Abstract

The emergence of the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) has revolutionized intelligent transportation and communication systems. However, IoV presents many complex and ever-changing security challenges and thus requires robust cybersecurity protocols. This paper comprehensively describes and evaluates ensemble learning approaches for multi-class intrusion detection systems in the IoV environment. The study evaluates several approaches, such as stacking, voting, boosting, and bagging. A comprehensive review of the literature spanning 2020 to 2025 reveals important trends and topics that require further investigation and the relative merits of different ensemble approaches. The NSL-KDD, CICIDS2017, and UNSW-NB15 datasets are widely used to evaluate the performance of Ensemble Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems (ELIDS). ELIDS evaluation is usually carried out using some popular performance metrics, including Precision, Accuracy, Recall, F1-score, and Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC), which were used to evaluate and measure the effectiveness of different ensemble learning methods. Given the increasing complexity and frequency of cyber threats in IoV environments, ensemble learning methods such as bagging, boosting, and stacking enhance adaptability and robustness. These methods aggregate multiple learners to improve detection rates, reduce false positives, and ensure more resilient intrusion detection models that can evolve alongside emerging attack patterns.

1. Introduction

Recent research has focused on intelligent transportation systems (ITSs), which have the potential to provide automated and smart transportation services. ITSs use wireless devices, sensing technologies, and advanced Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to address transportation issues such as safety, travel time, and pollution [1,2]. ITSs apply to various modes of transportation, including planes, ships, trains, trucks, buses, and automobiles. ITS deployments require dependable communication systems, like cellular networks [1,2]. There are three types of vehicular communication: vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), and vehicle-to-everything (V2E). (i) V2V is a sort of two-way communication in which vehicles exchange data, such as velocity, current location, and destination, with other vehicles. V2V transmissions can also incorporate information about nearby moving cars, enabling the driver to quickly identify vehicles in their blind spot. (ii) V2I is a technology that allows automobiles to communicate with other infrastructures. V2I is a sort of two-way communication that allows vehicles to connect and share data with external entities, including traffic lights, parking spots, bicycles, and speed limits. V2I additionally incorporates radio communications that report on the surrounding environment within a few kilometers of a vehicle’s position [3]. (iii) V2E enables rapid communication for road safety applications such as forward collision alerts, lane change warnings, blind spot warnings, and emergency electric brake light warnings. V2E connects vehicles to external services, such as satellite-based destinations. This service can be one-way, like the Global Positioning System (GPS), or two-way, as requested.

Shortly, there will probably be more cars on the road, which will cause a boom in vehicle communications and associated sensors. In the automotive cyberspace, the current lack of firewalls and gateways to withstand various forms of intrusion will likely result in the emergence of new security vulnerabilities. Cyberattacks, such as the takeover of a vehicle or the dissemination of misleading information to influence the navigation algorithm’s decision, can have serious negative physical effects on individuals. Among other techniques, attackers can replace the vehicle’s current video with a fake stream for image processing, thereby gaining control over most or all of the vehicle’s characteristics [4]. GPS signal attacks fall into two categories: spoofing, false identification, and jamming, intentional interference [5]. To lower the signal-to-noise ratio of GPS broadcasts, jamming attacks usually involve the direct creation of radio waves. Spoofing threats include utilizing a bogus GPS device, posing as an image sensor to steal data, and using an infected GPS to disseminate malware or circumvent access control systems by gathering security data. Both attacks change and deliver bogus GPS signals to puzzled GPS receivers within cars.

Attackers may synchronize (Syn) the signals received from the satellite, weakening them even further. Then they may increase the frequency of the phishing signal, causing the car’s GPS to detect false signals and drive it in the wrong direction. Spoofing attacks, which deceive the system into believing there is a barrier nearby that the car must avoid, can also impair Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR). The vehicle’s LiDAR system gets millisecond-level signals to carry out the attack. An attacker can disable the device’s ability to detect obstructions by altering the LiDAR signal or structure. Attacks against inter-vehicle communications include denial-of-service (DoS), distributed reflection DoS (DrDoS), and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS). To disrupt the normal operation of automotive systems, such as internal or external communication and navigation, all these attacks rely on infecting the server and flooding it with internet traffic or sending malicious requests to various components and communication networks. A DoS attack is often carried out by a single or small number of attackers to overwhelm the vehicle’s systems and drastically slow it down. These attacks highlight the necessity for additional approaches in resilient sensor systems to ensure accurate sensor data quality [6]. To maintain the security and safety of connected vehicles in their surroundings, it is critical to develop an IDS capable of recognizing these types of attacks. This system can accomplish this by detecting unauthorized access, particularly during data transmission, as well as unauthorized agents using injection attacks to remotely control a vehicle or gain access to the massive amounts of sensitive and personal data generated by the IoVs [7].

IDSs have made some major progress in maintaining security and safety in IoV [5]. Different machine learning (ML) techniques are used nowadays to find unusual behavior in network data. Among these techniques, ensemble learning has become somewhat popular since it can efficiently combine several classifiers to improve prediction durability and accuracy. In several uses, including network intrusion detection, ensemble learning techniques have shown exceptional effectiveness [8]. This is so because they are skilled in handling the complexity and volatility that cybersecurity data naturally carries.

Using ensemble learning for multi-class intrusion detection in IoV brings both special opportunities and challenges. In the framework of IoV, multi-class classification is essential since it distinguishes between several kinds of dangers and benign behavior. Advanced algorithms must be used if one wants great accuracy and low false positive rates [9]. By combining the benefits of numerous models, improving detection capabilities, and adjusting to changing threats, ensemble approaches provide the means.

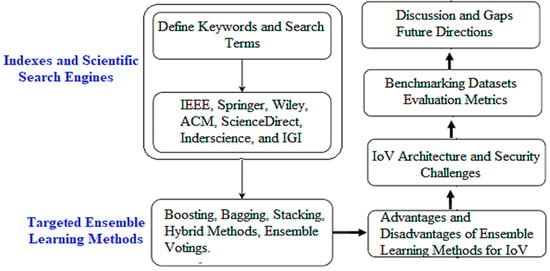

In this work, we used a comprehensive approach to collect and evaluate relevant data, ensuring a thorough understanding of the status of ensemble learning-based multi-class intrusion detection for IoV. Initially, pertinent keywords have been identified and searched to guarantee comprehensive coverage of ensemble learning techniques for IoV IDS. The search incorporated “Ensemble Learning,” “Intrusion Detection,” “Multi-Class Classification,” “Internet of Vehicles,” “VANETs,” and “Machine Learning.” To enhance search results and exclude irrelevant studies, Boolean operators such as “AND”, “OR”, and “NOT” were employed. The research included the following terms: “Ensemble Learning AND Intrusion Detection AND Internet of Vehicles,” “Multi-class classification AND Intrusion Detection AND VANETs,” “Machine Learning AND Intrusion Detection AND Vehicular Networks,” “Intrusion Detection Systems AND Ensemble Methods AND IoV”, as well as “Security AND Internet of Vehicles AND Machine Learning”.

The current study focused on major credible academic databases where the research was gathered, including IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, Google Scholar, ACM Digital Library, and Wiley Online Library. The vast compilation of conference papers and magazine articles on vehicle networks and security available in IEEE Xplore proved highly valuable. Google Scholar was utilized as an additional resource to ensure that no pertinent work was disregarded. The primary search yielded 87 articles from IEEE Xplore, 102 from SpringerLink, 134 from Scopus, and 42 from Wiley. Upon closer examination, 31 of the IEEE papers, 27 from Springer, 46 from Scopus, and 9 from Wiley were identified as uniquely relevant to the scope of this study. Notably, the Wiley Online Library, despite contributing a smaller number of papers overall, provided several distinctive studies not indexed in the other databases. This cross-platform inclusion helped ensure a diverse representation of current research trends. Moreover, to ensure the relevance and timeliness of the data, only conference papers and peer-reviewed articles published between 2020 and 2025 were considered. Figure 1 presents the survey methodology and the overall framework diagram. A list of all acronyms in this paper can be found in Abbreviations (i.e., at the end of the paper).

Figure 1.

Survey Methodology Flow Diagram.

1.1. Contributions

- Providing a comprehensive evaluation of ensemble learning methods (bagging, boosting, stacking, voting, hybrid) for multi-class intrusion detection in IoV.

- Proposing a taxonomy that analyzes and compares ensemble-based IDSs and datasets for IoV security context.

