Abstract

(1) Background: Rare disease patients in China usually have to travel a long distance, typically across provinces, for an accurate diagnosis due to the uneven distribution of healthcare resources. This study investigated the impact factors of their trans-provincial diagnosis. (2) Methods: An analysis was made of 1531 cases (1032 adults and 499 children) garnered from the 2018 China Rare Disease Survey, representing a large patient community inflicted with 75 rare diseases from across 31 Chinese provinces. Logistic regression models were used for separate analysis of adult and child patient groups. (3) Results: Nearly half (47.2%) of patients obtained their accurate diagnosis outside their home provinces. The uneven geographical distribution of high-quality healthcare had a significant impact on variation in trans-province diagnosis. Adult patients with lower family income, rural hukou and severer physical disability were disadvantaged in accessing trans-provincial diagnosis. Families with a child patient tended to pour resources into obtaining the trans-provincial diagnosis. The rarity of the disease had only a minimal effect on healthcare utilization across the provinces. (4) Conclusions: In addition to medical care, more attention should be paid to the socioeconomic factors that prevent the timely diagnosis of a rare disease, especially the uneven geographical distribution of high-quality healthcare resources, the financial burden on the family and the differences between adult and child patients.

1. Introduction

Coping with the globally accelerating challenge of rare disorders, the International Rare Diseases Research Consortium (IRDiRC) has a vision to “enable all people living with a rare disease to receive an accurate diagnosis within one year of coming to medical attention” [1]. An accurate diagnosis is the first step toward improving the quality of life of people with rare diseases and their families. It means not only the possible treatment and relief of pain for patients, but also various benefits such as access to ancillary social welfare, subsidies for special needs, connection with rare-disease support groups and access to information for life planning and reproductive decision-making [2]. Recent decades have witnessed increasing endeavors to improve the medical understanding of rare disease [3], especially through genetic techniques [4]. However, as Andersen’s classic healthcare utilization model suggests [5,6], accessibility to diagnosis is affected also by the characteristics of patients and the healthcare delivery system, the impacts of which, on the diagnosis of rare disease, have been the subject of few studies to date.

China has an estimated population of 20 million people with rare diseases. Over the last three decades, many advances have been made in terms of epidemiological studies, case registrations, genetic techniques, the establishment of medical networks and orphan drugs [7,8,9]. Accordingly, more needs to be done in the field of rare disorders. There is also a growing concern for the life experiences of patients with rare diseases [10]. The first national survey of rare disease patients in China, in 2016, revealed nothing but their “difficult beyond imagination” life experiences [11], including the hurdles faced in obtaining a diagnosis.

Traveling long distances for diagnosis is common in China, as healthcare, and particularly high-quality healthcare [12], is unevenly distributed across the country, despite the ongoing healthcare reforms [13]. Patient mobility also widely varies as a result of the intensification of social and income stratification and related polarization [14,15]. Considering the spatial distance between provinces and difficulties in the reimbursement of cross-provincial medical insurance [16], trans-provincial diagnosis has emerged as an area of increasing social inequality, adding to other dimensions of uneven healthcare distribution and unequal mobility of patients.

Using data garnered from the 2018 national survey of people inflicted with rare diseases in China, we studied the impact factors of trans-provincial diagnosis, mainly the geographic distribution of healthcare resources and patient mobility, based on a sample of 1531 patients residing in 31 provinces. This research provides a better understanding of the predicaments related to the diagnosis of rare disease from both institutional and socioeconomic standpoints, and thus it can inform policy-making regarding the facilitation of rare disease diagnosis and health-care planning.

2. Materials and Methods

The 2018 China Rare Disease Survey was a systematic investigation of patient access to accurate diagnosis across the country. The survey was conducted with the support of the Illness Challenge Foundation—a national umbrella organization providing support to rare disease patients. Rare disease patients are usually involved in a patient group that functions as a platform for information sharing and mutual support. The Illness Challenge Foundation helped to reach out to multiple patient groups to organize the survey. At the time of the survey, the Illness Challenge Foundation had formed an official alliance with 29 rare disease patient organizations in China. The Foundation has a wide recognition among China’s rare disease patients due to its former entity, the China-Doll Center for Rare Disorders, being the most well-known rare disease patient organization in China. Hence, distributing the survey via the Foundation’s network enabled us to reach the widest population of rare disease patients in China. Encouraged by the Illness Challenge Foundation and the patient groups, the willingness to participate in this survey was raised. As patients are widely dispersed in the country, we used online questionnaire to reach a maximum number of patients. Some 50% of the questionnaires were filled out by caregivers due to the young age or disability of the respondent. In total, 2040 valid questionnaires were collected from across the country, from which 1032 adult cases (18 years and older in 2018) and 499 child cases were identified with full information on each item for analysis, accounting for 75.1% of the total. The 1531 cases form a sample of patients, inflicted with 75 different rare diseases from across 31 provinces in Mainland China.

