Abstract

Though the demand for organic grains is increasing, domestic supply is falling short. One of the major barriers to entry in the organic grain market for producers is the inability to identify an appropriate buyer, as well as a lack of understanding buyer perceptions, assistance offered, and contracting strategies. While classifications of organic producers exist, and have helped researchers and policymakers develop incentives, no such classification exists for organic grain buyers. Previous works have identified communication gaps between buyers and producers of organic grains, yet buyers’ beliefs and requirements regarding organic grain are not well documented in literature. Drawing from the personal values theory, this study proposes the categorization of organic grain buyers based on their commitment to the organic industry, with categories such as committed organic and pragmatic organic. We profiled grain purchases, buying arrangements, grain requirements, relationships, and business characteristics by buyer type. Means comparisons among groups showed that committed organic buyers seem to be primarily driven by social focus values, while pragmatic organic buyers tend to show values related to personal focus. A principal component analysis suggested the existence of three components constructed by contract-, perceptions-, and relationship-oriented characteristics in buyers. Our results allowed us to identify potential marketing opportunities by providing insight regarding types of assistance offered by buyers, how to build and maintain a relationship with buyers, types of purchasing agreements used, and purchasing agreement characteristics and requirements. Industry stakeholders can use this information to identify appropriate buyers based on times contracts are signed, payment timing, storage and transportation requirements, and the amount of organic practice documentation buyers require. Our categorization can provide the foundation for further research in the organic grain industry.

1. Introduction

Organic markets in the US have been steadily growing since 1990, with organic sales rising nearly 20 percent annually [,]. By 2015, organic food sales in the US totaled over $43 billion, a notable increase from $3.6 billion in 1997 [,]. More recently, organic demand grew at a rate of 6.4% in 2017, a much higher growth rate than for conventional foods (1.1% for the same year) [,]. The aforementioned growth in demand for organic products demonstrates the relevance of organic products in the US economy. This growth, coupled with organic price premiums [], creates opportunities for organic agricultural operations to respond to a market facing high demand. However, supply of organic products has not grown proportionally to demand.

Though farm-gate sales of organic products account for 2% of US farm-gate sales of all agricultural products [,,], this is a growing billion-dollar industry that has great significance in the US economy. Organic farm-gate sales can be separated into milk and eggs at 31%, livestock and poultry at 12%, and field crops (grains) at 11% [,]. The remaining 46% of organic production is composed of fruits, vegetables, and other specialty crops [,,]. The importance of organic grains is notable, as 54% of organic food sales are either from grains themselves (11%) or livestock production systems that require grains as an input (43%).

Although demand for organic grains is experiencing rapid growth, the supply of organic grains produced domestically is falling short []. Economic theory suggests that if domestically produced organic grains were desired, market demand would encourage the supply of domestic organic grains []. Several factors have been reported to influence the shortage of supply, such as owner demographics, market access, and land tenure []. Other barriers to certify organic grains are technical limitations (e.g., lack of information for obtaining organic certification and organic production practices), financial constraints and lack of financial incentives, lack of compatibility with the current farming system, and lack of infrastructure [,,,]. To illustrate, buyers purchasing USDA-certified organic grains require, at the very least, grains to be certified by a USDA-NOP-accredited third-party agency and grow products according to USDA organic standards. Organic certified grains have been grown on land that has been free of prohibited substances (e.g., synthetic fertilizers and genetically modified agricultural technologies) for a 3-year transition period []. Additionally, organic seeds must be used by an operation, when available. Consistent across the literature, a lack of information regarding marketing opportunities appears as a major barrier to organic grain supply. Though previous studies have identified communication gaps between buyers and producers of organic grains, buyers’ beliefs and requirements concerning organic grain are not documented in literature.

A deeper understanding of organic grain buyers would provide information that can be used to strengthen the organic grain market in the US. For instance, information on the ways buyers build relationships would allow producers to identify potential buyers and understand how to forge long-term purchasing agreements. To accurately understand marketing opportunities available to organic producers, it is imperative to understand how buyers of organic grains operate. Thus, business demographics, buyer perceptions of the organic grain market, relationship factors, and characteristics of purchasing agreements are areas which need to be explored in detail to facilitate the growth of the organic grain market.

One approach to understanding buyer operations and marketing opportunities in the organic grain industry is to categorize buyers. These comparisons can allow for pairwise comparisons to assist producers and other industry stakeholders in identifying specific types of buyers and their preferences. This categorization can also help stakeholders understand the most salient factors influencing the drafting of contracts and assistance provided to farmers. Reports of bifurcation within the organic industry [] motivates this study to shed light on the market standards for organic grains sourced in the North Central Region. While researchers have provided categorizations of organic producers [,,,,], no such classification exists for organic grain buyers.

We draw from the Personal Values (PV) theory [] as a framework to understand the motivations that guide the behavior of organic grain buyers. We proposed two buyer classifications that provide a greater understanding of the organic grains market. The first classification leverages on the theoretical framework on organic farmers developed by Darnhofer et al. [] to categorize buyers as committed organic and pragmatic organic grain buyers. The second categorization builds from a principal component analysis to explore the major factors influencing farmer–buyer relationships: one in which buyers prioritize contract characteristics (personal focus values) and another representing buyers’ perceptions of the sustainability and integrity of the organic industry (social focus values).

