Safety and Efficacy of Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

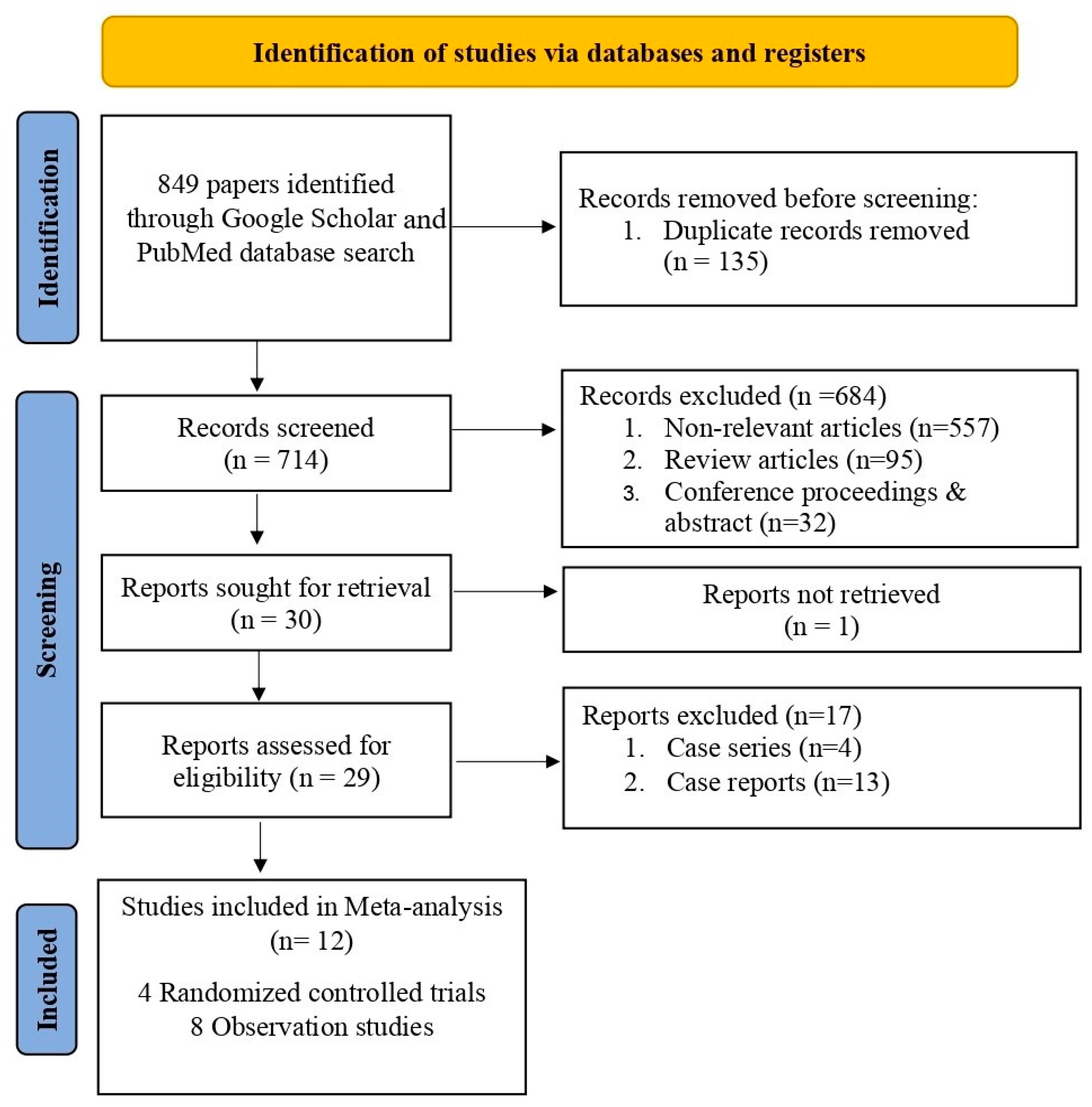

2. Materials and Methods

