Abstract

Recently, debates on authenticity in the West and China have attracted attention of critical heritage studies. This paper aims to better understand how Western Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD) influences local heritage practice in China. This paper employs observation, semi-structured interviews and textual analysis to examine how authenticity criteria in Western AHD has shaped perceptions on the spatial consequences of what is “authentic” by different agents in regards to the cultural heritage of the Shaolin Temple. It is argued that the implementation of authenticity criteria found in Western AHD influences Shaolin heritage practice both in hegemonic and negotiated ways, in which a Chinese AHD is formed through the creation of a Western AHD with Chinese characteristics. The understandings on authenticity criteria derived from Western AHD by Chinese heritage experts dominates Shaolin heritage practice, whilst the perceptions on “authentic” Shaolin Temple cultural heritage attached closely to their emotions and experiences by local residents are neglected and excluded. The religiously based authenticity claims of the Shaolin monks which competes with those of the heritage experts and local residents are also considered. Furthermore, the managerial structure was changed in 2010 from a government-directed institution to a joint-venture partnership. The impacts of these managerial changes are also considered. The final outcome of these competing heritage claims was that local residents were relocated far from their original community. Without the residential community in situ, and in conjunction with the further commercialization of local culture, the Shaolin Temple heritage site takes on the features of a pseudo-classic theme park.

1. Introduction

Recently, there has been increasing attention in critical heritage studies given to issues of reconstruction, authenticity, and management [1,2,3,4]. Among these, the notion of Authorized Heritage Discourse (AHD) developed by Laurajane Smith has become a powerful tool to criticize the domination of Western ideas of heritage, and in particular how heritage experts, government agencies and others actors incorporated within the AHD, think, talk, and deal with heritage [5]. Some international heritage conventions and charters, such as the Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage (CCPWCNH) adopted by UNESCO in 1972, not only provide the standards to understand and define the significance of heritage, they also work as authorizing institutions to guide national policies on how to conserve, manage and use heritage. However, due to different historical and cultural backgrounds, non-European contexts may have very different understandings regarding heritage conservation and governance [6]. Hence the development of a non-Western AHD will also involve the playing out of the power relations imbedded in specific national heritage contexts [7].

Two salient examples can be found in the definition and practices of cultural heritage ‘authenticity’ and ‘reconstruction’, a topic that has been a hot debate in heritage policy and practice in recent years. Authenticity was first applied by heritage experts and curators to test whether or not the objects on display in museums were genuine [8] (p. 93). The CCPWCNH, together with the Operational Guidelines for Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (OGIWHC), considers authenticity as one of the key criteria for World Heritage inscription. In due course authenticity became a fundamental feature of Western heritage discourse incorporating both movable and immovable objects. For example, the Venice Charter (1964) recommends that restoration should be made in accordance with the “original material and authentic documents” [9]. Here ‘authenticity’ refers to an objective standard to differentiate between what is ’genuine’ and what is ‘fake’. Implementing authenticity criteria for built heritage meets some of its biggest challenges when confronted with practices of reconstruction. By ‘reconstruction’, in contrast to ‘restoration’, we mean the rebuilding of lost or destroyed elements of heritage monuments. In terms of the notion of “least intervention” as the key to maintaining ‘authenticity’, Western heritage discourse strongly opposes the reconstruction of built heritage in which the OGIWHC states that “reconstruction is acceptable only on the basis of complete and detailed documentation and to no extent on conjecture” [10]. In fact, many scholars criticize CCPWCNH and its authenticity criteria insofar as it is seen to impose a Western ideology of heritage on the countries all over the world in a hegemonic way [11,12].

This paper aims to explore how Western AHD, and in particular the concepts of authenticity and reconstruction, influences local heritage practice in China. We select the Songshan Shaolin Scenic Area (SSSA), within which the Shaolin Temple is located, as the case study. Specifically, we will firstly examine how the authenticity criteria of the AHD has been implemented in the SSSA; this will then be followed by exploring how this implementation has influenced perceptions on “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture by local actors; and finally we conclude by outlining the spatial consequences of implementing the authenticity criteria of the AHD in the SSSA. To arrive at these aims the paper is divided into four sections, namely, a literature review, case study introduction, outline of methodology and a discussion of the results of the study.

2. Literature Review

This section examines AHD with a focus on reviewing the concept of authenticity and reconstruction in the Chinese context. The AHD refers to a hegemonic discourse concerning heritage that originated in Western contexts and which relies on the “power/knowledge claims of technical and aesthetic experts, and institutionalized in state cultural agencies and amenity societies” [5] (p. 11). Some international heritage societies, such as the ICOMOS, provide technical and professional guidance on how to preserve and manage heritage. ICOMOS establishes a set of principles and practices dominated by “expert constructions” for heritage. However, these practices in fact obscures its effects as a social and cultural process [5] (p. 88). In this regard, this dominant discourse identifies some groups, such as experts, who have the ability to use and speak for heritage while others, usually local residents, who do not. There is thus an unequal system of power relations. Furthermore the dominate heritage discourse privileges “the tangible and immutable ’things’” of the past with the features of material monumentality and grand scale to make its claims seem more real, objective, and reliable [5] (p. 300). These also concur with more orthodox perceptions of what constitutes ‘civilization’. Among these features, authenticity is one of the most significant criteria but one that also meets practical challenges relating to reconstruction in many non-Western countries.

The concept of authenticity has been explored by many scholars following two broad approaches, namely, objectivism authenticity and constructivism authenticity. Objectivism authenticity focuses on the “true nature” of museum-orientated objects usually determined by an expert ([8] (p. 93), [13]). Objective authenticity has been widely used as a criteria to measure the genuineness of material heritage. This approach focuses on the “traditional” feature of the objects and opposes commodification and commercialization. It holds that something is authentic if it is “created for a traditional purpose and by a traditional artist”, but only if it “conforms to traditional form” and not manufactured “especially for the market” [14]. Whilst very popular as a working definition in heritage studies this rigorous criteria considerably reduces the range of cultural products that can be considered ‘authentic’ in a world saturated with commodified and commercialized cultural products. For example, authenticity in the World Heritage Convention principally refers to objective authenticity, and is a standard widely accepted for the built heritage internationally. Many scholars in tourism studies have also explored the concept of objective authenticity. MacCannell argued that the primary motivation for modern tourists is the search for authenticity, a search that is confronted with the inauthentic and performative nature of tourist sites [15,16]. Boorstin describes the transition from the ‘traveler’ of times past to the ‘tourist’ of the present, a transition he regards in the negative insofar as the ‘tourist’ becomes insulated from the ‘authenticity’ of the places visited [17]. Boorstin condemns the commoditization of culture in that it transforms an ‘authentic culture’ into that of the ‘inauthentic theme park culture’. In turn objective authenticity has been criticized by ‘constructivist authenticity’ claimers who argue that there is no actual, fixed, objective reality.

Constructivist authenticity claims that all the “authentic” things are socially constructed by different actors in multiple ways [18,19,20,21]. For constructivists, there is no unique and fixed ‘real world’ independent of constantly evolving human mental activities and symbolic language [22,23]. Things seem authentic not because they are inherently or originally authentic but rather because they are the “invention of tradition” [24]. From this perspective, what heritage experts regard as “authentic” might be perceived differently from the perspectives of local residents and tourists. Scholars have since developed many new ideas on authenticity and tourism, such as “existential authenticity” [25], “performed authenticity” [26], and “subjective authenticity” [27]. In short, and to use an example appropriate to this paper, the absolute division between an ‘authentic heritage site’ and a ‘pseudo-classic theme park’ itself has become blurred since different social groups might have different perspectives on what constitutes authenticity in the first place [28].

