Abstract

Background: inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformations and fistulas (IMAVMs/IMAVFs) are rare but clinically significant vascular anomalies characterized by abnormal communications between arterial and venous systems, leading to major hemodynamic disturbances. These lesions may be silent or cause disabling and difficult-to-diagnose symptoms such as colonic ischemia, portal hypertension, or even high-output cardiomyopathy. Methods: this narrative review aims to summarize current evidence on the pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnostic methods, and therapeutic management of these rare pathologies, supported by two our clinical cases. Conclusions: due to their rarity, multidisciplinary management and anatomical guided therapy are required for safe and lasting outcomes in patients with IMAVMs and IMAVFs.

1. Introduction

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) and arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) are defined as abnormal communications between arterial and venous vessels, either directly connected (AVFs) or through a network of abnormal vessels referred to as a “nidus” (AVMs).

These lesions result from mistakes made during the several phases of embryogenesis [1].

The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) categorizes AVMs as high-flow vascular malformations regardless of the existence of a nidus or micro/macro fistulas. Their increased risk of consequences, more varied clinical behavior, and greater anatomical and hemodynamic complexity set them apart from low-flow malformations (venous, lymphatic, or capillary) [2].

Due to diagnostic difficulties and the frequent misinterpretation of hemangiomas as AVMs, it is challenging to estimate the incidence of arteriovenous malformations.

Few studies analyze a large population sample. Among these, Tasnádi included 3573 three-year-old children, while BB Lee et al. analyzed a cohort of 1475 patients with peripheral vascular malformations with a 12% incidence [3,4]. More detailed epidemiological data are available for cerebrospinal AVMs, with an estimated incidence of 18 per 100,000 individuals [5].

Vascular malformations involving the splanchnic circulation represent a heterogeneous and infrequent subgroup, in which detailed knowledge of the regional arterial and venous anatomy is essential. The IMA arises from the abdominal aorta and supplies blood to the left portion of the colon (from the point of Cannon–Bohm at the distal third of the transverse colon to the sigmoid colon) and the upper two-thirds of the rectum, while the IMV drains the corresponding venous territories into the portal circulation. Several clinically and surgically relevant anatomical variants of the IMA have been described, including differences in caliber and development (from hypoplasia to rare absence), variations in the level of origin relative to the typical L3 level, and exceptional origins from a common trunk with other visceral arteries [6] (Figure 1).

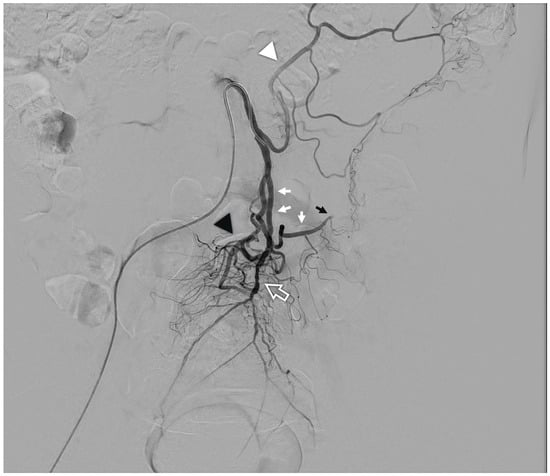

Figure 1.

Arteriography of a normal inferior mesenteric artery: from the vessel arise the left colic artery (white arrowhead), the main sigmoid artery (white arrows) which continues into the marginal artery of Drummond (black arrow); the terminal branch is the superior rectal artery (white contour arrow) from which typically arise an accessory sigmoid branch (black arrowhead).

Within this anatomical framework, AVMs and AVFs affecting the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) are extremely uncommon but clinically relevant entities. They often present with variable and non-specific symptoms, making early diagnosis particularly challenging.

Only few cases of primary or secondary Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula (IMAVF) have been reported in the literature, and pure Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformation (IMAVM) are even rare [7,8]. Overall, fewer than 100 cases have been described in the literature, usually as case reports or case series [9].

2. Methods

This study was designed as a narrative review of the literature aimed at synthesizing the current body of evidence regarding this pathology. Given the rarity of this condition and the predominance of isolated case reports and small case series, a narrative approach was chosen to allow a comprehensive and contextual analysis of heterogeneous data. The review focuses on key aspects of the disease, including pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical presentation, diagnostic techniques, treatment options and reported outcomes.

In addition to the literature review, we report two clinical cases of IMAVM observed and treated at our institution.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed to identify studies reporting IMAVM or IMAVF in the setting of vascular surgery, abdominal surgery, interventional radiology, and gastroenterology. The search included articles published between 2000 and 2025 and utilized the following MeSH terms: [inferior mesenteric artery], [arteriovenous malformation], [arteriovenous fistula], and [embolization]. Only articles published in English were considered. Additional relevant articles published prior to this period were included if identified through the reference lists of selected papers, based on their relevance to the topic.

Studies were selected based on their title and abstract, then Full texts were reviewed for inclusion based on relevance to visceral arteriovenous malformations of the splanchnic area.

3. Pathophysiology and Clinical Presentation

In cases of AVMs or AVFs, the direct communication between the arterial and venous systems can seriously impair normal hemodynamics. This can result in increased pressure within the portal venous system as well as ischemic impairment of colonic perfusion.

In case of anomalous direct communication between the arterial and venous systems, the balancing mechanism of the capillary system fails. Blood is diverted into the low-resistance shunt lowering arterial pressure downstream of the AVM [10]. If the hemodynamic impact is mild, this pressure drop may be minimal; however, in cases of significant shunting, the resulting hypoperfusion can lead to peripheral ischemia, diverting flow from the colonic microcirculation (the so-called “steal phenomenon”) and causing local venous congestion [11].

On the venous system, the increased arterial inflow leads to portal hypertension, potentially resulting in cardiac volume overload. The body responds to these hemodynamic changes with adaptive mechanisms. In the initial compensatory phase, cardiac output increases to maintain adequate arterial perfusion despite decreased peripheral resistance. Over time, however, this compensation may fail, leading to cardiac dilation and high-output cardiomyopathy [12,13].

The clinical presentation of IMAVM/IMAVF is therefore heterogeneous and often insidious. Common manifestations include:

- Chronic or recurrent abdominal pain, typically localized to the left lower quadrant [14];

- Diarrhea with mucus, and either occult or overt gastrointestinal bleeding (hematochezia) [15];

- Colonic ischemic symptoms—non-occlusive ischemic colitis—with findings such as mural edema, mucosal congestion, and reduced perfusion [14];

- Presence of an intestinal mass, a rare but documented manifestation that frequently leads to misdiagnosis [16];

- Signs of portal hypertension (in cases of significant arteriovenous shunting), such as varices, ascites, or splenomegaly [13];

- Systemic signs of cardiac overload in high-flow cases [13].

Even more rarely, AVMs may involve both the IMA and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), resulting in a “dual arterial supply” to the same colonic malformation. This dual supply significantly increases diagnostic, hemodynamic, and therapeutic complexity [17] A representative case is described by Richards et al. in the American Journal of Interventional Radiology, where a colonic AVM received dual arterial supply from both the SMA and IMA, and was associated with hepatic venous congestion and portal hypertension [18].

4. Diagnosis and Classification

The diagnosis of IMAVM/IMAVF presents a significant challenge for both radiologists and clinicians, due to their rarity, morphological variability, and frequently non-specific clinical manifestations.

4.1. Doppler Ultrasound and Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA)

Color Doppler ultrasonography could be used as a first diagnostic procedure, possibly detecting aliasing and turbulent, high-velocity flow in the draining veins or inferior mesenteric arteries. However, inter-individual anatomical variability and the depth of the anatomical structures limit its sensitivity.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CTA) is the preferred modality for anatomical characterization and lesion assessment. The most frequently observed findings include:

- Dilatation of involved arteries and veins, which may appear serpiginous and tortuous;

- Simultaneous arterial and venous opacification (early venous filling), a hallmark of arteriovenous shunting;

- Presence of a disorganized vascular nidus (in AVMs) or a single direct connection (in AVFs);

- Secondary signs such as mesenteric congestion, bowel wall thickening, mesocolic edema, or ischemic changes in the colon (e.g., hypoperfusion, edema, wall thickening) within the affected vascular territory.

Multiplanar and three-dimensional reconstructions (MIP and VR) are essential for mapping the afferent and draining vessels, especially when dual arterial supply from both the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries is suspected [19,20,21].

4.2. Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA)

MRA offers supplementary, non-invasive data on nidus morphology and flow dynamics. By differentiating between early arterial and late venous phases, time-resolved sequences (such as 4D-MRA) enable the viewing of the temporal progression of arteriovenous filling.

AVMs appear as hyperintense vascular masses on T2-weighted sequences, with rapid filling and early washout following contrast administration, whereas AVFs demonstrate a single focal connection with immediate venous opacification [22].

4.3. Diagnostic Angiography: The Gold Standard

The gold standard for conclusive diagnosis and endovascular treatment planning is still digital subtraction angiography (DSA). Selective catheterization of the IMA (and, if necessary, the SMA) is carried out during DSA in order to evaluate:

- The number and caliber of feeding vessels;

- Presence and configuration of the nidus (in AVMs);

- The site of early venous drainage;

- The connection to the portal or systemic venous systems.

The early venous filling (EVF) sign is one of the main diagnostic criteria on angiographic studies. During the arterial phase, it appears as opacification of the colic or inferior mesenteric veins, often with rapid progression into the portal vein or iliac venous system. EVF is considered a marker of an active high-flow shunt, indicative of a hemodynamically significant and potentially progressive malformation [23,24,25].

According to Moon et al., a multimodal imaging technique is frequently required to obtain an appropriate diagnosis due to the diagnostic complexity of these pathologies [26]. In cases of disabling symptoms, colonoscopy may also be employed to assess mucosal damage and to guide decisions regarding surgical resection of ischemic colonic segments [25].

4.4. Classification

There is currently no specific classification system dedicated exclusively to inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformations or fistulas (IMAVMs/IMAVFs). However, in clinical practice, these lesions can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Primary (congenital or idiopathic) IMAVMs/IMAVFs: these arise from mistakes in the regression of embryonic vessels and are present from birth. Congenital forms may occur also as part of syndromic conditions such as Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome (hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia), an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mucocutaneous telangiectasias and multisystem arteriovenous malformations, often involving visceral organs [27].

Kim et al. for example, described an idiopathic, non-congenital IMAVF causing colonic ischemia in a patient with no prior history of abdominal surgery or trauma [28].

- Secondary/iatrogenic IMAVFs: these occur after vascular interventions, trauma, or surgical procedures (such as colonic resections or anastomoses) [29]. Okada et al. present a case of portal hypertension caused by a surgical fistula between inferior mesenteric vessels [30].

The therapeutic approach and prognosis of AVMs/AVFs are closely related to angiographic architecture, flow volume, the number of feeding or draining vessels, lesion location, and involvement of surrounding organs [31].

To standardize the characterization of vascular malformations and guide treatment strategies, several angiographic classification systems have been proposed. The Yakes classification is one of the most widely accepted and utilized, originally developed for extracranial vascular malformations but increasingly applied to peripheral and visceral lesions [32,33].

A recent article by Su et al. provides insights into the application of the Yakes classification to visceral AVMs. According to the authors, Type IIb lesions, characterized by a well-defined nidus draining into a single aneurysmal vein, are among the most susceptible to transarterial embolization, offering favorable technical access and outcomes.

In this review of IMAVMs/IMAVFs, the distribution of cases by Yakes type was as follows: Type IIa/IIb: 27 out of 43 cases (62.8%); Type IIIa: 6/43 cases (13.9%); Type I: 6/43 cases (13.9%); Type IIIb: 2/43 cases (4.6%); Type IV: 2/43 cases (4.6%).

These findings highlight the predominance of Type II lesions in this anatomical region, reinforcing the significance of detailed angiographic classification in selecting optimal therapeutic strategies [34] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Yakes classification of the AVM and the incidence of IMAVM for each type.

5. Treatment

The management of IMAVMs/IMAVFs must be tailored to the clinical presentation, the extent of the lesion, and the type of arteriovenous shunt. Three significant variables guide therapeutic choices: symptoms, vascular anatomy and the hemodynamic properties.

Symptomatic malformations, or those associated with a risk of colonic ischemia, mesenteric congestion, or massive bleeding, represent a certain indication for treatment. Conversely, incidental and asymptomatic AVMs/AVFs may be safely monitored, provided there is no evidence of hemodynamic progression or structural evolution [8,15,35].

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary for management, including close cooperation between colorectal surgeons, vascular surgeons, and interventional radiologists. The main therapeutic strategies are outlined below.

5.1. Endovascular Embolization

Thanks to developments in microcatheter techniques and the availability of new embolization materials, endovascular therapy has been increasingly important in the treatment of mesenteric AVMs and AVFs in the last few decades. It can be necessary to use several, frequently combined, entry vessels to the vascular anomalies. Superselective catheterization of feeding vessels using microcatheters and closure with embolic agents such coils, particles, n-butyl cyanoacrylate (glue), liquid embolics, or microcoils are made feasible by the selective arterial approach via the IMA [36,37] (Table 2).

Table 2.

List of different embolic agents commonly used in treatment of AVMs.

While several successful cases have been reported in the literature, the main risk associated with this technique remains secondary bowel ischemia [38].

The retrograde venous technique can be the better option when the nidus or arteriovenous shunt location is difficult to reach by the arterial flow due to vascular tortuosity or early contrast reflux. This technique involves advancing a microcatheter through the IMV or one of its colic branches, under fluoroscopic or CT guidance, up to the arteriovenous communication. Retrograde embolization offers several advantages: more complete filling of the nidus from distal to proximal; lower risk of colonic ischemia by preserving arterial inflow, controlled closure of the shunt; especially in high-flow lesions or those with multiple venous outflows.

The Yakes classification is particularly useful in guiding the choice of embolization type (Table 3) [34,35,39].

Table 3.

Therapeutic Implications related with Yakes classification of the AVM.

Endovascular embolization has shown high effectiveness, with reported symptom control rates between 80% and 95% [38].

Superselective embolization, particularly using non-adhesive embolic agents such as Onyx or PHIL, provides improved control of the nidus and minimizes the risk of reflux and colonic ischemia. However, in cases with high-flow shunting or complex angioarchitecture, a multistage or hybrid (arterial–venous) approach may be necessary to achieve optimal results [40].

Despite technical success, a non-negligible risk of recurrence exists, particularly in extensive nidus-type malformations or with multiple draining veins, where residual or recurrent flow may persist over time.

The most reported complications include:

- Segmental ischemic colitis, usually resulting from non-target or excessive embolization of colic branches.

- Recurrent bleeding, often due to incomplete occlusion or recanalization of the AVM/AVF.

These risks highlight the importance of meticulous pre-procedural planning, precise catheter positioning, and the use of embolic agents tailored to the specific lesion type [14,41].

5.2. Surgical Treatment

Before the development of endovascular embolization, surgical management was considered the treatment of choice. Nowadays it is reserved only for selected cases.

According to Chang CT et al. segmental resection of the affected colonic segment can be curative in localized malformations, particularly when the nidus is confined to a limited territory supplied by the IMA [7].

The technical impossibility of endovascular treatment because of poor vascular anatomy or the failure of catheter-based embolization is another indication for surgery as a first-line approach.

Nevertheless, surgery remains the gold standard for managing ischemic-perforative complications, whether procedure-related or intrinsic to the malformation itself.

The main surgical options include:

- Segmental colonic resection with primary anastomosis;

- Selective ligation of the arterial feeder or draining vein, particularly in isolated high-flow fistulas.

Hybrid approaches, where surgery is preceded or followed by selective embolization, aimed at reducing flow volume and minimizing intraoperative bleeding complications [25,42,43].

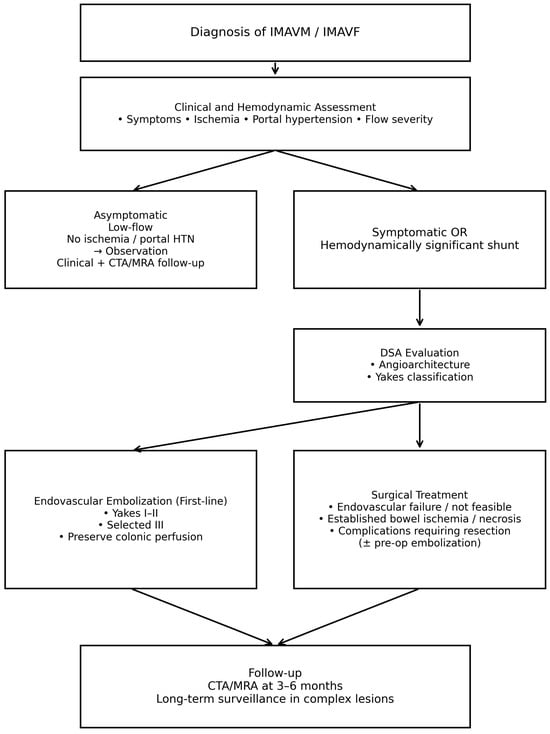

To clarify the therapeutic strategy and address the heterogeneity of treatment indications reported in the literature, a simplified, treatment-oriented decision algorithm is proposed (Figure 2). This flowchart summarizes the indications for observation, endovascular embolization, and surgical management based on clinical presentation, hemodynamic relevance, and angiographic features, and reflects the evidence and treatment principles discussed in the present review.

Figure 2.

Simplified treatment algorithm for inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformations and fistulas derived from the available evidence in the literature.

6. Prognosis and Follow-Up

In the long term, prognosis is primarily influenced by the durability of embolization and the potential for nidus recanalization.

Recanalization occurs in approximately 10–25% of cases, particularly in complex or multifocal AVMs [40,44].

A more favorable prognosis is associated with localized AVMs (Yakes types I–II), complete exclusion of the nidus from circulation and absence of pre-existing intestinal ischemia.

Conversely, diffuse or multifocal lesions—especially those with multiple venous outflows and involvement of the inferior colic venous plexus—carry a higher risk of recurrence or residual arteriovenous shunting [34,35,41].

For this reason, long-term clinical and imaging follow-up is essential.

Most authors recommend the following surveillance strategy:

- CT angiography (CTA) or contrast-enhanced MR angiography at 3–6 months post-treatment to assess for nidus occlusion and detect early recanalization.

- A second follow-up at 12 months, and then every two years in complex case [32,36,38,45].

Emerging intra-procedural cone-beam CT techniques also allow for real-time 3D mapping of the nidus during embolization, improving and facilitating comparison during subsequent follow-up studies [46,47].

7. Case Reports

In line with the evidence discussed in the preceding sections of this review, we present two clinical cases from our experience as representative examples. These cases reflect angiographic patterns commonly reported in inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformations and allow the key diagnostic and therapeutic aspects described in the literature to be contextualized. Although both lesions are classifiable as Yakes type II, they illustrate how clinically differences in presentation and imaging features may occur even within the same angiographic category. Furthermore, the cases provide practical confirmation of the treatment strategies outlined in this review, demonstrating how endovascular embolization, when guided by lesion-specific angioarchitecture, can achieve effective symptom control while preserving colonic perfusion.

7.1. Case 1

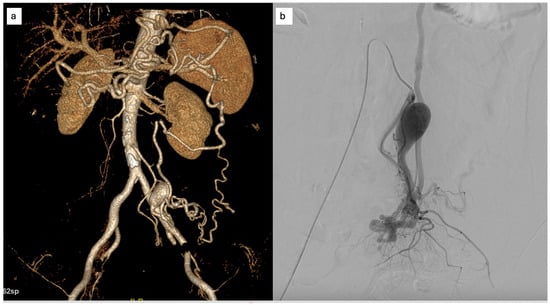

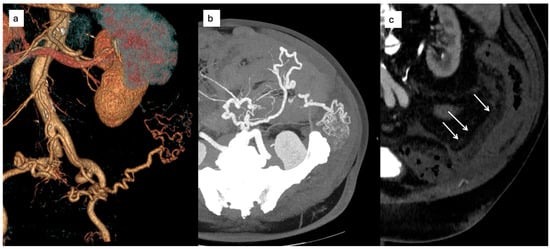

A 71-year-old woman with a medical history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and dyslipidemia presented with a two-month history of progressive, non-specific abdominal pain localized to the left lower quadrant. She was initially admitted to the emergency department of another hospital. She denied hematochezia, diarrhea, weight loss, or constitutional symptoms. The physical examination of the abdomen was unremarkable, and there were no clinical signs or symptoms of portal hypertension. Full laboratory tests yielded normal results. An initial contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan performed at another institution revealed abnormal dilatation of mesenteric vessels with early venous filling, suggestive of a high-flow vascular lesion. The patient was referred to our center for further evaluation. CT angiography confirmed the presence of an inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformation consistent with a Yakes type IIb lesion, characterized by a compact nidus and aneurysmal dilatation of the draining vein, unknown to the patient (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Finding at CT scan of an IMAVM with the aneurysmal dilation of the venous drainage; (b) DSA: superselective angiography of the AMI highlighting the angioarchitecture of the malformation.

Subsequently, digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was performed via the right femoral artery for definitive characterization and treatment planning.

Superselective catheterization of the feeding branches of the IMA was achieved using a microcatheter. Embolization was performed with a mixture of n-butyl cyanoacrylate (Glubran® 2) and Lipiodol®, resulting in complete exclusion of the nidus. A limited, clinically silent dissection of the IMA was observed at the end of the procedure, without impairment of distal perfusion.

Post-procedurally, the patient was managed conservatively. Antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg/day) was initiated due to the arterial dissection. No signs of bowel ischemia were observed, and the patient experienced progressive resolution of abdominal pain. Although elective surgical resection had initially been considered, it was deferred in light of clinical improvement.

At 12-month follow-up, CT angiography demonstrated persistent occlusion of the nidus with preserved colonic perfusion and a patent, remodeled IMA (Figure 4). The patient remained asymptomatic and free from abdominal pain.

Figure 4.

(a) selective microcatheterization of the AMI and embolization, (b) complete occlusion of the nidus with residual dissection of the AMI; (c) one year CT: persistent occlusion of the nidus with opacified dissecting AMI.

7.2. Case 2

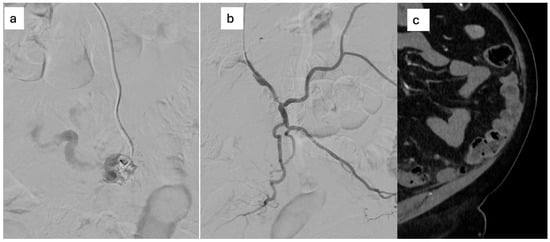

A 75-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension was admitted to the Gastroenterology Department for recent-onset changes in bowel habits associated with intermittent abdominal pain. There was no history of gastrointestinal bleeding, and laboratory tests, including hemoglobin and inflammatory markers, were within normal limits.

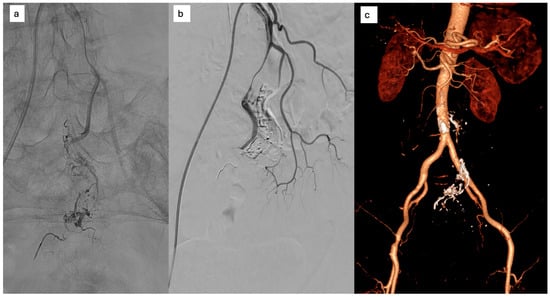

Contrast-enhanced CT imaging revealed tortuous mesenteric vessels arising from the IMA, associated with a small centromesenteric vascular nidus and early venous drainage into the sigmoid venous system. Perivisceral fat stranding and venous congestion of the sigmoid mesocolon were noted, raising suspicion for a hemodynamically significant AVM (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(a) CT volume rendering reconstruction showing a type II IMAVM, (b) transverse scan with evidence of the tortuous course of the afferent artery and the centromesenteric nidus; (c) CT showing signs of edematous perivisceral tissue (arrows).

The patient was referred for multidisciplinary evaluation. Subsequent DSA confirmed a Yakes type IIa inferior mesenteric AVM, supplied by three arterial feeders originating from the IMA, with early venous filling and no evidence of portal hypertension. Given the patient’s symptoms and imaging findings suggestive of venous congestion, endovascular treatment was recommended. The procedure was performed via radial arterial access. After selective catheterization of the IMA, a microcatheter was advanced into one of the dominant feeding arteries. Embolization was achieved using a Glubran®–Lipiodol® mixture. Despite the presence of multiple arterial feeders, complete nidus exclusion was obtained after embolization through a single afferent vessel, with immediate cessation of early venous drainage (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

(a) selective microcatheterization of the AMI and embolization with Glubran®–Lipiodol® mixture, (b) Complete nidus embolization after injection from a single feeding artery; (c) six-month CT: CT resolution of perivisceral congestion, without signs of recurrence.

The post-procedural course was uneventful. No antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy was prescribed, as no arterial injury or flow-limiting dissection was observed. The patient reported rapid improvement of abdominal symptoms.

8. Discussion

This review summarizes the available evidence on inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformations and fistulas, integrating anatomical, pathophysiological, diagnostic, and therapeutic aspects that are otherwise reported in a fragmented manner in the literature. IMAVMs/IMAVFs represent a particularly complex diagnostic challenge due to their extreme rarity and the wide spectrum of clinical presentations. Symptoms are often nonspecific and may range from mild abdominal discomfort to ischemic colitis, portal hypertension, or high-output heart failure, frequently resulting in delayed diagnosis and underrecognition of these lesions as a potential cause of unexplained colonic or portal hemodynamic disorders.

From a diagnostic perspective, the literature consistently supports a stepwise imaging approach. Computed tomography angiography plays a central role in the initial detection of IMAVMs/IMAVFs by identifying indirect signs of arteriovenous shunting. Digital subtraction angiography remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis, detailed assessment of flow characteristics and venous drainage patterns, angioarchitectural classification, and treatment planning. In this context, the Yakes classification, although originally developed for peripheral vascular malformations, provides a useful and reproducible framework for correlating angiographic morphology with therapeutic strategy in visceral lesions.

Therapeutic management represents a key insight emerging from the literature. In reported cases, endovascular embolization has progressively become the preferred first-line treatment for symptomatic IMAVMs/IMAVFs, largely replacing surgical approaches. The choice between transarterial, transvenous, or combined embolization techniques is guided primarily by angiographic features, including lesion type, shunt flow, and venous outflow configuration, rather than by clinical presentation alone. Achieving complete exclusion of the nidus is the main determinant of durable clinical success, whereas partial embolization is associated with persistent arteriovenous shunting and an increased risk of recurrence.

Surgical treatment currently plays a complementary role and should be reserved for selected scenarios, such as failed or technically unfeasible endovascular procedures, extensive bowel ischemia, or complications requiring intestinal resection. The lack of standardized management pathways and the heterogeneity of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies reported in the literature underscore the need for individualized, multidisciplinary decision-making involving vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists, and colorectal specialists.

Within this framework, our institutional experience is consistent with the patterns described in the literature and further supports the effectiveness of endovascular treatment in well-characterized, localized lesions. Overall, the findings of this review delineate the key diagnostic and therapeutic principles that may inform contemporary management of IMAVMs/IMAVFs, particularly in the absence of disease-specific recommendations.

In conclusion IMAVMs/IMAVFs are exceptionally rare pathologies with potentially severe clinical consequences. Despite their low incidence, they should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained colonic ischemia, recurrent lower gastrointestinal bleeding, or non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, especially when conventional diagnostic pathways fail to identify an underlying cause.

Due to the extraordinary rarity of IMAVMs/IMAVFs, the currently available evidence is largely derived from single case reports and small case series. This body of literature is intrinsically affected by publication bias, with a predominance of symptomatic, complex, or successfully treated cases, potentially leading to an overestimation of treatment efficacy and safety. Moreover, the absence of standardized diagnostic criteria, outcome definitions, and follow-up protocols limits comparability between studies.

An additional limitation is the marked heterogeneity in lesion classification and management. The terms AVM and AVF are sometimes used interchangeably, and although angiographic classification is increasingly based on the Yakes system, its application is not uniform. Treatment strategies vary widely in access routes, embolic agents, and procedural objectives, reflecting both evolving techniques and the lack of validated, disease-specific guidelines.

Future research should prioritize standardized reporting and the development of multicenter registries to improve data quality. Key objectives include defining the natural history of asymptomatic lesions, validating treatment algorithms based on angiographic architecture and flow characteristics, and assessing long-term clinical and radiological outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R., P.S., M.R. and F.S.; methodology and data curation, F.R. and E.R.; writing—review and editing, F.R.; supervision, P.S., M.R. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vikkula, M.; Boon, L.M.; Mulliken, J.B. Molecular genetics of vascular malformations. Matrix Biol. 2001, 20, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapadia, S.; Thakore, V.; Patel, H. Vascular malformations: An update on classification, clinical features, and management principles. Indian J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2017, 4, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnádi, G. Epidemiology and etiology of congenital vascular malformations. Semin. Vasc. Surg. 1993, 6, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.-B. Changing concept on vascular malformation: No longer enigma. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 2008, 1, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Shahi, R.; Warlow, C. A systematic review of the frequency and prognosis of arteriovenous malformations of the brain in adults. Brain 2001, 124, 1900–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllou, G.; Belimezakis, N.; Lyros, O.; Arkadopoulos, N.; Demetriou, F.; Tsakotos, G.; Piagkou, M. The anatomy of the inferior mesenteric artery: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2025, 47, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.T.; Lim, W.X.; Liu, T.T.; Lin, Y.M.; Chang, C.D. Inferior mesenteric artery arteriovenous malformation, a rare cause of ischemic colitis: A case report. Medicine 2023, 102, E33413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasiou, A.; Michalinos, A.; Alexandrou, A.; Georgopoulos, S.; Felekouras, E. Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula: Case report and world-literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 8298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Shaheen, A.; Zijlstra, M.; Al-Yaman, W.; Shah, N.; Wenzke, K. Mesenteric arteriovenous malformation with associated inferior mesenteric vein occlusion: A rare cause of ischemic colitis. Clin. Endosc. 2025, 58, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, J.E.; Messina, L.M.; Golding, R.M.; Kerr, J.C.; Hobson, R.W.; Swan, K.G. Fistula size and hemodynamic events within and about canine femoral arteriovenous fistulas. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1977, 74, 551–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillo, F.; Mattassi, R.; Diociaiuti, A.; Neri, I.; Baraldini, V.; Dalmonte, P.; Amato, B.; Ametrano, O.; Amico, G.; Bianchini, G.; et al. Guidelines for Vascular Anomalies by the Italian Society for the study of Vascular Anomalies (SISAV). Int. Angiol. 2022, 41, 1–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götze, C.J.; Secknus, M.A.; Strauß, H.J.; Lauer, B.; Ohlow, M.A. High-output congestive heart failure due to congenital iliac arteriovenous fistula. Herz 2006, 31, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Gupta, J.; Rana, M.A.; Delu, A.; Guliani, S.; Marek, J. Spontaneous inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula as a cause of severe portal hypertension and cardiomyopathy. J. Vasc. Surg. Cases Innov. Tech. 2019, 5, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cubisino, A.; Schembri, V.; Guiu, B. Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula with colonic ischemia: A case report and review of the literature. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justaniah, A.I.; Molgaard, C.; Flacke, S.; Barto, A.; Iqbal, S. Congenital inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformation presenting with ischemic colitis: Endovascular treatment. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 24, 1761–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Zhao, R.; Guo, D.; Cai, K.; Zou, K.; Yang, J.; Zhu, L. Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula with nonpulsatile abdominal mass. Medicine 2017, 96, e8717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Q.Q.; Zheng, K.; Yang, Y.G.; Liu, P.; Fan, X.Q.; Ye, Z.D. Arteriovenous malformation of upper and lower mesenteric arteries. J. Vasc. Surg. 2025, 81, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, L.; Rohr, A.; Alli, A.; Lemons, S. Endovascular treatment of unique colonic arteriovenous malformation with dual supply from superior and inferior mesenteric arteries. Am. J. Interv. Radiol. 2021, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattay, R.R.; Miner, L.; Copelan, A.Z.; Davtyan, K.; Schmitt, J.E.; Church, E.W.; Mamourian, A.C. Unruptured Arteriovenous Malformations in the Multidetector Computed Tomography Era: Frequency of Detection and Predictable Failures. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2022, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelonch, L.M.; Enríquez-Navascués, J.M.; Bonel, T.P.; Ansorena, Y.S. Massive Left-sided Congestive Colitis Due to Idiopathic Inferior Mesenteric Arteriovenous Malformation. J. Clin. Imaging Sci. 2017, 7, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.F.; Masthoff, M.; Czihal, M.; Cucuruz, B.; Häberle, B.; Brill, R.; Wohlgemuth, W.A.; Wildgruber, M. Imaging of peripheral vascular malformations—Current concepts and future perspectives. Mol. Cell Pediatr. 2021, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoki, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Hori, M.; Nanbu, A.; Kumagai, H.; Nishiyama, Y.; Nukui, H.; Araki, T. MR digital subtraction angiography for the assessment of cranial arteriovenous malformations and fistulas. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2000, 175, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswas, S.; Chandran, A.; Radon, M.; Puthuran, M.; Bhojak, M.; Nahser, H.C.; Das, K. Accuracy of four-dimensional CT angiography in detection and characterisation of arteriovenous malformations and dural arteriovenous fistulas. Neuroradiol. J. 2015, 28, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidmar, J.; Omejc, M.; Dežman, R.; Popovič, P. Thrombosis of pancreatic arteriovenous malformation induced by diagnostic angiography: Case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016, 16, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njoum, Y.; Alshawwa, K.; Jaber, B.; Abu-Zaydeh, O. Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformation extending to splenic flexure colonic wall presenting with massive lower gastrointestinal bleeding, a case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 107, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.-J.; Lee, S.-H. Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula: Two case reports. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2025, 17, 107139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, K.E.; Armstrong, S.Q.; Butt, F.; Wang, M.L.; Hardman, R.; Czum, J.M. Arteriovenous Malformations in the Setting of Osler-Weber-Rendu: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Curr. Probl. Diagn. Radiol. 2022, 51, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Sim, J.Y.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, J.H. Idiopathic Inferior Mesenteric Arteriovenous Fistula with Ischemic Colitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. J. Korean Soc. Radiol. 2016, 74, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, D.O.; Park, J.S.; Kim, J.E.; Lee, S.J.; Cho, H.J.; Im, S.G.; Kim, I.D.; Han, E.M. A case of traumatic inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula. Korean J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 62, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Furusyo, N.; Sawayama, Y.; Ishikawa, N.; Nabeshima, S.; Tsuchihashi, T.; Kashiwagi, S.; Hayashi, J. Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous fistula eight years after sigmoidectomy. Intern. Med. 2002, 41, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Su, L.; Wang, D.; Fan, X. Overview of peripheral arteriovenous malformations: From diagnosis to treatment methods. J. Interv. Med. 2023, 6, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakes, W.; Yakes, A.; Rohlffs, F.; Ivancev, K. Current Controversies and the State of the Art in Endovascular Treatment of Vascular Malformations. J. Interv. Med. 2019, 1, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoue, S.; Tanaka, N.; Koganemaru, M.; Kuhara, A.; Kugiyama, T.; Sawano, M.; Abe, T. Head and Neck Arteriovenous Malformations: Clinical Manifestations and Endovascular Treatments. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 8, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, B.Y.; Wang, Y.C.; Weng, M.J.; Chen, M.C.Y. Trans-arterial embolization of a Yakes type IIb inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformation: A case report and literature review for angio-architecture analysis. Radiol. Case Rep. 2023, 18, 1620–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakes, W.F. The Retrograde Vein Approach as a Curative Treatment Strategy for Yakes Type I, IIb AVMs, IIIa AVMs, and IIIb AVMs. J. Vasc. Surg. 2024, 79, 61S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, M.; González Costero, R.; Méndez Alonso, S.; Gómez-Patiño, J.; García-Suarez, A. Endovascular treatment of an inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformation causing ischemic colitis. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2018, 29, 1629–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, N.; Inoue, M.; Ishida, K.; Taguchi, H.; Haga, M.; Shimoda, E.; Morimoto, K.; Takahama, J.; Tanaka, T. A Case of Refractory Esophageal Varices Caused by an Inferior Mesenteric Arteriovenous Malformation with All Portal System Occlusion Successfully Treated via Transarterial Embolization. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 8, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruge, A.; Kumar, N.; Jose, L.K.; Mahalmani, V. Transarterial embolization of secondary inferior and superior mesenteric artery arteriovenous fistulas: A systematic review. Egypt. J. Radiol. Nucl. Med. 2022, 53, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, M.; Wada, T.; Kondo, H. Successful Treatment of Inferior Mesenteric Arteriovenous Malformation Using Direct Mesenteric Venous Puncture Embolization Combined with Transarterial Embolization. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 48, 410–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamo, M.; Yagihashi, K.; Okamoto, T.; Nakamura, K.; Fujita, Y.; Kurihara, Y. High-Flow Vascular Malformation in the Sigmoid Mesentery Successfully Treated with a Combination of Transarterial and Transvenous Embolization. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016, 39, 1774–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota, K.; Kariya, S.; Ueno, Y.; Nakatani, M.; Ono, Y.; Maruyama, T.; Komemushi, A.; Uda, M.; Nishimura, S.; Tanigawa, N. Venous Rupture Following Transcatheter Arterial Embolization for Inferior Mesenteric Type II Arteriovenous Malformation. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 7, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shraishi, T.; Kunizaki, M.; Takaki, H.; Horikami, K.; Yonemitsu, N.; Ikari, H. A case of arteriovenous malformation in the inferior mesenteric artery region resected surgically under intraoperative indocyanine green fluorescence imaging. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2022, 92, 106831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorospe, E.C.; Leggett, C.L.; Sun, G. Inferior mesenteric arteriovenous malformation: An unusual cause of ischemic colitis. Ann. Gastroenterol. 2012, 25, 165. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3959400/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Osuga, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Higashihara, H.; Juri, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Higashiyama, A.; Matsutani, H.; Sugimoto, A.; Toda, S.; Fujitani, T. Endovascular and Percutaneous Embolotherapy for the Body and Extremity Arteriovenous Malformations. Interv. Radiol. 2023, 8, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poullos, P.D.; Thompson, A.C.; Holz, G.S.; Edelman, L.A.; Jeffrey, R.B. Ischemic colitis due to a mesenteric arteriovenous malformation in a patient with a connective tissue disorder. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2014, 8, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Smadi, A.; Elmokadem, A.; Shaibani, A.; Hurley, M.; Potts, M.; Jahromi, B.; Ansari, S. Adjunctive Efficacy of Intra-Arterial Conebeam CT Angiography Relative to DSA in the Diagnosis and Surgical Planning of Micro-Arteriovenous Malformations. Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2018, 39, 1689–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, V.F.; Masthoff, M.; Brill, R.; Sporns, P.B.; Köhler, M.; Schulze-Zachau, V.; Takes, M.; Ehrl, D.; Puhr-Westerheide, D.; Kunz, W.G.; et al. Image-Guided Embolotherapy of Arteriovenous Malformations of the Face. Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2022, 45, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.