1. Introduction

Chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) is used therapeutically in the treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX), a rare genetic inborn error of bile acid synthesis. CDCA is one of the primary endogenous bile acids and is synthesized in the liver from cholesterol via two major bile acid synthesis pathways. The classic or neutral pathway that accounts for approximately 90% of bile acid synthesis starts with hydroxylation of cholesterol by CYP7A1 to form 7α-hydroxycholesterol, followed by formation of CDCA via sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1) [

1,

2]. The alternative pathway that accounts for approximately 10% of bile acid synthesis starts with hydroxylation of cholesterol by CYP27A1 to 27-hydroxycholesterol followed by conversion to CDCA via CYP7B1 [

1,

2]. CDCA inhibits CYP7A1, establishing a negative feedback loop that inhibits bile acid synthesis when there are sufficient bile acids [

1]. CTX is characterized by CYP27A1 deficiency, and as CYP27A1 is essential in CDCA synthesis, CTX patients have severely decreased levels of endogenous CDCA, stimulating increased production of bile acids and the generation and accumulation of atypical sterol molecules including bile alcohols (and their corresponding glucoronides) and cholestanol [

3]. This leads to various severe disease symptoms such as infantile-onset diarrhea, juvenile cataract and tendon xanthomas, as well as adult onset of neurologic dysfunction [

3]. Treatment with CDCA is used as replacement for endogenous CDCA that silences the bile acid synthetic pathway via downregulation of CYP7A1, which in turn can prevent the onset of neurological complications in CTX patients when initiated before neurological symptoms are present [

4].

Limited information is available on the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic CDCA. Orally administered CDCA is absorbed in the small intestine, binds to plasma proteins, and is cleared by the liver [

5,

6]. In the liver, CDCA is almost completely conjugated with glycine or taurine before being excreted into bile and transported to the intestine and into the enterohepatic circulation along with endogenous bile acids [

2,

5,

6]. Conjugated CDCA is reabsorbed in the jejunum and the terminal ileum [

7]. However, reabsorption is not complete and is variable (29- 84%) [

6]. Unabsorbed CDCA is metabolized by gut bacteria into ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA) [

1,

2]. These secondary bile acids are then mostly reabsorbed in the distal ileum, secreted into the portal circulation and transported back to the liver. This efficient enterohepatic circulation ensures that 95% of bile acids are returned to the liver and that only 5% of total bile acids, and also therapeutic bile acids, are excreted in the feces [

1,

2,

5]. Because of the enterohepatic circulation, serum bile acid concentrations are low and the volume of distribution is high [

5]. Upon supplementation of CDCA, peak serum concentrations are expected after 50–120 min. CDCA has a biological half-life of approximately 45 h to 4 days in the enterohepatic circulation [

5,

6,

7].

CDCA has been used off-label for treatment of CTX for many years. In 2017, Leadiant CDCA capsules received a marketing authorization in the EU as an orphan drug for the treatment of CTX (EU/1/16/1110) [

6]. The price increase that followed and subsequent non-reimbursement under the Dutch healthcare insurance meant that Leadiant CDCA was no longer available for Dutch CTX patients. In order to continue patient care, the Amsterdam UMC hospital pharmacy has been compounding CDCA capsules as a magistral formula preparation for its own patients since 2018, which means that approximately 60 Dutch patients now receive these pharmacy-compounded CDCA capsules [

8]. The pharmacy-compounded capsules are prepared manually using a dry powder blend of CDCA active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and the single excipient silica (colloidal anhydrous). In comparison, the authorized product is produced automatically from granulated powder and contains the excipients maize starch, magnesium stearate, silica (colloidal anhydrous), and water [

6].

As described, little to no clinical data can be found on the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic CDCA. To be able to receive a marketing authorization, pharmacokinetic studies are mandatory, but for pharmacy preparations, this is not the case. To obtain a clear picture of the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic CDCA, we performed this randomized cross-over clinical trial in which the pharmacokinetic characteristics of the pharmacy-compounded CDCA capsules were investigated and compared with that of authorized CDCA capsules. Additionally, a bioequivalence analysis was performed. Lastly, the impact of single-dose CDCA administration on the bile acid profile in serums and on safety parameters was evaluated.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

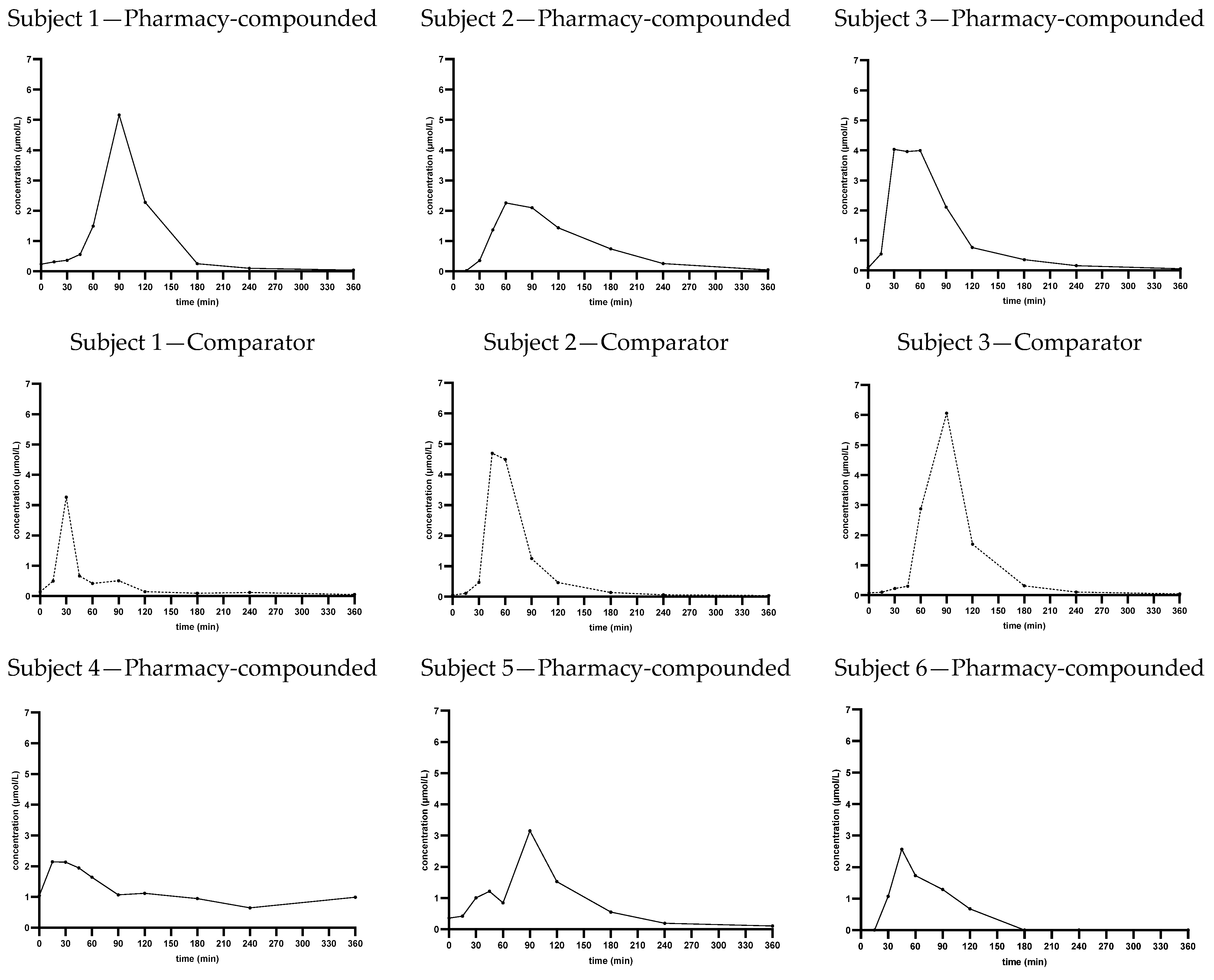

With this study we provide the pharmacokinetic data of pharmacy-compounded CDCA capsules. As described in the introduction, limited research has been performed on the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic CDCA, and in the form of pharmacy-compounded capsules even less. Therefore, the results of this study provide a valuable insight into the pharmacokinetic profile of CDCA capsules. The pharmacokinetic parameters and the concentration–time curve of the capsules show that orally administered CDCA is well absorbed and further distributed and metabolized within 6 h. Comparing the pharmacy-compounded CDCA capsules to the authorized CDCA capsules, the average concentration–time curves for the two products appear similar and the average AUC(0–6h) and tmax are not significantly different, indicating that the two products show the same exposure rate and have a similar total absorption and bioavailability. The average tmax is similar and around 1 h after administration.

The average C

max, however, shows a high variability and is significantly higher in the comparator product than in the pharmacy-compounded capsules, suggesting a lower absorption rate of the compounded capsules. This difference in C

max is not observed looking at the average concentration–time curves in

Figure 1, indicating also a high variation in t

max between individuals. This can be confirmed from the individual concentration–time curves in

Appendix A Figure A1 and the plots in

Figure 2. An explanation for the lower average C

max would require additional investigation. It could be related to the formulation of the capsules, as the dry powder mixture with limited excipients from the pharmacy-compounded capsules can affect absorption differently than the wet granulation production method of the comparator product, leading to a lower absorption rate. However, this is only speculative. It is also possible that with more sampling time points around t

max, the C

max can be determined more accurately and less or no significant difference might be observed.

