Abstract

Background: Pregnancy induces hormonal, immunologic, and vascular changes that profoundly affect dermatologic health. This systematic review aimed to assess the impact of pregnancy on dermatological disorders in terms of disease incidence, severity, maternal-fetal outcomes, and optimal management strategies. Methods: A systematic search was performed in PubMed, MEDLINE, and Web of Science databases, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies evaluating pregnant women with dermatological disorders, pregnancy-related dermatoses, and pre-existing morbidities, were included. The collaboratively extracted data included patient demographics, disease severity, treatment approaches, and pregnancy outcomes. Results: A total of 8490 pregnant cases with dermatologic changes and conditions caused by pregnancy were studied. The dermatological conditions were divided into physiological changes, pregnancy-related exacerbation of pre-existing skin conditions, and pregnancy-specific dermatoses. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and pemphigoid gestationis were associated with increased rates of adverse fetal outcomes in patients with specific dermatoses, including increased preterm birth and fetal distress rates. The atopic eruption of pregnancy and polymorphic eruption of pregnancy were highly relevant, but their effect on fetal health was minimal. The efficacy and safety of treatment modalities, including corticosteroids, antihistamines, and ursodeoxycholic acid, were variable. Conclusions: Pregnancy drastically affects dermatological health, but the nature of the impact depends on the condition. Optimal maternal and fetal outcomes rely on early diagnosis and individualized management strategies. More randomized controlled trials are required to develop standardized diagnostic and treatment guidelines to enhance the quality of dermatologic care during pregnancy.

1. Introduction

Pregnancy is a physiological state characterized by distinct immunological, hormonal, and vascular alterations that might affect dermatological health [1]. Up to 90% of pregnant women experience changes in their skin, ranging from benign physiological changes to exacerbations of pre-existing dermatological conditions and the appearance of pregnancy dermatoses [2]. The dermatological alterations are associated with fluctuations in estrogen, progesterone, and other hormones pertinent to pregnancy, as well as immune system modifications that promote fetal development [3].

Pregnancy dermatoses can be categorized into three primary groups: normal physiological skin alterations, worsening of pre-existing skin conditions due to pregnancy, and pregnancy-specific dermatoses [4]. Common physiological changes, typically reversing postpartum, include hyperpigmentation (melasma and linea nigra), and striae gravidarum [5]. Pre-existing dermatological diseases, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and autoimmune bullous illnesses, might be dramatically impacted. Pregnancy-specific dermatoses, including pemphigoid gestationis (PG), polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), atopic eruption of pregnancy (AEP), and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), exhibit distinct diagnostic and treatment challenges and might lead to detrimental maternal and fetal consequences [6].

The start timing, intensity, and progression of dermatological illnesses during pregnancy are influenced by various factors, including maternal age, parity, genetic susceptibility, and immunological tolerance mechanisms. Some conditions resolve spontaneously after delivery, while others necessitate tailored intervention to avert unnecessary complications [7]. The clinical management of dermatological diseases in pregnant individuals must be cautious, prioritizing optimal results for the mother and fetus, particularly in treatment selection, to minimize teratogenic risk [8].

This systematic review aimed to assess the influence of pregnancy on several dermatological conditions, including their incidence, severity, progression, and implications for mother and fetal health. Our objective was to evaluate the outcomes of dermatological disorders and to determine if pregnancy exacerbates, ameliorates, or has no meaningful impact on these conditions. Despite existing literature on skin alterations and their therapy during pregnancy, a consensus on the management of many dermatologic diseases during this period appears to be lacking. Advocates of early intervention emphasize the advantages of symptom management and problem prevention, but others propose a more cautious strategy due to the restricted treatment options deemed safe during pregnancy. This study aimed to provide evidence-based dermatological treatment recommendations to assist doctors in achieving an optimal balance between safety and efficacy for mothers and fetuses.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

Our systematic review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42025635819, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, accessed on 8 January 2025) and conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Appendix A and Appendix B) [9]. In PubMed, MEDLINE, and Web of Science databases without a time limit, a thorough electronic search using a predetermined search strategy developed by 2 authors (S.A. and A.A.) and approved by the remainder of the study team. For identifying relevant studies that acquired the effects of pregnancy on dermatological disorders, a comprehensive search of the PubMed database was performed using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms “Pregnancy Dermatoses”, “Gestational Skin Disorders”, or “Dermatology in Pregnancy” in combination with MeSH terms “Hormonal Influence”, “Pregnancy-Related Skin Changes”, or “Autoimmune Skin Disorders in Pregnancy” to identify research that examined the effects of pregnancy on dermatological disorders as well as “Complications” or “Maternal-Fetal Outcomes”. The references of the selected articles were checked to find any articles that might have been missed.

2.2. Study Selection

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Studies that evaluated the impact of pregnancy on dermatological disorders, including their severity, progression, and outcomes for both the mother and the fetus, were included in this systematic review. Studies assessing autoimmune dermatoses like pemphigus vulgaris, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and PG were considered. Additionally, there are immune-mediated chronic inflammatory skin disorders such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis. Additionally, it covered immune dysregulation-related pregnancy-specific diseases such as ICP and PEP, which entail hormonal and inflammatory interactions that may impair immunological function. RCTs, quasi-experimental, cohort, case-control, systematic review, case report, and observational studies published in English were all included in this study. Studies from reputable sources (PubMed, MEDLINE, and Web of Science) as well as peer-reviewed publications were included.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

We excluded studies that did not evaluate the effect of pregnancy on dermatological disorders, including studies focusing on dermatological conditions unrelated to pregnancy, animal investigations, in vitro assays, and research published in non-English languages. Studies with incomplete or missing data on key variables necessary for analysis were also excluded.

2.2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

The remaining results were imported into Rayyan [(https://www.rayyan.ai/), accessed 8 November 2024] by five authors (M.F.A., L.O.A., M.A.A. and A.K.) and screened by title and abstracts for relevance to the aims of the study [10]. All the studies were checked at least by two authors to avoid discrepancy and bias. After this initial screening, three authors (K.A.A., A.A., and A.M.K.) conducted a full-text review of publications that were part of the first screening to make a final decision on inclusion or exclusion according to the eligibility criteria adopted. Any discrepancies during selection were resolved through structured discussion and consensus meetings that included an additional reviewer (S.A.) and senior researchers, as required.

