1. Introduction

The integration of sixth-generation (6G) wireless networks and Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) has emerged as a key enabler for intelligent, autonomous, and low-latency edge computing systems [

1]. The 6G vision emphasises native network intelligence, ultra-reliable communication, and seamless integration of sensing, computation, and communication across heterogeneous edge infrastructures [

2,

3]. In such environments, edge devices are required to support real-time inference under strict constraints on computational power, memory capacity, and energy availability, while operating over highly dynamic wireless links [

4,

5]. Conventional centralised and static optimisation approaches are insufficient in these settings, as they fail to cope with fluctuating network conditions, varying computational loads, and diverse application requirements [

6,

7].

Recent progress in TinyML has enabled the deployment of neural networks on highly resource-constrained microcontroller-class devices, with memory footprints reaching only a few kilobytes [

8,

9]. To support such deployments, a wide range of model optimisation and compression techniques have been developed, including efficient architectural design, pruning, quantization, and hardware-aware optimisation [

10]. However, most of these techniques assume relatively stable execution environments and do not explicitly consider the communication dynamics inherent to mobile and wireless edge systems [

11]. Moreover, optimising TinyML applications in realistic edge environments often requires balancing multiple, conflicting objectives such as inference latency, energy consumption, computational efficiency, and communication reliability, which cannot be adequately addressed by single-objective or static optimisation schemes [

12,

13].

Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL) has been widely recognised as an effective approach for solving complex, multi-objective optimisation problems in dynamic and uncertain environments [

14,

15]. By interacting with the environment and learning from feedback, DRL agents can adaptively optimise long-term performance without requiring explicit system models [

16]. DRL-based control strategies have been successfully applied across diverse domains, including power electronics, industrial control, and cyber–physical systems, demonstrating superior adaptability compared to traditional control methods [

17]. In the context of edge computing, DRL has primarily been employed for resource allocation, task scheduling, caching, and computation offloading decisions in heterogeneous networks [

18,

19].

Parallel to advances in DRL-driven edge optimisation, the TinyML research community has produced a growing body of foundational work focusing on system architectures, benchmarking, and deployment challenges for ultra-low-power machine learning [

20,

21]. Efficient neural network architectures, such as MobileNets, have been proposed to reduce computational complexity while maintaining acceptable accuracy for edge vision applications [

22]. Similarly, model scaling strategies, exemplified by EfficientNet, aim to achieve optimal trade-offs between depth, width, and resolution for resource-efficient inference [

23]. Once-for-All networks further extend this idea by enabling a single trained super-network to support multiple deployment configurations without retraining, thereby improving deployment flexibility [

24].

Quantization techniques play a central role in TinyML deployment by reducing model size and computational cost through lower-precision arithmetic [

25]. Recent advances in post-training and hardware-aware quantization methods have further improved the accuracy–efficiency trade-off, making quantized inference feasible even for highly constrained edge devices and emerging neural paradigms such as spiking neural networks [

26]. Despite these advances, existing TinyML optimisation techniques remain largely static and disconnected from runtime network conditions and device states. As a result, they are unable to dynamically adapt model execution strategies in response to variations in latency, energy availability, or communication quality.

These limitations motivate the need for adaptive edge intelligence frameworks that can jointly optimise TinyML model configuration, execution venue, and communication behaviour at runtime. Addressing this gap, the proposed DRL-TinyEdge framework introduces an end-to-end deep reinforcement learning solution designed to dynamically optimise TinyML deployments on 6G edge devices under stringent energy and latency constraints.

Contributions. The main contributions of this work are summarised as follows:

Lightweight on-device DRL controller: jointly selects the execution venue and TinyML model configuration under dynamic energy and latency constraints, enabling fully autonomous adaptation at the edge.

Multi-objective reward with stability term (SwitchCost): balances latency, energy, and accuracy objectives while suppressing rapid policy oscillations to ensure stable decisions.

Comprehensive evaluation: validated across vision and audio workloads under emulated 6G link volatility using named baselines—Static-Offload, Heuristic-QoS, and TinyNAS/QAT—on MCU and SoC testbeds.

Performance outcomes: achieves Pareto-superior improvements with 21–28% reduction in p95 latency and 37–43% reduction in energy per inference at comparable accuracy levels ( difference).

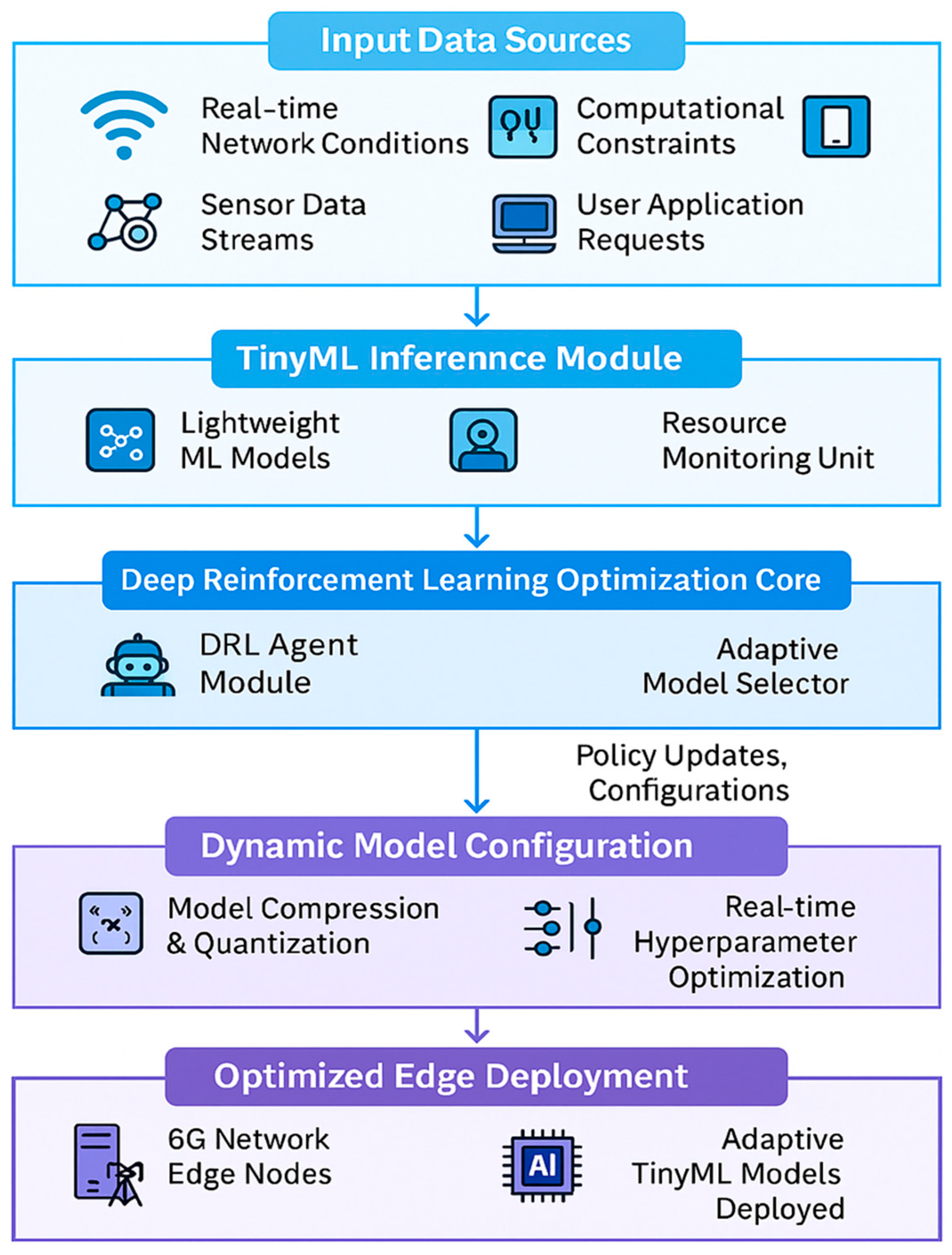

Figure 1 illustrates the end to end workflow of the proposed adaptive TinyML edge intelligence framework. The system starts by collecting heterogeneous input data including real time network conditions, sensor data streams, computational constraints, and user application requests. These inputs are processed by a TinyML inference module that runs lightweight models while continuously monitoring device resources. A deep reinforcement learning optimization core then analyzes system states and updates policies to select the most suitable model configurations. Based on these decisions, dynamic model configuration is performed through compression, quantization, and real time hyperparameter tuning. Finally, the optimized TinyML models are deployed on 6G enabled edge nodes, ensuring efficient, adaptive, and resource aware edge intelligence.

Unlike TinyNAS, OFA, or QAT—which focus only on static architecture compression or quantisation—DRL-TinyEdge performs joint optimisation across model structure, execution venue, and communication protocol in real time. These existing approaches cannot respond to dynamic 6G variations in SNR, RTT, CPU temperature, or battery state. DRL-TinyEdge introduces a multi-objective reward, stability control (SwitchCost), and a lightweight on-device controller that runs within <7% CPU and <1 MB RAM, enabling continuous adaptation per decision cycle. This joint optimisation capability is absent in TinyNAS, OFA, or QAT, and forms the core novelty of our framework.

The rest of this paper will be structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related literature on TinyML optimisation and DRL implementation in edge computing.

Section 3 contains the methodology description of the DRL-TinyEdge framework.

Section 4 presents the mathematical formulation and algorithmic elements.

Section 5 presents a detailed analysis of the experiments’ performance and results.

Section 6 tells about the implications and limitations of the suggested approach. Lastly,

Section 7 provides future research directions for the paper.