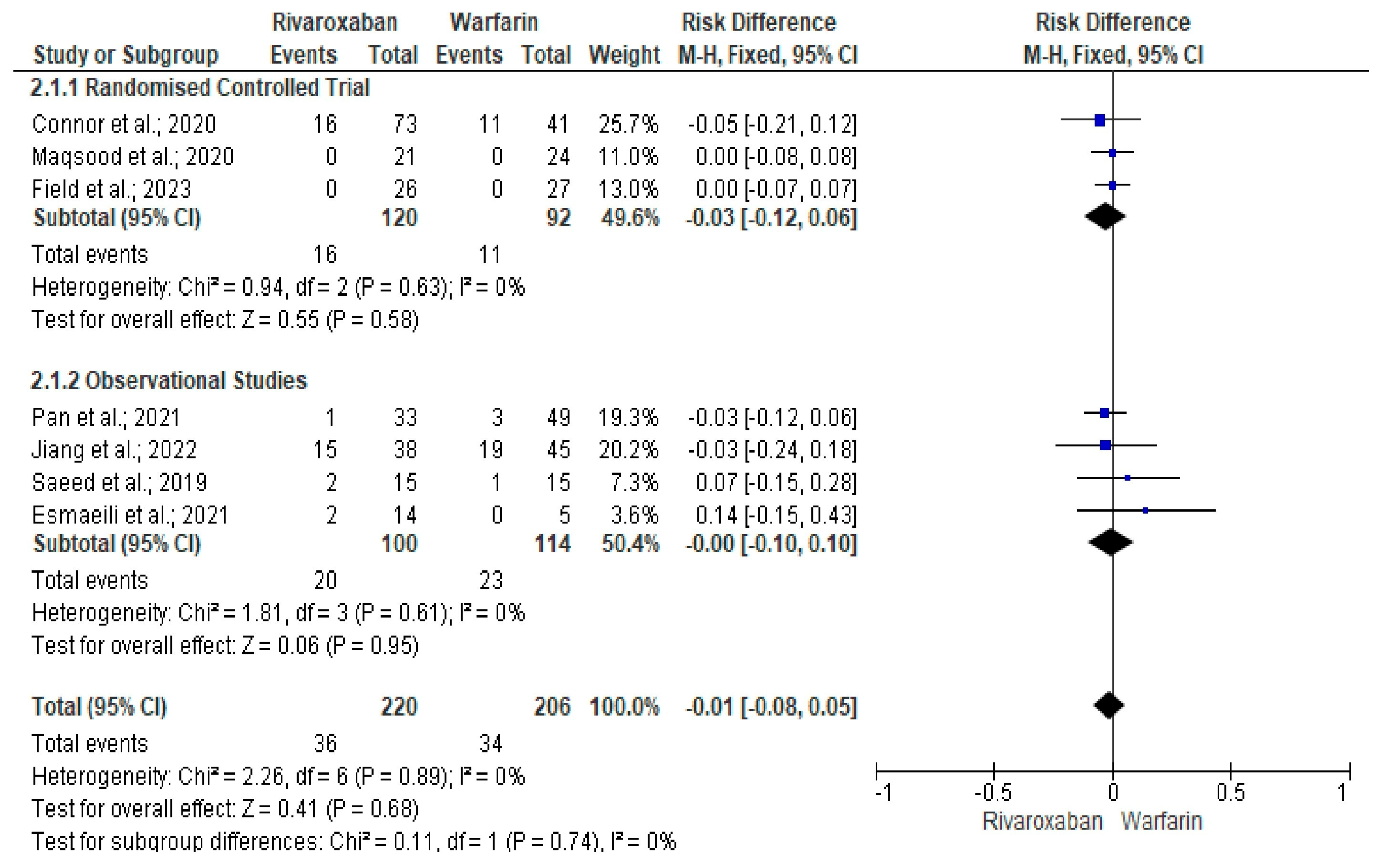

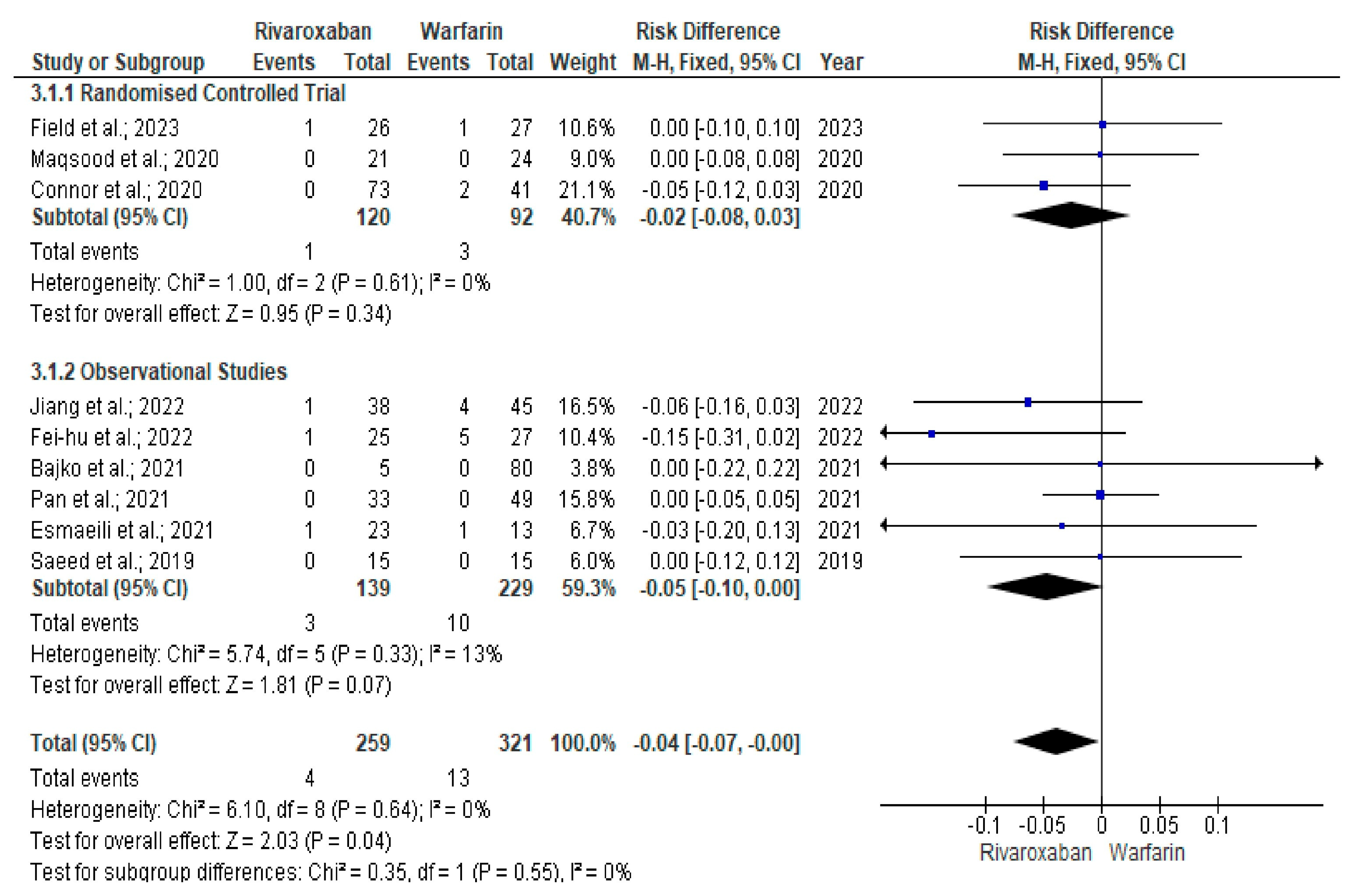

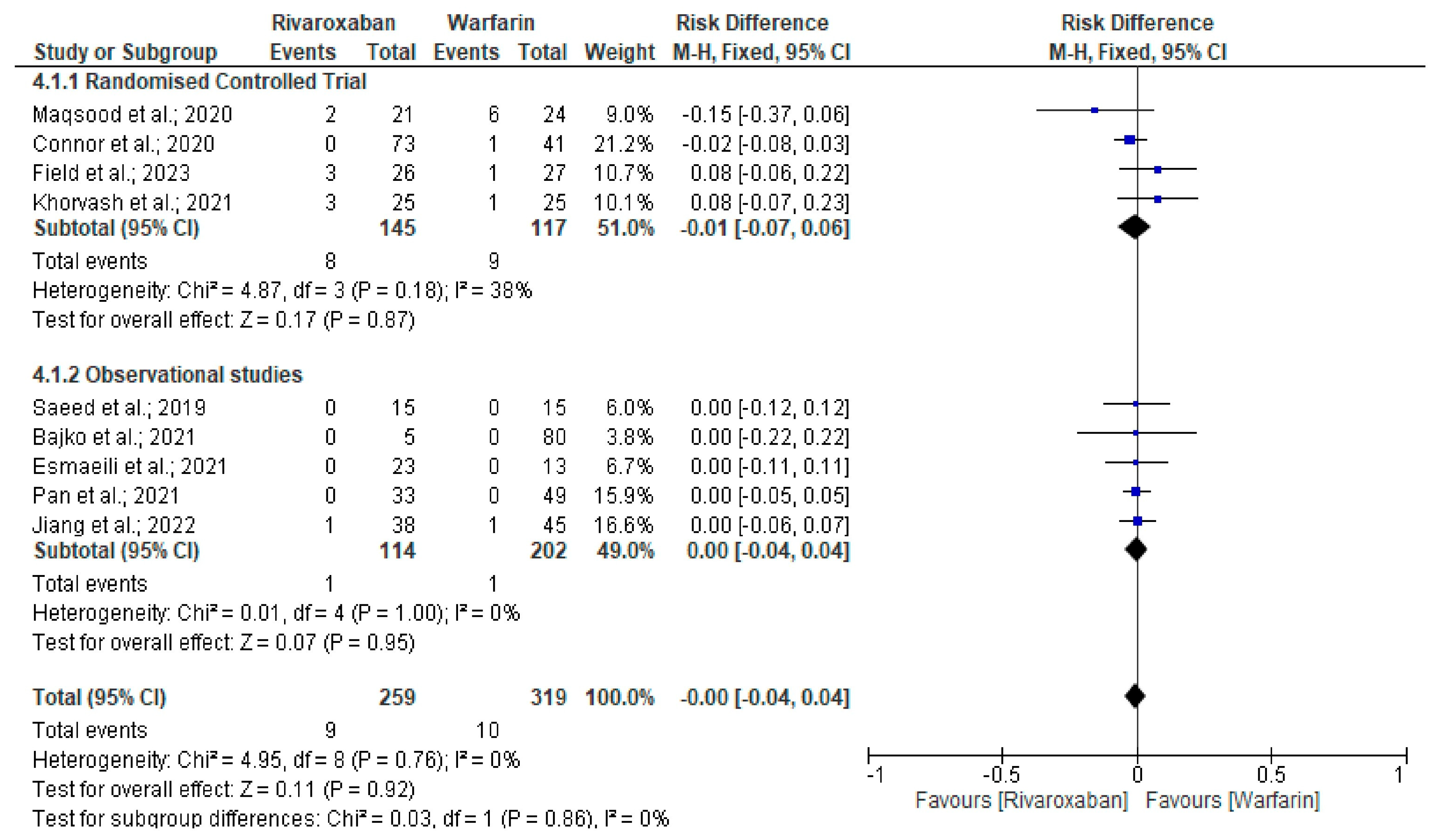

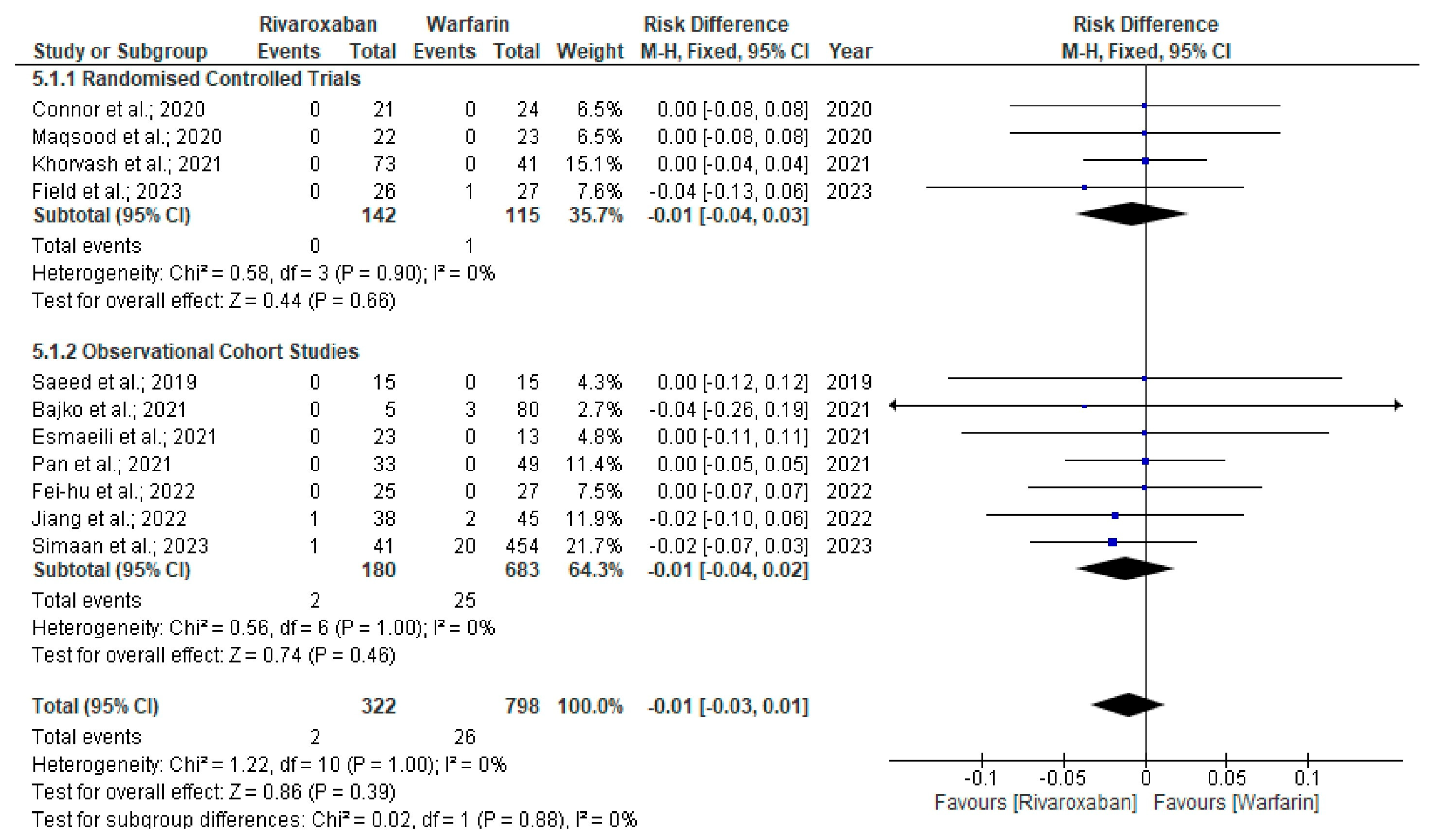

3. Results

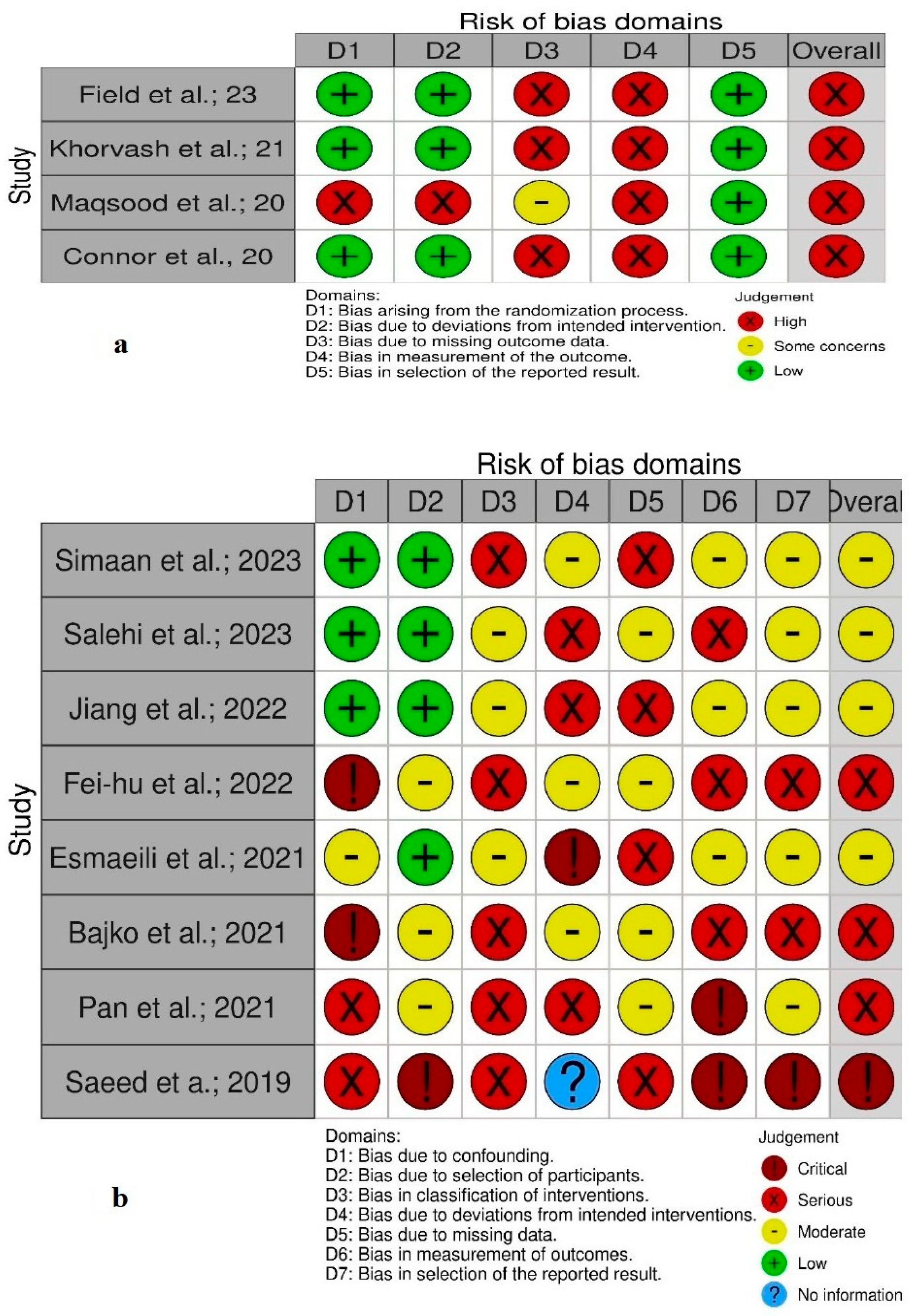

Quality and Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CVT | Cerebral venous thrombosis |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ROB | Risk of bias |

