Abstract

Buildings can become a significant contributor to an energy system’s resilience if they are operated in a coordinated manner to exploit their flexibility in multi-carrier energy networks. However, research and innovation activities are focused on single-carrier optimization (i.e., electricity), aiming to achieve Zero Energy Buildings, and miss the significant flexibility that buildings may offer through multi-energy coupling. In this paper, we propose to use blockchain technology and ERC-1155 tokens to digitize the heat and electrical energy flexibility of buildings, transforming them into active flexibility assets within integrated multi-energy grids, allowing them to trade both heat and electricity within community-level marketplaces. The solution increases the level of interoperability and integration of the buildings with community multi-energy grids and brings advantages from a transactive perspective. It permits digitizing multi-carrier energy using the same token and a single transaction to transfer both types of energy, processing transaction batches between the sender and receiver addresses, and holding both fungible and non-fungible tokens in smart contracts to support energy markets’ financial payments and energy transactions’ settlement. The results show the potential of our solution to support buildings in trading heat and electricity flexibility in the same market session, increasing their interoperability with energy markets while decreasing the transactional overhead and gas consumption.

1. Introduction

In Europe, buildings consume about 40% of the energy generated and are thus seen as essential elements for energy transition and may be a significant contributor to the resilience and flexibility of our energy system [1]. The recent developments in renewable energy technologies, batteries, and heat pumps make possible the transformation and retrofit of the buildings into flexible prosumers and active contributors to the management operations of the energy grid [2,3]. In parallel, the advancement in ICT technologies and their integration into energy grids enable the decentralization and digitization of energy resources, changing the energy network’s operation towards an integrated energy system with bi-directional energy and information flows [3]. This requires high levels of interconnection among heat and electricity networks, buildings, and other sectors of the economy to increase the flexibility and efficiency of the entire energy system [4]. However, research and innovation activities around buildings are mostly focused on single-carrier optimization (i.e., electricity), aiming to achieve higher levels of renewable integration with the aim to achieve Zero Energy Buildings [5]. However, these limited solutions focused exclusively on renewable integration are not able to guarantee the zero-balance target and miss the buildings’ flexibility that may be provided to the energy system to generate new revenue streams for operators or residents [6,7].

In this context, buildings can play a significant role if they are operated in a coordinated manner as smart flexible prosumers integrated with the energy system, providing valuable services to the electrical and thermal grids [8]. On one side, the buildings can use their electrical flexible loads (e.g., consumer devices, batteries, heating and cooking loads, and renewable generation) for electricity trading and demand response services, creating a positive environmental impact as well as commercial value and, at the same time, they can trade and provide their residual heat to the thermal grids, leveraging the heat pumps to increase its quality. In this direction, the smart building concept has been introduced to ensure technological approaches for closer to real-time control and interaction with end users, converging towards decentralized building level coordination with distributed multi-carrier energy networks [9,10]. In parallel, the advent of blockchain technology is changing the energy sector, from the integration of renewable energy sources to smart energy grids and smart-ready buildings and peer-to-peer energy trading [11,12]. It offers opportunities to digitize the energy of different carriers using tokenization and paving the way to decentralized control of electricity grids in synergy with other energy carriers and the delivery of cross-sectorial integrated services.

In our vision, the energy flexibility of non-grid-owned assets should be digitized and made tractable on different energy markets. Blockchain offers integration opportunities for multi-carrier energy buildings to digitize their flexibility using tokenization and decentralized coordinated control via smart contracts, which may transform them into active flexibility assets at the interplay of multi-energy networks able to trade energy on both heat and electrical markets [13].

In this paper, we consider a trading mechanism designed to work in an integrated multi-energy system, where electricity and heat are traded within an energy community [14]. Most of the existing literature on P2P energy trading addresses electricity and the lack of cross-energy carrier integration relevant to the buildings sector. The heat trading is focused on buildings that may generate heat using their heat pumps to create hot water, which is then fed into a shared heat grid within the community. If there is no heat energy storage in the community, the building’s heat generation can be traded with other community members. Because the amount of heat can be adjusted based on the comfort preferences of its residents, there is some flexibility in the heat generation levels. This flexibility can be used to increase or decrease the amount of heat produced by a building and injected into the community heat grid. The amount of heat generation from each building is tokenized and made available in the heat market setup. This means that the building owners can sell their excess heat to others who need it or purchase additional heat when they require it.

