1. Introduction

A global to-do list for sustainable development is provided by the United Nations Agenda 2030, where 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are identified to eradicate poverty, establish socioeconomic inclusion, and protect the environment [

1] (see

Table 1). The SDGs aim to stimulate actions over the next years in areas of critical importance for humanity and the planet. The main purpose is to ensure that all human beings can enjoy prosperous and fulfilling lives and that economic, social, and technological progress occurs in harmony with nature, including through sustainable consumption and production.

In the realm of this study, we focus on SDG 7, encompassing targets that range from universal electricity access to the promotion of renewable energy and energy efficiency. To contextualize the focus of the present study,

Table 2 summarizes the main SDG 7 targets and their associated indicators, highlighting those that are directly relevant to our analysis. By aligning this study with these targets, we demonstrate how monitoring energy consumption at the local or institutional level can contribute to global efforts to achieve affordable, reliable, and sustainable energy for all.

Monitoring the SDGs is an important challenge and strategic opportunity for stakeholders and beneficiaries involved with the Agenda 2030 at all levels [

2,

3]. Indeed, quantifying progress towards achieving the SDGs enables to track global efforts towards sustainable development and guide policy development and implementation [

4].

However, global sustainability challenges, from including sustainable consumption and production to providing clean air and water, are closely interconnected yet often separately studied and managed. Holistic approaches based on data management and integration are necessary to create sustainability solutions and to assess progress towards achieving the SDGs [

5].

To meet these demands, it is essential to develop robust ICT platforms capable of handling the scale, diversity, and dynamism of monitoring data. Such platforms must rely on Internet of Things (IoT) technologies to continuously collect real-world information from distributed environments. Equally important is the flexibility to process these data at different locations, whether at the edge or near the data source, so that computational resources can adapt to contextual needs [

6,

7]. Furthermore, recent approaches highlight the importance of service management and energy scheduling to achieve low-carbon edge computing goals [

8].

In this context, IoT technologies, combined with edge computing, offer a powerful foundation for scalable platforms that enable effective implementation, efficient operation, and the real-time monitoring of the status and progress of SDGs. IoT ecosystems enable four key operational scenarios: inventory monitoring, sensor-driven data collection, location acquisition, and actuator control [

9]. These services become even more powerful when combined with edge computing, which supports granular, near-source data processing. By reducing latency, edge-enabled IoT infrastructures allow for a scalable monitoring solution. This distributed computing paradigm provides terminal users with high-speed computation at any time and in any location, significantly accelerating the execution and monitoring of SDG-related initiatives.

Although the use of platforms integrating IoT and edge computing is recognized as essential to effective SDG-oriented data collection and processing, to the best of our knowledge, no existing platform integrates these two aspects in a unified framework; the current literature instead provides separate references focusing on 6G–edge [

10] architectures on one side and IoT–5G [

11] solutions on the other.

In this work, we propose the design of a data management software platform tailored for edge–cloud computing environments, where data are collected at distributed edge devices and processed in the cloud. The platform is designed to support the continuous monitoring and quantification of progress toward the SDGs over time, with reference to specific organizations such as universities. User queries regarding sustainability metrics are submitted to the cloud, which aggregates and analyzes edge-collected data to generate actionable insights. As a representative use case, we present the implementation of the energy consumption monitoring module, demonstrating how edge data can be leveraged through cloud-based analytics. This platform has been developed within the framework of the initiatives promoted by the Sustainability and Ecological Transition Center (CSTE) at the University of Palermo.

Given their widespread deployment across university campuses, energy meters serve as a critical backbone for developing smart and sustainable campus environments. In addition to measuring active and reactive energy to quantify the amount of electricity consumed and produced by campus buildings, these meters can incorporate additional sensors to monitor a variety of parameters, such as indoor environmental quality, temperature, occupancy patterns, and equipment performance. Research findings indicate that smart energy-metering systems contribute to achieving several SDGs [

12,

13,

14], including SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being), SDG 13 (Climate Action), SDG 15 (Life on Land), and SDG 12 (Responsible Production and Consumption).

Finally, the designed system can integrate and analyze heterogeneous data streams, providing actionable insights to support monitoring and decision making across multiple SDGs. We remark that the platform is not limited to energy monitoring but is intended as a flexible framework capable of supporting a wide range of sustainability indicators.

2. Related Works

The United Nations Agenda 2030 provides a global framework for sustainable development through its 17 SDGs, which address critical challenges facing humanity and the planet [

1]. Monitoring the progress towards these goals is a complex but essential task for all stakeholders, from global to local levels [

3]. The progress analysis for guiding effective policy development and ensuring accountability in global sustainability is addressed in [

4]. However, the SDGs are highly interconnected, and addressing them in isolation can overlook critical synergies and trade-offs. This has led to calls for more integrated monitoring approaches, such as the development of new indices and frameworks that can capture the complex relationships between and within the goals [

2].

A central theme in recent sustainability research is the necessity of a systems integration approach. In particular, holistic data-driven strategies are essential to understanding and managing the intricate links among environmental, social, and economic systems to achieve global sustainability [

5]. This perspective underscores the need for advanced data management platforms capable of collecting, integrating, and analyzing heterogeneous data from various sources to provide a comprehensive view of an organization’s sustainability performance.

In response to this need, recent research has increasingly focused on leveraging technologies like the Internet of Things (IoT), Wireless Sensor Networks (WSNs), and Big Data. For instance, in [

15], the authors demonstrate the application of the IoT and WSNs for real-time air quality monitoring and energy-saving street lighting systems within a smart city context. Their work showcases how distributed sensor networks can provide the granular data necessary for operational efficiency and environmental monitoring, which are key components of SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy). The “smart city” paradigm is often mirrored in the “smart campus” concept, where universities serve as living laboratories for sustainability initiatives. Furthermore, recent implementations of IoT-based Building Energy Management Systems (BEMSs) have demonstrated how distributed edge computing can effectively manage energy in office buildings by reducing communication delays and cloud computational loads [

16]. Recent advancements have further formalized this through Green IoT frameworks designed specifically to optimize energy consumption and anomaly detection within campus environments [

17]. With this purpose, the authors in [

18] explored the integration of the IoT and Big Data in higher education to enhance digital learning and foster sustainability awareness, directly contributing to SDG 4 (Quality Education). This highlights the potential for leveraging similar technological infrastructures within university settings to monitor operational metrics beyond education, such as resource consumption. A significant component of organizational sustainability, particularly relevant to SDG 7, is energy consumption in buildings. This area presents unique data management challenges. For instance, the authors in [

19] demonstrate the practical application of energy modeling to assess sustainability measures in a detailed case study of residential buildings in North Africa. The work focuses on simulation experiments to quantify the substantial energy savings achievable through interventions such as improving the building envelope and integrating solar technologies, exemplifying the type of granular analysis needed to inform effective strategies. However, conducting such analyses at scale requires robust data, and historically, this has been a major challenge. In [

20], a review on building energy consumption information is performed, highlighting the frequent lack of reliable, consistent, and disaggregated data, which hinders effective analysis and policy making. The work identified a critical information gap that modern data acquisition systems, like the one proposed in our work, aim to fill by enabling automated and continuous data collection. Moreover, collaborative edge–cloud architectures have been proven effective in priority-based residential energy management, ensuring both system reliability and high resource utilization [

21].

In addition to the above contributions, recent studies have specifically explored how edge–cloud architectures enhance data collection and analytics in distributed environments. For example, IoT-based Building Energy Management Systems equipped with distributed edge computing capabilities have demonstrated reduced latency and lower communication loads when processing energy data directly near the source, improving responsiveness and scalability in organizational settings [

11]. Similar approaches are presented in Green IoT frameworks for smart campuses, which leverage edge processing to detect anomalies and optimize energy efficiency before forwarding aggregated insights to cloud services [

17]. Furthermore, priority-based residential energy management systems have highlighted the benefits of collaborative edge–cloud coordination for achieving high resource utilization and reliability [

10]. These works reinforce the importance of combining local, near-device computation with centralized cloud analytics. In contrast with these domain-specific implementations, our platform integrates heterogeneous-meter data acquisition, edge-side aggregation, and cloud-based warehousing within a unified architecture designed explicitly to support the continuous monitoring of SDG-related indicators. Our work focuses on a specific subfield of MEC, namely, distributed computing for metering systems composed of lighting and other resource-constrained devices. In the context of general MEC optimization studies [

22], our platform emphasizes efficient, near-source data processing and aggregation to enable the scalable, real-time monitoring of sustainability indicators under strict resource limitations.