Logistic regression models were used to investigate the factors affecting trans-provincial diagnosis. As rare disease patients may experience several misdiagnoses, we only refer to the time and location of the accurate diagnosis to identify the trans-provincial diagnosis. The control factors were the rarity of the disease and patients’ demographics, including age, sex and ethnicity. The factors examined were the geographic distribution of healthcare resources and patient mobility.

To control the effect of different diseases, we constructed a “rarity of disease” variable by categorizing diseases into three classes based on the reported prevalence of each disease, being “extremely rare”, with an incidence below 1/100,000; “rare”, with an incidence range of 1/100,000 to 1/10,000; and “somewhat rare”, with an incidence above 1/10,000. The prevalence of each disease is listed in detail in the Appendix A. A rarer disease can be assumed to be associated with a greater possibility of trans-provincial diagnosis.

Three factors captured geographical distribution of healthcare: the number of 3-A hospitals, the number of licensed hospital doctors and the number of hospital beds in each province (all measured for 2017). Healthcare in mainland China is provided in primary care institutes, public health institutes and hospitals. Different from the patient referral systems in the USA or UK, patients in China can directly seek healthcare in hospitals. Among the hospitals, those classed as 3-A are the highest-ranking facilities in China’s hospital classification system [17]. Since an accurate diagnosis of rare disease often requires a higher level of experience and more advanced diagnostic technologies, most patients resort to 3-A hospitals for diagnosis. In this paper, we used the number of 3-A hospitals to represent the amount of high-quality healthcare in each province. Besides, two indicators widely used to measure the amount of healthcare, the number of licensed doctors and the total number of hospital beds, are also used. Due to the limited medical understanding of rare diseases, we hypothesized that only the amount of high-quality healthcare is associated with trans-provincial diagnosis outcomes. We chose not to use per capita high-quality healthcare resources as a factor, as it is more likely that total high-quality healthcare capacity is more directly linked to the attraction (or lack of attraction) of patients seeking a diagnosis in a region [18]. Data were obtained from the China Health Statistics Yearbook 2018. As Figure 1 shows, the distribution of 3-A hospitals is quite distinct from the total number of licensed doctors and hospital beds, revealing different mechanisms and patterns of high-quality healthcare and average healthcare resources distribution.

Figure 1.

Distribution of healthcare resources across 31 provinces in China in 2017.

Trans-Provincial diagnosis poses multiple challenges to the mobility of patients. Studies in Europe have revealed the effect of various factors on patient mobility, such as affordability of healthcare, patients’ physical limitations, the need to be accompanied by caregivers, transportation costs and the ability to obtain information on specialized healthcare [19,20,21,22]. For patients with rare diseases in China, the high costs involved may be the primary challenge to trans-provincial diagnosis, even though partial health insurance coverage may be available. Many rare diseases result in physical disability, making it even harder for patients to travel long distances; and even if they can travel, they usually need to be accompanied. As the disease is rare, an additional barrier may be finding the right hospital. With these considerations in mind, four groups of factors relating to the mobility of patients were examined: (1) affordability of healthcare, including factors such as family income, measured by the relative income grade in the patient’s home city, hukou status (registered as an urban or rural citizen) and medical insurance, including Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance (UEBMI) and Basic Medical Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents (BMIURR) coverage; (2) patients’ physical disability, measured by extent of dependency on assistive devices; (3) support by caregivers, measured by patients’ marital status and number of other family members, which can significantly affect the mobility of patients with physical disabilities; and (4) education level, measured by the most education years of patient and their parents, which is a surrogate for ability to find a suitable hospital. We hypothesized that a greater chance of trans-provincial diagnosis is associated with greater affordability, less disability, more support by caregivers and higher education level.

