Abstract

This paper explores the application of mobile sensor networks in cow herds, focusing on the challenge of achieving local communication under minimal computational constraints such as restricted locality, limited memory, and implicit coordination. To address this, we propose a high connectivity based sensor network scheme that enables individual sensors to self-organize and dynamically adapt to topological variations caused by cow movements. In this scheme, each sensor acquires local distribution data from neighboring sensors, identifies those with high connectivity, and forms a local network with a star topology. The overlap of these local networks results in a globally interconnected mesh topology. Furthermore, information exchanged through broadcasting and overhearing allows each sensor to incrementally update and adapt to dynamic changes in its local network. To validate the proposed scheme, a custom wireless sensor tag was developed and mounted on the necks of individual cows for experimental testing. Furthermore, large-scale simulations were performed to evaluate performance in herd environments. Both experimental and simulation results confirmed that the scheme effectively maintains network coverage and connectivity under dynamic herd conditions.

1. Introduction

Recently, the adoption of ICT and IoT technologies [1,2,3] in the livestock industry has been promoted to improve operational efficiency and reduce labor demands. Commercial devices, including estrus detectors [4,5], birth monitors [6], and feeding robots [7,8], are increasingly employed in beef cattle production, replacing traditional manual tasks. Early detection of illness or stress in cows is considered feasible through behavioral analysis aimed at identifying abnormal patterns.

Various approaches have been explored to monitor and identify abnormal behaviors in cows [9,10]. Behavior analysis using a single sensor has been explored through several approaches such as attaching triaxial accelerometers and magnetometers to cows to monitor movements [11,12,13] or installing communication sensors in cowsheds to infer behavior from radio signal strength [14,15,16]. Other approaches include using depth cameras to monitor calving [17,18] and microcontrollers to track heart rate and body temperature [19,20]. Additionally, management systems have been proposed for large-scale environments, such as pastures, by implementing dedicated communication infrastructures. Examples include systems that detect estrus cycles using communication sensors to form behavior-monitoring networks [21,22], as well as methods for managing pasture areas by analyzing the movement patterns of GPS-equipped grazing cows [23,24]. Based on these studies, communication-enabled sensors can be deployed to implement management systems in large-scale environments such as pastures. Despite their innovative contributions, most existing monitoring approaches have primarily focused on individual cow behavior, with limited exploration of interactions and social relationships within the herd. Furthermore, the specific types of information necessary for mechanistic visualization of interactions among the cows remain poorly defined. To facilitate understanding of these approaches, Table 1 provides a summary. Unfortunately, few studies have investigated stress assessment based on social interactions [25,26], such as mutual licking, or examined behavior at the group level.

Table 1.

Comparison of representative cow monitoring approaches.

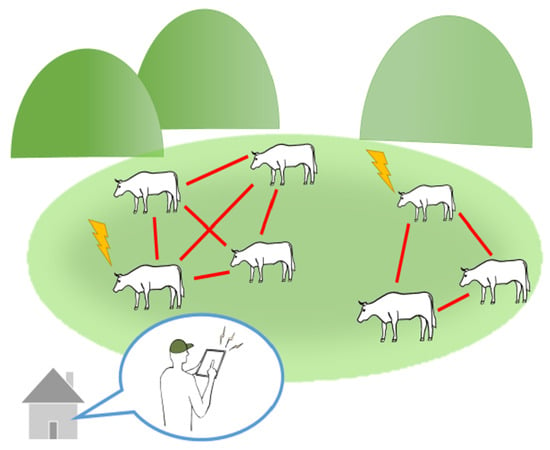

To address these limitations, this study proposes a communicative interaction scheme for visualizing interactions among cows in a freely grazing herd as illustrated in Figure 1. Specifically, we devise a sensor network based on mutual communication among cows using mounted wireless sensors, leveraging radio signal strength to enable both individual identification and group behavior analysis in grazing environments. To achieve this, we address two main challenges: an engineering challenge, involving the configuration of a sensor-based communication network, and an agricultural challenge, involving the analysis of social relationships among cows [25,26]. To tackle the engineering challenge, sensors are attached to each cow, and they are identified based on high-degree connectivity with nearby cows, enabling the generation of local networks. To cope with the agricultural challenge, a friend network is established by limiting the communication range to emphasize relationships between cows that interact more frequently. The overall network is subsequently formed by overlaying the local and friend networks. This facilitated the development of a behavioral model capable of monitoring dominance hierarchies and health conditions within the herd, enabling the detection of social dynamics and abnormal behaviors. The proposed scheme can help reduce labor demands and enhance overall productivity. Finally, to implement this concept in cows, we developed a neck-belt sensor tag and conducted evaluation experiments. Additionally, to assess the effectiveness of the proposed method in large-herd scenarios, we developed an in-house simulator and performed corresponding simulations.

Figure 1.

Concept of monitoring application to a herd of pastured cows.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 outlines our research problem and its definitions. Section 3 provides an explanation of the proposed solution. Section 4 details a custom neck-belt sensor tag. Section 5 shows the results from extensive experiments performed to evaluate the effectiveness and the performance of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 6 presents our conclusions.

2. Problem Statement

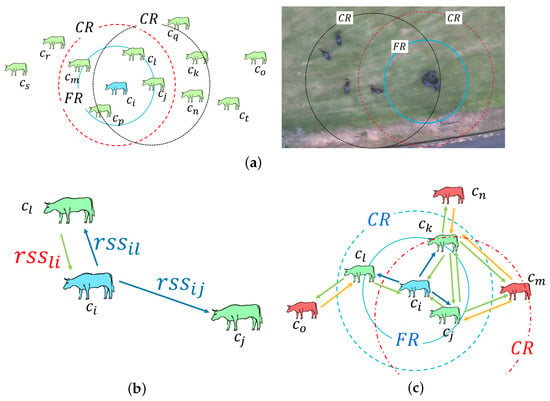

Figure 2a shows a herd of n cows equipped with a wireless sensor-tag device. First, the communication range of each cow is defined as , and it is assumed that the range of is constant for . Moreover, the inter-communications within are used to exchange information and to obtain the radio signal strength between the sensor-tag devices. Specifically, sends a message to a neighboring cow in , and receives information including the radio signal strength (Figure 2b). A specific range acquired is defined as . The range of is assumed to be constant for as in , namely is contained within . Although has its own initially, no specific roles such as leader, source, sink, and gateway are assigned. executes the same algorithm asynchronously but has no long-term state information.

Figure 2.

Definitions and notations. (a) herd distribution and communication boundary. (b) measured radio signal strength. (c) local communication based on . Here, the larger circle and the smaller circle represent the communication rang and the specific communication range , respectively. Moreover, each arrow indicates the direction of information flow.

