Abstract

Background: The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains a major global public health issue. People living with HIV (PLHIV) are among the vulnerable groups facing a higher risk of severe outcomes. Combining COVID-19 vaccination with HIV services can improve access and utilization of the vaccine among PLHIV although effective methods of delivery are yet to be ascertained. We conducted a scoping review to identify and describe models for delivering COVID-19 vaccines through HIV care services in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Methods: We used PRISMA-ScR guidelines to conduct the review. On 3rd and 4th February 2025, we searched PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE for studies on integrated COVID-19 vaccine delivery for PLHIV. Results: Three studies from sub-Saharan Africa reported call-back strategy, diverse partnership, and mixed service delivery models for implementing COVID-19 vaccination in HIV care services. Key strategies that were used included building capacity, generating demand, managing the supply chain, and involving stakeholders. The outcomes showed significant increases in vaccination coverage among PLHIV and reduced vaccine wastage. Conclusions: Integrating COVID-19 vaccination into HIV services is practical and effective in LMICs. It makes use of current infrastructure, partnerships, and local innovations.

1. Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is still a public health threat, even though the World Health Organization (WHO) no longer classifies it as a public health emergency of international concern [1]. The pandemic deeply affected nearly every part of society, including governments, healthcare systems, and global economies [2]. While various non-drug methods helped slow the spread of the virus, vaccination remains the main strategy for controlling COVID-19 [3]. Many studies have shown that traditional mRNA vaccines effectively prevent severe symptomatic infection, hospitalization, and death and are safe and effective across different populations [4,5].

At the start of the vaccine rollout, the WHO’s COVID-19 vaccine prioritization roadmap suggested focusing on reducing illness and death, especially with limited vaccine supply starting with healthcare workers and other frontline personnel due to their increased exposure and essential roles in responding to the pandemic [6]. Despite being an understandable approach, it unintentionally ignored the broader view of health as a basic human right, especially for other vulnerable groups. Evidence consistently shows that people aged 65 and older and those with existing medical conditions (comorbidities) are at much greater risk of getting COVID-19, experiencing long hospital stays, and facing worse health outcomes [7,8,9,10]. Several studies have also shown that people living with HIV are at higher risk of severe COVID-19 infections, qualifying them a priority group for preventive measures including vaccination [11,12]. While many PLHIV are willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine, the actual uptake has not been satisfactory [13]. Several reports show strong evidence that COVID-19 vaccines are safe for people living with HIV (PLHIV), with mostly mild, self-limited adverse events and good immunogenicity, particularly after booster doses [14,15,16,17]. Despite this, there is still a significant gap in specialized vaccine delivery strategies for PLHIV. Most COVID-19 vaccination models, like mass vaccination sites, mobile clinics, fixed-post immunizations, and home services, were designed with the general population in mind [18,19] leaving the specific needs and access challenges faced by PLHIV unaddressed.

Recently, some countries have started incorporating COVID-19 vaccine delivery into regular healthcare services [20]. For instance, Heidari et al. describe models where vaccination clinics are located alongside services such as needle exchange programs, HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) testing for people who inject drugs, and antenatal care visits for pregnant women at 20 weeks [21]. These integrated methods have improved vaccine access, especially by reducing the logistical and financial burdens related to transportation, childcare, and time off work. In addition, regular contact with healthcare providers and vaccine counseling in these settings have helped build trust and increase vaccine confidence [20,22]. Moreover, health systems facing critical staffing gaps often find it hard to offer separate COVID-19 vaccination services as vaccine supply improves and efforts to reach people unfamiliar with adult vaccination programs have generally faced setbacks due to vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, and ongoing structural obstacles [23].

