Abstract

This paper explores the impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and financial distress on corporate financial performance (CFP) in Chinese listed companies of the manufacturing industry. Covering a total of 1445 manufacturing observations from 2013 to 2018 by matching the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) and Ranking CSR Ratings (RKS) database and regression models, we find that CSR has a significant positive impact on CFP, and the relationship is more pronounced for firms that are more stable. Further, the win-win relationship of CSR and CFP is also stronger in state-owned enterprises (SOEs). These empirical results suggest that enterprises should actively embrace CSR in response to the call of the country. At the same time, corporate stability should be increased to enhance the role of CSR in promoting CFP. We provide a quantitative analysis of the CSR, CFP, and financial distress of listed firms, and help to alleviate managers’ concern of CSR fulfillment and risk control.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, social responsibility has become a key issue that cannot be ignored, but cannot get enough attention from developing countries [1]. As the main supplier of global raw materials and commodities and the hub of the global supply chain, the fulfillment of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in China’s manufacturing industry is a valuable research issue. Would corporate financial performance (CFP) be hurt or promoted if firms pursue CSR activities? By all appearances, this question provides significant implications when making CSR decisions for managers. In order to rationalize CSR on reasonable economic grounds and alleviate the worries of managers, the relationship between the two is a hotly debated topic in research [2].

If the high cost of corporate social responsibility cannot bring economic benefits to an enterprise, then any amount of appeal is just moral preaching [3]. The conclusion is still controversial among the classical theoretical and empirical research when it comes to the link between social responsibility and CFP. Stakeholder theory [4] believes that stakeholders include corporate shareholders, creditors, and even government departments and environmentalist pressure groups, etc. An increase in social spending will improve stakeholder relationships, which is conducive to reducing the social costs of firms, leading to an increase in the net financial worth [5,6]. Similarly, signaling theory provides evidence that the transmission of CSR signals can generate positive information beneficial to the enterprise and improve the reputation and competitiveness of the enterprise [7], thus increasing the company’s goodwill and the economic return of the enterprise [8,9]. On the contrary, the agency theory and shareholder theory has introduced an opposite view. The social responsibility of a company will impose agency costs on shareholders. Hence, the focus on CSR may hurt corporate performance [10]. In empirical studies conducted over the past few decades, half or more have confirmed irrelevant, weak, or even negative correlations [11]. As a hotly debated topic, there are no insights about manufacturing in China.

The condition of financial distress is closely related to the fulfillment of CSR. When an enterprise is in financial distress, its priority is to relieve the financial strain and interests of shareholders, rather than to benefit the society [12]. Previous research have shown that experienced managers avoid getting a company into financial distress, and low-risk companies outperform firms with high risk [13,14]. Firms with a more unstable financial structure are more likely to lose their market share, especially during industry downturns. While there are a few studies combining CSR, CFP, and financial distress in the context of Chinese manufacturing enterprises, our second main research question therefore is the relationship between financial distress and CFP and whether the relationship between CSR and CFP is more pronounced for companies that are more stable.

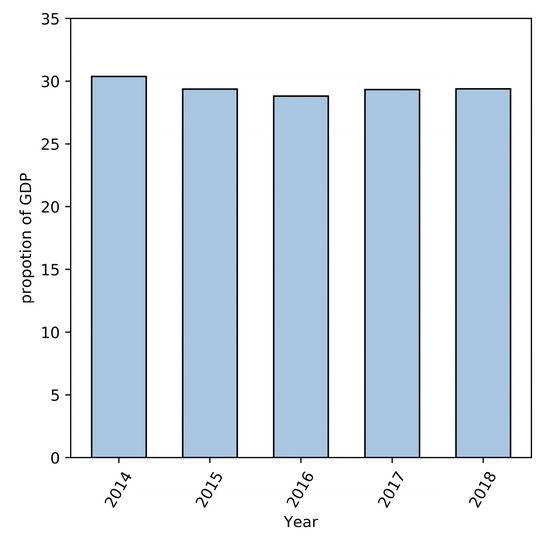

This paper aims to explore the connection of CSR, CFP, and financial distress. To do so, we compile data from CSMAR and Ranking CSR Ratings (RKS). RKS is an authoritative third-party rating agency for corporate social responsibility in China, dedicated to providing objective and scientific corporate responsibility rating information for responsible investors (SRI), responsible consumers, and the public. China’s listed companies of manufacturing are a good laboratory to test the relationship. The manufacturing industry is the principal part of the national economy in China. As part of the pillar industry, the listed companies in manufacturing are becoming the center of CSR, so it is imperative to evaluate the financial impact of CSR [15]. Figure 1 illustrates the proportion of manufacturing output in GDP, indicating the pivotal role of manufacturing in the national economy. Hence, the motivation of this paper is to explore the connection between the CSR and CFP of listed companies in Chinese manufacturing.

Figure 1.

Proportion of manufacturing output in GDP from 2014 to 2018 in China.

