1. Introduction

Facing the severe challenge of global climate change, the 2015 Paris Agreement set a 2 °C warming limit, driving worldwide efforts towards carbon neutrality by mid-century. Despite over 150 nations pledging to achieve carbon neutrality goals, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) reports a 1.55 °C rise in global temperatures, underscoring the urgency for systemic changes in energy, transportation, and industrial sectors [

1,

2]. During this shift towards sustainable development, electric vehicles (EVs), as a pivotal technology for reducing carbon emissions and enhancing energy efficiency, have been thrust to the forefront of this green revolution, emerging as a crucial driver in the realization of global climate objectives [

3]. Supported by their environmental and technological advantages, the EV market has experienced remarkable growth, with nearly 14 million new registrations in 2023, bringing the total number of EVs on the road to 40 million. EVs comprise 18% of all car sales now, up from 14% in 2022 and 2% in 2018, indicating rapid global adoption [

4]. This rapid adoption has intensified competition in the automotive industry, leading to a significant rise in product commoditization and a growing emphasis on service quality as a key differentiation [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Modern consumers, particularly the younger generation, place a greater emphasis on environmental sustainability, intelligence, and personalized experiences [

10]. Their focus extends beyond the inherent quality of the vehicle to encompass aftermarket services and the overall purchasing experience [

11,

12]. This shift necessitates more attention towards service quality and experiential customer journeys in the marketing strategies of EV enterprises [

13]. In this context, understanding what customers seek in terms of service quality has become critical for EV enterprises aiming to gain a competitive edge.

While research on service quality has flourished since the 1980s, the standardization of service delivery remains a significant challenge. A fundamental question underpinning this challenge is the following: what do customers expect from services? Identifying these expectations is crucial for developing effective service quality measurement scales [

14,

15]. Although prior research has explored service quality expectations from both company and customer perspectives, the role of cultural factors in shaping these expectations remains underexplored [

16]. In particular, the impact of one dimension of the “cultural perspective”, namely “masculinity/femininity”, on consumer behavior has not been sufficiently clarified [

17]. This is a field that requires further research accumulation. The purpose of this study is to examine what service customers seek from a cultural perspective, specifically focusing on expectations of service quality in the EV sector. Particular attention will be given to the relationship between the cultural dimension of “masculinity/femininity”, which is controversial in prior research.

The study is structured as follows. In

Section 2, through a review of prior research, the problem setting of this study is clarified. In

Section 3, six hypotheses are formulated to explore how cultural orientation and service provider gender influence expectations for expertise, empathy, and responsiveness in the context of EV dealerships.

Section 4 provides a detailed description of the research methodology, including data collection, measurement instruments, and data analysis methods.

Section 5 concludes the research findings and reveals the impact of cultural factors on electric vehicle consumers’ service quality expectations.

Section 6 presents the insights identified in this study and offers practical guidance for service strategy design and quality improvement in the electric vehicle industry.

2. Literature Review

The rapid growth of the electric vehicle (EV) market has heightened the importance of understanding service quality and customer expectations in this emerging sector. Due to differences in product characteristics, services for electric vehicles (EVs) and traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles differ significantly in areas such as customer education, test-drive experiences, and after-sales services [

18,

19,

20]. However, current research on service marketing in the automotive industry has predominantly focused on after-sales services and charging-related services, with limited attention given to in-store service experiences [

10,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Given these unique characteristics, a deeper assessment of service quality and the study of customer expectations are essential, especially as the EV market continues to rapidly expand [

11,

12,

25,

26].

Research on service quality commenced in the United States in the mid-1980s. The focus of this research has been on the determinants of service quality and how customers evaluate service quality based on their perceptions of service quality [

27,

28,

29]. Early studies by Zeithaml, Berry, and Parasuraman (1993) initially summarized the determinants of service quality into 10 dimensions [

30]. A pivotal contribution to this field is the SERVQUAL model refined by Parasuraman et al. into five core dimensions of service quality: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy [

31,

32]. While SERVQUAL has become a cornerstone for assessing service quality, recent studies highlight its limitations in cross-cultural contexts, thereby emphasizing the adaptations to account for cultural differences [

33]. Cultural differences have emerged as a critical factor in shaping service quality expectations [

16,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]. For instance, in the banking sector, empathy has been identified as a dominant factor in customer satisfaction across diverse cultural settings [

17]. Similarly, in public transportation, researchers have proposed linking “culture” as an additional dimension with the SERVQUAL model to better capture commuters’ unique expectations [

39]. These adaptations underscore the importance of integrating cultural nuances into service quality frameworks.