To clearly illustrate the benefit of the selected distributed approach, we compare it with traditional IoT systems and cloud infrastructures in

Table 3. Traditional IoT systems, such as LoRaWAN [

23], are fully centralized and do not support edge-level computation, resulting in higher latency and bandwidth usage. Cloud infrastructure solutions can process multiple data sources but require substantial data transfer to clustering servers, leading to moderate latency and high bandwidth consumption. In contrast, the distributed approach enables in-network and edge-level processing, reducing latency and optimizing bandwidth usage while also supporting multiple communication protocols.

3. Platform General Design

A general software platform for monitoring the SDGs and quantifying progress towards achieving them should provide services in a distributed environment to carry out the following:

The automatic collection of data of various kinds (energy, mobility, waste, etc.) from various sources, even heterogeneous;

The cleaning and integration of such data, through storage in an appropriate reconciled database, as part of the platform;

Decision support based on data monitoring over more or less extended periods of time;

Forecasting and proactive analysis, to determine what needs to be changed to avoid potential damage and to achieve certain objectives.

As part of broader sustainability initiatives, a modular data monitoring platform has been designed using an incremental approach, allowing for the progressive development of independent components over time, starting from a core module focused on a specific objective (e.g., resource consumption).

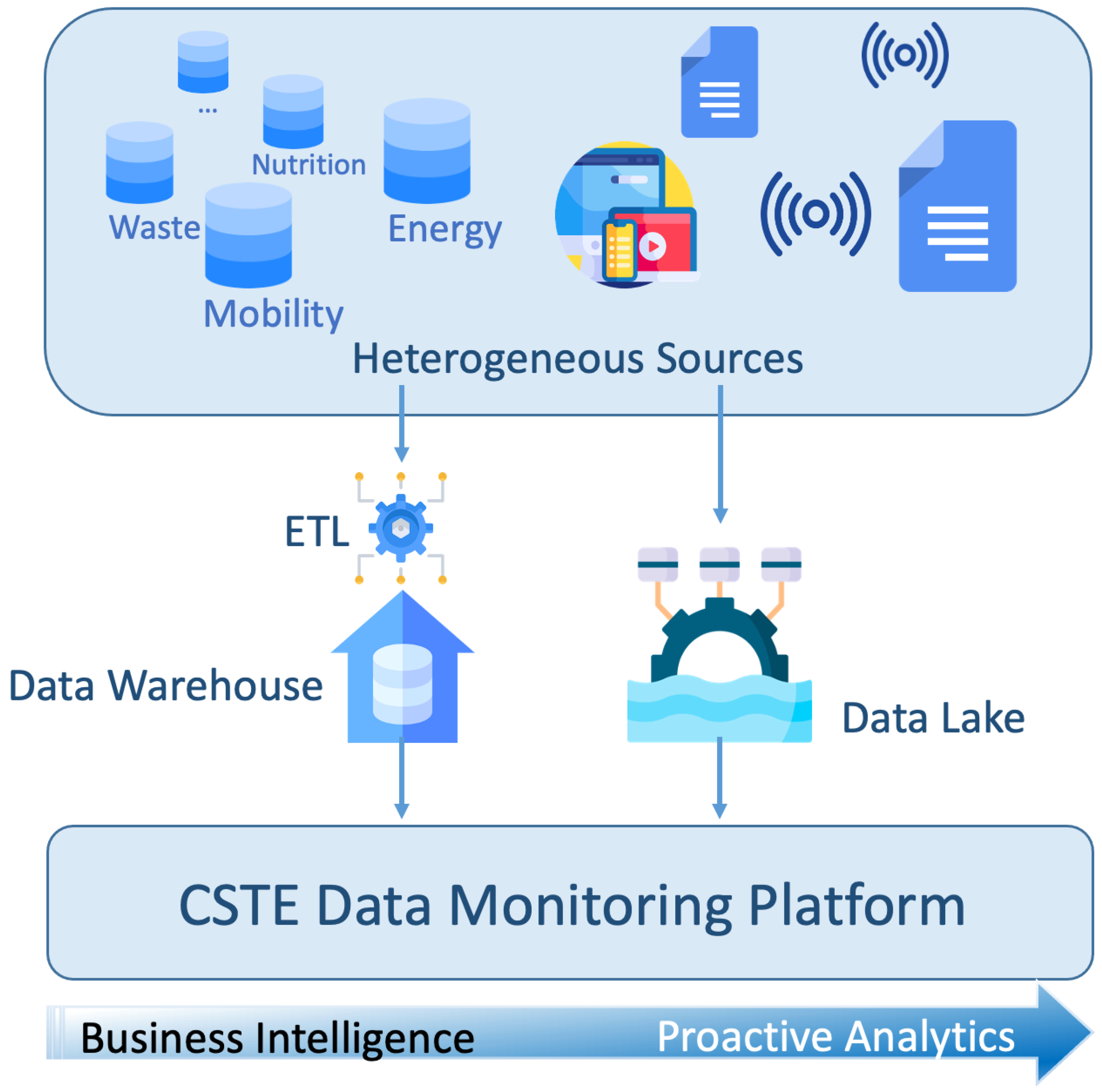

The ultimate goal will be the creation of a complete and reproducible system (see

Figure 1) for the collection, storage, and analysis of data, providing both decision-making queries (Business Intelligence) and predictions, in order to decide future strategies and interventions for Proactive Analytics. In particular, the data that feed the system may be extracted from various heterogeneous sources, including textual documents, spreadsheets, JSON documents, etc. These documents specify the datasets to be monitored, such as energy consumption in university buildings, mobility and waste metrics, geospatial coordinates, and related data.

To incorporate edge processing into the platform, additional components are introduced within the Gateway layer to bridge the gap between source devices and the ETL (Extraction, Transformation, and Loading) tools. These components form a structured architecture in which the Gateway becomes central to enabling the Edge Processing Application (EPA) mechanism. The system employs ModBus communication technology [

24] to connect with environmental monitoring meters and designates Gateways and Fog Devices together as edge elements. At the foundation of this architecture, the EPA mechanism manages the distribution of computational workloads between Gateways and edge processing units throughout the network.

In terms of data flow, monitoring data generated by a meter device are first received by the designated Gateway for processing. We consider a scenario in which all processing occurs at a single point within the Cloud–Edge Computing Continuum (CECC) [

25,

26].

The implemented applications execute time-window aggregation in parallel, computing averages of collected measurements over system-configured intervals. The aggregation algorithm processes incoming data streams and calculates mean values within sliding time windows. By leveraging streaming data processing techniques, the system efficiently generates aggregated summaries that are then transmitted to the cloud, achieving significant dynamic data reduction while preserving essential monitoring information.

At the cloud level, appropriate ETL tools are used to extract data from sources, eliminate inconsistencies, complete missing parts, and integrate, clean up, and load them into a reconciled database. The latter materializes the operational data obtained downstream of the source data integration and cleaning process, creating a consistent and permanent copy that will form an integral part of the platform.

The reconciled database feeds a data warehouse composed of data marts specifically designed to support decision making and monitoring with respect to the metrics and Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) of interest for each SDG (see

Figure 2).

4. The Specific Case of Energy Consumption

One of the main aspects of the designed monitoring platform is the support of decisions to reduce energy consumption inside a university campus. Therefore, the first instance of the platform basic core, which we describe here, focuses on the design of the data mart referred to as the SDG 7

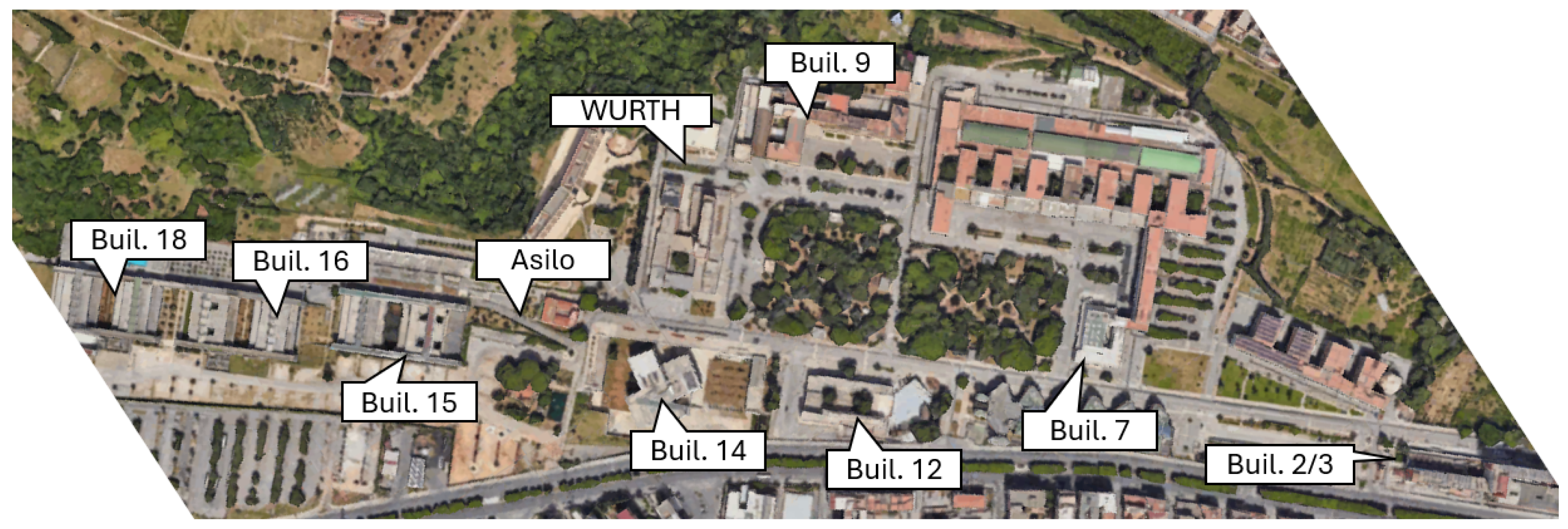

Affordable and Clean Energy. The main goal is to examine the energy consumption patterns of multiple buildings situated within the campus. To this aim, one or more energy-metering devices are installed in each building. As depicted in

Figure 3, the campus of the University of Palermo, the considered case study, comprises 19 buildings, with 25 energy meters distributed across 10 of these buildings as marked in the figure.

In the remaining part of this section, we first describe in detail the system for energy consumption data acquisition that we have designed and developed, according to the physical equipment available at the university campus. Then, we summarize the conceptual and logical design of the data mart, and finally, we show some example query results obtained by using the framework QlikView [

27].

4.1. Data Acquisition System

Energy meters are essential components in power management systems, as they measure energy consumption data. Moreover, network connection ensures seamless communication and data exchange between these devices and the data monitoring platform. Electric data acquisition techniques typically involve several steps and components, listed below:

Sensing: Various sensors are employed to detect changes in the physical world and convert them into electrical signals.

Signal conditioning: The raw electrical signals from sensors often require modifications, such as amplification, filtering, or isolation, to improve signal quality and remove noise before further processing.

Analog-to-digital conversion: Since modern data processing and storage rely on digital formats, analog signals need to be converted into digital values through Analog-to-Digital Converters (ADCs).

Digital data processing: Digital data can be processed using microcontrollers, microprocessors, or dedicated signal processing chips to extract useful information, perform calculations, or apply algorithms.

Communication: Processed data can be transmitted to a central system or other devices via wired or wireless communication protocols (e.g., RS-232, RS-485, Ethernet, Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, or cellular networks) for real-time monitoring, remote control, or further analysis.

Storage: Data can be stored locally on memory devices (e.g., EEPROM, flash memory, or SD cards) or remotely on servers or cloud platforms, allowing for historical trend analysis, troubleshooting, or long-term performance assessment.

In the following, we describe the choices and design steps performed to implement the proposed data acquisition system.

4.1.1. Energy Meters

The energy meters adopted for the proposed system are mostly provided by Schneider Electric, although energy meters from other brands are available, e.g., those proposed by Gavazzi (WM30). The features of energy meters are heterogeneous and depend on the specific product installed. For example, the most adopted devices are the PM750, PM3250, and PM5320 [

28], which are also those present in the considered university campus. Regarding the accuracy class, PM750 and PM3250 have an accuracy class of 0.5S (IEC 62053-22) for active energy measurements, while PM5320 has a higher accuracy class of 0.2S (IEC 62053-22) for active energy measurements, providing more precise data for advanced energy management applications. The products have functionality differences. For example, the PM750 measures basic electrical parameters such as voltage, current, power, and energy. Additionally, it provides limited harmonic analysis up to the 15th harmonic and supports ModBus RTU communication. The PM5320 offers a broader range of measurements, including all the parameters of the PM750 plus extended harmonic analysis up to the 63rd harmonic. It also supports multiple communication protocols, such as ModBus RTU and ModBus TCP/IP, enabling seamless integration into various network configurations.

4.1.2. Communication Technology

The communication technology used to obtain energy meter information is ModBus, which is a widely used, well-established communication protocol that has become standard in various industries, including the energy-metering sector. Originally developed by Modicon (now Schneider Electric) in 1979 for industrial automation systems, it remains a popular choice due to its simplicity, robustness, and open nature [

29]. ModBus operates on a master–slave architecture, where one master device communicates with multiple slave devices within the same network. The master initiates the exchange by sending requests to the slaves, which then respond with the requested data or acknowledge the action. There are three primary variants of the ModBus protocol:

ModBus RTU: A binary-based protocol transmitted over serial communication lines (typically RS-232 or RS-485).

ModBus ASCII: This variant represents data as ASCII characters and is also transmitted over serial lines. While it is more human-readable than ModBus RTU, it is slower and less efficient due to the increased message size.

ModBus TCP/IP: This version of ModBus extends the protocol to work over Ethernet and Internet Protocol (IP) networks, enabling devices to communicate using standard network infrastructure. ModBus TCP/IP retains the core ModBus protocol but encapsulates it within TCP/IP packets, providing higher speed and better compatibility with modern networking equipment.

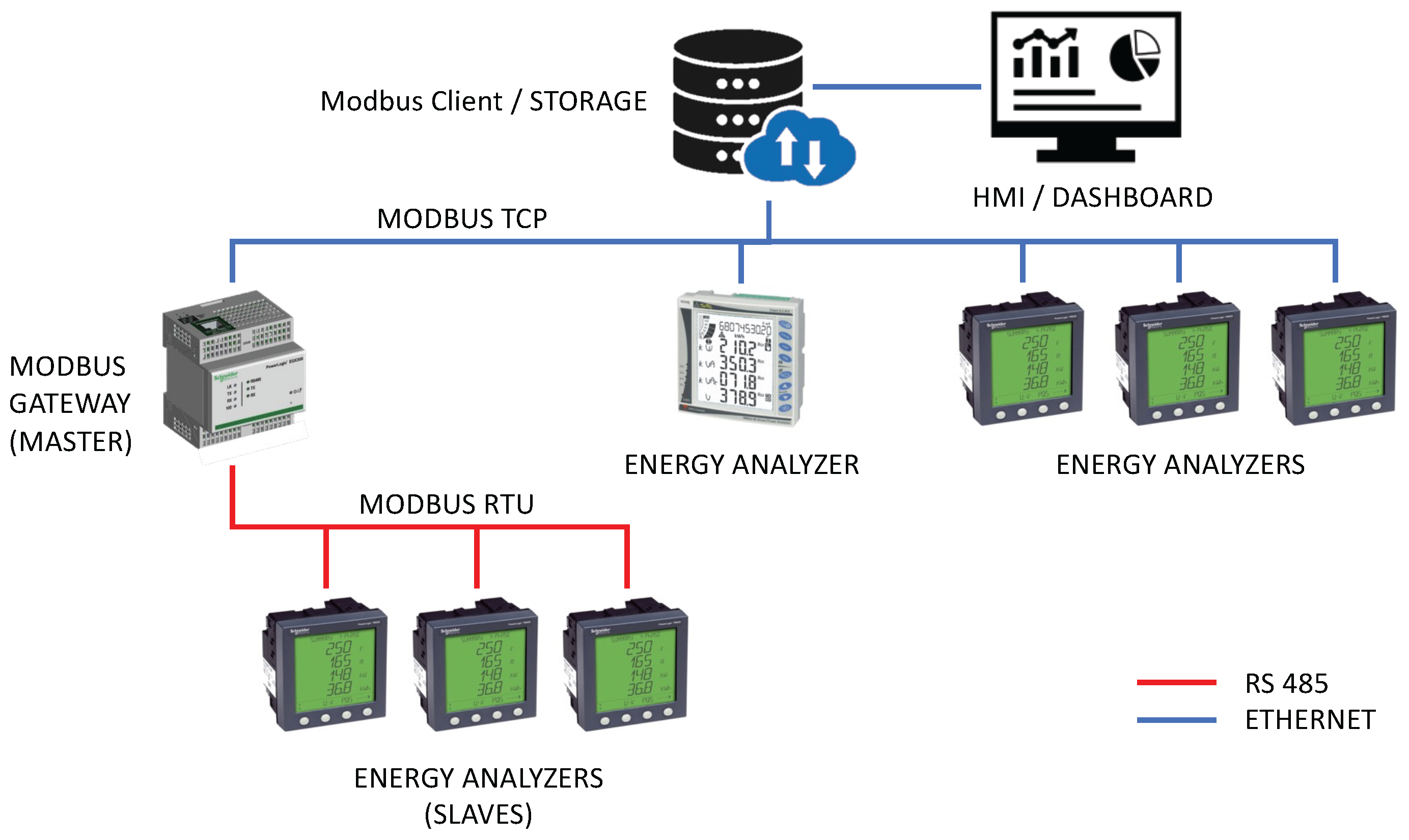

In ModBus, the master issues requests to slaves, which return responses according to the defined function codes. The query and response messages hold the same structure, containing the following elements: (i) Slave ID is a 1-byte address field. We can connect 256 devices to the ModBus network. (ii) Function code is a 1-byte address field. The function code in question tells the slave device what kind of action to execute. (iii) Data is a single-byte address field. The data field consists of 1 start bit, 8-bit data, and 1 or 2 stop bits. The data field contains data of field devices which are united into a network. In

Figure 4 a hybrid multi-vendor, multi-protocol energy meter architecture with specific reference to ModBus technology is represented. At the Ethernet level, the master is directly connected to the meters by ModBus TCP/IP solution, while bottom meter devices using ModBus RTU are served by the ModBus Gateway. Therefore, the ModBus TCP/IP-to-ModBus RTU converter is used as a Gateway.