To effectively tackle vaccine distribution for people living with HIV and enhance health outcomes, identifying and mapping the existing models used to deliver vaccines to this population is essential. Understanding these methods can help policymakers and healthcare providers design better research and implementation strategies. Furthermore, gaining a deeper insight into these models may offer helpful guidance on how future vaccine delivery and its integration into primary healthcare and vaccination programs can be improved, particularly in LMICs. This scoping review explored existing COVID-19 vaccine integration models in LMICs focusing on approaches relevant to PLHIV.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

We carried out a scoping review of the literature according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [24]. We performed a systematic search of the literature from 03 to 04 February 2025 across four electronic databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE. The scoping review protocol was registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY), registration number: INPLASY2025100010; DOI: 10.37766/inplasy2025.10.0010 [25].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined using a modified Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes (PICO) framework focusing on studies involving PLHIV, men and women aged 18 and older residing in LMICs. Since our main interest was on how COVID-19 vaccination is integrated into HIV care services, we included studies that reported on strategies or models for delivering COVID-19 vaccines through HIV care platforms. Eligible study designs included all empirical research approaches: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods such as observational studies, randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, cohort and case-control studies, and single-case reports. We excluded studies if they were conducted outside of LMICs or did not focus on vaccine integration specifically for PLHIV.

2.3. Information Sources

We developed a thorough search strategy using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Boolean operators. This strategy combined terms related to PLHIV, COVID-19 vaccines, and integration strategies. The search terms and strategies were based on an initial scoping search and consultations with experts. Full details of the search strategy and the databases used are provided in Appendix A.

2.4. Selection Process

Two reviewers, PK and SB independently carried out the screening and review process using Rayyan, an online tool for managing systematic reviews. Any differences in opinion were resolved through discussion or with input from third reviewers, NMM or RC. In the first screening phase, we assessed titles and abstracts for eligibility. We then performed full-text screening on all records that met the inclusion criteria. We documented the reasons for excluding studies during the full-text review stage.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

We extracted data from the included studies using a standardized form created by the authors and summarized it in a table. The structured extraction included study characteristics, model type, model features, strategies, outcomes, and lessons learned. We performed a narrative synthesis with tabulation to analyze the data.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

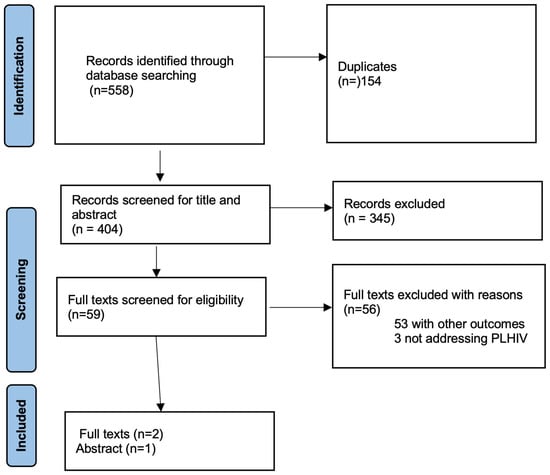

The search resulted in 558 records. After removing 154 duplicates, 404 records were left for title and abstract screening. From these, 59 records were found to be potentially relevant and were reviewed in full text. Ultimately, three studies met the inclusion criteria and were part of the final analysis as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

All included studies were from sub-Saharan Africa, specifically Tanzania (n = 2) and Zambia (n = 1) as shown in Table 1. They focused on people living with HIV, their families, and healthcare workers. The Tanzanian studies [26,27] included a case study and an abstract presented at the National Health Summit. The Zambian study was a report from the national COVID-19 vaccination campaign [23].

Table 1.

Summary of the included Studies.

3.3. Integration Models Used for COVID-19 Vaccination and HIV Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

The reviewed studies identified three distinct models for integrating COVID-19 vaccine delivery with HIV care services. These include the call-back strategy, the diverse partnership model, and a mixed service delivery model as explained in Table 2 below.

Table 2.

Identified COVID-19 Vaccine Delivery Models.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review to focus on models and/or strategies for integrating COVID-19 vaccination with HIV care and services in low- and middle-income countries. Two included studies successfully applied common themes that contributed to their effectiveness [23,26].

The mixed service delivery model used in Zambia focused on planning and coordination. It aimed to use existing in-country systems, programs, and resources for COVID-19 vaccination through joint planning with the Ministry of Health, funding organizations, and provincial representatives. Similarly, the diverse partnership model in Tanzania highlighted cooperation and coordination as key factors for improving vaccine uptake. Strong collaboration between healthcare providers and public health agencies is recognized as crucial for successful health programs and interventions [29,30].