We define as the state where can directly communicate with within . The set of cows within of is expressed as . refers to communication with cows outside via an intermediate cows. For example, in Figure 2c, if lies outside but is within of , then is a ’s cow of . The set of such cows is symbolized by . From , selects neighbors , forming the neighbor set . Furthermore, selects friends from based on , with the set defined as . The computation procedures for selecting and are described in the following section.

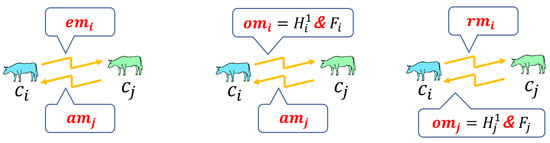

Figure 3 illustrates three message types used in the proposed scheme. These definitions are as follows: (1) the existence message , which is periodically broadcast by within and acknowledged by ; (2) the output message , which is sent to and acknowledged by ; and (3) the request message , which is sent to and elicits a response with . For simplicity, any message from is represented by . Next, a wait time is defined to evaluate connectivity. When broadcasts a message to , it measures the response interval . If receives a reply from within , then is considered to be within and is included in . Conversely, if no reply is received within , the connection is regarded as broken, indicating that has moved outside the range. Meanwhile, can also receive and/or overhear broadcast information from neighboring nodes.

Figure 3.

Three types of messages used for communication (from left: the existence message , middle: the output message , right: and the request message ).

The local network associated with is defined through its connections to . This yields a local graph , where is the set of vertices and is the set of undirected edges, excluding self-loops. The global herd network is then defined as . Next, based on , as illustrated in Figure 4, herd behavior is classified into four states: (mutual friends within ), (split into multiple local networks), (unified single network), and (isolated cow disconnected from the herd).

Figure 4.

Collective behaviors of cows. Here, the larger circle and the smaller circle represent the communication rang and the specific communication range , respectively. (a) mutual friend between and . (b) state due to isolated cow , where the red arrow indicates the change in the spatial distribution of cows from the left side to the right side.

Based on the definitions and assumptions above, this paper addresses the monitoring of herd behavior through local communication interactions in a cow herd. To solve this problem, we propose a monitoring algorithm that visualizes herd behaviors and inter-cow relationships using local network configurations and virtual distances. Specifically, selects and while forming through intercommunication within and . Herd behaviors and relationships are then inferred from , and by combining all , G is self-organized. Since G changes dynamically with herd movement, it requires partial modification, updating, and repair in response to behavioral changes. Details on the monitoring scheme are provided in Section 3.5.

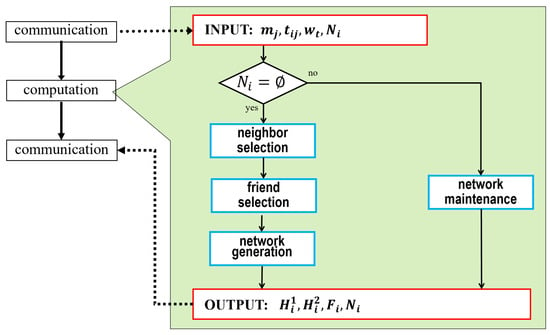

3. Monitoring Algorithm Based on Configuration

This section describes the monitoring algorithm for generating and maintaining based on herd behaviors. As shown in Figure 5, the algorithm consists of four functions: selection, selection, generation, and maintenance. Four of these functions are explained in this section. Based on this algorithm, the identification of herd behaviors is described in Section 3.5.

Figure 5.

Schematic flow of monitoring algorithm based on .

The algorithm takes , , and as inputs, and outputs , , , and . First, it checks whether is empty. If this is satisfied, and are selected, and is generated. If is not empty, the network maintenance is performed to accommodate changes in due to cow movements. Once has been generated or updated, a server system determines the herd behavior based on the resulting connection state. Finally, the outputs are broadcast to , and this process is repeated continuously.

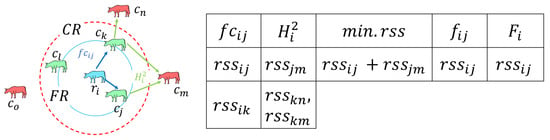

Next, we define the terms used in the algorithm. The union of all transmitted by is . The correspondence between and via intercommunication is . denotes a candidate friend in computed from . Information from to through is expressed as , and represents the minimum received signal strength. Information held by at time t is , with the previous time step defined as ; for simplicity, the time indices are omitted in subsequent explanations.

3.1. Selection

The first computation function selects and consists of two steps: information gathering from and neighbor searching.

3.1.1. Acquisition of Information

In the first step, receives from . It first checks whether is sent by and whether the response from occurs within . If both conditions are satisfied, is retained in and sends an updated . Using and within , calculates the state of beyond . For example, in Figure 6, , , and are within , and , , and are beyond . When connects to , , and , and obtains , a correspondence table is organized as mapping elements of (right side of Figure 6). From and , is calculated:

Figure 6.

Illustration of acquisition (left: cow distribution Here, the larger circle and the smaller circle represent the communication rang and the specific communication range , respectively. In addition, each arrow indicates the direction of information flow.; right: corresponding table ).

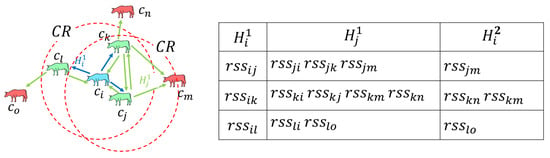

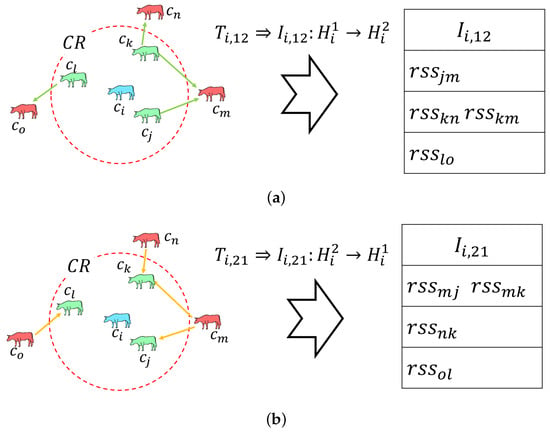

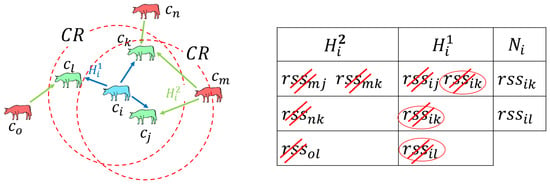

By calculating , estimates information about cows beyond its . The intercommunication correspondence between and is defined as and , respectively. Here represents connections from elements of to elements of as shown on the left in Figure 7a.

, also represented by , is shown on the right in Figure 7a. Conversely, represents connections from elements of to elements of as shown on the left in Figure 7b.