The empirical results contribute the following aspects. Much of the previous research [16,17] focuses on the association between CSR performance and CFP. This paper surveys the major national economy industry in China, and also focus on the mediating role of financial distress. In addition, we examined the differences between state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-SOEs and made some empirical contributions to the implementation of CSR in China’s context. Finally, when we conducted a robustness test, with the help of a natural exogenous event, one-to-one propensity score matching (PSM) was used to explore whether there is a discrepancy in the relationship before and after the policy was introduced—that is, the guidance on state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to better fulfill their social responsibilities issued by the State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), a landmark policy to promote CSR performance.

The existing literature concerning CSR in emerging markets usually focuses on entire A-share listed companies to explore its relationship with corporate performance. We focus on the manufacturing industry and incorporate financial distress into the study of CSR and CFP. In detail, after studying the effect of CSR and financial distress on financial performance, this paper explores the moderating effect of financial distress on CSR and CFP. In this way, managers can realize the importance of controlling financial risks while fulfilling social responsibilities. Besides, we have fully taken into account the ownership in our hypothesis, and conducted group tests on all relationships. To be specific, we divide all the sample enterprises into SOEs and non-SOEs, and conduct a group test between CSR, financial distress, and CFP, which is not considered fully in the previous literature.

2. Literature Reviews and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR in China

Since the reform in 1979, China’s economy has experienced remarkable developments in the past few decades. However, the excessive pursuit of profits causes some social responsibility problems—such as with the environment, employment relations, consumer rights, etc.—and inevitably increases the cost of enterprises [18]. In the early 21st century, relevant departments gradually realized the importance of CSR and called on enterprises to consider the interests of stakeholders in the course of business. In the construction of the social responsibility system, Chinese entrepreneurs have carried out excellent social responsibility practices and have made outstanding achievements [19].

Evidence shows that CSR is undergoing a rapidly growing salience in China, albeit from a weak foundation, and is increasingly becoming a management issue, with the importance of the government and entrepreneurs attached to it [20]. In 2006, the new company law expects enterprises to participate in social responsibility. Then came China’s first social responsibility report from the state grid. SASAC issued special instructions for SOEs to fulfill their social responsibilities in 2008. In 2011, SASAC and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences jointly issued the Guidelines for the Preparation of Chinese Corporate Social Responsibility Report. It seems that the policy indicates that state-owned enterprises should assume more social responsibility, but some scholars think that state-owned enterprises are more reluctant to undertake the construction of corporate social responsibility [21].

At the same time, CSR rating agencies have emerged, among which one of the most professional is RKS. RKS is an authoritative third-party rating agency for CSR in China. It is committed to providing objective and scientific corporate responsibility rating information for responsible investment, consumers, and the public [22]. In developed countries, in view of the early start of CSR, the definition and measurement of CSR are more complete. Some studies have defined CSR as a moral behavior, including social, political, economic, and cultural aspects [23]. According to this definition, a mature social responsibility rating is gradually formed. The Kinder, Lynderberg, Domini Research, and Analytics Inc. (KLD) databases are good examples. Based on an extensive analysis of surveys, financial statements, news, academic research, and government reports, KLD has provided CSR information to more than 3000 companies, accounting for 98% of the total market capitalization of all publicly traded companies in the United States [5].

In recent years, many studies have concentrated on the CSR in China, an emerging market, and tried to figure out the social responsibility of Chinese companies in multiple dimensions. This will be mentioned in detail in the literature review and hypothetical development below.

2.2. Relationship between CSR and CFP

Existing studies have shown that the relationship between CSR and CFP is inconclusive globally and controversial [24]. Numerous studies show that CSR is significantly positive with a firm value [25,26]. Research proves that, although the company is under pressure to allocate scarce resources in management, there is a virtuous circle between corporate performance and social performance [27], which also confirms the point of view of the slack resource theory. Slack resource is a good method to resolve conflict when firms face difficulty. Meanwhile, CSR is an excellent way to obtain redundant resources through good social reputation, good employment relationship, etc. Ethical managers realize the importance of CSR and take advantage of it. When there are conflicts among stakeholders, managers will skillfully adopt CSR to solve the conflicts and maximize the interests of shareholders, thus proving that CSR is conducive to corporate performance [28].

As researchers are developing a more profound understanding of CSR, empirical study shows that embracing social performance is not only a skillful management strategy in developed countries, but also in developing countries. The company’s historical performance has a significant and positive impact on the release of independent CSR reports, and there is a positive correlation between CSR disclosure and subsequent performance [16]. As for the relationship between the two, the existing literature is still inconclusive about China’s manufacturing industry. We adopt Chinese listed companies in the manufacturing industry as our research sample to enrich the literature.

Conversely, some studies have proved the opposite. They believe that, in order to enhance personal reputation, the internal personnel or major shareholders of the company may carry out irrational or excessive CSR construction, but the cost is borne by the company rather than by themselves [5]. As a result, the interests of the enterprises will be harmed. More interestingly, while most scholars highlight the linear relationship, a third find that the link between the two may be not linear but rather a slightly complicated nonlinear relation [29]. One of the reasons for these mixed results is the different selection of variables and limited data in different enterprises and industries. The positive effect is found by most literature, despite the conflicting conclusions in the literature. Hence, our first hypothesis is the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

CSR is positively related to CFP in China’s listed manufacturing industries.