Buyer classifications presented in this work are intended to provide information on buyers operating in the Midwest, the largest supplier region of organic grains. Buyer categorization can also assist researchers and policymakers to tailor incentives and policies that support the success of the organic grain industry. Our findings can shed light on the marketing opportunities available to producers of organic grains in the Midwest. Our study aims to disentangle the organic grain industry and help bridge communication gaps between stakeholders. In addition to providing information, this work also provides a theoretical foundation for buyer classifications which can be further developed and explored in future research.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Current Supply of Organic Grains

A Mercaris survey of domestic organic grain producers across the US revealed feed-grade organic corn was supplied primarily by growers in the Midwest region (Midwestern states included Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio, and Wisconsin): 71.6% in the 2017/2018 marketing year. Marketing years for grains span calendar years and are often written to include both calendar years. The US marketing year for grains starts on June 1st and ends on May 31st of the following year for barley and oats and starts on September 1st and ends on August 31st of the following year for other grains [].

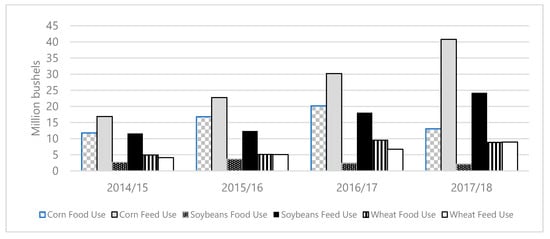

Canada, the Eastern US, the High Plains, and the Western US supplied the remaining amounts. The report revealed that organic feed-grade soybeans were also primarily produced in the Midwest (83.9% of domestic supply). Food-grade organic soybeans were reported to be produced largely in the Midwest (47.3%). The report revealed that feed-grade organic wheat production is more spread out than corn and soybean []. About 42.5% of the domestic organic wheat was supplied by the Western US, followed by the Eastern US, Midwest, High Plains, and Canada. This dispersion is likely related to the production requirements for wheat. Average prices for organic corn, soybeans, and wheat are reported in Table 1. Differences in prices for food- and feed-grade corn, soybeans, and wheat may be due to quality characteristics, transportation costs, and market supply and demand trends. Figure 1 illustrates the demand for organic corn, soybeans, and wheat for the 2014–2018 marketing years.

Table 1.

Comparison of average organic prices for corn, soybeans and wheat in 2017/2018.

Figure 1.

Organic grain demand in the US from 2014–2018. Data adapted from Mercaris.

As organic production systems rely on crop rotation to enhance productivity and stability, small or minor organic grains have been making an appearance on the grain market [,,]. While small grains are not considered major cash crops like corn, soybeans, or wheat, they are vital to successful organic systems []. Small grains typically used in organic production include sorghum, rice, rye, barley, peas, and oats, depending on farm location. At present, markets for these products are not readily established, like those of typical cash crops, and little data is available on the organic production of these smaller grains []. The USDA reports sorghum production increased from 5.03 million acres in 2017 to 5.29 million acres in 2018 [,]. Similarly, rice production increased from 2.46 million acres over the same time period [,]. Barley production in the US increased from 2.48 million acres in 2017 to 2.55 million acres in 2018, while cash bid prices between 2018 and 2019 decreased from $6.80/bushel to $6.00/bushel []. Oat production increased from 2.59 million acres in 2017 to 2.89 million acres in 2018, while cash bid prices between 2018 and 2019 decreased from $4.00/bushel to $3.50/bushel []. On the other hand, farmland dedicated to rye production decreased from 1.97 million to 1.96 million acres between 2017 and 2018. Edible pea production in the US decreased from 1.13 million planted acres in 2017 to only 0.88 million acres planted in 2018 [,].

2.2. Barriers in Domestic Supply

Organic grains, such as corn, soybeans, and wheat, are supplied to the US by both domestic production and imports [,]. Due to lack of domestic supply for organic grains, imports have important market shares for organic soybeans, corn, and wheat []. For example, in 2015/2016, organic grain demand was met by imports as high as 83% for organic soybeans, 54% for organic corn, and 12% for organic wheat []. While import volumes have declined (corn and soybeans) or remained relatively steady (wheat) over the past several years, organic corn was still supplied by imports for the 2017/2018 marketing year [].

Previous literature extensively describes the lack of information present in the organic grain sector as one of the main drivers of the supply lag. Information gaps include the lack of technical information and market information [,]. Strochlic and Sierra [] reported that technical assistance, such as agronomic support and production information, is often limited for many organic producers. Many producers have reported a lack of awareness of how to receive technical assistance when it was available [,]. To complicate matters further, technical assistance, such as university extension, was reported to often discourage organic agriculture, and private technical assistance is typically expensive and financially unattainable for smaller operations [,].

Meeting organic certification is only half the battle for producers. Peterson et al. [] reported that many farmers suggested that buyers of organic grains often have more extensive and less forgiving requirements for grain production practices, record keeping, and quality attributes than those necessary for USDA organic certification. Torres and Marshall [] reported that one of the most important reasons why some farmers are dropping the certification program are meeting marketing standards. For example, while production of organic grains is more successful using a diverse crop mix, finding buyers for less-demanded grains in an organic rotation may be challenging []. Additionally, organic grains may be sold to different buyers in various locations depending on the grain mix and the demand for that specific grain []. The need to sell grain to multiple buyers can often lead to buyer demands differing in terms of quality requirements such as grain moisture level at harvest, sampling times and methods, and storage requirements [], creating further uncertainty and risk for producers.

