Abstract

The evolution towards an Open Radio Access Network (O-RAN) and 6G introduces unprecedented openness and intelligence in mobile networks, alongside significant security challenges. Current cyber-ranges (CRs) are not prepared to address the disaggregated architecture, numerous open interfaces, AI/ML-driven RAN Intelligent Controllers (RICs), and O-Cloud dependencies of O-RAN, nor the now-established 6G paradigms of AI-native operations and pervasive Zero Trust Architectures (ZTAs). This paper identifies a critical validation gap and proposes a novel theoretical framework for a next-generation CR, specifically architected to address the unique complexities of O-RAN’s disaggregated components, open interfaces, and advanced 6G security paradigms. Our framework features a modular architecture enabling high-fidelity emulation of O-RAN components and interfaces, integrated AI/ML security testing, and native support for ZTA validation. We also conceptualize a novel Federated Cyber-Range (FCR) architecture for enhanced scalability and specialized testing. By systematically linking identified threats to CR requirements and illustrating unique, practical O-RAN-specific exercises, this research lays foundational work for developing CRs capable of proactively assessing and strengthening the security of O-RAN and future 6G systems, while also outlining key implementation challenges. We validate the framework’s feasibility through a proof-of-concept A1 malicious policy injection exercise.

1. Introduction

The telecommunications sector is undergoing a revolutionary change, moving beyond the current 5G architecture toward the intelligent, disaggregated, and open paradigms of O-RAN with the even more revolutionary capabilities of 6G on the horizon. However, these innovations, characterized by increased software-defined components, open interfaces, and AI/ML integration, also alter the security characteristics in a fundamental manner, introducing new attack surfaces and complex threat vectors.

Existing cyber-ranges now face a significant challenge. As we will explain in more detail later (in Section 2.4), current 5G-focused cyber-ranges often lack the necessary fidelity and specialized capabilities to address the security intricacies of O-RAN comprehensively. These include the disaggregated nature of its components (O-RU, O-DU, O-CU, Near-RT RIC, Non-RT RIC, SMO), the increase of new open interfaces (e.g., Open Fronthaul, E2, A1, O1, O2), the security of AI/ML models within xApps and rApps, and vulnerabilities specific to the O-Cloud platform. Looking towards 6G, these challenges are significantly amplified. 6G has been officially defined as an AI-native system from the ground up, with intelligence integrated across all network layers [1,2]. Zero Trust has evolved from an optional enabler in O-RAN to a foundational, mandatory pillar of the 6G security architecture [2,3,4]. Network functions will be broken down into even smaller pieces, and we’ll see entirely new ways of communicating, including native support for semantic communications, intelligent reflecting surfaces, and cell-free architectures [1]. Together, these major changes alter the way networks operate entirely. This renders current security validation techniques useless and requires the creation of entirely new methods.

This increasing gap between what is currently possible by existing cyber-ranges and what validation is required for O-RAN and next-generation 6G systems highlights a critical need. Sophisticated cyber-range environments must be capable of actively revealing vulnerabilities, rigorously testing new defense mechanisms, and appropriately training cybersecurity professionals to handle and defend such ever-more complex and mission-critical infrastructures. Without such next-generation validation platforms, the potential of O-RAN and 6G may be thwarted by untreated security vulnerabilities. This paper confronts this crucial need head-on by introducing a novel theoretical framework for a next-generation cyber-range for the security validation of O-RAN and emerging 6G networks.

The key contributions and novelty of this research work are described as follows:

- Comprehensive gap analysis for O-RAN and 6G security validation. We identify a significant gap in current 5G-focused cyber-ranges with the unique security challenges introduced by the Open Radio Access Network (O-RAN) architecture—specifically its disaggregation, numerous open interfaces, reliance on AI/ML-driven RICs, and O-Cloud dependencies—as detailed in O-RAN Alliance specifications. This analysis is extended to anticipate the even greater complexities and novel threat vectors of 6G systems [1,2]—this highlights the requirement for advanced cyber-range functionalities [5,6].

- Novel theoretical framework for next-generation cyber-ranges. We introduce a comprehensive and modular theoretical framework for cyber-ranges that is specifically designed to meet the complex security validation requirements of O-RAN and the upcoming 6G networks, as described in Section 5. This framework focuses on high-fidelity emulation of all key O-RAN components (O-RU, O-DU, O-CU, RICs, SMO) and their defined open interfaces (e.g., Fronthaul, E2, A1, O1, O2). Integrated AI/ML security testing functionalities aimed at identifying threats directed at O-RAN’s intelligent controllers (xApps/rApps) and the lifecycle of AI models [7]. Native support for simulating and validating dynamic Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA) principles across the disaggregated O-RAN and future 6G landscape [8,9,10]. A continuous risk evaluation feedback loop to enhance proactive security assessment.

- Systematic linkage of threats to requirements and practical exercise design. We map the O-RAN threat landscape (informed by O-RAN WG11 threat models) and projected 6G challenges to concrete cyber-range evolution requirements, as detailed in Section 4.2. The practical utility of our framework is further demonstrated through the design of detailed, cybersecurity exercise profiles tailored for O-RAN (presented in Section 5.5 and Appendix A), illustrating how advanced emulation can validate defenses against realistic attack scenarios.

- Conceptualization of an FCR architecture. Recognizing the scalability and specialization challenges of emulating the entire O-RAN/6G ecosystem monolithically, we propose and justify a FCR architecture (conceptually discussed in Section 5.7). This FCR model, built upon our modular framework, offers an approach for comprehensive security testing across distributed and diverse network domains, crucial for future multi-operator and multi-technology environments, particularly relevant for testing distributed ZTA implementations [9] or AI-driven Zero Touch Networks [4].

- A novel exercise definition schema. We propose a comprehensive, machine-readable schema (defined in Section 5.6 with full details in Appendix B) specifically designed to define and orchestrate the complex, multi-stage, and dynamic security scenarios required for O-RAN and 6G. This schema serves as a foundational data model for enabling automation, adaptive exercises, and objective-based assessments.

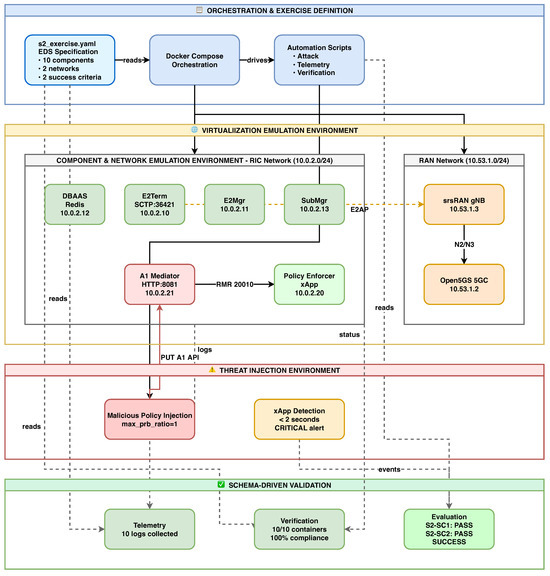

- Proof-of-concept validation of framework feasibility. We implemented Exercise S2 (Malicious A1 Policy Injection) by configuring and integrating existing open-source O-RAN software stacks to demonstrate the practical instantiation of a framework (Section 6). The implementation validates the Exercise Definition Schema design, operational O-RAN interface integration (A1 and E2 with verified message exchanges), and end-to-end exercise execution with automated assessment.

- Identification of key implementation challenges and future research pathways. We provide a realistic assessment of the significant technical and operational hurdles in developing such advanced cyber-ranges. Furthermore, we outline key future research directions, including standardized federation APIs, scalable hybrid emulation techniques, and advanced AI security modeling, to guide subsequent efforts in this critical domain.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the foundations of cyber-ranges and their evolution for 5G, culminating in a gap analysis for O-RAN and 6G. Section 3 details the O-RAN and 6G threat landscapes feeding Section 4 that presents a comprehensive analysis and links threats to CR requirements. Section 5 sets out our conceptualized theoretical framework, its structure, functional capabilities, STRIDE-based example exercises, the FCR model, and operational activities. Section 6 presents a proof-of-concept implementation that validates the feasibility of the proposed framework. Section 7 addresses implementation concerns and directions for future work.

2. Cyber-Ranges: Foundations and Evolution for 5G

2.1. Fundamental Cyber-Range Concepts and Architecture

A Cyber-Range (CR) consists of various technical components that are integrated to generate a realistic and controlled emulated environment for cybersecurity training, testing, and research. A cyber-range is a controlled and interactive environment designed to replicate networks, systems, tools, and operational processes for cybersecurity purposes [11,12,13]. Its primary goal is to enhance cybersecurity skills through hands-on training.