2.3. Relationship between Financial Distress and CFP

Financial distress is often thought of as poor financial structure and bringing financial risk to firms [30]. Scholars claim that managers usually have smaller voice in management when the company with a high leverage, which incurs agency costs and in turn leads managers to be more inclined to make high-risk decisions [31]. Similarly, empirical results have proved that negative correlation usually emerges between poor debt structure (usually manifested as leverage) and corporate performance after unsuccessful takeovers [32]. The occurrence of the financial crisis has made enterprise managers realize the importance of the level of financial distress. Companies are vulnerable during financial crises [33]. Based on the negative correlation between financial crisis and corporate performance, as an exogenous variable the financial crisis will amplify this effect [34]. Correspondingly, the literature further proves that there is a more significant negative correlation in the relationship after the crisis than before [35].

In recent research, many scholars have found that CSR affects corporate ratings, which in turn affect corporate debt costs and financing costs [36,37]. Specifically, CSR raises the ranking of enterprises, and the improvement of reputation brings a reduction in the financing barriers, which is conducive to corporate performance.

Previous research has focused on the reflection between financial distress and corporate performance or financial distress and social performance [37,38]. A few studies have used financial distress as a moderator between the relationship of corporate performance and CSR in the Chinese manufacturing context. When a company gets into financial distress, on the one hand, managers will give priority to the interests of shareholders rather than all the stakeholders. At this time, they will not be as committed to the CSR as enterprises with a lower financial risk. On the other hand, the existence of financial distress sends a bad signal to the outside world. Even if the company fulfills its social responsibilities, it is difficult to convert social responsibilities into corporate performance like a healthy company can. Therefore, this paper blazes a new trail and uses financial distress as a moderator in the relationship between CSR and CFP. Thus, this paper proposes the hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Financial distress inhibits CFP in China’s listed manufacturing industries.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Financial distress has a negative moderating effect on the relationship of CSR and CFP.

In addition, the existence of SOEs is a prominent feature of Chinese listed companies [39,40]. SOEs have natural political ties and are subject to more government regulation than non-SOEs. With more political goals and bureaucrats, SOEs operate less efficiently than non-SOE firms [41]. However, the goal of SOEs in social responsibility issues such as the environment is higher than that of non-SOEs. Accordingly, more capital will be invested [42,43]. Considering the difference between the SOEs and non-SOEs, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

There are differences in the relationship between CSR and CFP among companies of different ownership.

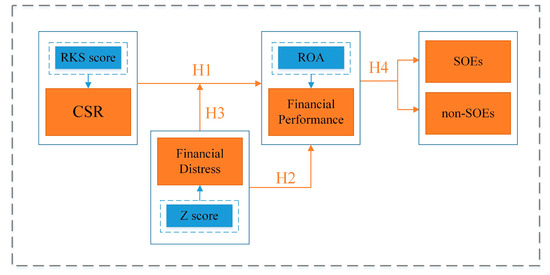

Figure 2 illustrates the proposed hypotheses and analytical framework. Hypothesis 1 and 2 are presented to explore the impact of CSR and financial distress on CFP. Especially, we focus on the moderating effect of financial distress on the relation of CSR and CFP in Hypothesis 3. Further, considering the impact of ownership, we will study the above three hypotheses in groups according to the ownership of the enterprise, which is Hypothesis 4 in the framework.

Figure 2.

Hypotheses and analytical framework.

3. Measurement of Variance and Model Construction

3.1. Measurement of CSR

In China, the measurement of CSR is a complex issue. For the United States and European countries, the Dominican 400 Social Index database is widely used when referring to CSR. The Dominican 400 Social Index is the first index in the United States based on social and environmental issues. The Kinder, Lydenberg, and Domini (KLD) database was founded in 1990 and began to use this index. The database was widely adopted by scholars for its professionalism [44,45]. Therefore, scholars who have studied Chinese CSR for a long time could only measure CSR through the content scoring method based on the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) [46], until the emergence of the RKS database [20,47]. It focuses on the corporate governance, environmental and social issues and covers the 15 first-level indicators such as strategy, stakeholders, fair operation and the 63 secondary indicators of its subordinates. Therefore, under the existing conditions, we chose the RKS scores as our research basis.

3.2. Measurement of CFP

Compared to CSR, CFP is more consistent and easier to measure. Based on previous studies, the existing literature mainly adopts two methods to measure CFP. One is to adopt accounting indicators; the most common indicator is Return on Assets (ROA) [48,49] or Return on Equity (ROE) [50]. Another is to use market indicators, such as Tobin’s Q or the market shares [51]. This paper chooses ROA as the proxy CFP. ROA is an indicator to measure how much net profit is created per unit of assets. It organically combines the relevant information in the balance sheet and income statement, and is a concentrated reflection of the ability of an enterprise to use all its funds to obtain profit. Therefore, the paper uses ROA to measure CFP, and the data on ROA is more complete in the CSMAR database than other indicators.

