Abstract

Inguinal hernia repair (IHR) is a common surgical procedure among neonates and infants; the time of surgery is one of the major factors affecting its outcomes. Our systematic review aims to evaluate the effects of surgical timing on outcomes in inguinal hernia repairs in the newborn and infant population to establish evidence-based guidelines for optimal surgical timing. A systematic search was performed in PubMed, MEDLINE, and Web of Science databases, following PRISMA guidelines. Studies evaluating neonates and infants undergoing IHR with outcomes of recurrence, complications, and postoperative recovery were included. Data were collaboratively extracted, including patient demographics, surgical approaches, perioperative complications, and long-term outcomes. Early repair (0–28 days of life) decreased the risk of hernia incarceration but also increased the risk of preoperative complications. Delayed repair (29 days to 1 year of life) showed fewer preoperative complications but increased the risk of incarceration. The outcomes were affected by variables including patient maturity and comorbidities, along with hernia severity. Neonates with a high risk for incarceration are best treated with early repair, while stable infants can be managed safely with delayed repair. More randomized trials are needed to develop standardized guidelines that balance the associated risks of neonatal versus infant repair strategies to maximize benefits.

1. Introduction

Neonatal inguinal hernia is a common pathology in the neonate, occurring in approximately 1–5% of all live births, with high prevalence among preterm neonates (less than 37 weeks of gestational age) [1,2]. It is defined as the protrusion of a portion of the intestine through the inguinal canal due to incomplete closure of the vaginal process during embryological development [3]. The condition is typically treated during the neonatal period (the first 28 days of life or up to 44 weeks of gestational age) in premature neonates, or during the infant period (from 29 days up to 1 year of life) [4]. There is a risk of hernia incarceration with delayed surgical treatment (after 29 days) for a neonatal inguinal hernia, which could result in intestinal obstruction or strangulation and other long-term complications [5]. Clinical practice guidelines recommend immediate hernia repair surgery for all cases of neonatal inguinal hernia to prevent complications [6].

However, the timing of inguinal hernia repair is not specified due to the fact that the balance between lowering the risks associated with early repair (during the neonatal period) can significantly decrease the risk of incarceration, but it is still associated with an increased risk of postoperative respiratory complications and the need for prolonged hospital observation, especially in premature neonates. Previous research suggests delaying surgical repair (during the infant period) in preterm or hemodynamically unstable neonates to promote growth and stabilize the clinical condition, potentially reducing perioperative complications [7]. They have also identified several factors, including gestational age at birth, comorbidities, and timing of surgical intervention, that affect surgical outcomes regarding neonatal inguinal hernia repair [8]. However, the relative risks and benefits of surgical timing are more complex and are not necessarily age- or maturity-specific due to the ongoing physiologic development of neonates. As a result, the timing of hernia repair plays a significant role in surgical outcomes and overall success.

We conducted a systematic review with the objective to assess the effect of timing on the risk of complications and on outcomes after neonatal inguinal hernia repair and to compare early operative intervention against delayed operative intervention. However, while many studies have investigated outcomes after neonatal hernia repairs, there is still ongoing debate regarding optimal timing. Supporters of early repair point out that it lowers the risk of complications, while advocates for delayed repair argue that care of the neonate, allowing them to grow and become stable before surgery, is beneficial. This study aims to provide essential evidence-based insights that will guide the timing of surgery to maximize benefits while minimizing harm.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024610560) and was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Appendix A) [9]. We conducted a comprehensive electronic search using the following databases, PubMed, MEDLINE, and Web of Science, without any specific time frame. A search strategy was developed by the authors O.B. and A.A., and approved by the rest of the research team. Based on the timing of surgical intervention, we utilized two groups in this review: “early repair”, which we defined as a surgical intervention within the neonatal period, which is the first 28 days of life (or up to 44 weeks gestational age for premature neonates), and “Delayed repair”, which included surgical intervention within the infant period, which is 29 days to 1 year of life. Repairs occurring after age 1 year were excluded. Studies related to the impact of surgical timing on outcomes in neonatal inguinal hernia repairs were identified inclusively using a combination of Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) such as “Neonatal Inguinal Hernia” OR “Neonatal Hernia Repair” OR “Pediatric Hernia” OR “Inguinal Hernia Surgery” AND “Surgical Timing” OR “Neonatal Intervention” OR “Infant Intervention” OR “Surgical Outcomes” OR “Complications” AND “Incarceration” OR “Postoperative Complications”. To identify any missing articles, a further review of the references for the studies was conducted.

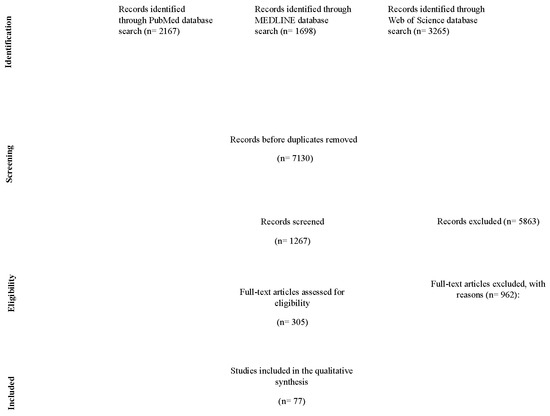

The search technique included searching several databases: PubMed (n = 2167), MEDLINE (n = 1698), and Web of Science (n = 3265). At first, the records were checked for duplicates, leaving 7130 distinct records. During the eligibility phase, 1267 records were reviewed, and 5863 records were eliminated based on the established criteria. Out of the records reviewed, 305 full-text articles were evaluated for eligibility, excluding 962 articles with indicated reasons. Seventy-seven papers met the criteria for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis.