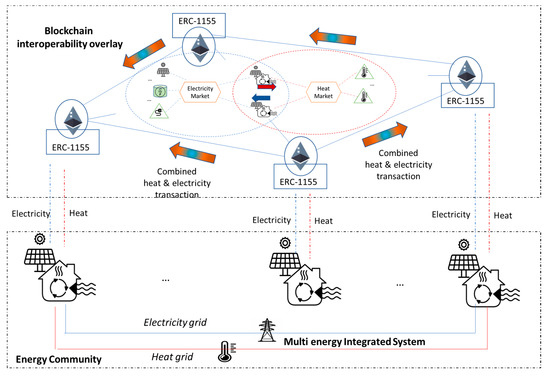

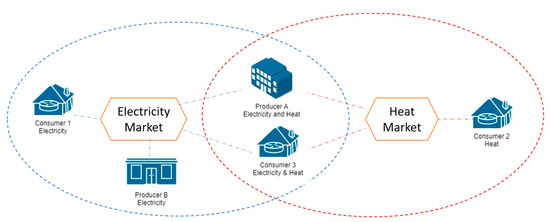

We propose the use of blockchain, smart contracts, and multi-token standards to allow buildings to digitize their flexibility from electricity and heat energy carriers and to trade it in multi-energy markets (see Figure 1). This will not only enable them to play a more active role in the energy system owing to better integration and to obtain new revenue streams thanks to higher levels of flexibility, but will also bring advantages from a transaction perspective. Blockchain provides ideal support for an immutable, tamper-proof public ledger and the trading of digital assets, while ERC-1155 can be adapted for digitizing energy regardless of the type. Thus, one building prosumer that produces both electricity and heat will have transactions with others in different markets trading both electricity and heat. Each matched pair of prosumers will only require a single transaction to transfer both types of energy. The adoption of ERC-1155 for energy trading allows a smart contract to hold tokens of different types, including fungible (money-like), non-fungible (individual), and semi-fungible (one of a specific bunch with the same/similar scope). In this way, we will use fungible tokens that can act as currency in electricity and heat markets to perform financial transactions, while the non-fungible tokens are used for digitizing the electricity and heat flexibility produced by a building. Finally, the solution paves the way for processing batches of energy transactions in the ERC-1155 protocol, supporting the transfer of multiple independent tokens between the addresses of the sender and receiver.

Figure 1.

Building energy flexibility trading using our blockchain and ERC-1155 solution.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the related work on buildings’ energy interoperability and blockchain tokenization, Section 3 describes our solution for building flexibility digitization and trading on heat and electricity markets, Section 4 and Section 5 present the evaluation results and discuss the advantages related to the reduction in the number of transactions and decrease in gas consumption, while Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Buildings are considered as central elements to the success of the energy transition towards an integrated renewable energy system in Europe [1]. Their flexibility is a key asset in achieving a reliable, decarbonized, and cost-effective energy system [2]. The literature study was organized into three categories: (i) buildings’ flexibility within an integrated multi-energy system, (ii) blockchain and tokenization solutions for peer-to-peer energy trading of buildings, and finally (iii) the use of tokenization in cross-energy sectors.

In the first category, a few approaches in the literature deal with the potential contribution of buildings’ heat and electricity flexibility to combined energy system management. In [15], the authors propose the concept of integrated demand response (DR), where residential consumers can use their flexibility not only by reducing off-peak electricity consumption, but also by converting the electricity to heat or gas. Salo et al. argue that demand response for district heating has great potential [16] and investigate optimal strategies from the district heating operator point. They conclude that such strategies have a slight positive effect on costs and emissions at the district level of buildings if heat storage such as hot water tanks is not available. Yuan et al. analyze the potential of district heating, targeting swimming pools and halls, which pose significant heat demands and larger heat storage capacity [17]. The authors create a simulation model and propose a rule-based algorithm that uses the dynamic district heat price as an optimization factor to take advantage of buildings in heat-oriented DR services. In [18], the authors study and evaluate a demand response model for central heating systems of apartment buildings. It considers weather forecasts, indoor temperatures, and decreases in space heating temperatures when the demand for domestic hot water is at a high level. The overall objective is to cut or shift the peaks in gas consumption, thus levelling the heat demand to a flatter profile. Suhonen et al. analyze the energy- and cost-saving potential of demand response in district heating networks from Germany and Finland [19]. A real-time pricing-based strategy is selected to calculate the hourly indoor temperature set points, reporting energy savings of between 7 and 8%. In [20], the integration of a predictive DR control for residential buildings that feature heat pumps and on-site energy generation is proposed. The prediction process outputs the heating demand for the next 24 h and is implemented by means of a hybrid wavelet transformation and a dynamic neural network. Similarly, an integrated model for optimal scheduling of cooling, heating, power, gas, and water sources in a multi-energy microgrid is proposed in [21]. Demand-side services are proposed to allow the building and operators to participate in the power, heat, and gas markets using energy conversion facilities. Yao et al. focus on the problem of the imbalance between supply and demand and propose a model of integrated electrical, heating, natural gas, and water distribution systems for participating in demand response programs [22]. A price-based strategy is formulated for the electrical, gas, and water loads that benefits from a two-stage robust optimization technique to achieve optimal scheduling of resources. The multi-energy microgrid (heat–power–gas) management problem is tackled by developing models for converting energy carriers and changing the energy consumption pattern for a given period [23]. A thorough review of the potential power-to-heat DR for multi-energy networks is presented in [24], arguing that most of the research should focus on energy markets and power-to-heat demand response, requiring the refinement of economic and policy frameworks.

In the second category, many solutions advocate the adoption of blockchain technology for the implementation of decentralized demand response programs via peer-to-peer energy trading [25]. However, most of them are focused on electricity and fail to address other energy carriers. The blockchain-based digitization via tokenization could unlock more small-scale energy flexibility while considering the buildings’ operational constraints, households’ preferences, and social enablers enacting the compensation of flexibility shifting via remuneration from P2P trading [13,26]. Tokenization in blockchain refers to the ability to associate a specific asset with it—in this case, the energy or the flexibility for producing and consuming energy. In [27], the design considered two types of tokens, monetary value through fungible tokens and energy with certification through non-fungible tokens. They focus on the entire token lifecycle management, from creating and bidding up to transferring and redeeming. In [28], the authors showed the possibility of creating immutable snapshots for token balance query based on an extension of OpenZeppelin’s ERC-20 (for fungible tokens) and ERC-721 (for non-fungible tokens). Others consider the case of locking fungible tokens for trading in peer-to-peer energy, trading up to the point of transaction settlement using locks in certain predefined conditions [29]. Munoz et al. use Zap to represent the non-fungible energy tokens, with users being billed based on consumption with the possibility for Zap’s metadata to be offloaded off-chain [30]. In [31,32], payment schemes for trading renewable energy are analyzed from two distinct perspectives: the reward of the energy producers and the cost of energy consumption. Certain requirements are identified to ensure that the blockchain is not used maliciously, such as incentives to use one’s own energy before buying from the grid. The multi-stage energy optimization and retrofitting solution [33] deals with old buildings that could be retrofitted for better energy consumption and production. In [34], the authors focus on the interoperability between blockchains, named cross-chain. The solutions range from atomic swaps, where tokens are exchanged at the same time, and cross-chain messaging, where values can be read and written between blockchains, to state pining, where the hash of a particular block is pinned to another blockchain. In [35], X-as-a-service represents the value to society, which needs to mirror the reality on the blockchain, where X can stand for security, integrity, or some other value. The proposed architecture uses private authorities and implies an onion-layered system where each layer ensures a value. Zuo et al. consider the definition of a renewable energy certificate that has as a unit 1 MWh of green energy [36]. A renewable energy token is issued on Ethereum when the energy is fed to the grid, and the energy producer can trade it either against its own consumption or for profit.

In the third category, blockchain and tokenization are successfully used in cross-energy sectors to reinforce trust. The idea of blockchain as a trust protocol between the real and digital world is introduced in [37]. As tokens are created by smart contracts, an external audit is recommended for trust, which can be implemented with the help of IoT devices. In [38], the authors focus on the circular economy and propose a framework for the digitalization of assets, where identity and ownership are identifiable and obey contracts involving a transparent token exchange. In [39], the digitalization of assets is carried out using the ERC-T(token) protocol, which replicates an ETF (exchange-traded fund). This differs from a fungible ERC-20 and non-fungible ERC-721 by not allowing reverse transfers. Some authors have considered the splitting of the ownership of the NFT token and the risk it poses to an economic system over any over-the-counter security [40,41]. Blockchain tokenization and certification are used in organic agriculture [42]; to avoid counterfeit products with a protected designation of origin, e.g., for wine [43]; and for geo-energy sources in the case of drilling and trading rocks [44]. Other frameworks for ensuring trust through certificates for the entire supply chain were discussed in [45] for tokenizing all required data for wood volume, using the evidence, verifiability, enforceability framework. To create a multi-component logging blockchain [46], the authors propose an architecture based on a directed acyclic graph and hybrid tokens for multiple products of the same company. The graph used represents the information in chronological order from the creation of tokens and then moving forward.

Most state-of-the-art solutions address the digitization of buildings’ energy using blockchain and tokens for peer-to-peer trading. However, these solutions tend to focus primarily on electricity and do not address other energy carriers such as heat and potential conversions for multi-energy systems’ integration. Some consider ERC-1155 for energy digitization and trading using semi-fungible models, but are focused on analyzing the tradeoffs among traceability and costs [30]. To the best of our knowledge, none of the current state-of-the-art solutions in the energy sector consider the digitization of thermal and electrical energy using ERC-1155 tokens. Our solution allows smart contracts to hold tokens of different types and execute simultaneous trades in heat and electricity markets, enabling buildings to actively participate in integrated multi-energy grids within the same energy community. Moreover, it enables the processing of batches of energy transactions supporting the transfer of multiple independent tokens between the addresses of the sender and receiver, resulting in a decrease in the transactional throughput of peer-to-peer energy markets as well as the associated costs.

3. Materials and Methods

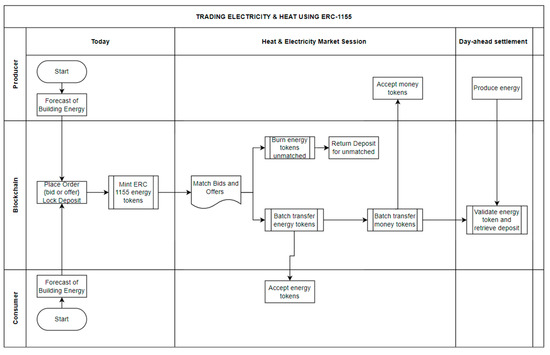

We define our solution for trading building multi-carrier energy flexibility by minting and integrating ERC-1155 electrical and heat tokens with P2P energy flexibility markets (see Figure 2), such as the one described in [26].

Figure 2.

Trading different types of energy using ERC-1155 and smart contracts.

The buildings forecast of electricity and heat for the next day is used to generate heat and electricity orders (i.e., either bids or offers). They are placed in the flexibility market session and, for each order, a deposit with fungible tokens will be locked to ensure that everyone can afford and pay for their orders. The building producing electricity and heat places an offer, and non-fungible tokens representing this promised amount of energy for each hour and energy type will be minted. After a session is closed, the matching is performed. Based on the result of the matching, some orders will be matched completely, matched partially, or unmatched. For all of the producer’s orders, for token quantities that are unmatched, the corresponding tokens will be burnt and the deposits unlocked. In the case of matched orders, the settlement will take care of transferring the energy tokens and the transfer of currency tokens to the building that produced the heat or electricity. As the energy tokens are ‘promise tokens’—that is, the energy was not yet produced when the token was minted—a system is required to attach an energy certificate that will allow the producer to retrieve its deposit at the reference price when it produces the energy it promised.