- Identifying recent research trends and gaps, recommending future directions for adaptive, scalable, and real-time IDS solutions in IoV.

1.2. Paper Organization

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces IoV architectures and security challenges, as well as an overview and analysis of the existing ensemble learning approaches. Section 3 discusses the related works, highlighting how our survey differs from other surveys in the literature with regard to ensemble learning methods, IoV, and Intrusion Detection Systems (IDSs). Section 4 analyzes research trends and gaps related to ensemble learning based IDSs for IoV. The section introduces a new taxonomy of the works studied. A discussion is performed in Section 5, and conclusions as future research directions are highlighted in Section 6.

2. Background

Today’s smart cars are basically social butterflies on wheels. They are constantly chatting with other cars, traffic lights, and pretty much anything that will listen. Welcome to the “Internet of Vehicles,” where your morning commute has turned into one giant group chat. The more our cars gossip with the world around them, the bigger the target they become for hackers. We would think about it if someone could hack our laptop to steal our photos, and what they could do with access to our car’s brain while we are cruising down the highway at 70 mph. Almehdhar et al. [10] dove deep into how we can use artificial intelligence to protect the secret conversations happening inside our cars. The authors hit a frustrating wall: we don’t have enough real-world data to build our IoV’s security. We cannot collect the data we need without good security, but we cannot build good security without the data. The authors also pointed out the need for some standardized datasets that every security developer can use. Meanwhile, Billah et al. [11] tackled another nightmare scenario: what happens when your car needs to spot a cyber threat in real-time while you’re actually driving? Cars do not have the computing power of a gaming laptop, so traditional cybersecurity approaches are about as useful as a chocolate teapot. The car’s security system needs to adapt faster than radio stations can change.

Almehdhar et al. [10] and Billah et al. [11] are tackling real problems and ensuring the need for a firm IoV security system that can detect and prevent critical breaches of vehicles in a real-time manner.

2.1. IoV Security Challenges

The IoV architecture is a complex framework designed to facilitate seamless communication and interaction among vehicles, infrastructure, and various other entities. It comprises several layers, including perception, network, and application layers, each serving distinct functions to ensure efficient data collection, transmission, and processing. The perception layer is responsible for gathering data from sensors and devices, while the network layer handles data communication through technologies like 5G and edge computing. The application layer processes this data to provide services such as traffic management, navigation, and infotainment [12].

Although IoV has great potential, its design leaves a lot of security flaws. The great interconnectedness and data flow across many companies have, as a result, crucial effects, including their vulnerability to cyberattacks. These attacks can show up as malware infections and data breaches, as well as more sophisticated ones, including DoS and man-in-the-middle attacks. Guaranteeing the availability, confidentiality, and integrity of data will help to maintain the dependability and credibility of IoV systems.

Managing the large volumes of data generated by the IoV in a safe way presents still another challenge. User identities and automobile locations are very important, so it is necessary to protect this data from unauthorized access and keep users’ anonymity. Furthermore, IoV networks’ dynamic and distributed character makes it more difficult to create robust security policies and quickly identify and deal with security concerns [13].

Furthermore, adding to interoperability and compatibility difficulties are the great variety of IoV components, which include several automotive models, communication protocols, and sensor types. These issues might create security flaws that hackers could find useful. Establishing consistent security measures and guaranteeing broad adoption can help one to properly handle these challenges [14]. Table 1 summarizes those challenges.

Table 1.

IoV Architecture Challenges.

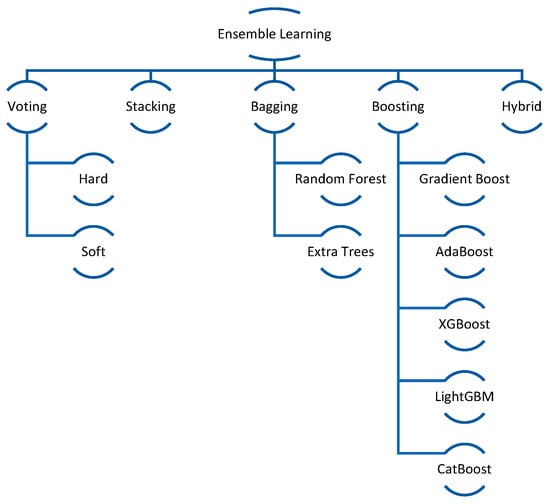

2.2. Ensemble Learning Approaches Overview

Dietterich [15] defined ensemble learning as an ML method whereby several models are combined to improve predicted accuracy. The ensemble learning working principle is to collect predictions through several models, which contribute to improving accuracy, especially in difficult tasks. Compared to single models, ensemble methods that combine the outputs of numerous base learners have the potential to attain more accuracy and robustness. As shown in Table 2, we classify ensemble learning into five categories: bagging, boosting, stacking, voting, and Hybrid. Indeed, sometimes combinations occur, resulting in hybrid ensemble approaches.

2.2.1. Boosting

It is a sequential ML method in which the next model fixes the errors created by the one before it. Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Gradient Boosting (GB), Ada Boosting, LightGBM (LGBM), and Cat Boosting have shown improved performance in recent intrusion detection studies based on empirical evaluations reported in the literature [16,17]. These methods aim at classifying difficult situations [16,18]. Boosting in general may reduce bias, but overfitting could appear due to noisy data [18].

XGBoost

XGBoost improves ML model performance and computing speed by building decision trees (DT) in parallel. XGBoost is an effective implementation of a GBML algorithm where stochastic gradient or tree boosting is used to develop a powerful ML technique that performs well in a wide range of complex situations [19].

Gradient Boosting (GB)

GB evaluates the significance of each attribute after creating the boosted tree, employing a robust metric referred to as feature importance. This scoring approach assesses the significance of each feature in developing DTs for essential decision-making. Feature importance quantifies the significance of each attribute [20]. The relevance is determined by explicitly comparing and evaluating each attribute in the dataset against the others. The relevance of an individual DT is determined by the quantity of each attribute split point, weighted by the total number of observations from that node. This division is employed to improve the algorithm’s efficacy and efficiency.

AdaBoost

AdaBoost is an iterative supervised learning algorithm that combines multiple predictions of weak classifiers [21]. The combination of updates, datasets, and voting is done using a weighted majority. To ensure this is successful, events that are difficult to classify are given priority above those that have already been adequately described.

LightGBM (LGBM)

The gradient hoist supports the LightGBM classification algorithm, known for its minimal processing load. A significant proportion of algorithms within the tree-based boosting family, including xgboost, utilize a presorting step for feature selection and splitting. Despite its significant effort and memory overhead, this presorting method can accurately identify the dividing point [22].

Cat Boosting

CatBoost outperforms in handling categorical variables within heterogeneous datasets compared to other gradient boosting DT implementations, as it utilizes ordered target statistics and ordered boosting. It utilizes symmetric trees to achieve efficient prediction times [17]. In the CatBoost method, each subsequent tree is generated with a reduced loss compared to its previous one. It allows the definition of custom functions, utilizes categorical features directly and efficiently, and reduces the necessity for extensive hyperparameter tuning. A significant discovery from their multidisciplinary research, as stated in a recent paper, is that it is sensitive to hyperparameters, making their adjustment essential. To enhance model performance, researchers may modify the maximum depth of individual DTs, the maximum number of combinations of categorical features, and the maximum number of iterations in CatBoost. The researcher’s selections of these hyperparameters may explain the variances in CatBoost’s performance.

2.2.2. Bagging Classifier

Sometimes referred to as Bootstrap Aggregating, it is the technique of training several base models using different subsets of training data. These models then generate aggregated model forecasts by means of voting or averaging, combining their projections. A popular bagging method is the Random Forests (RF), which are widely used in intrusion detection since they minimize overfitting and can manage huge collections of features. Meanwhile, class bias may exist [23].

Random Forest (RF)

RF is another version of bagging [24]. It builds the tree on a random selection mechanism. The concept of randomness is divided into two models: (1) random training instances are selected in tree construction, and (2) nodes are divided based on the selection of a random subset of features. A (no-pruning) technique in which trees are fully modeled can reduce bias and variance. The accuracy is well improved, and overfitting is combated by merging multiple trees.

Decision Tree (DT)

DT is a tree-like construction approach that includes branches and leaves. The branch displays the findings, and the interior node displays the classification criterion. The class designation corresponds to the leaves. During the training phase, the relevant qualities for primary nodes and branches are determined using the collected data. The information-gain score with the highest value is used to create the decision node. The cycle can be completed by creating a new subtree below the decision node. If all the items in the selected subgroups have the same value, the method will be completed, and the output value determined. When there is only one node left in the subgroup and no identifiable trait has been discovered, the cycle will stop [25].