2.3. Building a Classification of Organic Grain Buyers

2.3.1. Organic Producer Classification Framework

Previous works have suggested a shift of organic agriculture from a social movement to an institutional movement [,,]. The presence of institutionalism suggests that, as the industry grows, players in the industry will also grow and shift motivations from environmental sustainability to profitability []. Thus, it is expected that, as the organic grain industry grows, the market is likely to gain similarities to the conventional grain market.

Buck et al. [] proposed a bifurcation in the organic industry as a result of conventionalization. Bifurcation can develop as larger businesses enter the organic industry, increasing the length of supply chains [,]. On the other hand, smaller producers deeply rooted in the sustainability of organic production still exist and sell in direct-to-consumer markets [,]. This bifurcation in the organic grain industry can be noted by the presence of different types of grain buyers and distributors. Buyers that purchase grain for resale, such as brokers, traders, and exporters, likely diversify their purchases to cater to different customers. Additionally, buyers that resell grains serve larger markets than buyers that process grains for value-added products. Oh the other hand, users are those buying organic grains for processing, feed mills, flour mills, or livestock production [].

The bifurcation in the organic industry created as a result of conventionalization has been examined in the literature. Studies have described the bifurcation in the organic industry as pragmatic vs. pure [], agribusiness vs. lifestyle [], and organic lite/shallow vs. organic deep []. More recently, Constance et al. [] studied the bifurcation in the organic industry in Texas. The classification reported that organic producers were more profit driven than non-organic producers []. Consistent with Buck et al. [], organic producers were noted to have been farming longer and have a larger labor force than non-organic producers [].

Darnhofer et al. [] proposed a framework that characterized organic producers based on their level of commitment to organic agriculture. Committed organic growers are those devoted to their production system and are not considering switching to conventional due their lack of motives or interest. Alternatively, pragmatic conventional growers are those willing to consider organic certification if there are the necessary financial conditions (i.e., price premiums, market demand).

2.3.2. A Need for Buyer Classification

Little work has been conducted to gain an understanding of buyers of organic grains. Data availability and problems identifying buyers of organic grains have been cited as major barriers to understand buyer preferences and behavior [,]. Without more information pertaining to buyers’ preferences and standards for organic grains, growth of the domestic organic grain industry may continue to lag. In addition to a limited number of producers entering certified organic grain production, those already participating in the market may not receive the best price possible due to a lack of marketing networks in the organic sector. Providing insight into marketing opportunities available to organic grain producers may help to build marketing networks and improve the overall infrastructure of the organic grain market. This increased understanding will give the market more transparency, allowing for easier identification of buyers and long-term sustainability.

One approach to understanding buyer operations and marketing opportunities available to organic producers is to categorize buyers and understand their preferences for purchasing agreements and relationship factors. Building from Darnhofer et al. [], this study provides a categorization of organic grain buyers in the Midwestern US as pragmatic organic and committed organic buyers and compares purchasing agreements, buyers’ preferences and requirements, and market standards. We defined committed organic buyers as those purchasing organic grains but refraining from purchasing conventional grains due to being deeply invested in organic grain production and interested in the success of the organic grain industry. Thus, committed organic buyers may purchase transitioning and non-GMO grains as a way of assisting producers during the transition to certified organic production. Pragmatic organic grain buyers were defined as those that purchase organic, transitioning, and non-GMO grains along with conventional grains. We expect pragmatic organic growers will be attracted to the organic grain industry due to economic opportunities and access to new markets.

Committed organic buyers can be viewed as philosophically invested in the success of organic agriculture [,,,]. Previous literature suggests buyers that are more committed to the success of the organic grain industry are likely to be more philosophically and environmentally driven than those less committed [,,]. Having more of a philosophical interest in the organic grain industry likely drives the committed organic buyer to ensure the growth and success of the industry. Since we expect committed organic buyers are deeply rooted in the philosophy of organic, they are likely to prioritize forging stronger relationships with grain suppliers than pragmatic organic buyers.

As committed organic buyers are invested in the growth and success of the organic grain market, they will likely be more concerned about organic integrity than pragmatic organic buyers. If organic integrity is compromised, a negative perception of the organic grains market may arise []; thus, requiring documentation of proper organic and IP practices ensures that organic integrity is not compromised []. The comparison between committed organic and pragmatic organic buyers will identify differences in business demographics, perceptions of the organic grain market, characteristics of purchasing agreements, and relationship factors. These characteristics can serve as a foundation for producers developing an understanding of the organic market and marketing opportunities available.

2.3.3. Personal Values Theory as A Way to Understand Behavior

We draw from the Personal Values (PV) theory [] as a framework to understand the motivations that guide buying behavior among grain buyers. This theory has been broadly used in consumer research to help understand the importance of personal values driving the buying decision-making process. Other studies using the PV framework in the organic industry include Tey et al. [] studying values and certification adoption; Zepeda and Deal [] investigating purchasing of organic and local foods; and Belows et al. [] relating the barriers to consumption in organic products. To our knowledge, no study has used PV theory to understand the values and purchasing behavior of organic grain buyers.

According to Schwartz [], consumption is determined by motivations (values). Values are organized in a circular continuum, represented by diametrically opposed values to help explain how the presence or absence of them drive purchasing behavior. Values are organized into two superior categories (i.e., social and personal focus) and four higher order values (i.e., self-transcendence, conservation, openness to change, and self-enhancement) []. Values in the social focus category, such as self-transcendence and conservation, are opposed to those in the personal focus category, which is consistent with our proposed bifurcation of the organic industry.

