Abstract

Information-centric networking (ICN) changes the way data are accessed by focusing on the content rather than the location of devices. In this model, each piece of data has a unique name, making it accessible directly by name. This approach suits the Internet of Things (IoT), where data generation and real-time processing are fundamental. Traditional host-based communication methods are less efficient for the IoT, making ICN a better fit. A key advantage of ICN is in-network caching, which temporarily stores data across various points in the network. This caching improves data access speed, minimizes retrieval time, and reduces overall network traffic by making frequently accessed data readily available. However, IoT systems involve constantly updating data, which requires managing data freshness while also ensuring their validity and processing accuracy. The interactions with cached data, such as updates, validations, and replacements, are crucial in optimizing system performance. This research introduces an ICN-IoT method to manage and process data freshness in ICN for the IoT. It optimizes network traffic by sharing only the most current and valid data, reducing unnecessary transfers. Routers in this model calculate data freshness, assess its validity, and perform cache updates based on these metrics. Simulation results across four models show that this method enhances cache hit ratios, reduces traffic load, and improves retrieval delays, outperforming similar methods. The proposed method uses an artificial neural network to make predictions. These predictions closely match the actual values, with a low error margin of 0.0121. This precision highlights its effectiveness in maintaining data currentness and validity while reducing network overhead.

1. Introduction

The future of the internet will extend far beyond conventional computers and software applications, bringing connectivity to countless everyday items and even devices integrated into the human body [1,2]. This transformation, driven by the Internet of Things (IoT), promises a world where almost everything around us, from household appliances to wearable health monitors, is part of a vast, interconnected network [3]. Internet usage primarily focuses on content retrieval and information exchange, often overshadowing two-way host-to-host communication. In the traditional model, users specify a server to request information, restricting the network layer from sourcing data from alternative locations [4].

Information-centric networking (ICN) [5], which uses content-based naming, in-network caching, and name-based routing, provides a more versatile approach [6]. In ICN, users request data by name without specifying their source, allowing any node holding a copy of the data to respond, thus enhancing content accessibility [7]. A central feature of ICN is in-network caching, where intermediary nodes store data ready to be retrieved quickly when requested again [8]. This efficiency depends on factors like cache size, communication cost, and cache policies (including cache decision and eviction criteria) [9]. However, IoT data are often transient and require updates, making data freshness crucial [10]. A caching system must manage data by replacing outdated information with updated content as needed by the user [11]. The accuracy of cached data is crucial for making effective cache decisions [12,13]. Before, IoT systems only determined the data source and freshness of information.

A caching system must manage data by replacing outdated information with updated content that the user needs. Beyond merely retaining recently updated data, the interactions with cached data, including validation of their relevance and timely replacement, ensure that the network delivers accurate and up-to-date information. Robust mechanisms are essential to assess data currentness and validity in IoT systems, considering access frequency and timing. Ensuring data freshness, correctness, and accuracy is crucial for making real-time, critical decisions. Our proposed method goes beyond traditional freshness-based caching strategies by integrating metrics that assess data validity, prioritize updates, and ensure optimized caching actions in dynamic IoT environments. ICN is a network architecture focused on content retrieval rather than traditional end-to-end host communication [12]. It enables efficient data sharing, improved security, and better scalability.

This paper proposes an eight-step method to optimize caching and data freshness in ICN-IoT networks. The process begins with routers identifying whether an incoming message is a data request or a data response. For data request messages, the router checks its cache for availability (cache hit) or unavailability (cache miss) of the requested data. If a cache hit occurs, the router calculates the freshness score of the data to verify their validity and decides whether to deliver the data or forward the request to the next hop. For data response messages, the router checks for duplicates in the cache, replacing older entries when a match is found. If no duplicate exists, the router evaluates whether there is space in the cache for the new data; otherwise, it calculates the time validity of cached entries to remove expired data. If no expired data are found, the router eliminates the data entry with the lowest freshness score to accommodate the new data. This systematic process guarantees caching only the most relevant and current information, enhancing network efficiency. It significantly improves response times in ICN-IoT systems. The contributions of this paper are:

- Enhancing the cache hit ratio by maintaining only recently updated and relevant data in the cache. This avoids ambiguity and uses a more standard term to describe the data;

- Enabling intermediate routers to independently calculate data freshness and make caching decisions based on it, effectively optimizing traffic load;

- Structuring data request messages to include sensor identifiers and data types, which enables efficient data retrieval management based on specific time intervals;

- Improving cache performance by ensuring it contains only current data, which increases cache hits, reduces response delay, and lowers network traffic load.

2. Related Work

The data caching method is designed to optimize data storage and retrieval by selectively caching data at strategic points within a network [14]. In this approach, nodes in the network temporarily store data based on specific criteria, such as data freshness, access frequency, and relevance, allowing for faster data access and reduced communication overhead. When a request is made, cached data can be retrieved from an intermediate node rather than the source, significantly lowering latency and network traffic [15]. This method incorporates caching policies to determine when to store, update, or remove data, focusing on maximizing cache utility and efficiency. This section discusses previous papers and the motivation for conducting this research.

Vural and Navaratnam [16] proposed a distributed probabilistic caching strategy where cache nodes adjust their caching probability based on the distance between the producer and the consumer and the data’s freshness. In this approach, the closer a caching node is to the producer, the fresher the data it can provide. Data received directly from the producer are the freshest but involve higher communication costs due to more hops. Conversely, data retrieved from an intermediate router’s cache have lower freshness but incur a reduced multi-hop retrieval cost. This method seeks to balance the tradeoff between “data freshness” and the cost of multi-hop data retrieval to optimize overall data access in a multi-hop network path.

Quevedo and Corujo [17] proposed a consumer-driven algorithm to confirm information freshness in content-centric networking. This paper first caches data packets with a freshness parameter defined by the data source. In the second step, a consumer requests data based on a specified freshness level. The freshness parameter at the source is important and can either boost or reduce network performance. In this paper, the authors try to reduce negative impacts by having the data producer respond based on the consumer’s specified requirements. The benefit of this proposed method is that consumers can control the freshness of the data, which improves data relevance and freshness.

Hail and Amadeo [18] presented a probabilistic caching strategy for IoT (Pcasting) systems, considering data freshness, energy, and each IoT sensor’s cache space. This proposed method helps decrease energy consumption and delays in data retrieval. The Pcasting method is flexible and compatible with various routing protocols. It can also be adjusted to include extra parameters when needed. The results show that this strategy significantly boosts network efficiency. It provides a flexible, energy-efficient caching solution for IoT environments.

Vural and Wang [19] suggested a model for in-network caching in the IoT that balances communication costs with data freshness. This paper first explores the benefits of caching temporary data in internet routers. It considers both the rate of data requests and the data’s lifetime. Data lifetime refers to the duration for which data stay valid. In the second phase, when a router receives data, it checks freshness by looking at the data’s arrival time, generation time, and expected lifetime. This evaluation helps ensure that only relevant data are stored.

Doan Van and Ai [20] proposed a caching decision algorithm called the Multi-Attribute Cache Decision Strategy (MACDS) for ICN-IoT. The MACDS algorithm considers several important factors, such as energy use, memory space, data freshness, and the hop count between nodes. These attributes allow the MACDS to make smart decisions on data caching locations. The proposed method optimizes resource efficiency while ensuring data accessibility, making it highly suitable for IoT environments with frequent resource constraints. It helps maintain up-to-date information across connected devices. The MACDS algorithm boosts energy efficiency by cutting down on unnecessary data transfers. It also improves network performance by caching frequently requested data in readily accessible locations. This leads to quicker data retrieval and extends the network’s overall lifespan.

Meddeb and Dhraief [21] proposed a caching method for IoT networks that keeps updated data while lowering caching costs. Their approach includes a freshness mechanism that regularly checks cached data, replacing outdated information. This strategy’s careful handling of data freshness keeps information relevant and accurate in constantly changing IoT environments. It ensures that data remain up to date despite frequent updates. The caching process selects nodes directly connected to consumers along the data path to store data. This setup shortens the time needed to retrieve data by reducing the number of hops. This approach speeds up response times and boosts network efficiency. Combining data freshness checks with smart cache placement allows this approach to tackle major IoT challenges. This makes it a useful solution for real-time, data-driven applications in networks with limited resources.

Asmat and Din [22] proposed the Enhanced Edge-Linked Caching (EELC) algorithm and Policy Optimization (PPO) to optimize caching in IoT networks. This proposed method dynamically adapts to current network conditions and prioritizes popular content to make the system more efficient. The EELC scheme stores frequently used data close to users, which reduces energy consumption, server load, and delays in accessing data. This method is an improvement over older techniques, like Edge-Linked Caching (ELC) and Leave Copy Everywhere (LCE), in both efficiency and speed. EELC places frequently accessed data closer to users, which speeds up data access and improves efficiency. This approach also reduces unnecessary data transfers, boosting overall network responsiveness. EELC requires regular updates and monitoring, which takes considerable processing power. This demand can be challenging for devices that have limited resources.

Mishra and Jain [23] presented a smart content replacement strategy designed for ICN in IoT networks, focusing on better cache management by keeping important data readily available. Traditional IoT networks running on TCP/IP face issues like limited address space, high data traffic, and reduced efficiency. ICN, however, allows in-network caching, where data are stored temporarily in intermediate nodes, supporting faster data retrieval and reducing network load. Traditional caching policies, like First In, First Out (FIFO); Least Recently Used (LRU); and Least Frequently Used (LFU), fail to account for the transient nature of IoT data, leading to frequent eviction of critical content. To address this, the authors introduced a novel replacement policy—evaluating data requests, content freshness, and upcoming request wait times (URWTs) to prioritize cache content effectively. Preemptively tracking these attributes in the Pending Interest Table (PIT) enables their method to remove less critical data while retaining high-value content efficiently.

Luo and Yan [24] proposed the Caching Algorithm based on Random Forest (CARF) for low earth orbit satellite mega-constellations, applying ICN to the IoT environment. The CARF uses the “viscosity” concept to integrate content popularity and satellite node location predictions to enhance cache placement accuracy. The Random Forest (RF) algorithm in the CARF allows for proactive caching of popular content at ideal satellite locations, effectively reducing access delays. This strategic placement enhances cache hit rates and throughput, ensuring faster data retrieval for users. As a result, the CARF demonstrates superior performance compared to traditional methods, like Leave Copy Everywhere (LCE) and Leave Copy Down (LCD). The method improves caching efficiency but demands significant computational resources and relies on precise satellite location prediction, which may limit its applicability under resource constraints or unexpected satellite path deviations. Table 1 shows the pros and cons of the proposed methods.

Table 1.

Advantages and disadvantages of the proposed methods.

Research Motivation and Identified Gaps

This study’s motivation arises from the need to address several persistent challenges in data caching within IoT networks, particularly those utilizing ICN. Existing methods, while innovative, have limitations that affect network efficiency, data freshness, cache management, and overall QoS. These gaps, highlighted in the existing literature, provided the impetus for our proposed method to tackle deficiencies in previous caching strategies.

A primary challenge identified in prior works is balancing data freshness with caching efficiency. Studies by Vural et al., Vural and Navaratnam [16], and Quevedo and Corujo [17] attempted to incorporate data freshness into their caching strategies, yet they often relied on static parameters or distance-based caching that did not fully capture real-time fluctuations in data validity. Our work addresses this gap by implementing dynamic data freshness calculations, enabling more precise caching decisions, and optimizing data relevancy across variable IoT traffic loads. Furthermore, solutions like those proposed by Hail and Amadeo [18] and Doan Van and Ai [20] introduced adaptive caching parameters, such as energy and memory. However, these approaches overlooked the cumulative impact of cache decision delays on network latency, leading to suboptimal performance in highly time-sensitive IoT environments. Our method seeks to mitigate latency without imposing excess computational load on network nodes by focusing on cache decision timeliness and utilizing a multi-criteria approach.

Another key gap in the literature involves the need for flexible mechanisms for cache eviction based on data expiration or redundancy. Traditional methods, like the LRU and probabilistic models, frequently need to accommodate the dynamic nature of IoT-generated data. Techniques like EELC by Asmat and Din [22] provided an early attempt at context-based cache decisions but struggled with scalability due to heavy computational requirements. In contrast, our proposed method utilizes a lightweight, freshness-based eviction strategy tailored to maximize cache utility while minimizing resource consumption, thus enhancing scalability for resource-constrained IoT networks.

Finally, the limitations of predictive caching and traffic load distribution models prompted us to introduce a proactive caching approach that considers historical data patterns. While models like those by Meddeb and Dhraief [21] and Mishra and Jain [23] addressed data validity, they lacked predictive insights for high-demand scenarios. Incorporating data freshness indicators with predictive cache placement enables our method to anticipate better and meet peak traffic demands. This approach optimizes cache hit ratios, reduces network delays, and lowers traffic load. This study, therefore, fills critical gaps by combining real-time freshness validation, optimized cache replacement strategies, and predictive cache management, enhancing the overall responsiveness and reliability of IoT caching systems.

3. Problem Statement

Maintaining data freshness in IoT systems within ICN architectures is crucial yet challenging due to the continuous generation of time-sensitive data by IoT devices [25]. In these networks, routers save data along the path to reduce delay and improve bandwidth use. Without a way to verify data freshness, outdated information could be sent to IoT clients [26]. This can result in poor decisions and slower system responses. This issue becomes more complex as IoT networks grow, with data demands constantly changing.

