Abstract

The tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) is a globally important crop, yet its cultivation is continually challenged by a range of viral pathogens that can compromise plant health and product quality. In this study, eighteen symptomatic leaves were collected from the Hubei Province Tea Germplasm Resources Nursery, China, representing multiple cultivars and diverse genetic backgrounds. The samples were pooled into three groups and subjected to ribodepleted transcriptome sequencing. Analyses revealed a complex virome, with Tea plant necrotic ring blotch virus (TPNRBV) dominating Pools A and B, whereas Badnavirus betacolocalasiae was the most prevalent in Pool C. Functional enrichment of viral genes indicated involvement in multiple biological processes, including replication, host interaction, and metabolism. Notably, two previously uncharacterized viruses were identified: Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1 (TeaOLV1) and Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1 (TeaRLV1). Phylogenetic reconstruction positioned TeaOLV1 within the Penoulivirus genus, while TeaRLV1 formed a distinct clade among plant-associated rhabdoviruses. Conserved motif analysis revealed typical viral domains, accompanied by lineage-specific variations in tea plants. Collectively, these findings enhance our understanding of the viral diversity in tea plants, provide refined taxonomic placement for newly identified viruses, and offer molecular insights into their evolutionary relationships and potential functional roles.

1. Introduction

The tea plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) is a major commercial crop that grows predominantly in warm, humid tropical and subtropical regions. As the country of origin, China remains the world’s leading tea producer, with cultivation distributed across nearly all provinces, including Fujian, Zhejiang, Guangdong, Taiwan, Yunnan, and Sichuan [1]. Beyond China, tea is widely grown in countries such as India, Korea, Kenya, Japan, and Vietnam [2,3,4,5]. Due to its perennial nature, tea is susceptible to a range of diseases, including anthracnose (Gloeosporium theae sinensis Miyake), gray blight (Pestalotiopsis theae (Sawada) Steyaert), blister blight (Exobasidium vexans Massee), leaf blight (Colletotrichum camelliae Massee), and white scab (Phyllosticta theaefolia Hara) [6,7,8,9]. In addition, insect pests such as Ectropis oblique hypulina Wehrli, Euproctis pseudoconspersa Strand, Empoasca pirisuga Matsumura, and Toxoptera aurantia Boyer can significantly reduce plant growth and yield [10,11,12,13]. Interestingly, prior to 2018, only very few confirmed reports of viral infections in tea plants existed. This absence was largely attributed to the presumed antiviral properties of catechins in tea leaves, which were thought to provide broad-spectrum protection against viruses and other pathogens [14].

Recent developments in next-generation sequencing have substantially improved our capacity to characterize viral communities in tea plants and to uncover previously unrecognized viral species. Hao et al. collected tea leaves with various discoloration symptoms from multiple tea gardens in Hangzhou, China, and through metagenomic sequencing, they profiled the composition and transcript abundance of plant viruses, identifying seven distinct viral types, among which Tea plant necrotic ring blotch virus (TPNRBV) and Tea plant line pattern virus (TPLPV) were the most frequently detected [15]. TPNRBV, which induces necrotic ring blotches and leaf discoloration, represents a major threat to tea cultivation in China, Iran, and Japan [16,17,18]. Esmaeilzadeh et al. (2023) [19] examined the virus’s emergence in northern Iran since 2020, analyzing approximately 70 symptomatic and asymptomatic samples via RT-qPCR and sequencing. TPNRBV was confirmed in 26 samples, revealing both genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships among isolates from China, Iran, and Japan. Their study further demonstrated mechanical transmission to other plant species and suggested the possibility of seed-borne spread, highlighting multiple potential dissemination routes [19]. In addition, Ren et al. (2022) [20] developed a sensitive RT-qPCR assay for TPNRBV detection and proposed that insect vectors, such as mites, aphids, leafhoppers, and whiteflies, may facilitate viral transmission. Notably, albino tea cultivars exhibited heightened susceptibility under natural conditions [20].

Beyond TPNRBV, Wang et al. (2020) [9] reported a novel badnavirus, Badnavirus camelliae, (CSBV1) in Anhui Province, China. CSBV1 possesses an 8195 bp genome with three open reading frames (ORFs) and shares 68.6% nucleotide identity with Badnavirus rutilanscamelliae (CLGV) from C. japonica. Phylogenetic analysis placed CSBV1, CLGV, and cacao swollen shoot virus within a distinct clade of the Badnavirus genus, representing the first badnavirus documented in C. sinensis [21]. Similarly, Wu et al. (2020) identified tea-oil camellia deltapartitivirus 1 (TOCDV1), a virus with a tripartite dsRNA genome comprising 1712 nt (dsRNA1), 1504 nt (dsRNA2), and 1353 nt (dsRNA3) [22]. Jo et al. (2020) additionally reported two novel viruses, Camellia cryptic virus 1 (CCV1) and Camellia cryptic virus 2 (CCV2), based on tea plant transcriptome data [23]. During a comprehensive survey of tea plantations in Iran, 20 leaf samples were collected, leading to the first report of Camellia oleifera amalgavirus 1 (CoAV1) in tea plants. This finding not only expands the known viral repertoire of Camellia species but also highlights the need for further studies on virus–host interactions and their potential impacts on tea cultivation [24]. Collectively, these studies significantly advance our understanding of viral diversity in tea plants and underscore the importance of continued virome exploration in this globally important crop.

Tea leaves, as the primary economic and functional organs of the plant, serve as the major sites of photosynthesis and directly influence both yield and quality. Leaf discoloration represents a critical factor affecting tea production, and its underlying causes have been the focus of numerous studies. Evidence suggests that alterations in chlorophyll (Chl) metabolism are the principal drivers of this phenomenon [25,26,27,28,29,30]. Discolored tea leaves typically exhibit reduced levels of chlorophyll, carotenoids, and catechins compared with healthy green leaves [31,32,33,34]. The manifestation of leaf discoloration is a multifactorial process influenced by nutritional deficiencies, pest or pathogen damage, genetic variation, and environmental stressors. Although viral infection is frequently considered a potential contributing factor, affected plants often show stunted growth and, under certain conditions, display overt disease symptoms. Despite extensive investigations, the molecular mechanisms regulating leaf color variation in tea plants remain poorly understood, underscoring the need for further research [35]. Viral infections generally present with chlorosis or leaf discoloration, often accompanied by dwarfing or abnormal development, which in severe cases can result in plant mortality [36]. However, systematic studies examining the diversity and prevalence of viruses across different tea cultivars are still lacking [37].

In this work, eighteen tea leaf samples showing characteristic discoloration from various cultivars were analyzed through transcriptome sequencing combined with comprehensive bioinformatic approaches to explore the associated viral community. Analysis revealed that Tea plant necrotic ring blotch virus (TPNRBV) was the dominant virus in Pools A and B, while Badnavirus betacolocalasiae was most prevalent in Pool C. Gene Ontology analysis indicated that viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs) participate in a wide range of biological and cellular functions. Additionally, two previously unreported viruses were identified and characterized: Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1 (TeaOLV1), assigned to the genus Penoulivirus, and Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1 (TeaRLV1), forming a distinct lineage within plant-infecting rhabdoviruses. These results expand current knowledge of tea plant viromes and provide critical molecular and taxonomic information that may aid in precise virus detection, disease management strategies, and the breeding of virus-resistant tea cultivars.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material Collection and Preparation

Eighteen tea leaves exhibiting typical discoloration were collected from six leaves per cultivar across eighteen cultivars at the Hubei Province Tea Germplasm Resources Nursery, China. Pooling prevents assignment of viruses to individual cultivars; future RT-PCR validation on single plants is required. Samples were pooled into three groups: Pool A (Echa 1, Echa 10, Yulu 1, Longjing 43, Zhongcha 108, Fudingdabai), Pool B (Zhuyeqi, Zhenong 117, Fuyun 6, Jiukengzhong, Pingyangtezao, Bayutezao), and Pool C (Fudingdahao, Bixiangzao, Baihaozao, Jinguanyin, Yingshuang, Mingshan 131).