2.2.3. Stacking

Stacking is the abbreviation for stacked generalization [26]. The method is about combining several ML models. It is a technique of teaching a meta-learner to maximize the output by aggregating predictions from several base models [27]. For difficult applications like multi-class intrusion detection on the IoV [28], this method, which combines the benefits of several algorithms, is ideally fit, even though stacking may suffer from the risk of overfitting due to the complexity of implementation [27,28]. For example, Singh et al. [26] proposed SE-LIDS, a stacking-based network-based IDS for IoV, where they have used LightGBM, XGBoost, and CatBoost in the stacking architecture and XGBoost as the meta-learner model.

2.2.4. Hybrid Methods

Similarly to stacking, hybrid methods combine different ensemble techniques to exploit their advantages. These methods often show superior performance but can be complex to implement and tune [29]. The difference between the two approaches lies in the fact that stacking focuses on combining predictions from multiple models using a meta-model, while a hybrid ensemble leverages different types of models or techniques together for enhanced performance.

2.2.5. Ensemble Voting Method

The voting ensemble technique in machine learning aggregates predictions from many models to enhance accuracy and durability. To arrive at a final decision, it amalgamates the results of multiple fundamental learners, or models. There are two primary styles of voting: hard voting and soft voting.

Hard Voting

Each model casts a vote for a specific class label, and the class with the most votes is chosen as the final prediction. This technique relies on the dominant class label found in each individual forecast [30].

Soft Voting

Each model generates a probabilistic estimation for every class. The final forecast is determined by selecting the class with the highest average likelihood after probability aggregation. This technique accounts for the level of certainty that models possess in their predictions [31]. One of the key advantages of the voting technique is its capacity to enhance accuracy by leveraging the strengths of multiple models, often outperforming individual learners [32]. Furthermore, ensemble methods provide robustness by mitigating the influence of individual model weaknesses, thereby producing more reliable and trustworthy forecasts [33]. Simplicity is another notable benefit, as these methods are generally easy to implement across diverse models without significant complexity [34].

Figure 2 is a pictorial view of the ensemble learning methods, while Table 2 summarizes the five ensemble learning methods with an example of each one, along with their strengths and weaknesses.

Figure 2.

Ensemble Learning Methods.

Table 2.

Ensemble learning methods’ strengths and weaknesses.

Table 2.

Ensemble learning methods’ strengths and weaknesses.

| Ensemble Learning Technique | Examples | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bagging | Random Forest | Reduces variance, robust against overfitting [23] | May not reduce bias [23] |

| Boosting | AdaBoost, Gradient Boost, XGBoost, and Cat Boost | Reduces bias, improves accuracy [16,17] | Can overfit, sensitive to noisy data [17,18] |

| Stacking | A stacking ensemble where a Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, and K-Nearest Neighbors classifier serve as base learners, and a Logistic Regression model is used as the meta-learner to combine their predictions for final classification | Combines strengths of multiple models [27,28] | Complex to implement, risk of overfitting [27,28] |

| Hybrid | Combination of bagging, boosting | Superior performance leverages multiple approaches [29] | Highly complex, challenging to tune [29]. |

| Voting | Combining Random Forest, SVM, and KNN, then vote between them | Improves prediction accuracy by leveraging diverse classifiers with its simplicity of implementation and interpretation [30,31,32,33,34]. | Depending on the performance of individual models, it may not perform well if models are highly correlated [30,31,32,33,34]. |

3. Related Work

In the last few years, researchers have been getting excited about “ensemble learning”. This approach has been making waves in the world of connected cars, especially when it comes to spotting cyber threats. Looking at what’s been published so far, we can see both the hurdles and breakthroughs in keeping these connected vehicles safe using ML. While there has been lots of research on different team-based learning approaches, two studies really stand out from the crowd: one by Ali et al. [35], and the other by Chiroma et al. [36].

Ali et al. [35] took a deep dive into how ML can help secure the conversations happening between vehicles. They highlighted just how important threat detection systems are for keeping vehicle networks safe. But they also pointed out some real challenges, such as current systems needing serious computing power, and cars are constantly moving around, which makes detecting threats in real-time pretty tricky. They suggested developing lighter-weight detection systems that could run on edge computing (i.e., processing data closer to where it is created rather than sending everything to a central server). Their work really opened eyes to the need for more efficient solutions that balance strong security with the practical limitations of connected cars.

Building on this foundation, Chiroma et al. [36] analyzed various ML frameworks for threat detection in vehicle networks. While they looked at many different types of models, they focused on addressing some key problems: vulnerability to adversarial attacks (where someone deliberately tries to trick the system), increased lag time, and high energy use. They suggested future research should prioritize developing models that can resist these tricky attacks while staying lightweight and energy-efficient, qualities that are essential in the constrained environment of connected vehicles. Their work highlights the growing need for threat detection systems that not only spot problems accurately but also use minimal resources and can adapt to new attack patterns on the fly. The authors advocate for creating open-access datasets and utilizing advanced architectures like memory-augmented networks and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to strengthen model generalization.

Together, these studies highlight two major gaps that need filling: we need lightweight models that can work effectively with limited resources, and we need systems that can handle emerging threats without taking a performance hit.

Almehdhar et al. [10] examined the use of ML, reinforcement learning, and transformer-based models for securing Controller Area Network (CAN) protocols in IoV. The study stresses computational inefficiency and lack of real-world CAN data as major barriers. Their recommendation is to design energy-efficient DL models and develop standardized, public CAN datasets for more robust IDS evaluation. Billah et al. [11] explored future security enhancements in vehicular IDSs using lightweight DL models and adaptive detection strategies. Their key limitation lies in the integration of real-time mechanisms into constrained vehicular environments, prompting the need for adaptive, scalable IDS frameworks. Al-Jarrah et al. [37] focused on IDS designs for in-vehicle networks, emphasizing hybrid and flow-based approaches tailored to CAN traffic. Their study reveals that current IDSs often fall short in detecting novel attacks and are hindered by the lack of standardized benchmarks. They call for future research on more effective lightweight IDSs with standardized evaluation protocols for CAN-based vehicular networks.

Table 3 shows a comparison of our survey with respect to previous similar work. Related surveys highlighted noteworthy successes and obstacles in implementing ML and DL methodologies to enhance intrusion detection and security within automotive networks and IoV.

Table 3.

A Comparison of Our Survey with Existing Related Surveys.

Previous research focused on lightweight anomaly detection frameworks, minimizing adversarial risks, and IDS designed for protocols like CAN, while also addressing limitations such as significant processing requirements, insufficient publicly available datasets, and computational efficiency. Meanwhile, our study conducts a comprehensive examination and evaluation of ensemble learning methodologies in IDS for IoV. Our findings in this review show the application of ensemble learning to mitigate trade-offs associated with resource utilization and system latency, while simultaneously enhancing accuracy, resilience, and flexibility. Moreover, this survey highlights the application of ensemble approaches to create scalable, efficient, and lasting IDS frameworks, hence expanding the variety of security solutions for practical IoV situations.

Our study examines related research on ensemble learning in detecting cyberattacks on vehicles. The survey discusses ensemble algorithms and ensemble voting methods. Besides, the multi-class IDS for IoV classifications is addressed. Finally, the gaps in the studies in detecting attacks targeting IoV are extracted, and recommendations are made aiming at a strong and enhanced security system in creating a safe environment for vehicles connected to IoV.

4. Ensemble Learning IDS for IoV: Research Trends and Gaps

As connected cars become more common on our roads, keeping their networks safe is getting trickier. We need better ways to spot cyber threats, and that’s where team-based learning approaches (i.e., ensemble learning) have been showing real promise. But looking closely at the current research, we can see some clear trends and gaps that need addressing if we want these security systems to work better and handle more cars. In their big review of the field, Ali et al. [35] highlight a growing problem: most security systems for connected cars are just too heavy. They need tons of computing power, which makes it hard to spot threats in real-time—a big issue when you’re dealing with fast-moving vehicles that can’t afford delays. They suggest future research should focus on creating lighter, more efficient security solutions that can work quickly without sacrificing accuracy. This points to a major gap in current research—we desperately need security models that are lightweight and can scale up easily, adapting to the constantly changing, resource-limited environment of vehicle networks.