An order submitted by a building in the market session is comprised of an order ID, for identification purposes, as well as the order type, prosumer address, and the three same-length arrays (see Algorithm 1): token IDs array (i.e., defining energy type and moment of the day), quantities array, and prices array.

| Algorithm 1 Market session order structure |

| 1. struct Order1155 { |

| 2. bytes32 id; |

| 3. orderType: {OFFER, BID} |

| 4. prosumerAddress: buildingA, |

| 5. tokenIds: [MORNING_ELECTRICTY_TOKEN, MORNING_HEAT_TOKEN, |

| EVENING_ELECTRICITY_TOKEN, EVENING_HEAT_TOKEN], |

| 6. quantities: […], |

| 7. prices: […] |

| 8. } |

Our design embraces two concepts. First, the ability to differentiate between different hours of the day and energy types using the higher part of the 256 bits, and second, the ability to place orders with different prices for different hours.

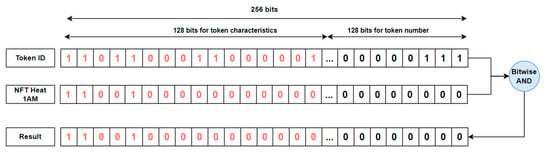

To better understand how ERC-1155 can better serve our purpose, we combined the non-fungible tokens with additional meaning stored in the token ID. In our approach, we used masking and C/C++ bitwise operators [47] to check the properties of the token (see Figure 3). The operators are performed on uint 256 bits for the token ID.

Figure 3.

Check hour and energy type digitized by the token.

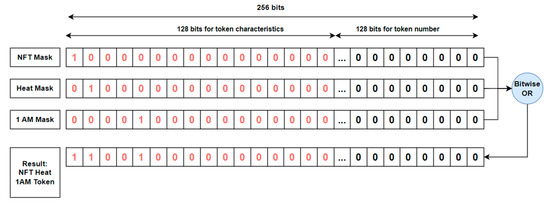

We use the higher half bits of the token ID for token characteristics of the token, such as fungible or non-fungible, type of energy digitized (i.e., either heat or electricity), and the corresponding hour. As depicted in Figure 4, using different masks, we can check that the token in the example is not fungible and depicts a token for 1 a.m. of the energy type heat.

Figure 4.

Using masks to determine the properties of an energy token.

For checking multiple properties, we create different masks (one per property) and perform a bitwise OR operation. In this way, all true conditions are passed to the final mask (see Table 1). When we want to check against the mask, we perform the bitwise AND operation to ensure that everything contained in the mask is also found in the checked token. This approach allows high flexibility regarding energy digitized by a building as tokens that can be submitted to a market session.

Table 1.

Masks for determining token properties.

For implementing the trading process, an interface named GridOperable was designed. It contains a function for registering an order and one for applying the settlement. Using an interface, each smart contract that is ERC-1155 compliant in our model can decide how a specific trading scenario should be handled.

The advantage of this approach is that, by implementing the interface, a building can define and submit a single order using the function described in Algorithm 2, by aggregating for each hour of the day tokens of different energy types.

| Algorithm 2 Function for registering heat or electricity orders |

| 1. function registerOrder(GridOperableLibrary.Order1155 memory order) external override returns (bytes32){ |

| 2. … |

| 3. If (order. orderType==GridOperableLibrary.OrderType.OFFER){ |

| 4. for (uint i;i< order.tokenIds.length;i++){ |

| 5. _mint (order.prosumerAddress, order.tokenIds[i], order.quantities[i]); |

| 6. } |

| 7. } |

| 8. … |

| 9. order.id = bytes32(orderSize++); |

| 10. _orders[order.id] = order; |

| 11. for (uint k =0; k<order.involvedMarkets.length;k++) { |

| 12. _marketsTypeOrders [GridOperableLibrary.MarketSessionType1155(k)][or |

| der.orderSide].push(order.id);} |

| 13. emit OrderRegistered(order.prosumerAddress,order.id); |

| 14. return order.id; |

| 15. } |

Because our work represents the energy in token format, in our design, we also mint non-fungible energy tokens when a building places them in an offer of energy (see Algorithm 2, lines 3–7). By doing so, once the settlement is reached, the producer can easily transfer the energy tokens to the buyer. The order will be added to the orders’ mapping and emit a blockchain event (see lines 9–14). For ease of retrieval, the order will be added to all relevant markets based on the order type. This approach allows for the overlap between sessions regarding an order that contains multiple types of energies.

As we want a flexible system, different properties of the market sessions are delegated to smart contract functions. Algorithm 3 shows an example for the reference price property of the market session. The smart contract function will check all session types (i.e., heat or electricity) and, once one is identified as relevant based on the token type information at hand, it will delegate it to the appropriate address.

| Algorithm 3 Determine the market session properties based on the token type. |

| 1. function determineReferencePrice (uint tokenId) public returns (uint) { |

| 2. … |

| 3. If (checkMask(tokenId, |

| 4. marketSessionMap [GridOperableLibrary.MarketSessionType1155(i)].tokenMask)){ |

| 5. Return AssetMarketSession1155(marketSessionMap [MarketSessionType1155(i)]. |

| 6. marketSession).getReferencePrice(); |

| 7. … |

| 8. } |

To participate in energy trading, one needs to be registered as a prosumer. This is accomplished by calling the smart contract function from Algorithm 4 with the prosumer certification and payment proof for deposit—in either case, for consuming or promising energy. This function will then mint the fungible tokens based on ERC-1155 for this prosumer.

| Algorithm 4 Using ERC-1155 for creating tokens for energy payment |

| 1. function registerProsumer(address prosumerAddress, address prosumerCertificate, |

| uint amount) returns (bool){ |

| 2. if (isValidCertificate(prosumerAddress,prosumerCertificate)) |

| 3. if (checkDeposit(prosumerAddress, amount)){ |

| 4. _mint(prosumerAddress, MONEY_TOKEN, amount); return true;} |

| 5. return false; |

| 6. } |

Finally, the token bits can be used to determine the type of market (electricity or heat) on which the building energy order needs to be submitted (see Algorithm 5).