Similarly, is represented as as shown on the right in Figure 7b. The combination of and defines the connections from to via and is expressed:

By using the composition of and , can estimate the connection state of .

Figure 7.

and computation process. Here, the red circle represents the communication rang . Each arrow indicates the direction of information flow. Furthermore, the black hollow arrow represents the correspondence between the cow distribution (left) and the formulated table (right). (a) computation. (b) computation.

3.1.2. Calculation

The second step selects using and obtained from . First, identifies the element of with the highest number of to cows in , defined as , and selects it as the first neighbor . The corresponding elements in and are then removed. This process is repeated to select the second neighbor and subsequent neighbors, each time removing the corresponding elements, until is empty (the right side in Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Illustration of calculation (left: cow distribution, where the red circle represents the communication rang . Moreover, each arrow indicates the direction of information flow.; right: calculation table, where the double diagonal lines denote the eliminated terms, and the oval marks the terms retained in the final result.)

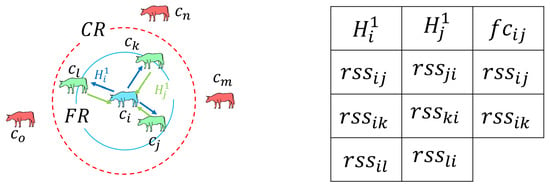

3.2. Selection

The second computation function, called friend sorting, selects and determines .

3.2.1. Calculation

The first step is to obtain from the information on as mentioned in Section 3.1.1. If both and are within the range (Section 2), the corresponding element of is selected as ; otherwise, is set to empty. Here, denotes of elements in . For example, if and are in ’s (see the left side of Figure 9), the step checks whether from to , and from both and to are mutually within . Elements satisfying this criterion (, ) are selected as (see the right of Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Illustration of calculation (left: cow distribution, where the larger circle and the smaller circle represent the communication rang and the specific communication range , respectively. In addition, each arrow indicates the direction of information flow.; right: calculation table).

3.2.2. Calculation

The second step is to extract from obtained in the previous step. To begin, the procedure checks whether is non-empty. If it is satisfied, is calculated under the condition .

Next, if the calculated is the minimum value, it is assigned to , and is computed accordingly.

Finally, the computed , as shown in Figure 10, is designated as the primary member of .

Figure 10.

Illustration of calculation (left: cow distribution, where the larger circle and the smaller circle represent the communication rang and the specific communication range , respectively. In addition, each arrow indicates the direction of information flow.; right: calculation table).

If , it assigns the minimum to , and computes as the primary element of .

If multiple values are equal, the corresponding are all designated as main members of .

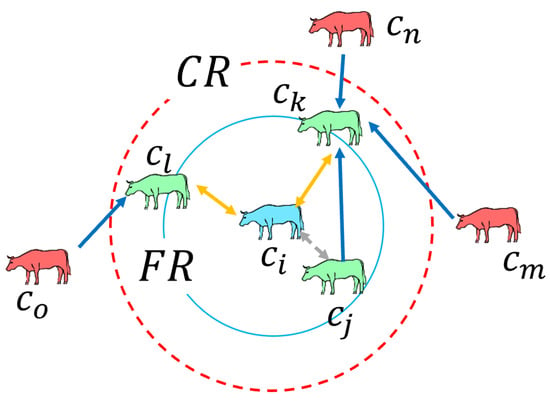

3.3. Generation

The third computation function generates . The input of is , and the output is . Vertices consist of and its selected , expressed as , forming the set . Each edge between and is defined as , and denotes the connection of . When is selected as , the corresponding local network of is generated. Specifically, since is connected to in through a -to- connection, as shown in Figure 11, this configuration can be regarded as a star network topology. Aggregating all enables complete self-organization of G. When individual overlap, the overall network forms a partially connected mesh topology (see Figure 12). After constructing , broadcasts and and exchanges this information with .

Figure 11.

Illustration of generation, where the larger circle and the smaller circle represent the communication rang and the specific communication range , respectively. In addition, each arrow indicates the direction of information flow.

Figure 12.

Illustration of G by collecting with star topologies. Here, each circle represents the communication rang . Moreover, individual arrows indicate the direction of information flow.

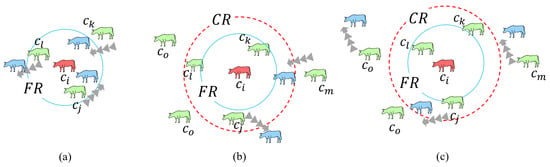

3.4. Maintenance

The fourth computation function in Figure 5, network maintenance, addresses changes caused by cow movements. These changes occur in three states: (1) only changes (Figure 13a), (2) only changes (Figure 13b), or (3) only changes (Figure 13c). This function consists of five steps: information acquisition, calculation, calculation, calculation, and reconfiguration.

Figure 13.

Variations in communication conditions with cow movements, where the larger circle and the smaller circle represent the communication rang and the specific communication range , respectively. (a) changes. (b) changes. (c) changes.

3.4.1. Information Acquisition

As the first step, the same information acquisition procedures described in Section 3.1.1 are carried out, with the following updates and corresponding assessments.

3.4.2. Calculation

In the second step, is recomputed as explained in Section 3.2.1. If both and the elements are within , the updated is selected as ; otherwise, remains unchanged.

3.4.3. Calculation

In the third step, using calculated in Section 3.2.2, when for the newly computed is non-empty, the elements of and are compared. Next, is calculated using Equation (5) when . If the resulting is minimal, it is assigned to . The new is then compared with the previous value; when it remains minimal, a new is computed using Equation (6) and becomes the member of . If is empty, the minimal is assigned to after compared with the previous value, and a new is used to update via Equation (7).

3.4.4. Calculation

The fourth step investigates described in Section 3.1.2, using and computed in Section 3.4.1. first selects the element of with the highest number of edges to cows in (Equation (3)) as the first neighbor. The corresponding elements in and are then removed. This process is repeated to select subsequent neighbors until is empty.

3.4.5. Reconfiguration

In the fifth step, is partially reconstructed using updated information, following the same procedure as the generation function. First, the cow’s state is determined based on its movement. When changes, the vertices of and newly selected are updated in . If changes, the connections between the new and members are recalculated using Equation (4). Similarly, variations in immediately trigger reconfiguration of its connections with . This partial reconfiguration maintains without requiring a full rebuild.

3.5. Determination of Herd Behavior Pattern

For the monitoring of herd behaviors as explained in Section 2 (Figure 4), the determination function for four types of group patterns is described. We first check whether is an empty set. If , the cow is classified as , indicating it is isolated from the herd. If , the herd is evaluated as a single herd. If all cows belong to a single network, the herd is classified as . If the network is disconnected, with multiple sub-networks, the herd is classified as . Finally, if cows within the herd are mutually within each other’s and maintain a state of mutual friendship, the herd is classified as .

4. Development and Operational Experiments of Wireless Sensor Tag Device

To identify herd patterns in cows, this section introduces a wireless sensor tag device (hereafter referred to as the “sensor tag”), which implements the monitoring algorithm described in Section 3.

4.1. Design Concept of Wireless Sensor Tag Device

The development process of the sensor tag is divided into three parts: the components, the frame of attaching the tag to each cow, and the monitoring system through a server receiver. These elements are required for the execution of the monitoring algorithm. First, the tag should support mutual communication with acquisition. Second, the tag should execute computations using the algorithm. Third, the tag should temporally store data received from other tags.

Next, from an installation standpoint, two key requirements should be met: battery-powered operation and protective housing. Battery operation is essential since external power cannot be used when the tag is attached to cows. The tag-housing frame protects the tag, and allows for attachment to a wearable neck belt. In addition, monitoring requires a server connection to confirm tag status and collect data.

4.2. Development of Wireless Sensor Tag Device

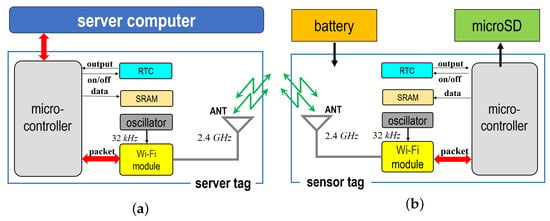

To realize the algorithm, as illustrated in Figure 14, we developed a server tag and a sensor tag consisting of two parts: an electronic module and a frame. Details are presented in the following subsections.

Figure 14.

Hardware configuration of a wireless sensor and a server tags. (a) server tag. (b) sensor tag.

4.2.1. Electronic Modules

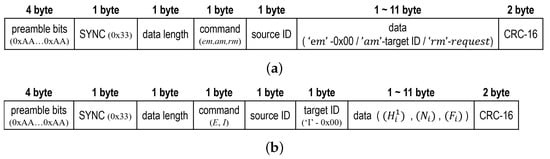

The electronic module comprises a communication unit and an arithmetic unit. First, for the communication unit, we use the ESP32-WROOM-32 microcontrollers (Espressif Systems, Shanghai, China). This module combines Wi-Fi and Bluetooth in a single unit and is suitable for wireless communication. Furthermore, the module contains a 32 kHz oscillator and a 2.4 GHz band antenna. The wireless standard used is Wi-Fi: 802.11 b/g/n. Figure 15 shows the structure of the packets used for communication. As shown in Figure 3, for communication, two packet types are established: length-fixed and length-varying, depending on the type of messages. The packet format shown in Figure 15a is used for , , and . On the other hand, Figure 15b illustrates the packet format used for broadcasting . Specifically, in the packet, data length refers to the length of the data, the command defines the action for each message, source is the sender’s , target is the recipient, and data carries the information for the command.

Figure 15.

Structure of packets used for communication. (a) length-fixed packet type. (b) length-varying packet type.

Second, the arithmetic unit uses an ESP32 microcontroller, a low-cost, low-power SoC with an Xtensa dual-core 32-bit LX6 processor (240 MHz, <600 DMIPS) and 520 KB SRAM. A micro SD card slot and a Real-Time Clock (RTC) module (SparkFun Electronics, Niwot, CO, USA) store the algorithm’s data along with transmission and reception timestamps.

Finally, is obtained via the tag’s Wi-Fi module. The module first scans the network to identify the number of tags within , after which an is assigned to each detected tag. The scanned values, including , are then logged to the micro-SD card.

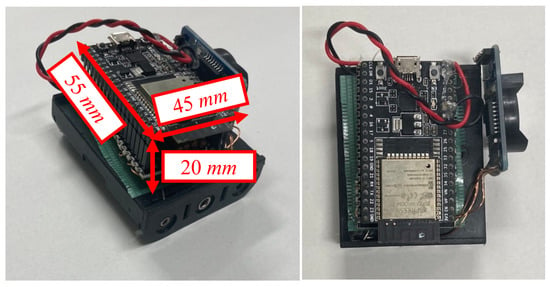

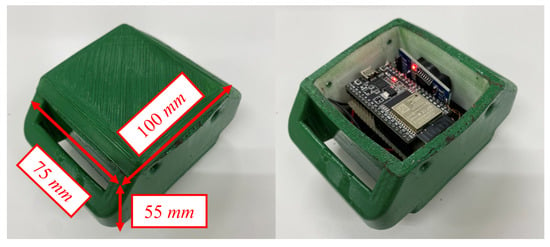

4.2.2. Frame Unit

The frame unit, powered by three AA batteries (4.5 V), houses the electronic module in a PLA resin case with a waterproof lid and neck-belt buckle. The module and batteries are arranged in a two-layer structure (Figure 16). Module size: 55 × 45 × 20 mm; frame size: 75 × 100 × 55 mm (including buckle). Figure 17 shows the assembled tag.

Figure 16.

Specification and layout of electronic module.

Figure 17.

Wireless sensor tag mounted on frame unit.

4.2.3. Monitoring Unit: Server System

As shown on the left-hand side of Figure 14, the monitoring device consists of a computer and an electronic module. The LG gram computer is an Intel(R) Core Ultra 7155H CPU with Microsoft Windows 11 Home. The Microsoft Visual Studio C++ 2022 environment of Visual Studio Code 1.107.0 was used for the algorithm. A module is attached to the computer to receive the tag information.

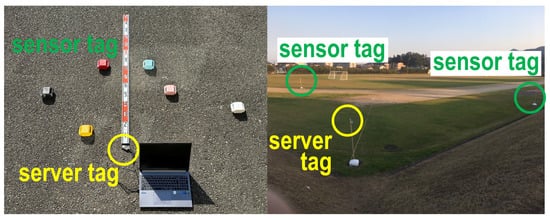

4.3. Preliminary Experiments for RSS Measurement and Network Generation

The signal strength of the developed tag decreases with distance. To determine the effective ranges of and based on distance-dependent signal attenuation, preliminary experiments were conducted using ten sensor tags and one server tag. The server tag was fixed in place, while the sensor tags were positioned at 10 cm intervals from 0 to 1 m and at 1 m intervals up to 50 m, respectively. As shown in Figure 18, two preliminary experiments were conducted: one in an indoor classroom, where measurements were taken at 10 cm intervals, and another in an outdoor training field, where measurements were taken at 1 m intervals.

Figure 18.

Illustration of experimental environments used for measuring signal strength.

