Abstract

Knowledge graphs (KGs) offer a structured and collaborative approach to integrating diverse knowledge from various domains. However, constructing knowledge graphs typically requires significant manual effort and heavily relies on pretrained models, limiting their adaptability to specific sub-domains. This paper proposes an innovative, efficient, and locally deployable knowledge graph construction framework that leverages low-rank adaptation (LoRA) to fine-tune large language models (LLMs) in order to reduce noise. By integrating iterative optimization, consistency-guided filtering, and prompt-based extraction, the proposed method achieves a balance between precision and coverage, enabling the robust extraction of standardized subject–predicate–object triples from raw long texts. This makes it highly effective for knowledge graph construction and downstream reasoning tasks. We applied the parameter-efficient open-source model Qwen3-14B, and experimental results on the SciERC dataset show that, under strict matching (i.e., ensuring the exact matching of all components), our method achieved an F1 score of 0.358, outperforming the baseline model’s F1 score of 0.349. Under fuzzy matching (allowing some parts of the triples to be unmatched), the F1 score reached 0.447, outperforming the baseline model’s F1 score of 0.392, demonstrating the effectiveness of our approach. Ablation studies validate the robustness and generalization potential of our method, highlighting the contribution of each component to the overall performance.

1. Introduction

Knowledge graphs (KGs) [1,2,3] are structured representations that organize interconnected knowledge in graph form, where entities and relations are modeled as nodes and edges, respectively. KGs have been widely applied to downstream tasks such as decision support [4], question answering [5,6], and recommendation systems [7,8]. However, constructing KGs remains challenging, as it requires integrating syntactic and semantic understanding to produce consistent, concise, and meaningful graph structures, while still relying heavily on manual effort [9].

Meanwhile, the rapid development of generative large language models (LLMs) is driving an unprecedented technological transformation. AI systems, represented by GPT-3.5, have demonstrated strong abilities in language analysis, processing, and understanding, accelerating progress across numerous application domains. LLMs reshape the ways in which humans acquire and interpret information: users can express queries in natural language and obtain coherent, reliable, context-aware responses, enabling more seamless human–machine interaction. Their capabilities extend beyond language processing and lay the groundwork for future human–AI collaborative innovation in fields such as technological development, healthcare, and creative industries.

Similarly to traditional machine learning models that require large-scale data for supervised prediction tasks, LLMs are pretrained on massive corpora and can perform natural language generation and reasoning under prompt guidance. Due to the diversity of their outputs, prompt engineering has emerged as a key research direction. By designing effective prompts, researchers can build novel algorithmic tools, improve existing tasks, and generate high-quality synthetic data, reducing the cost of data collection and annotation. These prompt-based techniques have become central to applications including creative content generation, information retrieval, problem solving, and summarization.

Recent research on automated knowledge graph construction (KGC) [9,10] has increasingly leveraged LLMs due to their strong natural language understanding and generation capabilities. LLM-based KGC approaches employ innovative prompting strategies such as multi-turn conversation [11] and code generation [12] to extract entity–relation triples. Despite these advances, existing methods still suffer from limited generalization abilities and often require domain-specific prompt engineering. Ensuring the validity of generated triples typically requires assuming that the LLM’s internal knowledge is sufficiently complete or explicitly encoding schema information within prompts. This may lead to overly sophisticated prompt designs or exceeding the context window in complex scenarios. Additionally, the extracted triples frequently contain redundant information—for example, metadata such as paper authors may be irrelevant when constructing a welding domain KG. These issues hinder cross-domain flexibility.

To address such limitations, this work proposes an automated KGC framework capable of efficiently and accurately extracting triples from the scientific literature. The framework leverages a systematic, multi-module collaborative design to compensate for the shortcomings of LLMs in domain-specific applications. The primary contributions of the paper are summarized as follows:

- -

- To address the insufficient recall of single-pass extraction, where certain relations are difficult to capture, the proposed framework performs initial extraction without prior knowledge and then automatically injects entities and relations obtained in the previous iteration as prompts in subsequent rounds. This iterative refinement of the LLM’s outputs improves the recall while minimally sacrificing fidelity.

- -

- To mitigate contamination of the knowledge graph by hallucinated triples that are not supported by the source text or are produced via commonsense-like associative reasoning, the framework enforces a standardized JSON output format and combines it with vector-based alignment to the original text for instance-level verification. This design effectively suppresses hallucinations and incorrect triples.

- -

- To alleviate redundancy in the extracted triples, the framework applies LoRA-based fine-tuning to the key linear layers in the attention and feed-forward modules of the LLM. This strikes a balance between the number of trainable parameters and the final performance, enabling the rapid construction of literature extractors across diverse scientific domains while reducing redundant triples as much as possible.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the main methods used in knowledge graph construction. Section 3 presents the overall methodology of LECITE, including the denoising module, information extraction module, triplet filtering module, and iterative refinement module. Section 4 discusses the experimental results and ablation studies, providing a detailed analysis of the model’s performance and effectiveness. Finally, the paper concludes with a summary of the main methods and a discussion of potential future research directions.