4.2. Implementation Details

We implemented a Python module to collect data from the deployed meter devices. The data acquisition software was designed to be scalable and extensible by the definition of a dedicated class for each energy meter. As shown in

Figure 5, all classes inherit general methods and attributes from a generic class called

EnergyDevice. We implemented four different classes called

PM5320,

PM750,

PM3250, and

GavazziWM30. Those classes implement the same ModBus requests but differ in the register codes and the organization of data (e.g., bit ordering).

Table 4 reports the list of the energy meter features extracted and their relative descriptions. More details on class implementation can be found in [

30].

Monitoring progress toward SDG 7 requires a set of metrics that both measure energy consumption and production directly and evaluate the stability and efficiency of the electrical system. From the available system-meter data, we extract the metrics listed in

Table 4 which contribute to SDG 7 across two complementary categories: (i) direct correlation and (ii) indirect correlation through system health and anomaly detection. These are described as follows:

Direct-impact metrics include the various forms of Active, Reactive, and Apparent Energy measurements, which are fundamental to assessing energy sustainability. Active Energy Delivered and Received quantify the building energy consumption and potential on-site generation, supporting evaluations of energy neutrality and the contribution of renewable sources such as solar or wind.

Indirect-impact metrics do not directly measure consumed or produced energy but are essential to ensuring a reliable and efficient electrical infrastructure. Indicators such as phase currents, voltages, and total harmonic distortion (THD), as well as neutral, ground, and average currents, help identify anomalies including overloads, leakages, and load imbalances. Detecting these issues early helps prevent equipment failures and avoid unnecessary energy losses.

Although renewable energy sources can fluctuate in the order of seconds, measurements are usually stored as time-averaged values. Indeed, [

31] demonstrated that simulations using time steps longer than one minute lead to underestimation of both imported and exported energy. In practice, automatic meter reading infrastructures typically provide 15 min data for both demand and generation [

32]. As discussed later in this section, the developed system achieves an acquisition interval below one minute, independent of the number of meters integrated. In our design, the monitoring temporal resolution is a configurable parameter, allowing for adaptation to different edge data volumes. Concretely, the ModBus module polls all devices every 5 min, retrieving selected registers and encapsulating them in JSON format, suitable for storage in a database or transmission via messaging protocols such as MQTT or RabbitMQ for real-time dashboard visualization.

To ensure the replicability of the proposed solution and clarify the data collection logic executed at the edge, Algorithm 1 outlines the procedure for device polling and variable data aggregation. This logic manages the trade-off between granular monitoring and network overhead.

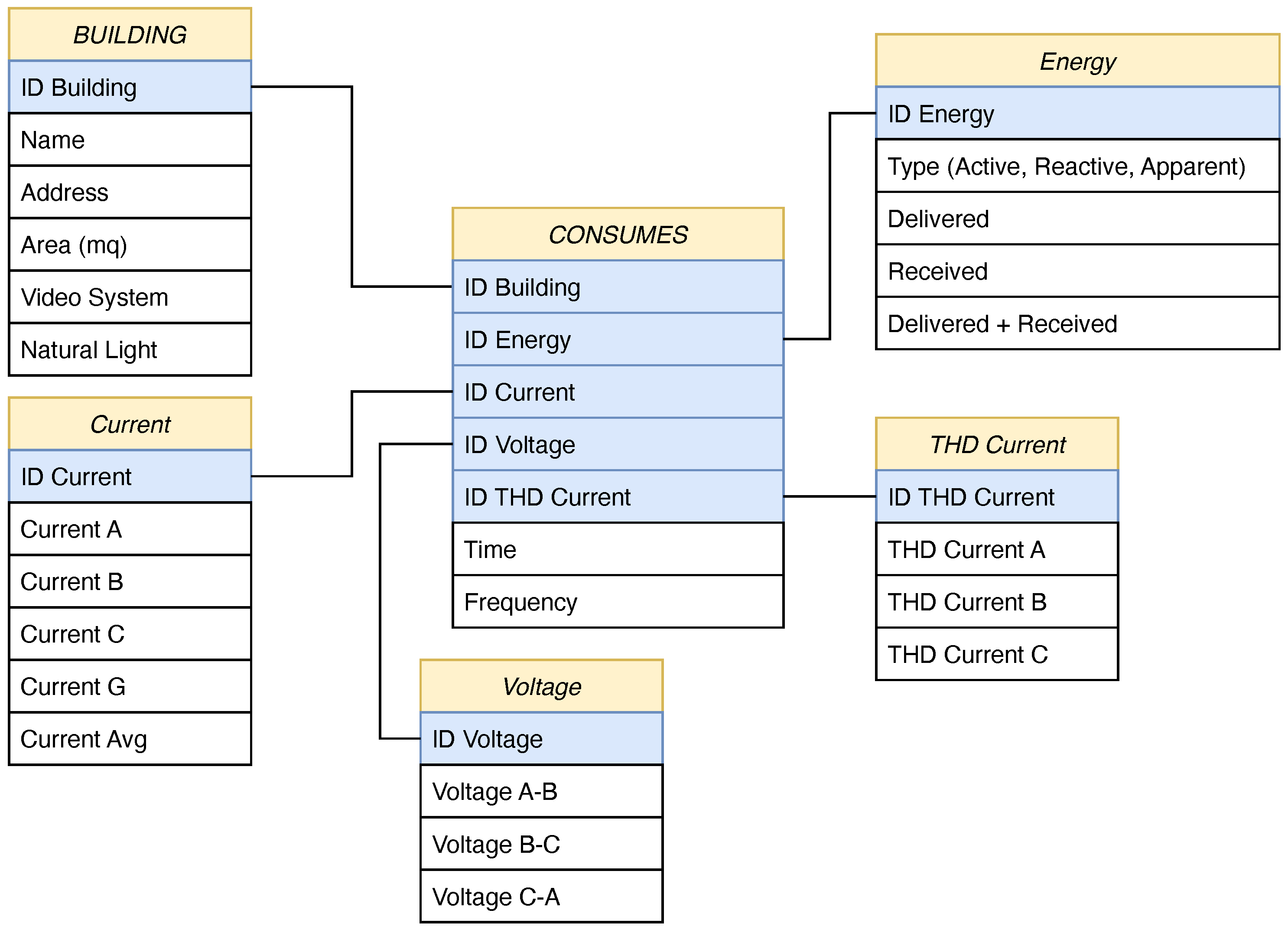

The raw measurements collected at the edge are then processed through an ETL workflow designed to address the heterogeneity and data quality issues arising from the integration of multiple meter types. As shown in

Figure 5, an object-oriented abstraction layer is employed, where each meter model extends a common EnergyDevice superclass. This approach enables a uniform interpretation of device registers, consistent unit normalization, and the structured formatting of measurements prior to entering the ETL pipeline. During acquisition, several data quality issues were observed, including missing or partial ModBus frames, transient communication errors, inconsistent timestamping, and spurious numerical values caused by electrical noise. The edge logic described in Algorithm 1 mitigates these problems through buffering and time-window aggregation (

ComputeAverage method), retry mechanisms based on predefined

modbus_timeout rules, and the discarding of invalid readings. This ensures robustness against sporadic acquisition failures and prevents corrupted data from propagating to higher layers of the system. To ensure temporal coherence across heterogeneous devices, the ETL layer standardizes timestamps and aggregates all measurements into a uniform 5 min resolution. This parameter is configurable and is motivated by both the acquisition capabilities of the system. Actual polling time consistently remains below one minute regardless of the number of monitored meters, in line with the existing literature showing diminishing benefits below sub-minute resolutions and a risk of underestimating imported and exported energy. At the same time, the chosen interval reduces the overhead on network and database resources while preserving meaningful variations in consumption and production signals. Following these steps, the ETL workflow validates, harmonizes, and integrates the processed data into the reconciled database, which then serves as the structured input for the star schema presented in

Figure 6.

| Algorithm 1 Edge device polling and data aggregation logic. |

- Require:

List of , , - Ensure:

Aggregated Energy Data sent to Cloud - 1:

- 2:

- 3:

while

do - 4:

- 5:

for all do - 6:

{Parallel execution or async calls} - 7:

- 8:

- 9:

end for - 10:

if then - 11:

- 12:

{via MQTT/Rest} - 13:

- 14:

- 15:

end if - 16:

- 17:

end while

|

The combination of the object-oriented design presented in

Figure 5 and the polling logic detailed in Algorithm 1 ensures the reproducibility of the proposed system. Specifically, the modular definition of the EnergyDevice class allows for the easy integration of new meter models by simply extending the base attributes and register maps, while the edge-level aggregation logic can be replicated using standard MQTT brokers and time-window processing.

4.3. Conceptual and Logical Design

To support the construction of the SDG 7 data warehouse, the system implements a multi-stage process that transforms heterogeneous raw measurements into a unified, validated, and analytics-ready repository. This process comprises four main phases, extraction, cleaning and harmonization, temporal alignment and aggregation, and integration into the reconciled database:

Extraction of heterogeneous device data.

The acquisition layer collects measurements from different meter models (e.g., Schneider PM750, PM3250, PM5320, and Gavazzi WM30), each with distinct register maps, data types, and sampling capabilities. An object-oriented abstraction layer (

Figure 5) unifies these differences: every meter type extends the common

EnergyDevice class, which encapsulates device-specific decoding routines and converts ModBus registers into meaningful physical quantities. This stage produces a first structured representation of the data, independent of the underlying hardware.

Data cleaning and harmonization.

Raw readings may suffer from incomplete ModBus frames, transient communication failures, and noise in electrical signals. The edge logic described in Algorithm 1 addresses these issues by discarding corrupted values, retrying failed data acquisitions according to predefined timeout rules, and buffering valid measurements. During this phase, all numerical values are normalized to standard units (e.g., kWh, V, A, Hz, and %THD) regardless of device encoding (INT16, UINT32, and FLOAT32), thus removing format heterogeneity and ensuring semantic consistency.

Temporal alignment and aggregation.

Since different devices may respond at slightly different times, timestamps must be aligned in a coherent temporal grid. The system aggregates buffered measurements through the ComputeAverage method, producing time-window summaries that are robust to sporadic missing readings. The final harmonized dataset adopts a uniform 5 min resolution, a configurable parameter justified by the system’s acquisition performance and supported by the existing literature. This step guarantees comparability across all meters and enables consistent downstream analytics.

Loading into the reconciled database.

The cleaned, normalized, and temporally aligned data are stored in the reconciled database, which acts as the authoritative operational data store. This repository maintains the finest aggregated granularity, preserves device-independent semantics, and ensures referential consistency. As such, it serves as the trusted single source from which the data warehouse is populated.

In the final stage, the reconciled data are transformed into the multidimensional structures of the SDG 7 data warehouse. Measurements flow into the fact table of the star schema (

Figure 6), while metadata such as time, device attributes, locations, and energy types populate the corresponding dimension tables. This separation between the reconciled database and the analytical warehouse enables strict data quality control at the operational layer and efficient OLAP-oriented querying at the analytical layer.

4.4. Scalability and Extensibility

To assess the scalability of the proposed system, we monitored the time required to read measurement data and logged the response times of each meter.

Figure 7 presents these results as a bar plot, where each bar represents the mean response time for a meter, and the variance is indicated by the error bar. As shown, the average extraction time is approximately 30 s. It is important to note that this interval includes the retrieval of multiple metrics from each device, as described in

Section 4.2. Although individual reads take roughly 30 s, the overall collection time does not increase with the number of devices, since measurements are acquired in parallel at the edge, and, when available, through ModBus Gateways. Consequently, the total acquisition time corresponds to the maximum read time among the devices, demonstrating that the system architecture ensures scalability.

4.5. Communication Protocols and Data Integrity

The developed system accommodates both ModBus RTU and ModBus TCP, facilitating versatile integration with diverse field devices. For ModBus TCP, the system inherently exploits TCP’s reliable transport features, such as automatic packet retransmission and in-order delivery, which mitigate packet loss and corruption at the transport layer. Nonetheless, each transmitted measurement is additionally tagged with a timestamp. This enables the receiving application to identify temporal discontinuities or missing samples in the measurement sequence, thus revealing data gaps that may arise from communication anomalies.

Although not part of the analytical scope of this study, the proposed system architecture can be extended to include additional edge-level processing for data quality monitoring. For instance, lightweight anomaly detection methods could operate to identify outliers in real time. A suitable example is the Hampel filter, a robust outlier detection technique that can be applied to data stream [

33]. The Hampel filter assesses values within a sliding window and flags anomalies by comparing each observation to the median and median absolute deviation of the local window.

4.6. Query Processing

The star schemes for SDG 7 monitoring are implemented by using the data warehousing software framework QlikView [

27]. QlikView is used as the front-end component for the visualization layer of the SDG 7 monitoring platform. Once the reconciled data are structured into the star schema shown in

Figure 6, the fact and dimension tables are imported into QlikView using its standard data loading interface. The framework automatically establishes associations between tables through their key attributes, enabling users to explore production and consumption trends through interactive dashboards. No custom scripting or advanced configuration is required in the current implementation; QlikView operates directly on the multidimensional structures generated by the data warehouse, providing graphical summaries that support SDG 7 indicators.

Table 5 summarizes four example queries for which we show the obtained results.

Figure 8 presents the outcomes for Query 1, demonstrating the comparative energy usage (in kWh) of each device of one specific building (ED18) over the past three years. This diagram visually represents each meter as a distinct box, with its size and color indicating its relative energy consumption among the examined devices of the building. This plot representation functions as a comprehensive query tool, efficiently identifying devices with major consumption and showcasing any observable trends that have emerged over recent years.

Figure 9 illustrates the results related to Query 2, presenting an analysis of the monthly energy consumption (kWh) across all campus buildings for the period spanning January 2024 to December 2024. In contrast to the previous query, this particular analysis emphasizes observations within a singular year. The figure provides an explicit comparison of energy usage among various buildings, highlighting detailed information pertaining to a specific month.

The results illustrated in

Figure 9 reveal clear energy consumption patterns, which are validated using real benchmarking data derived from a set of energy bills for a specific building. Owing to privacy constraints, access was granted only to a subset of bills from an earlier period than the one analyzed in this paper. Consequently, rather than referencing the raw data directly, we compare their trends with the energy consumption records of building ED14 from 2018 to 2022. The analysis confirms a recurring pattern: consumption peaks in January and July, corresponding to the coldest and hottest months in Palermo. August is excluded, as it is a non-working period due to public holidays in Italy.

To quantitatively assess the accuracy of the measures extracted by the system, we compared them against the ground truth and computed the Mean Absolute Percentage Error using six billing records for building ED14, obtaining a value of 8.3%.

Figure 10 highlights the results obtained for Query 3, showing the monthly energy consumption (kWh) for a specific building (e.g., building ED9) between January 2024 and December 2024. The figure clearly indicates a marked rise in energy consumption during the hottest and coldest months, mainly due to the use of air conditioning systems. There is a drop in consumption during the months when the building is closed or less frequented by students (e.g., during the Christmas holidays in December, the summer holidays in August, and university breaks, such as in June or March). To validate the consistency of the query results, we compare the university energy bills for building ED9 in August and October, which report equivalent values.

