Abstract

Commiphora leptophloeos, a native Caatinga species with economic and medicinal potential, faces propagation challenges due to seed dormancy and extractive use. The germination test, the official method for seed quality assessment, is time-consuming, whereas the tetrazolium test (TZT) offers a rapid alternative for determining seed viability. This study aimed to establish and validate a TZT protocol for C. leptophloeos seeds. Seeds collected in 2025 were extracted after natural fruit drying and then stored in a cold chamber. The germination test was conducted with seeds without pyrenes at 30 °C. For the TZT, a completely randomized design was used in a 6 × 4 factorial scheme (six TZT concentrations × four immersion times), with adjustments in seed preparation and staining procedures. Higher concentrations (0.5% and 0.75%) combined with shorter immersion periods (2 h) provided the best results, especially 0.75% for 2 h, which yielded 89% viability. Very low concentrations combined with short periods resulted in little or no staining. Compared with the germination test (35%), the TZT showed greater sensitivity in detecting viable seeds. We conclude that the TZT is highly efficient for assessing the viability of C. leptophloeos seeds, with optimal responses at 0.5–0.75% TTC and 2–4 h immersion periods, and represents a strategic tool to support the conservation and sustainable use of this species.

1. Introduction

Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett (Burseraceae), commonly known as “umburana-de-cambão” or “imburana-vermelha”, is a tree species of high ecological and socioeconomic relevance in the Caatinga biome of northeastern Brazil. It has multiple uses, including artisanal, medicinal, melliferous, and forage applications, and its bark is traditionally used in teas and syrups to treat respiratory diseases such as flu, cough, and bronchitis [1]. The species predominantly occurs in arboreal–shrubby Caatinga on calcareous soils, especially in the Sub-medium São Francisco Valley [2]. The fruits are drupes containing a single pyrene surrounded by a red pseudoaril, which favors zoochorous dispersal by birds and lizards [3]. Despite its importance, the Caatinga still lacks official ISTA rules for seed germination and viability testing, highlighting the need for validated methodologies tailored to native species from this seasonally dry tropical forest.

Despite its ecological, economic, and cultural significance, C. leptophloeos has been subjected to intense anthropogenic pressure. Honey extraction by burning tree trunks has markedly reduced natural populations and degraded habitats used by bees for shelter and nesting [4]. Seed propagation is further hindered by mechanical dormancy imposed by the woody endocarp and by intense seed predation by goats. In Burseraceae, mechanical dormancy acts in combination with deep physiological dormancy, together contributing to slow and irregular germination [5]. Although vegetative propagation is technically feasible, it produces clonal individuals and, consequently, reduces genetic variability at the population level, making this strategy unsuitable for ecological restoration. Low genetic diversity compromises ecological resilience and increases vulnerability to pests and diseases [6].

Germination tests remain the standard and essential method for evaluating seed physiological quality, as they reflect the actual germination capacity under defined conditions. However, a major limitation of the germination test is the relatively long time required to obtain results, which can delay seed quality control and seedling production programs. In this context, the tetrazolium test (TZT) functions as a complementary, rather than substitutive, method to the standard germination test. The TZT provides rapid information on seed viability and helps clarify the true viability of seed lots, especially when seed quantity is limited or dormancy is present. Nevertheless, TZT results indicate only potential germination capacity, and germination tests remain necessary to determine actual germination performance [7]. The TZT is based on the activity of dehydrogenase enzymes involved in cellular respiration, which reduce 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride to triphenyl formazan, a red compound that accumulates in living tissues and allows visual distinction between viable (crimson-red) and non-viable (milky-white) tissues [8]. To ensure reliable results, procedures such as pre-conditioning, appropriate cutting of seeds, and adequate temperature and exposure time are required to promote uniform reagent penetration and accurate interpretation of staining patterns [8].

Although the TZT is widely established for agricultural and many forest species, no studies have reported its use for seeds of C. leptophloeos, representing a relevant scientific gap given the ecological and socioeconomic potential of this species. We hypothesize that the TZT is a rapid and efficient method for accurately assessing the viability of C. leptophloeos seeds, even in the presence of mechanical and physiological dormancy, and that its results are consistent with those obtained in the germination test, thereby providing insights to improve propagation and conservation strategies. Therefore, this study aimed to establish and validate a TZT protocol for evaluating the viability of C. leptophloeos seeds, contributing to the conservation, management, and sustainable use of this important Caatinga species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Seed Collection and Preparation

Fruits of Commiphora leptophloeos were collected in March 2025 in the village of Jutaí, municipality of Lagoa Grande, Pernambuco, Brazil. Collection was carried out manually from 18 mother trees selected based on size, vigor, and apparent health. All fruits from these 18 trees were pooled, and after drying and seed extraction, the seeds were thoroughly mixed to form a single homogeneous experimental lot (composite sample). This composite lot was used in all germination and tetrazolium tests, without distinction among individual mother trees.

The fruits, initially greenish-brown, were placed on benches and dried at room temperature for 20 days. After drying, the seeds were extracted and stored in a cold chamber at 10 ± 3 °C and 60 ± 4% relative humidity. The seeds remained under these refrigerated conditions for approximately two months between collection and the beginning of the experiments, and they were kept in the cold chamber until the setup of each germination and tetrazolium test.

2.2. Seed Moisture Content (%)

Seed moisture content was determined using two subsamples of 50 seeds each. The seeds were placed in aluminum capsules and dried in an oven at 105 ± 3 °C for 24 h. Results were expressed as a percentage based on the fresh mass of the seeds [9].

2.3. Germination Test (G%)

Germination was evaluated using four replicates of 20 seeds each, manually extracted from the pyrene with complete removal of both the endocarp and the seed coat (testa). Thus, only fully cleaned seeds (Figure 1C), consisting solely of the embryo and cotyledons, were used in the experiment. After extraction, the seeds were placed in transparent crystal polyethylene boxes (11 cm × 11 cm × 3.5 cm) on two sheets of blotting paper moistened with distilled water in an amount equivalent to 2.5 times the dry mass of the paper [9]. The boxes were kept in germination chambers (B.O.D. type) maintained at 30 °C. Germination percentage was assessed 21 days after the start of the test, considering seeds with radicle protrusion ≥ 2 mm as germinated. No dormancy-breaking pretreatments (such as scarification, stratification, hormone application, or prior imbibition) were applied; seeds were germinated under control conditions only, after removal of the endocarp and seed coat.

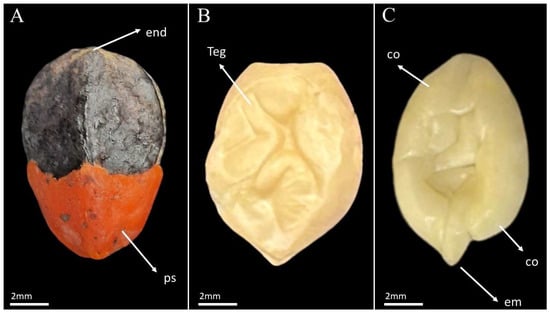

Figure 1.

Pyrene of Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett. (A) External view of the pyrene, showing the presence of the red pseudoaril in the basal region (ps) and the woody endocarp (end). (B) Seed with adherent testa (teg). (C) Seed without testa, showing the cotyledons (co) and the embryo (em).

2.4. Tetrazolium Test (TZT)

Before performing the definitive tetrazolium test (TZT), preliminary assays were conducted to adjust the most appropriate methodological conditions for the species. Initially, different tetrazolium reagent concentrations and exposure times were tested to determine the most efficient combination for staining viable tissues. We also evaluated the need to remove the endocarp and seed coat (Figure 1), as these structures hindered reagent penetration and the visualization of internal seed structures.

For the definitive TZT, we used the same fully cleaned seeds described for the germination test (Section 2.3), i.e., seeds extracted from the pyrenes with complete removal of both the endocarp and the seed coat. Before immersion in tetrazolium solution, the seeds were preconditioned at 30 °C for 1 h in polyethylene boxes, in direct contact with blotting paper moistened with distilled water (preconditioning in water only, not in tetrazolium solution).

For the tetrazolium test, a 1% (w/v) stock solution of 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TZT) (Neon Comercial Reagentes Analíticos Ltda., Suzano, SP, Brazil) was prepared by dissolving 10 g of TZT in 1 L of distilled water under magnetic stirring until complete dissolution. From this stock, working solutions for each treatment were freshly prepared by dilution in distilled water immediately before each staining assay. The solutions were placed in amber glass flasks, kept refrigerated and protected from light during handling, and were not stored for use on subsequent days.

The experiment followed a completely randomized design (CRD) in a 6 × 4 factorial scheme, corresponding to six TTC concentrations (0.01%, 0.05%, 0.075%, 0.1%, 0.5%, and 0.75%) and four immersion times (1, 2, 3, and 4 h), with four replicates of 10 seeds per treatment. After preconditioning, the seeds were fully submerged in the different tetrazolium solutions and incubated at 30 °C in a B.O.D. incubator, in complete darkness, for the immersion period assigned to each treatment. Subsequently, the seeds were rinsed under running water, dried on paper towels, examined under a Leica M125 C stereomicroscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), and documented by photographs.

For seed viability assessment, both tissue turgidity (cotyledons and embryo) and tetrazolium staining patterns were considered, including the extent, position, intensity, and uniformity of the crimson-red coloration, as well as the presence of milky-white areas [9]. After careful evaluation, seeds were classified into two categories: (i) viable: embryos uniformly stained bright red/carmine, with firm and turgid tissues and no whitish or necrotic areas, and (ii) non-viable: embryos showing no staining, very weak or patchy staining, burst-like staining, or whitish/grayish tissues indicative of necrosis. All TZT evaluations were performed independently by two trained assessors.

2.5. Analysis of the Data

The normality of residuals for seed viability percentage was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test [10], and homogeneity of variances was verified using Levene’s test [11]. Because the residuals were non-normal and we chose not to apply an angular transformation, data analysis was performed using generalized linear models (GLMs). The error distribution and link function were selected for each response variable according to data behavior and goodness of fit. Viability percentage was analyzed assuming a binomial distribution with a logit link, which provided the best fit to the response pattern [12].

Model fit and robustness were evaluated using specific diagnostic routines in R. The car package [13] was used for analysis of deviance, ensuring invariance with respect to the order of entry of variables in the calculation of p-values, and for monitoring multicollinearity and detecting potential outliers. Additional tests of residual normality were obtained using the nortest package [14], and generalization capacity and predictive accuracy were estimated by cross-validation using the boot package [15].

Deviance analysis (ANODEV) was used to test the significance of the main factors (tetrazolium solution concentration and exposure time) and their interaction, with inferences based on the F statistic and a significance level of α = 0.05. After model fitting and confirmation of significance at α = 0.05, differences among concentrations and immersion times were evaluated using Tukey’s post hoc test (α = 0.05). Estimated means were obtained with the emmeans package [16], and simultaneous inference and multiple pairwise comparisons were performed with the multcomp package [17]. Distinct statistical groups were represented by compact letter displays generated by the multcompView package [18]. To validate the methodology, viability values obtained by the TZT were compared with germination results using Dunnett’s test (α = 0.05) [19], allowing contrasts between the control treatment and the other levels. In all statistical analyses, the significance level was set at α = 0.05. All analyses were performed in R software [20].

3. Results and Discussion

The seed water content determined prior to the application of the tetrazolium test was 6.53%. This low moisture level at dispersal falls within the range reported for orthodox seeds from seasonally dry environments, which are typically shed with relatively low water contents and high desiccation tolerance [5,21,22]. Thus, this moisture content is not expected to be detrimental to germination; rather, it is consistent with orthodox seed storage behavior. The low water content is compatible with refrigerated storage and favorable for TZT staining, as it reduces the risk of fermentation and reading artifacts. Seed water content is directly related to several factors that influence physiological quality [23] and is considered one of the most relevant physiological parameters, as it affects respiration, viability, vigor, and germination performance, and is therefore essential for seed conservation and assessment of physiological quality [24].

In the preliminary tests, the stony endocarp and the seed coat clearly acted as mechanical barriers, preventing adequate penetration of the tetrazolium solution and hindering the assessment of seed viability. Removal of these structures was therefore essential to obtain uniform staining patterns and reliable interpretation of the TZT. However, even after endocarp removal, germination remained low (35%). If dormancy were solely due to mechanical constraint, a substantial increase in germination would be expected once the endocarp was eliminated. The persistence of low germination in de-coated seeds indicates the presence of a physiological component of dormancy in addition to the mechanical barrier imposed by the endocarp and seed coat, a finding consistent with reports for Burseraceae [5]. With respect to preconditioning, placing the seeds on blotting paper moistened with distilled water at 30 °C for 1 h provided sufficient hydration to soften the tissues and facilitate tetrazolium penetration. Although the literature often recommends longer preconditioning periods, for this species a 1 h hydration period was enough to allow uniform staining without compromising result interpretation, confirming the importance of preconditioning in softening tissues and ensuring adequate exposure of the embryo to the tetrazolium solution [25].

The seed viability data obtained through the TZT did not meet the statistical assumptions of residual normality (p < 0.05) or homogeneity of variances (p < 0.05) (Table 1). The ANODEV indicated a significant effect of both concentration and time, as well as their interaction (p < 0.001), with the greatest reduction in deviance attributed to concentration, while time additionally contributed to standardizing the staining (Table 1). This pattern reinforces that the TZT response depends on the combined calibration of tetrazolium concentration and exposure time. The high coefficient of variation (45.24%) indicates substantial heterogeneity within the seed lot (Table 1), consistent with the presence of dormancy and with the variability expected for native forest species.

Table 1.

Analysis of deviance (ANODEV) for seed viability (%) of Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett, subjected to the tetrazolium test (TZT) at different concentrations and immersion times.

The analysis of TZT results showed that tetrazolium solution concentration played a decisive role in staining efficiency and, consequently, in determining seed viability. Lower concentrations, such as 0.01% and 0.05%, combined with short exposure times (1 and 2 h), did not produce adequate staining and prevented distinction between viable and non-viable tissues (Table 2). Although at 0.01% some staining was observed in 76% of the seeds after 4 h of immersion, this indicates that low concentrations require longer exposure times to achieve satisfactory coloration. In seeds of Piptadenia stipulacea, [26] observed that staining patterns varied according to tetrazolium concentration (0.05%, 0.075%, and 0.1%) and incubation time (2, 4, and 6 h). Although C. leptophloeos and P. stipulacea differ in fruit and seed morphology, both are woody Caatinga species with orthodox seeds dispersed at low moisture content and bearing rigid protective structures (lignified endocarp or hard seed coat) that act as mechanical barriers and influence both germination and tetrazolium staining patterns.

Table 2.

Viability (%) of Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett (Burseraceae) seeds determined by the tetrazolium test (TZT) at different solution concentrations and immersion times.

Because no dormancy-breaking treatments were applied, the germination percentages obtained in this study should not be interpreted as the maximum germination capacity of C. leptophloeos, but rather as the expression of germination under untreated control conditions. The higher viability revealed by the tetrazolium test is consistent with the presence of physiological dormancy. Future studies are needed to test specific dormancy-alleviation methods and to determine the full germination potential and dormancy characteristics of this species.

In seeds of Cucumis anguria, a 0.05% tetrazolium concentration for 6 h, or 4 h at higher temperatures, ensured adequate staining, whereas 2 h incubation periods, even at different concentrations, did not allow proper evaluation [27]. Similarly, the combination of low tetrazolium concentration and short (2 h) exposure was insufficient to promote clear staining of living tissues, hindering the distinction between viable and non-viable tissues and compromising the accuracy of the test [28].

In our study, intermediate concentrations (0.075% and 0.1%) combined with longer exposure times yielded satisfactory results, with viability estimates of up to 75% (Table 2). Comparable patterns were reported for Senegalia polyphylla seeds, in which a 0.075% concentration with a 6 h immersion time provided viability estimates similar to those obtained with the germination test and was recommended for assessing physiological seed quality [29]. These findings support the view that intermediate TTC concentrations, when combined with appropriate immersion times, are effective for differentiating between viable and non-viable tissues and provide reliable results for seed-viability assessment. The choice of concentration–time combinations should, however, take into account the specific anatomical and physiological characteristics of each species, with the aim of optimizing both the accuracy and efficiency of the TZT.

Higher concentrations (0.5% and 0.75%) produced more uniform staining, with high percentages of viable seeds already observed after 2 h of immersion, especially at 0.75% for 2 h (89% viability). Despite the good performance of 0.5–0.75% for 2–4 h, caution is advised to avoid overstaining (“burst”), which can mask deteriorated tissues and lead to overestimation of viability. The balance between staining intensity and anatomical discernment should guide the final choice of protocol. For example, in Campomanesia phaea seeds, immersion in a 0.75% tetrazolium solution for 4 h resulted in the most uniform staining and the best distinction between viable and non-viable tissues [30].

In the present study, many seeds that did not germinate under control conditions were classified as viable by the TZT, resulting in higher viability estimates with the TZT than with the germination test. A similar pattern was reported for grass seeds [31], in which higher viability detected by the tetrazolium test, compared with the germination test—even when both values were within the limits established by the Association of Official Seed Analysts—was attributed to the presence of dormancy.

The marked gap between the viability estimated by the TZT and the germination percentage suggests that a substantial fraction of C. leptophloeos seeds is viable but dormant. Although specific studies on dormancy in this species are scarce, dormancy is frequently reported in woody species from seasonally dry tropical forests, where the timing of germination is tightly regulated by environmental cues [5]. The presence of a lignified endocarp and rigid protective structures, as observed for C. leptophloeos, is consistent with the occurrence of primary dormancy and the need for specific conditions to promote radicle protrusion [5].

This discrepancy is therefore consistent with a situation in which a large proportion of the seed lot is viable but remains under primary physiological dormancy. The standard germination test records only those seeds that complete radicle protrusion and seedling establishment; thus, dormant seeds with living, intact embryos are counted as non-germinated. In contrast, the TZT bypasses dormancy constraints by cutting and imbibing the seeds and exposing the embryo tissues directly the tetrazolium solution. Additionally, the reduction of tetrazolium chloride to formazan occurs whenever respiratory metabolism and dehydrogenase activity are present, regardless of whether the regulatory balance between ABA and GA under the test conditions is sufficient or not to trigger visible germination. Consequently, the TZT also detects latent viability that is physiologically prevented from being expressed as germination, resulting in higher viability estimates than those obtained with the germination test.

While the germination test resulted in only 35% normal seedlings, the TZT revealed a much higher proportion of viable seeds, indicating its greater sensitivity in detecting viability even in the presence of dormancy mechanisms (Table 2). This behavior is supported by recent studies in other species. For example, [32], working with seeds of Zanthoxylum rhoifolium, which exhibit combined dormancy (physical and physiological), concluded that the TZT is an effective alternative because it allows viability assessment even when germination is hindered by dormancy.

According to the AOSA and ISTA technical manuals, the tetrazolium test is widely recommended for assessing seed viability under dormancy conditions [33,34]. The Rules for Seed Analysis of the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Supply [9] also recognize its applicability, especially in cases of physiological or seed-coat dormancy in which germination may be hindered in conventional tests. In this context, the TZT allows estimation of seed viability based on the metabolic integrity of tissues, even when seeds do not germinate, thereby explaining the occurrence of high viability percentages in the TZT despite low germination rates under otherwise favorable conditions.

The Burseraceae family, to which C. leptophloeos belongs, presents seeds with deep physiological dormancy, which significantly contributes to the slow germination observed in its species. According to [5], this dormancy is associated with internal embryo mechanisms that require specific conditions to be overcome, such as thermal stratification or prolonged periods of after-ripening. Furthermore, these species bear fruits with thick, woody endocarps that act as additional physical barriers, characterizing so-called mechanical dormancy. However, the authors emphasize that, in such cases, mechanical dormancy does not act in isolation but rather as an extension or manifestation of deep physiological dormancy [5]. Thus, delayed germination in Burseraceae results from the interaction between mechanical and physiological constraints, requiring specific treatments to overcome both barriers.

From a physiological perspective, seed dormancy is largely controlled by the balance between abscisic acid (ABA), which promotes dormancy, and gibberellins (GA), which stimulate germination. [35] highlight that high ABA levels and ABA-responsive gene networks established during seed development maintain dormancy and suppress the germination program, whereas GA biosynthesis and signaling are required to overcome this block and initiate embryo growth. In C. leptophloeos, seeds are dispersed at low moisture content in a xeric environment, conditions that are likely to favor ABA accumulation during maturation and to select for mechanisms that delay germination until water availability is adequate. This hormonal context offers a plausible explanation for the presence of viable embryos that do not germinate under the standard germination conditions used in this study.

Alternative explanations for the gap between viability and germination were also considered. A purely mechanical dormancy imposed by the sclerified endocarp cannot be completely ruled out; however, the TZT directly assesses the embryo tissues, and the high proportion of uniformly carmine-red embryos indicates that water uptake and tetrazolium penetration were sufficient and that the internal tissues are metabolically active [33,34,36]. Likewise, extensive embryo damage not detected by the TZT appears unlikely, as non-viable seeds exhibited clear deviations from the typical staining pattern, including pale, yellowish or irregularly dark regions indicative of tissue deterioration [32,33,34,36]. The potential role of chemical inhibitors, such as endogenous ABA or other growth-inhibiting compounds, may contribute to the maintenance of dormancy, but would not prevent the dehydrogenase activity detected by the TZT [35,37]. Finally, adverse storage effects are also an unlikely main cause, because the seeds were stored for only about two months under cold, dry conditions suitable for orthodox seeds [21,38], and no widespread deterioration was observed in the tetrazolium test. Taken together, these lines of evidence support the interpretation that the discrepancy between TZT viability and germination in C. leptophloeos is primarily associated with physiological dormancy rather than with mechanical restriction, undetected embryo damage, inhibitor-induced inviability, or storage-related loss of quality.

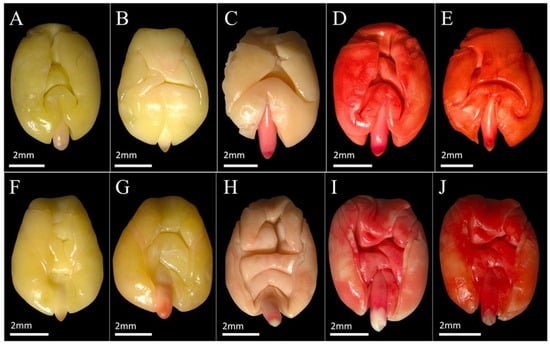

In the broader context of seed testing, the TZT complements—but does not replace—other standard methods of viability assessment, such as the germination test, X-ray analysis, and electrical conductivity tests [33,34]. Unlike X-ray, which primarily reveals structural damage in dry seeds, and electrical conductivity, which is especially suitable for detecting membrane leakage in large, imbibed seeds of agricultural crops, the TZT directly visualizes metabolic activity in embryo tissues through dehydrogenase activity. This makes the TZT particularly informative for small lots of native forest species with dormancy, in which germination may remain low even when embryos are structurally intact and metabolically active. On the other hand, the TZT is not infallible: seeds with staining restricted to non-essential tissues or with subtle damage in meristematic regions may occasionally be classified as viable, although their field emergence would be poor. In the present study, we sought to minimize this risk by adopting conservative interpretation criteria, classifying as viable only those embryos with uniform carmine-red coloration in the embryonic axis and cotyledons, and by contrasting these patterns with clearly non-viable staining profiles (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Tetrazolium staining pattern in viable seeds of Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett (Burseraceae). (A–E): dorsal views; (F–J): ventral views. All images illustrate viable embryos, characterized by uniform carmine-red coloration of the embryo and cotyledons. Letters identify different individual seeds and do not represent distinct viability classes or treatments. Scale bar = 2 mm.

Figure 3.

Tetrazolium staining patterns in Commiphora leptophloeos (Mart.) J.B. Gillett (Burseraceae) seeds classified as non-viable. (A–E): dorsal views; (F–J): ventral views. The images illustrate different patterns associated with loss of viability, including embryos with little or no red staining and predominance of yellowish or pale tissues, as well as embryos with irregular, diffuse or excessively dark red staining indicative of tissue deterioration. Letters identify different individual seeds and do not represent distinct treatments. Scale bar = 2 mm.

The results obtained reinforce the relevance of the TZT as a complementary tool to the germination test, especially for species exhibiting physiological dormancy or slow and uneven germination, where standard germination tests may underestimate seed viability. A similar approach was adopted for three stenoendemic species from Mt. Olympus (northern Greece), in which embryo viability assessed by a combination of tetrazolium and Evans blue solutions exceeded 75%, while high germination percentages were only achieved after the application of dormancy-breaking treatments with gibberellic acid [39].

An additional aspect that may influence the expression of dormancy and the performance of the TZT is the post-harvest history of the seeds. In this study, some degree of after-ripening and partial release of dormancy may have occurred during the storage period. Therefore, the results presented here represent a snapshot of the dormancy status of C. leptophloeos seeds under short-term storage, and further studies comparing freshly harvested seeds with seeds stored for different periods would be valuable to determine how robust the proposed TZT conditions are across different storage histories. The relatively high coefficient of variation observed in our data reflects the natural heterogeneity of a tree species native to seasonally dry tropical forests, such as the Caatinga, that is outcrossing and was sampled from multiple mother trees, and highlights both the importance of validating the protocol under realistic variability and the need for caution when extrapolating the exact viability percentages obtained here to other seed lots or collection years.

Taken together, these considerations delineate the scope within which the proposed protocol should be applied. Our validation was conducted on a single composite seed lot collected in one fruiting season, stored for approximately two months under cold, dry conditions, and evaluated under the specific incubation temperature and light regime described in Section 2. Consequently, the protocol is most directly applicable to seed-testing laboratories and restoration programs dealing with recently harvested, short-term stored orthodox seeds of C. leptophloeos from similar environments. Adjustments to TZT concentration or exposure time may be required for seeds subjected to prolonged storage, extreme drying, or originating from markedly different provenances. Despite these limitations, the protocol substantially improves the capacity to diagnose seed quality in this poorly studied species and provides a practical baseline for future refinements and comparative studies.

Through the application of the TZT, it was possible to clearly distinguish between viable and non-viable seeds. Seeds classified as viable exhibited a uniform crimson-red coloration in the internal tissues, indicating the presence of metabolically active cells (Figure 2). In addition, these seeds showed turgid cotyledons and embryonic axes, reflecting good physiological conditions and germination potential. This characteristic coloration results from the activity of dehydrogenase enzymes, which reduce the tetrazolium salt to the red compound triphenyl formazan, thereby visually marking viable tissues [40].

Seeds classified as non-viable exhibited characteristics that were easily identifiable in the tetrazolium test (Figure 3). The absence of staining or the presence of whitish tissues indicated a lack of respiratory activity, evidencing cell death and, consequently, physiological inviability. In other cases, a very intense or “burst-like” red coloration was observed, indicating tissue degeneration or advanced deterioration, which prevents the continuation of the germination process [7].

The clear distinction between seed classes was crucial for assessing viability quickly and efficiently, particularly given the germination difficulties observed in this species. Thus, the tetrazolium test proved to be a valuable tool for analyzing the physiological quality of these seeds, enabling the identification of seed lots with higher establishment potential for use in conservation and restoration programs in the Caatinga.

4. Conclusions

The data indicate that the tetrazolium test (TZT) is effective for assessing the viability of C. leptophloeos seeds, provided that appropriate solution concentrations and immersion times are used. The best conditions were obtained with TZT concentrations of 0.5% and 0.75%, particularly with exposure times of 2–4 h, yielding rapid and reliable results that were superior to those obtained with the conventional germination test.

Author Contributions

J.C.d.S.: investigation and writing—review and editing; J.d.J.S.: writing, review, and editing; R.A.G.: review and editing; C.R.P.C.: conceptualization, visualization, and supervision; B.F.D.: conceptualization, visualization, investigation, writing, review, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the Brazilian Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES; Finance Code 001), by FINEP under Grant Agreement No. 01.22.0614.00, and by the State University of Feira de Santana (UEFS).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article were submitted to REDAPE data repository and after approval will be available at Dantas, Barbara França; da Silva, Jamille Cardeal; Silva, Jailton de Jesus; Gomes, Raquel Araujo, 2025, “Tetrazolium test in seeds native to the brazilian Caatinga.”, https://doi.org/10.48432/WVOSO9, Redape (submission version).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES), the Foundation for the Support of Science and Technology of the State of Pernambuco (FACEPE), the Funding Authority for Studies and Projects (FINEP), and the State University of Feira de Santana (UEFS) for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Araujo, J.R.S.; de Felício, R.; Marinho da Silva, C.; de Oliveira, P.L.; de Araújo, S.S.; Sommaggio, L.R.D.; da Silva, A.F.C.; Nunes, P.H.V.; de Veras, B.O.; de Oliveira, E.B.; et al. Commiphora leptophloeos Bark Decoction: Phytochemical Composition, Antioxidant Capacity, and Non-Genotoxic Safety Profile. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareyn, F.G.C.; de Araújo, E.L.; Drumond, M.A. Commiphora leptophloeos: Umburana-de-cambão. In Espécies Nativas da Flora Brasileira de Valor Econômico Atual ou Potencial: Plantas para o Futuro: Região Nordeste; Coradin, L., Camillo, J., Pareyn, F.G.C., Eds.; Ministério do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2018; Chapter 5; pp. 746–751. Available online: http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/handle/doc/1103454 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Carvalho, P.E.R. Imburana-de-Espinho—Commiphora leptophloeos; Embrapa Florestas: Colombo, Brazil, 2009; Comunicado Técnico 228; Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/bitstream/doc/578660/1/CT228.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- da Costa Macedo, C.R.; de Aquino, I.S.; de Farias Borges, P.; da Silva Barbosa, A.; de Medeiros, G.R. Nesting Behavior of Stingless Bees. Ciênc. Anim. Bras. 2020, 21, e58736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, C.C.; Baskin, J.M. Seeds: Ecology, Biogeography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Salgotra, R.K.; Chauhan, B.S. Genetic Diversity, Conservation, and Utilization of Plant Genetic Resources. Genes 2023, 14, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França-Neto, J.B.; Krzyzanowski, F.C. Tetrazolium: An Important Test for Physiological Seed Quality Evaluation. J. Seed Sci. 2019, 41, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França-Neto, J.B.; Krzyzanowski, F.C. Metodologia do Teste de Tetrazólio em Sementes de Soja; Embrapa Soja: Londrina, Brazil, 2022; Documentos 449; 111p, Available online: http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/1148061 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Brasil, Ministério da Agricultura; Pecuária e Abastecimento; Secretaria de Defesa Agropecuária. Regras Para Análise de Sementes; MAPA/ACS: Brasília, Brazil, 2025. Available online: https://wikisda.agricultura.gov.br/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, H. Robust Tests for Equality of Variances. In Contributions to Probability and Statistics: Essays in Honor of Harold Hotelling; Olkin, I., Ghurye, S.G., Hoeffding, W., Madow, W.G., Mann, H.B., Eds.; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1960; pp. 278–292. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. An Introduction to Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007; Available online: https://mregresion.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/agresti-introduction-to-categorical-data.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.john-fox.ca/Companion/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Gross, J.; Ligges, U. nortest: Tests for Normality. R Package Version 1.0-4. 2015. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nortest (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Canty, A.; Ripley, B. boot: Bootstrap R (S-Plus) Functions. R Package Version 1.3-28.1. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=boot (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Lenth, R.V. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R Package Version 1.10.0. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Hothorn, T.; Bretz, F.; Westfall, P. Simultaneous Inference in General Parametric Models. Biom. J. 2008, 50, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, S.; Piepho, H.P.; Dorai-Raj, S. multcompView: Visualizations of Paired Comparisons. R Package Version 0.1-9. 2023. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=multcompView (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- DUNNETT, C.W. A multiple comparison procedure for comparing several treatments with a control. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1955, 50, 1096–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Hong, T.D.; Ellis, R.H. A Protocol to Determine Seed Storage Behaviour of Plant Species; IPGRI Technical Bulletin No. 1; IPGRI: Rome, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Probert, R.J. Seed Viability under Ambient Conditions, and the Importance of Drying. In Seed Conservation: Turning Science into Practice; Smith, R.D., Dickie, J.B., Linington, S.H., Pritchard, H.W., Probert, R.J., Eds.; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: London, UK, 2003; pp. 337–365. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, J.J.; Gomes, R.A.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Pelacani, C.R.; Dantas, B.F. Physiological Potential of Seeds of Handroanthus spongiosus (Rizzini) S. Grose (Bignoniaceae) Determined by the Tetrazolium Test. Seeds 2023, 2, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, G.C.M.; de Freitas David, T.; dos Santos Lopes, D.; de Assis, S.D.; do Patrocinio, W.C.T.; de Paula, A.M.D.; Brandão, F.J.B.; Dias, F.M. Qualidade Fisiológica de Sementes de Soja Submetidas a Diferentes Substratos e Temperaturas. Contrib. Cienc. Soc. 2025, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.C.L.; Gomes, I.H.R.A. Viabilidade de Sementes de Erythrina velutina Willd pelo Teste de Tetrazólio. Nativa 2015, 3, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, K.T.O.; Paiva, E.P.; Souza, M.L.; Neta, B.C.P.; Torres, S.B. Physiological Quality Evaluation of Piptadenia stipulacea (Benth.) Ducke Seeds by Tetrazolium Test. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2020, 51, e20196712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paiva, E.P.; Torres, S.B.; de Almeida, J.P.N.; da Sá, F.V.S.; de Oliveira, R.R.T. Tetrazolium Test for the Viability of Gherkin Seeds. Rev. Ciênc. Agron. 2017, 48, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.C.D.; Grzybowski, C.R.D.S.; França-Neto, J.D.B.; Panobianco, M. Adaptação do Teste de Tetrazólio para Avaliação da Viabilidade e do Vigor de Sementes de Girassol. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2013, 48, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.L.; Cunha, M.C.L. Viabilidade de Sementes de Senegalia polyphylla (DC.) Britton & Rose pelo Teste do Tetrazólio. Ciênc. Agríc. 2019, 17, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.L.; Forte, M.J.; Jacomino, A.P.; Forti, V.A.; da Silva, S.R. Biometric Characterization and Tetrazolium Test in Campomanesia phaea O. Berg Landrum Seeds. J. Seed Sci. 2021, 43, e202143013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, V.N.; Elias, S.G.; Gadotti, G.I.; Garay, A.E.; Villela, F.A. Can the Tetrazolium Test Be Used as an Alternative to the Germination Test in Determining Seed Viability of Grass Species? Crop Sci. 2016, 56, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, B.J.S.; de Oliveira, L.M.; de Sá, A.C.S.; da Delfes, L.R.; de Souza, A.C.; Antonelo, F.A. What Is the Cause of Low Seed Germination of Zanthoxylum rhoifolium Lam.? Rev. Ceres 2022, 69, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOSA. Tetrazolium Testing Handbook; Contribution to the Handbook on Seed Testing; Association of Official Seed Analysts: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ISTA. Handbook on Tetrazolium Testing, 3rd ed.; International Seed Testing Association: Wallisellen, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kozaki, A.; Aoyanagi, T. Molecular Aspects of Seed Development Controlled by Gibberellins and Abscisic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, R.P. Handbook on Tetrazolium Testing; International Seed Testing Association: Zürich, Switzerland, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bewley, J.D.; Bradford, K.J.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, C. Orthodoxy, Recalcitrance and In-Between: Describing Variation in Seed Storage Characteristics Using Threshold Responses to Water Loss. Seed Sci. Res. 2015, 25 (Suppl. S1), S1–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varsamis, G.; Merou, T.; Tseniklidou, K.; Goula, K.; Tsiftsis, S. How Different Reproduction Protocols Can Affect the Germination of Seeds: The Case of Three Stenoendemic Species on Mt. Olympus (NC Greece). Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2023, 13, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França-Neto, J.B.; Krzyzanowski, F.C. Metodologia do Teste de Tetrazólio; Embrapa Soja: Londrina, Brazil, 2018; Documentos 406; 108p, Available online: https://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/bitstream/doc/1098452/1/Doc406OL.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).