Abstract

Background: Palliative care focuses on the prevention of worsening health, improving the quality of the patient’s life, and the relief of suffering, and therefore has a considerable impact on both the patient suffering from a life-threatening or potentially life-threatening illness and on their family. Spirituality, as the dimension of human life involving the search for meaning, purpose, and transcendence, and connection with oneself, others, and the sacred, could be essential in supporting these patients. The aim of this study was to synthesise the scientific evidence describing the interventions and/or activities undertaken to meet the spiritual needs of the palliative patient. Methods: A literature search was carried out across the following databases: PubMed, LILACS, Scopus, and Web of Science. The PRISMA statement was used to guide this review. Results: Twenty-four articles were included. The thematic categories included spiritual needs at the end of life, the influence of music and dance as palliative care, care for family caregivers, and the comparison between counselling and dignity therapy. Conclusions: Interventions in the biopsychosocial–spiritual spheres impact on the patient’s peace of mind and promote the acceptance of a “good death”. Healthcare personnel play an essential role in the way their patients prepare for the moment of death, and the meaning and values they convey help them to accompany and welcome patients. Last but not least, universities can play a crucial role by training nurses to integrate spiritual interventions such as music and dance, or by considering the family as a unit of care. The systematic review protocol was registered in the Prospective International Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under protocol number CRD42023490852.

1. Introduction

Palliative care is focused on the prevention of worsening symptoms, improving the patient’s quality of life and, consequently, alleviating the suffering of those patients with a life-threatening or potentially life-threatening illness [1,2]. In this process, it is important to emphasise the importance of family care, as the family is the fundamental nucleus of support for the patient, and patient and family together should be treated as a unit, through early identification, assessment and the correct treatment [3,4,5].

The symptoms of palliative patients vary, depending on the nature and the stage of the illness, with assessment of the patient’s spiritual well-being being a critical and fundamental aspect of holistic and multidisciplinary care [6,7,8,9,10].

The Spirituality Guide (Guía de Espiritualidad) produced by the Spanish Society of Palliative Care defines spirituality as “the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way in which the person (individual or community) experiences, expresses and/or looks for meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way in which they connect with the moment, with themselves, with others, with nature, with the significant and/or with the sacred” [11]. Indeed, in recent decades, spirituality has been recognised by researchers as an important resource for coping with the distress that accompanies terminal illness [12].

According to the WHO, counselling is defined as a dynamic process in which two people help each other to gain mutual understanding. Two key characters are involved in this process: the “helped” as the person suffering the illness and the “helper” as the person in charge of accompanying and guiding the patient to help them resolve their conflicts [13,14]. Counselling is a democratic process in which the patient is accompanied and released, through therapeutic communication, from the loneliness and isolation that palliative illness brings [15,16,17].

Healthcare personnel play an essential role in the way their patients prepare for the moment of death, thus humanizing end-of-life care. In this context, inquiring into the interventions and/or activities carried out by healthcare professionals in the spiritual sphere with patients receiving palliative care may be useful for improving the training of future professionals.

The main objective of this study was to systematically review and synthesise the scientific evidence on the impact of spiritual support interventions, including music therapy, dance therapy, counselling, and dignity therapy, on the quality of life and spiritual well-being of adult patients in palliative care settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

A systematic review which is a rigorous method of synthesizing research evidence by systematically collecting, appraising, and analysing studies that meet pre-defined criteria was carried out and presented according to the criteria established by the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) [18]. The systematic review protocol was registered in the Prospective International Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under protocol number CRD42023490852. PROSPERO is an international database for prospectively registering systematic reviews. Registering our review in PROSPERO helps maintain transparency in the review process and allows others to access our protocol to understand the planned methods and objectives.

2.2. Study Selection and Data Extraction

A thorough search of the literature was conducted between November and December 2023 and updated in July 2024 using four databases: PubMed, Scopus, LILACS and Web of Science (WOS). To find the articles, we used a search strategy based on terms related to the spiritual approach, palliative care and quality of life (Table 1). The screening procedures were carried out independently by two reviewers (VPC and PAB) using the Rayyan platform. In the case of conflicting opinions over the inclusion or non-inclusion of an article, a third reviewer (PJLS) was consulted.

