Highlights

What are the main findings?

- In patients with isolated locoregional recurrence after curative gastrectomy, salvage re-gastrectomy was associated with significantly improved overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone after propensity-score matching.

- Salvage re-gastrectomy achieved superior locoregional disease control, with no local or peritoneal recurrences observed and no perioperative mortality in the matched cohort.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- A longer disease-free interval emerged as a pragmatic clinical marker identifying patients most likely to benefit from surgical salvage, supporting its use as a surrogate of tumor biology in treatment selection.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Recurrence after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer remains common, and treatment options are limited. In selected patients with isolated locoregional relapse, salvage re-gastrectomy may provide durable disease control. This study compared outcomes of salvage re-gastrectomy and chemotherapy for isolated locoregional recurrence. Methods: We reviewed 500 consecutive gastrectomies performed between 2010 and 2024. In total, 66 patients (12.8%) developed isolated locoregional recurrence after previous R0 resection: 25 underwent salvage re-gastrectomy, and 41 received chemotherapy. Propensity-score matching (intended 1:2) was used to balance clinical and pathologic variables, yielding 42 patients (17 surgery, 25 chemotherapy). The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS) from recurrence diagnosis; secondary endpoints included perioperative outcomes and patterns of treatment failure. Results: There were no 30-, 60-, or 90-day deaths after salvage re-gastrectomy. Overall mortality was lower in the surgical group (41.2%) compared with chemotherapy (80.0%; p = 0.010). Salvage re-gastrectomy was independently associated with better OS (HR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02–0.87, and p = 0.035). A longer disease-free interval correlated strongly with survival (ρ = 0.80 and p < 0.001). Surgical patients experienced fewer local (0% vs. 52%) and peritoneal (0% vs. 20%) recurrences. Conclusions: For carefully selected patients with late, isolated locoregional recurrence, salvage re-gastrectomy is feasible and associated with longer survival and improved local control compared with chemotherapy alone. Larger prospective studies are warranted.

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer remains a major global health burden, ranking as the fifth most common malignancy worldwide and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death, with approximately 1.1 million new cases and 770,000 deaths annually [1,2]. Histologically, adenocarcinoma accounts for over 90% of gastric malignancies. The Lauren classification distinguishes intestinal-type, diffuse-type, and mixed subtypes, each with distinct molecular profiles, clinical behavior, and prognostic implications. Five-year survival rates range from 70 to 90% for localized disease to less than 5% for metastatic presentations, with overall survival in Western populations remaining approximately 30–35%.

Standard curative treatment for resectable gastric cancer consists of radical gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy, combined with perioperative systemic therapy. Current evidence supports perioperative FLOT (fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel) chemotherapy, which demonstrated superior survival compared to prior anthracycline-based regimens in the FLOT4 trial [3]. Despite optimal multimodal treatment, recurrence remains common.

Even after curative-intent gastrectomy, 40–60% of patients develop recurrence, most often within the peritoneal or locoregional compartments [4]. Standard management relies on systemic therapy, yet results remain modest [5,6]. With growing experience in oligometastatic disease, aggressive local control in selected cases has shown survival benefit in other malignancies [7].

Experience with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy in gastric cancer supports the potential value of regional control in select cases [8,9]. Advances in perioperative care and modern systemic therapy have lowered surgical risk and improved disease control, allowing more patients to safely undergo complex operations when indicated [1,3].

A key question that remains is which patients with locoregional recurrence after R0 resection benefit from salvage re-gastrectomy. The interval between primary surgery and recurrence may reflect tumor biology, with later recurrences suggesting a more indolent course potentially amenable to local treatment [10]. Emerging tools such as circulating tumor DNA and immune response profiling may further refine patient selection [11,12].

Despite growing experience with cytoreductive approaches in peritoneal disease, evidence specifically addressing salvage gastrectomy for isolated locoregional recurrence remains limited to small, uncontrolled retrospective series. Critically, no comparative study has systematically evaluated whether salvage re-gastrectomy offers a survival advantage over systemic chemotherapy alone in this clinical setting, nor have factors predicting surgical benefit been rigorously examined using matched analysis.

Currently, systemic chemotherapy remains the standard treatment for recurrent gastric cancer, and salvage re-gastrectomy is not routinely offered due to concerns regarding technical complexity, perioperative morbidity, and uncertain oncologic benefit. However, for patients with isolated locoregional recurrence without peritoneal or distant dissemination, the role of salvage re-gastrectomy has not been adequately defined. In this study, we compared outcomes of patients who underwent salvage re-gastrectomy with a propensity-matched cohort treated with chemotherapy alone, aiming to determine whether surgical salvage offers acceptable outcomes and a survival advantage, and whether a longer disease-free interval identifies patients most likely to benefit from this approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study of all gastrectomies performed between 2010 and 2024, using a prospectively maintained institutional database. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of informed consent.

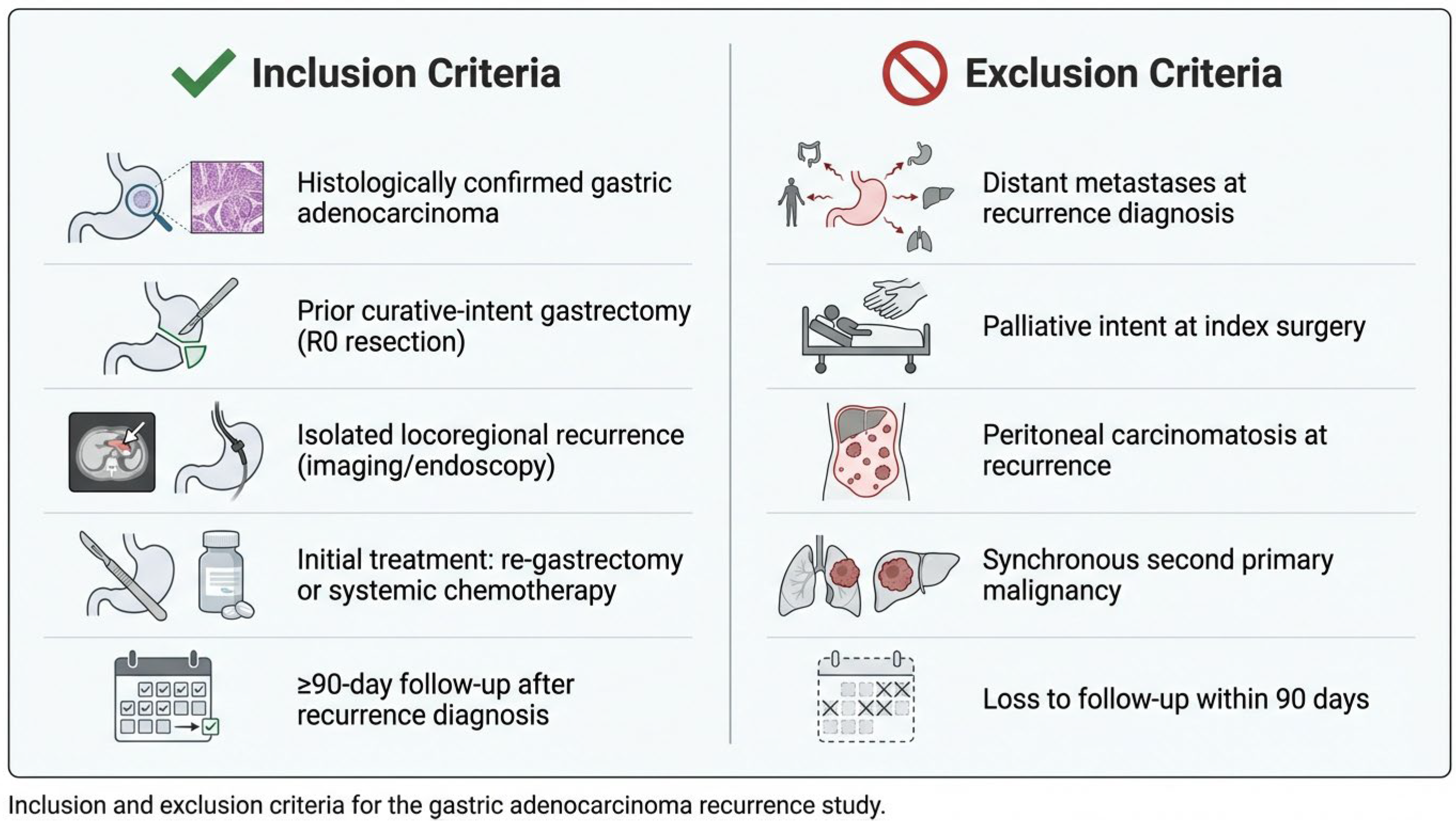

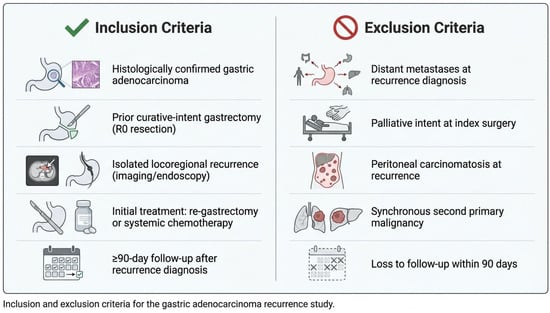

Patient selection criteria are summarized in Figure 1. Isolated locoregional recurrence was defined as recurrent disease confined to (1) the gastric remnant or anastomotic site, (2) regional lymph node stations within the D1/D2 nodal basins, or (3) local soft tissue involvement, without evidence of peritoneal dissemination or distant organ metastases on computed tomography, PET-CT (when available), or diagnostic laparoscopy. Peritoneal cytology and staging laparoscopy were performed selectively based on imaging findings and clinical suspicion. Equivocal findings were adjudicated through multidisciplinary tumor board review.