Given the proposed buyer categorization, we expect that committed organic buyers are more likely to be driven by values in the social focus or organic categories, while pragmatic organic buyers may be motivated by constructs from the personal focus. For example, we hypothesized that committed organic buyers are guided by self-transcendence and conservation values to include an act of God clause in contracts as a way to support organic growers and the success of the organic grain industry. In this case, buyers are willing to compromise their own interests for the sake of others by drafting contracts that are flexible for farmers. Similarly, we hypothesized that committed organic buyers, driven by social values, are more likely to support the integrity of the organic industry by providing forms of agronomic or certification assistance to their suppliers. Placing importance on preserving the organic industry can also help preserve the environment and economic growth of communities [].

On the other hand, we hypothesized that pragmatic organic buyers are guided by values linked to self-enhancement and openness to change. We expect that pragmatic organic buyers are more likely to require visits to farms, storage, and cleaning tags as a way to control the quality of the grains purchased (i.e., self-enhancement values). In other words, pragmatic organic buyers may be more likely to pursue their own interests to assure profitability in the industry [].

To summarize, we expect that pragmatic organic buyers are more focused on unilateral goals, while committed organic buyers are more driven by goals that benefit the organic industry. The PV framework helps us to understand the importance of contracting, assistance, and requirements in how buyers forge relationships.

3. Data and Methodology

This study aimed to categorize buyers of organic grains and identify their preferences, requirements, and purchasing agreements for organic grains in the Midwestern US. Data for this study were collected using a mixed-methodology approach including telephone and web-based surveys. We targeted buyers of organic, transitioning, and non-GMO grains in IL, IN, IA, KS, MI, MN, MO, ND, NE, OH, SD, and WI operating in 2018. Including information on transitioning and non-GMO grains can help us understand the purchasing behavior of buyers across categories. A list of 255 unique operations was compiled by leveraging personal contacts and networking, as well as online searches and databases such as The non-GMO Sourcebook [], the USDA Organic Integrity Database [] and the Mercaris list of subscribers. Potential respondents were contacted via telephone and email to schedule a 30- to 45-min telephone survey. As suggested by Dillman, et al. [], a $50 Amazon gift card was included in the invitation email as an incentive to increase survey participation. Following best practices for data collection [], three reminders were sent with a 2- to 3-week interval to non-respondents.

Sixteen weeks after the data collection started, we invited no respondents to complete a web-based questionnaire. The online questionnaire took, on average, 30 min to complete. The motivation to combine a telephone and online questionnaire follows (1) the screening of potential respondents that are directly involved with the purchasing of grain and (2) the increase in response rate (e.g., telephone questionnaire in the first stage and online questionnaire for no respondents in the second stage) [,].

Of the 255 unique operations identified and contacted, we gathered 45 completed surveys. The response rate for this study was 18%, which is considered to be acceptable for a study of this design []. Of the 45 responses, 21 (47%) responses were collected via phone, with the remaining 24 (53%) responses collected via the online questionnaire. Questions included types of grains purchased, types and characteristics of purchasing agreements used, purchases of imports and minor grains, handling and transportation requirements, relationships with producers, perceptions of the organic grain market, perceptions of the organic market in general, and business demographics. We asked grain buyers to select the type of grains purchased in 2017, including organic certified, transitioning to organic, non-GMO, and conventional. Respondents were self-identified as business owners, managers, and/or executive board members for smaller operations, and grain brokers, traders, and merchandisers for larger operations. We categorized users as those who reported their operation as a feed mill, livestock producer, processor, or flour mill. Based on Darnhofer et al. [], committed organic buyers were those purchasing organic, transitioning, and non-GMO but not purchasing conventional grains. Pragmatic organic buyers were those buying conventional, organic, transitioning, and non-GMO grains. Of the 45 responses, 27 (60%) buyers were committed, while 18 (40%) buyers were pragmatic.

A chi-square (χ2) analysis for binary variables and a Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for categorical and continuous variables revealed that data collected from phone surveys and the online questionnaire were statistically similar. To illustrate, the underlying distributions of 29 out of 30 variables were statistically similar, and, consequently, we pooled the data from online and phone surveys. Table 2 illustrates the variables used in the study, as well as their descriptive statistics for the entire sample. Results from a Shapiro–Wilk Test suggested the variables were not normally distributed, thus creating the need for non-parametric analyses. We made multiple comparisons among means using a test of proportions via a chi-square (χ2) analysis for binary variables and a Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for continuous and categorical variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables for responses gathered via a survey of organic grain buyers.

To create richer buyer profiles, we conducted a principal component analysis as a method to uncover common buyer characteristics, preferences, and perceptions. The principal component analysis identified the relative importance of the explanatory variables for committed organic and pragmatic organic buyers while simultaneously controlling for any collinearity among them. Similar to other studies with small sample sizes [,], we ran the principal component analysis to address sample size issues [] in Stata (release 14; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). A FACTORTEST analysis showed that the data had sufficient intercorrelations to conduct the analysis (p < 0.01) and shared variances proved sampling adequacy for the principal component analysis [].

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sample Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 shows grain purchases, characteristics of purchasing agreements, relationships with suppliers, buyers’ perceptions, and business demographics for the entire sample of organic grain buyers. Buyers reported purchasing organic grains mainly from farmers (98%). About a third of buyers purchased imported organic grains in 2017. About half of all the organic and non-GMO grains were purchased through contracts. Alternatively, a smaller portion of transitioning grains were procured through contracts (18%) than other types of grains. Over a third of contracts included an “act of God” clause. Most grains were contracted pre-planting (76%) in 2017, followed by post-harvest contracts. Over a third of all contracts were drafted receiving input from farmers. The most common sampling grain timing was at delivery (67% of farmers) followed by before delivery (58%). The most common buyer requirements were a clean truck affidavit (82% of farmers), followed by security tags or seals (51%) and visits to farms (16%).

The most useful sources of communication to build relationships with new suppliers were farmers and trade associations (53%), followed by in-house programs (44%). Over half of buyers provided agronomic support on the certification program to growers. The most important factors to build and maintain relationships with suppliers were quality of grain supplied (82%) followed by flexibility on time of delivery and payment (73%) and length of purchasing agreement (69%). Almost two-thirds of buyers perceived there to be a shortage of domestic organic grain. Interestingly, over half of buyers reported a lack of transparency in the certification process for imported organic grains, and a similar percentage agreed that imported organic grains are cheaper than domestic ones. Only a third expected that future prices of organic grains would increase. Two thirds of buyers were grain users (e.g., feed mills, livestock producers, processors, or flour mills). Buyers in our sample reported having, on average, 118 employees and average gross sales in 2017 between $5 and $20 million.

4.2. Committed Organic vs. Pragmatic Organic Buyers

Mean comparisons of committed organic grain buyers (N = 27) and pragmatic organic grain buyers (N = 18) are presented in Table 3. Results suggest that organic feed- and food-grade grains have different demand among pragmatic organic and committed organic buyers. For example, pragmatic organic buyers purchased, on average, a higher percentage of feed-grade grains for all types of grains (p = 0.03) when compared to the committed organic farmers. The growth of organic meat, poultry, and dairy industries in recent years [] is likely to be driving pragmatic organic buyers to capitalize on the higher demand for feed-grade organic grains. This is especially true if we consider pragmatic organic growers to be attracted to the organic grain industry due to economic opportunities and access to new markets.

Table 3.

Comparison of committed organic and pragmatic organic buyers.

Our results confirmed our hypothesis that committed organic buyers tend to support the sustainability of the organic grain industry. One way for them to support the long-term success of the organic industry is by building long-term relationships with their grain suppliers. We hypothesized that two ways of maintaining good relationships are by drafting flexible purchasing agreements and providing agronomic or transition assistance to farmers. Our results show that more committed organic buyers tended to, on average, receive input from farmers (46.0%) when drafting contracts than pragmatic organic buyers (20.72%) (p = 0.05). As hypothesized, it was more common for committed organic buyers to include an “act of God” clause in their contracts (43.1%) than pragmatic organic buyers (21.35%) (p = 0.04). Act of God terms in grain contracts release growers from meeting grain delivery obligations in case uncontrollable events cause a shortage of the contracted product. Our findings suggest that committed organic buyers tend to be more invested in the success of the organic grain industry, aligning with the committed organic producer classifications outlined by Darnhofer et al. [].

A larger percentage of committed organic buyers perceived that flexibility in time of delivery or payment is an important factor to build and maintain those relationships (85%) when compared to pragmatic organic buyers (56%) (p = 0.03). Similarly, quality of grain sourced was placed as of higher importance among more committed organic buyers (96%) than their counterparts (61%) (p < 0.01). As buyer–farmer relationships have a higher importance for committed organic buyers, their perceptions regarding how to build and maintain relationships with producers also differ from their pragmatic counterparts.

Contrary to our hypotheses, pragmatic organic buyers placed less importance on requiring visits to their suppliers’ operations than their counterparts (p = 0.10). We expected that pragmatic organic buyers, driven by personal focus values, will require farmers to provide more cleaning, delivery, storage, and visits to the farm. Our results suggest that suppliers intending to sell grains to committed organic buyers should be willing to allow them farm visits. A higher percentage of committed organic buyers agreed there is a lack of transparency in the certification process for imported organic grains than their counterparts (p = 0.07). With committed organic buyers philosophically invested in the success of organic grains, the perceived lack of transparency from imported organic grains may reflect their desire for the domestic organic industry to grow.

Significant differences in business characteristics between committed organic and pragmatic organic buyers were related to size. Pragmatic organic buyers reported a bigger number of full- and part-time employees (p = 0.07) as well as more gross sales (p = 0.0) in 2017 than their counterparts. A smaller labor force could suggest lower administration capacity and a delaying chain of custody paperwork []. Committed organic buyers’ gross sales for 2017 were between $5 and <$20 million, while pragmatic organic buyers reported gross sales of more than $20 million for the same year.

Drawing from the PV theory, the fact that committed organic grain buyers seem to be more invested in the success of the organic grain industry suggests they may be driven by values related to social focus (i.e., self-transcendence, universalism) and conservation (i.e., societal security). For example, behavior related to flexible purchasing agreements and building long-term relationships with farmers can be linked to committed organic buyers valuing environmentally and socially friendly agricultural systems. Our finding that committed organic buyers tend to value transparency in the certification process and flexible contract terms more than their pragmatic counterparts reinforce this perspective [].

4.3. Principal Component Analysis

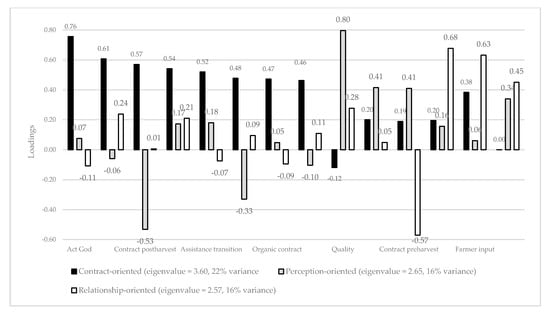

Results from the principal component analysis provided further understanding on what committed organic and pragmatic organic buyers prioritize when building purchasing relationships with farmers. The analysis yielded three components (Figure 2), where the first component represents buyers that rank higher loadings on contract characteristics, the second component highlights buyer’s perceptions, and the third component ranks higher loadings on relationship-oriented variables. Figure 2 reports the significant loadings (>0.40) of each variable included in the two retained components. Rotated principal components with the eigenvalues of the retained principal components are listed in the legend. The three retained components represent 54% of the response variance, given by 22%, 16%, and 16% of the variance from the first, second, and third components, respectively.

Figure 2.

Rotated principal components loadings.

The first component features eight significant loadings, related to act of God (0.76), shortage of domestic grains (0.61), contracting post-harvest (0.57), sample before delivery (0.54), assistance during the transition period (0.52), requiring security tags (0.48), percentage of organic grains contracted (0.47), and requiring truck affidavits (0.46) The first component (i.e., contract-oriented) seems to align mainly with the constructs represented by pragmatic organic buyers and values related to personal focus (e.g., control, achievement, and action). The second component features three significant loadings, related to perceptions that quality of grain is important to maintain relationships (0.80), lack of transparency in imported organic grains (0.41) and contracting pre-harvest (0.41). The second component (i.e., perception-oriented) seems to align with constructs represented by committed organic buyers and values related to social focus (e.g., flexibility, self-transcendence, and protection of industry standards). Lastly, the third component features three significant loadings, related to relying on farmer association to build relationships (0.68), receiving farmers’ input when drafting contracts (0.63), and flexibility in delivery and payment being important to build relationships (0.45). The third component (relationship-oriented) seems to align with values expected in buyers driven by social values that are philosophically rooted in the organic movement.

5. Conclusions

Domestic production of organic grains continues to fall short of meeting demand [,]. Even with increased profit potential through organic price premiums, many producers are still hesitant to enter the organic market. One of the major barriers to entry in the organic grain market for producers is the inability to identify an appropriate buyer, as well as an understanding of buyer perceptions, assistance offered, contracting strategy, and business functionality. While classifications of organic producers [,,] and factors motivating organic grain production [] are available and have helped researchers and policymakers develop incentives, no such classification exists for organic grain buyers. Development of a classification of organic grain buyers would allow producers insight into the perspectives and requirements that the buyer holds. Additionally, this classification of buyers would allow buyers themselves to assess shortcomings relative to competitors. In an attempt to disentangle the organic grain industry, this work suggests classifications of organic grain buyers, based on their (1) commitment to the organic industry and (2) priorities when building and developing relationships with farmers. Furthermore, this work compares relevant business demographics, buyer perceptions of the organic grain industry, relationship factors, and characteristics of purchasing agreements among buyer categories.

The major contribution of this article is the empirical evidence of the differences in values and priorities among committed organic vs. pragmatic organic buyers. It was hypothesized that committed organic buyers would be more focused on forging relationships with grain suppliers. Thus, committed organic buyers would offer more financial, marketing, agronomic and/or transitional assistance to grain suppliers than pragmatic organic buyers. We found committed organic buyers in our sample provided more contracting support than pragmatic organic buyers. For example, committed organic buyers had longer contracts for transitioning grains, and most contracts were drafted with farmer input. We also found that committed organic buyers had a higher percentage of contracts including an “act of God” clause, suggesting their willingness to invest in long-term relationships with growers. Our results suggest that committed organic buyers are smaller in both labor and gross sales, which may be driving committed organic buyers to provide tailored assistance to their current grain suppliers when compared to larger pragmatic organic operations.

Our findings suggest some factors in terms of growth and development of the organic grain industry. For instance, the results suggest that there is evidence of bifurcation in the organic grain market. The size of these pragmatic organic buyers, coupled with the fact that they purchase multiple classes of grains (organic, transitioning, non-GMO, and conventional), suggests that there is bifurcation in the industry, with larger operations being more diversified.

Analysis of the results from the perspective of PV theory demonstrates that different values are likely to guide attitudes and consequent behavior for different segments of organic grain buyers. Committed organic buyers seem to be guided mainly by values related to social focus, such as self-transcendence (universalism) and some aspects of environmental conservation. Pragmatic organic buyers seem to be guided, mainly, by values related to personal focus and self-enhancement, such as power through control of material and social resources []. Understanding the specific characteristics of the negotiation and contractual agreements that shape relationships with buyers will allow building lasting relationships that will benefit both producers and buyers.