Table 1.

Search strategies used in the three databases.

The following data for each study were extracted: authors’ names, year of publication, country, period of study, sample size, study design, types of intervention tested, and main results.

2.3. Criteria for Inclusion

Prior to starting the research, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. We included articles in which (i) the study design was experimental or quasi-experimental; (ii) the study subjects were adults over 18 years of age receiving palliative care; (iii) counselling and/or spiritual counselling were carried out. Counselling is understood as “giving advice or assistance to individuals with educational or personal problems”; while spiritual counselling is understood as “reflecting on the fundamental condition of a person’s sense of self to provide a holistic view of the care received” [19]; (iv) the impact of the intervention on the quality of life of the palliative patient and their family was analysed; (v) the language of publication was Spanish or English; (vi) the publication dates ranged from 1 January 2012 to July 2024.

In contrast, articles were excluded if (i) the study design was observational, qualitative, or any other design which was not experimental or quasi-experimental; (ii) the participants were receiving care (but not palliative care); (iii) the research concerned other situations in which the inclusion criteria were not met: participants under 18 years of age; language of publication not Spanish or English; publication date prior to 2012.

2.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The NIH (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute) “Study Quality Assessment Tools” checklists was used to assess the quality of the evidence included in the studies, which also depended on the design [20]. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias assessment tool for randomised trials (RoB 2) [21].

2.5. Data Synthesis

In synthesizing the results, we employed a thematic categorical approach. This method was chosen due to the considerable heterogeneity of the studies selected for our review. The studies varied widely in terms of their design, interventions, outcomes measured, and patient populations. Consequently, a thematic analysis allowed us to systematically categorise and analyse the findings across different dimensions. By identifying common themes and patterns, we were able to integrate diverse pieces of evidence and draw meaningful conclusions about the impact of spiritual support interventions on the quality of life and spiritual well-being of palliative care patients.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

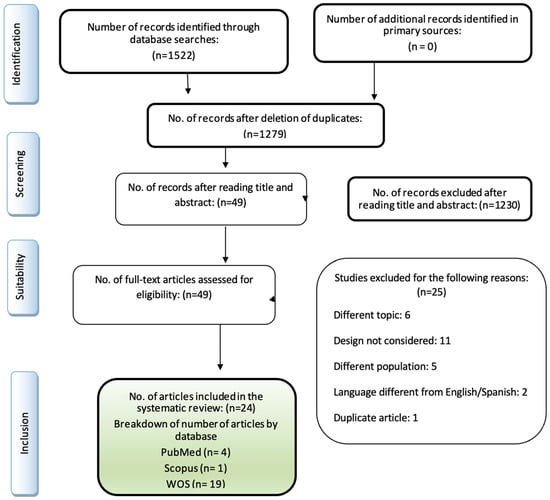

A total of 1522 articles were identified from the initial search of databases. After removing duplicates (n = 243), the title and abstract of 1279 records were assessed, leaving a selection of 49 selected at this stage. No additional references were identified through a manual search in websites or reference lists. After a full reading of the 49 articles, 25 of them were excluded: 6 for having a different topic, 11 articles for being a different type of research study, 5 for being conducted in a non-palliative population, 2 for being written in a language other than English/Spanish and 1 article for being duplicated. Finally, 24 articles were included in the systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection process (PRISMA) flowchart.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The studies addressed diverse outcome variables, including quality of life, spiritual well-being, emotional functioning, and physical health indicators. The interventions tested also varied widely, encompassing counselling, spiritual counselling, music therapy, dance therapy, dignity therapy, and combinations thereof. The settings and samples were equally diverse, ranging from patient-focused interventions to those that included family caregivers as part of the unit of care.

Regarding the study design of the 24 articles included in this systematic review, seven (29%) were quasi-experimental studies, two (8%) were mixed methods studies and fifteen (63%) were randomised clinical trials.

