Abstract

The reliability of the Medium-Voltage Direct-Current (MVDC) power supply system is crucial for train operation, as it powers control, communication, and other critical onboard systems. Accurately locating insulation faults within this system can significantly reduce troubleshooting difficulty and prevent major operational losses. This study addresses a key challenge in applying Time-Domain Reflectometry (TDR) for fault location in single-core cables of IT systems: the incident-end impedance mismatch caused by the variable characteristic impedance of such cables, which fluctuates with installation distance from a ground plane. First, the mechanism through which this mismatch attenuates the primary fault reflection and generates secondary reflections is theoretically modeled. A resistive-capacitive (RC) coupling network is then designed to achieve bidirectional impedance matching between the test equipment and the cable under test while maintaining essential DC isolation. Simulation and experimental results demonstrate that the proposed network effectively mitigates the mismatch issue. In experiments, it increased the proportion of the primary reflected wave entering the receiver by over 30 percentage points and suppressed the secondary reflection by approximately 80%. These improvements enhance waveform clarity and signal strength, directly leading to more accurate fault location. The proposed solution, validated in a railway context, also holds significant potential for improving insulation fault diagnosis in analogous high-voltage cable applications, such as electric vehicle powertrains.

1. Introduction

During train operation, factors such as vibration, temperature, and humidity fluctuations easily degrade the insulation performance of the MVDC power supply system, leading to insulation layer aging, damage, grounding leakage, and other faults [1]. The train’s MVDC power supply system adopts floating-ground wiring [2], where neither the positive nor negative bus is grounded. This design ensures that a single-point grounding fault does not directly disrupt normal train operation. However, multi-point grounding faults may cause short circuits and equipment damage or even threaten operational safety [2,3].

Currently, the primary method for troubleshooting train insulation faults is the “line-disconnection method,” which involves disconnecting DC feeder circuits one by one to observe changes in grounding phenomena and identify the faulty branch. This method consumes substantial manpower and material resources. Therefore, developing efficient and convenient insulation fault localization methods for MVDC power supply systems is crucial for enhancing the reliability of train power systems.

In the aviation industry, reflection-based methods are widely used for insulation fault localization [4,5]. Specifically, Spread Spectrum Time-Domain Reflectometry (SSTDR)—based on Time-Domain Reflectometry (TDR)—enables online monitoring [6]. It requires no shutdown or cable disassembly during detection and can identify flashover faults occurring during operation [7], significantly improving detection speed, convenience, and reliability [8,9]. Liu et al. [10] used the QLA1114222-U cable as the research object, constructed an SSTDR signal model, and revealed that incident signal leakage and equipment-cable impedance mismatch constrain detection performance. They proposed an improved scheme integrating a transceiver isolation circuit and a notch filter, achieving fault detection over 68–210 m at different frequencies. Hua et al. [9] further developed Enhanced SSTDR (ESSTDR) by integrating an interference cancelation algorithm and Smoothed Pseudo-Wigner–Ville Distribution (SPWVD). This solves the issues of low-frequency interference and weak defect reflection signals in traditional SSTDR, enabling the online defect identification of aviation shielded twisted pairs and single-core cables with a localization error of less than 3%. Chen et al. [11] focused on shielded twisted pairs for RS-485 and ARINC429 buses, controlling the SSTDR signal amplitude (≤0.5 V) and center frequency (62.5 MHz) to ensure a data transmission bit error rate as low as 10−4 while achieving a fault localization error of less than 2%.

In impedance measurements, SSTDR exhibits unique advantages due to the strong autocorrelation and wide frequency spectrum of pseudo-noise sequences [12,13]. Benoit et al. [14,15] used RG58 coaxial cable as a transmission line model to verify SSTDR’s broadband impedance measurement capability (from near-DC to gigahertz frequencies). Optimizing the PN code length and signal frequency reduced the impedance measurement error to less than 1%.

Notably, the cables adapted for SSTDR in existing studies have stable characteristic impedance. However, single-core cables—commonly used in IT systems—differ significantly: their characteristic impedance is not constant due to the influence of adjacent conductors during installation [16].

To bridge this gap, this study first analyzes how the distance between single-core cables and an adjacent conducting plane affects their characteristic impedance and the detrimental impact of this impedance inconsistency on the detection equipment. Subsequently, a dedicated RC coupling network is designed to mitigate mismatch effects and improve reflected signal integrity. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 details the theoretical analysis of single-core cable parameters and the fault location principle. Section 3 analyzes the secondary reflection caused by incident-end impedance mismatch and introduces the coupling network design. Section 4 and Section 5 present the simulation and experimental validation, respectively. Section 6 discusses the results and limitations, followed by Section 7 discussing the conclusions.