3.3. Measurement of Financial Distress

Regarding the measurement of financial distress, the current literature mainly uses the financial index method. Among the representative financial indicator methods, the typical way is the Z score proposed by Altman in 1968, which is widely used in the research of financial distress and its prediction. Initially, Altman selected 33 bankrupt and excellent companies as a sample of manufacturing companies. Relevant data in the balance sheet and income statement of the sample companies were collected, and the predicted bankrupt companies from 22 variables by sorting were selected. Finally, five useful variables were selected to establish the Z score. In this equation, different weights to five financial indicators were assigned to produce the Z score, which is:

Among them, X1 represents the working capital/total assets, X2 equals the retained earnings/total assets, X3 is the profit before interest and tax/total assets, X4 represents the total market value of common stock and the preferred stock/total book value of liabilities, and X5 is the total sales revenue/total assets. The model is a comprehensive reflection of the financial situation of an enterprise. Therefore, the Altman Z score is adopted to measure financial distress in order to obtain objective conclusions. In particular, a high Z score means that the enterprise is less likely to face financial distress, so the financial risk is lower.

3.4. Model Construction

In our model, in addition to the variables mentioned above, there are other variables should be included as control variables. Following previous studies, we chose these variables in our estimation equation, including: (1) Leverage, which is equal to the asset liability. It is used to measure the ability of a company to operate with the funds provided by creditors and to reflect the degree of security of loans made by creditors. Research have proved that leverage is positively related to CFP [52]. (2) Growth. This refers to the growth range of the operating revenue in the current period compared with the previous period. The larger the index value is, the stronger the profitability of the enterprise is. In general, the higher the growth rate, the more promising the company’s development prospects are [53]. Meanwhile, it affects the investor’s willingness to invest. (3) CR (Current Ratio), measured as the current assets divided by the current liabilities. This is used to measure the ability of an enterprise’s current assets to be converted into cash and used to repay liabilities before short-term debts mature. Generally speaking, a high ratio means a stronger liquidity of the enterprise assets, which also means the rationality of the enterprise financial structure. However, if the index is too large, it also means that the company has not balanced the financial leverage well, which reduces the efficiency of the use of funds. (4) CASH (Cash Ratio). Similar to CR, CASH can affects solvency of the enterprise. The cash ratio measures only the most liquid items of all assets relative to current liabilities, so it is the most conservative measure of solvency relative to current ratios and quick ratios. (5) Slack, which is equal to monetary capital divided by total assets, and represents the redundant resources of the enterprise. Based on agency theory and organization theory, the impact of redundant resources on corporate performance is a U-shaped curve. Table 1 illustrates all the variables in our model.

Table 1.

Definitions of all the variables.

To test Hypotheses 1 and 2, the following two quadratic regressions are constructed:

where, for firm i and year t, ROA is the dependent variable and represents the CFP in all regressions in this paper. As independent variables, CSR is the rating score from the RKS database and Z is the Altman score in Equations (3) and (4), respectively. The other are a set of control variables which have been mentioned above; ω is the error term.

Similarity, to verify H3, the paper constructs the third regression:

In Equation (5), an interaction term is added to explore the moderating effect of financial distress on the CSR–CFP relation. In this part, if the interaction terms’ coefficients are significant, H3 will be confirmed. Furthermore, the sign of coefficients will prove the direction of the effect. In order to explore H4, we do not perform a special model, but divide all the samples into two groups of SOEs and non-SOEs. The three regression equations above are tested separately for SOEs and non-SOEs. The regression results will be presented in Section 5.

4. Sample and Data

The manufacturing industry directly reflects the productivity level of a country and is an important factor to distinguish developing countries from developed countries. It also occupies an important share of the national economy of developed countries. At the same time, considering the availability and integrity of data of all the analyzed variables, this paper collects manufacturing firms which publish data in the RKS and CSMAR databases. As mentioned earlier, RKS is one of China’s most authoritative social responsibility rating agencies. Similarly, CSMAR is China’s largest financial database. Combined with China’s actual national conditions, after 18 years of continuous accumulation and improvement the CSMAR database has covered 18 major series, such as companies, green economy, and stocks, which are widely used by researchers. According to the Industry Classification Guidelines for Listed Companies issued by the China security regulatory commission (CSRC) in 2012, the manufacturing sector is classified as category C13 to 43. After excluding all the missing data in the 341 firms from 2013 to 2018, 1445 observations are collected finally. Table 2 describes the secondary industry classification of the sample firms in the manufacturing industry in detail. The annual distribution of the samples and the ratios of different ownership are shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Industry classification of the 341 firms in China’s manufacturing industry.

Table 3.

Years and ownership distribution of 1445 observations in China’s manufacturing industry.

