Abstract

Lactoferrin is an iron-binding glycoprotein with multiple functions in the body. Its activity against a broad spectrum of both DNA and RNA viruses as well as the ability to modulate immune responses have made it of interest in the pharmaceutical and food industries. The mechanisms of its antiviral activity include direct binding to the viruses or its receptors or the upregulation of antiviral responses by the immune system. Recently, much effort has been devoted to the use of nanotechnology in the development of new antivirals. In this review, we focus on describing the antiviral mechanisms of lactoferrin and the possible use of nanotechnology to construct safe and effective new antiviral drugs.

1. Introduction

Lactoferrin (LF) is a multifunctional glycoprotein present in external secretions, such as colostrum, milk, tears, nasal and bronchial secretions, saliva, bile and pancreatic secretions, urine, seminal and vaginal fluids, and has multiple functions, including as a component of the innate immune response [1,2]. Human lactoferrin (hLF) is constitutively synthetized and secreted by glandular epithelial cells at different epithelial surfaces [1,2]. Moreover, inflammatory processes that recruit neutrophils regulate hLF concentration, since neutrophils secrete secondary granules containing hLF. Lactoferrin belongs to the family of transferrins, and includes approximately 700 amino acids (80 kD) folded into two globular lobes with an α-helix as a linker. LF binds two ferric ions with high affinity, but it can also bind Cu2+, Zn2+ and Mn2+ ions [1,2]. LF has been shown to perform antioxidant, anticancer and anti-inflammatory activities, together with a broad antibacterial, antifungal and virucidal activity [1,2].

LF exists in an iron-free apo-lactoferrin (apoLF) form, while upon iron binding, LF undergoes large conformational changes in which hololactoferrin (hoLF) transforms into either an open or closed state [1,2,3]. Depending on the origin, LF can undergo glycosylation at three sites in humans (Asn-137, Asn-478 and Asn-623) or at five (Asn-233, Asn-368, Asn-476, Asn476, Asn545) in bovine lactoferrin (bLF), being mostly exposed on the outer surface of the molecule [3,4]. The nature and the location of the glycosylation does not influence lactoferrin’s ability to bind iron, but the specific and varied patterns of glycosylation influences its antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activities as lactoferrin glycan modifications have been described to be participate in different cellular pathways, including cell adhesion and receptor activation [3,4]. Human lactoferrin (hLF) shows a high sequence similarity with bovine lactoferrin (bLF), and displays similar biocidal activity against bacteria, viruses and fungi, as well as immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activities [2,5]. The commercial preparations of bLF were recognized as a safe substance (GRAS) by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA, Silver Spring, MD, USA) and are distributed by many companies in large quantities; therefore, the majority of the in vitro and in vivo studies have been using commercial bLF. Recently, recombinant human lactoferrin has also become available.

2. Lactoferrin as Immunomodulator

Some authors suggest that, in a broader sense, LF may be classified as an “alarmin”, a small peptide released from neutrophils upon infection [6] and providing support for further immune reactions [7]. Lactoferrin shows the ability to bind to pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) present various pathogens, mainly recognized by Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [7]. Depending on the pattern of glycosylation, lactoferrin can bind to different receptors present on both of epithelial and immune cells, including CD14 [8], LDL receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1/CD91) [9], Toll-like receptor 2 and 4 (TLR4) [10] cytokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) [11], intelectin-1 (omentin-1) [12], dendritic cell-specific intercellular adhesion molecule-3-grabbing non-integrin on antigen-presenting cells (APCs) [13], Siglec-1 (CD169/sialoadhesin) [14] and nucleolin [15]. Most of these receptors bind other ligands, but lactoferrin also possesses its “own” receptor called lactoferrin receptor/LRP-1/CD91/apoE receptor or the chyclomicron remnant receptor [16]. ApoE is found in many tissues and different cell types, including intestinal epithelial cell lymphocytes, fibroblasts, neurons, hepatocytes and endothelial cells [16]. Some of these receptors may potentially endocyte lactoferrin and trigger cell signaling or target lactoferrin to the nucleus where it could act as a transcriptional activator or transactivator, which further adds to the multiplicity of roles played by LF.

