Abstract

Healthy development can be viewed as an important dimension of the general wellbeing index and can be based upon lifelong sustainable satisfaction. Young individuals can represent an important component for society and its development. The literature shows that increased levels of global life satisfaction (LS) can be associated with minimal levels of problematic behaviors and elevated levels of pro-social behaviors. However, low levels of LS can be associated with high levels of perceived loneliness (PL), which, in turn, can be associated with antisocial behavior (AS). In light of this, the current investigation aims to study the mediating effect of PL and the link between LS and AS. This study is a preliminary investigation referring to aggressive behaviors and cognition in relation to subjective wellbeing. The sample consisted of 81 young individuals (M = 27.57, Standard Deviation = 9.25) from Aurel Vlaicu University of Arad, Romania. AS was evaluated with the How I Think Questionnaire (HIT), PL was measured with a single item inquiry and LS was evaluated with the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS). The results display that there is a powerful association between LS and AS, between LS and PL and between PL and AS. After the inclusion of the mediator (PL) to the model, the influence of the independent variable (LS) increased and the effect of LS on AS significantly decreased. In light of this, the relationship between LS and AS can be explained by the mediating role of the PL variable. The results indicate the importance of perceived loneliness in regard to one’s life satisfaction and antisocial behaviors. In light of this, interventions that focus on the social aspect could prove useful for the improvement of sustainable life satisfaction, therefore decreasing the chance of the emergence of AS.

1. Introduction

Optimal aging [1] can be recognized as a key component of the general wellbeing index and can be represented by a lifelong sustainable overall personal and professional satisfaction, a journey that starts in youth and dynamically evolves as the individual develops.

The least described and the least understood approaches of addressing sustainability and sustainable development can be through social sustainability. In public discourse, social sustainability has earned far less coverage than economic and environmental sustainability. Social Sustainability is a mechanism or structure that encourages wellbeing within the members of an organization, while also promoting future generations’ ability to maintain a healthy community [2].

Young individuals can represent an important component of society as a whole and its development [3,4,5]. Therefore, the improvement of life satisfaction or wellbeing among young individuals can serve as an important factor in their contribution to society and a healthy self-development [6,7]. There is powerful information and evidence in the literature that an increased level of life satisfaction (LS) can be associated with positive individual (i.e., educational and professional success), psychological, behavioral and social results [8,9,10]. For example, individuals with high levels of LS (or subjective wellbeing) can have a high levels of job satisfaction and performance and can experience lower levels of negative psychological outcomes (i.e., anxiety or depression) [11,12].

Life satisfaction is represented by the way in which individuals express their subjective perspectives and perceptions about their own life [13]. In other words, it can be represented by a series of cognitive judgmental actions in regard to one’s life in general [14]. Some authors refer to life satisfaction as a subjective form of wellbeing [15]. Subjective wellbeing is represented by the assessments of the conditions of life at an individual or personal level and can include both an affective/emotional (the frequency of experienced pleasant or unpleasant emotions about life) and a cognitive (judgment of overall life satisfaction in multiple domains, such as: education, career or workplace, health situation, social relationships, etc.) component [16,17]. Possible predictors of life satisfaction can be represented by the access to different forms of material and intellectual resources (i.e., income, nutrition, material comfort, education, health services and access to knowledge), the formation of social connections (i.e., positive family relationships, social position, social prestige, social influence and social bonds) and the existence of different individual skills (i.e., intellectual, physical and social abilities) [8,9,10,18].

In terms of problem behaviors, studies from the literature demonstrated that increased levels of life satisfaction were related to decreased levels of problematic behaviors and high levels of pro-social behaviors [10,19,20,21]. In the literature, problem behaviors are usually associated with antisocial behaviors [22,23,24]. It is stated that the emergence of antisocial behaviors can be associated with a disadvantaged socio-economic background, a lack of education or a very low education level, dysfunctional families and deviant peers [25,26,27]. All the mentioned factors can be associated with low life satisfaction [10,18,28,29], which, in turn, can lead to the development of antisocial behaviors [10,30]. In this paper, we will focus on antisocial behaviors from the viewpoint of self-serving cognitive distortions [31].

Self-serving cognitive distortions are represented by prejudicial cognitive models that give the individual a very good impression of himself/herself and isolate him/her from guilt or a negative self-concept [32]. They are classified in four categories, such as: Self-Centered (egocentric cognitions), Blaming Others (attributing one’s fault to external sources for one’s negative behaviors), Minimizing/Mislabeling (perceiving antisocial behavior as an acceptable means and viewing other as having no value) and Assuming the Worst (perceiving others or social situations as hostile and believing that one’s negative behavior is beyond improvement) [33]. The association of self-serving cognitive distortions with antisocial behaviors can be explained by a series of characteristics extracted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) [34], such as Opposition Defiance (no respect for rules, laws and authority), Lying, Stealing and Physical Aggression [31,33]. In DSM-V [35], antisocial characteristics can be identified as impulse control, disruptive and conduct disorders, which can determine whether individuals will act with anger or aggression toward other individuals or their property.