The studies were mainly conducted in the USA (25%, n = 6), followed by the Netherlands, Canada, Spain, Kenya and Germany (8%, n = 2, each country) and the rest from China, Australia, Iran, Czech Republic, Belgium, Malaysia and Hong Kong with one article published. The sample sizes of these studies ranged from 10 to 903.

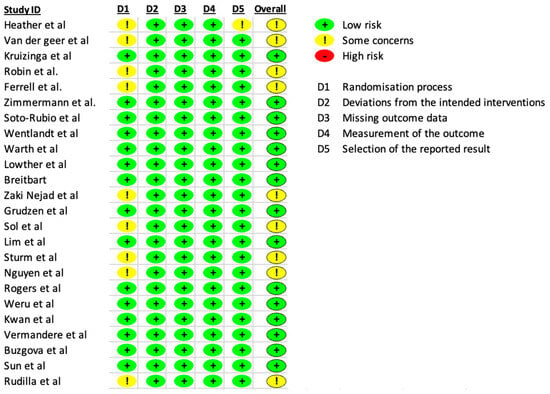

3.3. Risk of Bias and Quality Assesment

Of the 24 studies included, 21 were rated as good after completion of the NIH quality assessment tool, on the other hand, 3 articles rated as fair (Check Supplementary Materials for further information). Among the studies included, thirteen were classified as having a low risk of bias. Nine were classified as having some concerns because they presented deviation from the intended interventions. Figure 2 shows the risk of bias (RoB2) assessment of the included studies.

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment (RoB2) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45].

3.4. Data Extraction

After analysing these 24 articles and extracting the data (Table 2), four main approaches were identified:

Table 2.

Summary of included studies.

- Benefits of Palliative Care for Spiritual Needs at the End of Life: This approach explores how palliative care can address spiritual needs, providing patients with meaning and coherence in their lives. It focuses on improving symptoms such as anxiety and depression, which in turn enhances spiritual well-being.

- Influence of Dance and Music in Palliative Care: This approach examines the impact of dance and music therapy on palliative care patients. The studies showed improvements in emotional, social, and physical functioning, as well as spiritual well-being, through interventions like dance classes and music therapy.

- Effect of Palliative Care on Family Caregivers: This approach considers the broader unit of care, including family caregivers. It highlights how palliative care interventions can stabilise anxiety and depression among caregivers and improve their quality of life and spiritual well-being.

- Comparison between Counselling and Dignity Therapy: The fourth approach compares the effectiveness of counselling and dignity therapy in palliative care settings. Both interventions were found to be beneficial, improving quality of life, reducing distress and anxiety, and helping patients maintain a sense of dignity.

These approaches collectively emphasise the holistic nature of palliative care, integrating physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions to enhance the quality of life for both patients and their caregivers.

3.4.1. Approach 1: Benefits of Palliative Care for Spiritual Needs at the End of Life

At the end of life, new questions about needs arise, but by providing palliative care, healthcare providers can give the patient a great deal of help in finding meaning and coherence in their life [22]. In this context, the quasi-experimental study by Van de Geer et al. reinforces the benefits it accrues for spiritual needs (p = 0.008), as well as those for more restful sleep (p = 0.020) [23].

Palliative care addresses end-of-life anxiety and depression in patients. Based on this premise, clinical trials by Rogers et al. and Sun et al. demonstrated an improvement in depression and anxiety, which in turn led to spiritual improvement [24,25]. However, several studies found no significant differences [26,27].

Last but not least, Wentlandt et al., in a randomised clinical trial, showed that to facilitate a good death and for the patient to be prepared for it, it is necessary to have good doctor–patient communication, be older, live alone, have good spiritual health and suffer fewer symptoms [28,29,30].

3.4.2. Approach 2: The Influence of Dance and Music in Palliative Care

A randomised clinical trial by Sturm et al. explains the influence of dance on fatigue and quality of life in palliative care patients [31]. Specifically, a sample of 40 patients was studied, in which the intervention group was given dance classes and advice for 5 weeks, unlike the control group, which was only given advice. For the former, this resulted in a significant improvement in fatigue, emotional and social functioning and physical performance (p < 0.05) [31].