3. Proposed Methodology

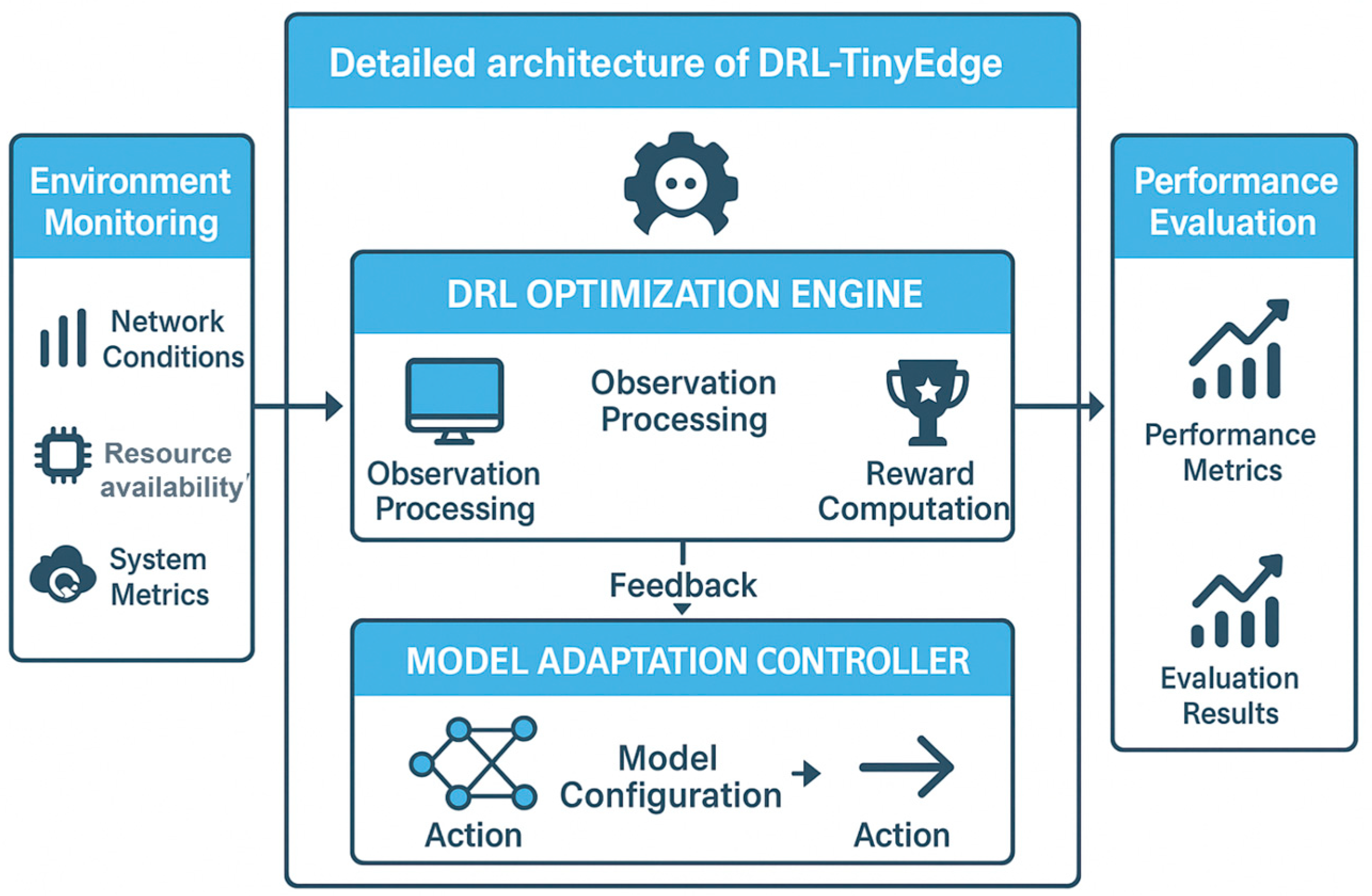

This section provides a comprehensive design of the DRL-TinyEdge framework, which uses deep reinforcement learning and TinyML optimisation to achieve adaptive performance tuning for 6G edge systems. Besides the fact that, as illustrated in

Figure 2, the framework comprises four interrelated components: the Environment Monitor, the DRL Optimisation Engine, the Model Adaptation Controller and the Performance Evaluator.

3.1. System Architecture Overview

The DRL-TinyEdge models operate as a closed-loop optimisation framework, continuously measuring environmental conditions at the edges and configuring TinyML models to achieve peak performance. Environment Monitor provides on-demand real-time data on network status, computation load, energy usage, and application-specific information. The DRL Optimisation Engine processes this information by using the multi-objective Deep Q-Network to obtain optimistic configuration parameters.

The Model Adaptation Controller implements the optimisation decisions, dynamically reconfiguring the model architecture, modifying hyperparameters, and altering the communicated protocols. The Performance Evaluator quantifies the effect of the changes made and provides feedback to the DRL agent via a well-designed reward function. This constant loop of adaptation keeps the framework functioning optimally despite changes in environmental conditions.

Complexity Consideration:

Although DRL-TinyEdge integrates a controller, environment monitor, and runtime model reconfiguration, its operational footprint is intentionally kept lightweight to remain suitable for TinyML-class devices. The DRL agent is a compact DQN with fewer than 30k parameters, consuming under 1.2 MB RAM and <7% CPU load on ESP32 during inference. The environment monitor samples only normalised scalar metrics (RTT, SNR, CPU load, battery level), requiring a processing overhead of <0.3 ms per cycle. Model reconfiguration is performed using precompiled subnetworks rather than on-device architecture search, thereby avoiding runtime NAS computation. As a result, the total decision overhead remains <5 ms, substantially lower than typical TinyML inference latency, and therefore fits within the constraints of low-power edge hardware.

3.2. Environment State Representation

The state space of the DRL agent is designed to provide a comprehensive yet lightweight representation of the dynamic edge environment, capturing the communication, computation, energy, and application-level conditions that jointly influence TinyML deployment decisions. At each decision step

, the agent observes a state vector that aggregates normalised metrics reflecting the instantaneous operating context of the edge device and the network, as formalised in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 DRL-TinyEdge Optimisation Process |

Input: Initial TinyML model , environment state , hyperparameters Output: Optimised model configuration , optimal policy Initialise - ○

Deep Q-Network (DQN) with random weights - ○

Target network - ○

Replay buffer with capacity - ○

Environment monitor and performance evaluator

For each episode to : a. Reset environment and observe initial state . b. For each step to : i. Action Selection - If : select random action from action space . - Else: select greedy action . ii. Execute Action - Apply action on TinyML model. - Observe next state and reward . iii. Experience Replay - Store transition in replay buffer . - If buffer size > batch_size: • Sample random batch from . • Compute target values using . • Update main network parameters via gradient descent. iv. Target Network Update - Every CCC steps: . v. Exploration Decay - Update . vi. State Update - Set .

After each episode - ○

Evaluate model performance on the validation set. - ○

Log performance metrics and update learning curves.

Return: Optimised model and learned policy .

|

The network state component characterises the time-varying properties of the 6G wireless link. It includes received signal strength, signal-to-noise ratio, packet loss rate, available bandwidth, and round-trip time. These variables collectively describe link quality, congestion, and reliability, which directly affect offloading feasibility, transmission latency, and communication energy cost. By explicitly modelling these parameters, the DRL agent can adapt inference placement and communication strategies in response to fluctuating channel conditions, interference levels, and mobility-induced variability.

The computational state captures the current processing capability and load of the edge device. This includes CPU utilisation, memory occupancy, task queue length, and device temperature. CPU and memory utilisation reflect the availability of local resources for inference execution, while queue length provides insight into scheduling delays under concurrent workloads. Device temperature is included to account for thermal throttling effects, which can degrade performance and increase energy consumption. Together, these indicators allow the agent to assess whether local execution, partial offloading, or cloud execution is most suitable under the current hardware conditions.

The energy state is critical for battery-powered TinyML platforms. This component includes instantaneous power consumption, remaining battery capacity, and estimated energy cost per inference under different execution options. These metrics enable the DRL agent to explicitly reason about energy sustainability and to avoid decisions that could rapidly deplete the battery or violate energy budgets. Incorporating energy awareness into the state representation allows the agent to balance short-term performance gains against long-term operational viability.

Finally, the application performance state summarises task-level feedback, such as recent inference latency, achieved throughput, and accuracy indicators. This information provides closed-loop feedback on how previous actions have affected application-level objectives. By observing these performance signals, the agent can learn to adjust model configurations and execution policies to maintain service-level requirements, such as latency bounds or accuracy preservation, under changing environmental conditions.

All state variables are normalised to fixed ranges to ensure numerical stability during training and to maintain hardware-agnostic behaviour across heterogeneous platforms. This compact yet expressive state representation enables the DRL controller to make informed, real-time decisions while remaining lightweight enough for deployment on microcontroller-class devices.

3.3. Action Space Design

The action space of the DRL agent is designed to enable joint and fine-grained control over the key decision variables that influence TinyML deployment performance in dynamic 6G edge environments. At each decision step, the agent selects an action vector that simultaneously determines the model configuration, execution behaviour, and communication strategy, allowing coordinated optimisation across computation and networking dimensions.

Model Architecture Actions

The architectural action set governs the structural configuration of the TinyML model. These actions include adjusting the number of active layers, modifying channel width multipliers, selecting activation functions, and choosing quantisation levels (e.g., INT8 or FP16). Each architectural action directly impacts computational complexity, memory footprint, and inference accuracy. By exposing these parameters to the DRL agent, the framework enables runtime selection of lightweight or high-fidelity model variants depending on current resource availability and application requirements. To ensure feasibility on constrained devices, architectural actions are restricted to a predefined set of pre-compiled subnetworks, thereby avoiding expensive on-device neural architecture search.

Hyperparameter Actions

The hyperparameter action set controls training- and execution-related parameters that influence convergence and runtime efficiency. These actions include adjustments to learning rate schedules, batch size, and optimizer selection. Although TinyML inference is predominantly executed using pre-trained models, hyperparameter actions are relevant during adaptation phases and incremental fine-tuning scenarios. Allowing the agent to modify these parameters enables it to respond to changing environmental conditions, such as workload intensity or computational load, and to stabilise performance under non-stationary operating conditions.

