Abstract

This paper introduces a methodological framework for assessing the impacts of digital infrastructure disruptions in urban traffic networks, using traffic signal tampering as a case study. A readily quantifiable indicator, the Average Flow Reduction Metric (AFRM), is proposed to capture network-wide flow reduction based on the principles of the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram (MFD). The framework is applied to a simulated network under various tampering scenarios and routing behaviors, including fixed, flexible, semi, and fully adaptive routing. The results show that AFRM correlates meaningfully with conventional disutility-based network performance metrics and serves as a reliable proxy for network degradation, especially under established or rationally adaptive routing behaviors. Due to its reliance on commonly available traffic measurements, AFRM provides a practical tool for diagnosing and managing digital disruptions in traffic networks. As such, it may support traffic managers in assessing, preparing for, monitoring, and responding to disruptions in real time.

1. Introduction

Transport networks are crucial enablers of social cohesion, economic development, and spatial integration, facilitating the circulation of people, goods, and services within and between communities. Despite the substantial institutional and financial support that transport networks typically receive, they remain inevitably exposed and vulnerable to a broad range of stressors, including natural hazards, human-induced threats and errors, and capacity reductions due to planned or unplanned infrastructure construction or maintenance activities [1,2]. These stressors highlight the volatility of the environments in which transport networks operate, indicating that a stable operating context cannot be assumed over time. Instead, empirical evidence shows that proactive planning and operational strategies by transport authorities are essential to mitigate disruption impacts, for example, by developing appropriate contingency and response frameworks and measures [3,4]. As a result, fundamental concepts from resilience and lifeline engineering have been progressively embedded into the analysis, design, and management of transport networks, as reviewed by Gu et al. [5].

While much of the existing research has focused on physical infrastructure disruptions, such as bridge collapses or road closures, comparatively less attention has been given to disturbances affecting digital infrastructure components, despite their growing importance. Systems such as telematics platforms, automated driving technologies, data exchange services, and traffic control mechanisms are critical to the real-time operation and coordination of modern, technology-dependent transport networks.

Disruptions to these systems may result from various causes, including extreme weather, power failures, human errors, technical malfunctions, and deliberate attacks, with significant impacts on traffic flow and traveler safety. For example, the 2024 Hurricane Beryl destroyed hundreds of traffic signals in Houston, causing widespread traffic disorder [6]. According to the Texas Department of Transportation, daily collisions at signalized intersections increased by 41% during the disruption period [6]. Similarly, during the 2024 Hurricane Helene in South Carolina, 207 traffic signals lost power, and the Greenville Police Department recorded 39 road collisions at that time [7]. In 2018, a bug during a software update of the traffic control system in New York City disrupted the operation of approximately 600 traffic signals [8]. Moreover, a simulation study of Austin’s road network showed that disabling 26 traffic signals could increase total traffic delay by a factor of 4.3, corresponding to USD 0.98 million in delay costs [9]. According to the authors, a similar effect can be achieved through the targeted disruption of only seven traffic signals. Although such deliberate actions may have been considered relatively uncommon in the past, existing analyses indicate an increasing trend in cyber threats [10,11], while some observers report 27 publicly documented cyberattacks between mid-2023 and mid-2024 targeting the transport and logistics sector [12]. In this context, some countries, such as the Netherlands, are now considering replacing actuated traffic signal control systems that have proven susceptible to spoofing by Internet of Things (IoT) devices [13].

The current paper offers to the body of research on transport resilience a methodological framework and a readily quantifiable metric, based on the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram (MFD), to assess the traffic-related impact of digital infrastructure malfunctions, with a focus on traffic signal tampering. Its remainder is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief overview of the state of the art in the cybersecurity of digital and intelligent transport technologies, with emphasis on traffic signal tampering, and summarizes the study’s main contribution. Section 3 presents the methodological approach and experimental design. Section 4 and Section 5 report the results of the basic experiment and a sensitivity analysis involving variable traffic states, respectively. Section 6 discusses the findings, the practical exploitation potential of the proposed framework within Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS), and its generalization to real-world networks. Finally, Section 7 concludes the study and outlines directions for future research.

2. Background

2.1. Related Work

The current state of the art in the cybersecurity of digital and intelligent transport technologies addresses a range of interrelated issues, covering theoretical, analytical, and design or development aspects, as well as passive and active attacks. According to Pan et al. [14], passive attacks involve a loss of confidentiality and privacy, while active attacks involve deliberate system manipulation by injecting false data, altering messages, or preventing communication. Key topics include (1) the analysis of passive attacks in cloud-based Internet of Vehicles and the suggestion of defense measures [15]; (2) the analysis of safety and traffic flow implications of active cyberattacks on connected and automated vehicles (CAVs) and vehicle platoons [16,17,18,19,20], considering various attack types and severity levels, traffic heterogeneity, degrees of cooperation, communication delays, and operational contexts affecting traffic stability and safety; (3) intrusion and abnormal activity detection in vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs) [21]; (4) the design of secure system architectures, protocols, and digital twin platforms [22,23]; (5) Artificial Intelligence (AI) and game-theoretic approaches to adaptive threat response [24,25]; (6) malware detection in IoT-enabled ITS environments [26]; and (7) the comprehensive scoping and classification of threats, impacts, and defense strategies across multiple system layers [27,28,29,30].

Notably, Khattak et al. [16] and Li et al. [17] examine how falsified or manipulated vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication can compromise safety, particularly during dynamic maneuvers such as lane changes or deceleration. Malik and Sun [18] extend this by identifying high-priority cyber threats and simulating their impact on CAVs using the CARLA platform, showing that targeted attacks on communication or control systems can cause large-scale collisions and cascading failures. Cheng et al. [20] show that high vehicle penetration and multi-vehicle cooperation can mitigate the effects of cyberattacks, while unfavorable car-following patterns and long communication delays destabilize mixed traffic, leading to delays, congestion, and increased collision risk. At the architectural level, Sellitto et al. [22] introduce a cybersecurity digital twin to simulate and assess cyber risks in cooperative ITS services without interfering with operational systems.

On the other hand, studies assessing the impacts of disruptions in essential digital infrastructure, such as traffic control equipment, from a network-level perspective remain relatively more limited, and significantly fewer than those focusing on physical infrastructure disruptions. Table 1 provides an overview of existing related studies, including their objectives, adopted traffic performance metrics, and application areas. It is clarified that the studies by Chowdhury et al. [31,32], although explicitly related to traffic signal intrusions, are not included in Table 1, as their primary focus is on intrusion detection using fused traffic and signal data, rather than on impact assessment.

Table 1.

Overview of studies focusing on the assessment of traffic signal disruptions.

The above studies have produced a range of methodological contributions and empirical insights. For example, Laszka et al. [33] show that identifying the most disruptive signal attacks corresponds to NP-hard optimization problems and propose a polynomial-time heuristic. Similarly, Thodi et al. [34] formulate signal tampering as a bi-objective optimization problem and use a time-expanded super-graph to transform dynamic traffic flows into a static network flow representation, enabling efficient linear programming solutions. They also find that (1) even minor adjustments to signal timings can cause severe congestion, and (2) network vulnerability, reflected in the shape and slope of the constructed Pareto frontier, is comparatively more strongly influenced by structural characteristics and attack duration than by traffic demand levels. Ganin et al. [35] show that (1) the covert manipulation of traffic signal states (e.g., locking signal phases) causes greater network-wide delays than overt failures such as fully disabled signals; (2) targeting signalized intersections with high traffic load results in larger delays than targeting intersections based solely on topological metrics (e.g., betweenness); and (3) the relative vulnerability of cities to signal-related disruptions remains largely invariant across disruption severities, indicating a structural network property. They further emphasize the need for dedicated detection and response strategies for locked or manipulated signal states. Comert et al. [36] demonstrate that controller compromises can propagate across adjacent intersections and increase delays, particularly in the absence of redundant sensing, highlighting the need for robust detection and cybersecurity mechanisms in connected vehicle environments. Feng et al. [37] emphasize the strong scenario dependence of attack impacts, showing that identical signal tampering strategies can yield widely different outcomes; notably, in some scenarios involving ineffective or poorly targeted attacks, travel times were observed to improve. Finally, Perrine et al. [9] find that (1) a small number of strategically targeted signal disruptions can cause disproportionate network-wide delays; (2) signals serving high traffic volumes or critical paths exert a disproportionate influence on system performance; (3) delays from signal outages are unevenly distributed across space and users; and (4) selectively protecting critical signals can substantially mitigate delays when attackers lack information about which assets are protected.