The adult and child cases were analyzed separately due to difference in the incidence of disease and the ability of the patient to act on their own. Comparing these two groups also reveals differences in attitudes of families toward, and input into, seeking diagnosis in other provinces. The data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

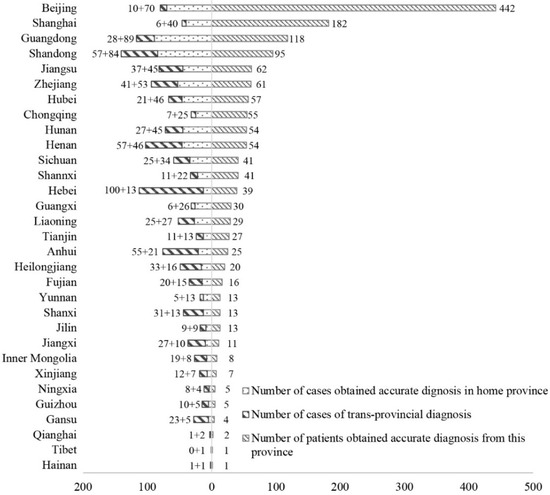

Table 1 presents a descriptive analysis of the data. Trans-Provincial diagnoses accounted for 47.2% of the total, with a slight difference between adult (47.6%) and child (46.5%) groups. As Figure 2 shows, coastal provinces delivered more accurate diagnoses and had a lower proportion of trans-provincial diagnosis. The destination hospitals were concentrated in Beijing and Shanghai, host cities of the largest number of best hospitals in China.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of trans-provincial diagnosis and the associated patients’ characteristics.

Figure 2.

Number of cases living in each province and number of accurate diagnoses obtained from each province.

The average age for adult patients was 35.5 years and 6.0 years for child patients. Overall, 53.6% of adult patients were female, and the proportion was 35.7% for child patients. About 3/4 of adult and child patients were afflicted with a disease with a medium degree of rarity. Most patients reported their family income was around or below the average of the local city. The majority of patients came from lower-ranked cities. Half of the patients held an urban hukou. Only 35.5% of adult patients were covered by UEBMI, while 53.6% of adult patients and 78.8% of child patients were covered by BMIRUP. About half of patients always depended on the assistive devices. Sixty-five percent of adult patients were married. The average longest schooling years among family members was 12.03 for adult patients and 11.18 for child patients.

The bivariate analysis in Table 2 shows that trans-provincial diagnosis was significantly associated with longer diagnosis delay, more hospitals to visit and a higher possibility of misdiagnosis, for both adult and child patients. Many patients had to resort to trans-provincial diagnosis after several failures in local hospitals.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients of correlations between trans-provincial diagnosis and variables measuring accessibility to an accurate diagnosis.

3.2. Factors Affecting the Trans-Provincial Diagnosis

For both adult and child patient groups, the dependent variable in the binary logistic regression model is a trans-provincial accurate diagnosis, in which 0 represents a diagnosis within the home province while 1 represents a diagnosis outside the home province. Among the independent variables, sex, ethnicity, hukou, marriage status and UEBMI and BMIRUP coverage are dummy variables. Based on this, a composite reference is created, being an unmarried male of Han Ethnicity with a rural hukou and with UEBMI and BMIRUP coverage. For child patients, the model setting is slightly different. The marriage status and UEBMI coverage are excluded as they are not applicable to the child. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models estimating the effects of healthcare distribution and physician mobility on trans-provincial diagnosis in adult and child patients.

The models controlled the effects of demographic characteristics of patients and the rarity of the disease. The patient’s age was significantly associated with the trans-provincial diagnosis but only affect the child group. For child patients, each additional year of age was associated with a 10.3% (OR = 1.103; 95% CI, 1.054–1.154; p < 0.001) increase in the odds of trans-provincial diagnosis. In contrast, the rarity of disease only had a significant effect in the adult group, with a higher level of rarity associated with a 41.0% (OR = 1.410; 95% CI, 1.070–1.858; p < 0.015) increase in the odds of trans-provincial diagnosis. Sex and ethnic minority did not show significance.

Regarding the impact of healthcare resource distribution, the more 3-A hospitals there are in a patient’s home province, the less likely they traveled to another province for an accurate diagnosis. An additional 3-A hospital had a 3.7% decrease in the odds of trans-provincial diagnosis for both adult (OR = 0.973; 95% CI: 0.963–0.983; p < 0.001) and child patients (OR: 0.973; 95% CI: 0.956–0.990; p = 0.003). The number of hospital beds and licensed doctors did not show significance.