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Single-Core Cable and Its Distributed Parameters

The cable used in the DC medium voltage system of the train is a single-core cable, and the reference standard is EN 50264-3-1 0.6/1 kV [17]. It offers advantages such as a large contact area at terminals (reducing poor contact due to oxidation or loosening) and good heat dissipation, making it suitable for high-power applications.

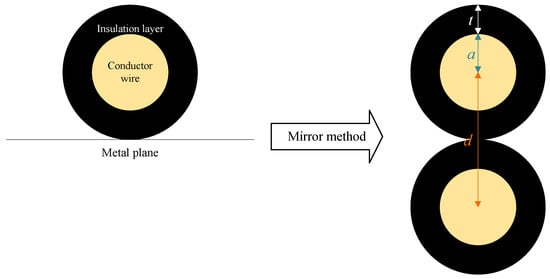

In the train’s undercarriage, the cable runs above a metal plane (chassis), which can be approximated as an ideal conductor. Using the method of images, the influence of this plane can be modeled by placing a mirror image of the cable symmetrically below it. Thus, calculating the distributed parameters of the single-core cable relative to the metal plane transforms into solving the parameters for a two-wire transmission line model, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mirror image method to solve the distribution parameters of single-core wire.

The parameters are as follows: a—the radius of the wire core; d—twice the distance between the wire core and the metal plane; and t—the thickness of the insulation layer.

According to the distributed parameter formulas for the two-wire model [7], the per-unit-length parameters for the single-core cable can be derived as shown in Equations (1) to (4). The variables are defined as follows: —inductance per unit length (H/m); —capacitance per unit length (F/m); —resistance per unit length (Ω/m); —conductance per unit length (S/m); —permeability of the insulation; and —real and imaginary parts of the complex permittivity of the insulation; —the surface resistance of the conductor; ω—angular frequency.

Because , can be approximated as follows:

From the per-unit-length equivalent circuit model of a transmission line, the characteristic impedance Z can be expressed as follows [13]:

The analysis of Equations (1)–(6) reveals that the characteristic impedance Z of the single-core cable relative to the metal plane is related to the physical distance D (). Z increases with increasing D. In practical engineering, maintaining a consistent distance D is challenging.

To analyze the relationship between characteristic impedance and distance, the CRCC29 EMU cable from a manufacturer was selected as the subject. Its main parameters are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The main parameters of the cable.

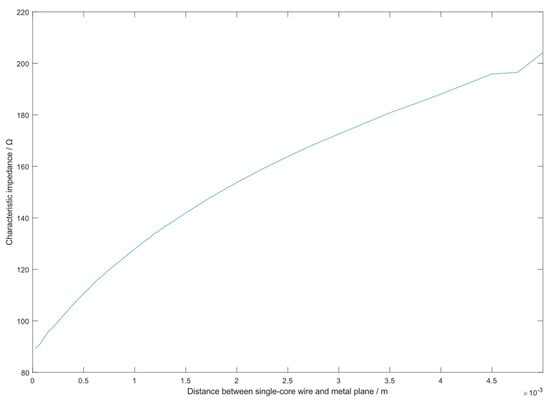

Based on the parameters in Table 1, a model was built in Ansys Q3D Extractor. The distance D between the cable and the metal plane was swept. After extracting the distributed parameters (R, L, C, G), the data were imported into MATLAB to calculate the characteristic impedance as a function of D, as shown in Figure 2. The simulation in Q3D was performed under electrostatic and magnetostatic assumptions at a frequency of 10 MHz to extract the dominant per-unit-length capacitance and inductance, which are relatively frequency-independent for this geometry in the relevant spectrum.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the characteristic impedance of the cable and its distance from the metal plane (ground).

As shown in Figure 2, the characteristic impedance of the single-core cable is positively correlated with its distance from the metal plane, and the variation is substantial. When the cable is in close contact with the metal plane (D ≈ 0 mm), its characteristic impedance is approximately 90 Ω. When the cable is lifted 5 mm away from the plane, the characteristic impedance increases to about 200 Ω. This significant variation under common installation conditions is the root cause of the impedance mismatch problem at the incident end when using the detection equipment with a fixed (typically 50 Ω) output impedance.

2.2. Fault Localization Principle

Impedance matching implies that the load impedance connected to both ends of a transmission line matches the line’s characteristic impedance. Under this condition, signal transmission achieves maximum power transfer. A flawless cable has a uniform geometric structure, resulting in a constant characteristic impedance and perfect matching.

When a cable is damaged somewhere, it may cause the characteristic impedance of the cable to change, resulting in a mismatch between the characteristic impedance of the damaged cable and the healthy cable. The incident traveling wave signal in the cable will be reflected at the impedance mismatch [18]: if the impedance at the damage is larger than the normal characteristic impedance, the reflection coefficient is positive, and the reflected wave has the same polarity as the incident wave; if the impedance at the damage is smaller than the normal characteristic impedance, the reflection coefficient is negative [19,20], and the reflected wave is opposite to the incident wave. The calculation formula of the reflection coefficient is as follows:

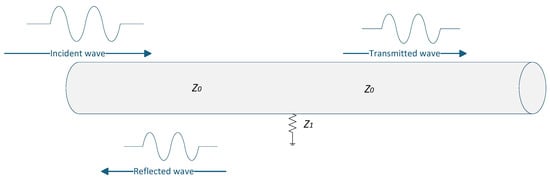

As shown in Figure 3, when an insulation fault occurs in the single-core cable, it can be modeled by introducing a fault resistance to the ground at the fault location. The impedance at the fault point becomes the parallel combination of the cable’s characteristic impedance and the fault resistance , resulting in . Since is finite, . Consequently, the incident wave will be reflected at this impedance discontinuity, and the reflection coefficient for this specific fault scenario is derived from Equation (7) by substituting :

Figure 3.

Principle of the detection method.

According to Equation (8), when an insulation fault occurs in a single-core cable, there will be a mismatch in the cable impedance, and there will be a corresponding reflected wave in the detection waveform. The more serious the insulation fault is, the smaller the grounding resistance Z1 is, and the closer the reflection coefficient Γ is to −1. In the detection waveform, when there is an insulation fault in the cable, there is a reflected wave in the detection waveform that is opposite to the polarity of the incident wave, and the more serious the insulation fault is, the greater the amplitude of the reflected wave is.

3. Analysis of Secondary Reflection Caused by Incident-End Impedance Mismatch

3.1. Impact of Incident-End Impedance Mismatch

As shown in Figure 2, the characteristic impedance of a single-core cable relative to ground is highly sensitive to its installation distance from the metal plane (chassis) and is consistently higher than that of standard coaxial lines (typically 50 Ω). Consequently, fault detection in such cables often encounters significant impedance mismatch at the signal injection end.

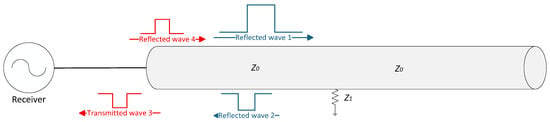

This mismatch profoundly affects the behavior of reflected waves within the system. The mechanism is illustrated in Figure 4. The initial incident wave (Wave 1) propagates along the cable. Upon encountering a fault (an insulation fault to ground with resistance ), a primary reflected wave (Wave 2) is generated. According to Equation (8), for an insulation fault where , Wave 2 has a polarity opposite to that of Wave 1.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of primary and secondary reflections due to incident-end impedance mismatch.

Wave 2 travels back toward the incident end. However, when it reaches the interface between the cable (characteristic impedance ) and the detection equipment (input impedance ), a second impedance discontinuity exists if . For typical test equipment where (often 50 Ω) is less than the variable (90–200 Ω), part of Wave 2 is transmitted into the receiver (Wave 3), while another part is reflected back into the cable (Wave 4). The polarity of Wave 4 is determined by the sign of the reflection coefficient at the incident-end interface, . Since , is negative, resulting in Wave 4 having a polarity opposite to Wave 2 (and thus the same as the original incident Wave 1). Wave 4 then propagates toward the fault, creating a secondary reflection process that further complicates the waveform.

The blue arrows represent the initial incident wave and its direct reflections. The red arrows represent waves generated or affected by the mismatch at the incident end: Wave 1: the incident wave; Wave 2: the primary reflection from the fault; Wave 3: the portion of Wave 2 transmitted into the receiver; and Wave 4: the portion of Wave 2 reflected back into the cable at the mismatched interface.

The practical consequence of this phenomenon is a systematic error in fault assessments. The signal actually captured by the receiver (Wave 3) is an attenuated version of the true primary reflection (Wave 2) because . However, the incident wave measured by the receiver (which is essentially Wave 1 sourced locally) does not experience this same attenuation. Therefore, the calculated reflection coefficient from the received waveform, given by , will be smaller in magnitude than the actual fault reflection coefficient (Equation (9)). This leads to an underestimation of the fault severity; specifically, the estimated fault resistance will be larger than the true value.