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Treatment Protocols

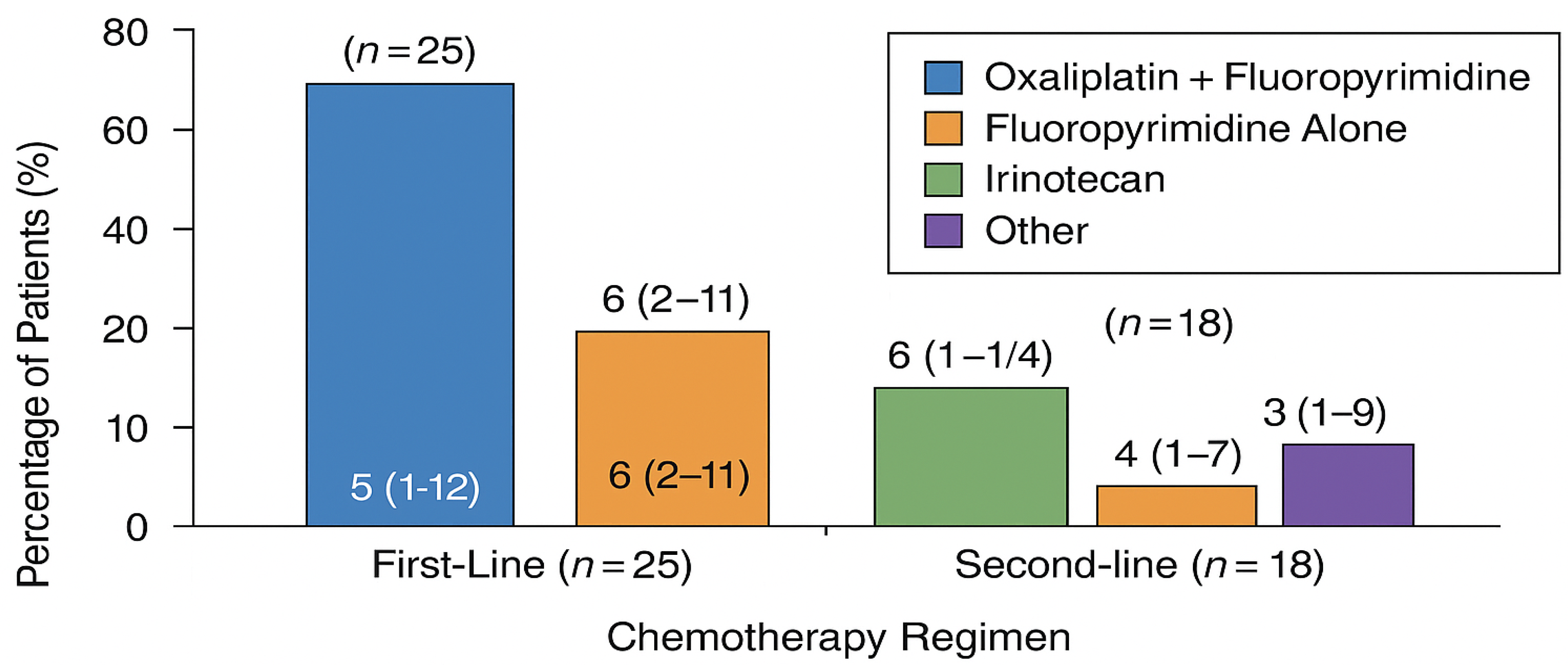

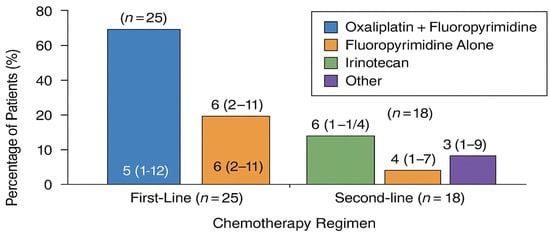

Chemotherapy: Systemic therapy regimens were selected at the discretion of the treating oncologist based on prior treatment history, performance status, and molecular tumor characteristics. First-line regimens included fluoropyrimidine-platinum combinations (FOLFOX, CAPOX, or cisplatin-based), taxane-containing regimens, and ramucirumab combinations for second-line therapy. Regimen details are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Chemotherapy regimens in the matched cohort (n = 25).

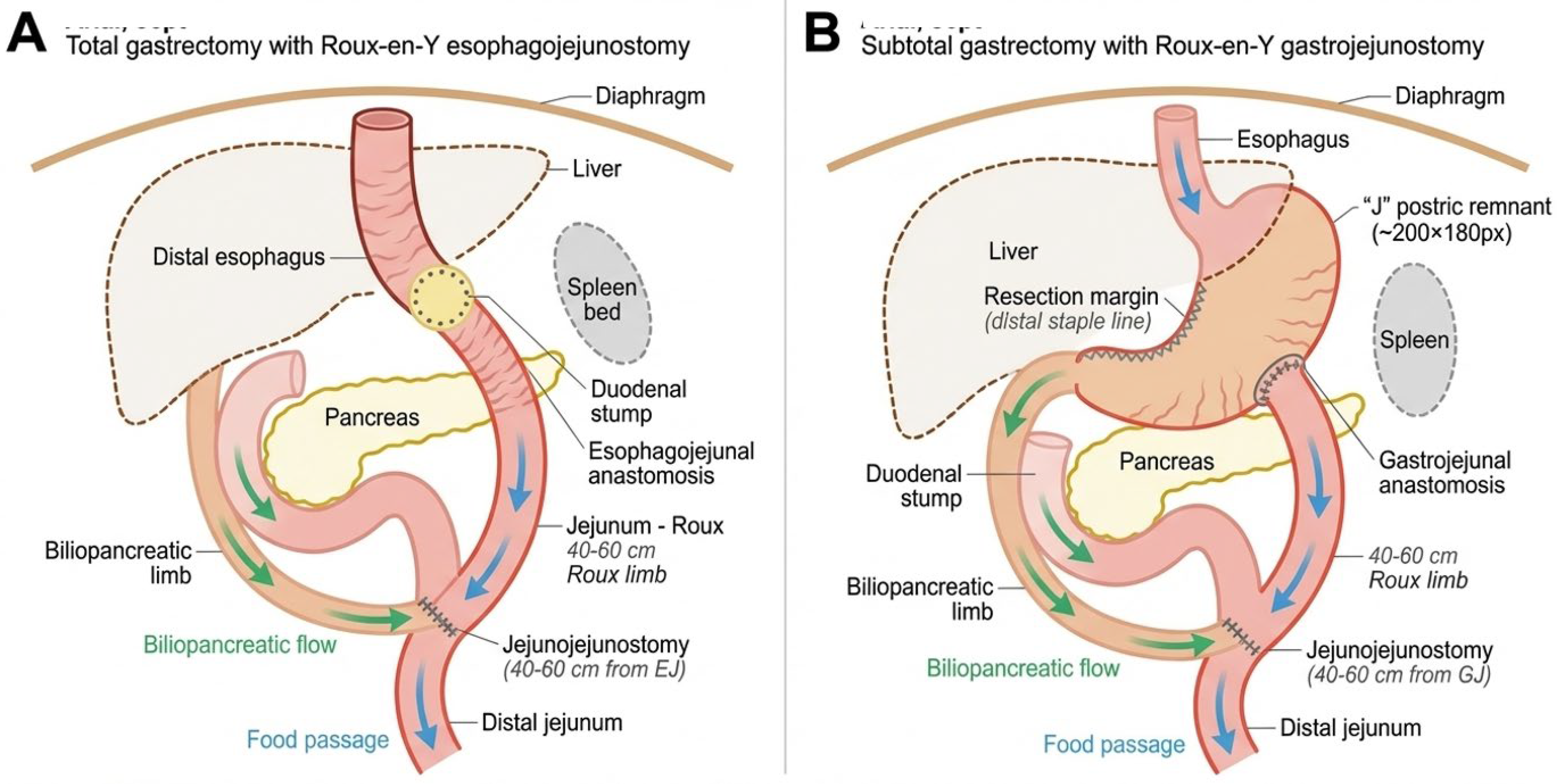

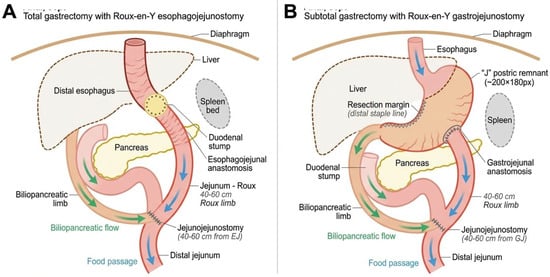

Surgery: All salvage re-gastrectomy procedures were performed by a dedicated upper gastrointestinal surgical team with high-volume gastric cancer experience (>150 gastrectomies annually). The surgical approach (open or laparoscopic) was determined based on tumor location, extent of prior surgery, and anticipated adhesions. Lymphadenectomy extent (D1 or D2) followed the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association guidelines. Digestive continuity was restored using Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy (after total gastrectomy) or gastrojejunostomy (after subtotal gastrectomy). Anastomoses were performed using circular staplers (25 mm) with reinforcing single-layer absorbable sutures, or a hand-sewn double-layer technique when stapling was not feasible. See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Surgical reconstruction techniques following salvage re-gastrectomy. (A) Total gastrectomy with Roux–en–Y esophagojejunostomy. The distal esophagus is anastomosed to a 40–60 cm Roux limb using a 25 mm circular stapler. The biliopancreatic limb drains into the Roux limb via a side-to-side jejunojejunostomy. (B) Subtotal gastrectomy with Roux–en–Y gastrojejunostomy. The gastric remnant is anastomosed to the Roux limb, preserving proximal gastric function. Blue arrows indicate food passage; green arrows indicate biliopancreatic secretion flow.