Antisocial behaviors can be associated with a series of factors [36,37,38,39,40]. One of the studied factors in this article, in relation to antisocial behavior, is the perception of loneliness. Studies from the literature [41,42] postulate that perceptions of loneliness can have some negative psychological outcomes (i.e., depression, anxiety), but other studies show that perceptions of loneliness can also be associated with the presence of antisocial tendencies [43,44,45], especially in younger individuals [46,47].

Loneliness is represented as a perceived emotional discomfort that can be associated with the perception of isolation or unfulfilling social connections [48]. There is evidence in the literature that feelings of loneliness are prevalent in young individuals [49] and can increase in level with age [50], if untreated. It is also stated that Eastern European countries have the most elevated proportions of lonely individuals [50].

It was found that some of the main causes for loneliness can be represented by inadequacies at the individual level, developmental deficits, unsatisfying intimate connections, separations and social marginality [51].

Social bonds are very important factors for maintaining a healthy life satisfaction [18]. Studies have shown that elevated levels of loneliness are associated with decreased levels of LS [52,53,54] and it has already been mentioned that high levels of LS are linked with minimal levels of problematic behaviors and elevated levels of pro-social behaviors [10,19,20,21]. Therefore, as a preliminary investigation, in this article we want to study the mediating impact of perceived loneliness (PL) on the link between life satisfaction and general antisocial behavior.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Objective and Hypothesis

The scope of Tudor and Bratosin’s study on the social dimension of sustainability related to culturalisation, on the one hand, comprehended culture as an ideological, essential, basic factor in social processes and relationships concerning sustainability and, on the other hand, considered the mediatization of culture [55]. A culture of mediatization can be in constant development, with its main assets being mediated by current media technology. In this respect, as research conclusions have stated that mediatization is the result and consequence of relationships, interrelationships, connections, and interconnections between the use of communication methods by society and tools enhanced by digital technology and, at the same time, it refers to a new social context that concentrates deeply on those relationships, interrelationships, and associations that build a contemporary society [55].

The objective of the present investigation is to study the mediating effect of perceived loneliness (PL) on the link between global life satisfaction (LS) and general antisocial behavior (AS). This study is part of a preliminary investigation with reference to aggressive behaviors and cognition in relation to subjective wellbeing.

The hypothesis is that the link between LS and AS is mediated by PL, which is seen as a potential enhancer of antisocial behavior.

2.2. Participants

A total of 81 young individuals from Aurel Vlaicu University of Arad Romania voluntarily participated in this investigation, established via informal consent. The participants of this study were comprised of 55 females (67.9%) and26 males (32.1%), N = 81, with an average mean (M) age = 27.57 and a standard deviation (SD) of 9.25. All the participants were enrolled in the University or at least finished an academic cycle (Bachelor Degree, Master Degree or Postgraduate Degree). This research has used convenience sampling. The participants were consecutively selected according to the order of appearance when completing the online questionnaire shared on social media platforms, following the convenient accessibility principle. The time frame used was December 2019–February 2020. The gender distribution reflects the large female population of students in the Educational Sciences, Psychology and Social Sciences department of the “Aurel Vlaicu” University of Arad. Being an online shared study, the low number of participants reflects students’ abilities to access online platforms and their willingness to participate.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

In order to evaluate LS, the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) [15] was used, which aims to assess global cognitive judgments of one’s fulfillment with life. This instrument is made of five items, with a seven-point response scale, which can range from strongly agree (7) to strongly disagree (1) [15]. SWLS [15] was linguistically validated in a previous study for Romanian usage [56] and, in the present study, it showed a high internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.80.

2.3.2. The How I Think Questionnaire (HIT)

In order to measure AS, the How I Think Questionnaire (HIT) [33] was applied, which was created to evaluate the levels of self-serving cognitive distortions (i.e., Assuming the Worst, Blaming Others, Self-Centered and Minimizing/Mislabeling) and of the four classifications of antisocial behavior (i.e., Stealing, Physical Aggression, Lying and Opposition Defiance.).