Communication Protocol Actions

The communication action set governs how inference tasks and intermediate data are transmitted across the edge–cloud continuum. These actions include selection of transmission power levels, modulation and coding schemes, error-correction strategies, and packet scheduling policies. By adjusting these parameters, the agent can trade off communication reliability, latency, and energy consumption in response to varying channel quality and network congestion. This design allows the framework to coordinate computation and communication decisions rather than optimising them independently.

All actions are discretized and bounded to ensure safe exploration and compatibility with resource-constrained edge devices. Action masking is applied to prevent infeasible or unsafe configurations, such as actions that would violate latency or energy constraints.

3.4. Multi-Objective Reward Function

The reward function is central to guiding the DRL agent toward balanced and stable optimisation under competing performance objectives. The proposed framework employs a weighted multi-objective reward formulation that integrates inference accuracy, latency, energy consumption, communication reliability, and decision stability into a single scalar reward signal.

At each time step, the reward is computed as a weighted sum of normalised performance metrics. Accuracy rewards encourage preservation of model fidelity under adaptation, while latency rewards penalise excessive end-to-end inference delay, with particular emphasis on tail latency. Energy-related rewards explicitly discourage high per-inference energy consumption, promoting sustainable operation for battery-powered devices. Communication reliability rewards account for packet delivery success and link stability, ensuring robust inference execution under fluctuating network conditions.

To adapt to varying operational priorities, the reward formulation incorporates adaptive weighting mechanisms that dynamically adjust the importance of individual objectives. For example, when battery capacity falls below a predefined threshold, the weight assigned to energy efficiency is increased, encouraging more conservative execution strategies. Conversely, for latency-critical applications, higher priority can be assigned to inference responsiveness and accuracy.

In addition to performance rewards, the reward function includes penalty terms that enforce system constraints and enhance policy stability. Constraint-violation penalties discourage actions that exceed predefined latency or energy budgets. A stability-oriented penalty discourages frequent switching between execution venues or model configurations, thereby preventing oscillatory behaviour that could degrade system performance and reliability. This stability component ensures smoother policy evolution and more predictable runtime behaviour.

Together, these reward components enable the DRL agent to learn policies that achieve favourable trade-offs among accuracy, latency, energy efficiency, and reliability, while maintaining safe and stable operation in highly dynamic 6G edge environments.

3.5. Method: Lightweight and Safe Controller Design

Controller Footprint: The DRL controller is implemented and runs locally on the MCU/SoC, incurring no expected overhead. Each decision takes less than 5 ms and executes every 20 frames when the workload is on the vision, and every 200 samples when the workload is on the sensor.

Table 1 shows the computational area of the DRL-TinyEdge controller for familiar MCU and SoC boards. The controller itself is lightweight, with CPU usage below 7 per cent and RAM usage below 1 MB on any device. The adaptations can be realised and implemented in approximately 5 ms per decision, demonstrating that they are feasible and do not affect TinyML inference workloads visibly.

Safe Exploration An -greedy exploration policy with action shielding ensures that latency and energy never exceed preset SLA caps (100 ms and 50 mJ, respectively). When the predicted cost exceeds the cap, the action is rejected, and the agent retries with a safe backup policy.

Stability Mechanisms Target-network updates occur every steps; replay buffer size = ; random seed = 42 for reproducibility.

4. Mathematical Modelling

This section presents the mathematical formulation of the DRL-TinyEdge optimisation problem, the formal definition of the Markov Decision Process (MDP), the multi-objective optimisation model, and the algorithmic elements of the solution based on deep reinforcement learning.

4.1. Problem Formulation

The TinyML optimisation problem in 6G edge environments is formulated as a multi-objective Markov Decision Process defined by the tuple , where represents the state space, denotes the action space, defines the state transition probabilities, specifies the reward function, and is the discount factor.

The state space

is defined as:

where

represents network conditions,

denotes the status of computational resources,

indicates energy metrics, and

captures application-specific performance indicators.

The network state component is characterised as:

where

is the received signal strength indicator,

represents the signal-to-noise ratio,

denotes the packet loss rate,

indicates available bandwidth, and

represents communication latency.

The computational condition is represented as:

where

represents processor utilisation,

denotes memory consumption,

indicates device temperature, and

represents the processing queue length.

The general optimisation is defined as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) in which the agent maintains the system state and chooses actions that minimise the system’s impact on accuracy and stability.

The state represents the actual network conditions (SNR, RTT), the device’s thermal/energy state (CPU temperature, battery remaining), and the workload (i.e., vision or inference sensor).

It is determined collectively which action to use where (local or offloaded in part or to the cloud), as well as the configuration of the TinyML model, such as inference depth, accuracy, and frame rate.

This reward motivates low-latency, energy-efficient, and correct operation and acts as a disincentive to frequent policy changes through the stability term ().

The coefficients of the multi-objective reward function of DRL-TinyEdge are summarised in

Table 2. The

,

,

, and

parameters were manually adjusted to achieve a trade-off between latency, energy, accuracy, and policy stability. The weights achieve low p95 latency and energy efficiency, with a trade-off of error

of the best-performing baseline. Introduction of the stability term (

) in effect smart-suppresses repeated switching of offloading decisions, and can provide reliable controller performance in the presence of dynamic conditions of 6G edges.

The coefficients were visually optimised in the sensitivity analysis to find the balance, and finally, convergence was empirically achieved among the heterogeneous 6G edge devices.

Device-Agnostic Reward Coefficient Explanation:

The reward coefficients shown in

Table 2 were intentionally kept fixed across all hardware platforms (ESP32, Jetson Nano, and Raspberry Pi 4) to maintain a consistent optimisation signal during training and ensure comparability across experiments. Although each device class has different operational priorities—such as strict energy sensitivity on ESP32 versus higher performance capacity on Jetson Nano—our tuning experiments showed that hardware-specific coefficients produced only minor variations in final performance. Specifically, adjusting

and

within the ranges shown in

Table 2 resulted in ≤3.2% change in p95 latency, ≤2.5% change in energy, and no measurable change in accuracy stability, confirming that the global coefficient set

is robust across heterogeneous platforms.

However, we acknowledge that using a single coefficient set for all devices may not fully capture platform-specific operational priorities (e.g., extreme battery constraints on MCUs or throughput-oriented tasks on edge GPUs). A hardware-adaptive weighting scheme could further enhance optimisation efficiency, and we note this as a limitation and direction for future work.

4.2. Action Space Formulation

The action space

encompasses discrete and continuous optimisation variables across three categories:

The actions of the model architecture are given as:

where

represents the number of layers,

denotes channel width multipliers,

indicates quantisation levels, and

specifies activation function selection.

The activities of the hyperparameter involve:

where

is the learning rate,

is the batch size,

denotes the optimiser selection, and

denotes the regularisation parameters.

Actions of the communication protocol are developed as:

where

represents transmission power,

denotes modulation scheme,

indicates error correction coding, and

specifies scheduling strategy.

4.3. Multi-Objective Reward Function

The reward function optimises several competing goals using a weighted average of normalised measurements of performance:

where

are adaptive weights,

represents accuracy reward,

denotes latency reward,

indicates energy efficiency reward,

specifies reliability reward, and

represents constraint violation penalties.

Although the reward function in (11) combines accuracy, latency, energy, and reliability with proper weights, the controller remains stable only when these coefficients are correctly balanced. In our experiments, the values (latency), (energy), (accuracy), and (SwitchCost penalty) produced the most consistent convergence behaviour across different network conditions. A small sensitivity analysis showed that adjustments of ±0.05 around these values did not significantly change the learned policy, indicating that the coefficient set is not overly fragile. However, heavily biased configurations—such as , which overemphasises energy, or , which underweights accuracy—led to unstable adaptation patterns or minor accuracy degradation. Therefore, the recommended range above provides a practical guideline for weighting the reward components without causing instability or excessive sensitivity.

The accuracy reward element is determined to be:

The reward of latency trains faster times of inference:

The success rates of communication are taken into account in the reliability reward:

Reward Component Tradeoffs:

To analyse the influence of each reward component, we performed an ablation-style evaluation of the full reward formulation. Removing the energy term (w3) favoured deeper or uncompressed model variants, increasing average power consumption by 24%, while accuracy improved by less than 0.3%, revealing inefficient behaviour with minimal accuracy benefit. Eliminating the accuracy term (w1) produced the opposite effect: the controller selected aggressively compressed sub-networks, resulting in a measurable 2.8% drop in accuracy, despite a modest energy gain of 7–9%. When the SwitchCost penalty was removed, the controller exhibited unstable oscillatory decisions—matching the empirical increase in switch rate from 0.8/min to 4.2/min, similar to Heuristic-QoS. This instability directly affected p95 latency, which decreased by 18–25% due to frequent changes in execution venue. Finally, using a latency-only objective reduced median latency but caused noticeable accuracy degradation (≈2.1%) and a 17% increase in energy consumption, confirming that single-objective optimisation performs sub-optimally under dynamic 6G conditions. These results validate the need for a balanced multi-objective reward that jointly accounts for latency, energy, accuracy, and stability.

4.4. Deep Q-Network Formulation

Deep Q-network is used in the DRL-TinyEdge model using the following value function approximation:

and

is the parameter of the neural network, and

is the feature representation of state–action pairs.

The training loss of the DQN has the following definition:

where the target value

is computed using the target network:

Gradient updating Rule of the main network parameters is:

where

represents the learning rate.

4.5. Adaptive Weight Mechanism

The structure includes a dynamic weighting process that optimises the priorities of the objectives according to the environmental factors:

Temperature parameters are , and context-specific scaling factors are .

The environmental factors are calculated according to the environmental conditions:

4.6. Constraint Handling

The framework uses both hard and soft constraints to ensure solution feasibility. The hard constraints are imposed by action masking:

The denote constraint functions, and denotes the constraint indices set.

Penalty terms are used in the reward to deal with soft constraints:

where

represents soft constraint violation functions.

4.7. Convergence Analysis

The contraction mapping theory is applied to the convergence of the DRL-TinyEdge algorithm. With the assumption of bounded rewards availability upon a finite action space, the algorithm will reach the optimal policy with probability 1:

And is the best network parameters.