2.3. Endpoints

The main study variable was the initial treatment approach for locoregional recurrence, categorized as either salvage re-gastrectomy (with or without lymphadenectomy or combined organ resection) or systemic chemotherapy. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS), measured from the date of recurrence diagnosis; patients alive at last follow-up were censored.

Secondary outcomes included short-term treatment-related mortality assessed at 30, 60, and 90 days for surgery (and 120 days for chemotherapy). These intervals were selected to align with internationally standardized perioperative outcome reporting used in major surgical registries (ACS-NSQIP and JGCA) and published gastric cancer series, enabling direct comparison with benchmark data. The 30-day window captures immediate perioperative complications, the 60-day window captures delayed complications (e.g., anastomotic leak and/or pulmonary embolism), and the 90-day window provides a comprehensive treatment-related mortality assessment while minimizing disease-related deaths. The extended 120-day window for chemotherapy reflects the potential for delayed treatment-related toxicity. Disease-free survival is measured from treatment initiation, postoperative or treatment-related complications (graded by the Clavien–Dindo classification for surgery and CTCAE for chemotherapy, where available), 30-day readmission, and patterns of treatment failure (local, regional nodal, peritoneal, or distant). Death was considered a competing event when analyzing patterns of failure. The longer window for chemotherapy reflects delayed treatment-related toxicity.

2.4. Data Collection and Variables

Data on demographics, comorbidities, primary tumor characteristics, index operation details, recurrence features, and treatment information were obtained from the institutional MDClone platform and electronic medical records. The extent of lymph node dissection (D2) was defined according to the Japanese Classification [13]. Missing data affected fewer than 10% of cases for any given variable and were addressed using multiple imputation with 20 datasets.

2.5. Propensity Score and Statistical Analysis

To reduce confounding by indication, each patient’s likelihood of undergoing salvage re-gastrectomy was estimated using logistic regression across predefined covariates, including age, sex, BMI, ECOG status, time to recurrence, pathologic T and N stage, tumor size, differentiation, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, signet-ring histology, receipt of neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy, and treatment era. Patients were matched using nearest-neighbor 1:2 matching without replacement and a caliper width of 0.2 standard deviations of the logit. Because not all surgical cases had two suitable chemotherapy counterparts, the final matched cohort achieved a ratio slightly below 1:2.

Covariate balance was evaluated using standardized mean differences (SMDs); SMD < 0.10 was considered excellent and < 0.25 was considered acceptable. Survival analyses were performed using Kaplan–Meier estimates, log-rank tests, and Cox proportional hazards models with robust standard errors and stratification or weighting as appropriate. To address potential non-proportional hazards, restricted mean survival time (RMST) was summarized at fixed time horizons. Competing-risk analyses were used to assess patterns of treatment failure, and time-specific absolute risk differences informed exploratory numbers needed to treat or harm (NNT/NNH). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Time-origin sensitivity analysis. To address potential immortal-time bias arising from differential time-to-treatment between groups, overall survival was also examined from treatment initiation (date of salvage re-gastrectomy for the surgical group and date of first chemotherapy cycle for the chemotherapy group) in addition to the primary analysis from recurrence diagnosis.

2.6. Ethics

The study adhered to institutional policies and the Declaration of Helsinki; the IRB approved the protocol and waived informed consent due to minimal risk.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort

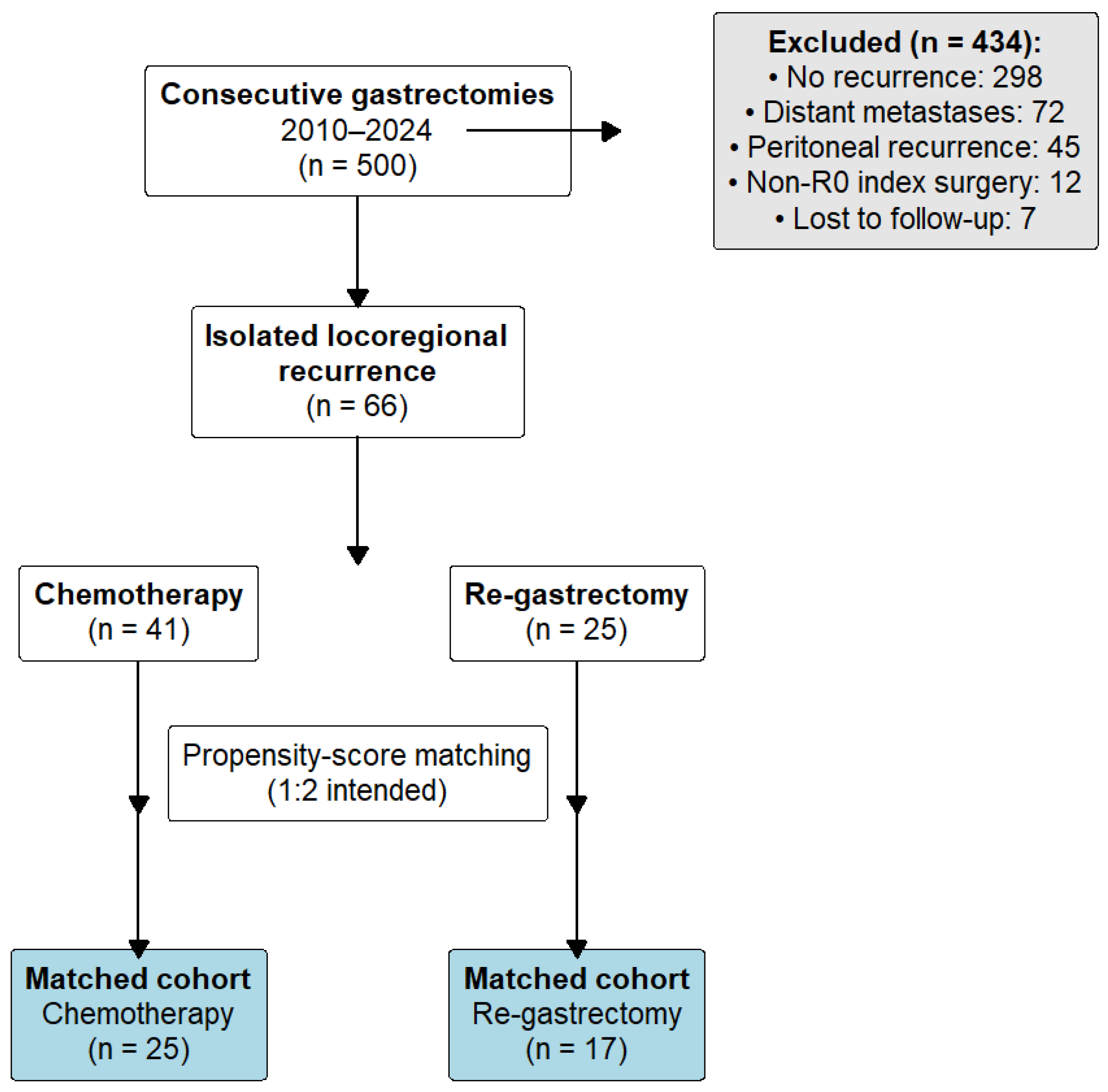

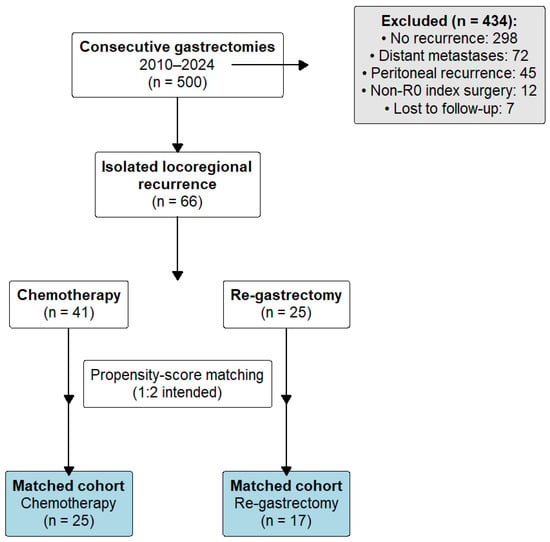

Of 500 gastrectomies performed between 2010 and 2024, 66 patients met criteria for isolated locoregional recurrence after prior R0 resection (Figure 4). In total, 41 received chemotherapy, and 25 underwent salvage re-gastrectomy as initial treatment.