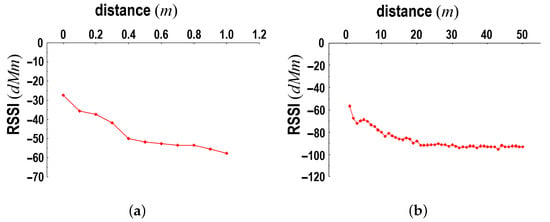

Figure 19 presents the measurement data where the left side depicts short-distance measurements (1 m range, 10 cm intervals), while the right side shows long-distance measurements (50 m range, 1 m intervals). At the short distance cases, signal strength decreased proportionally with distance from the server, whereas at the long-distance cases, it exhibited exponential attenuation. In particular, considering the body size of cows and their affiliative behaviors, a radius of 2 m was defined as the range. The corresponding measured at 2 m was dBm. In addition, although the gradually decreased up to 30 m, no further change was observed beyond 35 m; thus, this distance was defined as the radius of the range, with the measured at that point being dBm.

Figure 19.

Measurement results for variation in signal strength over distance. (a) 10 cm intervals up to 1 m. (b) 1 m intervals up to 50 m.

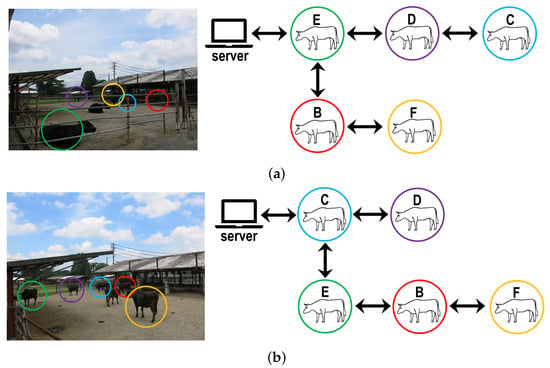

Additional experiments employing the developed tags were performed to examine intercommunication among cows and assess the connectivity between the cow-mounted sensors and the server system. As shown in Figure 20, the tags were attached to the necks of five cows housed in a free-barn with paddocks at the Miyazaki Prefectural Livestock Experiment Station. Under this experimental environment, we examined how a fixed server tag adapted its topology when five sensors were in motion. Individual left sides in Figure 21 indicate the distributions of five cows and the right sides are the states of the server’s local network configuration as time went on. The experimental results confirmed that the proposed algorithm effectively constructed a server-centered local network and enabled stable connections among the sensor tags attached to each cow. In addition, the proposed setup successfully regenerated the server-centered local network despite the movements of the tags attached to each cow.

Figure 20.

Experimental environment and sensor tag mounted on cows.

Figure 21.

Experimental results for network generation with respect to server system according to movements of five sensor tags. Here, for ease of identification during the experiments, five colored straps were attached to the cows’ necks. The tag IDs corresponding to each color are shown on the right. In addition, the bidirectional arrows indicate that information is exchanged in both directions. (a) 11:42:35 AM. (b) 13:14:08 PM.

5. Evaluation Results and Discussion

5.1. Experimental Results in Free-Barn with Paddocks

To verify whether the network configuration changes in response to cow movements, we conducted evaluation experiments and compared a portion of their movements with the corresponding network configuration. The experiments in this subsection were carried out in an open paddock with an attached free barn (20 × 15 m), which does not represent an enclosed metal structure. Although metal posts are present around the paddock area, their impact on radio propagation is considerably smaller than that of an indoor barn with reflective walls. This is since the paddock is open on all sides, the roof is elevated with large openings, and no continuous metal walls are present that could generate strong multi-path reflections.

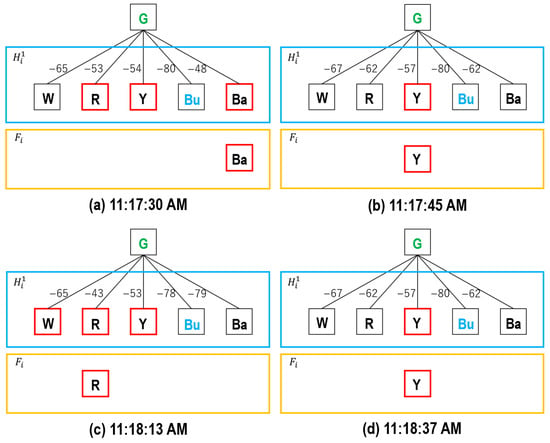

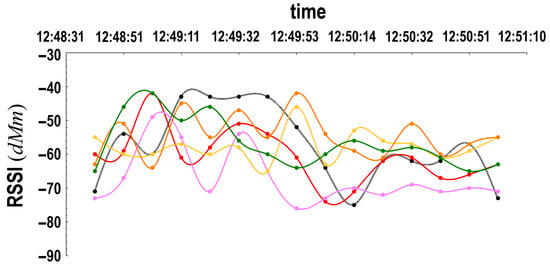

As the first experiment, to examine whether the network configuration responds to the movements of a specific cow, we conducted tests using six cows equipped with tags mounted on their necks. In Figure 22, the green-circled cow passes the yellow cow and moves toward the red cow. Figure 23 shows the corresponding network configuration and the variation in received signal strength during the herd behavior, taking the cow enclosed by the green circle as the reference. The rectangles highlighted in red indicate that the cows are in close proximity, which is defined as an RSSI value between −30 and −60 dBm. The results confirmed that the network configuration can be generated and dynamically adjusted according to the movements of specific cows. Furthermore, by comparing a portion of the herd behavior with the corresponding network configuration, we verified that the network structure changes in accordance with herd movements when using a particular cow as the reference point.

Figure 22.

Experimental scene for network configuration with respect to green circled cow.

Figure 23.

Experimental results for changes in network configuration according to movements of green-circled cow. Here, the characters G, W, R, Y, Bu, and Ba represent the colors green, white, red, yellow, blue, and black, respectively.

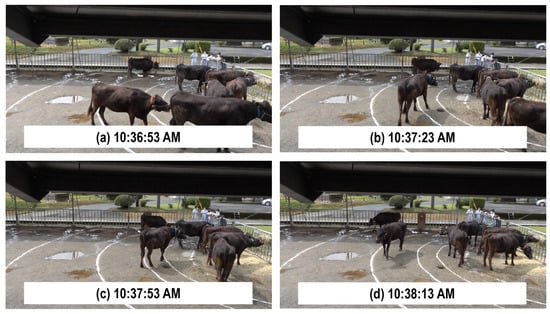

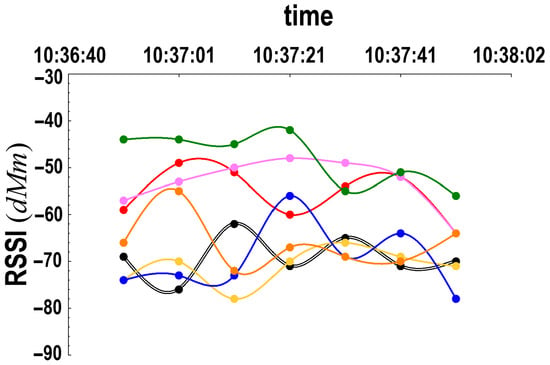

Next, a tag was installed as a server at predetermined locations within the paddock, while individual tags were mounted on the necks of seven cows to conduct two types of verification experiments. In the first setup, the server tag was placed in the feeder, and white lines were drawn on the ground at 1, 2, 3, 5, and 7 m intervals in a fan-shaped layout. Figure 24 and Figure 25 show the cow behaviors around the feeder and the variations in depending on distances, respectively. The results indicated that the cow wearing the green tag closest to the feeder exhibited the strongest signal. In other words, signal strength is inversely proportional to the distance from the feeder, as shown in Figure 25, where the green-tagged cow exhibits the strongest signal, confirming its closest proximity to the server tag.

Figure 24.

Experimental scene for network configuration observed when cows gathered at feeder.

Figure 25.

Distance-dependent variation in signal strength from feeder. Here, to facilitate identification during the experiments, seven colored straps were attached to the cows’ necks, and the values corresponding to each color are plotted.

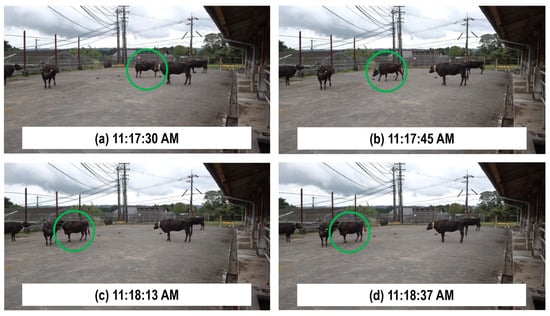

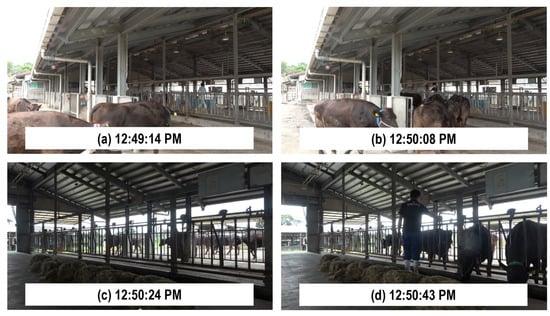

In the second setup, the server tag was placed at the cowshed entrance to measure changes in as cows entered. Figure 26 shows the scenes in which cows approached the server, and Figure 27 presents the corresponding variations in signal strength with respect to distance from the entrance. As expected, each sensor tag exhibited a higher RSSI value when passing by the server, enabling the identification of entry order. From these results, we conclude that the algorithm implemented on the developed tags can be used to monitor the frequency of visits to feeding and drinking areas and to infer dominance relationships within the herd.

Figure 26.

Experimental scene for network configuration observed when cows entered cowshed.

Figure 27.

Distance-dependent variation in signal strength from entrance. Here, to facilitate identification during the experiments, six colored straps were attached to the cows’ necks, and the values corresponding to each color are plotted.

5.2. Experimental Results in Grazing Field

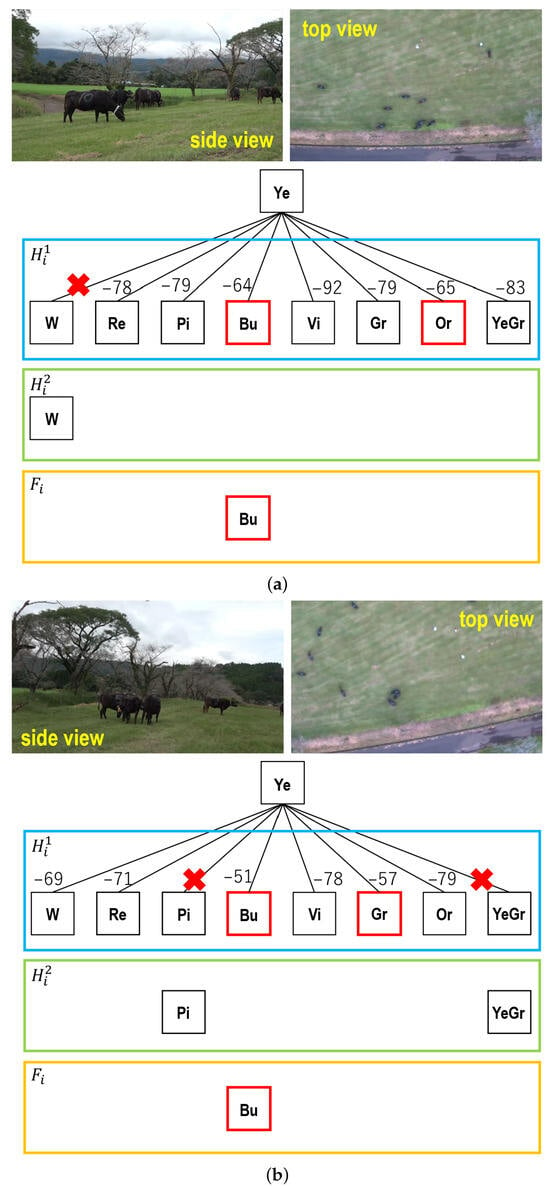

Field experiments were conducted in a grazing environment with tags attached to 10 cows in one pasture. Depending on hierarchy and signs of estrus, the cows sometimes clustered near specific individuals or split into subgroups. Figure 28 illustrates the network configuration during herd integration and division. In Figure 28a, when multiple herds merged, “friends” were selected from cows within the effective communication range defined in the basic experiments. In Figure 28b, when the herd split, the connection with was temporarily lost and then re-established, demonstrating that the network could dynamically generated and reconfigured connectivity.

Figure 28.

Experimental result for group behaviors of grazing cows and corresponding network configuration. Here, the abbreviations Ye, W, Re, Pi, Bu, Vi, Gr, Or, and YeGr denote the colors yellow, white, red, pink, blue, violet, green, orange, and yellow-green, respectively. Moreover, the red cross indicates a disconnection state. (a) 10:26:24 AM. (b) 11:09:36 AM.

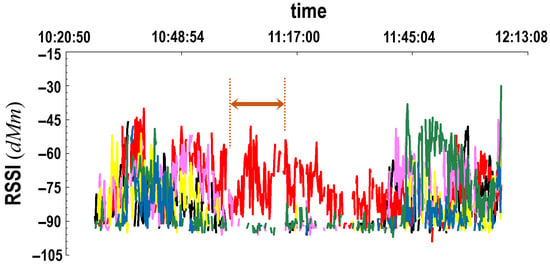

Figure 29 shows received by a tag attached to one cow when two cows separated from the herd. The signals from the cow moving with the herd were highlighted in red, with strong signals observed in specific periods. The periods marked by the brown arrow correspond to intervals of a licking behavior, an affiliative interaction. These results indicate that the network accurately reflected inter-cow distances both during affinity behaviors and when cows temporarily split from the herd.