In the field of service marketing, a seminal study that attempted to address this issue was conducted by Donthu and Yoo in 1998, which examined the cultural influences on expectations of service quality [

16]. In their paper, Donthu et al. sought to clarify whether customers’ expectations of service quality differ across cultures by analyzing culture through four dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, and long-term orientation. They linked customers’ expectations of service quality to culture and distributed questionnaires in four countries, conducting an analysis of variance based on the survey results [

16]. Their findings suggested that customers from cultures characterized by low power distance, individualism, uncertainty avoidance, and short-term orientation have higher overall expectations of service quality. However, we identify two issues with Donthu et al.’s research. The first is their failure to incorporate the dimension of “masculinity/femininity” into their cultural analysis. They considered this dimension unrelated to “expectations of service quality”, but insufficient explanation and justification were provided for this standpoint, which leaves a gap in understanding how gender-related cultural values shape service expectations. The second issue is that while they examine overall expectations of service quality, from a practical business perspective, their findings may be difficult to apply.

Cultural Factor (Masculinity/Femininity) and Service Quality Dimensions

Prior studies have investigated the relationships between cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) and specific SERVQUAL dimensions, revealing mixed findings. In masculine cultures, consumers often prioritize tangibles as symbolic indicators of status, while empathy becomes critical in feminine cultures where interpersonal harmony is valued [

17,

33]. However, the role of the “masculinity/femininity” dimension in shaping service expectations remains unresolved, particularly in contexts where the gender of the service provider is a variable.

The link between cultural dimensions, particularly the masculinity/femininity dimension, and the SERVQUAL model has increasingly become a focal point in subsequent academic research. For example, Furrer et al. (2000) found that masculine customers tend to value tangibles and responsiveness more when served by female providers, rather than expertise [

17]. Similarly, Tsoukatos et al. (2007) observed a negative relationship between masculinity and the dimensions of reliability and assurance in Greece’s insurance industry [

40]. These findings imply that cultural dimension (masculinity/femininity) may influence the salience of certain service quality dimensions in a specific field. However, existing studies have been limited to single-gender service provider contexts, focusing exclusively on either male or female providers. This narrow approach limits our understanding of how cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) operate across different gender contexts. To address this gap, future studies should incorporate gender diversity among service providers to better understand the relationship between cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) and service quality expectations.

Moreover, the role of cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) appears context dependent. Kueh et al. (2007) found no significant relationship between masculinity and service expectations in Malaysia’s fast-food industry, where standardized processes and job competence overshadow gender role effects [

41]. This contrasts with Tsoukatos et al. (2007) findings in Greece’s insurance sector, which highlights a critical context factor: industry type [

40]. Industry characteristics (e.g., technology intensity in EV services vs. labor-centric processes in fast food) may reconfigure how cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) interact with the provider’s gender. For instance, in technology-driven sectors where expertise is paramount (e.g., EV services), masculine customers may prioritize the service provider’s competence (e.g., expertise) over gender—a dynamic potentially inverted in traditional service settings.

This contradiction highlights a critical gap in the literature regarding the impact of the “masculinity/femininity” dimension on service expectations. The exclusion of this dimension in Donthu et al.’s study has indeed sparked significant debate in subsequent research, underscoring the need for further investigation into how cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) shape service quality perceptions [

42].

In summary, while the SERVQUAL model provides a foundational framework for assessing service quality, its application in cross-cultural contexts requires a deeper integration of cultural dimensions, particularly “masculinity/femininity”. Existing research on this dimension is both limited and contradictory, with some studies suggesting it influences the importance of specific service quality dimensions (e.g., tangibles, responsiveness) and others dismissing its relevance altogether. This controversy highlights three critical gaps: (1) the unresolved role of cultural dimension (masculinity/femininity) in service expectations (e.g., expertise, empathy), (2) contextual boundedness: the influence of industry type, and (3) the potential role played by the gender of service providers in the context of cultural influences on expectations of service delivery.

