Abstract

Highly active antiretroviral therapy has led to a significant increase in the life expectancy of people living with HIV. The trade-off is that HIV-infected patients often suffer from comorbidities that require additional treatment, increasing the risk of Drug-Drug Interactions (DDIs), the clinical relevance of which has often not been determined during registration trials of the drugs involved. Therefore, it is important to identify potential clinically relevant DDIs in order to establish the most appropriate therapeutic approaches. This review aims to summarize and analyze data from studies published over the last two decades on DDI-related adverse clinical outcomes involving anti-HIV drugs and those used to treat comorbidities. Several studies have examined the pharmacokinetics and tolerability of different drug combinations. Protease inhibitors, followed by nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and integrase inhibitors have been recognized as the main players in DDIs with antivirals used to control co-infection, such as Hepatitis C virus, or with drugs commonly used to treat HIV comorbidities, such as lipid-lowering agents, proton pump inhibitors and anticancer drugs. However, the studies do not seem to be consistent with regard to sample size and follow-up, the drugs involved, or the results obtained. It should be noted that most of the available studies were conducted in healthy volunteers without being replicated in patients. This hampered the assessment of the clinical burden of DDIs and, consequently, the optimal pharmacological management of people living with HIV.

1. Introduction

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) for the treatment of patients with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) has transformed this infection from a fatal to a manageable chronic condition [1].

In fact, the number of deaths from Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS), which develops in inadequately treated HIV+ patients, is decreasing worldwide and the life expectancy of People Living With HIV (PLWH) treated with HAART increases from 10 to 25 years when compared with patients who do not receive this therapy [1,2].

HAART is based on the combination of different antiretroviral agents, divided into six main classes: Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs), Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs), Protease inhibitors (PIs), Integrase Inhibitors (INIs), Fusion inhibitors (FIs), Chemokine Receptor Antagonists (CCR5 Antagonists) [3]. These drugs act at different stages of the viral life cycle and have different molecular targets. NRTIs/NNRTIs, PIs, and INIs inhibit, respectively, proteins p66/p51, p11, and p32 encoded by the pol gene; FIs act by binding glycoprotein 120 and 41 encoded by the env gene; CCR5 Antagonist acts by binding the human trans-membrane receptor of chemokine CCR5, preventing the virus from attaching to CD4+ T lymphocytes.

HAART reduces viremia and increases the number of CD4+ T lymphocytes, thereby restoring the patient’s immune activity [3,4]. In HIV+ patients, assessment of viral load and CD4+ T lymphocyte count is performed periodically to monitor the efficacy and tolerability of treatment [5,6]. HIV+ patients may develop comorbidities [7], resulting in the need for polypharmacotherapy, which in turn exposes them to an increased risk of adverse drug events (ADEs), including those related to drug-drug interactions (DDIs).

The term ‘DDI’ refers to the phenomenon whereby the pharmacodynamic (PD) or pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles of a drug are altered by the concomitant administration of other pharmacologically active agents, potentially causing ADEs. For instance, the concomitant use of multiple drugs may cause toxic synergism or induce or inhibit transporters such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) or phase I (e.g., cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoforms) or phase II (e.g., uridine 5′-diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1, UGT1A1) metabolic enzymes.

In particular, the use of PK boosters, such as ritonavir (RTV) and cobicistat, which act as inhibitors of various cytochrome (CYP) P450 enzyme isoforms, may influence the CYP450-dependent metabolism of co-administered drugs, thereby increasing their plasma exposure [8,9,10]. One of the most important goals achieved with the introduction of HAART is the treatment of PLWH with concomitant infections such as malaria, tuberculosis, and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV). Coinfections can affect the therapeutic outcomes of patients per se, and drugs used to treat co-infected patients can interact with anti-HIV agents. This adds to the inevitable occurrence of HIV mutations associated with drug resistance and further complicates the long-term management of patients [11,12]. DDI-related ADEs can decrease adherence and persistence to therapy, accelerating the onset of drug resistance and leading to the need for additional drug therapies. In clinical practice, this leads to an increase in specialist visits and hospitalizations, with a negative economic impact [13,14].

When polypharmacotherapy is administered chronically in all medical areas, special attention should be paid to treatment monitoring, establishing a link between all clinicians involved in patient care, including general practioners [15,16]. However, data on the mechanisms and real impact in clinical practice associated with the concomitant use of multiple drugs are scarce and often inconclusive.

This review aims to summarize and analyze data from studies, published between 2000 and 2024, on DDIs and DDI-related ADEs involving drugs belonging to HAART and those for the treatment of comorbidities, with a focus on drugs used in patients with HIV and coinfections.

2. Studies Investigating DDIs Between HAART and Co-Administered Drugs in Healthy Subjects

Seventy-six studies, enrolling a total of 2044 healthy subjects, were analyzed (Table 1). Among them, 57 were Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs) [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73], 5 were crossover Clinical Trials (CTs) [74,75,76,77,78], 9 were referred to as PK studies [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87], and 5 were DDIs studies [88,89,90,91,92]. Regardless of the study design, the main aim was to evaluate whether DDIs lead to changes in PK and, consequently, in the drug safety and efficacy profile.

Table 1.

Main characteristics and results of the studies, published over the last two decades, that have investigated DDIs between HAART and co-administered drugs in healthy subjects. The drugs were orally administered in all studies with the exception of Walimbwa et al. [68] in which AS/AQ were injected.

The drugs involved were antivirals belonging to the HAART regimen, such as PIs, INIs, and NNRTIs and drugs used to treat comorbidities and coinfections such as Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) and HCV, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB). In addition, several studies report data on contraceptives, the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) omeprazole (OME), and antiacids, antidepressants, antiepileptics, statins, and supplements/food.

Among the INIs, that represent one of the first-line treatments for HIV infection [93], several studies have investigated possible changes in the PK of raltegravir (RAL) [18,20,21,28,29,45,66,67,69,74,86] or dolutegravir (DTG) [50,51,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,68,80,88] when these drugs were co-administered with other antivirals, antibiotics, contraceptives, anti-tuberculosis, anti-malarian, statins, and herb supplements. With regard to RAL, the studies overall did not find changes in the PK of the drug such as to require a change in dosing or other clinical interventions, nor DDIs potentially associated with adverse outcomes.

Only Iwamoto et al., who studied the possible interference between oral omeprazole (OME) 20 mg daily and a single oral dose RAL 400 mg in 28 healthy subjects, reported that this DDI caused an increase in the gastric pH and solubility of RAL resulting in a 3–4-fold increase in the Area Under Curve (AUC) and maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) of the antiviral and a consequent increase in its bioavailability [29].

Additional evidence is available on the possible involvement of DTG in clinically significant DDIs due to changes in PK parameters of DTG or co-administered drugs.

Brooks et al. highlighted possible ADEs mediated by cytokine release following the co-administration of this oral INI 50 mg daily with the oral isoniazid/rifapentine (INH/RPT) 900/900 mg daily regimen used as a treatment option in HIV+ patients with latent TB. The study was stopped because, after the third dose of INH-RPT, a severe flu-like syndrome associated with elevated aminotransferase levels occurred in 2 of the 4 enrolled subjects. In these subjects, the AUC of DTG was reduced by 46%, while that of INH increased by 67–92%. Despite the interruption of the study, this result appears very interesting because both increased aminotransferase and flu-like syndrome are ADEs recognised to be associated with the INH/RPT regimen [88].

Song et al. conducted several studies to assess changes in the activity profile of DTG or drugs/supplements co-administered with it [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64]. As DTG is primarily metabolized by uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) and CYP3A4 [94], co-administration with potent inducers of these enzymes, such as carbamazepine (CBZ), can easily lead to changes in the PK profile of DTG. In fact, a statistically significant decrease in AUClast, Cmax, and Cτ of DTG was found to be 49, 33, and 73%, respectively. The authors suggested taking oral DTG 50 mg twice daily instead of once daily, similar to what is recommended when this antiviral is administered with other potent UGT1A1/CYP3A inducers such as tipranavir/ritonavir (TPV/r), efavirenz (EFV) and rifampicin [95,96].

Furthermore, it was shown that the AUCinf, Cmax and C24 of oral DTG 50 mg, were reduced by 39, 37 and 39%, respectively, when co-administered with fasting oral calcium carbonate 1200 mg and by 54, 57, and 56%, respectively, under similar conditions, when co-administered with oral iron fumarate 324 mg. For this reason, it is advisable to distance the intake of DTG two hours before or six hours after taking calcium and iron supplements [56].

The same authors evaluated whether food could alter the PK of DTG. Indeed, although without clinical consequences, the AUCinf increased by up to 66% when oral DTG was taken with high-fat foods [59]. Notably, accumulating evidence concerns the potential effect of DTG on the PK of metformin (MET). In particular, DTG, being a known inhibitor of organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) [97], may increase the plasma concentration of drugs eliminated via OCT2, such as MET.

Song et al. showed that the AUClast and Cmax of MET increased by 79% and 66%, respectively, when this antidiabetic was administered with oral DTG 50 mg once daily and by 145% and 111%, respectively, with DTG 50 mg twice daily. For these reasons, when co-administering DTG, the dose of oral MET 500 mg twice daily should be monitored based on tight glycaemic control [63]. Ford et al. studied the influence of oral rifampin (RIF) 600 mg daily, an antibiotic commonly used to treat TB, on the PK of oral cabotegravir (CAB) 30 mg. RIF is an inducer of the CYP450 isoforms and UGT1A1, thus it is able to influence the metabolism of CAB. Therefore, co-administration of RIF/CAB is not recommended due to the possible significant decrease in plasma exposure to this antiretroviral agent [75]. It is noteworthy potential effects deriving from DDIs involving PIs in polypharmacy.

Fang et al. and Zhu et al. [24,73] evaluated the influence of the co-administration of OME with nelfinavir (NFV) and atazanavir/ritonavir (ATV/r), respectively.

The first study, although the precise mechanism has not yet been fully elucidated, showed that oral OME 40 mg daily is able to significantly reduce the AUClast, Cmax, and minimum plasma concentration (Cmin) of oral NFV 1250 mg twice daily (by 36, 37 and 39%, respectively) and even more so the PK parameters of the active NFV metabolite, M8 (by 92, 89 and 75%, respectively). For this reason, co-administration of these two drugs is not recommended, as it could lead to loss of viremic control [24].

The second study suggested that oral OME 20 mg had a less pronounced effect on the PK profile of oral ATV than the 40 mg dosage. Indeed, it is widely reported that co-administration of ATV/r 400/100 mg with OME 40 mg is strongly discouraged, because it results in a decrease in ATV bioavailability of up to 75% [98]. Specifically, co-administration of OME 20 mg with ATV/r 300/100 mg reduced the AUC and Cmin of ATV by 42% and 46%, respectively, while the Cmin of ATV was reduced by about 30% using ATV/r 400/100 mg. This highlights the importance of choosing the most appropriate dosage of ATV/r to anticipate the effects of this DDI.

Garraffo et al. [76] investigated the alterations potentially associated to TPV/r use in the PK profile of tadalafil (TAD), a phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) inhibitor widely used in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in HIV+ patients. TAD is metabolised mainly by the CYP3A4 isoform [99], on which TPV acts as an enzyme inducer and RTV as an inhibitor. Due to the conflicting actions expressed by these antiretrovirals, it was necessary to evaluate the effects on various PK parameters of TAD [76]. The authors showed that administration of a single oral dose of TAD 10 mg with the first dose of oral TPV/r 500/200 mg twice daily led to an increase in the AUCinf of TAD by 133%. This is presumably due to the increased in RTV exposure during the first few days of treatment with TPV/r, when the RTV-dependent inhibitory effect on CYP3A4 is likely to occur, and then disappear once TPV/r has reached a steady-state. For these reasons, when it is necessary to take TAD during the first few days of treatment with TPV/r, it is advisable to reduce the dose of TPV/r by 50% until steady-state is reached [76].

The effect of enzyme induction by lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) was also analysed in the study by Hogeland et al. in relation to its potential ability to induce CYP2B6 and UGT1A1.

In particular, the concomitant use of oral LPV/r 400/100 mg twice daily with oral bupropion (BUP) 100 mg daily, an antidepressant used in the treatment of major depression, obesity, asthenia, and smoking cessation, resulted in a significant decrease in Cmax by 57% and AUCinf by 57%, requiring an increase in BUP dosage by up to 100% [82].

The same effects were studied by Jacobs et al. with regard to CYP1A2 as well as UGT isoforms, with the use of oral fosamprenavir (FPV), pro-drug of amprenavir (APV), in combination with oral RTV 700/100 mg twice daily. Co-administration of these antivirals with oral olanzapine (OLZ) 15 mg an atypical antipsychotic, reduced plasma half-life (t1/2) of OLZ by an average of 32%. Increasing the dose of OLZ from 10 mg to 15 mg (50%) the AUC returned to the bioequivalence range [30]. The same antiviral combination was co-administered with posaconazole (POS), an antimycotic, in the study by Brüggemann et al.

The authors suggest that the use of FPV alone with the antimycotic agent resulted in a marked decrease of AUC and Cmax of APV, compared to the use of oral FPV boosted with RTV (2.9- and 1.6-fold lower) 700/100 mg twice daily, and therefore unboosted FPV 700 mg twice daily should not be used in combination with oral POS 400 mg once or twice daily [22].

Fichtenbaum et al. [25] investigated potential DDIs between PIs and statins 40 mg. The study population was subdivided into 4 arms; arms 1, 2, and 3 received oral pravastatin (PRAV), simvastatin, and atorvastatin (ATO), respectively, with oral RTV 400 mg + saquinavir (SQV) 400 mg twice daily, while arm 4 received oral pravastatin 40 mg with oral NFV 1250 mg twice daily. Because of RTV-dependent inhibition on CYP3A4, statins that are mainly metabolized by this enzyme (e.g., simvastatin and lovastatin) should be not co-administered with RTV-based HAART, while treatment with ATO should be initiated at doses of 10 mg daily. In contrast, PRAV/NFV did not affect NFV/M8 concentration [25].

In addition, Yu et al. found that exposure to oral pitavastatin (PTV) 4 mg daily decreased by 26% for the concomitant use of oral darunavir (DRV) co-formulated with RTV (DRV/r) 400/100 mg daily, which can alter the activity of transporters involved in PTV uptake and efflux [87].

3. Studies Investigating DDIs Between HAART and Co-Administered Drugs in HIV+ Patients

Table 2 shows the main characteristics and results of 14 studies involving HAART and co-administered drugs in HIV+ patients. With regard to the study design, 4 of them are RCTs [69,100,101,102], 6 are referred to as PK studies [103,104,105,106,107,108], 1 is an observational study [109], 1 is referred to as pharmacogenetic (Pgx) study [110] and 2 as DDIs studies [111,112]. These investigations, which altogether enrolled 703 subjects, had in common the main objective of identifying potential DDIs involving one or more drugs used in the HAART regimen that may cause ADEs or changes in the PK profiles of antivirals and co-administered drugs [69,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110]. In particular, 6 out of 14 [69,100,101,102,107,109] concerned potential DDIs between different drugs belonging to HAART, while 8 out of 14 explored DDIs between drugs contained in HAART and others belonging to different therapeutic classes. Of the latter, 5 studies [103,104,105,108,110] concerned the use of contraceptives, 1 concern the anticancer drug sunitinib [106], 1 the direct oral anticoagulant dabigatran [111], and 1 the statins fluvastatin (FLUV) and PRAV [112].

Table 2.

Main characteristics and results of the studies, published between 2000 and 2024, investigating DDIs between HAART and co-administered drugs in HIV+ patients. The drugs were orally administered in all studies with the exception of Vogler et al. [104] in which NGMN and EE were used as a transdermal patch, Luque et al. [106] in which DMPA was intramuscularly administered, Ruxrungtham et al. [108] in which ENF was used by subcutaneous injection. Vieira et al. [109] and Neary et al. [111] used ENG and ETON as a subcutaneous contraceptive implant.

PIs and NNRTIs have often been studied for their potential involvement in DDIs with other drugs used to treat comorbidities commonly present in PLWH, or prophylactic agents. With regard to PIs, the interaction between LPV/r and contraceptives is well-known. In fact, the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs) of LPV and RTV recommend the use of additional contraceptive methods during therapy with these antivirals due to the risk of reducing the contraceptive effect.

Luque et al. [105] investigated the clinical outcomes potentially associated with the co-administration of oral LPV/r 400/100 mg and intramuscular (IM) depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) 150 mg in HIV+ women. The authors found a significant increase in DMPA exposure in patients co-administered with LPV/r. First, PK parameters, such as AUC and Cmax of LPV and RTV were measured when co-administered separately with DMPA. In this case, no significant impact was found. Next, when LPV and RTV were coformulated as LPV/r, the authors found a 46% increase in the AUC and a 66% increase in Cmax of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), the active metabolite of DMPA. These effects were probably due to the inhibitory action of LPV/r on CYP3A4, which is involved in DMPA metabolism, resulting in the risk of menstrual irregularities and abnormal vaginal bleeding [105].

Vogler et al. [103] reported a significant reduction (45%) in plasma levels of transdermal ethylestradiol (EE) 33.9 μg/24 h and an increase (83%) in norelgestromine (NGMN) 203 μg/24 h in patients treated with the oral lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r) regimen 400/100 mg twice daily. The authors suggested that increased plasma levels of NGMN could increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). The hypothesised mechanism is the potential action of LPV and RTV as CYP450 enzyme inhibitors [103].

Another DDI involving PIs and contraceptives is described by DuBois et al. [104]. This study showed that exposure to contraceptives containing oral norethindrone (NETA) 0.35 mg daily, may increase when oral ATV is co-administered with RTV 300/100 mg. In fact, the authors found 50% increase in the AUC and a 67% increase in the Cmax of NETA. Moreover, oral clearance (Cl/F) and volume of distribution (Vd) decreased, suggesting that interaction with RTV increases the bioavailability of NETA, without affecting its half-life in plasma.

