1. Introduction

Disruptions in diurnal rhythm have been increasingly linked to obesity and related cardiometabolic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [

1]. Misalignment of the body’s internal clock with the external environment can lead to metabolic disturbances, impaired glucose regulation, and increased inflammation, all of which contribute to the progression of these conditions [

2]. Recent studies have even demonstrated an association between circadian rhythm disruptions, obesity, and increased incidence and progression of several types of cancer, including breast, prostate, colorectal, and thyroid cancer [

3].

Various methods are used to monitor diurnal rhythms, including tracking sleep–wake cycles using polysomnography, measuring levels of hormones like cortisol and melatonin, and assessing metabolic markers such as blood glucose levels [

4,

5,

6,

7]. The drawbacks of these methods are that they are either invasive or place a significant burden on the patient or researcher. Recent studies suggest that vital parameters can also be used to describe a patient’s circadian rhythm [

8,

9]. Novel wearable sensors offer an appealing data source for assessing circadian rhythms, as they can continuously and unobtrusively collect vital parameters.

Obesity causes a reduction in the cardiovascular and respiratory functional reserve capacity of a patient, making them less able to compensate for increased physical stress [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Previous studies showed that patients with obesity have a higher resting heart rate than patients with a normal BMI. Additionally, heart rate returns to baseline levels more quickly after exertion in patients without obesity [

1]. The impact of obesity on the heart is evident through an increase in mean heart rate and arrhythmias, which is caused by cardiac changes such as increased ventricular mass, wall thickness, and internal dimensions of the left ventricle [

13]. Therefore, the impact of obesity and its consequences can potentially be evaluated by monitoring vital parameters such as heart rate.

Due to the increasing number of patients living with obesity, comorbidities or obesity complications such as coronary heart disease, dysrhythmia, hypertension, and diabetes are on the rise [

13]. This shows that it is not merely an issue of excess body weight; it is also recognized as a chronic disease with serious health implications. The complexity of obesity stems from its multifaceted causes, which include both genetic predisposition and environmental influences. These factors contribute to the development and persistence of obesity, making it a condition that is difficult to prevent and treat effectively.

The aim of bariatric surgery is to reduce the weight of patients living with a body mass index (BMI) over 35 kg/m

2, thereby reducing the risk of associated comorbidities [

14,

15]. The success of these procedures has been well documented, with patients achieving approximately 20–30% total weight loss (TWL) and a significant reduction in all-cause mortality. Studies have suggested there is a relationship between weight reduction through bariatric surgery and the recovery of sleep patterns and circadian rhythm lost due to obesity [

16].

In this study, we aimed to analyze changes in the circadian rhythms of patients after weight loss and compare them to the same cohort 2–3 years after bariatric surgery. The hypothesis was that obesity and its accompanying physiological changes cause a disrupted diurnal rhythm, and that weight loss resulting from bariatric surgery improves diurnal rhythm, which can be measured through changes in vital parameters, such as heart rate, by using a wearable monitoring device.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

The MOVIES study (trial number: NL84499.015.23—ethical and local committee approved were obtained) is a single-center observational study without invasive measurements. Patients who had undergone bariatric surgery at least 2 years ago with telemonitoring of vital parameters (2019–2020) using a wireless accelerometer were eligible to participate (TRICA-NL68560.015.18 or PEACH-NL74503.015.20) [

6,

17]. The patients were contacted by a member of the research team by telephone and asked whether they could be approached to participate in the study. If participants were interested, a consultation with information about the study was given. After this, an appointment with the researcher was scheduled to sign informed consent, followed by a reflection period to apply the monitoring device.

2.2. Study Population

The median pre-operative BMI of participants was 42 kg/m2 (39–46). Among the participants, 34 individuals (49.3%) underwent gastric sleeve surgery, while 35 individuals (50.7%) underwent gastric bypass. The patients showed an average total weight loss (TWL) of 31.4%, with individual results ranging from 24.2% to 36.8%. Two patients experienced minor complications (Clavien-Dindo grade 2), specifically wound infections. No other serious complications were reported.

2.3. Wearable Monitoring Device

In this study, participants used the Healthdot device (Philips Electronic Netherlands B.V., Eindhoven, The Netherlands), a wearable patch, which was affixed to the left lower rib along the midclavicular line. This accelerometer-based device is capable of monitoring heart rate and respiratory rate continuously for a period of up to two weeks. Utilizing built-in wireless long-range communication technology, it transmits 5 min averages of these vital parameters to a cloud server.

2.4. Selection Criteria

To be eligible for participation, patients needed to have a minimum of 48 h of analyzable data from prior studies. Patients were excluded if one of the following criteria was met: they had dropped out of a previous study because of problems with wearing the wireless monitoring device; they had experienced a cardiovascular event in the period from the previous study to the present; and/or they had undergone revisional surgery after the previous study period.

The participants were approached and asked to wear the Healthdot for 7 days, after which they could remove the device themselves. Data was transferred wirelessly to a secure cloud server, which was only accessible by the researchers.

Upon inclusion in the study, the patients’ data was collected from electronic medical records. This data included patient demographics such as gender; body mass index (BMI); obesity-related complications such as hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus (DM), and Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA); percentage of total weight loss (%TWL); and surgery type.

2.5. Study Parameters

The main study parameters and endpoints were the peak, nadir, and peak–nadir excursions of circadian HR before and after weight loss. Secondary study parameters and endpoints were the correlations between changes and TWL. No randomization was applied due to the observational nature of this study. All researchers were blinded with respect to patient data upon inclusion of patients.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

No formal sample size or power calculation was performed because of the very limited number of available studies with which to base the calculations on. This gives the MOVIES study an explorative or observational study nature. The synthesized study population form the TRICA and PEACH studies had a total of n = 309 patients. After patients with less than 48 h of data available 2 days after surgery were excluded, n = 233 patients were left for possible inclusion in the MOVIES study.

For statistical analysis, R (V4.3.2) and RStudio (v2023.12.1) were used [

18]. The tables describing both categorical data a numerical data show absolute values and percentages for categorical data. And in case of numerical data, normal distribution was assessed using a Shapiro–Wilk test. Numerical variables are expressed as means and standard deviations (SDs); in the case of a non-normal distribution, the median and interquartile range (IQR) are reported. To visually inspect the pattern of the HR data, a graph of mean heartrate data plotted over 4 days was created. In the pre-weight-loss data, the first 48 h post-surgery was excluded from any calculations because the data seemed to be distorted during this period [

19]. A Shapiro–Wilk test indicated there was a non-normal distribution; therefore, the median of the circadian rhythm features was reported. Peak–nadir excursions were calculated for each patient, with a peak defined as the 95th percentile and a nadir as the 5th percentile. The analysis of peak, nadir, and peak–nadir excursions is an accepted and often-used analysis of circadian rhythm, as shown in recent studies [

6,

20]. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to evaluate the delta of, or amount of change between, the baseline (before) and post-weight-loss peak, nadir, and peak–nadir excursions. Furthermore, a scatterplot was made to evaluate the relationship between the TWL and the amount of change in the peak, nadir, and peak–nadir excursions. Within the scatterplot, a regression line was plotted with a Spearman correlation. Lastly, multivariable linear regression models were applied to the delta peak, nadir, and peak–nadir (per patient). Changes in disease status for OSA, hypertension, and DM (as these are the most relevant), along with sex and age (as numerical variables), were included in the model. Additionally, TWL was categorized as above or below 20% weight loss to assess its predictive value for the magnitude of the delta in circadian rhythm. This approach differs from the scatterplot analysis, which examines the relationship without inferring causation. For all statistical tests,

p < 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

A total of 233 patients were eligible to participate and approached by the researchers. A total of 73 patients did not respond. Out of 160 patients who received information about the study, 69 agreed to participate. The most common reasons for declining participation were a lack of interest in participating in a medical study and having to travel to the hospital for an appointment.

The patient characteristics for this population (

n = 69) show it is predominantly female (70%). The median last BMI (kg/m

2) was 28.4 [25.3–30.9], with a median TWL of 31.4% [24.2–36.8]. The average preoperative weight was 124.3. The distribution between gastric sleeve and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass was around 50% (

Table 1).

3.2. Circadian Heart Rate Analysis

Figure 1 shows a clear circadian type of rhythm, with lower heartrate data at night and higher data during the daytime. This was observed for both the before and after groups.

Table 2 shows the change in circadian rhythm analyzed using a peak–nadir analysis with a Wilcoxon signed-rank test for significance. It shows a statistically significant change or reduction in the median peak, nadir, and peak/nadir difference data, with a delta peak of 6.4, a delta nadir of 2.6, and lastly a delta peak/nadir difference of 5.5, with all

p-values below 0.001.

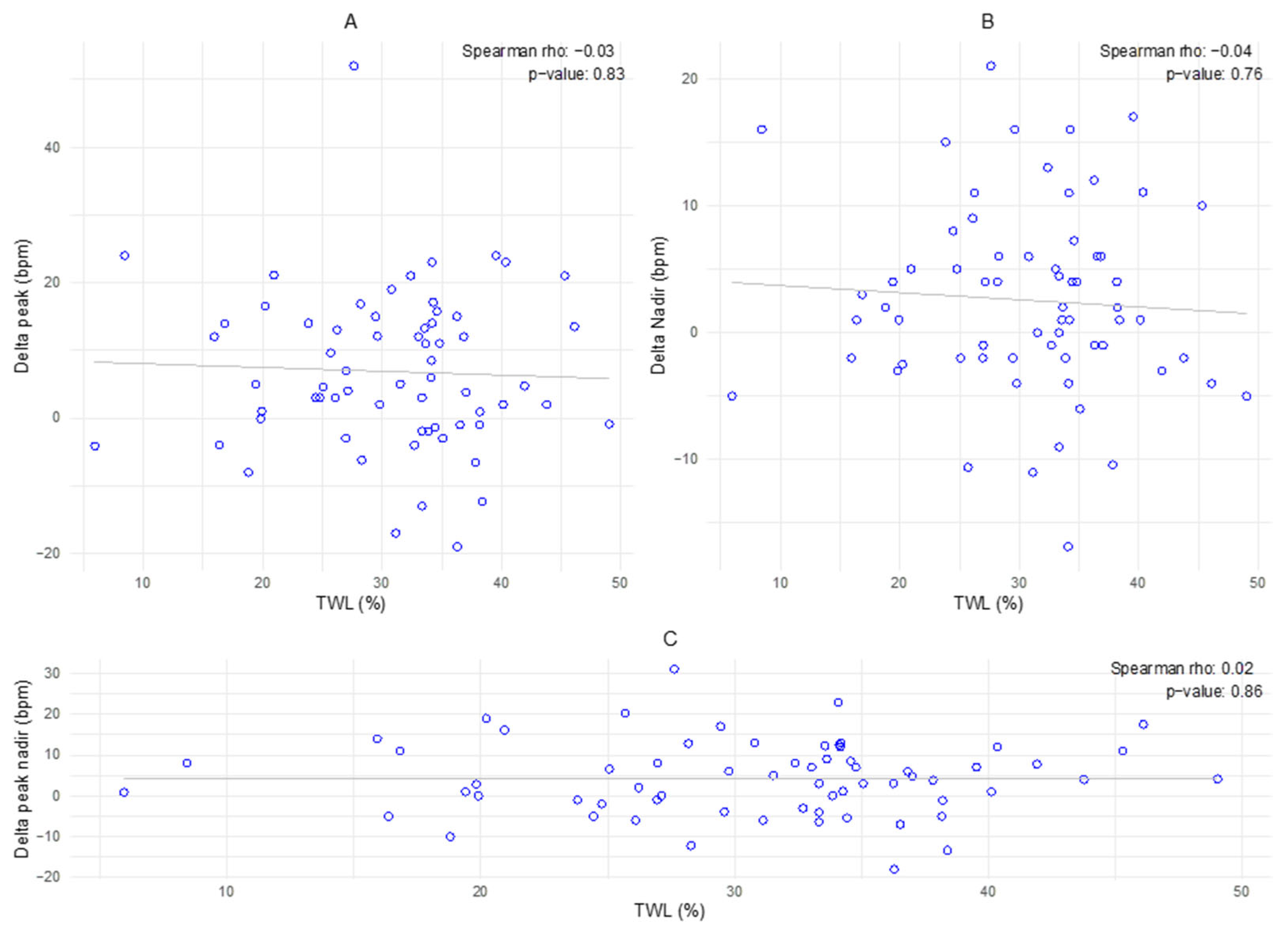

3.3. Delta Peak–Nadir in Relation to % of Total Weight Loss

The plots reveal a wide dispersion of data points, with no significant correlation observed for any of the variables (p = 0.83 for plot A, p = 0.76 for plot B, and p = 0.86 for plot C). The regression lines show no significant relation between the amount of change and TWL.

3.4. Delta–Peak Nadir in Relation to Patient Variables

The multivariable linear regression models showed no significant variables for the change in peak–nadir excursions, showing no relation between change in disease status for diabetes, hypertension, OSAS, or TWL (%) and the amount of change in peak, nadir, and peak–nadir excursions. Furthermore, sex and age do not seem to have any influence on the aforementioned endpoints (

Figure 2,

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study investigates changes in circadian heart rate patterns, measured via wearable technology, in patients following weight loss. The data show a significant difference towards lower peak–nadir excursions for all patients between pre- and post-weight-loss measurements. A peak–nadir analysis is a well-documented method for assessing circadian rhythm. This suggests that weight loss may be associated with improved health and normalized physiology, as reflected by altered circadian rhythms.

In addition, the average peak–nadir excursion after weight loss in this study was 23.15 (6.49), which seems to align more closely with the peak–nadir excursions observed for healthy individuals, as described by Hermida et al., than with the excursion obtained in the pre-weight-loss group, 26.96 (7.65) [

21].

After analyzing the correlation between changes in variables (age, DM, and OSA) and changes in circadian heart rate patterns, no significant correlation was found. This indicates that the variables do not explain, or only minimally explain, the variation in the delta peak, nadir, and peak–nadir values, and other factors may be of relevance.

The strengths of the present study include its observational design, in which both researchers and the care team were blinded to the research data. Moreover, the design reflects a real-world patient population, encompassing natural variation in the course of weight loss.

It is important to note that other studies describe the influence of anatomical and psychological sex differences on circadian rhythm [

22,

23]. A limitation of the present study is the predominance of female participants, which, given the aforementioned influence, may have confounded the results.

This study has several other limitations, including the risk of selection bias due to the study design. Due to the necessity of using baseline data, the eligible population for participation was restricted. Additionally, the small sample size could have led to type-II errors in the correlation analysis. There was also a significant amount of missing data in the follow-up cohort, as it consisted of the same patients from the baseline group, and this missing data could distort the results and peak–nadir analysis. A final limitation of this study is the absence of a control group of individuals without obesity. Including a healthy control group would help determine whether the observed changes bring patients closer to normal physiological patterns.

Future studies should focus on a larger sample size and a stricter baseline measurement with clear patient instructions, as exercise and movement in general have a large impact on heartrate measurements obtained using Healthdot. In addition, a baseline consisting of “healthy individuals” could possibly make for a better comparison between healthy and diseased individuals.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this analysis comparing continuously monitored heart rate data over seven days before and after weight loss due to metabolic surgery revealed a circadian rhythm. The study also demonstrated a significant change between baseline and post-weight-loss heart rate patterns. However, a clear clinical explanation of these observations could not be substantiated, as the changes in heartrate showed no correlation with total weight loss or other clinical variables.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.S., R.A.B. and S.W.N.; Methodology: J.S., M.H.F. and S.W.N.; Formal Analysis: J.S. and M.H.F.; Investigation: J.S., M.H.F. and F.S.; Data Curation: J.S., M.H.F. and F.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: J.S. and M.H.F.; Writing—Review and Editing: F.S., R.A.B. and S.W.N.; Supervision: R.A.B. and S.W.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The MOVIES trial (NL84499.015.23) was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the Maxima Medical Center, the Netherlands (Reference number W23.075), approved on 25 August 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study will be openly available once the manuscript has been accepted.

Conflicts of Interest

Since 2016, R.A.B. has served as a consultant for Philips (Research) Netherlands. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Itagi, A.B.H.; Jayalakshmi, M.K.; Yunus, G.Y. Effect of obesity on cardiovascular responses to submaximal treadmill exercise in adult males. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 4673–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reutrakul, S.; Van Cauter, E. Interactions between sleep, circadian function, and glucose metabolism: Implications for risk and severity of diabetes. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1311, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miro, C.; Docimo, A.; Barrea, L.; Verde, L.; Cernea, S.; Sojat, A.S.; Marina, L.V.; Docimo, G.; Colao, A.; Dentice, M.; et al. “Time” for obesity-related cancer: The role of the circadian rhythm in cancer pathogenesis and treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2023, 91, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claustrat, B.; Leston, J. Melatonin: Physiological effects in humans. Neurochirurgie 2015, 61, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüdtke, S.; Hermann, W.; Kirste, T.; Beneš, H.; Teipel, S. An algorithm for actigraphy-based sleep/wake scoring: Comparison with polysomnography. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestrom, E.H.J.; van der Stam, J.A.; Nienhuijs, S.W.; de Hingh, I.H.J.T.; Boer, A.K.; van Riel, N.A.W.; Scharnhorst, V.; Bouwman, R.A. Postoperative circadian patterns in wearable sensor measured heart rate: A prospective observational study. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 2024, 38, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miyazaki, T.; Kuwano, H.; Kato, H.; Ando, H.; Kimura, H.; Inose, T.; Ohno, T.; Suzuki, M.; Nakajima, M.; Manda, R.; et al. Correlation between serum melatonin circadian rhythm and intensive care unit psychosis after thoracic esophagectomy. Surgery 2003, 133, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, T.; Lemmer, B. Disturbance of circadian rhythms in analgosedated intensive care unit patients with and without craniocerebral injury. Chronobiol. Int. 2007, 24, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razjouyan, J.; Lee, H.; Parthasarathy, S.; Mohler, J.; Sharafkhaneh, A.; Najafi, B. Improving Sleep Quality Assessment Using Wearable Sensors by Including Information From Postural/Sleep Position Changes and Body Acceleration: A Comparison of Chest-Worn Sensors, Wrist Actigraphy, and Polysomnography. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2017, 13, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salome, C.M.; King, G.G.; Berend, N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 108, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, R.; Adams-Huet, B.; Jialal, I. The effect of increasing body mass index on cardio-metabolic risk and biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in nascent metabolic syndrome. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2017, 31, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpert, M.A.; Lavie, C.J.; Agrawal, H.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, S.A. Cardiac Effects of Obesity: Pathophysiologic, Clinical, and Prognostic Consequences-A Review. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2016, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esparham, A.; Shoar, S.; Kheradmand, H.R.; Ahmadyar, S.; Dalili, A.; Rezapanah, A.; Zandbaf, T.; Khorgami, Z. The Impact of Bariatric Surgery on Cardiac Structure, and Systolic and Diastolic Function in Patients with Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 345–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity: CDC. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/healthy-weight-growth/food-activity/overweight-obesity-impacts-health.html (accessed on 18 August 2024).

- Wiggins, T.; Guidozzi, N.; Welbourn, R.; Ahmed, A.R.; Markar, S.R. Association of bariatric surgery with all-cause mortality and incidence of obesity-related disease at a population level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnadas Solé, C.; Zerón Rugerio, M.F.; Foncillas Corvinos, J.; Díez-Noguera, A.; Cambras, T.; Izquierdo-Pulido, M. Sleeve gastrectomy in patients with severe obesity restores circadian rhythms and their relationship with sleep pattern. Chronobiol. Int. 2021, 38, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheerhoorn, J.; van Ede, L.; Luyer, M.D.P.; Buise, M.P.; Bouwman, R.A.; Nienhuijs, S.W. Postbariatric EArly discharge Controlled by Healthdot (PEACH) trial: Study protocol for a preference-based randomized trial. Trials 2022, 23, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- RT RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R 2024. Available online: https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/ (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Gögenur, I.; Wildschiøtz, G.; Rosenberg, J. Circadian distribution of sleep phases after major abdominal surgery. BJA Br. J. Anaesth. 2007, 100, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousins, L.; Rigg, L.; Hollingsworth, D.; Meis, P.; Halberg, F.; Brink, G.; Yen, S.S. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of the circadian rhythm of cortisol in pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1983, 145, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, R.C.; Ayala, D.E.; Fernández, J.R.; Mojón, A.; Alonso, I.; Calvo, C. Modeling the circadian variability of ambulatorily monitored blood pressure by multiple-component analysis. Chronobiol. Int. 2002, 19, 461–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, J.C.; Bumgarner, J.R.; Nelson, R.J. Sex Differences in Circadian Rhythms. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2022, 14, a039107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Depner, C.M.; Stothard, E.R.; Wright, K.P., Jr. Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2014, 14, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |