Abstract

Background: Vitamin D (VD) insufficiency is present in chronic pancreatitis (CP), leading to increased cardiovascular risk, bone complications, impaired quality of life, and increased mortality. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of VD deficiency in patients with CP and to assess its relationship to CP progression and associated cardiovascular complications. Methods: Seventy patients were enrolled and evaluated for pancreatic exocrine insufficiency by fecal elastase-1, CP severity by M-ANNHEIM classification, cardiovascular risk by 10-year risk mortality scores (SCORE and FRS), and for arterial stiffness using pulse wave velocity (PWV) at a. carotis and a. femoralis. Determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D was performed by an LC-MS/MS method. Resting energy expenditure was calculated using the Harris–Benedict formula. Results: Mean VD levels were 37.86 ± 24.36 nmol/L (range 3.854–99.874 nmol/L); only five patients were in sufficiency status. VD levels correlated significantly with body mass index (BMI) and resting energy expenditure. In patients with severe structural changes, we observed lower VD levels regardless of etiology (p < 0.01). VD levels were lower in patients with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI), p < 0.05. Patients with mild CP by M-ANNHEIM had lower levels of VD compared to moderate and advanced CP, p < 0.05. At a cut-off of VD 11.95 nmol/L, we verified pancreatic lithiasis with 89.4% sensitivity, 83.3% specificity, and AUC of 0.826 ± 0.113 (95% CI, 0.61–1). VD status worsened with the increase in the 10-year risk mortality by both SCORE and FRS and PWV, p < 0.05. Conclusions: Most of our patients with CP were VD insufficient. Monitoring of nutritional status in patients with CP is mandatory to prevent the development of malnutrition complications and the associated morbidity and mortality.

1. Introduction

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is a pathologic fibroinflammatory syndrome of the pancreas that causes irreversible anatomical changes and damage including inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis, and calcification of the pancreas with destruction of the gland’s structure, and thus, it affects normal digestion and absorption of nutrients [1,2]. The early phase is characterized by pain and recurrent pancreatitis episodes and complications, and the late phase is associated with the development of exocrine and/or endocrine insufficiency [3]. According to the latest theories, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency occurs when a reduction in the exocrine pancreatic secretion and/or intraluminal activity of pancreatic enzymes are present [4]. As a major consequence, patients suffer from malabsorption of nutrients, intestinal symptoms, and/or nutritional deficiencies [4,5]. Vitamin D is the mostly affected and reduced fat-soluble vitamin, being reported as deficient among more than 40% of patients with CP predominantly in alcoholic chronic pancreatitis [1,2,5]. As a steroid hormone regulating body levels of calcium and phosphorus, vitamin D is traditionally defined as a main factor for bone health and homeostasis; however, nowadays many studies highlight the role of vitamin D in metabolic homeostasis, anti-inflammation, immune regulation and tumor suppression, regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and autophagy [6,7,8,9]. Mortality from cardiovascular diseases remains the leading cause of death for the European population. Since 1990, research has been conducted and has verified the inverse association of vitamin D with the risk of cardiovascular diseases and its effect on cardiovascular disease mortality rates [10,11]. The fundamental aspects of the treatment of patients with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency include pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), cessation of smoking and alcohol consumption, diet, fat-soluble vitamins supplementation, and systematic monitoring with BMI and nutritional markers. The aim of this treatment concept is to normalize digestion, alleviate the symptoms and complications associated with pancreatic exocrine insufficiency, and prevent malnutrition-related morbidity and mortality, as well as disease progression [1,2,3,4]. The aim of this study was to determine the status of vitamin D and the prevalence of deficiency in patients with chronic pancreatitis and to assess gaps in the literature based on its relationship to CP progression and associated cardiovascular complications.