In order to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the specific contributions to the energy consumption for each building, every building is equipped with distinct subsystem energy meters. We consider this aspect in the final query. Indeed,

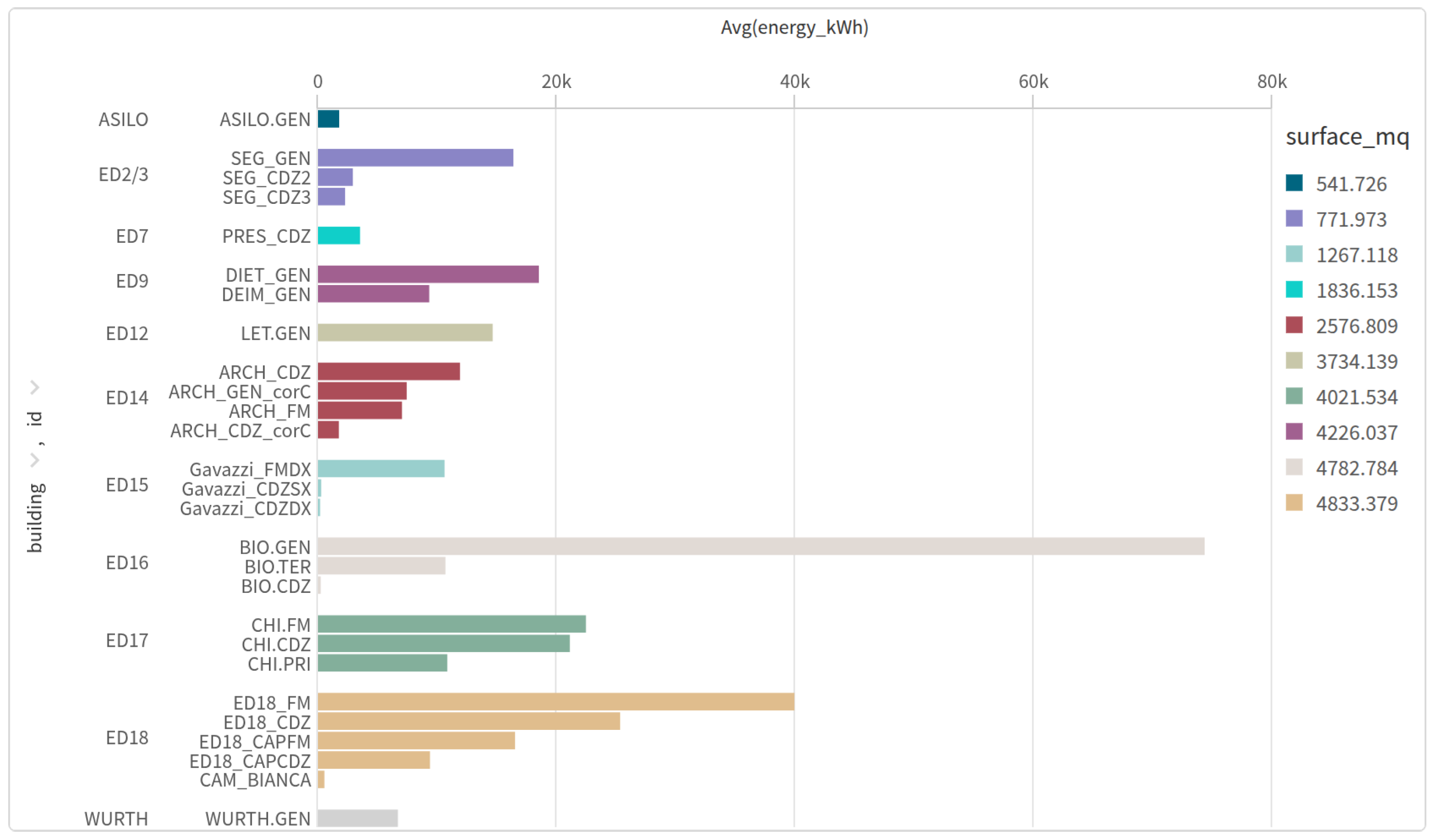

Figure 11 shows the outcomes of Query 4, which exclusively examines buildings with a floor area exceeding 500 square meters. This analysis encompasses a total of 11 buildings. The bar plot presented illustrates grouped bars for each building, with each bar representing a distinct subsystem. Typically, the lighting system (GEN) exhibits a higher energy consumption compared with other subsystems.

5. Discussion and Insights

Monitoring energy consumption is essential to achieving SDG 7, which aims to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. Because energy underpins basic services and has direct implications for sustainability, climate change, equity, and resilience, tracking how energy is produced and used is crucial to informed decision making. SDG 7 relies on measurable indicators, such as energy intensity (Indicator 7.3.1) and installed renewable energy capacity (Indicator 7.b.1), to evaluate progress in efficiency and clean energy deployment. In this context, infrastructure monitoring, which is the focus of this paper, is important to help identify inefficiencies, support targeted energy-saving actions, demonstrate contributions to global sustainability goals, and foster long-term behavioral change. Overall, systematic monitoring provides the evidence base needed to adjust policies, guide investments, measure progress, and ensure accountability across all levels of society, making it a strategic necessity for fulfilling SDG 7.

In order to reach the stated goal, we require robust and scalable methods for data-driven monitoring and analysis. Thanks to the edge–cloud approach, the proposed platform addresses this challenge, with a specific focus on energy consumption as a key metric for green technology initiatives. The main component of our platform is the strategic implementation of an edge–cloud architecture. This decentralized paradigm is crucial to creating an effective and efficient monitoring system in large-scale organizational contexts, such as a university campus. The distributed processing at the network edge is closer to the energy meters and reduces the computational and network load on the central cloud infrastructure. Instead of transmitting a constant, high-volume stream of raw data, edge devices can aggregate, filter, and normalize information before forwarding only relevant insights. This approach significantly reduces bandwidth consumption and minimizes the energy required for data transmission, making the monitoring system itself more sustainable. Consequently, the cloud is freed from low-level processing tasks and can dedicate its resources to more complex, value-added analyses, such as long-term trend forecasting and proactive anomaly detection.

Our focus on energy consumption directly targets SDG 7, which aims to ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. A distributed monitoring system, like the one we have designed, is instrumental in achieving this goal within an organizational framework. It moves beyond simple utility billing to provide granular, real-time insights into where, when, and how energy is being consumed. This detailed visibility empowers stakeholders to identify specific points of inefficiency, validate the impact of energy-saving interventions, and cultivate a culture of responsible energy use. The integration of various meter types demonstrates the platform’s capacity to handle heterogeneous data sources, which is a common real-world challenge. By leveraging edge computing, we not only monitor progress towards SDG 7 but also embody the principles of the Green IoT by designing an infrastructure that is inherently more resource-efficient.

Looking forward, the modular design of our platform provides a clear roadmap for expansion. While this paper focuses on energy (SDG 7), the foundational architecture can be readily adapted to monitor other critical sustainability metrics, such as water consumption (SDG 6), waste generation (SDGs 11 and 12), and air quality. The true potential of this platform lies in its evolution from a monitoring tool to a proactive management system. The curated data within the data warehouse serve as a rich foundation for applying advanced machine learning and data mining techniques. Future work will focus on developing predictive models to forecast energy demand, automate alert systems for consumption anomalies, and ultimately support dynamic, intelligent decision making for more sustainable and resource-efficient organizations.

6. Conclusions

We have presented the design of a data management software platform aimed at monitoring and quantifying progress toward the SDGs, a key task outlined in the United Nations Agenda 2030. The proposed platform is built on an edge–cloud architecture, where data are collected in distributed edge devices and aggregated in the cloud to enable centralized analysis and scalable monitoring.

As a case study, we focused on the initial core module of the platform to monitor energy consumption within a university campus. We demonstrated the implementation of a data acquisition system at the edge and showed how collected data are integrated and analyzed in the cloud. In particular, we implemented and executed four representative sustainability-related queries in the cloud environment, illustrating how the system works on real-time edge data. At this stage, the system is able to monitor energy consumption, without providing specific alerts in case of possible encountered anomalies.

In the future, we plan to extend the functionalities of the energy consumption monitoring platform with suitable outlier detection strategies, in order to identify anomalies and prevent the monitored buildings to be subjected to possible damages. Moreover, we plan to expand the platform by developing dedicated data marts for monitoring all 17 SDGs, which will require addressing complex challenges in heterogeneous data integration. Indeed, further data typologies will need to be analyzed, such as unstructured data (texts, pdf files, etc.). We are already working on the implementation of the platform services for managing collaboration among stakeholders (SDG 17) and those for supporting water metering (SDG 6). In addition, our goal is to incorporate advanced data mining techniques and analytical models to enable holistic assessment and support decision-making processes, including also statistical methods to assess data quality and validate trends. Finally, as part of future work, we plan to perform a comparative evaluation with other edge computing systems, assessing the resource requirements and their impact on the feasibility of constrained edge devices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.E.R.; Software, Y.G., D.G. and F.G.; Data curation, Y.G., D.G. and F.G.; Writing—original draft, Y.G., D.G., F.G. and S.E.R.; Writing—review & editing, Y.G., D.G. and F.G.; Visualization, Y.G.; Supervision, M.C., D.P. and S.E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Partial support to Y.G., D.G., and S.E.R. has been granted by the projects INdAM - GNCS CUP: E53C23001670001 and CUP: E53C24001950001. Partial support to Y.G., D.G., F.G., and S.E.R. has been granted by the project “Models and Algorithms relying on knowledge Graphs for sustainable Development goals monitoring and Accomplishment (MAGDA)” (CUP: B77G24000050001), under the “Future Artificial Intelligence (FAIR)” program funded by the European Union under the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) of NextGenerationEU. Partial support to D.G., F.G., and S.E.R. has been granted by the following project funded by the European Union under the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) of NextGenerationEU: SPRINT, a partnership on “Telecommunications of the Future” (PE00000001—program “RESTART”—CUP E83C22004640001).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Reviewers, for their suggestions which have contributed to improving the quality of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015, A/RES/70/71. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Biggeri, M.; Clark, D.A.; Ferrannini, A.; Mauro, V. Tracking the SDGs in an ‘integrated’ manner: A proposal for a new index to capture synergies and trade-offs between and within goals. World Dev. 2019, 122, 628–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, R.B.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Achieving sustainable development goals: Predicaments and strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chau, S.N.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Dietz, T.; Wang, J.; Winkler, J.A.; Fan, F.; Huang, B.; et al. Assessing progress towards sustainable development over space and time. Nature 2020, 577, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mooney, H.; Hull, V.; Davis, S.J.; Gaskell, J.; Hertel, T.; Lubchenco, J.; Seto, K.C.; Gleick, P.; Kremen, C.; et al. Systems integration for global sustainability. Science 2015, 347, 1258832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidigbi, M. Digital Technologies for Sustainable Development: Dual Challenge of Sustainability and Inclusivity Perspective. Law Digit. Technol. 2021, 1, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Song, Y. Role of Digital Technology in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: Focus on the Efforts of the International Community. J. Int. Dev. Coop. 2021, 16, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, D.; Jin, H. Service Management and Energy Scheduling Toward Low-Carbon Edge Computing. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2023, 8, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berawi, M.A. The Role of Industry 4.0 in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Technol. 2019, 10, 644–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khara, A.; Javid, I.; Khara, S.; Khara, B.; Prasad, R. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by Leveraging 6G Services. In Proceedings of the 2024 27th International Symposium on Wireless Personal Multimedia Communications (WPMC), Greater Noida, India, 17–20 November 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banda, L.; Mzyece, M.; Mekuria, F. 5G-IoT and Sustainability: Smart City Use Case. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 100th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Fall), Washington, DC, USA, 7–10 October 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G.; Vetters, N.; Maduta, C. Towards (net) zero emissions in the stationary energy sector: A city perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 97, 104750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Sivaparthipan, C.; Muthu, B. IoT based smart and intelligent smart city energy optimization. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 49, 101724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbas, D.; Gurbuz, T.; Alptekin, G.I. Smart Street Lighting Systems for Sustainable Smart Cities: A Conceptual Framework. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Sustainable Smart Lighting World Conference & Expo (LS24), Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 12–14 November 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simitha, K.M.; Subodh Raj, M.S. IoT and WSN Based Air Quality Monitoring and Energy Saving System in SmartCity Project. In Proceedings of the 2019 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Instrumentation and Control Technologies (ICICICT), Kannur, India, 5–6 July 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1431–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, M.N.; Abapour, M. IoT-based Office Buildings Energy Management with Distributed Edge Computing Capability. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Technology and Energy Management (ICTEM), Babol, Iran, 8–9 February 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajule, N.; Venkatesan, M.; Pawar, S.; Bhowmik, M.; Repe, M.; Jadhav, S. A Green IoT Framework for Sustainable Smart Campus Energy Monitoring and Management. In Proceedings of the 2025 7th International Conference on Inventive Material Science and Applications (ICIMA), Namakkal, India, 28–30 May 2025; pp. 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaerudin; Marini, A.; Saputro, R.H.; Marfu, A. Smart education for a sustainable future: Integrating IoT and big data in sustainability-based learning. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghoul, S.K.; Agha, K.R.; Zgalei, A.S.; Dekam, E.I. Energy saving measures of residential buildings in North Africa: Review and gap analysis. Int. J. Recent Dev. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A review on buildings energy consumption information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, L.; Yan, Y.; Guo, S.; Wen, F.; Qiu, X. Priority-Based Residential Energy Management with Collaborative Edge and Cloud Computing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 1848–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Yi, C.; Wang, R.; Chen, B. Proactive Application Deployment for MEC: An Adaptive Optimization Based on Imperfect Multi-Dimensional Prediction. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 16374–16390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, S.; Garlisi, D.; Carugno, C.; Tedesco, C.; Chatzigiannakis, I. Edge2LoRa: Enabling edge computing on long-range wide-area Internet of Things. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, W.; Ge, H. Design and Implementation of Modbus Protocol for Intelligent Building Security. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), Xi’an, China, 16–19 October 2019; pp. 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y. We do not have Systems for Analysing IoT Big-Data. In Proceedings of the CIDR, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 12–15 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, Y. A Survey on IoT Big Data Analytic Systems: Current and Future. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 1024–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyansky, O.; Gibson, T.; Leichtweis, C. QlikView Your Business: An Expert Guide to Business Discovery with QlikView and Qlik Sense; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Electric, S. Electric, PowerLogic™ PM5300 Series User Manual. Available online: https://www.se.com/it/it/download/document/EAV15107-EN/ (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Modbus Organization. Modbus Technical Resources. Available online: http://modbus.org (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Giuliano, F. Energy Edge Monitor: Skeleton Repository. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/fabriziogiuliano/energy_edge_monitor (accessed on 23 December 2025).

- Wright, A.; Firth, S. The nature of domestic electricity-loads and effects of time averaging on statistics and on-site generation calculations. Appl. Energy 2007, 84, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, V.; Knockaert, J.; Develder, C.; Desmet, J. Investigating the need for real time measurements in industrial wind power systems combined with battery storage. Appl. Energy 2019, 247, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlisi, D.; Milani, S.; Tedesco, C.; Chatzigiannakis, I. Achieving Processing Balance in LoRaWAN Using Multiple Edge Gateways. In Proceedings of the Algorithmic Aspects of Cloud Computing; Doka, K., Tsiropoulou, E.E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 46–61. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

General software platform for the monitoring of the SDGs.

Figure 1.

General software platform for the monitoring of the SDGs.

Figure 2.

Sketch of data marts to support decisions and the monitoring of each SDG.

Figure 2.

Sketch of data marts to support decisions and the monitoring of each SDG.

Figure 3.

University of Palermo campus map with highlighted monitored buildings.

Figure 3.

University of Palermo campus map with highlighted monitored buildings.

Figure 4.

Hybrid ModBus architecture including Ethernet and RTU connection by ModBus Gateway.

Figure 4.

Hybrid ModBus architecture including Ethernet and RTU connection by ModBus Gateway.

Figure 5.

Class list of the implemented solution.

Figure 5.

Class list of the implemented solution.

Figure 6.

Overview of the designed data warehouse architecture. Reconciled measurement data are ingested by using the star schema present into the outlined table.

Figure 6.

Overview of the designed data warehouse architecture. Reconciled measurement data are ingested by using the star schema present into the outlined table.

Figure 7.

Average data acquisition time and variance for each monitored device.

Figure 7.

Average data acquisition time and variance for each monitored device.

Figure 8.

Results for Query 1. Treemap visualization of annual electricity consumption (kWh) of ED18 sub-components across 2023–2025. Each rectangle represents a sub-component (ED18_FM, ED18_CDZ, ED18_CAPFM, and ED18_CAPCDZ), with its area being proportional to the corresponding yearly consumption. Colors indicate consumption ranges according to the legend, spanning from lower (blue) to higher (purple) values. Year labels are placed at the center of each group to distinguish the annual aggregates. This self-contained representation enables direct comparison of consumption levels across sub-components and years.

Figure 8.

Results for Query 1. Treemap visualization of annual electricity consumption (kWh) of ED18 sub-components across 2023–2025. Each rectangle represents a sub-component (ED18_FM, ED18_CDZ, ED18_CAPFM, and ED18_CAPCDZ), with its area being proportional to the corresponding yearly consumption. Colors indicate consumption ranges according to the legend, spanning from lower (blue) to higher (purple) values. Year labels are placed at the center of each group to distinguish the annual aggregates. This self-contained representation enables direct comparison of consumption levels across sub-components and years.

Figure 9.

Results for Query 2. Monthly electricity consumption (kWh) for all monitored buildings from July to June. The stacked area chart displays the contribution of each building (ASILO, ED2/3, ED7, ED9, ED12, ED14, ED15, ED16, ED18, and WURTH) to the total monthly consumption. The height of each colored band represents the building’s individual energy use for that month, enabling a direct comparison of consumption patterns across buildings and seasons. This visualization provides an integrated view of temporal trends, highlighting both overall load variability and building-specific fluctuations throughout the year.