Figure 4.

Patient flow diagram. Of 500 consecutive gastrectomies performed for gastric adenocarcinoma between 2010 and 2024, 434 patients were excluded: 298 had no recurrence, 72 developed distant metastases, 45 had peritoneal recurrence, 12 had non-R0 primary gastrectomy, and 7 were lost to follow-up. The remaining 66 patients with isolated locoregional recurrence were allocated to chemotherapy (n = 41) or salvage re-gastrectomy (n = 25). After 1:2 propensity-score matching, 42 patients (25 chemotherapy, 17 surgery) comprised the primary analysis cohort.

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

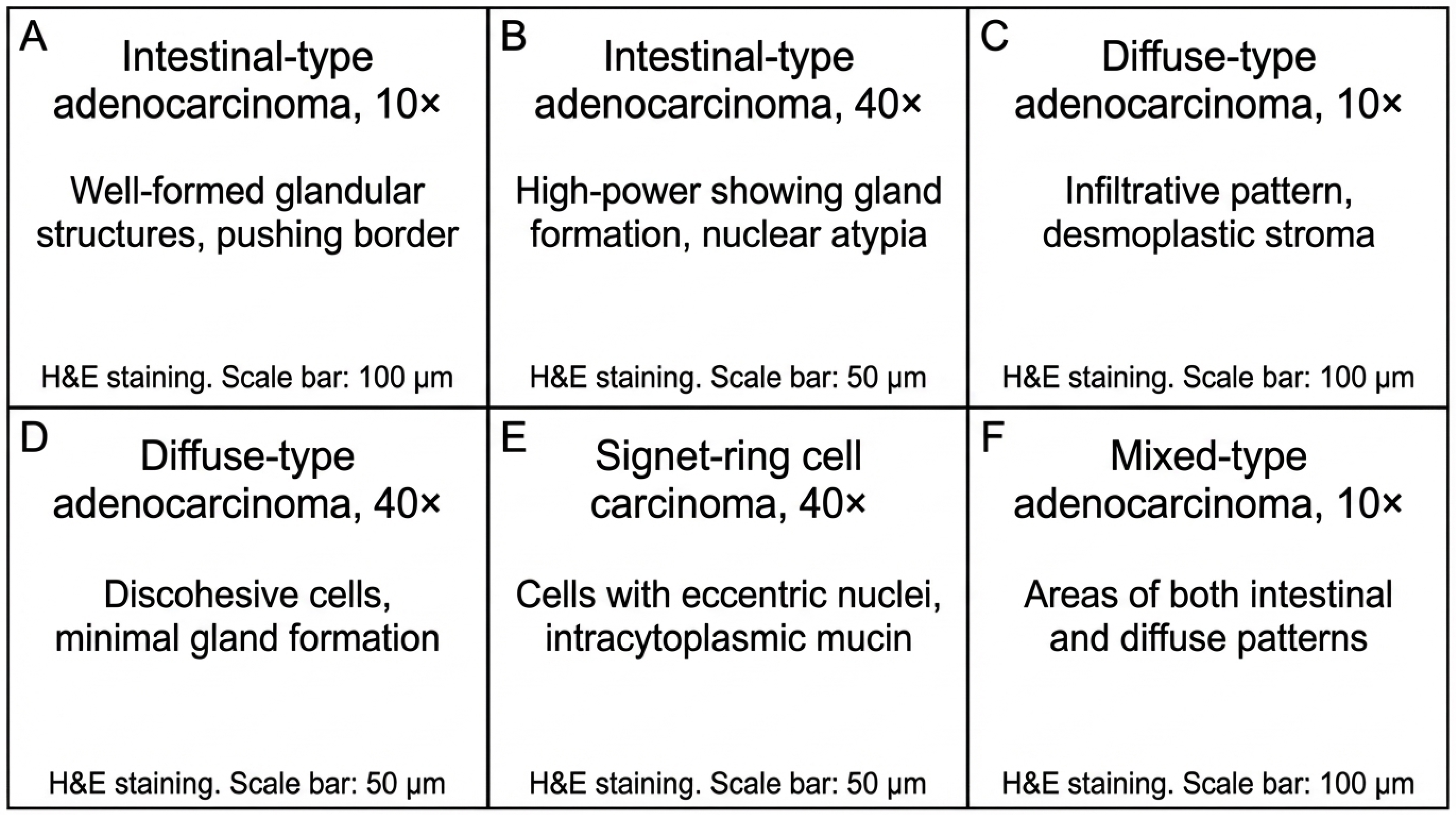

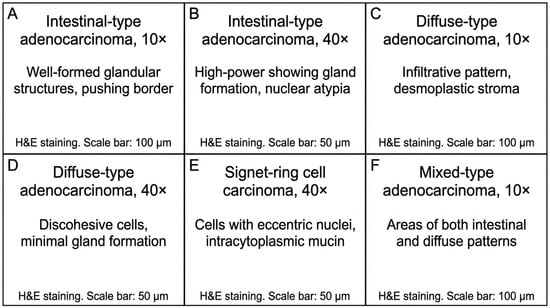

Before matching, surgical patients had lower BMI and a different distribution of performance status, while age and comorbidities were similar (Table 1). Propensity-score matching produced 42 patients (25 chemotherapy, 17 surgery) with improved balance, though ECOG performance status remained uneven (100% vs. 76%) (Table 2). After matching, surgical patients were more often T3 and exclusively N0 (100% vs. 72%; p = 0.024); tumor differentiation was comparable between groups (Table 3, Figure 5).

Table 1.

Demographics and comorbidities before propensity score matching.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics after propensity score matching.

Table 3.

Disease characteristics after propensity score matching.

Figure 5.

Representative histopathological findings in gastric adenocarcinoma from the study cohort. (A,B) Intestinal-type adenocarcinoma showing well-differentiated glandular architecture (H&E; (A): 10×, (B): 40×). (C,D) Diffuse-type adenocarcinoma demonstrating infiltrative growth pattern with desmoplastic stromal reaction and poorly cohesive tumor cells (H&E; (C): 10×, (D): 40×). (E) Signet-ring cell carcinoma with characteristic intracytoplasmic mucin vacuoles displacing the nucleus (H&E, 40×). (F) Mixed-type adenocarcinoma exhibiting both glandular and diffuse components (H&E, 10×). Scale bars: 100 μm (A,C,F) and 50 μm (B,D,E).

