Abstract

The widespread availability of mobile devices has led to the emergence of multiple gamified web and mobile applications for online assessment of students during classes. Their common weak side is that they focus mostly on positive reinforcement, without exploiting the pedagogical potential of loss and failure experience; thus, they are far from an actual game-like experience. In this paper, we present Gamitest, a course-subject-agnostic web application for student assessment that features an original game-like scheme to improve students’ perception of engagement and fun, as well as to reduce their examination stress. The results of the survey-based evaluation of the tool indicate that its design goals have been met and allow us to recommend it for consideration in various forms of student assessment, as well as provide grounds for future work on analyzing the tool’s effects on learning.

1. Introduction

While the connection between games and education was strong in the ancient world [1], the two diverged markedly in the modern times of compulsory education. The latter effectively served the needs of societies in the age of industry, but the age of information calls for educational solutions of a different character [2]. Following the call attributed to Johan Huizinga (“Let my playing be my learning, and my learning be my playing” ([1], p. 1)), there is considerable interest in closing the gap between games and education. This interest is grounded in merits: Mayo, who elaborates on the educational advantages of video games, gives several reasons advocating for her stance, one of which is the games’ compatibility with the effective learning paradigms: experiential learning, inquiry-based learning, self-efficacy, goal setting, cooperation, continuous feedback, tailored instruction, and cognitive modeling [3]. Consequently, game-based learning has been introduced to mainstream education at its various levels, including the preschool [4], primary [5], secondary [6], vocational [7], and higher education levels [8].

While game-based learning uses full-fledged games as educational tools, since around 2010, another way of exploiting games in education has risen in popularity [9]: gamification, which makes use only of selected game design elements, implemented in real-world contexts for non-gaming purposes [10]. Despite being less immersive, gamification is useful whenever full-fledged games are unsuitable for formal, technical, or sociological reasons; while it is always challenging to develop an educational game that, at the same time, would be effective in achieving the envisaged learning objectives, would adhere to contemporary technical standards and aesthetic norms, and would appeal to its intended users such that they would be willing to play, a gamification layer can be easily added to almost any educational application. However, a shallow form of gamification, often confined to the triad of just three elements of game design (points, badges, and leaderboards) and thus called pointsification [11], is criticized for “misrepresenting games” and usually focusing only on positive reinforcement, “leaving out the pain and loss of failure”, without which “the emotional thrill of gaming is lost” ([12], p. 3). The opposite of pointsification is meaningful gamification, in which gameful and playful layers are used to “help a user find personal connections that motivate engagement with a specific context for long-term change” ([13], p. 1).

In this paper, we describe an application of meaningful gamification in the form of an educational tool for online assessment—which is most often a target of shallow gamification. Before we describe the tool, including its concept, software implementation, and user interface for both students and teachers (in Section 3), we present a short review of related work on gamified tools for online assessment (in Section 2). The tool was subject to evaluation by students, and the results are presented in Section 4; the final section concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Gamified online assessment tools have received some interest from the scientific community. Table 1 lists the seven gamified online assessment tools covered by the identified relevant literature. Note that it only includes tools for an online assessment regardless of the teaching subject—tools designed for online assessment of specific subjects only, e.g., computer programming [14], are not included.

Table 1.

Existing gamified tools for online assessment.

Several works confirm the suitability of gamified student response systems for supporting education in various subjects (e.g., English language [15,24], political science [23], finance and international trade [17], biology [28], and history [27]) and in various educational contexts (e.g., offline in-class education [25,26] and online teaching [28]), as well as helping to implement specific teaching strategies (e.g., engaging discussion [22]). One work reports “significantly higher student motivation, enjoyment, and encouragement to collaborate” in comparison to a non-gamified student response system [21]; another one reports mixed results with regard to learning effects, finding one tool to improve and another to impair students’ academic achievement [16]. In three works, the functionality of available gamified student response systems is compared (two systems in [18], four in [19], and five in [20]) to suggest the most functional gamified tool for student assessment. All tools listed in Table 1 are primarily student response systems, but they are also capable of being run outside of the classroom (hence, useful for various forms of assessment). The set of applied gamification elements with which they are enriched varies between tools; however, we can find the following six elements in all of them (note that, herein, we follow the nomenclature for gamification elements proposed by Marczewski [29]):

- Challenges—consisting in questions to be answered.

- Curiosity—as the questions are revealed one by one, and the right answers are revealed only after the last student has answered or the time has passed.

- Time Pressure—as the questions must be answered in a limited time, and among the right answers, the better is the one given first.

- Points—as the right answers are rewarded with points.

- Competition—as the students try to provide the right answers for the most questions in the shortest time.

- Leaderboards—showing how well each player fares compared to others.

Usually, the players are shown on the leaderboard under their pseudonyms (thus implementing the Anonymity gamification element), but if these reveal their true identities, then the Social Status gamification element is implemented instead. Most tools also implement Avatars (representing players with images instead of just names; note that this gamification element does not belong to Marczewski’s directory [29] but, e.g., to Werbach and Hunter’s [30]).

Although there are other gamification elements implemented in some of the tools, all their gamification schemes are mostly focused on promises of rewards rather than risk and experience of failure. Gerber calls such an approach “the biggest miss in the current gamification trend” because it overlooks “the importance of players’ meta-awareness for failure”, requiring them “to reflect on why something did not work the first time and then adjusting one’s practice to progress” ([31], p. 89). As observed by Cain and Piascik, in well-designed games, “failure is not only acceptable, it is expected”, allowing the learner to view failure “more as an opportunity for further learning” ([32], pp. 3–4). In the following section, we propose a new game-like online assessment form addressing this deficiency of existing solutions, and subsequently, a new examination information system featuring it is presented and evaluated.

3. Game-like Assessment System

3.1. The Concept

Although the Gamitest tool proposed here shares its purpose with the gamified tools for online assessment presented in Section 2, it has been developed following a different path: rather than augmenting a student response system with gamification elements, it was conceived from its very beginning as a game consisting in answering test questions. Its key concept is to base the gameplay on a fundamental game design element that can be found in most video games but is hardly ever used in gamification: a life meter for the player.

Students start the assessment with their life meter set to 100%. Like the tools described in Section 2, the assessment gives points to the player for every good answer, yet unlike them, it reduces the player’s life meter by a fixed amount for every wrong answer (by default, 15% of the initial life—not the current life). Whenever players do not answer before the time passes (in 60 s by default) or they select the “I don’t know” option, their life meter is reduced by a smaller amount (by default, 10% of the initial life). The assessment is over when the player’s life meter drops to 0%. The final grade (deciding if the test has been passed or failed) depends on the number of points collected up to this moment (though not directly; this will be described later with a finer grain of detail). The other way of finishing the assessment is by staying alive until the last question has been answered. Note that in contrast to the other tools, where motivation is mostly based on the anticipation of rewards (points, top ranking, etc.) awarded for right answers, this tool also exploits fear-based motivation, with the players being afraid of losing their in-game life and losing the game for wrong answers, which should induce more engagement and thus help students stay focused on the test.

Like video games, the Gamitest tool provides instant feedback, showing a success/failure message along with the current player status after each answer. Attached to the presented messages are corresponding images evoking emotions, both positive (displayed at the beginning of the assessment, after every good answer, and at the end of the assessment if the student has passed) and negative (displayed after every wrong answer and at the end of the assessment if the student has failed). Unlike video games, as the tool can also be used in the classroom where silence is needed to not disturb other students, as there are no relevant sound effects or music scores attached to the respective displayed images.

In order to extend the students’ range of possible activity beyond answering the question, there are two additional actions, each of which can be used just once in one test: option check (which verifies whether the currently selected option is right or wrong) and time extension (which gives more time to answer the current question, an extra 45 s by default). This helps students deal with the most difficult questions while, at the same time, allowing them to make some strategic decisions (whether to perform a specific action on the current question or keep it expecting an even harder question to come later).