2.2. Contribution

Existing approaches in Table 1 assess the impacts of disruptions to traffic signal control using performance metrics predominantly derived from trip-based information, such as increases in delay and total travel time, reductions in throughput (i.e., trip completion rates), and estimations of queue length at signalized intersections. These metrics provide valuable insight into the consequences of cyber–physical disruptions; however, their applicability in real-world settings is often constrained by the limited observability of complete vehicle trajectories and the difficulty of measuring queue propagation across the entire network.

To overcome this limitation, this study introduces a practical and readily quantifiable metric that can be adopted by traffic managers and verified under real-world conditions using conventional field measurement devices (e.g., inductive loop detectors). The metric is grounded in traffic control principles and established theory on the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram (MFD), specifically the production MFD (pMFD), following the convention of Leclercq and Paipuri [38]. This metric captures the reduction in average network flow (production) across different levels of vehicle accumulation (traffic density).

The theory of MFDs has been applied in various contexts, including network evaluation, traffic resilience, and real-time monitoring. Recent examples in network evaluation include (1) the work of Taillanter et al. [39], which links MFD parameters to road length density, intersection density, speed limits, and vehicle size, showing that the MFD shape is predictable from network structure and modal composition; and (2) the theoretical model by Yuan and Knoop [40], which attributes MFD hysteresis and the frequent absence of a congested branch to route choice behaviors conforming to departure-time User Equilibrium, rather than to data insufficiency. In the context of traffic resilience, examples include (1) the study by Lu et al. [41], which assesses physical infrastructure disruptions in Munich and Kyoto using indicators based on the reduction in trip completion rate relative to the baseline MFD; and (2) a follow-up study by the same group [42], which applies this MFD-based indicator to optimize post-disruption lane reversal strategies via surrogate modeling. For real-time monitoring, examples include (1) Maiti et al. [43], who evaluate scaling and imputation methods for reconstructing network accumulation and flow with limited sensor coverage; (2) Xue et al. [44], who introduce an MFD-constrained graph neural network for traffic state imputation; and (3) Lee and Lee [45], who propose a congestion-boundary approach to identify real-time phase transitions using speed and density distributions, distinguishing between congestion onset, initiation, recovery, and alleviation thresholds.

To the best of our knowledge, systematic efforts to link MFD theory with disruptions of or attacks on traffic control equipment remain limited, despite the potential computational and monitoring benefits that such an approach may offer. The proposed approach, described in detail in Section 3, aims to support this connection. Its applicability is tested on a case study using a simulated traffic network and is benchmarked against a set of metrics grounded in utility theory (e.g., generalized travel cost shifts).

Overall, the contribution of the current study can be summarized as follows:

- We propose a metric for assessing disruptions in digital infrastructure that (1) is measurable and verifiable by traffic managers in real-world settings and (2) overcomes the observability limitations of trip-level information.

- We demonstrate a promising research direction for the MFD theory.

- We evaluate the proposed approach and metric using microscopic traffic simulation vis-à-vis a set of disutility indicators, encompassing those listed in Table 1.

3. Materials and Methods

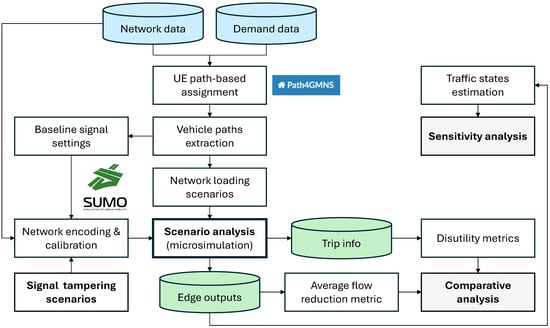

The methodological workflow of this study is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the adopted methodological workflow.

Due to the lack of real-world network data, the analysis in this study is conducted on one of the most widely used test networks in the transport-related literature, i.e., an aggregated version of the Sioux Falls network in South Dakota (USA), encoded in the Eclipse SUMO traffic simulator (version 1.12.0, German Aerospace Center, Berlin, Germany). Topologically, the network is comparable to several grid networks used in other studies (see Table 1) and to Manhattan-style scenarios in CAV-related literature (e.g., see [46,47]). The existence of several segments and multiple routing options provides a sufficiently complex analytical context. Additionally, the presence of irregular intersections, including one with more than four converging links (i.e., at Node 10), increases the representation of non-uncommon complex infrastructure configurations and intersections within real-world urban networks. Given the concerns raised in previous research regarding the rationality of the original traffic demand [48], this has been scaled down to 100,000 vehicle trips while preserving spatial distribution. The uneven accumulation of demand in certain zones adds another layer of realism, reflecting the widely accepted notion of urban space hierarchy.

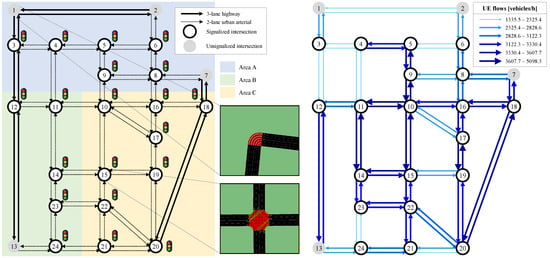

On the supply side, the network is encoded using two road classes, as shown in Figure 2. Traffic lights with fixed cycle lengths (between 90 and 120 s) are installed at intersections where more than two roads converge. For experimental balance, we assume that these traffic lights are centrally coordinated by three traffic signal controllers, each operating within a designated area (Areas A, B, and C). These areas are delineated to (1) be of comparable size, (2) exhibit a regular and spatially compact shape (consistent with common practices for assigning coordination responsibilities in traffic control centers), (3) encompass road corridors with varying traffic intensity, and (4) include links from both road classes. The number and configuration of signal phases are initialized based on the principles of the dual-ring controller.

Figure 2.

Test network layout and its configuration within the Eclipse SUMO traffic simulator (left); UE flows aggregated at a street level, as derived from Path4GMNS (right).

Network loading is implemented through path flows obtained from the solution to the User Equilibrium (UE) traffic assignment problem by (1) using the Path4GMNS interface (version 0.8.0, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA) of the DTALite transport modeling platform [49] and (2) translating these flows into SUMO-compliant XML route files. Path4GMNS employs the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) volume-delay function and supports several traffic analysis procedures, including link-based UE, path-based UE, dynamic traffic assignment, and Origin–Destination matrix estimation. We use the path-based UE to obtain granular (path-level) flow information required to generate explicit vehicle routes in SUMO. Specifically, the resulting path volumes are used to generate vehicle trips that depart with a gradually increasing rate over the network loading period (1 h). This is performed to capture a wide range of traffic states using a random power distribution function (implemented through the random.power NumPy function with a = 1.25).

The BPR shape parameters are set to their typical default values (a = 0.15, b = 4), while the per-lane capacity of the network’s roads is set to 1900 vehicles/hour for highways and 1000 vehicles/hour for urban arterials [50]. Correspondingly, free-flow speed is limited to 90 km/h and 50 km/h, respectively.

The derived UE flows, aggregated at the street level (Figure 2), are used as input to Webster’s [51] method for traffic signal design (implemented in the SUMO library) to determine green times for each phase. These timings are further refined in a stepwise manner, along with intersection connections, to better utilize available network capacity and reduce traffic queues.

In addition to the network loading method described above, hereafter referred to as “fixed routing”, three additional routing behaviors are implemented. The first, termed “flexible routing”, involves the relaxation of vehicle paths derived from UE traffic assignment (i.e., removing intermediate links) to allow trips to follow the fastest routes based on prevailing traffic conditions at the time of departure. The second behavior, termed “semi-adaptive routing”, builds on the previous one by incorporating a rerouting device with network-wide coverage that provides all drivers with updated traffic information every 60 s. Drivers are assumed to switch routes with a probability of 50% based on the information received. The third behavior, termed “adaptive routing”, is a variation of the semi-adaptive case, where drivers are assumed to switch routes with a probability of 100%. It is intentionally included as an upper-bound stress scenario to test the limits of macroscopic, infrastructure-centric indicators under extreme route choice adaptation.