Constructivist authenticity provides the theoretical basis for criticizing the objective authenticity criteria set in the Western AHD. The critique comes from the fact that the CCPWCNH sets the international standards of authenticity in a hegemonic way to evaluate heritages worldwide where different national contexts have different understandings and—positions. In recent years, China is one of those countries where debate has been particularly heated. From the viewpoint of translation, for example, there is no corresponding Chinese concept for “authenticity” [9] that perfectly matches the Western notion of this term. In China the matter of the material authenticity of the past and the reconstruction of built heritage was relatively uncontroversial ([29,30],[31] (pp. 40–41)). Indeed, reconstruction of built space that was authorized by the emperor was regarded as an improvement on the original [32] (p. 22). Instead, Chinese discussions of heritage architecture and heritage objects (such as ceramics, paintings, carvings and so on) focused more emphasis on how the objects promoted the Chinese virtue of ‘harmony’ both with the surrounding environment (in the case of architecture) and in terms of the tenets of classical Chinese philosophy. Furthermore, traditional Chinese architecture was mainly timber-framed architecture which was easily destroyed by war, fire or general decay. Such built heritage required frequent large-scale restoration. For example, in the 20th Century, a great deal of built heritage was destroyed according to the notions of “Destroy the Old and Establish the New” and “Attack the Four Olds (old customs, culture, habits, and ideas)” during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) [33]. In the post-1978 reform era many traditional buildings were restored or reconstructed to develop tourism, but without consideration of authenticity that matches the criteria of Western AHD [34].

In this regard it is worth noting that since the Republican Era (1912–1949) the restoration approach of Chinese built heritage has been influenced by the French Beaux-Arts architectural school [35]. More than ten Chinese students, who later became elite members of Chinese architecture, studied architecture at Pennsylvania University during the 1920s where the Beaux-Arts was most prevalent. The most influential figure was Liang Sicheng (1901–1972), whose approach to conserving built heritage was based on the notion of “repairing the old as old”, has deeply influenced the scholarship of built heritage in contemporary China [35,36,37]. By “restoring the old as old (xiujiu rujiu)” Liang Sicheng meant that restoration should restore the original features of the reconstructed object so that it has the features of being ‘old’. The Beaux-Arts school advocated historical knowledge and accurate documentation for informing the reconstruction of traditional buildings, which conformed to the authenticity criteria of the Western AHD. However, a great deal of ancient Chinese architecture lacked accurate historical documentation [38] making it virtually impossible to reach this standard. In addition, the Beaux-Arts theory on architectural “composition” and “elements” unintentionally leads to their separation [39]. That is, it emphasizes the unified style of the “elements” while altering the “composition” of the architecture beyond the authenticity requirement. Therefore, Liang’s restoration approach blurs the objective authenticity concept as understood by Western AHD but has nonetheless been very popular in China.

The reconstruction of built heritage has become a controversial issue challenging the dominance of the authenticity concept of the AHD. Due to the widespread destruction of built heritage over many decades, the reconstruction of heritage is practiced so frequently that even the UNESCO World Heritage Committee supports reconstruction projects [40,41]. In light of these conceptual challenges, some scholars argue that the concept of authenticity is better understood as a ‘process of authentication’ [42,43,44,45,46,47]. Rather than considering ‘what’ is or isn’t ‘authentic’, we can instead examine how something gains the status of being ‘authentic’ in the first place. The authentication process involves different actors that (re)construct authenticity for different purposes in terms of prevailing political, economic, or cultural conditions. The focus is not so much on what is ‘authentic’ or ‘inauthentic’, but rather, who is engaged in the authentication process and how this process works [47]. Different actors are (re)positioned differently in the authentication process, with ‘experts’ usually given authority over the opinions of ‘non-experts’. In this regard, implementing authenticity criteria of the AHD becomes an authorized authentication process, which, however, also usually leads to some spatial consequences, such as the spatial separation of heritage from daily life [42], relocations of “disharmonious” buildings or activities [43,48], restoration/reconstruction of built heritages, and displacement of local residents [43,49,50,51]. These consequences of spatial authentication follow the logic of the AHD, and in particular the Western-orientated notions of fossilization, museumification and decontextualization of heritage as static and isolated objects. Hence, many Chinese scholars have critiqued the CCPWCNH and its authenticity criteria for imposing a Western ideology of heritage upon other social contexts all over the world in a hegemonic way [11,12].

However, probably influenced by the Western AHD and the sheer scale and obvious presence of commodification and commercialization, many Chinese scholars also criticized the reconstruction of ancient buildings in recent years. For instance, many people condemned the large-scale reconstruction of the ancient walls and ancient architecture of the Ming Dynasty in Datong, the capital of Shanxi Province [52]. Thus, there is, nonetheless, some tension about the scale and intent of reconstructions. Liang’s restoration principle has no doubt legitimized small-scale reconstruction through restoring partly ruined buildings to their “original state” in a certain dynastic style. In this regard, authorized restoration or reconstruction guided by heritage experts is regarded as the legitimate authentication of built heritage. At the same time, if the reconstruction is large-scale or total, in particular if it is for touristic or commercial use, it would be condemned as artificial or fake, and simply seen as a historical theme-park.

Liang’s notions on appropriate restoration is similar to the construction of a historical theme park in that both demonstrate a history-related theme. This similarity provides technical legitimacy for the similar features between them. However, theme parks and heritage places were considered different attractions in respect to objective authenticity and operational aim (that is, commercial benefit as opposed to public good) [53,54,55]. Although tourists might perceive authenticity in the theme park [28,56], theme parks nonetheless is the commercially produced and artificial product which is the antithesis of the authenticity claims in heritage discourse [57]. For example, Disneyland, as a theme-park case, evidences the absolute boundary between the real and fake [58] (p. 255). The theme-park features of Disneyland do not claim to be ‘authentic’ but rather they explicitly display a realm of fantasy and encourage tourist performativity. Recent research in China indicates that some heritage-based villages clearly display the features of a Disneyland-style theme park [59,60].

From the above literature review it is clear that the Western AHD, and in particular the authenticity criteria, has spatially influenced local heritage practice in China in terms of authentication and reconstruction. However, how the spatial change of authentication and reconstruction influences the perceptions of local actors on “authentic” heritage and culture, and the resultant consequences, have not been examined. This paper takes the SSSA with the Shaolin Temple as the case study to explore these research questions and fill in the research gaps.

3. Historic Background of the Case Study

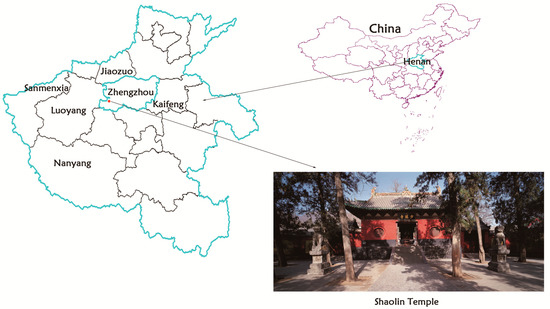

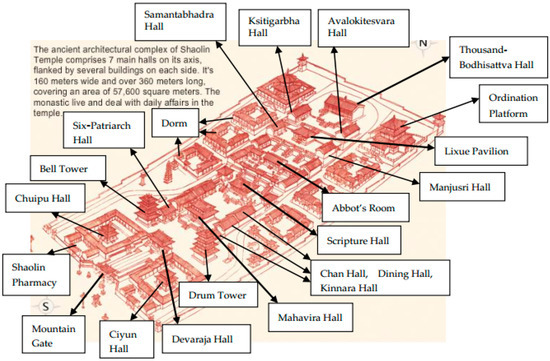

The Shaolin Temple (ST) is located in Dengfeng County, Zhengzhou City, Henan Province, China (Figure 1). The buildings in ST are indicated in Figure 2. As part of the World Cultural Heritage “Historic Monuments of Dengfeng in ’The Centre of Heaven and Earth’”, the ST has witnessed numerous and huge spatial transformations in its history of more than 1500 years. Known as an “imperial temple”, ST was built by Emperor Xiaowen of the Northern Wei Dynasty in 496 CE for the Indian-born monk Batuo to study Buddhism and practice meditation [61]. In order to establish good relations with imperial emperors in line with Confucianism philosophy, Shaolin monks actively provided military support for imperial powers by developing Shaolin martial arts during the Tang (618–917) and Ming dynasties (1368–1644), as well as religious support during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) [48]. Shaolin’s reputation is based on Shaolin martial arts and Chan (Zen) Buddhism. Its fortunes were significantly influenced by the change of dynasties and its relationship with the imperial court. During the course of its long history the Shaolin Temple has been destroyed and reconstructed more than 20 times. The spatial scale of the temple complex also changed significantly in respect to the number of monks and amount of temple lands. During the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), the ST complex contained more than 5000 rooms, housing more than 1800 monks [62] (p. 5) and controlled more than 23 smaller temples [63] (pp. 238–239). However, by contrast, the number of monks was no more than 20 when it was attacked by Emperor Liyan in 847 during Tang dynasty (618–907) [64]. In short, the Temple was a traditional space of religious and martial practice influenced strongly by the vicissitudes of changing dynastic powers.