To quantify this effect, let the incident wave be . For a fault at electrical distance corresponding to time delay , the primary reflected wave is . Here, () is the attenuation factor for the round-trip path to the fault, and is the reflection coefficient at the fault, given by Equation (8):

The transmitted Wave 3 of reflected Wave 2 can be expressed as follows:

The reflected Wave 4 can be expressed as follows:

where is the transmission coefficient of the cable incident on the incident end device, and is the reflection coefficient of the cable incident on the incident end device. The calculation formula is as follows:

Because , the amplitude of the transmitted Wave 3 is smaller than that of the reflected Wave 2, and the amplitude of the reflected wave received by the receiver is smaller than that of the reflected wave in the actual cable.

3.2. Elimination of Incident-End Mismatch

To mitigate the adverse effects of incident-end impedance mismatch, a coupling network must be inserted between the detection equipment and the cable under test. This network must fulfill two primary requirements:

- Provide bidirectional impedance matching: When viewed from the equipment side, the input impedance should approximate the equipment’s nominal output impedance. When viewed from the cable side, the output impedance should adapt to the cable’s variable characteristic impedance.

- Maintain DC isolation: Since the system is a floating IT DC system, the network must block any direct DC path to the ground to avoid creating a ground loop or altering the system’s floating state.

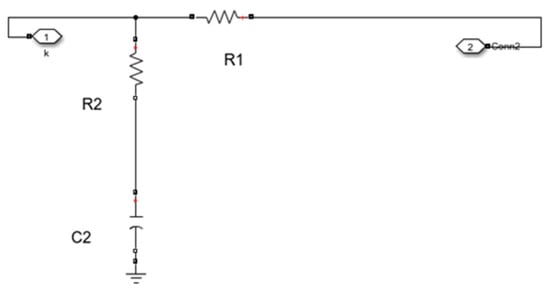

As shown in Figure 5, and are matching resistors. provides DC blocking and participates in AC impedance matching.

Figure 5.

Coupled module.

The values for , , and were chosen based on the target impedance range and the desired frequency of operation (centered around the 10 MHz sinusoidal pulse used in this study).

Resistors and : These are primarily responsible for setting the resistive part of the matching impedance. Their values were selected through analysis and simulation to provide a compromise match across the expected cable impedance range to a 50 Ω source. The chosen values are and .

Capacitor : This component serves two critical functions: (a) It blocks DC, ensuring no direct current path to the ground, which is essential for the floating system. (b) It contributes to the frequency-dependent impedance, helping to tune the network’s matching behavior at the signal frequency. A value of was selected to provide low impedance at 10 MHz while maintaining high impedance at DC.

The input impedance looking into the network from the equipment side () and the output impedance looking into the network from the cable side () can be derived from the circuit structure:

It is important to note that this simple RC network provides effective matching primarily within a limited bandwidth around the design frequency (10 MHz). Its performance will degrade for signal components significantly outside this range. This is a trade-off for simplicity and component count. For applications requiring ultra-wideband signals (like standard SSTDR using PN sequences), a more complex, broadband matching network would be necessary. However, for the targeted application using a narrowband sinusoidal pulse, this RC network offers an effective and practical solution.

4. Simulation Analysis

To validate the theoretical analysis of the secondary reflection caused by incident-end impedance mismatch and the effectiveness of the proposed coupling network, comparative simulations were conducted with and without the coupling module.

4.1. Simulation Model and Parameters

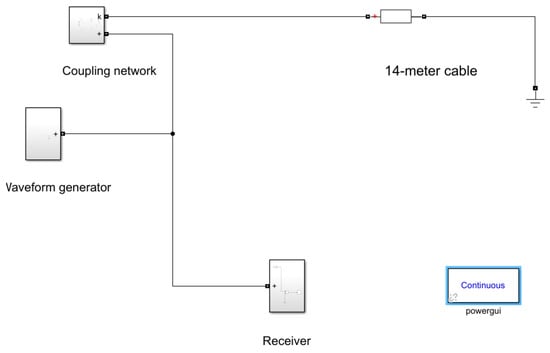

A simulation model was constructed in MATLAB/Simulink 2022b, as shown in Figure 6. The model consists of four main parts:

Figure 6.

Block diagram of the simulation model used for analyzing reflection waveforms.

- Waveform Generator: A custom source block generates a half-wave sinusoidal pulse with a center frequency of 10 MHz and an amplitude of 1 V. This signal shape provides a concise time-domain excitation, minimizes dispersion effects compared to a wideband pulse, and allows the clear observation of reflection polarity. An internal series resistor models the output impedance of a typical signal generator.

- Coupling Network Module: This block implements the RC network shown in Figure 5. It can be bypassed to simulate the scenario without matching.