Upon infection, neutrophils release chromatin fibers, known as neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), together with high amounts of elastase, myeloperoxidase (MPO) and lactoferrin—one million of neutrophils can release up to 15 μg of LF [17]. The role of NETs, together with excreted enzymes and peptides, is to trap and kill mostly bacteria [15]. However, some authors showed that LF can actually suppress the release of NETs during inflammation, thus adding to its anti-inflammatory role [18]. Additionally, lactoferrin acts as a competitor for bacterial LPS when binding to the CD14 receptor and, in this manner, it can attenuate the NF-κB-induced expression of various inflammatory mediators [19]. Upon tissue response to injury or infection, LF can control the oxidative burst of macrophages and neutrophils by iron sequestration. Thus, LF may play a role in the regulation of acute inflammation.

In vitro studies have shown that LF may act as a chemo-attractant not only for neutrophils, but also for antigen presenting cells (APCs), such as monocytes and dendritic cells (DCs), for which it also plays a role in activation and maturation [6]. Additionally, de la Rosa et al. demonstrated that the immunization of mice with ovalbumin in the presence of lactoferrin promoted Th1-polarized antigen-specific immune responses [6]. Lactoferrin has been reported as being able to modulate both cell-mediated and humoral immunity by helping in the maturation, differentiation and activation of T and B lymphocytes [2]. Therefore, we can conclude that LF participates both in the innate and adaptive immune responses, also by providing a link between the recognition of a pathogen and mounting the specific response.

5. Lactoferrin and Nanotechnology

Lactoferrin, as other biologically active compounds, is being combined with nanoparticles as new carriers or new formulation. The combination of lactoferrin with nanoparticles is usually used to prepare a new combination of highly toxic drugs. On the other hand, we can observe this type of lactoferrin connections for use in functional foods, supplements and of course in medicine. We can recognize some kinds of combination and formulations.

5.1. Lipid-Based Nanocarriers (Emulsion)

The sol–oil or emulsion (water-in-oil) method is one of those methods in which lactoferrin in aqueous solution is combined with olive oil. The process takes place under conditions of 4 °C with sonication and then freezing in liquid nitrogen. This process was used to prepare anti-cancer substances in order to obtain a formulation with a lower toxicity [68,69]. Another type of emulsion was encapsulation lactoferrin with antiviral particles (Zidovudine) [70]. Similar results were obtained with comparable encapsulation conditions. The nanoparticles were prepared at the size of 50–60 nm with a yield of 67% and a good physical stability at room temperature and 4 °C. Oral-use Zidovudine and its lactoferrin complex showed similar activity against HIV-1 [70]. In addition, the new drug formulation displayed an improved pharmacokinetic profile and a lower organ toxicity [70]. Methodologically, it is possible to prepare various forms and degrees of encapsulation, size and stability. Single-, double- and triple-loaded drugs with nanoparticles with lactoferrin can be produced. In this case, lactoferrin acts as an emulsifier.

Another type of encapsulation depends mainly on the presence of an oily phase in which the drug is soluble (with the organic solvent). In the next step, the oily phase is slowly added to the lactoferrin-containing water phase. The core of the emulsion is formed by subjecting this mixture to shear forces at a low homogenization rate. The mixture can then be sonicated for approximately 2 min. The end product can be obtained by removing the residual organic solvent on a rotary evaporator [71]. In the same way, an insoluble drug can be prepared with nanoparticles bound to albumin and lactoferrin, for example, paclitaxel [72]. This is a very good case for encapsulating delivery systems highly lipophilic drugs in protein nanoparticles [73].

5.2. Inorganic Nanoparticles

A very important use of lactoferrin is its conjugation to inorganic nanoparticles. The conjugates have special features: higher loading, easiness of connection with ligands and biocompatibility. LF-coated magnetic nanocarriers can be used for cancer diagnosis and therapy, acting as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [74,75,76]. The most interesting are superparamagnetic iron oxide nanocarriers (Fe3O4-LF). Iron oxides are prepared by the coprecipitation of Fe2+ and Fe3+ in the presence of a base. The size, shape and composition of iron NPs depend on the type of the salt used, Fe2+ to Fe3+ ratio, pH and ionic strength [77,78]. Magnetic nanocarriers can be combined with lactoferrin and some co-ligands, e.g., via 1-Ethyl-3- (3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyacrylic acid (PAA) [79]. Upon mixing, the LF and co-ligand nanoparticles can form an amide bond between the primary amine and the carboxyl group of the second coupling reagent. The formation of a stable amide bond relies on the activation of the LF carboxyl groups by the coupling reagent [80,81]. Another group of nanocarriers includes silica NPs composed of silicon dioxide of a vast range of sizes. SiNPs were approved by the FDA because they are considered safe [82]. Silica nanoparticles can be a very useful smart brain delivery system and they have been used for the efficient delivery of drugs without damaging the BBB (blood–brain barrier) function. The lactoferrin-based system was based on covalently binding LF to silica nanoparticles (SiNPs). In the next step, LF-SiNPs were PEGylated to prolong their blood circulation [83].

5.3. Polyamidoamine PAMAM Dendrimers

Dendrimers are highly branched radially symmetrical three-dimensional structures with many functional groups that make it easy to conjugate with ligands, such as LF. The most popular dendrimers are fabricated from polyamidoamine (PAMAM) [84]. Due to the possibility of aggregation of platelets, the most beneficial in medicine are first, second and third generations. The most common combination of lactoferrin with dendrimers is PAMAM dendrimer, polyethylene glycol (PEG) and lactoferrin (PAMAM—PEG—LF). In this formula, PEG was used as a spacer for targeted brain delivery [85,86]. In another study, LF was covalently coupled to PAMAM-PEG. The purpose of designing such a use for lactoferrin was a non-viral gene therapy in Parkinson’s disease. On the other hand, the preparation of this type of dendrimer combinations is focused on the preparation of nanoparticles in the form of an emulsion and consists of mixing the appropriate amounts of substrates [87,88].

6. Conclusions

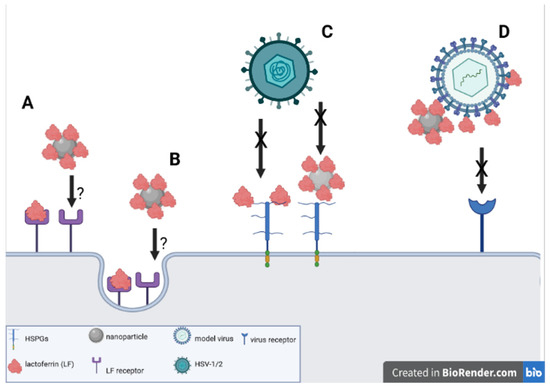

The use of lactoferrin conjugates with nanoparticles seems to offer new solutions for the improvement of the anti-viral activity of lactoferrin itself (Figure 1). We can speculate that the 3D structure of lactoferrin conjugates with nanoparticles facilitates the interaction with both cellular targets—HSPGs as well as with VALs. The exact mechanism of the interaction of virus/cells and lactoferrin functionalized nanoparticles requires further research with the use of techniques allowing the visualization of this interaction, such as TEM and cryoTEM. Furthermore, tests employing different viruses interacting with HSPGs are also required to be performed both in vitro and in vivo in animal models. Last, but not least, pharmacological formulations need to be developed and tested for their efficacy, safety and stability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., P.S., G.C. and J.G.; investigation, M.K., M.J., E.T. and K.R.-S.; data curation, M.J., E.T. and K.R.-S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and P.S.; project administration, M.K. and J.G.; funding acquisition, M.K. and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Polish National Science Centre grant no. 2018/31/B/NZ6/02606.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexander, D.B.; Iigo, M.; Yamauchi, K.; Suzui, M.; Tsuda, H. Lactoferrin: An alternative view of its role in human biological fluids. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legrand, D. Lactoferrin, a key molecule in immune and inflammatory processes. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, E.N.; Anderson, B.F.; Baker, H.M.; Day, C.L.; Haridas, M.; Norris, G.E.; Rumball, S.V.; Smith, C.A.; Thomas, D.H. Three-dimensional structure of lactoferrin in various functional states. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1994, 357, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, L.; Cutone, A.; Lepanto, M.S.; Paesano, R.; Valenti, P. Lactoferrin: A natural glycoprotein involved in iron and inflammatory homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S.A.; Anderson, B.F.; Groom, C.R.; Haridas, M.; Baker, E.N. Three-dimensional structure of diferric bovine lactoferrin at 2.8 A resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1997, 274, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Rosa, G.; Yang, D.; Tewary, P.; Varadhachary, A.; Oppenheim, J.J. Lactoferrin acts as an alarmin to promote the recruitment and activation of APCs and antigen-specific immune responses. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 6868–6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago-Serrano, M.E.; Campos-Rodriguez, R.; Carrero, J.C.; De La Garza, M. Lactoferrin: Balancing Ups and Downs of Inflammation Due to Microbial Infections. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillebeen, C.; Descamps, L.; Dehouck, M.P.; Fenart, L.; Benaïssa, M.; Spik, G.; Cecchelli, R.; Pierce, A. Receptor-mediated transcytosis of lactoferrin through the blood-brain barrier. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 7011–7017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, A.; Banovic, T.; Zhu, Q.; Watson, M.; Callon, K.; Palmano, K.; Ross, J.; Naot, D.; Reid, I.R.; Cornish, J. The low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 is a mitogenic receptor for lactoferrin in osteoblastic cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2004, 18, 2268–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.H.; Dong, H.L.; Tai, L.; Gao, X.M. Lactoferrin-containing immunocomplexes drive the conversion of human macrophages from M2- into M1-like phenotype. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, Y.; Aoki, R.; Uchida, R.; Tajima, A.; Aoki-Yoshida, A. Role of CXC chemokine receptor type 4 as a lactoferrin receptor. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 95, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Yamauchi, K.; Yaeshima, T.; Iwatsuki, K. Recombinant human intelectin binds bovine lactoferrin and its peptides. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 1605–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimecki, M.; Kocieba, M.; Kruzel, M. Immunoregulatory activities of lactoferrin in the delayed type hypersensitivity in mice are mediated by a receptor with affinity to mannose. Immunobiology 2002, 205, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimecki, M.; Artym, J.; Kocieba, M.; Duk, M.; Kruzel, M.L. The effect of carbohydrate moiety structure on the immunoregulatory activity of lactoferrin in vitro. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2014, 19, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Losfeld, M.E.; Khoury, D.E.; Mariot, P.; Carpentier, M.; Krust, B.; Briand, J.P.; Mazurier, J.; Hovanessian, A.G.; Legrand, D. The cell surface expressed nucleolin is a glycoprotein that triggers calcium entry into mammalian cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2009, 315, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikoma-Seki, K.; Nakamura, K.; Morishita, S.; Ono, T.; Sugiyama, K.; Nishino, H.; Hirano, H.; Murakoshi, M. Role of LRP1 and ERK and cAMP Signaling Pathways in Lactoferrin-Induced Lipolysis in Mature Rat Adipocytes. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepanto, M.S.; Rosa, L.; Paesano, R.; Valenti, P.; Cutone, A. Lactoferrin in aseptic and septic inflammation. Molecules 2019, 24, 1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, K.; Kamiya, M.; Urano, Y.; Nishi, H.; Herter, J.M.; Mayadas, T.; Hirohama, D.; Suzuki, K.; Kawakami, H.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Lactoferrin Suppresses Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Release in Inflammation. EBioMedicine 2016, 10, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elass-Rochard, E.; Legrand, D.; Salmon, V.; Roseanu, A.; Trif, M.; Tobias, P.S.; Mazurier, J.; Spik, G. Lactoferrin inhibits the endotoxin interaction with CD14 by competition with the lipopolysaccharide-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, A. Biological roles of glycans. Glycobiology 2016, 27, 3–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lembo, D.; Donalisio, M.; Laine, C.; Cagno, V.; Civra, A.; Bianchini, E.P.; Zeghbib, N.; Bouchemal, K. Auto-associative heparin nanoassemblies: A biomimetic platform against the heparan sulfate-dependent viruses HSV-1, HSV-2, HPV-16 and RSV. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2014, 88, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, R.; Tharakaraman, K.; Sasisekharan, V.; Sasisekharan, R. Glycan-protein interactions in viral pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2016, 40, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlutti, F.; Pantanella, F.; Natalizi, T.; Frioni, A.; Paesano, R.; Polimeni, A.; Valenti, P. Antiviral properties of lactoferrin--a natural immunity molecule. Molecules 2011, 16, 6992–7018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drobni, P.; Naslund, J.; Evander, M. Lactoferrin inhibits human papilloma virus binding and uptake in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2004, 64, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenssen, H.; Sandvik, K.; Andersen, J.H.; Hancock, R.E.; Gutteberg, T.J. Inhibition of HSV cell-to-cell spread by lactoferrin and lactoferricin. Antivir. Res. 2008, 79, 192–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenssen, H. Anti herpes simplex virus activity of lactoferrin/lactoferricin—An example of antiviral activity of antimicrobial protein/peptide. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 3002–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.; Trybala, E.; Superti, F.; Johansson, M.; Bergstrom, T. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus infection by lactoferrin is dependent on interference with the virus binding to glycosaminoglycans. Virology 2004, 318, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Välimaa, H.; Tenovuo, J.; Waris, M.; Hukkanen, V. Human lactoferrin but not lysozyme neutralizes HSV-1 and inhibits HSV-1 replication and cell-to-cell spread. J. Virol. 2009, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihara, T.; Hayashi, K. Lactoferrin inhibits herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) infection in mouse cornea. Arch. Virol. 1995, 140, 1469–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Superti, F. Glycosaminoglycans are not indispensabile for the anti-herpes simplex virus type 2 activity of lactoferrin. Biochemistry 2009, 91, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waarts, B.L.; Aneke, O.J.; Smit, J.M.; Kimata, K.; Bittman, R.; Meijer, D.K.; Wilschut, J. Antiviral activity of human lactoferrin: Inhibition of alphavirus interaction with heparan sulfate. Virology 2005, 333, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, Y.J.; Chen, W.J.; Hsu, W.L.; Chiou, S.S. Bovine lactoferrin inhibits japanese encephalitis virus by binding to heparan sulfate and receptor for low density lipoprotein. Virology 2008, 379, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.M.; Fan, Y.C.; Lin, J.W.; Chen, Y.Y.; Hsu, W.L.; Chiou, S.S. Bovine Lactoferrin Inhibits Dengue Virus Infectivity by Interacting with Heparan Sulfate, Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor, and DC-SIGN. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sano, H.; Nagai, K.; Tsutsumi, H.; Kuroki, Y. Lactoferrin and surfactant protein A exhibit distinct binding specificity to F protein and differently modulate respiratory syncytial virus infection. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003, 33, 2894–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, M.; Kaneko, S.; Yu, D.Y.; Murakami, S. Hepatitis C virus envelope proteins bind lactoferrin. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 5997–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrantoni, A.; Di Biase, A.M.; Tinari, A.; Marchetti, M.; Valenti, P.; Seganti, L.; Superti, F. Bovine lactoferrin inhibits adenovirus infection by interacting with viral structural polypeptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 2688–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, R.M.; Donoval, B.A.; Graham, P.J.; Boksa, L.A.; Spear, G.; Hershow, R.C.; Chen, H.Y.; Landay, A. Cervicovaginal levels of lactoferrin, secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor, and RANTES and the effects of coexisting vaginoses in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-seronegative women with a high risk of heterosexual acquisition of HIV infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2007, 14, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupin, L.; Polesello, V.; Segat, L.; Kamada, A.J.; Kuhn, L.; Crovella, S. Association Between LTF Polymorphism and Risk of HIV-1 Transmission Among Zambian Seropositive Mothers. Curr. HIV Res. 2018, 16, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puddu, P.; Borghi, P.; Gessani, S.; Valenti, P.; Belardelli, F.; Seganti, L. Antiviral effect of bovine lactoferrin saturated with metal ions on early steps of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1998, 30, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, P.J.; Harmsen, M.C.; Kuipers, M.E.; Van Dijk, A.A.; Van Der Strate, B.W.; Van Berkel, P.H.; Nuijens, J.H.; Smit, C.; Witvrouw, M.; De Clercq, E.; et al. Charge modification of plasma and milk proteins results in antiviral active compounds. J. Pept. Sci. 1999, 5, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.L. Origin and Evolution of Pathogenic Coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, J.; Yang, N.; Deng, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, P.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, C. Inhibition of SARS pseudovirus cell entry by lactoferrin binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campione, E.; Lanna, C.; Cosio, T.; Rosa, L.; Conte, M.P.; Iacovelli, F.; Romeo, A.; Falconi, M.; Del Vecchio, C.; Franchin, E.; et al. Lactoferrin Against SARS-CoV-2: In Vitro and In Silico Evidences. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 666600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, J. The in vitro antiviral activity of lactoferrin against common human coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2 is mediated by targeting the heparan sulfate co-receptor. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Superti, F.; Agamennone, M.; Pietrantoni, A.; Ammendolia, M.G. Bovine Lactoferrin Prevents Influenza A Virus Infection by Interfering with the Fusogenic Function of Viral Hemagglutinin. Viruses 2019, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yue, L.; Dang, L.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X.; Shu, J.; Li, Z. Role of sialylated glycans on bovine lactoferrin against influenza virus. Glycoconj. J. 2021, 38, 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantoni, A.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Superti, F. Bovine lactoferrin: Involvement of metal saturation and carbohydrates in the inhibition of influenza virus infection. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 90, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrantoni, A.; Dofrelli, E.; Tinari, A.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Puzelli, S.; Fabiani, C.; Donatelli, I.; Superti, F. Bovine lactoferrin inhibits influenza A virus induced programmed cell death in vitro. Biometals 2010, 23, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campione, E.; Cosio, T.; Rosa, L.; Lanna, C.; Di Girolamo, S.; Gaziano, R.; Valenti, P.; Bianchi, L. Lactoferrin as Protective Natural Barrier of Respiratory and Intestinal Mucosa against Coronavirus Infection and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Rius-Pérez, S. Macrophage Polarization and Reprogramming in Acute Inflammation: A Redox Perspective. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littlefield, K.M.; Watson, R.O.; Schneider, J.M.; Neff, C.P.; Yamada, E.; Zhang, M.; Campbell, T.B.; Falta, M.T.; Jolley, S.E.; Fontenot, A.P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells associate with inflammation and reduced lung function in pulmonary post-acute sequalae of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patrycy, M.; Chodkowski, M.; Krzyzowska, M. Role of Microglia in Herpesvirus-Related Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration. Pathogens 2022, 11, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutone, A.; Rosa, L.; Lepanto, M.S.; Scotti, M.J.; Berlutti, F.; Bonaccorsi di Patti, M.C.; Musci, G.; Valenti, P. Lactoferrin efficiently counteracts the inflammation-induced changes of the iron homeostasis system in macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, P.; Frioni, A.; Rossi, A.; Ranucci, S.; De Fino, I.; Cutone, A.; Rosa, L.; Bragonzi, A.; Berlutti, F. Aerosolized bovine lactoferrin reduces neutrophils and pro-inflammatory cytokines in mouse models of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 95, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, H.H.; Garza-Treviño, E.N.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Singh, D.K. Silver nanoparticles are broad-spectrum bactericidal and virucidal compounds. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2011, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram-Pinto, D.; Shukla, S.; Perkas, N.; Gedanken, A.; Sarid, R. Inhibition of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection by silver nanoparticles capped with mercaptoethane sulfonate. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009, 20, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram-Pinto, D.; Shukla, S.; Gedanken, A.; Sarid, R. Inhibition of HSV-1 attachment, entry, and cell-to-cell spread by functionalized multivalent gold nanoparticles. Small 2010, 6, 1044–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, H.J.; Hutchison, G.; Christensen, F.M.; Peters, S.; Hankin, S.; Stone, V. A review of the in vivo and in vitro toxicity of silver and gold particulates: Particle attributes and biological mechanisms responsible for the observed toxicity. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2010, 40, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironava, T.; Hadjiargyrou, M.; Simon, M.; Jurukovski, V.; Rafailovich, M.H. Gold nanoparticles cellular toxicity and recovery: Effect of size, concentration and exposure time. Nanotoxicology 2010, 4, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlowski, P.; Tomaszewska, E.; Ranoszek-Soliwoda, K.; Gniadek, M.; Labedz, O.; Malewski, T.; Nowakowska, J.; Chodaczek, G.; Celichowski, G.; Grobelny, J.; et al. Tannic Acid-Modified Silver and Gold Nanoparticles as Novel Stimulators of Dendritic Cells Activation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, E.J.; Yi, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, K.; Park, K. Silver nanoparticles induce cytotoxicity by a Trojan-horse type mechanism. Toxicol. In Vitro 2010, 24, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlowski, P.; Tomaszewska, E.; Gniadek, M.; Baska, P.; Nowakowska, J.; Sokolowska, J.; Nowak, Z.; Donten, M.; Celichowski, G.; Grobelny, J.; et al. Tannic acid modified silver nanoparticles show antiviral activity in herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orłowski, P.; Kowalczyk, A.; Tomaszewska, E.; Ranoszek-Soliwoda, K.; Węgrzyn, A.; Grzesiak, J.; Celichowski, G.; Grobelny, J.; Eriksson, K.; Krzyzowska, M. Antiviral Activity of Tannic Acid Modified Silver Nanoparticles: Potential to Activate Immune Response in Herpes Genitalis. Viruses 2018, 10, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, P.S.; Borah, S.M.; Gogoi, H.; Asthana, S.; Bhatnagar, R.; Jha, A.N.; Jha, S. Lactoferrin adsorption onto silver nanoparticle interface: Implications of corona on protein conformation, nanoparticle cytotoxicity and the formulation adjuvanticity. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 361, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

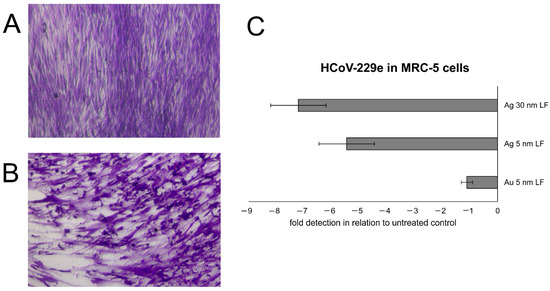

- Krzyzowska, M.; Chodkowski, M.; Janicka, M.; Dmowska, D.; Tomaszewska, E.; Ranoszek-Soliwoda, K.; Bednarczyk, K.; Celichowski, G.; Grobelny, J. Lactoferrin-Functionalized Noble Metal Nanoparticles as New Antivirals for HSV-2 Infection. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belisle, S.E.; Tisoncik, J.R.; Korth, M.J.; Carter, V.S.; Proll, S.C.; Swayne, D.E.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.; Tumpey, T.M.; Katze, M.G. Genomic profiling of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) receptor and interleukin-1 receptor knockout mice reveals a link between TNF-alpha signaling and increased severity of 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 12576–12588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabra, S.; Agwa, M.M. Lactoferrin, a unique molecule with diverse therapeutical and nanotechnological applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Rangaraj, N.; Chakarvarty, S.; Kondapi, A.K.; Rao, N.M. Aurora kinase B siRNA-loaded lactoferrin nanoparticles potentiate the efficacy of temozolomide in treating glioblastoma. Nanomedicine (Lond.) 2018, 13, 2579–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Lakshmi, Y.S.; Kondapi, A.K. Triple Drug Combination of Zidovudine, Efavirenz and Lamivudine Loaded Lactoferrin Nanoparticles: An Effective Nano First-Line Regimen for HIV Therapy. Pharm. Res. 2017, 34, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Sun, J.; Zhang, W.; Sui, X.; Yan, Z.; He, Z. Nanoparticle albumin-bound (NAB) technology is a promising method for anti-cancer drug delivery. Recent Pat. Anticancer Drug Discov. 2009, 4, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, N.; Trieu, V.; Yao, Z.; Louie, L.; Ci, S.; Yang, A.; Tao, C.; De, T.; Beals, B.; Dykes, D.; et al. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 1317–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, J.; Saura, C. Nanoparticle albumin-bound (nab™)-paclitaxel: Improving efficacy and tolerability by targeted drug delivery in metastatic breast cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2010, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Barua, S.; Sharma, G.; Dey, S.K.; Rege, K. Inorganic nanoparticles for cancer imaging and therapy. J. Control. Release 2011, 155, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zain, M.; Yasmeen, H.; Yadav, S.S.; Amir, S.; Bilal, M.; Shahid, A.; Khurshid, M. Chapter 10—Applications of nanotechnology in biological systems and medicine. In Micro and Nano Technologies, Nanotechnology for Hematology, Blood Transfusion, and Artificial Blood; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2022; pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabra, S.A.; Sheweita, S.A.; Haroun, M.; Ragab, D.; Eldemellawy, M.A.; Xia, Y.; Goodale, D.; Allan, A.L.; Elzoghby, A.O.; Rohani, S. Magnetically Guided Self-Assembled Protein Micelles for Enhanced Delivery of Dasatinib to Human Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 108, 1713–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; He, Q.; Jiang, C. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis and surface functionalization strategies. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2008, 3, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Sun, A.; Zhai, F.; Wang, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Volinsky, A.A. Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles synthesis from tailings by ultrasonic chemical co-precipitation. Mater. Lett. 2011, 65, 1882–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, D.; Vijay, I.K. A method for the high efficiency of water-soluble carbodiimide-mediated amidation. Anal. Biochem. 1994, 218, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.H.; Lai, Y.H.; Chiu, T.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Hu, S.H.; Chen, S.Y. Magnetic core-shell nanocapsules with dual-targeting capabilities and co-delivery of multiple drugs to treat brain gliomas. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; He, X.; Wang, K.; He, C.; Shi, H.; Jian, L. Biocompatible silica nanoparticles-insulin conjugates for mesenchymal stem cell adipogenic differentiation. Bioconjug. Chem. 2010, 21, 1673–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.M.; Bekhit, A.A.; Khattab, S.N.; Helmy, M.W.; Abdel-Ghany, Y.S.; Teleb, M.; Elzoghby, A.O. Synthesis of lactoferrin mesoporous silica nanoparticles for pemetrexed/ellagic acid synergistic breast cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 188, 110824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Du, D.; Li, L.; Xu, J.; Dutta, P.; Lin, Y. In Vitro Study of Receptor-Mediated Silica Nanoparticles Delivery across Blood-Brain Barrier. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 20410–20416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval-Yañez, C.; Castro Rodriguez, C. Dendrimers: Amazing Platforms for Bioactive Molecule Delivery Systems. Materials 2020, 13, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Ke, W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Pei, Y. The use of lactoferrin as a ligand for targeting the polyamidoamine-based gene delivery system to the brain. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ke, W.; Han, L.; Liu, Y.; Shao, K.; Ye, L.; Lou, J.; Jiang, C.; Pei, Y. Brain-targeting mechanisms of lactoferrin-modified DNA-loaded nanoparticles. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009, 29, 1914–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Ke, W.; Han, L.; Liu, Y.; Shao, K.; Jiang, C.; Pei, Y. Lactoferrin-modified nanoparticles could mediate efficient gene delivery to the brain in vivo. Brain Res. Bull. 2010, 81, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Ke, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, D.; Feng, L.; Jiang, C.; Pei, Y. Gene therapy using lactoferrin-modified nanoparticles in a rotenone-induced chronic Parkinson model. J. Neurol. Sci. 2010, 290, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).