In our experiment, the SPSS 23 software was used for descriptive statistics and Pearson correlation coefficient test, and the EVIEWS 9.0 software was used for model estimation. Table 4 displays the basic descriptive statistics. Columns 3–5 present an overview of all the variables, and column 6 is the standard deviation (S.D.), which presents a relatively large difference among all the samples. The mean of ROA value is only 0.03, indicating that the sample enterprises generally have mediocre CFP. The highest CSR score is 89, and the average of observations is 40.74, showing that the CSR performance of our samples is not outstanding. The mean Z score is 4.92. According to the definition of the Altman model, when the Z score exceeds 1.8, it means that the risk in bankruptcy is very small. Hence, 4.46 indicates that the overall risk of the observations is low. Although the median is 4.46, there is a large difference between the maximum and minimum for the Z score. Similarity, a large gap exists in the CR. As for Lev, although the average is 50%, a reasonable level, the maximum enterprise is as high as 1.31, indicating that it is insolvent.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of all the variables.

The correlation matrix between every two variables is displayed in Table 5. In general, there is no multi-collinearity problem in this model because the maximum correlation coefficient is 0.47 and no more than 0.7. As we expected, a positive relationship between CSR–CFP and Z-CFP is proved primarily. Among them, the CR, Cash, and Slack are positively related with CFP, which is reasonable based on the definition of variables. It is significantly negative between Lev and CFP, which is consistent with the explanation of Lev in Section 3.4. In addition, it could be observed that the link between CR and Growth is positive, but that between CR and Lev is strikingly negative.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation matrix for all variables of all observations.

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Regression Results

Firstly, as the results show in Table 6, ROA and CSR are employed as the dependent and independent variable, respectively, and the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model is adopted to investigate the relation between CSR and ROA. The regression results show that the CSR is significantly positively correlated with ROA at the level of 0.01, and the correlation coefficient is 0.000835, indicating that CSR will significantly promote CFP. This result verifies the H1. It is worth noting that the coefficients in our model are small, because the value of the dependent variable ROA is small (below 1), but the independent variable CSR is mostly above 30.

Table 6.

Regression results of the OLS of all samples for the three models.

Secondly, the relationship between Z and ROA is examined. As shown in the third column, Z is a proxy variable for financial distress. Similarity to CSR, Z is significantly positively correlated with ROA, and the correlation coefficient is 0.001636. This implies that, with an increase in the Z score, which represents a lower risk of financial distress, the CFP also increases. Therefore, H2 is proved.

Thirdly, in model 3, the interaction terms of financial distress and CSR are added, and the coefficient of the interaction terms is significantly positive (0.0000663, p < 0.01). This indicates that the Z score plays a positive moderating role in the CSR–CFP relation. The higher the Z score, the stronger the role of CSR in promoting CFP. A higher Z score means a company is less likely to face financial distress and is accordingly more stable and healthy. Therefore, H3 has passed the test, and the win-win relation of CSR–CFP is more pronounced for firms that are more stable.

Considering the possible endogenous problems, we further use Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) to test the hypothesis. Table 7 shows the results of the GMM. It shows that at least at the level of 10% our three hypotheses are passed. The results of AR (2) prove that there is no second-order serial autocorrelation (p values are significantly greater than 0.1). On the whole, the positive relationship of CSR–CFP and the inverse relation between financial distress and financial performance is still significant. Meanwhile, the negative moderate role of financial distress in the relation of CSR–CFP has not changed yet.

Table 7.

Regression results of the GMM of all samples for the three models.

5.2. Addition Test of SOEs and Non-SOEs

The paper posits that there is discrepancy between firms with different ownerships in the three hypotheses above. In order to verify H4, all 1445 samples are divided into two groups according to ownership, and labeled as SOEs and non-SOEs. Table 8 illustrates the empirical results. For H1, comparing column 2 with column 6, the coefficient of column 2 is larger (0.000995 > 0.000746). Thid confirms that, compared with non-SOEs, the relationship between CSR and CFP is more positive in the SOEs. On the contrary, in the relationship between Z and CFP, the results of column 7 are more significant than those of column 3, which means the correlation between financial distress and CFP more pronounced for non-SOEs. As for H3, the result shown in the table is intriguing and worth thinking about. In non-SOEs, z plays a much stronger role in the relation of CSR–CFP than in SOEs.

Table 8.

Regression results of the SOEs and non-SOEs.

5.3. Robustness Tests

In this paper, three ways are used to test robustness. Firstly, we adopt the one-to-one PSM method and an exogenous event as a natural opportunity to randomly divide the samples into the experimental group and the control group to explore whether there is any substantial difference among all the hypotheses in the previous paper. The exogenous event greatly affects the CSR of listed companies, but has minimal impact on the finance of firms.

The guidance on SOEs to better fulfill their social responsibilities issued by SASAC in 2016 plays a highly guiding role for enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities. It points out the three principles that state-owned enterprises should focus on. Meanwhile, the guidance put forward the overall goal of encouraging state-owned enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities. This paper takes this policy as a sign to conduct grouping tests. In detail, the policy naturally divides the whole samples into two groups for matching; one is the experimental group in 2013–2015, and the other is the control group in 2016–2018. The one-to-one PSM method matched two groups of samples based on all variables, and finally matched 611 pairs of samples. Table 9 and Table 10 report the results of the two groups.