| ROBINS-I | Risk of Bias in Non-Randomised Studies—of Interventions |

References

- Ranjan, R.; Ken-Dror, G.; Martinelli, I.; Grandone, E.; Hiltunen, S.; Lindgren, E.; Margaglione, M.; Duchez, V.L.C.; Triquenot Bagan, A.; Zedde, M.; et al. Age of onset of cerebral venous thrombosis: The BEAST study. Eur. Stroke J. 2023, 8, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J.M.; Zuurbier, S.M.; Aramideh, M.; Stam, J. The incidence of cerebral venous thrombosis: A cross-sectional study. Stroke 2012, 43, 3375–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Ken-Dror, G.; Martinelli, I.; Grandone, E.; Hiltunen, S.; Lindgren, E.; Margaglione, M.; Duchez, V.L.C.; Triquenot Bagan, A.; Zedde, M.; et al. Coma in adult cerebral venous thrombosis: The BEAST study. Eur. J. Neurol. 2024, 31, e16311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, R.; Ken-Dror, G.; Sharma, P.; BEAST Collaborators. Prediction of Long-Term Poor Clinical Outcomes in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis Using Neural Networks Model: The BEAST Study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2024, 17, 2919–2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, J.M.; Bousser, M.G.; Canhão, P.; Coutinho, J.M.; Crassard, I.; Dentali, F.; di Minno, M.; Maino, A.; Martinelli, I.; Masuhr, F.; et al. European Stroke Organization guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis—Endorsed by the European Academy of Neurology. Eur. J. Neurol. 2017, 24, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kernan, W.N.; Ovbiagele, B.; Black, H.R.; Bravata, D.M.; Chimowitz, M.I.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Fang, M.C.; Fisher, M.; Furie, K.L.; Heck, D.V.; et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014, 45, 2160–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tian, X.; Wang, X. Diagnosis and Treatment of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Review. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, P.V.; Kashyap, M.; Dhiran, A.; Yadav, A. Missed Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Diagnostic Challenge. Ann. Neurosci. 2023, 30, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberman, A.L.; Gialdini, G.; Bakradze, E.; Chatterjee, A.; Kamel, H.; Merkler, A.E. Misdiagnosis of Cerebral Vein Thrombosis in the Emergency Department. Stroke 2018, 49, 1504–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otite, F.O.; Vanguru, H.; Anikpezie, N.; Patel, S.D.; Chaturvedi, S. Contemporary Incidence and Burden of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis in Children of the United States. Stroke 2022, 53, e496–e499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristoffersen, E.S.; Harper, C.E.; Vetvik, K.G.; Zarnovicky, S.; Hansen, J.M.; Faiz, K.W. Incidence and Mortality of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis in a Norwegian Population. Stroke 2020, 51, 3023–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.; Shu, L.; Nguyen, T.N.; Siegler, J.E.; Omran, S.S.; Simpkins, A.N.; Heldner, M.; Havenon, A.; Aparicio, H.J.; Abdalkader, M.; et al. ACTION-CVT Study Group. Outcome Prediction in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: The IN-REvASC Score. J. Stroke 2022, 24, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.; Bettencourt, S.; Soares, M.; Ferro, M.; Bettencourt, S.; Soares, M.; Baptista, M.; Marques-Matos, C.; Fragata, I.; Paiva Nunes, A.; et al. Predictors and outcome of deterioration during admission in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis. Eur. Stroke J. 2025, 10, 902–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crader, M.F.; Johns, T.; Arnold, J.K. Warfarin Drug Interactions. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bauersachs, R.; Berkowitz, S.D.; Brenner, B.; Buller, H.R.; Decousus, H.; Gallus, A.S.; Lensing, A.W.; Misselwitz, F.; Prins, M.H.; Raskob, G.E.; et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2499–2510. [Google Scholar]

- Lavalle, C.; Pierucci, N.; Mariani, M.V.; Piro, A.; Borrelli, A.; Grimaldi, M.; Rossillo, A.; Notarstefano, P.; Compagnucci, P.; Dello Russo, A.; et al. Italian Registry in the Setting of Atrial Fibrillation Ablation with Rivaroxaban—IRIS. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2024, 72, 625–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekaj, Y.; Mekaj, A.; Duci, S.; Miftari, E. New oral anticoagulants: Their advantages and disadvantages compared with vitamin K antagonists in the prevention and treatment of patients with thromboembolic events. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2015, 11, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anticoli, S.; Pezzella, F.R.; Scifoni, G.; Ferrari, C.; Pozzessere, C. Treatment of Cerebral Venous Thrombosis with Rivaroxaban. J. Biomedical Sci. 2016, 5, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, V.; Kerolus-Georgi, S.; Moore, K.T. The Pharmacology, Efficacy, and Safety of Rivaroxaban in Renally Impaired Patient Populations. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 61, 1010–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumpston, M.S.; McKenzie, J.E.; Welch, V.A.; Brennan, S.E. Strengthening systematic reviews in public health: Guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd edition. J. Public Health 2022, 44, e588–e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, T.S.; Dizonno, V.; Almekhlafi, M.A.; Bala, F.; Alhabli, I.; Wong, H.; Norena, M.; Villaluna, M.K.; King-Azote, P.; Ratnaweera, N.; et al. Study of Rivaroxaban for Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial Comparing Anticoagulation with Rivaroxaban to Standard-of-Care in Symptomatic Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Stroke 2023, 54, 2724–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorvash, F.; Farajpour-Khanaposhtani, M.J.; Hemasian, H.; Saadatnia, S.M. Evaluation of rivaroxaban versus warfarin for the treatment of cerebral vein thrombosis: A case-control blinded study. Curr. J. Neurol. 2021, 20, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqsood, M.; Imran Hasan Khan, M.; Yameen, M.; Aziz Ahmed, K.; Hussain, N.; Hussain, S. Use of oral rivaroxaban in cerebral venous thrombosis. J. Drug Assess. 2020, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, P.; Sánchez van Kammen, M.; Lensing, A.W.A.; Chalmers, E.; Kállay, K.; Hege, K.; Simioni, P.; Biss, T.; Bajolle, F.; Bonnet, D.; et al. Safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban in pediatric cerebral venous thrombosis (EINSTEIN-Jr CVT). Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 6250–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.Y.; Chen, L.J.; Wu, X.J.; Zhou, G.Q.; Mo, D.C.; Li, X.L.; Liu, L.Y.; Li, J.L.; Luo, M. Efficacy and Safety Assessment of Rivaroxaban for the Treatment of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis in a Chinese Population. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2022, 28, 10760296221144038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, S.; Abolmaali, M.; Aarabi, S.; Motamed, M.R.; Chaibakhsh, S.; Joghataei, M.T.; Mojtahed, M.; Mirzaasgari, Z. Rivaroxaban for the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis. BMC Neurol. 2021, 21, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, D.; Ding, Y.; Ji, X.; Meng, R. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in cerebral venous thrombosis: Insights from a prospective cohort study. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2022, 53, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, F.A.; Ahmad, Z.N. Comparison of warfarin and rivaroxaban in treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Indo. Am. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 6, 8487–8492. [Google Scholar]

- Bajko, Z.; Maier, S.; Motataianu, A.; Filep, R.C.; Stoian, A.; Andone, S.; Balasa, R. Rivaroxaban for the treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis: A single-center experience. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2022, 122, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simaan, N.; Molad, J.; Honig, A.; Filioglo, A.; Peretz, S.; Shbat, F.; Mansor, T.; Abu-Shaheen, W.; Leker, R.R. Factors influencing real-life use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with cerebral sinus and venous thrombosis. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2023, 32, 107223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei-hu, L.; Xue, Y. Clinical Observation of Rivaroxaban and Warfarin in the Treatment of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Acta Neuropharmacol. 2022, 12, 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi Omran, S.; Shu, L.; Chang, A.; Parikh, N.S.; Zubair, A.S.; Simpkins, A.N.; Heldner, M.R.; Hakim, A.; Kasab, S.A.; Nguyen, T.; et al. Timing and Predictors of Recanalization After Anticoagulation in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. J. Stroke 2023, 25, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, R.; Ken-Dror, G.; Sharma, P. Direct oral anticoagulants compared to warfarin in long-term management of cerebral venous thrombosis: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Health Sci. Rep. 2024, 7, e1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Swieten, J.C.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Visser, M.C.; Schouten, H.J.; van Gijn, J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke 1988, 19, 604–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghi, S.; Saldanha, I.J.; Misquith, C.; Zaidat, B.; Shah, A.; Joudi, K.; Persaud, B.; Abdul Khalek, F.; Shu, L.; de Havenon, A.; et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants Versus Vitamin K Antagonists in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stroke 2022, 53, 39579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nepal, G.; Kharel, S.; Bhagat, R.; Ka Shing, Y.; Ariel Coghlan, M.; Poudyal, P.; Ojha, R.; Sunder Shrestha, G. Safety and efficacy of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in cerebral venous thrombosis: A meta-analysis. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2022, 145, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.K.H.; Chen, V.H.; Tan, C.H.; Leow, A.S.T.; Kong, W.Y.; Sia, C.H.; Chew, N.W.S.; Tu, T.M.; Chan, B.P.L.; Yeo, L.L.L.; et al. Comparing the efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants with vitamin K antagonist in cerebral venous thrombosis. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 50, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, G.; Graveline, J.; Yogendrakumar, V.; Shorr, R.; Fergusson, D.A.; Le Gal, G.; Coutinho, J.; Mendonça, M.; Viana-Baptista, M.; Nagel, S.; et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in treatment of cerebral venous thrombosis: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e040212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yao, M.; Liao, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, J. Comparison of novel oral anticoagulants and vitamin k antagonists in patients with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis on efficacy and safety: A systematic review. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 597623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageno, W.; Donadini, M. Breadth of complications of long-term oral anticoagulant care. Hematology Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program 2018, 2018, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, J.A.; Solano, R.; Ruiz-Ribó, M.D.; Ruiz-Gimenez, N.; Prandoni, P.; Kearon, C.; Monreal, M.; Riete Investigators. Fatal bleeding in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: Findings from the RIETE registry. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 1216–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocjan, M.; Kosowski, M.; Mazurkiewicz, M.; Muzyk, P.; Nowakowski, K.; Kawecki, J.; Morawiec, B.; Kawecki, D. Bleeding Complications of Anticoagulation Therapy in Clinical Practice—Epidemiology and Management: Review of the Literature. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearon, C. Balancing risks and benefits of extended anticoagulant therapy for idiopathic venous thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 7, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, F.A.; Kooiman, J.; Huisman, M.V.; Konstantinides, S.; Lankeit, M. Predicting anticoagulant-related bleeding in patients with venous thromboembolism: A clinically oriented review. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yetkin, U.; Karabay, O.; Onol, H. Effects of oral anticoagulation with various INR levels in deep vein thrombosis cases. Curr. Control Trials Cardiovasc. Med. 2004, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Smythe, M.A.; Fanikos, J.; Gulseth, M.P.; Wittkowsky, A.K.; Spinler, S.A.; Dager, W.E.; Nutescu, E.A. Rivaroxaban: Practical considerations for ensuring safety and efficacy. Pharmacotherapy 2013, 33, 1223–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.H.; Liu, Z.H.; Niu, M.H.; Chen, P.; Shi, Y.B.; He, F.; Guo, R. A Comparative Study of the Clinical Benefits of Rivaroxaban and Warfarin in Patients with Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation with High Bleeding Risk. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 803233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.S.; Laliberté, F.; Kharat, A.; Lejeune, D.; Moore, K.T.; Jung, Y.; Lefebvre, P.; Ashton, V. Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Rivaroxaban and Warfarin Among Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation (NVAF) Patients with Obesity and Polypharmacy in the United States (US). Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 3771–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, F.A.; Gore, J.M.; Lessard, D.; Douketis, J.D.; Emery, C.; Goldberg, R.J. Patient outcomes after deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: The Worcester Venous Thromboembolism Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2008, 168, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrni, J.; Husmann, M.; Gretener, S.B.; Keo, H.H. Assessing the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism: A practical approach. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2015, 11, 451–459. [Google Scholar]

- Mulatu, A.; Melaku, T.; Chelkeba, L. Deep Venous Thrombosis Recurrence and Its Predictors at Selected Tertiary Hospitals in Ethiopia: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 26, 1076029620941077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heit, J.A. Predicting the risk of venous thromboembolism recurrence. Am. J. Hematol. 2012, 87, S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, P.; Agius, P.; Ingrand, P.; Ciron, J.; Lamy, M.; Berthomet, A.; Cantagrel, P.; Neau, J.P. Venous Thrombotic Recurrence After Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Long-Term Follow-Up Study. Stroke 2017, 48, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenet, G.; Kirkham, F.; Niederstadt, T.; Heinecke, A.; Saunders, D.; Stoll, M.; Brenner, B.; Bidlingmaier, C.; Heller, C.; Knöfler, R.; et al. European Thromboses Study Group. Risk factors for recurrent venous thromboembolism in the European collaborative paediatric database on cerebral venous thrombosis: A multicentre cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2007, 6, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R.; Ken-Dror, G.; Sharma, P. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of cerebral venous thrombosis: A comprehensive review. Medicine 2023, 102, e36366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Bakradze, E.; Omran, S.S.; Giles, J.; Amar, J.; Henninger, N.; Elnazeir, M.; Liberman, A.; Moncrieffe, K.; Rotblat, J.; et al. Predictors of Recurrent Venous Thrombosis After Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: Analysis of the ACTION-CVT Study. Neurology 2022, 99, e2368–e2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skajaa, N.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Simonsen, C.Z.; Sørensen, H.T.; Adelborg, K. Thromboembolic events, bleeding, and mortality in patients with cerebral venous thrombosis: A nationwide cohort study. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 2070–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharath, S.P.; Arshad, H.; Song, Y.B.; Kirmani, J.F. Long-term Anticoagulation with Apixaban in Patients with Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2023, 29, 10760296221129591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.; Ha, N.B.; Barnes, G.D. Choice and Duration of Anticoagulation for Venous Thromboembolism. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, P.P. Considerations for long-term anticoagulant therapy in patients with venous thromboembolism in the novel oral anticoagulant era. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2016, 12, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moodley, O.; Goubran, H. Should lifelong anticoagulation for unprovoked venous thromboembolism be revisited? Thromb. J. 2015, 13, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shankar Iyer, R.; Tcr, R.; Akhtar, S.; Muthukalathi, K.; Kumar, P.; Muthukumar, K. Is it safe to treat cerebral venous thrombosis with oral rivaroxaban without heparin? A preliminary study from 20 patients. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018, 175, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.C.; Go, A.S.; Chang, Y.; Borowsky, L.H.; Pomernacki, N.K.; Udaltsova, N.; Singer, D.E. A new risk scheme to predict warfarin-associated hemorrhage: The ATRIA (Anticoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation) Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedermann, C.J.; Stockner, I. Warfarin-induced bleeding complications—Clinical presentation and therapeutic options. Thromb. Res. 2008, 122, S13–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalansky, S.; Lynd, L.; Richardson, K.; Ingaszewski, A.; Kerr, C. Risk of warfarin-related bleeding events and supratherapeutic international normalized ratios associated with complementary and alternative medicine: A longitudinal analysis. Pharmacotherapy 2007, 27, 1237–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.R.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Garg, J.; Pan, G.; Singer, D.E.; Hacke, W.; Breithardt, G.; Halperin, J.L.; Hankey, G.J.; Piccini, J.P.; et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Cai, W.; Li, H.; Han, D.; Li, L.; Wang, B. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban versus warfarin in the management of unusual site deep vein thrombosis: A retrospective cohort study. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1419985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales, I.J.; San Agustin, K.; DeAngelo, J.; Campbell, A.M. Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin for Stroke Prevention and Venous Thromboembolism Treatment in Extreme Obesity and High Body Weight. Ann. Pharmacother. 2020, 54, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umurungi, J.; Ferrando, F.; Cilloni, D.; Sivera, P. Cerebral Vein Thrombosis and Direct Oral Anticoagulants: A Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buller, H.R.; Lensing, A.W.; Prins, M.H.; Agnelli, G.; Cohen, A.; Gallus, A.S.; Misselwitz, F.; Raskob, G.; Schellong, S.; Segers, A.; et al. A dose-ranging study evaluating once-daily oral administration of the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban in the treatment of patients with acute symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: The Einstein-DVT Dose-Ranging Study. Blood 2008, 112, 2242–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C.I.; Bunz, T.J.; Turpie, A.G.G. Effectiveness and safety of rivaroxaban versus warfarin for treatment and prevention of recurrence of venous thromboembolism. Thromb. Haemost. 2017, 117, 1841–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; Ashton, V.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, B.; Peterson, E.D. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin treatment among morbidly obese patients with venous thromboembolism: Comparative effectiveness, safety, and costs. Thromb. Res. 2019, 182, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusin, G.; Wypasek, E.; Papuga-Szela, E.; Żuk, J.; Undas, A. Direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis: A single institution’s experience. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2019, 53, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, M.; Asghar, M.; Abbas, S.; Iltaf, S.; Ali, A. An Observational Study to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Rivaroxaban in the Management of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis. Cureus 2021, 13, e13663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, C.G.; Bunz, T.J.; Beyer-Westendorf, J.; Coleman, C.I. Comparative risk of major bleeding with rivaroxaban and warfarin: Population-based cohort study of unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Eur. J. Haematol. 2019, 102, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, A.; Lee, P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: Its causes and consequences. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2000, 53, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanters, S. Fixed- and Random-Effects Models. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2345, 41–65. [Google Scholar]

- Heller, C.; Heinecke, A.; Junker, R.; Knöfler, R.; Kosch, A.; Kurnik, K.; Schobess, R.; von Eckardstein, A.; Sträter, R.; Zieger, B.; et al. Childhood Stroke Study Group. Cerebral venous thrombosis in children: A multifactorial origin. Circulation 2003, 108, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devianne, J.; Legris, N.; Crassard, I.; Bellesme, C.; Bejot, Y.; Guidoux, C.; Pico, F.; Germanaud, D.; Obadia, M.; Rodriguez, D.; et al. Epidemiology, Clinical Features, and Outcome in a Cohort of Adolescents with Cerebral Venous Thrombosis. Neurology 2021, 97, e1920–e1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafaei, H.; Ghojazadeh, M.; Hajebrahimi, S. Fixed-effect Versus Random-effects Models for Meta-analyses: Fixed-effect Models. Eur. Urol. Focus 2023, 9, 691–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettori, J.R.; Norvell, D.C.; Chapman, J.R. Fixed-Effect vs Random-Effects Models for Meta-Analysis: 3 Points to Consider. Global Spine J. 2022, 12, 1624–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.J.; Lin, E.X.; Shi, J.D.; Yang, K.; Hu, Z.L.; Zeng, X.T.; Tong, T.J. Meta-analysis with zero-event studies: A comparative study with application to COVID-19 data. Mil. Med. Res. 2021, 8, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sl Number | Authors, Year | Study Design | Location | Sample Size (N) | Age (years) | Female (%) | Treatment Duration (months) | Follow-Up (months) | Recurrence (n/N) | New ICH (n/N) | Clinically Relevant Bleeding (n/N) | Non-Recanalisation (n/N) | mRS 0–2 (n/N) | Mortality (n/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomised Controlled Trial | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | Field et al.; [22] | RCTs | Canada | Rivaroxaban (26) | 48.5 (37–64) | 69.2% | 6–12 | 6–12 | 1/26 | 2/26 | 3/26 | 0/26 | 22/23 | 0/26 |