Another DDI related to PIs concerns sunitinib. This is reported in the SmPC of RTV, which warns that concomitant use of RTV may increase serum concentrations of sunitinib due to RTV-dependent CYP3A4 inhibition. Rudek et al. [106] investigated ADEs that could result from such DDIs in HIV+ patients with solid or hematological malignancies. In particular, it was found that patients treated with oral sunitinib 50 mg daily in the absence of RTV showed toxicity (grade 3 neutropenia and grade 1/2 diarrhea, mucositis, and fatigue) comparable to that of patients receiving sunitinib 37.5 mg daily concomitantly with oral RTV 25 mg daily. Based on these results, the authors suggested reducing the sunitinib dosage to 37.5 mg in patients receiving RTV [106].

With regard to the NNRTI class, both EFV, and nevirapine (NVP) were examined in combination with contraceptives. These interactions may influence plasma levels of contraceptives, impairing their efficacy and increasing the risk of ADEs related to both the HAART and the contraceptives themselves.

The study conducted by Vieira et al. [108] also evaluated the DDIs between EFV and ENG. The oral EFV-based HAART regimen, containing 600 mg of the NNRTI, reduced the bioavailability of subdermal implant ENG 68 mg, by decreasing its AUC, Cmax and Cmin by 63.4, 53.7 and 70%, respectively. This is because EFV acts as an inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme. Cases of unwanted pregnancies have been reported in women using ENG while taking an EFV-based HAART, emphasizing the need for caution when co-administering these two drugs [108].

A study by Neary et al. [110] explored potential DDIs between oral EFV 600 mg daily or oral NVP 200 mg twice daily and the subcutaneous implant etonogestrel (ETON) 68 mg. The results indicated that genetic factors, particularly specific polymorphisms in the CYP2B6 gene, may significantly influence plasma levels of ETON. In particular, the CYP2B6 516 G>T genetic variant was identified as a factor capable of influencing EFV concentration, leading to increased plasma exposure. Since EFV is an inducer of CYP3A4, which is responsible for ETON metabolism, a reduction in contraceptive levels may occur following the co-administration of the two drugs. In this study, a 33% reduction in the AUC of ENG was observed in participants homozygous for the T allele compared to those homozygous for the G allele of the CYP2B6 gene (516 G>T). Similarly, the AUC of levonorgestrel (LNG) was 64% lower in subjects with homozygous TT allele than in those homozygous GG for the same polymorphism. Furthermore, among participants homozygous CC and heterozygous CT for the CYP2B6 polymorphism (983 T>C), there was a 20% decrease in the AUC of ETON, while for LNG there was a 23% decrease in this same group. This evidence suggests a greater decrease in PK exposure to ETON in the presence of CYP2B6 genetic variants, which correlate with reduced metabolism of EFV. This effect could be explained by high concentrations of EFV inducing increased activity and expression of CYP3A4, an enzyme known to facilitate ETON elimination. These DDIs could significantly decrease the efficacy of hormonal contraceptive implants in HIV+ women, thus limiting their use [110].

Several studies have analyzed DDIs between drugs belonging to the HAART regimen. For instance, the research by Fletcher et al. [100] showed that the combination of the oral PI SQV administered 800 mg three times daily, with the oral NNRTI delavirdine (DLV) 600 mg twice daily, and the oral NRTI adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) 120 mg once daily, resulted in a reduction of plasma SQV concentrations by approximately 50% compared to subjects treated with DLV alone. This result indicates a significant interaction between SQV and DLV. Furthermore, the reduction in SQV concentrations occurred exclusively in the groups receiving the combination of DLV and ADV, whereas similar effects were not observed with other PIs, such as oral RTV 400 mg daily, and oral NFV 750 mg three times daily. No synergistic or additive effects were found between LDV and ADV, despite their different mechanisms of action, with disappointing virological results. These ADRs could be attributable to CYP450-mediated mechanisms of metabolism and the activity of transporter proteins such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp) [100].

The study conducted by Sekar et al. [102] found that the addition of oral DRV/r 300/100 mg (oral solution, treatment A) or 400/100 mg (tablets, treatment B2), to a therapeutic regimen including oral NVP 200 mg, resulted in an increase in plasma levels of NVP, as RTV inhibits the enzyme CYP3A4, responsible for its metabolism, as measured through blood samples and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). TDM, by recording plasma levels at predetermined intervals, allowed Cmin, Cmax, and AUC to be calculated. However, this increase did not appear clinically significant, and overall, the combination of DRV/r and NVP was generally well tolerated by HIV+ patients, although the study evaluated lower doses than typically recommended, no dose adjustment of NVP is expected even at higher doses [102].

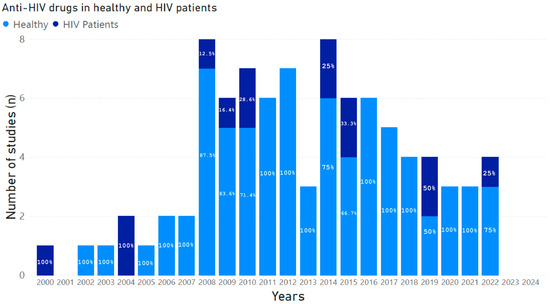

Figure 1 shows the number of studies published during the period 2000–2024, conducted in healthy volunteers and HIV+ patients that investigated potential DDI-related adverse outcomes involving drugs belonging to HAART and drugs co-administered for the treatment of comorbidities.

Figure 1.

Number of studies published between 2000 and 2024, conducted in healthy volunteers and HIV+ patients that investigated potential DDI-related adverse outcomes involving drugs belonging to HAART and drugs co-administered for the treatment of comorbidities. The percentages of studies, calculated from the total number of studies published year by year, are marked within each histogram.

4. Studies Investigating DDIs Between HAART and Co-Administered Drugs in HIV Patients with Coinfection

PLWH are at increased risk of coinfection. Table 3 shows the main characteristics and results of studies that have enrolled HIV+ patients with TB, malaria, or HBV.

Table 3.

Main characteristics and results of the studies, published between 2000 and 2024, that have investigated DDIs between HAART and co-administered drugs used for the treatment of co-infections (tuberculosis, malaria, HBV) in HIV mono-infected or co-infected patients. All drugs reported in these studies were orally administered.

Studies reporting data on HIV/HCV coinfection, which are more numerous and mainly involve direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), are described in the next paragraph.

Nineteen studies, involving a total of 2712 patients, among them, 7 were RCTs [113,114,115,116,117,118,119], 8 were referred to as PK studies [120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127], 2 to as DDIs studies [128,129], 1 was a prospective cohort study [130] and 1 was retrospective cohort study [131]. This studies analyzed potential DDIs [127,128] or DDI-related adverse outcomes [118,119,120,129]. Fourteen studies [113,114,115,116,117,119,121,122,123,126,127,128,130,131] have focused on TB, 4 [118,120,124,125] on malaria, and only 1 study on HBV [129].

A common objective of these studies was to investigate potential DDIs between drugs used in PLWH with coinfection. Among the 14 studies in HIV/TB patients, 4 focused on the co-administration of the anti-TB RIF and the anti-HIV EFV demonstrating the efficacy and good tolerability of this drug combination. Lopez-Cortes et al. [115] have observed that it is necessary to increase the oral dose of EFV from 600 mg to 800 mg daily when combined with RIF 120 mg daily because this anti-TB is a strong inducer of the CYP3A4 enzyme. Scarsi et al. [119] have analysed PK of EFV 600 mg daily and RIF 10 mg/kg daily when they are combined with oral LNG 1.5 mg or 3 mg daily, a drug used for long-term contraception. This study showed that both EFV and RIF accelerate LNG metabolism through induction of the CYP3A4 isoform, leading to a reduction in half-life and a decrease in overall LNG exposure. However, this effect did not affect contraceptive efficacy of LNG [119].

Moreover, RIF is known to induce the CYP2B6-mediated EFV 8-hydroxylation pathway, potentially causing an increase in the metabolism of drugs metabolized by this enzymatic isoform, such as EFV [132]. Actually, Ren et al. [123] demonstrated a clear trend towards a reduction in oral EFV 50 mg half-life in children when RIF 10 mg/kg daily was administered together with EFV without changing the Cmin of EFV. This effect on EFV half-life was not evidenced in HIV/TB co-infected even when doubling the dose of RIF [123].

Therefore EFV/RIF co-administration was considered safe both in children and adults HIV/TB co-infected patients [113,123]. Two studies have provided details on safety profile of RIF co-administered with LPV/r, showing that CYP3A4-inducing effect of RIF is reverted by the CYP3A4-inhibiting effect of RTV in the LPV/r formulation [116,122].

Two studies have provided details on the safety profile of RIF co-administered with LPV/r, showing that the CYP3A4-inducing effect of RIF is negated by the CYP3A4-inhibiting effect of RTV in the LPV/r formulation [116,122]. In the study conducted by Zhang et al. [116] the AUC of oral LPV/r (as oral solution) 230/57.5 mg/m2 twice daily alone and in combination with RIF 10 mg/kg daily was analyzed in pediatric and adult patients. The AUC of LPV/r decreased more in children than in adults, due to the longer absorption and transit times of LPV and RTV in children. Another bactericidal antibiotic, rifabutin (RFB), has also been shown to interact with the HAART regimen. A study by Narita et al. demonstrated that the combination of oral RFB 300 mg and PIs, including indinavir (IDV) administered 800 mg, 1000 mg, or 1200 mg every 8 h, or 1200 mg twice daily, or NFV (1000 mg or 1250 mg twice daily), is effective in HIV/TB coinfection. Indeed, RFB retains its bactericidal activity, while PIs continue to suppress HIV without increasing side effects [128].