Regarding the impact of physician mobility, only factors related to affordability and physical disability showed significance, but they affected adult and child groups differently. For adult patients, a higher level of family income in local city was associated with a greater likelihood of trans-provincial diagnosis (OR = 1.349; 95% CI: 1.079–1.686; p = 0.009), although patients in higher-level cities were more likely to obtain an accurate diagnosis in their home province (OR = 0.739; 95% CI: 0.671–0.812; p < 0.001). This is likely to be ascribable to the fact that high-level cities usually have more 3-A hospitals [12]. However, for child patients, the level of family income in the local city did not significantly affect the odds of trans-provincial diagnosis. An urban hukou was associated with a 46.7% (OR = 1.467; 95% CI: 1.061–2.028; p = 0.020) increase of the odds of trans-provincial diagnosis for adult patients, but showed no significance for child patients. The more severe was the disability, the less likely adult patients were to travel to other provinces. A higher level of dependency on assistive devices was associated with 13.1% (OR = 0.869; 95% CI: 0.781–0.966; p = 0.009) decrease in the odds of trans-provincial diagnosis. Nevertheless, physical disability did not show significance in the child group. Statistical significance was not found in factors related to education level and support by caregivers.

4. Discussion

Our study evaluated cross-sectional associations between geographic distribution of high-quality healthcare and successful diagnosis of a rare disease secured by trans-provincial mobility. This is an important relationship to investigate because reducing the delay of diagnosis of rare diseases can have significant benefits for patients in terms of prognosis and quality of life. The study makes a significant contribution to the diagnosis of rare diseases, as currently most concerns focus on deepening the medical understanding of rare disorders.

The 2018 China Rare Disease Survey showed that around half of patients found subsequently to have a rare disease had to travel to another province for an accurate diagnosis. Our bivariate analysis suggests that trans-provincial diagnosis was significantly associated with a more arduous experience in accessing quality healthcare, including longer waiting times, more hospitals visited for consultation and a higher propensity of misdiagnoses before a final correct diagnosis. Regression models fitted to identify significant associations with trans-provincial diagnosis identified four issues that should be taken into account in addressing a healthcare policy response.

The first is the limited impact of the rarity of disease on the patient’s healthcare utilization behavior. Disease rarity accounts for only a tiny proportion of the variability of trans-provincial diagnosis for adult patients and is not significant for children. This suggests that patients’ healthcare utilization behavior may vary significantly, even with diseases of the same degree of rarity. It also suggests that more attention should be paid to socioeconomic difficulties in accessing accurate diagnosis.

The second is the impact of the uneven geographical distribution of high-quality healthcare. This is a key factor determining the likelihood of a trans-provincial diagnosis for both adults and children. The total quantity of healthcare resources shows no significant impact, in that patients in provinces such as Henan and Hunan, where there are significant healthcare resources, still have to go to other provinces to obtain an accurate diagnosis. However, high-quality healthcare is significantly unevenly distributed in China. For example, six out of the top 10 hospitals in 2018 were located in Beijing and Shanghai [23], which could be a major reason why 40.8% of patients were finally accurately diagnosed in these two cities. To reduce the delay of diagnosis of rare diseases and to relieve the burden on patients, more high-quality hospitals are needed in the provinces in Central and West China. Moreover, as the number of patients afflicted with each rare disease is limited, specialist centers targeted at rare diseases could be useful to receive enough patients with very rare conditions and thus contribute to clinical research. These specialist centers should be developed at the national level rather than being dispersed in provinces.

The third issue is the differences in revealed behavior of families seeking an accurate diagnosis, comparing adult and child patients. Trans-Provincial diagnoses are less constrained by such factors as income and hukou for child patients than for adult patients. Put differently, the families of children with a rare disease tend to invest more in seeking an accurate diagnosis, regardless of their socioeconomic status. Particularly, as child patients get older, parents are more eager to seek treatment in high-quality hospitals, even those outside their home province. This greater effort is understandable, as the confirmation of a disease is extremely important when establishing a life plan for the child. The finding indicates that low-income families are likely to suffer a heavier burden, in that they invest a greater proportion of their family assets into seeking a diagnosis.