Figure 1.

Location of Shaolin Temple (by Author).

Figure 2.

Buildings inside the Shaolin Temple (ST). Revised by Author from [65].

Due to its participation in military combat during the Republican period (1912–1949), the ST lost most of its buildings in 1928 when a fire broke out and burned for 45 days [65]. The ST survived, but with China at war with Japan (1937–1945) and on top of civil war from 1945–1949, not much happened until 1949 with the founding of the PRC. After 1949 Mao Zedong attempted to impose a form of totalistic cultural iconoclasm on China and establish a new Chinese socialist culture in place of ‘feudal’ traditional culture [31] (p. 15). As a religious site of perceived feudalism and superstition, the temple experienced serious attack under Mao’s radical socialism. Furthermore, the land reforms (1949–1953) forced the ST to forfeit the majority (99%) of its land holdings and only 14 frail and elderly monks were left [66]. Shaolin martial arts were also criticized and later forbidden to be practiced during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) [67] (p. 196). The Temple was formally incorporated into the 23rd Agriculture Production Team of nearby Guodian Village, thus losing any vestiges of organization and economic independence.

Under Deng Xiaoping’s Economic Reform and Open-door Policy, ‘traditional culture’ was revived and used to promote specific locations and attract inbound tourists for economic benefits [68]. Most of the buildings in the ST were reconstructed to develop tourism in the 1980s and 1990s. The policies of ‘reform and openness’ focused on economic modernization in which local governments were expected to find effective ways to develop their local economies. The Dengfeng government selected tourism as the economic tool and decided to reconstruct the ST in light of two events. The first was that the Japan World Shorinji Kempo Organization visited the ST three times in 1979, 1980, and 1981 [69] (p. 108). This led the Chinese government to recognize the significance of the ST as a diplomatic platform to communicate with foreign countries. The second was that the film The Shaolin Temple (starring a young Jet Lee in his debut film) was released in 1982. The film was the first Hong Kong production on mainland China after the long suppression of the Cultural Revolution. The film was hugely successful and attracted an audience of over one billion [70]. In the wake of the success of the film large numbers of tourists travelled to visit the ST in the years that followed. For instance, approximately 2,470,000 tourists visited the temple in 1986 [48]. These two events motivated the Dengfeng government to reconstruct/construct the ruined buildings in order to cater for the large number of tourists. Altogether on the original sites 10 halls with 44 rooms were restored and nine halls with 47 rooms were rebuilt. In addition eight completely new halls with 44 rooms were also constructed [71] (p. 158). The main items of the restoration and reconstruction project are listed in Table 1. Clearly, except for the Mountain Gate, the Abbot’s Room, and the Thousand-Bodhisattva Hall, four main halls (Devaraja Hall, Mahavira Hall, Scripture Hall, Lixue Pavilion) at the central axis were all totally rebuilt from scratch.

Table 1.

Main Items of Restoration and Reconstruction in the 1980s and 1990s.

Post-Deng Communist Party leaders, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, and Xi Jinping, have highlighted the construction of ‘socialist spiritual civilization’ that seeks to use traditional Chinese culture to influence the moral conduct of the population [72,73]. The period from the late 1990s to 2010 saw local governments (including the provincial, city-level, and county-level governments) work together to upgrade the cultural heritage of Dengfeng to World Heritage status [69] (pp. 70–76). They invited external heritage experts and agents to re-plan the SSSA in line with the criteria of authenticity and integrity of the OGIWHC. The spirit expressed by the planning was based on an ancient and romantic Chinese poem, “Remote Mountain Hides Ancient Temple, and Blue Brook Locks Shaolin”, referring to the pristine environment that the ST was once situated within. Heritage reconstruction in China has often drawn from romantic imagery [5] (p. 20). The planning, however, regulated that all the local residents and their houses, shops and other ‘disharmonious buildings’ in the core-protected zone (2.18 sq. km.) should be relocated out to make the SSSA “authentic”. As a result, most of local residents nearby the Temple were forced to displace to a newly-constructed residential community, far from the SSSA.

In 2010, the ST was successfully listed as part of the list World Cultural Heritage. However, in 2010 due to the high economic cost of the authentication projects, the Dengfeng government changed its governance model of the SSSA from a government-operated institution into a joint-venture-managed institution. A listed company, the China Travel International Investment Hong Kong Limited (CTINHKL), was engaged to co-manage the SSSA with the local government. A new company was established to manage the SSSA with CTINHKL holding a 51% share and local government holding the remaining 49% [74]. The local government expected the new joint-venture company to be listed, but this was strongly opposed by Abbot Yongxin on the basis that it would undermine the Buddhist principles of the Shaolin Temple [69] (pp. 195–199). It was also strongly opposed by many influential heritage experts [75]. As a result the new joint-venture company was not listed. At the same time, the CTINHKL was warned by the 5A Evaluation Committee (the SSSA is rated as a ‘5A’ scenic zone, the highest classification within the Chinese system) of the China National Tourism Administration (CNTA) in 2011 to improve its poor managerial circumstances [76]. The CTINHKL managerial model was deemed to be too commercial. The CTINHKL, local government, and Shaolin monks have become three main stakeholders but with numerous conflicts (as we shall see below).

4. Methodology

This study uses the constructivist paradigm with a qualitative approach and case study. This paradigm is appropriate with the aims of exploring the ways of implementing the authenticity criteria of the AHD, its influence on the perceptions of “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture by local actors, and its spatial consequences on the SSSA. Constructivism acknowledges that realities can be apprehended in the form of multiple, intangible mental constructions while the constructions are formed socially and locally [77] (p. 110). This intersects with the notion that the formation of Western AHD authenticity criteria is based on constructions for Western contexts by Western heritage experts while its implementation in China is based on constructions for adapting Western AHD to the Chinese context by Chinese heritage experts. As constructivism indicates, these constructions are dependent on social groups and individuals, who have different subjective interpretations and understandings of the same social reality [23] (p. 125). This also concurs with the view that local actors might have different understandings and perceptions on the authenticity of Shaolin heritage and culture when the authenticity criteria is implemented in the SSSA. Constructivism admits that social actors who have higher positions have more influence on the same social realities [78], which in turn links to the spatial consequences on the SSSA (to be addressed further below).

A qualitative approach is appropriate to the adoption of a constructivist paradigm [79]. In this regard the research uses four kinds of data: documentation, archival records, observation, and in-depth interviews. The fieldwork was conducted in the SSSA and relocated Shaolin residential community over the period from October 2015 to February 2017. The documents consist of official documents (such as the Detailed Planning of Key Areas of the SSSA, 2002; and the Proposal of Restoring the Shaolin Kernel Compound, 2003), newspaper articles, and relevant scholarly papers. These documentation and archival records provide the information on the implementation of authenticity criteria of the AHD in the SSSA. Observation was used on location for gathering information on the restored/reconstructed buildings and environment, which could help to better understand features of material aspects of “authentic heritage” linking to authenticity criteria of the AHD. Observation also includes the residential conditions of displaced local residents, the everyday behavior of displaced local residents and Shaolin monks, and the status of Shaolin martial arts performances. Such observation helps to better understand the perceptions and attitudes of residents and Shaolin monks in regards to the intangible aspect of “heritage”.