| Algorithm 5 Using the token to determine the market session for placing a building order |

| 1. function determineInvolvedMarkets (uint[] memory tokenIds) public |

| returns (uint [] memory) { |

| 2. … |

| 3. for (uint i = 0; i< tokenIds.length;i++){ |

| 4. for (int j = 0; j< size;j++) { |

| 5. if(checkMask(tokenIds[i], marketSessionMap [GridOperableLibrary. |

| MarketSessionType1155(j)].tokenMask)){ |

| 6. GridOperableLibrary.MarketSessionType1155 typeSession = |

| GridOperableLibrary.MarketSessionType1155(j); |

| 7. Session memory session = marketSessionMap[typeSession]; |

| 8. involvedMarkets[counter] =uint(session.sessionType); |

| 9. } |

| 10. } |

| 11. } |

| 12. return involvedMarkets |

| 13. } |

To facilitate the integration of different algorithms for matching of different markets, we store the newly created orders in a mapping that has as key the market session type (e.g., heat or electricity) and as value a secondary mapping (see Algorithm 6). The secondary market has as key the order side (buy or sell) and as value the array of order IDs. In this way, it is possible to retrieve all orders for a session market and side.

| Algorithm 6 ERC-1155 orders and market type |

| 1. mapping (GridOperableLibrary.MarketSessionType1155 |

| 2. =>mapping(GridOperableLibrary.OrderSide=>bytes32[])) internal _marketsTypeOrders; |

| 3. enum MarketSessionType1155 {HEAT, ELECTRICITY} |

By matching the bids and offers, registered trades are created. Each trade requires the order IDs for a buyer and a seller and their addresses, as well as an array of token IDs, quantities, and prices for energy flexibility (see Algorithm 7).

| Algorithm 7 ERC-1155 flexibility trade structure |

| 1. struct Trade1155 { |

| 2. bytes32 id; |

| 3. bytes32 buyOrderId; |

| 4. bytes32 sellOrderId; |

| 5. address payable prosumerBuyingAddress; |

| 6. address payable prosumerSellingAddress; |

| 7. uint[] energyTokenIds; |

| 8. uint[] quantities; |

| 9. uint[] prices; |

| 10. } |

In the case of other protocols such as ERC-20, we would have multiple trades independently for each session. The ERC-1155 protocol instead allows for multiple independent tokens to be transferred in batches between the same sender and receiver addresses. This approach allows us to have all energy token transfers between partners as well as the fungible currency transfer carried out once with the total due, rather than having to do multiple transfers. Algorithm 8 shows the settlement process that takes, as a parameter, a list of trades and, for each trade with the same buyer and seller addresses, a single batch operation will be performed to transfer all energy tokens, in their respective quantities (lines 6–9). The fungible currency transfer is also carried out once with the total due, rather than having multiple transactions between the same partners (once for each session market). The balances change as energy tokens are transferred, and the money token balance reflects this change for both the buyer and seller.

| Algorithm 8 Transaction settlement and using ERC-1155 batch transactions |

| 1. function settle ( GridOperableLibrary.Trade1155[] memory trades) external override { |

| 2. for (uint i;i<trades.length; i++){ |

| 3. GridOperableLibrary.Trade1155 memory trade = trades[i]; |

| 4. GridOperableLibrary.Order1155 memory sellingOrder = _orders[trade.sellOrderId]; |

| 5. GridOperableLibrary.Order1155 memory buyingOrder = _orders[trade.buyOrderId]; |

| 6. bytes memory y = abi.encode(0); |

| 7. this.safeBatchTransferFrom(trade.prosumerSellingAddress, |

| trade.prosumerBuyingAddress,trade.energyTokenIds, trade.quantities, y); |

| 8. this.safeTransferFrom(trade.prosumerBuyingAddress, |

| trade.prosumerSellingAddress, MONEY_TOKEN, trade.totalDue, y); |

| 9. } |

| 10. } |

4. Evaluation Results

In this section, we evaluate the above ERC-1155 solution in the context of the decentralized peer-to-peer energy flexibility markets for heat and electricity that we have reported on in [26]. The smart contracts are implemented in Solidity programming language and were tested using the Ethereum platform in the Remix IDE. This approach allows testing on multiple chains (already available in the Remix workspace). In our evaluation, the Remix VM (Merge) environment chain was used to run all scenarios because of its sandbox blockchain properties, meaning that, each time the blockchain is reloaded, it is in the same state as the last time it was started. By adhering to this approach and this environment, each scenario run can be compared to the same state of the blockchain, and any further developments can be compared directly.

We aim to evaluate our solution effectiveness in managing both the heat and electricity orders of building prosumers, creation of heterogenous trades, and processing in batches. We constructed the trading scenario using the different types of electricity and heat prosumers presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Buildings’ heat and electricity trading scenario.

The heat and electricity producers can place their entire orders through a single transaction without needing a fixed price and the energy tokens will be minted. Table 2 shows the ERC-1155 encoding of flexibility orders for both heat and electricity in our scenario using encoding with different token IDs.

Table 2.

ERC1155 tokens for producers’ orders of heat and electricity.