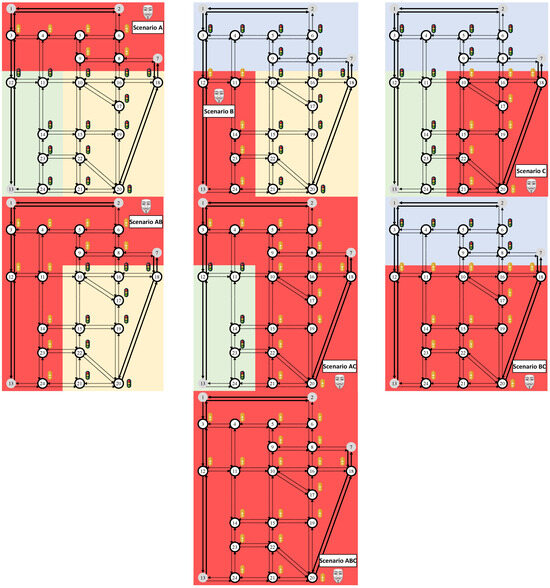

Based on the above modeling and traffic simulation testbed, we assume that a malicious entity gains access to existing signal controllers and tampers the traffic signal control programs within their respective areas by introducing an “all-red” phase lasting 10 s at the beginning of each cycle. This attack behavior represents an intermediate case between the covert and overt manipulation scenarios distinguished by Ganin et al. [35], as it introduces a detectable disruption without fully disabling signal operation. As illustrated in Figure 3, signal tampering scenarios are spatially varied to cover each area individually, all pairwise combinations, and all areas simultaneously (A, B, C, AB, AC, BC, ABC). These scenarios are used to test the proposed framework under signal tampering conditions of increasing spatial extent and total intensity, extending progressively to the full network. Each tampering scenario is paired with the four assumed route choice behaviors, resulting in a total of 28 scenarios.

Figure 3.

Overview of the analyzed traffic signal tampering scenarios (affected areas are highlighted in red).

The impact of each scenario on prevailing traffic conditions is evaluated through the following metric reflecting average relative flow reduction (AFRM):

where and denote the average (per-link) flow rate in the intact and affected (according to scenario j) network states, respectively, i.e., , when the density on each link equals . represents the set of physical network links and their total number. This formulation captures the relative reduction in the unweighted space-mean network flow, based on existing empirical evidence by Geroliminis and Daganzo [52] and Geroliminis and Sun [53] suggesting that both weighted and unweighted averages of the main traffic parameters (e.g., flow, speed, density) can be used to generate well-defined MFDs. The macroscopic flow–density relationship is approximated using a single-regime, non-physical functional form [54], specifically, a 3-degree polynomial, as frequently performed in the literature [55,56]. The bounds and in Equation (1) are determined by considering both intact and perturbed network states and their common (i.e., overlapping) density domain, as follows [57]:

It is noted that restricting the integration bounds to the overlapping density domain is considered as the only meaningful choice, as evaluating flow rates over heterogeneous density ranges would compromise the comparability of the resulting quantities.

The traffic flow measurements required for calculating AFRM are obtained from the edge data outputs of the corresponding SUMO simulation experiments. To avoid the effects of loading–unloading hysteresis [58], only data from the network loading period are considered. Each experiment is repeated using five different random seeds.

AFRM is benchmarked against a series of disutility-based indicators, summarized in Table 2. These indicators are quantified using trip information from the corresponding SUMO simulation experiments. Unless otherwise specified, the trip data covers the entire simulation duration, which is set to an arbitrarily large value to allow vehicles to reach their destinations.

Table 2.

Benchmark travel disutility indicators.

The last entry in Table 2 refers to a consensus ranking of the analyzed scenarios based on the Kemeny–Young method [59], which has been used in the literature to derive consensus rankings of street criticality across multiple metrics [60]. Due to its exponential computational complexity, we approximate it using a Monte Carlo-based approach involving ranking initialization, iterative swapping, and a selection of the ranking that minimizes total pairwise disagreements.

The derived results are evaluated using logical and statistical checks, including Pearson’s, Spearman’s, and Kendall’s tau correlation indices. Pearson identifies linear associations between AFRM and the benchmark disutility metrics; Spearman evaluates the consistency in the relative ordering of scenarios based on the obtained rankings; and Kendall’s tau assesses the level of pairwise agreement among these rankings, indicating the stability of AFRM’s prioritization across different performance metrics.

For each pair of variables, given the limited sample size, p-values are computed using permutation-based tests for the Pearson, Spearman, and Kendall correlations. Furthermore, uncertainty in the correlation estimates is assessed using an 80% bootstrap confidence interval (CI), defined by the 10th and 90th percentiles of the bootstrap distribution.

Finally, in an effort to check the stability of the integration bounds used in Equation (1), as defined in Equations (2) and (3), a sensitivity analysis is conducted under varying traffic states. The methodology and results of this analysis are presented in Section 5.

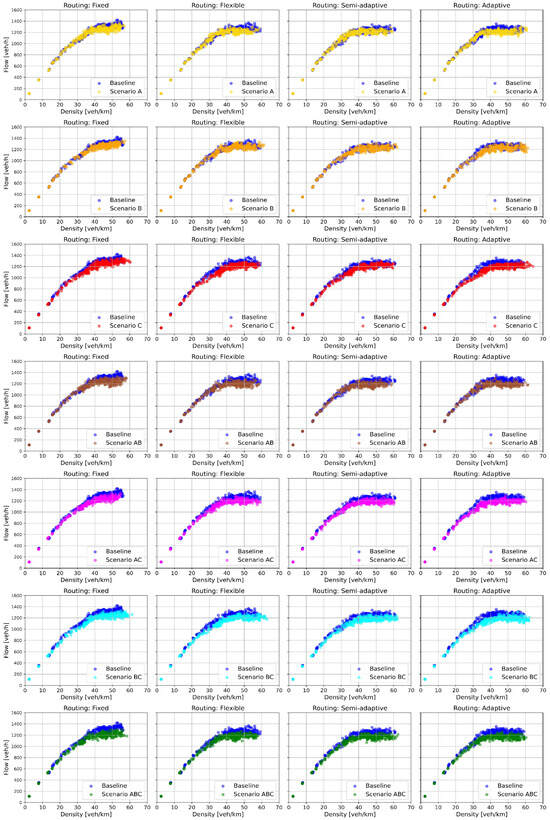

4. Performance Evaluation

Figure 4 depicts the MFD of the tested road network across all analyzed scenarios, including the baseline. In the baseline state, the fixed routing behavior results in a higher maximum average network flow (i.e., average network capacity) of approximately 1300 vehicles/hour. Under flexible and adaptive route choice behaviors, this value is slightly reduced; however, as drivers become more adaptive, the congested regime becomes more pronounced, indicated by a higher maximum density. This suggests that, under fixed routing, the network accommodates a larger volume of traffic more productively before persistent congestion emerges. In contrast, the increased visibility of the congested regime under flexible, semi-adaptive, and adaptive behaviors indicates more uniform utilization of the road infrastructure once critical density is exceeded (i.e., increased congestion homogeneity). This is expected, as drivers with routing flexibility, access to real-time information, and varying levels of compliance tend to redistribute themselves more evenly across the network when congestion builds up.

Figure 4.

Flow–density Macroscopic Fundamental Diagrams (pMFDs) corresponding to the analyzed signal tampering scenarios and route choice behaviors.

Regarding AFRM outputs in the context of single-controller scenarios, the most impactful case involves Area C across all analyzed routing behaviors. This is largely expected, as the UE flow results (Figure 2) show that the average number of vehicles directed toward signalized intersections in Area C is 3465.8, compared to 2933.9 in Area B and 2838.1 in Area A, indicating a significantly higher number of affected drivers.