As the “construction site of knowledge” [80] (p. 2), interviews provided opportunities for the researcher to obtain information, feelings, and opinions from the interviewees through questions and interactive dialogue [81] (p. 219). In-depth interviews were conducted with twenty-seven local residents (Table 2), three experts, four managerial persons (three from the SSSA and one from the ST), and three local officials (from the Construction Bureau, Tourism Bureau, and Heritage Bureau). All the interviews were carried out face-to-face within a period of one to two hours. The interviewed topics with the three experts mainly focused on their understanding of the authenticity concept and criteria, such as how they regard authenticity theoretically and how to best obtain authenticity criteria in heritage practice in the Shaolin project. Interviews with local residents involved such topics as how they feel about the influences of World Heritage authorization on their daily life, their attitudes towards “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture, and how they understand their own connections to “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture. The topics of the interviews with the four managerial persons included the changing managerial models and relations of the SSSA and the ST, the content of which aids in understanding the consequences of implementing the authenticity criteria of the AHD. The interview with the managerial person from the Temple includes the views on “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture from the perspective of the monks. The interviews with the three local officials mainly involved the implementation of authenticity criteria and their views on “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture. Interview data from experts, managerial persons, and local officials were cross-checked and compared with the arguments presented in articles, newspapers and other documents.

Table 2.

Profile of Respondents.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the main findings from the collected data and then discusses the contributions to the AHD in regards to authenticity and reconstruction. The main findings are presented in three parts, which relate to the core aims of this paper. The first part presents the detailed processes of preparing for World Heritage inscription in respect of implementing authenticity criteria. The data for this are mainly derived from documentation and interview data of heritage experts, managerial persons, and local officials. The second part presents the views on “authentic” Shaolin heritage/culture from the perspective of local residents and Shaolin monks, in which the data are mainly based on the interview of local residents and Temple manager with field observations and some newspaper articles used in support. The third part presents the spatial consequences of implementing authenticity criteria in the SSSA, in which the data are derived from field observation, interview of managerial persons and local officials, and some relevant newspaper articles.

5.1. Implementing Authenticity Criteria of the AHD

In 2000, the local government of Dengfeng decided to submit ‘Songshan Heritage’ (within which the ST was included) to World Heritage inscription. The government established the ‘Leading Team of Applying for World Heritage’ with the Zhengzhou mayor as the team leader [82]. They invited the Planning Institute of Tsinghua University to re-plan the Songshan Shaolin Scenic Area. The ‘Detailed Planning of Key Areas of the Songshan Shaolin Scenic Area’ was subsequently prepared by Tsinghua University and approved by the Ministry of Construction in 2002 [83,84]. As one heritage expert interviewee said, “This planning was mainly for World Heritage authorization. There were some strict regulations. For example, the core-protected zones should be very ‘clean’ and without residents.” In order to meet the authenticity criteria of World Heritage inscription, two authentication projects were launched from 2000 to 2009, namely, the external-temple authentication and internal-temple authentication.

5.1.1. External-Temple Authentication

The external-temple authentication project forcibly removed most commercial businesses that had appeared in the 1980s and 1990s to make the SSSA environment more “authentic”. Due to the rapid tourism development in the 1980s and 1990s an unregulated commercial street about one kilometer from the scenic zone gate to the actual Shaolin Temple gate had formed, packed with 690 stores, 37 private martial arts schools, and 43 enterprises and government departments [83,84]. Local government departments, Shaolin monks, and local residents all participated in the tourism businesses at that time. However, most of these businesses were regarded as negatively influencing the “authenticity” of the Temple. The perceived ‘unsophisticated’ businesses of the local residents was highlighted for particular criticism. The local official interviewee from the construction bureau informed the researchers that, “The tourism services of local residents were very low-level and unsightly in the 1980s. They were disharmonious to the expected pristine and authentic (zhenshi) environment of the Shaolin Temple. You could understand that [such a situation would arise] just at the beginning stage [of tourism development]. Everyone was doing tourism business. You cannot imagine the noise at that time. Now it is much better. The environment is clean and tidy […] more authentic to the expected peacefulness of a Buddhist temple”. Clearly, authenticity here means primitive, clean, tidy, and quiet without “low-level business”. Labeled as ‘disharmonious subjects’, all the businesses and people were ordered to relocate in order to construct an “authentic” external-temple scene.

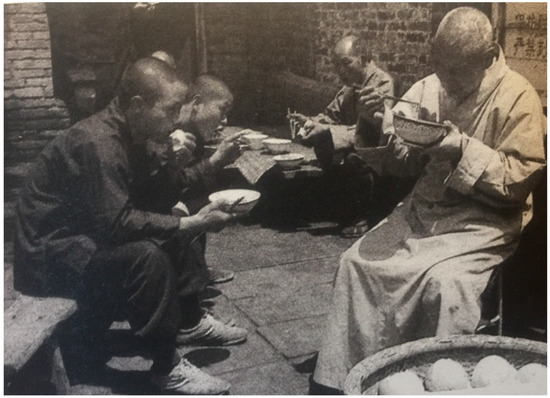

The authenticity in this context of conducting business refers to formal and high-level commercialization. The Shaolin monks and government sectors also participated in tourism businesses in the 1980s and 1990s. They upgraded their businesses to adapt to the authenticity requirement of World Heritage inscription. Just as the managerial interviewee from the ST said, “At that time (1980s), the monks lived very poorly, without enough food. Although there were Temple entrance tickets from the mid-1970s, the monies earned didn’t belong to the Temple until 1985. So, when tourists came, they [the monks] sold some ’small’ and ’simple’ souvenirs to make a living.” The interviewee kindly gave me a book and showed me one picture revealing the poor life of the monks in the 1980s, as indicated in Figure 3. This interviewee continued, “Monks also organized a team for martial arts performance for tourists earlier named the Shaolin Wushu Team. Later, it was upgraded to the Shaolin Wu Seng Tuan (Shaolin Warrior Monk Corps, SWMC) around 1990. The SWMC resembled the warrior monks of traditional times […] This looks more authentic (bizhen) […] Now all the cultural activities we do are formal, such as [creating] Shaolin Medicine from the Shaolin Pharmacy”.

Figure 3.

The poor life of Shaolin monks in 1985 [69] (p. 15).

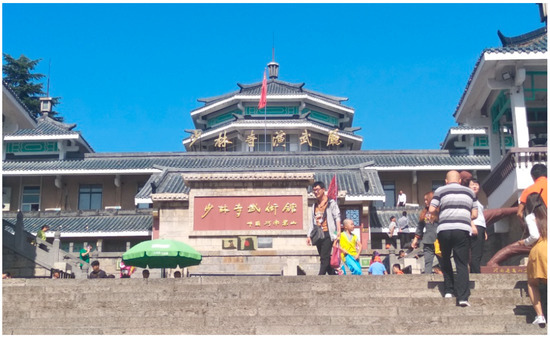

Government departments also operate some tourism businesses, as one managerial person interviewee from the SSSA told me, “The Shaolin Temple Wushu Training Center (STWTC) was jointly constructed by the China National Tourism Administration and the Henan Provincial Tourism Administration in the mid-1980s. It firstly provided stage-performances of Shaolin martial arts for tourists, and then it expanded its businesses to a hotel, travel services, a martial arts school, souvenirs […] Now the performance is higher-level, better than the previous”. When one of the researchers walked into the SSSA, she saw the traditional-style STWTC and took a photograph as seen in Figure 4. According to the guidebook, the STWTC is located at the place 700 m east of the ST, covering 50,000 square meters. The managerial interviewee from the Temple told the researcher that the Ten Party School of Chan (Zen) opposite to the Shaolin Temple gate was operated by a local government department, the Shaolin Holiday Village of the Songshan Management Council providing accommodation, catering, conferences, and physical outdoor training services. All the remaining services in the SSSA are operated by various departments of local government [85]. These commercial businesses are now formal, larger-scale, and at higher-level of sophistication and standards than the previous businesses.