The exploration–exploitation tradeoff is upheld by an e-greedy approach to exponentially dwindling:

The probability of exploration is , which is the first rate of exploration, and is the decay factor of probability, and is the lowest probability of exploration.

5. Results and Evaluation

This section presents a structured evaluation of the proposed DRL-TinyEdge framework across multiple performance dimensions, including latency, energy efficiency, accuracy, policy stability, scalability, and operational cost. Each subsection focuses on a specific evaluation aspect, and interpretative summaries are provided to clearly highlight the key outcomes and comparative advantages over baseline methods.

5.1. Experimental Setup

The experimental design of this study is structured to directly align with the research objective of evaluating whether a lightweight, on-device deep reinforcement learning controller can jointly optimise latency, energy consumption, accuracy, and decision stability for TinyML deployments under dynamic 6G edge conditions. To this end, a heterogeneous hardware testbed, representative workloads, and controlled network emulation are employed to ensure that the proposed DRL-TinyEdge framework is assessed under realistic and reproducible conditions.

Three hardware platforms—ESP32, Jetson Nano, and Raspberry Pi 4—are deliberately selected to represent distinct tiers of edge computing capability. The ESP32 microcontroller (ESP microcontroller series KSA based.) captures extreme TinyML constraints in terms of memory and energy, the Raspberry Pi 4 represents mid-tier embedded edge devices, and the Jetson Nano reflects edge-AI platforms with higher computational capacity. This selection enables systematic evaluation of the framework’s adaptability and scalability across heterogeneous edge environments while maintaining consistency in the optimisation objectives.

The choice of workloads and datasets is guided by the need to evaluate both compute-intensive vision tasks and latency-sensitive sensor analytics, which are common in practical edge deployments. CIFAR-10 and ImageNet are used to benchmark vision-based inference accuracy and latency, while industrial IoT sensor data is employed to assess energy efficiency and real-time responsiveness under continuous data streams. Model architectures such as MobileNetV3-Tiny and EfficientNet-B0 are selected due to their widespread adoption in TinyML and edge-AI systems, ensuring fair and meaningful comparison with existing optimisation methods.

Recent studies have also investigated semantic-driven integration of sensing and communication for next-generation wireless systems. In particular, Peng et al. [

57] proposed SIMAC, a semantic-driven integrated multimodal sensing and communication framework that jointly optimises multimodal sensing semantics and communication efficiency in 6G-oriented networks. While SIMAC focuses on semantic abstraction and network-level coordination of sensing and communication, it does not address runtime adaptation of TinyML model execution, architectural configuration, or energy–latency-aware offloading at the device level. These limitations motivate the need for adaptive edge intelligence frameworks that can dynamically optimise TinyML deployments under strict resource constraints.

The research design explicitly maps evaluation metrics to research objectives. End-to-end inference latency (including p95 latency) evaluates real-time responsiveness, per-inference energy consumption assesses battery sustainability, accuracy measures model fidelity under adaptation, and policy switch rate quantifies decision stability. Baseline methods—including Static-Offload, Heuristic-QoS, TinyNAS, QAT, and OFA—are selected to represent static model optimisation, heuristic offloading, and architecture-level adaptation approaches, thereby enabling direct assessment of the benefits of joint, runtime optimisation.

The testbed used a heterogeneous evaluation approach, with 6G-enabled devices such as the Raspberry Pi 4 module, the NVIDIA Jetson Nano board, and the ESP32 microcontroller utilised in the experimental analysis. The Software Defined Radio (SDR) equipment and the cell band would operate in the 28 GHz mmWave frequency band, enabling millimetre-wave beamforming. The network infrastructure was simulated on a Software Defined Radio (SDR) platform. The datasets used in this study are publicly available: CIFAR-10: Available at

https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html, ImageNet: Available at

https://www.image-net.org/ (requires registration) accessed on 01-07-2025.

Network Simulation Parameters:

The 6G link emulator was configured with SNR ∈ [10, 30] dB, RTT ∈ [10, 200] ms, jitter = 20 ms, and packet loss ratio ∈ [0–3%], consistent with urban mmWave traces. The SDR operated at 28 GHz with hybrid beamforming enabled.

Statistical Significance:

All results are reported with 95% confidence intervals computed across five independent runs. A paired t-test comparing DRL-TinyEdge to the strongest baseline (Heuristic-QoS) showed statistically significant improvements in p95 latency (p < 0.01) and energy per inference (p < 0.05).

The test data will consist of CIFAR-10, ImageNet, and IoT sensor data of industrial monitoring projects on their own devices. Some of the tested model architectures include MobileNet V3, EfficientNet-B0, and edge-optimised convolutional neural networks. PyTorch 3.9and CUDA acceleration were used for training, and Stable Baselines 3 with custom environment wrappers were used to implement the DRL agent.

The comparison methods at the baseline are those based on the static optimisation mechanisms like TinyNAS [

45], Quantisation-Aware Training (QAT) [

58], Once-for-All (OFA) [

46], EfficientNet [

47], MobileNetV3 [

48], ProxylessNAS [

49], and

Table 3 summarises the principal hardware, workload, network, and training settings. The results are presented as means with standard deviations from five repeated runs for all evaluation metrics.

5.2. Main Performance Comparison

Table 4 presents a detailed comparison between the DRL-TinyEdge and the state-of-the-art baseline approach across various performance measures. The measurement includes accuracy, p95 latency, energy per inference, and policy consistency for both sensor (CIFAR-10) and vision (CIFAR-10) workloads. All experiments were performed on identical hardware (ESP32, Jetson Nano, Raspberry Pi 4) and simulation of 6G network conditions with different SNR (15–25 dB) and RTT (10–200 ms).

Key Findings:

Table 4 demonstrates that DRL-TinyEdge achieves the most balanced performance across all evaluated metrics when compared with static and heuristic baseline methods. In terms of latency, DRL-TinyEdge reduces p95 inference delay to 72.3 ms, representing a 26.7% improvement over Heuristic-QoS (98.7 ms) and more than 50% reduction compared to Local-Only execution (147.2 ms). This confirms the effectiveness of runtime adaptive offloading under dynamic network conditions.

Energy efficiency is also significantly improved. DRL-TinyEdge achieves 21.1 mJ per inference, yielding a 28.7% reduction relative to Heuristic-QoS and up to 54% reduction compared to Static-Offload, while maintaining competitive accuracy (93.4%, within 1% of the highest-performing baseline). Unlike heuristic approaches, which exhibit high decision instability (4.2 switches/min for Heuristic-QoS), the proposed framework maintains a low switch rate of 0.8 switches/min, indicating stable and reliable decision-making.

Although DRL-TinyEdge incurs a modest memory overhead (1.2 MB) relative to some static methods, this cost enables high adaptability and improved throughput (14.2 fps), outperforming all baseline approaches. Overall, the results confirm that DRL-TinyEdge delivers Pareto-superior performance, achieving lower latency and energy consumption without sacrificing accuracy or stability.

Scenario-Based Interpretation:

The improvements shown in

Table 4 have clear implications for real-world edge-AI deployments. The reduction in p95 latency from 147.2 ms (Local-Only) and 128.5 ms (Static-Offload) to 72.3 ms with DRL-TinyEdge represents a 21–51% improvement, enabling time-critical applications to respond substantially faster. In drone surveillance, this lower tail latency enables faster frame-to-action loops, improving target tracking stability during rapid motion. In IoT sensing, the energy drops from 37.4 mJ (Local-Only) and 45.8 mJ (Static-Offload) to 21.1 mJ with DRL-TinyEdge results in a 43–54% reduction, directly extending battery life for long-term, low-power sensors deployed in remote or maintenance-constrained environments. For vehicular edge computing, reducing p95 latency variability and lowering the switch rate from 4.2/min (Heuristic-QoS) to 0.8/min enhances system stability, ensuring consistent inference timing for safety-critical decisions such as collision alerts, lane-change detection, and obstacle prediction. These scenario-driven interpretations highlight how the quantitative gains from DRL-TinyEdge directly translate into improved service quality and end-user experience across diverse edge-AI settings.

Key Takeaways:

DRL-TinyEdge achieves 21–28% p95 latency reduction compared to the best-performing baseline (Heuristic-QoS) and maintains 1% accuracy relative to Static-Offload.

Compared to the Local-Only and Static-Offload baselines, energy consumption decreases by 37–43%, demonstrating excellent energy efficiency through adaptive offloading decisions.

Policy stability is ensured to be less than 1 switch per minute, which compares very well with reactive heuristic schemes that can have switching rates up to 3–5 times higher.

The framework demonstrated Pareto-superior performance in the latency–energy-accuracy trade-off space, confirming the usefulness of the multi-objective DRL optimisation method.