While implementations vary, a generic cyber-range architecture often comprises several key conceptual layers or functional blocks: Physical/Virtual Infrastructure Layer: Provides compute, storage, and networking resources (e.g., dedicated hardware or cloud resources). Emulation/Simulation Layer: Responsible for creating a simulation or emulation of the target environment. This involves virtualization technologies (hypervisors, containers), network emulation tools (Mininet, CORE), and simulators for specific systems or user behaviors. This layer typically supports the creation of isolated environments for conducting exercises. Scenario Management and Orchestration Layer: Automates the setup, execution, and teardown of cybersecurity exercises, defining objectives, roles (e.g., Red, Blue, White, Green teams), and injects. Monitoring and Data Collection Layer: Captures events, logs, and metrics from all emulated components for analysis and review. Attack/Event Injection Layer: Responsible for injecting malicious events or attacks into the emulated/simulated environment. User Interaction and Visualization Layer: Provides interfaces for trainees, instructors, and researchers [14,15,16]. The design of CR is often driven by key requirements such as flexibility in topology creation, scalability to accommodate complex scenarios, robust isolation between exercises, and cost-effectiveness [17,18].

2.2. The Impact of 5G on Cyber-Range Requirements

5G technology introduces major changes in mobile network architecture with concepts such as Software-Defined Networking (SDN), Network Function Virtualization (NFV), Service-Based Architecture (SBA) for the core network, dynamic network slicing capabilities, and Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) [19]. These innovations collectively transform traditional mobile network infrastructure into more dynamic, software-driven, and distributed ones [20,21]. Such fundamental changes brought new security challenges [22] and enhanced requirements upon existing cyber-range capabilities. In the virtualization layer, the CR now requires accurate and efficient emulation of Virtualized Network Functions (VNFs) and Containerized Network Functions (CNFs).

5G introduced several architectural changes that require CR evolution: Service-Based Architecture (SBA) with 5G Core NFs (AMF, SMF, UPF, NRF, AUSF, SEPP) communicating via APIs, requiring CRs to model NF interactions and API security implications. Network Slicing enables multiple logical slices on shared infrastructure, necessitating CR simulation of slice lifecycles and isolation. Multi-Access Edge Computing (MEC) introduces distributed edge attack surfaces requiring CR modeling capabilities. Software-centric architecture with extensive APIs expands vulnerability surfaces, necessitating sophisticated software security testing in CRs.These new demands required the evolution of CRs, including enhanced virtualization support (OpenStack, Kubernetes), improved network emulation for 5G protocols and data rates, new attack simulation capabilities (SBA attacks, signaling storms, slice breaches, MEC compromises), 5G security function testing (e.g., SEPP), and integration of 5G core emulators (Open5GS, free5GC, srsRAN) with traffic generation tools.

2.3. Overview of Key 5G Cyber-Range Projects and Efforts

In response to the unique demands of 5G, several initiatives and projects have emerged to build 5G-specific cyber-ranges or at least testbeds with significant security capabilities. These efforts often leverage common open-source components and aim to provide environments for research, validation, and training. NIST Technical Note 2311 provides a blueprint for deploying 5G O-RAN testbeds using diverse software stacks (srsRAN, Open5GS, RIC implementations) [23].

A notable example in this area is the SPIDER (H2020 Project) [24,25,26]. The SPIDER project aimed to create a cyber-range specifically for 5G security assessment, comprehensive training programs, and effective cyber risk evaluation. Its architecture orchestrates the deployment of virtualized 5G components through an Emulation Instantiation Manager and Vertical Application Orchestrator (VAO), building on the MATILDA project. For monitoring and analysis, SPIDER incorporated an advanced virtual Security Operations Center (vSOC) pipeline. SPIDER was designed to support a range of 5G-centric use cases, including testing the security of the 5G Service-Based Architecture (SBA) and training experts on VIM layer vulnerabilities [26]. It also explored the use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for generating synthetic attack traffic [25].

Beyond large-scale projects like SPIDER, other environments also contribute significantly to 5G security testing and training. The O-RAN ecosystem itself has fostered significant development in testbeds and experimental platforms. The OpenRAN Gym initiative provides an open-source toolbox for AI/ML development, data collection, and testing for O-RAN, often utilizing large-scale emulators like Colosseum (described as an Open RAN Digital Twin) and PAWR program testbeds [27,28,29]. Complementing this, the Open AI Cellular (OAIC) project offers an open-source 5G O-RAN testbed specifically for designing and testing AI-based RAN management algorithms [30]. Many of these platforms, including those detailed in the NIST blueprint, utilize foundational open-source 5G software stacks like Open5GS [31], free5GC [32], and srsRAN [33]. The O-RAN Software Community (OSC) also provides core components like the Near-RT RIC that are central to these testbeds.

Furthermore, industry-led collaborations, such as the 5G Security Test Bed (5GSTB), play a crucial role by validating 5G security recommendations in environments using commercial-grade equipment. The 5GSTB has published key findings on the security of HTTP/2 in 5G, the effectiveness of mTLS for Service-Based Interfaces, network slicing vulnerabilities, and security aspects of both NSA and SA 5G core architectures [34,35,36,37]. Additionally, telecommunications vendors (Keysight, Spirent, Cyberbit) offer commercial cyber-range platforms [38,39], while Mobile Network Operators maintain internal testbeds for validating network configurations and training SOC personnel. Lastly, standardization bodies and guidance organizations like ETSI (particularly its TC CYBER) [40] and ENISA (the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity) [6,41] publish important standards, guidelines, and threat landscape reports that significantly inform the development of 5G CR.

Table 1 compares capabilities between representative existing platforms and our proposed framework. SPIDER platfor excels in delivering comprehensive security training exercises [25], OpenRAN Gym and OAIC focus on AI/ML functional research and development [28,30], 5GSTB provides commercial validation for operator deployments [37], Keysight and Spirent platforms offer equipment testing and assurance capabilities [38,39]. Our framework is designed to complement these by specifically addressing O-RAN and 6G security validation gaps—particularly comprehensive disaggregated component and interface emulation, adversarial AI/ML security testing, native Zero Trust Architecture validation, and explicit alignment with the O-RAN WG11 threat model [42].

Table 1.

Comparison of cyber-range capabilities for O-RAN security validation.

2.4. Gap Analysis: The Shortcomings for O-RAN and Future 6G

While the aforementioned 5G cyber-ranges and associated testbeds such as those guided by NIST [23], developed with tools like OpenRAN Gym [28], or focused on 5G core security validation like the 5GSTB [37] represent a significant advancement in cybersecurity validation capabilities, a critical examination reveals limitations when confronted with the complexities introduced by the Open Radio Access Network (O-RAN) architecture and the even more significant changes that future 6G systems will bring. These emerging difficulties, and thus the gaps in present cyber-range capabilities, are highlighted in the detailed specifications released by the O-RAN Alliance Working Groups, particularly WG1 (Architecture) [43], WG2/WG3 (RIC specifications) [44], WG4 (Fronthaul) [45], WG6 (O-Cloud) [46], and WG11 (Security) [47]. Despite their advanced capabilities in several areas, this article argues that current 5G-focused cyber-ranges are typically unable to effectively handle the O-RAN and 6G paradigms for a number of important reasons, which are presented next.

Insufficient fidelity in O-RAN component and interface emulation. O-RAN’s disaggregated architecture introduces numerous components and interfaces [48,49,50]. While testbeds like NIST TN 2311 [23] support component deployment, existing CRs lack granular emulation fidelity for O-RAN-specific protocols and security testing [51].

Limited scope for comprehensive AI/ML security testing. While platforms like OpenRAN Gym [28] and OAIC [30] support AI/ML functional testing, and specific research explores adversarial attacks [52,53], dedicated CR capabilities for systematically assessing adversarial AI attacks and validating AI model lifecycle security within O-RAN [54] remain limited.

Inadequate modeling of O-Cloud-specific security challenges. Generic cloud security testing methodologies may not sufficiently cover O-Cloud-specific threat vectors, which are studied by O-RAN WG11 [55].

Deficiencies in representing dynamic trust models and multi-vendor interoperability risks. The open, multi-vendor nature of O-RAN introduces significant security complexities related to dynamic trust management, secure software lifecycle management for third-party xApps/rApps [56,57], and vulnerabilities arising from multi-vendor interoperability. Sophisticated modeling of these aspects is largely unaddressed by current CRs.

Lack of preparedness for emerging 6G security paradigms. Now-baseline 6G security paradigms that have been formally adopted such as AI-native security, extreme decentralization (building on O-RAN’s disaggregation, leading to cell-free architectures [58]), comprehensive Zero Trust Architectures (ZTAs) [9,10,51], and novel communication paradigms [1,5] requires entirely new foundational capabilities.

While O-RAN WG11 has ZTA studies [3,8] and the 5GSTB validates ZTA enablers like mTLS for the 5G core [34], CRs need to explore these across the whole O-RAN/6G ecosystem. Testing the security of THz links, quantum-resistant cryptography, or AI-driven autonomous security responses in federated 6G domains (as envisioned by initiatives like Next G Alliance [59] and AutoRAN [60]) are emerging requirements largely beyond current O-RAN testbed capabilities.

Lack of comprehensive and standardized exercise definition and orchestration models. Current CR exercise orchestration lacks a holistic model to define, manage, and orchestrate complex, dynamic, and federated cybersecurity exercises that are required for B5G/6G. This includes defining diverse emulated components, intricate scenario logic with adaptive responses, multi-role participant interactions, sophisticated scoring and gamification, and optimized resource allocation across federated nodes.

This identified fundamental gap between current capabilities and future requirements underscores the urgent need for a new generation of cyber-range architectures, designed to be more holistic and forward-looking, incorporating advanced information models for exercise definition and sophisticated orchestration frameworks capable of managing this new scale of complexity. The design must be informed by a deep understanding of the specific O-RAN and 6G threat landscape, as detailed in the following section.

3. O-RAN and 6G Threat Landscape

3.1. O-RAN System Architecture and Threat Vectors

The O-RAN architecture, defined across multiple WG specifications—WG1 (Architecture) [43], WG2 (Non-RT RIC) [61], WG3 (Near-RT RIC) [44], WG4 (Fronthaul) [62], and WG6 (O-Cloud) [43]— introduces novel components and open interfaces. This architecture creates new threat vectors currently analyzed by the O-RAN Alliance and industry stakeholders [8].

Service Management and Orchestration (SMO) Framework: Responsible for orchestration and management of O-RAN functions including O-Cloud and Non-RT RIC. Interactions via O1, O2, and A1 interfaces (per WG1 [63]) present vulnerabilities; security concerns are investigated by WG11 [64].

Non-Real-Time RAN Intelligent Controller (Non-RT RIC): Hosts rApps and performs control loops (>1 s latency), and is exposed to potential attacks via A1 (to Near-RT RIC) and R1 (within SMO) interfaces (per WG2 [61]). Managing AI models has significant security implications for AI/ML workflows [54,65,66].

Near-Real-Time RAN Intelligent Controller (Near-RT RIC): Hosts xApps and executes control loops (10ms-1s), presenting a complex attack surface through E2 (from E2 Nodes with E2 Service Models), A1 (to Non-RT RIC), O1 (management), and Y1 (data exposure) interfaces (per WG3 [44]). Platform and xApp security is a key focus area for WG11 [67].

xApps and rApps: Third-party applications running on Near-RT RIC and Non-RT RIC, respectively, introduce risks from malicious code injection, software vulnerabilities, data leakage, and conflicting behaviors. Securing their entire lifecycle, from development through onboarding to operation, is considered of critical importance [54].

O-CU, O-DU, and O-RU: Disaggregated RAN functions (Centralized, Distributed, and Radio Units) vulnerable through open interfaces (F1, W1, Open Fronthaul, O1) and underlying O-Cloud platform. Open Fronthaul interface, in particular, has been identified as a significant area of concern requiring robust security measures [7,62,68].

O-Cloud: Cloud platform hosting O-RAN functions (per WG6 [46]), exposed to virtualization escapes, container compromises, orchestration attacks (via O2 interface), insecure APIs, and misconfigurations [55].

Open Interfaces: Numerous interfaces (A1, E1, F1, O1, O2, E2, Open Fronthaul, Y1, R1) are prone to eavesdropping, tampering, spoofing, DoS, and authentication bypass if not secured according to O-RAN security protocol specifications [8,42,47].

Consequently, several key threat themes emerge from this architecture, extensively analyzed within O-RAN’s dedicated security documentation Threat Modeling and Risk Assessment reports [42]: an amplified attack surface due to openness and disaggregation; vulnerabilities in the cloud platform; risks from third-party applications (xApps/rApps); potential compromise of RIC components; and the challenge of securing numerous open interfaces.

3.2. 6G-Specific Security Paradigms

6G architectures, as defined in European deliverables [1,2], amplify O-RAN security challenges while introducing new paradigms [5,69,70]. Major initiatives actively shape this vision, outlining use cases, societal values, and key technological directions, including critical security aspects [1,2,59,71], with AI-native architectures bringing new considerations for securing AI systems. Key shifts are presented next.

AI-native network architectures. 6G’s pervasive AI/ML integration across all network layers is explicitly designated as its core architectural principle [1,2], elevating AI security to paramount importance [4,7]. Key concerns include model robustness, algorithmic explainability, data privacy assurance, and resilience against sophisticated adversarial attacks. Threats targeting AI models and training data are projected to become exceptionally critical [2,57], necessitating exercise scenarios modeling complex AI interactions and sophisticated attacks.

Extreme disaggregation and pervasive edge intelligence. 6G extends disaggregation beyond O-RAN toward cell-free architectures [1] with distributed edge intelligence hosting hyper-personalized services and semantic communication. This further magnifies network complexity, necessitating fine-grained, dynamic, context-aware security controls. The security of such highly distributed edge intelligence is a key research area, as highlighted in tactical 6G network studies [7], demanding validation scenarios modeling vast micro-service interactions and distributed control/data plane security.

Ubiquitous zero-trust architecture. While O-RAN explores ZTA principles [3,8], 6G demands ubiquitous Zero Trust as the default security posture across all domains [2,3,4,10]. The challenge lies in implementing, managing, and adapting ZTA policies (PDPs, PEPs) in heterogeneous, multi-vendor, multi-operator 6G environments, including O-Cloud. This necessitates validation scenarios that simulate dynamic policy interactions, federated trust assessments, and ZTA control plane resilience against attacks or misconfigurations. Physical-layer authentication offers a lightweight, zero-trust approach for device identification at the network edge [72]. Radio Frequency Fingerprinting (RFF) leverages inherent hardware imperfections in wireless transmitters to create unclonable unique device identifiers, providing an additional security layer independent of protocol-level credentials [73,74].

Secure multi-domain orchestration and federation. The orchestration of services in 6G will frequently span multiple administrative domains, some of which may be operated by different entities and potentially untrusted. Ensuring secure, resilient, and policy-compliant orchestration across these federated domains will require novel security frameworks and trust management mechanisms. Establishing federated trust is a significant challenge [59], requiring sophisticated multi-domain CR exercise scenarios. Blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLTs) offer a promising approach to addressing these federated trust challenges [75,76,77]. By enabling decentralized security and trust orchestration through smart contracts among multi-tenant and multi-operator scenarios, blockchain can support automated cross-domain security policy enforcement, audit trails for orchestration actions, and trust establishment without centralized authorities.

Novel spectrum usage and communication technologies. New spectrum bands (Terahertz) and communication technologies (Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces, Integrated Sensing and Communication) introduce physical and link-layer vulnerabilities that require characterization, modeling, and mitigation strategies [5]. For example, THz links, while offering high bandwidth, have unique propagation characteristics that can be exploited, and RIS elements themselves can become attack targets or require new security considerations.

The spectrum of 6G threat vectors is considerably broadened, including AI model poisoning and evasion [4,7], federated learning manipulation [78], exploitation of unforeseen policy gaps or misconfigurations within complex ZTA frameworks, attacks targeting DLT potentially used for trust management, and the inevitable discovery and exploitation of vulnerabilities within the novel communication technologies underpinning 6G [5]. The ENISA 5G threat landscape report also provides a foundational understanding of many threats that will likely be exacerbated or evolve in 6G [6]. Addressing such a diverse and advanced threat landscape necessitates cyber-range platforms capable of not only emulating these new technologies and threat behaviors but also supporting the definition and orchestration of highly complex, multi-layered validation scenarios. These O-RAN and 6G threat vectors necessitate systematic analysis to derive validation requirements. Section 4 undertakes this threat analysis to define critical CR capabilities.

4. Comprehensive Threat Analysis

4.1. Methodology

A rigorous threat analysis approach is essential for understanding the security posture of O-RAN and 6G. The O-RAN Alliance Working Group 11 has conducted extensive threat modeling utilizing frameworks such as STRIDE (Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, Elevation of Privilege) and risk assessment paradigms from ISO 27005 [79] and NIST SP 800-30 [80], documented in the O-RAN Security Threat Modeling and Risk Assessment (R004-v05.00) [42].

Building upon this foundation and extrapolating from emerging B5G/6G architectural visions (AI-native systems, pervasive ZTA, new communication paradigms), our methodology (1) synthesizes granular threats from O-RAN WG11 and projected 6G security challenges into thematic categories; (2) identifies the core security challenge per category; and (3) derives specific CR evolution requirements, including a comprehensive exercise definition schema. This grouping, detailed in Table 2, facilitates clear linkage between the evolving threat landscape and necessary CR capability advancements for O-RAN/6G.

Table 2.

Threat categories and cyber-range evolution requirements.

4.2. Threat Categories and Cyber-Range Requirements

Drawing from the O-RAN WG11 threat model [42] and 6G security challenges [1,2], Table 2 presents a structured set of CR evolution requirements linked to eight threat categories. The threat groups synthesize WG11’s threat inventory based on architectural locus, O-RAN functionality impacted, or vulnerability nature.

Group 1 (Systemic O-RAN Threats) addresses fundamental vulnerabilities across O-RAN components from insecure designs or misconfigurations (e.g., WG11 T-O-RAN-01, T-O-RAN-02). Group 2 (O-Cloud and Virtualization) consolidates cloud-native platform risks, including VM/container escapes (T-VM-C-02), image tampering (T-IMG-01), and O-Cloud interface vulnerabilities (T-O2-01, T-OCAPI-01), per WG6 [46] and WG11 [55] specifications. Group 3 (AI/ML and RIC Threats) encompasses threats against RICs (T-NEAR-RT-01 to T-NEAR-RT-05, T-NONRTRIC-01 to T-NONRTRIC-04), xApps/rApps (T-xApp-01 to T-xApp-04, T-rApp-01 to T-rApp-07), and AI/ML-specific attacks like data poisoning (T-AIML-DP-01), model evasion (T-AIML-ME-01), and model inversion (T-AIML-MOI-01) [54]. Group 4 (Interface and Protocol Threats) covers vulnerabilities across open interfaces including Fronthaul (T-FRHAUL-01, T-MPLANE-01), A1 (T-A1-01), E2 (T-E2-01), R1, and Y1, necessitating high-fidelity emulation per WG2 [61], WG3 [44], WG4 [45], and WG11 [47] specifications. Group 5 (Multi-Tenancy) addresses shared O-RAN deployments, particularly Shared O-RU threats like unauthorized lateral movement (T-SharedORU-01 to T-SharedORU-42 series). Group 6 (Supply Chain) covers lifecycle risks from compromised updates (T-AppLCM-01), tampered images (T-AppLCM-02), and vulnerable dependencies (T-OPENSRC-01). Group 7 (External, Physical and Radio Threats) includes physical breaches (T-PHYS-01) and radio attacks like jamming (T-RADIO-01).

Group 8 (6G-Specific Concepts), detailed in Section 3.2, addresses forward-looking paradigms. Unlike Groups 1–7, which primarily map to O-RAN WG11’s existing threat inventory, Group 8 requirements are anticipatory, encompassing AI-native security validation, large-scale ZTA testing across federated domains, novel 6G technology assessment (THz, RIS, ISAC), quantum-resistant cryptography evaluation, and energy-aware security modeling. The comprehensive nature of these requirements necessitates a powerful exercise definition schema (proposed in Section 5.6) to orchestrate complex, multi-faceted 6G validation scenarios.

4.3. A Classification of Cyber Security Exercises for Evolving Mobile Networks

To contextualize next-generation CR requirements, Table 3 presents a classification of cybersecurity exercises that reflects the evolution of mobile network technology. This hierarchical classification illustrates how exercise scope, complexity, and threat sophistication have progressed from foundational cybersecurity principles through 5G core architectures to the specialized exercises required for O-RAN and 6G. Each level identifies the primary security focus, exercise types, key technologies, and corresponding CR requirements.

Table 3.

A hierarchical classification of cybersecurity exercises for evolving mobile networks.

5. Theoretical Framework for a Next-Generation Cyber-Range

To effectively confront the escalating and multifaceted security challenges identified by the O-RAN WG11, the integration of Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML) and the novel architectural paradigms anticipated for 6G, and the development of a next-generation CR (NG-CR) are essential. Such a platform should be significantly more sophisticated, flexible, modular, and demonstrably intelligent architecture compared to 5G CR. The ambition of this framework extends beyond the known network elements; it must also serve as a robust proving ground for entirely novel security mechanisms, tested against emergent and exceptionally complex threat scenarios. At its core, the design philosophy prioritizes a high-fidelity representation of O-RAN’s open interfaces and components, facilitates the generation of dynamic and adaptive scenarios, and ensures seamless integration with proactive and continuous risk management processes.

Our proposed architecture differs fundamentally from prior 5G cyber-ranges like SPIDER [25,26], which employed a monolithic emulation framework centered on a centralized Emulation Instantiation Manager coordinating pre-configured 5G Core Network Functions (AMF, SMF, UPF, NRF) through a Vertical Application Orchestrator (VAO) interfacing with MANO-based NFV orchestration and a vSOC pipeline leveraging GAN-based synthetic attack traffic generation. In contrast, our framework introduces eight disaggregation-native modular layers specifically designed for O-RAN’s open interfaces, intelligent controllers, and multi-vendor security validation—architectural requirements absent in 5G-core-focused designs.

5.1. Modular Architecture

A carefully designed multilayer and modular architecture forms the bedrock of this proposed next-generation cyber-range, for ensuring adaptability to evolving standards, scalability to accommodate immense complexity, and the seamless ability to integrate emerging O-RAN and nascent pre-6G components as they are defined and developed. Each distinct layer within this architecture provides highly specialized functions, all contributing synergistically to a holistic and comprehensive emulation environment:

The Infrastructure Layer underpins the entire framework, providing the fundamental physical or cloud-based resources, encompassing the necessary Compute, Storage, and Network capabilities required to host and operate the cyber-range. This layer must be capable of supporting the diverse physical or cloud-based resources utilized in contemporary O-RAN testbeds, such as those detailed in the NIST TN 2311 deployment blueprint, which includes bare-metal servers and cloud orchestrators like Kubernetes [23]. The Infrastructure Layer is not just a passive pool of hardware—it is utilized as an active resource manager responsible for tracking availability, enforcing quotas, and providing isolated resource slices to the layers above, as directed by the Orchestration and Control Layer.

Crucially, the Virtualization/Cloud Layer must achieve a high degree of accuracy in emulating the O-Cloud environment—incorporating Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) and Container-as-a-Service (CaaS)—precisely as defined by O-RAN WG6 O2 Interface specifications [46] and Cloud Architecture [81]. This includes the accurate representation of its specific Network Function Virtualization Infrastructure (NFVI), Virtualized Infrastructure Managers (VIMs), Kubernetes deployments, and, of critical security importance, the O2 management interface, which is increasingly recognized as a key target for sophisticated cyber-attacks. Furthermore, this layer must be capable of supporting the instantiation of O-RAN Network Functions (O-NFs) with realistic resource constraints, complex inter-dependencies, and accurate performance characteristics. The NIST guide [23] details deployments using Kubernetes for the OSC Near-RT RIC, and our framework must provide a realistic emulation of such cloud-native environments to test O-Cloud-specific vulnerabilities (e.g., T-O-CLOUD-ID-xx, T-VM-C-xx from WG11 [42]) and the security of O2 interactions.

The Network Emulation Layer is tasked with creating configurable and dynamic virtual network topologies that interconnect all emulated components. It must simulate realistic network impairments (such as latency, jitter, and packet loss) and provide strategically located points for comprehensive traffic monitoring and precise threat injection across all defined O-RAN interfaces. This layer’s responsibilities also extend to the accurate replication of the complex xHaul transport network—including Fronthaul, Midhaul, and Backhaul segments—including the critical aspects of timing and synchronization (e.g., Precision Time Protocol (PTP)), as specified by O-RAN WG4 Fronthaul [45] and WG9 Synchronization [82] specifications. The integrity and security of these transport and synchronization mechanisms are vital for overall RAN functionality and present unique security considerations that must be addressed within the CR.

A cornerstone of the proposed framework is the Component Emulation Layer. This layer is dedicated to hosting high-fidelity emulators for all logical O-RAN nodes—specifically, the O-RU, O-DU, O-CU, Near-RT RIC, Non-RT RIC, and the SMO—along with their intricate internal functions and behavioral characteristics, reflecting O-RAN WG1 Architecture Description (R004-v13.00) [43], WG2 Non-RT RIC (R004-v06.00) [61], and WG3 Near-RT RIC (R004-v07.00) [44] specifications. An essential characteristic of this layer is its modular capability, which must extend to supporting diverse vendor implementations of O-RAN components alongside open-source alternatives (such as those emerging from the O-RAN Software Community (OSC)). This capability is fundamental for enabling realistic multi-vendor interoperability testing scenarios and the associated, often complex, security assessments. Moreover, this layer must be designed with inherent extensibility to accommodate the integration and testing of early-stage 6G functional blocks as these become more clearly defined by standardization bodies.

The AI/ML Layer extends the role of a hosting platform for AI models; this dedicated and sophisticated environment must facilitate comprehensive lifecycle management and rigorous security testing of AI/ML models specifically within the O-RAN operational context. This entails accurately emulating RIC platforms (both Near-RT and Non-RT variants) along with their specified AI/ML workflow capabilities, as specified in O-RAN WG11 AI/ML Security Study (R004-v04.00) [54] and WG3 Near-RT RIC specifications [44]. It involves hosting realistic simulators for xApps and rApps, integrating advanced AI-specific attack-generation tools (for example, tools designed to execute adversarial machine learning attacks, data poisoning campaigns, or model theft attempts), and enabling the thorough testing of defensive mechanisms designed to protect the AI models themselves. The functionality of this layer is therefore critical for addressing the spectrum of AI-related threats identified in O-RAN WG11’s AI/ML security analyses and explored in research on attacking xApps [52].

The Threat Injection Engine must be a sophisticated and versatile module, capable of injecting a diverse array of threats across multiple layers of the emulated O-RAN architecture—spanning the network, virtualization, application, and even AI model layers. Crucially, this engine must be capable of launching complex, multi-stage attack campaigns that can intelligently traverse different O-RAN domains and layers, with attack scenarios directly mapped to the threat models documented by O-RAN WG11 Threat Model (R004-v05.00) and Security Protocols Specification (R004-v11.00) [42,47] and also considering emerging 6G-specific threat vectors. To ensure comprehensive testing of adaptive defenses, it should support both pre-scripted adversary behavior and the more dynamic, unpredictable actions of AI-driven adversaries. The types of security tests conducted by the 5GSTB (e.g., mTLS bypass attempts, unauthorized VNF attach) also inform the capabilities required by this engine [34,35].

The Telemetry and Monitoring Layer is responsible for the exhaustive collection of logs, performance metrics, and critical events from all active layers and emulated components within the cyber-range. This layer’s data acquisition capabilities must extend beyond capturing just network traffic; it must also collect detailed information regarding the internal data of O-RAN components, decision logs from the RICs, performance metrics of AI models, and security alerts. Such detailed telemetry is absolutely crucial for conducting in-depth forensic analysis post-incident and for gaining a granular understanding of the impact of various attack scenarios.

Finally, the Orchestration and Control Layer serves as the central nervous system of the CR; it manages the complete lifecycle of scenarios, including their definition, automated deployment, controlled execution, user interaction modalities, and the seamless integration of all other architectural layers. Beyond managing static scenarios, this layer must possess the advanced capability to orchestrate dynamic, evolving environments where network conditions, trust relationships between components, and even threat actor behaviors can change in real-time, thereby reflecting the highly adaptive and autonomous nature envisioned for future 6G networks. The automation capabilities detailed in frameworks like 5G-CT [83] and AutoRAN [60] underscore the need for a sophisticated orchestration layer. It must manage the lifecycle of complex scenarios involving various O-RAN components (potentially from multiple vendors, as explored in testbeds like X5G [84]) and dynamic threat–actor behaviors, especially for training and adaptive defense validation.

The sophistication of this layer is enabled by the Exercise Definition Schema (EDS) detailed in Appendix B. Moving beyond static scripts, the Orchestrator uses the schema to implement dynamic, event-driven scenario adaptation. This is achieved through the dynamicAdaptationRules defined in the schema’s Scenario Execution Logic domain. These rules allow the Orchestrator to monitor for triggers—such as a Blue Team’s successful mitigation of a threat, a specific time elapsing, or a telemetry threshold being crossed—and execute predefined actions in response. For example, a rule could dynamically increase the exercise’s complexity and resource footprint by deploying new components from the topology definition, or scale down resources during idle periods to optimize infrastructure usage. This entire sequence operates as a continuous feedback loop within the Execution Phase of the Operational Workflow (Section 5.8), transforming a static exercise into a responsive, intelligent, and cost-effective validation environment.

5.2. Conceptual Topology for O-RAN Emulation

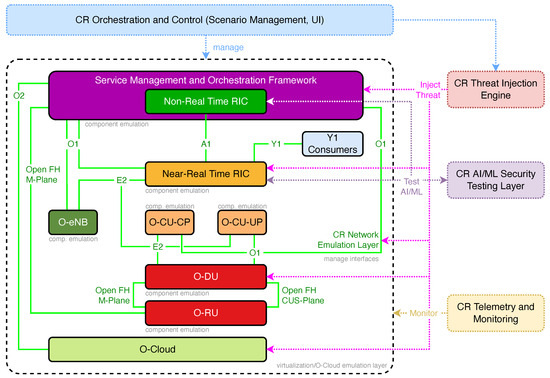

The synergistic integration of these modular layers, when instantiated for the specific purpose of O-RAN security validation, culminates in a comprehensive emulation topology, as conceptually depicted in Figure 1. This diagram illustrates the high-level architecture of the proposed next-generation CR (NG-CR), demonstrating how key emulated O-RAN components are logically arranged and interconnected, and how the specialized cyber-range services interact with this emulated O-RAN environment to facilitate security testing and training exercises.

Figure 1.

Theoretical topology of a next-generation cyber-range for O-RAN emulation, illustrating key O-RAN components, interfaces, and interacting cyber-range services.

At the top of the architecture resides the CR Orchestration and Control layer, driven by the detailed Exercise Definition Schema (EDS). This layer is responsible for overall scenario management and user interaction. This layer directly manages the emulated Service Management and Orchestration (SMO) Framework, within which the Non-Real Time RIC (itself a critical emulated component) operates. The SMO, in turn, exercises control and management over other O-RAN Network Functions (NFs) via the O1 and O2 interfaces.

The core of the emulated O-RAN Radio Access Network comprises the Near-Real Time RIC, the disaggregated base station functions including the O-CU-CP, O-CU-UP, O-DU, and one or more O-RU instances. An O-eNB is also shown to illustrate the applicability of the E2 interface to other E2 Node types. These elements are primarily realized through the Component Emulation Layer of the cyber-range framework. The O-CU and O-DU components, often deployed as Virtualized or Containerized Network Functions (VNFs/CNFs), are hosted upon the emulated O-Cloud, which represents the Virtualization/O-Cloud Emulation Layer.

Crucially, these O-RAN components are interconnected by the CR Network Emulation Layer, which is responsible for managing and simulating the O-RAN defined open interfaces (per WG1, WG2, WG3, WG4, WG6 specifications), depicted by solid green lines in Figure 1. These include the A1 interface between the RICs, the E2 interface from the Near-RT RIC to E2 Nodes (O-CU-CP, O-DU, O-eNB), the O1 interface for management from the SMO, the O2 interface between the SMO and O-Cloud, the Y1 interface for data consumers, and the multi-plane Open Fronthaul interface between the O-DU and O-RU.

Interacting with this emulated O-RAN environment are the specialized services of the next-generation CR (NG-CR), shown on the right-hand side of Figure 1. The CR Threat Injection Engine introduces threats into the emulated components and interfaces. The CR Telemetry and Monitoring layer collects vital logs, metrics, and security events from across the emulated O-RAN stack. The CR AI/ML Security Testing Layer engages explicitly with the intelligent O-RAN components (Near-RT RIC and Non-RT RIC) to validate their AI/ML models and to test for AI-specific vulnerabilities. These conceptual interactions, represented by dashed lines, signify the cyber-range’s operational capabilities to actively probe, observe, and assess the security posture of the emulated O-RAN system during exercise execution. This integrated topology thereby provides a robust and realistic platform for the O-RAN specific cybersecurity exercises detailed later in this paper (e.g., Section 5.5).

5.3. Functional Capabilities

To address the new security challenges posed by O-RAN and 6G, this next-generation framework requires advanced capabilities beyond current 5G cyber-ranges, such as the SPIDER platform.

High-fidelity O-RAN emulation. This means accurately modeling O-RAN component behaviors (like RIC control loops, xApp/rApp interactions, and SMO functions) and precisely emulating O-RAN interface protocols and service models (e.g., E2AP with E2SMs per WG3, A1 policies per WG2, O1/O2 transactions per WG1/WG6, R1 services per WG1/WG2) as defined in O-RAN specifications [43]. High fidelity is key to identifying subtle vulnerabilities that are missed by simpler simulations. This demands accurate modeling as seen in digital twin initiatives like Colosseum [29] and practical O-RAN testbed deployments guided by NIST [23], ensuring that the interface protocols are precisely emulated.

Integrated AI security testing. The framework must offer specialized tools for testing vulnerabilities within the O-RAN AI/ML ecosystem. This includes assessing xApp/rApp robustness against adversarial inputs, detecting data poisoning in RIC training data, and testing the security of AI model lifecycle management by the SMO and RIC. This capability directly addresses the vulnerabilities highlighted in studies on adversarial attacks in O-RAN [52] and the need for robust AI testing frameworks [53]. It moves beyond the functional AI/ML development supported by platforms like OpenRAN Gym [28] to focus specifically on security validation.

Dynamic trust and zero-trust architecture simulation. The cyber-range must model and test ZTA policy enforcement across the disaggregated O-RAN landscape. The 5GSTB’s validation of mTLS as an enabler for Zero Trust in 5G core networks [34] highlights the importance of ZTA. Our framework extends this by enabling rigorous testing of ZTA policies across the disaggregated O-RAN landscape, building on WG11 ZTA studies.

Comprehensive multi-vendor scenario support. The framework should easily integrate and test emulated O-RAN components from different vendors. This is vital for validating interoperability and analyzing security issues arising from varied specification interpretations or vendor-specific extensions.

Advanced federated simulation capability. The architecture should allow connections to other specialized cyber-ranges (e.g., RF modeling, ICS security, quantum computing testbeds) or physical components. This enables comprehensive end-to-end security validation across diverse domains and technologies.

Sophisticated scenario orchestration. Beyond static attack scripts, the framework must automate complex, multi-stage attack campaigns that adapt across O-RAN domains and layers. It should simulate adaptive attackers modifying their Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs) based on network responses, to rigorously test AI-driven defenses.

Enhanced red/blue/purple team training. The cyber-range must provide realistic O-RAN and AI-specific training scenarios, along with advanced attack tools and monitoring dashboards. This helps security teams develop hands-on skills and supports Purple Teaming exercises for collaborative defense strategy development.

5.4. Integration with Risk Evaluation

A key feature of this next-gen cyber-range is its built-in support for an ongoing, adaptive risk management lifecycle, moving beyond static assessments:

Direct scenario mapping to modeled threats. Exercises must link directly to specific threats and vulnerabilities in authoritative models, like those from O-RAN WG11 [42]. This ensures that training and testing are relevant to both known and emerging O-RAN/6G risks.

Quantitative defense validation. The platform must measure the effectiveness of security controls (e.g., interface encryption strength, xApp validation efficacy) when under simulated attack. This provides evidence-based validation, especially for O-RAN-specific controls detailed by WG11.

Adaptive risk scoring. The cyber-range should help dynamically update risk scores for threats or O-RAN components based on exercise outcomes, aligning with ISO 27005 [79] principles. This feedback loop helps organizations prioritize security investments and adapt defenses as new threats are understood via simulation.

Comprehensive forensic logging. The platform needs detailed, time-synchronized logs from all emulated components and layers. Accurate logs are vital for post-exercise forensic analysis, reconstructing O-RAN-specific attack paths, and refining incident response plans.

5.5. Illustrative Application: STRIDE-Based O-RAN Exercises on the Next-Gen Cyber-Range

The previous sections detailed the framework for a next-generation cyber-range. To show how it can be used to address O-RAN-specific security issues, this section outlines some example cybersecurity exercises. These exercises follow the STRIDE (Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, Denial of Service, Elevation of Privilege) threat model. Each scenario highlights unique O-RAN vulnerabilities and shows why the proposed cyber-range capabilities are essential for useful security validation and training. Appendix A provides detailed profiles for each exercise.

5.5.1. Spoofing Threats and Exercises

In O-RAN, spoofing means an attacker pretends to be a trusted component, user, or process. Because O-RAN is disaggregated, uses many open interfaces, and introduces new intelligent parts like RICs, there are more ways to spoof it compared to older RANs. Successful spoofing can lead to problems like unauthorized data access, network manipulation, service denial, or the creation of a backdoor for more attacks. The exercises S1: Rogue O-RU with Fronthaul Replay (Table A1 and Table A2), S2: Malicious A1 Policy Injection via Spoofed Non-RT RIC (Table A1 and Table A2), and S3: E2 Node Identity Forgery and False Reporting (Table A1 and Table A2) show attacks on key O-RAN spoofing targets. These examples highlight why advanced emulation is needed to test defenses against these identity-based threats (Appendix A).

These spoofing exercises (S1, S2, S3) show the need for strong identity management, authentication across all O-RAN interfaces, and good monitoring. AI-based threat detection that looks for unusual behavior across components and interfaces can also help catch such attacks. Specifically, the “Rogue O-RU” exercise tests defenses against impersonation at the RAN edge. The “Malicious A1 Policy Injection” and “E2 Node Identity Forgery” exercises focus on securing control loops managed by the RICs. Our proposed cyber-range, with its accurate O-RAN component emulation, advanced threat injection, and detailed telemetry, is vital for testing these security measures and training staff to handle O-RAN’s unique impersonation threats.

5.5.2. Tampering and Repudiation Threats and Exercises

Tampering in O-RAN refers to unauthorized changes to data, software, or configurations, which can break the network. Open interfaces and programmable components like xApps/rApps create new opportunities for this. Cyber-range exercises must simulate various tampering scenarios to test detection and response. The tampering exercises T1, T2 (Table A1 and Table A3) stress the importance of data and configuration integrity, showing the need for strong integrity protection on open interfaces and secure management of intelligent apps. Our cyber-range, with its detailed emulation, precise threat injection, and full telemetry, allows thorough testing of these safeguards and trains staff to handle tampering.

Repudiation threats involve an entity denying it performed an action, which is complicated by O-RAN’s distributed nature and third-party apps. Strong non-repudiation, through secure logging and cryptographic integrity, is key for accountability. Exercises include R1: Disputed O1 Configuration Change (Table A1 and Table A4), R2: Attributing Malicious xApp Activity (Table A1 and Table A4), and R3: Verifying rApp Policy Provenance (Table A1 and Table A4). These exercises show that tracing actions to their source is vital. The cyber-range’s focus on secure telemetry and accurate component emulation (including logging) is essential for testing non-repudiation and training for O-RAN forensic investigations.

5.5.3. Information Disclosure Threats and Exercises

Information Disclosure in O-RAN means that sensitive data is exposed to unauthorized parties. Many open interfaces, disaggregated components, cloud hosting, and data-heavy AI-driven RICs increase the risk of data leaks. The exercises here focus on identifying and fixing these issues. Examples are I1: xApp Data Exfiltration via Y1 Interface (Table A1 and Table A5) and I2: O-Cloud VNF Snapshot Exposure (Table A1 and Table A5), targeting different O-RAN layers.

These exercises (I1, I2) are important for checking confidentiality in O-RAN. They show the various ways sensitive RAN data can be exposed. The proposed cyber-range, by emulating specific O-RAN interfaces (like Y1), O-Cloud environments, and providing detailed telemetry, allows strict testing of access controls, data encryption, and data leak prevention. These exercises help defenders respond to disclosure threats in open, distributed systems.

5.5.4. Denial of Service and Elevation of Privilege Threats and Exercises

DoS attacks aim to render O-RAN components or services unavailable, thereby threatening network reliability. O-RAN’s disaggregated nature and interconnected intelligent controllers create many DoS targets. Simulating these attacks is key to testing resilience. Examples include D1: E2 Interface Flood against Near-RT RIC (Table A1 and Table A6), D2: O-RU Resource Exhaustion via Open Fronthaul (Table A1 and Table A6), and D3: xApp-Induced RIC Resource Starvation (Table A1 and Table A6) (see Appendix A). These scenarios (D1, D2, D3) show how O-RAN creates new DoS targets. They need a cyber-range that can simulate heavy traffic, model resource use across components, and monitor performance under stress. The framework’s Network Emulation, Component Emulation, and Telemetry are thus vital for testing DoS resilience and training.

Elevation of Privilege (EoP) attacks in O-RAN aim to give an attacker higher permissions to bypass controls and gain administrative access. O-RAN’s software-heavy design, use of xApps/rApps, and complex component interactions create opportunities for EoP. Exercises must simulate these to test preventive controls. Examples include E1: xApp Sandbox Escape (Table A1 and Table A7), E2: O-Cloud Container Escape (Table A1 and Table A7), and E3: O1 Interface Vulnerability for SMO Admin Access (Table A1 and Table A7) (see Appendix A). These EoP exercises (E1, E2, E3) are critical for testing defense-in-depth. They show how attackers can escalate privileges. The cyber-range’s ability to emulate detailed component internals (like RIC sand-boxing or vulnerable O-Cloud runtimes), along with good threat injection and telemetry, is key for validating containment and least-privilege principles.

5.6. A Schema-Driven Approach to Scenario Orchestration

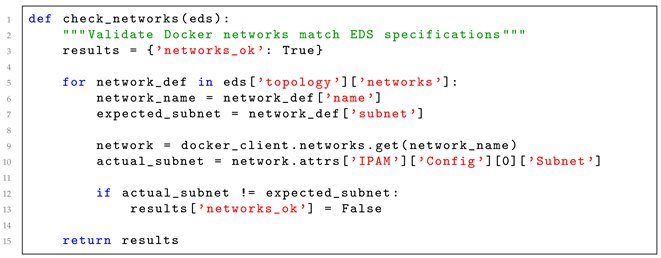

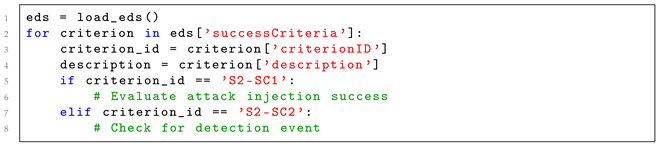

To enable the complex, dynamic, and federated scenarios required for O-RAN and 6G, our framework relies on a comprehensive Exercise Definition Schema (EDS). This schema moves beyond simple scripting to provide a structured, machine-readable format that captures the full lifecycle and state of a security exercise. It is designed to be the authoritative source of truth that drives the Orchestration and Control Layer. The EDS is conceptually organized into several key domains, each addressing a critical aspect of modern cybersecurity validation. A full conceptual breakdown is provided in Appendix B, but the core domains include:

- Core Metadata and Objectives: This domain defines the exercise’s identity, learning goals, and technical validation objectives, linking every scenario to a clear purpose and measurable success criteria.

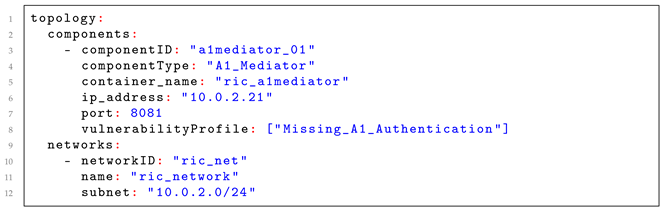

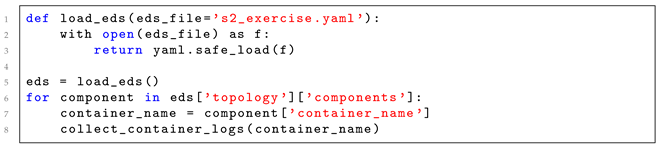

- Emulated Environment and Topology: This is where the virtual world is built. It defines the O-RAN and 6G components (RICs, O-DUs, xApps), their software stacks, and any special hardware requirements (e.g., GPUs for AI, SDRs for RF). Crucially, it allows the injection of specific vulnerabilities (e.g., CVEs, weak credentials) into components and defines the properties of the interconnecting O-RAN interfaces.

- FCR Specifics: For multi-range exercises, this dedicated domain defines node affinity rules (e.g., ensuring an O-DU and O-RU run on the same physical node), inter-node link requirements, and trust policies between federated sites.

- Scenario Execution Logic: This is the dynamic heart of the schema. It defines the scenario’s phases, scripted events, and the attacker model (from simple scripts to adaptive AI adversaries). Most importantly, it contains the dynamic adaptation rules—the conditional ‘IF-THEN’ logic that allows the orchestrator to modify the scenario in real-time based on participant actions or telemetry events.

- Participant Roles, Scoring, and Visualization: Finally, the schema defines the roles of participants (Blue Team, Red Team), their permissions, the tools available to them, and the rules for automated scoring. It also specifies how telemetry data should be visualized on role-specific dashboards.

This schema-driven approach is fundamental to the framework’s capabilities. It enables not only the automation of complex deployments but also the creation of truly adaptive and responsive exercises that can scale in difficulty, react to participant behavior, and provide rich, objective-based assessments—all of which are essential for securing the intelligent and disaggregated networks of the future.

5.7. Federated Cyber-Range Architecture for O-RAN/6G

While the modular architecture from Section 5 outlines a comprehensive next-gen cyber-range, a key question is whether a single, standalone cyber-range can truly handle the vast scale and specialized needs of the entire O-RAN ecosystem and its path to 6G. The full complexity includes potentially thousands of separate O-RUs, O-DUs, and O-CUs; multiple RICs running many demanding xApps/rApps; a complex SMO; a detailed O-Cloud; and numerous high-speed, low-latency open interfaces. Bringing all the necessary emulation power and resources into a single environment faces significant challenges in cost, management, and achieving consistent simulation accuracy across the entire environment at once.

This framework, therefore, suggests that an FCR is a more practical and effective way to achieve thorough O-RAN and 6G security validation. This federated approach is particularly critical for 6G, as it requires cross-domain, zero-touch orchestration and blockchain-enabled trust in the latest 6G security vision [2,4]. The deep complexities of 6G systems—with distributed Zero Trust areas [9], collaborations between multiple operators, specialized technologies like quantum computing testbeds or dedicated RF ranges for tactical uses [7], and the complex automation needed for Zero Touch Networks (ZTNs) [4]—make a single, all-encompassing cyber-range increasingly impractical. Blockchain-based trust frameworks [75] can facilitate secure inter-domain orchestration and immutable audit trails across federated nodes, enabling transparent security exercise coordination without centralized trust authorities. Developing FCR capabilities is already an active research area, with efforts like the European Defence Agency’s project and academic studies looking into strong federation models [85,86,87]. The modular design of our proposed framework (Section 5) is specifically built to support this federated model, allowing different, specialized cyber-range setups to work together.

Theoretical implementation within the framework. A federated setup uses the modular layers described earlier, spreading them across connected cyber-range nodes. Different federated nodes could host specific layers or parts based on their strengths. For example, one node might excel at high-fidelity O-Cloud and Virtualization Layer emulation, offering realistic Kubernetes/NFVI environments for testing cloud-native security. Another could focus on the AI/ML Layer and Component Emulation for RICs, with advanced AI attack tools and detailed xApp/rApp lifecycle simulators. A third might provide specialized Network Emulation for the Open Fronthaul, including precise timing and CUS-plane data, perhaps even linking with SDR hardware for physical layer tests. Vendor-specific emulations or Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) setups could also serve as dedicated federated nodes.

5.7.1. Inter-Federation Interfaces

As O-RAN and 6G systems grow in complexity, a single, monolithic cyber-range becomes untenable. The sheer scale and diversity—from specialized radio hardware emulators to complex AI/ML testbeds—mandate a federated approach. Our experience in building and operating large-scale testbeds confirms that federation is not an option but a necessity. The goal is to allow specialized centers of excellence to contribute their unique capabilities—be it a high-fidelity O-Cloud simulation, a vendor-specific HIL rig, or an advanced RF threat generator—to a larger, coherent security exercise.

However, connecting these nodes requires a set of Inter-Federation Interfaces that are far more capable than what exists today. Standards like STIX/TAXII or TLP [88,89] are useful for sharing threat intelligence but are fundamentally unsuited to the real-time data and control exchange that a live O-RAN exercise demands. Their latency and lack of state management render them ineffective for this application.

A realistic federation model must therefore address challenges across four distinct logical planes. We define these as follows:

- (a)

- The federated orchestration plane. This plane manages the scenario lifecycle across all participating ranges. The challenge here is not just launching VMs; it is maintaining a synchronized state across disparate administrative domains. Current cloud orchestration tools lack the robust, cross-domain failure-handling and resource-negotiation protocols required for this task. A failure in one node must be managed gracefully without collapsing the entire federated exercise.

- (b)

- The federated control plane. This plane must route simulated O-RAN control traffic (e.g., E2, A1, O1) between components hosted on different physical ranges. The primary obstacle is a complex physics problem: latency. Consider the Near-RT RIC’s 10 ms control loop; it fails if the physical network latency between the federated RIC and the O-DU emulators exceeds 50 ms. This plane, therefore, requires either dedicated low-latency interconnects or an advanced network emulation layer that can precisely compensate for physical delay to present an accurate, emulated latency to the systems under test.

- (c)

- The federated data plane. Handling high-bandwidth traffic, particularly the multi-Gbps Open Fronthaul, is the clear bottleneck for any wide-area federation. As practitioners know, routing this traffic between geographically distant sites over a standard WAN is infeasible. This imposes a critical design constraint: data-plane-intensive components like the O-DU and its connected O-RUs must likely reside within a single federated node. Federation is therefore best suited for separating control elements (like the SMO) from the RAN components, not for splitting the RAN itself across a continent.

- (d)

- The federated telemetry plane. To create a coherent view, this plane must aggregate logs, metrics, and alerts from all nodes. The non-negotiable requirement is time synchronization. Without a common, trusted time source (likely using the Precision Time Protocol, PTP) providing nanosecond-level accuracy, correlating a cause on Range A with an effect on Range B becomes forensically impossible. Without synchronized time, forensic analysis becomes an exercise in guesswork.

Ultimately, creating a functional FCR is a deep systems integration problem, not a simple matter of defining a new API. While the challenges are significant, we believe this distributed model is the only viable path to achieve the scale and specialization needed to secure future networks. The next step for the research community is to move beyond adapting intelligence-sharing standards and begin defining a new set of protocols built expressly for the purpose of real-time, cross-range cyber exercise federation.

5.7.2. Illustrative FCR Exercises

An FCR allows for security exercises that would be hard or impossible in a single cyber-range. For example, one such exercise (F1: Cross-Domain E2E Slice Security Validation) could simulate an end-to-end network slice that spans two federated CR nodes. This might represent a private enterprise O-RAN domain connected to a public MNO O-RAN domain. The exercise would test if security policies, like ZTA policies [3,8,10], are consistently applied across this boundary. It could also involve checking secure inter-slice communication as per 3GPP standards [90] or testing slice isolation against MEC-based attacks [91]. Such a scenario clearly needs orchestration across two distinct security domains, simulation of inter-domain interfaces, and correlated monitoring.

Another exercise (F2: High-Fidelity RF Threat Integration) could federate the main O-RAN emulation CR (which handles the O-DU, O-CU, and RICs) with a specialized RF/SDR cyber-range node. This RF node would simulate advanced physical-layer threats, such as sophisticated GPS spoofing that affects Fronthaul timing (as considered by WG9) or intelligent jamming aimed at specific O-RU control channels. The impact on the O-RU (monitored by the RF node) and the subsequent detection and response by the O-DU and RIC xApps (emulated in the main CR) via Fronthaul and E2 telemetry would then be analyzed. This setup integrates highly specialized RF hardware or simulation capabilities and requires real-time telemetry exchange (like O-RU state) and control command relays (from O-DU to O-RU) between the nodes. The RF node could also validate emerging physical layer authentication mechanisms using RFF identification [73,74] to test device identity verification independent of protocol-level credentials.

A third scenario (F3: Distributed RIC Coordination and Conflict Resolution Security) could emulate multiple Near-RT RICs deployed on different federated nodes to represent geographically dispersed edge locations. A Non-RT RIC on a central node would provide A1 policies. This setup would allow simulation of conflicting policy intentions or race conditions that arise from distributed control loops reacting to shared E2 Node data under varying inter-RIC communication latencies. Security mechanisms for detecting malicious A1 policies injected into one edge RIC [67] and their impact on coordinated decisions could be tested. This could also assess the resilience of federated learning approaches across RICs against attacks, drawing on research in federated learning security [78,92]. This exercise requires simulating the geographical distribution and realistic inter-RIC latency, and it requires synchronization of state and policies across multiple intelligent controllers.

Finally, an exercise could focus on the federation mechanism itself (F4: Secure Federation Protocol Testing). Here, the simulation would involve an attacker trying to compromise the federation control plane. This could be achieved by spoofing the identity of a legitimate federated node, injecting malicious scenario commands, tampering with inter-CR telemetry data streams, or launching a DoS attack against the federation’s broker or orchestrator. This exercise would require explicit emulation of the chosen inter-CR communication protocols and their security mechanisms (like authentication, encryption, and integrity checks) to validate their strength.

While our theoretical framework provides the design for the required capabilities, fully realizing them in the O-RAN/6G world likely requires adopting a collaborative, federated approach. This FCR model helps manage complexity, use specialized skills, reach the necessary scale, and perform the realistic multi-domain security tests essential for future network safety.

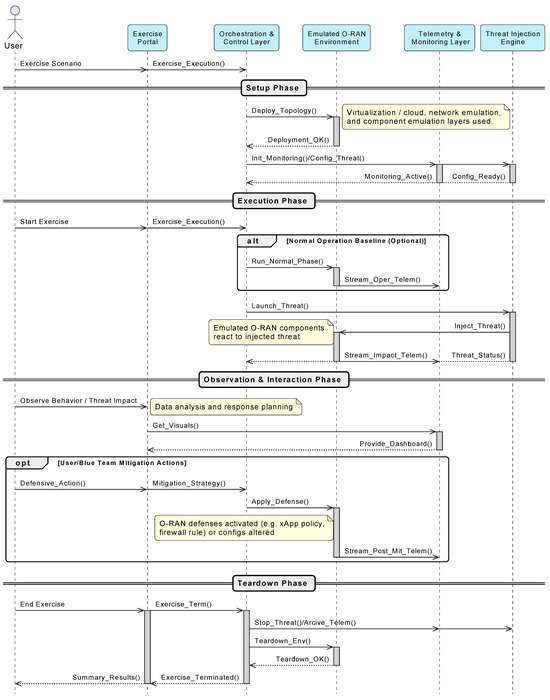

5.8. Operational Workflow of an Exercise Scenario

Beyond the static modular design in Section 5.1, it is important to understand how the parts of the proposed next-gen cyber-range work together dynamically. Figure 2 shows a typical operational flow for a cybersecurity exercise on this platform. Key players and layers include the User/Instructor, the Exercise Portal (UI) (the main user interface part of the Orchestration and Control Layer), the core Orchestration and Control Layer (Orchestrator), the Emulated O-RAN Environment (CEE) (which combines the Virtualization/Cloud, Network Emulation, and Component Emulation Layers), the Threat Injection Engine (TIE), and the Telemetry and Monitoring Layer (TML).

Figure 2.

Operational workflow of a cybersecurity exercise on the next-generation cyber-range, illustrating interactions between key architectural components.

The exercise lifecycle, shown in Figure 2, typically has several phases. The Setup Phase begins when a User/Instructor picks an exercise scenario through the Exercise Portal, triggering a Request_Exercise_Execution to the Orchestrator. The Orchestrator then prepares the environment by sending a Deploy_Emulated_O-RAN_Topology command to the CEE, where the Scenario_Config payload is a complete object instantiating the exercise as defined by the EDS. The CEE uses the detailed architectural layers (from Section 5.1 and Figure 1) for this deployment. Once successful, the CEE sends a Deployment_Successful confirmation. The Orchestrator then sets up the TML with an Initialize_Monitoring command and configures the TIE with a Configure_Threat_Scenario command.

On the Execution Phase, the User/Instructor starts the exercise via the Portal (Start_Exercise), notifying the Orchestrator. An optional normal operation baseline might run first, where the CEE streams Stream_Operational_Telemetry to the TML. Then, the Orchestrator tells the TIE to Launch_Configured_Threat. The TIE interacts with the CEE to inject the threat (Threat_Payload) into specific O-RAN components. The CEE, now affected by the threat, streams detailed Stream_Threat_Impact_Telemetry_And_Alerts to the TML, providing real-time data. The TIE also reports its Threat_Execution_Status to the Orchestrator.

During the Observation and Interaction Phase, the User/Instructor watches the system and the threat’s impact, often using visualizations from the Exercise Portal, which can Request_Aggregated_Data_Visuals from the TML. If the exercise includes defensive actions (like for a Blue Team), the User/Instructor can Apply_Defensive_Action through the Portal. This becomes an Execute_Mitigation_Strategy command for the Orchestrator, which then tells the CEE to Apply_Defense_Configuration_To_Emulation (e.g., changing xApp policies or O-Cloud security groups). Post-mitigation telemetry is then streamed to the TML.

Finally, the Teardown Phase starts when the User/Instructor ends the exercise (End_Exercise) via the Portal. The Orchestrator coordinates stopping the TIE (Stop_Threat_Injection), tells the TML to Finalize_And_Archive_Telemetry, and commands the CEE to Teardown_Emulated_Environment. Once the CEE confirms (Teardown_Successful), the Orchestrator signals Exercise_Terminated to the Portal, which can then Display_Summary_And_Results.

This orchestrated workflow allows complex, multi-stage O-RAN security scenarios, like those in Section 5.5. The AI/ML Security Testing Layer (from Section 5.1) is activated by the Orchestrator for exercises requiring validation of O-RAN AI models or detection of AI attacks, interacting closely with the TML and the CEE.

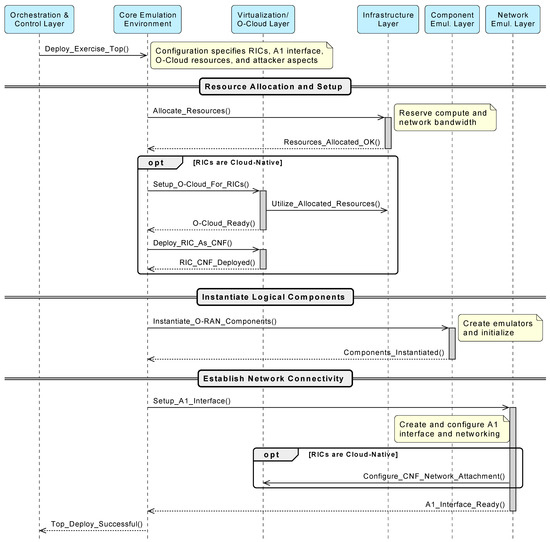

Internal Workflow for Exercise Topology Deployment

Deploying a complex O-RAN exercise topology, such as the “S2: Malicious A1 Policy Injection” scenario (from Section 5.5.1), involves a coordinated sequence orchestrated by the Core Emulation Environment (CEE). When the CEE receives a deployment command from the Orchestration and Control Layer, it assigns tasks to its layers: Infrastructure (IL), Virtualization/O-Cloud (VOL), Component Emulation (CEL), and Network Emulation (NEL), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Internal workflow for Exercise S2 topology deployment within the Core Emulation Environment (CEE), detailing interactions with constituent cyber-range layers.

For an exercise like S2, the deployment unfolds as follows:

- Resource allocation. The process begins with active resource management. The CEE first queries the Infrastructure Layer (IL) to ensure sufficient capacity exists for the scenario’s resource profile as defined in Config. Upon confirmation, the CEE sends a formal Allocate_Resources request. The IL reserves the specific compute, storage, and network resources, returning a set of unique Allocate_Resource_Handles to the CEE. These handles, representing the finite-resource slice for the exercise, are then passed to subsequent commands to the VOL and CEL to enforce the allocation.

- O-Cloud environment setup. If Config specifies cloud-native RICs, the CEE instructs the VOL to Setup_O-Cloud_For_RICs using those resources. The VOL then deploys the RICs as Containerized Network Functions (Deploy_RIC_As_CNF) on the emulated O-Cloud.

- Logical component instantiation. The CEE directs the CEL to Instantiate_O-RAN_Components. The CEL creates emulators for scenario elements such as the target Near-RT RIC, an optional legitimate Non-RT RIC, and an Attacker Node for A1 spoofing. If RICs were deployed as CNFs earlier, the CEL links these logical emulators accordingly.

- Network connectivity establishment. The CEE tasks the NEL to Setup_A1_Interface. The NEL creates and configures the emulated A1 interface between components (e.g., Attacker Node and Near-RT RIC), assigns IP addresses, and sets up routing as per Config. For cloud-native RICs, the NEL collaborates with the VOL to ensure proper network attachment.

Once all these steps are complete, the CEE reports Topology_Deployment_Successful to the Orchestration and Control Layer, indicating that the environment is ready. This detailed internal flow demonstrates the modular and cooperative nature of the framework’s layers, enabling flexible and precise deployment of varied O-RAN security scenarios.

6. Proof-of-Concept

6.1. Proof-of-Concept Implementation and Validation