For multi-area scenarios, the most impactful scenario under the flexible routing behavior involves tampering the controllers of Areas B and C, with the controller of Area A operating normally (Scenario BC). This can be attributed to the fact that, under flexible routing, drivers receive information at departure and tend to reroute toward Area A, which initially appears less congested. This results in increased congestion homogeneity during the transition state and more widespread queue formation across the network. However, delays are reduced more effectively compared to in other scenarios, as drivers manage to avoid specific bottlenecks within Areas B and C.

Conversely, under the fixed, semi-adaptive, and adaptive route choice behaviors, the most impactful scenario involves all three areas simultaneously (Scenario ABC). This is expected, as the system-wide controller malfunction affects the entire network at once, thereby affecting all users and limiting available rerouting opportunities.

A full comparison of AFRM with the benchmark disutility indicators is presented in Table 3. As shown, under the less dynamic routing behaviors (i.e., fixed and flexible), the greatest increase in road user disutility, in terms of total, en-route, and waiting times, time losses, and reduced trip completion rates, is generally associated with the system-wide malfunction (Scenario ABC). In contrast, under the more dynamic behaviors (i.e., semi-adaptive and adaptive), the greatest disutility impacts are mostly linked to either Scenario AC or Scenario BC. This can be attributed to the ineffective diversion of road users toward areas that appear more attractive at certain time steps, or to frequent route switching by drivers, which ultimately results in higher overall system costs.

Table 3.

AFRM and travel disutility indicators per tampering scenario and routing behavior.

Interestingly, certain single-area tampering scenarios (e.g., Scenario A and B) occasionally result in improved road user disutility. While this may appear counterintuitive at first, it is not entirely unexpected, as reducing inflow rates along key traffic corridors constitutes a well-known traffic management strategy [61,62].

For example, tampering only Area B’s traffic signal controller facilitates the desynchronization of traffic queues, particularly along highly congested corridors (e.g., the one through Nodes 11–10–16–18), and reduces interference at key intersections, such as those at Nodes 10 and 15. Furthermore, as noted in Section 2.1, similar results have been reported by Feng et al. [37] in the context of ineffective signal attacks.

Another notable observation from Table 2, based on AERTTI and ATTTI, is that the smallest increases in travel time are associated with flexible routing, while the largest increases often correspond to adaptive behavior. This suggests that when drivers receive information only at trip departure, rather than continuously switching routes as they approach their destinations, average travel times are lower, and the impacts of signal control malfunctions are more limited. This pattern aligns with the concept of rational inattention, whereby individuals choose to ignore information when the cost of processing it outweighs the expected benefit [63]. While the information received by drivers at discrete moments during the simulation period reflects valid conditions at those times (i.e., based on dynamic shortest-path computations), this does not guarantee that the network will reach an equilibrium state if all users act on it simultaneously in an identical manner. Therefore, partially or completely disregarding this non-individualized information can be interpreted as a form of rational inattention. The results would have been much different if a Dynamic User Equilibrium (DUE) approach (e.g., Logit-based) had been applied, i.e., through SUMO’s duaIterate tool. However, this (1) lies outside the scope of this study and (2) may not be representative of user responses to short-notice disruptions.

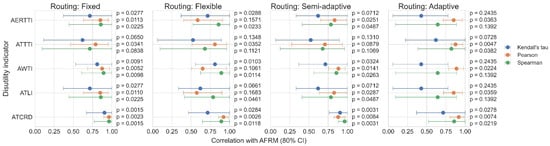

Figure 5 presents the correlation between AFRM and the travel disutility metrics across all tampering scenarios and routing behaviors, based on Kendall’s tau, Pearson’s, and Spearman’s coefficients. Under fixed routing, AFRM shows a consistently strong and positive relationship with nearly all disutility metrics. Notably, Pearson’s and Spearman’s coefficients exceed 0.85 for AERTTI, AWTTI, and ATLI, and surpass 0.95 for ATCRD, resulting in an average correlation of 0.83 across all indices and metrics. The corresponding p-values are consistently low (i.e., below 0.1 in all cases). Under flexible routing, the level of correlation generally decreases. For example, Pearson’s coefficients between AFRM and AERTTI, and between AFRM and ATLI, as well as the Kendall’s tau coefficient between AFRM and ATTTI, fall below 0.60, leading to a reduced average correlation of 0.74. In addition, in five cases, the corresponding p-values exceed 0.1. In contrast, under semi-adaptive routing, an upward trend is observed. The Pearson coefficients between AFRM and AERTTI, and between AFRM and ATLI, return to values above 0.80, and the average correlation across all indices increases to 0.77. The number of cases in which the p-values exceed 0.1 drops to two. Finally, under adaptive routing, correlations exhibit greater variability, as reflected in their relatively wider range. Although Pearson’s coefficients remain high for all disutility metrics, the corresponding Kendall’s tau values for AERTTI, AWTTI, and ATLI are substantially lower (each equal to 0.43). As a result, the average correlation decreases to 0.71, and the number of cases with p-values exceeding 0.1 increases to six.

Figure 5.

Correlation of AFRM with the adopted travel disutility indicators.

Overall, Figure 5 shows that AFRM exhibits a strong correlation with the adopted disutility indicators under fixed routing. This correlation is reduced when user behavior is determined only at trip departure, increases again with moderate route switching, and decreases again when routes are adjusted too frequently. This pattern can be explained as follows. Under fixed routing, both AFRM and the disutility indicators consistently reflect the underlying traffic degradation, i.e., speed reductions align with travel time increases, as total vehicle mileage is predefined. When routing decisions are made only at departure, this often creates positive benefits for road users. However, flow redistribution is not fully synchronized with emerging congestion patterns, resulting in a relatively less consistent relationship between AFRM and the disutility indicators. Semi-adaptive routing partially realigns traffic demand and user behavior with evolving network conditions, thereby reinforcing the connection between the production-based and disutility indicators. Finally, fully adaptive routing introduces oscillatory dynamics and increased competition, which tend to decouple user- and infrastructure-centric benefits.

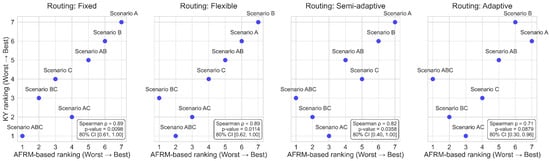

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between AFRM-based scenario rankings and the Kemeny–Young (KY) aggregated rankings for each routing behavior, along with the corresponding Spearman correlation coefficients. Under fixed and flexible routing, AFRM accurately ranks the least critical scenarios (A, B, AB), with only minor discrepancies among the most critical ones, resulting in a high Spearman correlation of 0.89. Under semi-adaptive routing, discrepancies appear for scenarios of both moderate and high criticality, reducing the correlation to 0.82. Under adaptive routing, AFRM performs less consistently, showing noticeable discrepancies across scenarios of low, moderate, and high criticality, which further reduces the correlation to 0.71. The slightly advantageous aggregated ranking of flexible routing compared to semi-adaptive routing can be attributed to the more frequent dominance of the respective Kendall’s tau coefficients (see Figure 5).

Figure 6.

Relationship between AFRM-based scenario ranking and KY consensus ranking.

The above results confirm the usefulness of AFRM as a practical indicator for assessing digital infrastructure disruptions, particularly in contexts where drivers are unlikely to engage in aggressive route switching. Such conditions are common in real-world networks, where route choice adaptation is constrained by heterogeneous information availability, individual preferences, and subjective perceptions of travel conditions.

5. Sensitivity Analysis

Although computing AFRM over a wide range of traffic states to which a network can be exposed is the most rational and representative approach, this section further examines the sensitivity of the proposed metric to the adopted integration bounds.

The literature proposes several elegant approaches for distinguishing traffic states in road networks by employing either statistical, percolation theory-, or MFD-based approaches, such as the framework by Lee and Lee [45], as discussed in Section 2. However, these methodologies typically address sustained network loading conditions (e.g., based on daily demand profiles), which is not the case in the current study.