In a similar vein, Talpur and Gurusamy [38] shine a spotlight on another challenge: making these systems harder to fool. Traditional security systems often struggle when faced with sophisticated attacks designed specifically to slip past their defenses. They recommend developing security models that can stand strong against these clever attacks and adapt to new threat patterns they haven’t seen before. This matches the growing need for security systems that don’t just work well under normal conditions but stay robust when facing evolving and unexpected attacks.

These findings from both research teams highlight two key gaps that need filling:

- The need for lightweight models that can run efficiently in real-time on connected vehicles without hogging limited resources.

- The need for systems that are resilient against sophisticated attacks, security that can take a punch and still do its job.

In Table 4, we summarize and compare the different studies on ensemble learning for multi-class IDS for IoV.

Table 4.

Summary of the recent studies on ensemble learning algorithms in IDS for IoV.

Recently, Saheed et al. [39] proposed an explainable ensemble transfer learning model aimed at detecting zero-day attacks in IoV systems. Their work stands out by combining ensemble learning with explainable AI (XAI) components, allowing not only for high detection accuracy but also for greater interpretability of decisions made by the model. The approach addresses key gaps in transparency for mission-critical security applications in vehicular networks. Moreover, Selvakumar et al. [40] introduced a hybrid ensemble architecture combining Feature-Augmented Convolutional Neural Networks (FA-CNN) with Deep Autoencoders for intrusion detection in NIDS. This model showed strong performance on NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017, especially in handling minority attack classes. While scalability remains a concern, the study provides valuable insights into deep hybrid ensemble design for high-dimensional security data.

A stacked ensemble model was developed in [41], leveraging multiple base classifiers including Random Forest, KNN, and XGBoost, coupled with advanced correlation-based and embedded feature selection. Their model achieved 99.99% accuracy on two benchmark datasets and effectively addressed data imbalance using the Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE)-Tomek method. This work highlights how stacked models combined with robust feature engineering can significantly boost detection performance in IoV environments.

Jin et al. [56] introduced a federated ensemble learning model incorporating class-incremental learning to ensure continuous adaptation to evolving threats in IoV. Their work emphasizes the importance of lifelong learning strategies in IDS and achieves consistent accuracy (~97%) with reduced false positives. This makes it well-suited for highly dynamic vehicular networks that require evolving defense mechanisms. In the same year, other researchers developed a hybrid ensemble IDS using optimization algorithms like RFE, SAEO, and PSO, integrated with classifiers such as Adaboost, SVM, DNN, and XGBoost [67]. Their comprehensive ensemble pipeline significantly boosts precision, sensitivity, and F1-score. Despite its computational demands, the system achieves greater than 99% accuracy, demonstrating its strength across multiple benchmark datasets.

Ali et al. [63] designed an ensemble learning system that leverages gossip learning in distributed V2X environments. Their IDS model enhances scalability and robustness by facilitating knowledge sharing between nodes in the network. The approach demonstrated improved detection performance and resilience in vehicular communication systems, though communication overhead remains a challenge. Meanwhile, other researchers proposed a tree-based ensemble framework tailored for multi-class IDS in IoV [60]. Their model integrates multiple decision tree algorithms to classify network traffic into distinct attack categories with high precision. The work stands out for its interpretability and effectiveness across multiclass detection tasks, particularly in environments requiring rapid decision-making under constrained resources. Federated learning with diverse ML models was combined in [65] in a decentralized architecture designed for privacy-preserving IDS in IoV. Their approach integrates SMOTE, outlier detection, and hyperparameter tuning to adapt to class imbalance and noisy data. The model is notable for its ability to scale across devices while maintaining strong detection performance and data confidentiality. With transfer learning and hyperparameter tuning, researchers introduced a lightweight IDS model using MobileNetV2 [64]. Their approach caters to resource-constrained IoV environments by balancing detection accuracy and processing efficiency. The model showed strong performance in intrusion detection tasks, although it may need further evaluation against sophisticated attack vectors.

Previous studies on IoV intrusion detection, particularly the analysis of various ensemble learning techniques as illustrated in Table 4, have shown through the works in [52,68] that these strategies significantly enhance the accuracy of identification while reducing the incidence of false positives. Nevertheless, additional obstacles persist, such as the necessity for rapid, flexible solutions and the creation of models that can react to emerging security issues. Particularly via ensemble approaches like RF, Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM), and AdaBoost. Developments in DL and ML have significantly raised the efficacy of IDS for the IoV [57,69]. Notwithstanding these developments, IDS’s ability to meet the changing and immediate needs of IoV environments remains limited. Computational restrictions and delays impede their use in time-sensitive applications, particularly in systems like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Deep Neural Networks (DNNs). Optimization techniques such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [70] would help to improve the scalability and efficacy of ensemble models.

Shahriar et al. [44] highlighted the application of ensemble learning in developing IDS for Vehicular Ad Hoc Networks (VANETs). These networks rely on intricate and dynamic communication structures, which make them highly vulnerable to various cyber threats, including DoS and Sybil attacks. Ensemble learning, through methods like RF and Gradient Boosting, combines multiple machine learning algorithms to enhance the accuracy and robustness of IDS. Unlike traditional IDS models that rely on static, pre-defined feature sets, ensemble approaches adapt dynamically to emerging attack patterns and evolving vehicular traffic conditions. This adaptability ensures a more reliable defense mechanism for VANETs, as demonstrated in findings.

Another research has shown that several ensemble strategies are useful in IDS for IoV. Limouchi and Chan [42] suggested that utilizing a combination of classifiers, namely XGBoost, Extra Trees (ET), and LightGBM, significantly improves the detection performance. Anthony and Elgenaidi [43] argued that non-tree-based ensemble algorithms can efficiently detect intrusions in self-driving automobile systems. However, the complex and diverse structure of automobile network traffic may sometimes exceed the capabilities of traditional single-model approaches. Ensemble methods are a favorable choice for IDS in IoV scenarios as they integrate many learning algorithms that are fine-tuned using methods such as Bayesian Optimization. By enhancing the precision of intrusion detection, this approach also reduces the frequency of false positives. In [44], the authors highlight the importance of feature extraction and selection in improving the performance of ensemble learning models. Data imbalance concerns, which are frequently encountered in IDS datasets, can be efficiently resolved by employing correlation-based feature selection and synthetic minority oversampling techniques (SMOTE). Furthermore, Al-Hawawreh and Hossain [45] acknowledge the potential for system delays but contend that the implementation of federated ensemble learning in IDS has the potential to improve both privacy and scalability. However, other researchers suggest that optimization techniques like GA and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) can be used to adjust model parameters, thereby improving the overall efficiency of IDS [46,71]. Additional studies are required to fully comprehend the capabilities of ensemble-based IDS in terms of scalability and real-time use in vehicular networks with restricted resources.

The discourse over the application of DL methodologies in ensemble situations is significant. The research carried out in [48,49] showcases the application of DNNs in extracting complex features from network traffic data. However, the substantial computational expense and extended training period of DNNs greatly hinder real-time intrusion detection. According to Yang et al. [72], the combination of DNNs with ensemble methods can effectively utilize the advantages of both approaches, resulting in improved accuracy and robustness in IDS. Anand et al. [73] expressed disapproval of the use of static datasets in previous research and advocate for the adoption of adaptive learning techniques that can adapt to evolving threat scenarios. Thus, while DL shows great potential, further improvement is needed to strike a balance between accuracy and efficiency before it can be effectively used in IDS for IoV.

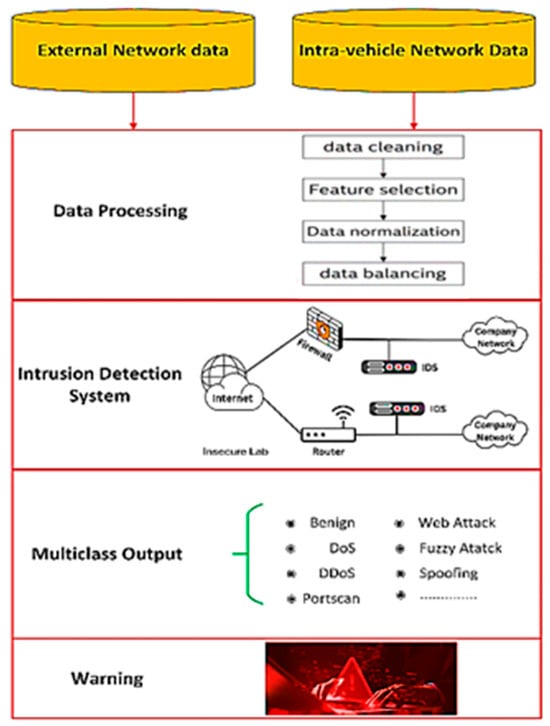

An example of a Multi-Class IDS using Tree-Based Ensemble Learning is demonstrated in Figure 3. The methods used excel in handling high-dimensional vehicular data by aggregating multiple DTs to improve classification accuracy. In a multi-class context, the IDS categorizes network behavior into benign activities and multiple types of malicious attacks, such as DoS, Sybil, and spoofing attacks. Tree-based ensemble methods are particularly effective due to their ability to capture complex feature interactions while minimizing overfitting.