An Excel sheet was done by A.A., A.M.K., and S.A. to extract data systematically on the following study characteristics title, author name, country, year of publication, journal name, study design, level of evidence, sample size, reported dermatological complications, maternal-fetal outcomes, disease severity, and management strategies.

2.2.4. Quality Assessment and Bias Evaluation

The included studies’ quality of evidence and risk of bias were evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach [11]. This comprehensive assessment was used to determine the degree of evidence in all research, resulting in an overall quality score that showed a risk of bias. Both prospective and retrospective cohort studies were evaluated for bias using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Appendix C) [12]. The updated Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2; Appendix E) was used to assess the bias risk of RCTs [13]. The MINORS tool (Appendix D) was used to evaluate nonrandomized studies [14]. These assessments increase the credibility of the results presented by educating the reader about the caliber of the included studies and possible sources of bias.

2.3. Data Synthesis

Due to high inconsistency in data formats and high heterogeneity, a meta-analysis was not feasible; this substantially inhibited the ability to synthesize the findings and arrive at firm and concrete conclusions. This heterogeneity was due to several factors, including differences in study design (e.g., RCTs, cohort studies, and observational studies), as well as differences in methodologies and tools to assess outcomes. Differences in patient populations (e.g., differences in gestational age, differences in underlying dermatological conditions, differences in baseline characteristics, etc.) further contributed to study heterogeneity. In addition, outcome measures varied widely, with varied primary endpoints reported across studies, including symptom severity, complication rates, treatment response, and recurrence. Differences in the definition and reporting of clinical outcomes prevented direct comparisons between studies. The treatment modalities used also varied substantially, from topical therapies to systemic treatments with varied dosing regimens and follow-up timelines that made it difficult to assess the efficacy of varied treatments in studies.

Such methodological and clinical differences precluded statistical pooling and limited the generalizability of findings. So, although some individual studies offered useful insights, the weight of the evidence overall was compromised. The findings highlight the significant heterogeneity between studies and that future research should utilize standardized study designs, standardized outcome measures, and harmonized reporting standards, which, in combination, would improve comparability and ensure that clinical decisions regarding the management of dermatological disorders in pregnancy are evidence-based.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

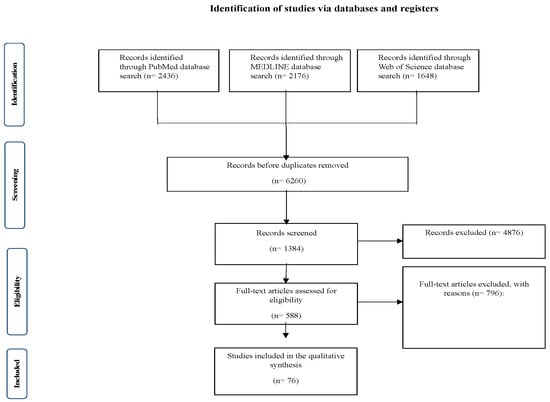

In total, the search identified 6260 unique records from PubMed (n = 2436), MEDLINE (n = 2176), and Web of Science (n = 1648). After the exclusion of field drifts (duplicates and irrelevant records), 1348 studies were screened. After a full-text evaluation, 76 studies stained the inclusion criteria for this systematic review of pregnancy-related dermatological disorders. The studies included in this systematic review were RCTs, cohort studies, case-control studies and case reports. The majority were observational (cohort and case-control) followed by RCTs. Among the studies, there was diversity in geography (North America, Europe, Asia, and Africa), though there was a lack of studies conducted in low-income regions. This introduces concerns about generalizability, as ethnicity-specific predisposition, access to healthcare, and environmental factors may affect the prevalence, severity, and management of disease. The age of the pregnant women ranges across the included studies from 18 to 45 years, covering adolescents, reproductive-age women, and those with advanced maternal age.

Meta-analysis according to Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (MOOSE) was not performed given the heterogeneity of study designs and outcome measures, however, the systematic review was structured on PRISMA guidelines for transparent reporting of review findings. The PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1 summarizes the study selection process. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics per study, including the sample size, country of origin, and the level of evidence.

Figure 1.

The phases of the study’s selection procedure in a comprehensive PRISMA chart utilized for the systematic review.

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of studies investigating the effect of pregnancy on dermatological disorders.

3.2. Dermatological Disorders in Pregnancy

The included studies described pregnancy-related dermatoses, classified as pregnancy-specific dermatoses [37], which are PG [38], ICP [39], AEP [40,41], PEP [42], and pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (PPP) [43,44]. And pre-existing dermatological conditions that may worsen in pregnancy are AD [45], psoriasis [46], and lupus erythematosus (LE) [47].

3.2.1. Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy

PEP is one of the most common pregnancy-specific dermatoses, characteristically occurring in third trimester and commoner in primigravida [48]. Intense pruritus, urticarial papules, and plaques in abdominal striae were the hallmark symptoms in the studies [49]. PEP is not fetotoxic, but severe pruritus can lead to sleep disturbances and emotional distress requiring symptomatic treatment with topical corticosteroids, antihistamines, and emollients [50,51] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient-Reported Outcomes and Complications of Pregnancy-Related Dermatological Disorders.

3.2.2. Atopic Dermatitis and Biologic Therapy in Pregnancy

AD typically exacerbates in pregnancy because of hormonal changes and immune modulation towards a Th2 profile. In severe cases systemic therapy may be needed, including biologic agents such as dupilumab. However, the evidence for the safety of biologics in pregnancy is limited. Table 3 summarizes the risk factors for worsening AD, including high IgE levels, genetic predisposition, and pre-existing atopy.

Table 3.

Association Between Pregnancy-Related Dermatological Disorders and Risk Factors.

3.2.3. Lupus Erythematosus and Pregnancy

LE creates distinct challenges in pregnancy because flares can cause severe maternal and fetal morbidity. The study concluded that SLE is linked with an elevated risk of preterm birth, preeclampsia, and neonatal lupus syndrome. Disease activity is associated with estrogen-driven immune dysregulation, and some cases worsen during the third trimester. Systemic corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine continue to be the principal agents, but immunosuppression may be needed for refractory cases.