As mentioned earlier, the final grade on the test only indirectly depends on the gathered points, as it depends directly on the level attained by the student. As the students progress with the number of collected points, their level rises. There are three levels in the game. Players begin at level 1, which means failure if they remain at this level at the end of the assessment. The player progresses to level 2 after having correctly answered the seventh question—if, for the sake of simplicity, we ignore the time-outs, considering that seven wrong answers are needed to zero the player’s life meter, this means that the minimum number of questions that the player must answer to pass the test is fourteen, with the ratio of good answers being 50%. Level 2 guarantees the student a passing grade. Once achieved, it cannot degrade back to level 1. The player attains the top level (3) after correctly answering 10 questions at level 2. Level 3 guarantees the student a good grade. If, for the sake of simplicity of estimation, we ignore the time-outs and the “I don’t know” answers, the minimum number of questions that the player must answer correctly to achieve a good grade on the test is 24, with the ratio of good answers being 70%. Only students whose ratio of good answers reaches or surpasses 90% at the end of the test receive a very good grade. Note that the inability to fall below one’s attained level and the corresponding grade is meant to instill a feeling of self-worth and security in students and reduce their stress in the final section of the assessment.

The questions in the test are randomly chosen from a much larger question bank (a specific question can appear only once in one test). This introduces an element of randomness, allows replayability of the test, and, to some extent, prevents cheating in the classroom because the probability of two students sitting nearby receiving the same questions at the same time is very low.

The students are kept constantly informed about their status, including their current level, their life meter, the number of answered questions, and their score. Every question is displayed with a counter displaying the time remaining to pick an answer.

3.2. Software Implementation

The presented concept has been implemented in a dedicated examination information system consisting of three distinct parts serving the needs of various user types: students taking the assessment, teachers setting up the assessment and checking its results, and administrators managing the user accounts and databases.

The system has been developed as a web application, following the Model–View–Controller design pattern [33]. The application’s front end was developed in HTML5, CSS3, and JavaScript with the jQuery 3.7.1 and Bootstrap 5.2.3 libraries. To implement the server side, the Python 3.11 programming language with the Django 5.0.1 framework was chosen, taking into consideration its high stability and scalability; the availability of extension libraries for, purposes such as user authorization, caching, or even complete application components such as the administration panel; and its sustained popularity [34] and thus very good community support thanks to a very large user base.

PostgreSQL was been selected to store data on the server side, taking into consideration its superior performance (nine to thirteen times better than the alternative, MySQL, according to [35]) and the availability of advanced security mechanisms [36].

3.3. Student User Interface

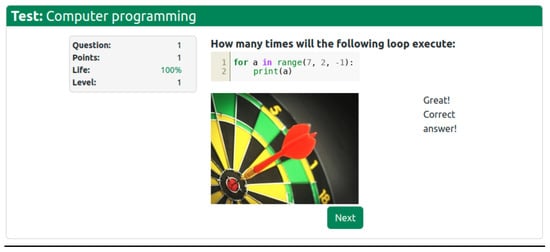

To participate in the test, the student follows an invitation link received from the teacher (see Section 3.4). The link leads to the test landing page (depicted in Figure 1), showing a motivating image (selected by the teacher, see Section 3.4) and a textual introduction to the test.

Figure 1.

Exemplary test landing page.

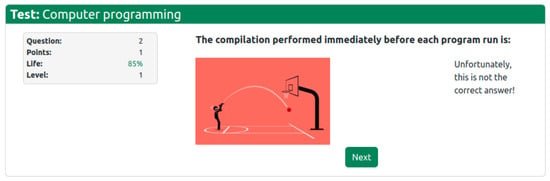

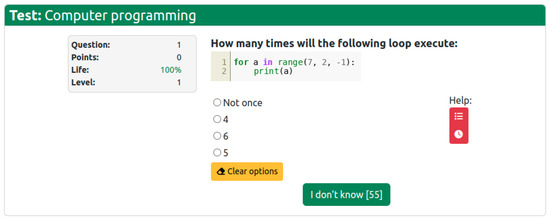

The test begins when the START button is clicked. At that moment, the first question page is presented (see Figure 2), which contains the following:

Figure 2.

Exemplary test question page.

- The title bar reminding the user what test is running;

- The status pane showing the question number, the student’s points accumulated so far, the student’s life meter, and the current level;

- The question content;

- The answer options, one of which is to be selected by the student;

- The buttons for invoking the additional actions of the option check and time extension (see Section 3.1);

- The answer approval button containing the counter for the remaining time (when the counter hits zero, the test moves on to the next question at the cost of the student losing 10% of their life); as shown in Figure 2, if no answer is selected, the button is labeled “I don’t know”, as it allows the student to skip the question at the cost of losing 10% of life instead of 15% for selecting a wrong answer.

After the student approves an answer (or when the time passes), the answer summary page is displayed. It may have one of two forms:

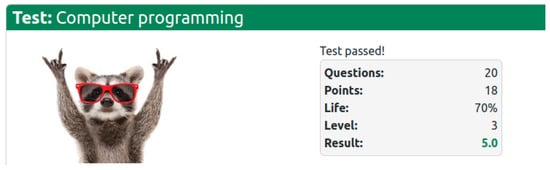

After the student has completed the test, the test summary page is displayed (see Figure 5) with either a positive (test passed) or negative (test not passed) message.

Figure 5.

Exemplary test summary page.

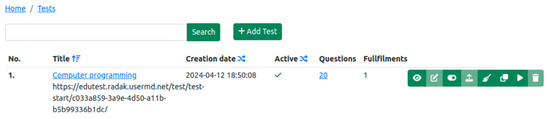

3.4. Teacher User Interface

The primary page of the teacher user interface, shown after logging in, displays the list of tests managed by the specific teacher, as presented in Figure 6. For each test, its title, URL, creation date, status (active/inactive), number of questions, and number of test completions are returned. The list can be filtered by any part of the test title and can be ordered in various ways (by test name, creation date, or active/inactive status). From this page, the teacher can add a new test and manage existing ones. The eight test management buttons (displayed next to each test’s meta-information) invoke the following functions (respectively, from left to right):

Figure 6.

Exemplary test list page for the teacher.

- View test completions;

- Edit the test (available only when the test is inactive and there are no test completions);

- Activate/deactivate the test;

- Import questions to the test (the questions should be specified in the Aiken format, a simple human-readable plain-text format for defining multiple-choice questions [37], with a small improvement that allows the specification of programming code described further in this section);

- Clear test completions (usually performed after test-running the test, it is a necessary step before modifying or deleting the test);

- Clone the test (so that a separate instance can be modified and run);

- Run the test (performed by the teacher, for the purpose of testing the test);

- Delete the test (available only when the test is inactive and there are no test completions).

There are two more test management functions available: the test settings view invoked by clicking on the specific test title (showing all test settings, e.g., messages and images displayed to the students) and the question list view invoked by clicking on the number of questions belonging to a specific test (showing the list of questions from which the test questions are randomly selected, along with answer options, with the right answer indicated).

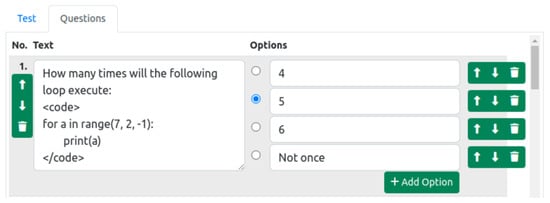

Creating or editing a test involves defining its general settings and questions. The general test settings include the messages and images displayed to the students in various situations and the reduction in the amount of life on the life meter after time-out (default: 10%). The question editor provides arrow buttons for switching between questions; a trashcan button for erasing the edited question; the main text field for editing the question content; and a user-set number of text fields for editing the answer options, which can also be reordered or erased (see Figure 7). Note the introduction of a <code> tag for the specification of programming code, so that it can be properly displayed to the student (with white-space preservation and syntax highlighting), a feature extending the Aiken format, whose original form is unsuitable for tests on computer programming, especially in languages such as Python, where indentation is semantically meaningful.

Figure 7.

Editing an exemplary test question.

There is also a third type of user interface implemented in the tool: the administrator’s, through which it is possible to manage the users and set their roles (teacher/student).

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation Setting and Procedure

To have the presented online assessment tool evaluated by students, a survey questionnaire was constructed, which included seven evaluation questions (see Table 2), six UI-related questions (designed to identify potential flaws with, e.g., the layout of visual controls, the color scheme, and the UI component sizing), one open-ended question allowing students to provide feedback for any aspect they considered worth improvement; and additional demographic and context-defining questions. The evaluation questions were prepared by the authors to assess students’ preference for the game-like test over classic test forms considering four aspects important for educational gamification analysis (engagement, fun, stress, and ease) and their willingness to use it in three different assessment cases (for self-testing, during classes, and in the final course examination).

Table 2.

Evaluation survey questions.