Building capacity was a major theme in all the studies. This included promoting vaccine awareness and education to combat misconceptions, as well as offering incentives to meet vaccination goals. Community health workers (CHWs) served as important links between healthcare workers and communities, while training healthcare workers in community mobilization and service delivery helped address the challenges of static service models. This method increased access by providing vaccines in public locations like markets, malls, and churches. Past studies have also emphasized the important role of community mobilization in improving intervention acceptance, enabling communities to take charge, and encouraging social and behavior change through peer support and local solutions [31,32,33,34,35].

Effective integration required solid logistics and supply chain systems along with clear monitoring and evaluation methods. Both models focused on making sure there was a steady vaccine supply for district-level populations, using existing infrastructure for vaccine storage when possible. Research suggests that single-dose vaccines could increase coverage, and that strong involvement from stakeholders is necessary to support vaccine purchase, transportation, and distribution [36]. Also, reliable supply chains for health commodities have shown to be essential to strong health systems and are important for reaching national and regional health security goals [37].

The call-back strategy was consistently used across all models to increase vaccine acceptance and uptake among people living with HIV. This strategy involved creating targeted promotional materials that highlighted the increased risk of severe COVID-19 illness for this group. Regular patient reminder calls informed individuals about vaccine availability at HIV clinics, while use of patient champions helped reach PLHIV within their communities. Evidence supports the effectiveness of the call-back approach in enhancing patient understanding, maintaining treatment plans, and reducing unnecessary healthcare visits [38].

Limitations

This scoping review focuses on a topic that is very important for public health. However, the studies included are the lowest level in the hierarchy of evidence and are only relevant to the African context. The lack of higher-level evidence, like systematic reviews or randomized controlled trials, limits how far we can apply our findings beyond the specific areas we looked at. Even with a thorough search strategy, we found no eligible studies from outside Africa, which restricts the geographic range of the review. Deliberate strategies such as collaborating with international HIV and immunization programs could help access data and insights from underrepresented regions. This could help expand research coverage despite acknowledged limitations. Additionally, future research should aim to fill evidence gaps in regions outside sub-Saharan Africa.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review shows that incorporating COVID-19 vaccination into trusted health platforms, especially HIV services, can significantly increase uptake among high-risk groups like people living with HIV in low- and middle-income countries. The reviewed models were successful by including vaccination in familiar care pathways, empowering healthcare workers to adjust delivery at the facility level and encouraging equitable access through community involvement and focused outreach. These methods strengthened the connection between vaccine demand and supply while reducing waste and leveraging the trust patients have in their providers.

The experiences from Tanzania and Zambia highlight that innovation tailored to specific contexts, along with strong partnerships across political, government, religious, and community areas, can achieve rapid and lasting improvements, even in resource-limited environments. Expanding these models will need ongoing investment, political support, and a willingness to adjust to future public health challenges.

Recommendations for Future Vaccine Implementation

Based on the lessons learnt in this review, we suggest the following priority actions for policymakers, implementers, and partners in other LMICs to adapt or test:

- Using existing health platforms such as building on established systems like HIV clinics and community health programs is critical for effective and sustainable vaccination integration.

- Provide ongoing training for healthcare workers in vaccine delivery, community engagement in order to address vaccine hesitancy.

- Improve Community Engagement and Education to ensure use of culturally relevant communication strategies with community leaders, patient advocates, and civil society in order to boost vaccine awareness and uptake.

- LMICs should aim to implement reminder and follow-up systems such as using call-back and other reminder methods to reduce missed opportunities and increase completion rates, particularly among PLHIV.

- Remove barriers to ensure equitable access. This could be achieved by providing transport reimbursements, mobile services, and flexible hours to address logistical and economic challenges. Effective partnerships with funders and other organizations would be key in supporting these initiatives.

- Strengthen data systems and monitoring to provide strong monitoring and evaluation systems for tracking coverage and identifying gaps.