3.3. Maternal and Fetal Complications

Maternal and fetal complications related to pregnancy dermatoses are summarized in Table 2. PG is associated with small-for-gestational-age infants and preterm delivery. ICP is strongly linked to stillbirth and fetal distress, leading to early delivery in severe instances. AEP and PEP causes maternal discomfort without direct fetal risks.

Dermatological disorders in high-risk pregnancies (multiple gestations, advanced maternal age, etc.) were associated with more cutaneous complications and greater maternal-fetal morbidity.

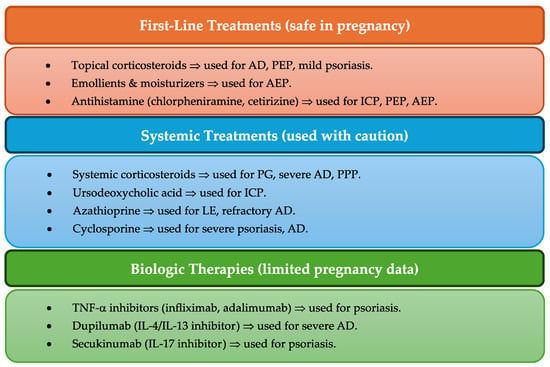

3.4. Treatment Approaches and Variability in Effectiveness

There were significant differences in treatment strategies between studies (Table 2 and Figure 2), and systemic corticosteroids, antihistamines, and UDCA were the most used therapies. However, the effectiveness and safety profiles varied based on differences in the type of study (RCTs versus observational studies), dosage, and duration of corticosteroid therapy, when treatment is initiated gestational age and mapping comorbid conditions that affect treatment response.

Figure 2.

Overview of treatment approaches for pregnancy-related dermatological disorders.

Systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone, methylprednisolone) were also frequently used for PG and pustular psoriasis of pregnancy but were associated with gestational diabetes, hypertension, and intrauterine growth restriction in some studies. Despite those risks, they are the first-line treatment for severe cases.

As for ICP, UDCA is generally recommended for its ability to reduce bile acid levels to help alleviate maternal pruritus. Studies produced divergent findings regarding its safety in the prevention of stillbirth, leading to the argument of performing more RCTs to adjust treatment measures.

Limited data exist regarding biologic therapies (e.g., TNF-α inhibitors, dupilumab) and immunosuppressants (e.g., azathioprine, cyclosporine) during pregnancy. Patients presenting with more severe, refractory AD, psoriasis, or lupus need careful consideration in terms of the risk/benefit ratio, according to current clinical evidence.

4. Discussion

This systematic review focused on pregnancy and dermatological diseases, emphasizing that physiological, hormonal, and immunological changes modify both pre-existing and pregnancy-specific dermatoses. This is because pregnancy causes benign physiological changes (e.g., melasma, linea nigra), or it exacerbate pre-existing dermatological conditions, and therefore requires individual clinical management.

Our study confirmed the existing data that pigmentation changes (melasma and linea nigra) are associated with major physiological skin changes during pregnancy, with a prevalence of up to 90% [61]. These alterations are primarily due to higher levels of estrogen, progesterone, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone, leading to increased melanogenesis and altered skin pigmentation [62]. Although these changes are mostly benign, they can be cosmetically bothersome to patients who require reassurance and management strategies for postpartum care. Among pregnancy-specific dermatoses, AEP is the most common chronic disorder, accounting for 48.8% of cases, most occurring in the first or second trimester, followed by PEP, PG, and ICP [63]. The accumulation of bile acids in ICP leads to significant fetal risks, such as premature birth, fetal distress, and stillbirth. This malady presented mainly with pruritus [64]. These data underscore the importance of careful surveillance and early treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid to reduce the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes [65].

PV is an autoimmune-mediated blistering disorder that increases the risk of fetal growth restriction and preterm birth [66]. Corticosteroids are effective in controlling autoimmune-mediated blistering, but studies have suggested that long-term systemic corticosteroid exposure possibly increases the risk of gestational diabetes, hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm birth [67]. Despite these issues, systemic corticosteroids are still the first-line therapy due to their efficacy for controlling inflammation and preventing disease progression. Nonetheless, clearly designed RCTs are required to assess its long-term effects on maternal health, fetal entailment, and the risk-benefit balance of various dosages and treatment periods [68]. PEP is a benign yet troublesome condition that occurs later in pregnancy, primarily in primigravida, and is treated with topical corticosteroids, antihistamines, and emollients [69].

The role of pre-existing dermatological conditions in pregnancy was another area of exploration. Our overview suggests that pregnancy induced Th2 dominance may worsen AD by prompting severe flares. Topical corticosteroids and topical emollients are commonly used but for severe cases systemic therapies, including biologics like dupilumab, may be required. Nonetheless, the lack of data on biologic safety in pregnancy highlights the need for additional study [70]. It also suggests that psoriasis classically improves in pregnancy, possibly due to immune modulation that favors Th2 cytokines, while SLE and pemphigus are exacerbated, conferring an increased risk of fetal complications, preterm delivery and maternal disease flares. LE is associated with higher rates of maternal and fetal morbidity, such as preeclampsia and neonatal lupus syndrome. Management involves hydroxychloroquine, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants with careful monitoring [71].

Only a few studies dealt with the risk of malignant diseases during pregnancy, but some limited evidence suggested an elevated melanomas incidence. Hormonal changes may also affect melanoma progression, the precise relationship is still unclear. More studies are needed to assess pregnancy-associated malignancies regarding its effect on maternal-fetal outcomes [72].

Treatment options for pregnancy-associated dermatological disorders were heterogeneous among the studies, with systemic corticosteroids, antihistamines and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) found to be the most prescribed treatments. However, their efficacy and safety profiles remain issues of debate [73]. Corticosteroids are effective agents for PG and pustular psoriasis of pregnancy, with potential for maternal metabolic complications and fetal growth restriction [74]. The use of UDCA is neither supported nor questioned in preventing stillbirth in ICP, necessitating larger and well-controlled RCTs [75]. Although biologics and immunosuppressants (TNF-α inhibitors, dupilumab, etc.) may be required for AD and/or psoriasis with significant severity, their long-term fetal safety is not well understood, and more investigation is needed for this population [76]. Standardized treatment protocols were not documented across studies which present the need for some multicenter RCTs, at least at a regional level, to establish baseline management guidelines that would allow dermatologists to make evidence-based clinical decisions when managing dermatological disorders during pregnancy.