The survey was translated to the language of instruction (Polish) and implemented in Microsoft Forms. The message displayed on the test summary page included information about the survey and the link to start it; thus, the students who decided to respond did so immediately after their test completion. The survey participation was anonymous and voluntary. The survey was performed in April 2024 on students attending two courses, namely, computer programming (four groups) and software testing (two groups), at the University of Szczecin in Szczecin, Poland. All students in each group were first asked to take a test containing questions on their respective course subjects. Note that every student could take part in the assessment only once—the reasons were twofold: we considered the single exposure to Gamitest sufficient for the students to answer the survey questions, and we have not prepared enough questions to ensure the replayability of successive test attempts. Nonetheless, we are aware that this did not allow the full benefits of learning by failure to materialize as would be the case if multiple test attempts were allowed.

Altogether, the responses of 77 students were collected, including 56 males and 21 females.

4.2. Evaluation Results and Their Discussion

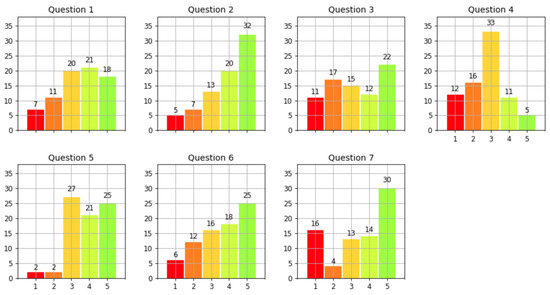

The histograms of responses to the general evaluation questions (listed in the first seven rows of Table 2) are presented in Figure 8. As can be observed, among the primary evaluation questions (the first three), the respondents reacted most positively to question 2—which received 68% of indications in the top range of 4 to 5, with the net difference between the shares of positive and negative answers being 52 percentage points (pp). This means most students did perceive the gamified assessment as more fun than a classic test (on paper or in Moodle). The second best was the reaction to question 1, with 51% positive indications and a net difference of 27 pp, meaning that the tool helped most students to become more engaged than they would be with a classic test. These two answers combined indicate that the goal for which the tool was developed has been attained.

Figure 8.

Histograms of responses to the general evaluation questions.

Students who perceived the gamified assessment as less stressful than a classic test (44%) outnumbered those who thought otherwise, though the margin was not large (net difference of 8 pp) (question 3). Regarding the students’ perception of difficulty (question 4), only 21% of the respondents considered it easier than a classic test, whereas 16 pp more of them thought the opposite. This result may also be linked to the fact that in the classic forms of assessment with which the students were familiar, only the total test time was limited, and the students could return to questions skipped earlier, which was not the case in Gamitest.

As for the envisaged use of the tool, the majority of the surveyed students (60%, with only 5% declaring the opposite) would like to be able to use the tool on their own (i.e., for formative assessment) (question 5), while similar shares of the respondents would like to use the tool to take tests during classes (56%) and for the final examination (57%); the shares of respondents declaring the opposite were more notable in this case (24% and 26%, respectively) (questions 6–7).

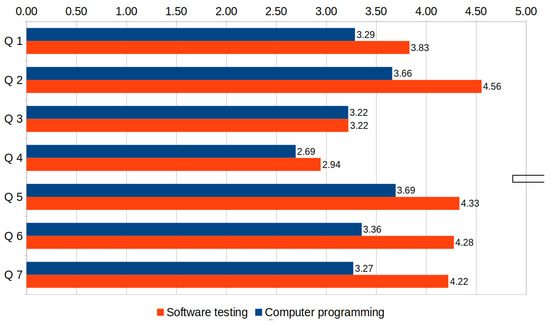

In Figure 9, the results obtained from the students attending different courses are compared, revealing that the computer programming (first-year course) group gave notably lower evaluations than the software testing (third-year course) group on all questions except question 3. A probable cause of this discrepancy in results could be that many questions in the programming test required understanding a snippet of code, which requires time for beginner programmers, and excessively fast time-out was indicated in open-text answers to question 14 by several programming students but none of the software testing students. This indicates the importance of a fair setting of question time-out considering the students’ fluency in answering the specific types of questions used in the test. Nonetheless, the intended purpose of the time-out is to help distinguish the very good students from the merely good ones, which obviously is not something that the latter would appreciate.

Figure 9.

Survey results by student course.

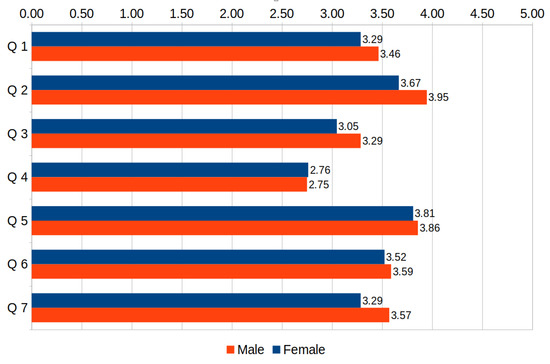

No large differences were observed between genders (see Figure 10). The largest one (still below 10%) regarded the fun factor (question 2), more often appreciated by males.

Figure 10.

Survey results by student gender.

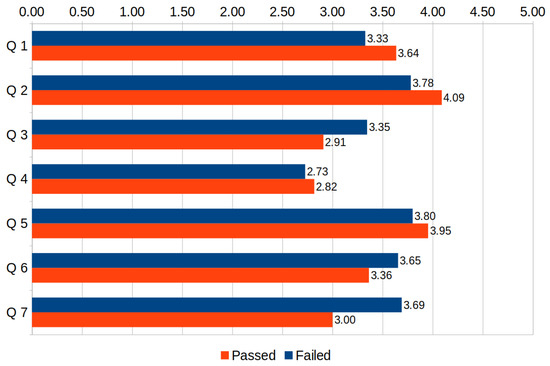

The differences between students who passed the test and those who failed the test were slightly higher but still small (see Figure 11). The largest one regarded question 7 and is not obvious to explain, as it was those who failed the test who more often accepted it as a form for the final examination. We can speculate that the students who fared well could expect to attain even better scores if there were no time limits for individual questions, whereas the time limit is not such a problem for students who have no clue what the answer is.

Figure 11.

Survey results by student assessment outcome.

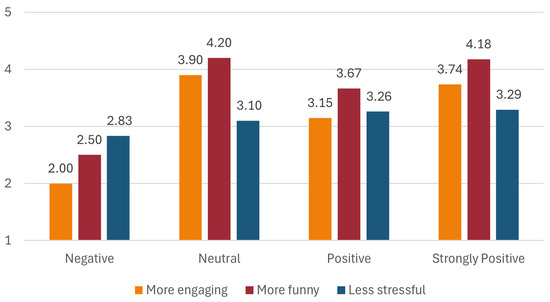

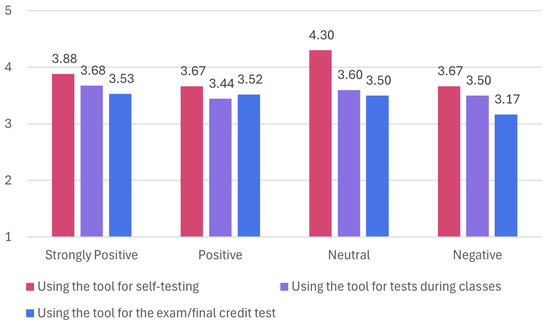

Over 79% of the respondents expressed a positive or strongly positive attitude toward video games, with only 8% expressing a negative attitude (no one expressed a strongly negative attitude). In Figure 12, we show the differences in average answers to the three main evaluation questions between the students who declared various attitudes to video games. As can be observed therein, those students who did not like video games were the only group for which the average score was below neutral (3.0) for all three aspects in which the proposed tool was compared to the classic test (more engaging, more fun, and less stressful). Interestingly, the highest averages with regard to engagement and fun were recorded among the students expressing a neutral attitude to video games, closely followed by video game fans. These results indicate that the student’s attitude toward video games is a factor affecting the perceived benefits of performing assessments using Gamitest.

Figure 12.

Perception of Gamitest vs. classic tests depending on students’ attitude toward video games.

Does the lack of benefits of performing assessments using Gamitest perceived by students with a negative attitude toward video games mean that the tool should not be used to test the knowledge of such students? The answer is no—as can be observed in Figure 13, even those students accepted the use of Gamitest for self-testing and tests during classes to approximately the same extent as the students having a more positive attitude to video games, and while they had notably lower acceptance for using it in the final examination, their average answer (3.17) was still above neutral (3.0).

Figure 13.

Willingness to use Gamitest depending on students’ attitude toward video games.

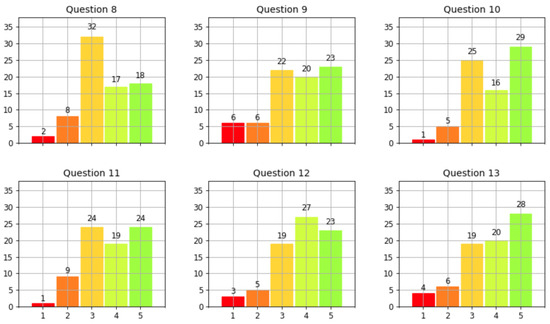

The responses to the user interface evaluation questions (8–13, see Figure 14) were mostly in the top range, with the lowest net difference measured for the layout (32 pp) and the highest for the size of displayed images. Although positive, these results indicate that there is room for improvement with regard to the Gamitest UI, especially concerning the positioning of visual components.

Figure 14.

Histograms of responses to the UI evaluation questions.

5. Conclusions

Gamification is a flexible tool for bridging games and education. Online assessment is a convenient point for implementing gamification; however, the existing solutions implement it in a somewhat shallow form, based on a stiff selection of gamification mechanisms and focusing mostly on positive reinforcement, without the feeling of loss and failure, and thus far from an actual game-like experience. In this paper, we strive to address this gap by proposing a game-like online assessment tool and evaluating its prototype implementation.

Even though the presented game-like assessment capitalizes on the students’ fear of failure, most of those surveyed found it to be not only more engaging and more fun but also, though to a lesser extent, less stressful than a classic test (i.e., performed in Moodle or on paper). Most students would like to be assessed with the tool, even for important examinations.

The study shares its limitations with other survey-based research based on non-representative samples, having reduced generalizability and reproducibility. Being based on students’ self-reporting, it is prone to subjective bias. A factor that could have positively impacted the results was that university students attending computer programming and software testing courses have a high level of digital literacy, which may not be the case in courses from other areas.

Our future work is twofold. First, we would like to correct the tool’s imperfections revealed in the survey and re-evaluate it on a larger scale, including students attending courses from various areas. Second, we would like to investigate the effect of using the tool in formative assessment on students’ learning in the long term, especially in comparison to the other existing gamified assessment tools.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.S.; methodology, J.S.; software, A.K.; validation, A.K.; formal analysis, A.K.; investigation, J.S.; resources, A.K.; data curation, A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.S.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and J.S.; visualization, A.K.; supervision, J.S.; project administration, J.S.; funding acquisition, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The presented work was co-financed by the Minister of Science of Poland under the Regional Excellence Initiative program.

Informed Consent Statement

The students took part in the survey voluntarily and were informed that their responses could be used for analytical and research purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized data used in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Botturi, L.; Loh, C.S. Once upon a game: Rediscovering the roots of games in education. In Games: Purpose and Potential in Education; Miller, C.T., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, E.A. The Age of Information and the Future of Education. J. Epsil. Tau 1980, 6, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo, M.J. Games for science and engineering education. Commun. ACM 2007, 50, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnamnia, N.; Kamsin, A.; Ismail, M.A.B.; Hayati, S.A. A review of using digital game-based learning for preschoolers. J. Comput. Educ. 2023, 10, 603–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Videnovik, M.; Madevska Bogdanova, A.; Trajkovik, V. Game-based learning approach in computer science in primary education: A systematic review. Entertain. Comput. 2024, 48, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L. Teachers’ perceptions of implementing Digital Game-Based Learning in the classroom: A convergent mixed method study. Ital. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 31, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahalan, F.; Alias, N.; Shaharom, M.S.N. Gamification and Game Based Learning for Vocational Education and Training: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 1279–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, D.; Skulmoski, G.J.; Fisher, D.P.; Mehrotra, V.; Lim, I.; Lang, A.; Keogh, J.W.L. Drivers and barriers to the utilisation of gamification and game-based learning in universities: A systematic review of educators’ perspectives. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2023, 54, 1748–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swacha, J. State of Research on Gamification in Education: A Bibliometric Survey. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sailer, M.; Hense, J.U.; Mayr, S.K.; Mandl, H. How gamification motivates: An experimental study of the effects of specific game design elements on psychological need satisfaction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, M. Can’t Play, Won’t Play. 2010. Available online: https://kotaku.com/cant-play-wont-play-5686393 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Hellberg, A.S.; Moll, J. A point with pointsification? Clarifying and separating pointsification from gamification in education. Front. Educ. 2023, 8, 1212994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S. A recipe for meaningful gamification. In Gamification in Education and Business; Reiners, T., Wood, L.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, N.L.; Lai, L.C.; Tseng, W.H. Design of an Online Programming Platform and a Study on Learners’ Testing Ability. Electronics 2023, 12, 4596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España-Delgado, J.A. Kahoot, Quizizz, and Quizalize in the English Class and their Impact on Motivation. HOW 2023, 30, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan Göksün, D.; Gürsoy, G. Comparing success and engagement in gamified learning experiences via Kahoot and Quizizz. Comput. Educ. 2019, 135, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetin, E.; Solmaz, E. Ask-Response-Play-Learn: Students’ views on gamification based interactive response systems. J. Educ. Instr. Stud. World 2017, 7, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, A.; Rudolph, J. A review of Quizizz—A gamified student response system. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2022, 5, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srimathi, S.; Anitha, D. A Multi Criteria Decision Making approach to integrate Gamification in Education. J. Eng. Educ. Transform. 2024, 37, 262–270. [Google Scholar]