The quick aging of sensor data also raises the risk of sending outdated information. A strong system is needed to ensure that only updated and relevant data are stored and quickly accessible to users [27]. Traditional ICN [28] caching methods do not effectively manage data freshness, which can lead to poor cache use. This often results in lower cache hit rates and less efficient network performance. These methods usually do not account for real-time factors to check if data are still valid, like comparing when data were created to when they were requested. They also overlook how often the data are requested, which affects their relevance. Without precise freshness management, outdated data can remain in caches, taking up valuable space. Since IoT applications need reliable, up-to-date data for tasks like monitoring and control, a better caching method is urgently needed [29,30]. This approach must accurately assess data freshness and prioritize which data to replace in the cache based on their usefulness and validity. This ensures the cache performs well and keeps reliable data available across IoT networks.

3.1. QoS Formula

The cache hit rate metric shows how well a caching system performs by calculating the percentage of requests fulfilled directly from the cache rather than fetching data from slower storage [22,31]. A higher cache hit rate usually means quicker data access, less delay, and better Quality of Service (QoS) by reducing the strain on backend resources [32]. A high cache hit rate in network systems can also lower bandwidth usage because data are retrieved locally from the cache instead of repeatedly pulling from the main source. Optimizing cache hit rates is crucial for applications requiring rapid data access, such as content delivery networks (CDNs) and real-time data processing in IoT systems [33]. Effective caching algorithms, like the proposed method in your simulations, aim to maximize cache hits over time, outperforming traditional methods like LRU under various operational conditions. Equation (1) is used to calculate the cache hit rate:

Number of cache hits refers to the successful instances where the requested data were found in the cache. The total number of requests is the overall number of requests made during the simulation period.

Network delay (D) represents the time taken for data to travel from the source to the destination across a network, affecting the overall response time in networked systems [31]. High network delays can result from long transmission paths, heavy network traffic, or processing delays at intermediate nodes. Reducing network delay is essential for applications requiring low-latency communication, including real-time video streaming, IoT systems, and online gaming. Effective caching mechanisms, such as the proposed method in your simulations, help lower network delay by reducing the need for frequent data retrievals from the source. Caching frequently accessed and up-to-date data enables the network to achieve faster response times and improve QoS, outperforming traditional caching approaches, such as LRU. Equation (2) was used to evaluate the delay [34]:

, measured in milliseconds (ms), represents the round-trip time delay for data to travel to and from the source. , in milliseconds (ms), denotes the processing time at each network node or router. is the queuing delay for packets waiting to be processed or transmitted and is the transmission time for data across the network.

Traffic load (TL) measures the volume of data or requests that pass through a network over a certain period, reflecting network demand and potential congestion. High traffic load can strain network resources, resulting in slower response times and increased packet loss, which negatively impacts QoS [35]. Caching frequently requested data closer to users reduces traffic load as fewer requests need to reach the original data source, alleviating network burden. In the simulations, the proposed caching method reduced traffic load more effectively than the LRU algorithm by serving additional requests from intermediate caches. This decrease in traffic improves network efficiency, saves bandwidth, and lowers latency, which is beneficial for applications needing quick data access and minimal delay. Traffic load was calculated by Equation (3):

Root mean square error (RMSE) is a standard metric for measuring the accuracy of predictive models by showing the average difference between predicted and actual values [36]. It is calculated by finding the square root of the average of squared differences between observed and predicted values, keeping the result in the same units as the original data. A lower RMSE indicates more accurate predictions. This metric is especially valuable in regression and time series forecasting, where accurate predictions are critical, as it reveals the average error size in predictions [37]. This metric helps pinpoint areas where improvements could enhance overall model performance. Equation (4) was used to calculate the value of RMSE:

In Equation (4), is the total number of observations, represents the predicted or estimated value for the i-th observation, and represents the actual or measured value for the i-th observation. When , the term represents the squared difference between the predicted and observed values for the second observation. This contributes to the overall sum of squared errors. The formula applies to all , ensuring the RMSE is calculated as a single, unique value representing the average error over all observations.

3.2. Calculating Data Freshness

The proposed method utilizes data freshness calculations within the Named Data Network (NDN)-based ICN-IoT architecture to efficiently manage cached data in response to consumer requests. This approach uses freshness as a primary criterion for determining whether data should be retrieved from cache, forwarded, or replaced, optimizing response times and cache utilization. Each step of the method is described below.

Step 1: Start and Check for Message Type

The process begins when the router receives an incoming message, either a data request message or a data response message from a consumer. A data request message specifies a request for specific information while a data response message carries the requested data. The type of message determines the router’s subsequent actions. To classify the message, let denote the incoming message. The router determines whether belongs to the set of data request messages or the set of data response messages based on its contents. This classification can be represented by Equation (5):

Here, represents the set of data request messages, which contain information such as the requested data type, sensor ID, and request time, while represents the set of data response messages, which include the actual sensor data. The router determines the set membership by analyzing specific fields in the message, such as headers or metadata. If the router checks its cache for the requested data. If , the router evaluates caching decisions based on the recency and validity of the data.

Step 2: Check Cache for Requested Data

In the proposed method of this study, the data request message is sent by the client and received by a router along the transmission path. Each request message specifies the sensor number and the data item type (). For example, the client may request the average temperature of a room over the last 15 min. Here, the “average temperature over the last 15 min” corresponds to the data item type () while the specific temperature request for a particular room refers to a sensor with a unique identifier.

Upon receiving a data request message, the router searches its cache or Content Store (CS) for the requested data. This process determines whether a cache hit (data are found) or a cache miss (data are not found) occurs. The cache status is represented by Equation (6), where indicates a cache hit and signifies a cache miss:

Step 3: Calculate Data Freshness

If the data are found in the cache, the router calculates the data freshness to verify their validity. Freshness is determined by Equation (7):

RT (Request Time) represents the time when a consumer requests data while CDTS (Cached Data Time Stamp) indicates the time when the data are stored in the cache. (Requested Data Type) is a numerical value representing the refresh rate of the requested data type. is the freshness score, with values closer to 1 indicating fresher data. If , the data are considered valid and ready to be sent to the consumer.

Step 4: Cache Hit or Cache Miss Decision

Depending on the result of the freshness calculation, the router decides whether to deliver the data or forward the request. If , indicating a cache hit with valid data, the router sends the data to the consumer. If , or if the cache does not contain the requested data, a cache miss occurs, and the data request message is forwarded to the next step. The decision to forward is calculated by Equation (8). Forward = 1 means the data request message is forwarded while Forward = 0 indicates the data are sent directly to the consumer:

Step 5: Check for Data with a Matching Sensor Number and Type in the Cache

When a data message is received, the router first checks whether the cache already contains data with the same sensor number and data type. This is expressed by Equation (9). If = 1, the old data are removed and the new data are cached; otherwise, the router proceeds to the next step.

Step 6: Check for Empty Space in the Cache

If no duplicate data are found, the router checks if there is space in the cache for the new data. Cache space is represented by Equation (10). If , the new data are cached; if , the router moves to the next step:

Step 7: Check for Expired Data in the Cache

If the cache is full, the router checks for expired data by calculating the time validity of cached entries. Time validity is calculated by Equation (11):

represents the time when new data become available for caching, indicates the time when the data were originally stored in the cache, and reflects the refresh rate of the new data type. If , the cached data are deemed expired and removed to accommodate the new data.

Step 8: Remove Data with the Lowest Freshness Score if No Expired Data are Found

If no expired data exist, the router calculates the freshness score of all cache entries and removes the data with the lowest score to cache the new data. The overall validity score is calculated by Equation (12):

represents the combined freshness and validity score, where is a weighting coefficient that balances the importance of freshness and validity in the calculation. Additionally, is considered a network-specific constant because its value is chosen based on the specific characteristics and requirements of the network environment, such as the frequency of data updates, the priority of real-time data, or the caching strategy employed. For example, in networks where data freshness is critical, α may be set closer to 1 to provide further weight to freshness. Conversely, in scenarios where data validity or historical relevance is more important, may be set closer to 0 to emphasize validity. The freshness rate is calculated by Equation (13):

Here, the same request number represents the count of requests made specifically for a particular data type while total requests denotes the overall number of requests during the observation period. A value indicates that the data type is more frequently requested, making it more likely to be prioritized for caching.

This systematic process ensures that only the most relevant and up-to-date data are retained in the cache, optimizing resource utilization and enhancing response times for consumers in the ICN-IoT network. Algorithm 1 shows the proposed method pseudocode.

| Algorithm 1: Pseudocode of the proposed method. |

| START //Step 1: Check for Message Type 1. RECEIVE M //Incoming message 2. IF M ∈ τ THEN //If M is a data request message 3. MESSAGE_TYPE ← “REQUEST” 4. ELSE IF M ∈ D THEN //If M is a data response message 5. MESSAGE_TYPE ← “RESPONSE” 6. ELSE 7. RETURN “Invalid Message” //Step 2: Check Cache for Requested Data 8. IF MESSAGE_TYPE = “REQUEST” THEN 9. CHECK_CACHE(M.sensor_number, M.data_type) 10. IF (M.sensor_number, M.data_type) ∈ CS THEN 11. Cache_Status ← 1 //Cache hit 12. ELSE 13. Cache_Status ← 0 //Cache miss 14. END IF //Step 3: Calculate Data Freshness 15. IF Cache_Status = 1 THEN 16. V ← 1 - (RT - CDTS)/R_type 17. IF V > 0 THEN 18. SEND_DATA_TO_CONSUMER( ) 19. ELSE 20. FORWARD_REQUEST() 21. END IF 22. ELSE 23. FORWARD_REQUEST() 24. END IF //Step 4: Cache Hit or Cache Miss Decision 25. ELSE IF MESSAGE_TYPE = “RESPONSE” THEN //Step 5: Check for Matching Data in Cache 26. IF (M.sensor_number, M.data_type) ∈ CS THEN 27. REMOVE_OLD_DATA(M.sensor_number, M.data_type) 28. CACHE_NEW_DATA(M) 29. ELSE //Step 6: Check for Empty Space in Cache 30. IF AVAILABLE_CACHE_SPACE > 0 THEN 31. CACHE_NEW_DATA(M) 32. ELSE //Step 7: Check for Expired Data in Cache 33. FOR EACH DATA_ENTRY IN CS DO 34. Time_validation ← 1 - (NDTS - CDTS)/NDtype 35. IF Time_validation ≤ 0 THEN 36. REMOVE_EXPIRED_DATA(DATA_ENTRY) 37. CACHE_NEW_DATA(M) 38. BREAK 39. END IF 40. END FOR //Step 8: Remove Data with Lowest Freshness Score 41. IF NO_EXPIRED_DATA_FOUND THEN 42. CALCULATE_FRESHNESS_AND_VALIDITY() 43. REMOVE_LOWEST_SCORE_DATA() 44. CACHE_NEW_DATA(M) 45. END IF 46. END IF 47. END IF 48. END IF END |

3.3. Predicting Data Freshness

The CAL method incorporates a prediction mechanism using the Nonlinear Autoregressive (NAR) neural network to enhance caching efficiency. In the fourth step of the caching process, routers predict the data’s freshness rate and calculate the validity of cached data based on the predicted freshness. This proactive approach reduces unnecessary data replacements and ensures that the cache retains the most relevant and current data. The NAR model forecasts future data freshness by analyzing past traffic patterns. Specifically:

- Input Layer: Processes historical request data, such as the sensor request number (SRN) and total requests (TRs) for specific data types;

- Hidden Layer: Configured with an optimized number of neurons to balance learning complexity and computational efficiency;

- Output Layer: Produces the predicted freshness rate () for the specified data;

For requests specific to a sensor ID or data type, the corresponding historical request counts are used as inputs to forecast the future request rate.

These predictions are utilized in the CAL method to calculate data validity, guiding decisions about which data to retain or replace in the cache. The combination of historical traffic data and neural network predictions enables CAL to maintain high accuracy in its caching strategy while reducing computational overhead and network traffic. Predicted freshness values are computed as follows:

- The network uses past request data to predict PSRN (predicted SRN) and PTR (predicted total requests);

- Equation (14) calculates the predicted freshness rate ():

- Equation (15) evaluates the predicted validity ():

The predicted freshness values guide the CAL method’s caching decisions, allowing routers to prioritize more relevant data. This integration minimizes unnecessary cache replacements and enhances the overall efficiency of IoT data dissemination.

4. Evaluation

This section thoroughly analyzes the simulated scenario, including the selection and justification of the parameters used to accurately represent real-world conditions within the network environment. The scenario aims to reflect typical usage patterns and operational constraints encountered in a NDN-based ICN-IoT architecture, ensuring the results.

4.1. Simulation Scenario

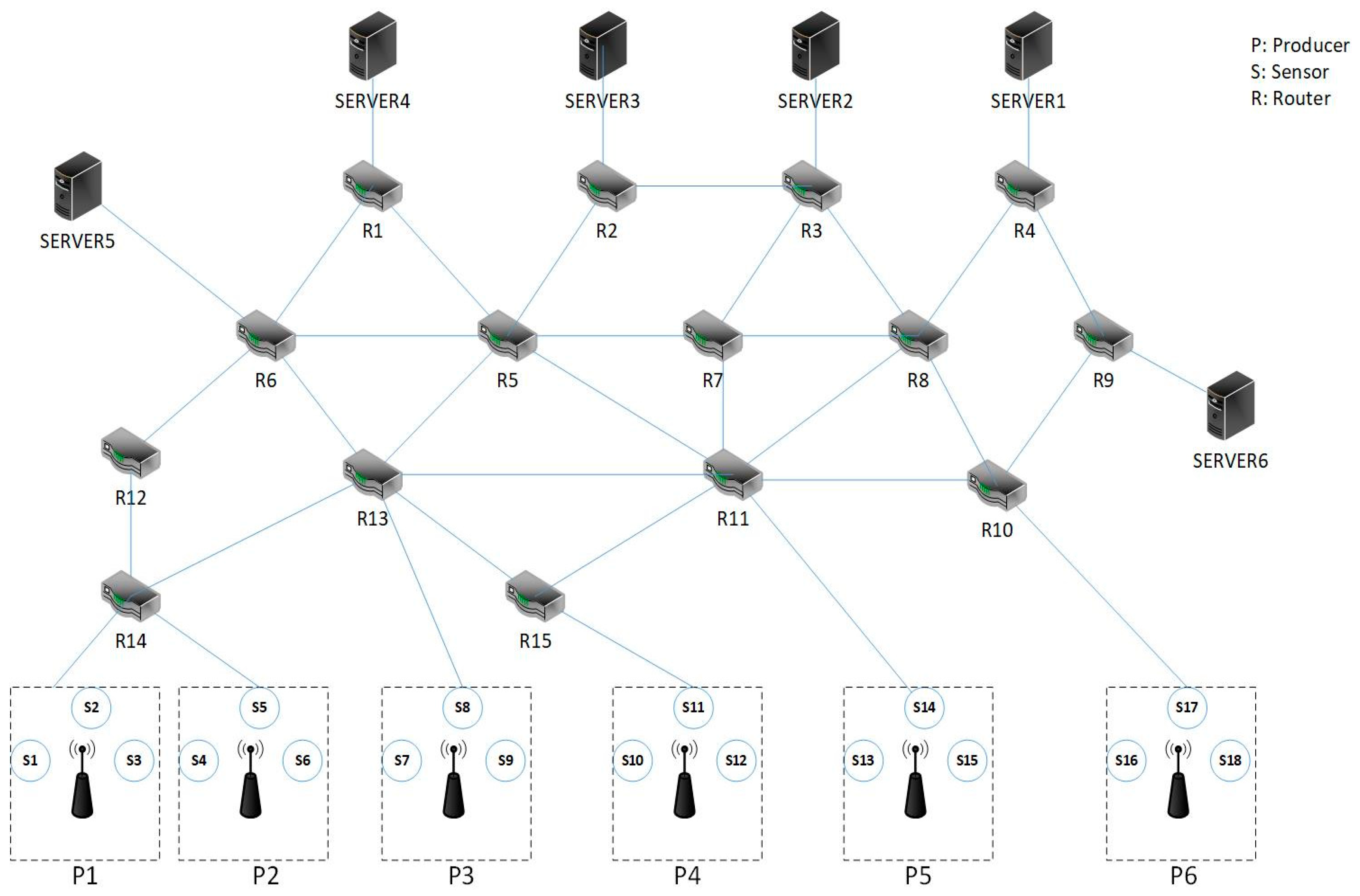

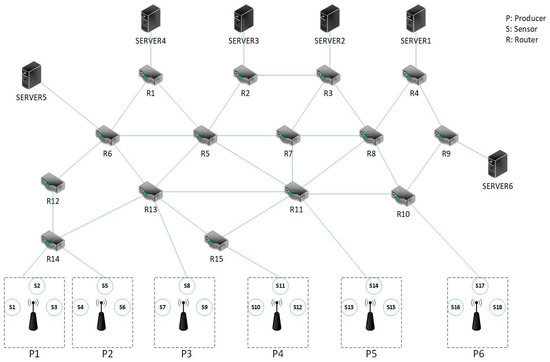

As shown in Figure 1, the simulation scenario is a network consisting of six consumer nodes (servers), fifteen router nodes, and six data producer nodes. Each consumer node is connected to the producer nodes through different routes via multiple routers. The communication paths between each server and the producers are statically determined. Each producer node is connected to three sensors, which collect data and send it to the requesting consumer. The sensors are Wi-Fi stations connected to a wireless access point (producer node) in infrastructure mode. All communications in this topology are wireless and the routers are Mikrotik Netmetal 5 devices with MIPS architecture.

Figure 1.

Topology of the simulated scenarios.

4.2. Simulation Parameters

Table 2 summarizes the parameters used to simulate the proposed approach scenario.

Table 2.

Simulation parameters.

In the simulations, messages are randomly generated using MATLAB. Each data request message includes the request number, applicant number, request time, requested sensor number, and data item type. Once generated, the data request message is sent according to their request times. According to the topology in Figure 2, each requesting node sends its message along a specific path to the data producer identified in the request. Each path consists of multiple hops and the data request message passes through several intermediate routers. If the cache cannot fulfill the request, it is forwarded to the producer. In this simulation scenario, network delays are modeled by considering each data exchange’s propagation and transmission delays and the processing time and data handling at each router. The size of the exchanged data packets determines the traffic load for each period. The scenario is simulated using the LRU method and the proposed approach, each tested separately in eight modes based on simulation time, period length, and the number of requests. MATLAB version R2022 was used for all simulations.

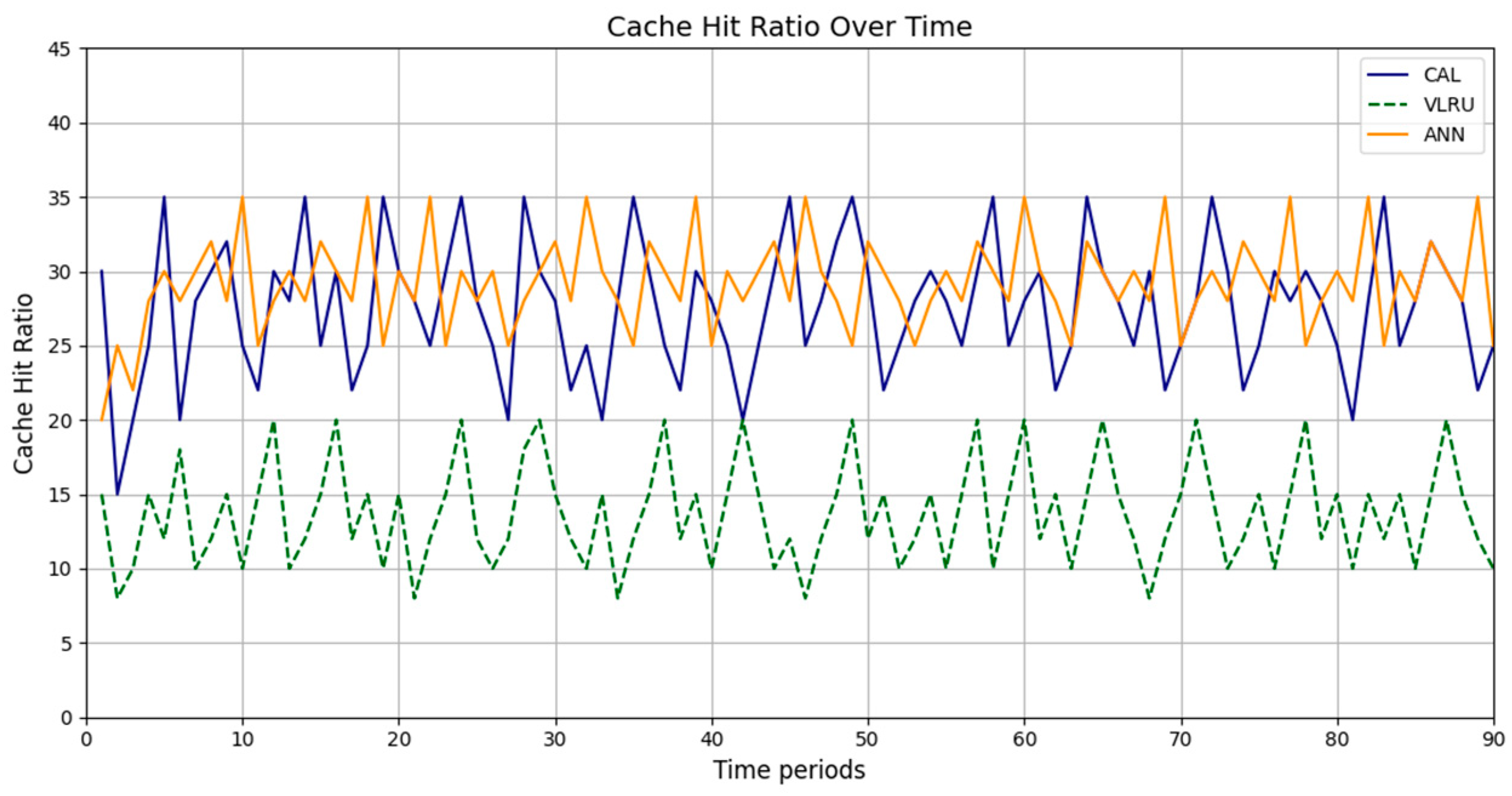

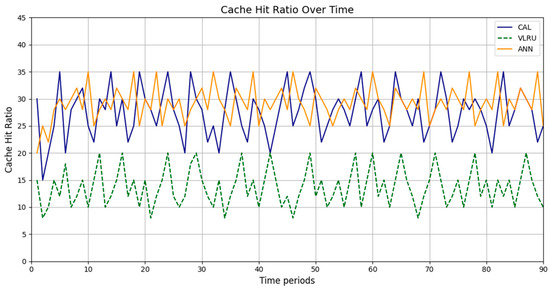

Figure 2.

Cache hit ratio of the caching methods in Model 1.

Simulation metrics included:

- Cache Success Rate: The percentage of data requests the cache satisfies;

- Network Traffic Load: Total network bandwidth utilized for data retrieval;

- Response Time: Time taken to retrieve requested data.

4.3. Discussion

The proposed method integrates time series analysis to handle the temporal nature of data freshness in IoT environments. Each data packet is tagged with time stamps, including the Cached Data Time Stamp (CDTS) and Request Time (RT), to calculate a freshness score dynamically. This approach ensures that cache decisions are based on the temporal relevance of the data, prioritizing recently updated or frequently requested information. Additionally, the time-dependent patterns observed in request frequencies are considered in predictive models, such as the Artificial Neural Network (ANN), to optimize caching decisions proactively. These time-dependent variables enable the method to effectively handle the ever-changing nature of data generated in IoT environments.

The ANN employed in this study was designed to predict key performance metrics, such as cache hit ratios and network delays, under various simulation scenarios. The ANN architecture consisted of three hidden layers, each comprising sixty-four neurons. The ReLU activation function introduced non-linearity, ensuring the model could capture complex relationships between input features. The input features for the ANN included request frequency, data freshness, and historical cache hit ratios, which were generated and extracted from simulation scenarios using MATLAB. The network leveraged these features to identify patterns and trends in the data, facilitating more accurate predictions of system behavior. Training the ANN involved splitting the data into a training set (70% of the total data) and a validation set (30%), ensuring the model could generalize effectively to unseen data. Backpropagation with a mean squared error (MSE) loss function was used during training to iteratively minimize prediction errors, enhancing model accuracy over successive iterations. The RMSE metric was used to assess the ANN’s performance, providing a quantitative measure of prediction accuracy. Lower RMSE values indicated the ANN’s reliability in forecasting key outcomes, such as the likelihood of cache hits and delays. The ANN’s role extended beyond predictions—it served as a baseline for comparison with the proposed caching method, especially in scenarios where predictive models could enhance decision making. Analyzing patterns in historical data, the ANN showcased the benefits of integrating machine learning techniques into caching systems. This highlights their capacity to anticipate system demands and enhance performance.

The simulation results were assessed across three key performance metrics: cache hit ratio, network delay, and traffic load. Our proposed cache aging with learning (CAL) method was compared with two established techniques, the ANN and Variable Least Recently Used (VLRU) algorithms. Results indicate that under extended simulation durations and frequent, high-volume data requests, CAL outperformed the alternatives by effectively caching data while preserving their freshness. This contributed to reduced network delays and optimized traffic load. The findings underscore efficient cache management’s importance in handling high-demand scenarios in networked environments, enhancing data availability and system responsiveness. However, if fewer requests are sent over longer intervals, the method’s benefits are less noticeable. Therefore, we focused on scenarios with longer simulation times, higher request volumes, and shorter intervals, as shown in Table 3, where the results demonstrate the method’s effectiveness in achieving our study’s goals.

Table 3.

Simulation modes.

However, the results also reveal that CAL’s effectiveness compared to the ANN was insignificant in certain scenarios. Specifically, CAL showed marginal improvements in cases with lower request frequencies or longer intervals between requests. This is because CAL primarily focuses on real-time data freshness, which limits its adaptability to fluctuating traffic patterns. In contrast, the ANN’s predictive modeling capabilities enable it to anticipate system demands and optimize cache decisions accordingly, giving it a distinct advantage in such scenarios.

This performance gap can also be attributed to the static nature of CAL’s cache aging mechanism. While CAL effectively prioritizes recently updated data, it lacks the flexibility to dynamically adjust its parameters based on observed trends or historical request patterns. Conversely, the ANN utilizes a dynamic learning process that continuously adapts its caching strategies as new patterns emerge. This allows the ANN to maintain a higher cache hit ratio in environments with variable or unpredictable request frequencies as it can allocate resources more efficiently.

Another contributing factor is the reliance of CAL on pre-defined thresholds for determining data freshness. These thresholds, while effective in scenarios with consistent data traffic, may lead to suboptimal performance in situations where traffic intensity varies significantly. The ANN mitigates this issue using real-time input features, such as request frequency and historical data, to make more informed caching decisions. As a result, the ANN exhibits better overall responsiveness to the inherent variability in IoT environments, particularly in cases with less frequent or irregular request patterns.

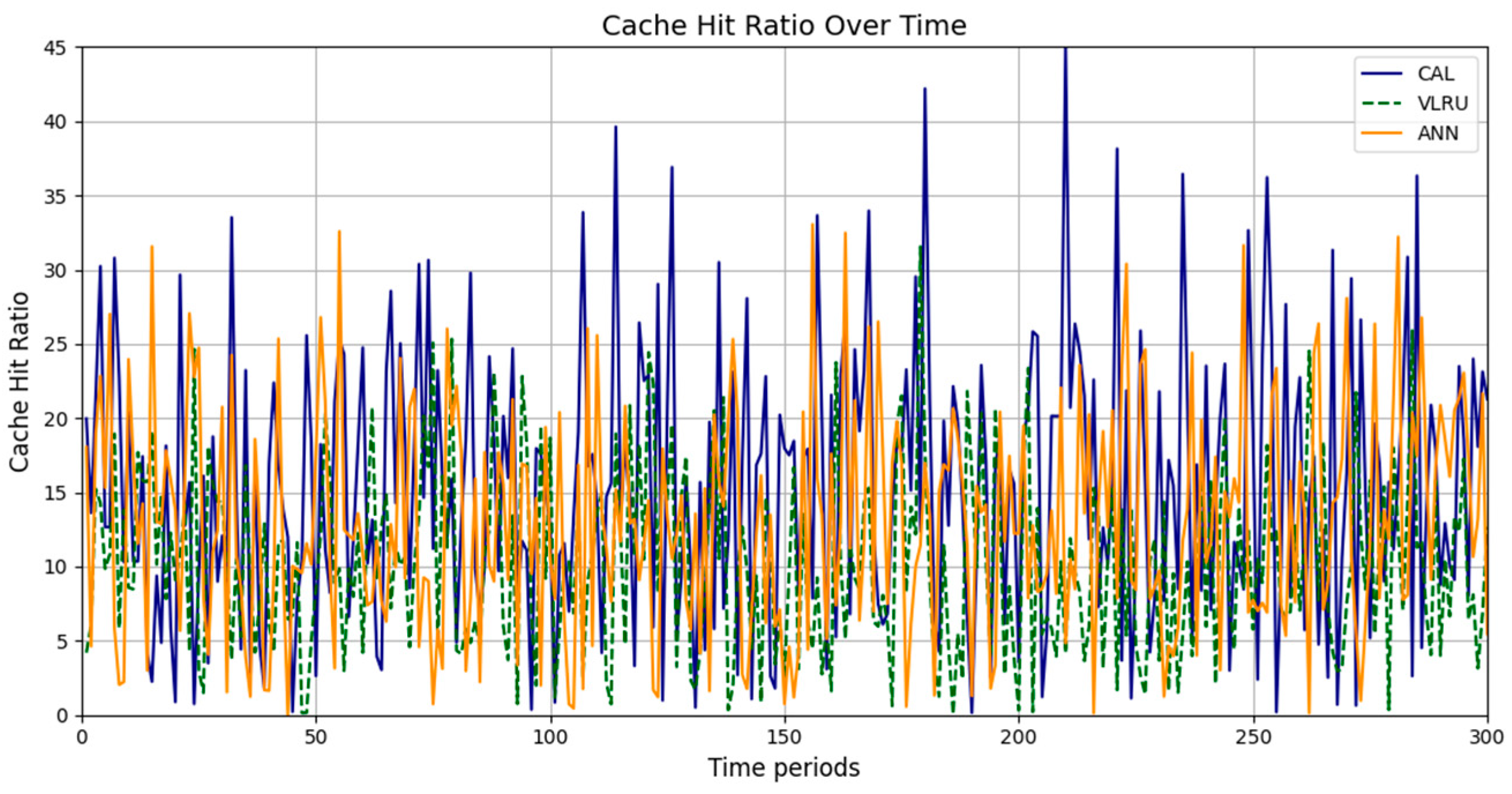

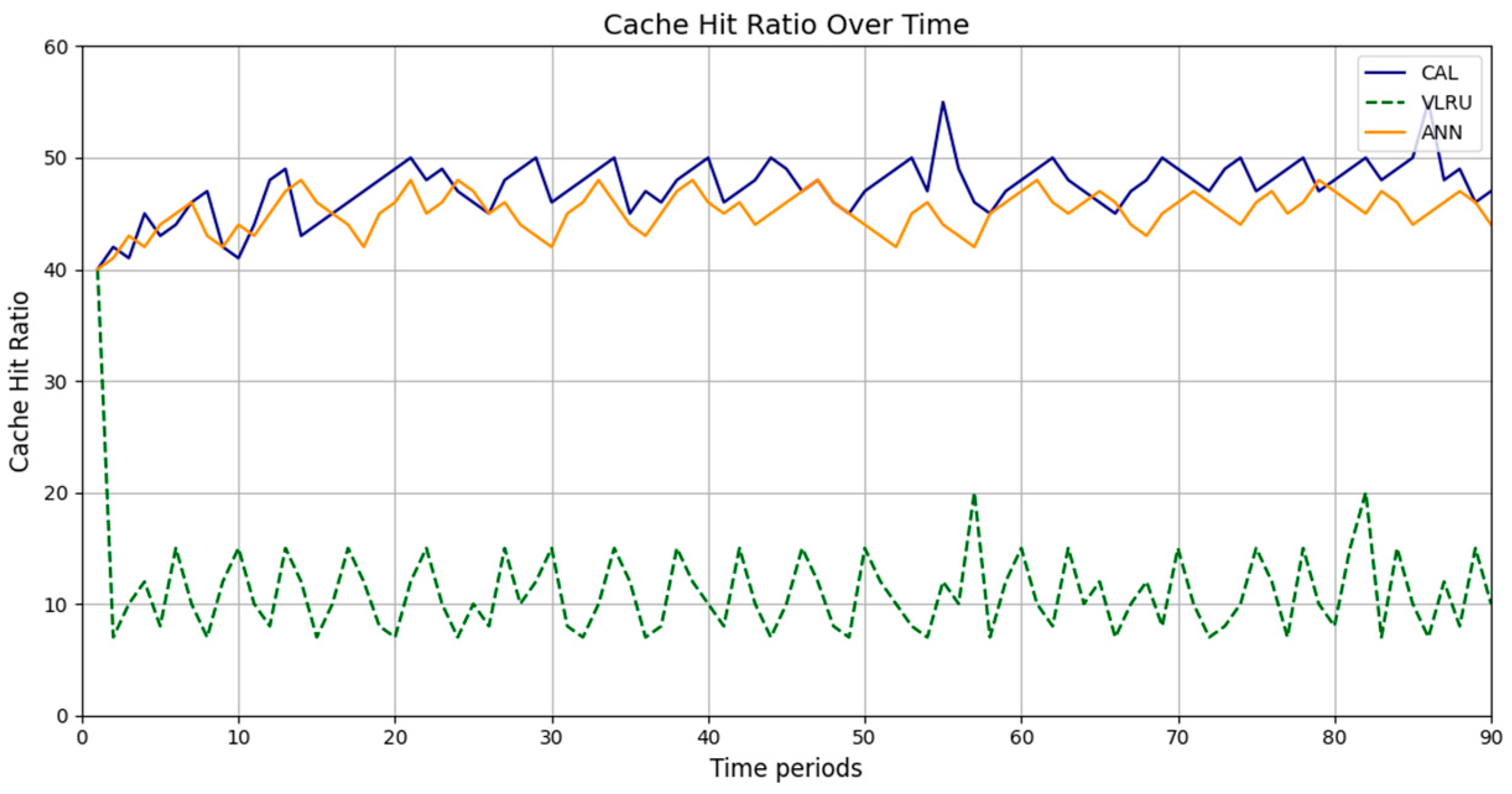

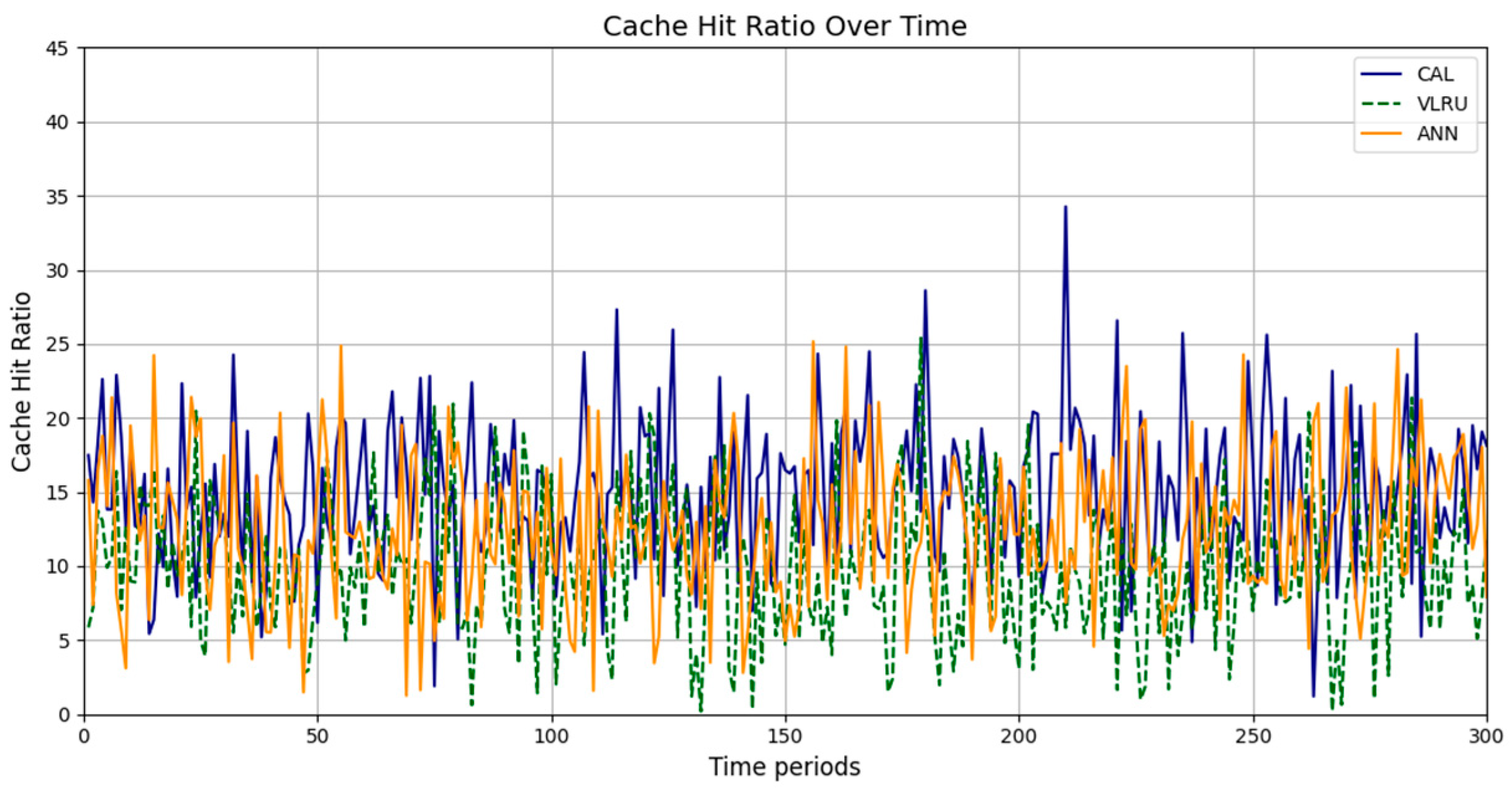

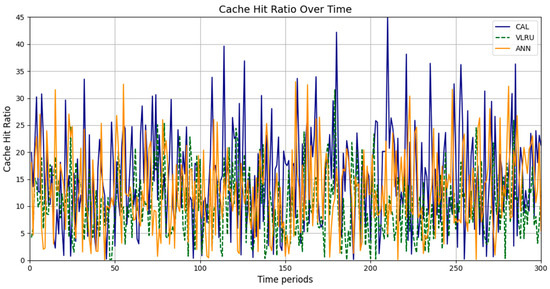

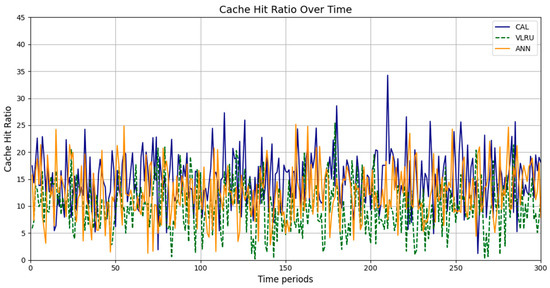

Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 present the simulation results in four different modes, as outlined in Table 3. Figure 2 illustrates the cache hit rate of the proposed method in the first simulation model, which includes 3000 requests over 180 s. As shown in Figure 2, the cache hit ratio of the proposed method is higher than that of the VLRU method. Figure 3 depicts the cache hit ratio of the caching methods in the second simulation model, where the proposed method again achieves a considerably higher cache hit ratio than the VLRU algorithm. The proposed caching method outperforms the VLRU method in terms of the cache hit ratio across different simulation models. The simulation results indicate a significant difference in cache hit rate between the proposed method and the VLRU method; the proposed method substantially improves cache hit rate performance.

Figure 3.

Cache hit ratio of the caching methods in Model 2.

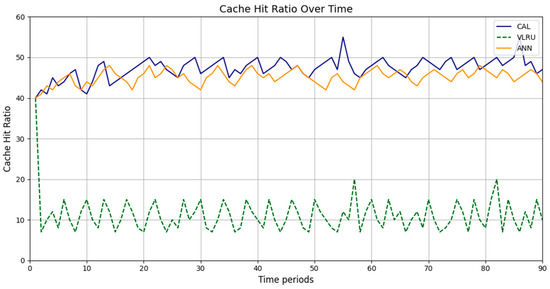

Figure 4.

Cache hit ratio of the caching methods in Model 3.

Figure 5.

Cache hit ratio of the caching methods in Model 4.

Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the simulation results for Models 3 and 4. The third model’s simulations include 3000 requests over 120 s. As shown in Figure 4, the cache hit rate of the proposed method is significantly higher than that of the VLRU method and is approximately equal to the values estimated by the ANN. Figure 5 depicts the cache hit ratio of the caching methods in the fourth simulation model, where the cache hit ratio of the proposed method is again a bit higher than that of the VLRU algorithm. The simulation results across all four models confirm the superiority of the proposed method in terms of cache hit rate, demonstrating a significant improvement in cache hit rate performance.

Making cache decisions based on data freshness allows routers to cache data that are more likely to be re-requested by other consumers. Due to the high cache hit ratio and the lack of frequent reference to the data source, network delay has been reduced compared to the VLRU method. It should be noted that a large part of the network delay for the proposed method in the diagrams is related to the execution time of the router processes for cache decisions. Due to the implementation of this method in the simulation environment, the computational time for the simulated processing of routers is longer than in the natural environment. If implemented in the real environment, the network latency is significantly less than in the simulation results. The caching methods impose performance overhead on the system. The imposed performance overhead by the caching techniques should be evaluated as the other criteria. Network delay and traffic load are the leading performance overhead assessed in this study.

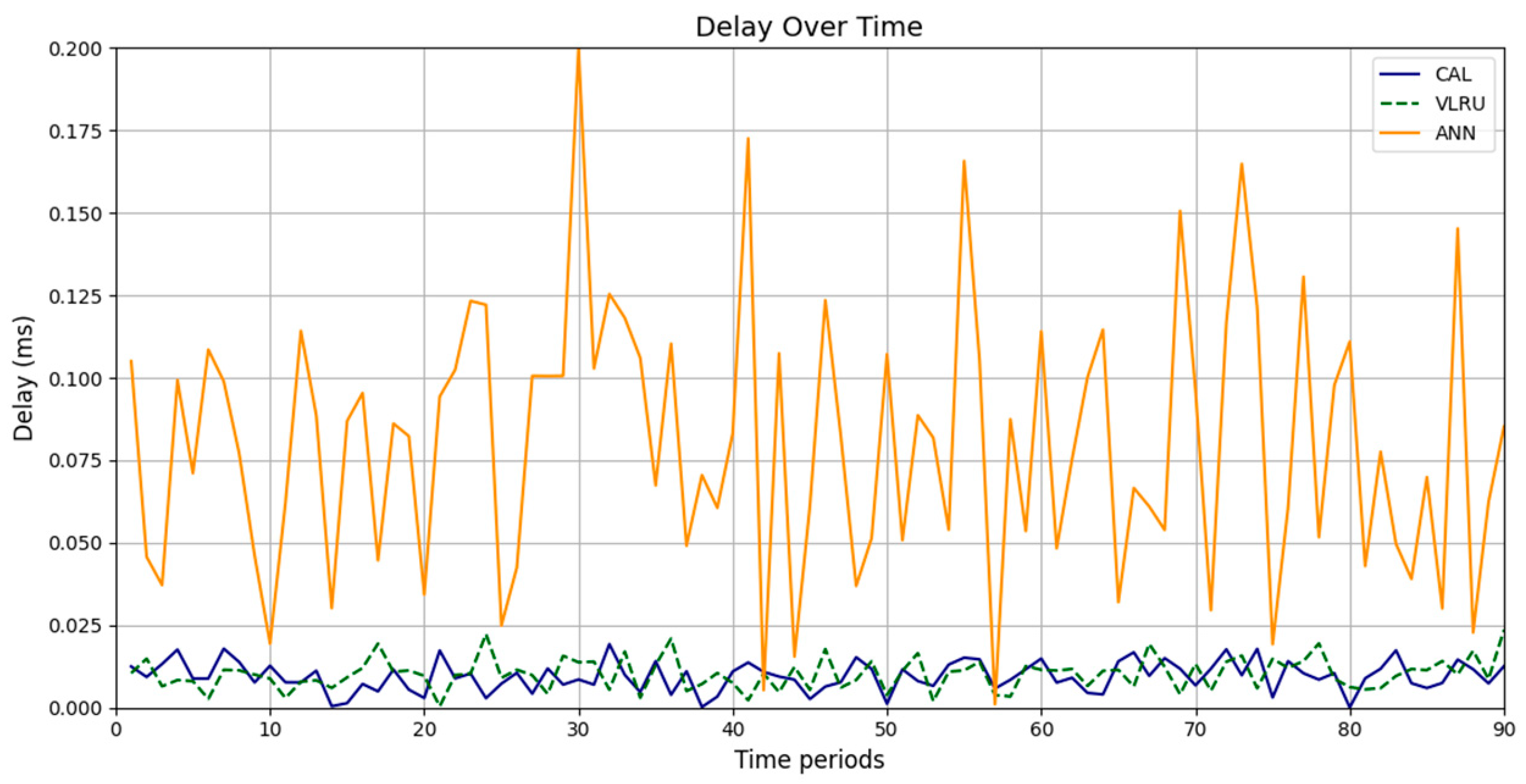

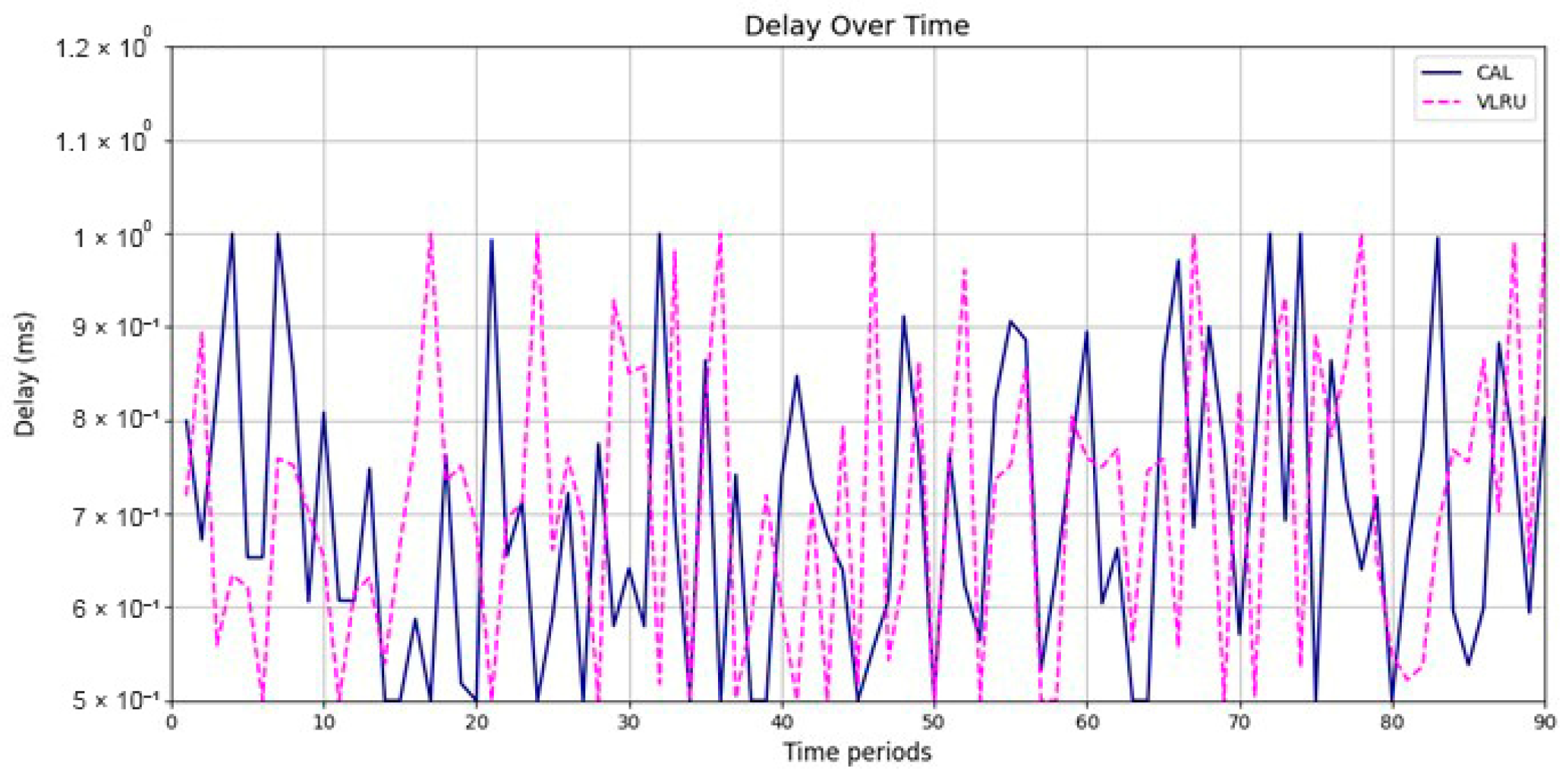

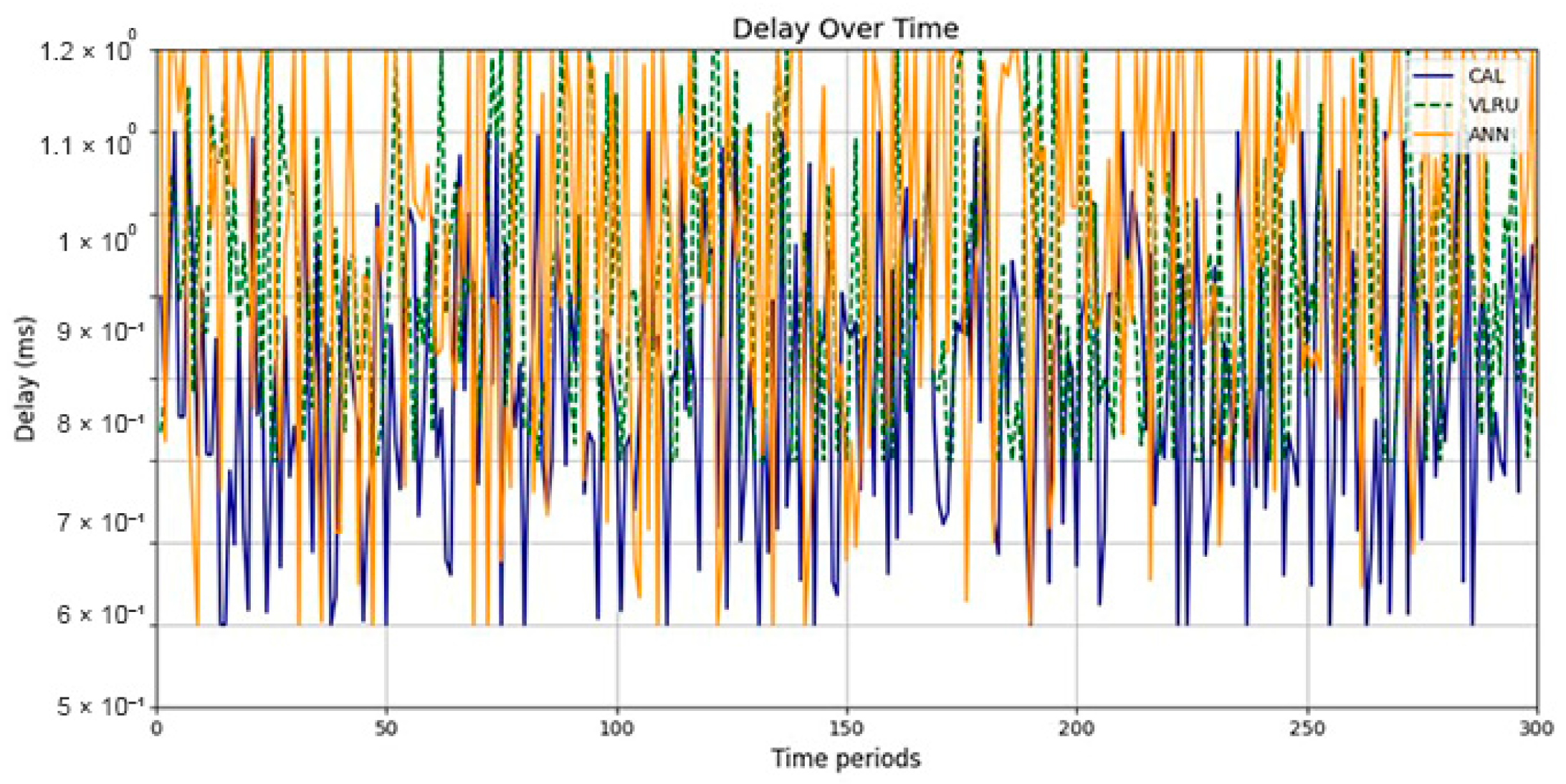

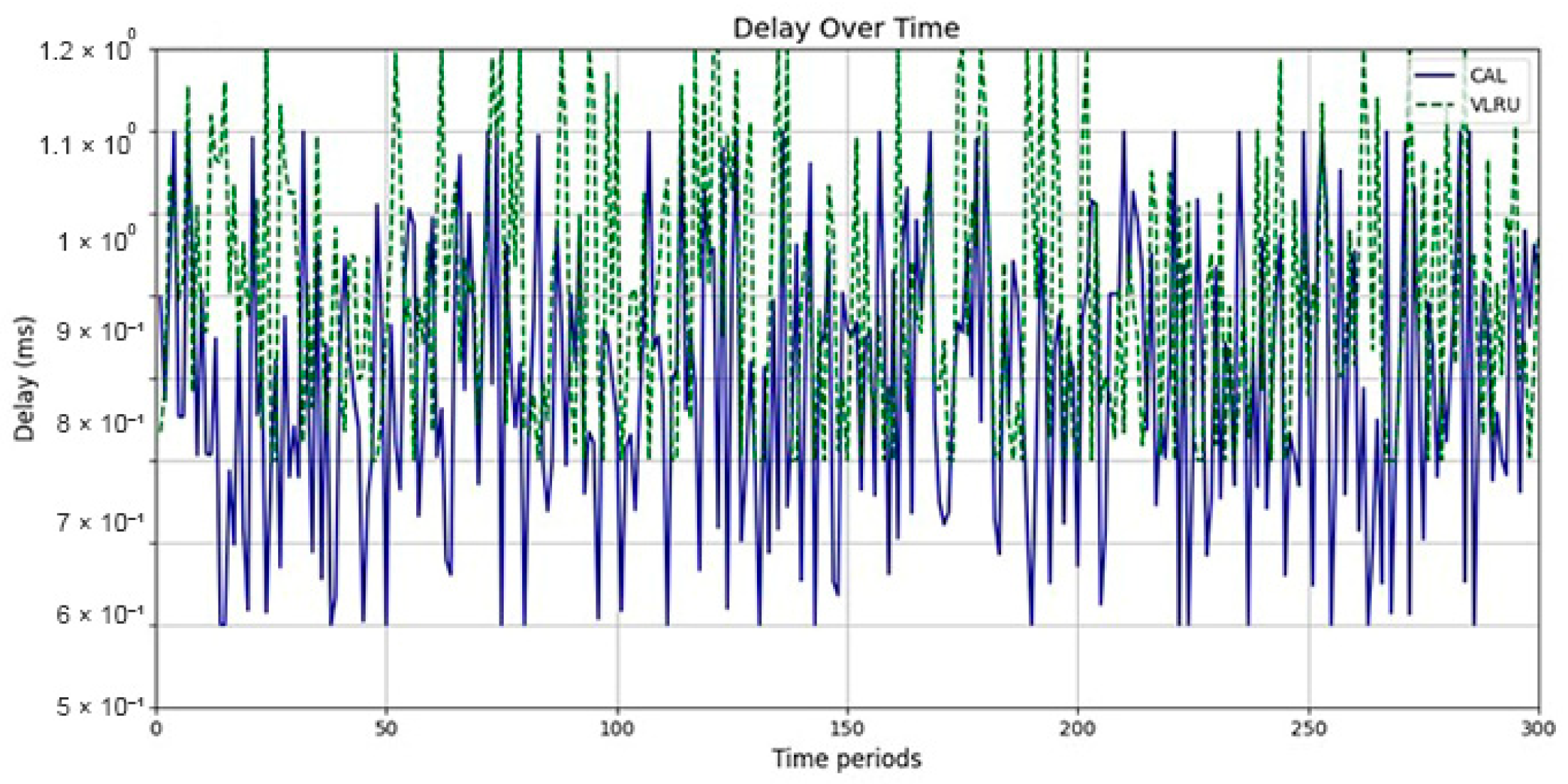

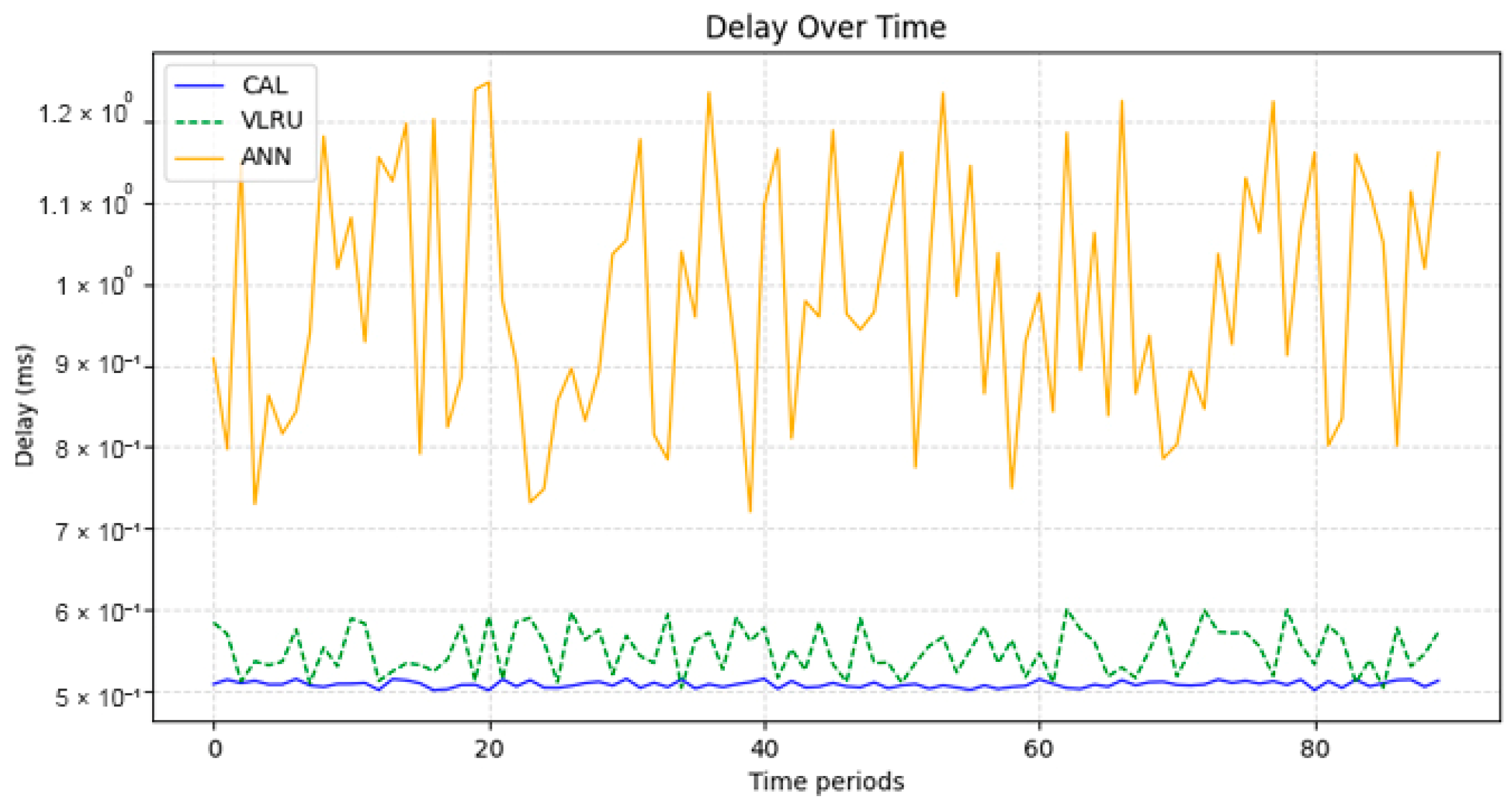

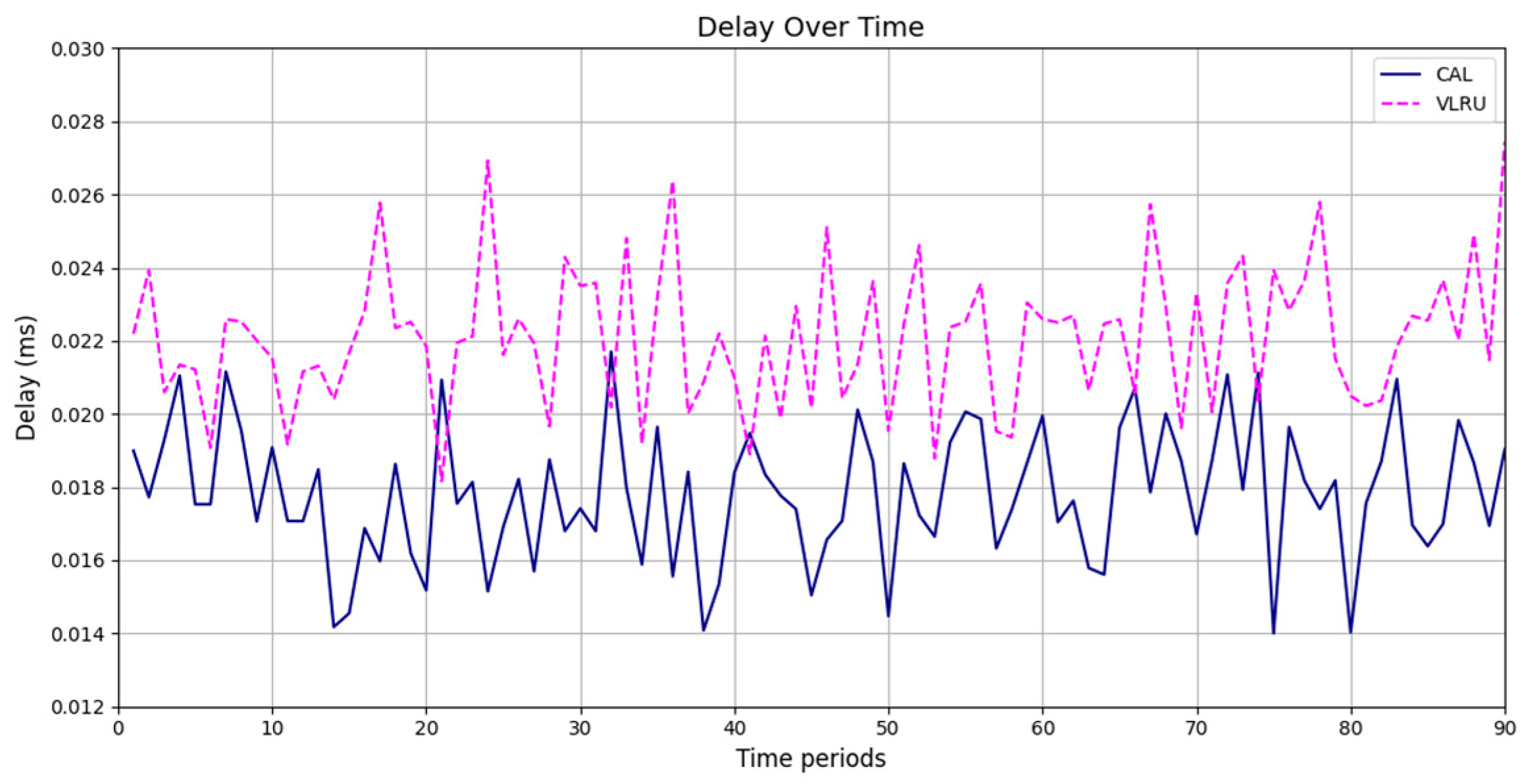

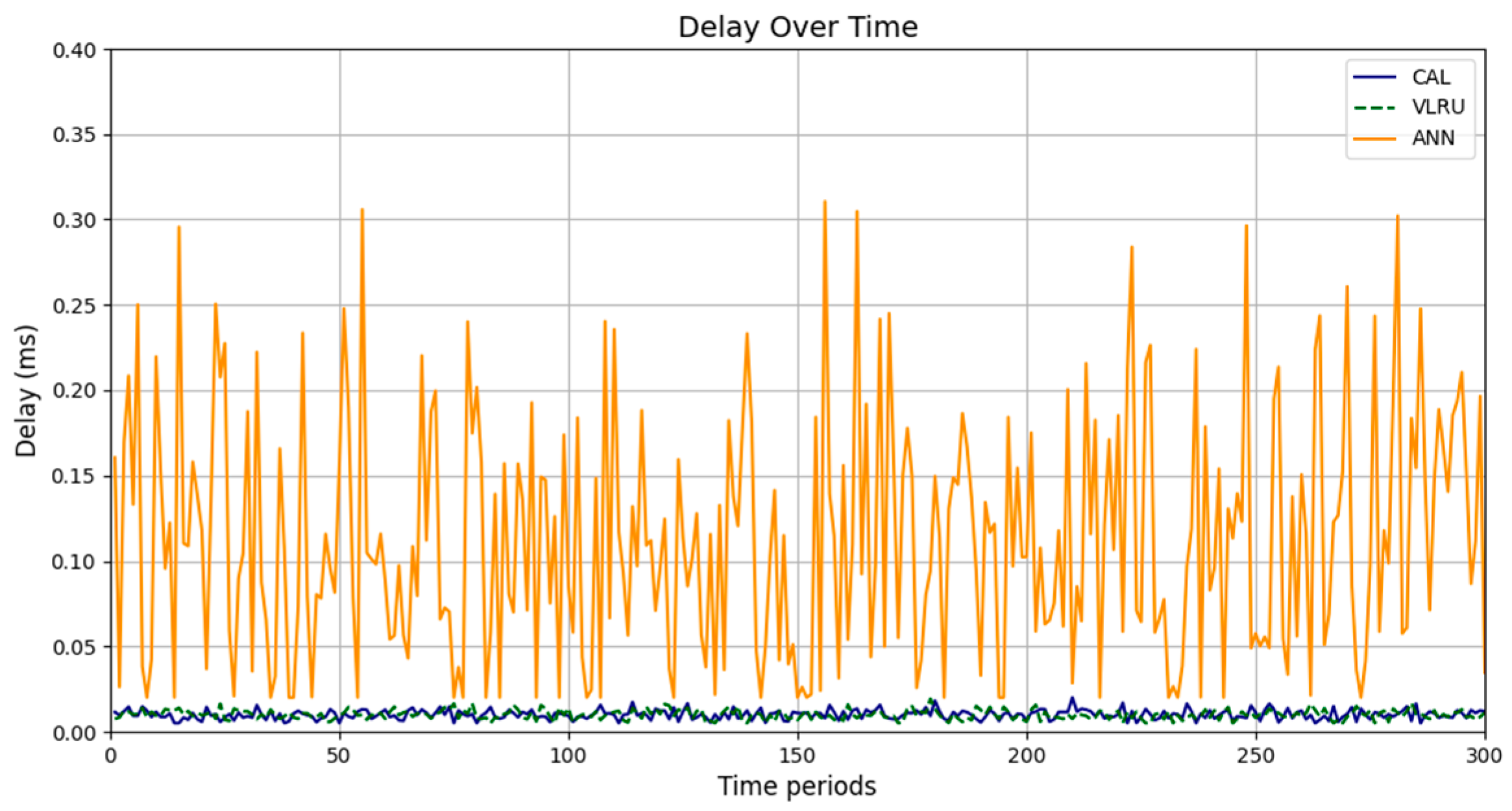

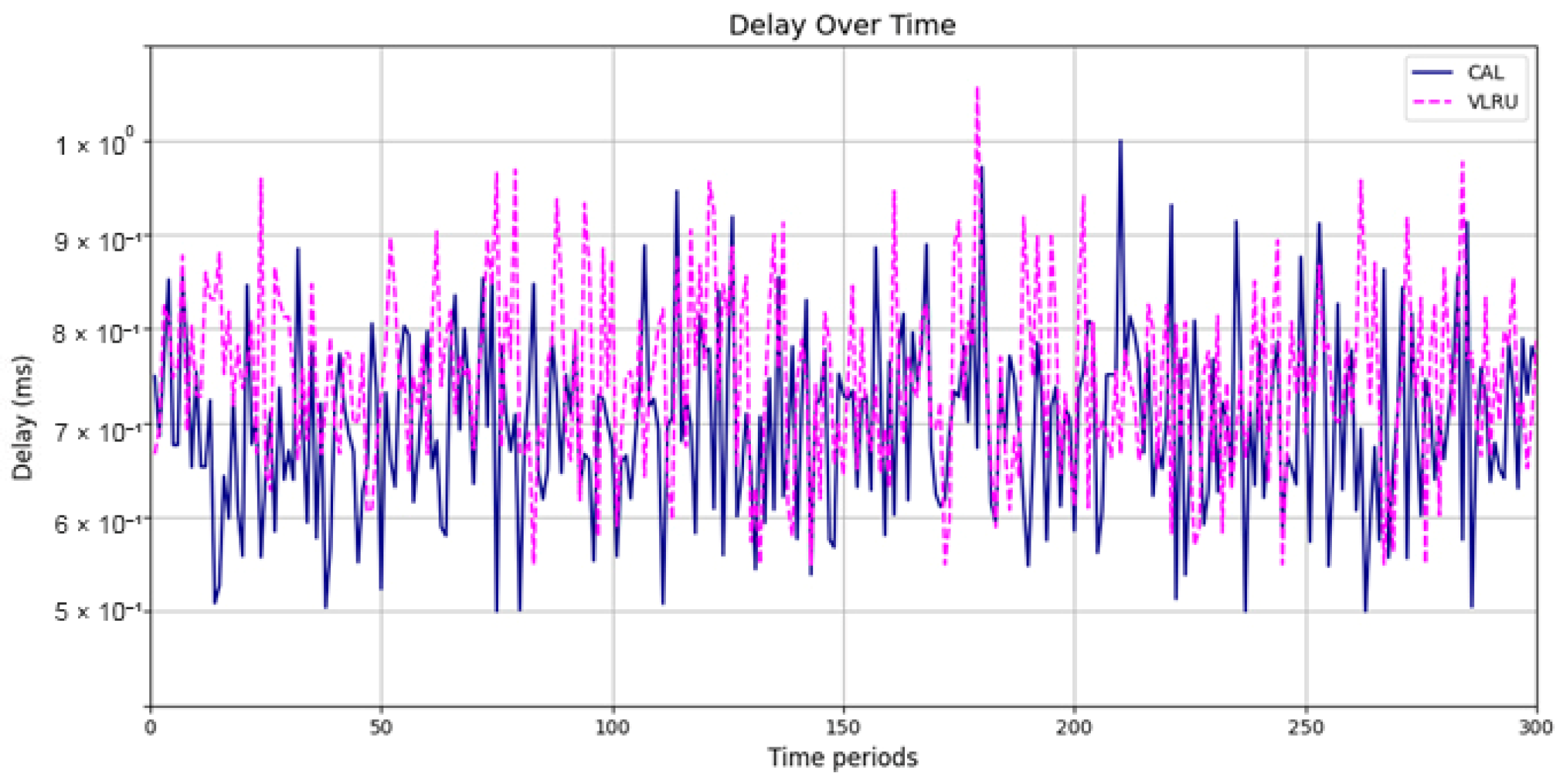

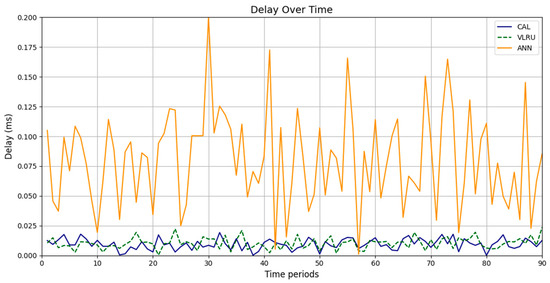

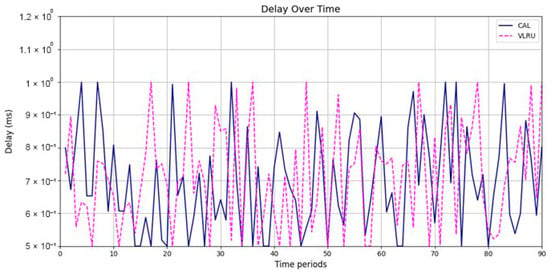

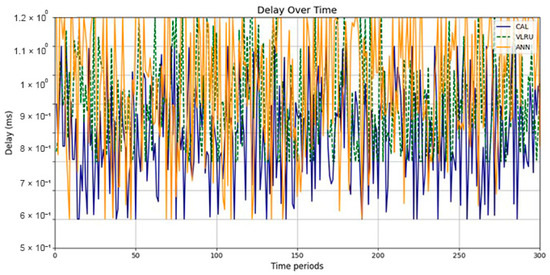

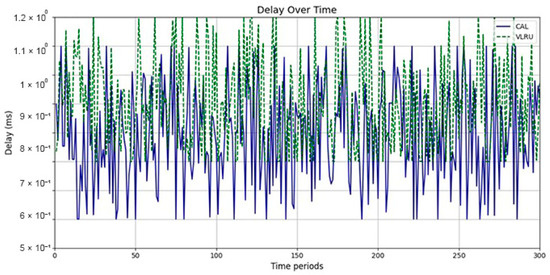

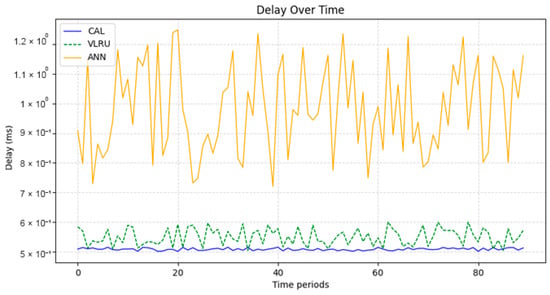

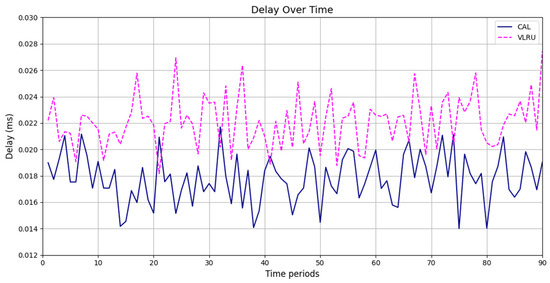

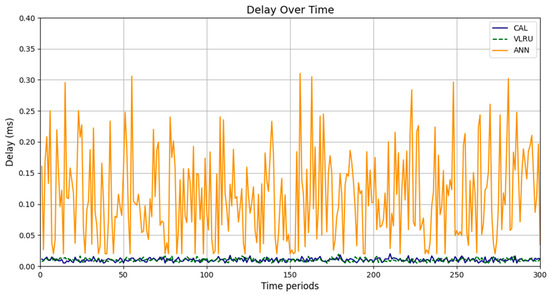

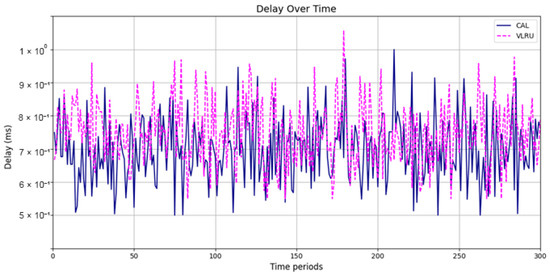

Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the network delay of the caching methods in the first simulation model with and without estimated values by the ANN. Similar experiments have been performed for the second model. Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the results of the simulations in the second model. Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the network delay imposed by the caching methods in the third simulation model with and without estimated results. The results of the simulations indicate that the proposed method has a lower network delay than the VLRU method. The results of the fourth model simulations have been shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13. The results of the fourth model simulation are similar to those of the second simulation model. The imposed performance overhead in Simulation Model 2 is like the VLRU method (shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9). Overall, the network delay imposed by the proposed method is lower than that of the VLRU method. The proposed method provides a higher cache hit ratio with lower network delay.

Figure 6.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 1.

Figure 7.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 1 without estimation.

Figure 8.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 2.

Figure 9.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 2 without prediction.

Figure 10.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 3.

Figure 11.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 3 without estimation.

Figure 12.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 4.

Figure 13.

Network delay of the caching methods in Model 4 without estimation.

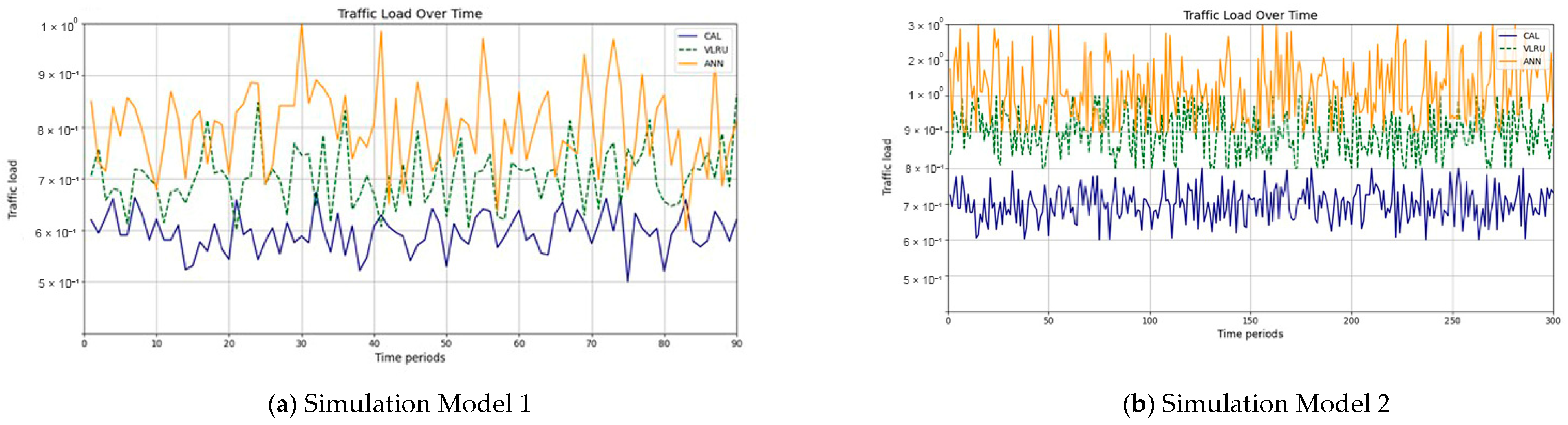

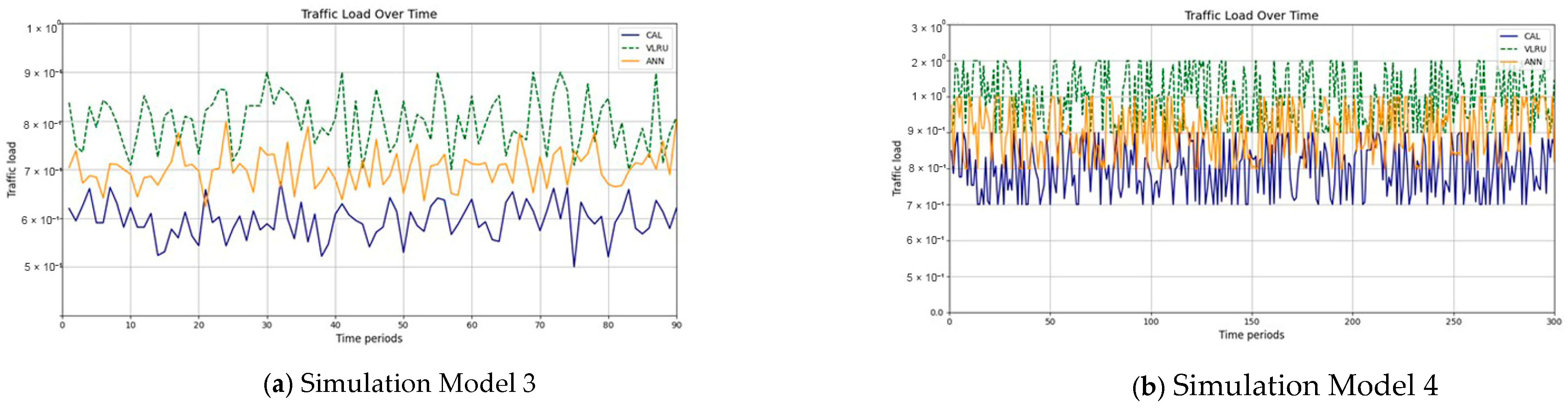

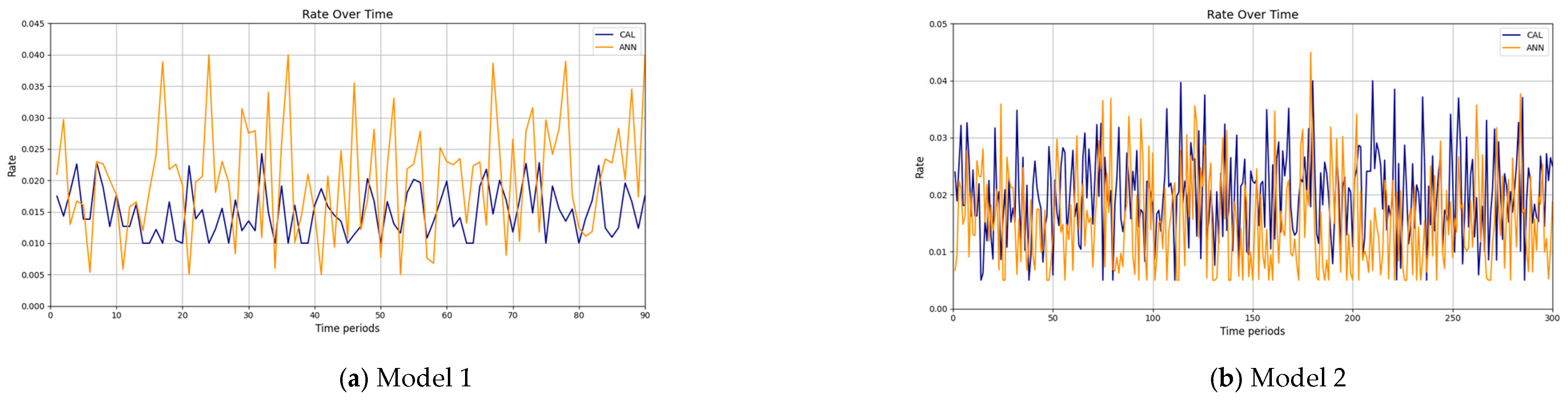

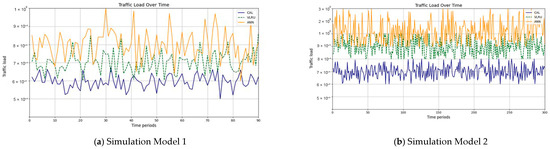

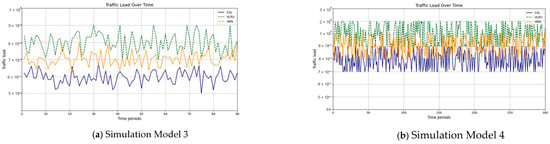

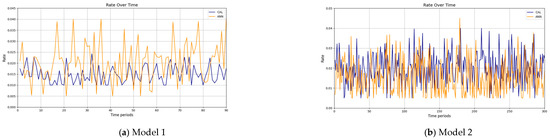

The results confirm that the proposed method considerably improves the cache hit ratio without imposing network delay; this is its main merit. Traffic load is the other criterion for the caching methods that should be considered. Figure 14 and Figure 15 show the traffic load of the proposed method and VLRU in the conducted simulations in four models. The average value of the imposed traffic load by the proposed method is lower than the VLRU method in Simulation Models 1 and 2. Figure 5 shows the traffic load of the chachi methods in Simulation Models 3 and 4. The traffic load of the proposed method is lower than that of the other method. The lower traffic load is the other merit of the proposed method over the previous methods. In all simulation models, in the worst case, the traffic load is equal to the traffic load of the VLRU method. The proposed method optimizes the traffic load since intermediate routers answer most requests. To evaluate the accuracy of the results, the results obtained by the proposed method were compared with the predicted results by the ANN. The RMSE was used according to Equation (4) to compare the predicted and the measured values. The RSME obtained for Simulation Model 1 is 0.0139 and for Model 4 is 0.0121. Figure 16 shows the values in the simulations.

Figure 14.

Traffic load of the caching methods in Models 1 and 2.

Figure 15.

Traffic load of the caching methods in Models 3 and 4.

Figure 16.

Frate values in simulation Models 1 and 4.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

Due to the instability and transience of data on the IoT and the need for a mechanism for data freshness to control the validity of cached data, in this regard, we proposed an approach for in-network caching in ICN. Calculating the data freshness in the ICN-IoT is an approach that is proposed to increase the cache hit ratio, reduce traffic load, and decrease network delay in data retrieval. In this approach, the freshness of cache data is calculated by routers and the cache decision is made based on the results. The simulation and evaluation of results represent the achievement of the expected targets of this study. The proposed approach in this research has significantly increased the cache hit ratio compared to the VLRU method by enhancing data freshness in the cache of the routers. Reducing network delays and optimizing traffic load are the other two objectives of this research. The suggested method facilitates the data exchange in communication paths between the consumer and the data producer.

Predicting requests and data freshness based on traffic information for datasets and using the expected information for cache decisions by routers is another idea that can be considered for future work. In the proposed approach of this research, the routers process and calculate the data freshness and cache decision. Due to the limited resources in the IoT, using the capabilities of Software-Defined Networking can be another idea for future works. The most common advantages of SDN are separation of the control plane from the data plane, centralized network management and traffic load, scalability, improved network control and responsiveness, reliability, and reduced network latency. If the proposed approach in this paper is combined with a software-based network, control processes will be removed from the routers and performed by the central unit and the routers will be managed centrally. Centralized network management and central control can reduce network latency by reducing the computational load of routers and speeding up the necessary processing. Utilizing different hybrid machine learning algorithms [38] instead of the ANN can improve the performance of the suggested method.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.H., B.A., O.F. and S.H.; Methodology, S.P.; Software, S.P.; Validation, B.A. and S.S.S.; Formal analysis, S.S.S.; Investigation, O.F. and S.H.; Data curation, B.A.; Writing—original draft, N.H. and S.P.; Writing—review & editing, N.H., B.A., S.S.S. and S.H.; Visualization, S.P. and S.S.S.; Supervision, B.A. and S.H.; Project administration, O.F. and S.H.; Funding acquisition, O.F. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the project “Mobility and Training for beyond 5G ecosystems (MOTOR5G)”, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Program under the Marie Skłodowska Curie Actions (MSCA) Innovative Training Network (ITN) under Grant 861219. The present work is also supported by the H2020-MSCA-RISE “Research Collaboration and Mobility for Beyond 5G Future Wireless Networks (RECOMBINE)” project with GA no. 872857.

Data Availability Statement

The data relating to the current study are available in google.drive and can be freely accessed by the following link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1TwRWsJf65-YJxS87F8FZEvABFtDd-hfG?usp=share_link, accessed on 31 October 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Alnaser, A.M.A.; Saloum, S.S.; Sharadqh, A.A.; Hatamleh, H. Optimizing Multi-Tier Scheduling and Secure Routing in Edge-Assisted Software-Defined Wireless Sensor Network Environment Using Moving Target Defense and AI Techniques. Future Internet 2024, 16, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefati, S.S.; Haq, A.U.; Craciunescu, R.; Halunga, S.; Mihovska, A.; Fratu, O. A Comprehensive Survey on Resource Management in 6G Network Based on Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 113741–113784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalli, J.S.; Hasan, M.H.; Badawi, A. Internet of things (iot): Origin, embedded technologies, smart applications and its growth in the last decade. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 91357–91382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwonwune, E.N.; Chigozie, U.C.; Ekekwe, D.A.; Nwankwo, G.C. Analysis of Secured Cloud Data Storage Model for Information. J. Softw. Eng. Appl. 2024, 17, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, S.; Azam, M.A.; Rehmani, M.H.; Loo, J. Recent advances in information-centric networking-based Internet of Things (ICN-IoT). IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 2128–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, A.; Agbaje, P.; Mitra, A.; Oseghale, E.; Nwafor, E.; Olufowobi, H. Towards named data networking technology: Emerging applications, use cases, and challenges for secure data communication. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2024, 151, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazkov, R.; Moltchanov, D.; Srikanteswara, S.; Samuylov, A.; Arrobo, G.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, H.; Himayat, N.; Spoczynski, M.; Koucheryavy, Y. Provisioning of Fog Computing over Named-Data Networking in Dynamic Wireless Mesh Systems. Sensors 2024, 24, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Deng, H.; Han, R. A Method for 5G–ICN Seamless Mobility Support Based on Router Buffered Data. Future Internet 2024, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.; Weber, S. A survey of caching policies and forwarding mechanisms in information-centric networking. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2016, 18, 2847–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henze, M.; Matzutt, R.; Hiller, J.; Mühmer, E.; Ziegeldorf, J.H.; van der Giet, J.; Wehrle, K. Complying with data handling requirements in cloud storage systems. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2020, 10, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Hassan, S.; Khan, M.K.; Guizani, M.; Ghazali, O.; Habbal, A. Caching in information-centric networking: Strategies, challenges, and future research directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 20, 1443–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Feng, Z.; Zhong, X.; Liu, F. An MTD-driven Hybrid Defense Method Against DDoS Based on Markov Game in Multi-controller SDN-enabled IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/ACM 32nd International Symposium on Quality of Service (IWQoS), Guangzhou, China, 19–21 June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sefati, S.S.; Halunga, S. Ultra-reliability and low-latency communications on the internet of things based on 5G network: Literature review, classification, and future research view. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2023, 34, e4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y.; Qin, X.; Niu, K.; Cui, S.; Shi, G.; Qin, Z.; Xu, X.; Wang, F. Intellicise wireless networks from semantic communications: A survey, research issues, and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, C.; Qiu, T.; Atiquzzaman, M.; Wu, D.O. Caching in vehicular named data networking: Architecture, schemes and future directions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2020, 22, 2378–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vural, S.; Navaratnam, P.; Wang, N.; Wang, C.; Dong, L.; Tafazolli, R. In-network caching of Internet-of-Things data. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), Sydney, Australia, 10–14 June 2014; pp. 3185–3190. [Google Scholar]

- Quevedo, J.; Corujo, D.; Aguiar, R. Consumer driven information freshness approach for content centric networking. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Communications Workshops (INFOCOM WKSHPS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 27 April–2 May 2014; pp. 482–487. [Google Scholar]

- Hail, M.A.; Amadeo, M.; Molinaro, A.; Fischer, S. Caching in named data networking for the wireless internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Recent Advances in Internet of Things (RIoT), Singapore, 7–9 April 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vural, S.; Wang, N.; Navaratnam, P.; Tafazolli, R. Caching transient data in internet content routers. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2016, 25, 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan Van, D.; Ai, Q. An efficient in-network caching decision algorithm for I nternet of things. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2018, 31, e3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddeb, M.; Dhraief, A.; Belghith, A.; Monteil, T.; Drira, K.; AlAhmadi, S. Cache freshness in named data networking for the internet of things. Comput. J. 2018, 61, 1496–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmat, H.; Din, I.U.; Almogren, A.; Altameem, A.; Khan, M.Y. Enhancing Edge-Linked Caching in Information-Centric Networking for Internet of Things with Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 154918–154932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Jain, V.K.; Gyoda, K.; Jain, S. Distance-based dynamic caching and replacement strategy in NDN-IoT networks. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Yan, T.; Hu, S. Caching Policy in Low Earth Orbit Satellite Mega-Constellation Information-Centric Networking for Internet of Things. Sensors 2024, 24, 3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, W.; Hafid, A.S.; Cherkaoui, S. Complementing IoT services using software-defined information centric networks: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 23545–23569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, V.; Saraswat, A.; Kumar, A.; Gambhir, S. Securing IoT Devices Against MITM and DoS Attacks: An Analysis. Reshaping Intell. Bus. Ind. Converg. AI IoT Cut. Edge 2024, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HS, S.; Boregowda, U. Quality-of-service-linked privileged content-caching mechanism for named data networks. Future Internet 2022, 14, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djama, A.; Djamaa, B.; Senouci, M.R. TCP/IP and ICN networking technologies for the Internet of Things: A comparative study. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Networking and Advanced Systems (ICNAS), Annaba, Algeria, 26–27 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Ahanger, A.S.; Masoodi, F.S.; Khanam, A.; Ashraf, W. Managing and Securing Information Storage in the Internet of Things. In Internet of Things Vulnerabilities and Recovery Strategies; Auerbach Publications: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 102–151. [Google Scholar]

- Sefati, S.S.; Craciunescu, R.; Arasteh, B.; Halunga, S.; Fratu, O.; Tal, I. Cybersecurity in a Scalable Smart City Framework Using Blockchain and Federated Learning for Internet of Things (IoT). Smart Cities 2024, 7, 2802–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, I.U.; Hassan, S.; Almogren, A.; Ayub, F.; Guizani, M. PUC: Packet update caching for energy efficient IoT-based information-centric networking. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 111, 634–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Y.; Mustafa, S.; Ahmad, R.W.; Maqsood, T.; Rehman, F.; Ali, J.; Rodrigues, J.J. Content caching in mobile edge computing: A survey. Clust. Comput. 2024, 27, 8817–8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamhdi, A.M. CDCA: Transparent Cache Architecture to Improve Content Delivery by Internet Service Providers. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2023, 14, 847–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefati, S.S.; Fartu, O.; Nor, A.M.; Halunga, S. Enhancing Internet of Things Security and Efficiency: Anomaly Detection via Proof of Stake Blockchain Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Osaka, Japan, 19–22 February 2024; pp. 591–595. [Google Scholar]

- Sefati, S.S.; Arasteh, B.; Halunga, S.; Fratu, O.; Bouyer, A. Meet User’s Service Requirements in Smart Cities Using Recurrent Neural Networks and Optimization Algorithm. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 22256–22269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.-Q.; Yin, Z.-Y.; Liu, Y. A hybrid SVR-BO model for predicting the soil thermal conductivity with uncertainty. Can. Geotech. J. 2023, 61, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasteh, B. A new Hybrid Model using Case-Based Reasoning and Decision Tree Methods for improving Speedup and Accuracy. In Proceedings of the Iadis International Conference, Salamanca, Spain, 18–20 February 2007. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).