Studies focusing on malaria, all conducted in Africa, reported that the most prescribed drugs for HIV/malaria patients are the antimalarial agents artemether-lumefantrine (AL), dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine (DPQ), artesunate/amodiaquine (AS/AQ) and the anti-HIV drugs NVP, EFV, and LPV/r. In particular, the study conducted by Byakika-Kibwika et al. [120] analyzed potential DDIs between oral AL 80/480 mg and oral EFV 600 mg daily or NVP 200 mg daily for 2 weeks, than 200 mg twice daily. The results showed that when AL is taken together with EFV or NVP, patient exposure to the anti-malarian drug is reduced. This could be due to the ability of EFV and NVP to increase CYP3A4 activity, resulting in an accelerated metabolism of drugs metabolized by this enzyme isoform, such as AL [133,134,135]. The authors concluded that this effect could lead to the failure of anti-malarian treatment [120]. This evidence is supported in the study by Scarsi et al. [124] in which the potential DDIs between drugs in the HAART regimen, such as zidovudine (AZT), lamivudine (3TC), and NVP coformulated in a single 200/300/150 mg tablet and oral AS/AQ 80/480 mg, was examined.

In particular, the relationship between the AUC of the metabolite desethylamodiaquine (DEAQ) and the progenitor drug (amodiaquine) was measured. The results revealed that patients taking this HAART regimen had reduced exposure to AS or its metabolite DEAQ due to the ability of NVP to induce CYP3A4 and CYP2B6 enzyme isoforms. Indeed, although to a lesser extent than CYP2C8, these enzymes are involved in the metabolism of the antimalarial agent.

Two studies by Wallender et al. Sevene et al. [118,125], which enrolled 83 and 221 patients respectively, discussed potential DDIs between DPQ 40 mg for the first and 320 mg for the latter study and oral EFV 50 mg, due to EFV-mediated CYP3A4 induction. This led to an increase in piperaquine (PQ) clearance, compromising the efficacy of chemoprophylaxis with dihydroartemisinin-PQ (DHA-PQ) and making the monthly regimen insufficient to prevent malaria. It is suggested that daily administration of low-dose DHA-PQ (320 or 160 mg PQ) might be a promising strategy to overcome the effects of these DDIs. In addition, switching to a DTG-based antiretroviral regimen could improve the clinical outcomes of HIV+ pregnant women [118]. Moh et al. found that the combination of oral AZT 300 mg and oral cotrimoxazole (TMP-SMX) 160/800 mg, caused significant adverse effects, including increased hematological toxicity, such as neutropenia and anaemia. These effects were more common when the drugs were used together rather than separately. This is because AZT inhibits beta-globin gene expression, resulting in bone marrow toxicity and a dose-dependent reduction of the neutrophil count. Similarly, TMP-SMX can cause neutropenia and anaemia by inhibiting dihydrofolate reductase in a dose-dependent manner [129].

5. Studies Investigating DDIs Between HAART and Co-Administered Drugs Used for the Treatment of HCV in Healthy and HIV/HCV Co-Infected Patients

Chronic HCV infection is a major cause of morbidity and death in PLWH [136]. Indeed, HIV/HCV co-infected patients have a higher risk of developing advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis than HCV monoinfected patients. This makes the treatment of HCV infection a priority in PLWH [137]. However, combining antiviral regimens in the co-infected population can be complex, as the therapies may share overlapping PK, especially with regard to metabolism or elimination that may result in DDIs [138].

Twenty-five studies involving 2635 subjects treated with HAART and anti-HCV drugs were analyzed. Seventeen studies enrolled healthy volunteers and 8 patients with HIV/HCV co-infection (Table 4). Of these 25 studies, 10 are RCTs [139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148], 10 are PK studies [149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158], 2 are defined as PK-DDI studies [159,160] and one is a retrospective/prospective study [161]. For the remaining 2 [162,163], the study design is not reported (Table 4). Numerous studies have analyzed the PK, safety and tolerability of different antiviral drug combinations. However, they were mainly conducted in healthy volunteers, thus making comparison with studies that evaluated the same drug combination on HIV/HCV co-infected patients very difficult.

Table 4.

Studies, published between 2000 and 2024, investigating DDIs between HAART and co-administered drugs used for the treatment of HCV in healthy and HIV/HCV co-infected patients. All drugs reported in these studies were orally administered.

As early as 2003 and 2004, Carrat et al. and Poizot-Martin et al. [139,161], evaluated the efficacy and tolerance of anti-HCV treatment with interferon (IFN) or Peg-Interferon (PegIFN) and ribavirin (RBV) in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. The study by Carrat et al. reported treatment with oral RBV 400 mg twice daily plus subcutaneous PegIFN alpha-2b 1.5 µg/kg once a week or standard subcutaneous IFN alpha-2b 3 million units three times a week for 48 weeks [139]. Poizot-Martin et al. reported the cases of patients who received oral RBV 800 mg, two tablets daily, and Peg-IFN 180 mg once a week or IFN-alpha-2b 3 MU three times a week for at least 6 months and up to 12 months [161].

Both studies reported a reduction in Sustained Virological Response (SVR) in patients taking HAART drugs, in particular PIs. Furthermore, an increase in serious ADEs was observed in HIV+ patients compared to HIV-negative patients, especially when they were taking older NNRTis such as didanosine [139]. In contrast, studies by Chung et al. and Torriani et al. [140,141], evaluating the same treatment regimen with almost identical dosage in co-infected patients, showed that the use or non-use of antiretrovirals and the use or non-use of PIs were not predictive of SVR. However, Chung et al. [140] confirmed the concern about ADEs occurring in regimens including didanosine, probably due to increased intracellular concentrations of its active metabolites.

Notably, over the past two decades, the only standard treatment for HCV-infected patients was PegIFN/RBV, but only a limited percentage of patients managed to achieve SVR. With the subsequent introduction of DAAs into clinical practice (in 2011), the cure rate of chronic HCV increased significantly [164]. DAAs are divided into three main classes based on their targets in HCV: PIs of the non-structural protein 3/4A (NS3/4A), which can inhibit HCV polyprotein processing; NS5A inhibitors, which inhibit viral replication and assembly; and NS5B polymerase inhibitors, which can block HCV RNA replication [165]. Various detrimental PK DDIs were identified when DAAs were administered with PIs/r in healthy volunteers but the same DDIs were not investigated in patients.

Hulskotte et al. conducted a randomized, open-label study to evaluate PK interactions between oral boceprevir (BOC) 800 mg, an HCV serine protease NS3 inhibitor, taken 3 times daily and PIs/r (ATV/r 300 mg daily, DRV/r 600 mg twice daily, LPV/r 400 mg twice daily each with RTV 100 mg) in 39 healthy adults, demonstrating that such co-administration can result in reduced exposure of both PIs and BOC. However, the treatments were overall well tolerated [142]. The following year, a similar PK study was conducted in 14 HIV/HCV patients taking oral ATV/r 300/100 mg daily and a triple therapy for chronic hepatitis C based on oral telaprevir (TVR) 1125 mg twice daily, a HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor, PegIFN alpha, and RBV. PK profiles were assessed before and after switching from ATV/r to unboosted ATV (200 mg twice daily). Similarly to what was reported on BOC, the co-administration of TVR with ATV/r resulted in reduced exposure of both drugs compared with administration without the booster [149]. The observed DDIs can be surely explained by the involvement of CYP3A4/5 and P-gp-dependent mechanism of which PIs, BOC, and TVR are substrates and inhibitors. As matter of the fact, the concomitant use of these drugs with several HAART components is not recommended [166]. Since these bidirectional DDI, it is very difficult to assess the relative contribution of each drug to the observed results. Unlike the previous two studies [142,149], Khatri et al. study [151], which consisted of five PK studies of Phase 1 involving 144 healthy volunteers, has shown that the 3D regimen consisting of ombitasvir (25 mg once daily), paritaprevir/ritonavir (150/100 mg once daily), and dasabuvir (250 or 400 mg twice daily)—OBV/PTV/r + DSV)—is not recommended with the evening intake of oral ATV/r 300/100 mg and oral LPV/r 800/200 mg due to higher exposure to PTV or RTV. This may be partially due to the increased daily dose of RTV (200 mg/day for the evening dosing regimen compared with 100 mg/day for the morning dosing regimen) and the resulting inhibition of the metabolism of PTV. In addition, being a substrate of CYP3A, OATP1B1 and OATP1B3, PTV may be subjected to the inhibitory effects on these proteins exerted by ATV and RTV. An increase in total bilirubin levels was identified in the ATV arm, but no serious ADEs were reported.

Similarly, DDI studies were conducted in healthy volunteers also to evaluate the effect of RTV on the PK of an oral dose of grazoprevir (GZR) 200 mg, an NS3/4A protease inhibitor, and oral elbasvir (EBR) 50 mg daily, an NS5A inhibitor, when co-administered with oral ATV/r 300/100 mg daily, oral LPV/r 400/100 mg twice daily, or oral DRV/r 600/100 mg twice daily. These studies, having demonstrated increased exposure to GZR when GZR-EBR are co-administered with PIs/r, suggested that the use of HIV treatment regimens lacking PIs/r should be considered in HIV/HCV-co-infected individuals who need to be treated with these two DAAs [152]. Again, Kosloski et al. [159], which evaluated the PK of oral glecaprevir (GLE) 300 mg, an NS3/4A protease inhibitor, and pibrentasvir (PIB) 120 mg, an NS5A inhibitor, when administered orally alone or in combination with anti-HIV agents, the AUC of GLE was found to be increased (by more than 4-fold) when taken with PIs/r (ATV/r 300/100 mg daily, DRV/r 800/100 mg daily, 400/100 mg twice daily), while PIB concentrations were not affected. In contrast, GLE and PIB exposure was significantly reduced following concomitant intake of oral EFV 600 mg daily. Increases in alanine transaminase occurred in combination with ATV/r [159]. In conclusion, based on the available literature, NS5A inhibitors represent the class of DAAs less affected by the concomitant PI/r intake.

Among NS5A inhibitors, daclatasvir (DCV) has limited influence on CYP3A4 compared with NS3 PIs, making it unable to influence patient exposure to HAART components. In fact, DCV, although a substrate and inhibitor of P-gp, is not a strong CYP3A4 inhibitor [167]. Nonetheless, because DCV is a substrate of CYP3A4, it can be involved in DDIs with potent inhibitors or inducers of the CYP450 system resulting in requirement of dose adjustments [153]. In contrast, co-administration of EFV appears to influence plasma levels of the NS5A and NS3/4A inhibitors. Similar to the study by Kosloski et al. [159], which found a significant reduction in exposure of GLE and PIB when co-administered with EFV, Sabo et al. [154] found a significant reduction in plasma levels of oral faldaprevir (FDV) 240 mg daily, a NS3/4A inhibitor, when co-administered with oral EFV 600 mg daily, consistent with EFV-dependent induction of CYP3A. This decrease could be managed by using the higher dose of the 2 doses of FDV tested in the phase 3 studies [154]. Mogalian et al. [143] found an approximately 50% reduction in exposure of oral velpatasvir (VEL) 100 mg, an NS5A inhibitor, when combined with oral sofosbuvir (SOF) 400 mg, an HCV polymerase inhibitor, and oral EFV 600 mg daily. Of note, in contrast to the aforementioned data, Sabo et al. [154] failed to find clinically significant DDIs when oral FDV was taken with oral DRV/r 800/100 mg daily.

INIs have also been shown to give potential DDIs with antiviral drugs used for HCV treatment. In 2011, Ashby et al. observed no statistically significant differences in the PK parameters of oral RAL 400 mg twice daily when taken alone or with a single oral dose of RBV 800 mg in healthy volunteers [155]. Since RAL is eliminated after UGT1A1-mediated glucuronidation and is a substrate of P-gp [168,169], Joseph et al. [156] evaluated the co-administration of oral FDV 240 mg twice daily, a UGT1A1 inhibitor, and of oral RAL 400 mg twice daily in 24 healthy subjects. Compared to RAL alone, co-administration of FDV resulted in a 2.7-fold and 2.5-fold increase in the mean AUC and Cmax of RAL, respectively. Of note, the incidence of ADEs, especially gastrointestinal disorders, was also higher during combination treatment compared to treatment with RAL alone. RAL is also inhibited by OBV, PTV and DSV [170]. The study by Khatri et al. [157], investigated the effects of combining oral RAL 400 mg twice daily with these inhibitors (PTV/r 150/100 mg daily, OBV25 mg daily, and DSV400 mg twice-daily) in healthy volunteers, showing a 100 to 134% increase in AUC and Cmax of RAL. However, we found only one prospective study that evaluated the PK profile of RAL when co-administered with OBV/PTV/r + DSV regimen in HCV-co-infected PLWH [150]. In particular, this study assessed the PK of oral RAL 400 mg twice daily before and during combined administration of oral OBV/PTV/r 25/150/100 mg once daily + DSV 250 mg twice daily regimen in patients with HIV/HCV co-infection. Contrary to expectations, a decrease in RAL exposure was observed during co-administration of HCV therapy. The authors suggested that this could be due to the rapid elimination of HCV induced by the use of potent DAAs and the consequent reduction of inflammation, restoration of hepatocyte function, and drug-metabolising enzyme activities, including UGT1A1 [171]. Furthermore, viral infections, inflammatory responses, and subsequent tissue damage are also known to alter P-gp gene expression [172,173]. This emphasizes that the results obtained in healthy subjects can be very different from those found in patients due to disease-specific factors (e.g., comorbidity and therapeutic adherence) that strongly contribute to PK variability.

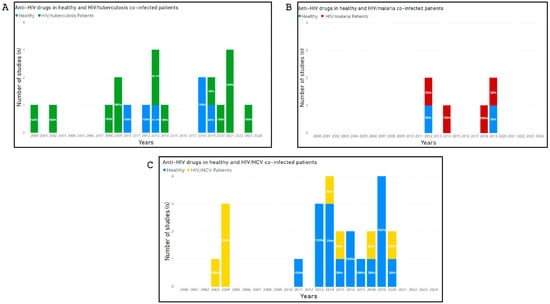

Studies that investigated potential DDI-related adverse outcomes involving drugs belonging to HAART and drugs co-administered for the treatment of co-infections (malaria, tuberculosis and HCV) were shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Number of studies published between 2000 and 2024, that investigated potential DDI-related adverse outcomes involving drugs belonging to HAART and drugs co-administered for the treatment of co-infections (malaria, tuberculosis and HCV). The percentages of studies, calculated from the total number of studies published year by year, are marked within each histogram. (Panel A) shows the number of studies, conducted in HIV mono-infected and HIV/Malaria co-infected patients, that investigated potential DDI-related adverse outcomes involving drugs belonging to HAART and drugs co-administered for the treatment of malaria. (Panel B) shows the number of studies, conducted in HIV/Tuberculosis co-infected patients, that investigated potential DDI-related adverse outcomes involving drugs belonging to HAART and drugs co-administered for the treatment of Tuberculosis. (Panel C) shows the number of studies, in healthy volunteers and HIV/HCV co-infected patients, that investigated potential DDI-related adverse outcomes involving drugs belonging to HAART and drugs co-administered for the treatment of HCV.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The introduction of HAART has led to a significant increase in the life expectancy of PLWH. Although this represents an undisputed success of medical-scientific progress, physicians are faced with the complexity of managing patients suffering from several comorbidities and thus undergoing multiple treatments. One of the most relevant consequences is the occurrence of DDI-related ADEs, which were not easily detected during RCTs involving drugs (although commonly used) in these patients. Therefore, it is important to identify and thoroughly investigate clinically relevant DDIs and to define the most appropriate therapeutic approaches.

This is particularly important in HIV co-infected patients. For instance, individuals with HIV/HCV co-infection treated concomitantly with antivirals for HCV and HIV account for about 6% of HIV mono-infected patients worldwide (almost 2 million individuals) [174,175]. Other concerns are HIV+ patients co-infected with malaria or TB that have been enrolled in studies performed in countries where these HIV coinfections are prevalent, such as Africa [113,114,116,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,127,129,131] and South-East Asia [119,128,130].

In the present study we reviewed 134 studies published over the last two decades, that collectively emphasize the importance of investigating DDI-related adverse outcomes involving HAART components and drugs co-administered for the treatment of comorbidities in PLWH.

With regard to DDIs involving HAART, most of the studies (84%) were conducted in healthy volunteers, 40% of them reported DDI-related ADEs, including the need to change the drug dosage or the recommendation to avoid (or to pay special attention to) certain combination therapies.

In the early 2000s, PIs and NNRTIs were the main used pharmacological agents. In 2002, Fichtenbaum et al. assessed potential clinically relevant DDIs between statins (oral simvastatin, ATO or PRAV) 40 mg, and the oral PIs SQV 400 mg, RTV 400 mg and NFV 1250 mg in 56 healthy volunteers. The authors concluded that concentrations of simvastatin or ATO significantly increased when combined with SQV/r. Moreover, because of decreased concentration, the authors suggested that it may be necessary to adjust the dosage of PRAV [25].

A potential DDI involving another PI (i.e., IDV) was subsequently studied in 25 HIV+ patients, 12 treated with oral FLUV 20 mg or 40 mg daily, and 13 with oral PRAV 10 mg or 20 mg daily. However, the authors, without measuring plasma concentration of statins, found no changes in lipid parameters [112]. Based on these results it is not possible to establish the real effect of DDIs between PIs and statins.