As can be seen in Table 2, at each hour, the flexibility order is encoded by a different token. Algorithm 9 shows an encoding example for the orders placed by prosumers as buyers and sellers.

| Algorithm 9 Flexibility bids and offers using ERC-115. |

| let order1 = { |

| orderSide: OFFER, |

| prosumerAddress: producerA, |

| tokenIds: [MORNING_ELECTRICTY_TOKEN, MORNING_HEAT_TOKEN, |

| EVENING_ELECTRICITY_TOKEN, EVENING_HEAT_TOKEN], |

| quantities: [100,100,100,200], |

| prices: [10,15,10,15] } |

| let order2 = { |

| orderSide: BID, |

| prosumerAddress: Consumer1, |

| tokenIds: [MORNING_ELECTRICTY_TOKEN, EVENING_ELECTRICITY_TOKEN], |

| quantities: [10,10], |

| prices: [15, 15] } |

Upon submitting orders, the consumers will lock fungible tokens as a guarantee of their solvability during settlement. They are determined considering the amount of heat or electricity energy submitted in the bid and the reference price. Table 3 shows the consumers’ orders and their deposits for a market session in our scenario.

Table 3.

Consumer orders and deposits of ERC1155 tokens and fungible tokens.

Algorithm 10 shows examples of successful minting of heat and electricity tokens and the orders’ registration.

| Algorithm 10 Example of ERC-1155 tokens’ mining and order registration results |

| ERC1155.TransferSingle( |

| _operator: <indexed> 0x627306090abaB3A6e1400e9345bC60c78a8BEf57 (type: address), |

| _from: <indexed> 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000 (type: address), |

| _to: <indexed> 0x627306090abaB3A6e1400e9345bC60c78a8BEf57 (type: address), |

| _id: MORNING_ELECTRICITY_TOKEN (type: uint256), |

| _value: 70 (type: uint256) |

| ) |

| ERC1155.TransferSingle( |

| _operator: <indexed> 0x627306090abaB3A6e1400e9345bC60c78a8BEf57 (type: address), |

| _from: <indexed> 0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000 (type: address), |

| _to: <indexed> 0x627306090abaB3A6e1400e9345bC60c78a8BEf57 (type: address), |

| _id: MORNING_HEAT_TOKEN (type: uint256), |

| _value: 80 (type: uint256) |

| ) |

Table 4 shows the peer-to-peer flexibility trades created. The number of trades is minimized because the ERC-1155 protocol allows for multiple independent tokens to be transferred in batches between the same sender and receiver address. Moreover, it allows the grouping and processing of heat and electricity tokens in single transactions.

Table 4.

ERC-1155 trade generation in batches.

Each trade will have a single buyer and seller order. Because, in a single order, we can have multiple types of energy tokens, if the buyer and seller are matched, one batch operation will be performed to transfer both types of energies—meaning all of the energy token IDs and their respective quantities. Considering the trades from Table 4, Algorithm 11 shows the batch trade structure between Producer A and Consumer 3 that aggregates multiple trades at different hours and energy types.

| Algorithm 11 Batch trade processing between Producer A and Consumer 3 |

| let trade1 = { |

| buyOrderId: ’0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000005’, |

| sellOrderId: ’0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001’, |

| prosumerBuyingAddress: client3, |

| prosumerSellingAddress: producer1, |

| energyTokenIds: [MORNING_HEAT_TOKEN, EVENING_HEAT_TOKEN, |

| EVENING_ELECTRICITY_TOKEN], |

| quantities: [10,10,10], |

| prices: [15,15,10] |

| } |

Our solution allows for having all energy tokens as well as the fungible currency transfer carried out once with the total due, rather than having multiple transfers between the same partners (once for each session market). As a result, it provides better support for building prosumers in trading heat and electricity flexibility at the same time, increasing their interoperability with energy markets.

5. Discussion

In this section, we discuss the benefits of our solution in terms of reducing the number of transactions, as well as decreasing the amount of gas needed to execute those transactions in peer-to-peer energy trading. As detailed in the previous sections, our solution makes the process of trading heat and electricity among buildings connected to a shared multi-energy grid within a community more efficient and cost-effective by enabling smart contracts to hold tokens of different types, to execute simultaneous trades in heat and electricity markets, and to process batches of energy transactions transferring multiple independent tokens between the addresses of senders and receivers.

We generated multiple scenarios with different numbers of prosumers, orders on markets, and types of transfer trades (see Table 5). Given the solution’s features of combining heat and electricity orders using multi-energy tokens and their processing in batches, the results show a significant cost reduction. In comparison with the preliminary results on the transfer of energy tokens individually with two markets and a three-energy token type, the gas cost was over three times the cost of the batch transfer.

Table 5.

Cost evaluation for different trading scenarios.

The batch transfer offers a decreased cost compared with transferring per energy token type and, at the same time, can ease the interaction with heterogeneous markets.

In our scenarios, we varied the building prosumers up to 20, with a ratio of 1:4 producers to consumers. The number of trades per producer was varied between one and five, meaning some producers traded with just one consumer, while others traded with up to five consumers. In each case, we assessed the number of transactions, the type of energy tokens traded, and the overall token transfer count. As depicted in Table 6, the increase in the number of energy tokens decreases the cost per transaction, making this approach suitable for working with higher volumes. Moreover, the number of transfer trades is significantly lower compared with the initial orders submitted by prosumers.

Table 6.

Cost variation per number of transactions.

To better understand the costs associated with each market level operation, we split it into the main components (see Table 7): minting the initial money token deposit, registering a buy or sell order, and trading (transferring the energy and money tokens). The scenario involved 20 participants in both the energy and heat markets with 12 hourly tokens per market (a total of 24 energy token types), an order quantity between 100 and 500 per energy token, and a cost per token between 10 and 15 money tokens.

Table 7.