This study presents information relevant to organic grain suppliers in the Midwest. Results from the principal component analysis suggest that one group of buyers prioritize contract characteristics when establishing relationships with farmers while another group ranks flexibility and relationships with buyers more important. Results from the principal component analysis suggest that not all committed organic buyers prioritize the same relationship factors. It seems that a group of buyers would prioritize the characteristics of contracts more than the development of relationships. Consistent with Torres, et al. [], attitudes and perceptions concerning organic agriculture and certification seem to rank high for buyers and farmers of organic grains. Our findings have important implications for organic farmers finding buyers for their grains. It seems that farmers need to consider that some buyers favor more the characteristics of the contracts, while others may prioritize the philosophy and attitudes implicit in the organic industry. Alternatively, policymakers aiming to support the success of the organic grain industry should consider the values and perceptions of farmers and buyers before designing incentives. It seems that matching farmers and buyers driven by similar social and personal values is likely to increase the success of purchasing relationships and the industry.

This study provides a foundation for future work to explore relationships among organic grain buyers and farmers. Our findings shed light on business demographics, buyer perceptions of the organic grain market, relationship factors, and characteristics of purchasing agreements commonly used among buyers in the current landscape of the organic grain industry. Our findings can help producers to understand buyer perceptions and requirements and buyers to analyze their operations compared to their competitors. Information in this work will allow beginning and current grain growers to determine communication methods with buyers and how buyers maintain long-term relationships with their grain suppliers. Thus, information provided in this work will allow for the growth and further development of the organic grain market infrastructure by providing marketing information for organic grain growers.

6. Limitations and Future Research

One of the limitations of the study is the small sample size, which was driven by the size of the population. However, our acceptable response rate and the methodology (principal component analysis and means comparisons) allow us to provide useful information to policymakers, industry stakeholders, and researchers. Another limitation is the region we focused our study on, which was determined by the project funding. Additional research should target buyers of organic grains from a nationwide population and track a panel of buyers over time to identify causal linkages between buyers’ categories and purchasing behavior.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.T. and N.A.L.; methodology, A.P.T.; software, A.P.T.; validation, A.P.T., N.A.L., and L.H.B.V.B.; formal analysis, A.P.T.; investigation, A.P.T. and N.A.L.; resources, A.P.T.; data curation, A.P.T. and N.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.L.; writing—review and editing, A.P.T. and N.A.L.; visualization, A.P.T., N.A.L., and L.H.B.V.B.; supervision, A.P.T.; project administration, A.P.T.; funding acquisition, A.P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2017-38640-26916 through the North Central Region SARE program under project number LNC17-397. USDA is an equal opportunity employer and service provider. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank NCR-SARE for funding provided for data collection, analysis, and publication. The authors thank growers, buyers, and handlers in the organic grain industry, University Extension, and project’s advisory board for their willingness to answer questions and provide feedback. We also thank the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (Capes), under the Capes-PrInt Program, process no. 88887.364642/2019-00 for supporting with researcher salary. We thank the following individuals for supporting project funding and technical peer reviews of survey questionnaire and buyer networks: Michael O’Donnell, Dr. Tamara Benjamin, Dr. Analena Bruce, and Dr. James Farmer.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Organic Trade Association. U.S. Organic State of the Industry. Organic Trade Association. 2016. Available online: https://ota.com/resources/market-analysis (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Oberholtzer, L.; Dimitri, C.; Jaenicke, E.C. International trade of organic food: Evidence of US imports. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2013, 28, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organic Trade Association. US Organic Grain—How to Keep it Growing. Organic Trade Association. 2019. Available online: https://ota.com/resources/market-analysis (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Organic Trade Association. U.S. Organic Sector Sees Steady Growth of 6.4 Percent in 2017. Organic Trade Association. 2017. Available online: https://ota.com/news/press-releases/20236 (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- L’Hoir, C.; Goddard, E.W.; Ng, D.W.; Lerohl, M.L. Preferences about Marketing Organic Grain in Alberta; 2002; Project report: 02-05; Department of Rural Economy. Faculty of Agriculture & Forestry and Home Economics. University of Alberta: Edmonton, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, N.; Torres, A.; O’Donnell, M.; Benjamin, T.; Bruce, A.; Farmer, J. Is organic right for my grain operation? In Purdue Extension; Organic Grain Production: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mercaris. Reports; Mercaris: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mercaris. 2017/2018 Organic and Non-GMO Soybean Market Guide; Mercaris: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mercaris. 2014/2016 Organic and Non-GMO Soybean Market Guide; Mercaris: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Varian, H.R. Intermediate Microeconomics: A Modern Approach: Ninth International Student Edition; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cranfield, J.; Henson, S.; Holliday, J. The motives, benefits, and problems of conversion to organic production. Agric. Hum. Values 2010, 27, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constance, D.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Lyke-Ho-Gland, H. Conventionalization, bifurcation, and quality of life: Certified and non-certified organic farmers in Texas. South. Rural Sociol. 2008, 23, 208. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, H.H.; Kastens, T.L.; Ross, K.L. Risks perceived by organic grain farmers in the central USA. J. Sustain. Agric. 2007, 31, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA-NOP. Organic Production and Handling Standard. 2016. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Organic%20Production-Handling%20Standards.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Buck, D.; Getz, C.; Guthman, J. From farm to table: The organic vegetable commodity chain of Northern California. Sociol. Rural. 1997, 37, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clunies-Ross, T.; Cox, G. Challenging the Productivist Paradigm: Organic Farming and the Politics of Agricultural Change; Agris FAO: Bath, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Darnhofer, I.; Schneeberger, W.; Freyer, B. Converting or not converting to organic farming in Austria: Farmer types and their rationale. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthman, J. Regulating meaning, appropriating nature: The codification of California organic agriculture. Antipode 1998, 30, 135–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthman, J. The trouble with ‘organic lite’in California: A rejoinder to the ‘conventionalisation’debate. Sociol. Rural. 2004, 44, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. The refined theory of basic values. In Values and Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour, R. Tipsheet: Crop rotation in organic farming systems. 2015. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/Crop%20Rotation%20in%20Organic%20Farming%20Systems_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Moncada, K.M.; Sheaffer, C.C. Risk Management Guide for Organic Producers; University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- USDA-NASS. Acreage June 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Newsroom/Executive_Briefings/2018/06-29-2018.pdf (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- USDA-AMS. Organic Reports. 2018. Available online: https://www.ams.usda.gov/market-news/organic (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Strochlic, R.; Sierra, L. Conventional, Mixed and Deregistered Organic Farmers: Entry Barriers and Reasons for Exiting Organic Production in California Davis; California Institute for Rural Studies. Davis, CA, USA, 2007. Available online: http://www.cirsinc.org/docs/organic_transitions.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Khaledi, M.; Weseen, S.; Sawyer, E.; Ferguson, S.; Gray, R. Factors influencing partial and complete adoption of organic farming practices in Saskatchewan, Canada. Can. J. Agric. Econ. /Rev. Can. D’agroeconomie 2010, 58, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, T.P.; Marshall, M.I. Identifying Drivers of Organic Decertification: An Analysis of Fruit and Vegetable Farmers. HortScience. [CrossRef]