The fourth is the disparities in mobility among adult patients. Aside from family income, trans-provincial diagnoses were significantly affected by a patient’s physical disability and hukou status. This indicates that disparities in the mobility of adult patients should be addressed, and more support should be provided to disabled and rural patients. The result is consistent with both accessibility and social discrimination explanations: rural hukou holding adult rare disease sufferers may have a worse experience in seeking diagnosis because of greater distances, lower affordability, poorer urban knowledge and connections, and/or there may be inequalities/discrimination in some parts of the system, e.g., the institution of healthcare insurance.

As this is a pioneering investigation of the trans-regional diagnosis of rare diseases in China, we need to acknowledge its limitations. The first is the nonprobability sampling method coupled with a limited sample size may introduce the risk of sampling bias to our study. The limited number of cases in such provinces as Tibet, Hainan and Qinghai mean that the constraints of high-quality healthcare on patients’ healthcare utilization are not properly represented. The second is that some patients obtain an accurate diagnosis abroad and these cases are not well represented by the cases in this survey. Our spatial unit of analysis presents another limitation. The uneven distribution of healthcare and unequal patient mobility are also significant within a province, and a study on a finer scale would produce different results. Lastly, the study has a cross-sectional design and we acknowledge the problem of endogeneity and the risks in inferring causality. we can also not be sure, for example, of the extent to which families or individuals with rare diseases move, on a permanent or long-term basis, to big cities with better health hospitals [12].

5. Conclusions

Although the advancement of medical knowledge of rare disorders is fundamentally important in coping with rare diseases, the socioeconomic dimension of accessibility to accurate diagnoses also needs to be attended. Contrasting to the limited effect of the rarity of disease, the geographical distribution of healthcare resources and the mobility of patients have been shown to be significantly associated with the trans-provincial diagnosis of rare diseases. Among adult patients, aside from those with a poor economic status, those living in rural areas and the disabled are also less likely to travel between provinces in search of an accurate diagnosis. Families of child patients tend to pour more resources into seeking an accurate diagnosis than those with an adult patient, regardless of the family’s socioeconomic status, and this increases the economic burden on low-income families. Moreover, more systematic surveys on the accessibility to rare disease diagnoses are needed in the future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y., D.D., S.H. and C.W.; Methodology, X.Y. and S.H.; Software, X.Y.; Validation, S.H. and C.W.; Formal analysis, X.Y. and S.H.; Investigation, X.Y. and D.D.; Data curation, D.D.; Writing—original draft preparation, X.Y.; Writing—review & editing, D.D., S.H. and C.W.; Visualization, X.Y.; Project administration, S.H.; Funding acquisition, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 41671153.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Illness Challenge Foundation for its support in the survey.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Rarity of each rare disease and its prevalence.

Table A1.

Rarity of each rare disease and its prevalence.

| Disease | Prevalence | Data Source of Prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Rare (Prevalence < 1/100,000) | |||

| 1 | 1q44 microdeletion syndrome | <1/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 2 | Acute transverse myelitis | 1/1,000,000 ~ 1/250,000 | orpha.net |

| 3 | Alexander disease | 1/2,700,000 | orpha.net |

| 4 | Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome-AHUS | 1–9/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 5 | Bartter syndrome | 1/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 6 | Erythrokeratoderma | 200 cases reported | orpha.net |

| 7 | GM1 gangliosidosis | 1/100,000–1/200,000 in live births | orpha.net |

| 8 | Growth hormone deficiency | 1–9/1,000,000 | Stanley T. (2012). Diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency in childhood. Current opinion in endocrinology, diabetes, and obesity, 19(1), 47–52. doi:10.1097/MED.0b013e32834ec952 |

| 9 | Lymphangioleio-myomatosis | 1–9 /1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 10 | Massive osteolysis/Gorham-Stout disease | 300 cases reported | orpha.net |

| 11 | Metachromatic leukodystrophy | 1–9 /1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 12 | Mitochondrial encephalopathy | 1–9/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 13 | Niemann-Pick disease | <1/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 14 | Peutz–Jeghers syndrome | 1–9/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 15 | Spondyloepiphyseal Dysplasia Congenita | 1 per 100,000 live births | orpha.net |

| 16 | Triple-A syndrome (Allgrove syndrome) | <1/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| Rare (1/10,000 < Prevalence < 1/100,000) | |||

| 17 | Acromegaly | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 18 | Adrenal Hypoplasia Congenita | less than 1/12,500 births | AvRuskin, T., Krishnan, N., & Juan, C. (2004). Congenital Adrenal Hypoplasia and Male Pseudohermaphroditism Due to DAX1 Mutation, SF1 Mutation or Neither: A Patient Report. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism, 17(8), 1125–1132. |