2.2. RNA Preparation and RNA Library Construction

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and treated with DNA-free™ Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to remove genomic DNA. RNA quality was confirmed before constructing rRNA-depleted total RNA libraries at Wuhan Berry Genomics Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, Hubei, China). Library integrity was assessed via Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and high-throughput paired-end sequencing (150 bp) was performed on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform(Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

2.3. Virus Identification

Adapters and low-quality sequences were removed using Cutadapt (v1.15) and Sickle, with quality assessment via FastQC. Non-viral reads were filtered with BBMap (v35.59) against the tea transcriptome, and de novo assembly was performed using Trinity (v2.2.0). Assembled contigs were annotated through BLAST (v2.15.0) searches against NCBI nr, nt, tea genome, and virus genome databases (E-value < 1 × 10−5). Viruses were classified according to the ICTV Master Species List (2024), and transcript abundance was quantified using RSEM (v1.2.11).

2.4. Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment Analysis

The potential genes in the virus genome are predicted using Prodigal software (v2.6.3). Subsequently, these predicted gene sequences are compared against NCBI database to determine the functions and homology of these genes. The gene sequences are aligned with known GO annotated databases for comparison. Utilize Diamond software (https://www.crystalimpact.com/diamond/ (accessed on 30 October 2025), version 0.8.35) to align the amino acid sequences of the non-redundant gene set with the GO database (https://www.geneontology.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2025)) (BLASTP alignment parameters set with an expected value (E-value) of 1 × 10−5) to acquire the corresponding GO functions for the genes.

2.5. Sequence Homology and Multiple Sequence Alignment Analysis

Amino acid sequences of representative proteins from over twenty characterized ourmia-like viruses and fifteen rhabdoviruses or rhabdo-like viruses were retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database for comparative analysis. These reference sequences were aligned with the corresponding proteins of the two newly identified tea plant viruses to examine sequence similarity and conserved domain features. The related amino acid sequences were aligned using MAFFT software (version 2.0) with the E-INS-i setting. The resulting alignments were inspected and visualized in MEGA 11 to identify conserved motifs, domain organization, and sequence polymorphisms, including amino acid substitutions, insertions, and deletions within key conserved regions (Domains I–IV).

2.6. Phylogenetic Tree Construction and Analysis

Phylogenetic relationships of the two novel viruses were inferred from the aligned amino acid datasets. Maximum-likelihood trees were generated using PhyML 3.0, with the most suitable substitution models determined by ProtTest 3.0. Based on model selection, the JTT+G model was applied to the ourmia-like virus dataset, while the WAG+G model was selected for rhabdovirus and rhabdo-like virus sequences. The robustness of the inferred topologies was evaluated through 1000 bootstrap replicates. Phylogenetic trees were visualized and annotated using FigTree v1.4.4, allowing for the identification of clustering patterns and clarification of the taxonomic relationships between the newly discovered viruses and established members of the corresponding families. Bootstrap values equal to or greater than 70% were considered to indicate statistically reliable node support.

3. Results

3.1. Sample Collection and Transcriptome Sequencing

To investigate viral infections in Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze, eighteen tea leaves exhibiting characteristic discoloration were collected from multiple cultivars at the Hubei Province Tea Germplasm Resources Nursery, China. These samples encompassed a broad range of genetic backgrounds and were divided into three pools, each comprising six leaves. Pool A included Echa 1, Echa 10, Yulu 1, Longjing 43, Zhongcha 108, and Fuding White Tea; Pool B contained Zhuyeqi, Zhenong 117, Fuyun 6, Jiukengzhong, Pingyangtezao, and Bashutezao; Pool C consisted of Fudingdahao, Bizaoxiang, Baihaozao, Jinguanyin, Yingshuang, and Mingshan 131 (Figure 1). Total RNA was extracted from each pool and sequenced using a high-throughput platform. Sequencing generated 291, 201, 862 paired-end reads, totaling 44.19 Gb of raw data. After quality control and trimming, 43.64 Gb of clean reads were retained. The clean reads were assembled into transcripts and unigenes, and the mapping rates to the assembled sequences were 98.89%, 98.98%, and 98.92% for Pools A, B, and C, respectively (Table 1). These data provide a high-quality transcriptome suitable for identifying and characterizing viral sequences in tea leaves. The dataset supports further analysis of plant-virus interactions and contributes to developing strategies for managing viral diseases in tea cultivation.

Figure 1.

Representative discoloration symptoms among collected tea samples for metagenomic analysis. The eighteen tea plant leaves are as follows: Echa 1, Echa 10, Yulu 1, Longjing 43, Zhongcha 108, and Fudingdabai in Pool A; Zhuyeqi, Zhenong 117, Fuyun 6, Jiukengzhong, Pingyangtezao, and Bayutezao in Pool B; and Fudingdahao, Bixiangzao, Baihaozao, Jinguanyin, Yingshuang, and Mingshan 131 in Pool C. Red asterisk (*) indicates leaf discoloration symptoms, while similar symptoms can also be caused by nutrient deficiency or phytoplasma.

Table 1.

Summary of the sequence data from RNA- seq.

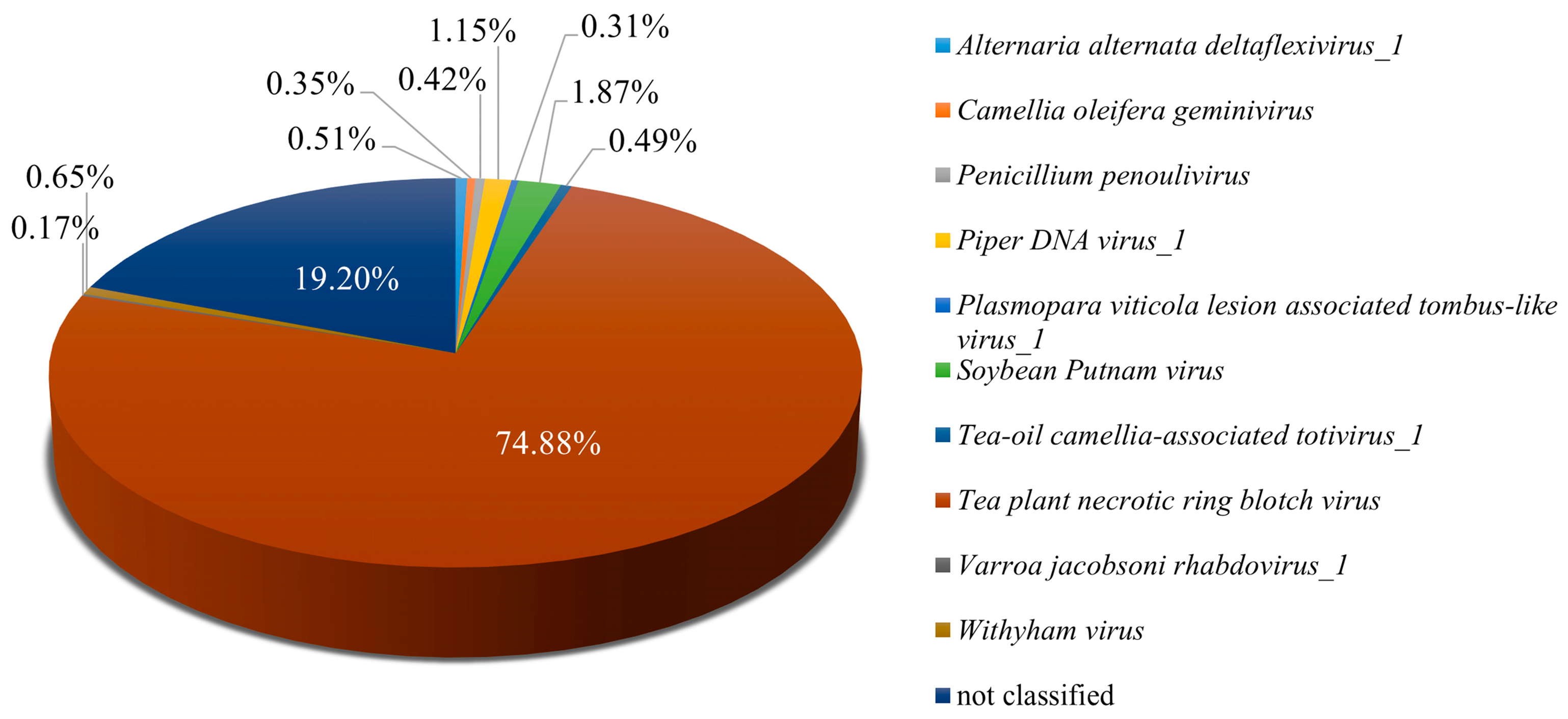

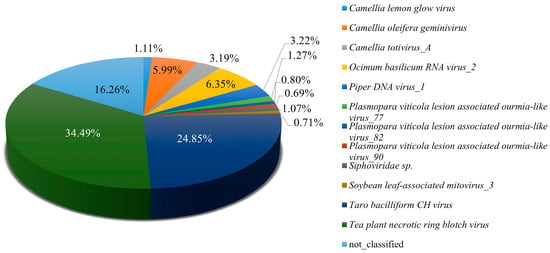

3.2. Virus Identification and GO Enrichment Analysis of Pool A

Analysis of Pool A revealed a diverse viral community infecting tea plants, indicating a complex virome. From the 95,887,710 paired-end clean reads obtained, 98.89% aligned to the assembled sequences, confirming the high quality of the dataset for downstream analyses. Tea plant necrotic ring blotch virus (TPNRBV) was the most prevalent, accounting for 74.88% of viral reads, which underscores its major contribution to infection in this pool. Additional viruses, including Soybean Putnam virus, Piper DNA virus_1, and Withyham virus, were present at lower abundances, collectively enhancing the viral diversity observed in Pool A (Figure 2). To gain preliminary insight into the potential functional roles of viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs), a Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was conducted. Given the limited functional annotation of viral genes, these results provide only an initial perspective and should be considered exploratory. Detailed results are presented, with the caveat that GO enrichment for viral genes may not reliably reflect their biological functions (Figure S1). Future work will involve targeted experimental validation, including RT-PCR and full-length genome characterization, to more accurately elucidate the functions of vOTUs and their interactions with tea plant hosts. Overall, these findings provide a comprehensive overview of the viral community in Pool A, highlighting both the predominance of specific viruses and the preliminary insights into their potential functional roles, thereby establishing a foundation for more detailed functional and mechanistic studies in the future.

Figure 2.

Identification of viral species in Pool A. Pool A comprises the following six tea plant cultivars: Echa 1, Echa 10, Yulu 1, Longjing 43, Zhongcha 108, and Fudingdabai.

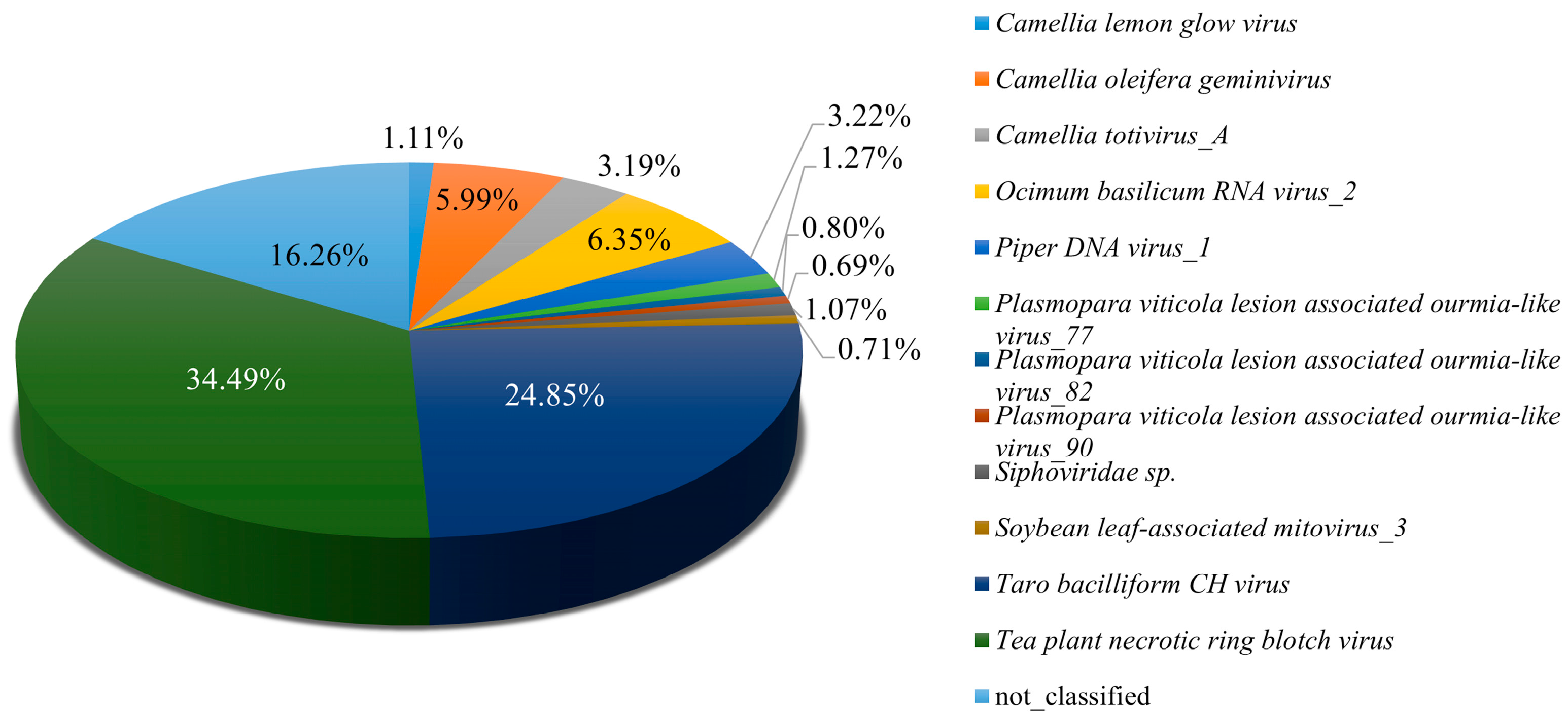

3.3. Virus Identification and GO Enrichment Analysis of Pool B

Analysis of Pool B revealed a diverse assemblage of viruses infecting tea plants, providing insights into the complexity of the associated virome. Among the 105,776,744 paired-end clean reads obtained, 98.98% successfully mapped to the assembled sequences, indicating high-quality data suitable for downstream analyses. Tea plant necrotic ring blotch virus (TPNRBV) was the most abundant virus, accounting for 34.49% of viral reads, highlighting its notable role in tea plant infection within this pool. Other viruses, including Badnavirus betacolocalasiae, Ocimum basilicum RNA virus_2, and Oil tea associated geminivirus, were also detected at lower abundances, contributing to the overall viral diversity in Pool B (Figure 3). To gain preliminary insight into the potential functional roles of viral vOTUs in Pool B, a GO enrichment analysis was performed. Given the limited annotation of viral genes, these results should be interpreted as exploratory. The detailed analysis is provided, with the caveat that GO enrichment for viral genes may not reliably reflect their true biological functions (Figure S2). These preliminary results suggest possible associations of vOTU genes with various molecular and cellular processes, including interactions with host membranes and organelles, as well as involvement in metabolic pathways and multi-organism interactions. Taken together, these findings present an initial perspective on the viral community in Pool B, illustrating both gene diversity and possible functional implications, and informing directions for subsequent experimental validation.

Figure 3.

Identification of viral species in Pool B. Pool B comprises the following six tea plant cultivars: Zhuyeqi, Zhenong 117, Fuyun 6, Jiukengzhong, Pingyangtezao and Bayutezao.

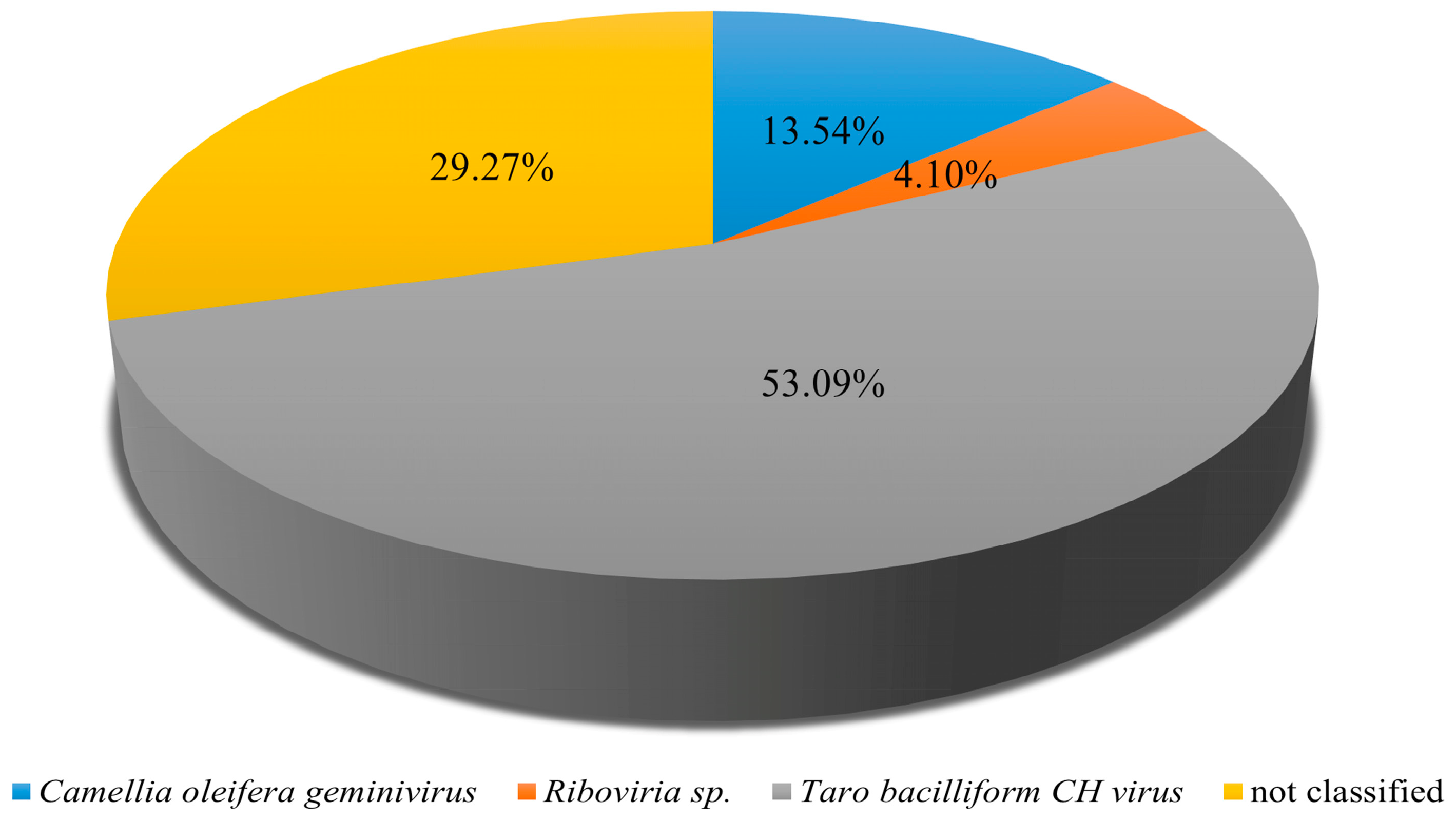

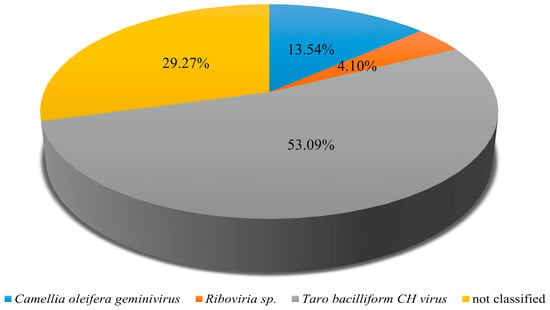

3.4. Virus Identification and GO Enrichment Analysis of Pool C

Analysis of Pool C revealed the presence of multiple viruses infecting tea plants, providing insights into the composition and dynamics of the virome in this pool. Among the 89,537,408 paired-end clean reads obtained, 98.92% successfully mapped to assembled sequences, indicating high-quality data suitable for downstream analyses. Badnavirus betacolocalasiae was the most abundant species, accounting for 53.09% of viral reads, followed by Oil tea associated geminivirus (13.54%) and Riboviria sp. (4.10%), with the remaining 29.27% of sequences unclassified (Figure 4). Among the identified viruses, some appeared highly abundant in certain samples. The reported dominance of Badnavirus betacolocalasiae presence requires independent confirmation because badnaviruses are usually monocot-specific and may represent contamination or integrated sequences. Future studies should employ targeted assays to confirm these observations.

Figure 4.

Identification of viral species in Pool C. Pool C comprises the following six tea plant cultivars: Fudingdahao, Bixiangzao, Baihaozao, Jinguanyin, Yingshuang and Mingshan 131.

To gain preliminary insight into the potential functional roles of viral vOTUs in Pool C, a GO enrichment analysis was performed. Due to the limited annotation of viral genes, these results are considered exploratory and should be interpreted with caution. The detailed analysis is provided, with the caveat that GO enrichment for viral genes may not accurately reflect their true biological functions (Figure S3). These preliminary findings suggest possible associations of vOTU genes with various cellular and molecular processes, including interactions with host cellular structures, metabolic pathways, and multi-organism interactions.

3.5. Identification and Phylogenetic Analysis of Tea Plant-Associated Ourmia-like Virus 1

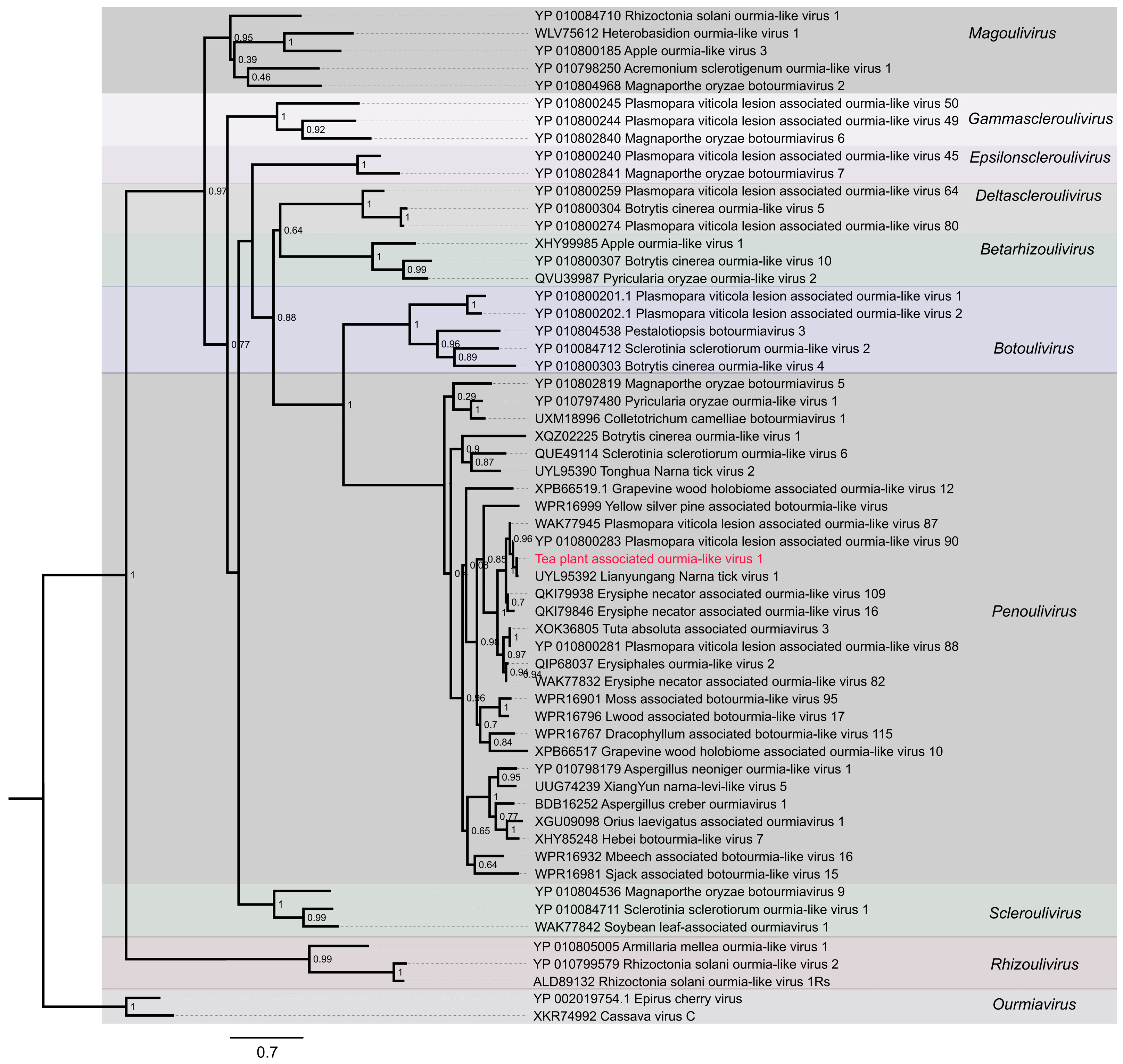

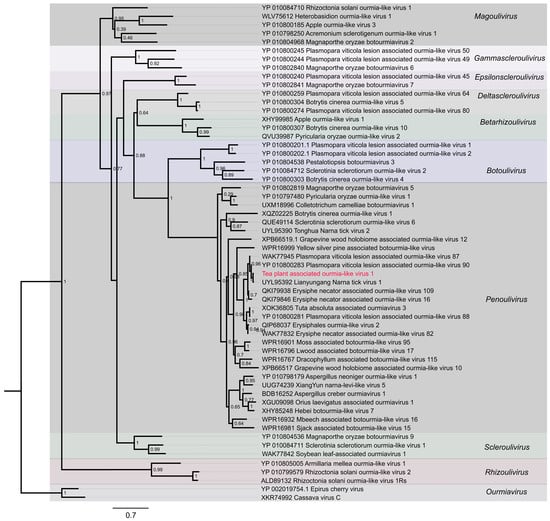

During the survey of tea plant viromes, a previously undescribed ourmia-like virus was detected in chlorotic leaves following comprehensive screening of viral sequence datasets. This virus was provisionally designated as Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1 (TeaOLV1). To clarify its evolutionary relationships, the amino acid sequences of its encoded proteins were compared with those of over twenty representative ourmia-like viruses and related taxa retrieved from the NCBI GenBank database (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree of Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1. The red labeled entries correspond to the novel viruses isolated in this study.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic analysis grouped the examined viruses into ten well-supported genera: Ourmiavirus, Rhizoulivirus, Scleroulivirus, Penoulivirus, Botoulivirus, Betarhizoulivirus, Deltascleroulivirus, Epsilonscleroulivirus, Gammascleroulivirus and Magoulivirus. TeaOLV1 consistently clustered within the Penoulivirus genus, alongside Botrytis cinerea ourmia-like virus 4 (YP_010800303), Magnaporthe oryzae botourmiavirus 9 (YP_010804536), Sclerotinia sclerotiorum ourmia-like virus 1 (YP_010084711), and S. sclerotiorum ourmia-like virus 2 (YP_010084712). This lineage was clearly distinct from the Ourmiavirus clade, represented by Epirus cherry virus (YP_002019754.1) and Cassava virus C (XKR74992), and from Rhizoulivirus, including Rhizoctonia solani ourmia-like virus 1Rs (ALD89132) and R. solani ourmia-like virus 2 (YP_010799579). No evidence of intergeneric recombination was observed. The TeaOLV1 cluster was supported by a bootstrap value of 70%, confirming its placement within Botoulivirus. These results expand the current understanding of ourmia-like viruses in tea plants and provide molecular insights that may facilitate future studies on their ecological roles, evolutionary history, and potential involvement in tea plant diseases.

3.6. Multiple Sequence Alignment Analysis of Amino Acids in Tea Plant-Associated Ourmia-like Virus 1

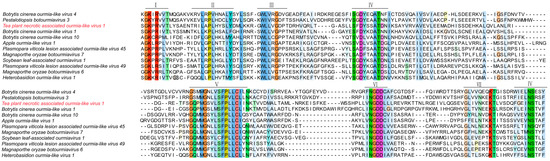

To assess sequence conservation and structural characteristics of Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1 (TeaOLV1), we performed multiple sequence alignment using its deduced amino acid sequences in comparison with fifteen previously characterized ourmia-like viruses. Conserved regions were identified based on curated viral protein domain datasets (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Multiple sequence alignment of amino acid sequences from Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1.

The alignment indicated that, although the analyzed viruses exhibited distinct overall amino acid compositions, several functional domains (Domains I–IV) contained partially conserved motifs. In particular, Domains II and IV displayed notable conservation, with the SGKPR motif in Domain II and the GWL/LVG motif in Domain IV being shared among multiple isolates. TeaOLV1 demonstrated high sequence similarity in these conserved regions with Botrytis cinerea ourmia-like virus 4 (YP_010800303) and Pestalotiopsis botourmiavirus 3 (YP_010804538), especially within the GWL/LVG motif and adjacent residues. Nevertheless, TeaOLV1 presented unique amino acid substitutions as well as insertion and deletion events at several conserved sites relative to Apple ourmia-like virus 1 (XHY99985), Plasmopara viticola lesion-associated ourmia-like viruses, and isolates of Magnaporthe oryzae botourmiavirus. Additional sequence divergence was noted in Domains V and VI, particularly when compared to Heterobasidion ourmia-like virus 1 (WLV75612) and Soybean leaf-associated ourmiavirus 1 (WAK77842), suggesting the occurrence of lineage-specific evolutionary changes in these regions. These results provide important molecular insights into the evolutionary differentiation of TeaOLV1 and offer a foundation for subsequent functional and comparative analyses of this virus and other ourmia-like viruses infecting tea plants.

3.7. Identification and Phylogenetic Relationship Analysis of Tea Plant-Associated Rhabdo-like Virus 1

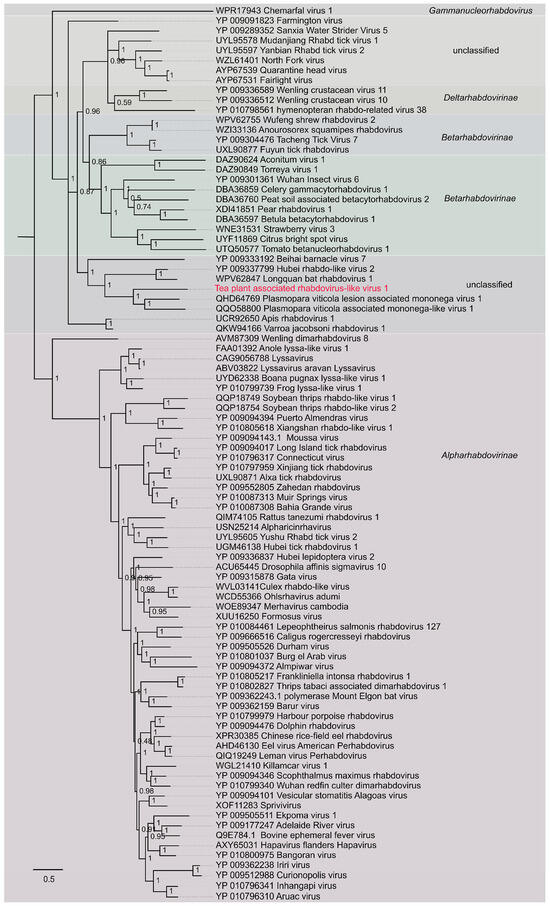

During the investigation of viral diversity in tea plants, a novel rhabdo-like virus was detected through targeted screening and sequence analysis of tea plant-derived viromes. The virus was provisionally named Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1 (TeaRLV1). To elucidate its evolutionary placement within the Rhabdoviridae family, a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using PhyML 3.0 under the WAG+G substitution model (Figure 7). Representative reference sequences from three recognized subfamilies of Rhabdoviridae-Alpharhabdovirinae, Betarhabdovirinae, and Deltarhabdovirinae-as well as several unclassified rhabdoviruses (e.g., Sanxia water strider virus 5) were included in the analysis.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1. The red labeled entries correspond to the novel viruses isolated in this study.

The resulting phylogeny resolved all examined taxa into distinct and well-supported clades consistent with their established taxonomy and host range. Notably, TeaRLV1 grouped exclusively with plant-associated rhabdoviruses, forming a discrete lineage together with Aconitum virus 1, Pear rhabdovirus 1, Betula betacytorhabdovirus 1, Strawberry virus 3, and Citrus bright spot virus. Bootstrap values for the major nodes within this plant-associated cluster ranged from 0.48 to 1.00, with several key nodes-such as the one uniting Aconitum virus 1 and Pear rhabdovirus 1-receiving full support (bootstrap = 1.00), thereby confirming the robustness of the inferred relationships. Importantly, the TeaRLV1-containing clade exhibited clear phylogenetic separation from clusters of animal-, insect-, and aquatic host-infecting rhabdoviruses, with no evidence of interclade mixing involving the Alpharhabdovirinae, Betarhabdovirinae, or Deltarhabdovirinae lineages. This plant-restricted lineage also showed a substantial genetic distance from aquatic taxa such as Wenling crustacean virus 10 and Scophrhavirus scophthalmi. Collectively, these results demonstrate that TeaRLV1 represents a distinct member of plant-associated rhabdo-like viruses with a well-defined evolutionary position. The identification of this virus expands the known virosphere of tea plants and provides valuable molecular evidence for understanding the evolutionary diversification of plant-infecting Rhabdoviridae.