Limitations

The studies included had different sample sizes, study designs, and diagnostic criteria, which made the results difficult to compare. Many did not have standardized measures of outcomes, so assessing disease severity, progression, and treatment response was challenging. Many of the studies were performed in specialized dermatology or obstetric referral hospitals, which may have led to an overestimation of the prevalence of severe dermatological diseases and an underestimation of milder physiologic changes. Most of the studies were conducted in North America, Europe, and Asia, with few studies from low-resource contexts, which may limit the generalizability of study findings.

Moreover, many of the studies failed to control for pre-existing dermatologic conditions, making it difficult to isolate pregnancy as the only modifying factor in disease progress. Given the heterogeneity in the corticosteroid dosing regimens and in the use of UDCA, direct comparisons of therapeutic effectiveness were not possible. However, there is limited information concerning the long-term outcomes in mothers and neonates, specifically regarding the recurrence of pregnancy-associated dermatological disorders in subsequent pregnancies.

To fill these gaps, multicenter studies in the future should have systemic diagnostic criteria and long-term follow-up. Include factors related to socioeconomic and health care access will facilitate assessment of dermatological care gaps during pregnancy.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlighted the importance of early recognition and management of pregnancy-related dermatological diseases, as these might play a significant role in avoiding maternal and fetal adverse events. It also highlighted the need for an individualized management approach based on gestational age, and comorbidities to provide the best care for mother and child. Topical corticosteroids, antihistamines, and ursodeoxycholic acid continue to represent the mainstay treatment, however, more studies are warranted to evaluate the safety of systemic immunosuppressants and other promising treatments to establish evidence-based guidelines.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: M.F.A., L.O.A.H., M.A.A., A.A. and A.K.; acquisition: H.I.W., K.A.A., A.N.A.J., A.M.K. and S.A.; analysis of data: M.F.A., L.O.A.H., M.A.A., A.A. and A.K.; drafting of the manuscript: H.I.W., K.A.A., A.N.A.J., A.M.K. and S.A.; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: M.F.A., L.O.A.H., M.A.A., A.A., A.K., H.I.W., K.A.A., A.N.A.J., A.M.K. and S.A.; supervision: S.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No outside funding was obtained for this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the recommended Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) standards and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42025635819). Because this study did not directly involve any human or animal subjects and instead involved the analysis of previously published data, ethical review and approval were waived.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable due to the nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable due to the nature of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AEP | Atopic eruption of pregnancy |

| BP180 | Bullous Pemphigoid 180 |

| GRADE | Grading or Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| ICP | Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| PEP | Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy |

| PG | Pemphigoid gestationis |

| PPP | Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PUPPP | Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trials |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| AD | Atopic dermatitis |

| MOOSE | Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology |

| LE | Lupus erythematosus |

| UDCA | Ursodeoxycholic acid |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Systematic review protocol and support template.

Table A1.

Systematic review protocol and support template.

| Title of the Systematic Review | The Effect of Pregnancy on Dermatological Disorders; A Systematic Review |

| |

| Pregnancy is a physiological state characterized by distinct immunological, hormonal, and vascular alterations that might affect dermatological health [1]. Up to 90% of pregnant women experience changes in their skin, ranging from benign physiological changes to exacerbations of pre-existing dermatological conditions and the appearance of pregnancy dermatoses [2]. The dermatological alterations are associated with fluctuations in estrogen, progesterone, and other hormones pertinent to pregnancy, as well as immune system modifications that promote fetal development [3]. Pregnancy dermatoses can be categorized into three primary groups. The first is normal physiological skin alterations; the second is the worsening of pre-existing skin conditions due to pregnancy; and the third is pregnancy-specific dermatoses [4]. Common physiological changes, typically returning postpartum, encompass hyperpigmentation (melasma and linea nigra), striae gravidarum, and vascular adaptations [5]. Pre-existing dermatological problems, including atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, and autoimmune bullous illnesses, might be dramatically impacted. Pregnancy-specific dermatoses, including pemphigoid gestationis (PG), polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PEP), atopic eruption of pregnancy (AEP) and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), exhibit distinct di-agnostic and treatment challenges and may lead to detrimental maternal and fetal consequences [6]. The timing of start, intensity, and progression of dermatological illnesses during pregnancy are influenced by various factors, including maternal age, parity, genetic susceptibility, and immunological tolerance mechanisms. Some conditions resolve spontaneously after delivery, while others necessitate tailored intervention to avert unnecessary problems [7]. The clinical management of dermatological diseases in pregnant individuals must be cautious, prioritizing optimal results for both the mother and fetus, particularly in the selection of treatment choices to minimize teratogenic risk [8]. | |

| |

| This systematic review investigates pregnancy-associated alterations that affect the course of cutaneous diseases and their treatment and then discusses these changes in terms of the safety of both the mother and the fetus. We aim to guide the clinician with evidence-based recommendations on the best diagnosis and management of skin diseases in pregnancy, to optimize maternal health, reduce morbidity, and provide the best quality of life for patients. | |

| |

| |

| |

| Population, or participants and condition of interest | This review will examine pregnant patients with dermatological diseases in various healthcare settings and in patients of various ages and backgrounds. The condition of interest for this systematic review is the impact of pregnancy on multiple disease states and their management as well as the influence of physiologic changes of pregnancy and disease therapy on maternal-fetal outcomes. |

| Interventions or exposures |

|

| Comparisons or control groups | The stanard care group consists of pregnant individuals having standard care for managing dermatological conditions during pregnancy. This may include observation, symptomatic management, or conservative treatment approaches considered safe during pregnancy. The outcomes of this group will be compared to those receiving targeted interventions or treatment adjustments based on pregnancy-related changes, allowing for an evaluation of disease progression, maternal symptom relief, and fetal outcomes. |