Potential DDI-related ADEs have been studied between HAART components such as maraviroc (MVC), SQV/r and the antifungal ketoconazole (KCZ), which is a strong inhibitor of the CYPP450 system [17,34]. Regarding MVC, an increased in its plasma levels was reported without any recommendation [17]. No dose adjustment was suggested when SQV/r (1000/100 mg twice daily) was taken with 200 mg KCZ once daily, while using high doses of KCZ (>200 mg/day) were suggested to be avoided [34]. Again, it is not possible to establish the impact of these drug combinations in clinical practice due to the absence of studies enrolling HIV+ patients receiving this therapy.

One of the most important innovations in HIV treatment has been the introduction of INIs, such as RAL and DTG. The increasing complexity of the management of HIV infection necessitated a thorough examination of potential effects and PD of these antivirals in combination with other drugs. In this regard, several studies (including RCTs) have been performed in healthy volunteers, while no research has been conducted in HIV+ patients. It is noteworthy that studies in healthy subjects did not reveal any clinically significant effects of combining RAL with drugs commonly used for the treatment of HIV comorbidities. The study by Iwamoto et al. is an exception, as they report that plasma levels of RAL 400 mg are increased when co-administered with oral OME 20 mg, probably due to an increased bioavailability of oral RAL 400 mg due to an increase in gastric pH [29].

The use of potent inducers of UGT1A1 and CYP3A4, such as CBZ, may cause alteration in the PK of INIs. Song et al. showed a statistically significant decrease in AUC(0-τ), Cmax and Cτ of DTG following CBZ co-administration. This was considered a clinically relevant DDI, so much so that the authors suggested doubling the daily administration of DTG [60]. Other studies have suggested other possible clinically relevant DDIs involving DTG. One of them reported an increase in AUC and Cmax of MET [63] and another a decrease in oral DTG 50 mg absorption, in case of concomitant use of oral calcium 1200 mg and iron supplements 324 mg [56].

Eight reviewed studies explored DDIs between drugs belonging to HAART and drugs belonging to different therapeutic classes in HIV+ patients. Most of them [103,104,105,108,110] concerned the use of contraceptives and demonstrated clinically relevant DDIs. In fact, the SmPCs of LPV and RTV recommend the use of additional contraceptive methods due to the risk of reducing contraceptive efficacy. Similar results were found regarding the combination of EFV with ENG [108] and EFV or NVP with ETON [110]. Notably, this evidence of DDI-related adverse outcome was not marched in studies that enrolled healthy volunteers [18,23,62,65,83].

Apart from studies on the use of contraceptives, the only authors publishing results of ADEs following co-administration of HAART components and other drugs were Rudek et al., who reported grade 3 neutropenia and grade 1/2 diarrhea, mucositis, and fatigue in HIV+ patients with cancer, already treated with RTV, receiving sunitinib due to the RTV-dependent CYP3A4 inhibitory effect [106].

The antivirals used to control anti-HIV and anti-HCV drugs, which are used in multiple therapeutic regimens, are often victims or perpetrators of DDIs involving drug transport proteins or metabolizing enzymes. Data on the treatment of HCV infection in HIV/HCV co-infected patients were scarce until 2004, when data on co-infected populations treated with standard IFN plus RBV or PegIFN plus RBV were reported in three RCTs [139,140,141]. This treatment resulted in lower SVR rates in patients with coinfection compared to those with HCV infection alone [139]. Virological failure was mainly observed in patients taking concomitant HIV-PIs [139,161]. Furthermore, antiviral treatment of both infections often resulted in ADEs that required dose reduction or drug discontinuation, especially when didanosine was also used [139]. Consequently, a warning has been added to the product information for didanosine indicating that RBV is contraindicated in patients also receiving this NRTI [176]. No studies in healthy volunteers were found analyzing the SVR rates and safety profile of the above drug combinations.

Following the introduction in 2011–2012 of first-generation DAAs, TVR and BOC in combination with pegIFN and RBV, SVR rates in patients with HIV and HCV genotype 1 coinfection have improved significantly [177,178]. However, as TVR and BOC are CYP3A4 inhibitors, several evidence on DDIs with drugs included in HAART, (especially the PIs/r), and with other drugs commonly used to treat comorbidities, have accumulated in the following years [142,149]. Thus, given the limited safety data, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did not approve the use of TVR and BOC in the co-infected population.

New generation DAAs, which did not require concomitant IFN, revolutionized HCV treatment. They represented an improvement especially for co-infected patients, having eliminated the outcome gap that existed between mono- and co-infections. The combination of SOF, the first approved nucleotide analogue inhibitor of the HCV NS5B polymerase (in 2013), and RBV was the first IFN-free HCV regimen approved for co-infected patients. Furthermore, SOF has a high barrier to resistance, compared to previous DAAs [179], and as it is neither induced nor inhibited by CYP enzymes, PK studies have shown little or no DDIs with a wide range of antiretroviral agents. However, there are some DDIs related to intestinal P-gp, so it should not be co-administered with drugs inducing P-gp, such as RIF [180]. Subsequently, other HCV PIs were introduced, such as paritaprevir, GZR, GLE, as well as other NS5A inhibitors, including ledipasvir, DCV and VEL. As these drugs are always administered in multiple therapeutic regimens several DDI-related clinically relevant outcomes have been shown, especially involving PIs [151,152]. Moreover, according to the available literature, co-administration of PI/r and EFV also seems to influence the plasma levels of the newer NS3/4A and NS5A inhibitors.

Plasma exposure to RAL also appears to be influenced by anti-HCV drugs, depending on whether it is measured in healthy volunteers or in co-infected patients. In this regard, it should be emphasized that the studies that have evaluated DDIs between drugs included in HAART and DAAs, differently by those on the obsolete HAART-IFN+RBV regimen, are almost all conducted in healthy volunteers.

Most of the reviewed studies report inductive or inhibitory effects of drugs included in HAART on enzyme isoforms, especially CYP3A4 and UGT1A1.

For instance, PIs/r, by inhibiting CYP3A4, may increase exposure to drugs commonly used for contraception such as DMPA and NGMN, for erectile dysfunction such as TAD, or for the treatment of co-infections such as PRB/r and GZR. DTG, on the other hand, by inhibiting the organic cationic transporter OCT2, may increase plasma levels of the hypoglycaemic MET.

On the other hand, the drugs mainly involved in enzyme induction are PIs/r such as FPV/r and LPV/r and TPV/r which, by inducing CYP1A2 and UGT1A1 isoforms respectively, can reduce exposure to OLZ, BUP and DTG. In addition, EFV, by inducing CYP3A4, may reduce levels of LNG, ENG, ETON, AL DHA-PQ and GZR.

Notably, drugs belonging to HAART are themselves substrates of the aforementioned enzymes. As a consequence, for example, plasma levels of CAB may be reduced by the inducing effects of RIF on CYP3A4 and UGT1A1, while increased exposure to RAL may be due to inhibitory effect exerted by FDV on UGT1A1.

In conclusion, the data available in the literature suggest that the management of both mono-infected and co-infected PLWH requires that DDI-related outcomes should not be underestimated.

Unfortunately, there is often lack of congruence between studies both in terms of number, drugs involved, and results obtained. This represents a crucial issue from the perspective of clinical pharmacology. In fact, some studies (actually most of those reviewed here), presenting data on the mechanism of action and presumed clinical relevance of potential DDI-related ADEs related to, were conducted in healthy volunteers without being replicated in HIV+ patients.