- Transmission Line Model: A 14 m long, single-core cable is modeled using the “Distributed Parameters Line” block. The per-unit-length parameters (R, L, C, G) are imported from the Q3D extraction results for the CRCC29 cable in close contact with the metal plane. A short cable length is chosen to amplify the reflection effects for clear observation.

- Measurement and Receiver: A high-impedance voltage probe is connected at the junction between the coupling network (or source) and the cable to capture the incident and reflected waveforms.

The components are as follows: (1) a 10 MHz half-wave sinusoidal pulse generator with 50 Ω source impedance; (2) an optional RC coupling network; and (3) a 14 m distributed parameter cable model.

Two fault conditions are simulated at a distance of 14 m from the injection point: an open-circuit fault () and a short-circuit fault to the ground ().

4.2. Simulation Results and Quantitative Analysis

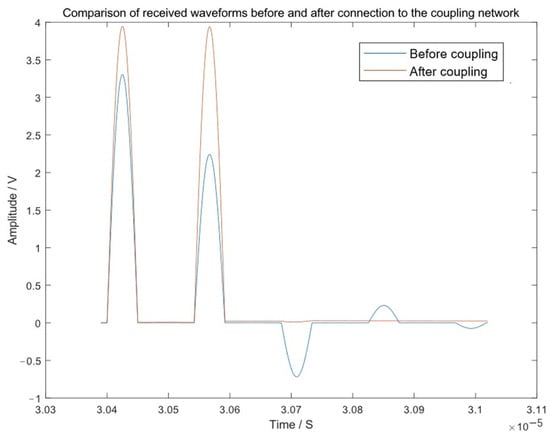

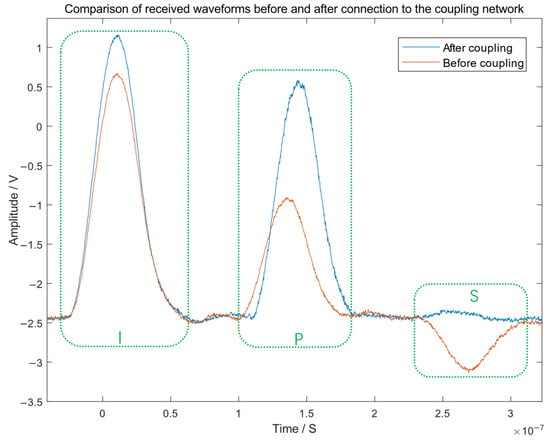

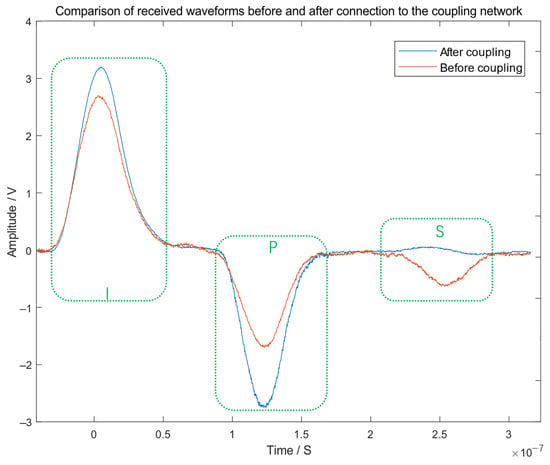

The simulated waveforms for open-circuit and short-circuit faults are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively.

Figure 7.

Simulation results of open-circuit fault.

Figure 8.

Short-circuit fault simulation results.

The blue solid curve represents the case without the coupling network. The red dashed curve represents the case with the coupling network. The primary reflection from the fault and the secondary reflection due to mismatch are indicated. Time is referenced from the start of the incident pulse.

The blue solid curve represents the case without the coupling network. The red dashed curve represents the case with the coupling network.

For a quantitative assessment, the ratio of the primary reflected wave amplitude to the incident wave amplitude is calculated for both cases. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of reflection wave amplitudes from simulation.

The theoretical attenuation of the primary reflection wave solely due to cable loss over the 20 m round trip is approximately 0.5%. The measured primary reflection ratio with the coupling network (≈99.5% and 99.1%) aligns closely with this theoretical limit, confirming near-ideal matching and maximum energy transfer from the fault reflection to the receiver.

More importantly, Table 2 starkly illustrates the problem of incident-end mismatch. Without the coupling network, a significant portion (22.5–23.8%) of the incident wave’s energy is converted into a secondary reflection (Wave 4), which not only represents a loss of signal but also becomes a source of interference that complicates waveform interpretation. The proposed RC network effectively addresses both issues: it restores the primary reflection ratio to over 99%, and simultaneously suppresses the secondary reflection to a negligible level (0.3–0.4%), effectively eliminating it as a meaningful signal component.

