Abstract

Background: The transition from student to registered nurse is a vulnerable period characterised by emotional strain, role ambiguity, and transition shock. Although Graduate Nurse Transition Programs (GNTPs) aim to strengthen early practice readiness, few evaluations use longitudinal, theory-informed approaches or validated tools. Aim: To examine the professional role development of new graduate nurses (NGNs) across three transition stages within a major Australian health service. Design and Methods: A longitudinal quantitative study guided by Duchscher’s Stages of Transition Theory and the Transition Shock Model. A customised 75-item questionnaire—adapted from the Professional Role Transition Risk Assessment Instrument and the Professional and Graduate Capability Framework—was administered at three transition points (March 2020–March 2021). Four domains were assessed: Responsibilities, Role Orientation, Relationships, and Knowledge and Confidence. Descriptive statistics, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), chi-square tests, and multinomial logistic regression identified developmental patterns and predictors of transition stage. Results: PCA supported a four-factor structure consistent with the theoretical domains, explaining 62% of variance. Significant stage-based improvements were found in clinical decision-making (RS6, p = 0.005), managing pressure (RS11, p = 0.003), leadership perception (RO5, p = 0.001), and emotional regulation (RL20, p < 0.001). Regression analysis identified role confusion (RS7, χ2 = 18.112, p = 0.001), leadership potential (RL1, χ2 = 25.590, p < 0.001), workplace support (RL16, χ2 = 12.760, p = 0.013), and critical thinking confidence (KN13, χ2 = 10.858, p = 0.028) as strong predictors of transition stage. By Stage 3, most NGNs demonstrated increased autonomy, confidence, and professional integration. A coordinator-to-graduate ratio of 1:12 facilitated personalised mentorship. Conclusions: Findings provide robust evidence for theoretically grounded GNTPs. Tailored interventions—such as early mentorship, mid-stage stress support, and late-stage leadership development—can enhance role clarity, confidence, and workforce sustainability.

1. Introduction

The transition from student to professional nurse represents a critical juncture that strongly influences long-term outcomes such as job satisfaction, clinical competence, and workforce retention [1,2,3,4,5]. This period is often marked by a rapid escalation in responsibility, emotional strain, and adjustment to complex professional roles [6,7]. New graduate nurses (NGNs) frequently report feeling underprepared for clinical realities, experiencing what Duchscher (2009) terms “transition shock” [8], characterised by cognitive overload, emotional instability, and temporary loss of confidence [9]. These early workplace encounters shape individual career trajectories and affect the stability and sustainability of the nursing workforce [10,11,12].

To address these challenges, healthcare systems have implemented Transition to Practice Programs (TTPPs) and Graduate Nurse Transition Programs (GNTPs) [13,14,15], which provide structured orientation, supervision, professional development, and mentorship opportunities [11,16]. Evidence shows that such programs improve clinical performance [17], enhance confidence and professional identity [18], reduce attrition [19], and improve patient care quality [20]. However, despite their benefits, many GNTPs lack consistent theoretical foundations, and their long-term impact remains under-evaluated through rigorous longitudinal, quantitative methods [11]. Few studies have tracked NGNs across multiple transition stages, and most available evidence is cross-sectional or qualitative, limiting understanding of how role clarity, confidence, and workplace integration unfold over time. There is also limited empirical validation of Duchscher’s Stages of Transition Theory and minimal use of integrated, theoretically aligned measurement tools.

Duchscher’s Stages of Transition Theory and Transition Shock Model are widely recognised frameworks describing NGNs’ progression through “Doing,” “Being,” and “Knowing”—stages characterised by task-focused survival, role internalisation, and emerging autonomy [21,22,23]. Although influential in policy and program design, few empirical studies have examined NGNs’ movement through these stages or the domain-specific factors predicting successful transition. Much existing work is qualitative or cross-sectional, restricting insight into how professional growth evolves over time or how transition frameworks operate in practice [24].

Recent reviews emphasise the need for theory-driven, longitudinal approaches to capture the complexity of NGN development [17]. Edwards et al. (2015) highlight key dimensions requiring monitoring—including role clarity, decision-making, workplace relationships, and emotional regulation—which are particularly relevant in high-pressure acute care settings where early-career stress is heightened [25,26]. Yet most evaluations still rely on single time-point designs, offering snapshots rather than developmental trajectories. Few studies follow graduates longitudinally across defined transition stages, and no known research has synthesised the Professional Role Transition Risk Assessment Instrument with the Professional and Graduate Capability Framework to create a robust, domain-based tool suitable for longitudinal testing.

These gaps highlight the need for longitudinal, theory-driven research using validated measurement tools. To address this, we developed a customised 75-item survey aligned with Duchscher’s theoretical domains—Responsibilities, Role Orientation, Relationships, and Knowledge and Confidence—to capture stage-based transition patterns.