2.2. Study Selection

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

This systematic review included studies that assessed the optimal timing of surgery and its effect on the outcome of neonatal inguinal hernia repairs. It included studies on early repairs (during neonatal period, which is 0–28 days of life, or up to 44 weeks gestational age for premature neonates) or delayed repairs (during infant period, which is 29 days to 1 year of life). This review included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, cohort studies, case–control studies, and observational studies published in English. Furthermore, this review included studies published in peer-reviewed journals or other credible sources.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review excluded studies that do not assess the optimal timing of surgery and its effect on the outcome of neonatal inguinal hernia repairs. It excluded studies that included children of 1 year old and older. We also disqualified studies investigating surgical management unrelated to inguinal hernia repairs, animal investigations, and in vitro assays. This review does not include studies published in non-English languages or those with insufficient data, such as bidding outcome measures, specific numerical results of scheduling variances, or relevant statistical analysis features essential for determining the impact of surgical timing.

2.2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

All records were securely stored and organized for systematic review purposes, with access restricted to the research team. Four authors (L.Y.A., A.A., O.A., and M.A.) then imported the remaining results into Rayyan [(https://www.rayyan.ai/), accessed 8 November 2024] for title and abstract screening based on relevance. Then, three authors (A.K., L.S.A., and H.I.W.) performed a full-text review of the papers that passed the first screening for inclusion or exclusion [10]. Discussions with O.B. and other researchers resolved any disagreements during the screening process. An Excel sheet was prepared by A.A., A.H.A., and O.B. to extract the following data from the selected studies, including title, author name, country, year of publication, journal name, study design, level of evidence, sample size, surgical complications, recurrence, and mortality rates.

2.2.4. Quality Assessment and Bias Evaluation

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) system was used to assess the risk of bias and quality of evidence from the included studies [11]. The level of evidence across all studies was ranked using this comprehensive assessment, providing an overall quality score that indicated a risk of bias. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to assess bias in retrospective and prospective cohort studies (Appendix B) [12]. We also evaluated the bias risk of RCTs using its updated Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) (Appendix D) [13]. The nonrandomized studies included in this review were also assessed using the MINORS tool (Appendix C) [14]. Such evaluations inform the reader about the quality of studies included and potential sources of bias, thereby increasing the trustworthiness of the results reported.

2.3. Data Synthesis

A meta-analysis could not be conducted because of major heterogeneity and the high inconsistency in data formats. This heterogeneity was further demonstrated by the diversity of study designs, such as RCTs, cohort studies, or observational studies, each using different forms of outcome assessments following surgery. The studies varied in terms of the demographics of the populations studied, such as the defined gestational age (term versus preterm neonates), birth weight, and comorbid conditions. These would impact surgical outcomes directly and would complicate inter-study comparisons. The surgical tactics for hernia repair (open vs. laparoscopic) and types of anesthesia (general vs. regional) were heterogeneous among the studies. Such differences influenced main features such as recurrence rates, complications, and recovery times, which have led to further inconsistencies. Outcomes, such as complication rates, recurrence rates, and postoperative outcomes, were inconsistently reported. Outcomes in some studies were assessed by the standardized scales, while others used descriptive metrics or did not quantify observations. These variations prevented us from synthesizing results into a single meta-analysis. Thus, we performed a basic descriptive statistical analysis with Review Manager version 5.4.1 (Cochrane, London, UK). This had the advantage of enabling us to report the results in an organized way while recognizing the concepts inherent in the data heterogeneity. Although heterogeneity across studies limited the applicability of some findings, it also highlighted the complexity in decision-making surrounding optimal surgical timing. Variability in the results underscores the importance of future studies employing standardized procedures and outcome measures. These modalities will also facilitate comparability across studies, resulting in a more solid evidential basis for clinical decision-making.

3. Results

A total of 7130 articles were identified during the initial database search. Then, we removed 5863 duplicates and applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, 962 articles were excluded for reasons of availability of full-text, duplication, methodological rigor, studies that involved other surgical procedures or did not include a study analysis on the topic of neonatal inguinal hernias. Finally, articles not written in English and articles that contained inadequate data to determine the timing of surgery and the effect on prognosis were also excluded. This leaves 305 articles that were further assessed for eligibility. A total of 77 articles met all criteria for inclusion in this systematic review regarding the impact of surgical timing on outcomes in neonatal inguinal hernia repairs and underwent further evaluation [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77].

The included papers contained a variety of study designs, including randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and observational studies. This heterogeneity enabled a more in-depth assessment regarding the impact of the timing of surgical intervention on neonatal outcomes following the repair of an inguinal hernia. Figure 1 outlines the PRISMA flowchart demonstrating the selection process. All studies were published between 1970 and 2024, and extracted studies came from various parts of the world.

Figure 1.

Detailed PRISMA chart used for this systematic review, outlining the many stages of this study’s selection process.

The articles referencing the effect of surgical timing on outcomes in neonatal inguinal hernia repairs, as well as characteristics of their cohort, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes of studies investigating impact of surgical timing on outcomes in neonatal inguinal hernia repairs.

3.1. Patients’ Profiles and Characteristics

The systematic review included a total of 96,674 patients undergoing inguinal hernia repairs. Out of these, 59,617 patients underwent early repairs, and 37,057 underwent delayed repairs. The ages of study participants varied considerably, ranging from neonates (<40 weeks gestational age to 28 days of life) to infants (29 days to 1 year of life), reflecting the diverse surgical timing practices and patient demographics.

The studies focusing on neonatal inguinal hernia repair not only point towards the devastating effect the condition holds but also surround the predominantly observed phenomenon, that is, males with significantly more representation than females. Based on a pooled analysis of studies, a male-to-female ratio of about 4:1 in neonatal and childhood populations was reported [44]. The results of our review were alongside a cohort study of 8037 infants assessing outcomes related to the timing of hernia repair, of which 3230 patients had early repair, thus demonstrating increased complications within the premature population, specifically recurrence and apnea [36]. Likewise, a comparative analysis of the timing of repair revealed that early repair significantly reduced the incarceration rates but also carried an increased risk of complications as well as increased length of stay, particularly in preterm infants [45]. These findings are consistent with the balance required between surgical urgency and the risks associated with early intervention in the preterm and neonatal populations. In addition, one study reported surgical techniques used, distinguishing between open and laparoscopic repairs. Patients undergoing laparoscopic repair had shorter hospitalizations and lower recurrence rates, especially in preterm neonates. However, it was also noted to require advanced expertise and facilities [28]. Another study compared the types of anesthesia, with general anesthesia being the most common approach [50]. Some studies have shown that the incidence of postoperative apnea was greater among preterm neonates, necessitating close monitoring during and after surgery [50,51]. There are limited studies reporting anesthesia’s long-lasting neurodevelopmental effects, underscoring the need for further research in this area [58]. Such numbers highlight the necessity to customize treatment and timing of intervention according to the patient to maximize the benefits in repair of the neonatal inguinal hernia.

3.2. Patient-Reported Outcomes and Complications

This section presents the key evidence related to patient outcomes and complications with neonatal and infant inguinal hernia repair, as shown in Table 2. An analysis was performed of six studies on preterm infants diagnosed with inguinal hernia during admission to the NICU. Early repair, performed pre-discharge was associated with significantly lower odds of hernia incarceration (OR 0.43, 95% CI 0.34–0.55, p < 0.001). However, it was also associated with increased postoperative pulmonary complications (OR 4.36, 95% CI 2.13–8.94, p < 0.001) and recurrence rates (OR 3.10, 95% CI 0.90–10.64, p = 0.07), while other complications of surgery (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.18–4.83, p = 0.94) were similar in both the neonatal and infant groups. The study evidences a nuanced balance between minimizing the chances of incarceration by repairing early vs. limiting airway complications with delayed repair, underscoring that care should be taken to avoid both outcomes, and reiterates the importance of patient-tailored decisions considering factors such as age, weight, and comorbidities [46].

Table 2.

Comparison of complications in neonatal vs. infant inguinal hernia repair.

4. Discussion

We conducted a systematic review to evaluate the effect of the timing of surgical intervention on outcomes for neonates with inguinal hernias. Early and delayed surgical options both have unique risks and benefits that impact the final outcome of the procedure, as highlighted by our analysis. The timing of surgery is the most critical determinant of the probability of complications such as incarceration, recurrence, and postoperative respiratory morbidity, particularly in the cases of premature and critically ill neonates.

In our review, we demonstrated that early hernia repair, particularly if performed prior to discharge, greatly reduces the rates of incarceration and intestinal strangulation [55,67]. This is extremely significant in preterm newborns, who are at an increased risk of difficulties as a result of immature physiological development. However, early repair was also associated with postoperative complications, including respiratory distress and apnea, which are particularly worrisome for preterm infants [50,68]. As a result, these neonates may need prolonged hospitalization and further observation to address these problems appropriately [69]. Conversely, delaying surgery until after the infant has had time to grow and clinically stabilize minimizes the risk of early postoperative complications, including respiratory complications [53]. However, delaying the inguinal hernia repair comes with a higher chance of incarceration, which can cause complications such as bowel obstruction or strangulation [55,70]. Making such decisions requires balancing the benefit of allowing the infant some time to mature and stabilize against the risk of facing complications during or after surgery [71,72]. Importantly, comorbid conditions such as chronic lung disease and anemia were significantly associated with the outcomes, with patients with these other conditions more likely to suffer postoperative apnea and prolonged recovery [51,73]. It emphasizes the necessity for a patient-focused approach to timing choices, as the overall health and stability of the neonate should be determined along with the portion of early and postponed surgery [74].

Surgeons operating on neonates and infants with inguinal hernias are faced with a choice of surgical technique, and this is one of the more important decisions, as selecting a technique that accomplishes adequate repair without undue complications has a significant impact on outcomes. Laparoscopic repair demonstrated advantages such as lower rates of recurrence and decreased lengths of hospital stay. However, its success depends on the surgeon’s skill and institutional support. Alternatively, open repair is a proven technique that is available in all centers but is known to have longer recovery times in some cases [22]. Regarding anesthesia, general anesthesia was mostly used, but awake caudal anesthesia was found to reduce the risk associated with general anesthesia, especially in preterm neonates [73]. While studies have reported a safe profile of general anesthesia for most neonates, the neurodevelopmental effects of early exposure to anesthesia at such an early age remain to be determined [58]. Randomized controlled trials are needed to better assess these risks and to help establish age- and technique-based guidelines on its use.

Our results highlight the need for individualized treatment strategies guided by patient-specific factors such as gestational age, comorbidities, and current clinical status. Although early repair confers the most optimal reduction in incarceration risk, delayed repair may be the safer alternative in specific population groups, especially those who are preterm born or possess large coexisting comorbidities [49,75]. Additionally, this review indicates that there is no single ideal approach, and the decision to undergo early versus delayed surgical intervention should be made by the treating team of healthcare professionals, including the pediatric surgeon and neonatologist, considering the overall prognosis of the patient. More studies, in particular multicenter randomized controlled trials, are needed to define the optimal timing strategies of repair and provide stronger evidence to direct the clinical practice of neonatal inguinal hernia repair.

Limitations

There are some limitations to this systematic review that need to be considered. Studies varied substantially concerning the surgical intervention used (open versus laparoscopic repair), anesthesia techniques, patient population characteristics, and methods of outcome assessment. Such heterogeneity could have affected the homogeneity of our results and precluded a meta-analysis, thus preventing a robust conclusion. Moreover, the majority of articles did not provide full perioperative care protocols, and, thus, specific operation-related aspects (recovery times, complications, etc.) could not be elucidated. Another major limitation is the inability to control for confounders that may influence surgical outcomes. Disparities in access to care, including subspecialty referral time, subspecialty pediatric surgeon availability, and hospital resources, may have affected the outcomes reported. Biased variability of recurrence rates and complications could also have been introduced due to the varying degrees of experience of the surgical team and the option for advanced laparoscopic techniques. These factors were not uniformly reported or adjusted for between studies, making it difficult to analyze the impact of surgical timing in isolation.

Moreover, the long-term effect of anesthesia on the neurodevelopment of neonates remains poorly characterized, which is an important consideration when weighing the risks of early versus delayed repair. The variation in follow-up reporting on these outcomes highlights the need for stronger, standardized reporting. To fill these gaps, further prospective, large-scale, multicenter trials with standardized parameters are needed in future studies. Standardized protocols regarding patient selection, surgical techniques, and postoperative care will improve comparability and yield better evidence for clinical practice guidelines. Additionally, studies should include socioeconomic and healthcare access-related factors to address uneven outcomes and promote equity in care across populations. Lastly, well-designed long-term follow-up studies are required to assess neurodevelopmental and quality-of-life outcomes between the various approaches to surgery timing.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review highlights that the timing of inguinal hernia repair in neonate and infant periods significantly influences the outcomes. Early repair (the first 28 days of life) reduces the risk of incarceration but increases the risks of postoperative complications, especially in preterm neonates. An individualized approach based on patient-specific factors such as age, comorbidities, and surgical resources is necessary for optimizing outcomes. We need additional randomized controlled trials to establish evidence-based guidelines for surgical timing.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: L.Y.A., A.A. (Arwa Alsharif), A.A. (Abdulaziz Alsharif), O.A. and M.A.; acquisition: A.K., L.A., H.I.W. and A.H.A.; analysis of data: O.B., L.Y.A., A.A. (Arwa Alsharif), A.A. (Abdulaziz Alsharif), O.A. and M.A.; drafting of the manuscript: A.K., L.A., H.I.W., O.B. and A.H.A.; critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: O.B., L.Y.A., A.A. (Arwa Alsharif), A.A. (Abdulaziz Alsharif), O.A., M.A., A.K., L.A., H.I.W. and A.H.A.; supervision: O.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024610560) and conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the nature of the research, which involved the analysis of previously published data and did not involve any direct human or animal subjects.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Systematic review protocol and support template.

Table A1.

Systematic review protocol and support template.

| Title of the Systematic Review | Impact of Surgical Timing on Outcomes in Neonatal Inguinal Hernia Repairs: A Systematic Review |

| |

| In neonates, inguinal hernia is the most prevalent condition, and it is particularly frequent in premature infants; it occurs when a portion of the intestine passes through the inguinal canal due to a failure in the abdominal wall closure process [3]. It was found in approximately 1–5% of all live births, with a greater prevalence among premature infants [4]. Postponed surgical treatment of neonatal inguinal hernia bears the risk of hernia incarceration, which in turn can lead to intestinal obstruction, strangulation, and long-term problems with high socioeconomic and humanistic burdens for family and public health [5]. The standard guideline recommends an open hernia repair surgery to treat neonatal inguinal hernia and to prevent complications [76,77]. Several factors that influence surgical outcomes after neonatal inguinal hernia repair were previously identified, including gestational age at birth, comorbidities, and timing of surgical repair [76]. However, due to the dynamic physiological development of neonates, the balance of surgical risks versus benefits often is complex and age- and maturity-dependent. As such, the timing of hernia repair can have a considerable impact on surgical outcomes and the overall success of hernia repair. However, available data do not have sufficient evidence to identify optimal timing to repair neonatal inguinal hernias. Many retrospective, nonrandomized studies have suggested that delaying surgery may result in an increased chance of complications such as incarceration. The timing of surgical procedures is often based on clinical experience and custom rather than solid empirical data. As such, additional well-founded studies are warranted for determining the impact of surgical timing on patient outcomes. This may enhance surgical methods and help inform future studies. | |

| |

| This systematic review aims to assess the effect of surgical timing on outcomes with neonatal inguinal hernia repair and determine the optimal timing of surgical intervention, and should thus evaluate if reported outcomes differ according to the timing of surgery. It also offers a comprehensive review and evidence-based recommendations on best practices regarding the surgical management of neonatal inguinal hernias that can improve outcomes, surgical complication rates, and postoperative morbidity. | |

| |

| |

| |

| Population, or participants and condition of interest | This review will include patients of different ages and genders diagnosed with an inguinal hernia in various healthcare settings. The condition of interest in this systematic review is the outcomes and safety of surgical timing in neonatal inguinal hernia repairs, evaluating the efficacy of neonatal versus infant surgical intervention in this patient population. |

| Interventions or exposures |

|

| Comparisons or control groups | Standard Care: This group consists of neonates receiving standard care for inguinal hernia management, which may include observation and watchful waiting for asymptomatic hernias or conservative treatment options before surgical intervention. This approach allows for the evaluation of outcomes in comparison to those undergoing surgical repair at various times. |

| Outcomes of interest | Rates of hernia recurrence, complication rates associated with different surgical timings, postoperative recovery times, and overall health outcomes in neonates following inguinal hernia repair. |

| Setting |

|

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

| |

| Electronic databases |

|

| Keywords | (Inguinal hernia OR Surgical timing OR Neonatal surgery OR Complications OR Outcomes OR Recurrence OR Pediatric surgery) |

| |

| Details of methods, number of reviewers, how agreements are be reached and disagreements dealt with, etc. | Three main reviewers and a fourth to resolve any disagreements. Resolving any outstanding disagreements, an article by Dr. Osama and Dr. Arwa. |

| Quality assessment tools or checklists used with references or URLs | Protocol will define the method of the literature critique/appraisal used, and will use the STROBE tool for relevant content and methodology used in the each of the papers to be reviewed. |

| Narrative synthesis details of what and how synthesis will be performed | Narrative synthesis will be performed alongside any meta-analysis and will be carried out using a framework which consists of four elements: 1- Developing a theory of how the intervention works, why, and for whom. 2- Developing a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies. 3- Exploring relationships within and between studies. 4- Assessing the robustness of the synthesis. |

| Meta-analysis details of what and how analysis and testing will be performed. If no meta-analysis is to be conducted, please give reason. | Although a meta-analysis is planned, this will only become apparent when we see what data are extracted and made available from the systematic review. We need to think about how heterogeneity will be explored. |

| Grading evidence system used, if any, such as GRADE | GRADE will be used for the evidence assessment. |

| |

| Additional material summary tables, flowcharts, etc. to be included in the final paper | Flowchart of whole process. Protocol data extraction from and rorest plots of studies included in the final review. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for the included cohort prospective and retrospective studies.

Table A2.

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale for the included cohort prospective and retrospective studies.

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Quality Score | Risk of Bias (0–3: High; 4–6: Moderate; 7–9: Low) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Article | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | ||

| Masoudian, 2018 [15] | (B) somewhat representative of the average cohort | (B) drawn from the same community | * | * | One factor controlled (gestational age) | * | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (6) | Moderate Risk |

| Khasawneh, 2020 [16] | (C) selected group of users | (C) no description of the derivation of the non exposed cohort | * | * | No comparability | * | Yes | * | Poor Quality Study (4) | Moderate Risk |

| Cho, 2023 [17] | (A) truly representative of the average cohort | (A) derived from the same population | ** | ** | One factor controlled (comorbidities) | * | Yes | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Kus, 2024 [18] | (C) selected group of users | (c) no description of the derivation of the non exposed cohort | * | * | No comparability | * | No | * | Poor Quality Study (4) | Moderate risk |

| Soyer, 2024 [19] | (A) truly representative of the average cohort | (B) drawn from the same community | * | * | No comparability | * | No | * | Moderate Quality Study (5) | Moderate risk |

| Cho, 2023 [20] | (B) somewhat representative of the average cohort | (B) drawn from the same community | * | * | One factor controlled (NICU status) | ** | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (6) | Moderate risk |

| Crankson, 2014 [21] | (C) selected group of users | (C) no description of the derivation of the non-exposed cohort | * | * | No comparability | * | No | * | Poor Quality Study (4) | Moderate Risk |

| Walsh, 2020 [22] | (A) truly representative of the average cohort | (A) derived from the same population | ** | ** | One factor controlled (age or comorbidities) | * | Yes | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Prato, 2014 [23] | (B) somewhat representative of the average cohort | (C) no description of the derivation of the non-exposed cohort | * | * | No comparability | * | No | * | Poor Quality Study (4) | Moderate Risk |

| Castro, 2019 [24] | (B) somewhat representative of the average cohort | (A) derived from the same population | ** | * | One factor controlled (weight or gestational age) | * | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (6) | Moderate Risk |

| Peace, 2022 [25] | (A) truly representative of the average cohort | (A) derived from the same population | ** | ** | One factor controlled (socioeconomic factors) | * | Yes | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Haveliwala, 2023 [26] | (A) truly representative of the average cohort | (B) drawn from the same community | ** | ** | Two factors controlled (socioeconomic status, type of hospital) | * | Yes | ** | Good Quality Study (8) | Low Risk |

| Verhelst, 2015 [27] | (B) somewhat representative of the average cohort | (B) drawn from the same community | * | * | One factor controlled (hospital type) | * | Yes | * | Moderate Quality Study (6) | Moderate Risk |

Selection: Q1. Representativeness of the exposure cohort? Q2. Selection of the non-exposure cohort? Q3. Ascertainment of exposure? Q4. Demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study? Comparability: Q5. Comparability of cohort based on the design or analysis? Outcome: Q6. Assessment of outcome? Q7. Was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur? Q8. Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts? *: Means the corresponding quality component or criterion is partially met; **: means the corresponding quality component or criterion is fully met.

Appendix C

Table A3.

Bias of the included cross-sectional studies evaluated according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

Table A3.

Bias of the included cross-sectional studies evaluated according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Quality Score | Risk of Bias (0–3: High; 4–6: Moderate; 7–9: Low) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | |||

| Olesen, 2020 [32] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Wolf, 2021 [37] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Demouron, 2018 [38] | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk |

| Sonderman, 2018 [39] | * | * | * | * | * | * | Good Quality Study (7) | Low Risk | |

Selection: Q1. Representativeness of the exposure cohort? Q2. Sample size? Q3. Ascertainment of exposure? Q4. Response rate? Q5. Ascertainment of the screening/surveillance tool? Comparability: Q5. The potential confounders were investigated by subgroup analysis or multivariable analysis? Outcome: Q6. Assessment of outcome? Q7. Statistical test? *: Means the corresponding quality component or criterion is partially met.

Appendix D

Table A4.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).

Table A4.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool for randomized trials (RoB 2).

| Articles | Bias Arising from the Randomization Process | Bias Due to Deviations from Intended Interventions | Blinding of Participants and Personnal | Bias Due to Missing Outcome Data | Bias in Measurement of the Outcome | Bias in Selection of the Reported Result | Overall RoB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blakely, 2024 [5] | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Choo, 2022 [6] | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Gulack, 2017 [36] | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk |

| Bawazir, 2019 [29] | Low Risk | Moderate Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Low Risk | Moderate Risk |

References

- Ramachandran, V.; Edwards, C.F.; Bichianu, D.C. Inguinal Hernia in Premature Infants. Neoreviews 2020, 21, e392–e403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wimper, Y.; Stortelder, E.; Botden, S.M.B.I.; De Blaauw, I. Inguinal Hernia in Children: Easily Incarcerated. Nederlandsch Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde/Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Geneeskunde/NTvG-databank. 2021; Volume 165. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/MED/33793128 (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Khan, F.A.; Zeidan, N.; Larson, S.D.; Taylor, J.A.; Islam, S. Inguinal hernias in premature neonates: Exploring optimal timing for repair. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 1157–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, E.; Pacilli, M.; Nataraja, R.M. Inguinal hernias in children. Aust. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 49, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blakely, M.L.; Krzyzaniak, A.; Dassinger, M.S.; Pedroza, C.; Weitkamp, J.H.; Gosain, A.; Cotten, M.; Hintz, S.R.; Rice, H.; Courtney, S.E.; et al. Effect of Early vs Late Inguinal Hernia Repair on Serious Adverse Event Rates in Preterm Infants. JAMA 2024, 331, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgado, M.; Holland, A.J. Inguinal hernias in children: Update on management guidelines. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2024, 60, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, F.; Dreuning, K.M.A.; Lok, M.J.H.J.; Wester, T.; Derikx, J.P.M.; Friedmacher, F.; Miyake, H.; Zhu, H.; Pio, L.; Lacher, M.; et al. Surgical Management of Pediatric Inguinal Hernia: A Systematic Review and Guideline from the European Pediatric Surgeons’ Association Evidence and Guideline Committee. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 32, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Jancelewicz, T.; Kieran, K.; Islam, S.; Eichenwald, E.; Guillory, C.; Hand, I.; Hudak, M.; Kaufman, D.; Martin, C.; et al. Assessment and Management of Inguinal Hernias in Children. Pediatrics 2023, 152, e2023062510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozek, J.L.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; Akl, E.A.; Bowen, J.M.; Bucher, J.; Chiu, W.A.; Cronin, M.; Djulbegovic, B.; Falavigna, M.; Guyatt, G.H.; et al. GRADE Guidelines 30: The GRADE approach to assessing the certainty of modeled evidence—An overview in the context of health decision-making. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2020, 129, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2010, 25, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gotzsche, P.C.; Juni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.a.C. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoudian, P.; Sullivan, K.J.; Mohamed, H.; Nasr, A. Optimal timing for inguinal hernia repair in premature infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 54, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasawneh, W.; Al-Ghzawi, F.; Yusef, D.; Altamimi, E.; Saqan, R. Inguinal hernia repair among Jordanian infants; A cohort study from a university based tertiary center. J. Neonatal-Perinat. Med. 2020, 14, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, C.S.; Ong, C.C.; Yong, T.T.; Yap, T.L.; Chiang, L.W.; Chen, Y. Inguinal Hernia in Premature Infants: To Operate Before or After Discharge from Hospital? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 59, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, N.; Dumitru, A.M.; Hwang, R.; Nace, G.; Allukian, M. Outpatient Factors Implicated in Timing of Delayed Elective Inguinal Hernia Repair in Premature Neonates: Single Center Analysis Brings Up a Touchy Issue and Balancing Metric. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 59, 161658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyer, T.; Pio, L.; Gorter, R.; Martinez, L.; Dingemann, J.; Pederiva, F.; Dariel, A.; Zani-Ruttenstock, E.; Kakar, M.; Hall, N.J. European Pediatric Surgeons’ Association Survey on Timing of Inguinal Hernia Repair in Premature Infants. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 34, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Kwon, H.; Ha, S.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, D.Y.; Namgoong, J.M.; Nam, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Jung, E.; Cho, M.J. Optimal timing for inguinal hernia repair in premature infants: Surgical issues for inguinal hernia in premature infants. Ann. Surg. Treat. Res. 2023, 104, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crankson, S.; Tawil, K.A.; Namshan, M.A.; Jadaan, S.A.; Baylon, B.; Gieballa, M.; Ahmed, I. Management of inguinal hernia in premature infants: 10-year experience. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.M.; Ng, J.; Saxena, A.K. Comparative Analysis of Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair in Neonates and Infants. Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutaneous Tech. 2020, 30, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prato, A.P.; Rossi, V.; Mosconi, M.; Disma, N.; Mameli, L.; Montobbio, G.; Michelazzi, A.; Faranda, F.; Avanzini, S.; Buffa, P.; et al. Inguinal hernia in neonates and ex-preterm: Complications, timing and need for routine contralateral exploration. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2014, 31, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, B.A.; Novillo, I.C.; Vázquez, A.G.; De Miguel Moya, M. Is the Laparoscopic Approach Safe for Inguinal Hernia Repair in Preterms? J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2019, 29, 1302–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peace, A.E.; Duchesneau, E.D.; Agala, C.B.; Phillips, M.R.; McLean, S.E.; Hayes, A.A.; Akinkuotu, A.C. Costs and recurrence of inguinal hernia repair in premature infants during neonatal admission. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 58, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haveliwala, Z.; Eaton, S.; Sivaraj, J.; Thakkar, H.; Omar, S.; Giuliani, S.; Blackburn, S.; Mullassery, D.; Curry, J.; Cross, K.; et al. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (LIHR): The benefit of the double stitch in the largest single-center experience. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2023, 40, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhelst, J.; De Goede, B.; Van Kempen, B.J.H.; Langeveld, H.R.; Poley, M.J.; Kazemier, G.; Jeekel, J.; Wijnen, R.M.H.; Lange, J.F. Emergency repair of inguinal hernia in the premature infant is associated with high direct medical costs. Hernia 2015, 20, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safa, N.; Le-Nguyen, A.; Gaffar, R.; Habti, M.; Bensakeur, I.; Li, O.; Piché, N.; Emil, S. Open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in children: A regional experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 58, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazir, O.A. Delaying surgery for inguinal hernia in neonates: Is it worthwhile? J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2019, 14, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, W.A.; Huerta, C.T.; O’Neil, C.F.; Taylor, R.R.; Saberi, R.A.; Gilna, G.P.; Collie, B.L.; Lyons, N.B.; Parreco, J.P.; Thorson, C.M.; et al. Timing of Pediatric Incarcerated Inguinal Hernia Repair: A Review of Nationwide Readmissions Data. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 295, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinkuotu, A.C.; Roberson, M.; Strassle, P.D.; Phillips, M.R.; McLean, S.E.; Hayes-Jordan, A. Factors associated with inguinal hernia repair in premature infants during neonatal admission. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2021, 57, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, C.S.; Andersen, K.; Öberg, S.; Deigaard, S.L.; Rosenberg, J. Timing of inguinal hernia repair in children varies greatly among hernia surgeons. Dan. Med. J. 2020, 68, A07200554. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/MED/33463510 (accessed on 22 October 2024). [PubMed]

- Fukuhara, M.; Onishi, S.; Handa, N.; Sato, T.; Esumi, G. Spontaneous reduction age for ovarian hernia in early infancy. Pediatr. Int. 2021, 64, e15024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, J.K.; Kim, H.Y.; Huh, Y.J.; Han, J.W.; Kim, S.H.; Oh, C.; Jo, A.H.; Park, K.W.; Jung, S.E. Inguinal hernia in preterms in neonatal intensive care units: Optimal timing of herniorrhaphy and necessity of contralateral exploration in unilateral presentation. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 2155–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.; Sonderman, K.A.; Wolf, L.L.; Jiang, W.; Armstrong, L.B.; Koehlmoos, T.P.; Weil, B.R.; Ricca, R.L.; Weldon, C.B.; Haider, A.H.; et al. Hernia recurrence following inguinal hernia repair in children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 2214–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulack, B.C.; Greenberg, R.; Clark, R.H.; Miranda, M.L.; Blakely, M.L.; Rice, H.E.; Adibe, O.O.; Tracy, E.T.; Smith, P.B. A multi-institution analysis of predictors of timing of inguinal hernia repair among premature infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 53, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, L.L.; Sonderman, K.A.; Kwon, N.K.; Armstrong, L.B.; Weil, B.R.; Koehlmoos, T.P.; Losina, E.; Ricca, R.L.; Weldon, C.B.; Haider, A.H.; et al. Epidemiology of abdominal wall and groin hernia repairs in children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2021, 37, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demouron, M.; Delforge, X.; Buisson, P.; Hamzy, M.; Klein, C.; Haraux, E. Is contralateral inguinal exploration necessary in preterm girls undergoing inguinal hernia repair during the first months of life? Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 1151–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonderman, K.A.; Wolf, L.L.; Armstrong, L.B.; Taylor, K.; Jiang, W.; Weil, B.R.; Koehlmoos, T.P.; Ricca, R.L.; Weldon, C.B.; Haider, A.H.; et al. Testicular atrophy following inguinal hernia repair in children. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2018, 34, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreuning, K.M.; Barendsen, R.W.; Van Trotsenburg, A.P.; Twisk, J.W.; Sleeboom, C.; Van Heurn, L.E.; Derikx, J.P. Inguinal hernia in girls: A retrospective analysis of over 1000 patients. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 55, 1908–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, R.; Alrazek, M.A.; Elsaied, A.; Helal, A.; Mahfouz, M.; Ismail, M.; Shams, A.; Magid, M. Fifteen Years Experience with Laparoscopic Inguinal Hernia Repair in Infants and Children. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2017, 28, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasau, H.; Kamanda, J.; Lebbie, A.; Cotache-Condor, C.; Espinoza, P.; Grimm, A.; Wright, N.; Smith, E. Prevalence and outcomes of pediatric surgical conditions at Connaught Hospital in Freetown: A retrospective study. World J. Pediatr. Surg. 2023, 6, e000473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhalabi, R.; Belsha, D.; Rabei, H.; Muad, H.; Farhoud, H.; Nakib, G.; Ba’Ath, M.E. Postoperative Necrotizing Enterocolitis Following Inguinal Hernia Repair in an Infant: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Cureus 2023, 15, e45089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosfeld, J.L. Current concepts in inguinal hernia in infants and children. World J. Surg. 1989, 13, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.L.; Gleason, J.M.; Sydorak, R.M. A critical review of premature infants with inguinal hernias: Optimal timing of repair, incarceration risk, and postoperative apnea. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choo, C.S.; Chen, Y.; McHoney, M. Delayed versus early repair of inguinal hernia in preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2022, 57, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; King, B. EBNEO Commentary: The impact of timing of inguinal hernia repair on outcomes in preterm infants. Acta Paediatr. 2024, 113, 2325–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrantella, A.; Sola, J.E.; Parreco, J.; Quiroz, H.J.; Willobee, B.A.; Reyes, C.; Thorson, C.M.; Perez, E.A. Complications while awaiting elective inguinal hernia repair in infants: Not as common as you thought. Surgery 2021, 169, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rescorla, F.J.; Grosfeld, J.L. Inguinal hernia repair in the perinatal period and early infancy: Clinical considerations. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1984, 19, 832–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, C.J.; Zaslavsky, A.; Downes, J.J.; Kurth, C.D.; Welborn, L.G.; Warner, L.O.; Malviya, S.V. Postoperative Apnea in Former Preterm Infants after Inguinal Herniorrhaphy. Anesthesiology 1995, 82, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welborn, L.G.; Hannallah, R.S.; Luban, N.L.C.; Fink, R.; Ruttimann, U.E. Anemia and Postoperative Apnea in Former Preterm Infants. Anesthesiology 1991, 74, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianos, S.; Jacir, N.N.; Harris, B.H. Incarceration of inguinal hernia in infants prior to elective repair. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1993, 28, 582–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, V.H.S.; Clive, J.; Rosenkrantz, T.S.; Bourque, M.D.; Hussain, N. Inguinal hernia in preterm infants (≤32-Week Gestation). Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2002, 18, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowitz, M.E.; Gao, W.; Sipsma, H.; Zuckerman, P.; Wong, H.; Ayyagari, R.; Sarda, S.P. Burden of Comorbidities and Healthcare Resource Utilization Among Medicaid-Enrolled Extremely Premature Infants. J. Health Econ. Outcomes Res. 2022, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautz, T.B.; Raval, M.V.; Reynolds, M. Does Timing Matter? A National Perspective on the Risk of Incarceration in Premature Neonates with Inguinal Hernia. J. Pediatr. 2010, 158, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, M.A.; Neal, D.; Pairawan, S.; Tagge, E.P.; Hashmi, A.; Islam, S.; Khan, F.A. Optimal Timing of Inguinal Hernia Repair in Premature Infants: A NSQIP-P Study. J. Surg. Res. 2022, 283, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, J.P.; Cooper, J.N.; Duggan, E.M.; Balci, O.; Anandalwar, S.P.; Blakely, M.L.; Heiss, K.; Rangel, S.; Minneci, P.C.; Deans, K.J. Does timing of neonatal inguinal hernia repair affect outcomes? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 50, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakely, M.L.; Tyson, J.E.; Lally, K.P.; Hintz, S.R.; Eggleston, B.; Stevenson, D.K.; Besner, G.E.; Das, A.; Ohls, R.K.; Truog, W.E.; et al. Initial Laparotomy Versus Peritoneal Drainage in Extremely Low Birthweight Infants With Surgical Necrotizing Enterocolitis or Isolated Intestinal Perforation. Ann. Surg. 2021, 274, e370–e380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inguinal hernias and hydroceles in infancy and childhood: A consensus statement of the Canadian Association of Paediatric Surgeons. Paediatr. Child Health 2000, 5, 461–462. [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rajput, A.; Gauderer, M.W.L.; Hack, M. Inguinal hernias in very low birth weight infants: Incidence and timing of repair. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1992, 27, 1322–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, R.C.; Garper, A.; Sia, C. Inguinal Hernia: A Common Problem of Premature Infants Weighing 1000 Grams or Less at Birth. Pediatrics 1975, 56, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M.I. Incarcerated and Strangulated Hernias in Children. Arch. Surg. 1970, 101, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, P.; Guiney, E.J.; O’Donnell, B. Inguinal hernia in infants: The fate of the testis following incarceration. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1984, 19, 44–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemura, S.; Woodward, A.A.; Amerena, R.; Drew, J. Early repair of inguinal hernia in premature babies. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 1999, 15, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, R.; Gholoum, S.; Laberge, J.M.; Puligandla, P. Prematurity, not age at operation or incarceration, impacts complication rates of inguinal hernia repair. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 908–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borenstein, S.H.; To, T.; Wajja, A.; Langer, J.C. Effect of subspecialty training and volume on outcome after pediatric inguinal hernia repair. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2005, 40, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turial, S.; Enders, J.; Krause, K.; Schier, F. Laparoscopic Inguinal Herniorrhaphy in Premature Infants. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 20, 371–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonoff, M.B.; Kreykes, N.S.; Saltzman, D.A.; Acton, R.D. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Surgery hernia survey revisited. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2005, 40, 1009–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biliškov, A.; Ivančev, B.; Pogorelić, Z. Effects on Recovery of Pediatric Patients Undergoing Total Intravenous Anesthesia with Propofol versus Ketofol for Short—Lasting Laparoscopic Procedures. Children 2021, 8, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Horwood, J.F.; Clements, C.; Leyland, D.; Corbett, H.J. Complications of inguinal herniotomy are comparable in term and premature infants. Hernia 2016, 20, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Toki, F.; Yamamoto, H.; Otake, S.; Oki, Y.; Kuwano, H. Outcomes of herniotomy in premature infants: Recent 10 year experience. Pediatr. Int. 2012, 54, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevešćanin, A.; Vickov, J.; Baloević, S.E.; Pogorelić, Z. Laryngeal Mask Airway Versus Tracheal Intubation for Laparoscopic Hernia Repair in Children: Analysis of Respiratory Complications. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2019, 30, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgmeier, C.; Schier, F. Cardiorespiratory complications after laparoscopic hernia repair in term and preterm babies. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2013, 48, 1972–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Goede, B.; Verhelst, J.; Van Kempen, B.J.; Baartmans, M.G.; Langeveld, H.R.; Halm, J.A.; Kazemier, G.; Lange, J.F.; Wijnen, R.M.H. Very Low Birth Weight Is an Independent Risk Factor for Emergency Surgery in Premature Infants with Inguinal Hernia. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014, 220, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parelkar, S.V.; Oak, S.; Gupta, R.; Sanghvi, B.; Shimoga, P.H.; Kaltari, D.; Prakash, A.; Shekhar, R.; Gupta, A.; Bachani, M. Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in the pediatric age group—Experience with 437 children. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2010, 45, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, L.O.; Teitelbaum, D.H.; Caniano, D.A.; Vanik, P.E.; Martino, J.D.; Servick, J.D. Inguinal herniorrhaphy in young infants: Perianesthetic complications and associated preanesthetic risk factors. J. Clin. Anesth. 1992, 4, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.I.; Baker, C.; Patel, S.; Hebra, A.V.; Cina, R.A.; Streck, C.J.; Lesher, A.P. Long-term outcomes of pediatric laparoscopic needled-assisted inguinal hernia repair: A 10-year experience. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020, 56, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).