Table 9.

The experimental group from 2013 to 2015.

Table 10.

The control group from 2016 to 2018.

Before and after the policy was issued, at the level of 1%, the correlation coefficients of CSR and CFP are 0.000625 and 0.000997, respectively. Meanwhile, the Z score is significantly positive with ROA at the level of 5%. In addition, the coefficient of the interaction term is positive, indicating the positive role of the Z score. In conclusion, it is found that there is no significant and substantial difference between the two groups in the positive correlation of CSR–CFP before and after the policy was introduced. The regulatory role of financial distress has not changed yet. Therefore, after sample matching, the relationship remained intact after a major external policy change, which has a profound impact on CSR.

Secondly, the variables in the current period may not directly affect the CFP over the same period, but they will affect later periods. Considering the time lag, the lagging independent variable (CSRt-1) and the control variable (CONTROLt-1) are used to perform regression with the dependent variable (ROAt). Table 11 shows the regression results. The CSR in column 2 and Z * CSR in column 4 are significant at the level of 1%; Z in column 3 is also positive with the ROA, indicating that the results are consistent with those above. Thus, the empirical results have no substantial differences with the consideration of time lag.

Table 11.

The results of the robustness test.

Thirdly, the substitution method is carried out for the robustness test—that is, to replace the ROA with EPS. EPS is the earnings per share of an enterprise, and refers to the after-tax profit per common share. This is the final result of a company’s profitability. A high EPS represents a company’s high profitability per unit of capital, which indicates that the company has some better ability such as product marketing, technical ability, management ability, etc. Therefore, we use EPS to replace the ROA, which represents CFP in the previous paper, and observe whether the results are still robust. In columns 2 and 3 in Table 12, the positive relationship of CSR–CFP (0.014912, p < 0.01) and Z-CFP (0.011241, p < 0.1) are verified. Similarity, the coefficient of the interaction term proves the positive moderation of Z in the relationship of CSR and firm performance (0.000645, p < 0.01).

Table 12.

The results of robustness test 2.

Therefore, the results show that there is no substantial difference between the results mentioned in 5.1 after considering the time lag and taking EPS as the substitution variable of enterprise performance. This means that the relationship of CSR–CFP and Z-CFP is significantly positive. In addition, the relation of CSR and CFP is more pronounced among firms with a higher stability.

5.4. Discussion

Research on CSR is a hot topic, especially in recent years, and is becoming a skillful business strategy. This study explores the impact of CSR and financial distress on CFP in Chinese listed companies of manufacturing. In particular, we explore the moderating role of financial distress on the relation of CSR–CFP. A total of 1445 observations from 2013 to 2018 in the CSMAR and RKS databases are adopted to conduct regression models.

In the first model, as the regression results show, we adopt the RKS score and ROA as the proxy of CSR and CFP. We could conclude that the positive relation of CSR and CFP is supported absolutely. In detail, the two have a positive correlation at 1% and at least at the 10% level in other tests. The investment in social performance could promote financial performance, whether in the current period or in a lag period. In model 2, which examines the relationship between financial distress and CFP, the Z score and CFP are positive at least at the level of 10%. With the increase in the Z score, the CFP is increasing. This proves that financial distress inhibits CFP due to the fact that a high level of Z score means a low level of financial distress. A bad financial situation leads to poor financial performance. In the third model, we add the interactive item to verify the moderating role of the Z score in relation of CSR and CFP. At the level of 1%, the positive coefficient proves the negative moderating role of financial distress in the link of CSR and CFP. This result may be due to the fact that, when the company is in financial distress, the manager will give priority to the improvement of the financial situation. A focus on the interests of shareholders may lead to the neglect of other stakeholders. The transformation of CSR investment into CFP will not be like that of normal enterprises.

To verify hypothesis 4, which takes the ownership into account, enterprises of different ownership show differences between the relationship above. In China, SOEs are owned or controlled by the state. The behavior of SOEs is determined by the will and interests of the government. The results mean that SOEs are more effective in promoting CSR to CFP; meanwhile, the financial situation has a deeper impact on the relationship between them. SOEs are the pillar of our national economy, and the leading strength of the industrial enterprise of our country. Fulfilling social responsibility is the duty of SOEs, and they are more likely to achieve a win-win situation between CSR and CFP, especially, when in good financial situation. Compared with SOEs, non-SOEs would concentrate more on financial promoting in a highly competitive environment. Financial situation is more important for them. As a result, the negative relation of financial distress with CFP is more significant in non-SOEs.

6. Conclusions

Many empirical studies have given multiple perspectives on the relationship of CSR and CFP. Despite the abundant empirical evidence on the CSP–CFP relationship, few studies focus on the relationship between CSR and CFP and the role of financial distress in such a relationship in Chinese listed companies of manufacturing. To answer this call, we built 1445 samples from the CSMAR and RKS databases and examined the complex relationship between the CSR score and Z score and ROA. In addition, some interesting differences are proved between SOEs and non-SOEs through sample grouping.