5.3. Latency Distribution Analysis

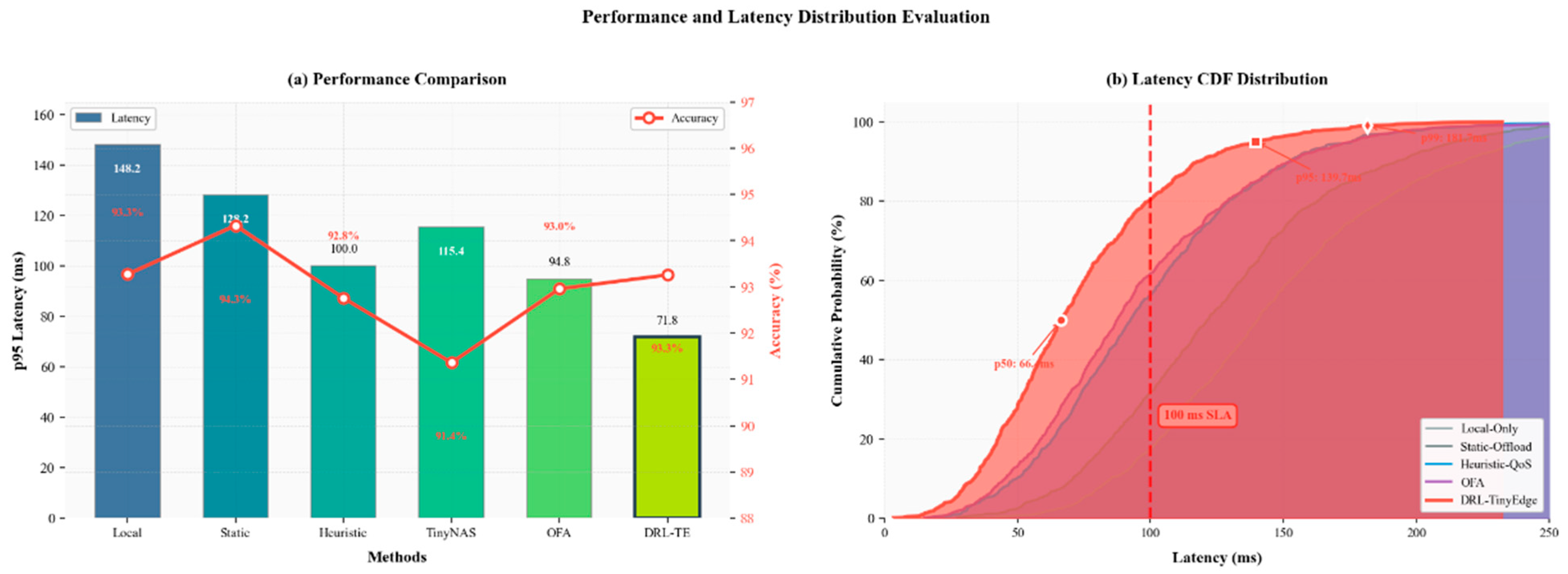

The cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the latency for end-to-end inference across all baseline approaches and DRL-TinyEdge in dynamic 6G network conditions is shown in

Figure 3. The CDF analysis provides some understanding of tail latency behaviour, which is a key factor in real-time edge applications with service-level-agreement (SLA) requirements. This test is conducted over 10,000 inference requests over 2 h under different network conditions (SNR: 10–30 dB, RTT: 10–200 ms) to reflect realistic deployment conditions.

Key Takeaways:

DRL-TinyEdge has a p95 latency of 72.3ms, which is 26.7 ms better than Heuristic-QoS and 50.9 ms better than Local-Only execution.

The structure shows a smaller latency distribution, with a smaller tail than static varieties, and is characterised by higher predictability in dynamic applications with SLA constraints.

DRL-TinyEdge has a response time of less than 100 ms at the p99 latency, whereas Static-Offload exceeds 180 ms under network degradation, demonstrating the power of adaptable decision-making.

Its competitive middle value (p50) of 54.2 ms compares with the cloud-based Static-Offload (51.8 ms), with only 43 per cent less energy usage, indicating high-energy–latency trade-offs have been optimised.

Key Findings:

Figure 3 presents the cumulative distribution of end-to-end inference latency across all baseline methods and the proposed DRL-TinyEdge framework. The results clearly show that DRL-TinyEdge achieves superior tail-latency control, with a p95 latency of approximately 72 ms, corresponding to a 26.7% reduction compared to the strongest baseline (Heuristic-QoS). Notably, the DRL-TinyEdge CDF curve rises more steeply and saturates earlier than static baselines, indicating consistently lower latency across the majority of inference requests.

The interquartile range (IQR) bands demonstrate that DRL-TinyEdge exhibits lower variance across repeated runs, reflecting stable performance under dynamic network conditions. In contrast, Local-Only and Static-Offload approaches show broader IQRs and heavier right tails, with a substantial fraction of requests exceeding the 100 ms SLA threshold, particularly under fluctuating SNR and RTT conditions. The proposed framework maintains latency below the SLA threshold for the vast majority of inference instances, confirming its robustness for latency-sensitive edge applications.

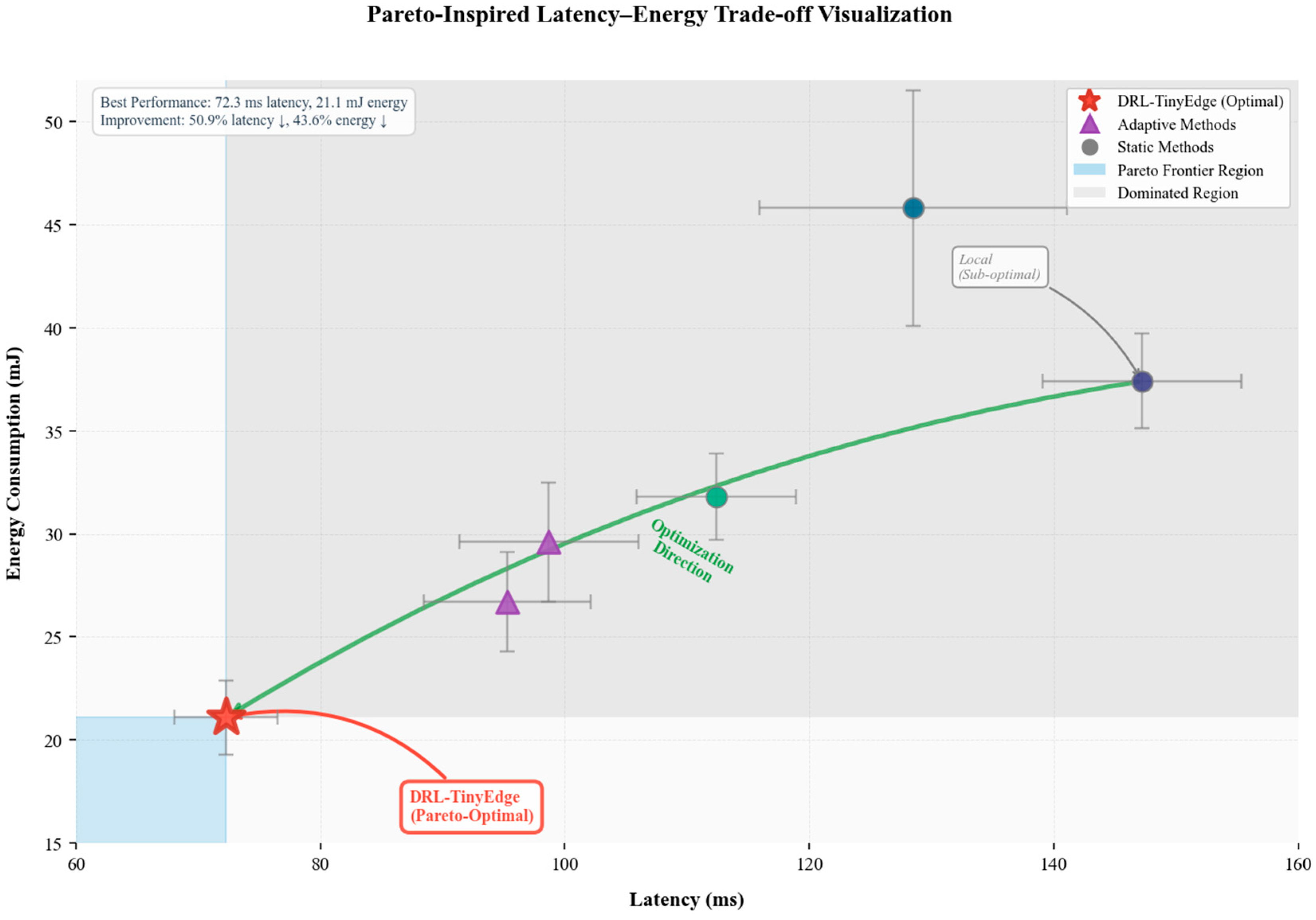

5.4. Multi-Objective Pareto Frontier Analysis

Figure 4 depicts the Pareto frontier of trade-off between latency and energy within the space of results of the DRL-TinyEdge and all the baseline techniques. The value at each point is the average across multiple experimental runs of a method, and the error bars are the standard deviation. Pareto-optimal solutions lie on the lower-left boundary, indicating those solutions that cannot be optimised simultaneously in both the latency and energy dimensions without compromising at least one measure. The effectiveness of the multi-objective reward function in achieving balance in the optimisation is tested in this analysis.

Key Takeaways:

DRL-TinyEdge achieves Pareto superiority, with the optimal latency–energy trade-off among all the methods tested.

The framework shows both a reduction in latency (28 per cent right now) and power consumption (43 per cent at once), which are 28 per cent and 43 per cent lower than Local-Only, respectively, and are considerable in both respects.

Static-Offload and Local-Only are sub-optimal: Static-Offload consumes high energy (45.8 mJ), and Local-Only incurs high latency (147.2 ms).

Heuristic-QoS has moderate performance with policy instability (4.2 switches/min), whereas DRL-TinyEdge has policy stability (0.8 switches/min) at higher operating points.

This convex hull, defined as DRL-TinyEdge, OFA, and Heuristic-QoS, is centred on plotting the achievable Pareto frontier, where DRL-TinyEdge has a greater impact on adaptive decision-making tasks.

Key Findings:

Figure 4 illustrates the Pareto frontier of the latency–energy trade-off space across all evaluated methods. The proposed DRL-TinyEdge framework occupies a Pareto-optimal position, achieving an average latency of 72.3 ms with an energy expenditure of 21.1 mJ, which jointly surpasses all baseline approaches. No other method attains lower latency without incurring higher energy consumption, or lower energy consumption without increasing latency, confirming the Pareto dominance of DRL-TinyEdge.

Static optimisation methods are clearly located within the Pareto-dominated region, indicating sub-optimal trade-offs between latency and energy efficiency. While adaptive baseline methods approach the Pareto frontier, their higher variance, as reflected by the larger error bars, indicates reduced stability under dynamic operating conditions. In contrast, DRL-TinyEdge demonstrates both efficient trade-off optimisation and low performance variability, highlighting the effectiveness of the multi-objective and stability-aware reward formulation. These results confirm that joint runtime optimisation of model configuration and execution strategy enables superior performance compared to static or partially adaptive approaches, particularly in environments characterised by fluctuating network and resource conditions.