Cost distribution per market operation.

By comparing to the results provided by [30] for batch minting and transferring for only 10 tokens, we can observe that our approach provides more cost-efficient minting and transferring in batch based on the cost per transaction, energy token types, and token quantities while maintaining a full on-chain solution.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a solution for digitizing heat and electricity flexibility using multi-energy tokens and smart contracts to enable buildings to trade them in different markets. We adapt and use ERC-1155 for the energy case, allowing the smart contracts to hold tokens of different types during market trading, such as fungible used for money-like operations and non-fungible for energy exchanges. The solution enables digitizing multi-carrier energy using the same token and a single transaction to transfer both heat and electricity and the processing of energy transactions in batches between the senders and receivers with the same blockchain address.

The evaluation results are promising, showing that our solutions are effective in digitizing the heat and electricity of buildings in various feature combinations and trading scenarios with a significant cost reduction thanks to the heterogenous orders combined with processing multi-energy tokens. The batch transfer offers a decreased cost compared with transferring per energy token type and decreases the cost per transaction, making this approach suitable for working with higher volumes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M. and T.C.; methodology, T.C.; software, O.M.; validation, T.C. and O.M.; formal analysis, O.M., I.A. and T.C.; investigation, I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M., T.C. and I.A.; writing—review and editing, I.A. and T.C.; visualization, O.M. and I.A.; funding acquisition, T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by European Commission as part of the H2020 Framework Programme, grant number 957816 (BRIGHT) and Horizon Europe Framework Programme grant number 101103998 (DEDALUS), and by the Romanian Ministry of Education and Research, CNCS/CCCDI–UEFISCDI, project grant number PN-III-P3-3.6-H2020-2020-0031 within PNIII.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IRENA. Innovation Landscape for a Renewable-Powered Future: Solutions to Integrate Variable Renewables; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Hong, T.; Piette, M.A. Energy flexibility of residential buildings: A systematic review of characterization and quantification methods and applications. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 3, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioara, T.; Anghel, I.; Salomie, I.; Antal, M.; Pop, C.; Bertoncini, M.; Arnone, D.; Po, F. Exploiting data centres energy flexibility in smart cities: Business scenarios. Inf. Sci. 2019, 476, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, L.; Di Fazio, A.R.; Russo, M.; Frattolillo, A.; Dell’isola, M. An Overview on Functional Integration of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems in Multi-Energy Buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirano, L.; Habib, E.; Parise, G.; Greco, G.; Manganelli, M.; Massarella, F.; Parise, L. Demand Side Management in Microgrids for Load Control in Nearly Zero Energy Buildings. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbungu, N.T.; Naidoo, R.M.; Bansal, R.C.; Siti, M.W.; Tungadio, D.H. An overview of renewable energy resources and grid integration for commercial building applications. J. Energy Storage 2020, 29, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, C.; Xu, Y.; Fang, J.; Pan, Y. A critical review of the performance evaluation and optimization of grid interactions between zero-energy buildings and power grids. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepisto, J.; Heine, P.; Lundell, M.; Jarventausta, P.; Repo, S. Urban Energy Transition and Heating of Apartment Buildings. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 13–15 September 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dakheel, J.; Del Pero, C.; Aste, N.; Leonforte, F. Smart buildings features and key performance indicators: A review. Sustain. Cities Soc 2020, 61, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlessi, T.; Kampelis, N.; Kolokotsa, D.; Santamouris, M.; Standardi, L.; Isidori, D.; Cristalli, C. The Concept of Smart and NZEB Buildings and the Integrated Design Approach. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 1316–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Cutsem, O.; Dac, D.H.; Boudou, P.; Kayal, M. Cooperative energy management of a community of smart-buildings: A Blockchain approach. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2019, 117, 105643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioara, T.; Antal, M.; Mihailescu, V.T.; Antal, C.D.; Anghel, I.M.; Mitrea, D. Blockchain-Based Decentralized Virtual Power Plants of Small Prosumers. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 29490–29504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ma, S.; Guo, C.; Wu, Y.; Dai, H.-N.; Wu, D. Blockchain-Based Power Energy Trading Management. ACM Trans. Internet Technol. 2021, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, Z.; Heijnen, P.; Warnier, M. A peer-to-peer market mechanism incorporating multi-energy coupling and cooperative behaviors. Appl. Energy 2022, 311, 118572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, N.; Kang, C.; Li, M.; Huo, M. From demand response to integrated demand response: Review and prospect of research and application. Prot. Control. Mod. Power Syst. 2019, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, S.; Hast, A.; Jokisalo, J.; Kosonen, R.; Syri, S.; Hirvonen, J.; Martin, K. The Impact of Optimal Demand Response Control and Thermal Energy Storage on a District Heating System. Energies 2019, 12, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Lindroos, L.; Jokisalo, J.; Kosonen, R.; Pan, Y.; Jin, H. Demand response potential of district heating in a swimming hall in Finland. Energy Build. 2021, 248, 111149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ala-Kotila, P.; Vainio, T.; Heinonen, J. Demand Response in District Heating Market—Results of the Field Tests in Student Apartment Buildings. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhonen, J.; Jokisalo, J.; Kosonen, R.; Kauppi, V.; Ju, Y.; Janßen, P. Demand Response Control of Space Heating in Three Different Building Types in Finland and Germany. Energies 2020, 13, 6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh, V.; Alimohammadisagvand, B.; Jokisalo, J.; Siren, K. A novel cost-optimizing demand response control for a heat pump heated residential building. Build. Simul. 