thing by preserving their forest | PAF19, PAF40 | |

| Perception of outcome | Saw the forest growing in some properties with the project | PAF67 | |

| Benefit for others | Joined because would be helping to provide water for the city | PAF72 | |

| 10. Behavior changes required | No behavior change | Reported not have changed any behavior due to the project nor received any environmental benefit because of the project | PAF82, PAF40, PAF78, PAF86, PAF56, PAF33, PAF03, PAF21, PAF06, PAF12, PAF64, PAF51, PAF55, PAF04, PAF22, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF63, PAF34, PAF67 |

| Nothing was done in the property | Reported that the project had not yet completed do the reforestation activities | PAF71, PAF78, PAF86, PAF89, PAF73, PAF67, PAF81 | |

| Became aware of the importance of forest and stopped deforesting | The project increased environment awareness and led stopping deforestation | PAF89 | |

| The change in the property did not impact production | The project protects reforested land and therefore did not have an impact on the productivity of the property | PAF42, PAF66, PAF10, PAF08 | |

| Stopped people from taking wood from the forest | The project would prevent taking wood from the forest | PAF14 | |

| 11. Perception of outcomes | Increase in water availability | Sees an increase in water availability | PAF21, PAF42 |

| Erosion reduced | Perceive erosion reduction affecting the river | PAF45, PAF04 | |

| Needed more audits | The project should have more audits by the state environmental institutions to guarantee that the reforestation was done properly. | PAF54 | |

| Needed more rigor in program execution | Program execution required more generate more results in the reforested areas. | PAF54 | |

| Reduced the problem with fire | The reforestation helped control fires originating on neighbors’ land | PAF14 | |

| Worked in the project | Someone in the landowner family worked on the project | PAF34, PAF14 | |

| 12. Knowledge of environmental regulations | Never worried too much because believes conservation is important | Did not try to find information about environment regulations because they do not want take actions that hurt the environment | PAF82, PAF64 |

| Is aware of PPA and RL | Mentioned the PPA and the RL requirements | PAF82, PAF71, PAF78, PAF89, PAF03, PAF88, PAF06, PAF45, PAF64, PAF01, PAF73, PAF08, PAF25, PAF22, PAF57, PAF63, PAF67 | |

| Increase in environment awareness in the country | Perceives an increase in environmental awareness in the country | PAF71, PAF40, PAF78, PAF36, PAF68, PAF73 | |

| Not allowed to touch anything | The law does not allow changing, extracting, or, removing trees on forest land | PAF78, PAF10, PAF23 | |

| Does not know anything | Claims not to know anything about environmental regulation | PAF86 | |

| Deforestation is not allowed | Deforestation is not allowed | PAF86, PAF89, PAF33, PAF37, PAF21, PAF12, PAF73, PAF08, PAF57, PAF14, PAF34, PAF67 | |

| Fire is not allowed | Using fire for land management is not allowed | PAF33, PAF37, PAF21, PAF22, PAF57, PAF14, PAF34 | |

| Bad chemicals not allowed | Toxic agricultural chemicals cannot be applied near th rivers | PAF06, PAF42, PAF45, PAF14 | |

| Aware of rules | Mentioned many rules including Forest Code requirements | PAF40, PAF56, PAF68, PAF71, PAF50, PAF66, PAF51, PAF55, PAF54, PAF14, PAF31 | |

| Not allowed to extract river sand | The law does not allow to removal of sand from rivers | PAF37 | |

| Not allowed to extract river sand | The law does not allow to removal of sand from rivers | PAF37 | |

| 13. Opinion about environmental regulations | Conservation is important | Thinks the regulations are important because conservation is important | PAF82, PAF40, PAF86, PAF68, PAF36, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF37, PAF50, PAF03, PAF17, PAF45, PAF66, PAF12, PAF64, PAF51, PAF10, PAF04, PAF54, PAF73, PAF32, PAF22, PAF31, PAF63, PAF34, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 |

| Some regulations are overdue | Believes there is an excess in some environment regulations, that some go beyond what is necessary | PAF71, PAF40, PAF37, PAF18, PAF42, PAF73, PAF25, PAF19 | |

| Corruption creates difference in actions between big and small landowners | The law is applied differently to rich and poor landowners | PAF71, PAF86, PAF33, PAF21, PAF45, PAF54, PAF23, PAF14, PAF67, PAF72 | |

| Law is not considered for decision-making | The landowners do not consider the law for decision making | PAF71, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF37, PAF12, PAF51, PAF55, PAF04, PAF34 | |

| In favor of the landowners’ responsibilities | Believes the landowner as a citizen should be responsible for forest on their land | PAF40, PAF88, PAF66 | |

| Any law must be respected | If it is a law, it should be respected | PAF78, PAF03 | |

| People would deforest if it did not exist | If the law did not exist people would cut everything down to plant pasture | PAF78, PAF86, PAF03, PAF18, PAF17, PAF06, PAF45, PAF10, PAF08, PAF25, PAF32, PAF14, PAF63, PAF67, PAF81, PAF72 | |

| Was informed about PPA requirements by the project | When the project was trying to enroll people, the staff informed them that what they were proposing was required in the law | PAF04 | |

| Prevents profiting from the property | The environment regulation restricts the producer too much, it makes the forest of little use | PAF23 | |

| The government itself does not do anything | The government creates all the laws but does not do anything to improve environment awareness | PAF57 | |