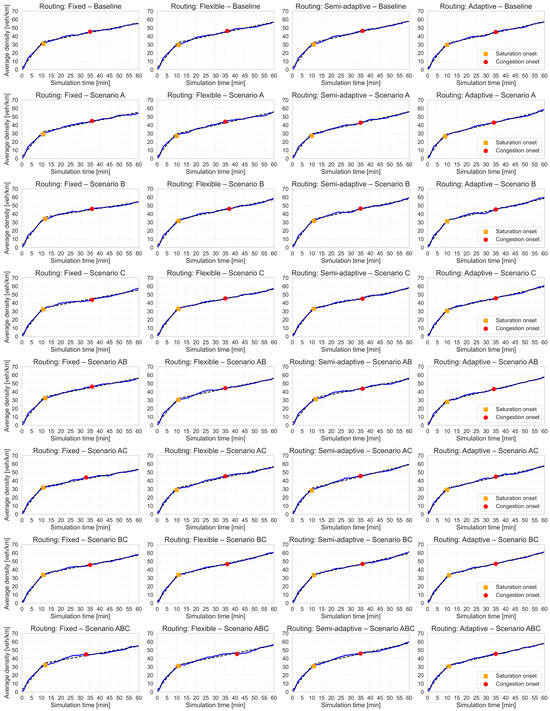

To address this challenge, following Tesone et al. [64], we distinguish between (1) saturation onset, representing a transition phase during which the network enters a higher vehicle accumulation regime, and (2) congestion onset, after which vehicle accumulation reaches a significantly higher level. This distinction cannot be made based on traffic flow rate, due to its dual nature (similar values can occur in different states), but can instead be supported by traffic speed and density [45].

By closely inspecting the shape of the MFDs in Figure 4, it is evident that traffic density increases rapidly when the network is sparsely loaded, up to a point beyond which the rate of increase slows due to the gradual accumulation of a larger number of vehicles that need to be served. This point does not necessarily correspond to a high average (i.e., network-wide) density, due to the constraints imposed by traffic heterogeneity. Subsequently, approximately in the middle of the branch following this point, a noticeable increase in the dispersion of the flow–density pairs becomes apparent. According to Geroliminis and Sun [53], this feature may indicate the onset of congestion, as increased scattering has been empirically observed from that point onward.

In this context, let denote the network loading period and the network-average traffic density (vehicles/km) at time obtained by spatial aggregation over all network links and temporal averaging within each simulation interval. Let also be the ordered sequence of observed density values, with . The saturation onset is defined as the time instant at which the temporal evolution of network density exhibits a structural change in its growth rate. To identify this transition, the density trajectory is approximated by a two-segment piecewise linear model of the form:

where denotes the saturation onset time, , , , and the set of regression coefficients, and and the zero-mean error terms. The optimal breakpoint is estimated by minimizing the total sum of squared residuals of the two ordinary least squares regressions over all admissible breakpoints , subject to a minimum number of observations per segment, , i.e.,

where . The corresponding saturation onset density is then defined as .

Following the identification of this point, let denote the set of density observations recorded onwards. A characteristic congestion level is identified as the empirical median of the post-congestion density distribution, i.e., .

Subsequently, the congestion onset time, , is approximated as the first observed time instant whose density is closest to this characteristic level, i.e.,

The congestion onset density is set to the value observed at , i.e., .

Figure 7 presents the evolution of traffic density throughout the network loading period, along with the identified saturation and congestion onset points, setting . As shown, saturation onset is identified in most cases at densities close to 30 vehicles/km, while congestion onset does so at around 45 vehicles/km.

Figure 7.

Evolution of traffic density throughout the network loading period, with the identified saturation and congestion onset points indicated (dashed lines represent the outcomes of the two-segment piecewise linear model across each tampering scenario and routing behavior).

On that basis, AFRM is re-computed for each scenario using the following bounds:

Equations (7)–(9) imply the removal of the congested regime, the removal of the free-flow regime, as well as the symmetrical removal of both. In this way, the current sensitivity analysis adopts a balanced approach, maintaining a common reference point (the saturation regime) while progressively neglecting unfavorable traffic conditions, highly favorable conditions, and both simultaneously. It should be noted that, under the adopted experimental setup, vehicles enter the network and complete their trips under a mixture of traffic conditions, covering both loading and unloading periods. Consequently, computing the AFRM solely based on extreme conditions, such as pure free-flow or fully congested regimes, would be biased and non-comparable with the disutility indicators, as defined and computed in Section 3 and Section 4, respectively.

The updated AFRM values are re-evaluated using (1) all routing behaviors, (2) the average of all correlation coefficients computed in Section 4 (Pearson’s, Spearman’s, Kendall’s tau) across all disutility metrics and tampering scenarios, (3) their standard deviation, serving as a proxy for uncertainty, as well as (4) the elasticity of average correlation reduction (in relation to the reduction in the considered density range).

Table 4 summarizes the results of the current sensitivity analysis. For the ease of comparison, the table also includes the average values and the standard deviations corresponding to the basic experiment (Section 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes of sensitivity analysis.

The AFRM should be interpreted as sufficiently stable, given that (1) the average correlation across all indices and scenarios did not fall below 0.56, (2) the density range used for the AFRM computation was reduced by 19% to 77%, while (3) the computation of the disutility indicators remained completely unmodified. Therefore, although the outcomes already conform to common acceptability criteria (e.g., all elasticity values are below 1.0), the actual stability can be considered even higher. Moreover, in certain cases, the correlation between the AFRM and the various disutility metrics was enhanced, without substantial differences in the level of uncertainty, as expressed through standard deviation.

6. Discussion and Recommendations

6.1. Reflection on Experimental Results

The derived results underscore the potential of macroscopic traffic analysis tools, i.e., the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram (MFD), to extend beyond their traditional application in traffic management and control to the assessment of disruptions in the digital infrastructure of road networks. The proposed AFRM demonstrated consistency in capturing the effects of such disruptions when compared to conventional disutility-based performance metrics (e.g., total travel time, en-route delay, and waiting time), indicating its usefulness as a proxy for network-wide degradation.

However, the accuracy and representativeness of the AFRM are maximized under routing behaviors that are not overly dynamic or adaptive. Specifically, when road users do not substantially deviate from baseline (established) route choices, or deviate in a rational and moderate manner, AFRM aligns more closely with user-experienced disutility. This observation is consistent with the foundational theory of MFDs. As noted by Geroliminis et al. [65], macroscopic relationships between vehicle accumulation and network production remain valid when traffic control strategies do not induce large-scale rerouting or abrupt behavioral shifts. Such conditions are more representative of real-world behavior, where route choices are typically influenced by limited information, individual preferences, and heterogeneous perceptions of congestion.

Further support for this observation is provided by several other studies in the literature. For instance, Zockaie et al. [58] showed that under emergency conditions, excessively frequent route switching may artificially increase average network flow that is not necessarily accompanied by an increase in network output flow (trip completion rate). Similarly, Knoop et al. [66] concluded that the relationship between traffic production and vehicle accumulation remains valid as long as routing is not substantially modified. Finally, the data-driven study by Mitsakis et al. [67] on a high-intensity storm in Athens in 2013, which represents similarities with the signal tampering case, found that the extreme impacts recorded were a product of both traffic deterioration and user detours.

Other experimental results of this study, namely, the reduced disutility observed when drivers were not exposed to excessive, non-individualized en-route information, are consistent with recent applications of Rational Inattention Theory in traffic modeling [62]. This finding implies that, under digital infrastructure disruption (e.g., signal attacks), traffic managers should rely on optimization tools to design targeted rerouting strategies. In this context, they need to determine which users to inform, the spatial scope of the advisory (e.g., corridor-level vs. area-wide), the guidance form (e.g., route constraints, recommended detours, or probabilistic advice), and the timing of the intervention (e.g., onset, duration, and update frequency), so as to minimize unintended travel time deterioration.

Furthermore, the more pronounced drop in network production in areas of higher traffic intensity (see Table 3) is consistent with findings reported in the literature [9,35]. This provides an additional validation layer for the proposed AFRM and suggests that traffic managers should maintain greater awareness in high-traffic areas.

Overall, the analysis highlights both the potential and the boundaries of macroscopic metrics, such as the AFRM, in reflecting the system-level impacts of digital disruptions. A further discussion of its exploitation potential and incorporation into ITS and traffic management protocols is provided next.