To address this gap, this study focuses on the “masculinity/femininity” dimension and its impact on service quality expectations in the context of electric vehicle (EV) services. Specifically, this research addresses the following question: how does the cultural dimension of masculinity/femininity influence expectations for expertise, empathy, and responsiveness in electric vehicle (EV) services, and do these expectations vary based on the gender of the service provider? This study extends prior research in two ways. First, we investigate this cultural dimension within the emerging context of electric vehicle (EV) services—a technology-driven industry where cultural dynamics may differ from traditional sectors (e.g., banking, insurance, fast-food industry). Second, we examine whether the gender of service providers affects the relationship between cultural values and service expectations, addressing the gap identified in studies that focused on single-gender contexts [

17,

40]. By integrating cultural theory with industry-specific context, this research advances both theoretical and practical understanding of service quality in the EV market.

3. Research Hypotheses

Research on gender-role stereotypes indicates that the gender of the service provider is a factor influencing perceived service quality [

43,

44,

45,

46]. Building on this foundation, this study intends to examine the relationship between consumers’ cultural dimension (masculinity/femininity) and their service quality expectations in the EV sector, specifically distinguishing male and female service providers as the subjects of investigation. This research is particularly relevant because vehicle purchases are not purely rational decisions—they are deeply embedded in cultural and symbolic meanings, making the interaction between cultural values and service expectations a critical area of exploration [

47]. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory identifies masculinity/femininity as a key dimension measuring cultural tendencies in a society. While gender/sex refers to biological classification, masculinity/femininity represents culturally determined values and traits that transcend biological boundaries, highlighting their nature as cultural constructs rather than biological classifications. These cultural traits can be exhibited or valued by individuals regardless of their biological sex or gender identity, and they play a significant role in shaping perceptions and behaviors in service contexts [

48]. Individuals with “feminine” values tend to align with the perspective that social roles of gender overlap in social life [

49,

50,

51]. In other words, it is believed that both men and women possess characteristics such as being modest, kind, and attentive to the quality of life [

16,

50,

51]. In contrast, those with masculine cultural values emphasize distinct gender roles, associating men with assertiveness, ambition, and material success, while expecting women to exhibit greater warmth and be more modest, kind, and concerned with the quality of life compared to men [

16,

50,

51,

52].

Expertise, a core dimension of service quality, reflects employees’ depth of knowledge and skills in addressing customer inquiries, resolving issues, and providing accurate information throughout the customer journey [

17,

30,

32]. Within the EV industry, expertise additionally requires the ability to instill trust and confidence through professionalism, competence, and consistent behavior [

24]. Given the innovative nature of this sector, expertise is further demonstrated by the capacity to explain technical concepts clearly while addressing range anxiety and safety concerns. This includes ensuring reliability, fostering a sense of security in transactions, and consistently delivering knowledgeable, professional interactions across the entire customer journey [

14]. When evaluating service providers, it is conceivable that variations in expected standards may arise based on the values of the customers and the gender of the service providers [

49,

53,

54,

55]. For instance, when the service provider is female, the “feminine” group may expect more specialized answers and explanations compared to the “masculine” group [

17]. On the other hand, if the service provider is male, the “masculine” group may anticipate more specialized answers and explanations compared to the “feminine” group. Therefore, we propose the following:

H1a. When the service provider of EV is female, the “feminine” group will have higher expectations for expertise compared to the “masculine” group.

H2a. When the service provider of EV is male, the “masculine” group will have higher expectations for expertise compared to the “feminine” group.

Empathy, a critical dimension of the SERVQUAL model, refers to the provision of caring, individualized attention to customers. It reflects the extent to which service providers understand and cater to their unique needs, concerns, and preferences [

17,

31,

40]. In the context of EV services, empathy involves understanding and alleviating range anxiety, delivering personalized care during test drives, and tailoring services to create a supportive experience that addresses customers’ specific concerns [

24]. By offering attentive, customized interactions throughout the ownership journey, empathy fosters emotional connections and enhances customer satisfaction [

33]. Building on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions framework, we examine how masculinity/femininity values shape divergent empathy expectations. Based on this theory, we consider that consumers with masculine cultural orientations tend to maintain traditional gender role expectations, anticipating stronger empathy behaviors from female service providers [

56]. When service providers are male, the pattern reverses. This theoretical perspective yields two hypotheses regarding empathy expectations in EV service encounters:

H1b. When the service provider of EV is female, the “masculine” group will have higher expectations for empathy compared to the “feminine” group.

H2b. When the service provider of EV is male, the “feminine” group will have higher expectations for empathy compared to the “masculine” group.