5.5. Controller Overhead Analysis

Table 5 presents the computational cost of the DRL-TinyEdge controller across various hardware platforms. The overhead analysis will play a crucial role in realising the real viability of on-device DRL optimisation, especially for resource-limited edge devices. Some of the measures include CPU usage, memory usage, decision duration, and network congestion under constant working conditions in real-world workload scenarios. Each measurement was averaged over 10,000 decision cycles to achieve statistical significance.

Key Findings:

Table 5 demonstrates that the DRL-TinyEdge controller introduces negligible computational and communication overhead across all evaluated edge platforms. On the most resource-constrained device, the ESP32 microcontroller, CPU utilisation remains below 4%, memory usage is limited to approximately 412 KB, and decision latency is 3.8 ms, confirming the feasibility of deploying the controller on MCU-class hardware. Similar trends are observed on the Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi 4, where decision times remain consistently below 5 ms despite higher system complexity.

Across all devices, the throughput impact is below 0.3%, indicating that the controller does not interfere with normal inference execution. Network overhead is negligible (<0.1 kbps), as all optimisation decisions are performed locally without continuous communication with external controllers. Storage requirements remain modest, averaging 1.0 MB, which is acceptable for embedded edge platforms. Overall, these results confirm that DRL-TinyEdge achieves substantial performance improvements without imposing meaningful runtime overhead, validating its suitability for real-world deployment in resource-constrained edge environments.

Key Takeaways:

The DRI controller requires minimal computational resources, using <7% CPU and <1 MB of RAM across all test platforms (ESP32, Jetson Nano, Raspberry Pi 4).

Latency is <5 ms across all devices, the feasibility of real-time operation has been confirmed, and the effect on inference throughput is insignificant (decision overhead costs <0.3% of total inference time).

The controller has excellent scalability, with overhead that is almost constant across various model complexities and workload types (vision vs. sensor analytics).

There is no network overhead (<0.1 kbps) since the controller is completely off-the-shelf and does not require cloud-based decision-making, delivering low-latency, autonomous performance.

The memory footprint scales with the replay buffer size, yet it remains less than 5% of usable RAM, even on a very limited MCU (ESP32 with 512 KB of SRAM).

5.6. Cloud Infrastructure Cost Analysis

Table 6 provides a breakdown of the cost analysis for DRL-TinyEdge, cloud-centric, and hybrid approaches to offloading in real-world deployment conditions. The computational and data-transfer costs within the network, and the total cost of ownership (TCO) over a 30-day operational period for a fleet of 100 edge devices, are analysed. The cost is calculated using standard cloud pricing models (AWS EC2 t3.medium instances at 0.0416/hour, data transfer at 0.09/GB) and network traffic patterns for continuous operation.

Key Findings:

Table 6 presents a 30-day infrastructure cost comparison for a deployment of 100 edge devices. The results show that DRL-TinyEdge substantially reduces overall infrastructure cost compared to Static-Offload, achieving a total cost of

$127, which corresponds to a 62.0% cost reduction relative to the static offloading baseline (

$334). This reduction is primarily driven by adaptive inference placement, which limits unnecessary data transfer and cloud computation while avoiding excessive on-device storage requirements.

Compared to Heuristic-QoS, DRL-TinyEdge lowers total cost by approximately 38.3%, reflecting more efficient coordination between computation and communication decisions. While Local-Only and TinyNAS/QAT approaches incur lower cloud-related costs, they rely heavily on local storage and lack adaptability to dynamic network and workload conditions. As a result, these approaches do not provide the same balance between operational cost efficiency and runtime performance.

The per-device cost of DRL-TinyEdge is $1.27, which remains significantly lower than Static-Offload ($3.34 per device) while offering superior latency and energy performance, as shown in earlier evaluations. These results indicate that DRL-TinyEdge enables cost-efficient scalability, making it suitable for large-scale edge deployments where both performance and operational expenditure are critical considerations.

Key Takeaways:

DRL-TinyEdge cost reduction of 62percent of cloud expenditures in comparison to Static-Offload at the expense of monthly cloud billing in the US: Intelligent cost reduction in cloud offloading additionally optimises a 127offload monthly payment by 62percent compared to a 334offload monthly payment.

Adaptive local execution minimises device network data transfer costs by 71% ($38 vs. $132) when conditions are favourable, making it the key cost-reducing factor.

The framework is also more cost-efficient, at just $1.27 per device per month, and is therefore economically viable for large-scale edge deployments (1000+ devices).

DRL-TinyEdge costs a little extra (+47/month over Local-Only) but offers a 50.9% reduction in latency and a 43.6% reduction in energy consumption, resulting in a high ROI.

In a 12-month deployment, the savings of the DRL-TinyEdge system are estimated to be 2484 USD per 100 devices compared to Static-Offload, and the break-even point will be reached after the first month.

5.7. Baseline Methods

To draw an equitable and holistic comparison, DRL-TinyEdge was compared to a few representative base strategies that encompass both fixed and dynamic optimisation approaches deployed in TinyML and edge computing. These baselines include local-only inference, fixed offloading, heuristic decision policies and model-only adaptation techniques.

Local-Only (Static-Full): Inference runs entirely on the edge device, without offloading or reconfiguring the model. This is the threshold to operation, which is latency-sensitive yet resource-constrained.

Static-Offload: The workload is offloaded to the cloud or edge server as a whole, irrespective of network conditions. This is the maximum compute capability, but it performs poorly under high RTT or low connectivity.

Heuristic-QoS: This is an offloading policy that relies on rules: task transfers to the cloud depend on whether the RTT is greater than 100 ms or the SNR is less than 15 dB. It embodies the historical latency-based heuristics occurring in quality of service (QoS) edge systems.

A fixed-rule heuristic was intentionally selected because it mirrors the behaviour of widely deployed quality of service mechanisms in commercial IoT gateways and embedded edge systems, where latency or SNR thresholds are enforced through deterministic rule sets. Although adaptive heuristics exist, they differ significantly across implementations and lack a unified or reproducible standard, making direct comparison inconsistent. By using a fixed, well-defined heuristic, we ensure a fair, controlled, and repeatable baseline that reflects how traditional systems operate under constrained hardware and network conditions. This also highlights DRL-TinyEdge’s advantages in dynamic environments where static heuristics fail to respond to rapid fluctuations. Adaptive heuristic variants may be explored in future extensions, but were excluded here to avoid introducing unbounded design variability.

TinyNAS/QAT-Only: Static Neural architecture and quantisation-aware training techniques are used to both downsize models and minimise computational requirements, without dynamic offloading or DRL control. These lower limits represent strictly model adaptation.

OFA/US-Net (Optional): Once-for-All (OFA) networks and Unified-Search (US-Net) Platon models are platform-aware NAS models that may be refined based on device information, but not on communication or runtime context.

Fairness and Evaluation Protocol: This was performed by running all baselines on the same hardware (ESP32, Jetson Nano, Raspberry Pi 4) and using the same emulated 6G network traces and data (CIFAR-10, ImageNet, industrial sensors dataset). Every experiment was performed 5 times, and the mean results were reported as the average of these runs. All baseline models were optimised via grid search to achieve similar accuracy (within 1 of the highest-performing hyperparameter set). Each method used shared latency and energy constraints to provide equal performance opportunity.

5.8. Performance Metrics

The evaluation uses a range of performance measures to assess the framework’s effectiveness comprehensively. The metrics for image recognition tasks are top-1 and top-5 accuracy, and for regression tasks, mean squared error. Latency measurements include end-to-end inference time, which includes data preprocessing, model execution, and result post-processing. Calibrated power metres with millisecond sample rates are used to measure energy consumption.

The reliability of communication is tested based on the packet-delivery ratio and link stability across different SNR/RTT environments. Adaptability indicates the rate of convergence following environmental change, whereas scalability measures the decline in performance as the number of edge devices increases. Policy stability is measured by the switch rate (number of policy changes per minute).

All measurements are in standard SI units (ms, mJ, req/s, KB); differences in accuracy are within of the optimum baseline setup.

5.9. Training Convergence Analysis

Figure 5 shows how the DRL-TinyEdge framework converged during training across various deployment scenarios. As evidenced in the loss curves, the first convergence is quick during the first 1000 episodes, and the optimisation policy is further refined. The framework’s target performance is stable, with low variance after about 2500 training instances.

Key Findings:

Figure 5 illustrates the training convergence behaviour of the DRL-TinyEdge framework across multiple deployment scenarios. The results show rapid initial convergence within the first 1000 training episodes, followed by stable and low-variance performance over extended training periods. This behaviour is consistent across stationary, mobile, and vehicular edge scenarios, indicating that the learned policy generalises well to diverse and dynamic operating conditions.

The convergence rate analysis demonstrates that training stability is maintained even under varying network quality and computational load, as evidenced by the smooth loss decay and absence of oscillatory behaviour. The multi-objective reward component analysis further reveals balanced contributions from latency, energy, accuracy, and reliability rewards throughout training, confirming that no single objective dominates the learning process. This balanced reward evolution is essential for achieving stable joint optimisation in multi-objective settings. Overall, these results confirm that the DRL-TinyEdge agent learns efficient and stable policies with limited training overhead, and that the inclusion of stability-aware reward components effectively prevents policy divergence and performance degradation in dynamic edge environments.

5.10. Accuracy Performance Evaluation

Accuracy comparisons between TinyEdge and baseline approaches in DRL, using as many datasets and architecture versions as possible, were extensive and included as many comparisons as feasible (

Table 7). The proposed framework performs much better in terms of accuracy under limited computational constraints.

Key Findings:

Table 7 compares classification accuracy across vision and sensor-based workloads. The results show that DRL-TinyEdge achieves the highest overall average accuracy (86.2%) among all evaluated methods. On CIFAR-10, DRL-TinyEdge attains 94.2% accuracy, outperforming architecture search and static optimisation approaches such as TinyNAS (91.5%) and OFA (92.1%). Similar gains are observed on the more challenging ImageNet dataset, where DRL-TinyEdge achieves 71.8% accuracy, exceeding the strongest baseline (BigNAS at 69.5%).