3.3. Early Outcomes and Patterns of Failure

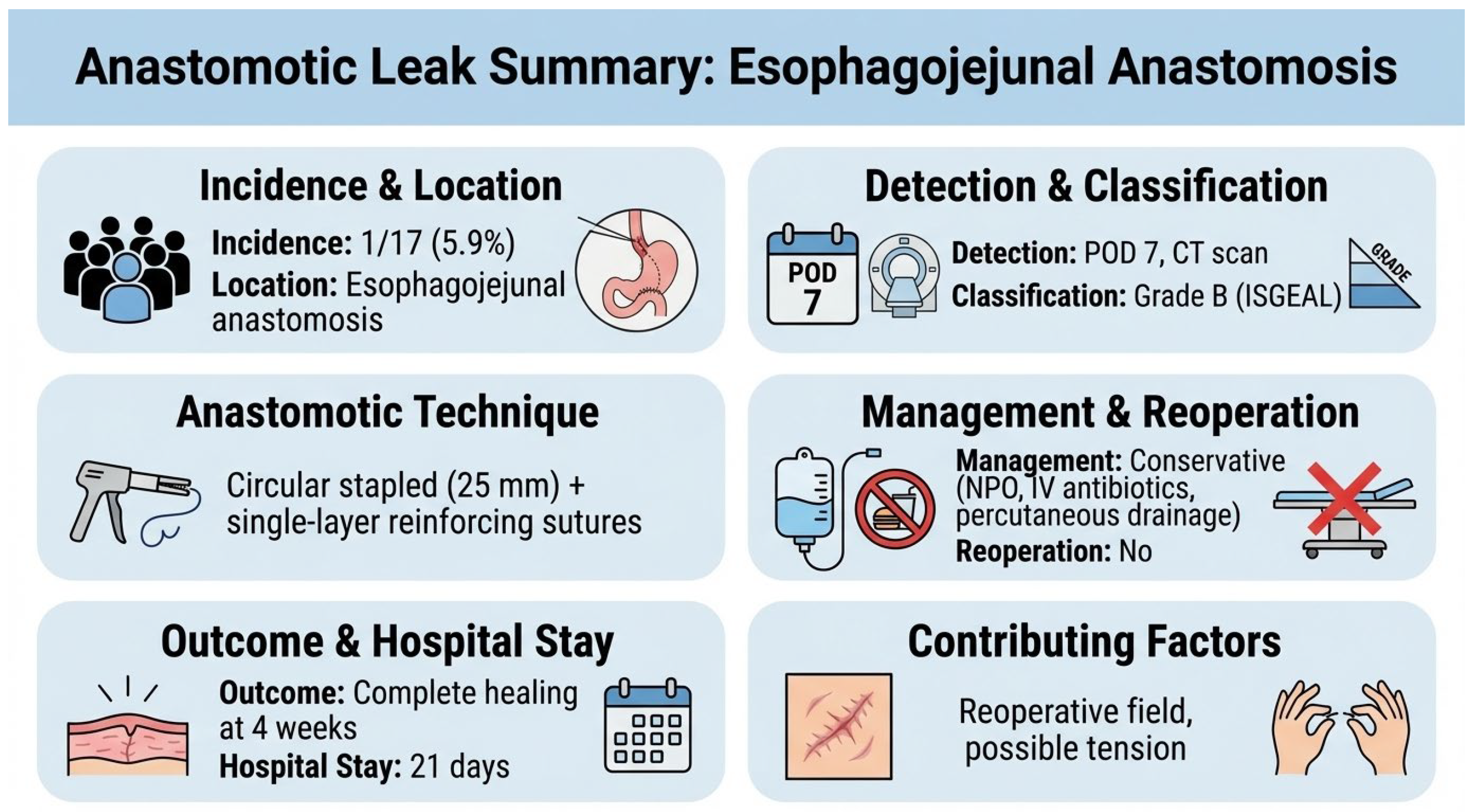

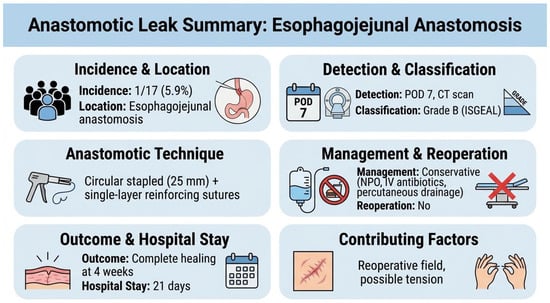

There were no 30-, 60-, or 90-day deaths in either group. Severe complications (Clavien–Dindo ≥ III) occurred in 5.9% after salvage re-gastrectomy and 16.0% after chemotherapy (p = 0.384). One patient (5.9%) in the surgical group developed a contained anastomotic leak at the esophagojejunal anastomosis on postoperative day 7, identified by a CT scan performed for fever workup. The leak was classified as Grade B per the International Study Group definition (radiologically evident, clinically manageable without reoperation). Management consisted of nil per os, broad-spectrum antibiotics (piperacillin-tazobactam), and CT-guided percutaneous drainage. The patient recovered with complete healing confirmed on water-soluble contrast study at 4 weeks, and was discharged on postoperative day 21. The anastomosis had been performed using a 25 mm circular stapler with reinforcing single-layer seromuscular sutures (3-0 absorbable). Contributing factors may have included tension at the anastomosis and the reoperative surgical field with adhesions, though no definitive cause was identified (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The anastomotic leak case description.

Thirty-day readmission was 0% in the surgical group versus 16.0% in the chemotherapy group. Overall mortality was lower after salvage re-gastrectomy (41.2% vs. 80.0%; p = 0.010). Chemotherapy-related adverse events are detailed in Supplementary Table S1.

Patterns of failure favored surgery: local recurrence was 0% vs. 52.0% (p < 0.001), peritoneal recurrence was 0% vs. 20.0% (p = 0.049), and distant recurrence was 11.8% vs. 44.0% (p = 0.029). Of note, no difference was observed in regional nodal recurrence, which was 17.6% vs. 16.0% (ns) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Early outcomes, survival, and patterns of failure after propensity score matching.

3.4. Multivariable Analyses (Matched Cohort)

In the multivariable Cox proportional hazards model of the matched cohort, treatment with salvage re-gastrectomy was associated with a significantly lower hazard of death compared with chemotherapy (HR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02–0.87; p = 0.035). Time to recurrence was inversely associated with mortality (per-month HR 0.98; p = 0.042). Age, sex, and body mass index were not significantly associated with overall survival (Table 5).

Table 5.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis after propensity score matching.

3.5. Surgical Details

Among the 17 patients who underwent salvage re-gastrectomy, operations included total gastrectomy in 52.9%, subtotal gastrectomy in 35.3%, and completion gastrectomy in 11.8%. D2 lymphadenectomy was performed in 82.4% of cases, and R0 resection was achieved in all patients. The mean operative time was 4.8 ± 1.2 h, and the median estimated blood loss was 250 mL (interquartile range, 150–400) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Salvage re-gastrectomy group surgical characteristics (n = 17).

Of the 17 patients who underwent salvage re-gastrectomy, 11 (64.7%) received adjuvant systemic therapy following surgery. Adjuvant chemotherapy alone was administered to 9 patients (52.9%), chemoradiation to 1 patient (5.9%), and 1 patient (5.9%) received targeted therapy (trastuzumab) based on HER2-positive status. Six patients (35.3%) did not receive adjuvant therapy due to patient preference (n = 2), prolonged postoperative recovery (n = 2), early recurrence precluding adjuvant treatment (n = 1), or physician decision based on comorbidities (n = 1). See Table S5.

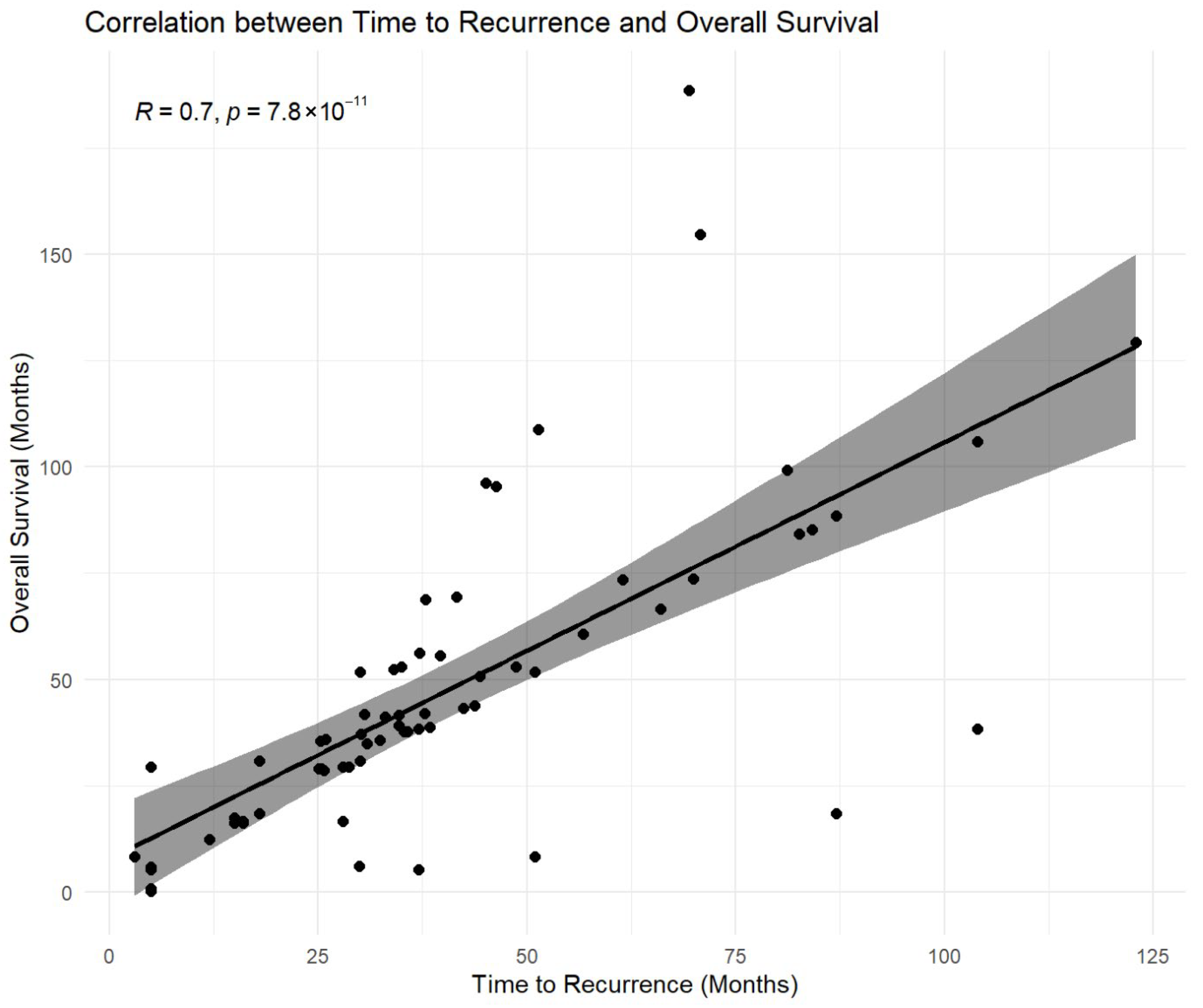

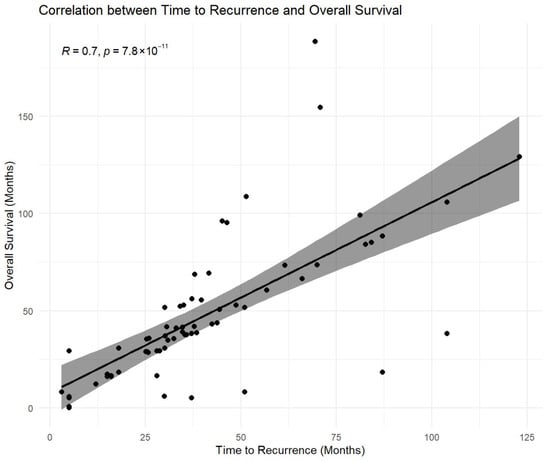

3.6. Time to Recurrence and Outcomes

The time from index gastrectomy to recurrence was strongly associated with overall survival, with a high positive correlation observed (Spearman ρ = 0.800; p < 0.001) (Figure 7 and Supplementary Table S2). Within the salvage re-gastrectomy subgroup, time to recurrence was also strongly correlated with post-resection disease-free survival (Spearman ρ = 0.818 and p < 0.001) and demonstrated a strong linear association with disease-free survival on regression analysis (R2 = 0.910 and p < 0.001) (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 7.