Finally, music also plays a role in improving palliative care. A randomised clinical trial by Warth et al. with a sample of 104 patients demonstrated the importance of music therapy (“Song of Life”) in palliative care [32]. Specifically, the authors divided the population into two groups: one was given music therapy in addition to the usual care (52 patients), while the other (52 patients) was given a relaxation intervention plus the usual care. The results showed differences with respect to spiritual well-being (p = 0.04) and ego integrity (p < 0.01), which were further improved after music therapy. Furthermore, momentary distress was significantly lower after music therapy (p = 0.05), thus enhancing the patients’ well-being [32].

3.4.3. Approach 3: Effect of Palliative Care on Family Caregivers

The “unit to be addressed” in the spiritual approach is made up of the patient and their family caregivers. Not only can palliative care bring a significant improvement for the patient, but there are also further benefits for the caregiver. In the present review, three studies addressed this theory, demonstrating the benefits of palliative care for primary caregivers.

Hearther R et al. carried out a quasi-experimental study, dividing the study population into two groups: one underwent the LifeCourse intervention (motivational interviewing, individualised person-centred care at the end of life and home visits), while the other group were given the usual care. The LifeCourse intervention stabilised anxiety and depression among family caregivers, while in the other group, anxiety and depression increased [33].

A quasi-experimental study conducted by Nguyen et al. also demonstrated the benefit of palliative care for caregivers, showing an improvement for caregivers in three domains: quality of life (p = 0.05), spiritual well-being (p = 0.03) and care preparation (p = 0,04) [34]. Another study demonstrating the benefits for caregivers was the randomised clinical trial by Kozáková et al. involving 291 participants [35].

3.4.4. Approach 4: Comparison between Counselling and Dignity Therapy for Palliative Patients

Dignity therapy is, by definition, “unique and individualised psychotherapy that enables the patient to review their lives and find meaningful events, people and experiences, thus maintaining their dignity”. This is a key factor in alleviating suffering at the time of death and in fostering hope, self-esteem and meaning in life [36,37].

Two of the studies selected in the present review focus on the search for the benefits of dignity therapy, resulting in an improvement in quality of life in the intervention group (p = 0.001), together with improvements in nausea and vomiting (p = 0.02), appetite (p = 0.02), insomnia (p < 0.01) and constipation (p = 0.001), as well as an improvement in physical and emotional functioning [36,37,38].

A quasi-experimental study with a sample of 30 patients, carried out by Rudilla et al., shows a comparison of the efficacy of the counselling technique with dignity therapy in palliative patients. The results show that both techniques are equally beneficial as they increase quality of life, and reduce distress and anxiety, the latter being improved more by the counselling technique [37].

4. Discussion

This review reflects the importance of a spiritual approach to palliative patients and of meeting their needs at the end of life in order to provide holistic and quality care.

Rego et al. (2020) demonstrated through their cross-sectional study that spiritual well-being increased the patient’s quality of life and that this was associated with greater independence, increased optimism and self-esteem, thus leading to a decrease in depression [46]. Interestingly, the same authors refer to the lack of training of the healthcare staff themselves. In fact, while most of the participating patients emphasised the importance of meeting spiritual needs at the end of life, it was shown that for the majority of them, these needs were not met. This could be put down, in part, to a lack of training: as the health workers were not trained or prepared to act accordingly, they simply did not intervene, because of the unease they experienced when dealing with these situations [46,47,48].

The value of dance and music as an intervention in palliative care has also been highlighted in this review [31,32]. In particular, the study by Woolf et al. states that dance, together with gentle movement, allows the patient to channel interconnected physical and emotional pain. In doing so, it seeks to release the user’s tension and anxiety by allowing them to express themselves as a whole person [49].

Another study concurred that music relieves physical, emotional and spiritual distress and is also useful for improving relaxation and sleep when combined with movement and deep breathing. Thanks to music, positive feelings flourish, leading to a more satisfactory relationship between the palliative patient and their family caregiver. However, the lack of knowledge and limited resources among nurses is an obstacle to these interventions, because, while the nurses are fully aware of the benefits, they often do not know how to use or implement the techniques. Again, this affects not only the patient, but also the primary caregiver [50].