Responsiveness, a fundamental service quality dimension, refers to the attitude and ability of service providers to assist customers, actively address their needs, and strive to fulfill their requests [

17,

31,

40]. It encompasses not only the prompt reaction to customer inquiries, the timely service delivery but also the willingness to help customers resolve problems and the clear communication of service timelines and progress. In the EV context, responsiveness particularly emphasizes timeliness, proactiveness, and transparency in communication, making it a critical dimension of service quality [

24]. Building on Hofstede’s cultural theory and supported by Furrer et al. (2000) and Tsoukatos et al. (2007), we propose that responsiveness expectations vary based on the consumers’ cultural values [

17,

40]. If the employee is female, the “feminine” group may have higher expectations for customer service compared to the “masculine” group. Conversely, if the employee is male, the “masculine” group may have higher expectations for customer service compared to the “feminine” group. Therefore, the following hypotheses are constructed:

H1c. When the service provider of EV is female, the “feminine” group will have higher expectations for customer service responsiveness compared to the “masculine” group.

H2c. When the service provider of EV is male, the “masculine” group will have higher expectations for customer service responsiveness compared to the “feminine” group.

4. Methodology

4.1. Hypothesis Framework

This study proposes a comprehensive hypothesis framework that examines the impact of cultural dimensions in shaping service quality expectations within the EV industry. The framework is organized around two key dimensions: (1) service provider gender (female/male) and (2) customer’s cultural dimensions: (Masculinity/Femininity) and predicts differential effects across three service quality dimensions—expertise, empathy, and responsiveness. Specifically, the framework posits that when the service provider is female, feminine customers will have higher expectations for expertise (H1a) and responsiveness (H1c), while masculine customers will expect higher empathy (H1b). Conversely, when the service provider is male, masculine customers will exhibit higher expectations for expertise (H2a) and responsiveness (H2c), whereas feminine customers will prioritize empathy (H2b). These hypotheses are grounded in Hofstede’s cultural theory and role congruity theory, which predicts distinct patterns of expectations based on the alignment (or misalignment) between service provider gender and traditional gender roles. The framework is summarized in

Table 1, which provides a clear mapping of the hypothesized relationships.

4.2. Participants and Procedure

To ensure questionnaire validity, a pilot study was conducted. First, a pre-check with 5 domain experts evaluated question design professionalism. Subsequently, a pilot test was administered to 20 participants recruited from 5 dealerships in China. Participants met the same criteria as the main study: having visited an EV dealership and either test-driven or purchased an EV within the past year. They were invited to assess question clarity, relevance, and survey flow. Based on their feedback, we revised 3 ambiguous questions and replaced 5 phrases with more accessible language. The pilot results indicated high clarity (90% of questions understood by >85% of participants), ensuring the final survey’s suitability for the target population.

The main survey was carried out in 2024, wherein questionnaires were directly distributed to 396 participants recruited through multiple automobile sales centers and dealerships in China, covering various electric vehicle (EV) brands to enhance the diversity of the sample. Participants were screened based on specific criteria, including having at least one test-drive experience or having purchased an EV within the past year, ensuring that all respondents had direct experience with EV-related services.

The survey was administered in person at the sales centers and dealerships, participants were provided clear instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. Questionnaires were distributed in paper format and collected on-site to ensure immediate response and minimize data loss. The survey took approximately 15 min to complete, and participants were informed about the purpose of the study and provided informed consent before proceeding. To ensure data quality, incomplete responses and those with contradictory information were excluded from the analysis. Out of the 396 questionnaires retrieved, 377 were deemed valid, yielding a response rate of 95.2%. Among the valid responses, 204 were from males and 169 from females, with 4 missing values for gender information. This methodological approach ensured the quality, accuracy, and validity of the data, as well as the representativeness and effectiveness of the research.

4.3. Survey Design

The survey was designed to assess cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) and customer expectations for service providers in electric vehicle (EV) stores. It consisted of four main sections:

1. Cultural Dimension: Five items measured respondents’ views on cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) using a 7-point Likert scale.

2. Demographic Data: This section collected information on respondents’ gender, experience with EV stores, and participation in test drives.

3. Expectations for Female Service Providers: Seventeen items evaluated customer expectations for female service providers across various service aspects, using a 7-point Likert scale.

4. Expectations for Male Service Providers: Seventeen items evaluated customer expectations for male service providers across the same service aspects, using a 7-point Likert scale.

The survey contained a total of 44 items, with independent variables focusing on perceptions of cultural dimensions regarding gender roles (Part 1) and dependent variables measuring expectations for service providers’ performance (Parts 3 and 4). The items were selected based on a comprehensive literature review of cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) and customer service expectations in automotive retail, supplemented by input from professionals in the EV sector to ensure relevance and comprehensiveness. A pilot test was conducted with a small group of respondents to refine the wording and structure of the survey. Demographic data, including experience with EV stores and participation in test drives, were collected to confirm that respondents met the selection criteria.