- Consider fostering multisectoral partnerships through engaging with government agencies, Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs), religious and political leaders, and donors to facilitate coordinated resources, advocacy, and policy support.

- Plan for strong supply chain for keeping a steady vaccine supply that would likely avoid stockouts and waste especially in remote areas.

- Encourage use of implementation science to assess and expand new methods like mixed service delivery and community-based vaccination.

- Preparing for future health emergencies such as building rapid integration and adaptation processes within health systems would lead to quick response to emerging infectious disease threats.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.M.M., S.M.-J. and C.N.; Methodology: N.M.M.; Investigation: N.M.M. and R.C.; Data curation: N.M.M., R.C., S.B. and P.K.; Data analysis: S.B. and P.K.; Writing Review and editing: N.M.M., R.C., S.B. and P.K.; Supervision: N.M.M., R.C., C.N., A.M. and S.M.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by UNICEF Malawi; Program Code: 2690/A0/06/021/004/008 System Strengthening for Risk Informed Programme.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data can be available in English for the readers and made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.

Appendix A. Search Strategy

Table A1.

Detailed search strategy for Electronic Databases.

Table A1.

Detailed search strategy for Electronic Databases.

| Database | Query Number | Query |

|---|---|---|

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | |

| EMBASE Search Strategy | #3 | (‘low-income countr*’ OR ‘middle-income countr*’ OR ‘developing countr*’ OR ‘low-resource countr*’ OR ‘resource-poor countr*’ OR ‘underdeveloped countr*’ OR ‘less developed countr*’ OR ‘global south’ OR ‘sub-saharan africa’/exp OR ‘sub-saharan africa’ OR ‘latin america’/exp OR ‘latin america’ OR ‘south asia’/exp OR ‘south asia’ OR ‘africa’/exp OR ‘africa’ OR ‘southeast asia’/exp OR ‘southeast asia’ OR ‘central america’/exp OR ‘central america’ OR ‘eastern europe’/exp OR ‘eastern europe’ OR ‘caribbean’/exp OR ‘caribbean’ OR ‘pacific islands’/exp OR ‘pacific islands’ OR ‘afghanistan’/exp OR afghanistan OR ‘angola’/exp OR angola OR ‘bangladesh’/exp OR bangladesh OR ‘benin’/exp OR benin OR ‘bhutan’/exp OR bhutan OR ‘bolivia’/exp OR bolivia OR ‘botswana’/exp OR botswana OR burkina) AND faso OR ‘burundi’/exp OR burundi OR… |

| #2 | ‘HIV infections’/exp OR ‘HIV infections’ OR ‘HIV’/exp OR ‘HIV’ OR ‘HIV/AIDS’/exp OR ‘HIV/AIDS’ OR ‘people living with HIV’/exp OR ‘people living with HIV’ OR ‘PLHIV’ OR ‘HIV care’/exp OR ‘HIV care’ OR ‘HIV services’ OR ‘HIV treatment’:ti,ab | |

| #1 | ‘COVID-19 vaccines’/exp OR ‘COVID-19 vaccines’ OR ‘SARS-CoV-2 vaccine’/exp OR ‘SARS-CoV-2 vaccine’ OR ‘COVID-19 immunization’ OR ‘COVID-19 vaccination’:ti,ab | |

| Cochrane Library Search Strategy | ID | Search Query |

| #1 | (“COVID-19 Vaccines” OR “SARS-CoV-2 vaccine” OR “COVID-19 immunization” OR “COVID-19 vaccination”):ti,ab,kw | |

| #2 | (“HIV Infections” OR “HIV” OR “HIV/AIDS” OR “People Living with HIV” OR “PLHIV” OR “HIV Care” OR “HIV Services” OR “HIV Treatment”):ti,ab,kw | |

| #3 | (((low-income NEXT countr*) OR (middle-income NEXT countr*) OR (developing NEXT countr*) OR (low-resource NEXT countr*) OR (resource-poor NEXT countr*) OR (underdeveloped NEXT countr*) OR (less NEXT developed NEXT countr*) OR (global NEXT south) OR (sub-Saharan NEXT Africa) OR (Latin NEXT America) OR (South NEXT Asia) OR (Africa) OR (Southeast NEXT Asia) OR (Central NEXT America) OR (Eastern NEXT Europe) OR (Caribbean) OR (Pacific NEXT Islands)) OR (Afghanistan OR Angola OR Bangladesh OR Benin OR Bhutan OR Bolivia OR Botswana OR Burkina NEXT Faso OR Burundi OR Cambodia OR Cameroon OR Central NEXT African NEXT Republic OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR Democratic NEXT Republic NEXT of NEXT the NEXT Congo OR Djibouti OR Egypt OR El NEXT Salvador OR Eritrea OR Eswatini OR Ethiopia OR Fiji OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guatemala OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Haiti OR Honduras OR India OR Indonesia OR Kenya OR Kiribati OR Korea, NEXT North OR Kyrgyzstan OR Laos OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Micronesia OR Mongolia OR Mozambique OR Myanmar OR Nepal OR Nicaragua OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Pakistan OR Papua NEXT New NEXT Guinea OR Philippines OR Rwanda OR Samoa OR Senegal OR Sierra NEXT Leone OR Solomon NEXT Islands OR Somalia OR South NEXT Sudan OR Sudan OR Syria OR Tajikistan OR Tanzania OR Timor-Leste OR Togo OR Tonga OR Turkmenistan OR Uganda OR Uzbekistan OR Vanuatu OR Venezuela OR Vietnam OR Yemen OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe)):ti,ab,kw | |

| #4 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 | |

| Web of Science Search Strategy | ID | Search Query |

| 1 | TS = (“COVID-19 Vaccines” OR “SARS-CoV-2 vaccine” OR “COVID-19 immunization” OR “COVID-19 vaccination”) | |

| 2 | TS = (“HIV Infections” OR “HIV” OR “HIV/AIDS” OR “People Living with HIV” OR “PLHIV” OR “HIV Care” OR “HIV Services” OR “HIV Treatment”) | |

| 3 | TS = (“Health Services Integration” OR “Integrated Care” OR “Service Delivery Models” OR “Integration Models” OR “Health System Integration” OR “Health Services Delivery”) | |

| 4 | TS = (“low-income countr*” OR “middle-income countr*” OR “developing countr*” OR “low-resource countr*” OR “resource-poor countr*” OR “underdeveloped countr*” OR “less developed countr*” OR “global south” OR “sub-Saharan Africa” OR “Latin America” OR “South Asia” OR “Africa” OR “Southeast Asia” OR “Central America” OR “Eastern Europe” OR “Caribbean” OR “Pacific Islands” OR Afghanistan OR Angola OR Bangladesh OR Benin OR Bhutan OR Bolivia OR Botswana OR Burkina Faso OR Burundi OR Cambodia OR Cameroon OR Central African Republic OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR Djibouti OR Egypt OR El Salvador OR Eritrea OR Eswatini OR Ethiopia OR Fiji OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guatemala OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Haiti OR Honduras OR India OR Indonesia OR Kenya OR Kiribati OR “Korea, North” OR Kyrgyzstan OR Laos OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Micronesia OR Mongolia OR Mozambique OR Myanmar OR Nepal OR Nicaragua OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Pakistan OR “Papua New Guinea” OR Philippines OR Rwanda OR Samoa OR Senegal OR “Sierra Leone” OR “Solomon Islands” OR Somalia OR “South Sudan” OR Sudan OR Syria OR Tajikistan OR Tanzania OR Timor-Leste OR Togo OR Tonga OR Turkmenistan OR Uganda OR Uzbekistan OR Vanuatu OR Venezuela OR Vietnam OR Yemen OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe) | |