| Outcomes of interest | Symptom improvement rates, complication rates associated with pregnancy-related physiological changes, effectiveness and safety of treatments during pregnancy, disease progression or remission patterns, maternal quality of life, and fetal outcomes (e.g., birth weight, gestational age at delivery) in patients with dermatological conditions during pregnancy. |

| Setting |

|

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

| |

| Electronic databases |

|

| Keywords | (Dermatological disorders OR Pregnancy-related skin conditions OR Maternal dermatology OR Pregnancy outcomes OR Hormonal changes OR Autoimmune skin diseases OR Treatment safety during pregnancy) |

| |

| Quality assessment tools or checklists used with references or URLs | In addition to using the STROBE tool to find pertinent material and methodology in each of the papers to be examined, the protocol will specify the approach taken in the literature critique/appraisal. |

| Narrative synthesis details of what and how synthesis will be performed | Alongside any meta-analysis, narrative synthesis will be conducted using a framework that comprises four components: producing a preliminary synthesis of the findings of included studies, investigating relationships within and between studies, evaluating the robustness of the synthesis, and developing a theory of how the intervention works, why, and for whom. |

| Meta-analysis details of what and how analysis and testing will be performed. If no meta-analysis is to be conducted, please give reason. | Although there are plans for a meta-analysis, it will only be come clear after the systematic review what data will be extracted and put to public domain. We need to think about how we will study heterogeneity. |

| Grading evidence system used, if any, such as GRADE | GRADE will be used for the evidence assessment. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Table A2.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

| Section and Topic | Item # | Checklist Item | Location Where Item Is Reported |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a systematic review. | Page 1; lines 2 to 3 |

| Abstract | |||

| Abstract | 2 | See the PRISMA 2020 for the abstracts checklist. | Page 1; lines 14 to 35 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of existing knowledge. | Page 2; lines 41 to 65 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the objective(s) or question(s) the review addresses. | Page 2; lines 66 to 77 |

| Methods | |||

| Eligibility criteria | 5 | Specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review and how studies were grouped for the syntheses. | Page 3; lines 95 to 108 |

| Information sources | 6 | Specify all databases, registers, websites, organizations, reference lists, and other sources searched or consulted to identify studies. Specify the date when each source was last searched or consulted. | Page 3; lines 81 to 92 |

| Search strategy | 7 | Present the full search strategies for all databases, registers, and websites, including any filters and limits used. | Page 3; lines 81 to 92 |

| Selection process | 8 | Specify the methods used to decide whether a study met the inclusion criteria of the review, including how many reviewers screened each record and each report retrieved, whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3; lines 95 to 102 |

| Data collection process | 9 | Specify the methods used to collect data from reports, including how many reviewers collected data from each report, whether they worked independently, any processes for obtaining or confirming data from study investigators, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3; lines 109 to 119 |

| Data items | 10a | List and define all outcomes for which data were sought. Specify whether all results that were compatible with each outcome domain in each study were sought (e.g., for all measures, time points, analyses), and, if not, the methods used to decide which results to collect. | ND |

| 10b | List and define all other variables for which data were sought (e.g., participant and intervention characteristics, funding sources). Describe any assumptions made about any missing or unclear information. | ND | |

| Study risk of bias assessment | 11 | Specify the methods used to assess the risk of bias in the included studies, including details of the tool(s) used, how many reviewers assessed each study, and whether they worked independently, and, if applicable, details of automation tools used in the process. | Page 3 and 4; lines 120 to 130 |

| Effect measures | 12 | Specify for each outcome the effect measure(s) (e.g., risk ratio, mean difference) used in the synthesis or presentation of the results. | ND |

| Synthesis methods | 13a | Describe the processes used to decide which studies were eligible for each synthesis (e.g., tabulating the study intervention characteristics and comparing them against the planned groups for each synthesis (item #5)). | Page 4; lines 132 to 142 |

| 13b | Describe any methods required to prepare the data for presentation or synthesis, such as handling of missing summary statistics, or data conversions. | Page 4; lines 132 to 142 | |

| 13c | Describe any methods used to tabulate or visually display results of individual studies and syntheses. | Page 4; lines 132 to 142 | |

| 13d | Describe any methods used to synthesize results and provide a rationale for the choice(s). If meta-analysis was performed, describe the model(s), the method(s) to identify the presence and extent of statistical heterogeneity, and software package(s) used. | ND | |

| 13e | Describe any methods used to explore possible causes of heterogeneity among study results (e.g., subgroup analysis, meta-regression). | ND | |

| 13f | Describe any sensitivity analyses conducted to assess robustness of the synthesized results. | ND | |

| Reporting bias assessment | 14 | Describe any methods used to assess the risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis (arising from reporting biases). | Page 3 and 4; lines 120 to 130 |

| Certainty assessment | 15 | Describe any methods used to assess certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for an outcome. | ND |

| Results | |||

| Study selection | 16a | Describe the results of the search and selection process, from the number of records identified in the search to the number of studies included in the review, ideally using a flow diagram. | Page 4; lines 144 to 157 |

| 16b | Cite studies that might appear to meet the inclusion criteria, but which were excluded, and explain why they were excluded. | Page 4; lines 144 to 157 | |

| Study characteristics | 17 | Cite each included study and present their characteristics. | Page 6 and 7; lines 163 to 165 |

| Risk of bias in studies | 18 | Present assessments of the risk of bias for each included study. | Page 3 and 4; lines 120 to 130 |

| Results of individual studies | 19 | For all outcomes, present, for each study (a) summary statistics for each group (where appropriate) and (b) an effect estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval), ideally using structured tables or plots. | Page 6 and 7; lines 163 to 165 |

| Results of syntheses | 20a | For each synthesis, briefly summarize the characteristics and risk of bias among contributing studies. | Page 8 till 10; lines 166 to 217 |

| 20b | Present results of all statistical syntheses conducted. If meta-analysis was performed, present each summary estimate and its precision (e.g., confidence/credible interval) and measures of statistical heterogeneity. If comparing groups, describe the direction of the effect. | ND | |

| 20c | Present results of all investigations of possible causes of heterogeneity among study results. | ND | |