- Muszynska, K.; Swacha, J. Selection of student response system for gamification at the higher education level. In Proceedings of the ICERI2019 Proceedings, Seville, Spain, 11–13 November 2019; pp. 10449–10455. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P.M.; Saucerman, J.J. Enhancing learning and engagement through gamification of student response systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, OH, USA, 24–28 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vallely, K.S.A.; Gibson, P. Effectively Engaging Students on their Devices with the use of Mentimeter. Compass J. Learn. Teach. 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Mayhew, E. No Longer a Silent Partner: How Mentimeter Can Enhance Teaching and Learning Within Political Science. J. Political Sci. Educ. 2019, 15, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslimin, A.I.; Ivone, F.M. Exploring Game-Based Language Learning Applications: A Comparative Review of Quizwhizzer, Oodlu, Quizalize, and Bamboozle. iTELL J. 2024, 1, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, T.A.; Nale, D.D.; Brown, K.T. Student response system best practices for engineering as implemented in Plickers. In Proceedings of the 2021 ASEE Virtual Annual Conference Content Access, Virtual, 26–29 July 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kappers, W.M.; Cutler, S.L. Poll Everywhere! Even in the classroom: An investigation into the impact of using PollEverwhere in a large-lecture classroom. Comput. Educ. J. 2015, 6, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Warnich, P.; Gordon, C. The integration of cell phone technology and poll everywhere as teaching and learning tools into the school History classroom. Yesterday Today 2015, 13, 40–66. [Google Scholar]

- Odeh, H.; Kaddumi, E.G.; Salameh, M.A.; Al Khader, A. Interactive Online Practical Histology Using the Poll Everywhere Audience Response System: An Experience During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Morphol. 2022, 40, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marczewski, A. 52 Gamification Mechanics and Elements. 2015. Available online: https://www.gamified.uk/user-types/gamification-mechanics-elements/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Werbach, K.; Hunter, D. For the Win: How Game Thinking can Revolutionize Your Business; Wharton Digital Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, H.R. Soft (a) ware in the English classroom: How gamification misses the mark: Playing through failure. Engl. J. 2017, 106, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, J.; Piascik, P. Are serious games a good strategy for pharmacy education? Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2015, 79, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Necula, S. Exploring The Model-View-Controller (MVC) Architecture: A Broad Analysis of Market and Technological Applications. Preprints 2024, 2024041860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swacha, J.; Kulpa, A. Evolution of Popularity and Multiaspectual Comparison of Widely Used Web Development Frameworks. Electronics 2023, 12, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, S.V.; Ouda, A. A Performance Benchmark for the PostgreSQL and MySQL Databases. Future Internet 2024, 16, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pina, E.; Ramos, J.; Jorge, H.; Váz, P.; Silva, J.; Wanzeller, C.; Abbasi, M.; Martins, P. Data Privacy and Ethical Considerations in Database Management. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2024, 4, 494–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken Format. 2022. Available online: https://docs.moodle.org/403/en/Aiken_format (accessed on 21 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).