4.4. Measures

Constructs in this study were measured using well-established scales adapted from prior literature or with revisions for the EV sector. The questionnaire included multiple sections, each focusing on a specific dimension. A 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) or (1 = Not at All Important, 7 = Most Important) was used for all items unless otherwise noted. The reliability and validity of each scale were assessed, and the internal consistency was calculated to ensure the reliability of the measures.

4.4.1. Service Quality Dimension

The dependent variables (e.g., expertise, responsiveness, and empathy) in this study were derived from the SERVQUAL model and a service quality scale originally developed for the retail industry by Dabholkar et al. (1996) [

57], Park Sun-mi (2006) [

58]. The focus was narrowed to aspects of service quality related to employees. Additionally, considering that the electric vehicle (EV) industry is a typical technology-driven sector where expertise is paramount, the questionnaire was revised to include specific questions addressing the technical knowledge and professionalism of employees. The questionnaire items were adapted to fit the EV store service context, resulting in a final questionnaire comprising 17 items. Each item was measured using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from “Most Important” to “Not at All Important”. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was subsequently applied to these 17 items to assess the underlying structure of the data. The reliability, validity, and internal consistency of each scale were evaluated based on factor loadings, cumulative variance, and Cronbach’s α. The specific values of these metrics (factor loadings, cumulative variance, and Cronbach’s α) will be presented in the next section. The factor scores extracted from the analysis, which represent expectations regarding the service quality provided by employees, were utilized as the dependent variables in the subsequent analyses.

4.4.2. Cultural Dimension

This study draws upon Hofstede’s five-dimensional model as a theoretical foundation, with a specific focus on the cultural dimension of “masculinity”, which has not been thoroughly examined in the context of individual customer values within EV dealerships [

59]. While the original scale, developed by Hofstede in 1980, was designed to measure national culture within the workplace, its direct application to assess individual customer perceptions poses challenges, as noted by Furrer et al. (2000) [

17,

60]. Thus, Furrer et al. tended to avoid workplace-oriented questions in their research to mitigate the risk of committing an ecological fallacy [

17,

61].

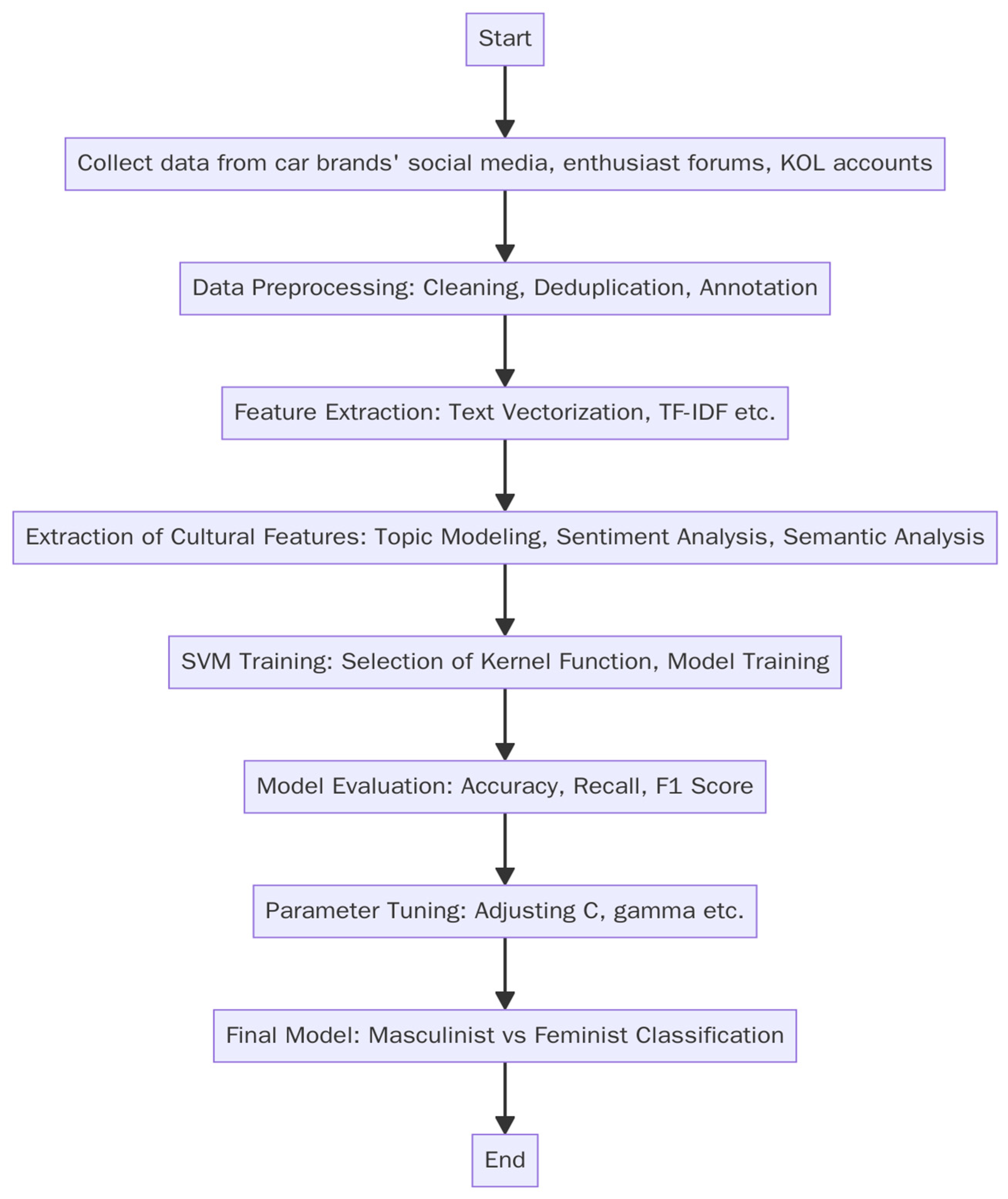

To address these limitations and gain a deeper understanding of how cultural dimensions influence customer expectations of service quality, this study employs a novel approach using the Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm. The SVM algorithm, rooted in statistical learning theory, represents a sophisticated supervised learning methodology. The algorithm extracts a set of characteristic subsets from the training samples, ensuring that the classification of these subsets corresponds to the segmentation of the entire dataset. Extensive empirical evidence across diverse application domains substantiates the SVM’s robust efficacy in resolving a wide array of complex classification tasks [

62,

63]. This classification is based on the extraction of cultural features from the data, providing a direct assessment of cultural values as expressed by individuals in a natural setting. The flowchart for cultural feature extraction and classification based on the SVM algorithm is shown in

Figure 1.

To illustrate the application of the SVM algorithm in cultural feature extraction and classification, the SVM implementation will be elaborated in the following part. The purpose of the elaboration is to enhance understanding of how SVM efficiently classifies samples, thereby offering a theoretical underpinning for the direct assessment of cultural dimensions.

Linearly Separable Case: Assume there exists a hyperplane that can separate two classes of samples. For positive class samples, it satisfies ; for negative class samples, it satisfies . Then, the classification function can be defined as .

Optimal Hyperplane: An optimal hyperplane should have no misclassification and the distance from the hyperplane to the nearest samples of both classes is not less than 1. The optimal hyperplane can be found by minimizing the following objective function:

subject to

, where

is the label (+1 or −1) of the sample

.

Lagrange Dual Problem: Introducing Lagrange multipliers

, the original problem is transformed into a dual problem:

subject to

and

.

Kernel Function: When data are nonlinearly separable, kernel functions can be used to map the data to a higher-dimensional space, making the data linearly separable in the high-dimensional space. Common kernel functions include linear kernels, polynomial kernels, Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernels, etc.

Decision Function: After solving for

, the decision function can be obtained:

Soft Margin: When data contains noise or cannot be perfectly linearly separated, slack variables

and penalty parameter

can be introduced to obtain soft margin SVM:

subject to

.

Building on the theoretical groundwork developed by Hofstede and the methodological advancements proposed by Donthu and Yoo (2011) [

60], this study employs the SVM-based classification to represent the cultural dimension of masculinity/femininity. Through the process depicted in

Figure 1, the classification results based on the SVM algorithm indicate that there are 177 samples in the feminist group and 199 samples in the masculinist group. The groups are used in subsequent analyses to explore the impact of these cultural dimensions on expectations of service quality in EV dealerships, offering a contemporary and data-driven perspective on cultural influences. The analysis strategy was designed to systematically examine the relationships between cultural dimensions, service quality expectations, and gender-specific dynamics in the context of electric vehicle (EV) dealerships.