| 20d | Present results of all sensitivity analyses conducted to assess the robustness of the synthesized results. | ND | |

| Reporting biases | 21 | Present assessments of risk of bias due to missing results (arising from reporting biases) for each synthesis assessed. | ND |

| Certainty of evidence | 22 | Present assessments of certainty (or confidence) in the body of evidence for each outcome assessed. | ND |

| Discussion | |||

| Discussion | 23a | Provide a general interpretation of the results in the context of other evidence. | Page 11; lines 219 to 266 |

| 23b | Discuss any limitations of the evidence included in the review. | Page 12; lines 267 to 299 | |

| 23c | Discuss any limitations of the review processes used. | Page 12; lines 267 to 299 | |

| 23d | Discuss implications of the results for practice, policy, and future research. | Page 12; lines 291 to 308 | |

| Other information | |||

| Registration and protocol | 24a | Provide registration information for the review, including register name and registration number, or state that the review was not registered. | Page 3; lines 81 to 84 |

| 24b | Indicate where the review protocol can be accessed, or state that a protocol was not prepared. | Page 3; lines 81 to 84 | |

| 24c | Describe and explain any amendments to information provided at registration or in the protocol. | Page 3; lines 81 to 84 | |

| Support | 25 | Describe sources of financial or non-financial support for the review, and the role of the funders or sponsors in the review. | Page 13; line 316 |

| Competing interests | 26 | Declare any competing interests of review authors. | Page 13; line 325 |

| Availability of data, code and other materials | 27 | Report which of the following are publicly available and where they can be found; template data collection forms; data extracted from included studies; data used for all analyses; analytic code; any other materials used in the review. | ND |

Appendix C

Table A3.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for the included cohort prospective and retrospective studies.

Table A3.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for the included cohort prospective and retrospective studies.

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Quality Score | Risk of Bias (0–3: High; 4–6: Moderate; 7–9: Low) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | ||

| Panicker, et al. 2016 [1] | (B) somewhat representative of the average cohort | (B) drawn from the same community | * | * | One factor controlled | * | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (6) | Moderate Risk |

| Vora, et al. 2014 [2] | (A) Truly representative of the average cohort | (A) Derived from the same population | ** | ** | Two factors controlled | ** | Yes | ** | Good Quality Study (8) | Low Risk |

| Gupta, et al. 2024 [3] | (B) Somewhat representative of the average cohort | (B) Drawn from the same community | * | * | No comparability | * | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (5) | Moderate Risk |

| Vk, et al. 1988 [4] | (C) Selected group of users | (C) No description of the non-exposed cohort | * | * | No comparability | * | No | * | Poor Quality Study (4) | Moderate Risk |

| Kepley, et al. 2019 [5] | (A) Truly representative of the average cohort | (A) Derived from the same population | ** | ** | Two factors controlled | ** | Yes | ** | Good Quality Study (8) | Low Risk |

| Sävervall, et al. 2015 [6] | (B) Somewhat representative of the average cohort | (B) Drawn from the same community | * | * | One factor controlled | * | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (6) | Moderate Risk |

| Abu-Raya, et al. 2020 [7] | (A) Truly representative of the average cohort | (A) Derived from the same population | ** | ** | One factor controlled | * | Yes | ** | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Pope, et al. 2022 [8] | (A) Truly representative of the average cohort | (A) Derived from the same population | ** | ** | One factor controlled | ** | Yes | ** | Good Quality Study (8) | Low Risk |

| Thappa, et al. 2007 [15] | (B) Somewhat representative of the average cohort | (B) Drawn from the same community | * | * | One factor controlled | * | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (6) | Moderate Risk |

| Aronson, et al. 1998 [23] | (A) Truly representative of the average cohort | (A) Derived from the same population | ** | ** | One factor controlled | ** | Yes | ** | Good Quality Study (8) | Low Risk |

Selection: Q1. Representativeness of the exposure cohort? Q2. Selection of the non-exposure cohort? Q3. Ascertainment of exposure? Q4. Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study? Comparability: Q5. Comparability of cohort based on the design or analysis? Outcome: Q6. Assessment of outcome? Q7. Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? Q8. Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts? *: Means the corresponding quality component or criterion is partially met; **: means the corresponding quality component or criterion is fully met.

Appendix D

Table A4.

Bias of the included cross-sectional studies evaluated according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

Table A4.

Bias of the included cross-sectional studies evaluated according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Quality Score | Risk of Bias (0–3: High; 4–6: Moderate; 7–9: Low) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | |||

| Muzaffar, et al. 1998 [33] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Fernandes, et al. 2015 [34] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Rathore, et al. 2011 [35] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

Selection: Q1. Representativeness of the exposure cohort? Q2. Sample size? Q3. Ascertainment of exposure? Q4. Response rate? Q5. Ascertainment of the screening/surveillance tool? Comparability: Q5. The potential confounders were investigated by subgroup analysis or multivariable analysis? Outcome: Q6. Assessment of outcome? Q7. Statistical test? *: Means the corresponding quality component or criterion is partially met.

Appendix E

Table A5.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).

Table A5.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).

| Articles | Bias Arising From the Randomization Process | Bias Due to Deviations from Intended Interventions | Blinding of Participants and Personnal | Bias Due to Missing Outcome Data | Bias in Measurement of the Outcome | Bias in Selection of the Reported Result | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siemens, et al. 2016 [47] | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Kondrackiene, et al. 2005 [52] | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Chappell, et al. 2020 [65] | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

References

- Panicker, V.V.; Riyaz, N.; Balachandran, P. A clinical study of cutaneous changes in pregnancy. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2016, 7, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vora, R.V.; Gupta, R.; Mehta, M.J.; Chaudhari, A.H.; Pilani, A.P.; Patel, N. Pregnancy and skin. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2014, 3, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.N.; Madke, B.; Ganjre, S.; Jawade, S.; Kondalkar, A. Cutaneous changes during pregnancy: A comprehensive review. Cureus 2024, 16, e69986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vk, S.; Wf, S. Dermatoses of pregnancy. Am. Fam. Physician 1988, 37, 131–138. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3276095 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Kepley, J.M.; Bates, K.; Mohiuddin, S.S. Physiology, Maternal Changes; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2019; Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/MED/30969588 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Sävervall, C.; Sand, F.L.; Thomsen, S.F. Dermatological Diseases Associated with Pregnancy: Pemphigoid Gestationis, Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy, Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy, and Atopic Eruption of Pregnancy. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2015, 2015, 979635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abu-Raya, B.; Michalski, C.; Sadarangani, M.; Lavoie, P.M. Maternal immunological adaptation during normal pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 575197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, E.M.; Laageide, L.; Beck, L.A. Management of allergic skin disorders in pregnancy. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2022, 43, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozek, J.L.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bowen, J.M.; Bucher, J.; Chiu, W.A.; Cronin, M.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falavigna, M.; Guyatt, G.H.; et al. GRADE Guidelines 30: The GRADE approach to assessing the certainty of modeled evidence—An overview in the context of health decision-making. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 129, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thappa, D.M.; Kumari, R.; Jaisankar, T. A clinical study of skin changes in pregnancy. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2007, 73, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczęch, J.; Wiatrowski, A.; Hirnle, L.; Reich, A. Prevalence and relevance of pruritus in pregnancy. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 4238139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.H.; Sterns, E.E.; Kopald, K.H.; Nizze, J.A.; Morton, D.L. Prognostic significance of pregnancy in stage I melanoma. Arch. Surg. 1989, 124, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.F.; Santi, C.G.; Maruta, C.W.; Aoki, V. Pemphigoid gestationis: Clinical and laboratory evaluation. Clinics 2009, 64, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglie, R.; Quintarelli, L.; Verdelli, A.; Fabbri, P.; Antiga, E.; Caproni, M. Specific dermatoses of pregnancy other than pemphigoid gestationis. Ital. J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2019, 154, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushkell, L.L.; Jordon, R.E.; Goltz, R.W. Herpes gestationis. Arch. Dermatol. 1974, 110, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercovitch, L.; Bogaars, H.A.; Murray, D.O. Pustular herpes gestationis. Arch. Dermatol. 1983, 119, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaliwal, R.G.; Biradar, A.; Konin, A.; Reddy, S.T. Prurigo of pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2023, 16, e255351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, I.K.; Bond, S.; Fiedler, V.C.; Vomvouras, S.; Gruber, D.; Ruiz, C. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: Clinical and immunopathologic observations in 57 patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1998, 39, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancey, K.B.; Hall, R.P.; Lawley, T.J. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: Clinical experience in twenty-five patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1984, 10, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, C.; Al-Fares, S.; Vaughan-Jones, S.; Müllegger, R.; Kerl, H.; Black, M. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: Clinicopathology and potential trigger factors in 181 patients. Br. J. Dermatol. 2005, 154, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroumpouzos, G.; Cohen, L.M. Pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 43, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, D. Specific pruritic diseases of pregnancy. A prospective study of 3192 pregnant women. Arch. Dermatol. 1994, 130, 734–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambros-Rudolph, C.M.; Müllegger, R.R.; Vaughan-Jones, S.A.; Kerl, H.; Black, M.M. The specific dermatoses of pregnancy revisited and reclassified: Results of a retrospective two-center study on 505 pregnant patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 54, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, L.O.; Tinajero, Á.S.; Orozco, J.A.M.; Vargas, E.B.; De la Merced, A.D.; Santillán, D.P.R.; Cueva, A.I.D.; Peña, N.A. A 34-Year-Old Woman with a Diamniotic Dichorionic Twin Pregnancy Presenting with an Erythematous and Papular Skin Rash Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Am. J. Case Rep. 2021, 22, e929489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehedintu, C.; Isopescu, F.; Ionescu, O.-M.; Petca, A.; Bratila, E.; Cirstoiu, M.M.; Carp-Veliscu, A.; Frincu, F. Diagnostic Pitfall in Atypical Febrile Presentation in a Patient with a Pregnancy-Specific Dermatosis—Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Chang, J.-M. Nodular vulvar lesions. JAMA Dermatol. 2024, 160, 891–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannambal, K. A Screening study on dermatoses in pregnancy. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, WC01–WC05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muzaffar, F.; Hussain, I.; Fcps; Haroon, T.S. Physiologic skin changes during pregnancy: A study of 140 cases. Int. J. Dermatol. 1998, 37, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, L.B.; Amaral, W.N.D. Clinical study of skin changes in low and high risk pregnant women. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2015, 90, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rathore, S.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, V. Pattern and prevalence of physiological cutaneous changes in pregnancy: A study of 2000 antenatal women. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2011, 77, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.C.; Ellis, C.N. Physiologic skin changes in pregnancy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1984, 10, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, H.; Melamed, N.; Koren, G. Pruritus in pregnancy: Treatment of dermatoses unique to pregnancy. Can. Fam. Physician 2013, 59, 1290–1294. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24336540 (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Deshmukh, H.; Way, S.S. Immunological basis for recurrent fetal loss and pregnancy complications. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2019, 14, 185–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.A.; El Sharkawy, R.E.E.-D.; Rasheed, S. Cutaneous changes during pregnancy. Sohag Med. J. 2018, 22, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handel, A.C.; Miot, L.D.B.; Miot, H.A. Melasma: A clinical and epidemiological review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2014, 89, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, G.; Derlino, F.; Berti, E.; Marzano, A.V. Treatment of autoimmune bullous diseases during pregnancy and lactation: A review focusing on pemphigus and pemphigoid Gestationis. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 583354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estin, M.L.; Campbell, A.I.; Watkins, V.Y.; Dotters-Katz, S.K.; Brady, C.W.; Federspiel, J.J. Risk of stillbirth in United States patients with diagnosed intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 229, 453.e1–453.