| Warfarin (27) | 48 (39–58) | 63.0% | 6–12 | 6–12 | 1/27 | 1/27 | 1/27 | 0/27 | 23/25 | 1/27 | ||||

| 2 | Khorvash et al.; [23] | RCTs | Iran | Rivaroxaban (25) | 41.20 ± 11.4 | 68% | 6 | 6 | - | 1/24 | 3/25 | - | 22/22 | 0/22 |

| Warfarin (25) | 40.76 ± 11.7 | 76% | 6 | 6 | - | 0/25 | 1/25 | - | 23/23 | 0/23 | ||||

| 3 | Maqsood et al.; [24] | RCTs | Pakistan | Rivaroxaban (21) | 26 (15–36) | 86% | 3–12 | 12 | 0/21 | 0/21 | 2/21 | 0/21 | - | 0/21 |

| Warfarin (24) | 27 (15–45) | 79% | 3–12 | 12 | 0/24 | 0/24 | 6/24 | 0/24 | - | 0/24 | ||||

| 4 | Connor et al.; [25] | RCTs | Multi-centre | Rivaroxaban (73) | ≤17 | 37% | 3 | 3 | 0/73 | 0/73 | 0/73 | 16/73 | - | 0/73 |

| Warfarin (41) | ≤17 | 44% | 3 | 3 | 2/41 | 1/41 | 1/41 | 11/41 | - | 0/41 | ||||

| Observational Studies | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | Jiang et al.; [26] | Retrospective observational | China | Rivaroxaban (38) | 38.9 ± 14.2 | 44.7% | 3–12 | 3 | 1/38 | 0/38 | 1/38 | 15/38 | 38/38 | 1/38 |

| Warfarin (45) | 40.9 ± 13.2 | 33.3% | 3–7 | 3 | 4/45 | 1/45 | 1/45 | 19/45 | 45/45 | 2/45 | ||||

| 6 | Esmaeili et al.; [27] | Retrospective observational | Iran | Rivaroxaban (23) | 36 ± 11.2 | 73.1% | 12 | 12 | 1/23 | 0/23 | 0/23 | 2/14 | 22/22 | 0/23 |

| Warfarin (13) | 34 ± 11.2 | 92.3% | 12 | 12 | 1/13 | 0/13 | 0/13 | 0/5 | 10/10 | 0/13 | ||||

| 7 | Pan et al.; [28] | Prospective observational | China | Rivaroxaban (33) | 37.1 ± 13.8 | 66.7% | 6 | 6 | 0/33 | 0/33 | 0/33 | 1/33 | 33/33 | 0/33 |

| Warfarin (49) | 34.1 ± 14.0 | 67.4% | 6 | 6 | 0/49 | 0/49 | 0/49 | 3/49 | 48/49 | 0/49 | ||||

| 8 | Saeed et al.; [29] | Retrospective observational | Pakistan | Rivaroxaban (15) | 31.47 ± 9.2 | 66.7% | 6 | 6 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 2/15 | 15/15 | 0/15 |

| Warfarin (15) | 35.87 ± 10.8 | 73.3% | 6 | 6 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | 1/15 | 15/15 | 0/15 | ||||

| 9 | Bajko et al.; [30] | Retrospective observational | Romania | Rivaroxaban (5) | 54.2 ± 18.7 | 40% | 13.2 | 13.2 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | - | 4/5 | 0/5 |

| Warfarin (80) | 40.3 ± 15.2 | 67.5% | 6 | 6 | 0/80 | 0/80 | 0/80 | - | 77/80 | 3/80 | ||||

| 10 | Simaan et al.; [31] | Prospective | Israel | DOAC (41) | 45.6 ± 19.8 | 66% | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 32/41 | 1/41 |

| Warfarin (454) | 41.3 ± 18.3 | 67% | 3 | 3 | - | - | - | - | 359/454 | 20/454 | ||||

| 11 | Fei-hu et al.; [32] | Prospective observational | China | Rivaroxaban (25) | 35.80 ± 3.15 | 56% | 3 | - | 1/25 | 0/25 | 1/25 | - | - | 0/25 |

| Warfarin (27) | 34.37 ± 3.02 | 55.6% | 3 | - | 5/27 | 1/27 | 8/27 | - | - | 0/27 | ||||

| 12 | Salehi et al.; [33] | Retrospective observational | USA | Rivaroxaban (6) | 46.1 ± 17.4 | 67.4% | 6 | 6 | - | - | - | 6/65 | - | - |

| Warfarin (43) | 44.3 ± 16.1 | 63.0% | 6 | 6 | - | - | - | 43/65 | - | - | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ranjan, R.; Ken-Dror, G. Safety and Efficacy of Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Neurol. Int. 2025, 17, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17110183

Ranjan R, Ken-Dror G. Safety and Efficacy of Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Neurology International. 2025; 17(11):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17110183

Chicago/Turabian StyleRanjan, Redoy, and Gie Ken-Dror. 2025. "Safety and Efficacy of Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis" Neurology International 17, no. 11: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17110183

APA StyleRanjan, R., & Ken-Dror, G. (2025). Safety and Efficacy of Rivaroxaban Versus Warfarin in Cerebral Venous Thrombosis: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Neurology International, 17(11), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint17110183