The present study provides a longitudinal evaluation of a GNTP within a major Australian health service across public and private hospitals. The program was intentionally designed around Duchscher’s principles and supported by policy-directed interventions from Graduate Nurse Coordinators, preceptors, and clinical educators. The customised survey was administered across three transition stages (Stage 1: March–July 2020; Stage 2: July–October 2020; Stage 3: October 2020–March 2021), assessing four domains central to professional development.

The study aimed to evaluate how NGNs’ perceptions and capabilities evolve during the first year of practice by (1) tracking changes across the four domains, (2) identifying statistically significant differences between transition stages, and (3) determining predictors of successful transition. In doing so, it offers data-driven validation of a theory-informed transition framework and new insights into NGN development within complex healthcare environments [27].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Framework

This study used a quantitative design embedded within a structured Graduate Nurse Transition Program (GNTP) informed by Duchscher’s Stages of Transition Theory and the Transition Shock Model. A customised 75-item survey—adapted from the Professional Role Transition Risk Assessment Instrument and the Professional and Graduate Capability Framework—was administered at three time points (1, 5, and 11 months) across a 12-month program within a major Australian health service comprising both public and private hospitals. The design enabled assessment of transition-related perceptions and competencies across four domains: Responsibilities, Role Orientation, Relationships, and Knowledge and Confidence. Although the approach drew on Cusack et al. [22], all procedural elements—including survey structure, administration schedule, and analytical techniques—are described in full to ensure clarity and independence.

The theoretical underpinnings of Duchscher’s framework were operationalised through policy directives within the GNTP. Graduate Nurse Coordinators, Nurse Managers, and preceptors supported structured orientation, educational sessions, and systematic evaluation consistent with the model.

Longitudinal Structure and Follow-Up

Participation at each survey wave was voluntary. Anonymous unique identifiers enabled linkage of repeated responses without compromising confidentiality. A total of 72 participants completed the Stage 1 survey, 56 completed Stage 2, and 30 completed Stage 3, reflecting expected attrition across the GNTP while allowing both cross-sectional and longitudinal insights into transition patterns.

Given this variation in participation, the study employed a hybrid longitudinal–cross-sectional design. Repeated responses were analysed within-subjects where possible, while differing participation across stages necessitated cross-sectional comparisons for some analyses. This structure allowed examination of both developmental progression among returning participants and broader stage-based differences across the full cohort, providing a comprehensive view of transition experiences within the GNTP.

2.2. Survey Instrument and Domains

A customised 75-item survey was developed by synthesising two established frameworks: the Duchscher Professional Role Transition Risk Assessment Instrument [8] and the Professional and Graduate Capability Framework [28,29]. Both frameworks were reviewed item-by-item to identify overlapping constructs related to new graduate nurses’ responsibilities, role clarity, workplace relationships, and application of clinical knowledge. Where conceptual similarities were identified, items were merged or reworded for consistency. Unique items from each framework were retained to ensure comprehensive domain coverage, while redundant, ambiguous, or highly similar items were removed to minimise respondent burden and enhance clarity across domains.

The final survey was organised into four domains central to transition—Responsibilities, Role Orientation, Role Learning, and Knowledge & Confidence. Each item was mapped to one of these domains based on its underlying construct, ensuring alignment with Duchscher’s theoretical principles. This structure provided a domain-based assessment capable of capturing nuanced changes across transition stages.

An emotional wellbeing component was incorporated using items from Cusack et al. [22], reflecting the psychosocial aspects of transition. These items assessed anxiety related to shift changes, difficulty sleeping due to work concerns, workload stress, emotional responses to clinical incidents, and consideration of leaving the workplace or profession. All items utilised a standardised 7-point Likert scale, promoting coherence and supporting consistent statistical treatment across analyses.

To enhance transparency and facilitate replication, the full survey instrument is provided as a Supplementary File S1 (SF Professional Role Transition Tool v1).

2.3. Data Collection and Sample

Online surveys were administered via SurveyMonkey™ (2000) at three transition-aligned time points across the 12-month Graduate Nurse Transition Program. New Graduate Registered Nurses (NGRNs) employed in both public and private hospitals within a large national Australian health service were invited to participate using their work email accounts. Surveys were distributed at one month (Stage 1), five months (Stage 2), and eleven months (Stage 3) into the program. Participation was voluntary at each wave, and respondents could complete one or multiple surveys depending on availability. The final sample comprised 158 graduate nurses who completed at least one survey, forming the basis for both cross-sectional and hybrid longitudinal analyses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were first generated to summarise item-level patterns across the three transition stages, reporting means and standard deviations. These analyses provided an overview of how graduate nurses’ perceptions of role clarity, clinical confidence, and workplace integration changed across stages.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was then conducted to examine the underlying factor structure of the survey and validate its four conceptual domains: Responsibilities (RS), Role Orientation (RO), Role Learning (RL), and Knowledge and Confidence (KN). PCA was performed separately for each transition stage and for the combined dataset to assess consistency and progression over time. Sampling adequacy was confirmed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) statistic, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity verified the suitability of the correlation matrix. Components with eigenvalues > 1.0 were retained (Kaiser’s criterion) and varimax rotation was applied to enhance interpretability. Items with factor loadings ≥ 0.40 were assigned to their respective factors, and where cross-loadings occurred (≥0.40 on multiple factors), items were allocated based on theoretical alignment. Items with low or unclear loadings (<0.40) were excluded. This process strengthened the construct validity of the instrument and identified meaningful thematic changes across stages.