| 19 | Albinism | 1/10,000–1/20,000 | Mártinez-García, M. and Montoliu, L. (2013), Albinism in Europe. J Dermatol, 40: 319–324. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.12170 |

| 20 | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 21 | Angelman syndrome | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 22 | Anti-Neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis | 4.6–18.4/100,000 | Watts, R., Mahr, A., Mohammad, A., Gatenby, P., Basu, N., & Flores-Suárez, L. (2015). Classification, epidemiology and clinical subgrouping of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 30(Suppl1), I14–I22. |

| 23 | Behcet’s disease | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 24 | Cerebral palsy | 1.5–4/1000 in live births | Stavsky, M., Mor, O., Mastrolia, S., Greenbaum, S., Than, N., & Erez, O. (2017). Cerebral Palsy-Trends in Epidemiology and Recent Development in Prenatal Mechanisms of Disease, Treatment, and Prevention. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 5, 21. |

| 25 | Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 26 | Cri-du-chat syndrome | 1/20,000-1/50,000 newborns | orpha.net |

| 27 | Crohn’s disease | 1.2-21.2/100,000 | Prideaux, L., Kamm, M. A., De Cruz, P. P., Chan, F. K., & Ng, S. C. (2012). Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology, 27(8), 1266–1280. |

| 28 | Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 29 | Eisenmenger’s syndrome | 1–9/1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 30 | Epidermolysis bullosa | 1–9 /1,000,000 | orpha.net |

| 31 | Fabry disease | 1/100,000 | Branton, M. H., Schiffmann, R., Sabnis, etc. (2002). Natural history of Fabry renal disease: influence of α-galactosidase A activity and genetic mutations on clinical course. Medicine, 81(2), 122–138. |

| 32 | Gaucher disease | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 33 | Glycogen storage disease due to acid maltase deficiency | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 34 | Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 35 | Hemophilia | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 36 | Hepatolenticular degeneration/Wilson disease | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 37 | Huntington’s disease | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 38 | Ichthyosis | average of subtypes | orpha.net |

| 39 | Idiopathic Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism | 1/4000–1/10,000 in males, and 2 to 5 times less frequent in females | Silveira, L. G., & Latronico, A. C. (2013). Approach to the Patient With Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 98(5), 1781–1788. |

| 40 | Immunologic thrombocytopenic purpura | 5/100,000 | Fogarty, P. F., & Segal, J. B. (2007). The epidemiology of immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Current opinion in hematology, 14(5), 515–519. |

| 41 | Kallmann Syndrome, KS | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 42 | Mucolipidosis type IV | 1/40,000 births | orpha.net |

| 43 | Mucopolysaccharidosis | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 44 | Multiple Sclerosis | 1–2/100,000 | Cheng, Q, Cheng, X-J, & Jiang, G-X. (2009). Multiple sclerosis in China—history and future. Multiple Sclerosis, 15(6), 655–660. |

| 45 | Myasthenia Gravis | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 46 | Neuromyelitis optica | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 47 | Noonan syndrome | 1/1000–1/2500 live births | orpha.net |

| 48 | Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 49 | Prader-Willi syndrome | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 50 | Pseudoachondroplasia | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 51 | Pseudomyxoma peritonei | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 52 | Pulmonary hypertension | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 53 | Spinal muscular atrophy | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 54 | Spinocerebellar ataxias | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| 55 | Systemic Vasculitis | 1–2/100,000 | Lane, S., Watts, E., & Scott, R. (2005). Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis. Current Rheumatology Reports, 7(4), 270–275. |

| 56 | Takayasu arteritis | 1–9/100,000 | orpha.net |

| Somewhat rare (Prevalence >1/10,000) | |||

| 57 | Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 58 | Fuchs’ syndrome | 3.7–9.2% in patients over 50 years of age | Pilger, Daniel, Brockmann, Claudia, Maier, Anna-Karina B., & Bertelmann, Eckart. (2019). Predictive Factors for Clinical Outcomes after Primary Descemet’s Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty for Fuchs’ Endothelial Dystrophy. Current Eye Research, 44(2), 147–153. |

| 59 | Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 60 | Hyperammonemia | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 61 | Hypopituitarism | 4.5/10,000 | Aimaretti G, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Stalla GK, Ghigo E (2007). Hypopituitarism. Lancet. 369 (9571): 1461–70. |