These simulation results unequivocally demonstrate that the proposed RC coupling network effectively mitigates the impedance mismatch at the incident end. It restores the amplitude of the primary reflected wave to its theoretical maximum and eliminates the interfering secondary reflections, thereby creating a cleaner and more accurate waveform for fault locations.

5. Experimental Validation

5.1. Experimental Platform Construction

To closely simulate the actual on-train installation environment while maintaining laboratory practicality, a 1:8 scale train model was constructed using 2 mm-thick aluminum alloy plates, representing the vehicle chassis and ground reference. The electrical validity of the scale model for this study is based on the principle that the per-unit-length transmission line parameters (R, L, C, G) and thus the characteristic impedance are primarily determined by the geometry of the cable relative to the ground plane, not the absolute size. Scaling the distance proportionally preserves this geometric relationship, making the model suitable for validating the impedance-matching principle.

In the train’s DC system, single-core cables are routed in wire trays close to the grounded train body. The experimental platform, illustrated in Figure 9, integrates the following key components to replicate this setup:

Figure 9.

Experimental platform.

Test Cable and Environment: A CRCC29 EMU single-core cable was installed parallel to and in close contact with the scaled aluminum alloy model, replicating the proximity to the chassis.

Signal Injection and Acquisition: A Rigol DG912 Pro arbitrary waveform generator was used to output the 10 MHz half-wave sinusoidal incident pulse. The reflected waveforms were acquired by a Rohde and Schwarz RTM3002 digital oscilloscope (equipped with the RTM-B225 module, 500 MHz bandwidth, and operating with an AC 100–240 V/50–60 Hz power supply; manufactured by Rohde and Schwarz, Munich, Germany).

RC Coupling Network: The network designed in Section 3.2 was implemented on a breadboard using discrete components and integrated into the signal path.

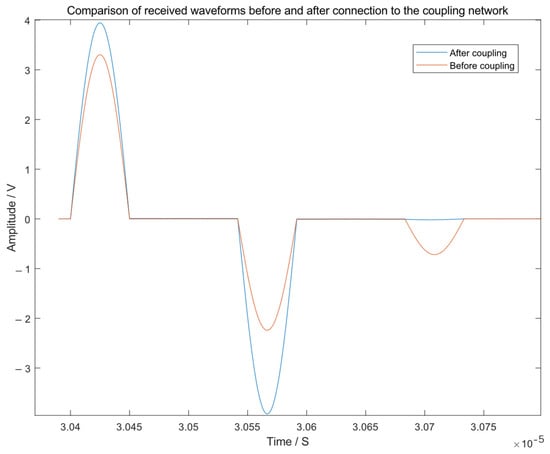

5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

Experimental tests were conducted for open-circuit- (representing a high-impedance discontinuity) and short-circuit-to-ground (representing a severe insulation fault) conditions. The fault was created at a known location on the cable. The waveforms captured by the oscilloscope, with and without the coupling network, are compared in Figure 10 and Figure 11.

Figure 10.

Comparison of open-circuit fault experimental results.

Figure 11.

Comparison of short-circuit fault experimental results.

Experimental waveform comparison for an open-circuit fault: The red solid curve shows the signal received without the coupling network. The blue dashed curve shows the signal with the coupling network in place. The key signal features that are marked are as follows: the incident pulse (I), the primary reflection (P) from the fault, and the secondary reflection (S) caused by incident-end mismatch. The primary reflection (P) for a short-circuit fault exhibits negative polarity.

The results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Quantitative comparison of experimental reflection wave amplitudes.

5.3. Discussion of Experimental Results

- The experimental results strongly support the simulation findings and theoretical analysis.

- Effectiveness of the Coupling Network: As shown in Table 3, the introduction of the RC coupling network increased the captured ratio of the primary reflection wave by over 30 percentage points for both fault types. Concurrently, the amplitude of the secondary reflection wave was reduced by approximately 80% (from ~18% to ~3%). This dual improvement confirms the network’s success in achieving bidirectional impedance matching, thereby enhancing signal integrity.

- Limitations and Discrepancy with Simulation: The primary reflection ratio achieved experimentally (~85%) is lower than the near-perfect ~99% observed in simulation. This discrepancy is attributed to practical non-idealities not fully modeled in simulation, including imperfect component tolerances, parasitic effects in the breadboard implementation, and minor inconsistencies in cable placement relative to the model. The residual secondary reflection (~3%) also stems from these imperfections. These factors represent the main sources of measurement uncertainty in this laboratory setup.

- Practical Significance: Despite these practical imperfections, the improvement is substantial. The amplified primary reflection significantly improves the signal-to-noise ratio for fault detection. Furthermore, the suppressed secondary reflection (reduced to a level lower than the reflection caused by deliberately lifting the cable by 3 mm in our lab) minimizes waveform distortion, leading to more accurate fault location and severity assessment. Future work involving direct onboard testing will aim to validate performance in the presence of these real-world variabilities.

6. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of variable characteristic impedance in single-core cables on TDR-based fault location and proposed a practical mitigation solution. The results from both simulation and experiment lead to several important discussions.

6.1. Root Cause and Novelty of the Addressed Problem

The fundamental issue stems from the unique nature of single-core cables in IT systems (e.g., train MVDC networks). Unlike coaxial or shielded cables with stable, controlled impedance, the characteristic impedance of a single-core cable is highly dependent on its physical installation geometry, specifically its distance from a conductive ground plane (chassis). As shown theoretically (Section 2) and confirmed via simulation (Figure 2), a variation of just a few millimeters can cause the impedance to swing between 90 Ω and 200 Ω. In practical engineering, maintaining precise, uniform spacing is unfeasible. This inherent variability creates a persistent and significant impedance mismatch at the interface with standard 50 Ω test equipment, which has been largely overlooked in the SSTDR/TDR literature focused on stable-impedance cables. Our work explicitly identifies and analyzes this gap.

6.2. Performance and Practical Value of the RC Coupling Network

The designed RC network provides a simple yet effective solution for bidirectional impedance matching. The key performance metrics are quantified in Table 2 and Table 3. Experimentally, the network increased the proportion of the primary reflected wave entering the receiver by over 30 percentage points (from ~53% to ~85%) while simultaneously suppressing the secondary reflection amplitude by approximately 80% (from ~18% to ~3%). This directly translates to two major practical benefits: (1) a stronger, more detectable fault signature (improved SNR), and (2) a cleaner waveform with minimized interference from multiple reflections, leading to more accurate fault distance calculation and severity estimation ().

6.3. Limitations of the Proposed Approach

The solution, while effective for its intended purpose, has certain limitations that should be acknowledged:

Bandwidth Constraint: The simple RC network is optimized for a narrow frequency band around the 10 MHz pulse used here. Its matching performance would degrade for ultra-wideband signals like the PN sequences used in standard SSTDR. For such applications, a more complex broadband matching network would be required.

Sensitivity to Component Tolerances and Parasitics: The main reason for the difference between the experimental results and the simulation results is that the tolerance of resistors and capacitors and the parasitic effects of the breadboard will reduce the matching accuracy. A production version would require careful component selection and PCB layout.

Scope of Validated Fault Scenarios: This study focused on single-point, low-resistance (short) and high-resistance (open) faults to clearly demonstrate the matching principle. The method’s efficacy for intermediate fault resistances, intermittent faults, or multiple concurrent faults requires further investigation, though the underlying principle remains valid.

6.4. Generalizability and Implications for Electric Vehicle Systems

Although validated in a railway context, the core technical challenge—impedance variability due to cable–ground capacitance in floating DC systems—is not unique. A highly relevant parallel application is in electric vehicle (EV) high-voltage (HV) cable harnesses. EV battery packs, motors, and charging systems also use single-core HV cables routed in close proximity to the vehicle’s grounded chassis. Similar impedance mismatch issues are likely to arise during maintenance or onboard diagnostics. The proposed coupling network concept, potentially with component values tuned for typical EV cable geometries and test frequencies, could be directly adapted to improve the accuracy of TDR-based insulation fault location in EVs. This connection aligns the paper’s contributions with the broader scope of vehicular electrification covered by this journal.

7. Conclusions

Accurate fault location in the MVDC power supply cables of trains is crucial for operational safety and maintenance efficiency. This paper addressed a specific but critical challenge in applying TDR-based methods to single-core cables in IT systems: the incident-end impedance mismatch caused by the variable characteristic impedance of such cables.

The main conclusions and contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- Problem Analysis: Through theoretical modeling and parametric simulation, it was quantitatively demonstrated that the characteristic impedance of a single-core cable is highly sensitive to its installation distance from a ground plane (e.g., train chassis), varying from approximately 90 Ω to 200 Ω for a 5 mm change. This variability is the root cause of significant impedance mismatch with standard detection equipment.

- Impact Quantification: The adverse effect of this mismatch was analyzed, showing that it not only attenuates the amplitude of the primary fault reflection captured by the receiver but also generates strong secondary reflections. This combination weakens the fault signal and distorts the waveform, reducing location accuracy.