4.5. Analysis Strategy

The study employed a data-driven methodology, integrating Hofstede’s cultural framework with advanced statistical techniques to uncover the nuanced influence of cultural values on service quality expectations. Additionally, the study incorporated the SVM (Support Vector Machine) algorithm to make classification. Following preprocessing and feature extraction, the model was trained and evaluated to categorize respondents into “masculine” and “feminine” groups, facilitating the classification of cultural features within the data and enabling a deeper understanding of gender-specific cultural dynamics.

Data preparation began with cleaning procedures to ensure data integrity. Incomplete responses and questionnaires with contradictory information were excluded from the analysis. Factor scores extracted from exploratory factor analysis (EFA) were used for subsequent analyses. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal component analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to validate the measurement structure. Factors were retained based on eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and scree plot inspection. Items with factor loadings below 0.40 were discarded, and a cumulative variance of at least 50% was considered acceptable. The internal consistency of each scale was evaluated using Cronbach’s α, with a threshold of 0.70 for acceptable reliability [

33]. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine bivariate relationships between variables (e.g., expertise, empathy, responsiveness) across gender groups, with significance levels set at

p < 0.05. Hypothesis testing involved a combination of one-way ANOVA and cross-gender analysis [

16,

64,

65]. One-way ANOVA was used to assess group differences in service expectations based on “masculinity/femininity” groups, with significance levels set at

p < 0.05.

4.6. Setting and Sample

The study was conducted in the context of electric vehicle (EV) dealerships in China, a rapidly growing market with increasing consumer demand for EV-related services. Data collection took place at dealerships, where customers interact directly with sales and service employees. This setting was chosen to capture real-world service quality expectations in a technology-driven industry. To ensure a representative sample, the “mall intercept” technique was employed [

40]. This approach was selected because it allows for direct interaction with potential respondents in a real-world setting, ensuring that participants had recent and relevant experience with EV dealership services. Trained collectors approached individuals at dealerships and invited them to participate in the survey [

12]. Participants were selected based on the following criteria:

1. They had visited an EV dealership;

2. They had either test-driven or purchased an EV within the past year.

The in-person survey approach not only ensured high response rates but also minimized the risk of self-selection bias, which is often associated with online surveys. The sample consisted of 377 valid responses from EV customers who met the selection criteria. Participants were recruited through multiple automobile sales centers and dealerships across various regions in China, ensuring geographic and brand diversity. The sample included 204 males (54.1%) and 169 females (44.8%), with four missing values for gender information. The sample’s characteristics indicate a balanced gender distribution and urban consumer base, which is representative of the typical EV customer profile in China. However, the study’s focus on EV customers with prior test-drive or purchase experience may introduce selection bias, as their expectations might differ from those of potential buyers. Additionally, the sample may not fully represent rural populations, limiting the generalizability of the findings to these groups. Despite these limitations, the use of the “mall intercept” technique and the inclusion of diverse brand contexts enhance the validity of the findings within the EV dealership setting.

6. Discussion

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on the role of cultural dimensions, particularly masculinity/femininity, in shaping service quality expectations. By focusing on the electric vehicle (EV) sector, a rapidly evolving technology-driven industry, our research offers new insights into how cultural values influence consumer behavior and service expectations. These findings contribute to the literature by extending cultural dimension theory to electric vehicle markets, and proposing solutions to critical cross-cultural adoption barriers for EV manufacturers [

70,

71,

72]. The analysis reveals significant evidence of a link between cultural value orientations and customers’ service expectations, advancing theoretical understanding in this emerging domain.

First, our research addresses a critical gap in the literature by examining the masculinity/femininity dimension, which has been largely overlooked or excluded in prior studies. While Donthu et al. (1998) explicitly excluded this dimension from their cultural analysis, subsequent research has produced contradictory conclusions [

16]. For instance, Furrer et al. (2000) highlighted its significance in tangible service contexts, whereas Kueh et al. (2007) found no substantial effects in standardized service environments [

17,

41]. This study reveals that the cultural dimension of masculinity/femininity acts as a foundational value system, shaping service expectations in technology-intensive sectors. Importantly, this influence operates independently of the service provider’s gender, directly addressing our research question and offering new insights into the role of culture in technology-driven industries.