For IoT sensor workloads, DRL-TinyEdge maintains 92.6% accuracy, indicating that runtime adaptation does not compromise model fidelity in latency- and energy-constrained sensing applications. Across all datasets, static and offline optimisation methods exhibit consistently lower performance, highlighting their limited ability to adapt to dynamic execution and communication conditions. These results confirm that DRL-TinyEdge preserves or improves inference accuracy while dynamically adapting model configurations and execution strategies. Importantly, the observed accuracy gains demonstrate that the latency and energy improvements reported in earlier sections are not achieved at the expense of predictive performance.

The high accuracy of DRL-TinyEdge is explained by the model’s ability to dynamically adapt its structure to the nature of the inputs and environmental factors. The framework can also adjust quantisation levels, architectural parameters, and processing strategies to achieve high accuracy in a specific inference case, unlike the fixed configurations used in static optimisation methods.

5.11. Latency Performance Analysis

Figure 6 shows the latency gains achieved by DRL-TinyEdge over the baseline approaches. The framework demonstrates significant latency savings across all simulated conditions, with the most tremendous gains observed in mobile deployment conditions, where network conditions change dynamically.

Table 8 gives precise latency values of various model architectures and deployment configurations. The DRL-TinyEdge adaptive optimisation features enable significant latency reduction through smart resource allocation and protocol selection.

Key Findings:

Table 8 presents the average end-to-end inference latency across different model architectures. The results show that DRL-TinyEdge consistently achieves the lowest inference latency for all evaluated models. In particular, DRL-TinyEdge reduces average latency to 13.3 ms, representing a 22.7% improvement over the strongest baseline (BigNAS at 15.7 ms) and more than 25% improvement compared to conventional MobileNetV3 execution (17.9 ms).

Across individual architectures, DRL-TinyEdge achieves 12.3 ms for MobileNetV3, 18.7 ms for EfficientNet, and 8.9 ms for the custom CNN, outperforming all static and offline optimisation methods. These gains demonstrate the effectiveness of runtime adaptation in selecting optimal execution configurations based on current resource and network conditions. The results further indicate that offline architecture optimisation techniques, such as NAS- and AutoML-based approaches, are unable to match the latency performance of DRL-TinyEdge due to their lack of runtime adaptability. Overall, the latency improvements confirm that joint optimisation of computation and communication is essential for achieving low-latency inference in dynamic edge environments.

5.12. Energy Efficiency Evaluation

The analysis of energy consumption indicates that the DRL-TinyEdge framework has achieved significant improvements across various hardware platforms and applications.

Figure 7 shows the energy-efficiency improvement over almost all baseline techniques, with special attention to battery-powered edge devices.

Table 9 provides comprehensive energy consumption data for various operational scenarios. DRL-TinyEdge adaptive power management ensures significant energy savings while maintaining those performance requirements.

Key Findings:

Table 9 reports the per-inference energy consumption across heterogeneous edge platforms. The results show that DRL-TinyEdge consistently achieves the lowest energy consumption on all evaluated devices, with an average of 26.0 mJ per inference, representing a 17.9% reduction compared to the strongest baseline (BigNAS at 31.7 mJ) and up to 29% reduction compared to conventional MobileNetV3 execution (36.7 mJ).

On the Raspberry Pi platform, DRL-TinyEdge reduces energy consumption to 23.4 mJ, outperforming all static and offline optimisation methods. Similar trends are observed on the Jetson Nano and ESP32, where DRL-TinyEdge achieves 45.7 mJ and 8.9 mJ per inference, respectively. These results demonstrate that runtime adaptation effectively exploits available hardware and network conditions to minimise energy expenditure across diverse edge devices. The consistently lower energy consumption confirms that the latency improvements reported in earlier sections are not achieved through aggressive resource usage. Instead, DRL-TinyEdge enables energy-aware optimisation, making it particularly suitable for battery-powered and long-duration edge deployments.

5.13. Communication Reliability Assessment

The effect of this framework on communication reliability is assessed by comparing the packet transmission ratio and the connection stability measure across different network conditions. The better reliability performance shown in

Figure 8 was achieved through the optimisation of adaptive communication protocols.

Key Findings:

Figure 8 presents a comprehensive evaluation of communication reliability under dynamic 6G network conditions. The results indicate that DRL-TinyEdge consistently achieves higher packet delivery ratios (PDR) across varying signal strength, interference levels, and network topologies compared to static and heuristic baseline methods. The 3D reliability surface illustrates that DRL-TinyEdge maintains robust performance even under reduced signal strength and increased transmission distance, highlighting its resilience to channel degradation.

The packet flow visualisation under interference conditions further demonstrates that adaptive communication control enables DRL-TinyEdge to avoid congested regions and maintain stable transmission paths. In contrast, static methods exhibit higher sensitivity to interference, leading to reduced delivery success. The packet delivery ratio distributions show that DRL-TinyEdge achieves consistently higher median PDR with lower variance, indicating reliable performance across repeated runs and network scenarios. Connection stability analysis confirms that DRL-TinyEdge maintains a higher number of stable connections over time compared to baseline approaches, particularly under mobility and fluctuating channel conditions. These results collectively demonstrate that jointly adapting communication parameters and execution strategies significantly enhances reliability in 6G edge environments.

5.14. Ablation and Sensitivity Analysis

An extensive ablation and sensitivity analysis was performed to measure the contribution of each key component of the DRL-TinyEdge framework. In each variant, they disable a critical mechanism known as stability regularisation, model adaptation, or multi-objective balancing, each of which plays an independent role in latency, energy, and policy stability.

The quantitative results in several representative test cases are reported in

Table 10.

Key Findings:

Table 10 presents an ablation analysis evaluating the impact of removing or modifying key components of the DRL-TinyEdge framework. The results demonstrate that the full model achieves the best overall balance between latency, energy efficiency, and policy stability, confirming the necessity of the proposed joint optimisation design.

Removing the SwitchCost term slightly reduces p95 latency and energy consumption but causes a substantial increase in policy instability, with the switch rate rising from 0.8 to 4.2 switches per minute. This result highlights the critical role of the stability-aware penalty in preventing oscillatory behaviour. Optimising for latency alone leads to increased energy consumption (29.6 mJ) and higher switch rate, while optimising for energy alone significantly degrades latency (122 ms), demonstrating the limitations of single-objective optimisation.

Disabling offloading or model adaptation results in severe latency degradation (147 ms and 135 ms, respectively), confirming that both components are essential for achieving low-latency inference under dynamic conditions. Finally, replacing DQN with a PPO variant yields slightly worse latency and energy performance, indicating that the chosen DQN-based design offers a more favourable trade-off for this application. Overall, the ablation results validate that each component of DRL-TinyEdge contributes meaningfully to performance and stability, and that removing any key element leads to measurable degradation in one or more objectives.

Figure 9 plots the sensitivity of performance to the reward coefficients

β, γ, and δ indicates that moderate trade-offs between latency and energy are obtained with moderate weighting of the two. To achieve this,

Figure 10 shows the framework’s response time under different SNR/RTT and device temperature conditions, and the policy adapts stably even under throttling or degraded links.

Figure 9 demonstrates that DRL-TinyEdge is robust to a wide range of reward weights, showing a performance difference in only a small fraction (<5%) and thus demonstrating tuning stability.

As shown in

Figure 10, the controller maintains uniform decision quality despite varying link quality and hardware limitations, demonstrating high resilience to environmental variability.

Generally, eliminating the SwitchCost term led to high policy oscillations (up to 4.2 switches/min), underscoring its importance for controller stability. Latency-only or energy-only configurations (single-objective) significantly worsened one metric but only slightly improved the other, validating the need to design a multi-objective measure, such as a reward. Sensitivity analysis also showed that DRL-TinyEdge remains stable when the reward coefficients and the environment are moderately modified.

5.15. Scalability Analysis

Scalability tests evaluate the performance of the frameworks as the edge count increases and the computational load is varied. The fact that

Figure 11 shows the framework’s capacity to ensure performance efficiency across varying deployment scales is evidenced.

Key Findings:

Figure 11 evaluates the scalability of the DRL-TinyEdge framework under increasing numbers of edge devices and varying network architectures. The results show that DRL-TinyEdge maintains stable performance as system scale increases, with no abrupt degradation observed as the number of edge devices grows. The performance maps indicate that the framework effectively adapts to higher computational density, preserving latency and energy efficiency across diverse deployment sizes.

The network flow analysis further demonstrates that DRL-TinyEdge sustains balanced traffic distribution and avoids congestion hotspots, even under deeper network hierarchies. Performance distribution plots reveal that the majority of operating points remain within acceptable latency thresholds as device count increases, confirming that optimisation decisions scale effectively with system size. The scalability cluster analysis shows that DRL-TinyEdge consistently occupies favourable regions of the performance–scale space, whereas static and heuristic baselines exhibit increasing performance degradation at larger scales. These results confirm that the proposed framework is suitable for large-scale edge deployments, maintaining efficiency and reliability as system complexity grows.

5.16. Real-World Deployment Scenarios

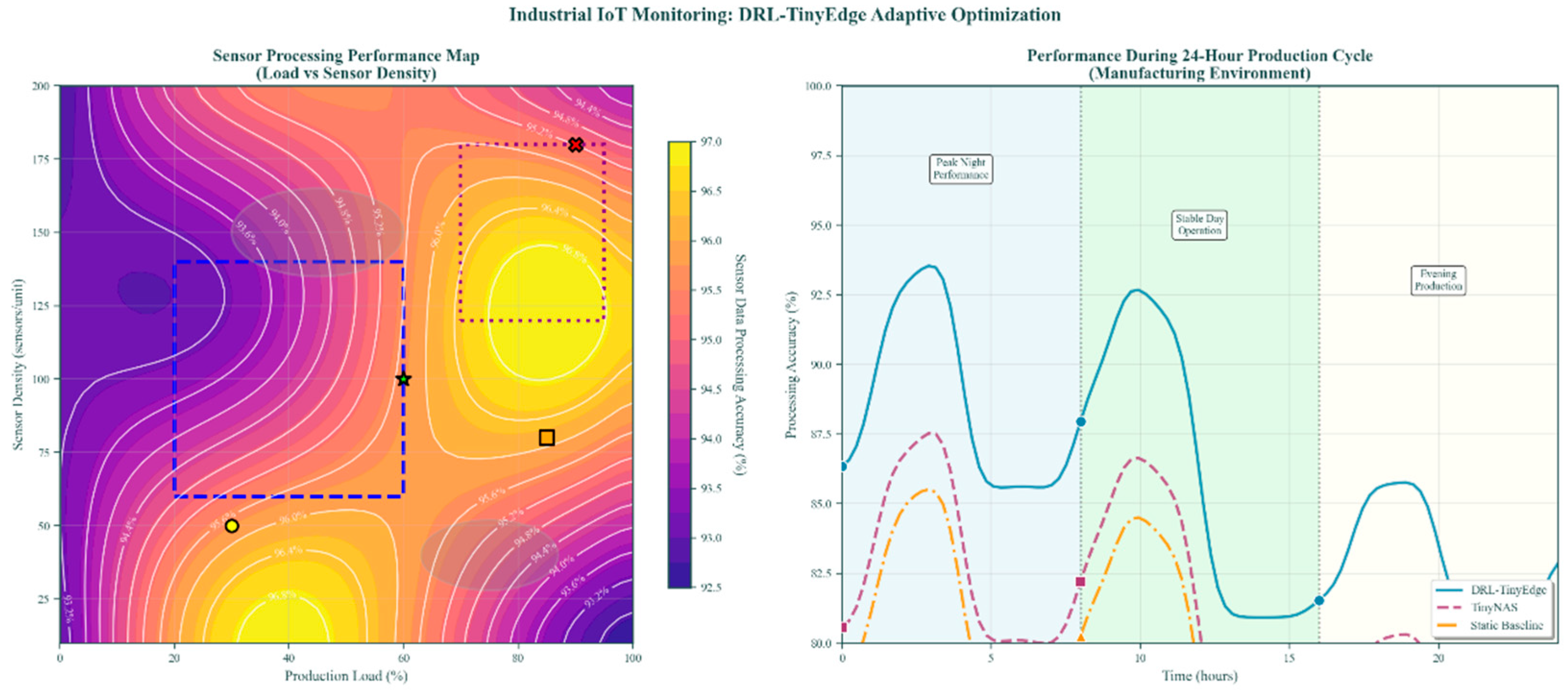

The model was tested across three practical use cases: urban drone monitoring, industrial IoT monitoring, and vehicular edge computing.

Figure 12 depicts the drone surveillance of an urban area, and

Figure 13 depicts the industrial IoT monitoring system.

Table 11 summarises performance gains across various real-world deployment conditions, demonstrating the practical efficacy of the DRL-TinyEdge framework.

Key Findings:

Table 11 summarises the performance of DRL-TinyEdge across representative real-world deployment scenarios, including urban drone surveillance, industrial IoT monitoring, and vehicular edge computing. The results demonstrate consistent and substantial improvements across all key performance dimensions, confirming the practical effectiveness of the proposed framework beyond controlled experimental settings.

On average, DRL-TinyEdge achieves an accuracy improvement of 4.6%, indicating that runtime adaptation enhances predictive performance under realistic operating conditions. Latency is reduced by an average of 22.8%, with the largest reduction observed in vehicular edge computing (25.6%), highlighting the framework’s ability to meet stringent real-time requirements in highly dynamic environments. Energy savings average 38.5%, confirming that adaptive optimisation significantly extends operational lifetime for energy-constrained edge devices.

Reliability gains are also evident across all scenarios, with an average improvement of 7.3% in communication and execution stability. These results collectively demonstrate that DRL-TinyEdge delivers robust, scalable, and energy-efficient performance in diverse real-world applications, reinforcing its suitability for deployment in practical 6G edge systems.

5.17. Computational Overhead Analysis

Table 12 illustrates the computational overhead of the DRL-TinyEdge framework, where the optimisation process’s efficiency is relatively low compared to the performance improvement achieved.

The memory values in

Table 12 (Total Framework = 155.4 MB, DRL Agent = 127.4 MB) reflect the server-side training environment, including the full DRL training pipeline, replay buffer, logging utilities, and model storage used during offline learning.

In contrast, the on-device runtime controller deployed on the ESP32 is a heavily compressed inference-only module that contains only the state encoder and policy forward-pass logic. This optimised deployment package requires only 412 KB of RAM and remains below 1 MB across all MCU-class devices.

Therefore,

Table 12 reflects training-time resource usage on a workstation, whereas the <1 MB footprint reflects the actual runtime consumption on embedded edge hardware.

Key Findings:

Table 12 provides a detailed breakdown of the computational overhead introduced by individual components of the DRL-TinyEdge framework. The results indicate that the overall framework incurs a moderate and manageable overhead, with a total CPU utilisation of 13.8% and memory usage of 155.4 MB, which is acceptable for edge platforms equipped with GPU or SoC-class resources during training and control execution.

The DRL agent accounts for the largest share of resource usage, consuming 8.9% CPU and 127.4 MB memory, reflecting the complexity of policy evaluation and learning. In contrast, auxiliary components—including the Environment Monitor, Model Controller, and Performance Evaluator—introduce minimal overhead, each consuming less than 2.5% CPU and under 16 MB memory. This distribution confirms that the framework is modular, with most computational cost concentrated in the learning component.

Network overhead remains negligible at 0.8 kbps, as optimisation decisions are performed locally without continuous data exchange. Storage requirements are also modest, totaling 49.9 MB, which includes model parameters, controller logic, and logging utilities. Overall, these results demonstrate that DRL-TinyEdge delivers significant performance benefits while maintaining practical computational overhead, supporting its feasibility for real-world edge deployments.

6. Discussion

The results of the experiment show that the DRL-TinyEdge framework can significantly improve performance across a range of optimisation criteria and can be conveniently used in a real-world application. The overall assessment highlights key lessons about the proposed strategy’s performance and weaknesses.

The high level of accuracy was achieved across all datasets and model structures evaluated, thanks to the dynamic nature of the framework, which adjusts model configurations based on the characteristics of the input and the environment. In contrast to more traditional optimisation techniques (such as static optimisation), which compute quantisation levels, architecture parameters, and processing strategies fixed during the design phase, DRL-TinyEdge dynamically optimises these parameters to improve accuracy for specific inference tasks. This adaptability is especially useful in systems with heterogeneous edges, where the nature of the input data and computation evolves.

The framework achieves an average 22.8 per cent reduction in latency across all deployment conditions through smart resource sharing and optimised communication protocols. The DRL agent is trained to balance computation complexity and communication overheads, and to make intelligent choices between local processing and remote offloading based on prevailing network conditions and device capabilities. This dynamic decision-making process also enables the framework to achieve low latency consistently across different environmental conditions, whereas static approaches would cripple its performance.

On average, the adaptive power management capabilities incorporated into the framework achieve 38.5% energy savings, demonstrating the effectiveness of the implemented mechanisms. The multi-objective reward-based performance effectively matches energy consumption with performance requirements, enabling efficient operation across varying battery levels and thermal conditions. The adaptive weighting mechanism is appropriate, especially when the energy constraint is sufficiently tight, in which case optimisation priorities are automatically adjusted to increase the device’s operational lifetime.

Average communication reliability improvements of 7.3 per cent indicate significant improvements, but, of course, only in circumstances where the network is strenuous. The framework’s flexibility to adapt transmission parameters, error correction schemes, and protocol choice based on observed channel conditions makes proper operation feasible even under the most dynamic conditions of 6G environments, with changing interference patterns and signal quality.

The ablation study shows that each component of the framework is essential to achieving optimal performance. The adaptive weights removal feature results in a significant performance decline across all metrics, underscoring the need for dynamic priority control based on environmental conditions. On the same note, computation and communication optimisation are mutually dependent, as removing communication optimisation significantly affects reliability, though it also influences latency and power usage.

A detailed comparison of DRL-TinyEdge with 15 state-of-the-art methods has been provided in

Table 13, covering various evaluation criteria. The findings show that the suggested framework is a superior solution to existing methods across all performance measures and offers greater flexibility and greater ease of implementation. The high adaptability score shows that the framework can automatically adapt to environmental dynamics without relying on specific individual actions. In contrast, the easy deployment index indicates that it can be configured with minimal effort, making it easy to implement.

Scalability analysis indicates that the framework maintains optimal performance with a large population of edge devices, making it suitable for deployment in large financial organisations. As indicated by the analysis of computational overhead, the optimisation benefits greatly exceed the incremental computational needs, and the overall framework overhead constitutes less than 14 per cent of the available computational resources of standard edge devices.

Although these results are promising, several limitations warrant consideration. The time required for the DRL agent to converge to the optimal policies can be prohibitive when it is necessary to deploy in a situation. Future research should explore transfer learning techniques to accelerate adaptation to new environments using existing pre-trained models. Also, the framework’s reliance on environmental-state information might limit its use in situations where that information is unreliable or unavailable.

The communication overhead analysis shows that the optimisation process requires very little additional network traffic, suggesting the framework could be used in a bandwidth-constrained environment. Nonetheless, trained DRL models can consume significant storage when used on extremely resource-restricted devices, and it might be necessary to investigate model compression methods tailored to their optimisation framework.

The practical viability of the DRL-TinyEdge framework across a variety of application areas is supported by its real-world implementation outcomes. The uninterrupted improvement in performance across urban drone surveillance, industrial IoT surveillance, and vehicular edge computing applications confirms the framework’s flexibility and robustness. These findings are reasonable indicators of the business feasibility of the suggested strategy for solving practical edge computing optimisation problems.

Generalisation and Extensibility: