1. Introduction

The papaya crop (

Carica papaya L.) holds significant commercial value [

1]. Its fruits are rich in nutrients and possess notable medicinal properties. In addition to being classified as a super food, both the pulp and latex have various industrial applications. Mexico ranks third globally in papaya production and is the world’s leading exporter [

2]. However, the crop faces serious threats from the pest

Tetranychus urticae Koch, which causes damage by rupturing plant cells and extracting their contents. This results in chlorotic and tan spots on the leaves, which adversely affect photosynthesis and increase fruit exposure to sunlight, factors that negatively impact both yield and marketability [

3]. Farmers traditionally rely on synthetic pesticides for pest control, which have proven effective against

T. urticae. However, prolonged use of these chemicals (abamectins, pyrethroids, organophosphates, and METI inhibitors) has driven the development of resistance in several

Tetranychus urticae populations. In the case of abamectin, reduced sensitivity and elevated LC

50 values have been frequently reported following repeated applications in commercial crops. Moreover, the intensive use of synthetic pesticides contributes to environmental contamination and may pose risks to human health [

4].

In recent years, botanical acaricides have emerged as a promising alternative due to their lower environmental impact and reduced risk to human health. Among these, plant-derived oils have gained attention for their strong insecticidal and acaricidal properties with minimal side effects [

5]. These oils typically contain between 20 and 60 volatile compounds, produced through the secondary metabolism of the source plants, and play a role in the plants’ defense mechanisms against herbivores and pathogens [

6].

Although botanical derivatives are a viable option for pest management, they generally act more slowly than synthetic pesticides. Nonetheless, their lower ecological footprint makes them a valuable alternative [

7]. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of botanical oils: corn and soybean oils reduced mite populations by 25.61% and 22.4%, respectively [

8]; lavender oil reduced infestation by 45% [

9]; and oregano oil achieved up to 80% mite mortality [

10].

Gas exchange was evaluated because both mite feeding and the application of botanical formulations can alter key physiological processes such as photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, and transpiration. Herbivore damage is known to reduce carbon assimilation and modify leaf gas exchange, thereby affecting host plant quality and pest performance [

11,

12]. Feeding by

Tetranychus urticae has been shown to disrupt photosynthetic performance and carbon balance in its host plants [

12]. On the other hand, several essential-oil constituents, including monoterpenes such as 1,8-cineole, can depress photosynthesis and induce physiological stress in exposed tissues [

13]. Together, these findings support the use of gas exchange measurements as sensitive indicators of whether botanical oils not only suppress

T. urticae but also preserve (or compromise) the physiological integrity of papaya seedlings.

In papaya seedlings, research on botanical oils remains limited, as most available studies have focused on detached leaves or adult plants. Few reports simultaneously evaluate pest suppression, impacts on predatory mites, and plant physiological responses under nursery conditions, leaving a gap in understanding how these formulations perform during early crop development. Thus, this study addresses three key questions: (i) What is the effect of botanical oils on Tetranychus urticae under laboratory and field conditions? (ii) How do these formulations affect the predatory mite Amblyseius swirskii? (iii) What are the consequences of their application for gas exchange in papaya seedlings? Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effects of botanical oils on gas exchange in papaya seedlings and on the mortality of T. urticae and A. swirskii.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location and Plant Material

The study was conducted in the greenhouses of the experimental area of the Plant Physiology and Biotechnology Laboratory at the Tecnológico Nacional de México, Campus Conkal, located at Avenida Tecnológico S/N, 97345, Conkal, Yucatan, Mexico. Seeds of papaya (Carica papaya L.), cultivar Maradol (Mariola, Veracruz, Mexico), were used. Seeds were sown in polystyrene trays filled with peat moss substrate, with 100 seeds germinated per treatment. Three weeks after sowing, seedlings were transplanted to 6 kg grow bags filled with a 3:1 (v/v) soil/peat-moss mixture. Plants were irrigated daily to maintain soil moisture (at field capacity). Fertilization was carried out using a balanced N-P-K (19:19:19) formulation (Poly-Feed, Haifa, Mexico City, Mexico). Greenhouse conditions ranged between 25–35 °C and 55–75% relative humidity.

2.2. Seedling Infestation with T. urticae

Adults of T. urticae were obtained from a permanent colony maintained at the Instituto Tecnológico de Conkal, where eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) serves as the host plant. The abaxial side of infested eggplant leaves was placed onto the adaxial surface of healthy, mite-free papaya leaves. For each four-week-old seedling, three infested eggplant leaves were applied to ensure infestation.

2.3. Botanical Oil Treatments and Chemical Characterization of Botanical Formulations

To assess the effects of botanical oils, six treatments were established: a negative control with no application (T1), a positive synthetic-acaricide control (T2 = abamectin), and four biorational treatments (T3 = corn oil, T4 = soybean oil, T5 = lavender oil, and T6 = oregano oil). For each treatment, 10 mL of “Tween 20” (1%) was used as an emulsifier. The treatment solutions were prepared as follows: T3 = 10 mL of 95% corn oil, T4 = 7.5 mL of 90% soybean oil, T5 = 5 mL of 60% lavender essential oil, and T6 = 5 mL of 50% oregano essential oil. Each solution was brought to a final volume of 1 L with distilled water. The synthetic pesticide (T2) was prepared using 18 mg L−1 of abamectin (1.8% a.i.; Abakrone®, Biokrone, Celaya, Mexico). The botanical oils used as biorational treatments were corn oil (Cimax®, Ultraquimia Agrícola, Jiutepec, Mexico), soybean oil (EPA-90®, Biokrone, Mexico), lavender essential oil (Productos del Roble®, Mexico City, Mexico), and oregano essential oil (Productos del Roble®, Mexico). Each treatment was applied with a dedicated 15 L backpack sprayer equipped with a calibrated mist-type nozzle to ensure uniform foliar coverage and to avoid cross-contamination among treatments.

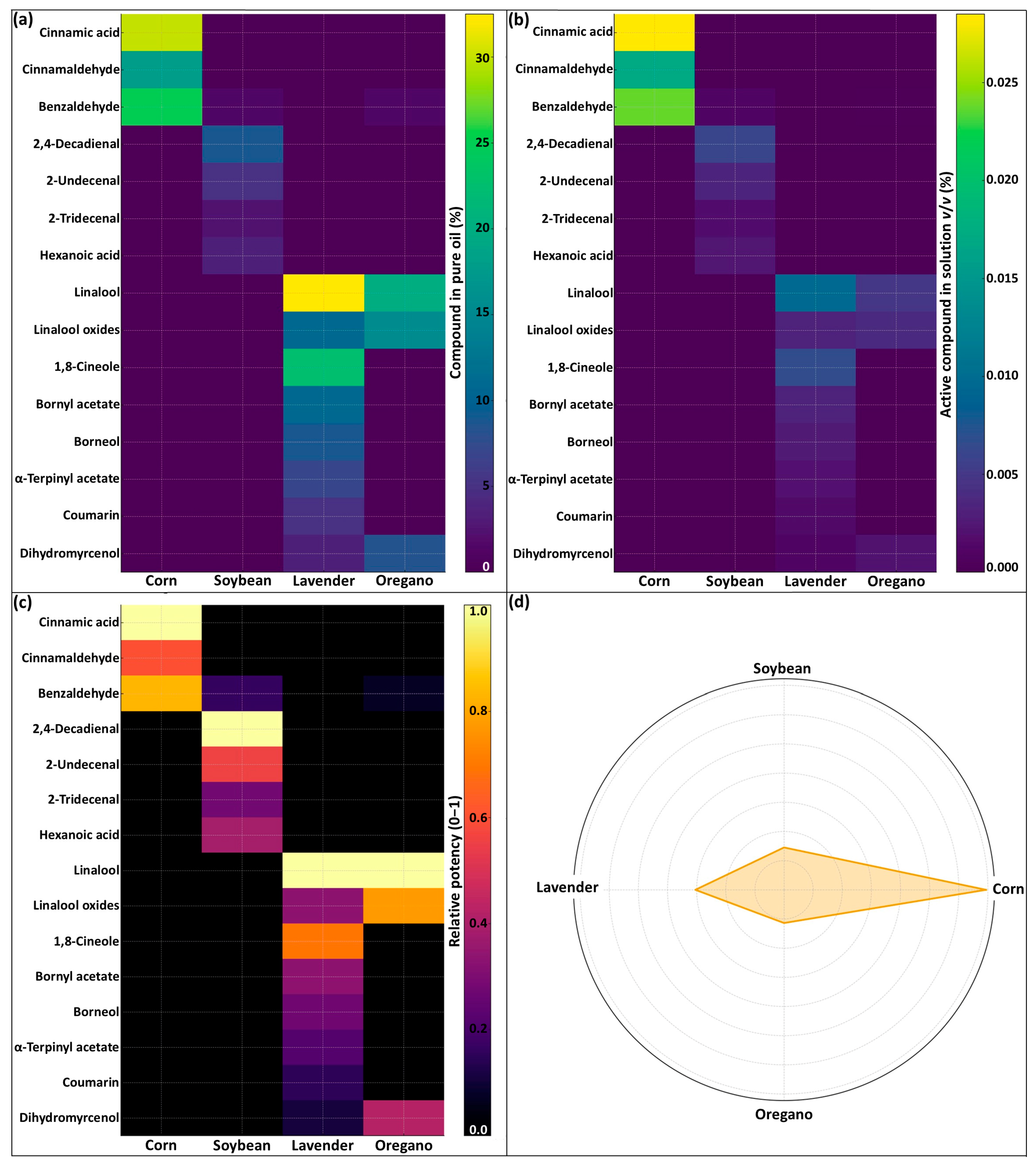

The four botanical formulations were chemically characterized to determine the volatile and semi-volatile constituents present in the pure oils and their relative contribution at the application dose used in the bioassays. For each oil (corn, soybean, lavender, and oregano), three replicate aliquots of the pure formulation were diluted 1:10 (v/v) in HPLC-grade hexane and analyzed using a gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) system equipped with a non-polar fused-silica capillary column. Helium was used as carrier gas, and compounds were separated under a temperature-programmed oven ramp optimized for the resolution of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and fatty acid-derived constituents. Mass spectra were acquired in electron-impact mode (70 eV) over an appropriate m/z range.

Chromatographic peaks were integrated, and tentative compound identifications were assigned by matching mass spectra and retention indices with commercial libraries (NIST) and published reference data. Only compounds detected in at least two of the three replicate injections and exceeding a minimum relative peak-area threshold were retained. Relative abundance (%) was calculated by normalizing each peak area to the total chromatographic area.

A subset of compounds with documented acaricidal or insecticidal activity was selected from the literature and used to construct the first heat map (chemical profiles of the pure oils). To estimate their contribution to the spray concentration used in the experiments, the relative abundance (%) of each compound was multiplied by the volume of oil applied per L of spray solution, generating formulation-level chemical loads. These loads were normalized to the maximum value per compound and visualized in the second heat map.

The chemical potency fingerprint and radar plot were generated to integrate the contribution of all biologically active constituents into a single comparative metric. For the fingerprint, each compound was first standardized by range normalization, assigning a score of 1.0 to the formulation with the highest concentration of that compound at the application dose (mg L−1), and scaling all other oils by simple division (value of oil X/maximum value across oils). This procedure yields dimensionless values between 0 and 1 and allows for cross-comparison among constituents with different chemical classes and absolute abundances. The radar plot was constructed by summing the standardized scores of all selected constituents for each oil, resulting in a global chemical load index that reflects the relative abundance of acaricidal, or insecticidal compounds delivered per L of spray solution. The index represents the cumulative normalized concentration (mg L−1) of active constituents, expressed as a unitless score and normalized to the largest polygon (set to 7 for corn oil). These indices enable direct comparison of the overall chemical potency of each formulation while avoiding biases associated with differences in volatility, structural class, or mass spectral response factors.

2.4. Laboratory Evaluation of T. urticae and A. swirskii Mortality

To evaluate in vitro toxicity against

T. urticae, the method described by [

14] was used. Leaf disks (5 cm diameter) were cut from papaya leaves and dipped for five seconds into each treatment solution, then air-dried for one hour. Disks were placed (adaxial side up) on moistened cotton inside 9 cm Petri dishes. Twenty adult

T. urticae were introduced per dish and incubated at 24 ± 3 °C with a 14:10 h light/dark photoperiod. Mite mortality was assessed at 24, 48, and 72 h after treatment.

For

Amblyseius swirskii, adults from the commercial product Swirski-Mite-Plus (Koppert, Querétaro, Mexico) were used. Toxicity was evaluated using the vial method described by [

15]. Each 20 mL glass vial was coated with 5 mL of the respective treatment, then emptied and dried for 3 h. Twenty

A. swirskii adults were placed in each vial, which was sealed with filter paper. Mortality was recorded at 24, 48, and 72 h. One vial constituted a replicate, and ten replicates per treatment were evaluated [

14].

2.5. Field Evaluation of T. urticae Mortality

Treatments were applied when seedlings showed full infestation by

T. urticae, two weeks after transplanting (six weeks post-sowing). Spraying was performed until runoff using a handheld sprayer. Population suppression was evaluated immediately after application and at 2, 3, 4, 7, 14, and 21 days post-treatment. One leaf per plant was collected and taken to the laboratory for mite counts (adults, nymphs, and eggs) using a stereomicroscope at 40× magnification. Leaf area was measured using a leaf area integrator (LI-COR, model LI-300C, Lincoln, NE, USA). Each plant represented one replicate, with ten replicates per treatment [

14].

2.6. Gas Exchange Parameters

Gas exchange was measured using an infrared gas analyzer (IRGA; LI-COR LI-6400, Lincoln, NE, USA). The CO

2 concentration was set at 400 μmol mol

−1, and photosynthetically active radiation was maintained at 2000 μmol m

−2 s

−1. The following parameters were recorded: net photosynthetic rate (

AN: μmol CO

2 m

−2 s

−1), transpiration rate (

E: mmol m

−2 s

−1), stomatal conductance (

gs: mol CO

2 m

−2 s

−1), intercellular CO

2 concentration (

Ci: μmol mol

−1), and water use efficiency (WUE: μmol CO

2/mmol H

2O). Measurements were taken at 8:00 a.m. For each treatment, five readings were taken per leaf, with one leaf per plant and five plants per block [

16]. Leaves were randomly selected from the upper canopy, fully expanded and sun-exposed.

2.7. Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with four replicates and 20 plants per treatment per block. Data were tested for normality, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. Where statistically significant differences were observed, Tukey’s HSD test was used for mean separation (α ≤ 0.05). Statistical analyses were performed using Statistica 7, and graphs were generated with SigmaPlot 11.

4. Discussion

The chemical characterization of the botanical formulations revealed two well-defined chemotypes that help clarify the contrasting biological responses observed in this study. In contrast to the profiles assumed a priori, the GC–MS data indicated that lavender was dominated by linalool, linalool oxides, 1,8-cineole, and bornyl/α-terpinyl acetates, whereas oregano contained dihydromyrcenol, coumarin, and additional acetate esters. These compounds are widely recognized for their neurotoxic or membrane-disrupting effects in arthropods [

3]. Corn oil, rather than being rich in fatty acids, was characterized by cinnamic acid, cinnamaldehyde, benzaldehyde, and 2,4-decadienal, while soybean oil exhibited uniformly weak signals across all compounds, consistent with its limited volatile profile. After adjusting these constituents to the application dose, corn oil delivered the highest chemical load per liter, lavender and oregano contributed intermediate loads, and soybean oil consistently showed the lowest chemical load per liter.

These chemical signatures were further resolved through the multivariate indicators developed for this study. The chemical potency fingerprint positioned lavender and oregano along the linalool–cineole and dihydromyrcenol–coumarin axes, respectively, while corn oil emerged as the formulation with the highest intensity for cinnamic acid-cinnamaldehyde derivatives, and soybean oil exhibited substantially lower standardized intensities across all constituents. The radar plot expanded this comparison, placing corn oil with the largest polygon, lavender and oregano at intermediate levels, and soybean oil with the smallest area. This pattern reconciles the biological responses: soybean oil produced high mortality in

T. urticae despite its low chemical load, consistent with a predominantly physical smothering or movement-interference mechanism, as described for botanical oils [

6]. Its minimal toxicity to

Amblyseius swirskii is aligned with the reduced exposure of predatory mites to continuous oil films and their greater grooming ability [

17].

Overall, this chemical evidence differentiates chemically driven efficacy (lavender and oregano) from physically driven efficacy (soybean and, to a lesser extent, corn), strengthening the interpretation of the mortality patterns across developmental stages.

Among the evaluated treatments, lavender oil was the most effective in reducing the number of

T. urticae adults under laboratory conditions. Similar results were reported in a previous study, where lavender oil exhibited strong acaricidal activity, causing 95% adult mortality within 24 h of application [

18]. Likewise, other studies have shown that corn and soybean oils resulted in over 95% and 80% mortality, respectively, in

T. urticae adults at 48 h post-treatment [

19]. In the case of oregano oil, more than 96% adult mortality was reported within the first 12 h [

20]. These findings are consistent with those of the present study, in which high mortality levels were observed at 72 h. The slight delay in effectiveness observed here may be attributed to differences in the concentrations or formulations used.

The predatory mite

A. swirskii is considered a successful biological control agent due to its ability to control multiple pests, feed on pollen in the absence of prey, and adapt to a wide range of food sources [

21]. However, the use of pesticides such as abamectin for the management of pest mites can indirectly harm

A. swirskii populations. For instance, 72 h after abamectin application, the mortality of

A. swirskii exceeded 20% [

22]. Other studies have reported a reduction in female fecundity following exposure to abamectin [

23], and in some cases, 100% adult mortality was observed within 48 h of treatment [

20]. In contrast, the use of botanical oils (e.g., corn, cinnamon, neem, argemone) as biorational alternatives resulted in significantly lower adult mortality, not exceeding 60% [

20]. In this study, some oils exceeded previously reported mortality rates, but their toxic effect was strongly influenced by botanical origin and exposure time. Given that certain oils, such as peppermint, can be highly toxic to

A. swirskii [

24], whereas others are less harmful [

17], the indiscriminate use of essential oils may compromise biological control. Therefore, their application should be carefully timed and selective to minimize risks for predatory mites. In our study, soybean oil showed the lowest toxicity to

A. swirskii, which is consistent with its lower chemical load and with a primarily physical mode of action that generates less direct neurotoxic impact.

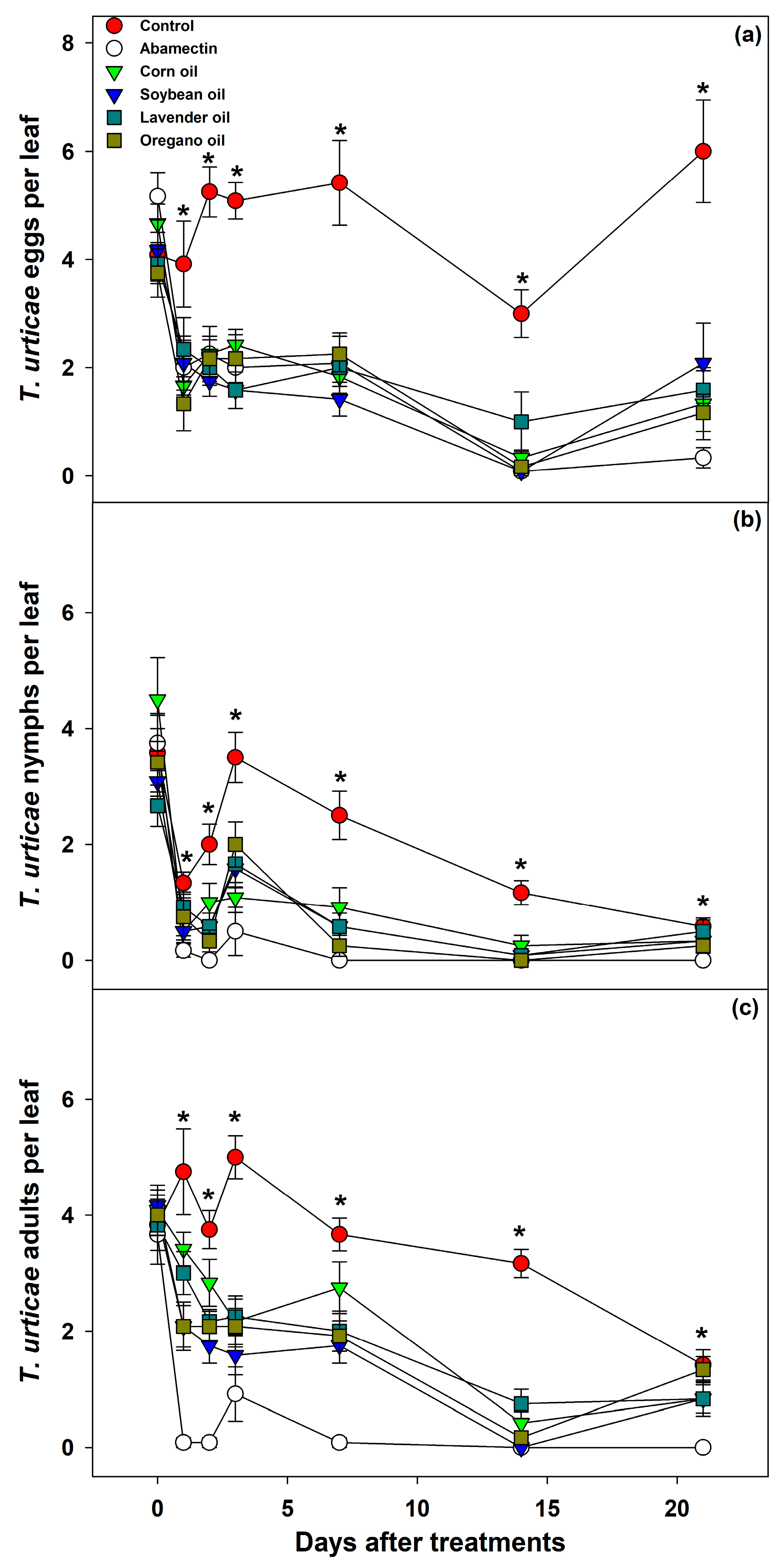

The treatment that significantly reduced the number of

T. urticae eggs was oregano oil. Given the GC–MS profile, this efficacy is likely associated with compounds such as dihydromyrcenol, coumarin, 1,8-cineole, and acetate esters, which have been associated with neurotoxic or membrane-active properties in other mite species [

25]. Its mode of action at the neurological level is comparable to that of abamectin, as both inhibit nerve transmission, ultimately causing paralysis and death across all life stages [

10]. Previous studies [

9,

26] have reported that treatments with soybean oil, corn oil, and lavender oil are more effective against adult mites than against eggs or nymphs. This difference in efficacy is attributed to their contact toxicity, which predominantly affects the nervous system of adult mites.

Nymph populations decreased significantly as early as the day following abamectin application, indicating an immediate acaricidal effect of the synthetic pesticide. This rapid efficacy is attributed to its action on the nervous system, which primarily targets nymphs and adults shortly after exposure [

27]. However, botanical oils also significantly reduced nymph numbers, although with a one-day delay compared to abamectin. The results of this study are consistent with previous findings, which reported that both oregano and lavender essential oils exhibit strong acaricidal activity against

T. urticae, particularly against nymphs and adults [

25]. While corn oil was less effective than oregano oil, it still showed greater efficacy against nymphs and adults than against eggs [

28]. However, the former had the greatest impact on beneficial fauna. Furthermore, oregano oil was more effective than the control in reducing both nymph and adult populations [

10]. By 23 days post-application, a decline in the effectiveness of both abamectin and the biorational treatments was observed, suggesting that a second application should be carried out before this time point to effectively disrupt the mite life cycle.

In adult mites, the effectiveness of the treatments declined over time, likely due to the volatilization of the oils. Lavender and oregano contain monoterpenoid structures that dissipate rapidly, while corn and soy oils contain aldehydes and low-volatility compounds that degrade more slowly, though still losing activity over time [

29,

30]. This supports the recommendation of reapplying botanical treatments every 14–21 days to intercept successive mite generations.

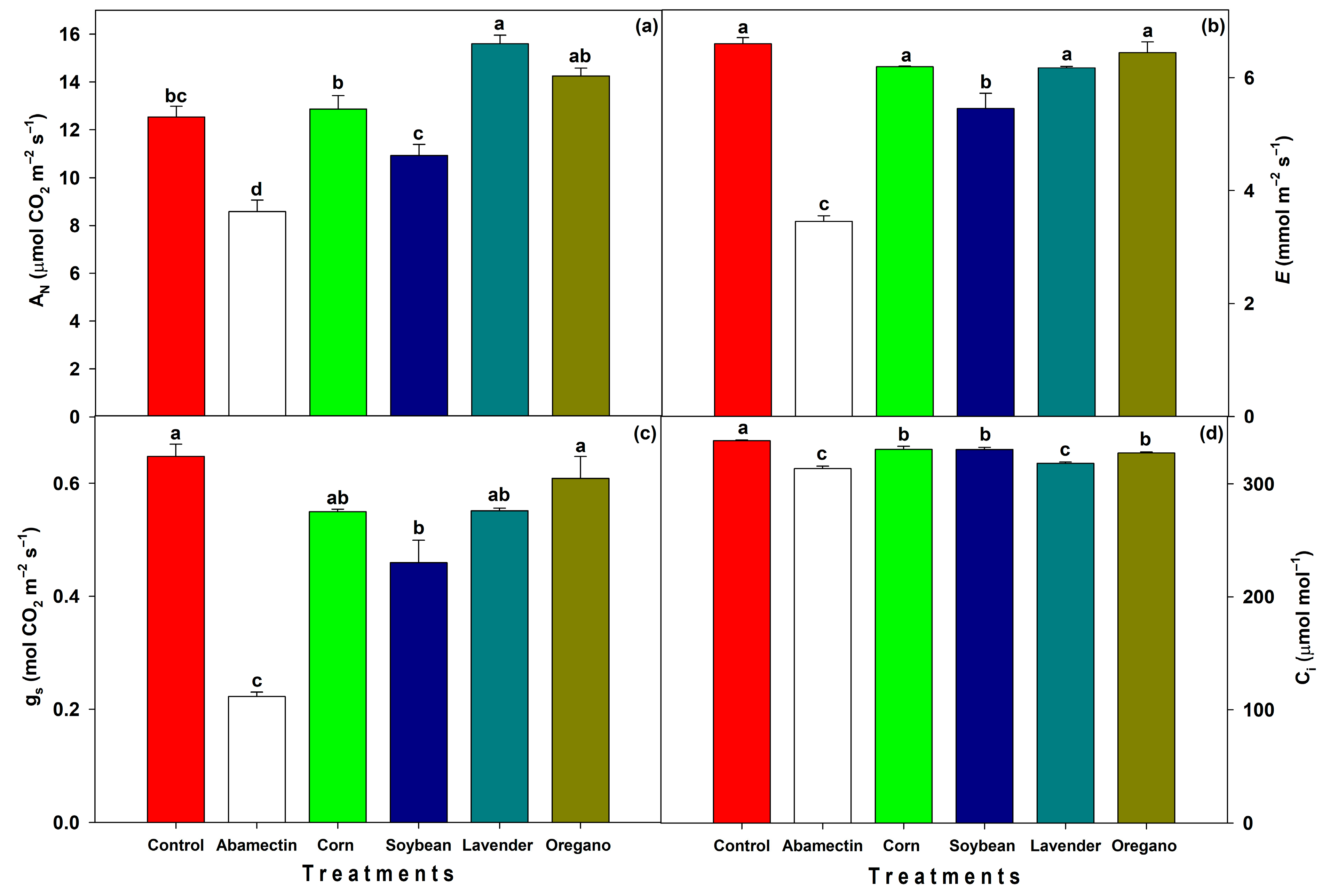

On the other hand, several years ago, it was reported that in

Mentha piperita [

31] and

Vitis vinifera [

32], carbon assimilation decreased in proportion to the damage caused by

Tetranychus urticae on the leaves. The same studies found no statistically significant effects on gas exchange parameters when a combination of acaricides was applied. However, the impact of acaricides on gas exchange can vary depending on the specific product and plant species. For example, no statistically significant differences in photosynthesis (

AN) or stomatal conductance (

gs) were observed following abamectin application in

Gerbera plants, while neem oil reduced

AN and

gs and caused visible flower damage, likely due to the phytotoxic effects of the oil [

33]. Moreover, abamectin has been reported to reduce photosynthesis by directly decreasing

gs, in contrast to other pesticides that act at the photosystem level to inhibit photosynthesis [

34].

Some pesticides, such as abamectin, have been shown to negatively affect photosynthesis. Although the net assimilation rate can be influenced by various factors,

gs is likely one of the primary contributors. In this context, guard cells respond to unfavorable conditions by closing the stomata [

35]. It has been observed that certain stress stimuli increase the concentration of free calcium ions (Ca

2+) in the cytosol of guard cells, triggering stomatal closure. When plants are exposed to pesticide-induced stress, hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2) levels rise, which in turn elevates cytosolic Ca

2+ concentrations, ultimately leading to stomatal closure [

36]. Soybean oil also reduced

gs and

E, a pattern compatible with partial occlusion of stomatal pores or transient film deposition, though without the strong photosynthetic depression caused by abamectin. The observed reduction in transpiration rate (

E) with both abamectin and soybean oil treatments is likely associated with a decline in

gs, particularly pronounced in the abamectin treatment.

In general, all treatments reduced intercellular CO

2 concentration (

Ci) compared to the control. However, the abamectin and lavender treatments exhibited the lowest

Ci values, suggesting a reduced presence of CO

2 molecules in the intercellular spaces available for carboxylation during the Calvin cycle. In the case of abamectin, this reduction in

Ci is likely attributed to a decrease in

gs, which may have limited the influx of atmospheric CO

2. In contrast, the low

Ci observed in the lavender treatment occurred despite relatively high

gs. This suggests that the reduction in

Ci was due to elevated carbon assimilation rates, with rapid carboxylation depleting the available CO

2 and preventing its accumulation in the mesophyll. It is important to note that, according to Fick’s law, intercellular CO

2 concentration plays a key role in understanding the relationship between

AN and

gs [

37].

Some of the reported disadvantages of using plant-derived oils for pest control include the volatility of monoterpenes and their potential phytotoxic effects, often associated with the allelopathic action of essential oil components [

38]. One of the main constituents of lavender essential oil is 1,8-cineole, a compound recognized for its strong insecticidal properties [

39], and which can constitute up to 46% of the oil in certain lavender varieties cultivated in Mexico [

40]. However, 1,8-cineole has also been associated with phytotoxic effects, particularly oxidative stress caused by the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS, including singlet oxygen (

1O

2), superoxide radicals (O

2−), hydroxyl radicals (OH

−), and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), are highly reactive molecules that can damage cellular components such as membranes, DNA, proteins, photosynthetic pigments, and lipids, thereby inhibiting plant growth [

41].

In the present study, it is likely that the concentration of lavender oil used (0.6%), containing approximately 0.27% 1,8-cineole, was sufficiently low to effectively control the pest without inducing phytotoxic effects in the plants. This likely avoided an increase in calcium ion concentration in guard cells or a rise in H

2O

2 levels in the leaf lamina, which could have otherwise led to stomatal closure. Consequently, high

AN was maintained in the lavender oil treatment. In contrast, other studies have reported reduced photosynthesis in

Cassia occidentalis and

Echinochloa crus-galli treated with eucalyptus oil at higher concentrations (from 2.5% to 7.5%) [

42].

Regarding water use efficiency (WUE), two distinct patterns were observed among the treatments with the highest values: abamectin and lavender oil. In the case of abamectin, the high WUE resulted from a marked reduction in gs, which limited both AN and E. This suggests that the stomatal closure led to a reduction in CO2 uptake and water loss, thereby increasing the WUE ratio despite an overall physiological constraint. In contrast, the high WUE observed in the lavender oil treatment was associated with elevated rates of AN, E, and gs. This indicates that lavender-treated plants achieved greater carbon assimilation per unit of water lost, suggesting improved physiological performance and gas exchange efficiency. Thus, the improved WUE in the lavender oil treatment was driven by enhanced carbon fixation rather than water conservation.

In practical terms, the joint evaluation of pest mortality and plant physiology showed two distinct profiles. Abamectin provided the fastest and strongest suppression of T. urticae, but this effect was accompanied by a marked reduction in AN, E, and gs, indicating a physiological cost to papaya seedlings. In contrast, the botanical oils, particularly lavender and oregano, achieved high levels of pest control while maintaining or even improving gas-exchange performance. This combination of moderate lethality reduced phytotoxicity, and compatibility with A. swirskii suggests that oils may offer a more balanced option for growers than abamectin, especially in production systems where plant vigor and biological control are critical.

5. Conclusions

Botanical formulations differed markedly in their chemical architecture and in the mechanisms through which they suppressed Tetranychus urticae. Essential oils such as lavender and oregano, characterized by linalool–cineole and dihydromyrcenol–coumarin profiles, exerted strong acaricidal activity across developmental stages while maintaining moderate compatibility with Amblyseius swirskii. Corn oil, although lacking monoterpenes, achieved high efficacy due to its cinnamic- and aldehyde-based chemical load, whereas soybean oil exhibited the lowest chemical input yet produced substantial adult mortality, consistent with a predominantly physical mode of action. The minimal impact of soybean oil on A. swirskii reinforces its suitability for integration with biological control programs.

Botanical oils applied to papaya seedlings were effective against all three developmental stages of Tetranychus urticae. In the egg stage, the response time of the biorational treatments was comparable to that of abamectin; however, for nymphs and adults, more time was required to achieve similar efficacy. The highest effectiveness of the botanical oils was observed 14 days after application, while by day 21, there was a noticeable resurgence of eggs, nymphs, and adults. This suggests that biorational applications should be made at intervals of no less than 14 days and no more than 21 days to maintain effective control.

In the in vitro mortality assay of T. urticae adults, treatments based on corn oil, soybean oil, and lavender essential oil proved to be as effective as abamectin within 24 h post-application. Among these, soybean oil was the least harmful to adults of the beneficial predatory mite Amblyseius swirskii. Additionally, while the synthetic pesticide negatively impacted gas exchange variables, biorational treatments had no adverse effects; in fact, lavender oil even enhanced photosynthetic capacity, contributing to improved plant physiological performance.

Therefore, all botanical oils evaluated in this study constitute promising alternatives to synthetic acaricides for the management of Tetranychus urticae. Among them, lavender essential oil demonstrated the most consistent performance due to its dual efficacy in suppressing mite populations while enhancing photosynthetic capacity. However, its application requires careful consideration of potential interference with the predatory mite Amblyseius swirskii. Further studies are thus warranted, particularly regarding the timing of application, to develop integrated pest management strategies that ensure effective control of Tetranychus spp. while maintaining compatibility with the conservation of beneficial natural enemies.