6.2. Exploitation Potential

Regarding the incorporation of the proposed framework and metric into ITS and traffic management processes and protocols, we see two main directions, i.e., traffic planning and traffic operations.

In the context of traffic planning, the framework can support digital vulnerability analyses by identifying traffic control infrastructures, or groups thereof, whose malfunction leads to disproportionate network-wide performance degradation. This includes both ranking individual digital assets according to their criticality and assessing compound disruption scenarios involving multiple controllers or control zones. In this sense, the framework provides a system-wide analog to traditional critical link or node analyses applied to physical infrastructure.

Moreover, the computational efficiency and limited data requirements of AFRM enable its use in scenario-based stress testing and contingency planning. Traffic authorities can apply the framework in microscopic or mesoscopic simulation environments to explore representative combinations of control configurations and digital disruption intensities, without relying on trip-level information. The resulting rankings can then support the assessment and definition of predefined response strategies (i.e., a library of “what-if” measures), such as fallback signal timing plans, safe-mode operation, or controller isolation policies, which can be activated when digital malfunctions are suspected.

It is clarified that by “traffic planning”, we do not refer to long-term disruptions of transport infrastructure and its control logic, as these changes introduce new behaviors, path flows, and network structure, hence compromising the comparability of the respective network productions. The same holds true for permanent mobility measures, such as extended access regulation and pricing schemes, as well as the construction of new transport infrastructure. On that basis, traffic planning should be interpreted as (1) the estimation of short-term impacts of disruptions in traffic control or the deterioration (not complete blockage) of physical infrastructure (e.g., due to extreme weather and temporary work zones) and (2) the preparation of traffic management strategies. In this sense, the proposed framework is intended to support operational and tactical decision-making, rather than long-term strategic planning.

With respect to traffic operations, the framework can serve as a system-level monitoring and decision-support tool within traffic management centers. Since traffic flow and occupancy measurements are routinely collected within many urban networks, AFRM can be computed continuously, or quasi-continuously, and visualized alongside other traffic performance indicators (e.g., travel times, level of service, etc.) or disseminated to navigation service providers through centralized data exchange platforms.

Given that macroscopic flow–density relationships are largely determined by the underlying road infrastructure and its control logic [39,52,68], persistent deviations in AFRM or in the observed macroscopic traffic state may indicate abnormal operating conditions not necessarily related to demand fluctuations on their own. In this role, AFRM can function as an infrastructure-centric indicator of network degradation, complementing intersection-level diagnostics.

If combined with traffic signal logs and controller status data, in the context of the existing data fusion methods reviewed in Section 2 [31,32], AFRM may further contribute to cross-layer situational awareness. In this setting, the metric may not necessarily replace existing cybersecurity intrusion detection systems but can act complementarily by providing network-wide evidence. Such impact-aware monitoring can help distinguish benign anomalies from events that warrant escalation and coordinated response between traffic operators and cybersecurity teams.

This network-level perspective can also support operator prioritization and attention triage, allowing traffic managers to focus on control zones or network partitions exhibiting greater performance loss, rather than reacting to isolated disturbances. In addition, the evolution of the AFRM can inform when to activate or deactivate mitigation measures, such as reverting to fixed-time control, suppressing adaptive features, or applying escalating strategies when disturbances are not resolved.

Finally, the historical records of AFRM may support post-incident investigation and learning, aiding in reconstructing the temporal evolution and spatial footprint of digital disruptions. This may enable the evidence-based refinement of any existing response strategies, protocols, and measures.

6.3. Generalization to Real-World Networks

A limitation of the present study is the use of a stylized, grid-like road network. Although (1) this approach is common in several related studies, (2) steps were taken to enhance network realism (e.g., by introducing signal control programs and rationalizing travel demand), and (3) the network served as a useful testbed for initial exploratory analysis and hypothesis testing, generalization remains a necessary step. This section provides a preliminary assessment of the applicability of the proposed framework and the results that should be expected in more complex, real-world networks.

First, regarding the unimodal nature of real-world networks, we expect that the coexistence of public transport modes (e.g., buses, trams, trolleybuses), active mobility (e.g., micromobility devices, cyclists, pedestrians), and vehicular traffic will exacerbate the impacts of traffic signal tampering scenarios. This is anticipated due to both intensified vehicular and cross-modal interactions, and the fact that traffic signalization regulates the right of way for multiple user groups, including pedestrians, beyond vehicular traffic.

Second, with respect to travel demand, in cases of higher traffic intensity, the impacts of signal tampering attacks are also expected to be more pronounced. Nevertheless, the employed Sioux Falls scenario already represents a highly loaded system; even after demand rationalization (see Section 3), the average volume-to-capacity (V/C) ratio remains at 1.4. This suggests that the simulated conditions closely resemble the peak-demand case. Furthermore, according to existing evidence, network performance exhibits relatively greater marginal sensitivity to signal attack patterns than to the level of traffic demand [34]. Additionally, regarding demand variability in total terms, no methodological modification is foreseen to be necessary, at present, as previous studies show that MFDs are more sensitive to infrastructure characteristics (and traffic control logic thereof) than to traffic demand [39,51,67]. However, in cases of substantial differentiation in mobility patterns (e.g., at the spatial level), it is advisable for traffic managers to maintain and use the appropriate baseline (reference) MFDs.

Third, highly complex network topologies may increase drivers’ rerouting opportunities, potentially weakening the association between user- and infrastructure-centric effects. In practice, however, a high degree of alternative routing is also expected to influence established route choices, thereby moderating the impact of network topology on AFRM. Moreover, the presence of turn restrictions, one-way road infrastructure, and capacity limitations on connecting streets, which are common in real-world networks, is expected to further strengthen the explanatory power of AFRM.

Fourth, with respect to more complex signal zoning for vehicular traffic, it is not straightforward to determine whether the resulting impacts would be greater or not, as this depends heavily on the underlying road infrastructure. For example, when exclusive signal phases for left- and right-turn movements are supported by dedicated turn (pocket) lanes, spillback effects under signal tampering scenarios are expected to be mitigated. In the absence of such configurations, the resulting impacts are likely to be much more severe.

Finally, the large scale of real-world urban networks poses clear implications for the application of the proposed framework. Large-scale networks are a priori not expected to exhibit a single homogeneous MFD. In such cases, traffic managers should apply network partitioning based on traffic homogeneity and spatial compactness criteria. Several existing methodological advancements can support this process [69,70,71,72], drawing on both simulation-based as well as complete or incomplete data-driven approaches. Subsequently, the AFRM should be computed within each partition, also considering the boundary effects of signal malfunctions.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper proposed and tested a framework for analyzing disruptions in digital road transport infrastructure using the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram (MFD). The proposed AFRM offers a practical and quantifiable measure of network-wide performance loss. A key advantage of the metric lies in its operational applicability, as it can be computed using either traffic simulation with relatively shorter loading periods or standard field data, such as from inductive loop detectors, without requiring detailed trajectory- or trip-level information. This reduces the complexity of evaluation and monitoring processes and positions the metric as a useful tool for enhancing traffic managers’ preparedness and real-time response capabilities. These capabilities are particularly relevant given the increasing reliance of modern transport systems on their digital infrastructure components, their growing interdependence with other critical infrastructures such as energy production and distribution systems, and the rising exposure to cyber-related hazards.

The conducted simulation experiments, focusing on multi-scale signal tampering scenarios and varying routing behaviors, showed that AFRM exhibits an acceptable correlation with conventional disutility performance metrics, particularly when road users do not engage in excessively aggressive route switching. While these experiments provided a useful basis for deriving several meaningful insights, we believe that more can be done to enhance the findings’ generalizability, including testing the framework across additional network topologies, behavioral assumptions, and real-world operational conditions.

Looking ahead, a first extension of the current study involves applying the proposed framework to larger, unimodal, and more complex networks. In this context, future work may also examine the behavior of the proposed measure across individual network partitions under varying conditions and scenario settings. These may include heterogeneous signal tampering scenarios, such as the insertion of red phases, removal of selected phases, shuffling of phase durations, or combinations thereof. Further extensions could consider (1) variable tampering intensities, for example, in terms of disruption duration, (2) different levels of accuracy in driver information systems, including cases where these systems are simultaneously manipulated, and/or (3) the presence of adaptive signal control programs and dynamically varying disruptions.

Another promising research direction may be to incorporate the proposed metric into intrusion detection algorithms, building on existing work [31,32]. These algorithms can then be tested in a traffic simulation environment to evaluate their ability to distinguish between recurring traffic disturbances (potentially accompanied by signal adaptations) and deliberate signal manipulations.

A third direction is to formulate the proposed metric using both pMFD and oMFD (Output MFD) approaches [38]. In this setting, the pMFD-based metric (i.e., the AFRM) can reflect the perspective of infrastructure and traffic managers, while the oMFD-based formulation may serve as a benchmark metric, reflecting user-level effects. This dual approach would facilitate a more comprehensive analysis of the stability AFRM across multiple traffic states, due to the enabled ability to isolate these states more effectively. In a similar vein, it would be of interest to explore the use of proxies for trip completion rate, such as the one proposed by Lu et al. [41], in the context of traffic signal or other digital infrastructure disruptions. If successfully implemented, such proxies could elevate the user-centric approach to the level of a direct evaluation metric. A key challenge, though, involves the robust estimation of critical parameters, such as the increase in average trip length under disrupted operating conditions.

Finally, it would be of interest to explore the behavior of the proposed framework under a system-of-systems approach, involving the complete disruption of traffic signal control due to events such as widespread power grid failures. Recent incidents, such as the blackout of 28 April 2025, which affected Spain, Portugal, and southern France, provide a relevant reference point. However, it is anticipated that such extreme scenarios are expected to push the limits of the current simulation and modeling capabilities. Therefore, the co-utilization of surrogate modeling approaches is advisable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.; methodology, C.M.; software, C.M. and A.V.; validation, C.M. and A.V.; formal analysis, C.M.; investigation, C.M.; resources, C.M.; data curation, C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, A.V., E.M. and K.K.; visualization, C.M.; supervision, E.M. and K.K.; project administration, K.K.; funding acquisition, K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Article Processing Charge (APC) was covered by own resources of the Laboratory of Transportation Engineering (School of Rural, Surveying and Geoinformatics Engineering; National Technical University of Athens).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://github.com/bstabler/TransportationNetworks (accessed on 3 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AERTTI | Average en-route travel time increase |

| AFRM | Average Flow Reduction Metric |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ATCRD | Average trip completion rate decrease |

| ATLI | Average time loss increase |

| ATTTI | Average total travel time increase |

| AWTI | Average waiting time increase |

| BPR | Bureau of Public Roads |

| CAVs | Connected and Automated Vehicles |

| DUE | Dynamic User Equilibrium |

| ITS | Intelligent Transport Systems |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| KY ranking | Kemeny–Young ranking |

| MFD | Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram |

| oMFD | Output MFD |

| pMFD | Production MFD |

| UE | User Equilibrium |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-vehicle |

| VANETs | Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks |

References

- Martín, B.; Ortega, E.; Cuevas-Wizner, R.; Ledda, A.; De Montis, A. Assessing Road Network Resilience: An Accessibility Comparative Analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 95, 102851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelder, M.; van Zuylen, H.J.; Immers, L.H. A Framework for Robustness Analysis of Road Networks for Short Term Variations in Supply. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2012, 46, 828–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.E.; Tanner, A. A Community Impact Scale for Regional Disaster Planning with Transportation Disruption. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2022, 23, 04022019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faturechi, R.; Miller-Hooks, E. Measuring the Performance of Transportation Infrastructure Systems in Disasters: A Comprehensive Review. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2015, 21, 04014025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, X.; Chen, A. Performance of transportation network under perturbations: Reliability, vulnerability, and resilience. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 133, 101809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M. Data: Traffic Crashes, Injuries at Stoplights Spiked in Houston Area after Hurricane Beryl. Houston Landing, 21 August 2024. Available online: https://www.houstonlanding.org/data-traffic-crashes-injuries-at-stoplights-spiked-in-houston-area-after-hurricane-beryl (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Fitzgerald, M. Traffic signal outages were a menace after Helene. Here’s why. Greenville Journal, 8 October 2024. Available online: https://greenvillejournal.com/community/traffic-signal-outages-were-a-menace-after-helene-heres-why (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Eyewitness News. All New York City Traffic Lights Affected by Software Problem Now Fixed. ABC7 New York, 11 February 2018. Available online: https://abc7ny.com/post/all-nyc-traffic-lights-affected-by-software-problem-now-fixed/3062127 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Perrine, K.A.; Levin, M.W.; Yahia, C.N.; Duell, M.; Boyles, S.D. Implications of Traffic Signal Cybersecurity on Potential Deliberate Traffic Disruptions. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 120, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M.H.U.; Mohammed, M.A. A Literature Review of Financial Losses Statistics for Cyber Security and Future Trend. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2022, 15, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Arif, T.; Shoab, M. A Statistical and Theoretical Analysis of Cyberthreats and Its Impact on Industries. Int. J. Sci. Res. Comput. Sci. Appl. Manag. Stud. 2018, 7, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Caws, J. 14 Recent Cyber Attacks on the Transport & Logistics Sector. Wisdiam, 29 September 2024. Available online: https://wisdiam.com/publications/recent-cyber-attacks-transport-logistics-sector (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Radauskas, G. Dutch Government will Replace Hackable Traffic Lights to Avoid Movie-Like Carnage. Cybernews, 11 October 2024. Available online: https://cybernews.com/news/dutch-government-will-replace-hackable-traffic-lights (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Pan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, L.; Xia, C.; Olson, D.L. The Impacts of Connected Autonomous Vehicles on Mixed Traffic Flow: A Comprehensive Review. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2024, 635, 129454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Yu, R.; Huang, X.; Jonsson, M.; Bogucka, H.; Gjessing, S.; Zhang, Y. Location Privacy Attacks and Defenses in Cloud-Enabled Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2016, 23, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Z.H.; Smith, B.L.; Fontaine, M.D. Impact of cyberattacks on safety and stability of connected and automated vehicle platoons under lane changes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 150, 105861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tu, Y.; Fan, Q.; Dong, C.; Wang, W. Influence of Cyber-Attacks on Longitudinal Safety of Connected and Automated Vehicles. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 121, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, S.; Sun, W. Analysis and Simulation of Cyber Attacks against Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Connected and Autonomous Driving (MetroCAD), Detroit, MI, USA, 27–28 February 2020; pp. 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, X.; He, X. Modeling and Analyzing Cyberattack Effects on Connected Automated Vehicular Platoons. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 115, 102625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Lyu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Ge, H. Modeling and Stability Analysis of Cyberattack Effects on Heterogeneous Intelligent Traffic Flow. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2022, 604, 127941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, E.P.; Meneguette, R.I.; Alsuhaim, A. An Attacks Detection Mechanism for Intelligent Transport System. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–13 December 2020; pp. 2453–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellitto, G.P.; Masi, M.; Pavleska, T.; Aranha, H. A Cyber Security Digital Twin for Critical Infrastructure Protection: The Intelligent Transport System Use Case. In Proceedings of the IFIP Working Conference on the Practice of Enterprise Modeling, Cham, Switzerland, 24–26 November 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 230–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škorput, P.; Vojvodić, H.; Mandžuka, S. Cyber Security in Cooperative Intelligent Transportation Systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium ELMAR, Zadar, Croatia, 18–20 September 2017; pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedjelmaci, H.; Hadji, M.; Ansari, N. Cyber Security Game for Intelligent Transportation Systems. IEEE Netw. 2019, 33, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Alasiry, A.; Marzougui, M.; Bayhan, I.; Kuna, S.S.; Rao, G.S.N.; Aldossary, H. Securing intelligent transportation systems: A dual-framework approach for privacy protection and cybersecurity using generative AI. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. Early Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazid, M.; Singh, J.; Pandey, C.; Sherratt, R.S.; Das, A.K.; Giri, D.; Park, Y. Explainable deep learning-enabled malware attack detection for IoT-enabled intelligent transportation systems. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 7231–7244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamssaggad, A.; Benamar, N.; Hafid, A.S.; Msahli, M. A Survey on the Current Security Landscape of Intelligent Transportation Systems. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 9180–9208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.; Chen, H.; Zhao, X.; Wu, G.; Feng, Y. Cybersecurity on Connected and Automated Transportation Systems: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 1382–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelarestaghi, K.B.; Foruhandeh, M.; Heaslip, K.; Gerdes, R. Intelligent Transportation System Security: Impact-Oriented Risk Assessment of In-Vehicle Networks. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2019, 13, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, C.W. Cybersecurity in the Age of Autonomous Vehicles, Intelligent Traffic Controls and Pervasive Transportation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Long Island Systems, Applications and Technology Conference (LISAT), Farmingdale, NY, USA, 5 May 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Naha, R.; Kaisar, S.; Khoshkholghi, M.A.; Ali, K.; Galletta, A. Information Fusion-Based Cybersecurity Threat Detection for Intelligent Transportation System. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ACM 23rd International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing Workshops (CCGridW), Bangalore, India, 1–4 May 2023; pp. 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, A.; Karmakar, G.; Kamruzzaman, J.; Das, R.; Newaz, S.S. An Evidence Theoretic Approach for Traffic Signal Intrusion Detection. Sensors 2023, 23, 4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laszka, A.; Potteiger, B.; Vorobeychik, Y.; Amin, S.; Koutsoukos, X. Vulnerability of transportation networks to traffic-signal tampering. In Proceedings of the 2016 ACM/IEEE 7th International Conference on Cyber-Physical Systems (ICCPS), Vienna, Austria, 11–14 April 2016; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thodi, B.T.; Mulumba, T.; Jabari, S.E. Noticeability versus impact in traffic signal tampering. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 86149–86161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganin, A.A.; Mersky, A.C.; Jin, A.S.; Kitsak, M.; Keisler, J.M.; Linkov, I. Resilience in intelligent transportation systems (ITS). Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 100, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comert, G.; Pollard, J.; Nicol, D.M.; Palani, K.; Vignesh, B. Modeling cyber attacks at intelligent traffic signals. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, Q.A.; Liu, H.X.; Mao, Z.M. Vulnerability of Traffic Control System under Cyberattacks with Falsified Data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, L.; Paipuri, M. Macroscopic Traffic Dynamics under Fast-Varying Demand. Transp. Sci. 2019, 53, 1526–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taillanter, E.; Schadschneider, A.; Barthelemy, M. Structure of Road Networks and the Shape of the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram. Phys. Rev. E 2024, 109, 014314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.; Knoop, V.L. Hysteresis and the Unobserved Congestion Branch in the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram: Theoretical Considerations and Modeling. J. Adv. Transp. 2023, 2023, 8797109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.L.; Sun, W.; Dai, J.; Schmöcker, J.D.; Antoniou, C. Traffic Resilience Quantification Based on Macroscopic Fundamental Diagrams and Analysis Using Topological Attributes. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 247, 110095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.L.; Sun, W.; Lyu, C.; Schmöcker, J.D.; Antoniou, C. Post-Disruption Lane Reversal Optimization with Surrogate Modeling to Improve Urban Traffic Resilience. Transp. Res. Part B 2025, 197, 103237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, N.; Seppecher, M.; Leclercq, L. Scaling Methods for Estimating Macroscopic Fundamental Diagrams in Urban Networks with Sparse Stationary Sensor Coverage. Transp. Res. Part. C 2025, 178, 105213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Ka, E.; Feng, Y.; Ukkusuri, S.V. Network Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram-Informed Graph Learning for Traffic State Imputation. Transp. Res. Part B 2024, 189, 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Lee, E. Congestion Boundary Approach for Phase Transitions in Traffic Flow. Transp. B 2024, 12, 2379377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.B.; Rego, P.A.; Carneiro, T.; Rodrigues, J.D.C.; Reboucas Filho, P.P.; De Souza, J.N.; Chamola, V.; De Albuquerque, V.H.C.; Sikdar, B. Computation Offloading for Vehicular Environments: A Survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 198214–198243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Fang, M.; Li, H.; Li, X. RSU-Assisted Traffic-Aware Routing Based on Reinforcement Learning for Urban VANETs. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 5733–5748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakirov, A.; Fourie, P.J. Enriched Sioux Falls Scenario with Dynamic and Disaggregate Demand. Arbeitsberichte Verk. Raumplan. 2014, 978, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Taylor, J. DTALite: A Queue-Based Mesoscopic Traffic Simulator for Fast Model Evaluation and Calibration. Cogent Eng. 2014, 1, 961345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transportation Research Board. Highway Capacity Manual; National Research Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, F.V. Traffic Signal Settings; Road Research Technical Paper No. 39; Road Research Laboratory: London, UK, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Geroliminis, N.; Daganzo, C.F. Existence of Urban-Scale Macroscopic Fundamental Diagrams: Some Experimental Findings. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2008, 42, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroliminis, N.; Sun, J. Properties of a well-defined macroscopic fundamental diagram for urban traffic. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2011, 45, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambühl, L.; Loder, A.; Bliemer, M.C.; Menendez, M.; Axhausen, K.W. A Functional Form with a Physical Meaning for the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2020, 137, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvelas, A.; Saeedmanesh, M.; Geroliminis, N. Enhancing Model-Based Feedback Perimeter Control with Data-Driven Online Adaptive Optimization. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2017, 96, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Haddad, J.; Geroliminis, N. Dynamics of Heterogeneity in Urban Networks: Aggregated Traffic Modeling and Hierarchical Control. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2015, 74, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yeo, H. Evaluating Link Criticality of Road Network Based on the Concept of Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2017, 13, 162–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zockaie, A.; Mahmassani, H.S.; Saberi, M.; Verbas, Ö. Dynamics of Urban Network Traffic Flow During a Large-Scale Evacuation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2422, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemeny, J.G. Mathematics Without Numbers. Daedalus 1959, 88, 577–591. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20026529 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Almotahari, A.; Yazici, A. Impact of Topology and Congestion on Link Criticality Rankings in Transportation Networks. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 87, 102529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Mahmassani, H.S.; Alfelor, R.; Chen, Y.; Hou, T.; Jiang, L.; Zockaie, A. Implementation and Evaluation of Weather-Responsive Traffic Management Strategies: Insight from Different Networks. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2396, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taale, H.; Westerman, M. The Application of Sustainable Traffic Management in the Netherlands. In Proceedings of the European Transport Conference 2005, Strasbourg, France, 3–5 October 2005; Association for European Transport: Strasbourg, France, 2005; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.; Liu, R. A Generalized Rationally Inattentive Route Choice Model with Non-Uniform Marginal Information Costs. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2024, 189, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesone, A.; Tettamanti, T.; Varga, B.; Bifulco, G.N.; Pariota, L. Multiobjective model predictive control based on urban and emission macroscopic fundamental diagrams. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 52583–52602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroliminis, N.; Haddad, J.; Ramezani, M. Optimal Perimeter Control for Two Urban Regions with Macroscopic Fundamental Diagrams: A Model Predictive Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2012, 14, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoop, V.L.; Hoogendoorn, S.P.; Van Lint, J.W.C. Routing Strategies Based on Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram. Transp. Res. Rec. 2012, 2315, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsakis, E.; Stamos, I.; Diakakis, M.; Salanova Grau, J.M. Impacts of High-Intensity Storms on Urban Transportation: Applying Traffic Flow Control Methodologies for Quantifying the Effects. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 11, 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.; Wong, S.C.; Liu, H.X. Network Topological Effects on the Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram. Transp. B Transp. Dyn. 2021, 9, 376–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Geroliminis, N. On the Spatial Partitioning of Urban Transportation Networks. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2012, 46, 1639–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambühl, L.; Loder, A.; Zheng, N.; Axhausen, K.W.; Menendez, M. Approximative Network Partitioning for MFDs from Stationary Sensor Data. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Hu, X.; Chen, X. A Network Partitioning Algorithmic Approach for Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram-Based Hierarchical Traffic Network Management. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 19, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubota, T.; Bhaskar, A.; Chung, E. Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram for Brisbane, Australia: Empirical Findings on Network Partitioning and Incident Detection. Transp. Res. Rec. 2014, 2421, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.