Figure 4.

The Shaolin Temple Wushu Training Center (STWTC), photo taken by one of the authors.

5.1.2. Internal-Temple Authentication

The internal-temple authentication project, launched in 2004, refers to the authentication of the buildings within the ST through the process of restoration and reconstruction. The “Proposal of Restoring the Shaolin Kernel Compound” was planned and evaluated by a heritage expert panel and review, which included heritage experts and heritage administrators. Guo Daiheng and his group from Tsinghua University undertook this planning, which was in turn evaluated by Luo Zhewen and 22 other heritage experts appointed by the State Administration of Cultural Heritage [86]. In fact, both Guo and Luo were students of the aforementioned Liang Sicheng. The proposal was approved and the project was enacted from 2004 to 2006. Three kinds of authentication approaches were used in the project [71] (pp. 163–165). Firstly, some buildings were restored to look more “authentic”, including Lixue Pavilion, Daravaja Hall and Bell Tower. Secondly, some disharmonious buildings were dismantled to make the total environment more “authentic”, including 44 buildings and 320 rooms. Thirdly, some buildings were reconstructed/repaired in the Qing-dynastic style, including Kinnara Hall, Six-Patriarch Hall, Ordination Platform, Shaolin Pharmacy, eastern/western monk dorms, Ciyun Pavilion, Chuipu Pavilion and some other pavilions, as shown in Figure 2. Hence the restoration of most buildings can be considered to have amounted to “major surgery”.

The “authenticity” of buildings is relative and negotiated and reconstruction in traditional style is accepted. Most buildings had been reconstructed and restored in the 1980s and 1990s. However, the authentication of this time aimed to make the buildings more “authentic”. What is meant by “authentic” in this context? One heritage expert interviewee explained, “The internal-temple authentication selects the Qing-dynastic style as the main style because the Qing Dynasty is more recent with more buildings and records [to draw upon]. The method is that of restoring the old as old’ [referring to the famous notion of Liang Sicheng discussed above]. This could make the buildings look authentic (yuanzhen), and hence very popular in the heritage restoration field”. When asked how to view the reconstruction problem, another heritage expert stated that, “Reconstruction is usually a ’must’ choice. Without reconstruction there is no current Shaolin temple. Similar situations exist in other areas of China where, as you know, the Cultural Revolution destroyed a lot of old buildings”. One heritage expert interviewed also expressed that authenticity is a relative concept, “Authenticity is usually a relative concept. The reconstruction and restoration at this time were more authentic than that in the 1980s and 1990s. The previous reconstruction was mainly based on older people’s memories while this time it is more accurate and authentic, because we have some copied photos brought by Abbot Yongxin from Japan as a reference. These photos were taken by Japanese visitors in the early 1920s before the 1928 disaster”.

Internal-temple authentication also considers the requirements for the religious life of the monks. For instance, some new buildings were constructed to meet the needs of the monks religious life in the contemporary world. As the ST interviewee said, “We keep some areas private for the monks’ religious life. Anyway, the ST is firstly a religious place and then a tourist site […] For example, some dorms and meditation rooms were constructed alongside the axis line in an inconspicuous way so that the monks could live their religious life without influencing or being influenced by the tourists […] Another case is the reconstructed Ordination Platform. It was reconstructed to resume the tradition of large-scale Precept-imparting Ceremonies, which existed from the Tang to the late Qing dynasty. These buildings were constructed to meet religious rather than tourism needs. Generally, tourists are not permitted to enter these places”. The interviewee from the construction bureau provided revealed that the monks contributed RMB 50 million to the authentication project.

5.2. Local Actors’ Perceptions on “Authentic” Shaolin Heritage and Culture

Regarded as “disharmonious subjects”, local residents and their businesses and houses were forced to relocate far outside from the SSSA. Due to serious opposition the relocation projects were launched three times from 2000 to 2004 [87]. As a local official interviewee recalled, “The government tried best to relocate them out […] establishing a special company with the vice mayor as CEO to do this […] all the Dengfeng government officials were required to participate in the project and persuade them [to relocate] out”. Finally, almost all the residents (442 households) were reluctantly relocated out to a newly-constructed community, 20 km away from SSSA. This section presents the perceptions on “authenticity” of Shaolin heritage and culture from the perspective of local actors. Here local actors includes both Shaolin monks and local residents.

Shaolin monks and local residents both emphasized the intangible aspects of “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture. Monks regarded Chan (Zen) Buddhism as the first point of authentic Shaolin heritage and culture. As Abbot Yongxin expressed many times, “The key of Shaolin martial arts is not the technical skill of martial arts, but Chan Buddhism […] The ST, as a material carrier of Shaolin culture, could be destroyed and reconstructed many times, while only Chan Buddhism with its practice as the core of Shaolin culture has never changed” [69]. When asked if commercialization would influence the authenticity of Shaolin heritage and culture, the ST interviewee said, “Shaolin culture is a big cultural system with Chan Buddhism as the center. What we commercialize is Shaolin martial arts and Shaolin medicine, not Chan Buddhism. The commercialization of Shaolin martial arts and medicine will not influence the authenticity of Chan Buddhism”. Another aspect the monks focused on in terms of authenticity is the long history of Chan Buddhism in the ST. As the ST interviewee said, “The Temple was not so significant. It could be destroyed while the authentic Shaolin spirit of ’Chan Buddhism’ has been continued for more than one thousand years”. Clearly, for the monks, the authenticity of Shaolin heritage and culture is always focused on the Chan Buddhism.

Although also focusing on intangible aspects, the local residents viewed the authenticity of Shaolin cultural heritage in a different way from the monks. The local residents did not care about the material authenticity of the buildings. As one local resident interviewee said, “Of course, we local people knew those buildings were just newly reconstructed, but who cared […] no one. Many tourists came here to visit the ST. They didn’t care, either. It was really there, and that’s OK”. Instead, they emphasized their contributions to inheriting Shaolin martial arts in history, in particular during the Maoist and early Dengist eras. As one local resident interviewee explained, “My grandfather practiced Shaolin martial arts much better than most Shaolin monks at his times […] around 1950s and 1960s […] At that time, there were few monks in the ST”. In fact, several local resident interviewees described their family stories about practicing and inheriting Shaolin martial arts. Some residents said their family has practiced Shaolin martial arts for five or six generations. One old resident interviewee who opened a martial arts school told me his experience of representing and performing Shaolin martial arts for the Japan World Shorinji Kempo Organization in 1979, “In the 1960s and 1970s, in particular during the Cultural Revolution, Shaolin martial arts were forbidden to practice. I liked Shaolin martial arts and sometimes hid myself so I could practice it during the night […] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the Japanese visitors came to visit the Shaolin Temple, we [referring to ’folk martial artists’ such as himself) displayed Shaolin martial arts for them […] To some extent, we saved and inherited the Shaolin martial arts at that time, not the monks, their position at that time was very low”.

Local residents thus have their own views on evaluating the “authenticity” of Shaolin martial arts. Most resident interviewees expressed the notion that the current Shaolin martial arts performances were not “true”. One resident interviewee said, “The Shaolin martial arts were very true(zhen) when I was young. At that time, martial arts were much more simple but that was authentic (zhenzheng de) Shaolin kungfu, not like the current kungfu performance, which are too exaggerated, just like a dancing show. [These performances] lose the taste of Shaolin kungfu […] The current performance is just for looking good, for those who don’t know the true kungfu”. This was also verified from the ST interviewee, who said one of their criteria for selecting SWMC members was that they were “good-looking”. When asked if the martial arts performances of the Shaolin monks are similar or different from others, most resident interviewees replied that they were the same or similar. One interviewee even said that most members of the SWMC were selected from locally commercial martial arts schools. Only two resident interviewees indicated that the SWMC performance was more “authentic” than those of the martial arts schools. Clearly, they have their own standards of “authentic” Shaolin martial arts, which are more embedded in the local environment and history.