| 62 | Isolated spina bifida | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 63 | Keratoconus | 5.4/10,000 | Gokhale N. S. (2013). Epidemiology of keratoconus. Indian journal of ophthalmology, 61(8), 382–383. doi:10.4103/0301-4738.116054 |

| 64 | Klinefelter syndrome | 1/1,000 | Wattendorf DJ, Muenke M. (2005) Klinefelter syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 72(11):2259–62. |

| 65 | Marfan Syndrome | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 66 | Neurofibromatosis | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 67 | Osteogenesis imperfecta | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 68 | Pemphigus vulgaris | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 69 | Primary adrenal insufficiency/Addison’s disease | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 70 | Stargardt disease | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 71 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 72 | Systemic sclerosis | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 73 | Tuberous sclerosis complex | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 74 | Turner syndrome | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

| 75 | Uveitis | 1–5/10,000 | orpha.net |

References

- Austin, C.P.; Cutillo, C.M.; Lau, L.P.L.; Jonker, A.H.; Rath, A.; Julkowska, D.; Thomson, D.; Terry, S.F.; de Montleau, B.; Ardigò, D.; et al. Future of Rare Diseases Research 2017–2027: An IRDiRC Perspective. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2018, 11, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esquivel-Sada, D.; Nguyen, M.T. Diagnosis of rare diseases under focus: Impacts for Canadian patients. J. Community Genet. 2018, 9, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawkins, H.J.; Draghia-Akli, R.; Lasko, P.; Lau, L.P.L.; Jonker, A.H.; Cutillo, C.M.; Rath, A.; Boycott, K.M.; Baynam, G.; Lochmuller, H.; et al. Progress in rare diseases research 2010–2016: An IRDiRC perspective. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2018, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boycott, K.M.; Hartley, T.; Biesecker, L.G.; Gibbs, R.A.; Innes, A.M.; Riess, O.; Belmont, J.; Dunwoodie, S.L.; Jojic, N.; Lassmann, T.; et al. A Diagnosis for All Rare Genetic Diseases: The Horizon and the Next Frontiers. Cell 2019, 177, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, R.M. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med. Care 2008, 46, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Wang, Y.O.; Li, L.; Guo, J.J.; Wang, J.B. China’s first rare-disease registry is under development. Lancet 2011, 378, 769–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cui, Y.; Zhou, X. Rare diseases research in China: Opportunities, challenges, and solutions. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2012, 1, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Feng, S.; Liu, S.; Zhu, C.; Gong, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S. National Rare Diseases Registry System of China and Related Cohort Studies: Vision and Roadmap. Hum. Gene Ther. 2018, 29, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.B.; Guo, J.J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.D.; Sun, Z.Q.; Zhang, Y.J. Rare diseases and legislation in China. Lancet 2010, 375, 708–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.; Wang, Y. Challenges of rare diseases in China. Lancet 2016, 387, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; He, S.; Wu, D.; Zhu, H.; Webster, C. Examining the Multi-Scalar Unevenness of High-Quality Healthcare Resources Distribution in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.; Shallcross, D. Geographic distribution of hospital beds throughout China: A county-level econometric analysis. Int. J. Equity Health 2016, 15, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wan, G. Income polarization in China: Trends and changes. China Econ. Rev. 2015, 36, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, R.E.; Liu, F.; Lu, X.; Wang, W. Emerging issues in public health: A perspective on China’s healthcare system. Public Health 2011, 125, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, A. Hukou and health insurance coverage for migrant workers. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2016, 45, 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.R.; Liu, G.G. China’s Healthcare System and Reform; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Balia, S.; Brau, R.; Marrocu, E. Interregional patient mobility in a decentralized healthcare system. Reg. Stud. 2018, 52, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurordis. The Voice of 12,000 Patients. Experiences and Expectations of Rare Disease Patients on Diagnosis and Care in Europe; Eurordis: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Glinos, I.A.; Baeten, R.; Helble, M.; Maarse, H. A typology of cross-border patient mobility. Health Place 2010, 16, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenmöller, M.; McKee, M.; Baeten, R. Patient Mobility in the European Union: Learning from Experience; World Health Organization: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lunt, N.; Mannion, R. Patient mobility in the global marketplace: A multidisciplinary perspective. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2014, 2, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asclepius. Annual Report on China’s Hospitals Competitiveness (2018–2019); Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).