Several findings are noted as follows. Firstly, as the signaling theory and stakeholder theory show, CSR is a positive sign for corporations. When a company fulfills its social responsibility and performs well, it sends a positive signal to its stakeholders, such as shareholders, creditors, employees, and even government agencies, thus providing multiple ways to benefit the CFP. For example, companies could get loans at a lower cost, government agencies will adopt more preferential tax policies, and employees will work harder. Secondly, the paper concludes that the CSR–CFP relationship is more significant in companies with a low bankruptcy risk. Hence, the empirical results provide a practical implication for firms to improve both CSR and financial health. The lower financial risk allows the managers of the enterprise not to be confined to controlling financial risks. This allows the focus of management and the investment of economic resources to be placed in direct production and operation. At this time, the CSR has a higher conversion rate to corporate performance. Thirdly, the win-win relationship of CSR and CFP is a little stronger in SOEs. This result is reasonable and instructive. SOEs are generally backed by the government or nation, and thus they are more motivated to carry out CSR activities to obtain a higher reputation and achieve a win-win with the firm value, especially when the enterprise faces low risk. Compared with SOEs, non-SOEs enjoy a higher degree of marketization and competitive pressure; accordingly, they are more profit-driven. Therefore, they pay more attention to the financial situation. A good financial condition makes non-SOEs more involved in the improvement of economic efficiency, which confirms the fact that the inverse relation between CFP and financial distress is more significant in non-SOEs.

Compared with previous studies, this paper has some differences and makes some contributions. On the one hand, the objects of research are Chinese manufacturing enterprises. In addition to studying the impact of CSR and financial distress on financial performance, we also take the moderating role of financial distress into account and draw conclusions about the inhibitory effect. In this way, the relationship between CSR, financial distress, and CFP in manufacturing enterprises is studied more comprehensively. On the other hand, considering the particular characteristics of the Chinese enterprise, we combine the relationship between the variables and the ownership of the firms for analysis. Compared with previous studies that considered the ownership in CSR and CFP mostly, we considered the impact of ownership more broadly.

The results are consistent with policies released in recent years that aim to raise awareness of CSR and achieve win-win development. Meanwhile, our empirical results have certain implications for the policy-making of government and enterprise managers. First of all, the fulfillment of social responsibility is a win-win situation. Efforts to improve the CSR score will not only benefit social development, but also enable enterprises to obtain economic returns. Secondly, the risk of bankruptcy plays a restraining role in the process of corporate social responsibility to improve corporate performance. Hence, the managers of enterprises should always pay attention to corporate financial distress, rationally use financial leverage, and effectively control corporate risks. Further, the government should encourage non-SOEs to fulfill their CSR because of the natural political freedom they have. For example, for consumers, they need to take the social responsibility of being polite and honest to ensure the authenticity of products, so as to maintain the market order. For environmental issues, they could attach great importance to resource conservation and improve production efficiency.