- Solution Design and Validation: An RC coupling network was designed to provide bidirectional impedance matching between the equipment and the variable-impedance cable while maintaining DC isolation for the floating IT system. Comprehensive simulation and experimental results confirmed its effectiveness. In experiments, the network enhanced the primary reflection ratio by over 30% and suppressed the secondary reflection by approximately 80%, significantly improving waveform clarity and signal strength.

Future work will progress in two directions: (1) technical refinement, including optimizing the coupling network’s bandwidth for broader signal compatibility and testing its performance against a wider range of fault impedances and types, and (2) practical implementation, focusing on integrating the network into a compact, portable prototype device for field testing in railway maintenance depots and exploring its adaptation for diagnostic applications in electric vehicle high-voltage systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.; Methodology, Y.H.; Formal analysis, Y.H.; Investigation, Y.H.; Resources, Q.W. and J.Z.; Data curation, Q.W.; Writing—original draft, Y.H.; Writing—review & editing, Q.W., J.Z. and X.L.; Supervision, Q.W.; Project administration, Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wu, C.Y.; Li, D.D.; Huang, Y.L.; Ming, Z.Y. Research on reconnection process and service life of small-diameter cables for EMUs. Environ. Technol. 2022, 40, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.Q.; Li, X.Q.; Wang, Q.F.; Wang, S. Research on DC110V leakage false alarm faults in CR200J EMUs. Railw. Stand. Des. 2024, 68, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, D.; Qi, F.; Zhou, H.Y.; Zhao, M.; Duan, X.; Huang, Y. Analysis of a typical concentrated burnout fault in 10 kV power cable clusters. Hunan Electr. Power 2020, 40, 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Furse, C.M.; Kafal, M.; Razzaghi, R.; Shin, Y.-J. Fault diagnosis for electrical systems and power networks: A review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.M.; Izykowski, J.; Rosolowski, E. Fault Location on Power Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.D.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.Y.; Jing, T. Online detection of aircraft ARINC bus cable faults based on SSTDR. IEEE Syst. J. 2021, 15, 2482–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.D.; Li, R.P.; Zhang, H.T.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y. Application of augmented spread spectrum time-domain reflectometry for detection and localization of soft faults on a coaxial cable. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 4891–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Research on Online Detection of Power Cable Faults Based on Spread Spectrum Time-Domain Reflectometry. Master’s Thesis, South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, X.; Wang, L.; Chen, H.Z.; Xu, H.; Yin, Z.D. Online identification and localization of aviation cable defects based on enhanced spread spectrum time-domain reflectometry. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.L.; Feng, H.W.; Yang, H.Y. A novel method based on spread-spectrum time-domain reflectometry for improving the distance of cable fault detection. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 9440–9446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.J.; Wang, L.; Yang, S.S.; Chen, H.Z. Research on fault detection and location method of avionic data buses. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 5th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Beijing, China, 27–29 May 2022; pp. 3654–3659. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, M.U.; Deline, C.; Kingston, S.; Jayakumar, N.K.; Benoit, E.; Harley, J.B.; Furse, C.; Scarpulla, M. Detection and localization of disconnections in PV strings using spread-spectrum time-domain reflectometry. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2020, 10, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smail, M.K.; Hacib, T.; Pichon, L.; Loete, F. Detection and location of defects in wiring networks using time-domain reflectometry and neural networks. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2011, 47, 1502–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, E.; Harley, J.B.; Furse, C.M. Evaluation of impedance measurement using spread spectrum time-domain reflectometry. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, D.; Liu, C.; Xiang, C.Q.; Lv, Z.Z. Capacitance reflection wave characteristics and capacitance estimation method based on spread spectrum time-domain reflectometry. J. Electr. Technol. 2025, 40, 1156–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Edun, A.S.; Laflamme, C.; Kingston, S.R.; Furse, C.M.; Scarpulla, M.A.; Harley, J.B. Anomaly detection of disconnects using SSTDR and variational autoencoders. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 3484–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 50264-3-1; Railway Applications—Railway Rolling Stock Power and Control Cables with Special Fire Performance—Part 3-1: Cables with Crosslinked Elastomeric Insulation (Reduced Dimensions)—Single-Core Cables. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2005.

- Auzanneau, F.; Ravot, N.; Incarbone, L. Chaos time domain reflectometry for online defect detection in noisy wired networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 8027–8034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Chang, S.J. A method of fault localization within the blind spot using the hybridization between TDR and wavelet transform. IEEE Sens. J. 2020, 21, 5102–5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, W.; Furse, C. Spread spectrum techniques for measurement of dielectric aging on low-voltage cables for nuclear power plants. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2021, 28, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.