Other interventions that meet patients’ spiritual needs include counselling and dignity therapy. In these areas, the findings, confirmed by other authors [51,52] show that there is a component of therapeutic counselling embedded in dignity therapy; as the techniques are similar, they produce similar results [51].

This systematic review has several limitations. Firstly, the search strategy was carried out using four different databases and so, although it is true that they contain a large number of references, we cannot rule out the possibility that some studies were left out which did not feature in these databases. Secondly, regarding the article selection process, the two main screening reviewers had limited experience, although they were guided and advised by experienced researchers. In utilizing AI and the Rayyan platform for screening articles, we recognise several limitations that were addressed to ensure the rigour of our review. AI tools can introduce biases based on the training data and algorithms used. To mitigate this, we employed a combination of automated and manual screening processes. Two independent reviewers (VPC and PAB) conducted the initial screening using Rayyan, followed by a manual review to verify the AI’s selections. Any discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third reviewer (PJLS). This hybrid approach allowed us to benefit from the efficiency of AI while maintaining the accuracy and reliability of human judgment. Finally, while “counselling” was included as a spiritual intervention, the lack of specific differentiation between general counselling and spiritual counselling leaves some findings incomplete and unfocused. Counselling in this context was broadly defined as providing advice or assistance, which may not fully encapsulate the spiritual aspects intended to be studied. This limitation should be acknowledged as it may have led to an overgeneralisation of the results regarding spiritual interventions. Future studies should aim to more clearly distinguish between general counselling and spiritual counselling to better focus on the spiritual dimensions of patient care.

Based on the findings of our review, particularly the improvements in spiritual well-being and quality of life as observed in the studies by Warth et al. (2021) [32], it is clear that universities can play a crucial role by training nurses to integrate spiritual interventions such as music and dance, or by considering the family as a unit of care. These insights form the basis for rethinking approaches in palliative care, ultimately helping patients to experience a good death, free from suffering.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights the manifold benefits of nursing interventions for the spiritual well-being of palliative patients, emphasizing the importance of biopsychosocial–spiritual care. Our findings suggest that integrating spiritual support, such as music and dance, can significantly enhance the quality of life for both patients and their families, fostering positivity, intimacy, and meaningful memories before the final farewell.

The limited use of spiritual interventions in clinical practice underscores the need for improved training and awareness among healthcare professionals. By reflecting on the importance of addressing spiritual needs, this study aims to inspire better quality palliative care that holistically supports patients and their families. Educational institutions can play a crucial role in this by incorporating training on spiritual interventions into their curricula, thus preparing future nurses to deliver comprehensive care.

Additionally, the similarities between counselling and dignity therapy, both of which effectively address spiritual needs and alleviate distress, highlight the potential for these therapies to be integrated into standard palliative care practices. Further research could explore the long-term benefits of these interventions, their cost-effectiveness, and the development of standardised protocols to ensure consistent implementation.

In summary, this study not only sheds light on the significant impact of spiritual support on palliative care but also calls for continued research and education to enhance the holistic care of patients facing life-threatening illnesses.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nursrep14030142/s1, Table S1: Quality assessment of quasi-experimental studies. Table S2: Quality assessment of mixed methods studies. Table S3: Quality assessment of randomised clinical trials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, V.P.-C., P.A.-B. and P.J.L.-S.; methodology, V.P.-C., P.A.-B. and P.J.L.-S.; software, V.P.-C.; resources, V.P.-C., P.A.-B., E.O.-L., A.G.-A. and P.J.L.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.P.-C.; writing—review and editing, P.A.-B. and P.J.L.-S.; visualisation, E.O.-L. and A.G.-A.; supervision, P.A.-B. and P.J.L.-S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In the context of this systematic review, ethical considerations are not applicable, as the study involves the synthesis and analysis of existing research findings and does not directly involve human subjects or primary data collection.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable in this study.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