Displaced local residents also emphasized their deep emotions to Shaolin cultural heritage through generations of dwelling nearby the ST. The government constructed two-story 200-square-meter villas for relocated residents to rent and buy at very affordable prices, but most residents expressed that they did not want to leave their houses where generations of their families had resided. The local residents had very strong emotional attachments to the place of their ancestors, as is common in Chinese culture [88]. As one local resident interviewee said, “It’s my home. I lived there since I was born. It’s the place where generations of my family resided. Although the houses were shabby, we were used to living there […] just as we were used to Shaolin culture”. Almost all the local resident interviewees recalled their memories of living in the SSSA. As one told one of the researchers, “Even now, I usually reminisce about the previous houses, previous businesses, previous lands for planting crops […] The new modern-style villas with modern facilities I am living now could not give me a family-feeling”. Some resident interviewees expressed their pride and happiness of living in the SSSA previously and the embarrassed situation now. As one said, “In the past we were admired by many people because we could benefit from our area […] while now we have to find other jobs to make a living. This is very difficult for us”.

5.3. Spatial Consequences

After the external and internal temple authentication projects, the SSSA has witnessed spatial change in regards to its material aspect with a change in the managerial model and the “upgraded commercialization” of Shaolin culture. These two features of the SSSA post-authentication will be discussed in this section.

The appearance of the post-authenticated SSSA is a uniform traditional style. When the fieldwork was undertaken, the researcher noticed that all the buildings, tourist facilities, and souvenir shops were in a uniform traditional style, the style of the Qing Dynasty as discussed above. As a tourist and researcher without detailed background knowledge of traditional buildings of this style, the researcher could not distinguish whether they were reconstructed in line with “original documents” or simply newly constructed. Figure 5 shows the comparisons of commercial scenes from the 1980s and the current situation. Compared to the earlier commercial streets in the 1980s and 1990s, these traditional style facilities are regarded by managerial persons of the SSSA as “high-class” and “superior”. As one SSSA managerial interviewee said, “We upgraded many tourist facilities, such as the Tourist Center, Commercial Service Center, Central Square, and an extensive parking area […] These facilities are much more modern than those of the past, very high-class, and superior”.

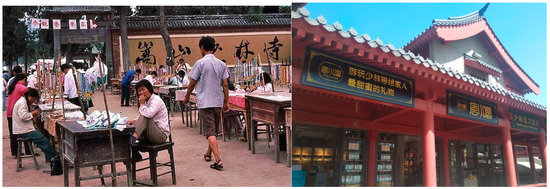

Figure 5.

Comparisons of commercial scene in the 1980s and the current situation (the first photo from [89] and the second one taken by one of the authors).

The cultural activities in the SSSA are also packaged in a traditional style. The Shaolin martial arts are performed both in the ST and the STWTC. Both of them are labeled as performing “traditional” Shaolin martial arts. As the managerial interviewee from the ST said, “The Shaolin Warrior Monk Corps were established in 1989. In recent years, we try to express the traditional taste of traditional times […] They perform true Shaolin Kungfu. It is a kind of Chan Wu, full of cultural atmospherics, much better than other performances”. When asked about the commercial businesses of the Shaolin Temple, the interviewee from the ST said, “We established a company in 1998, called the Henan Shaolin Temple Industrial Development Co., Ltd. The main businesses are based around Shaolin culture, such as kungfu performances, kungfu films, and Shaolin souvenirs […] We try to inherit and expand Shaolin culture, providing high-class Shaolin cultural products”.

The change in the managerial model of the SSSA was meant to upgrade the Shaolin heritage-based tourist products from 2010 onwards. Before 2010 the managerial institution was dominated by the local government. As a local official interviewee indicated, local government managed the ST from 1974 to 1984. From 1985 to 1995 the monks charged RMB8 per person for admission to the temple while other scenic entry fees were operated by local government. From 1996 to 2010 all the tourist spots were bound together by the local government to sell one consolidated entry ticket with about 1/3 allocated to the temple. However, the creation of the joint company weakens the status of local government in the management of the SSSA and ST. Another local official interviewee said, “The new managerial model was expected to upgrade the services of the SSSA while in fact it proved unsuccessful […] The SSSA was warned by the 5A evaluation committee from the China National Tourism Administration to improve and rectify this within a limited time in 2011 […] This is really a big humiliation, and never happened before […] The aim of the managerial company is only to make money”.

5.4. Discussion

This paper examined how the Western AHD, and in particular reference to the concepts of authenticity and reconstruction, influences local heritage practice in the SSSA in China. The examination included the implementation of authenticity criteria in the Western AHD by heritage experts and local governments, the perceptions of “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture by local actors, and the spatial consequences of implementing authenticity criteria in the SSSA. As many Chinese scholars indicate, the concept of authenticity, both as a Western concept and criteria, confuses Chinese people in many aspects [25,26,27,30,42]. This final section analyzes the key findings around the views on authenticity and their influences on heritage practices in the SSSA of different actors.

By examining the implementation of authenticity criteria in the SSSA, this paper finds that objective authenticity criteria in the Western AHD becomes a dynamic process characterized as a process of “authentication”, which aims to: firstly make the environment more clean and tidy, and the commercial businesses more formal and “high-level” through excluding the participations of local residents in tourism businesses; secondly, making the buildings look more “authentic” through restoring and reconstructing traditional style buildings according to the opinions of experts based on historical records rather than the recollections of local monks and residents. Smith indicates that the Western AHD is a hegemonic discourse relying on the technical guidance of heritage experts and state cultural agents [5] (p. 11). The findings here demonstrate that the influence of Western-orientated AHD on local heritage practice in China is expressed in both hegemonic and negotiated ways by recognizing the presence of a Chinese-orientated AHD. The outcome is a Western-derived AHD that incorporates Chinese attitudes towards the past. This Chinese-orientated AHD combines understandings on Western authenticity criteria by Chinese heritage experts adapted to the circumstances of Chinese built heritage, such as that characterized by timber-framed architecture that is easily damaged. Under these circumstances where historically building underwent a process of almost constant reconstruction the issue of material authenticity of built heritage was not rated as so important in the Chinese context [29,30]. In addition many ancient buildings were destroyed during the Maoist era [31]. Thus the attitude towards the reconstruction of heritage architecture in China is much more ‘relaxed’ than it is within Western contexts.

The external-temple authentication reveals the hegemonic influence of the AHD in that the local residents were forced to relocate outside to “purify” the integral environment of Shaolin heritage regardless of their contributions to inheriting Shaolin martial arts during the Maoist period or having resided in close proximity to the ST for generations. Just as objectivist authenticity focuses on the knowledge/power [8] (p. 93) and heritage experts, the external-temple authentication demonstrates the determinate role of experts in removing the “disharmonious scenes” to make a “clean”/“tidy” environment more befitting a contemporary world-class tourist attraction. In fact, what the external temple authentication project removes is the real scene of the SSSA that formed during the Dengist era. By contrast, the internal-temple authentication project involving the restoration/reconstruction of Shaolin built heritages in Qing-dynastic style, demonstrates the negotiated nature of authenticity criteria according to the heritage principles of CCPWCNH and OGIWHC. As reviewed previously, Liang’s “repairing the old as old” contradicts the authenticity criteria in the Western AHD by emphasizing the unified style of “elements” while altering the “composition” of the architecture. Furthermore, many of the reconstructions in this project, such as the Ordination Platform and Shaolin Pharmacy, also contradict the authenticity criteria. This provides technical legitimacy to the authority of the experts on objective authenticity criteria, which is in fact a negotiated outcome rather than an objective condition. Another negotiation in this process is reflected by the heritage experts considerations of the Shaolin monks’ requirements for their religious life. The Western AHD focuses on the material monumentality of heritage without considerations of local voices or uses [5], while the SSSA case shows that the Shaolin monks take the semi-role of experts and local users of the built heritages. In this regard, built heritages in the ST are not the protected static objects, but have some extent of living features for current religious functions.

By examining the perceptions on “authentic” Shaolin heritage and culture by local actors, the paper finds that both Shaolin monks and local residents perceive the intangible aspect of authenticity differently. The Western AHD emphasizes the tangible and immutable aspect of heritage which could make expert claims more concrete and therefore more convincing [5] (p. 300). By contrast, common people, the local residents in this case, construct their views on authentic heritage in a different way [30]. That is, Shaolin monks view Chan Buddhism as the key factor of authentic Shaolin cultural heritage while local residents regard authenticity as a factor that is contextualized in their previous community by emphasizing their contributions and memories of inheriting Shaolin cultural heritage in certain eras (such as in the practice of Shaolin martial arts), and their emotional attachments to the dwelling place of their ancestors. Clearly, both Shaolin monks and local residents try to claim their legitimacy to “own” authentic Shaolin cultural heritage by focusing on their close links to the legacy and history of the Shaolin Temple. However, local residents, limited by their low positions in the heritage system, have no authorized power to express their opinions. As a result, even though they contributed a lot to inheriting Shaolin heritage during the Maoist and early Dengist era, they were still forced to relocate and lost their opportunities to benefit from heritage tourism in the SSSA. In contrast to the local residents, the Shaolin monks’ claim on “authenticity” of Shaolin cultural heritage is enforced. Furthermore, Shaolin monks even take the semi-role of experts, as discussed above. In this regard, Shaolin monks are empowered while local residents are disempowered within the re-positioned power structure of the ST heritage system. Considering the above analysis, authenticity here is similar to what Bruner called “authentic reproduction” [18], involving who has the right to authenticate and determine what is “heritage”.

By examining the spatial consequences of implementing authenticity criteria as outlined above, this paper finds that the final result is in a uniform “traditional style” of both architecture and cultural activities, one that has the features of a Chinese orientated AHD with theme park features. In this regard, the “invention of tradition” finds synergy with political and economic uses of heritage [24], in which the apparent traditional-style circumstance is usually constructed in the name of authenticity but is more a result of negotiation and the authorial status of experts and government [43]. Furthermore, this traditional-style culture that has been deployed is regarded both by the SSSA managerial team and Shaolin monks as “high-class” and “superior”. In contrast, the tourist services provided by local residents are stigmatized as low-level and unsightly. Therefore, the authentication here is in fact the processes of excluding the individual tourist services of local residents while integrating and expanding the commercial businesses of powerful stakeholders. This, in turn, strengthens the similarities of the SSSA to a historical theme park in which authenticity is subsumed within a commercial business model. The presence of local residents could have provided evidence of the embeddedness and rootedness of heritage in the community. Instead they were forced to relocate and effectively removed as part of the local heritage environment. By contrast, professional performers replace those of the locals and thereby further reinforce the artificial and pseudo-classic features of the theme park whilst at the same time claiming to be authentic [56,57]. The cultural heritage of the nearby community whilst different from the ST culture itself is nonetheless just as legitimate (at least in the eyes of the locals if not the AHD experts) [48]. In summary, without the local residents as the community base, the SSSA is more like a theme park. As a result, the consequences of heritage authorization, including the unity of the reconstructed traditional stylistic environment, the excluding of the local residents, the “upgrading” of commercializing the Shaolin culture, and the managerial institution, made the SSSA more characteristic of a theme park rather than the original heritage intentions of World Heritage inscription. This, we would argue, is a process that has been replicated across many sites in China, and indeed in many other countries.

6. Conclusions

This paper aimed to explore different ways in which the Western AHD influences local heritage practice in China. Three related research aims are met through examining different understandings on authenticity and their influences on the heritage practice in the SSSA by different actors (namely, the monks, the government, the commercial developers and the former local residents). In summary, this paper applies Laurajane Smith’s AHD theory to analyze the inappropriate aspects of the Western AHD in a Chinese context, in particular the controversial debates on the concept and criteria of authenticity. Theoretically, it is a contribution to extending the Western AHD to a Chinese context. Practically, it has some implications on the spatial transformation of the heritage site into a theme park.

The SSSA case indicates that the implementation of authenticity criteria of the Western AHD influences Chinese heritage practice both in hegemonic and negotiated ways, in which a Chinese AHD is formed with the combined characteristics of Western AHD with Chinese characteristics. Similar to the Western AHD, the Chinese AHD also has an authorized heritage expert system whose claims on authenticity are much more influential than those of local residents. Furthermore, the expert knowledge on heritage makes their claims more legitimate, no matter that the restorations/reconstruction approach of built heritage contradicts the authenticity criteria according to Western AHD. By contrast to Western AHD, the Chinese AHD has its own features in that the intangible aspect of heritage is considered to some extent. Although the perceptions and contributions on “authentic” Shaolin cultural heritage of local residents are not considered, the requirements on religious life of the Shaolin monks is addressed thus demonstrating a willingness to favor the religious life of monks and not those of the local community. It is a big challenge to mediate the authorized legitimacy of heritage experts in that some local actors have some extent of agency to compete with the stable AHD.

In practice, this paper has some implications about authentication projects. In fact, what different actors/groups expect to construct in the authentication process is just emphasizing their contributions and links to Shaolin cultural heritage. However, situated within the repositioned power relations in heritage, the authentication project removes the real scene of the SSSA that came about during the Dengist era. Notably, it excludes the contributions to inheriting Shaolin cultural heritage by local residents during the Maoist era. Without the real scene and residential community, the SSSA has more tendency to a pseudo-classic theme park in traditional style culture. The ‘theme park’ here is planned by heritage experts with a united Qing-dynastic style environment and managed by a joint-venture company with upgraded commercialization of Shaolin culture. Paradoxically, in the name of protecting authentic cultural heritage, the heritage authorization in the Shaolin case excludes the local resident space and results in its tendency towards being a pseudo-classic theme park rather than an ‘authentic’ heritage site in which all stakeholders are acknowledged and respected.

This paper, however, did not consider tourist perceptions on the authenticity of the SSSA. This paper is mainly focused on how perceptions on authenticity of different agents have shaped the spatial transformation of the SSSA. Although there are lots of public comments in the media on the commercialization of Shaolin culture, the experiences of tourists on the SSSA have not been specifically explored. Their experiences and expectations might be a significant factor that drove the spatial transformation. Therefore, future research should focus on tourist experiences on the authenticity of the SSSA and how their experiences have possibly shaped the spatial transformation of the SSSA.

Author Contributions

Supervision, C.S. and G.S. Investigation and Writing, X.S.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China [41601145] and Program for Science & Technology Innovation Talents in Universities of Henan Province [19HASTIT030].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Winter, T. Clarifying the critical in critical heritage studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaf, W.R. A viewpoint on the reconstruction of destroyed UNESCO Cultural World Heritage Sites. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 23, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T.; Waterton, E. Critical Heritage Studies. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 529–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paddock, C.; Schofield, J. Authenticity and adaptation: The Mongol Ger as a contemporary heritage paradox. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, T. Beyond Eurocentrism? Heritage conservation and the politics of difference. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Uses of the past: Negotiating heritage in Xi’an. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trilling, L. Sincerity and Authenticity; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Chart). Approved by the Second International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments in Venice from 25 to 31 May 1964, adopted by ICOMOS in 1965. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (2013 Version, Article 86). Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide13-en.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2019).

- Byrne, D. Western hegemony in Archaeological Heritage Management. Hist. Anthropol. 1991, 5, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, D. Some Reflections on World Heritage. Area 1997, 29, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, N.; Graburn, N. Anthropological interventions in tourism studies. In The Sage Handbook of Tourism Studies; Jamal, T., Robinson, M., Eds.; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK, 2009; pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cornet, J. African Art and Authenticity. Afr. Arts 1975, 9, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. Staged authenticity: Arrangements of social space in tourist settings. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 79, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCannell, D. The Tourist; Schoken: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Boorstin, D.J. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America; Atheneum: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, E.M. Abraham Lincoln as authentic reproduction: A critique of postmodernism. Am. Anthropol. 1994, 96, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Authenticity and heritage conservation in China: Translation, interpretation, practices. In Authenticity in Architectural Heritage Conservation: Discourses, Opinions, Experiences in Europe, South and East Asia; Weiler, K., Gutschow, N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, G. Authenticity in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1995, 22, 781–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.P. Authenticity and sincerity in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, S.J.; Austin, A.G. A Study of Thinking; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T.A. Constructivist, Interpretivist Approaches to Human Inquiry. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, K.N., Lincoln, S.Y., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 118–137. [Google Scholar]

- Hobsbawm, E.; Ranger, T. The Invention of Tradition; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. Rethinking authenticity in tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 349–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. Performing heritage: Rethinking authenticity in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1495–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J. Conceptualising the subjective authenticity of intangible cultural heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscardo, G.M.; Pearce, P.L. Historic theme parks: An Australian experience in authenticity. Ann. Tour. Res. 1986, 13, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. China faces the challenge of World Heritage concept: Thoughts after the 28th World Heritage Convention. J. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2004, 20, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X. The heritage preservation system in ancient China. J. Southeast Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2012, 14, 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, J.R.; Yu, L. Heritage Management, Tourism, and Governance in China: Managing the Past to Serve the Present; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shambaugh, J.E.; Shambaugh, D.L. The Odyssey of China’s Imperial Art Treasures; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C.S. Five decades of cultural relics protection in the new China. Contemp. China Hist. Stud. 2002, 9, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.Q.; Chong, K.; Ap, J. An Analysis of Tourism Policy Development in Modern China. Tour. Manag. 1999, 20, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Q. Writing a modern Chinese architectural history: Liang Sicheng and Liang Qichao. J. Archit. Educ. 2002, 56, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. Losses and gains: A commentary on the impact of the University of Pennsylvania on Chinese academia in the 1920s. Archit. J. 2018, 599, 79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.C. A Pictorial History of Chinese Architecture: A Study of the Development of Its Structural System and the Evolution of Its Types; Fairbank, W., Ed.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, D. Reconstructing the relationships between architecture and nation: Rethinking the modern transitions of Chinese architecture. Architecture 2008, 132, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, D. Composition and elements—Origins of Beaux-Arts and Liang Sicheng’s expressions on “Grammer and Vocabularies” within Chinese modern architecture. Architecture 2009, 142, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bold, J.; Pickard, R. Reconstructing Europe: The need for guidelines. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2013, 4, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokilehto, J. Reconstruction in the World Heritage context. In Conservation—Reconstruction: Small Historic Centres Conservation in the Midst of Change; Crisan, R., Fiorani, D., Kealy, L., Musso, S.F., Eds.; European Association for Architectural Education: Hasselt, Belgium, 2018; pp. 513–524. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage practices in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. Reconstructing tradition: Heritage authentication and tourism-related commodification of the Ancient City of Pingyao. Sustainability 2018, 10, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, I.; Doorne, S. Dialectics of authentication: Performing ‘exotic otherness’ in a backpacker enclave of Dali, China. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2005, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoamo, M.T. Authenticating ethnic tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1197–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Cohen, S.A. Authentication: Hot and cool. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 1295–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.F. Authenticating Ethnic Tourism; Channel View Publications: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Su, X. Reconstruction of tradition: Modernity, tourism and Shaolin martial arts in the Shaolin scenic area, China. Int. J. Hist. Sport 2016, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.R. Faith in Heritage: Displacement, Development, and Religious Tourism in Contemporary China; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wall, G. Administrative arrangements and displacement compensation in top-down tourism planning—A case from Hainan Province, China. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X. ‘It is my home. I will die here’: Tourism development and the politics of place in Lijiang, China. Geografiska Annaler 2012, 94, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanxi Would Invest 10 Billion RMB to Reconstruct Datong Ancient City. Shanghai Morning Post. 30 August 2012. Available online: http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2012-08-30/073925065317.shtml (accessed on 5 August 2018).

- Kennedy, N.; Kingcome, N. Disneyfication of Cornwall—Developing a Poldark heritage complex. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 1998, 4, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackley, M. Potential futures for Robben Island: Shrine, museum or theme park? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2001, 7, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.M. A Hyperreal First-place: Portugal dos Pequenitos theme park and the narrative of origins. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 24, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Chan, C.; Marafa, L.M. Does authenticity exist in cultural theme parks? A case study of Millennium City Park in Henan, China. J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E. Authenticity and commoditization in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1988, 15, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjellman, S.M. Vinyl Leaves: Walt Disney World and America; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, T. The village as theme park: Mimesis and authenticity in Chinese tourism. In Translocal China: Linkages, Identities and the Reimaging of Space; Oakes, T., Schein, L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 166–192. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, T. Cultural strategies of development: Implications for village governance in China. Pac. Rev. 2006, 19, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S. Wei Shu; Zhonghua Press: Beijing, China, 1974; Volume 114, pp. 3039–3040. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z. Data Set of Shaolin Temple; Bibliography and Literature: Beijing, China, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y. Shaolin Fanggu; Baihua Literature and Art Publishing House: Tianjin, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Q.; Cui, H. The Impact of Emperor Wuzong of Tang Dynasty’s “Huichang Destroying Buddhism (huichang miefo)” on Shaolin Martial Arts. Sports World Sch. 2008, 2, 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Shaolin Temple Official Website for the Shaolin Kernel Compound. Available online: http://www.shaolin.org.cn/ (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Wen, Y. Introduction of History of Shaolin Temple. In Collected Papers of Research on Shaolin Culture; Shi, Y., Ed.; Religion and Culture Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y. The History of Chinese Martial Arts; People’s Sports Press: Beijing, China, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sofield, T.H.B.; Reid, L.M. Tourism development and cultural policies in China. Ann. Tour. Res. 1998, 25, 362–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Shaolin Temple in My Heart; Shanghi Literature Press: Shanghai, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. “Shaolin film fever” and the construction and development of Shaolin cultural industry. J. Henan Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2013, 53, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Henan Songshan Scenic Area Committee. Songshan Chronicles; Henan People Press: Zhengzhou, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dynon, N. ‘Four civilizations’ and the evolution of Post-Mao Chinese socialist ideology. China J. 2008, 60, 83–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J. We Should Protect the Cultural Heritages of City Well Just Like the Emotions That We Cherish Our Own Lives. Xinhua Net. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-01/06/c_1113897353.htm (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Zhang, Q. The Background of the Admission Ticket of the Shaolin Temple: The China Travel International Investment Hong Kong Limited Taking 51% Away? Available online: https://new.qq.com/cmsn/20140927/20140927010889 (accessed on 15 October 2018).

- Heritage Expert Wrote a Letter to Prime Minister after Knowing Shaolin Temple Would Be Listed. Outlook Weekly (Xinhua News). 27 June 2010. Available online: http://news.xinhuanet.com/politics/2010-06/27/c_12267900.htm (accessed on 28 August 2014).

- Zhou, X. Henan Songshan Shaolin Scenic Area Is Required to be Improved and Rectified. Sina News. 31 January 2012. Available online: http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2012-01-31/074923859133.shtml (accessed on 26 September 2018).

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Blaikie, N. Designing Social Research: The Logic of Anticipation; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK; Oxford, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, W.J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, B.; Ross, L. Research Methods: A Practical Guide for the Social Sciences; Pearson Education: Essex, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]