Figure 29.

Variations in signal strength when two cows leaving herd.

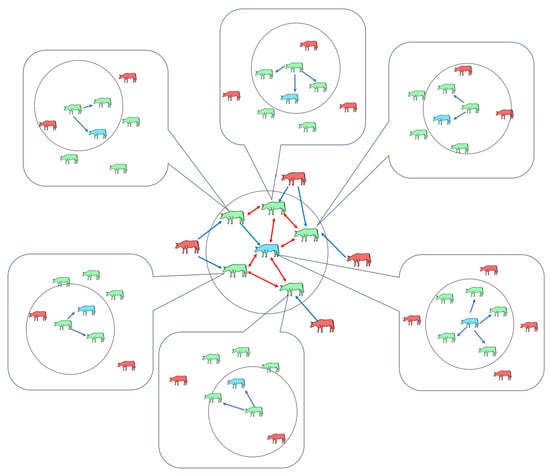

5.3. Simulation Results for Larger Number of Cow

In the pasture-field experiments, 10 cows were employed. To investigate the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm for the larger herds of cows, verification evaluations were conducted using our in-house network simulator. The simulator implemented in the Microsoft Visual C++ environment was used to model herd movements and depict neighbor–friend relationships graphically. In the simulation settings, has its own identifier, but no predefined roles such as leader, source, sink, or gateway are assigned. All independently execute the same algorithm without maintaining long-lived states and operate asynchronously with respect to other . Specifically, can broadcast its information to adjacent within its using an initially assigned unit in the simulation. Conversely, can receive and/or overhear broadcast information from neighboring nodes. Finally, it is assumed that communication occurs without noise or interference.

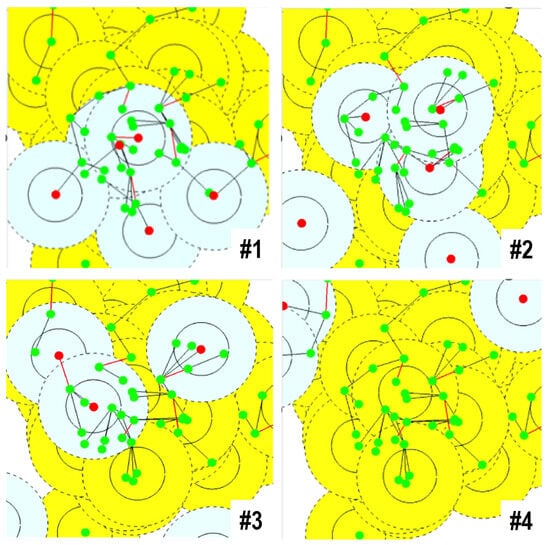

Simulation results for herds of 50 cows are shown in Figure 30. Light blue and yellow circles indicate the range of each cow, while black lines represent edges from to , namely . The thick red lines show neighbors selected as friends after network generation. , comprising many fixed cows and five moving cows, undergoes partial updates since the red cows move arbitrarily. In detail, five red cows move arbitrarily and simultaneously, causing topological changes in their generated , while the other cows remain stationary. Under the proposed algorithm, the cows partially updated , , , and through overhearing, and modified only the portions of corresponding to these changes, rather than regenerating the entire for all cows. The findings demonstrate that responds to local variations in relative positions through partial updates, rather than full reconfiguration. Consequently, we confirmed the self-organizing capability of the proposed algorithm in adapting to network dynamics.

Figure 30.

Simulation results for network reconfiguration according to movements of five cows. (#1) 5 sec. (#2) 25 sec. (#3) 45 sec. (#4) 65 sec.

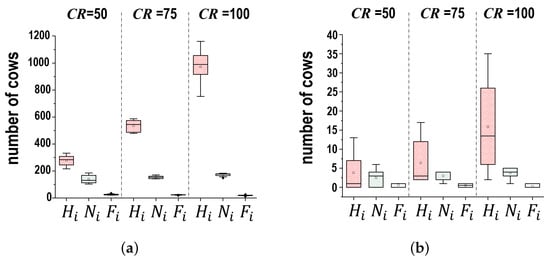

To evaluate the advantages of selection under the proposed algorithm, simulations of configuration were conducted while varying . The simulations employed 30 distinct initial distributions of 50 cows, with configured to 50, 75, and 100 units. After configuration in individual simulations, the numbers of cows in and for each cow were recorded and summed. Additionally, one cow was selected to compare its behavior with that of the entire 50-cow herd. The statistical results are shown in Figure 31, where error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals and boxes represent the 25–75% interquartile range. As expected from communication properties, the number of cows in increased with the expansion of . In contrast, the size of remained largely stable regardless of . Similarly, the selection exhibited a consistent trend regardless of . Consequently, these findings demonstrate that selection is robust to variations in , as each tag identifies neighbors with higher connectivity using local distribution information.

Figure 31.

Simulation results for the number of cows in , , and under varying values. (a) data for 50 cows. (b) Data for one cow selected from 50 cows.

5.4. Discussion

Based on the experimental findings, we confirmed that a local network can be formed using individual communication states, including the received signal strength from sensor tags attached to individual cows. By clarifying the relationship between these variables and signal strength, the network reconfiguration process could be characterized, linking the splitting and merging of grazing cows to corresponding network changes. This enabled the development of a behavioral model for monitoring dominance hierarchies and health conditions within the herd, allowing the detection of hierarchical dynamics, isolation due to injury, and other behavioral changes in grazing environments. The proposed approach has the potential to reduce labor burdens on farmers and improve overall productivity.

In practice, quickly identifying estrus, injuries, or other abnormalities in grazing cattle remains challenging. Missed estrus signs, in particular, can lead to failed artificial insemination and reduced productivity. As future work, we will analyze herd behavior in greater depth based on habitual patterns and hierarchical relationships, with the aim of visualizing inter-individual interactions and overall social structure.