2018, 11, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faezeh, J.; Mohammad Amin, M.; Kazem, Z.; Behnam, M.I.; Mousa, M.; Amjad, A.M. Multi-energy microgrids: An optimal despatch model for water-energy nexus. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103573. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Li, C.; Xie, K.; Hu, B.; Shao, C.; Yan, Z. Two-Stage Robust Optimization of Multi-energy System Considering Integrated Demand Response. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Power and Energy Systems (ICPES), Shanghai, China, 18–20 December 2021; pp. 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.J.; Qi, B.X.; Rong, Z.K.; Peng, K.; Zhao, Y.L.; Zhang, X.H. Multi-energy coordinated microgrid scheduling with integrated demand response for flexibility improvement. Energy 2021, 217, 119387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjorgievski, V.Z.; Markovska, N.; Abazi, A.; Duić, N. The potential of power-to-heat demand response to improve the flexibility of the energy system: An empirical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 138, 110489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, C.; Cioara, T.; Antal, M.; Anghel, I.; Salomie, I.; Bertoncini, M. Blockchain Based Decentralized Management of Demand Response Programs in Smart Energy Grids. Sensors 2018, 18, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antal, C.; Cioara, T.; Antal, M.; Mihailescu, V.; Mitrea, D.; Anghel, I.; Salomie, I.; Raveduto, G.; Bertoncini, M.; Croce, V.; et al. Blockchain based decentralized local energy flexibility market. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 5269–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karandikar, N.; Chakravorty, A.; Rong, C. Blockchain Based Transaction System with Fungible and Non-Fungible Tokens for a Community-Based Energy Infrastructure. Sensors 2021, 21, 3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosara, M.; Olivieri, L.; Spoto, F.; Tagliaferro, F. Fungible and non-fungible tokens with snapshots in Java. Clust. Comput. 2022, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toderean, L.; Antal, C.; Antal, M.; Mitrea, D.; Cioara, T.; Anghel, I.; Salomie, I. A Lockable ERC20 Token for Peer to Peer Energy Trading. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 17th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Communication and Processing (ICCP), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 28–30 October 2021; pp. 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.F.; Zhang, K.; Amara, F. ZipZap: A Blockchain Solution for Local Energy Trading. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC), Shanghai, China, 2–5 May 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilliu, F.; Vinyals, M.; Denysiuk, R.; Recupero, D.R. A novel payment scheme for trading renewable energy in smart grid. In Proceedings of the Tenth ACM International Conference on Future Energy Systems, New York, NY, USA, 25–28 June 2019; pp. 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaylov, M.; Jurado, S.; Narcis, A.; Van Moffaert, K.; Magrans, I.; Nowe, A. NRGcoin: Virtual currency for trading of renewable energy in smart grids. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on the European Energy Market (EEM14), Krakow, Poland, 28–30 May 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Petkov, I.; Mavromatidis, G.; Knoeri, C.; Allan, J.; Hoffmann, V.H. MANGOret: An optimization framework for the long-term investment planning of building multi-energy system and envelope retrofits. Appl. Energy 2022, 314, 118901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P. Survey of crosschain communications protocols. Comput. Networks 2021, 200, 108488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanak, A.; Ugur, N.; Ergun, S. A Visionary Model son Blockchain-based Accountability for Secure and Collaborative Digital Twin Environments. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), Bari, Italy, 6–9 October 2019; pp. 3512–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y. Tokenizing Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs)—A Blockchain Approach for REC Issuance and Trading. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 134477–134490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingärtner, T. Tokenization of Physical Assets and the Impact of IoT and AI. In Proceedings of the European Union Blockchain Observatory and Forum, Maraka, Spain, 11–13 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bekrar, A.; El Cadi, A.A.; Todosijevic, R.; Sarkis, J. Digitalizing the Closing-of-the-Loop for Supply Chains: A Transportation and Blockchain Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydov, V.; Gazaryan, A.; Madhwal, Y.; Yanovich, Y. Token Standard for Heterogeneous Assets Digitization into Commodity. In Proceedings of the ICBTA 2019: 2019 2nd International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Applications, New York, NY, USA, 9–11 December 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, E.; Veretennikova, A.; Fedoreev, S. The Model of OTC Securities Market Transformation in the Context of Asset Tokenization. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idelberger, F.; Mezei, P. Non-fungible tokens. Internet Policy Rev. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.B.; Torrisi, N.M.; Pantoni, R.P. Third Party Certification of Agri-Food Supply Chain Using Smart Contracts and Blockchain Tokens. Sensors 2021, 21, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madhwal, Y. Implementation of Tokenised Supply Chain Using Blockchain Technology. In Proceedings of the 2020 21st IEEE International Symposium on a World of Wireless, Mobile and Multimedia Networks (IEEE WoWMoM 2020), Cork, Ireland, 31 August–3 September 2020; pp. 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrons, R.K.; Cosby, T. Applying blockchain in the geoenergy domain: The road to interoperability and standards. Appl. Energy 2020, 262, 114545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, M.F.; Zhang, K.; Shahzad, A.; Ouhimmou, M. LogLog: A Blockchain Solution for Tracking and Certifying Wood Volumes. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain and Cryptocurrency (ICBC), New York, NY, USA, 30 January–1 February 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhwal, Y.; Chistiakov, I.; Yanovich, Y. Logging Multi-Component Supply Chain Production in Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2021 4th International Conference on Computers in Management and Business, New York, NY, USA, 30 January–1 February 2021; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masking and the C/C++ Bitwise Operators. 2023. Available online: https://www.clivemaxfield.com/coolbeans/masking-and-the-c-c-bitwise-operators/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).