- Born, H.; Sullivan, P. Marketing organic grains. National Sustainable Agricultural Information Service. 2005. Available online: https://attra.ncat.org/product/marketing-organic-grains/ (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Tovey, H. Food, environmentalism and rural sociology: On the organic farming movement in Ireland. Sociol. Rural. 1997, 37, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, T.L.; Shane, R.C.; Feuz, D.M. Lessons learned from the Upper Midwest organic marketing project. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2000, 15, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberger, J.R. Conventionalization, civic engagement, and the sustainability of organic agriculture. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clunies-Ross, T. Organic food: Swimming against the tide? In Political, Social, and Economic Perspectives on the International Food System; Marsden, T., Little, J., Eds.; Avebury: Aldershot, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, A.; Titterington, A.J.; Cochrane, C. Who buys organic food? Br. Food J. 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.; Dismukes, R.; Chambers, W.; Greene, C.; Kremen, A. Risk and risk management in organic agriculture: Views of organic farmers. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2004, 19, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, Y.S.; Arsil, P.; Brindal, M.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Radam, A.; Hadi, A.H.I.A.; Rajendran, N.; Lim, C.D. A means-end chain approach to explaining the adoption of good agricultural practices certification schemes: The case of Malaysian vegetable farmers. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2015, 28, 977–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Deal, D. Organic and local food consumer behaviour: Alphabet theory. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellows, A.C.; Onyango, B.; Diamond, A.; Hallman, W.K. Understanding consumer interest in organics: Production values vs. purchasing behavior. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2008, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Non-GMO Sourcebook. Suppliers of Non-GMO Products—United States. Available online: https://www.nongmoproject.org/ (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- USDA-AMS. Organic Integrity Database. 2017. Available online: https://organic.ams.usda.gov/integrity/ (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Dillman, D.A.; Smyth, J.D.; Christian, L.M. Internet, Phone, Mail, and Mixed-Mode Surveys: The Tailored Design Method; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A.; Phelps, G.; Tortora, R.; Swift, K.; Kohrell, J.; Berck, J.; Messer, B.L. Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the Internet. Soc. Sci. Res. 2009, 38, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooley, T.; Wellens, J.; Marriott, J. What is Online Research?: Using the Internet for Social Science Research; A&C Black: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Teng, L.; Liao, Y. Counterfeit luxuries: Does moral reasoning strategy influence consumers’ pursuit of counterfeits? J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Kane, R.L.; Shippee, T.; Lewis, T.M. Identifying consistent and coherent dimensions of nursing home quality: Exploratory factor analysis of quality indicators. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2016, 64, e259–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Winter, J.D.; Dodou, D.; Wieringa, P.A. Exploratory factor analysis with small sample sizes. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2009, 44, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, J.P. Factortest: Stata Module to Perform Tests for Appropriateness of Factor Analysis. 2006. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s436001.htm (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Farrell, M.; Mainville, D.Y. Organic Feed Grain Markets: An Analysis of Structure, Organization, and Potential for Virginia Producers. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2007, 38, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitri, C.; Greene, C.R. Recent Growth Patterns in the US Organic Foods Market. 2002. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=42456 (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Oberholtzer, L.; Dimitri, C.; Greene, C. Price Premiums Hold on as US Organic Produce Market Expands; US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service Washington (DC): Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Constance, D.; Choi, J.Y. Overcoming the barriers to organic adoption in the United States: A look at pragmatic conventional producers in Texas. Sustainability 2010, 2, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, J.R.; Epstein, G.; Watkins, S.L.; Mincey, S.K. Organic farming in West Virginia: A behavioral approach. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2014, 4, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.P.; Marshall, M.I.; Alexander, C.E.; Delgado, M.S. Are local market relationships undermining organic fruit and vegetable certification? A bivariate probit analysis. Agric. Econ. 2016, 48, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).