Both the concentration–time curves and the pharmacokinetic parameters of the two products show a high standard deviation and a broad range, indicating that there is a high inter-subject variability for therapeutic CDCA. Considerable inter- and intra-subject variability in peak serum concentrations makes bioavailability comparison difficult. A cross-over study design was chosen to eliminate the interindividual variability factor; however, a large standard deviation was still observed. This might be explained by the fact that CDCA is an endogenous bile acid with a complex metabolism that is mainly confined in the enterohepatic circulation, making plasma levels less clinically relevant. CTX patients have reduced CDCA levels, and therefore the therapeutic effectiveness of CDCA can better be related to the concentration in bile than to plasma concentrations [

5,

7]. Therefore, the lower average C

max of the compounded CDCA capsules is expected to have little clinical consequences. Most patients with CTX receive a chronic dose of 250 mg three times a day, making total exposure in the enterohepatic circulation more relevant than peak plasma concentrations. Also, as CDCA is an endogenous bile acid and individual C

max plasma values already vary widely between individuals, the therapeutic window is likely not that narrow. These factors mean that this study is not directly applicable to patients with CTX undergoing chronic treatment. This study focuses on the investigation and comparison of the pharmacokinetics after a single dose. Under controlled conditions such as this clinical study, the AUC

(0–6h) can be used for bioavailability comparison [

7]. As the average AUC

(0–6h) is not significantly different between the treatments, we can conclude that the bioavailability of the two products is similar.

Additionally, bioequivalence analysis was performed to investigate if bioequivalence can be demonstrated based on the data from this study. Results show that the 90% confidence intervals of the ratio of the AUC

(0–6h) and the C

max of the pharmacy-compounded capsules and the comparator product are not within the acceptance criterium of 80.00–125.00% [

9]. Even for AUC

(0–6h), which has a similar mean which is not significantly different, the confidence interval is too wide. This is probably due to the high variability as discussed earlier. A larger sample size would normally narrow the confidence interval if the AUCs

(0–6h) are indeed similar. Bioequivalence analysis did demonstrate a significant effect of the treatment on C

max and confirmed that the compounded capsules have a lower C

max. A different study set-up would be required to properly investigate bioequivalence. However, that was not the goal of this study and the pharmacy-compounded capsules were not developed to be bioequivalent to the authorized product, but to provide our CTX patients with a qualitative CDCA treatment.

Lastly, the effect of a one-time oral dose of 250 mg CDCA on other bile acids and on side effects was investigated. Little changes are observed in other bile acids, which is also not to be expected after a single dose. One adverse event occurred during the study, but was evaluated as unrelated to the treatment.

To make this study feasible for a hospital pharmacy, various choices were made in the study set-up. Firstly, the study was performed with the minimum required number of healthy volunteers according to the EMA guideline for bioequivalence. However, in hindsight, since we found a high variability, a larger sample size would be desirable to narrow confidence intervals and thereby strengthen conclusions. Since little information was available on the pharmacokinetics of therapeutic CDCA, our results might be helpful in sample size calculations for future studies.

Also, no baseline correction was performed for endogenous plasma CDCA levels. Extremely low baseline levels in plasma were expected as CDCA is mostly confined in the enterohepatic circulation. If substantial increases over baseline endogenous levels are seen, baseline correction may not be needed. On average we found CDCA plasma levels at t = 0 of 4.6% of the average Cmax. Although the found endogenous levels are indeed low, performing a baseline correction might have strengthened our conclusions.

Furthermore, we chose to perform this study groups that were standardized as much as possible (fasted healthy male volunteers in a cross-over setting) to be able to compare the two treatments as well as possible in a small group. This resulted in exclusion of female participants, which is a limitation as sex-related pharmacokinetic differences were not investigated. For future studies, it would be interesting to also include females for potential sex impact, and to include subjects in fasted versus non-fasted state to investigate the effects of food. Lastly, to be able to translate results to clinical practice, it would be useful to perform a pharmacokinetic study in CTX patients.

In conclusion, the pharmacokinetic profile of the pharmacy-compounded CDCA capsules shows that the product is well absorbed and that there is high variability in absorption rate and Cmax between individuals. The average AUC(0–6h) is not significantly different between the compounded capsules compared to the registered product, indicating a similar extent of absorption.