Figure 3.

Example of Multi-Class IDS using Tree-Based Ensemble Learning [34].

Additionally, techniques like feature importance and pruning ensure that the system remains computationally efficient, which is critical for real-time deployment in dynamic VANETs and IoV settings. Table 4 summarizes the most relevant studies of ensemble learning algorithms in IDS for IoV.

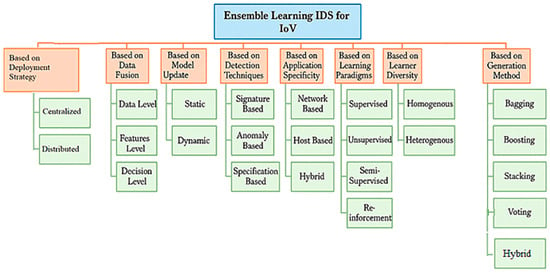

4.1. Ensemble Learning IDS for IoV Taxonomy

Based on the literature covered in this study, a taxonomy was identified for the ensemble learning approaches as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Taxonomy of EL IDS for IoV.

4.1.1. Based on Deployment Strategy

The deployment of ensemble learning techniques in IDS for IoV involves two prominent strategies: centralized and distributed. These strategies address different aspects of the research problem by balancing scalability, real-time efficiency, and data privacy.

Centralized Techniques

Data from many IoV nodes is consolidated at one server. This approach helps to execute computationally demanding operations at the edge or node level that would otherwise be difficult at that level. In order to solve the challenge of intrusion detection in large-scale IoV networks, Boualouache and Engel [69] developed centralized ensemble learning techniques Using RF and Gradient Boosting. The study addressed the challenges of heterogeneous vehicle data on the cloud.

Using the computing capability of cloud infrastructures, the centralized deployment improved the system’s ability to recognize complex attack patterns. Still, the study identified potential drawbacks, particularly in real-time applications, including latency and single point of failure sensitivity. Lampe and Meng [74] underlined the capacity of centralized deployment to manage large datasets for thorough investigation. Emulating real-world events via centralized ensemble learning allowed the researchers to address the scalability challenge of processing data from several vehicles. Their results underlined the benefits of centralized systems in terms of accuracy and admitted delays and resource constraints as areas that still need development. Moreover, the studies in [13,60] are based on centralized architecture using tree-based and lightweight ensemble strategies.

Distributed Deployment

This option allows us to achieve decentralized intrusion detection by means of local processing at IoV nodes, either automobiles or roadside equipment. By processing data locally rather than forwarding it to a central server, this method reduces latency, improves real-time threat detection, and preserves data privacy. In a distributed deployment system, Sani et al. [61] combined federated learning with ensemble approaches. Using this method keeps data locally and centralizes model updates to help solve privacy issues. The study showed how this method reduced data breach risk while nevertheless enabling scalability for large IoV networks. Reducing the links between nodes and the central server helped to reduce the communication overhead, therefore improving the system’s practical relevance. Haddaji et al. [75] examined distributed ensemble models inside edge computing environments. Using ensemble classifiers on edge devices, this work addressed the scalability problem by enabling real-time intrusion detection free of major reliance on central servers. Studies in [63,65] are good examples of federated, gossip-based, and privacy-aware distributed models. The distributed design of this approach lets the IDS effectively manage several vehicle network circumstances. Moreover, the study in [76] proposes a Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL)-based federated self-supervised learning framework tailored for task offloading and resource allocation in Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC)-enabled vehicle edge computing environments. The approach enhances security and efficiency in decentralized IoV systems by enabling vehicles to collaboratively learn optimal policies while preserving data privacy. It effectively addresses challenges such as limited bandwidth, dynamic environments, and data heterogeneity, making it highly relevant to privacy-preserving and intelligent intrusion detection and decision-making in IoV.

4.1.2. Based on Data Fusion Technique

Data-Level Fusion

Data-level fusion is the integration by ensemble learning models of unprocessed data from numerous IoV nodes prior to analysis. Data-level fusion was carried out in [69], combining network traffic data from several vehicle nodes into a single repository. To examine large volumes and expose complex, scattered attack patterns across IoV networks, this aggregation helped assemble models including RF and Gradient Boosting. Using data-level fusion inside a federated learning system, Sani et al. [61] combined data from many IoV nodes and recognized different risk behaviors while maintaining individual privacy.

Feature-Level Fusion

Feature-level fusion combines elements from many data sources into a single feature set so that ensemble models may operate with improved accuracy and relevant data representation. Geographical and temporal data from IoV traffic were used in [75] to accomplish feature-level fusion. Using ensemble techniques such as RF and AdaBoost, the generated feature set was examined to improve anomaly detection precision and lower repetition. By feature-level fusion, the researchers in [77] combined contextual data, including road and weather conditions, with vehicle-specific data. This method enabled the ensemble system to fit changing IoV parameters, therefore addressing dynamic and contextually sensitive threats. Tran et al. [40] proposed a novel ensemble approach integrating feature augmentation and deep learning for robust intrusion detection and achieved 97% accuracy on NSL-KDD and 95% on CICIDS2017 datasets, outperforming existing methods.

Decision-Level Fusion

Decision-level fusion combines the outputs of several classifiers inside an ensemble model to get a final decision. Using decision-level fusion, the authors combined classifier predictions, including those of Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Neural Networks [57]. By adding weighted averaging and majority voting, the ensemble framework reduced false positives in IoV IDS and improved durability. Using decision-level fusion in centralized IDS settings, Lampe and Meng [74] generated outputs for the conclusion by means of ensemble models trained on many datasets. By reducing the consequences of individual model errors, this fusion approach improved the general dependability of the system.

4.1.3. Based on Model Update Mechanisms

Two fundamental methodologies are employed: dynamic and static updating. While static models adhere to a fixed structure, dynamic models adapt to evolving conditions inside the IoV environment. Both methodologies tackle several security concerns associated with IoV.

Static Models

Static models are often instructed offline using a predetermined dataset, possess fixed architecture. This technique is appropriate for situations with relatively stable threat patterns due to its reduced complexity and processing demands. In 2023, Lampe and Meng [74] analyzed stationary ensemble models for centralized IDS. By training models like RF and GBon extensive, varied datasets, they tackled the issue of accurately identifying recognized attack patterns. Their findings indicated that in dynamic IoV scenarios, static models may be inadequate for addressing evolving threats. Ahsan et al. [48] employed a centralized methodology to amalgamate network traffic data for static ensemble models aimed at intrusion detection. Static models were effective for known threats; but their inflexibility hindered the management of zero-day attacks and emerging trends, highlighting the necessity for more real-time methodologies.

Dynamic Models

Dynamic models are highly beneficial for the rapidly evolving IoV environment due to their ability to adjust to new data and shifting danger scenarios. Due to their continual assimilation of new data, these models are resilient and pertinent. Ghaleb et al. [57] introduced a dynamic ensemble learning system that incorporates real-time classifier upgrades in reaction to newly identified attack patterns.

This method mitigates evolving IoV threats by enabling the IDS to remain effective against previously unrecognizable attacks. Haddaji et al. [75] conducted dynamic updates in an edge computing environment by routinely retraining ensemble classifiers using the latest IoV traffic data. This technique effectively addresses scalability issues by reducing latency and enhancing detection accuracy in resource-constrained applications. In 2024, Tran et al. [77] presented a hybrid dynamic model update approach that integrates adaptive ensemble approaches with federated learning. Their solution solved the dual challenges of real-time flexibility and privacy preservation by enabling the IDS to adjust according to evolving IoV conditions, hence safeguarding data privacy. Saheed and Chukwuere [39] improved the detection of previously unseen attacks with potential computational complexity due to ensemble and transfer learning integration. They introduced an explainable ensemble model tailored for IoV, addressing the challenge of zero-day attack detection. Moreover, they demonstrated high accuracy in identifying zero-day attacks with added model transparency.