2. Materials and Methods

Seventy patients diagnosed with chronic pancreatitis were prospectively enrolled in this study. The inclusion criteria of the patients were age above 18 years, diagnosed with chronic pancreatitis by CT or MRCP, and present PEI on PERT. Exclusion criteria were previous hospitalization due to cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, or revascularization procedures), liver cirrhosis, and vitamin D supplementation. PEI was diagnosed by fecal elastase-1, and the received PERT was at a mean dose of 82,000 IU per day. Cardiovascular risk (CVR) was evaluated by score systems. Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE Risk Chart) was performed with respect to gender, age, total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and smoking status, and the 10-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease was evaluated by low risk (score <1%), moderate risk (score ≥1% and <5%), high risk (score ≥5% and <10%), and very high risk (score ≥10%) [12,13]. In addition, we used the Framingham Coronary Heart Disease Risk Score (FRS), which estimates the absolute risk of a heart attack in 10 years, based on gender, age, total cholesterol and HDL, systolic blood pressure, ongoing treatment for hypertension, diabetes mellitus comorbidity, and smoking status [14]. CVR by FRS was defined as low (score <10%), moderate (score between 10 and 19%), and high (score above 20%). The cardiovascular status and risk were further assessed by the arterial stiffness using pulse wave velocity (PWV) at a. carotis and a. femoralis. Diabetes mellitus was newly diagnosed based on accepted criteria for fasting glucose levels (above 7.0 mmol/L) and HbA1c levels (above 6.5%). The imaging morphological data was evaluated by Cambridge classification for CT/MRCP (grade I-IV) [15]. The severity of chronic pancreatitis was assessed by the M-ANNHEIM classification using the following factors: abdominal pain, therapeutic pain control, pancreatic surgical interventions, exocrine and endocrine insufficiency, morphological status of the pancreas, and the presence of severe organ complications [16]. Determination of 25-hydroxyvitamin D was performed by the LC-MS/MS method. The vitamin D status as a major nutritional marker was assessed as severe deficiency (<25 nmol/L), deficiency (25–50 nmol/L), insufficiency (50–75 nmol/L), and sufficiency (>75 nmol/L). Resting energy expenditure was calculated using the Harris–Benedict formula: males = 66.5 + (13.75 × kg) + (5.003 × cm) − (6.775 × age) and females = 655.1 + (9.563 × kg) + (1.850 × cm) − (4.676 × age) [17,18].

Quantitative data of the statistical analysis were presented as mean, standard deviations (SD) and 95% Confidence Interval for mean, range, or percentages. Quantitative data were analyzed by Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test. Measured data were compared using ANOVA after confirming normal distribution by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables were compared, and qualitative data were analyzed by Fisher’s exact and linear-by-linear Chi-square tests, as appropriate. Parametric and nonparametric correlations were analyzed by Pearson and Spearman’s rho correlations as appropriate. Statistical significance was assumed at a p-value < 0.05.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Science Fund, Bulgaria, Grant № KП-06-M 33/2, 2019 and KП-06-H83/5, 2024.

3. Results

Seventy patients (45 males and 25 females, mean age 54.01 ± 13.46 years) were enrolled in this study. Alcohol abuse was the most common etiology. Forty-three patients were smokers. Diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension were reported comorbidities in 18 and 20 patients, respectively. Severe pancreatic insufficiency with fecal elastase–1 levels below 50 μg/g feces was found in 21 patients. The most commonly reported symptom by patients during PERT administration was pain, followed by weight loss and steatorrhea as signs of suboptimal dosage. Using the M-ANNHEIM criteria, the severity of CP was assessed, and patients were divided into 3 groups according to the severity of CP, with 20 in group A with mild CP, 38 in group B with moderate CP, and 12 in group C with advanced CP. No significant correlation was found between the severity of CP according to M-ANNHEIM in terms of gender, age, and duration of the disease, p > 0.05. However, in patients with moderate and advanced CP, alcohol consumption and smoking were significantly more frequently reported (p = 0.013 and p = 0.013). With the progression of CP (groups B and C by M-ANNHEIM), endocrine dysfunction occurred with the development of diabetes, which was not found in all patients with mild CP.

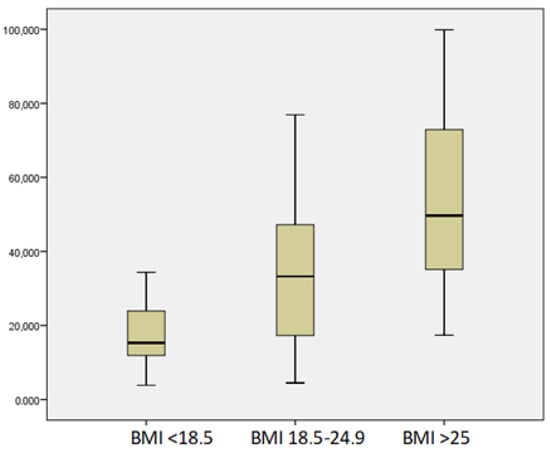

Mean vitamin D levels were 37.86 ± 24.36 nmol/L (range 3.854–99.874 nmol/L). Twenty-six patients had severe vitamin D deficiency; deficiency was found in 25 patients, another 14 had insufficiency, and only 5 patients were in sufficient status, with vitamin D levels more than 75 nmol/L. We found no significant relation between vitamin D levels and demographic data. Vitamin D levels correlated significantly with BMI (r = 0.38, p = 0.001) but not with other symptoms (weight loss, pain, or steatorrhea) (Figure 1). Twelve patients reported no symptoms; however, 10 of them had vitamin D levels of less than 50 nmol/L.

Figure 1.

Mean levels of vitamin D according to BMI.

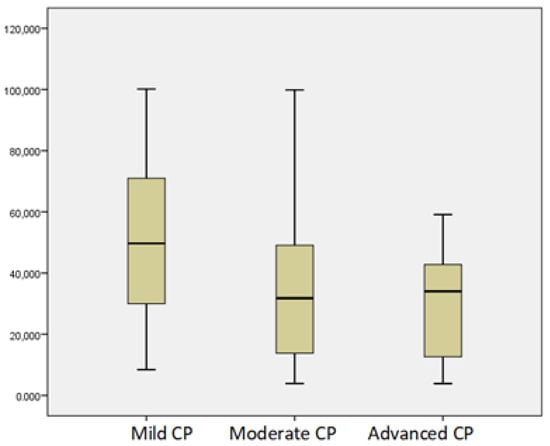

We observed a linear correlation between vitamin D and other nutritional parameters: prealbumin (r = 0.33, p = 0.004), retinol-binding protein (r = 0.43, p = 0.00), albumin (r = 0.29, p = 0.00), vitamin A (r = 0.322, p = 0.007), magnesium (r = 0.20, p = 0.037), and hemoglobin (r = 0.217, p = 0.02). Resting energy expenditure represents the energy expended by humans in an awake, resting, and interstitial state, and this correlated significantly with vitamin D levels (r = 0.53, p = 0.000). In patients with severe structural changes, we observed significantly lower vitamin D levels regardless of etiology (p < 0.01). Vitamin D levels were lower in patients with severe PEI, p < 0.05. Interestingly, patients with mild CP by M-ANNHEIM had lower levels of vitamin D compared to moderate and advanced CP, p < 0.05 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean levels of vitamin D according to severity of CP by M-ANNHEIM.

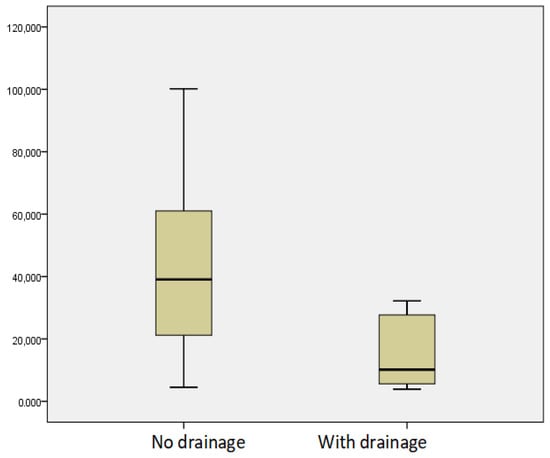

The relationship between vitamin D levels in patients with moderate and advanced CP who underwent drainage procedures due to the formation of pancreatic fluid collections (n = 7) and those without manipulation (n = 63) was studied, and significantly lower levels were found in the first group (p = 0.04) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Mean levels of vitamin D in patients with moderate and advanced CP depending on the drainage performed.

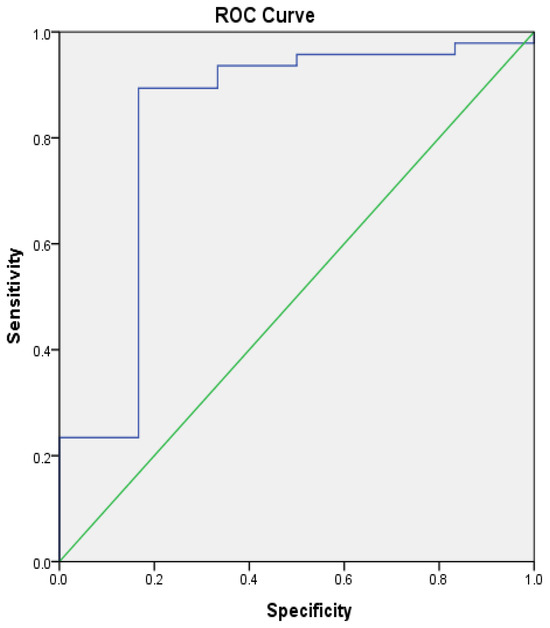

Eleven patients (15.71%) had pancreatolithiasis at CT/MRCP. We found an association of vitamin D with pancreatolithiasis. At a cut-off of vitamin D of 11.95 nmol/L, we verified pancreatic lithiasis with 89.4% sensitivity, 83.3% specificity, and AUC of 0.826 ± 0.113 (95% CI, 0.61–1) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

ROC analysis: vitamin D with pancreatic lithiasis. Green—reference line, blue—ROC Curve.