We acknowledge the use of Rayyan (http://rayyan.qcri.org, accessed on 15 January 2024) that helped expedite the initial identification of studies using a process of semi-automation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grupo de Trabajo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica Sobre Cuidados Paliativos. Guía de Práctica Clínica Sobre Cuidados Paliativos; Plan Nacional para el SNS del MSC; Agencia de Evaluación de Tecnologías Sanitarias del País Vasco: Madrid, Spain, 2008; Guías de Práctica Clínica en el SNS: OSTEBA No. 2006/08; Available online: https://portal.guiasalud.es/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/GPC_428_Paliativos_Osteba_compl.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Benítez del Rosario, M.A.; Pascual, L.; Asensio Fraile, A. Cuidados paliativos. La atención a los últimos días [Palliative care: Care in the final days]. Aten Primaria. 2002, 30, 318–322. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ignacia, P.M.; Río, D.; Palma, D.A. Cuidados Paliativos: Historia Y Desarrollo. Available online: https://cuidadospaliativos.org/uploads/2013/10/historia%20de%20CP.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Cuidados paliativos. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Honinx, E.; van Dop, N.; Smets, T.; Deliens, L.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Froggatt, K.; Gambassi, G.; Kylänen, M.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.; Szczerbińska, K.; et al. Morir en centros de atención a largo plazo en Europa: El estudio epidemiológico PACE de residentes fallecidos en seis países. BMC Salud Pública 2019, 19, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guía de Cuidados Paliativos Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos SECPAL. Available online: https://www.secpal.com/guia-cuidados-paliativos-1 (accessed on 23 February 2023).

- Bernales, M.; Chandía, A.; San Martín, M.J. Malestar emocional en pacientes de cuidados paliativos: Retos y oportunidades. Rev. Med. Chil. 2019, 147, 813–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez Sáncho, M.; Ojeda Martín, M. Cuidados Paliativos Control de Síntomas. 2009. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=http://sid.usal.es/idocs/F8/FDO23359/cuidados_paliativos.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwi41tyA5tWHAxUjqVYBHWkRAJsQFnoECBQQAQ&usg=AOvVaw0RBqDImHGtT-9DYW6SwXTD (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Reig-Ferrer, A.; Ferrer-Cascales, R.; Fernández-Pascual, M.D.; Albaladejo-Blázquez, N.; Priego Valladares, M. Evaluación del bienestar espiritual en pacientes en cuidados paliativos. Med. Paliativa 2015, 22, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo Higuera, J.C.; Lozano González, B.; Villacieros Durbán, M.; Gil Vela, M. Atención espiritual en cuidados paliativos. Valoración y vivencia de los usuarios. Spiritual needs in palliative care. Users assesment and experience. Med. Paliativa 2013, 20, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzado, J.A. “Espiritualidad en clínica una propuesta de evaluación y acompañamiento espiritual en cuidados paliativos” Enric Benito, Javier Barbero y Mónica Dones, editores. Psicooncología 2015, 12, 195–196. Available online: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/PSIC/article/view/49389 (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Selman, L.; Harding, R.; Gysels, M.; Speck, P.; Higginson, I.J. The measurement of spirituality in palliative care and the content of tools validated cross-culturally: A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2011, 41, 728–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narváez Cienfuegos, F. Cuidados Paliativos: Intervención Psicologica en el Final de la Vida. 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.comillas.edu/rest/bitstreams/430192/retrieve (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Santos, E.; Bermejo, J.C. Counselling y Cuidados Paliativos; Desclée Debrouwer, S.A.: Bilbao, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://clea.edu.mx/biblioteca/files/original/dcb4d2676a5a302de09c388fabf6e86e.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Usal.es. Tipo de Trabajo: Trabajo de Carácter Profesional. Trabajo Fin de Grado. Available online: https://gredos.usal.es/bitstream/handle/10366/143266/TFG_DelgadoSanchez_ComunicacionPalitativos.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Peris, S.F. La comunicación terapéutica: Acompañando a la persona en el camino de la enfermedad. Panace 2016, 17, 111–114. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/oaiart?codigo=5794530 (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Benito, E.; Barbero, J.; Payás, A. (Eds.) Espiritualidad en Clínica Una Propuesta de Evaluación y Acompañamiento Espiritual en Cuidados Paliativos; Sociedad Española de Cuidados Paliativos: Madrid, Spain, 2014; Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.seor.es/wp-content/uploads/Monografia-secpal.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwjHsqOB9NKHAxW7fPUHHecvCScQFnoECBIQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2Cq_Sa4WoIueXbaOUZyP6s (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudilla, D.; Soto, A.; Pérez, M.A.; Galiana, L.; Fombuena, M.; Oliver, A.; Barreto, P. Intervenciones psicológicas en espiritualidad en cuidados paliativos: Una revisión sistemática. Med. Paliativa 2018, 25, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHLBI, NIH. Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. Rob 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Rubio, A.; Perez-Marin, M.; Rudilla, D.; Galiana, L.; Oliver, A.; Fombuena, M.; Barreto, P. Responding to the spiritual needs of palliative care patients: A randomized controlled trial to test the effectiveness of the kibo therapeutic interview. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Geer, J.; Groot, M.; Andela, R.; Leget, C.; Prins, J.; Vissers, K.; Zock, H. Training hospital staff on spiritual care in palliative care influences patient-reported outcomes: Results of a quasi-experimental study. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, J.G.; Patel, C.B.; Mentz, R.J.; Granger, B.B.; Steinhauser, K.E.; Fiuzat, M.; Adams, P.A.; Speck, A.; Johnson, K.S.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; et al. The Palliative Care in Heart Failure (PAL-HF) Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.-H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.-M.; Fan, L. Impact of spiritual care on the spiritual and mental health and quality of life of patients with advanced cancer. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzen, C.R.; Richardson, L.D.; Johnson, P.N.; Hu, M.; Wang, B.; Ortiz, J.M.; Kistler, E.A.; Chen, A.; Morrison, R.S. Emergency department-initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C.W.M.; Chan, C.W.H.; Choi, K.C. The effectiveness of a nurse-led short term life review intervention in enhancing the spiritual and psychological well-being of people receiving palliative care: A mixed method study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 91, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruizinga, R.; Scherer-Rath, M.; Schilderman, J.B.; Hartog, I.D.; Van Der Loos, J.P.; Kotzé, H.P.; Westermann, A.M.; Klümpen, H.-J.; Kortekaas, F.; Grootscholten, C.; et al. An assisted structured reflection on life events and life goals in advanced cancer patients: Outcomes of a randomized controlled trial (Life InSight Application (LISA) study). Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wentlandt, K.; Burman, D.; Swami, N.; Hales, S.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Lo, C.; Zimmermann, C. Preparation for the end of life in patients with advanced cancer and association with communication with professional caregivers: Preparation for the end of life in advanced cancer. Psychooncology 2012, 21, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, V.; Kim, J.Y.; Irish, T.L.; Borneman, T.; Sidhu, R.K.; Klein, L.; Ferrell, B. Palliative care and spiritual well-being in lung cancer patients and family caregivers: Spirituality in lung cancer. Psychooncology 2016, 25, 1448–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, I.; Baak, J.; Storek, B.; Traore, A.; Thuss-Patience, P. Effect of dance on cancer-related fatigue and quality of life. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 2241–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warth, M.; Koehler, F.; Brehmen, M.; Weber, M.; Bardenheuer, H.J.; Ditzen, B.; Kessler, J. “Song of Life”: Results of a multicenter randomized trial on the effects of biographical music therapy in palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britt, H.R.; JaKa, M.M.; Fernstrom, K.M.; Bingham, P.E.; Betzner, A.E.; Taghon, J.R.; Shippee, N.D.; Shippee, T.P.; Schellinger, S.E.; Anderson, E.W. Quasi-experimental evaluation of LifeCourse on utilization and patient and caregiver quality of life and experience. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2019, 36, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.Q.; Ruel, N.; Macias, M.; Borneman, T.; Alian, M.; Becher, M.; Lee, K.; Ferrell, B. Translation and evaluation of a lung cancer, palliative care intervention for community practice. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, 709–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bužgová, R.; Kozáková, R.; Bar, M. The effect of neuropalliative care on quality of life and satisfaction with quality of care in patients with progressive neurological disease and their family caregivers: An interventional control study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weru, J.; Gatehi, M.; Musibi, A. Randomized control trial of advanced cancer patients at a private hospital in Kenya and the impact of dignity therapy on quality of life. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudilla, D.; Barreto, P.; Oliver, A.; Galiana, L. Estudio comparativo de la eficacia del counselling y de la terapia de la dignidad en pacientes paliativos. Med. Paliativa 2017, 24, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manookian, A.; Zaki-Nejad, M.; Nikbakht-Nasrabadi, A.; Shamshiri, A. The effect of dignity therapy on the quality of life of patients with cancer receiving palliative care. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2020, 25, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keall, R.M.; Butow, P.N.; Steinhauser, K.E.; Clayton, J.M. Nurse-facilitated preparation and life completion interventions are acceptable and feasible in the australian palliative care setting: Results from a phase 2 trial. Cancer Nurs. 2013, 36, E39–E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, B.; Sun, V.; Hurria, A.; Cristea, M.; Raz, D.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Reckamp, K.; Williams, A.C.; Borneman, T.; Uman, G.; et al. Interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with lung cancer. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2015, 50, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Hannon, B.; Leighl, N.; Oza, A.; Moore, M.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowther, K.; Selman, L.; Simms, V.; Gikaara, N.; Ahmed, A.; Ali, Z.; Kariuki, H.; Sherr, L.; Higginson, I.J.; Harding, R. Nurse-led palliative care for HIV-positive patients taking antiretroviral therapy in Kenya: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2015, 2, e328–e334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.A.; Ang, B.T.; Lam, C.L.; Loh, E.C.; Zainuddin, S.I.; Capelle, D.P.; Ng, C.G.; Lim, P.K.; Khor, P.Y.; Lim, J.Y.; et al. The effect of 5-min mindfulness of love on suffering and spiritual quality of life of palliative care patients: A randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2021, 30, e13456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermandere, M.; Warmenhoven, F.; Van Severen, E.; De Lepeleire, J.; Aertgeerts, B. Spiritual history taking in palliative home care: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitbart, W.; Pessin, H.; Rosenfeld, B.; Applebaum, A.J.; Lichtenthal, W.G.; Li, Y.; Saracino, R.M.; Marziliano, A.M.; Masterson, M.; Tobias, K.; et al. Individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for the treatment of psychological and existential distress: A randomized controlled trial in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 2018, 124, 3231–3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rego, F.; Gonçalves, F.; Moutinho, S.; Castro, L.; Nunes, R. The influence of spirituality on decision-making in palliative care outpatients: A cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat. Care 2020, 19, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo Elvira, T.; Ibáñez Del Prado, C.; Cruzado, J.A. Psychological well-being in palliative care: A systematic review. Omega 2021, 87, 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaar, E.A.; Hallit, S.; Hajj, A.; Aaraj, R.; Kattan, J.; Jabbour, H.; Khabbaz, L.R. Evaluating the impact of spirituality on the quality of life, anxiety, and depression among patients with cancer: An observational transversal study. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 2581–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolf, S.; Fisher, P. The role of dance movement psychotherapy for expression and integration of the self in palliative care. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2015, 21, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, B.P.; Penrose-Thompson, P. Music as a Therapeutic Resource in End-of-Life Care. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2012, 14, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, S.C.T.; Matuoka, J.Y.; Yamashita, C.C.; Salvetti, M.d.G. Efectos de la terapia de dignidad en pacientes terminales: Una revisión sistemática. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2016, 50, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudilla, D.; Galiana, L.; Oliver, A.; Barreto, P. Comparando el asesoramiento y las terapias de dignidad en pacientes de atención domiciliaria: Un estudio piloto. Palliat. Support. Care 2016, 14, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).