4.1.4. Based on Detection Methods

Signatures Based

Detection based on signatures depends on recognized attack patterns. It struggles to identify zero-day attacks but is good at spotting previously known vulnerabilities. Using signature-based ensemble models in centralized IDS, Lampe and Meng [74] found recurrent IoV intrusions. RF and DTs were combined to improve detection accuracy for known hazards. Emphasizing the need for additional detection techniques, the study revealed the limits of signature-based methods in handling novel hazards. Using ensemble techniques for signature-based detection on aggregated traffic data, Boualouache and Engel [69] effectively found recurrent attacks; yet, because IoV environments are dynamic, they require regular updates to keep effectiveness.

Anomaly Based

Anomaly-based detection is especially effective in spotting unknown and zero-day attacks. Using classifiers including SVM and Neural Networks, Ghaleb et al. [57] created anomaly-based ensemble learning models. This solution used the adaptability of ensemble methods to detect abnormal patterns in vehicle traffic, therefore addressing the problem of spotting new hazards in IoV systems. Using ensemble techniques, Haddaji et al. [75] investigated real-time traffic data with an eye toward anomaly detection in edge computing environments. An adaptive feature of anomaly-based detection improved the IDS’s ability to handle changing attack strategies and reduced scalability problems.

Specification Based

Specification-based detection calls for exact criteria and limits to spot violations. It works especially well for spotting attacks targeted at IoV programs or protocols. Tran et al. [77] improved IoV communication protocol security by using specification-based ensemble learning models. Their strategy reduced false positives and improved system accuracy in finding protocol-specific breaches by combining rule-based detection with ensemble techniques. By means of the integration of specification-based detection and federated learning inside a distributed architecture, Sani et al. [61] addressed privacy issues while preserving exact detection for IoV applications. In distributed systems, this hybrid approach addresses the difficulty of maintaining accuracy while complying with protocol-specific criteria.

4.1.5. Based on Application Specificity

Network-Based IDSs

These systems track network traffic looking for hostile activity. Ensemble learning improves the precision and scalability of these systems. Within a network-based intrusion detection system, Boualouache and Engel [69] used ensemble learning to evaluate traffic from several IoV nodes. To address the difficulty of spotting scattered attacks over large IoV networks, their method used classifiers such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting. The studies show improved detection accuracy and the capacity to identify complex network-level intrusions. Lampe and Meng [74] looked at network-based ensemble learning models housed under centralized systems. Their work focused on combining traffic data for ensemble classifier processing, thereby enhancing the identification of volumetric attacks, particularly to protocols. Two highlighted shortcomings in real-time scenarios were scalability and latency.

Host-Based IDSs

These systems seek to monitor certain devices, such as cars, for signs of illegal access. This method lowers transmission overhead and supports more localized data analysis. Using host-based IDS and ensemble learning approaches, Haddaji et al. [75] examined statistics from individual automobile systems to find host-level abnormalities with light-weight classifiers like AdaBoost and DTs. This method effectively solves resource constraints in IoV devices and maintains excellent detection accuracy. To improve security and privacy, Tran et al. [77] used federated learning in concert with host-based IDS. Analyzing data on host devices and distributing model changes allowed their ensemble approach to meet privacy protection and real-time adaptation.

Hybrid IDSs

In a hybrid IDS, ensemble learning helps to detect threats completely. In 2020, Ghaleb et al. [57] created a hybrid IDS architecture combining network traffic analysis with host-level log monitoring. To address the difficulty of identifying intricate multi-vector attacks, the study applied ensemble classifiers incorporating neural networks and SVM. While improving detection coverage, the hybrid approach lowered false positives. In 2022, Sani et al. [61] presented a hybrid ensemble learning system using networked topologies. Their method guaranteed dependable detection by combining host-level and network data, hence reducing transmission costs. This approach was particularly effective in spotting coordinated attacks across different IoV zones.

4.1.6. Based on Learning Paradigms

Supervised Learning

Supervised learning is more successful at detecting known attack patterns when models are trained using labeled datasets. The centralized IoV IDS framework proposed in [74] makes use of supervised ensemble models, such as RF and Gradient Boosting. These techniques achieved pinpoint accuracy by spotting typical attack patterns in annotated data on network traffic. Nevertheless, the difficulty of maintaining accuracy in the face of shifting, unexplained risks was brought to light by their results. In their study, Boualouache and Engel [69] utilized supervised ensemble learning to merge labeled data from several nodes. To improve the model’s capacity to identify protocol-specific risks, they used a technique that dealt with feature variability in IoV traffic.

Unsupervised Learning

Finding zero-day attacks and unexpected dangers is a breeze with unsupervised learning since it can spot trends and anomalies without labeled data. Haddaji et al. [75] used unsupervised ensemble models featuring DT clustering approaches in conjunction with others to examine unlabeled data from IoV. Unusual occurrences that may indicate novel forms of attacks were identified with the use of this method. The significant issue of insufficient labelled datasets in IoV IDS was effectively addressed in this study. Tran et al. [77] used unsupervised ensemble learning to study evolving attack patterns as part of their hybrid IDS. By focusing on anomaly identification in real-time, this approach mitigates issues caused by zero-day vulnerabilities.

Semi-Supervised Learning

One middle ground between supervised and unsupervised approaches is semi-supervised learning, which uses both labelled and unlabeled data. To make this paradigm better, ensemble methods that take advantage of the scarcity of labelled data are used. Ghaleb et al. [57] employed semi-supervised ensemble models to facilitate learning on a bigger unlabeled dataset in conjunction with a small sample of labelled IoV traffic data. They were able to overcome the lack of data while keeping detection accuracy for unknown attacks at a high level with their method. A semi-supervised ensemble system was introduced in [61] in the context of a federated learning environment. An effective method for detecting dispersed IoV nodes was developed by combining unlabeled network traffic with labelled host-level data.

Reinforcement Learning

This method places an emphasis on learning by contact with one’s environment and is well-suited to the ever-changing environment of IoV. Reinforcement-learning-based ensemble learning enhances both adaptation and decision-making for IoV IDS. Boualouache and Engel [69] reinforcement-based ensemble learning could adapt to new threats because it used real-time data to train its classifiers. Similarly, Tran et al. [77] implemented a reinforcement-based ensemble learning IDS that can learn and adjust to new attack patterns. This solution tackled the problem of real-time flexibility and resource constraints simultaneously in IoVs.

4.1.7. Based on Learner Diversity

Homogeneous Ensembles

Homogeneous ensembles are distinguished by factors like training data or parameter values. Boualouache and Engel [69] created homogeneous ensembles where several DTs were combined using RF and other techniques to improve the recognition of common attack patterns in IoV traffic. This approach maintained outstanding accuracy for some attack forms, hence reducing the problem of insufficient computational efficiency. Lampe and Meng [74] looked at how homogeneous ensemble models, including GB, might improve centralized IDS. Their studies showed that homogeneous learners could manage large amounts of IoV data; yet, they were limited in their ability to handle dynamic and multi-vector attacks. Ghaleb et al. [57] developed a heterogeneous ensemble learning system combining SVM, neural networks, and k-Nearest Neighbors. Their approach used several classifiers to ensure reliable identification of complex attack patterns, therefore addressing the management of multi-vector attacks in IoV systems. Tran et al. [77] developed a hybrid heterogeneous ensemble system that combines lightweight models at the edge with deep models on centralized servers for thorough investigation, therefore addressing the scalability issue. Their system shows flexibility to change attacks and effective use of computational resources. In order to solve privacy concerns, Sani et al. [61] developed a federated learning system including several ensembles. By combining classifiers, including RF and NN, over numerous IoV nodes, their approach improves detection precision and privacy.

4.1.8. Based on Generation Method

Bagging

Many models produced via bagging, sometimes known as bootstrapping aggregating, reduce variance and improve resilience. To control various vehicle data, Lampe and Meng [74] used bagging-based ensemble models incorporating RF. This approach greatly lowered overfitting and improved the IDS’s ability to find anomalies in large-scale IoV networks. By aggregating forecasts from numerous models, the study showed improved accuracy in spotting recognizable and somewhat familiar attacks. Using bagging inside an edge-computing architecture for IoV IDS, Haddaji et al. [75] proposed a bagging-based model with lightweight properties for solving computational efficiency and scalability problems to enhance their usability with limited resources.