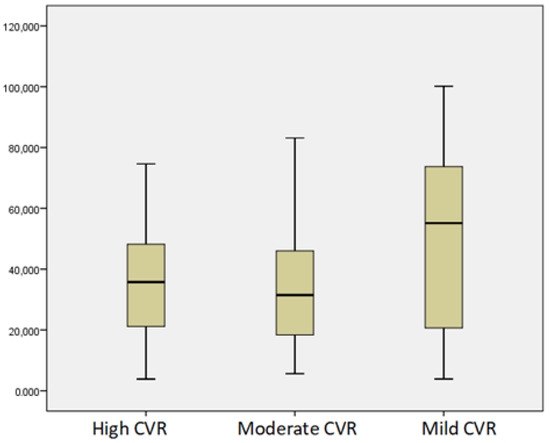

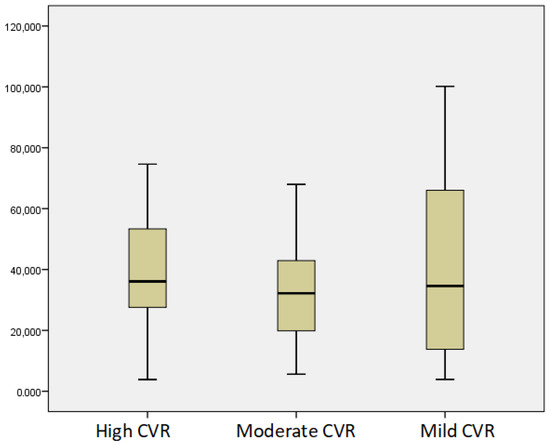

According to the SCORE Risk Chart, 24 patients had high CVR, 31 had moderate CVR, and 15 had mild CVR. According to FRS, 21 patients had high CVR, 17 had moderate CVR, and 32 had mild CVR. The vitamin D status worsened with the increase in the 10-year risk mortality by both SCORE and FRS, p < 0.05 (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Mean levels of vitamin D according to CVR by SCORE Risk Chart.

Figure 6.

Mean levels of vitamin D according to CVR by FRS.

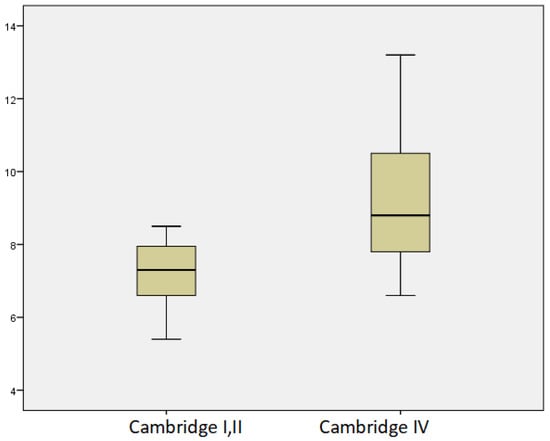

Lower vitamin D levels were associated with diabetes mellitus. The mean values of the PWV were 8.47 ± 1.64 m/s. We observed a significant linear correlation with age, p = 0.029, r = 0.385. Higher values of PWV were found in patients with diabetes (8.90 ± 1.53 m/s vs. 8.34 ± 1.80 m/s, p = 0.435), in smokers (8.27 ± 1.85 m/s vs. 8.32 ± 1.68 m/s, p = 0.53), and in those who reported alcohol consumption (9.31 ± 2.56 m/s vs. 8.15 ± 1.40 m/s, p = 0.088). However, those findings were non-significant trends. Significantly higher levels of PWV were associated with severe PEI, p = 0.003. There was no significant difference in PWV according to the severity of CP, with the lowest rate observed in patients with mild CP. There were significantly higher levels of PWV in patients with CP with severe structural changes (Cambridge grade IV) p = 0.027 (Figure 7). We found lower vitamin D levels with increasing PWV; however, this was not statistically significant.

Figure 7.

Mean levels of PWV in relation to morphological changes according to Cambridge classification.

By increasing and optimizing the dose of pancreatic enzymes in patients with pancreatic insufficiency, we demonstrated clinical improvement with a significant increase in BMI (p < 0.0001) and vitamin D, p = 0.026.

4. Discussion

With the development of chronic pancreatitis, immune dysregulation, acinar and islet dysfunction, and metaplasia are observed [19]. As a result of progressive and irreversible anatomical changes with the disruption of the structure and function of the gland, pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) and endocrine insufficiency (pancreatogenic diabetes type 3c), pain syndrome, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma may develop. Complications such as pancreatic pseudocysts, biliary strictures, gastric outlet obstruction syndrome, thrombosis of v. portae, v. lienalis, and v. mesenterica are verified. The quality of life of patients with chronic pancreatitis is often impaired [19]. Malabsorption is a typical complication of chronic or acute necrotizing pancreatitis and may be a consequence of pancreatic resection or pancreatic tumor. The main causes in adults are insufficient secretory capacity of the pancreatic gland due to loss or damage of the parenchyma, reduced stimulation of the gland, or the impaired release of enzymes into the duodenum due to obstruction of the pancreatic duct. The causes are further divided into primary and secondary. Malnutrition represents suboptimal nutritional status as a consequence of nutritional deficiencies in (proteins, fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, K, circulating essential amino acids, fatty acids, micronutrients, low levels of HDL, and apolipoprotein A1), which alter the functional status and have a major prognostic role due to the increased risk of osteoporosis, fractures, life-threatening cardiovascular events, and cachexia [1,3,4]. Fundamental aspects in the treatment of patients with PEI include pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT), which is a clinical standard for the treatment of PEI regardless of its etiology [4]. As the severity of chronic pancreatitis progresses, smoking and alcohol consumption have been shown to be more common, which further worsen pancreatic function and are a risk factor for pancreatic cancer and endocrine dysfunction. We demonstrated that alcoholic etiology is leading and with the progression of chronic pancreatitis (moderate and advanced), diabetes develops, which is absent in all patients with mild chronic pancreatitis. According to many studies today, it is very likely that a large proportion of patients with PEI receive suboptimal PERT with regard to malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins. Vitamin A, D, E, K deficiency correlates with the severity of steatorrhea in patients with chronic pancreatitis and PEI but can be caused by various mechanisms including suboptimal dietary intake, greater loss, increased requirements, impaired nutrient binding, antioxidant activity and fat malabsorption. Vitamin D deficiency and severe insufficiency are recorded in 72.86% of the studied patients in our group. We found suboptimal PERT with vitamin D levels below 50 nmol/L in most patients with moderate and advanced chronic pancreatitis. However, we found that patients with mild chronic pancreatitis by M-ANNHEIM present lower vitamin D levels compared to those with advanced stages. This could be explained by a lower dose of PERT on the one hand and by the increased inflammation or metabolic demands in the early stages of pancreatitis, which could lead to a higher utilization of vitamin D, resulting in lower serum levels. Vitamin D correlated significantly with BMI and other nutritional markers, so we suggest that vitamin D can be used as a marker for normal nutritional status. Vitamin D levels were associated with severe structural changes; therefore, we propose a mandatory screening for vitamin D deficiency for patients with grade III or IV by Cambridge classification. The relationship between vitamin D levels and pancreatic lithiasis is not well established. The anti-inflammatory effects and the regulation of calcium metabolism are impaired by vitamin D deficiency and might play a role in chronic pancreatic inflammation and pancreatic stone formation. Despite the small subgroup of patients with pancreatolithiasis in our cohort, we were able to demonstrate a cut-off of vitamin D to verify pancreatic stones. This finding is still a hypothesis; however, it raises scientific interest for further research to recognize vitamin D as a reliable, predictive marker for pancreatic lithiasis. After increasing the daily dose of PERT, we observed significantly increased levels of vitamin D, determining the need for strict follow-up of nutritional parameters in this group of patients.

The impaired nutritional status in PEI is further associated with life-threatening cardiovascular complications. Most consensuses assess CVR using models for predicting the 10-year risk of developing cardiovascular disease, such as the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) and SCORE (Systemic COronary Risk Estimation). The aim is to include individuals without symptoms or cardiovascular diseases, as the combination of different risk factors can lead to an unexpectedly high overall CVR. These predictive models have become the first-line tools for assessing CVR in clinical practice. Based on these, patients are classified as having low, moderate, and high CVR and are recommended for lifestyle changes, additional cardiovascular risk assessment, or drug therapy, as well as more intensive preventive interventions. To date, research on the relationship between cardiac and pancreatic diseases has received insufficient attention, and their role in pathogenesis is not fully understood. Current evidence suggests a link between PEI and malnutrition in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Chronic hypoxia of pancreatic tissue and subsequent damage are likely to contribute to cachexia in patients with cardiovascular diseases [20]. There are a number of overlapping factors between cardiac and pancreatic diseases. Endothelial dysfunction, proinflammatory cytokines, atherosclerosis, and activated procoagulant factors also play a role [21]. Alcohol abuse leads to the activation of the immune system, which in turn increases the risk of developing atherosclerosis [22]. Infiltration of macrophages and T-lymphocytes into the pancreas is well established, and they can recruit additional inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and interleukin-1 [23]. High levels are associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction, recurrent myocardial infarction, and death [24]. De la Iglesia et al. investigated factors associated with increased mortality in patients with chronic pancreatitis [25]. During follow-up, cardiovascular events were verified in 10.5% of patients. Multivariable analyses demonstrated the significance of the association of cardiovascular events with smoking, PEI, PEI and diabetes mellitus, and alcohol consumption. The data from the study demonstrated significantly reduced levels of nutritional markers in patients with a cardiovascular event. Survival was significantly reduced in patients with chronic pancreatitis and PEI with or without diabetes mellitus [25]. Patients with diabetes mellitus and pancreatitis on insulin therapy were at an increased risk of developing severe hypoglycemia and mortality compared to patients with diabetes mellitus on insulin therapy [26]. Sung et al. further found that the hazard ratio for acute atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease associated with chronic pancreatitis was 3.42 (95% CI 1.69–6.94). Metformin use reduced the risk of acute atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with pancreatitis [27]. Desai et al. demonstrated that patients with chronic pancreatitis were at an increased risk of ischemic heart disease (aOR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.03–1.12) acute coronary syndrome (aOR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.04–1.30) and cardiac arrest (aOR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.01–1.53), cerebrovascular accident (aOR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.05–1.20), and peripheral arterial disease (aOR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.1–1.24). Ischemic heart disease in chronic pancreatitis on the background of aspirin, statins, or insulin was associated with worse survival in terms of all-cause mortality [28]. Patients with chronic pancreatitis experienced myocardial infarction significantly more often than controls: 14.22% versus 3.23%. Multivariate analysis of predictors of myocardial infarction in this patient population revealed significance for arterial hypertension, chronic kidney disease, age over 65 years, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, alcohol intake, smoking, the Caucasian race, and the male gender (p < 0.0001) [29]. In the present study, we observed a significant discrepancy in the distribution of patients according to the severity of cardiovascular disease in the two systems used (FRS and SCORE Risk Chart). The majority of patients had moderate risk (44.29%) by the SCORE Risk Chart and low risk (45.71%) by FRS. This could be due to the additional consideration of HDL levels and hypertension treatment in the FRS. Both systems correlated significantly with gender and age. The SCORE Risk Chart correlated with the severity of chronic pancreatitis, without finding a significant relationship with the severity of morphological changes according to Cambridge.

The active form of vitamin D, namely 1,25(OH)2D, is a factor for normal regulation and expression of genes, which are needed for calcium and metabolic homeostasis, immune and inflammation regulation, anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic activities in the pancreas, cell growth and differentiation, as well as for tumour suppression [6]. Experimental studies show that vitamin D has various cardiovascular effects, such as antihypertrophic properties, inhibition of cardiomyocyte proliferation, stimulation of smooth muscle cells proliferation, expression of endothelial growth factor, inhibition of natriuretic peptide emission, and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [30,31,32,33]. Vitamin D can influence major cardiovascular risk factors such as arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and lipids metabolism [32,34]. Studies demonstrate vitamin D as a co-factor for atherosclerosis, stroke, coronary artery disease, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and arrhythmia [11,32]. In our cohort, the SCORE Risk Chart and FRS correlated lower vitamin D levels with increased CVR, verifying the potential role of vitamin D deficiency in cardiovascular risk development. However, due to the cohort’s number, we need to interpret the significance cautiously.

We investigated pulse wave velocity as an additional objective method for assessing CVR. Arterial stiffness, measured by aortic pulse wave velocity or pulse wave analysis, reflects blood flow in the arteries and the degree of the hardening of the arterial wall, where arterial hardening is a consequence of arteriosclerosis. The risk for patients with high aortic pulse wave velocity is almost twice as high compared to those with lower aortic pulse wave velocity [35,36,37]. In our study, there was a significant correlation between PWV and age, as expected. CVR was not significantly higher in diabetic patients, smokers, and those who reported alcohol consumption. There was no correlation with the scoring systems used. We observed significantly higher aortic pulse wave velocity in patients with severe PEI and severe morphological changes (Cambridge grade IV), demonstrating increased CVR with the progression of chronic pancreatitis.

The increased CVR in the studied patients requires a change in lifestyle, smoking cessation, maintenance of optimal blood sugar levels, and normalization of dyslipidaemia. Men are at higher risk. With the progression of pancreatic diseases, the development of PEI and the deterioration of the pancreatic structure, in addition to optimizing PERT, efforts should be made to accurately determine CVR.

5. Conclusions

Identifying risk factors contributing to the reduction of increased mortality in patients with chronic pancreatitis is essential, as it can reorient therapy towards them with a potential reduction in the burden of mortality. In asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, the persistent deficiency and severe insufficiency of vitamin D in more than half the number of the patients is striking, requiring vitamin D substitution per os. Proper monitoring of patients allows normalization of digestion with a significant reduction in the risk of severe malnutrition complications and improvement of quality of life, which is also the modern goal of PERT. It is necessary to create a multidisciplinary team with an integrated approach in the monitoring of patients with chronic pancreatitis with timely primary and secondary prophylaxis of concomitant endocrinological and cardiovascular complications.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the processes of conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing and visualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the National Science Fund, Bulgaria, Grant № KP-06-H83/5, 2024 (KП-06-H83/5, 2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this research as it did not involve experimental medical studies or procedures.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VD | Vitamin D |

| CP | Chronic pancreatitis |

| SCORE | Systematic COronary Risk Evaluation |

| FRS | Framingham Coronary Heart Disease Risk Score |

| PWV | Pulse Wave Velocity |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| PEI | Pancreatic Exocrine Insufficiency |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| PERT | Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Therapy |

| CVR | Cardiovascular Risk |

| CT/MRCP | Computed Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| aOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