HIT [33] is represented by 54 questions, with a six-point Likert-type answer scale, which can range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6). Out of the 54 questions, 39 are constructed to assess the four categories of “self-serving” cognitive distortions and the four types of antisocial behavior, eight inquiries measure the level of anomalous responding (in order to determine the honesty of the given answers) and seven questions are constructed as positive filters in order to camouflage the 39 items [33]. The sum of Physical Aggression and Opposition Defiance compose the Overt Scale (antisocial manifestations that involve the victim in a direct way) and the sum of the Stealing and the Lying scales compose the Covert Scale (antisocial actions that involve the victim in an indirect way) [33]. The questionnaire can have a general score and it is composed of 12 scales [33].

HIT was validated for Romanian usage (linguistic validation) in a previous study [57] and the present study will use the total score of HIT in order to assess the level of general antisocial behavior (AS). In the present study, HIT showed a high internal consistency, having a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient that ranges from 0.68 to 0.84, with a global coefficient of 0.91.

2.3.3. Explorative Affirmations

In this study, based on studies and works from the literature [35,44,58,59,60,61] we developed a series of explorative affirmations that aim to identify the levels of violent/aggressive content (video, audio or text) preferences (e.g., I like to watch aggressive or violent content; measured by four inquiries); perceived positive childhood experiences (e.g., My childhood was a happy one; measured by three inquiries); control/domination of others (e.g., I like to control people around me; measured by three inquiries); perceived superiority (e.g., I consider myself more intelligent than the others; measured by three inquiries); schadenfreude (e.g., I feel good when something bad happens to other people; measured by one inquiry); openness (e.g., I easily relate to other people; measured by one inquiry); perceived loneliness (PL; e.g., I feel alone; measured by one inquiry); and self-isolation (e.g., I prefer to spend more time alone; measured by one inquiry). The 17 affirmations were assessed using a six-point Likert-type response scale, ranging from it does not characterize me at all (0) to it characterizes me to a great extent (5).

The explorative affirmations were applied for the first time in this study and the level of perceived loneliness (PL) will be used for this investigation. PL was measured by a single-item research question. It is a simple and explorative inquiry which identifies the level of perceived general loneliness.

2.4. Study Design and Procedure

The current investigation has a non-experimental mediation analysis design. The independent variable (IV) is the level of global life satisfaction (LS) and the dependent variable (DV) is the level of general antisocial behavior (AS). The mediator variable (MV) is the level of perceived loneliness (PL). The package of instruments (SWLS, HIT and the General Affirmations) was applied to the participants in a digital setting (via Google Forms). To verify if the participants were paying attention to the package of instruments we used the scores from the Positive Filters (PF) scale of the HIT questionnaire [33]. Those questions are different from the general questions of HIT, and if the scores for PF are higher than the general scores from HIT, then we can assume that the participants were paying attention to the inquiries. The score for PF was 5.46 (SD = 0.48), which can reflect the fact that the participants were paying attention to the questions, because the scores for HIT were significantly lower 1.91 (SD = 0.57) (Table 1). The participation to this investigation was based on informed consent that consisted of an agreement to attend the study and assurances about the confidentiality of the data.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviation for each variable (global life satisfaction (LS), perceived loneliness (PL) and antisocial behavior (AS)) according to gender.

Before calculating the mediation effect, a gender comparison was realized in order to determine if there were any differences regarding the studied variables (LS, AS, PL) between genders. For this analysis, the Wilcoxon W test was used because the gender distribution was unbalanced.

Later, we realized a correlational multi-group analysis by gender, regarding the studied variables, to see if the correlations differed according to gender (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2.

Pearson correlation coefficients between LS, AS and PL for the female participants (N = 55).

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients between LS, AS and PL for the male participants (N = 26).

In order to calculate the mediation effect, a series of steps were followed [62,63,64,65]:

(1) Verifying if all the studied variables (LS, AS and PL) can be associated with each other in a statistically significant way (p < 0.05) way (Table 4);

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients between LS, AS and PL for the whole group (N = 81).

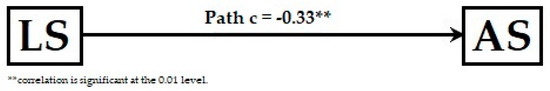

(2) Determining path c by regressing the DV (AS) with the IV (LS) for confirmation that the IV is a significant predictor of the DV (Table 5; Figure 1);

Table 5.

Coefficients for the mediation effect.

Figure 1.

Path c between the variables: global life satisfaction (LS) and general antisocial behavior (AS).

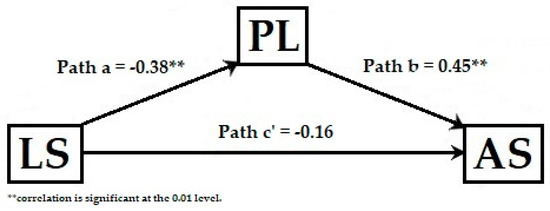

(3) Determining path a by regressing the MV (PL) with the IV (LS) to affirm that the IV is a significant predictor of MV (Table 5; Figure 2);

Figure 2.

Paths a, b and c′ between the variables LS, perceived loneliness (PL) and AS.

(4) Determining the paths b and c′ by regressing the DV with both the MV and the IV to affirm that the MV is a significant predictor of the DV (path b). To have a mediation effect, path b must be statistically significant, while path c′ must be reduced in significance (partial mediation) or even be reduced to insignificance (complete mediation) (Table 5; Figure 2);

(5) Determining the statistical importance of the indirect outcome by utilizing bootstrapping procedures and the Sobel test. This step can be achieved by using PROCESS macro version 2.16 [66] on SPSS Statistics version 20 (the version used in this study), or any version above.

Regarding the Wilcoxon W test, no significant differences were registered between the two genders regarding the studied variables (LS, Z = −0.07, p > 0.05; PL, Z = −0.84, p > 0.05; AS, Z = −0.87, p > 0.05).

3. Results

In addition to the investigation of the specified variables, the score for the Anomalous Responding scale was computed as well, to determine the honesty of the answers offered to the package of instruments (SWLS, HIT and the General Affirmations). If the calculated value of the Anomalous Responding scale was greater than 4.00, then the evaluation would be considered doubtful in terms of the honesty of the given replies; if the calculated value was beyond 4.25, then the evaluation could not be considered valid [33]. The calculated score for the Anomalous Responding scale in the current sample (N = 81) was M = 3.81 (SD = 1.12), which illustrates that the majority of the respondents gave honest answers to the inquiries about the instruments. There were individuals whose score exceeded 4.00 (N = 10) and 4.25 (N = 28), but they were not removed from the investigation because in the natural world there are persons who are dishonest and, in this format, the sample can be more appropriate. Dishonesty is prevalent in daily human existence [67].

As Figure 2 depicts, the standardized regression values between the level of LS and the level of PL was statistically significant, as was the standardized regression value between PL and the level of AS. The standardized indirect effect was (−0.38) × (0.45) = −0.17. These results support the mediation hypothesis. After the inclusion of the mediator (full mediation), the level of LS was no longer a significant predictor of the level of AS. Approximately 28% of the variance in the AS variable was accounted for by the predictors, i.e., LS and PL (r2 = 0.28). Unstandardized indirect outcomes were calculated for every 5000 bootstrapped samples, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated by establishing the indirect outcomes. The bootstrapped unstandardized indirect outcome was B = −0.10, standard error (SE) = 0.04 and the 95% CI ranged from −0.21 and −0.04. The Sobel test score was −0.10, SE = 0.04, p < 0.01. These results show that the indirect effect was statistically significant.

4. Discussion

As a central conclusion, we would like to further emphasize how culture and mediatization of social sustainability transform daily behavior, in light of the study’s conclusions. Nowadays, both digital and real existence seem to be bound to the terms of the democratization of information. This brings clear advantages, in terms of faster access to plenty of information, meaning that individuals are better informed and well-equipped to think reasonably, make effective decisions, and solve diverse problems [68], and even seek medical help [69]. With all these technological advances, the problem of individual solitude and loneliness has not been adequately addressed so far.

The current study investigated the mediating outcome of PL to the link between LS and AS in young individuals. The results show that decreased levels of LS and increased levels of PL are important risk factors for the occurrence of AS, but elevated levels of LS and minimal levels of PL can discourage the emergence of AS. Furthermore, the link between LS and AS was completely mediated by PL, meaning that this relationship can be explained by the role of the mediator.

The multi-group correlational analysis showed that significant correlations between the three variables (LS; PL; AS) were registered only for the male gender. For the female gender, the most significant variable was PL in its relationship with AS, meaning that there was a significant association between AS and PL. There were no significant differences between the two genders in relation to the Wilcoxon W test and the insignificant correlations between the level of LS and the levels of AS and PL for the female gender could be due to that fact that they obtained slightly higher scores for the level of LS (with lower SD) and lower scores for the level of PL and AS (with a lower SD) than the male participants. On the other hand, the insignificant correlations for the female gender may be due to the fact that the value of subjective wellbeing may differ for each gender (females might value the wellbeing of others more than males and value materialism and competition less than males; males might value sports, sexual activity, being liked, and having a quality social life more than females and females might value helping others, being close to family, and being loved more than men) [70]; this might also be due to the fact that females tend to internalize behaviors, whereas males tend to externalize behaviors [71,72,73].

As for the group as a whole, the findings are consistent with the literature [10,19,20,21], meaning that the level of LS can contribute to the emergence of AS. Therefore, due to the lack of an appropriate education, professional path, social relationships, healthcare and financial situation (factors that can affect the perception of global life satisfaction), one can develop antisocial tendencies as a form of psychological, social and behavioral adaptation [25,58,74].

Furthermore, the results indicate that the level of global life satisfaction is negatively correlated with the level of perceived loneliness. The human species are designed to be social creatures [75]. Humans desires touch, social interactions and a feeling of connection and belonging [76]. The feelings of belonging and social connections can represent important factors for life satisfaction [54,75]. Low levels of perceived loneliness can affect one’s emotional state in a negative way (i.e., depression) [41], but it can also affect one’s behavioral state (i.e., problematic or antisocial behavior) [43,44,45], especially in younger individuals [46,47].

5. Conclusions

A suppressor model in the mediation framework leads to an inconsistent mediation model, where the mediated and the direct effect have opposite signs. Suppression focuses on the adjustment of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables, but in the unusual case where the size of the effect actually increases when the suppressor variable is added [77], in a two-factor model, a suppressor variable leads to a previously undetected type of suppression (reciprocal suppression), which occurs when predictors with positive zero order validities are negatively correlated with one another [78], such as in the results from our current research.

In light of this, the preliminary results of the study can suggest that persons who possess increased levels of life satisfaction are less likely to feel alone, therefore minimizing the chance for the emergence of antisocial behavior. However, if individuals perceive their global life satisfaction as being low, they can feel alone more often and can be inclined to adopt antisocial behaviors. Socialization is very important for any individual’s development [79,80,81] and these results underline the necessity to take into consideration the social aspect (the need for human connection) in relation to life satisfaction and the development of antisocial behavior (especially for individuals who already committed crimes). A good example comes from a previous study [40], where individuals with increased levels of social support (a significant component that give the individual a sense of belonging) have had higher levels of education and decreased levels of antisocial behaviors and criminal history. In light of this, intervention and prevention programs can be developed that focus more on the social aspects (i.e., human connections and meaningful relationships) when it comes to dealing with low life satisfaction levels and high levels of antisocial tendencies.

Thus, these results underline the suppressive effects of increased levels of perceived loneliness on the relationship between global life satisfaction and general antisocial behavior in young individuals and can represent a need for psychological intervention in lowering the negative incident rates in accordance with social sustainability principles.

As a final remark, these findings align with the paradigm that, while aggressive manifestations of seeking control over others still govern human interactions, individuals have an equal and powerful need for acceptance, social approval, and a good sense of connectedness to social and personal supportive environments. These two antagonistic forces collide and emerge on a personal level and on a social level, which can represent human needs that eventually orient towards seeking mental and physical life satisfaction or wellbeing [82,83,84].

The practical implications of these preliminary results can be significant for future investigations and underline the necessity to take into consideration the loneliness aspect when dealing with young individuals’ antisocial behaviors and life satisfaction. In order for an individual to appreciate his own life and to reduce the development on antisocial behaviors, one must feel that he belongs to and is accepted within a given society. Different educational programs can be developed in schools and universities, which can focus on reducing the levels of loneliness and increasing the levels of life satisfaction. Interventions that focus on the social aspect could prove useful for the improvement of a sustainable life satisfaction, thus decreasing the chance of the emergence of antisocial behaviors (AS).

In the era of the mediatization of everything [85,86,87], the loneliness paradigm seems paradoxical. Even if mediatization as a socially sustainable phenomenon is supposed to bring people closer than ever, it may actually trigger a higher loading of perceived loneliness in youth. Taken together, the cumulative positive effect on society in terms of individuals in this new era of openness might bring a live issues related to individuals’ perceived exclusion from digital society, a new sort of social isolation, which brings with it a prevalent sense of perceived loneliness and, in turn, raises individuals’ risk of antisocial behavior. This psychological mutation, in the broad sense of affected belonging, is impregnated in young people’s mentalities, as scores on the HIT scale reflect, indicating a clear psychological shift, an induced change in human interactions and social practices.

Limitations and Future Research

In terms of the limitations of this study, considering that this was an internet-based research sample, respondents have completed measurements at different locations, which may have influenced the findings because of the lack of control over environmental factors. In addition to this limitation, some participants were suspected of being dishonest as regards to the Anomalous Responding scale. An explanation for the presence of dishonesty can be the fact that the majority of the participants were students and it is stated in the literature that dishonesty is present in the academic sector [88,89] and more capable individuals tend to be more dishonest [90]. Other studies suggest that dishonesty is prevalent in our daily lives [67] and that dishonesty is part of Self-Concept Maintenance [91]. In regard to this limitation, further research is required to investigate the dishonesty component in regard to life satisfaction, loneliness and antisocial tendencies.

Another one of the limitations can be represented by the small number of participants (N = 81) and the unbalanced gender distribution, meaning that these results do not allow for an extension on certain categories of age, gender or educational category. Therefore, future studies on homogeneous groups could provide more useful information to construct a more relevant image of the investigated subjects in different population categories.

In future research, the bidirectionality of the relationships between the variables (LS, PL and AS) could be investigated, meaning that high levels of antisocial behavior can also be related to low life satisfaction levels, which may lead to loneliness. By taking into account the bidirectionality of the studied variables, future interventions might prove to be more successful in dealing with low life satisfaction levels and high levels of antisocial behavior.

Being a preliminary study, future investigations will be developed on larger samples, while taking into account more variables that can be associated with life satisfaction and antisocial behaviors, thus creating a better image for maintaining healthy life satisfaction and development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.D. and D.R.; methodology, E.D. and D.R.; software, E.D. and D.R.; validation, E.D. and D.R.; formal analysis, E.D.; investigation, E.D.; resources, D.R.; data curation, D.R. and E.D.; writing—original draft preparation, E.D.; writing—review and editing, D.R. and E.D.; visualization, E.D.; supervision, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kemperman, A.; van den Berg, P.; Weijs-Perrée, M.; Uijtdewillegen, K. Loneliness of Older Adults: Social Network and the Living Environment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magee, L.; Scerri, A.; James, P. Measuring Social Sustainability. Commun. Cent. Approach Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2012, 7, 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruth, J.L.; Brooks-Gunn, J. Youth development programs: Risks, prevention and policy. J. Adolesc. Health 2003, 32, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, R.F.; Berglund, M.L.; Ryan, J.A.M.; Lonczak, H.S.; Hawkins, J.D. Positive Youth Development in the United States: Research Findings on Evaluations of Positive Youth Development Programs. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2004, 591, 98–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, A. Youth Studies: An Introduction, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rector, N.A.; Roger, D. Cognitive style and well-being: A prospective examination. Personal. Ind. Differ. 1996, 21, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E.S.; Suldo, S.M.; Gilman, R. Life satisfaction. In Children’s Needs III: Development, Prevention, and Intervention; Bear, G.G., Minke, K.M., Eds.; National Association of School Psychologists: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2006; pp. 357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, C.L.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. J. Happiness Stud. 2009, 10, 583–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.; Linley, P.A.; Maltby, J. Very happy youths: Benefits of very high life satisfaction among youths. Soc. Ind. Res. 2010, 98, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.; Linley, P.A. Life Satisfaction in Youth. In Increasing Psychological Well-Being in Clinical and Educational Settings; Fava, G., Ruini, C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 8, pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Haar, J.M.; Roche, M.A. Family supportive organization perceptions and employee outcomes: The mediating effects of life satisfaction. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 999–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Suñé, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P. Happiness Explained; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.; Johnson, D.M. Avowed happiness as an overall assessment of the quality of life. Soc. Ind. Res. 1978, 5, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, C.N.; Ruberton, P.M.; Lyubomirsky, S. Subjective Wellbeing, Psychology of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J.D., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; Volume 23, pp. 648–653. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R. The Study of Life-Satisfaction; Eötvös University Press: Budapest, Hungary, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamad, M.; Mohammad, M.; Mamat, I.; Mamat, M. Modelling Positive Development, Life Satisfaction and Problem Behaviour among Youths in Malaysia. World Appl. Sci. J. 2014, 32, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, R.C.F.; Shek, D.T.L. Positive Youth Development, Life Satisfaction and Problem Behaviour among Chinese Adolescents in Hong Kong: A Replication. Soc. Ind. Res. 2012, 105, 541–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P. Self–Efficacy Beliefs as Determinants of Prosocial Behavior Conducive to Life Satisfaction across Ages. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2005, 24, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botvin, G.J.; Griffin, K.W.; Nichols, T.D. Preventing Youth Violence and Delinquency through a Universal School-Based Prevention Approach. Prev. Sci. 2006, 7, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.A.M. Friends: The Role of Peer Influence across Adolescent Risk Behaviors. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahey, B.B.; Moffitt, T.E.; Caspi, A. Causes of Conduct Disorder and Juvenile Delinquency; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marica, M.A. Introducere în Problematica Delincvenţei Juvenile; Ovidius University Press: Constanța, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Millie, A. Anti-Social Behaviour; Open University Press: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, J.D. Juvenile Delinquency; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.: Maryland, MD, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, C.S. Family system characteristics, parental behaviors, and adolescent family life satisfaction. Fam. Relat. Interdiscip. J. Appl. Fam. Stud. 1994, 43, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jradi, H.; Abouabbas, O. Well-Being and Associated Factors among Women in the Gender-Segregated Country. Int. J. Environ. Rese. Public Health 2017, 14, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, J.M.; Piquero, A.R.; Valois, R.F.; Zullig, K.J. The Relationship Between Life Satisfaction, Risk-Taking Behaviors, and Youth Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2005, 20, 1495–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Hawkins, M.; Camelia, C.R. Specificity of cognitive distortions to antisocial behaviour. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2008, 18, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Landau, J.R.; Stinson, B.L.; Liau, A.K.; Gibbs, J.C. Cognitive distortion and problem behaviors in adolescents. Crim. Justice Behav. 2000, 27, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, A.Q.; Gibbs, J.C.; Potter, G.; Liau, A.K. How I Think (HIT) Questionnaire Manual; Research Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, E.; Costea, I.; Rusu, A.S. Emotional maturity, self-esteem and attachment styles: Preliminary comparative analysis between adolescents with and without delinquent status. Agora Psycho-Pragmat. 2016, 10, 46–61. [Google Scholar]

- Bălaş-Timar, D.; Ignat, S.; Demeter, E. The dynamic relationship between perceived parental support and online bullying. J. Plus Educ. 2017, 18, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Demeter, E.; Rusu, A.S. Perceived Dysfunctional Mother Behaviour and Anti-Social Behaviour in Adolescence: The Mediating Role of Substance and Alcohol Consumption. In Proceedings of the Filodiritto International 7th Edition Groups with Special Needs in Community Measures, Proceedings of the International Conference Multidisciplinary Perspectives in the Quasi-Coercive Treatment of Offenders, Timișoara, Romania, 13–14 September 2018; Tomita, M., Ed.; Filodiritto Editore: Bologna, Italy, 2018; pp. 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, E.; Rusu, A.S. The relationship between the criminal offence and self-serving cognitive distortions. J. Plus Educ. 2019, 23, 81–86. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, E.; Rusu, A.S. Assessed Social Support and Anti-Social Behaviors in Juvenile Delinquents: Preliminary Investigation. In The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS; Chis, V., Albulescu, I., Eds.; Future Academy: ClujNapoca, Romania, 2019; Volume LXIII, pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, T.; Danese, A.; Wertz, J.; Odgers, C.L.; Ambler, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: A behavioural genetic analysis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, S.R.; Parkhurst, J.T.; Hymel, S.; Williams, G.A. Peer rejection and loneliness in childhood. In Peer Rejection in Childhood; Asher, S.R., Coie, J.D., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 253–273. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell, C.L. Friendships, peer networks, and antisocial behavior. In Decade of Behavior. Children’s Peer Relations: From Development to Intervention; Kupersmidt, J.B., Dodge, K.A., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, W.H.J.; Palermo, G.B. Loneliness and Associated Violent Antisocial Behavior: Analysis of the Case Reports of Jeffrey Dahmer and Dennis Nilsen. Int. J. Off. Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2005, 49, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povedano, A.; Cava, M.-J.; Monreal, M.-C.; Varela, R.; Musitu, G. Victimization, loneliness, overt and relational violence at the school from a gender perspective. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2015, 15, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T.; Auslander, N. Adolescent Loneliness: An Exploratory Study of Social and Psychological Pre-Dispositions and Theory; Behavioral Research and Evaluation Corp.: Boulder, CO, USA, 1979; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Buelga, S.; Musitu, G.; Murgui, S.; Pons, J. Reputation, loneliness, satisfaction with life and aggressive behavior in adolescence. Span. J. Psychol. 2008, 11, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, A.; Rohrmann, S.; Vandeleur, C.L.; Schmid, M.; Barth, J.; Eichholzer, M. Loneliness is adversely associated with physical and mental health and lifestyle factors: Results from a Swiss national survey. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, U.; Tuncay, T. Correlates of loneliness among university students. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2008, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.M.; Victor, C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 1368–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokach, A.; Brock, H. The causes of loneliness. Psychol. J. Hum. Behav. 1996, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Schumaker, J.F.; Shea, J.D.; Monfries, M.M.; Groth-Marnat, G. Loneliness and life satisfaction in Japan and Australia. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 1993, 127, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, R.; Cook, O.; Yung, Y. Loneliness and life satisfaction among three cultural groups. Pers. Relatsh. 2001, 8, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.; Stokes, M.; Firth, L.; Hayashi, Y.; Cummins, R. Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness, and life satisfaction. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008, 45, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudor, M.A.; Bratosin, S. French Media Representations towards Sustainability: Education and Information through Mythical-Religious References. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.J.; Lambru, I.; Sandu, C.G.; Constantinescu, P.-M.; Butucescu, A.; Uscatescu, L. Romanian adaptation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Psychol. Educ. Res. (JPER) 2012, 20, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Demeter, E.; Balas-Timar, D.; Ionescu (Pădurean), A.; Rusu, A.S. Romanian translation and linguistic validation of the how I think questionnaire. In The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS; Chis, V., Albulescu, I., Eds.; Future Academy: ClujNapoca, Romania, 2018; Volume XLI, pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- Shoemaker, J.D. Theories of Delinquency: An Examination of Explanations of Delinquent Behavior, 6th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A.; Dorothea, R.; Ross, S.A. Imitation on Film-Mediated Aggressive Models. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1963, 66, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.; Jones, J.; Gombojav, N.; Linkenbach, J.; Sege, R. Positive Childhood Experiences and Adult Mental and Relational Health in a Statewide Sample. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, e193007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.H.; Powell, C.A.J.; Combs, D.J.Y.; Schurtz, D.R. Exploring the When and Why of Schadenfreude. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2009, 3, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research—Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in Experimental and Nonexperimental Studies: New Procedures and Recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Methodology in the Social Sciences. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, J. Reporting Mediation and Moderation. Available online: http://my.ilstu.edu/~jhkahn/medmod.html (accessed on 20 February 2020).

- Hayes, A.F. (2012–2018). The PROCESS Macro for SPSS and SAS. Available online: http://www.processmacro.org/ (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Mazar, N.; Ariely, D. Dishonesty in scientific research. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 3993–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Marques Vieira, R.; Tenreiro-Vieira, C. Educating for critical thinking in university: The criticality of critical thinking in education and everyday life. ESSACHESS J. Commun. Stud. 2018, 11, 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, S.; Bonneville, L.; Redpath, C. The Design Process of an mHealth Technology: The Communicative Constitution of Patient Engagement Through a Participatory Design Workshop. ESSACHESS J. Commun. Stud. 2019, 12, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Batz, C.; Tay, L. Gender Differences in Subjective Well-Being. In e-Handbook of Subjective Well-Being; Diener, E., Oishi, S., Tay, L., Eds.; NobaScholar: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2017; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, B.M.; Blonigen, D.M.; Kramer, M.D.; Krueger, R.F.; Patrick, C.J.; Iacono, W.G.; McGue, M. Gender differences and developmental change in externalizing disorders from late adolescence to early adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2007, 116, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leadbeater, B.J.; Kuperminc, G.P.; Blatt, S.J.; Hertzog, C. A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 35, 1268–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschi, T.; Morgen, K.; Bradley, C.; Smith Hatcher, S. Exploring Gender Differences on Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Among Maltreated Youth: Implications for Social Work Action. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2008, 25, 531–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, R. Building on the Foundation of General Strain Theory: Specifying the Types of Strain Most Likely to Lead to Crime and Delinquency. Res. Crime Delinq. 2001, 38, 319–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aristotle Jowett, B.; Davis, H.W.C. Politics; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Krull, J.L.; Lockwood, C.M. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prev. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Prev. Res. 2000, 1, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conger, A.J. A Revised Definition for Suppressor Variables: A Guide to Their Identification and Interpretation. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewoods Cliff, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Damon, W. Social and Personality Development: Infancy through Adolescence; W.W. Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, C.S.M.; Callaghan, B.L.; Kan, J.M.; Richardson, R. The lasting impact of early-life adversity on individuals and their descendants: Potential mechanisms and hope for intervention. Genes Brain Behav. 2016, 15, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P. Compassion as a social mentality: An evolutionary approach. In Compassion: Concepts, Research and Applications; Gilbert, P., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 31–68. [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez, D. Evolution, child raising, and compassionate morality. In Compassion: Concepts, Research and Applications; Gilbert, P., Ed.; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 173–186. [Google Scholar]

- Seppälä, E.M.; Simon-Thomas, E.; Brown, S.L.; Worline, M.C.; Cameron, C.D.; Doty, J.R. (Eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Compassion Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S. On the mediation of everything. J. Commun. 2009, 59, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.; Lunt, P. Mediatization: An emerging paradigm for media and communication research. In Mediatization of Communication: Handbooks of Communication Science; Lundby, K., Ed.; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 21, pp. 703–723. [Google Scholar]

- Bratosin, S. La médialisation du religieux dans la théorie du post néo-protestantisme. Soc. Compass 2016, 63, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, E.A.; Storch, J.B. Fraternities, sororities, and academic dishonesty. Coll. Stud. J. 2002, 36, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Nazir, M.S.; Aslam, M.S. Academic dishonesty and perceptions of Pakistani students. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2010, 24, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gino, F.; Ariely, D. The dark side of creativity: Original thinkers can be more dishonest. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, N.; Amir, O.; Ariely, D. The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept Maintenance. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).