Boosting

Boosting improves general model accuracy by repeatedly combining weak classifiers and giving misclassified events more weight. Advanced persistent threats in IoV environments were found by Boualouache and Engel [69] using GB. Their approach steadily improved weak classifiers to achieve remarkable accuracy in spotting complex attack patterns. Still, the study noted that increasing real-time applications results in a computational cost. Sani et al. [61] examined how AdaBoost might be used in IDS. This method guarantees effective communication among IoV nodes and improves detection accuracy, therefore addressing the two privacy and scalability concerns.

Stacking

Superimposing stacking combines predictions from several models using a meta-classifier, therefore utilizing the complementary benefits of different models. With predictions from SVM, DTs, and NN, Ghaleb et al. [57] established a stacking ensemble framework. Their system’s meta-classifier reduced false positives significantly and improved its flexibility to new anomalies, therefore helping in dynamic IoV settings. Employing host- and network-level data, Tran et al. [77] combined stacking into a hybrid IDS using the capabilities of distinct models, particularly for complex attack paths; their method improved detection coverage and precision. Ghaleb et al. [57] utilized a stacking ensemble approach with advanced feature selection to enhance intrusion detection. They achieved high performance with an accuracy of 99.99% on both NSL-KDD and CIC-IDS datasets, effectively handling imbalanced datasets using the SMOTE-Tomek technique. Moreover, Nassreddine et al. [41] were based on stacked ensemble frameworks with multiple base classifiers.

Voting

Voting produces final predictions by aggregating the results of numerous classifiers using weighted or majority votes. Voting ensembles with edge computing were used in 2024 in [75]. The authors combined efficient classifier predictions to enable real-time decision-making in resource-constrained environments. The voting system improved the individual mistake robustness of the model. Lampe and Meng [74] combined models trained on centralized datasets via voting. Their results showed how voting preserved the simplicity of implementation while raising general detection accuracy.

4.2. Ensemble Learning-Based Multi-Class IDS for IoV

By analyzing the provided taxonomy, we conclude that there is still a notable gap in existing research, specifically, it is still challenging to create a scalable, lightweight IDS that can effectively operate in dynamic IoV contexts. In order to meet the requirements of real-time detection and computing limitations, it is imperative for future research to prioritize the enhancement of ensemble learning algorithms. Moreover, it is essential to preserve and enhance databases to accurately reflect the latest threat scenarios.

Ghaleb et al. [57] applied ensemble learning through Random Forest, Gradient Boosting Machine, and AdaBoost to build a multi-class IDS tailored for dynamic IoV environments. Their model achieved a detection rate of 98.7% and effectively minimized false positives (2.3%), proving the strength of ensemble methods in reducing misclassification, though at the cost of increased computational complexity. In 2021, Yang et al. [72] created a hybrid IDS by combining known and zero-day attack detection mechanisms, achieving 97.2% accuracy. The ensemble demonstrated balanced precision and recall across multiclass labels, supporting hybrid approaches for comprehensive IoV protection.

Zhao et al. [62] introduced a clock-skew-based ensemble IDS, achieving 98.1% detection with 1.5% false alarms. Their novel approach emphasizes real-time synchronization signals for anomaly detection, offering lightweight yet reliable solutions for time-critical vehicular applications. However, Aggarwal and Kaddoum [58] addressed intrusion detection through machine learning-based routing in VANETs. The ensemble model attained a detection accuracy of 97.3%, improving traffic flow efficiency while detecting anomalies. However, the method requires complex integration with underlying routing protocols, posing deployment constraints. Anyanwu et al. [59] advanced the field with a hyperparameter-tuned Random Forest ensemble, achieving a leading 99.2% detection rate and 1.8% false alarm rate. Their study proves that careful parameter optimization significantly enhances real-time intrusion detection performance, particularly in latency-sensitive vehicular networks. Random Forest has been ensembled with CNN to detect diverse intrusion types in high-dimensional vehicular traffic [69]. The researchers’ model reached 98.5% detection accuracy with a 2.5% false alarm rate, highlighting the robustness of hybrid architectures in handling feature-rich inputs, though real-time deployment remains challenging. The authors in [58] integrated LSTM with hybrid ensemble learning for sequential data processing. Their 97.5% detection rate and 1.9% false alarm rate demonstrate that temporal modeling in IDSs can significantly improve anomaly detection in complex vehicular patterns. Ahsan et al. [48] implemented a stacked ensemble tailored for software-defined VANETs. Despite achieving 97.5% accuracy and 1.8% false alarms, the model faces difficulties with real-time responsiveness, underscoring the tradeoff between depth of learning and execution time. Al-Hawawreh and Hossain [45] proposed a federated IDS integrated with satellite mesh networks, achieving 95.9% accuracy. Their design prioritizes scalability and privacy in multi-class detection but remains hindered by the latency inherent in satellite communications. The researchers in [74] used a two-stage deep learning ensemble with DNNs to detect vehicular attacks with 97.9% accuracy. Their model shows strong generalization for various intrusion types, yet it requires intensive computational tuning and dataset balancing strategies. Limouchi and Chan [42] presented a highly optimized ensemble combining LightGBM, Extra Trees, and XGBoost. With a detection rate of 98.2%, their model showcases superior accuracy and low latency performance, reflecting the power of hyperparameter-driven ensemble design. In [53], the authors proposed a collaborative cloud-vehicle IDS architecture based on ensemble learning. Their model achieved 97.6% detection with strong adaptability, offering a viable path for distributed multi-class detection frameworks with minimal onboard processing requirements. Shahriar et al. [44] employed correlation-based feature selection and SMOTE in their ensemble, achieving 97.8% detection. Their model shows strong resilience to data imbalance, a common challenge in real-world IoV datasets, and provides a robust baseline for preprocessing-focused IDS design. The authors in [51] introduced a DL-based adaptable ensemble framework capable of detecting zero-day attacks with 97.4% accuracy. Their contribution lies in the model’s continuous learning capacity, making it highly suitable for evolving threat environments. Tu and Shang [46] conducted a comparative study of Logistic Regression, Random Forest, and Decision Trees within an optimized ensemble, achieving 97.3% accuracy. Their findings validate the role of extensive hyperparameter tuning in boosting classifier robustness for real-time IoV IDS. Al-Hawawreh and Hossain [45] emphasized the impact of feature reduction through RFE and PCA in ensemble IDSs. Achieving 96.7% detection, their model demonstrates that careful dimensionality reduction can boost classifier performance without sacrificing generalization.

Recently, Alalwany and Mahgoub [78] proposed a federated ensemble learning framework that integrates distributed learners across edge nodes to maintain privacy in decentralized IoV systems. With a detection rate of 97.9%, the approach demonstrated strong scalability and data confidentiality, despite facing coordination and communication overheads during model synchronization. Researchers in [75] introduced a deep ensemble combining DNNs and Graph Neural Networks, designed for IoV scenarios with complex relational data. Their system recorded a 99.0% detection rate and 1.9% false alarm rate, validating the effectiveness of graph-based learning in capturing spatial-temporal dependencies of vehicular threats. Xiao et al. [79] employed a Graph Node Attention Network for multi-class detection, achieving 98.8% detection with only 2.2% false alarms. Their method excels in extracting topological and contextual traffic features in large-scale vehicular graphs, offering an interpretable yet scalable solution for next-gen IDS. Zhang et al. [50] proposed GRIPCA combined with OWELM to deliver a lightweight and fast IDS, suitable for real-time inference. Their model reached 99.1% accuracy and 1.7% false alarms, emphasizing both detection effectiveness and efficient resource consumption, a valuable tradeoff for embedded vehicular systems.