Association between time to recurrence and overall survival. Scatterplot illustrating the relationship between time from index gastrectomy to locoregional recurrence and overall survival (OS) measured from recurrence diagnosis. A strong positive monotonic association was observed (Pearson correlation r = 0.70; p < 0.001). The fitted line is shown for visual reference only. Correlation analysis is descriptive and exploratory and does not account for right-censoring of survival data. Because overall survival includes time to recurrence as a component, this association may partly reflect structural dependence and should not be interpreted as causal. Accordingly, inferential conclusions regarding survival were based on propensity-matched and multivariable time-to-event analyses.

3.7. Time-to-Treatment Interval

Mean time from recurrence diagnosis to treatment initiation was 18.2 days in the salvage surgery group and 12.4 days in the chemotherapy group (p = 0.31).

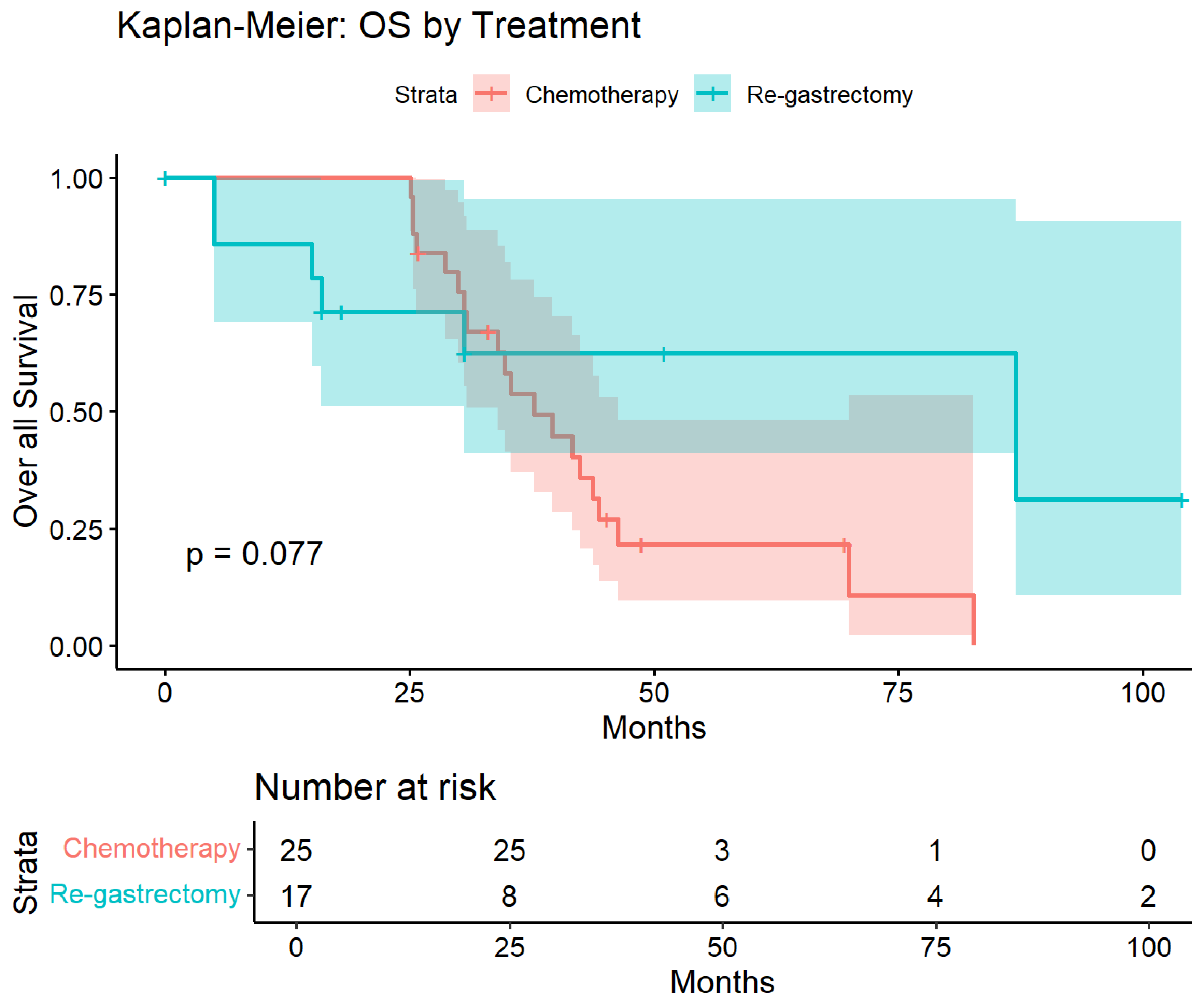

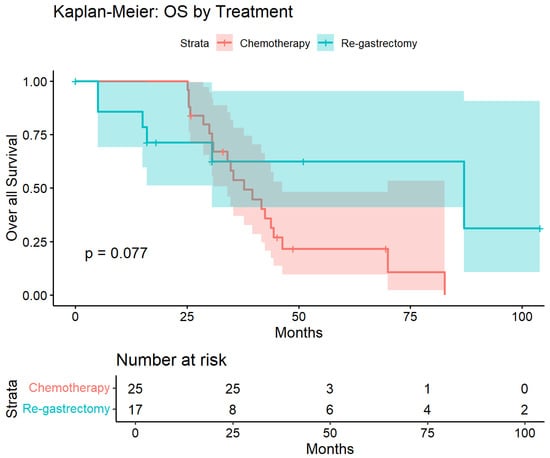

3.8. Overall Survival Analysis

Kaplan–Meier survival curves demonstrated separation favoring salvage re-gastrectomy over chemotherapy throughout the follow-up period (Figure 8). Median overall survival was not reached in the surgical group compared with 35.3 months in the chemotherapy group. At 50 months, survival probability was 62% in the salvage re-gastrectomy group versus 25% in the chemotherapy group. The unadjusted log-rank test showed a trend toward improved survival with surgery that did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.077), likely reflecting limited power due to small sample size. However, after multivariable adjustment for age, sex, BMI, and time to recurrence, salvage re-gastrectomy was independently associated with significantly improved overall survival (HR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02–0.87; p = 0.035; Table 5).

Figure 8.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival in the propensity-matched cohort. Overall survival from recurrence diagnosis in patients treated with salvage re-gastrectomy (n = 17, blue) versus chemotherapy alone (n = 25, red). Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Log-rank p = 0.077. After multivariable adjustment, salvage re-gastrectomy was associated with significantly improved survival (HR 0.15, 95% CI 0.02–0.87, and p = 0.035). Numbers at risk are shown below.

3.9. Subgroup by Disease-Free Interval

Stratification by disease-free interval (DFS) >24 months versus ≤24 months demonstrated differential outcomes by initial treatment approach (Table 7). Among patients with DFS > 24 months, overall mortality was 33.3% after salvage re-gastrectomy compared with 100% after chemotherapy (number needed to treat [NNT] ≈ 1.5). In patients with DFS ≤ 24 months, mortality was 70.0% after salvage re-gastrectomy versus 100% after chemotherapy (NNT ≈ 3.3). Within the surgical subgroup, median overall survival was 38.40 months for patients with DFS > 24 months compared with 11.25 months for those with DFS ≤ 24 months (p = 0.002).

Table 7.

Subgroup analysis by disease-free survival duration.

3.10. Summary Effect Measures

Across the entire cohort, the number needed to treat (NNT) to prevent one death with salvage re-gastrectomy was 1.9, compared with 2.6 in the propensity-matched cohort. The number needed to harm (NNH) for 90-day mortality in the full cohort was 25; no perioperative deaths occurred in the matched cohort. Corresponding absolute risk differences and derived NNT/NNH estimates are presented in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

4. Discussion

In this propensity-matched analysis, salvage re-gastrectomy for isolated locoregional recurrence was associated with lower overall mortality and superior locoregional control compared with chemotherapy alone, with no perioperative deaths observed in the matched cohort. To mitigate confounding by indication inherent to salvage-surgery cohorts, we emphasized propensity-matched and adjusted analyses and interpreted unmatched survival estimates cautiously. The apparent association between salvage re-gastrectomy and improved outcomes was most pronounced among patients with a longer disease-free interval, a variable intentionally examined as a pragmatic surrogate of tumor biology, consistent with the concept that later recurrences often reflect a more indolent disease course in which definitive local control may translate into survival benefit.

These observations align with the oligometastatic framework and the demonstrated value of aggressive local therapy in limited metastatic disease [7]. In gastric cancer, converging experience with cytoreductive strategies and intraperitoneal approaches supports the principle that regional disease control can be clinically meaningful when tumor biology and technical feasibility align [8,9]. At the same time, contemporary perioperative optimization and advances in systemic therapy have expanded surgical candidacy and improved outcomes, allowing more selective application of complex reoperative strategies [1,3]. In this context, time to recurrence functioned as a biologically informative stratifier in our analysis, consistent with prior data linking later failures to improved prognosis [10]. Emerging tools, including investigational circulating tumor DNA monitoring and immune-response profiling, may further refine selection for surgical or combined multimodality strategies [11,12].

Comparative oncologic context supports a selective approach to salvage surgery. Differences between Eastern and Western outcomes in primary gastric cancer underscore the influence of surgical volume, technique, and systems of care [14], while patterns and timing of recurrence after gastrectomy support the biological plausibility of benefit when disease remains regionally confined [15]. Several retrospective series have specifically examined salvage resection for recurrent gastric cancer. Yoo et al. reported median survival of 19.4 months after re-resection for isolated local or nodal recurrence in 59 patients [16], and Carboni et al. demonstrated comparable outcomes in a Western cohort [17]. Park et al., in 86 patients undergoing salvage re-gastrectomy, observed a mean survival of 15.4 months overall but 37.9 months when complete resection was achieved—albeit with an operative mortality of 10.5%—highlighting both the potential benefit and inherent risk of aggressive surgical salvage [18]. Jung et al. focused on anastomotic recurrence and reported a median survival of 28.1 months with complete versus 5.5 months with incomplete resection, reinforcing R0 resection as the dominant determinant of outcome [19]. Notably, none of these series included a matched non-surgical comparator. Our perioperative safety profile—0% mortality and 5.9% severe morbidity—compares favorably with these historical benchmarks, likely reflecting advances in perioperative optimization and the critical role of complication avoidance in preserving long-term oncologic outcomes [20]. The prognostic implications of positive peritoneal cytology further reinforce the importance of meticulous staging and patient selection when pursuing surgical salvage [21]. Beyond gastric cancer, randomized trials of local therapy in oligometastatic colorectal cancer reinforce that aggressive local control can yield meaningful survival benefits when applied to appropriately selected patients [22]. Nevertheless, direct cross-study comparison is constrained by heterogeneity in recurrence definitions, surgical extent, systemic therapy protocols, and treatment era, and our smaller surgical cohort (n = 17) limits subgroup analyses and contributes to wide confidence intervals.

The favorable perioperative outcomes observed in our surgical cohort—0% 90-day mortality and 5.9% severe morbidity (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III)—merit contextualization, as these results compare favorably with historical benchmarks reporting morbidity rates of 15–30% and mortality up to 10% for salvage gastric surgery. Several factors likely contributed to this safety profile. First, all procedures were performed at a high-volume tertiary center (>150 annual gastrectomies) by a dedicated upper gastrointestinal surgical team with specific expertise in reoperative surgery; published volume-outcome data consistently demonstrate improved outcomes at high-volume centers. Second, patient selection was deliberately restrictive: candidates underwent rigorous multidisciplinary evaluation, including nutritional optimization, cardiopulmonary risk stratification, and staging laparoscopy to exclude occult peritoneal disease, resulting in a cohort biased toward lower operative risk. Third, standardized enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols were employed, including goal-directed fluid therapy, early mobilization, thromboprophylaxis, and structured nutritional support. Finally, the small sample size and selection bias inherent to retrospective analysis may have contributed to favorable outcomes that may not be generalizable to broader populations or lower-volume settings.

The contribution of adjuvant therapy to observed outcomes cannot be isolated in this analysis; 64.7% of surgical patients received postoperative systemic treatment, representing an additional source of heterogeneity between treatment groups and a potential contributor to the survival advantage observed with salvage re-gastrectomy. Postoperative systemic therapy was considered an integral component of multimodality salvage management rather than an independent confounding co-intervention, consistent with contemporary oncological practice. Formal stratified analysis by adjuvant therapy receipt was not feasible given the limited sample size.

4.1. Statistical and Design Limitations

Despite these measures, several limitations inherent to this retrospective analysis should be acknowledged. First, despite propensity-score matching, residual confounding by indication remains likely. Most notably, 100% of surgical patients were classified as N0 at primary gastrectomy compared with 72% in the chemotherapy group (p = 0.024)—a discrepancy that persisted despite matching and likely reflects selection bias toward patients with more favorable tumor biology for surgical candidacy. Node-negative status at primary resection may indicate less aggressive disease with inherently better prognosis, independent of salvage treatment strategy. This imbalance, along with differences in performance status, reflects the intrinsic linkage between tumor biology, recurrence pattern, and eligibility for surgical salvage. To mitigate this, we employed propensity-score matching across predefined clinical and pathological covariates and incorporated time to recurrence as a pragmatic surrogate of tumor biology in adjusted analyses. Formal multivariable adjustment, including nodal status as a covariate, was not statistically feasible because all surgical patients were node-negative, creating complete separation that precludes model estimation; however, this imbalance represents a conservative bias that would underestimate rather than inflate the observed treatment effect. Second, the observational design introduces potential immortal-time bias between recurrence diagnosis and treatment initiation. Overall survival measured from recurrence diagnosis may be influenced by differential intervals to treatment initiation across groups; survival calculated from treatment start would provide a more robust comparison. In our cohort, the mean interval from recurrence diagnosis to treatment initiation was 18.2 days in the surgical group versus 12.4 days in the chemotherapy group (p = 0.31), suggesting this source of bias was limited. Given this near-identical time-to-treatment interval, formal sensitivity analysis recalculating survival from treatment initiation would not materially alter conclusions. Nevertheless, future studies should prioritize survival endpoints calculated from treatment initiation to isolate the treatment effect from the lead-time artifact. Third, summary measures derived from censored survival data, including number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH), are inherently time-dependent and sensitive to the observation period and censoring distribution. The remarkably low NNT values reported (1.5–3.3) should be interpreted strictly as hypothesis-generating and must not be used to overstate predictable benefit in clinical practice; prospective validation is essential before these estimates can inform treatment decisions. Additional limitations include calendar-era heterogeneity across the 2010–2024 study period, sample size constraints, and incomplete staging characterization, including PD-L1 expression, peritoneal cytology, and potential endpoint ascertainment limitations. Finally, as outcomes were derived from a single tertiary referral center, generalizability to lower-volume or non-specialist settings may be limited. Accordingly, these findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and warrant confirmation in multicenter prospective studies with standardized staging, molecular profiling, and predefined selection criteria.

This study was designed as an exploratory hypothesis-generating analysis of a rare clinical scenario. No formal a priori power calculation was performed, given the retrospective design and fixed cohort size determined by the number of eligible patients during the study period. Post hoc power analysis was conducted to contextualize the observed findings: with 17 surgical and 25 chemotherapy patients, observed mortality rates of 41.2% versus 80.0%, and α = 0.05 (two-sided), the study achieved approximately 75% power to detect this difference using Fisher’s exact test. For the Cox regression hazard ratio of 0.15, the wide 95% confidence interval (0.02–0.87) reflects the limited sample size, and the point estimate should be interpreted with appropriate caution.

4.2. Clinical Implications and Next Steps

Within multidisciplinary programs, salvage re-gastrectomy may be considered for carefully selected, medically fit patients with isolated, anatomically resectable locoregional recurrence and a longer disease-free interval. In the present study, patient selection was deliberately restrictive, and analytic emphasis was placed on propensity-matched and adjusted comparisons, with time to recurrence used as a pragmatic surrogate of tumor biology, supporting the clinical relevance of this stratified approach. Future priorities include multicenter prospective registries with standardized staging—including diagnostic laparoscopy and peritoneal cytology—together with integration of molecular profiling and circulating tumor DNA to refine biologic selection beyond clinicopathologic features alone. Methodologically, era-adjusted causal frameworks and time-restricted endpoints such as restricted mean survival time (RMST) should be prioritized to address non-proportional hazards and censoring inherent to salvage-surgery cohorts, alongside the incorporation of patient-reported outcomes. Potential synergies with modern systemic therapy—including FLOT-based perioperative regimens and contemporary targeted and immunotherapy approaches—warrant formal evaluation [3,23,24,25]. Notably, age was not independently associated with overall survival in our cohort, consistent with prior data [26]. In addition, experience in remnant gastric cancer suggests that durable benefit from surgery is achievable in anatomically favorable scenarios, reinforcing a selective aggressive strategy when biological and technical criteria align [27]. Finally, established practice frameworks, such as the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association treatment guidelines, provide pragmatic guardrails for case selection and extent of nodal dissection in this setting [28].

5. Conclusions

In this propensity-matched analysis, salvage re-gastrectomy for isolated locoregional recurrence after curative gastrectomy was feasible, safe, and associated with improved survival and superior locoregional disease control compared with chemotherapy alone. Based on our findings and existing literature, candidates for salvage re-gastrectomy should meet the following criteria: (1) isolated locoregional recurrence (anastomotic, local, or regional nodal) without peritoneal dissemination or distant metastases, confirmed by CT, PET-CT, and/or staging laparoscopy; (2) disease-free interval exceeding 24 months, reflecting favorable tumor biology; (3) technically resectable disease with anticipated R0 margin achievement; (4) adequate performance status (ECOG 0–1); and (5) acceptable operative risk following multidisciplinary evaluation (Figure 9). A longer disease-free interval emerged as a key clinical marker associated with favorable outcomes, supporting its role as a pragmatic surrogate of tumor biology when considering surgical salvage. While limited by the retrospective design and residual confounding, these findings support a selective, multidisciplinary approach to salvage re-gastrectomy and underscore the need for prospective, multicenter studies integrating standardized staging and biological profiling to validate these selection criteria.

Figure 9.

Proposed criteria for salvage re-gastrectomy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/std15010006/s1, Table S1: Correlation analyses between time to recurrence and oncologic outcomes. Table S2: Number Needed to Treat and Number Needed to Harm Analysis. Table S3: Chemotherapy-Related Adverse Events in the Matched Cohort (n = 25). Table S4: Comparison with Published Series of Salvage Surgery for Recurrent Gastric Cancer. Table S5: Adjuvant therapy after re-gastrectomy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.K. and L.O.; methodology, F.K. and A.L.; formal analysis, A.L. and Y.L.; investigation, Y.L., N.M., B.S. and G.L.; data curation, F.K. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, F.K. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, A.L. and F.K.; visualization, A.L.; supervision, L.O. and G.L.; project administration, F.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (Ichilov Hospital). IRB code TLV-0054-25, 12 February 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design and minimal risk to participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions related to patient confidentiality. De-identified data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and subject to institutional and ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ARR | Absolute Risk Reduction |

| ARI | Absolute Risk Increase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CC | Correlation Coefficient |

| CD | Clavien–Dindo Classification |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CTCAE | Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| ctDNA | Circulating tumor DNA |

| DFS | Disease-Free Survival |

| D1/D2 | Extent of Lymphadenectomy According to the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association Classification |

| ECOG | Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group |

| HER2 | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| IHD | Ischemic Heart Disease |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| LN | Lymph Node |

| LOS | Length of Stay |

| MI | Myocardial Infarction |

| MSI | Microsatellite Instability |

| NNH | Number Needed to Harm |

| NNT | Number Needed to Treat |

| OS | Overall Survival |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| R0 | Microscopically Margin-Negative Resection |

| RMST | Restricted Mean Survival Time |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SMD | Standardized Mean Difference |

References

- Kim, I.-H.; Kang, S.J.; Choi, W.; Na Seo, A.; Eom, B.W.; Kang, B.; Kim, B.J.; Min, B.-H.; Tae, C.H.; Choi, C.I.; et al. Korean Practice Guidelines for Gastric Cancer 2024. J. Gastric Cancer 2025, 25, 5–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Batran, S.E.; Homann, N.; Pauligk, C.; Goetze, T.O.; Meiler, J.; Kasper, S.; Kopp, H.G.; Mayer, F.; Haag, G.M.; Luley, K.; et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel versus fluorouracil or capecitabine plus cisplatin and epirubicin for locally advanced, resectable gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4): A randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 1948–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolverato, G.; Ejaz, A.; Kim, Y.; Squires, M.H.; Poultsides, G.A.; Fields, R.C.; Schmidt, C.; Weber, S.M.; Votanopoulos, K.; Maithel, S.K.; et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence after curative intent resection for gastric cancer: A United States multi-institutional analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014, 219, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van Cutsem, E.; Moiseyenko, V.M.; Tjulandin, S.; Majlis, A.; Constenla, M.; Boni, C.; Rodrigues, A.; Fodor, M.; Chao, Y.; Voznyi, E.; et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: A report of the V325 Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006, 24, 4991–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, Y.J.; Van Cutsem, E.; Feyereislova, A.; Chung, H.C.; Shen, L.; Sawaki, A.; Lordick, F.; Ohtsu, A.; Omuro, Y.; Satoh, T.; et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): A phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010, 376, 687–697. [Google Scholar]

- Palma, D.A.; Olson, R.; Harrow, S.; Gaede, S.; Louie, A.V.; Haasbeek, C.; Mulroy, L.; Lock, M.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Yaremko, B.P.; et al. Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy versus standard of care palliative treatment in patients with oligometastatic cancers (SABR-COMET): A randomised, phase 2, open-label trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 2051–2058. [Google Scholar]

- Glehen, O.; Gilly, F.N.; Boutitie, F.; Bereder, J.M.; Quenet, F.; Sideris, L.; Mansvelt, B.; Lorimier, G.; Msika, S.; Elias, D.; et al. Toward curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonovarian origin by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: A multi-institutional study of 1,290 patients. Cancer 2010, 116, 5608–5618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.J.; Huang, C.Q.; Suo, T.; Mei, L.J.; Yang, G.L.; Cheng, F.L.; Zhou, Y.-F.; Xiong, B.; Yonemura, Y.; Li, Y. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: Final results of a phase III randomized clinical trial. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 18, 1575–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jin, X.; Liu, P.; Hong, W. Time to local recurrence as a predictor of survival in unrecetable gastric cancer patients after radical gastrectomy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 89203–89213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gao, J.; Wang, H.; Zang, W.; Li, B.; Rao, G.; Li, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Dong, B.; Lu, Z.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA functions as an alternative for tissue to overcome tumor heterogeneity in advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 1881–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Cristescu, R.; Bass, A.J.; Kim, K.M.; Odegaard, J.I.; Kim, K.; Liu, X.Q.; Sher, X.; Jung, H.; Lee, M.; et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1449–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 2011, 14, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, V.E.; Song, K.Y.; Park, C.H.; Jacks, L.M.; Gonen, M.; Shah, M.; Coit, D.G.; Brennan, M.F. Comparison of gastric cancer survival following R0 resection in the United States and Korea using an internationally validated nomogram. Ann. Surg. 2010, 251, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, M.; Kojima, K.; Inokuchi, M.; Kato, K.; Sugita, H.; Kawano, T.; Sugihara, K. Patterns, timing and risk factors of recurrence of gastric cancer after laparoscopic gastrectomy: Reliable results following long-term follow-up. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2014, 40, 1376–1382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yoo, C.H.; Noh, S.H.; Shin, D.W.; Choi, S.H.; Min, J.S. Recurrence following curative resection for gastric carcinoma. Br. J. Surg. 2000, 87, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carboni, F.; Lepiane, P.; Santoro, R.; Lorusso, R.; Mancini, P.; Carlini, M.; Santoro, E. Treatment for isolated loco-regional recurrence of gastric adenocarcinoma: Does surgery play a role? World J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 11, 7014–7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Lee, C.H.; Park, C.H.; Kim, W.; Ahn, C.J.; Lim, G.W.; Park, W.B.; Kim, S.N.; Kim, I.C. Reoperation of Recurrent Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2001, 33, 478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.J.; Cho, J.H.; Shin, S.; Shim, Y.M. Surgical treatment of anastomotic recurrence after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Korean J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2014, 47, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.R.; Kim, S.E.; Jeong, O. The Impact of Different Types of Complications on Long-Term Survival After Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. J. Gastric Cancer 2023, 23, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezhir, J.J.; Shah, M.A.; Jacks, L.M.; Brennan, M.F.; Coit, D.G.; Strong, V.E. Positive peritoneal cytology in patients with gastric cancer: Natural history and outcome of 291 patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2010, 17, 3173–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruers, T.; Punt, C.; Van Coevorden, F.; Pierie, J.P.E.N.; Borel-Rinkes, I.; Ledermann, J.A.; Poston, G.; Bechstein, W.; Lentz, M.A.; Mauer, M.; et al. Radiofrequency ablation combined with systemic treatment versus systemic treatment alone in patients with non-resectable colorectal liver metastases: A randomized EORTC Intergroup phase II study (EORTC 40004). Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2619–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Batran, S.E.; Pauligk, C.; Götze, T.O. Perioperative chemotherapy for gastric cancer in FLOT4—Authors’ reply. Lancet 2020, 395, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, M.U.; Naqvi, S.A.A.; Jajja, S.A.; Raina, A.; Afzal, M.U.; Faisal, K.S.; Segovia, D.; Jin, Z.; Yoon, H.H.; Junior, P.L.S.; et al. Efficacy of perioperative and neoadjuvant therapies in gastric and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: A network meta-analysis. Oncologist 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, E.C.; Knödler, M.; Giraut, A.; Mauer, M.; Nilsson, M.; Van Grieken, N.; Wagner, A.D.; Moehler, M.; Lordick, F. VESTIGE: Adjuvant Immunotherapy in Patients With Resected Esophageal, Gastroesophageal Junction and Gastric Cancer Following Preoperative Chemotherapy With High Risk for Recurrence (N+ and/or R1): An Open Label Randomized Controlled Phase-2-Study. Front. Oncol. 2020, 9, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.R.; Kamarajah, S.K.; Madhavan, A.; Wahed, S.; Navidi, M.; Immanuel, A.; Hayes, N.; Phillips, A.W. The impact of age on long-term survival following gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2023, 105, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaji, Y.; Saeki, H.; Kudou, K.; Nakanishi, R.; Sugiyama, M.; Nakashima, Y.; Ando, K.; Oda, Y.; Oki, E.; Maehara, Y. Short- and Long-term Outcomes of Surgical Treatment for Remnant Gastric Cancer After Distal Gastrectomy. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 1411–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2021 (6th edition). Gastric Cancer 2023, 26, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.