Due to the limiting conditions of data collection, the paper regards CSR as an overall indicator and adopts a comprehensive score to measure it, but not in several dimensions. In fact, CSR is a comprehensive concept including consumers, community, and the environment etc. Future research could focus on the impact of different dimensions of CSR on finance if data are available, thus providing more implications in detail when making CSR decisions for managers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.; methodology, L.W.; writing-original draft preparation, L.W.; writing-review and editing, Z.S. and L.W.; data resource C.Y., funding acquisition, Z.S. and C.Y.; visualization, T.D. and W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 71601063 and 71771076; the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, grant number JZ2020HGTB0038.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jamali, D. The case for strategic corporate social responsibility in developing countries. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2007, 112, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Elfenbein, H.A.; Walsh, J.P. Does it pay to be good. And does it matter? A meta-analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. SSRN Electron. J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Sewon, O.; Claiborne, M.C. Determinants and consequences of voluntary disclosure in an emerging market: Evidence from China. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2008, 17, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A.; Rubin, A. Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C. Stakeholder theory, value, and firm performance. Bus. Ethics Q. 2013, 23, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2010, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.M.; Masud, A.K.; Kim, J.D. A Cross-country investigation of corporate governance and corporate sustainability disclosure: A signaling theory perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, A.; Karaman, A.S.; Kılıç, M. Is corporate social responsibility reporting a tool of signaling or greenwashing? Evidence from the worldwide logistics sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-A.; Kecskés, A.; Mansi, S. Does corporate social responsibility create shareholder value? The importance of long-term investors. J. Bank. Financ. 2020, 112, 105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chau, K.W.; Wang, H.; Pan, W. A decade’s debate on the nexus between corporate social and corporate financial performance: A critical review of empirical studies 2002–2011. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capon, N.; Farley, J.U.; Hoenig, S. Determinants of financial performance: A meta-analysis. Manag. Sci. 1990, 36, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männasoo, K.; Maripuu, P.; Hazak, A. Investments, credit, and corporate financial distress: Evidence from Central and Eastern Europe. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2018, 54, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, K. Current problems in China’s manufacturing and countermeasures for industry 4.0. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2018, 2018, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lin, K.Z.; Wong, W. Corporate social responsibility reporting and firm performance: Evidence from China. J. Manag. Gov. 2015, 20, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Hung, P.-H.; Chou, D.-W.; Lai, C.W. Financial performance and corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from Taiwan. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2019, 24, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, E.H.C.; Yeh, C.-C.; Wang, L.-H.; Fung, H.-G. The relationship between CSR and performance: Evidence in China. Pac. Basin Financ. J. 2018, 51, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidpeter, R.; Stehr, C. A history of research on CSR in China: The obstacles for the implementation of CSR in emerging markets. In Sustainable Development and CSR in China: A Multi-Perspective Approach; Schmidpeter, R., Lu, H., Stehr, C., Huang, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, C.P.; Qian, C. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organ. Sci. 2014, 25, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, L.; Yeh, C.-C.; Yu, H.-C. Disclosure of corporate social responsibility and environmental management: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2011, 19, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Ho, K.-C. Does corporate social responsibility matter for corporate stability? Evidence from China. Qual. Quant. 2017, 52, 2291–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timothy, M.D. Is the socially responsible corporation a myth? The good, the bad, and the ugly of corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. Persp. 2009, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtens, B. A note on the interaction between corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 68, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddock, S.A.; Graves, S.B. The corporate social performance–financial performance link. Strat. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quéré, B.P.; Nouyrigat, G.; Baker, C.R. A bi-directional examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility ratings and company financial performance in the European context. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 148, 527–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Harjoto, M.A. Corporate governance and firm value: The impact of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 351–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegbite, E.; Guney, Y.; Kwabi, F.; Tahir, S. Financial and corporate social performance in the UK listed firms: The relevance of non-linearity and lag effects. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2018, 52, 105–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inekwe, J.; Jin, Y.; Valenzuela, M.R. The effects of financial distress: Evidence from US GDP growth. Econ. Model. 2018, 72, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; pp. 163–231. [Google Scholar]

- Jandik, T.; Makhija, A.K. Debt, debt structure and corporate performance after unsuccessful takeovers: Evidence from targets that remain independent. J. Corp. Financ. 2005, 11, 882–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, M. Corporate Financial Distress: A Roadmap of the Academic Literature Concerning its Definition and Tools of Evaluation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 5–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, T.K. Financial distress and firm performance: Evidence from the Asian financial crisis. J. Financ. Account. 2012, 11, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bouslah, K.; Kryzanowski, L.; M’Zali, B. Social performance and firm risk: Impact of the financial crisis. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 149, 643–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goss, A.; Roberts, G.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank. Financ. 2011, 35, 1794–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomou, I.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. The impact of corporate social performance on financial risk and utility: A longitudinal analysis. Financ. Manag. 2012, 41, 483–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chollet, P.; Sandwidi, B.W. CSR engagement and financial risk: A virtuous circle? International evidence. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, G. Harmonious society and Chinese CSR: Is there really a link? J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 89, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, R. Corporate social responsibility, ownership structure, and political interference: Evidence from China. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Zhang, B. The impact of corporate governance on state-owned and non-state-owned firms efficiency in China. N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 33, 252–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Li, W.; Lu, X. Government engagement, environmental policy, and environmental performance: Evidence from the most polluting Chinese listed firms. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2013, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liang, J. The effects of firm ownership and affiliation on government’s target setting on energy conservation in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 199, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makni, R.; Francoeur, C.; Bellavance, F. Causality between corporate social performance and financial performance: Evidence from Canadian firms. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 89, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.Y.; Lee, C.; Pfeiffer, R.J. Corporate social responsibility performance and information asymmetry. J. Acc. Public Policy 2013, 32, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Chang, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Du, Y.; Pei, H. Corporate environmental responsibility (CER) weakness, media coverage, and corporate philanthropy: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 33, 551–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, P.B.; Vieito, J.P.; Wang, M. The role of board gender and foreign ownership in the CSR performance of Chinese listed firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2017, 42, 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.M.; Sawczyn, A.A. The relationship between corporate social performance and corporate financial performance and the role of innovation: Evidence from German listed firms. J. Manag. Control 2013, 24, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, B.; Kraude, R.; Narayanan, S. Operational productivity, corporate social performance, financial performance, and risk in manufacturing firms. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2016, 25, 2065–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitjean, M. Eco-friendly policies and financial performance: Was the financial crisis a game changer for large US companies? Energy Econ. 2019, 80, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.; Mamun, A.; Hassan, M.K. The relationship between board characteristics and performance of bank holding companies: Before and during the financial crisis. J. Econ. Financ. 2015, 40, 438–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Sanchez, P.; de La Cuesta-Gonzalez, M.; Paredes-Gazquez, J.D. Corporate social performance and its relation with corporate financial performance: International evidence in the banking industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, D. Can ownership structure improve environmental performance in Chinese manufacturing firms? The moderating effect of financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 225, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).