2. Related Work

As a structured form of knowledge representation, knowledge graphs (KGs) have been widely applied in question answering, recommendation, and decision support. Traditional KG construction methods typically follow a pipeline paradigm [13,14,15], decomposing the process into several subtasks. For instance, in the entity discovery subtask, Žukov-Gregoric et al. [16] proposed a novel parallel recurrent neural network architecture for named entity recognition (NER), whose core idea is to use multiple small LSTMs in parallel to process the same input, instead of a single large LSTM, thereby reducing the number of parameters while improving the performance. Martins [17] later introduced an end-to-end model that jointly trains NER and entity linking, performing named entity recognition and entity linking to a knowledge base simultaneously. This enables the model not only to recognize entities but also to directly link them to a knowledge base, allowing the two tasks to share representations and mutually enhance each other.

In the context of entity typing, Choi et al. [18] proposed a new entity typing task that moves beyond coarse-grained label categories. Their model predicts, for any nominal phrase, a set of fine-grained types expressed in natural language based on contextual information, thereby providing more precise type signals for downstream tasks through contextually appropriate natural language type phrases. Onoe and Durrett [19] subsequently proposed an entity disambiguation system that does not rely on entity-linking annotations in the target domain. To address entity type ambiguity, their method feeds sentences into a trained model to obtain probability distributions over types and uses multiple contextual keywords to determine probability scores for candidate entities, thus completing entity type recognition.

KG construction also involves a relation classification subtask, for which a number of classic methods have been proposed. Zeng et al. [20] were among the first to apply convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in an end-to-end fashion to relation classification, enabling the model to learn features directly from raw sentences via CNNs. Subsequent approaches, such as BERT-based models and CNNs combined with attention mechanisms, have generally taken this work as a strong baseline.

With the development of pretrained generative models, more recent studies have reformulated KG construction as a sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) problem. Raffel et al. [21] proposed a text-to-text framework that treats all natural language processing tasks as mapping from input text to output text, and they demonstrated that encoder–decoder architectures yield the best performance. BART [22] is another influential pretrained model that combines a bidirectional encoder, similar to BERT, with an autoregressive decoder, similar to GPT, to form a denoising autoencoder framework. By corrupting input text and training the model to reconstruct the original text, BART supports both text understanding and text generation, thereby improving the language modeling capabilities in both directions. These pretrained generative models have encouraged a growing body of work that casts KG construction as a seq2seq problem, using language models to generate relation triples in an end-to-end manner.

Owing to their strong natural language understanding and generation capabilities, large language models (LLMs) have further catalyzed progress in KG construction and are now widely adopted in this area. Recent work [10] explores the use of LLMs to automate KG construction by exploiting zero-shot or few-shot prompting strategies that guide LLMs to extract entity–relation triples from text. For example, ChatIE [11] reformulates information extraction as a multi-turn question-answering process based on a KG-driven, continual reasoning mechanism. Rather than simply feeding the current user query to the LLM at each turn, the system first constructs a dynamic context representation from the dialog history, performs coreference resolution and entity linking to identify the current “focus entity”, and then conducts traceable path reasoning over the KG—e.g., multi-hop traversal along relation edges using attention-based or reinforcement learning-based policies—to extract new subgraphs that are relevant to the focus entity and logically consistent with previous turns. The resulting subgraph representation is then jointly encoded with the current query and decoded into a natural language answer. This iterative process allows the system to maintain semantic coherence and knowledge consistency across turns, multi-hop relations, and dynamically evolving entity states, thereby realizing interactive “converse-and-reason” behavior.

Other work has proposed code generation-based approaches [12], which also generate triples but treat KG construction as a code synthesis problem. In this paradigm, entities and relations are encapsulated into executable pseudo-code templates using Python class definitions. The natural language text is converted into this code format and fed to a code language model, which completes the program by generating statements such as Triple(…). The generated code is then parsed back into triples, enabling the model to leverage the syntactic slots and structural constraints of code to accurately extract overlapping or long-distance entity–relation pairs.

As discussed above, however, these methods are typically confined to small-scale, domain-specific scenarios. To ensure the validity of the generated triples, schema information (e.g., possible entity and relation types) must often be injected into the prompts. For complex datasets such as Wikipedia, the large schemas required frequently exceed the context windows of current LLMs [23], and predefined schemas are not always available. To mitigate this, some studies compress the traditional two-stage pipeline of “entity recognition followed by relation classification” into a single end-to-end text generation step. In this line of work, triples in the training data are linearized into list-style natural language strings, such as “[(Bill Nelson: person, works_for, NASA: organization)]”, and paired with the original sentences to form input–output templates. At inference time, a small number of examples (typically around a dozen) are concatenated into a prompt and fed to models such as GPT-3 or Flan-T5, which then continue the sequence in the same list format using their language modeling capabilities. Leveraging strong semantic and format generalization, the model can generate syntactically well-formed strings with correct entities and relations, even for unseen sentences.

To further improve performance, some work first uses GPT-3 to automatically generate chain-of-thought-style intermediate reasoning for the training set (e.g., “X is the CEO of Y; therefore, there exists a ‘works_for’ relation”) and then jointly supervises a smaller Flan-T5 model with both the reasoning chains and the target triples. During decoding, the model is guided by both labels and reasoning, and the resulting strings can be parsed into structured triples using simple regular expressions. This pipeline avoids explicit NER and relation classification annotations, as well as cascading errors, and, by combining LLM generation, prompt engineering, and reasoning distillation, it can achieve F1 scores that are comparable to or even surpass those of fully supervised models in zero-/few-shot settings.

Despite their strong performance on small-scale, domain-specific datasets, these methods often struggle to produce consistent and concise KGs in the absence of predefined schemas, and the extracted results can still suffer from redundancy, ambiguity, or schema inconsistency.

To alleviate these issues, some studies introduce Open Information Extraction (OpenIE) strategies to extract triples without relying on predefined schemas. However, OpenIE methods typically exhibit semantic redundancy and relation ambiguity. To address this, schema canonicalization techniques have been proposed to semantically aggregate extracted relations and unify their representations. For example, CESI utilizes external knowledge sources (e.g., WordNet) and embedding-based clustering to canonicalize relations, but it can be prone to erroneous overgeneralization. More recent work instead tends to use LLMs to generate contextual definitions of relations and then perform matching and transformation based on semantic similarity, thereby improving the canonicalization accuracy.

To further enhance the extraction quality, some methods incorporate retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) mechanisms that dynamically retrieve schema elements relevant to the input text before extraction. For instance, EDC [24] proposes a three-stage framework—Extract, Define, Canonicalize—and trains a schema retriever to improve the LLM’s ability to handle complex schemas. Experimental results show that this framework achieves strong performance both in settings with predefined schemas and in schema-free scenarios.

Iterative extraction pipelines can be viewed as sequential generation procedures in which intermediate outputs (e.g., extracted entities/relations) condition subsequent steps, potentially inducing error compounding when early mistakes shift the model to off-distribution states. Pozzi et al. [25] analyze this issue in the context of large language model distillation, attributing degraded free-running generation to exposure bias caused by the mismatch between next-token prediction training and autoregressive inference. They further relate exposure bias to the distributional shift problem in imitation learning and propose an imitation learning-inspired mitigation strategy by integrating Dataset Aggregation and Data as Demonstrator into the distillation framework. Conceptually, this perspective strengthens the grounding of iterative extraction/feedback loops by highlighting how verification, correction signals, and iterative refinement can reduce drift and suppress self-reinforcing errors across iterations.

In summary, prior work has advanced KG construction from traditional pipeline models to seq2seq generation and LLM-based prompting, with additional improvements via code-structured decoding, OpenIE-style schema-free extraction, relation canonicalization, and retrieval-augmented schema grounding. Nevertheless, existing approaches still face challenges in schema-free or complex schema settings, including noisy extractions, redundancy and inconsistency in the resulting KGs, and error compounding in iterative generation and feedback loops. Motivated by these limitations, our work combines LoRA-based adaptation with an iterative refinement and verification strategy to improve the lextraction accuracy, coverage, and consistency under both exact and fuzzy evaluation settings.

3. Method

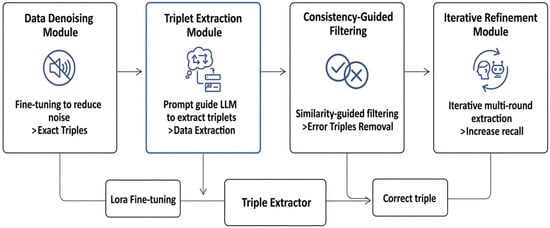

In this work, we propose a method for constructing knowledge graphs in a structured manner using large language models. We first present the overall framework in detail. Given an input text, our core objective is to generate relation triples in a predefined format such that the resulting knowledge graph, constructed from these triples, exhibits minimal ambiguity and redundancy. Furthermore, we require all extracted triples to strictly follow the specified output schema, and, on this basis, we aim to maximize the extraction accuracy. The overall framework is illustrated in Figure 1. The proposed triple extractor consists of the following key modules.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed framework, which consists of four components. The data denoising module enhances the domain adaptation ability of the large language model via LoRA-based fine-tuning. The fine-grained prompt-based extraction module combines LoRA weights with the base model to form a reliable triple extractor. The consistency-guided triple filtering module filters out incorrect triples based on semantic similarity. The iterative refinement module performs multi-round extraction to improve the recall of the extracted triples.

- -

- Data denoising module. This module reduces noise from irrelevant content during triple extraction via model fine-tuning, yielding a more accurate extractor.

- -

- Fine-grained prompt-based extraction module. This module decomposes the extraction task into substeps and guides the large language model through carefully designed prompts to perform step-by-step triple extraction.

- -

- Consistency-guided triple filtering module. This module employs similarity-based matching to identify and filter out incorrect triples, thereby enforcing semantic consistency between the extracted triples and the source text.

- -

- Iterative refinement module. This module iteratively refines the LLM’s extraction results, improving both the precision and recall of the triples that constitute the final knowledge graph.

3.1. Data Sources

The primary objective of this study is to construct a knowledge graph from the scientific literature. To more accurately calibrate the model during the fine-tuning stage and thereby improve the accuracy of triple extraction, we use domain-specific scholarly articles as the source of our fine-tuning data. Specifically, we collect several research papers in the welding domain, segment them into multiple text passages, and manually identify the triples of interest. These passage–triple pairs are then assembled into our fine-tuning dataset. The dataset follows an input–output format: the input is the text span from which we expect the model to extract triples, and the output is the set of target triples that should be extracted from this span.

3.2. Data Denoising Module

Although large language models are, in principle, capable of extracting schema-compliant triples from text, our extractor is primarily intended for use on domain-specific corpora. Since most general-purpose LLMs are not exposed to such specialized data during pretraining, their out-of-the-box extraction performance on these domains can be suboptimal. To improve the quality of the extracted triples, we therefore fine-tune the base models to better align them with the target task.

We adopt Mistral-7B [26], Qwen3-7B [27], and Qwen3-14B as our base models. These are publicly available, widely used general-purpose LLMs. For parameter-efficient fine-tuning, we employ low-rank adaptation (LoRA) [28], which inserts trainable low-rank matrices into the key linear transformations of Transformer layers, rather than directly updating the original weights. This design allows the model to quickly adapt to domain-specific requirements while preserving the broad linguistic and world knowledge acquired during large-scale pretraining.

The fine-tuned models are used to improve knowledge graph construction by focusing on the accurate extraction of entities and relations while suppressing redundant semantics. For instance, when constructing a knowledge graph from a welding-related paper, domain-specific technical concepts are emphasized, whereas metadata such as author names and affiliations can be safely discarded. This selective extraction enables the efficient construction of domain-specific knowledge graphs tailored to the scientific literature.

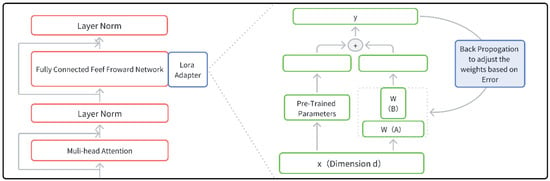

For data processing, we construct supervised samples in JSONL format and use a fixed template to concatenate the user input and model output into a single sequence, which is then tokenized using the official tokenizer of each base model. During label construction, only the output segment corresponding to the model’s generation is supervised. After training, we store only the LoRA weights; at inference time, the extractor is deployed by loading the base model together with the LoRA adapter, which can be merged or composed at runtime. The framework is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the insertion position and update mechanism of LoRA within a Transformer layer. The left part shows a typical layer structure composed of multi-head attention, a feed-forward network, and layer normalization, where the LoRA adapter is injected into the key linear transformations. The right part depicts how low-rank matrices A and B parameterize incremental updates over the pretrained weights: during backpropagation, only the LoRA branch is updated while the original model weights remain frozen, thereby enabling efficient domain-specific adaptation with a significantly reduced number of trainable parameters.

3.3. Fine-Grained Prompt-Based Extraction Module

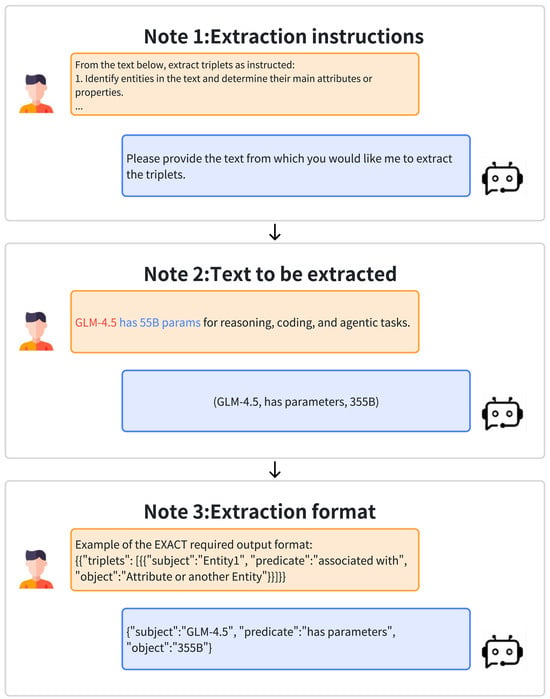

In this stage, we leverage the domain-adapted LLM obtained from the previous fine-tuning step to perform triple extraction. Given an input text span, we design a small set of task-specific prompts that instruct the model to (i) identify salient entities and relations and (ii) output the corresponding triples in a strictly predefined format. Specifically, the prompt specifies the required schema (subject, predicate, object) and output constraints (e.g., JSON-style list or line-based triples), so that the model’s generation can be directly parsed into structured data without additional post-processing. The issue is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Illustration of a complete prompting workflow in the fine-grained prompt-based extraction module. The process consists of three stages: in Note 1, natural language extraction instructions are provided, asking the model to identify entities and their attributes from the input text and extract corresponding relation triples; in Note 2, the raw text to be processed is supplied, enabling the fine-tuned LLM to perform semantic recognition and triple extraction conditioned on the instructions; finally, Note 3 specifies a strict JSON-style output template with subject, predicate, and object fields, guiding the model to return the extracted triples in a unified, machine-parsable structured format.

The extracted triples produced by this module are then fed into the subsequent stages of the pipeline, where they are further validated and refined by the consistency-guided filtering and iterative refinement modules.

3.4. Consistency-Guided Triple Filtering Module

To further enhance the extraction quality, we introduce a consistency-guided triple filtering module that treats the raw LLM outputs as candidates and performs posterior screening and cross-round aggregation. The core idea is to leverage structural checks and vector-based semantic similarity (e.g., cross-encoder scores, Jaccard similarity, and embedding similarity) to filter out incorrect or noisy triples and retain only those that are well supported by the source text.

Firstly, structural validity checking and denoising are applied. The model outputs are robustly parsed (with regular expression fallback when necessary), and each triple is checked for completeness and type correctness. We verify that the subject, predicate, and object fields are non-empty; normalize their formatting (e.g., trimming whitespace); and remove malformed items. Only structurally valid triples that conform to the predefined output schema are passed to the next step.

Secondly, we perform semantic consistency verification. Using the source document or validation passage as evidence, the text is segmented into sentences and indexed in an embedding space. For each candidate triple, we retrieve the most relevant sentences and compute similarity scores; only triples whose semantics are consistent with the contextual evidence are retained. Triples that cannot be grounded in the text, or that arise from hallucinations or ambiguous interpretations, are explicitly discarded.

Thirdly, we introduce prior-based relation constraints and cross-round aggregation. Relations that have already passed filtering in previous rounds are used as priors. A BERT-style encoder is employed to select the Top-K most informative relations from a relation vocabulary, forming a compact candidate set that is preferentially used during subsequent generations, thereby reducing noise before posterior filtering. Across rounds, we aggregate triples by deduplicating over the (subject, predicate, object) key and merging semantically equivalent variants via alias normalization.

For example, given the input ”In our experiment, we synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles by a sol–gel method and annealed them at 500 °C for 2 h. XRD patterns confirm the anatase phase. The average crystallite size is 18 nm, and the band gap is 3.2 eV”. The LLM may initially produce:

(TiO2 nanoparticles, annealed_at, 500 °C)

(TiO2 nanoparticles, phase, anatase)

(TiO2 nanoparticles, crystallite_size, 18 nm)

(TiO2 nanoparticles, band_gap, 3.2 eV)

(TiO2, band_gap, 3.2 eV)

(TiO2 nanoparticles, phase, rutile)

After filtering, the module (i) keeps only structurally complete triples (thus discarding the highlighted incomplete triple), (ii) removes the “phase rutile” triple due to a lack of textual support (the text explicitly states anatase), and (iii) treats the fourth and fifth triples as semantically equivalent and merges them via alias resolution (e.g., “TiO2 nanoparticles” vs. “TiO2”). In this way, the consistency-guided filtering module suppresses hallucinated and redundant triples, substantially improving the precision and overall quality of the final triple set.

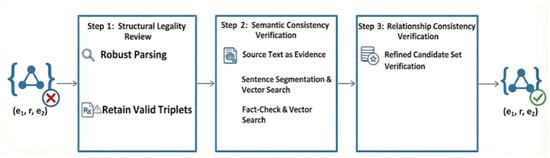

3.5. Iterative Refinement Module

After consistency-guided filtering, we further employ an iterative refinement module that repeatedly updates the candidate triple set by feeding back previously extracted entities and relations into the LLM. In each iteration, entities and relations from the previous round are treated as priors and injected into the new prompt as candidate subjects/objects and predicates. This prior-enhanced prompting forms a closed loop of multi-round generation → consistency filtering → prior reinforcement → cumulative aggregation, which gradually improves both the coverage and precision of open information extraction. The framework is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Consistency-guided triple filtering pipeline. In Step 1, candidate triples generated by the LLM undergo structural legality review, where robust parsing and field completeness checks are applied to retain only well-formed triples. In Step 2, semantic consistency is verified using the source text as evidence: sentences are segmented and searched in an embedding space to fact-check each triple against its contextual support. In Step 3, the remaining candidates are further screened via relationship consistency verification within a refined relation space, yielding high-confidence triples that are simultaneously consistent in structure, semantics, and relations.

In the initial round, the model performs extraction without any prior knowledge; the resulting triples are formatted, deduplicated, and verified for structural and semantic consistency and then stored as the initial result set. In subsequent rounds, we infer the current entity and relation sets from the latest results, construct a new prompt conditioned on these priors, optionally refine the relation space using a domain encoder to retrieve the Top-K relations from a predefined vocabulary, and let the LLM generate new triples under this enriched prompt. The new triples are again deduplicated, consistency-verified, filtered for validity, and accumulated into the global result set until a stopping criterion (e.g., marginal gain in new valid triples) is met. A pseudo-code description is given in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Iterative triple extraction with prior-enhanced prompting | |

| 1: | Initialize , |

| 2: | Round 0: extraction without priors |

| 3: | |

| 4: | |

| 5: | append to |

| 6: | |

| 7: | Subsequent rounds: prior-enhanced extraction |

| 8: | while not check_stop_condition() do |

| 9: | |

| 10: | |

| 11: | |

| 12: | |

| 13: | |

| 14: | |

| 15: | |

| 16: | |

| 17: | |

| 18: | end while |

| 19: | return |

In practice, we observe that, across iterations, the predicate space progressively converges under the guidance of priors, hallucinated triples are suppressed, and previously missed but text-supported relations are gradually recovered, yielding a more complete and less redundant triple set for downstream knowledge graph construction.

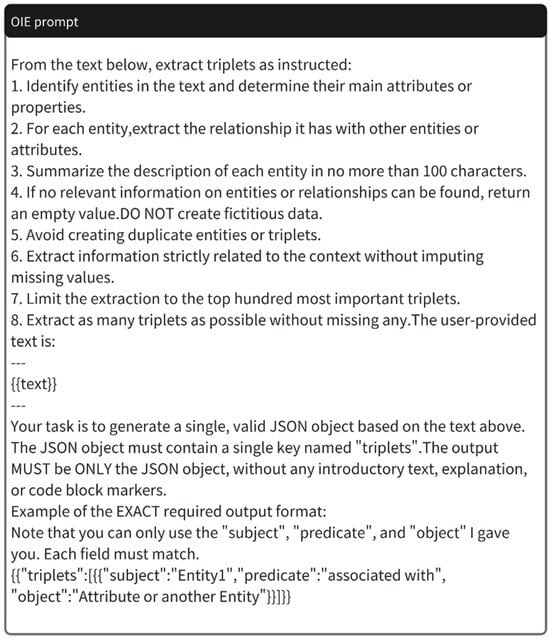

3.6. Open Information Extraction Prompt

As shown in Figure 5, we design a structured instruction prompt for LLM-based open information extraction. The prompt guides the model to identify entities and their main attributes, extract relations between entities, avoid duplicate or hallucinated triplets, and restrict the output to at most one hundred informative triplets. The model is further required to return a single valid JSON object with a single key “triplets”, where each element follows the {“subject”, “predicate”, “object”} schema. This design allows the extracted triples to be directly parsed and integrated into our knowledge graph construction pipeline.

Figure 5.

Prompt template used for open information extraction (OIE). The instruction asks the LLM to (1) detect entities and their attributes, (2) extract relationships between entities, (3) avoid fictitious or duplicate triplets, (4) limit the output to the most important triplets, and (5) return a single JSON object containing a list of subject–predicate–object triplets that strictly follow the specified format.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

The evaluation of the extraction task is designed with a focus on three principal aspects: (1) accuracy—minimizing incorrect extractions (false positives); (2) coverage—minimizing missed but should-be-extracted triples (false negatives); (3) consistency and usability—reducing redundancy under the same subject, stabilizing predicate expressions, and facilitating the downstream use of the constructed knowledge graph. All experiments are conducted on a server equipped with two NVIDIA A100 GPUs (80 GB VRAM each), with CUDA version 12.4.

In addition, our fine-tuning adopts LoRA via the PEFT implementation for causal language modeling (TaskType.CAUSAL_LM). LoRA adapters are injected into the Transformer projection modules q_proj, k_proj, v_proj, and o_proj (attention), as well as gate_proj, up_proj, and down_proj (MLP). The LoRA rank is set to , with scaling factor and dropout (training mode: inference_mode=False). Fine-tuning is performed for 11 epochs with a per-device batch size of 1 and gradient accumulation steps of 4 (effective batch size ). The learning rate is . We enable gradient checkpointing to reduce memory usage, log training metrics every 10 steps, and save model checkpoints at every step (save_steps=1).

Based on these considerations, we adopt the F1-score as the primary evaluation metric. F1-score is a widely used comprehensive metric in machine learning and natural language processing; it combines precision and recall via the harmonic mean to balance two types of errors (false positives and false negatives), and it is particularly suitable for tasks with imbalanced label distributions or where both accuracy and the coverage of positive instances are important.

Formally, the F1-score is defined as:

where

and

Precision measures the proportion of extracted triples that are actually correct, reflecting the reliability of the results, while recall measures the proportion of gold triples that are successfully extracted, reflecting the coverage of the model. The F1-score ranges within [0, 1], with higher values indicating better overall performance. In this study, we use F1-score as the core evaluation metric to comprehensively assess the stability and robustness of the proposed method on the triple extraction task.

4.2. Comparative Experiments

4.2.1. Datasets

We conduct experiments on one public benchmark dataset and one in-house dataset. The public dataset is SciERC, a scientific information extraction corpus released by Luan et al. [29] in 2018. SciERC contains annotated scientific entities, their relations, and coreference clusters over 500 scientific abstracts, which are drawn from 12 AI conferences and workshops spanning four artificial intelligence communities in the Semantic Scholar Corpus.

In addition, we construct a domain-specific private dataset based on several welding-related scientific articles. Specifically, we manually segment the papers into paragraphs and annotate the corresponding target relation triples, organizing the data in a supervised fine-tuning (SFT) format, where each instance consists of an input paragraph and its associated output triple set. This private welding corpus is used to evaluate the effectiveness of our method in a realistic, domain-specific scientific literature scenario.

4.2.2. Experimental Results

Table 1 reports the performance of the proposed method on the SciERC dataset under two evaluation settings, namely exact matching and fuzzy (relaxed) matching. In the exact matching setting, a predicted triple is counted as correct only if its subject, predicate, and object all exactly match those of a gold triple; minor surface-form variations such as trivial spelling differences or punctuation are normalized and treated as equivalent.

Table 1.

Performance of the proposed method on the SciERC dataset. Here, “Fuzzy” means fuzzy matching.

Algorithmic specification (fuzzy matching). We formulate fuzzy matching as a thresholded maximum bipartite matching problem. Let denote the set of normalized predicted triples and denote the set of normalized gold triples. For each pair , we compute a field-level similarity score

where _similarity_per_field is implemented as a per-field Jaccard-style similarity after normalization (e.g., lowercasing and removing trivial punctuation). We add an edge between and if , where the matching threshold is set to in our experiments. We then perform maximum-cardinality bipartite matching on this thresholded graph, enforcing a one-to-one correspondence between predicted and gold triples so that a single prediction cannot be credited for multiple gold triples (and vice versa). The number of matched pairs is counted as true positives (TP), and precision/recall/F1-score are computed as

Under this protocol, semantically aligned triples (e.g., paraphrased predicates or aliased entity mentions) can still be credited as correct even when they are not strictly identical in surface form.

By reporting the precision, recall, and F1-score under both strict and relaxed matching, we aim to simultaneously assess the model’s ability to produce fully accurate triples and its robustness in capturing semantically correct but lexically variant extractions.

Table 2 presents the performance of our method on the private dataset under both exact matching and fuzzy matching settings, providing a detailed comparison of its behavior across the two evaluation criteria.

Table 2.

Performance of the proposed method on the private dataset. Here, “Fuzzy” means fuzzy matching.

From Table 1 and Table 2, we observe that, compared with the baseline methods reported in prior work, our approach yields a notably larger performance gain when applied to the SciERC dataset. To ensure that this comparison is transparent and reasonably controlled, we clarify the source of each baseline result in the revised manuscript. Specifically, we re-ran CodeKGC using the official implementation under the same data split, preprocessing pipeline, and evaluation script as ours. For EDC, we report the results as stated in the original publication. We believe that these clarifications allow readers to interpret the comparisons in the proper context.

4.3. Ablation Study

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, we conducted an ablation study comparing three settings: (i) fine-tuning only, (ii) fine-tuning with the consistency-guided filtering module, and (iii) fine-tuning with both the filtering module and the iterative refinement module. Similarly to the previous case, we used both exact matching and fuzzy matching, and we removed the modules from the framework to determine whether they contribute to the optimization of the final experimental results. For each matching mode, we applied three ablation strategies: first, we performed LoRA denoising fine-tuning to obtain the baseline experimental results; second, we added the filtering (F) module to check if the experimental results improved; finally, we incorporated the iterative (R) module to obtain the final ablation experimental results. With these settings, we could empirically assess whether each component contributes to improving the final extraction performance.

We carry out a detailed ablation analysis, and the results are summarized in Table 3. In the ablation study, we adopt a strict matching protocol: a predicted triple is regarded as incorrect if any of its components differ semantically from the corresponding component in the gold triple. Non-semantic discrepancies, such as differences caused solely by letter case or trivial formatting variants, are normalized and counted as correct. Under this setting, we compare three configurations: (i) using only the large language model for extraction, (ii) applying the consistency-guided filtering module on top of the LLM outputs, and (iii) performing multi-round iterative extraction with both the filtering and iterative refinement modules, in order to validate the effectiveness of each component.

Table 3.

Ablation study results showing the performance of different configurations. Here, “F” means the filtering module, and “R” means the iterative module.

The experimental results show that, under strict matching, the configuration that uses only the LLM for extraction achieves the lowest performance among the three. Introducing the filtering module leads to a clear improvement in precision, indicating that a portion of mismatched triples is successfully removed. When the iterative refinement module is further incorporated to form the complete framework, the recall also increases, suggesting that some triples missed in a single pass are recovered in subsequent rounds. These observations collectively confirm the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Overall, the results in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 consistently suggest that our framework improves both the extraction quality and usability by addressing complementary failure modes of LLM-based KG construction.

First, the gains are more pronounced on SciERC than on our private welding corpus, which we attribute to the higher linguistic variability and broader schema coverage in SciERC, where denoising fine-tuning and iterative verification provide larger benefits.

Second, the gap between exact matching and fuzzy matching indicates that many remaining errors are dominated by surface-form variations (e.g., paraphrases and entity aliases) rather than fundamentally incorrect semantics, and the fuzzy protocol therefore better reflects robustness under realistic downstream usage.

Third, the ablation study shows clear functional separation between modules: consistency-guided filtering primarily improves the precision by removing unsupported or inconsistent triples, whereas iterative refinement mainly improves the recall by recovering triples missed in a single pass.

Taken together, these findings support our design choice of combining lightweight LoRA adaptation with a closed-loop refinement process. We note that our approach still depends on the quality of the underlying generator and the chosen matching threshold, and future work could further improve the robustness via stronger verification signals and more principled calibration across domains.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper, we propose an open information prompt-based extraction framework that performs parameter-efficient adaptation on base models via LoRA and combines iterative refinement with consistency-guided filtering. Equipped with strict JSON output constraints, robust parsing, and deduplication, the framework forms a closed loop of generation–parsing–verification–prompt enhancement–cumulative aggregation, which steadily improves factual coverage and output stability. Our contributions are threefold:

- 1.

- We introduce a prior-enhanced iterative refinement mechanism that feeds back previously extracted entities/relations as priors to recover missed but text-supported triples, improving the recall with minimal loss of fidelity.

- 2.

- We propose a consistency-guided filtering module that verifies candidate triples against the source text and removes hallucinated or unsupported extractions, thereby improving the precision and reducing noise.

- 3.

- We adopt LoRA-based denoising fine-tuning on key Transformer projection layers to enable efficient domain adaptation and alleviate redundancy, making the extractor locally deployable and scalable across scientific domains.

These contributions are empirically validated on both a public benchmark (SciERC) and an in-house welding corpus, where we observe consistent gains under strict and fuzzy matching, and our ablation study further confirms that the filtering module primarily improves the precision while the iterative refinement module contributes to recall.

In future work, we will extend LECITE along the same three dimensions of adaptation, verification, and iterative refinement by incorporating knowledge graph embeddings into fine-tuning to enhance the adaptation quality, integrating external knowledge bases to make triple filtering more accurate, and introducing multi-evidence consistency verification to improve the stability and controllability. Inspired by analyses of exposure bias and distributional shift from an imitation learning perspective, we will also explore the extension of the current inference-time iterative closed loop to the training stage by adopting DAgger/DaD-style dataset aggregation and correction mechanisms.

Specifically, we plan to explicitly include intermediate states that the model is likely to encounter under free-running generation (e.g., prompts conditioned on previously extracted triples as priors) during training and leverage human annotations or a stronger verifier to provide corrective signals. This may help to mitigate error compounding and self-reinforcement across multiple iterations, thereby improving the robustness in cross-domain scenarios.

Author Contributions

D.X.: Software Development, Methodology Implementation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft. Q.Q.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was sponsored by the Advanced Materials-National Science and Technology Major Project (Grant No. 2025ZD0620100), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFB4606200), and the Key Program of Science and Technology of Yunnan Province (No. 202302AB080020).

Data Availability Statement

The data and source code that support the findings are available at https://github.com/shuxdh/LECITE, accessed on 25 December 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest/competing interests.

References

- Ji, S.; Pan, S.; Cambria, E.; Marttinen, P.; Yu, P.S. A survey on knowledge graphs: Representation, acquisition, and applications. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 494–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortliffe, E. Computer-Based Medical Consultations: MYCIN; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Bahdanau, D. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.; Yan, F.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yang, T. An automatic machining process decision-making system based on knowledge graph. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 34, 1348–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Li, P. Knowledge graph embedding based question answering. In Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 11–15 February 2019; pp. 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkani-Tür, D.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Heck, L.; Tur, G.; Zweig, G. Probabilistic enrichment of knowledge graph entities for relation detection in conversational understanding. In Proceedings of the INTERSPEECH, Singapore, 14–18 September 2014; pp. 2113–2117. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Zhuang, F.; Qin, C.; Zhu, H.; Xie, X.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A survey on knowledge graph-based recommender systems. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2020, 34, 3549–3568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Yuan, N.J.; Lian, D.; Xie, X.; Ma, W.Y. Collaborative knowledge base embedding for recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Zhang, N.; Chen, H.; Chen, H. Generative knowledge graph construction: A review. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.12714. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Wu, J.; Li, Q.; Peng, H.; Wu, X. A comprehensive survey on automatic knowledge graph construction. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 56, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Cui, X.; Cheng, N.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Xie, P.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; et al. Chatie: Zero-shot information extraction via chatting with chatgpt. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.10205. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, Z.; Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, F.; Guo, W.; Chen, H.; Zhang, N. Codekgc: Code language model for generative knowledge graph construction. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2024, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Dai, J.; Ji, T.; Qiu, X.; Zhang, Z. A unified generative framework for aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), Virtual, 1–6 August 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 2416–2429. [Google Scholar]

- Paolini, G.; Athiwaratkun, B.; Krone, J.; Ma, J.; Achille, A.; Anubhai, R.; Santos, C.N.d.; Xiang, B.; Soatto, S. Structured prediction as translation between augmented natural languages. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.05779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Dai, D.; Xiao, X.; Lin, H.; Han, X.; Sun, L.; Wu, H. Unified structure generation for universal information extraction. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.12277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žukov-Gregorič, A.; Bachrach, Y.; Coope, S. Named entity recognition with parallel recurrent neural networks. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 2: Short Papers), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, P.H.; Marinho, Z.; Martins, A.F. Joint learning of named entity recognition and entity linking. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.08243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.; Levy, O.; Choi, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L. Ultra-fine entity typing. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.04905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoe, Y.; Durrett, G. Fine-grained entity typing for domain independent entity linking. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Volume 34, pp. 8576–8583. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, D.; Liu, K.; Lai, S.; Zhou, G.; Zhao, J. Relation classification via convolutional deep neural network. In Proceedings of the COLING 2014, the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers, Dublin, Ireland, 23–29 August 2014; ACL: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2014; pp. 2335–2344. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. BART: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 7871–7880. [Google Scholar]

- Wadhwa, S.; Amir, S.; Wallace, B.C. Revisiting relation extraction in the era of large language models. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), Toronto, ON, Canada, 9–14 July 2023; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2023; Volume 2023, p. 15566. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Soh, H. Extract, define, canonicalize: An llm-based framework for knowledge graph construction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, A.; Incremona, A.; Tessera, D.; Toti, D. Mitigating exposure bias in large language model distillation: An imitation learning approach. Neural Comput. Appl. 2025, 37, 12013–12029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.; Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.06825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Li, A.; Yang, B.; Zhang, B.; Hui, B.; Zheng, B.; Yu, B.; Gao, C.; Huang, C.; Lv, C.; et al. Qwen3 technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. ICLR 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, Y.; He, L.; Ostendorf, M.; Hajishirzi, H. Multi-task identification of entities, relations, and coreference for scientific knowledge graph construction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1808.09602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.