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correa-De-Araujo, R.; Yoon, S.S. Clinical outcomes in high-risk pregnancies due to advanced maternal age. J. Women’s Heal. 2021, 30, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.; Chen, K.K.; Kroumpouzos, G. Skin disease in pregnancy: The approach of the obstetric medicine physician. Clin. Dermatol. 2016, 34, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glantz, A.; Marschall, H.-U.; Mattsson, L. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology 2004, 40, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, J.; Reyes, H.; Ribalta, J.; Iglesias, J.; Gonazalez, M.C.; Hernandez, I.; Alvarez, C.; Molina, C.; Danitz, A.M. Effects of Ursodeoxycholic Acid in Patients With Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy. Hepatology 1992, 15, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, W.; Xander, C.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Buroh, S.; Antes, G.; Schwarzer, G.; Becker, G. Pharmacological interventions for pruritus in adult palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, CD008320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaçi, D.; de la Cueva, P.; E Pink, A.; Jalili, A.; Segaert, S.; Hjuler, K.F.; Calzavara-Pinton, P. General practice recommendations for the topical treatment of psoriasis: A modified-Delphi approach. BJGP Open 2020, 4, bjgpopen20X101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.-Y.; Li, Z.-H.; Deng, B.-N.; Luo, X.; Lan, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, L.-F.; Liu, C.-Y.; Liu, T.-H.; Wang, Y.-X.; et al. A nomogram for predicting the risk of preeclampsia in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy based on prenatal monitoring time: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. J. Hypertens. 2023, 42, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elling, S.; McKenna, P.; Powell, F. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy in twin and triplet pregnancies. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2000, 14, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sävervall, C.; Sand, F.L.; Thomsen, S.F. Pemphigoid gestationis: Current perspectives. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrackiene, J.; Beuers, U.; Kupcinskas, L. Efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid versus cholestyramine in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology 2005, 129, 894–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massone, C.; Cerroni, L.; Heidrun, N.; Brunasso, A.M.G.; Nunzi, E.; Gulia, A.; Ambros-Rudolph, C.M. Histopathological diagnosis of atopic eruption of pregnancy and polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2014, 36, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles-Holmes, R. Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy. In Dermatology Therapy. A to Z Essentials; Springer eBooks: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; p. 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breier-Maly, J.; Ortel, B.; Breier, F.; Schmidt, J.; Hönigsmann, H. Generalized Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy (Impetigo herpetiformis). Dermatology 1999, 198, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shornick, J.K.; Black, M.M. Secondary autoimmune diseases in herpes gestationis (pemphigoid gestationis). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1992, 26, 563–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Wasmuth, H.; Glantz, A.; Keppeler, H.; Simon, E.; Bartz, C.; Rath, W.; Mattsson, L.-A.; Marschall, H.-U.; Lammert, F. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: The severe form is associated with common variants of the hepatobiliary phospholipid transporter ABCB4 gene. Gut 2007, 56, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefaniak, A.A.; Pereira, M.P.; Zeidler, C.; Ständer, S. Pruritus in Pregnancy. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2022, 23, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zejnullahu, V.A.; Zejnullahu, V.A. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy: A case report. Dermatol. Rep. 2022, 15, e9546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, Y.; Yu, N.; Yi, X.; Ding, Y. Successful Treatment of Recurrent Pustular Psoriasis of Pregnancy with Secukinumab: A Case Report. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2020, 100, adv00251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, A.; Jabery, Z.; Fallah, N. Prevalence and awareness of melasma during pregnancy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, Q.; Xia, Y. New Mechanistic Insights of Melasma. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 16, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, S. The dermatoses of pregnancy. Indian J. Dermatol. 2008, 53, 103–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waheed, M.I.A.; Jaiswal, A.; Yelne, S.; Nandanwar, V. Navigating perinatal challenges: A comprehensive review of cholestasis of pregnancy and its impact on maternal and fetal health. Cureus 2024, 16, e58699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, L.C.; Bell, J.L.; Smith, A.; Rounding, C.; Bowler, U.; Linsell, L.; Juszczak, E.; Tohill, S.; Redford, A.; Dixon, P.H.; et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid to reduce adverse perinatal outcomes for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: The PITCHES RCT. Effic. Mech. Eval. 2020, 7, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, H.-N.; Ruan, Y.-P.; Liu, Y.; Pan, M.; Zhong, H.-P. Diagnosis, fetal risk and treatment of pemphigoid gestationis in pregnancy: A case report. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 10645–10651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.J.; Hauth, J.C.; Bottoms, S.F.; Iams, J.D.; Sibai, B.; Thom, E.; Moawad, A.H.; Thurnau, G.R. Benefits of maternal corticosteroid therapy in infants weighing ≤1000 grams at birth after preterm rupture of the amnion. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 180, 677–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandoli, G.; Palmsten, K.; Forbess Smith, C.J.; Chambers, C.D. A review of systemic corticosteroid use in pregnancy and the risk of select pregnancy and birth outcomes. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 43, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, R.; Sticherling, M. Chronisch entzündliche und autoimmun vermittelte Dermatosen in der Schwangerschaft. Der Hautarzt 2010, 61, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisshaar, E.; Szepietowski, J.; Dalgard, F.; Garcovich, S.; Gieler, U.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Lambert, J.; Leslie, T.; Mettang, T.; Misery, L.; et al. European S2k Guideline on Chronic Pruritus. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2019, 99, 469–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.-C.; Wang, S.-H.; Wojnarowska, F.; Kirtschig, G.; Davies, E.; Bennett, C. Safety of topical corticosteroids in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD007346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malka, I.; Ziv, M. Safety of common medications for treating dermatology disorders in pregnant women. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2013, 2, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambros-Rudolph, C.M.; Glatz, M.; Trauner, M.; Kerl, H.; Müllegger, R.R. The importance of serum bile acid level analysis and treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Arch. Dermatol. 2007, 143, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mervic, L. Management of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in pregnancy and lactation in the era of biologics. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2014, 23, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, M.; Muhammad, Z.; Akhter, N.; Alam, S.S. Effects of ursodeoxycholic acid treatment for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy on maternal and fetal outcomes. Cureus 2024, 16, e70800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apalla, Z.; Nikolaou, V.; Fattore, D.; Fabbrocini, G.; Freites-Martinez, A.; Sollena, P.; Lacouture, M.; Kraehenbuehl, L.; Stratigos, A.; Peris, K.; et al. European recommendations for management of immune checkpoint inhibitors-derived dermatologic adverse events. The EADV task force ‘Dermatology for cancer patients’ position statement. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2021, 36, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).