Infrequently have the same drug combinations been studied in both healthy subjects and patients. However, as factors such as inflammatory status, loss of activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes, and reduced adherence to therapy may influence exposure to HIV and HCV antivirals, the predicted DDIs in HIV/HCV populations may not be the same as those observed in studies with healthy participants. This hampered the evaluation of the impact of DDIs to define the most appropriate treatment in PLWH.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing—original draft, V.C., E.D.B., A.F. and G.C.; data curation, V.C., V.M., F.S., P.P. and A.F.; writing-original draft, E.D.B., D.D., A.Z., A.P. and I.M.; methodology, S.M.M., D.D. and A.Z.; supervision, A.F., G.C. and P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the winning project of the Gilead’s 2023 Fellowship Program. Funding number: 300397FAC23.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Deeks, S.G.; Lewin, S.R.; Havlir, D.V. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet 2013, 382, 1525–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorolajal, J.; Hooshmand, E.; Mahjub, H.; Esmailnasab, N.; Jenabi, E. Survival rate of AIDS disease and mortality in HIV-infected patients: A meta-analysis. Public Health 2016, 139, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.Y.; Wu, H.Y.; Yarla, N.S.; Xu, B.; Ding, J.; Lu, T.R. HAART in HIV/AIDS Treatments: Future Trends. Infect. Disord.-Drug Targets 2018, 18, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, O.; Robillard, K.; Chan, G.N.; Bendayan, R. The complexities of antiretroviral drug-drug interactions: Role of ABC and SLC transporters. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 31, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubary, F.; Hughes, M.D. Assessing agreement in the timing of treatment initiation determined by repeated measurements of novel versus gold standard technologies with application to the monitoring of CD4 counts in HIV-infected patients. Stat. Med. 2010, 29, 1932–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoko, A.; Pals, S.; Ngugi, T.; Katiku, E.; Joseph, R.; Basiye, F.; Kimanga, D.; Kimani, M.; Masamaro, K.; Ngugi, E.; et al. Retrospective longitudinal analysis of low-level viremia among HIV-1 infected adults on antiretroviral therapy in Kenya. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 63, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- So-Armah, K.; Benjamin, L.A.; Bloomfield, G.S.; Feinstein, M.J.; Hsue, P.; Njuguna, B.; Freiberg, M.S. HIV and cardiovascular disease. Lancet HIV 2020, 7, e279–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, V.; Sellitto, C.; Torsiello, M.; Manzo, V.; De Bellis, E.; Stefanelli, B.; Bertini, N.; Costantino, M.; Maci, C.; Raschi, E.; et al. Identification of Drug Interaction Adverse Events in Patients With COVID-19: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e227970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, V.; Bertini, N.; Ricciardi, R.; Stefanelli, B.; De Bellis, E.; Sellitto, C.; Cascella, M.; Sabbatino, F.; Corbi, G.; Pagliano, P.; et al. Adverse events related to drug-drug interactions in COVID-19 patients. A persistent concern in the post-pandemic era: A systematic review. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2024, 20, 275–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; McNicholl, I.; Custodio, J.M.; Szwarcberg, J.; Piontkowsky, D. Drug Interactions with Cobicistat- or Ritonavir-Boosted Elvitegravir. AIDS Rev. 2016, 18, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galli, L.; Parisi, M.R.; Poli, A.; Menozzi, M.; Fiscon, M.; Garlassi, E.; Francisci, D.; Di Biagio, A.; Sterrantino, G.; Fornabaio, C.; et al. Burden of Disease in PWH Harboring a Multidrug-Resistant Virus: Data From the PRESTIGIO Registry. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetta, C.; Tu, N.Q.; Delelis, O. Different Pathways Conferring Integrase Strand-Transfer Inhibitors Resistance. Viruses 2022, 14, 2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, M.J.; Petrozzino, J.J. An evidence-based review of treatment-related determinants of patients’ nonadherence to HIV medications. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2009, 23, 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva-Moreno, J.; Trapero-Bertran, M. Economic Impact of HIV in the Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Era—Reflections Looking Forward. AIDS Rev. 2018, 20, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maio, S.; Baldacci, S.; Simoni, M.; Angino, A.; Martini, F.; Cerrai, S.; Sarno, G.; Pala, A.; Bresciani, M.; Paggiaro, P.; et al. Impact of asthma and comorbid allergic rhinitis on quality of life and control in patients of Italian general practitioners. J. Asthma 2012, 49, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.E.; Woolley, I.J.; Russell, D.B.; Bisshop, F.; Furner, V. HIV in practice: Current approaches and challenges in the diagnosis, treatment and management of HIV infection in Australia. HIV Med. 2018, 19 (Suppl. S3), 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S.; Russell, D.; Taylor-Worth, R.J.; Ridgway, C.E.; Muirhead, G.J. Effects of CYP3A4 inhibitors on the pharmacokinetics of maraviroc in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 65 (Suppl. S1), 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.S.; Hanley, W.D.; Moreau, A.R.; Jin, B.; Bieberdorf, F.A.; Kost, J.T.; Wenning, L.A.; Stone, J.A.; Wagner, J.A.; Iwamoto, M. Effect of raltegravir on estradiol and norgestimate plasma pharmacokinetics following oral contraceptive administration in healthy women. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 71, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankrom, W.; Jackson Rudd, D.; Zhang, S.; Fillgrove, K.L.; Gravesande, K.N.; Matthews, R.P.; Brimhall, D.; Stoch, S.A.; Iwamoto, M.N. A phase 1, open-label study to evaluate the drug interaction between islatravir (MK-8591) and the oral contraceptive levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol in healthy adult females. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonk, M.; Colbers, A.; Poirters, A.; Schouwenberg, B.; Burger, D. Effect of ginkgo biloba on the pharmacokinetics of raltegravir in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5070–5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blonk, M.I.; Langemeijer, C.C.; Colbers, A.P.; Hoogtanders, K.E.; van Schaik, R.H.; Schouwenberg, B.J.; Burger, D.M. Pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction study between raltegravir and citalopram. Antivir. Ther. 2016, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüggemann, R.J.; van Luin, M.; Colbers, E.P.; van den Dungen, M.W.; Pharo, C.; Schouwenberg, B.J.; Burger, D.M. Effect of posaconazole on the pharmacokinetics of fosamprenavir and vice versa in healthy volunteers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 2188–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, E.R.; Bisdomini, E.; Penchala, S.D.; Khoo, S.; Nwokolo, N.; Boffito, M. Pharmacokinetics (PK) of ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel co-administered with atazanavir/cobicistat. HIV Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 20, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, A.F.; Damle, B.D.; LaBadie, R.R.; Crownover, P.H.; Hewlett, D.; Glue, P.W. Significant decrease in nelfinavir systemic exposure after omeprazole coadministration in healthy subjects. Pharmacotherapy 2008, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fichtenbaum, C.J.; Gerber, J.G.; Rosenkranz, S.L.; Segal, Y.; Aberg, J.A.; Blaschke, T.; Alston, B.; Fang, F.; Kosel, B.; Aweeka, F.; et al. Pharmacokinetic interactions between protease inhibitors and statins in HIV seronegative volunteers: ACTG Study A5047. AIDS 2002, 16, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, K.; Humeniuk, R.; West, S.; Wei, L.; Ling, J.; Graham, H.; Martin, H.; Stamm, L.; Mathias, A. Lack of clinically relevant drug interactions between bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide and ledipasvir/sofosbuvir or sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 21 (Suppl. S8), 170–171. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Allen, L.; Huang, D.B.; Moy, F.; Vinisko, R.; Nguyen, T.; Rowland, L.; MacGregor, T.R.; Castles, M.A.; Robinson, P. Evaluation of steady-state pharmacokinetic interactions between ritonavir-boosted BILR 355, a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, and lamivudine/zidovudine in healthy subjects. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2012, 37, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, M.; Wenning, L.A.; Petry, A.S.; Laethem, M.; De Smet, M.; Kost, J.T.; Breidinger, S.A.; Mangin, E.C.; Azrolan, N.; Greenberg, H.E.; et al. Minimal effects of ritonavir and efavirenz on the pharmacokinetics of raltegravir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 4338–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Iwamoto, M.; Wenning, L.A.; Nguyen, B.Y.; Teppler, H.; Moreau, A.R.; Rhodes, R.R.; Hanley, W.D.; Jin, B.; Harvey, C.M.; Breidinger, S.A.; et al. Effects of omeprazole on plasma levels of raltegravir. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 489–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, B.S.; Colbers, A.P.; Velthoven-Graafland, K.; Schouwenberg, B.J.; Burger, D.M. Effect of fosamprenavir/ritonavir on the pharmacokinetics of single-dose olanzapine in healthy volunteers. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2014, 44, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jann, M.W.; Spratlin, V.; Momary, K.; Zhang, H.; Turner, D.; Penzak, S.R.; Wright, A.; VanDenBerg, C. Lack of a pharmacokinetic drug-drug interaction with venlafaxine extended-release/indinavir and desvenlafaxine extended-release/indinavir. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 715–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Desta, Z.; Shon, J.H.; Yeo, C.W.; Kim, H.S.; Liu, K.H.; Bae, S.K.; Lee, S.S.; Flockhart, D.A.; Shin, J.G. Effects of clopidogrel and itraconazole on the disposition of efavirenz and its hydroxyl metabolites: Exploration of a novel CYP2B6 phenotyping index. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justesen, U.S.; Klitgaard, N.A.; Brosen, K.; Pedersen, C. Pharmacokinetic interaction between amprenavir and delavirdine after multiple-dose administration in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003, 55, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kaeser, B.; Zandt, H.; Bour, F.; Zwanziger, E.; Schmitt, C.; Zhang, X. Drug-drug interaction study of ketoconazole and ritonavir-boosted saquinavir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuda, T.N.; Schöller-Gyüre, M.; De Smedt, G.; Beets, G.; Aharchi, F.; Peeters, M.P.; Vandermeulen, K.; Woodfall, B.J.; Hoetelmans, R.M. Assessment of the steady-state pharmacokinetic interaction between etravirine administered as two different formulations and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in healthy volunteers. HIV Med. 2009, 10, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuda, T.N.; Woodfall, B.; De Marez, T.; Peeters, M.; Vandermeulen, K.; Aharchi, F.; Hoetelmans, R.M. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of the interaction between etravirine and rifabutin or clarithromycin in HIV-negative, healthy volunteers: Results from two Phase 1 studies. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2014, 69, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasserra, C.; O’Mara, E. Pharmacokinetic interaction of vicriviroc with other antiretroviral agents: Results from a series of fixed-sequence and parallel-group clinical trials. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2011, 50, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kearney, B.P.; Mathias, A.; Mittan, A.; Sayre, J.; Ebrahimi, R.; Cheng, A.K. Pharmacokinetics and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on coadministration with lopinavir/ritonavir. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2006, 43, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Porte, C.; Verweij-van Wissen, C.; van Ewijk, N.; Aarnoutse, R.; Koopmans, P.; Reiss, P.; Stek, M.; Hekster, Y.; Burger, D. Pharmacokinetic interaction study of indinavir/ritonavir and the enteric-coated capsule formulation of didanosine in healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2005, 45, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, G.; Zou, C.; Huang, J.; Kuang, Y.; Shen, K.; Zhang, B.; Yang, S.; Xiang, H.; et al. Study on Pharmacokinetic Interactions Between HS-10234 and Emtricitabine in Healthy Subjects: An Open-Label, Two-Sequence, Self-Controlled Phase I Trial. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallikaarjun, S.; Wells, C.; Petersen, C.; Paccaly, A.; Shoaf, S.E.; Patil, S.; Geiter, L. Delamanid Coadministered with Antiretroviral Drugs or Antituberculosis Drugs Shows No Clinically Relevant Drug-Drug Interactions in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5976–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Matthews, R.; Rudd, D.; Fillgrove, K.; Fox-Bosetti, S.; Levine, V.; Zhang, S.; Tomek, C.; Stoch, A.; Iwamoto, M. No Difference in MK-8591 and Doravirine Pharmacokinetics After Co-Administration. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5 (Suppl. S1), S203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moltó, J.; Bailón, L.; Pérez-Mañá, C.; Papaseit, E.; Miranda, C.; Martín, S.; Mothe, B.; Farré, M. Absence of drug-drug interactions between γ-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and cobicistat. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 77, 181–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.A.; Lopez-Lazaro, L.; Jung, D.; Methaneethorn, J.; Duparc, S.; Borghini-Fuhrer, I.; Pokorny, R.; Shin, C.S.; Fleckenstein, L. Drug-drug interaction analysis of pyronaridine/artesunate and ritonavir in healthy volunteers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 86, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, M.; Decosterd, L.; Fayet, A.; Lee, J.S.; Margol, A.; Kanani, M.; di Iulio, J.; von Schoen-Angerer, T.; Jelliffe, R.; Calmy, A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of once-daily raltegravir and atazanavir in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4619–4625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.; Song, I.; Borland, J.; Patel, A.; Lou, Y.; Chen, S.; Wajima, T.; Peppercorn, A.; Min, S.S.; Piscitelli, S.C. Pharmacokinetics of the HIV integrase inhibitor S/GSK1349572 co-administered with acid-reducing agents and multivitamins in healthy volunteers. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2011, 66, 1567–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pene Dumitrescu, T.; Greene, T.J.; Joshi, S.R.; Xu, J.; Johnson, M.; Halliday, F.; Butcher, L.; Zimmerman, E.; Webster, L.; Pham, T.T.; et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic interaction between the HIV-1 maturation inhibitor GSK3640254 and combination oral contraceptives in healthy women. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 88, 1704–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, S.; Abel, S.; Tweedy, S.; West, S.; Hui, J.; Kearney, B.P. Pharmacokinetic interaction of ritonavir-boosted elvitegravir and maraviroc. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 53, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, S.; Kakuda, T.N.; Mack, R.; West, S.; Kearney, B.P. Pharmacokinetics of elvitegravir and etravirine following coadministration of ritonavir-boosted elvitegravir and etravirine. Antivir. Ther. 2008, 13, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, L.L.; Song, I.H.; Arya, N.; Choukour, M.; Zong, J.; Huang, S.P.; Eley, T.; Wynne, B.; Buchanan, A.M. No clinically significant pharmacokinetic interactions between dolutegravir and daclatasvir in healthy adult subjects. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, D.J.; Zhang, S.; Fillgrove, K.L.; Fox-Bosetti, S.; Matthews, R.P.; Friedman, E.; Armas, D.; Stoch, S.A.; Iwamoto, M. Lack of a Clinically Meaningful Drug Interaction Between the HIV-1 Antiretroviral Agents Islatravir, Dolutegravir, and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2021, 10, 1432–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R.I.; Yee, K.L.; Fan, L.; Cislak, D.; Martell, M.; Jordan, H.R.; Iwamoto, M.; Khalilieh, S. Evaluation of the Pharmacokinetics of Metformin Following Coadministration With Doravirine in Healthy Volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 2020, 9, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöller-Gyüre, M.; Kakuda, T.N.; De Smedt, G.; Vanaken, H.; Bouche, M.P.; Peeters, M.; Woodfall, B.; Hoetelmans, R.M. A pharmacokinetic study of etravirine (TMC125) co-administered with ranitidine and omeprazole in HIV-negative volunteers. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 66, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöller-Gyüre, M.; van den Brink, W.; Kakuda, T.N.; Woodfall, B.; De Smedt, G.; Vanaken, H.; Stevens, T.; Peeters, M.; Vandermeulen, K.; Hoetelmans, R.M. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the concomitant administration of methadone and TMC125 in HIV-negative volunteers. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 48, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, V.; Spinosa-Guzman, S.; De Paepe, E.; Stevens, T.; Tomaka, F.; De Pauw, M.; Hoetelmans, R.M. Pharmacokinetics of multiple-dose darunavir in combination with low-dose ritonavir in individuals with mild-to-moderate hepatic impairment. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010, 49, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, I.; Borland, J.; Arya, N.; Wynne, B.; Piscitelli, S. Pharmacokinetics of dolutegravir when administered with mineral supplements in healthy adult subjects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2015, 55, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, I.; Borland, J.; Chen, S.; Guta, P.; Lou, Y.; Wilfret, D.; Wajima, T.; Savina, P.; Peppercorn, A.; Castellino, S.; et al. Effects of enzyme inducers efavirenz and tipranavir/ritonavir on the pharmacokinetics of the HIV integrase inhibitor dolutegravir. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2014, 70, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, I.; Borland, J.; Chen, S.; Lou, Y.; Peppercorn, A.; Wajima, T.; Min, S.; Piscitelli, S.C. Effect of atazanavir and atazanavir/ritonavir on the pharmacokinetics of the next-generation HIV integrase inhibitor, S/GSK1349572. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 72, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Borland, J.; Chen, S.; Patel, P.; Wajima, T.; Peppercorn, A.; Piscitelli, S.C. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 1627–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.; Weller, S.; Patel, J.; Borland, J.; Wynne, B.; Choukour, M.; Jerva, F.; Piscitelli, S. Effect of carbamazepine on dolutegravir pharmacokinetics and dosing recommendation. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 72, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.H.; Borland, J.; Chen, S.; Savina, P.; Peppercorn, A.F.; Piscitelli, S. Effect of prednisone on the pharmacokinetics of the integrase inhibitor dolutegravir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 4394–4397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.H.; Borland, J.; Chen, S.; Wajima, T.; Peppercorn, A.F.; Piscitelli, S.C. Dolutegravir Has No Effect on the Pharmacokinetics of Oral Contraceptives With Norgestimate and Ethinyl Estradiol. Ann. Pharmacother. 2015, 49, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, I.H.; Zong, J.; Borland, J.; Jerva, F.; Wynne, B.; Zamek-Gliszczynski, M.J.; Humphreys, J.E.; Bowers, G.D.; Choukour, M. The Effect of Dolutegravir on the Pharmacokinetics of Metformin in Healthy Subjects. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016, 72, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, I.; Min, S.S.; Borland, J.; Lou, Y.; Chen, S.; Ishibashi, T.; Wajima, T.; Piscitelli, S.C. Lack of interaction between the HIV integrase inhibitor S/GSK1349572 and tenofovir in healthy subjects. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2010, 55, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trezza, C.; Ford, S.L.; Gould, E.; Lou, Y.; Huang, C.; Ritter, J.M.; Buchanan, A.M.; Spreen, W.; Patel, P. Lack of effect of oral cabotegravir on the pharmacokinetics of a levonorgestrel/ethinyl oestradiol-containing oral contraceptive in healthy adult women. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 1499–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Luin, M.; Colbers, A.; Verwey-van Wissen, C.P.; van Ewijk-Beneken-Kolmer, E.W.; van der Kolk, M.; Hoitsma, A.; da Silva, H.G.; Burger, D.M. The effect of raltegravir on the glucuronidation of lamotrigine. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 49, 1220–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vourvahis, M.; Langdon, G.; Labadie, R.R.; Layton, G.; Ndongo, M.N.; Banerjee, S.; Davis, J. Pharmacokinetic effects of coadministration of lersivirine with raltegravir or maraviroc in healthy subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Walimbwa, S.I.; Lamorde, M.; Waitt, C.; Kaboggoza, J.; Else, L.; Byakika-Kibwika, P.; Amara, A.; Gini, J.; Winterberg, M.; Chiong, J.; et al. Drug Interactions between Dolutegravir and Artemether-Lumefantrine or Artesunate-Amodiaquine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01310–e01318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenning, L.A.; Friedman, E.J.; Kost, J.T.; Breidinger, S.A.; Stek, J.E.; Lasseter, K.C.; Gottesdiener, K.M.; Chen, J.; Teppler, H.; Wagner, J.A.; et al. Lack of a significant drug interaction between raltegravir and tenofovir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 3253–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Zhou, X.J.; Fielman, B.A.; Lloyd, D.M.; Chao, G.C.; Brown, N.A. Pharmacokinetics of telbivudine in healthy subjects and absence of drug interaction with lamivudine or adefovir dipivoxil. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2309–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]