| Overlap of legislation | There are so many overlapping environment regulations that it is hard to keep track | PAF19 | |

| 14. Perceived enforcement of environmental regulations | The places with bad roads do not get any enforcement | The places with bad roads do not get any enforcement | PAF56, PAF03, PAF18, PAF67 |

| Never saw law enforcement | Reported that never saw or heard about law enforcement actions | PAF82, PAF03, PAF66, PAF12, PAF23, PAF73, PAF08, PAF63, PAF81 | |

| Rigor in enforcement in relation to deforestation | Reported that the legislation enforcement has been strict or knows people who were fined | PAF71, PAF40, PAF86, PAF36, PAF68, PAF37, PAF50, PAF21, PAF10, PAF04, PAF01, PAF32 | |

| Fine is too high | If environmental enforcement includes fines, the fines are too high | PAF01 | |

| Rigor in the enforcement in relation to hunting | Reported that the legislated enforcement has been strict | PAF40 | |

| Corruption of the enforcement agent | Reported that the enforcement agent may be corrupt | PAF40, PAF68, PAF36, PAF42, PAF45, PAF22, PAF19 | |

| Fine is not paid | The landowners that get fined do not pay the fines | PAF68, PAF36, PAF14 | |

| Was previously fined | Mentioned incurring an environment fine | PAF78, PAF19 | |

| Park area | Property is within the protected area and therefore sees more enforcement | PAF78, PAF21 | |

| Some rigor in environment regulation enforcement | Does not seem to perceive strong rigor, but saw environmental agents or knows people that were fined | PAF89, PAF33, PAF06, PAF42, PAF45, PAF64, PAF54, PAF22, PAF57, PAF34, PAF67, PAF72 | |

| The enforcement agents do not know how to communicate with the landowner | The enforcement agents do not know how to communicate with the landowner, they arrive in the property without explaining the reasoning behind the legislation and give people fines | PAF37, PAF19, PAF67 | |

| Changed behavior because of increased perception of enforcement | Used to deforest, but learned that it was illegal and liable to sanctions | PAF01 | |

| Overlap of enforcement in different levels of government | The overlap of environment regulations in different levels of government leads to excess bureaucracy and confusion | PAF19 | |

| Overlap of enforcement in different levels of government | The overlap of environment regulations in different levels of government leads to excess bureaucracy and confusion | PAF19 | |

| 15. Perceived motivations to comply (or not) with environment legislation | Normative motivations—agrees with the law or believes it is the right thing to do | Complies with environment law because s/he believes it is the right thing to do | PAF82, PAF40, PAF56, PAF17, PAF66, PAF12, PAF55, PAF10, PAF54, PAF23, PAF73, PAF22, PAF14, PAF19, PAF63, PAF34, PAF81 |

| Lack of knowledge about environmental legislation | Believes people do not have knowledge about the legislation | PAF71, PAF77 | |

| Calculated motivations | Believes that the financial utility (money and enforcement) is the most important reason for people to comply or not with environmental regulations | PAF71, PAF78, PAF68, PAF56, PAF89, PAF50, PAF03, PAF18, PAF77, PAF06, PAF45, PAF66, PAF51, PAF55, PAF10, PAF54, PAF01, PAF73, PAF08, PAF22, PAF57, PAF31, PAF19, PAF34, PAF72 | |

| People believe that there will not be sanctions | People are aware of the law, but do not think they will be sanctioned | PAF78, PAF68, PAF56, PAF89, PAF33, PAF50, PAF88, PAF77, PAF25, PAF45, PAF51, PAF10, PAF54, PAF23, PAF08, PAF14, PAF31, PAF34, PAF81 | |

| Cost of bureaucracy | The biggest cost associated with the law if you do not follow regulations is to have to deal with the bureaucracy | PAF68, PAF36, PAF03, PAF18 | |

| Sanctions are not complete and corrupts the citizenry | People do not worry about sanctions because they serve as a way of instituting corruption and bribery | PAF50, PAF77, PAF42, PAF45, PAF51, PAF55, PAF54, PAF23, PAF22, PAF67 | |

| It is necessary to understand the reasoning | People are convinced to conserve forest if they understand the importance of it. | PAF50, PAF77, PAF06, PAF64, PAF31, PAF81 | |

| People live today and do not worry about tomorrow | People make decisions thinking about what they need today, people live today and do not worry about tomorrow, they do not think about the long term | PAF64 | |

| 16. CAR perceived change in environmental regulation and enforcement | Pays someone to deal with bureaucracy | Does not know about CAR, because pays someone to deal with bureaucracy | PAF64 |

| Has not done it | Did not remember to do it or lives in urban area | PAF82, PAF71, PAF28, PAF25, PAF34 | |

| Depends on political will | CAR seems to be a good instrument but its application will depend on the will of politicians; corruption is instituted | PAF40, PAF66, PAF54, PAF23, PAF73, PAF22 | |

| Nothing will change | CAR will not change anything in terms of land management or enforcement | PAF78, PAF86, PAF88, PAF42, PAF66, PAF57 | |

| Only bureaucracy | Nothing will change, it is just another bureaucracy | PAF86, PAF23, PAF57, PAF81 | |

| Is increasing real restrictions | This is a movement to increase real restrictions and enforcement of environmental regulation | PAF68, PAF03, PAF01, PAF72 | |

| Is increasing perception of restrictions | CAR is making people think they will have to comply | PAF77 | |