References

- Löhr, J.M.; Dominguez-Munoz, E.; Rosendahl, J.; Besselink, M.; Mayerle, J.; Lerch, M.M.; Haas, S.; Akisik, F.; Kartalis, N.; Iglesias-Garcia, J.; et al. United European Gastroenterology evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of chronic pancreatitis (HaPanEU). United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2017, 5, 153–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gardner, T.B.; Adler, D.G.; Forsmark, C.E.; Sauer, B.G.; Taylor, J.R.; Whitcomb, D.C. ACG Clinical Guideline: Chronic Pancreatitis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 322–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindkvist, B.; Phillips, M.E.; Domínguez-Muñoz, J.E. Clinical, anthropometric and laboratory nutritional markers of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: Prevalence and diagnostic use. Pancreatology 2015, 15, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Muñoz, J.E.; Vujasinovic, M.; de la Iglesia, D.; Cahen, D.; Capurso, G.; Gubergrits, N.; Hegyi, P.; Hungin, P.; Ockenga, J.; Paiella, S.; et al. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: UEG, EPC, EDS, ESPEN, ESPGHAN, ESDO, and ESPCG evidence-based recommendations. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2025, 13, 125–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Moneo, E.; Stigliano, S.; Hedstrom, A.; Kaczka, A.; Malvik, M.; Waldthaler, A.; Maisonneuve, P.; Simon, P.; Capurso, G. Deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins in chronic pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pancreatology 2016, 16, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Hu, C.; Chen, C.J.; Han, Y.P.; Lin, Z.Q.; Deng, L.H.; Xia, Q. Vitamin D and Pancreatitis: A Narrative Review of Current Evidence. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Christakos, S.; Hewison, M.; Gardner, D.G.; Wagner, C.L.; Sergeev, I.N.; Rutten, E.; Pittas, A.G.; Boland, R.; Ferrucci, L.; Bikle, D.D. Vitamin D: Beyond bone. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2013, 1287, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Gao, R. Vitamin D: A Potential Star for Treating Chronic Pancreatitis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 902639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpour, A.; Bereswill, S.; Heimesaat, M.M. Antimicrobial and Immune-Modulatory Effects of Vitamin D Provide Promising Antibiotics-independent Approaches to Tackle Bacterial Infections—Lessons Learnt from a Literature Survey. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 9, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scragg, R.; Jackson, R.; Holdaway, I.M.; Lim, T.; Beaglehole, R. Myocardial infarction is inversely associated with plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 levels: A community-based study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 19, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.B.; Boucher, B.J.; Cheng, R.Z.; Pludowski, P.; Wimalawansa, S.J. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review of Risk Reduction Evidence. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catapano, A.L.; Graham, I.; De Backer, G.; Wiklund, O.; Chapman, M.J.; Drexel, H.; Hoes, A.W.; Jennings, C.S.; Landmesser, U.; Pedersen, T.R.; et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 14, 2999–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piepoli, M.F.; Hoes, A.W.; Agewall, S.; Albus, C.; Brotons, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Cooney, M.T.; Corrà, U.; Cosyns, B.; Deaton, C.; et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) Developed with a special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur. Heart 2016, 1, 2315–2381. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Vasan, R.S.; Pencina, M.J.; Wolf, P.A.; Cobain, M.; Massaro, J.M.; Kannel, W.B. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham heart study. Circulation 2008, 12, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarner, M.; Cotton, P.B. Classification of pancreatitis. Gut 1984, 2, 756–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.; Löhr, J.M.; Singer, M.V. The M-ANNHEIM classification of chronic pancreatitis: Introduction of a unifying classification system based on a review of previous classifications of the disease. J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 42, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.A.; Benedict, F.G. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1918, 4, 370–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlidou, E.; Papadopoulou, S.K.; Seroglou, K.; Giaginis, C. Revised Harris–Benedict Equation: New Human Resting Metabolic Rate Equation. Metabolites 2023, 13, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitcomb, D.C.; Frulloni, L.; Garg, P.; Greer, J.B.; Schneider, A.; Yadav, D.; Shimosegawa, T. Chronic pancreatitis: An international draft consensus proposal for a new mechanistic definition. Pancreatology 2016, 16, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolic, S.; Dugic, A.; Steiner, C.; Tsolakis, A.V.; Haugen Löfman, I.M.; Löhr, J.M.; Vujasinovic, M. Chronic pancreatitis and the heart disease: Still terra incognita? World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 6561–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lupu, F.; Esmon, C.T. Inflammation, innate immunity and blood coagulation. Hamostaseologie 2010, 30, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, G.K. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1685–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz–Winnenthal, H.; Pietsch, D.H.K.; Schimmack, S.; Bonertz, A.; Udonta, F.; Ge, Y.; Galindo, L.; Specht, S.; Volk, C.; Zgraggen, K.; et al. Chronic pancreatitis is associated with disease-specific regulatory T-cell responses. Gastroenterology 2010, 138, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Rifai, N.; Pfeffer, M.; Sacks, F.; Lepage, S.; Braunwald, E. Elevation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and increased risk of recurrent coronary events after myocardial infarction. Circulation 2000, 101, 2149–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Iglesia, D.; Vallejo-Senra, N.; López-López, A.; Iglesias-Garcia, J.; Lariño-Noia, J.; Nieto-García, L.; Domínguez-Muñoz, J.E. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and cardiovascular risk in patients with chronic pancreatitis: A prospective, longitudinal cohort study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesen, S.S.; Viggers, R.; Drewes, A.M.; Vestergaard, P.; Jensen, M.H. Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, Severe Hypoglycemia, and All-Cause Mortality in Postpancreatitis Diabetes Mellitus Versus Type 2 Diabetes: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, L.C.; Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.S.; Yeh, C.C.; Cherng, Y.G.; Chen, T.L.; Liao, C.C. Risk of acute atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients with acute and chronic pancreatitis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.; Chandan, S.; Ramai, D.; Kaul, V.; Kochhar, G.S. Chronic Pancreatitis and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A US Cohort Propensity-Matched Study. Pancreas 2023, 52, e21–e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.; Abureesh, M.; Alkhayyat, M.; Sadiq, W.; Alshami, M.; Munir, A.B.; Karam, B.; Deeb, L.; Lafferty, J. Prevalence of Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Chronic Pancreatitis. Pancreas 2021, 50, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, A.; Colecchia, L.; Dell’Anna, G.; Scalvini, D.; Mandarino, F.V.; Lisotti, A.; Fuccio, L.; Cecinato, P.; Marasco, G.; Donatelli, G.; et al. Nutritional Management in Chronic Pancreatitis: From Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency to Precision Therapy. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes-Doetsch, H.; Roberts, K.; Newkirk, M.; Parker, A. Fat-soluble vitamin deficiency and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency among adults with chronic pancreatitis: Is routine monitoring necessary for all patients? Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2024, 39, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemstra, T.F.; Lim, K.; Thadhani, R.; Manson, J.E. Vitamin D and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 4033–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, F.; Ghafoor, H.; Hassan, O.F.; Farooqui, K.; Bel Khair, A.O.M.; Shoaib, F. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Diseases: An Update. Cureus 2023, 15, e49734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cosentino, N.; Campodonico, J.; Milazzo, V.; De Metrio, M.; Brambilla, M.; Camera, M.; Marenzi, G. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease: Current evidence and future perspectives. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hametner, B.; Wassertheurer, S.; Mayer, C.C.; Danninger, K.; Binder, R.K.; Weber, T. Aortic Pulse Wave Velocity Predicts Cardiovascular Events and Mortality in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography: A Comparison of Invasive Measurements and Noninvasive Estimates. Hypertension 2021, 77, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilz, N.; Heinz, V.; Ax, T.; Fesseler, L.; Patzak, A.; Bothe, T.L. Pulse Wave Velocity: Methodology, Clinical Applications, and Interplay with Heart Rate Variability. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheong, S.S.; Samah, N.; Roos, N.A.C.; Ugusman, A.; Mohamad, M.S.F.; Beh, B.C.; Zainal, I.A.; Aminuddin, A. Prognostic value of pulse wave velocity for cardiovascular disease risk stratification in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2024, 38, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).