Moreover, our dual-provider experimental design extends prior research by simultaneously analyzing the impact of both cultural dimensions and service provider gender. The validation of H1a and H2a (lower expertise expectations in high-masculinity groups) confirms the findings of Furrer et al. (2000) and Tsoukatos et al. (2007) [

17,

40]. However, unlike single-gender designs (e.g., Furrer et al., 2000 [

17]; Tsoukatos et al., 2007 [

40]), our study reveals that cultural dimensions directly influence service quality expectations, regardless of the service provider’s gender. Our findings also extend Sarhan and Shishany (2020) by showing that cultural effects on expertise and empathy expectations are consistent across both male and female employees, highlighting the universal impact of culture on service quality expectations [

38]. This aligns with Kueh et al. (2007) observation that standardized processes can neutralize gender effects, but with a critical distinction: in the EV industry, the diminished role of gender could stem from the tech-intensity effect, where the complexity of smart technologies amplifies the need for interpersonal assurance, particularly in masculine cultures [

41]. This finding suggests that industry-specific characteristics, such as technological complexity, can override traditional gender-based expectations, repositioning empathy as a critical compensatory mechanism in tech-driven services.

Finally, our findings also shed light on the limitations of traditional service quality models, such as SERVQUAL, in capturing the interplay between cultural values and technology-driven service expectations. While SERVQUAL has been foundational in service quality research [

14,

30], its traditional dimensions (e.g., tangibles, reliability) may not fully capture the interplay between cultural values and technology-driven service expectations. In the EV industry, where expertise and empathy are paramount, cultural dimensions (masculinity/femininity) redefine the salience of SERVQUAL dimensions. For example, our finding that masculine cultures value empathy over expertise challenges SERVQUAL’s traditional hierarchy, suggesting context reshapes the importance of service quality dimensions. This aligns with critiques of SERVQUAL’s cross-cultural relevance and highlights the need for adaptable frameworks that consider technological and cultural differences [

73]. Traditional tools like SERVQUAL may need adjustments to suit diverse contexts.

These theoretical insights directly inform practical strategies for the EV sectors. Based on these findings, we propose that when developing service strategies, it is crucial to thoroughly consider the influence of cultural dimensions, rather than focusing superficially on gender alone. By aligning service delivery with these cultural dimensions, EV brands can ensure a culturally sensitive customer experience and boost their global competitiveness. For example, the discovery that masculine cultures value empathy over expertise suggests that EV service marketing should prioritize emotional engagement over technical prowess. Transforming test drives into immersive experiences that highlight the emotional benefits of EV ownership can more effectively resonate with consumers in masculine cultural settings [

12,

74]. Moreover, listening to consumer feedback during these interactions and addressing concerns in real-time—such as demonstrating fast-charging capabilities or showcasing a reliable charging network—can alleviate anxieties and strengthen the emotional connection between the brand and the consumer [

75]. This approach not only meets the empathy expectations identified in the research but also sets EV brands apart in a competitive market. Additionally, personalized services are a direct response to empathy expectations. Offering one-on-one tutorials on EV operation, providing tailored charging solutions based on individual driving patterns, or designing customized maintenance plans can address the specific needs and concerns of EV consumers. These personalized services not only align with the heightened empathy expectations in masculine cultures but also build trust and reassurance, which are essential for fostering long-term customer relationships. By demonstrating a deep understanding of consumer challenges, such as range anxiety or charging accessibility, service providers can create a sense of emotional support that enhances customer satisfaction and loyalty [

10]. This strategic focus on cultural nuances and personalized care can significantly elevate the overall customer experience and solidify the brand’s position in the global market.

This research focuses on the direct influence of cultural dimension (masculinity/femininity) on service quality expectations in technology-driven industries. However, given the complexity of consumer behavior, other factors such as emotional experience [

76], brand trust/identification [

77,

78], and brand loyalty may also shape service quality perceptions [

42,

79]. Therefore, further research on this topic requires in-depth analysis, particularly on the roles of emotional engagement and brand-related factors (e.g., brand trust and loyalty) in mediating or moderating the relationship between cultural dimensions, service quality expectations, and customer satisfaction. Second, limited by the scope of our study, we only examined the direct impact of cultural dimension (masculinity/femininity) without exploring how contextual factors, such as industry-specific dynamics or technological advancements, might influence these relationships. Future research should expand the boundaries of this field by investigating how individual characteristics (e.g., demographic variables, personal preferences) [

6,

80] and situational factors (e.g., service environment, technological advancements) interact with cultural dimensions to affect consumer behavior [

81,

82]. Such explorations would not only deepen theoretical understanding but also provide actionable insights for stakeholders in the EV sector and other technology-driven industries to design personalized marketing and service strategies.