For inferential analysis, the original 7-point Likert responses were recoded into three ordinal categories to meet chi-square and logistic regression assumptions: “Disagree” (1–3), “Neutral” (4), and “Agree” (5–7). Chi-square (χ2) tests were used to determine whether item response distributions differed significantly across the three transition stages, identifying shifts in development, confidence, and workplace integration.

Multinomial logistic regression was then used to identify predictors of transition stage, with Stage 3 set as the reference category. Each item was analysed individually to assess its association with being in Stage 1 or Stage 2 relative to Stage 3. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were reported, and all models were adjusted for potential confounders. All item-level results were presented to provide a comprehensive overview across domains.

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 30), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

The findings reveal clear stage-based differences in new graduate nurses’ experiences across the three transition points. Consistent patterns emerged across the four domains—Responsibilities, Role Orientation, Relationships, and Knowledge/Confidence—showing progressive development at the group level. Graduates in later stages reported higher levels of clinical confidence, stronger leadership perception, improved workplace integration, and enhanced critical thinking. These results reflect cohort-level shifts across transition stages rather than uniform individual-level change.

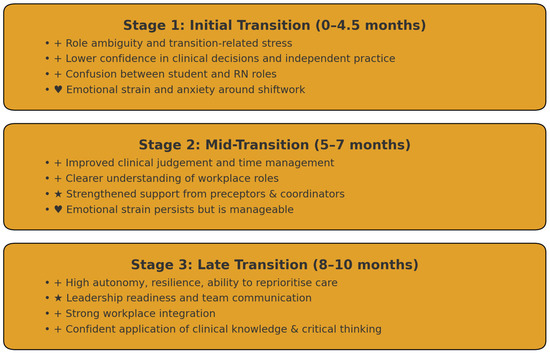

Figure 1 illustrates the overall trajectory. Stage 1 (0–4.5 months) was characterised by role ambiguity, lower confidence in independent practice, and ongoing adjustment to workplace expectations, alongside emotional strain linked to shiftwork and adapting to responsibility. By Stage 2 (5–7 months), graduates demonstrated clearer clinical judgement, improved organisation and prioritisation skills, and stronger relational support from preceptors, coordinators, and peers. Emotional demands remained present but showed signs of stabilisation. Stage 3 (8–10 months) reflected consolidation: participants displayed greater autonomy, resilience, leadership readiness, and stronger alignment with professional identity, alongside increased confidence in applying clinical knowledge.

Figure 1.

Overview of Role, Skill, and Emotional Development Across Transition Stages. Note: The symbols are used as visual markers to reflect key elements of graduate nurse transition. “+” denotes incre-mental growth in responsibilities, skills, and workplace adaptation; “★” represents emerging competence, confidence, and early leadership potential; and “♥” signifies emotional wellbeing, relational support, and the development of pro-fessional identity during the transition process.

Across all domains, the data indicate a transition from early uncertainty to more stable professional functioning as graduates progress through the program. These stage-based patterns align with the conceptual progression described in Duchscher’s Stages of Transition Theory. Detailed results, including descriptive statistics, factor structures, chi-square comparisons, and regression findings, are presented in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 1.

Summary of Key Transition Variables Across Three Stages of Graduate Nurse/Midwife Experience.

Table 2.

Factor Structure and Item Groupings Across the Four Transition Domains.

Table 3.

Significant Chi-Square Associations Between Transition Items and Training Stage.

Table 4.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Predictors of Transition Stage, Grouped by Domain.

Table 1 summarises key indicators of transition across the three stages. Overall, the results demonstrate a clear, stage-based progression in clinical confidence, workplace functioning, and professional integration. Graduates reported gradual increases in clinical communication skills, independence in practice, workload management, and responsiveness to changing patient needs, reflecting a steady consolidation of core competencies from Stage 1 to Stage 3.

Interpersonal and team-related indicators also strengthened over time. Perceptions of being respected and accepted within the workplace improved across stages, suggesting enhanced social integration and growing professional identity. Comfort in approaching preceptors and senior staff remained consistently high, indicating strong supervisory support throughout the program.

Emotional stability showed a similar positive pattern, with participants reporting greater calmness under pressure and consistently low intentions to leave the profession. Knowledge-related variables—including confidence in critical thinking—also increased, supported by stable perceptions of organisational backing for ongoing development.

Collectively, these trends illustrate a coherent developmental trajectory: graduates become progressively more confident, better integrated into their teams, and more assured in their professional roles as they advance through the transition stages. Full item-level means and standard deviations for all 75 survey variables are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 2 presents the factor structure of the customised survey, organised around four domains central to new graduate nurses’ transition: Responsibilities, Role Orientation, Role Learning, and Knowledge & Confidence. Each domain represents a distinct aspect of early professional development and illustrates how graduates progress from initial uncertainty toward increasing confidence and workplace integration, with stronger ratings typically observed in later stages.

The Responsibilities domain captures understanding of clinical duties, confidence in everyday practice, workload adaptation, time management, and early autonomy. Together, these factors reflect the shift from role ambiguity in early transition to more consistent and independent clinical functioning.

The Role Orientation domain reflects graduates’ developing clarity around expectations, accountability, and emerging leadership. Items highlight how respect, socialisation, and workplace culture influence professional adjustment and how graduates increasingly understand their role in multidisciplinary teams.

The Role Learning domain includes teamwork behaviours, safe practice processes, supervisory engagement, and emotional adjustment. These factors show how graduates move from reliance on senior staff toward stronger professional identity, improved coping strategies, and increased comfort in the clinical environment.

The Knowledge & Confidence domain assesses preparedness for clinical work, clinical reasoning, understanding of transition processes, and the alignment between expectations and practice. These elements illustrate the transition from reliance on formal education toward confident application of knowledge in real-world settings.

To enhance clarity, Table 2 is organised with sequential domain headings and factor subheadings, allowing readers to follow how items cluster conceptually within each domain. Full item-level factor loadings and associated statistics are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 3 illustrates clear stage-based differences in graduates’ development across the four transition domains. Significant improvements were evident in clinical communication, emotional regulation, leadership readiness, workplace respect, and critical thinking. The most substantial gains appeared in the Responsibilities and Role Learning domains, with additional but selective progress in Role Orientation and Knowledge & Confidence. Collectively, the results reflect a shift from early-stage uncertainty and role confusion toward later-stage professional identity, autonomy, and emotional resilience.

Responsibilities (RS): Graduates showed marked progression in core clinical competence. The strongest improvement was reduced role confusion (RS7; χ2(4) = 24.477, p < 0.001). Growth was also evident in communication and clinical judgement (RS3, RS6, RS9), along with better organisation and stress regulation (RS10, RS11). These patterns reflect a transition from task-focused coping to increased mastery and confidence.

Role Orientation (RO): Three indicators showed meaningful development: increased engagement in leadership behaviours (RO5), enhanced perceptions of peer respect (RO6), and improved clinical issue identification (RO12). While other items remained stable, these gains demonstrate strengthening leadership potential and workplace integration.

Role Learning (RL): Several elements progressed significantly. Perceived leadership potential rose (RL1), and comfort engaging with senior staff improved (RL7). Increased involvement in clinical incidents (RL18) likely reflects expanded responsibility over time. Emotional indicators (RL20, RL21) also shifted, suggesting that as responsibility grows, some stress persists—reinforcing the need for sustained wellbeing support during transition.

Knowledge & Confidence (KN): This domain was generally stable, but critical thinking confidence (KN5) significantly improved (χ2 = 11.303, p = 0.023). Items approaching significance indicate gradual refinement of applied judgement as clinical exposure increases.

A full list of nonsignificant items is provided in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 4 summarises the multinomial logistic regression findings identifying item-level predictors of transition stage across the four domains: Responsibilities (RS), Role Orientation (RO), Relationships (RL), and Knowledge and Confidence (KN). Transition was categorised into Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3.

In the Responsibilities domain, confusion between the student and registered nurse role (RS7, χ2 = 18.112, p = 0.001) strongly predicted earlier transition stages, indicating that role clarity strengthens as graduates progress. Confidence in remaining calm under pressure (RS11, χ2 = 11.177, p = 0.025) was associated with later stages, reflecting the development of emotional regulation. Time management (RS10, p = 0.089) and workplace social participation (RS14, p = 0.075) showed emerging but nonsignificant trends toward supporting transition progression.

Within the Role Orientation domain, the ability to identify core clinical issues (RO12, χ2 = 27.538, p < 0.001) was the strongest domain-level predictor, underscoring the importance of developing clinical reasoning. Graduates who balanced work and personal life (RO14, χ2 = 10.705, p = 0.030), accepted constructive feedback (RO15, χ2 = 10.988, p = 0.027), or questioned their decision to join the profession (RO17, χ2 = 9.545, p = 0.049) also demonstrated significant stage variation, reflecting evolving professional identity and self-assessment.

The Relationships domain contained multiple strong predictors of transition progression. Being viewed as a potential leader (RL1, χ2 = 25.590, p < 0.001) and feeling comfortable approaching coworkers (RL12, χ2 = 26.223, p < 0.001) were both strongly associated with later stages. Indicators of workplace support (RL16, χ2 = 12.760, p = 0.013), involvement in clinical incidents (RL18, χ2 = 36.640, p < 0.001), pre-shift anxiety (RL19, χ2 = 10.494, p = 0.033), and shift-related sleep difficulty (RL20, χ2 = 25.483, p < 0.001) also differentiated transition stages. Together, these findings emphasise the combined influence of relational confidence, psychological strain, and increasing responsibility.

In the Knowledge and Confidence domain, feeling adequately prepared by formal education (KN1, χ2 = 10.190, p = 0.037) and holding realistic expectations of one’s abilities (KN13, χ2 = 10.858, p = 0.028) were significantly associated with progression to later stages. These results suggest that both perceived readiness and accurate self-evaluation contribute meaningfully to transition advancement.

Overall, Table 4 illustrates that graduate nurse transition is shaped by an interconnected set of cognitive, emotional, relational, and competence-based factors. Enhancing transition support therefore requires multi-domain strategies that foster role clarity, emotional resilience, workplace relationships, and confidence in clinical decision-making.

Only items with statistically significant associations (p < 0.05) are presented. Full results for all items are provided in Supplementary Table S4.

4. Discussion

This study offers longitudinal, empirical support for Duchscher’s Stages of Transition Theory and the Transition Shock Model [8,21], demonstrating the multidimensional progression that new graduate nurses (NGNs) experience during their first year of practice. The stage-based patterns identified in this study reflect a shift from initial emotional strain, role ambiguity, and cognitive overload toward increasing confidence, autonomy, and professional integration. These findings align with prior research underscoring the vulnerability of early-career nurses and the crucial role of structured transition support in shaping successful professional development, job satisfaction, and retention [11,13,30].

Because participation varied across survey waves, the findings reflect group-level stage patterns rather than uniform within-subject trajectories. Although anonymous identifiers enabled linking repeated responses, the design represents a hybrid longitudinal–cross-sectional structure. As such, references to “growth,” “improvement,” or “development” describe differences between respondents at each stage rather than guaranteed individual change. This distinction is especially relevant when interpreting emotional, cognitive, and professional indicators that may evolve differently across individuals.

Overall, the stage-based differences observed in this study are consistent with the conceptual foundations of Duchscher’s theory. Early stages were characterised by heightened emotional distress, role confusion, and reduced confidence, whereas later stages reflected more consolidated professional identity, stronger relational integration, and greater confidence in clinical decision-making. The alignment between theoretical expectations and empirical patterns reinforces the value of using a domain-aligned, theory-driven measurement instrument to evaluate transition trajectories.

In Stage 1, participants exhibited characteristics typical of transition shock, including low confidence (RS3), role confusion (RS7), and difficulty coping with workplace stressors (RS11). These indicators were statistically significant across stages (RS7: χ2 = 18.112, p = 0.001; RS11: χ2 = 11.177, p = 0.025), consistent with Duchscher’s (2008) description of the emotional dissonance and role ambiguity that characterise the early phase of practice [21]. Labrague and McEnroe-Petitte (2018) similarly identified that NGNs commonly experience anxiety and low self-efficacy due to the gap between academic preparation and real-world clinical demands [7]. PCA loadings further confirmed this: RS2 and RS7 loaded on factors related to stress and misalignment across all three phases, underscoring the persistent impact of educational-practice incongruence [17].

Mentorship emerged as a key enabler of progression [30,31]. The 1:12 GNTP coordinator-to-graduate ratio allowed for regular, individualised support, which participants consistently identified as a facilitator of emotional regulation, relational confidence, and workplace integration [22]. Logistic regression revealed that RL10 (support from GNTP coordinator), RL11 (L&D coordinator), and RL12 (peer approachability) significantly predicted progression to later stages (e.g., RL12: χ2 = 26.223, p < 0.001). These results align with previous studies which found that quality mentorship and consistent access to experienced staff enhance graduate nurse adjustment, confidence, and job satisfaction [32,33,34]. This also emphasised that support structures must be flexible and responsive to individual needs, which was a key feature of the program examined in this study [33,35].

Stage 2 findings showed marked improvements in clinical communication (RS3), self-assessed knowledge (KN5), and the ability to prioritise and analyse information (RO12). These outcomes suggest a shift from coping to consolidation, consistent with findings by Gardiner and Sheen (2016) [36], who reported that mid-transition periods are crucial for reinforcing skills and promoting confidence through team integration. RO12, in particular, emerged as a strong predictor of transition stage (χ2 = 27.538, p < 0.001), reflecting the increasing importance of critical thinking in professional maturity [37].

Stage 3 reflected a transition into autonomy and professional identity. Participants scored highly on RS13 (care plan adjustment), RO5 (leadership roles), and KN2 (clinical decision confidence), and these items showed high PCA loadings in Phase 3 (e.g., RS13: 0.894; RO5: 0.872). These findings align with Ankers et al. (2018) and Charette et al. (2023), who reported increased decision-making autonomy and leadership emergence as key features of late-stage transition [30,38]. Participants also showed improvements in emotional resilience (RS12) and adaptability (KN4), indicating a move from dependence to competence, as outlined in Duchscher’s “Knowing” stage [39,40].

Despite these advancements, emotional stressors remained evident. RL19 (worry before shifts) and RL20 (sleep disturbances) were significantly associated with earlier stages (RL20: χ2 = 25.483, p < 0.001), highlighting that psychological burdens can persist even as clinical skills improve. This is supported by Epsteins et al. (2020), who noted that sleep disruption and emotional fatigue often continue throughout the first year, regardless of competence gains [41].

Multinomial logistic regression identified a set of robust predictors across domains. Items such as RS7 (role confusion), RO17 (doubt about career choice), RL1 (perceived leadership potential), and KN1 (perception of academic preparation) significantly predicted stage placement. For instance, RO17 (χ2 = 9.545, p = 0.049) was associated with questioning one’s career decision, particularly in Stage 1, a pattern also identified by Hunter and Cook (2018), who advocated for incorporating clinical realism into undergraduate education to help manage expectations [42].

Institutional support and interpersonal relationships were also significant. Items reflecting comfort in approaching senior staff (RL7), perceived respect (RO6), and availability of mentorship (RL10–12) were consistently linked with higher transition stages. These results echo Whitehead et al. (2016) and Kaihlanen et al. (2020), who emphasised that feeling respected and supported within teams directly contributes to professional integration [17,43].

Overall, this study contributes empirical evidence to the growing body of literature supporting structured, theory-informed transition programs [44]. The progression observed, from initial anxiety and uncertainty to emerging autonomy and leadership, mirrors findings reported across diverse healthcare settings and highlights the interconnected roles of individual development and institutional support [17,40,45,46].

These findings emphasise the importance of structured, stage-specific support systems that address early emotional stress, foster clinical skill consolidation during the mid-transition phase, and promote leadership development in the later stages to support a successful transition to professional practice [47,48].

The generalisability of these findings is limited by the study’s context within a single Australian health service. Organisational culture, support structures, and staffing models may differ across institutions and regions, potentially affecting transition experiences. Therefore, while the observed developmental trajectories align with established theory and comparable international studies, caution should be exercised in applying these results to graduate nurse cohorts in different healthcare settings or countries.

Because of the hybrid longitudinal–cross-sectional structure, the term “transition trajectory” refers to differences observed across groups at each stage rather than continuous within-subject change for all participants. The use of anonymous identifiers allowed some repeated-response linkage; however, varying participation means these patterns represent aggregated trends rather than definitive developmental progression for every graduate. This distinction is important for interpretation and has been addressed throughout the manuscript by emphasising stage-based differences.

This study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Although the longitudinal design provides valuable insights into graduates’ progression over time, all data were self-reported and may be influenced by recall bias or social desirability. The sample was drawn from a single Australian health service, which may limit generalisability to other regions or international settings. Attrition across survey waves may also have affected representativeness in later stages, although a substantial proportion of participants contributed data at more than one time point. In addition, while robust statistical techniques such as PCA and multinomial logistic regression were employed, some predictors of transition success may not have been captured due to the item-level modelling approach. Finally, although the survey instrument was adapted from validated frameworks, its psychometric properties may evolve over time and should be re-evaluated in future cohorts.

5. Conclusions

This study identified clear stage-based differences in the transition experiences of graduate nurses and midwives, demonstrating how responsibilities, role orientation, workplace relationships, and professional confidence vary across early, mid, and later transition points. Key predictors of transition stage included reduced role confusion, leadership potential, perceived workplace support, and realistic self-assessment of clinical abilities. These findings address the study’s objectives by clarifying which factors align with more advanced stages of transition and how they contribute to professional development.

The results reinforce the value of structured Graduate Nurse Transition Programs grounded in theory and organisational policy. Interventions tailored to each stage—such as early mentorship, mid-stage stress-management strategies, and late-stage leadership opportunities—can strengthen role clarity, confidence, and workplace integration. Sustained organisational investment in GNTPs is therefore essential for supporting workforce capability, enhancing retention, and promoting high-quality, safe patient care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nursrep15120437/s1, File S1: Professional Role Transition Tool v1; Table S1: Descriptive Statistics of Key Transition Variables Across Three Stages of Graduate Nurse/Midwife Experience; Table S2: Principal Component Loadings (≥0.40) and Factor Descriptions Across Three Stages; Table S3: Chi-Square Test Results for Survey Items Across Phases: Stage 1, Stage 2, and Stage 3. Table S4: Multinomial Logistic Regression Results: Predictors of Graduate Nurse and Midwife Transition Stage.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C., L.M., J.B.D. and W.Y.; Methodology, L.M. and J.B.D.; Formal analysis, W.Y.; Investigation, L.C. and W.Y.; Writing — original draft, L.C., L.M., J.B.D. and W.Y.; Supervision, W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Calvary Health Care Adelaide’s Human Research Ethics Committee (20-CHREC-E002, approval date 24 March 2020). Participation was entirely voluntary, and recruitment was undertaken independently of managerial or supervisory staff to avoid any perception of obligation among graduate nurses. All participants received written information outlining the study purpose, the voluntary nature of participation, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Surveys were completed anonymously using non-identifiable linkage codes, and no employment-related or personally identifying information was collected. Participants were informed that their responses would remain confidential, inaccessible to managers or educators, and would not influence job evaluations or workplace relationships. All data were securely stored in accordance with institutional governance requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to approval by the relevant Human Research Ethics Committee and in accordance with institutional data sharing policies.

Public Involvement Statement

There was no public involvement in any aspect of this research. Only deidentified data from graduate nursing students were included in the study.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This study was designed, conducted, and reported in accordance with established guidelines for quantitative research in the health sciences. The reporting adheres to the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist for cross-sectional and longitudinal observational studies. All statistical analyses were performed following best practices for psychometric evaluation and multivariable modelling.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

During the initial preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5.0 to enhance readability and language. The tool did not replace essential authoring tasks. After using this tool, all authors reviewed and edited the content and take full responsibility for the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Loren Madsen is employed by Calvary Health Care. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| TTPPs | Transition to Practice Programs |

| GNTPs | Graduate Nurse Transition Programs |

| RS | Responsibilities |

| RO | Roles |

| RL | Relationships |

| KN | Knowledge |

References

- Baharum, H.; Ismail, A.; McKenna, L.; Mohamed, Z.; Ibrahim, R.; Hassan, N.H. Success factors in adaptation of newly graduated nurses: A scoping review. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Carrier, J.; Hawker, C. Effectiveness of strategies and interventions aiming to assist the transition from student to newly qualified nurse: An update systematic review protocol. JBI Evid. Synth. 2019, 17, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggar, C.; Bloomfield, J.; Thomas, T.H.; Gordon, C.J. Australia’s first transition to professional practice in primary care program for graduate registered nurses: A pilot study. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaran, A.J.; Edge, D.S.; Almost, J.; Tregunno, D. New nurses’ perceptions on transition to practice: A thematic analysis. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2023, 55, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.S.L.; Ong, K.K.; Tan, M.M.L.; Mordiffi, S.Z. Evaluation of a graduate nurse residency program: A retrospective longitudinal study. Nurse Educ. Today 2023, 126, 105801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, C.Ç.; Ergün, Y. Transition experiences of newly graduated nurses. Clin. Exp. Health Sci. 2020, 10, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.; McEnroe-Petitte, D. Job stress in new nurses during the transition period: An integrative review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2018, 65, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duchscher, J.E.B. Transition shock: The initial stage of role adaptation for newly graduated registered nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreedi, F.; Brown, M.; Marsh, L.; Rogers, K. Newly Graduate Registered Nurses’ Experiences of transition to clinical practice: A systematic review. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 9, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinkman, M.; Salanterä, S. Early career experiences and perceptions—A qualitative exploration of the turnover of young registered nurses and intention to leave the nursing profession in F inland. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 1050–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, K.L.; Janke, R.; Duchscher, J.E.; Phillips, R.; Kaur, S. Best practices of formal new graduate transition programs: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 94, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morphet, J.; Kent, B.; Plummer, V.; Considine, J. The effect of Transition to Specialty Practice Programs on Australian emergency nurses’ professional development, recruitment and retention. Australas. Emerg. Nurs. J. 2015, 18, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, A.; Dickson-Swift, V.; McKenna, L.; Charette, M.; Rush, K.L.; Stacey, G.; Darvill, A.; Leigh, J.; Burton, R.; Phillips, C. Interventions to support graduate nurse transition to practice and associated outcomes: A systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 100, 104860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangland, E.; Gunningberg, L.; Nyholm, L. A mentoring programme to meet newly graduated nurses’ needs and give senior nurses a new career opportunity: A multiple-case study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 57, 103233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keshk, L.I.; Mersal, F.A. Assessment of graduate nurses entry level competencies: Expectations of faculty members versus nurse managers. Am. J. Nurs. Res. 2017, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, A.; Parks, K.; Beckling, A. Transitioning from student to new graduate nurse. Nurs. Made Incred. Easy 2020, 18, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaihlanen, A.-M.; Elovainio, M.; Haavisto, E.; Salminen, L.; Sinervo, T. Final clinical practicum, transition experience and turnover intentions among newly graduated nurses: A cross sectional study. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 84, 104245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-González, M.; Weise, C. Career transition and identity development in academic nurses: A qualitative study. J. Constr. Psychol. 2022, 35, 1371–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, E.G. A meta-analysis on predictors of turnover intention of hospital nurses in South Korea (2000–2020). Nurs. Open 2021, 8, 2406–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Foster, J. The experiences of new graduate nurses working in a pediatric setting: A qualitative systematic review. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 67, e234–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchscher, J.B. A process of becoming: The stages of new nursing graduate professional role transition. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2008, 39, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, L.; Madsen, L.; Duchscher, J.B.; You, W. Does transition theory matter?: A descriptive study of a transition program in Australia based on duchscher’s stages of transition theory and transition shock model. Aust. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024, 41, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchscher, J.B. From Surviving to Thriving: Navigating the First Year of Professional Nursing Practice; Nursing the Future: Kamloops, BC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pasila, K.; Elo, S.; Kääriäinen, M. Newly graduated nurses’ orientation experiences: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2017, 71, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D.; Hawker, C.; Carrier, J.; Rees, C. A systematic review of the effectiveness of strategies and interventions to improve the transition from student to newly qualified nurse. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2015, 52, 1254–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R.; Everett, B.; Ramjan, L.M.; Hu, W.; Salamonson, Y. New graduate nurses’ experiences in a clinical specialty: A follow up study of newcomer perceptions of transitional support. BMC Nurs. 2017, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaran, A.J.; Edge, D.S.; Almost, J.; Tregunno, D. New registered nurse transition to the workforce and intention to leave: Testing a theoretical model. Can. J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 53, 384–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rochester, S.; Kilstoff, K.; Scott, G. Learning from success: Improving undergraduate education through understanding the capabilities of successful nurse graduates. Nurse Educ. Today 2005, 25, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.; Chang, E.; Grebennikov, L. Using successful graduates to improve the quality of undergraduate nursing programs. J. Teach. Learn. Grad. Employab. 2010, 1, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Charette, M.; McKenna, L.; McGillion, A.; Burke, S. Effectiveness of transition programs on new graduate nurses’ clinical competence, job satisfaction and perceptions of support: A mixed-methods study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2023, 32, 1354–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss, J.G.; Alfes, C.M.; Clark, A.; Lilly, K.D.; Moore, S. Why mentoring matters for new graduates transitioning to practice: Implications for nurse leaders. Nurse Lead. 2022, 20, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, J.-A.M.; Olley, R. Systematic literature review of the effects of clinical mentoring on new graduate registered nurses’ clinical performance, job satisfaction and job retention. Asia Pac. J. Health Manag. 2021, 16, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.C. Characteristics of Successful Nurse Mentors and Potential Effects On The Retention And Job Satisfaction Of New Graduate Nurses: An Integrative Review. Ph.D. Thesis, Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund, A.; Sterner, A.; Nilsson, M.S.; Larsman, P. The impact of transition programs on well-being, experiences of work environment and turnover intention among early career hospital nurses. Work 2025, 80, 1960–1968. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.; Sundin, D.; Cope, V. Supporting new graduate registered nurse transition for safety: A literature review update. Collegian 2020, 27, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, I.; Sheen, J. Graduate nurse experiences of support: A review. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 40, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Perdomo, A.; Zabalegui, A. Teaching strategies for developing clinical reasoning skills in nursing students: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Healthcare 2024, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankers, M.D.; Barton, C.A.; Parry, Y.K. A phenomenological exploration of graduate nurse transition to professional practice within a transition to practice program. Collegian 2018, 25, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Raphael, D.; Mackay, L.; Smith, M.; King, A. Personal and work-related factors associated with nurse resilience: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regan, S.; Wong, C.; Laschinger, H.K.; Cummings, G.; Leiter, M.; MacPhee, M.; Rhéaume, A.; Ritchie, J.A.; Wolff, A.C.; Jeffs, L. Starting out: Qualitative perspectives of new graduate nurses and nurse leaders on transition to practice. J. Nurs. Manag. 2017, 25, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.; Söderström, M.; Jirwe, M.; Tucker, P.; Dahlgren, A. Sleep and fatigue in newly graduated nurses—Experiences and strategies for handling shiftwork. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, K.; Cook, C. Role-modelling and the hidden curriculum: New graduate nurses’ professional socialisation. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3157–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, B.; Owen, P.; Henshaw, L.; Beddingham, E.; Simmons, M. Supporting newly qualified nurse transition: A case study in a UK hospital. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 36, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.M.; Meyer, K.; Riemann, L.A.; Carter, B.T.; Brant, J.M. Transition into practice: Outcomes of a nurse residency program. J. Contin. Educ. Nurs. 2023, 54, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippa, R.; Ann, H.; Jacqueline, M.; Nicola, A. Professional identity in nursing: A mixed method research study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 52, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, K.B.; Richards, K.C. New graduate nurses, new graduate nurse transition programs, and clinical leadership skill: A systematic review. J. Nurses Prof. Dev. 2015, 31, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, G.; Cook, G.; Aubeeluck, A.; Stranks, B.; Long, L.; Krepa, M.; Lucre, K. The implementation of resilience based clinical supervision to support transition to practice in newly qualified healthcare professionals. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 94, 104564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, S.; Redley, B.; Rawson, H. Developing work readiness in graduate nurses undertaking transition to practice programs: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 105, 105034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).