We plan to develop algorithms capable of detecting support-required conditions such as illness or parturition using behavioral data. Incorporating not only basic behaviors (standing, lying, walking) but also mounting behavior, a key indicator of estrus, is expected to further enhance detection accuracy. The insights gained from this study may also be applicable to other herd-forming livestock species, contributing to more advanced behavioral monitoring and herd management technologies across diverse production systems.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we focused on the monitoring of herd patterns and inter-cow relationships by using relative-communication distances and neighbor-centered networks. We proposed a local network generation algorithm using a two-layer communication range, and validated it through extensive experiments with cows equipped with wireless sensor tags. The proposed algorithm enabled the configuration of star networks among selected neighbors, and by combining local networks, a global partially connected mesh network self-organized. By incorporating signal strength relative to distances, the network adapted to changes caused by cow movements. Field experiments demonstrated that the friend selection function reflects both affiliative interactions and social isolation in cows, whereas simulations confirmed the feasibility of generating and reconfiguring networks within large herds. The proposed algorithm allows monitoring of an affinity behavior and isolation status in grazing environments, potentially reducing labor for livestock management and improving productivity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L.; methodology, G.L., K.O. and F.S.; software, T.Y., K.O. and Y.K.; validation, G.L., F.S. and Y.K.; formal analysis, T.Y., K.O. and F.S.; investigation, G.L. and K.O.; resources, G.L. and F.S.; data curation, G.L. and Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.L. and K.O.; writing—review and editing, G.L., T.Y. and Y.K.; visualization, G.L. and T.Y.; supervision, G.L. and F.S.; project administration, G.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. and F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experiments were conducted in compliance with the protocol which was reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and approved by the President of the University of Miyazaki (Permission Number: 2021-026-2) on 30 July 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Seiya Sakaguchi and Ryoichi Aizawa for data analysis and technical assistance. Their extraordinary contributions have greatly improved the quality of this thesis paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Kota Okabe was employed by the company Miyazaki Airport Building Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| communication range of each cow | |

| specific range determined by radio wave strength where | |

| mutual friends within | |

| split into multiple local networks | |

| unified single network | |

| isolated state |

References

- Dawkins, M.S. Smart farming and artificial intelligence (AI): How can we ensure that animal welfare is a priority? Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2025, 283, 106519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Ma, R.; Luo, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, M. Non-contact sensing technology enables precision livestock farming in smart farms. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 212, 108171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Ogata, K.; Kawasue, K.; Sakamoto, S.; Ieiri, S. Identifying-and-counting based monitoring scheme for pigs by integrating BLE tags and WBLCX antennas. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 198, 107070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Tian, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, C.; Lu, X. Estrus detection in dairy cows using advanced object tracking and behavioral analysis technologies. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkelytė, I.; Siukscius, A.; Nainiene, R. The role of sensor technologies in estrus detection in beef cattle: A review of current applications. Animals 2025, 15, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretzinger, L.F.; Hölper, M.; Tippenhauer, C.M.; Plenio, J.-L.; Madureira, A.; Heuwieser, W.; Borchardt, S. Evaluation of four different automated activity monitoring systems to identify anovulatory cows in early lactation. Animals 2024, 14, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, F.P.; Buijs, S.; Arnott, G. Providing concentrate feed outside of the milking robot increases feed intake in dairy cows without reducing motivation to visit the robot. Animal 2025, 19, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, E.; Brambilla, M.; Cutini, M.; Giovinazzo, S.; Lazzari, A.; Calcante, A.; Tangorra, F.M.; Rossi, P.; Motta, A.; Bisaglia, C.; et al. Increased cattle feeding precision from automatic feeding systems: Considerations on technology spread and farm level perceived advantages in Italy. Animals 2023, 13, 3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Cai, M.; Sun, Y.; Li, B.; Feng, X.; Hao, J.; Wang, H. Beef cattle abnormal behaviour recognition based on dual-branch frequency channel temporal excitation and aggregation. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 241, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurkovich, V.; Hejel, P.; Kovács, L. A review of the effects of stress on dairy cattle behaviour. Animals 2024, 14, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arablouei, R.; Bishop-Hurley, G.J.; Bagnall, N.; Ingham, A. Cattle behavior recognition from accelerometer data: Leveraging in-situ cross-device model learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Lv, Y.; Jiang, R.; Zhao, W.; Li, Q.; Yang, B.; Yu, L.; Ma, W.; Gao, R.; Yu, Q. Predicting the feed intake of cattle based on jaw movement using a triaxial accelerometer. Agriculture 2022, 12, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogoy, K.M.C.; Chon, S.-i.; Park, J.-h.; Sivamani, S.; Lee, D.-H.; Choi, S.H. High precision classification of resting and eating behaviors of cattle by using a collar-fitted triaxial accelerometer sensor. Sensors 2022, 22, 5961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benaissa, S.; Tuyttens, F.A.M.; Plets, D.; Martens, L.; Vandaele, L.; Joseph, W.; Sonck, B. Improved cattle behaviour monitoring by combining Ultra-Wideband location and accelerometer data. Animal 2023, 17, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.O.; Viola, I.; Baratta, M.; Giordano, S. Practical experiences of a smart livestock location monitoring system leveraging GNSS, LoRaWAN and cloud services. Sensors 2022, 22, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, V.; Pastell, M. Monitoring of cow location in a barn by an open-source, low-cost, low-energy bluetooth tag system. Sensors 2020, 20, 3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Perea, A.; Cao, H.; Bakir, M.; Utsumi, S. A two-stage machine learning approach for calving detection in rangeland cattle. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Morota, G.; Bi, Y.; Cockrum, R.R. Predicting dairy calf body weight from depth images using deep learning (YOLOv8) and threshold segmentation with cross-validation and longitudinal analysis. Animals 2025, 15, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.; Todorovic, M.; Sugrue, P.; Teixeira, S.; Galvin, P. Review: Emerging sensors and instrumentation systems for bovine health monitoring. Animal 2025, 19, 101527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galik, R.; Bod’o, Š.; Lüttmerding, A.; Knížková, I.; Kunc, P. Tracking differences in cow temperature related to environmental factors. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ling, M.; Fu, B.; Dong, Y.; Mo, W.; Lin, K.; Yuan, F. UAV based smart grazing: A prototype of space-air-ground integrated grazing IoT networks in Qinghai-Tibet plateau. Discov. Internet Things 2025, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, R.; Hermosa, A.; Marco, Á.; Blanco, T.; Zarazaga-Soria, F.J. Real-time extensive livestock monitoring using LPWAN smart wearable and infrastructure. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, J.; Yubero, R.; Visitación, B.; Navarro-García, J.; Algar, M.J.; Cano, E.L.; Ortega, F. Analysis of accelerometer and GPS data for cattle behaviour identification and anomalous events detection. Entropy 2022, 24, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, M.J.; Grau-Campanario, P.; Mullan, S.; Held, S.D.E.; Stokes, J.E.; Lee, M.R.F.; Cardenas, L.M. Factors affecting site use preference of grazing cattle studied from 2000 to 2020 through GPS tracking: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikusui, T.; Winslow, J.T.; Mori, Y. Social buffering: Relief from stress and anxiety. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2006, 361, 2215–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reenen, C.G.; Mars, M.H.; Leushuis, I.E.; Rijsewijk, F.A.; van Oirschot, J.T.; Blokhuis, H.J. Social isolation may influence responsiveness to infection with bovine herpesvirus 1 in veal calves. Vet. Microbiol. 2000, 75, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).