| 5 | #1 AND #2 AND #4 | |

| PubMed Search Strategy | Search number | Query |

| 6 | ((“COVID-19 Vaccines” OR “SARS-CoV-2 vaccine” OR “COVID-19 immunization” OR “COVID-19 vaccination”) AND (“HIV Infections” OR “HIV” OR “HIV/AIDS” OR “People Living with HIV” OR “PLHIV” OR “HIV Care” OR “HIV Services” OR “HIV Treatment”)) AND (“low-income countr*” OR “middle-income countr*” OR “developing countr*” OR “low-resource countr*” OR “resource-poor countr*” OR “underdeveloped countr*” OR “less developed countr*” OR “global south” OR “sub-Saharan Africa” OR “Latin America” OR “South Asia” OR “Africa” OR “Southeast Asia” OR “Central America” OR “Eastern Europe” OR “Caribbean” OR “Pacific Islands” OR Afghanistan OR Angola OR Bangladesh OR Benin OR Bhutan OR Bolivia OR Botswana OR Burkina Faso OR Burundi OR Cambodia OR Cameroon OR Central African Republic OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR Djibouti OR Egypt OR El Salvador OR Eritrea OR Eswatini OR Ethiopia OR Fiji OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guatemala OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Haiti OR Honduras OR India OR Indonesia OR Kenya OR Kiribati OR Korea, North OR Kyrgyzstan OR Laos OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Micronesia OR Mongolia OR Mozambique OR Myanmar OR Nepal OR Nicaragua OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Pakistan OR Papua New Guinea OR Philippines OR Rwanda OR Samoa OR Senegal OR Sierra Leone OR Solomon Islands OR Somalia OR South Sudan OR Sudan OR Syria OR Tajikistan OR Tanzania OR Timor-Leste OR Togo OR Tonga OR Turkmenistan OR Uganda OR Uzbekistan OR Vanuatu OR Venezuela OR Vietnam OR Yemen OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe) | |

| 5 | “low-income countr*” OR “middle-income countr*” OR “developing countr*” OR “low-resource countr*” OR “resource-poor countr*” OR “underdeveloped countr*” OR “less developed countr*” OR “global south” OR “sub-Saharan Africa” OR “Latin America” OR “South Asia” OR “Africa” OR “Southeast Asia” OR “Central America” OR “Eastern Europe” OR “Caribbean” OR “Pacific Islands” OR Afghanistan OR Angola OR Bangladesh OR Benin OR Bhutan OR Bolivia OR Botswana OR Burkina Faso OR Burundi OR Cambodia OR Cameroon OR Central African Republic OR Chad OR Comoros OR Congo OR “Democratic Republic of the Congo” OR Djibouti OR Egypt OR El Salvador OR Eritrea OR Eswatini OR Ethiopia OR Fiji OR Gambia OR Ghana OR Guatemala OR Guinea OR Guinea-Bissau OR Haiti OR Honduras OR India OR Indonesia OR Kenya OR Kiribati OR Korea, North OR Kyrgyzstan OR Laos OR Lesotho OR Liberia OR Madagascar OR Malawi OR Mali OR Mauritania OR Micronesia OR Mongolia OR Mozambique OR Myanmar OR Nepal OR Nicaragua OR Niger OR Nigeria OR Pakistan OR Papua New Guinea OR Philippines OR Rwanda OR Samoa OR Senegal OR Sierra Leone OR Solomon Islands OR Somalia OR South Sudan OR Sudan OR Syria OR Tajikistan OR Tanzania OR Timor-Leste OR Togo OR Tonga OR Turkmenistan OR Uganda OR Uzbekistan OR Vanuatu OR Venezuela OR Vietnam OR Yemen OR Zambia OR Zimbabwe | |

| 3 | (“COVID-19 Vaccines” OR “SARS-CoV-2 vaccine” OR “COVID-19 immunization” OR “COVID-19 vaccination”) AND (“HIV Infections” OR “HIV” OR “HIV/AIDS” OR “People Living with HIV” OR “PLHIV” OR “HIV Care” OR “HIV Services” OR “HIV Treatment”) | |

| 4 | “Health Services Integration” OR “Integrated Care” OR “Service Delivery Models” OR “Integration Models” OR “Health System Integration” OR “Health Services Delivery” | |

| 2 | “HIV Infections” OR “HIV” OR “HIV/AIDS” OR “People Living with HIV” OR “PLHIV” OR “HIV Care” OR “HIV Services” OR “HIV Treatment” | |

| 1 | “COVID-19 Vaccines” OR “SARS-CoV-2 vaccine” OR “COVID-19 immunization” OR “COVID-19 vaccination” |

References

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Suryanarayanan, P.; Tsou, C.H.; Poddar, A.; Mahajan, D.; Dandala, B.; Madan, P.; Agrawal, A.; Wachira, C.; Samuel, O.M.; Bar-Shira, O.; et al. AI-assisted tracking of worldwide non-pharmaceutical interventions for COVID-19. Sci. Data 2021, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aho Glele, L.S.; de Rougemont, A. Non-pharmacological strategies and interventions for effective COVID-19 control: A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulia, D.L. Interim recommendations for use of bivalent mRNA COVID-19 vaccines for persons aged ≥6 months, United States, April 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statement for Healthcare Professionals: How COVID-19 Vaccines Are Regulated for Safety and Effectiveness (Revised March 2022) [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-05-2022-statement-for-healthcare-professionals-how-covid-19-vaccines-are-regulated-for-safety-and-effectiveness (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO SAGE Roadmap for Prioritizing Uses of COVID-19 Vaccines; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Vaccines-SAGE-Prioritization-2023.1 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Fang, X.; Li, S.; Yu, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L.; Li, W.; Jia, H.; et al. Epidemiological, comorbidity factors with severity and prognosis of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging 2020, 12, 12493–12503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, M.; Puri, A.; Wang, T.; Guo, S. Comparison of clinical manifestations, pre-existing comorbidities, complications and treatment modalities in severe and non-severe COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Prog. 2021, 104, 00368504211000906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.; Alsrhani, A.; Zafar, A.; Javed, H.; Junaid, K.; Abdalla, A.E.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; Ahmed, Z.; Younas, S. COVID-19 and comorbidities: Deleterious impact on infected patients. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanad, C.; García-Blas, S.; Tarazona-Santabalbina, F.; Sanchis, J.; Bertomeu-González, V.; Fácila, L.; Ariza, A.; Núñez, J.; Cordero, A. The effect of age on mortality in patients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis with 611,583 subjects. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 915–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menza, T.W.; Capizzi, J.; Zlot, A.I.; Barber, M.; Bush, L. COVID-19 vaccine uptake among people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 2224–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosioni, J.; Blanco, J.L.; Reyes-Urueña, J.M.; Davies, M.A.; Sued, O.; Marcos, M.A.; Martínez, E.; Bertagnolio, S.; Alcamí, J.; Miro, J.M.; et al. Overview of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults living with HIV. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, e294–e305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govere-Hwenje, S.; Jarolimova, J.; Yan, J.; Khumalo, A.; Zondi, G.; Ngcobo, M.; Wara, N.J.; Zionts, D.; Bogart, L.M.; Parker, R.A.; et al. Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination among people living with HIV in a high HIV prevalence community. Res. Sq. 2022, rs.3.rs-824083. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9016651/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Chan, D.; Wong, N.; Wong, B.; Chan, J.; Lee, S. Three-dose primary series of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine for persons living with HIV, Hong Kong. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 2130–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Highleyman, L. More Evidence COVID Vaccines Work Well for People with HIV. Available online: https://www.poz.com/article/evidence-covid-vaccines-work-people-hiv (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Zhang, H.; Deng, X.; Dai, R.; Fu, J.; Ding, L.; Hu, X.; Sun, P.; Shu, R.; Chen, L.; Xu, X. Inadequate immune response to inactivated COVID-19 vaccine among older people living with HIV: A prospective cohort study. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e00688-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khawcharoenporn, T.; Hanvivattanakul, S. Safety profiles of three major types of COVID-19 vaccine among two cohorts of people living with HIV. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2023, 10 (Suppl. S2), ofad500.1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.S.; Mohareb, A.M.; Valdes, C.; Price, C.; Jollife, M.; Regis, C.; Munshi, N.; Taborda, E.; Lautenschlager, M.; Fox, A.; et al. Expanding COVID-19 vaccine access to underserved populations through implementation of mobile vaccination units. Prev. Med. 2022, 163, 107226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianfredi, V.; Pennisi, F.; Lume, A.; Ricciardi, G.E.; Minerva, M.; Riccò, M.; Odone, A.; Signorelli, C. Challenges and opportunities of mass vaccination centers in COVID-19 times: A rapid review of literature. Vaccines 2021, 9, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabia, S.; Wonodi, C.B.; Vilajeliu, A.; Sussman, S.; Olson, K.; Cooke, R.; Udayakumar, K.; Twose, C.; Ezeanya, N.; Adefarrell, A.A.; et al. Experiences, enablers, and challenges in service delivery and integration of COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines 2023, 11, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari, O.; Meyer, D.; O’conor, K.J.; Cargill, V.; Patch, M.; Farley, J.E. COVID-19 Vaccination and Communicable Disease Testing Services’ Integration Within a Syringe Services Program: A Program Brief. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2022, 33, 348–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cater, K.; Yazbek, J.; Morris, P.; Watts, K.; Whitehouse, C. Developing a fast-track COVID-19 vaccination clinic for pregnant people. Br. J. Midwifery 2022, 30, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobo, P.; Hines, J.Z.; Chilengi, R.; Auld, A.F.; Agolory, S.G.; Silumesii, A.; Nkengasong, J. Leveraging HIV program and civil society to accelerate COVID-19 vaccine uptake, Zambia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28 (Suppl. S1), S244–S246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INPLASY. International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols. 2025. Available online: https://inplasy.com (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Jalloh, M.F.; Tinuga, F.; Dahoma, M.; Rwebembera, A.; Kapologwe, N.A.; Magesa, D.; Mukurasi, K.; Rwabiyago, O.E.; Kazitanga, J.; Miller, A.; et al. Accelerating COVID-19 vaccination among people living with HIV and health care workers in Tanzania: A case study. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2024, 12, e2300281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magadula, E.; Mbwaga, S.; Mutasingwa, F.; Herman, E. Abstracts of the 9th Tanzania Health Summit. BMC Proc. 2023, 17 (Suppl. S13), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olateju, A.; Peters, M.A.; Osaghae, I.; Alonge, O. How service delivery implementation strategies can contribute to attaining universal health coverage: Lessons from polio eradication using an implementation science approach. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Health Partnership. The Health Partnership Model [Internet]. Available online: https://www.globalhealthpartnerships.org (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Khanpoor, H.; Alizadeh, A.; Khosravizadeh, O.; Amerzadeh, M.; Rafiei, S. A mixed-methods model for healthcare system responsiveness to public health: Insights from Iranian experts. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2025, 23, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussos, S.T.; Fawcett, S.B. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2000, 21, 369–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, A.Y.; Tomoh, B.O.; Soyege, O.S.; Nwokedi, C.N.; Mbata, A.O.; Balogun, O.D.; Iguma, D.R. Preventive health programs: Collaboration between healthcare providers and public health agencies. Int. J. Pharma Growth Res. Rev. 2024, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzyamba, C.; Groot, W.; Tomini, S.M.; Pavlova, M. The role of community mobilization in maternal care provision for women in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review of studies using an experimental design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017, 17, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C. Community mobilisation in the 21st century: Updating our theory of social change? J. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackerman Gulaid, L.; Kiragu, K. Lessons learnt from promising practices in community engagement for the elimination of new HIV infections in children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive: Summary of a desk review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2012, 15 (Suppl. S2), 17390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020. Annex 2 [Internet]. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/vaccines-and-immunization/gvap-annex2.pdf?sfvrsn=b7167ba7_2 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Donato, S.; Roth, S.; Parry, J. Strong Supply Chains Transform Public Health. ADB Briefs [Internet]. 2016. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/214036/strong-supply-chains.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Luciani-McGillivray, I.; Cushing, J.; Klug, R.; Lee, H.; Cahill, J.E. Nurse-led call back program to improve patient follow-up with providers after discharge from the emergency department. J. Patient Exp. 2020, 7, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).