3.8. Multiple Sequence Alignment Analysis of Amino Acids in Tea Plant-Associated Rhabdo-like Virus 1

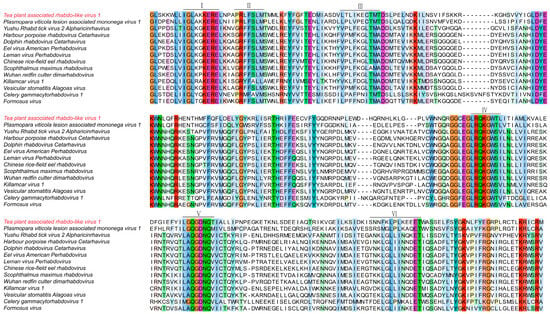

To examine sequence conservation and structural features of Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1 (TeaRLV1), we conducted multiple sequence alignment using its deduced viral protein amino acid sequences along with fifteen related rhabdoviruses/rhabdo-like viruses (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Multiple sequence alignment of amino acid sequences from Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1.

The alignment revealed conserved residues across functional domains II to VI, with the greatest conservation observed in Domains III and IV. Motifs such as GLKGKER, FFSLMSWELREY, and TMADDMTEV were shared by several viruses. TeaRLV1 exhibited high sequence similarity in these regions, particularly with the plant-associated Plasmopara viticola lesion-associated mononega virus 1 (GenBank: QHD64769). Strong conservation was evident in the GLSKKWL motif within Domain III and in the DFGIEF-associated cluster within Domain V, indicating retention of structural elements critical for plant-infecting rhabdoviruses. In contrast, TeaRLV1 showed distinct divergence from rhabdoviruses derived from animal and aquatic hosts. Variations were mainly observed in Domain II, where 3–5 amino acid substitutions occurred, and Domain VI, which contained short insertions or deletions of 4–6 residues. For instance, comparison with Harbour porpoise rhabdovirus (YP_009362243.1) and Scophthalmus maximus rhabdovirus (YP_009094346) highlighted unique substitution and deletion patterns in TeaRLV1. Minor differences at key residues in Domain IV further distinguished TeaRLV1 from other plant-infecting rhabdoviruses, including Celery gammacytorhabdovirus 1 (DBA36859) and Formosus virus (XUU16250), suggesting ongoing lineage-specific evolutionary changes. Taken together, these analyses demonstrate that TeaRLV1 retains hallmark rhabdo-like features while exhibiting unique sequence adaptations. This provides strong support for its taxonomic placement and offers a foundation for future functional studies and investigations into host–virus interactions in tea plants.

4. Discussion

Tea ranks among the most economically vital cash crops globally, cherished for its array of bioactive compounds with health-promoting properties [38,39,40]. However, sustainable tea cultivation faces persistent threats from a suite of biotic stresses, including fungal, bacterial, and viral pathogens, which collectively impair plant growth, reduce yield, and degrade product quality [41,42,43]. Although RNA sequencing has facilitated the discovery of several viruses in tea plants, including Tea plant necrotic ring blotch virus (TPNRBV) and Tea plant line pattern virus (TPLPV), comprehensive profiling of the tea virome remains limited, restricting our understanding of factors influencing tea health and productivity [44,45,46]. Therefore, elucidating the diversity and characteristics of viruses affecting tea is essential for advancing plant virology and improving breeding strategies.

In the present study, ribodepleted transcriptome sequencing combined with de novo transcriptome assembly was employed to dissect the viral diversity in eighteen tea cultivars exhibiting typical leaf discoloration symptoms, sampled from the Institute of Fruit and Tea, Hubei Academy of Agricultural Sciences. A total of twenty viral species were identified, five of which are known to be specific to tea plants or closely related Camellia species. Notably, TPNRBV emerged as the dominant viral component in Pools A and B, accounting for 74.9% and 34.5% of viral reads, respectively, consistent with previous reports highlighting TPNRBV as a widespread pathogen threatening tea plantations in China, Iran, and Japan [16,17,18,19]. In Pool A, TPNRBV was accompanied by minor proportions of Caulimovirus glycinis (1.9%) and Piper DNA virus_1 (1.2%), while Tea-oil camellia-associated totivirus_1 and Oil tea associated geminivirus constituted less than 0.5% of the viral community. Pool B exhibited greater viral complexity, with Badnavirus beta colocasiae (24.9%) and Ocimum basilicum RNA virus_2 (6.4%) as secondary dominant species, alongside several low-abundance tea-specific viruses. In contrast, Pool C harbored several viral taxa not detected in Pools A or B, including Oil tea-associated geminivirus, Riboviria sp., and a markedly higher abundance of Badnavirus beta colocasiae (53.09%). This pronounced divergence in viral composition may, in part, be attributable to potential contamination or other technical artefacts introduced during library construction or sequencing. Nevertheless, these possibilities cannot be fully resolved based on the current dataset. To ascertain whether the viral signatures observed in Pool C reflect true biological infection or non-biological artefacts, independent validation will be essential.

This inter-pool variation in viral prevalence-particularly the cultivar-specific distribution of certain viruses-suggests that both genetic background of tea cultivars and environmental factors may drive viral community assembly. The consistent dominance of TPNRBV in Pools A and B aligns with its documented high transmissibility via mechanical means and potential seed-borne transmission [19], reinforcing its status as a primary threat to tea production. Furthermore, the detection of non-tea-specific viruses (e.g., Caulimovirus glycinis, Piper DNA virus, Badnavirus beta colocasiae) implies cross-host transmission risks, possibly mediated by insect vectors or shared agricultural practices. These findings extend prior observations of tea virome diversity [15,21,23] by demonstrating the structured nature of viral communities across genetically distinct cultivars, underscoring the imperative of cultivar-specific surveillance to mitigate viral spread.

To obtain a preliminary overview of the potential functional attributes of viral communities in tea plants, we performed GO enrichment analysis on vOTU-associated genes across the three sample pools. Although this analysis provides an initial reference for the putative molecular features of the viral communities, the limited functional annotation is available for viral genes. Broadly, vOTUs from all pools showed enrichment in general categories such as catalytic activity, binding functions, and metabolic processes, which are commonly associated with core viral replication and host interaction mechanisms [47,48,49]. However, several enriched terms appeared inconsistent with plant-associated viruses, highlighting the known limitations of GO-based functional assignments for viral genomes and the risk of cross-kingdom annotation transfer leading to misleading terms [50,51]. Consequently, pool-specific differences observed in GO patterns, including those in Pool C, cannot at present be confidently attributed to meaningful biological variation among tea cultivars. Rather than providing definitive functional interpretations, these GO profiles serve only as an exploratory framework outlining possible functional tendencies of the detected viral genes. Future research incorporating targeted experimental validation-such as functional domain verification.

A key novelty of this study lies in the identification and characterization of two previously undescribed viruses: Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1 (TeaOLV1) and Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1 (TeaRLV1). Phylogenetic analysis placed TeaOLV1 within the genus Penoulivirus, clustering with plant-derived ourmia-like viruses such as Botrytis cinerea ourmia-like virus 4 and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum ourmia-like virus 1-supporting evolutionary conservation of this viral genus in plant hosts. Similarly, a recent study reported a related viral species, a novel mycovirus designated Colletotrichum camelliae botourmiavirus 1 (CcBV1) isolated from C. camelliae, whose phylogenetic reconstruction placed it within the Penoulivirus clade of the family Botourmiaviridae, thereby reinforcing the expanding genetic diversity and host range of penouliviruses [52]. TeaRLV1, by contrast, formed a distinct monophyletic clade within plant-associated rhabdoviruses, showing clear genetic divergence from animal- and aquatic host-derived rhabdoviruses. This pattern of host-specific clustering is consistent with the hypothesis of host-adaptive evolution within the Rhabdoviridae family, wherein viral lineages undergo functional specialization to colonize distinct host groups [53,54,55]. Conserved domain analysis further revealed that both novel viruses retain canonical motifs of their respective viral families while harboring tea plant-specific sequence variations-molecular signatures likely reflecting long-term co-evolution with Camellia sinensis. These findings expand the known virosphere of tea plants and refine the taxonomic framework of plant-infecting ourmia-like viruses and rhabdoviruses.

Despite these advances, several limitations should be acknowledged when interpreting the present findings. The pooled sampling design, although effective for broad virome profiling, may obscure subtle cultivar-dependent viral dynamics and restrict our ability to resolve intraspecific variation in viral communities. Additionally, the biological relevance of the newly identified TeaOLV1 and TeaRLV1 remains uncertain, as their pathogenicity and potential involvement in leaf discoloration have not yet been validated through controlled mechanical inoculation assays. Moreover, the detection of viruses not typically associated with tea plants raises questions regarding their ecological origins and transmission pathways, suggesting the possibility of cross-host infection mediated by insect vectors, neighboring vegetation, or environmental reservoirs. Resolving these uncertainties will require a combination of full-length genome cloning, pathogenicity verification through standardized inoculation experiments, and comprehensive field surveys to characterize the geographic distribution and transmission dynamics of the identified viruses. Such integrated efforts will not only refine our understanding of tea-associated viral ecology but also provide essential scientific support for developing targeted diagnostic tools and effective disease management strategies, ultimately contributing to the sustainable cultivation of tea.

In summary, this study provides a comprehensive characterization of the virome across genetically distinct tea cultivars, uncovering both community composition and functional potential, and identifying two novel viruses that expand the known diversity of plant-associated ourmia-like viruses and rhabdoviruses. Our results highlight the influence of cultivar genetics and environmental factors on viral community assembly, while emphasizing the need for complete genome sequencing, pathogenicity assessment, and extensive field surveys to clarify host specificity and transmission dynamics. Collectively, these findings establish a foundation for refining viral taxonomy, enhancing diagnostic accuracy, and informing the integration of viral resistance traits into breeding programs, thereby contributing to the sustainable management and long-term productivity of tea cultivation.

5. Conclusions

In our study conducted at the Hubei Province Tea Germplasm Resources Nursery in China, we meticulously selected and grouped eighteen tea plant leaves displaying typical leaf discoloration symptoms into three pools, representing diverse genetic backgrounds. Through thorough transcriptome sequencing and subsequent bioinformatics analyses, we gained valuable insights into the viral landscape affecting tea plants. Our findings revealed distinct viral community structures across pools: Tea plant necrotic ring blotch virus (TPNRBV) was the dominant species in Pools A and B, while Badnavirus betacolocalasiae prevailed in Pool C. GO enrichment analysis showed vOTU genes were functionally enriched in binding, catalytic activities, and multi-organism interactions-key processes supporting viral replication and host interaction. Two novel viruses were identified: Tea plant-associated ourmia-like virus 1 (TeaOLV1) clustered within the Penoulivirus genus, and Tea plant-associated rhabdo-like virus 1 (TeaRLV1) formed a unique clade with plant-derived rhabdoviruses. These findings expand the known viral diversity of Camellia sinensis, clarify the taxonomic status of the two novel viruses, and provide molecular insights into tea plant-virus interactions. They also lay a critical foundation for developing targeted viral detection methods and integrated disease management strategies, supporting sustainable tea production.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijpb16040141/s1, Figure S1: Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of virus operational taxonomic unit (vOTU) genes in Pool A; Figure S2: Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of virus operational taxonomic unit (vOTU) genes in Pool B; Figure S3: Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of virus operational taxonomic unit (vOTU) genes in Pool C; Table S1: Summary of virus information identified in Pool A; Table S2: Summary of virus information identified in Pool B; Table S3: Summary of virus information identified in Pool C. Sequences S1: RNA sequences of the two novel viruses identified in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T.; methodology, X.C. and H.W.; software, X.C. and H.W.; validation, P.W. and D.H.; formal analysis, R.T. and P.W.; investigation, X.C. and H.W.; resources, H.W.; data curation, L.J. and D.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T.; writing—review and editing, L.J. and Y.M.; visualization, D.H.; supervision, L.J. and Y.M.; project administration, Y.M.; funding acquisition, Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2021YFD1601100), the China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (CARS-19), the Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Plan Project (2025BBB035) and the Innovation Center Fund for Agricultural Science and Technology in Hubei Province of China (2023-620-005-001).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. All sequencing datasets have been in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject ID PRJNA1088897.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, H.; Long, X.; Geng, Y. Companion Plants of Tea: From Ancient to Terrace to Forest. Plants 2023, 12, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.L.; Shih, L.C.; Yeh, W.B.; Byun, B.K.; Jinbo, U.; Ning, F.Y.; Sung, I.H. Genetic Differentiation and Species Diversification of the Adoxophyes orana Complex (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) in East Asia. J. Econ. Entomol. 2023, 116, 1885–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Rawat, N.; Thakur, S.; Joshi, R.; Pandey, S.S. A Highly Efficient Protocol for Isolation of Protoplast from China, Assam and Cambod Types of Tea Plants [Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze]. Plant Methods 2023, 19, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nhu-Trang, T.T.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Cong-Hau, N.; Anh-Dao, L.T.; Behra, P. Characteristics and Relationships between Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Contents, Antioxidant Capacities, and the Content of Caffeine, Gallic Acid, and Major Catechins in Wild/Ancient and Cultivated Teas in Vietnam. Molecules 2023, 28, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isoda, M.; Kondo, T.; Suzuki, R.; Takeda, S. Change in Anthropogenic Disturbances and Its Influence on Wild Tea Survival in Shiiba, Japan. Econ. Bot. 2022, 76, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.J.; Zhao, S.Y.; Gao, Y.; Shen, X.Y.; Hou, C.L. A Phylogenetic and Taxonomic Revision of Discula Theae-Sinensis, the Causal Agents of Anthracnose on Camellia sinensis. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.X.; Deng, X.Y.; Tong, H.R.; Chen, Y.J. Effect of Blister Blight Disease Caused by Exobasidium on Tea Quality. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Rai, M.; Das, D.; Chandra, S.; Acharya, K. Blister Blight a Threatened Problem in Tea Industry: A Review. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 3265–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Ji, C.Y.; Li, W.; Fen, X.; Wang, Z.Z. Identification of the Pathogen Responsible for Tea White Scab Disease. J. Phytopathol. 2020, 168, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Tang, J.W.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.Y. Intercropped Flemingia Macrophylla Successfully Traps Tea Aphid (Toxoptera aurantia) and Alters Associated Networks to Enhance Tea Quality. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 1474–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Long, H.; Huo, D.; Awan, M.; Shao, J.H.; Mahmood, A.; Liu, S.; Huang, J.Q.; Parveen, A.; Aamer, M. Insights into the Functional Role of Tea Microbes on Tea Growth, Quality and Resistance against Pests and Diseases. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. 2022, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Q.; Gu, Q.Y.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, H.Y.; Chen, S.C.; Smagghe, G.; Niu, J.Z.; Wang, J.J. Prevalence of a Novel Bunyavirus in Tea Tussock Moth Euproctis pseudoconspersa (Lepidoptera: Lymantriidae). J. Insect Sci. 2021, 21, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, P.; Dai, J.X.; Guo, G.Y.; Wang, Z.H.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Chen, H.P. Residue Pattern of Chlorpyrifos and Its Metabolite in Tea from Cultivation to Consumption. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 4134–4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaihatsu, K.; Yamabe, M.; Ebara, Y. Antiviral Mechanism of Action of Epigallocatechin-3-O-Gallate and Its Fatty Acid Esters. Molecules 2018, 23, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.Y.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhao, F.M.; Liu, Y.; Qian, W.J.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, L.; Zeng, J.M.; Yang, Y.J.; Wang, X.C. Discovery of Plant Viruses From Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) by Metagenomic Sequencing. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Shen, J.G.; Li, M.; Gao, Y.J.; Du, Z.G.; Gao, F.L. The Occurrence and Genetic Variability of Tea Plant Necrotic Ring Blotch Virus in Fujian Province, China. Forests 2023, 14, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, N.; Iwabuchi, N.; Nishikawa, M.; Nijo, T.; Yoshida, T.; Kitazawa, Y.; Maejima, K.; Namba, S.; Yamaji, Y. Complete Genome Sequence of Tea Plant Necrotic Ring Blotch Virus Detected from a Tea Plant in Japan. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2022, 11, e0032322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazerian, E.; Bayat, H. Occurrence of Tea Plant Necrotic Ring Blotch Virus in Iran. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2021, 61, 200–202. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Ghorbani, A.; Koolivand, D. Molecular and Biological Investigating of Tea Plant Necrotic Ring Blotch Virus as a Worldwide Threat. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, F.M.; Ding, C.Q.; Zhang, K.X.; Wang, L.; Yang, Y.J.; Hao, X.Y.; Wang, X.C. Quantitative Distribution and Transmission of Tea Plant Necrotic Ring Blotch Virus in Camellia sinensis. Forests 2022, 13, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, D.K.; Dong, Q.; Jegede, O.J.; Wu, Q.F. Complete Genome Sequence of a New Badnavirus Infecting a Tea Plant in China. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 2811–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.P.; Du, Y.M.; Xiao, H.; Peng, L.; Li, R. Complete Genomic Sequence of Tea-Oil Camellia Deltapartitivirus 1, a Novel Virus from Camellia oleifera. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Cho, W.K. Identification of Viruses Belonging to the Family Partitiviridae from Plant Transcriptomes. BioRxiv 2020, 10, 1101. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeilzadeh, F.; Ghorbani, A.; Koolivand, D. First Report of Camellia oleifera Amalgavirus 1 Associated with Tea Plant in Iran. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, H.L.; Chen, C.S.; Yue, C.A.; Hao, X.Y.; Yang, Y.J.; Wang, X.C. Complementary Transcriptomic and Proteomic Analyses of a Chlorophylldeficient Tea Plant Cultivar Reveal Multiple Metabolic Pathway Changes. J. Proteom. 2016, 130, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.H.; Hur, J.; Ryu, C.H.; Choi, Y.; Chung, Y.Y.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H.; An, G. Characterization of a Rice Chlorophyll-Deficient Mutant Using the T-DNA Gene-Trap System. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissler, H.M.; Collakova, E.; DellaPenna, D.; Whelan, J.; Pogson, B.J. Chlorophyll Biosynthesis. Expression of a Second Chl I Gene of Magnesium Chelatase in Arabidopsis Supports Only Limited Chlorophyll Synthesis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 128, 770–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mochizuki, N.; Brusslan, J.; Larkin, R.; Nagatani, A.; Chory, J. Arabidopsis Genomes Uncoupled 5 (GUN5) Mutant Reveals the Involvement of Mg-Chelatase H Subunit in Plastid-to-Nucleus Signal Transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 2053–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papenbrock, J.; Pfündel, E.; Mock, H.; Grimm, B. Decreased and Increased Expression of the Subunit CHL I Diminishes Mg Chelatase Activity and Reduces Chlorophyll Synthesis in Transgenic Tobacco Plants. Plant J. 2000, 22, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudoi, A.; Shcherbakov, R. Analysis of the Chlorophyll Biosynthetic System in a Chlorophyll b-Less Barley Mutant. Photosynth. Res. 1998, 58, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Song, X.H.; Shi, X.G.; Li, J.X.; Ye, C.X. An Improved HPLC Method for Simultaneous Determination of Phenolic Compounds, Purine Alkaloids and Theanine in Camellia Species. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2008, 21, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P.L.; Huang, Y.N.; Marchese, J.N.; Williamson, B.; Parker, K.; Hattan, S.; Khainovski, N.; Pillai, S.; Dey, S.; Daniels, S.; et al. Multiplexed Protein Quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Using Amine-Reactive Isobaric Tagging Reagents. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2004, 3, 1154–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.C.; Yue, C.A.; Cao, H.l.; Zhou, Y.H.; Yang, Y.J. Development of a 44K Custom Olligo Microarray Using 454 Pyrosequencing Data for Large-Scale Gene Expression Analysis of Camellia sinensis. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 174, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Chen, L.; Ma, C.L.; Yao, M.Z.; Yang, Y.J. Genotypic Variation of Beta-Carotene and Lutein Contents in Tea Germplasms, Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2010, 23, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiumenti, M.; Morelli, M.; Giampetruzzi, A.; Palmisano, F.; Savino, V.N.; Notte, P.L.; Martelli, G.P.; Saldarelli, P. First Report of Grapevine Roditis Leaf Discoloration-Associated Virus in Italy. J. Plant Pathol. 2015, 97, 541–551. [Google Scholar]

- Roossinck, M.J. Lifestyles of Plant Viruses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 1899–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, W.S.; Zhu, T.T.; Chen, W.L.; Ye, T.; Sun, Q.Y.; Zhang, J.X. Advances in the Study of Viral Diseases Affecting Camellia Species. China Acad. J. 2024, 44, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.M. Anti-Infective Potential of Catechins and Their Derivatives against Viral Hepatitis. Clin. Exp. Vaccine Res. 2018, 7, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, W.M. A Review of the Antiviral Role of Green Tea Catechins. Molecules 2017, 22, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, B.M.; Batista, M.N.; Braga, A.C.S.; Nogueira, M.L.; Rahal, P. The Green Tea Molecule EGCG Inhibits Zika Virus Entry. Virology 2016, 496, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Nath, A.; Thakur, D. Identification and Characterization of Fungi Associated with Blister Blight Lesions of Tea (Camellia sinensis L. Kuntze) Isolated from Meghalaya, India. Microbiol. Res. 2020, 240, 126561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Hao, X.Y.; Wang, L.; Xiao, B.; Wang, X.C.; Yang, Y.J. Diverse Colletotrichum Species Cause Anthracnose of Tea Plants (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) in China. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomihama, T.; Nonaka, T.; Nishi, Y.; Arai, K. Environmental Control in Tea Fields to Reduce Infection by Pseudomonas syringae Pv. Theae. Phytopathology 2009, 99, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, P.; Charlesdominique, T.; Barakat, M.; Ortet, P.; Fernandez, E.; Filloux, D.; Hartnady, P.; Rebelo, T.A.; Cousins, S.R.; Mesleard, F.; et al. Geometagenomics Illuminates the Impact of Agriculture on the Distribution and Prevalence of Plant Viruses at the Ecosystem Scale. ISEM J. 2017, 12, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadidi, A.; Flores, R.; Candresse, T.; Barba, M. Next-Generation Sequencing and Genome Editing in Plant Virology. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roossinck, M.J.; Martin, D.P.; Roumagnac, P. Plant Virus Metagenomics: Advances in Virus Discovery. Phytopathology 2015, 105, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriari, A.G.; Tahmasebi, A.; Ghodoum Parizipour, M.H.; Soltani, Z.; Tahmasebi, A.; Shahid, M.S. The Crucial Role of Mitochondrial/Chloroplast-Related Genes in Viral Genome Replication and Host Defense: Integrative Systems Biology Analysis in Plant-Virus Interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1551123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemes, K.; Gellért, Á.; Almási, A.; Vági, P.; Sáray, R.; Kádár, K.; Salánki, K. Phosphorylation Regulates The Subcellular Localization of Cucumber Mosaic Virus 2b Protein. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.J.; Huang, Y.W.; Liou, M.R.; Lee, Y.C.; Lin, N.S.; Meng, M.; Tsai, C.H.; Hu, C.C.; Hsu, Y.U. Phosphorylation of Coat Protein by Protein Kinase CK2 Regulates Cell-to-Cell Movement of Bamboo Mosaic Virus Through Modulating RNA Binding. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2014, 27, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfaçon, H. Grand Challenge in Plant Virology: Understanding the Impact of Plant Viruses in Model Plants, in Agricultural Crops, and in Complex Ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.J.; Guo, X.; Gu, T.X.; Xu, X.W.; Qin, L.; Xu, K.; He, Z.; Zhang, K. Phosphorylation of Plant Virus Proteins: Analysis Methods and Biological Functions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 935735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.W.; Hai, D.; Li, J.C.; Huang, F.X.; Wang, Y.X. Molecular Characterization of a Novel Penoulivirus from the Phytopathogenic Fungus Colletotrichum camelliae. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longdon, B.; Murray, G.G.; Palmer, W.J.; Day, J.P.; Parker, D.J.; Welch, J.J.; Obbard, D.J.; Jiggins, F.M. The Evolution, Diversity, and Host Associations of Rhabdoviruses. Virus Evol. 2015, 1, vev014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Novella, I.S.; Dietzgen, R.G.; Padhi, A.; Rupprecht, C.E. The Rhabdoviruses: Biodiversity, phylogenetics, and evolution. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2009, 9, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietzgen, R.G.; Kondo, H.; Goodin, M.M.; Kurath, G.; Vasilakis, N. The Family Rhabdoviridae: Mono-and Bipartite Negative-Sense RNA Viruses with Diverse Genome Organization and Common Evolutionary Origins. Virus Res. 2017, 227, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).