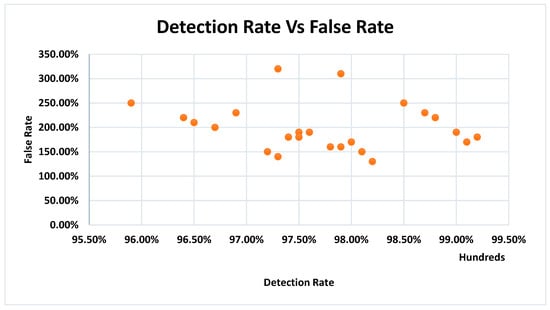

Anthony [43] evaluated non-tree-based ensemble techniques in IoV IDS. Their model achieved a 96.5% detection rate with improved precision and reduced false positives, presenting a compelling alternative to tree-heavy ensemble paradigms in adversarial environments. Kim et al. [52] proposed sensory anomaly detection through ensemble methods, reaching 96.9% detection. Their study underscores the importance of mixed sensory data in automotive environments and calls for more sophisticated ensemble handling of sensor fusion. Korium et al. [49] focused on boosting-based ensemble learning, leveraging hyperparameter tuning to achieve 98.0% detection accuracy. Although efficient, real-time adaptation remains a bottleneck, especially under varying vehicular traffic conditions. Jasim et al. [54] applied ensemble learning to traffic congestion detection in VANETs, achieving 96.4% accuracy. While their approach focuses more on traffic prediction than intrusion detection, it demonstrates the versatility of ensemble frameworks in vehicular systems. Figure 5 summarizes the performance of the existing ensemble learning-based Multi-Class IDSs for IoVs.

Figure 5.

Detection and False Rates.

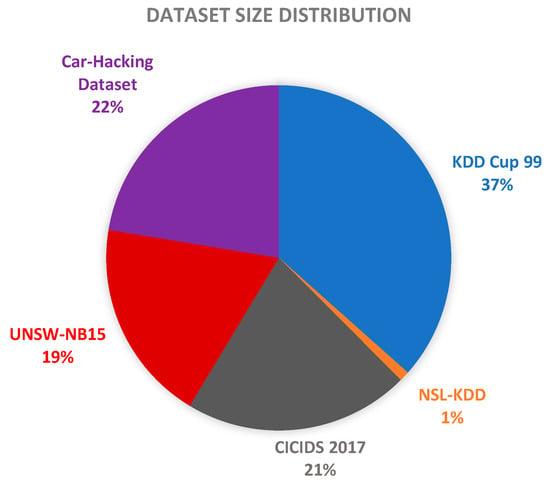

4.3. Datasets Used for IoV IDS

The evaluation of ensemble learning-based multi-class IDS for IoV heavily relies on the quality and variety of datasets used. These datasets are essential for training, validating, and testing IDS models, ensuring their robustness and reliability in real-world scenarios. Various datasets have been employed in existing research, each offering unique attributes and challenges. Figure 6 is a pictorial view of the dataset’s sizes.

Figure 6.

Dataset Sizes.

Table 5 summarizes the datasets used in IoV intrusion detection. These datasets provide a comprehensive basis for the evaluation of various detection models. They address specific challenges and scenarios pertinent to vehicular networks, enhancing the relevance and applicability of the research findings.

Table 5.

Common Datasets for IoV IDS.

As can be seen in Table 6, the number of features varies from one dataset to another, which may affect the recognition rate after training either positively or negatively. Actually, it depends on the relevance of these features and their importance.

Table 6.

Ensemble Learning-based Multi-Class IDS Performance Comparison.

Referring to what is being noted from the literature, high usage datasets like KDD Cup 99 and CICIDS 2017 are popular for their respective benchmarks in legacy and modern research. Moreover, specialized datasets like Car-Hacking have limited usage but are invaluable for automotive-focused studies. Legacy datasets (e.g., KDD Cup 99) are outdated but still referenced for benchmarking. Modern datasets like CICIDS 2017 and UNSW-NB15 provide recent attack patterns and feature engineering capabilities. Datasets like Car-Hacking offer domain-specific insights, while general-purpose datasets like CICIDS 2017 enable broad applicability. Table 7 provides a structured overview of the datasets, facilitating easy comparison and helping in the selection of appropriate datasets for IoV IDS research.

Table 7.

Analysis of Common Datasets Used in IDS for IoV.

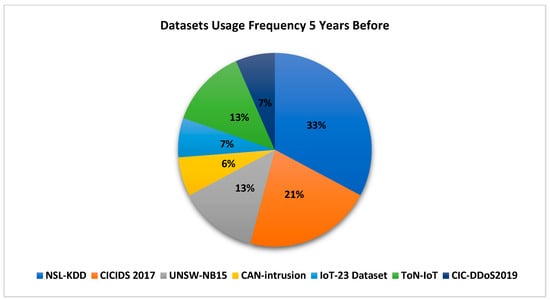

From the literature and back to 5 years, Figure 7 represents the usage percentage of each dataset.

Figure 7.

Datasets Usage Percentage for IoV IDS.

4.4. Evaluation Metrics Used for IoV IDS

Each ensemble learning model was trained on the selected features from the datasets. The models were evaluated using a range of performance metrics to ensure a comprehensive assessment, as demonstrated in Table 8. Accuracy and Area Under Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC) are commonly utilized metrics to evaluate general system performance as well as the trade-offs between false positives and false negatives. Authors in [74] assessed centralized IDS systems using these criteria and reported rather high detection accuracy.

Table 8.

Evaluation Metrics.

According to Boualouache and Engel [69], precision and recall are crucial in circumstances with unbalanced datasets to guarantee the identification of negative actions while reducing false positives and hence lower false positives.

The study in [75] stressed recall for recognizing zero-day attacks in edge contexts, while the research in [61] focused on specificity to lower false positives in federated learning-based IDSs. Especially in real-time applications, researchers in [77] and others argue that the F1-score offers a fair assessment of performance. By means of these approaches, researchers can enhance ensemble learning-based IDSs, particularly designed to meet the many and dynamic needs of IoV. These criteria should be included in hybrid evaluation systems in future studies to properly manage accuracy, scalability, and flexibility in evolving IoV contexts.

5. Discussion

These studies use a variety of approaches and datasets, but common constraints appear, highlighting the inherent issues of cybersecurity in automotive and IoT networks. These include investigating various real-world circumstances and hardware constraints that may impact the practical implementation and scalability of suggested models. Furthermore, numerous studies failed to mention their limits, highlighting a broader issue in cybersecurity research: the need for transparency and recognition of potential flaws. Another limitation found in various previous studies is the limited use of real data sets, which ensures scalability in the real world. Furthermore, relying on legacy datasets for training may limit generalizability across diverse and dynamic traffic scenarios. Furthermore, the studies lacked comparisons to previous research and novel models for detecting intrusion.

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of ensemble learning for intrusion detection in Internet of Vehicles (IoV) environments. The findings provide an accurate overview of the current state of the field and highlight key factors influencing the development and implementation of IDS in IoV systems.

The results of our study indicate that the performance of IDS is greatly influenced by the choice of datasets. Although the KDD Cup 99 dataset is outdated, it remains an important resource due to its comprehensive coverage of many network intrusion types. This supports the argument made in [74] that performance measurements obtained from past data are valuable. Conversely, it can be argued that newer datasets like NSL-KDD offer a more precise representation of the current state of the network by resolving the problems of duplication and imbalance found in KDD Cup 99 [81]. The results indicate that whereas old datasets are valuable for comparing and evaluating performance, contemporary datasets are essential for creating models that can effectively address present attacks.

The study emphasizes the significance of the CICIDS 2017 dataset in evaluating temporal attack trends due to its provision of up-to-date and accurate traffic conditions. The findings in [69] confirm the importance of time-based analytical characteristics in datasets such as CICIDS 2017 for detecting dynamic attack patterns in IoVs. These findings suggest that including such datasets in IDS evaluation can enhance the resilience of the model and improve its ability to detect real-world threats with greater accuracy.

Moreover, the UNSW-NB15 dataset encompasses a diverse array of attack scenarios, which greatly facilitates the creation of dependable IDS models. To enhance the applicability of IDS models, [57,59] highlights the importance of utilizing up-to-date datasets that accurately reflect the prevailing threat scenarios. Our research indicates that incorporating datasets like UNSW-NB15 can enhance the effectiveness of detection systems by enabling them to handle a broader spectrum of attack vectors. This conclusion indicates that for IDS models to remain pertinent and efficient, forthcoming research should give priority to varied and up-to-date datasets.

The Car-Hacking Dataset prioritizes vehicular network security and highlights the significance of certain datasets in research related to IoV. Studies emphasize the significance of accurately replicating actual automotive attacks by utilizing numerous CAN bus signals [75,77]. Our research indicates that datasets designed specifically for automotive networks are highly helpful for the development of IDSs that can effectively protect against threats unique to autos. An important practical consequence is the potential for IDS systems that are more targeted and effective in dealing with the specific difficulties of IoV.