Figure 9.

Results for Query 2. Monthly electricity consumption (kWh) for all monitored buildings from July to June. The stacked area chart displays the contribution of each building (ASILO, ED2/3, ED7, ED9, ED12, ED14, ED15, ED16, ED18, and WURTH) to the total monthly consumption. The height of each colored band represents the building’s individual energy use for that month, enabling a direct comparison of consumption patterns across buildings and seasons. This visualization provides an integrated view of temporal trends, highlighting both overall load variability and building-specific fluctuations throughout the year.

Figure 10.

Results for Query 3. Monthly energy consumption (kWh) for building ED9 over a one-year period. Each point on the polyline corresponds to the total energy use recorded for a specific month, with the horizontal axis indicating energy consumption values and the vertical axis listing months in chronological order. This visualization highlights the temporal variability in ED9’s energy demand, allowing for direct identification of seasonal peaks, troughs, and month-to-month changes. The applied filter (building: ED9) isolates the building’s profile to facilitate focused analysis without contributions from other facilities.

Figure 10.

Results for Query 3. Monthly energy consumption (kWh) for building ED9 over a one-year period. Each point on the polyline corresponds to the total energy use recorded for a specific month, with the horizontal axis indicating energy consumption values and the vertical axis listing months in chronological order. This visualization highlights the temporal variability in ED9’s energy demand, allowing for direct identification of seasonal peaks, troughs, and month-to-month changes. The applied filter (building: ED9) isolates the building’s profile to facilitate focused analysis without contributions from other facilities.

Figure 11.

Results for Query 4. Average energy consumption (kWh) of all monitored sub-components across buildings, displayed as horizontal bars. Each bar represents the mean energy use of a specific device or subsystem within a given building, allowing for direct comparison both within and across facilities. Bars are color-coded according to the floor area (mq) of the corresponding building, as indicated in the legend, providing contextual information on the scale of each facility. This visualization enables readers to assess how consumption relates to building size and to identify high-consumption sub-components that may warrant further investigation.

Figure 11.

Results for Query 4. Average energy consumption (kWh) of all monitored sub-components across buildings, displayed as horizontal bars. Each bar represents the mean energy use of a specific device or subsystem within a given building, allowing for direct comparison both within and across facilities. Bars are color-coded according to the floor area (mq) of the corresponding building, as indicated in the legend, providing contextual information on the scale of each facility. This visualization enables readers to assess how consumption relates to building size and to identify high-consumption sub-components that may warrant further investigation.

Table 1.

The list of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

1].

Table 1.

The list of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [

1].

| SDG Number | SDG Title | SDG Description |

|---|

| SDG 1 | No Poverty | End poverty in all its forms everywhere |

| SDG 2 | Zero Hunger | End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture |

| SDG 3 | Good Health and Well-Being | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages |

| SDG 4 | Quality Education | Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all |

| SDG 5 | Gender Equality | Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls |

| SDG 6 | Clean Water and Sanitation | Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all |

| SDG 7 | Affordable and Clean Energy | Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all |

| SDG 8 | Decent Work and Economic Growth | Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all |

| SDG 9 | Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation |

| SDG 10 | Reduced inequalities | Reduce inequality within and among countries |

| SDG 11 | Sustainable Cities and Communities | Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable |

| SDG 12 | Responsible Consumption and Production | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns |

| SDG 13 | Climate Action | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts |

| SDG 14 | Life Below Water | Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development |

| SDG 15 | Life on Land | Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems; sustainably manage forests; combat desertification; halt and reverse land degradation; and halt biodiversity loss |

| SDG 16 | Peace, Justice, and Strong Institution | Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels |

| SDG 17 | Partnership for the Goals | Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development |

Table 2.

SDG 7—Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all [

1].

Table 2.

SDG 7—Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all [

1].

| Targets | Indicators |

|---|

| 7.1 By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable, and modern energy services | 7.1.1 Proportion of population with access to electricity 7.1.2 Proportion of population with primary reliance on clean fuels and technology |

| 7.2 By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix | 7.2.1 Renewable energy share in total final energy consumption |

| 7.3 By 2030, double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency | 7.3.1 Energy intensity measured in terms of primary energy and GDP |

| 7.A By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology, including renewable energy, energy efficiency, and advanced and cleaner fossil-fuel technology, and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology | 7.A.1 International financial flows to developing countries in support of clean energy research and development and renewable energy production, including in hybrid systems |

| 7.B By 2030, expand infrastructure and upgrade technology for supplying modern and sustainable energy services for all in developing countries, in particular the least developed countries, small-island developing states, and land-locked developing countries, in accordance with their respective programs of support | 7.B.1 Installed renewable energy-generating capacity in developing and developed countries (in watts per capita) |

Table 3.

Comparative evaluation of the proposed distributed approach against traditional IoT systems and cloud infrastructures.

Table 3.

Comparative evaluation of the proposed distributed approach against traditional IoT systems and cloud infrastructures.

| Metric | Traditional IoT Systems | Cloud Infrastructures | Distributed (Proposed Solution) |

|---|

| Edge Processing Capability | None. Fully centralized processing. | Limited. Processing performed in cloud clusters. | High. Supports in-network and edge-level computation. |

| Latency | High. Data forwarded to a central server. | Moderate. Depends on network and cluster configuration. | Low. Local processing reduces end-to-end delay. |

| Bandwidth Usage | High. Raw data transmitted upstream to the central server. | High. Continuous data transfer to cloud. | Optimized. Edge filtering reduces upstream traffic. |

| Multi-Protocol Support | None. Rigid and single-protocol architecture. | Moderate. Integration via cloud services. | High. Native support for multiple protocols at the edge. |

Table 4.

Energy meter selected metrics.

Table 4.

Energy meter selected metrics.

| Register Name | Description | Unit | Size

(INT16) |

|---|

Active Energy

Delivered (Into Load) | Energy supplied to the load. | kWh | 2 |

Active Energy

Received (Out of Load) | Energy drawn from the load. | kWh | 2 |

Active Energy

Delivered + Received | Active Energy Delivered + Received. | kWh | 2 |

Active Energy

Delivered − Received | Total active energy exchanged. | kWh | 2 |

| Reactive Energy Delivered | Reactive Energy Delivered: Reactive

energy supplied to the load. | kVARh | 2 |

Reactive Energy

Received | Reactive Energy Received. | kVARh | 2 |

Reactive Energy

Delivered + Received | Reactive energy drawn from the load. | kVARh | 2 |

Reactive Energy

Delivered − Received | Net reactive energy transfer. | kVARh | 2 |

Apparent Energy

Delivered | Apparent energy supplied to the load. | kVAh | 2 |

| Apparent Energy Received | Apparent energy drawn from the load. | kVAh | 2 |

Apparent Energy

Delivered + Received | Total apparent energy exchanged. | kVAh | 2 |

Apparent Energy

Delivered − Received | Net apparent energy transfer. | kVAh | 2 |

| Nominal Frequency | frequency measured by device | Hz | 2 |

| Current A | Electric current flowing

through phase A. | A | 2 |

| Current B | Electric current flowing

through phase B. | A | 2 |

| Current C | Electric current flowing

through phase C. | A | 2 |

| Current N | Electric current flowing

through phase A. | A | 2 |

| Current G | Electric current flowing

through the ground wire. | A | 2 |

| Current Avg | Average electric current across all phases. | A | 2 |

| Voltage A-B | Voltage difference between

phase A and phase B. | V | 2 |

| Voltage B-C | Voltage difference between

phase B and phase C. | V | 2 |

| Voltage C-A | Voltage difference between

phase C and phase A. | V | 2 |

| THD Current A | Total harmonic distortion of

the electric current in phase A. | % | 2 |

| THD Current B | Total harmonic distortion of

the electric current in phase B. | % | 2 |

| THD Current C | Total harmonic distortion of

the electric current in phase C. | % | 2 |

Table 5.

Examples of provided queries.

Table 5.

Examples of provided queries.

| No. | Query |

|---|

| 1 | Show the energy consumption (kWh) of each device of a building (ED18) grouped for year in the last 3 years (2023, 2024, and 2025). |

| 2 | Show the energy consumption (kWh) of various buildings in the period between January 2024 and December 2024. |

| 3 | Show the energy consumption (kWh) of one specific building (ED9) for each month in the period between January 2024 and December 2024. |

| 4 | On average, in buildings with a surface area larger than 500 mq, which type of device is used the most frequently in the month of March? |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |